The Relationship Between Childhood Trauma and Shame: The Mediating Role of Dissociation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

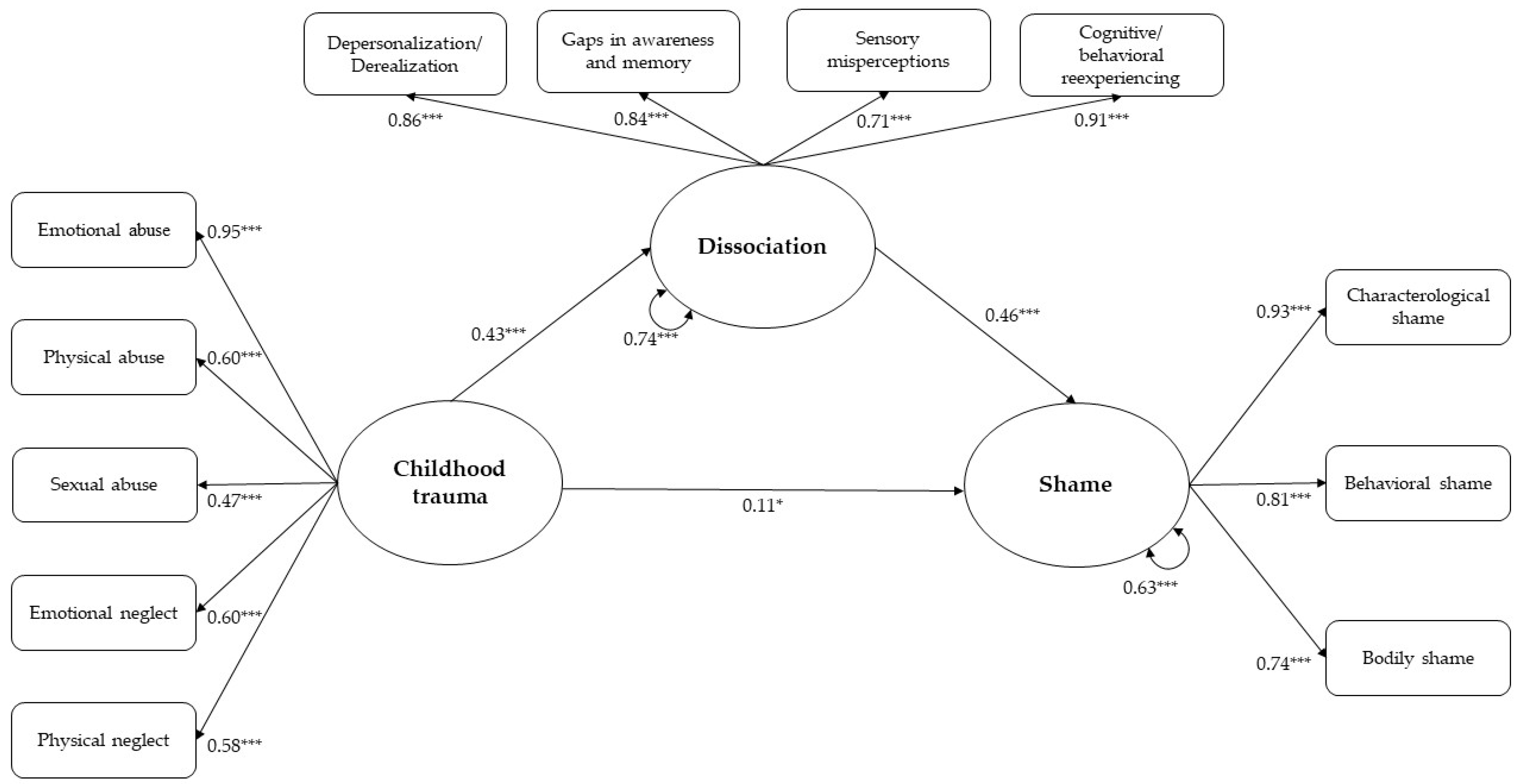

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, B., Qian, M., & Valentine, J. D. (2002). Predicting depressive symptoms with a new measure of shame: The Experience of Shame Scale. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 41(1), 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archuleta, W. P., Kaminski, P. L., & Ross, N. D. (2024). The roles of shame and poor self-concept in explaining low social connection among adult survivors of childhood emotional maltreatment. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 16(7), 1149–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badenes-Ribera, L., Georgieva, S., Tomás, J. M., & Navarro-Pérez, J. J. (2024). Internal consistency and test-retest reliability: A reliability generalization meta-analysis of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire—Short Form (CTQ-SF). Child Abuse & Neglect, 154, 106941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benau, K. (2017). Shame, attachment, and psychotherapy: Phenomenology, neurophysiology, relational trauma, and harbingers of healing. Attachment: New Directions in Psychotherapy and Relational Psychoanalysis, 11(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., Stokes, J., Handelsman, L., Medrano, M., Desmond, D., & Zule, W. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss. Vol. 3: Loss: Sadness and depression. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg, P. M. (1998). Standing in the spaces: Essays on clinical process, trauma, and dissociation. Analytic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg, P. M. (2011). The shadow of the tsunami and the growth of the relational mind. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, E. B., Waelde, L. C., Palmieri, P. A., Macia, K. S., Smith, S. R., & McDade-Montez, E. (2018). Development and validation of the Dissociative Symptoms Scale. Assessment, 25(1), 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chefetz, R. (2022). Attackments: Subjugation, shame, and the attachment to painful affects and objects. In O. B. Epstein (Ed.), Shame matters: Attachment and relational perspectives for psychotherapists (pp. 60–76). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Chefetz, R. A. (2015). Intensive psychotherapy for persistent dissociative processes: The fear of feeling real. W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo, A., Santoro, G., & Schimmenti, A. (2023). Self-medication, traumatic reenactments, and dissociation: A psychoanalytic perspective on the relationship between childhood trauma and substance abuse. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 37(4), 443–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, J. K., Timmerman, M. E., Spitzer, C., & Lampe, A. (2024). Differential constellations of dissociative symptoms and their association with childhood trauma—A latent profile analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 15(1), 2348345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCou, C. R., Lynch, S. M., Weber, S., Richner, D., Mozafari, A., Huggins, H., & Perschon, B. (2023). On the association between trauma-related shame and symptoms of psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(3), 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorahy, M. J., & Clearwater, K. (2012). Shame and guilt in men exposed to childhood sexual abuse: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse: Research, Treatment, & Program Innovations for Victims, Survivors, & Offenders, 21(2), 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorahy, M. J., McKendry, H., Scott, A., Yogeeswaran, K., Martens, A., & Hanna, D. (2017). Reactive dissociative experiences in response to acute increases in shame feelings. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 89, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorahy, M. J., McKeogh, K., & Yogeeswaran, K. (2025). The impact of relationship context on dissociation-induced shame using vignette scenarios. Psychological Reports, 128(3), 1793–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorahy, M. J., Schultz, A., Wooller, M., Clearwater, K., & Yogeeswaran, K. (2021). Acute shame in response to dissociative detachment: Evidence from non-clinical and traumatised samples. Cognition and Emotion, 35(6), 1150–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espirito Santo, H., & Luís Pio-Abreu, J. (2008). Demographic and mental health factors associated with pathological dissociation in a Portuguese sample. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 9(3), 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, B., Liotti, M., & Imperatori, C. (2019). The role of attachment trauma and disintegrative pathogenic processes in the traumatic-dissociative dimension. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flach, V. I., & Cariola, L. A. (2025). Developmental trauma and shame-proneness: A systematic review. Trends in Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, S., Tomas, J. M., & Navarro-Pérez, J. J. (2021). Systematic review and critical appraisal of Childhood Trauma Questionnaire—Short Form (CTQ-SF). Child Abuse & Neglect, 120, 105223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haferkamp, L., Bebermeier, A., Möllering, A., & Neuner, F. (2015). Dissociation is associated with emotional maltreatment in a sample of traumatized women with a history of child abuse. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 16(1), 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J. L. (2012). Shattered shame states and their repair. In J. Yellin, & K. White (Eds.), Shattered states: Disorganised attachment and its repair (pp. 157–170). Karnac Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, G. W. K., Hyland, P., Karatzias, T., Bressington, D., & Shevlin, M. (2021). Traumatic life events as risk factors for psychosis and ICD-11 complex PTSD: A gender-specific examination. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 2009271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y., & Choi, H. (2023). Factor structure and clinical correlates of the Dissociative Symptoms Scale (DSS) Korean version among community sample with adverse childhood experiences. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 24(3), 380–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kate, M.-A., Jamieson, G., & Middleton, W. (2021). Childhood sexual, emotional, and physical abuse as predictors of dissociation in adulthood. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 30(8), 953–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kealy, D., Laverdière, O., Cox, D. W., & Hewitt, P. L. (2023). Childhood emotional neglect and depressive and anxiety symptoms among mental health outpatients: The mediating roles of narcissistic vulnerability and shame. Journal of Mental Health, 32(1), 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keene, A. C., & Epps, J. (2016). Childhood physical abuse and aggression: Shame and narcissistic vulnerability. Child Abuse & Neglect, 51, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilborne, B. (1999). When trauma strikes the soul: Shame, splitting, and psychic pain. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 59(4), 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Talbot, N. L., & Cicchetti, D. (2009). Childhood abuse and current interpersonal conflict: The role of shame. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(6), 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouri, N., D’Andrea, W., Brown, A. D., & Siegle, G. J. (2023). Shame-induced dissociation: An experimental study of experiential avoidance. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 15(4), 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanius, R. A. (2015). Trauma-related dissociation and altered states of consciousness: A call for clinical, treatment, and neuroscience research. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 27905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehdonvirta, V., Oksanen, A., Räsänen, P., & Blank, G. (2021). Social media, web, and panel surveys: Using non-probability samples in social and policy research. Policy & Internet, 13(1), 134–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, H. B. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. Psychoanalytic Review, 58(3), 419–438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lewis, M. (1992). Shame: The exposed self. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maaranen, P., Tanskanen, A., Hintikka, J., Honkalampi, K., Haatainen, K., Koivumaa-Honkanen, H., & Viinamäki, H. (2008). The course of dissociation in the general population: A 3-year follow-up study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49(3), 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Main, M., & Hesse, E. (1990). Parents’ unresolved traumatic experiences are related to infant disorganized attachment status: Is frightened and/or frightening parental behavior the linking mechanism? In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 161–182). The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marusak, H. A., Martin, K. R., Etkin, A., & Thomason, M. E. (2015). Childhood trauma exposure disrupts the automatic regulation of emotional processing. Neuropsychopharmacology, 40(5), 1250–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, M. L., & Keen, S. M. (2022). Child abuse and neglect (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R. S., & Tangney, J. P. (1994). Differentiating embarrassment and shame. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 13(3), 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojallal, M., Simons, R. M., & Simons, J. S. (2021). Childhood maltreatment and adulthood proneness to shame and guilt: The mediating role of maladaptive schemas. Motivation and Emotion, 45(2), 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechita, D.-M., Bud, S., & David, D. (2021). Shame and eating disorders symptoms: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54(11), 1899–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Loghlen, E., Galligan, R., & Grant, S. (2023). Childhood maltreatment, shame, psychological distress, and binge eating: Testing a serial mediational model. Journal of Eating Disorders, 11(1), 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U., Robins, R. W., & Soto, C. J. (2010). Tracking the trajectory of shame, guilt, and pride across the life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(6), 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, M. G., Luoma, J. B., & Freyd, J. J. (2017). Shame and dissociation in survivors of high and low betrayal trauma. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 26(1), 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prino, L. E., Longobardi, C., & Settanni, M. (2018). Young adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Prevalence of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse in Italy. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(6), 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riazi, S. S., & Manouchehri, M. (2024). The mediating role of mentalization and integrative self-knowledge in the relationship between childhood trauma and fear of intimacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1384573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, N. D., Kaminski, P. L., & Herrington, R. (2019). From childhood emotional maltreatment to depressive symptoms in adulthood: The roles of self-compassion and shame. Child Abuse & Neglect, 92, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R Package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudy, J. A., McKernan, S., Kouri, N., & D’Andrea, W. (2022). A meta-analysis of the association between shame and dissociation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 35(5), 1318–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacchi, C., Vieno, A., & Simonelli, A. (2018). Italian validation of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire—Short Form on a college group. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 10(5), 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, G., Musetti, A., Costanzo, A., & Schimmenti, A. (2025). Self-discontinuity in behavioral addictions: A psychodynamic framework. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 21, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schimmenti, A. (2012). Unveiling the hidden self: Developmental trauma and pathological shame. Psychodynamic Practice, 18(2), 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmenti, A. (2022). The aggressor within: Attachment trauma, segregated systems, and the double face of shame. In O. B. Epstein (Ed.), Shame matters: Attachment and relational perspectives for psychotherapists (pp. 114–132). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti, A. (2023). The relationship between attachment and dissociation: Theory, research, and clinical implications. In M. J. Dorahy, S. N. Gold, & J. A. O’Neil (Eds.), Dissociation and the dissociative disorders: Past, present, future (2nd ed., pp. 161–176). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti, A., & Caretti, V. (2016). Linking the overwhelming with the unbearable: Developmental trauma, dissociation, and the disconnected self. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 33(1), 106–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmenti, A., Sideli, L., La Barbera, D., La Cascia, C., Waelde, L. C., & Carlson, E. B. (2020). Psychometric properties of the Dissociative Symptoms Scale (DSS) in Italian outpatients and community adults. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 21(5), 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, M., Back, S. N., Seitz, K. I., Harbrecht, N. K., Streckert, L., Schulz, A., Herpertz, S. C., & Bertsch, K. (2023). The impact of traumatic childhood experiences on interoception: Disregarding one’s own body. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 10(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schore, A. N. (1998). Early shame experiences and infant brain development. In P. Gilbert, & B. Andrews (Eds.), Shame: Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology, and culture (pp. 57–77). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar, B., Doron, G., & Szepsenwol, O. (2015). Childhood maltreatment, shame-proneness and self-criticism in social anxiety disorder: A sequential mediational model. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22(6), 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeon, D., & Putnam, F. (2022). Pathological dissociation in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): Prevalence, morbidity, comorbidity, and childhood maltreatment. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 23(5), 490–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltenborgh, M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2013). The neglect of child neglect: A meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(3), 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swee, M. B., Hudson, C. C., & Heimberg, R. G. (2021). Examining the relationship between shame and social anxiety disorder: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 90, 102088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmon, A., & Ginzburg, K. (2017). Between childhood maltreatment and shame: The roles of self-objectification and disrupted body boundaries. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 41(3), 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J. P. (2001). Constructive and destructive aspects of shame and guilt. In A. C. Bohart, & D. J. Stipek (Eds.), Constructive & destructive behavior: Implications for family, school, & society (pp. 127–145). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Kolk, B. A., Roth, S., Pelcovitz, D., Sunday, S., & Spinazzola, J. (2005). Disorders of extreme stress: The empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velotti, P., Garofalo, C., Bottazzi, F., & Caretti, V. (2017). Faces of shame: Implications for self-esteem, emotion regulation, aggression, and well-being. The Journal of Psychology, 151(2), 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viola, T. W., Salum, G. A., Kluwe-Schiavon, B., Sanvicente-Vieira, B., Levandowski, M. L., & Grassi-Oliveira, R. (2016). The influence of geographical and economic factors in estimates of childhood abuse and neglect using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A worldwide meta-regression analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizin, G., Urbán, R., & Unoka, Z. (2016). Shame, trauma, temperament and psychopathology: Construct validity of the Experience of Shame Scale. Psychiatry Research, 246, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonderlin, R., Kleindienst, N., Alpers, G. W., Bohus, M., Lyssenko, L., & Schmahl, C. (2018). Dissociation in victims of childhood abuse or neglect: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Medicine, 48(15), 2467–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, J. R., Lazzareschi, N. R., Liu, Y., & O’Sullivan, D. (2023). Childhood psychological maltreatment, sense of self, and PTSD symptoms in emerging adulthood. Journal of Counseling & Development, 101(1), 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Wang, X., Zhang, Q., Zhao, M., & Wang, Y. (2025). The association between child maltreatment and shame: A meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 167, 107557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Wang, P., Liu, L., Wu, X., & Wang, W. (2023). Childhood maltreatment affects college students’ nonsuicidal self-injury: Dual effects via trauma-related guilt, trauma-related shame, and prosocial behaviors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 141, 106205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Full Sample | Males | Females | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 763) | (n = 284) | (n = 479) | ||||||||||

| M | (SD) | Range | Skewness | Kurtosis | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | t(761) | p | d | |

| Age | 31.31 | (13.29) | 18–65 | 1.06 | −0.29 | 32.12 | 13.71 | 30.82 | 13.03 | 1.30 | 0.193 | 0.10 |

| Years of education | 14.35 | (2.77) | 5–21 | 0.14 | 0.71 | 14.31 | 2.93 | 14.38 | 2.67 | −0.34 | 0.738 | −0.03 |

| CTQ-SF—Emotional abuse | 7.97 | (4.11) | 5–25 | 1.65 | 2.17 | 8.00 | 4.09 | 7.95 | 4.13 | 0.15 | 0.881 | 0.01 |

| CTQ-SF—Physical abuse | 6.01 | (2.59) | 5–25 | 3.92 | 17.47 | 6.46 | 3.15 | 5.74 | 2.16 | 3.76 | <0.001 | 0.28 |

| CTQ-SF—Sexual abuse | 6.13 | (3.10) | 5–24 | 3.40 | 11.88 | 5.97 | 2.82 | 6.23 | 3.25 | −1.11 | 0.266 | −0.08 |

| CTQ-SF—Emotional neglect | 10.03 | (4.85) | 5–25 | 0.91 | −0.02 | 10.42 | 4.89 | 9.80 | 4.82 | 1.71 | 0.087 | 0.13 |

| CTQ-SF—Physical neglect | 6.60 | (2.56) | 5–20 | 2.08 | 4.40 | 7.08 | 3.03 | 6.31 | 2.18 | 4.05 | <0.001 | 0.30 |

| DSS—Depersonalization/derealization | 0.66 | (0.85) | 0–4 | 1.55 | 1.86 | 0.59 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.88 | −1.82 | 0.069 | −0.14 |

| DSS—Sensory misperceptions | 0.47 | (0.73) | 0–4 | 1.95 | 3.66 | 0.46 | 0.73 | 0.47 | 0.72 | −0.27 | 0.790 | −0.02 |

| DSS—Cognitive/behavioral reexperiencing | 1.15 | (1.08) | 0–4 | 0.77 | −0.46 | 0.98 | 1.05 | 1.25 | 1.09 | −3.41 | 0.001 | −0.26 |

| DSS—Gaps in awareness and memory | 1.15 | (1.04) | 0–4 | 0.75 | −0.39 | 1.08 | 1.01 | 1.19 | 1.05 | −1.42 | 0.155 | −0.11 |

| DSS—Total scale | 16.68 | (16.11) | 0–80 | 1.19 | 0.90 | 15.16 | 15.58 | 17.58 | 16.37 | −2.01 | 0.045 | −0.15 |

| ESS—Characterological shame | 24.42 | (9.22) | 12–48 | 0.62 | −0.55 | 23.08 | 8.96 | 25.21 | 9.30 | −3.10 | 0.002 | −0.23 |

| ESS—Behavioral shame | 20.46 | (6.73) | 9–36 | 0.29 | −0.71 | 18.85 | 6.55 | 21.42 | 6.66 | −5.18 | <0.001 | −0.39 |

| ESS—Bodily shame | 9.33 | (3.84) | 4–16 | 0.18 | −1.18 | 8.06 | 3.59 | 10.08 | 3.79 | −7.26 | <0.001 | −0.54 |

| ESS—Total scale | 54.21 | (17.83) | 25–100 | 0.41 | −0.68 | 49.99 | 17.28 | 56.71 | 17.70 | −5.11 | <0.001 | −0.38 |

| 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | 16. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 0.20 *** | −0.13 *** | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.09 * | −0.13 *** | −0.06 | −0.22 *** | −0.26 *** | −0.20 *** | −0.31 *** | −0.14 *** | −0.22 *** | −0.26 *** |

| 2. Years of education | - | −0.09 * | −0.03 | 0 | −0.06 | − 0.09 * | −0.15 *** | −0.20 *** | −0.19 *** | −0.19 *** | −0.21 *** | −0.10 ** | −0.02 | −0.07 | −0.07 * |

| 3. CTQ-SF—Emotional abuse | - | 0.52 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.60 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.34 *** | |

| 4. CTQ-SF—Physical abuse | - | 0.36 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.13 *** | 0.12 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.13 *** | ||

| 5. CTQ-SF—Sexual abuse | - | 0.20 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.23 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.13 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.17 *** | |||

| 6. CTQ-SF—Emotional neglect | - | 0.59 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.18 *** | ||||

| 7. CTQ-SF—Physical neglect | - | 0.26 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.12 ** | 0.08 * | 0.06 | 0.11 ** | |||||

| 8. DSS—Depersonalization/derealization | - | 0.76 *** | 0.75 *** | 0.68 *** | 0.91 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.46 *** | ||||||

| 9. DSS—Sensory misperceptions | - | 0.62 *** | 0.67 *** | 0.85 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.25 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.30 *** | |||||||

| 10. DSS—Cognitive/behavioral reexperiencing | - | 0.74 *** | 0.88 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.49 *** | ||||||||

| 11. DSS—Gaps in awareness and memory | - | 0.89 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.45 *** | |||||||||

| 12. DSS—Total scale | - | 0.49 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.49 *** | ||||||||||

| 13. ESS—Characterological shame | - | 0.78 *** | 0.62 *** | 0.95 *** | |||||||||||

| 14. ESS—Behavioral shame | - | 0.62 *** | 0.91 *** | ||||||||||||

| 15. ESS—Bodily shame | - | 0.77 *** | |||||||||||||

| 16. ESS—Total scale | - |

| β | p | 95% C.I. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect of childhood trauma on shame | 0.11 | 0.022 | 0.016–0.209 |

| Indirect effect via dissociation | 0.20 | <0.001 | 0.142–0.253 |

| Total effect of childhood trauma on shame | 0.31 | <0.001 | 0.230–0.391 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santoro, G.; Sideli, L.; Musetti, A.; Schimmenti, A. The Relationship Between Childhood Trauma and Shame: The Mediating Role of Dissociation. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080151

Santoro G, Sideli L, Musetti A, Schimmenti A. The Relationship Between Childhood Trauma and Shame: The Mediating Role of Dissociation. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(8):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080151

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantoro, Gianluca, Lucia Sideli, Alessandro Musetti, and Adriano Schimmenti. 2025. "The Relationship Between Childhood Trauma and Shame: The Mediating Role of Dissociation" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 8: 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080151

APA StyleSantoro, G., Sideli, L., Musetti, A., & Schimmenti, A. (2025). The Relationship Between Childhood Trauma and Shame: The Mediating Role of Dissociation. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(8), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15080151