Understanding Well-Being in the Classroom: A Study on Italian Primary School Teachers Using the JD-R Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

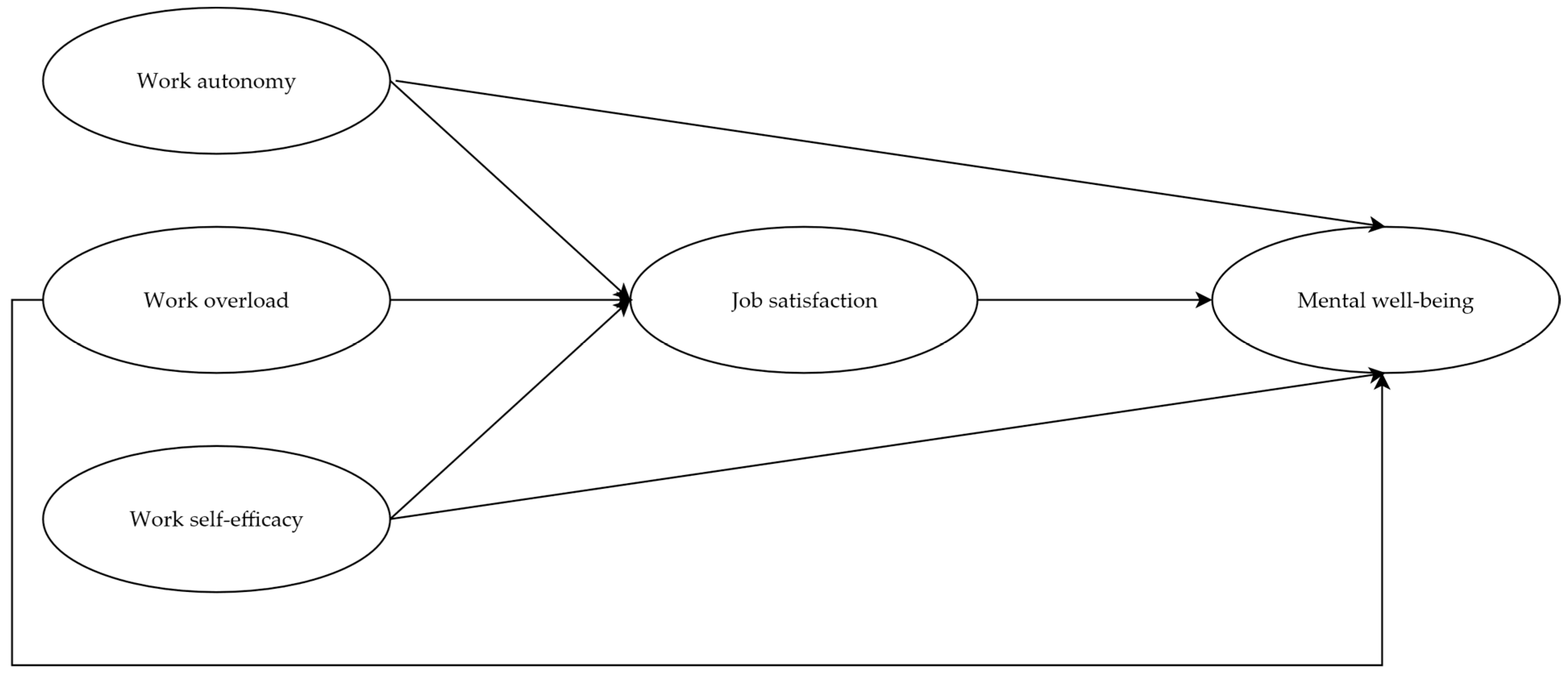

The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. The Measurement Model

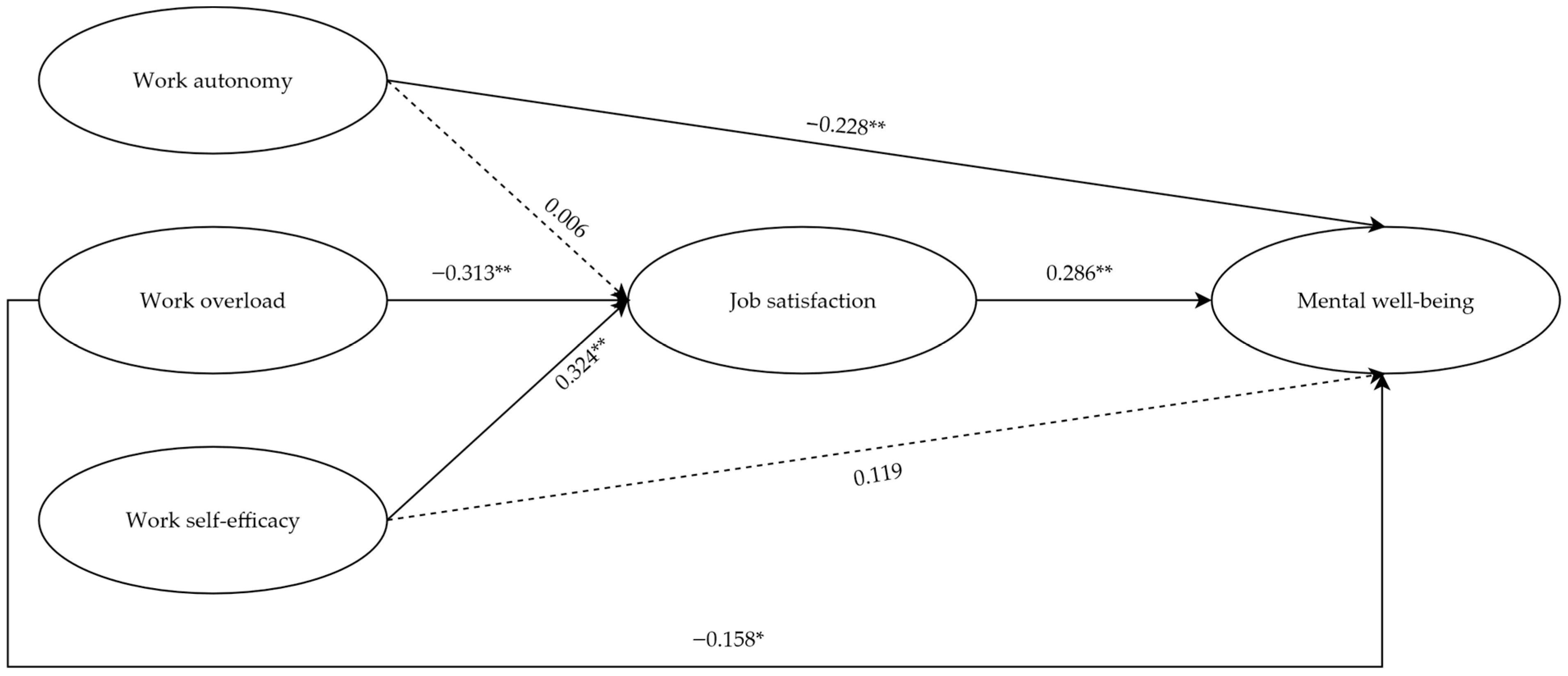

3.3. The Structural Model

4. Discussion

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| W_AUTO | OVER | S_EFF | J_SAT | WELL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W_AUTO | 0.736 | ||||

| OVER | 0.221 | 0.864 | |||

| S_EFF | −0.158 | −0.108 | 0.714 | ||

| J_SAT | −0.115 | −0.347 | 0.356 | - | |

| WELL | −0.314 | −0.320 | 0.274 | 0.409 | 0.789 |

| J_SAT | WELL | |

|---|---|---|

| J_SAT | 1.288 | |

| W_AUTO | 1.072 | 1.072 |

| OVER | 1.057 | 1.184 |

| S_EFF | 1.032 | 1.166 |

References

- Avanzi, L., Fraccaroli, F., Castelli, L., Marcionetti, J., Crescentini, A., Balducci, C., & van Dick, R. (2018). How to mobilize social support against workload and burnout: The role of organizational identification. Teaching and Teacher Education, 69, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands–resources theory. In Wellbeing: A complete reference guide (pp. 1–28). Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (2000). Self-efficacy. (Encyclopedia). In A. E. Kazdin (Ed.), Encyclopedia of psychology (Vol. 7, pp. 212–213). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaranelli, C. (2006). Analisi dei dati con SPSS II. Le analisi multivariate (pp. 65–111). LED Edizioni Universitarie. [Google Scholar]

- Borgogni, L., Dello Russo, S., Petitta, L., & Latham, G. P. (2009). Collective efficacy and organizational commitment in an Italian city hall. European Psychologist, 14(4), 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgogni, L., Petitta, L., & Steca, P. (2001). Personal and collective efficacy in organizational contexts. In G. V. Caprara (Ed.), La valutazione dell’autoefficacia: Costrutti e strumenti (pp. 157–172). Erikson Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling, N. A., Alarcon, G. M., Bragg, C. B., & Hartman, M. J. (2015). A meta-analytic examination of the potential correlates and consequences of workload. Work & Stress, 29, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brief, A. P. (1998). Attitudes in and around organizations. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cann, R., Sinnema, C., Rodway, J., & Daly, A. J. (2023). What do we know about interventions to improve educator wellbeing? A systematic literature review. Journal of Educational Change, 25, 231–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, V., Joshanloo, M., & Park, M. S. A. (2019). Burnout, depression, efficacy beliefs, and work-related variables among school teachers. International Journal of Educational Research, 95, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, V., & Petrillo, G. (2020). Mental health in teachers: Relationships with job satisfaction, efficacy beliefs, burnout and depression. Current Psychology, 39(5), 1757–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Borgogni, L., Petitta, L., & Rubinacci, A. (2003). Teachers’, school staff’s and parents’ efficacy beliefs as determinants of attitude toward school. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 18, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Steca, P., & Malone, P. S. (2006). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs as determinants of job satisfaction and students’ academic achievement: A study at the school level. Journal of School Psychology, 44(6), 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C. L., Dewe, P., & O’Driscoll, M. P. (2001). Organizational stress: A review and critique of theory, research, and applications. Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Cortese, C. G., & Quaglino, G. P. (2006). The measurement of job satisfaction in organizations: A comparison between a facet scale and a single-item measure. TPM-Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 13(4), 305–316. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato, A., & Majer, V. (2005). M_Doq10 Majer_D’Amato organizational questionnaire 10. Organizzazioni Speciali. ISBN 88-09-40253-7. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, K., Gedikli, C., Watson, D., Semkina, A., & Vaughn, O. (2017). Job design, employment practices and well-being: A systematic review of intervention studies. Ergonomics, 60(9), 1177–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettmers, J., & Bredehöft, F. (2020). The ambivalence of job autonomy and the role of job design demands. Scandinavian Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 5(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicke, T., Stebner, F., Linninger, C., Kunter, M., & Leutner, D. (2018). A longitudinal study of teachers’ occupational well-being: Applying the job demands-resources model. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(2), 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoo, J. (2018). Collective teacher efficacy research: Productive patterns of behaviour and other positive consequences. Journal of Educational Change, 19(3), 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gender Data Portal. (2022). All indicators. Available online: https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/indicator/se-prm-tchr-fe-zs (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Granziera, H., & Perera, H. N. (2019). Relations among teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, engagement, and work satisfaction: A social cognitive view. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 58, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 16(2), 250–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. (2021). Teacher collaboration: 30 years of research on its nature, forms, limitations and effects. In Policy, teacher education and the quality of teachers and teaching (pp. 103–121). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Harmsen, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Maulana, R., & Van Veen, K. (2018). The relationship between beginning teachers’ stress causes, stress responses, teaching behaviour and attrition. Teachers and Teaching, 24(6), 626–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomuad, P. D., Antiquina, L. M. M., Cericos, E. U., Bacus, J. A., Vallejo, J. H., Dionio, B. B., & Clarin, A. S. (2021). Teachers’ workload in relation to burnout and work performance. International Journal of Educational Policy Research and Review, 8(2), 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluation traits—Self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—With job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 8, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., & Locke, E. A. (2000). Personality and job satisfaction: The mediating role of job characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(2), 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasek, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(2), 285–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, C. L., & Waterman, M. B. (2003). Dimensions of well-being and mental health in adulthood. In Well-being (pp. 477–497). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of E-Collaboration (IJeC), 11(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiter, M. P. (1992). Burnout as a crisis in self-efficacy: Conceptual and practical implications. Work and Stress, 6, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F., Zhu, W., & Avolio, B. J. (2006). The impact of efficacy on work attitudes across cultures. Journal of World Business, 41, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Does teacher burnout affect students? A systematic review of its association with academic achievement and student-reported outcomes. International Journal of Educational Research, 105, 101714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2008). Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(3), 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijakoski, D., Cheptea, D., Marca, S. C., Shoman, Y., Caglayan, C., Bugge, M. D., & Canu, I. G. (2022). Determinants of burnout among teachers: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J. E. (2000). One road to turnover: An examination of work exhaustion in technology professionals. MIS Quarterly, 24, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D. B., Usher, E. L., & Chen, J. A. (2017). Reconceptualizing the sources of teaching self-efficacy: A critical review of emerging literature. Educational Psychology Review, 29, 795–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, G., Alba, S., & Pitrolo, C. (2023). Primary school teachers’ emotions, implicit beliefs, and self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods study in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1099120. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2018). Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/about/programmes/edu/talis/talis2018participantnotes/volii/TALIS2018_CN_ITA_Vol_II_extended.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Pakdee, S., Cheechang, P., Thammanoon, R., Krobpet, S., Piya-amornphan, N., Puangsri, P., & Gosselink, R. (2025). Burnout and well-being among higher education teachers: Influencing factors of burnout. BMC Public Health, 25, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrillo, G., Capone, V., Caso, D., & Keyes, C. L. (2015). The Mental Health Continuum–Short Form (MHC–SF) as a measure of well-being in the Italian context. Social Indicators Research, 121(1), 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C., da Silva, D., & Bido, D. (2015). Structural equation modeling with the SmartPLS (SSRN scholarly paper 2676422). Social Science Research Network. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2676422 (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Ringle, C., Wende, S., & Becker, J. (2024). SmartPLS 4. SmartPLS GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Rothmann, S., & Redelinghuys, K. (2020). Exploring the prevalence of workplace flourishing amongst teachers over time. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 46(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarzello, D., & Prino, L. E. (2025). Teacher burnout in pre-schools: The role of alexithymia and job satisfaction. Psychology in the Schools, 62(9), 3195–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schettino, G., & Capone, V. (2025). From online learning to clinical practice: An investigation on the factors influencing training transfer among physicians. Healthcare, 13(2), 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schettino, G., Hodačová, L., Caso, D., & Capone, V. (2024). Physicians’ adoption of massive open online courses content in the workplace: An investigation on the training transfer process through the theory of planned behavior. Computers in Human Behavior, 154, 108151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K. (2022). Teachers’ commitment and self-efficacy as predictors of work engagement and well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 850204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2010). Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: A study of relations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(4), 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2020). Teacher burnout: Relations between dimensions of burnout, perceived school context, job satisfaction and motivation for teaching. A longitudinal study. Teachers and Teaching, 26(7–8), 602–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P. E. (1997). Job satisfaction: Application, assessment, causes, and consequences. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Venturini, S., & Mehmetoglu, M. (2019). Plssem: A stata package for structural equation modeling with partial least squares. Journal of Statistical Software, 88, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolfolk, A. E., Rosoff, B., & Hoy, W. K. (1990). Teachers’ sense of efficacy and their beliefs about managing students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 6(2), 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, E., Sharma, U., & Subban, P. (2022). Factors influencing teacher self-efficacy for inclusive education: A systematic literature review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 117, 103800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Mean | Std. Dev | Range | W_AUTO | OVER | S_EFF | WELL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W_AUTO.1 | 2.68 | 1.38 | 1–5 | 0.807 | |||

| W_AUTO.2 | 2.70 | 1.34 | 1–5 | 0.837 | |||

| W_AUTO.3 | 2.62 | 1.32 | 1–5 | 0.510 | |||

| W_AUTO.4 | 2.74 | 1.34 | 1–5 | 0.823 | |||

| W_AUTO.5 | 2.80 | 1.32 | 1–5 | 0.646 | |||

| OVER.1 | 5.25 | 1.62 | 1–7 | 0.853 | |||

| OVER.2 | 4.25 | 1.84 | 1–7 | 0.864 | |||

| OVER.3 | 5.21 | 1.67 | 1–7 | 0.846 | |||

| OVER.4 | 4.66 | 1.92 | 1–7 | 0.892 | |||

| S_EFF.1 | 5.70 | 1.10 | 1–7 | 0.660 | |||

| S_EFF.2 | 5.47 | 1.35 | 1–7 | 0.689 | |||

| S_EFF.3 | 6.16 | 0.77 | 1–7 | 0.668 | |||

| S_EFF.4 | 5.66 | 1.11 | 1–7 | 0.738 | |||

| S_EFF.5 | 5.71 | 0.92 | 1–7 | 0.725 | |||

| S_EFF.6 | 5.75 | 0.89 | 1–7 | 0.796 | |||

| WELL.1 | 2.97 | 1.29 | 0–5 | 0.840 | |||

| WELL.2 | 3.68 | 1.41 | 0–5 | 0.885 | |||

| WELL.3 | 3.16 | 1.27 | 0–5 | 0.881 | |||

| WELL.4 | 3.10 | 1.41 | 0–5 | 0.747 | |||

| WELL.5 | 3.27 | 1.28 | 0–5 | 0.849 | |||

| WELL.6 | 3.36 | 1.33 | 0–5 | 0.767 | |||

| WELL.7 | 3.59 | 1.38 | 0–5 | 0.803 | |||

| WELL.8 | 3.49 | 1.36 | 0–5 | 0.772 | |||

| WELL.9 | 3.70 | 1.49 | 0–5 | 0.857 | |||

| WELL.10 | 3.22 | 1.56 | 0–5 | 0.814 | |||

| WELL.11 | 3.12 | 1.64 | 0–5 | 0.821 | |||

| WELL.12 | 1.67 | 1.55 | 0–5 | 0.699 | |||

| WELL.13 | 2.04 | 1.44 | 0–5 | 0.655 | |||

| WELL.14 | 1.84 | 1.51 | 0–5 | 0.692 | |||

| Cronbach’s α | 0.787 | 0.888 | 0.807 | 0.953 | |||

| Rho A | 0.843 | 0.911 | 0.810 | 0.959 | |||

| AVE | 0.541 | 0.746 | 0.510 | 0.623 |

| Path Coefficients | SE | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | |||

| W_AUTO → J_SAT | 0.006 | 0.073 | (−0.125, 0.166) |

| OVER → J_SAT | −0.313 ** | 0.093 | (−0.471, −0.111) |

| S_EFF → J_SAT | 0.324 ** | 0.097 | (0.111, 0.492) |

| W_AUTO → WELL | −0.228 ** | 0.067 | (−0.346, −0.080) |

| OVER → WELL | −0.158 * | 0.079 | (−0.302, −0.003) |

| S_EFF → WELL | 0.119 | 0.085 | (−0.053, 0.279) |

| J_SAT → WELL | 0.286 ** | 0.104 | (0.069, 0.472) |

| Indirect effects | |||

| W_AUTO → J_SAT → WELL | 0.002 | 0.021 | (−0.040, 0.043) |

| OVER → J_SAT → WELL | −0.090 * | 0.036 | (−0.182, −0.032) |

| S_EFF → J_SAT → WELL | 0.092 * | 0.040 | (0.031, 0.194) |

| Total effects | |||

| W_AUTO → WELL | −0.226 ** | 0.065 | (−0.335, −0.074) |

| OVER → WELL | −0.247 ** | 0.075 | (−0.384, −0.086) |

| S_EFF → WELL | 0.211 ** | 0.078 | (0.051, 0.353) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the University Association of Education and Psychology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trocino, M.F.; Schettino, G.; Capone, V. Understanding Well-Being in the Classroom: A Study on Italian Primary School Teachers Using the JD-R Model. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110234

Trocino MF, Schettino G, Capone V. Understanding Well-Being in the Classroom: A Study on Italian Primary School Teachers Using the JD-R Model. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education. 2025; 15(11):234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110234

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrocino, Maria Francesca, Giovanni Schettino, and Vincenza Capone. 2025. "Understanding Well-Being in the Classroom: A Study on Italian Primary School Teachers Using the JD-R Model" European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education 15, no. 11: 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110234

APA StyleTrocino, M. F., Schettino, G., & Capone, V. (2025). Understanding Well-Being in the Classroom: A Study on Italian Primary School Teachers Using the JD-R Model. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(11), 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe15110234