Abstract

Introduction: Blastomycosis is an endemic mycosis in the United States known to primarily cause pneumonia. However, dissemination to different organs including the musculoskeletal system has been described. Case report: We report a case of mandibular blastomycosis in a healthy patient with no evidence of lung involvement. A 28 year-old female presented with recurrent right mandibular osteomyelitis despite courses of antibiotics and surgical debridement. She eventually underwent right hemimandibulectomy. Budding yeasts visualized on Gomori Methenamine-Silver (GMS) and Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) were morphologically consistent with Blastomyces dermatitidis, and intra-operative cultures showed growth of mold identified as B. dermatitidis by DNA probe. She was placed on a prolonged course of itraconazole with clinical improvement. We also reviewed the literature and found 5 cases of similar presentation which we briefly summarized in this present case report. Conclusion: Blastomycosis should be considered in patients with recurrent or persistent mandibular osteomyelitis even in immunocompetent individuals.

Introduction

Blastomycosis is a pyogranulomatous infection caused by a dimorphic fungus, Blastomyces dermatitidis [1]. Inhaled conidia of the Blastomyces leads to a primary lung infection. However, dissemination can occur via lymphohematogenous spread to the skin, bone and joint, as well as the genitourinary tract [2]. Arthritis and osteomyelitis are clinical manifestations of bone infection. While any bone and bone structure can be infected, case reports regarding infection of the mandible are sparse. Here, we present a case of mandibular blastomycosis in an immunocompetent patient with no pulmonary involvement, along with a literature review.

Case report

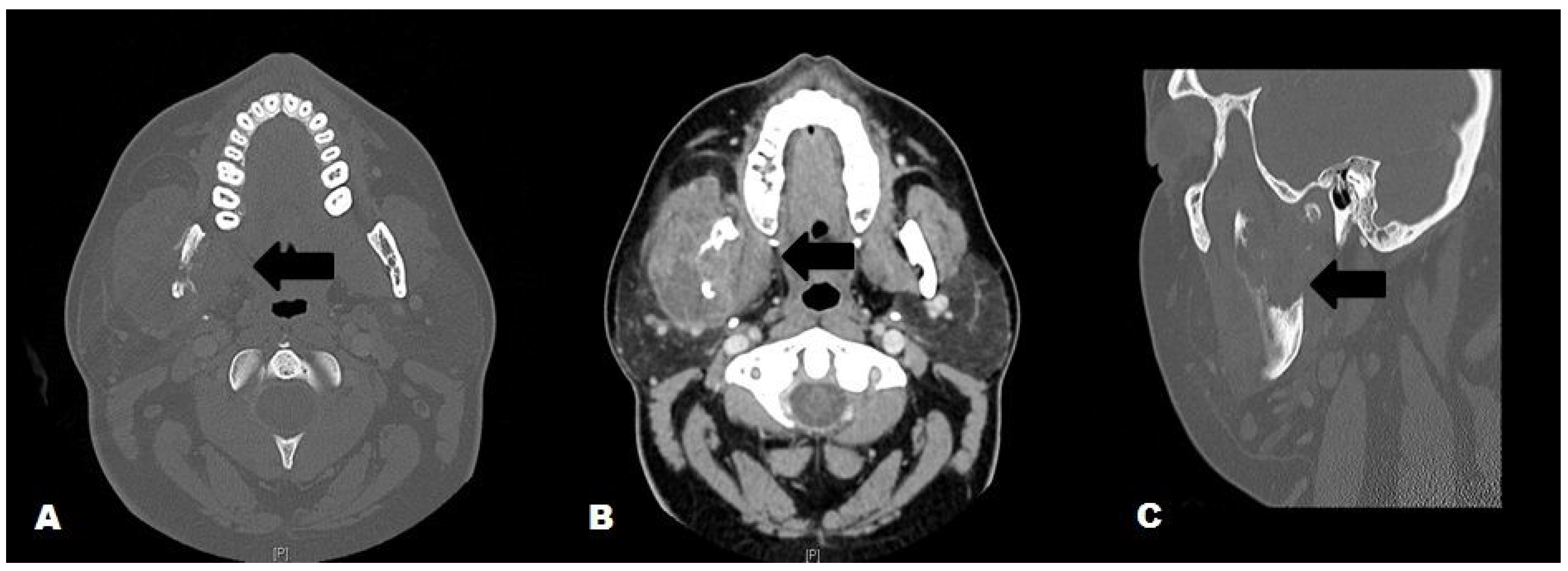

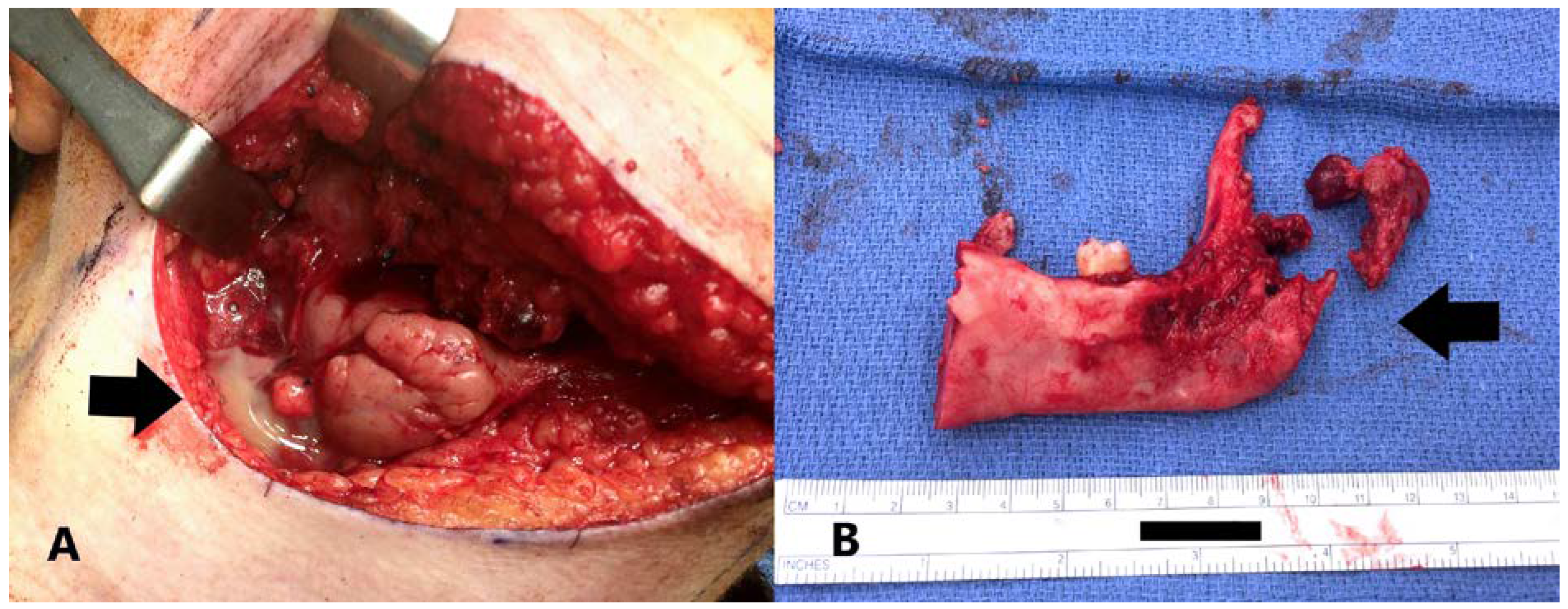

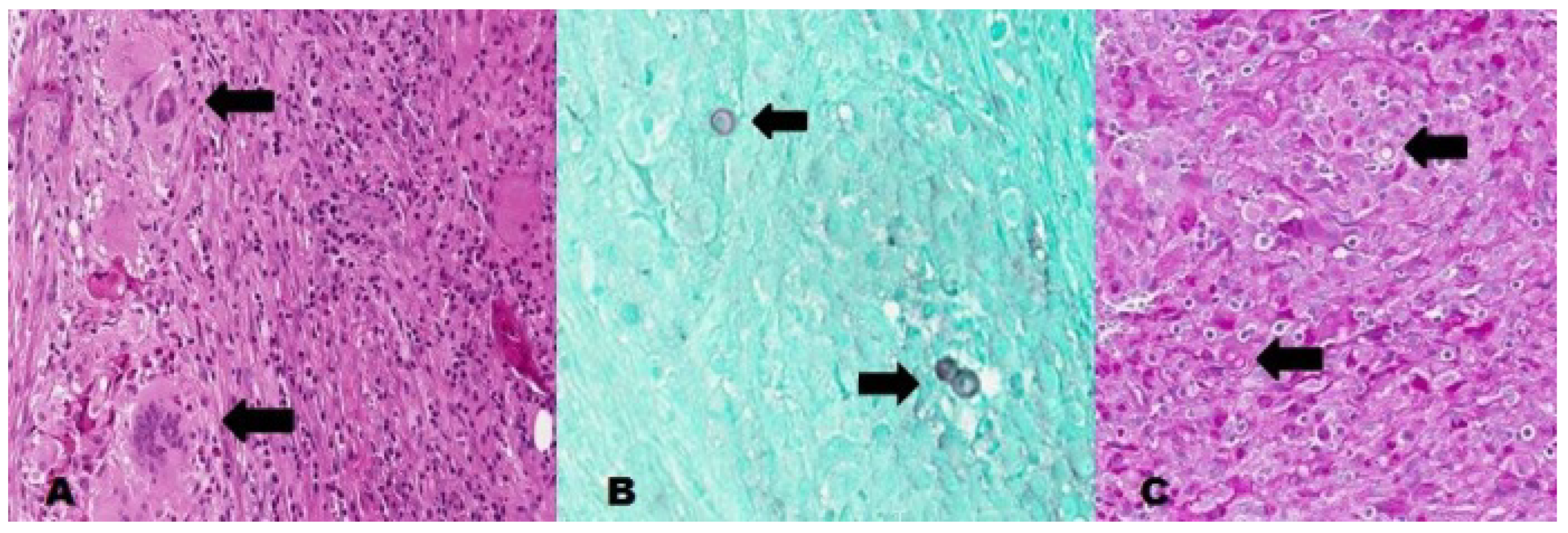

A 28-year-old Caucasian female from Illinois (IL), USA, with past medical history of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) presented to Loyola University Medical Center (LUMC) in Maywood, IL, USA in August 2016 for a 5-month history of right mandibular pain and swelling. She was admitted under the general medicine service. Her symptoms began after a root canal of tooth #30. Due to persistent pain, her dentist placed her on intermittent courses of antibiotics, most recently moxifloxacin 400 mg oral daily and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 875–125 mg oral twice a day of unclear duration. She had also undergone extraction of tooth #30 with no resolution of symptoms. On admission, her temperature was 98.5 °F (36.9 °C), heart rate was 112 beats per minute, and blood pressure was 134/78 mmHg. Physical examination revealed tenderness at the right inferior border of the mandible, edentulous area #30 without bony exposure, drainage or lesions. Laboratory studies showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 13.1 K/µL with 70% granulocytes, sedimentation rate (ESR) of 53 mm/h, and C reactive protein (CRP) of 3.7 mg/dL. A complete metabolic panel was unremarkable. Computed tomography (CT) of the neck with contrast showed right mandibular erosion of the cortex at the lateral margin highly concerning for osteomyelitis. Referral to Oromaxillofacial Surgery (OMFS) was placed with recommendations for outpatient surgical debridement. She received intravenous ampicillin-sulbactam 3 grams (g) every 6 h for 3 days and was then discharged on amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 875–125 mg orally twice a day. Surgical debridement with extraction of tooth #29 was performed 2 days post discharge from the hospital. Tooth #29 was extracted as it was noted to be significantly mobile. Pathological examination revealed fragments of non-viable bone and fibrous tissue with chronic inflammation and reactive changes. No granulomas were observed and no fungal stains were performed. Routine cultures taken intra-operatively grew normal flora. She was then referred to Infectious Diseases for evaluation in September 2016. During this visit she was noted to have a 3.5 × 3.5 cm pink brown cerebriform plaque on the left ventral wrist. The patient reported that this lesion appeared around the same time as her jaw pain had started. Unfortunately, this was not noted during her admission at LUMC in August. She was referred to dermatology for evaluation of her skin lesion to rule out a deep fungal infection. For treatment of her mandibular osteomyelitis, she was started on moxifloxacin 400 mg oral daily for 6 weeks for better bone penetration. Urinary Blastomyces and Histoplasma antigen as well as serum cryptococcal antigen assays were negative. She then underwent a punch biopsy of her arm lesion in October 2016, and specimens were sent for bacterial, acid fast bacilli (AFB) and fungal cultures, as well as for pathological examination. Bacterial cultures showed moderate colonies of coagulase-negative staphylococci and anaerobic Gram-positive cocci which were not speciated. These organisms were ruled out as skin contaminants as her lesion resolved with no directed therapy. AFB and fungal cultures were negative. Pathological examination revealed a dermal scar with mild chronic inflammation. Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and AFB stains did not highlight any fungal or mycobacterial organisms. During this time, she completed her course of moxifloxacin and had clinically improved. Approximately 6 weeks after completing the moxifloxacin course, she presented to an outside emergency department for low-grade fever, progressive jaw swelling and pain. On admission, her temperature was 97.8 °F, heart rate was 95 beats per minute, and her blood pressure was 130/72 mmHg. Physical examination revealed fullness along the right lateral side of face with a palpable ovoid mass approximately 4 × 5 cm, associated with induration, erythema and warmth. No signs of infection were noted intra-orally. Laboratory data showed WBC of 13.7 K/µL with 63% neutrophils, ESR of 74 mm/h, and CRP of 7.2 mg/dL. Her creatinine and liver enzymes were normal and her blood cultures were negative. Imaging of the maxillofacial region by CT-scan revealed a right masseter abscess and associated osteomyelitis of the right mandible with an area of lytic destruction of the right mandibular ramus (Figure 1A–C). She was empirically placed on intravenous vancomycin 2 g every 12 h and piperacillin-tazobactam 3.375 g every 8 h, and was transferred to LUMC on hospital day 3. She eventually underwent right hemimandibulectomy, application of maxillomandibular fixation, and application of rigid internal fixation including condylar head prosthesis for reconstruction of the right hemimandibulectomy defect. Purulence was noted within the medullary space, and marked osteolysis of the right condyle, ramus and coronoid process (Figure 2A,B). Pathology taken from this surgery revealed bone with non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation and scattered neutrophils (Figure 3A). GMS and PAS stains highlighted fungal yeast cells (Figure 3B,C). No malignant cells were identified. Aerobic and anaerobic as well as fungal cultures yielded growth of mold identified as B. dermatitidis by deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequencing. AFB cultures were negative. Plain films of the chest showed no consolidation of the lungs. Her human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antigen and antibody as well as a repeat urine Blastomyces antigen were negative. Antifungal therapy with itraconazole was initiated with a loading dose of 200 mg orally 3 times daily for 3 days followed by 200 mg oral twice a day for a planned 1 year of therapy. She also completed a 6-week course of intravenous ertapenem 1 g daily for possible bacterial infection as intra-operative cultures were obtained after several days of being on broad-spectrum antibiotics. Following the course of ertapenem she was placed on amoxicillin-clavulanate 875–125 mg oral twice a day for chronic suppression in addition to itraconazole due to the presence of mandibular hardware. At 1 and 6-month clinic follow-up with OMFS, the patient reports feeling clinically improved with resolving pain and edema of the right mandible. On examination, there was no evidence of acute infection with the surgical site healing well. Unfortunately, her course has been complicated by persistently elevated inflammatory markers. Her surgical site remained free of evidence of infection. Repeat imaging of the maxillofacial region showed postoperative changes of the right hemimandibulectomy without evidence of infection. Disseminated sites of infection have also been ruled out. She has been evaluated extensively by rheumatology, oncology and infectious diseases. It was concluded that she likely developed a hypersensitivity reaction to the mandibular hardware. A planned definitive reconstruction of the right mandible with a fibular free flap is planned in November 2018.

Figure 1.

Maxillofacial CT with contrast; A. Axial view, bone window: Enlarged right masseter and lytic destruction of the right mandibular ramus (black arrow); B. Axial view, soft tissue window: Enlarged right masseter with loculated abscess, adjacent lytic destruction of the mandibular ramus (black arrow); C. Sagittal view, bone window: Lytic destruction of the right mandibular ramus (black arrow).

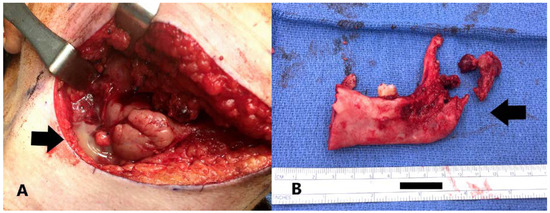

Figure 2.

A. Purulence noted in the submandibular region (black arrow); B. Resected hemi-mandible. Note destruction of the condyle (black arrow).

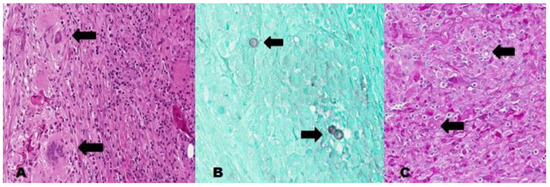

Figure 3.

A. H&E stain, high power showing abundant neutrophils, giant cell reaction, and poorly-formed granulomas (black arrows); B and C. GMS and PAS stains showing yeast forms, some with broad based budding yeasts (black arrows).

Discussion

Osteomyelitis is an inflammatory process of the medulla of the bone [3]. Osteomyelitis of the mandible is rare but is more common than maxillary involvement due to the former’s thin cortical plates and poor vascular supply [4]. Osteomyelitis of the mandible usually arises as a contiguous spread from an odontogenic source, a hematogenous dissemination, or an inoculation during invasive procedures [5]. Predisposing factors leading to mandibular osteomyelitis are malignancy, radiation, certain bone disorders including Paget’s disease and osteoporosis, and immunocompromising conditions such as uncontrolled diabetes mellitus and receipt of immunosuppressive therapy [5,6]. Typical causative agents of mandibular osteomyelitis are those of the normal oral flora as well as bacteria known to cause dental caries and periodontal diseases [7]. Fungal causes of mandibular osteomyelitis are rare, and that caused by Blastomyces are not well-described in the literature.

Blastomyces is thought to be soil-borne and is found in North and South America, Europe, Africa and Asia. Within North America, blastomycosis is endemic in states that border the Mississippi and Ohio River, and the regions around the Great Lakes [8]. It was once known as “Chicago Disease” as many of the earlier cases were identified in Chicago, IL. Blastomycosis is reportable in only a few states in the US. Thus, the incidence rate of blastomycosis in the US is not well established. In 2007, the estimated annual incidence of blastomycosis in IL was 10.7 cases per 1 million persons per year [9]. Wisconsin perhaps has the highest incidence of blastomycosis with annual rates up to 40 cases per 100,000 persons [10]. Blastomyces can infect immunocompetent and immunosuppressed individuals. Pneumonia is the most common clinical presentation of blastomycosis. In a study of 326 cases, 91% had lung involvement, followed by skin (18.1%), and bone (4.3%) [11]. Extra pulmonary involvement results from lymphohematogenous dissemination, although direct inoculation following cutaneous trauma or laboratory injuries have been described [8]. Oppenheimer et al. reviewed 45 patients with osteoarticular blastomycosis: 73% patients had cutaneous involvement, and 64% had evidence of pulmonary disease [12]. Mandibular blastomycosis is not well described in the literature. We reviewed 5 cases of mandibular blastomycosis in North America and summarized their characteristics in the Table 1 [13,14,15,16,17]. In a similar fashion to our patient, most of the patients in the review presented with tooth pain and mandibular swelling. Four of these patients were from the United States, 1 from Canada, and the other from an unknown region of North America. All were diagnosed by pathological examination of the infected specimen but only 4 had growth of Blastomyces in culture. Four had definite or probable evidence of disseminated infection: lungs and skin. Management of blastomycosis was available in only 4 patients, and was noted to be variable.

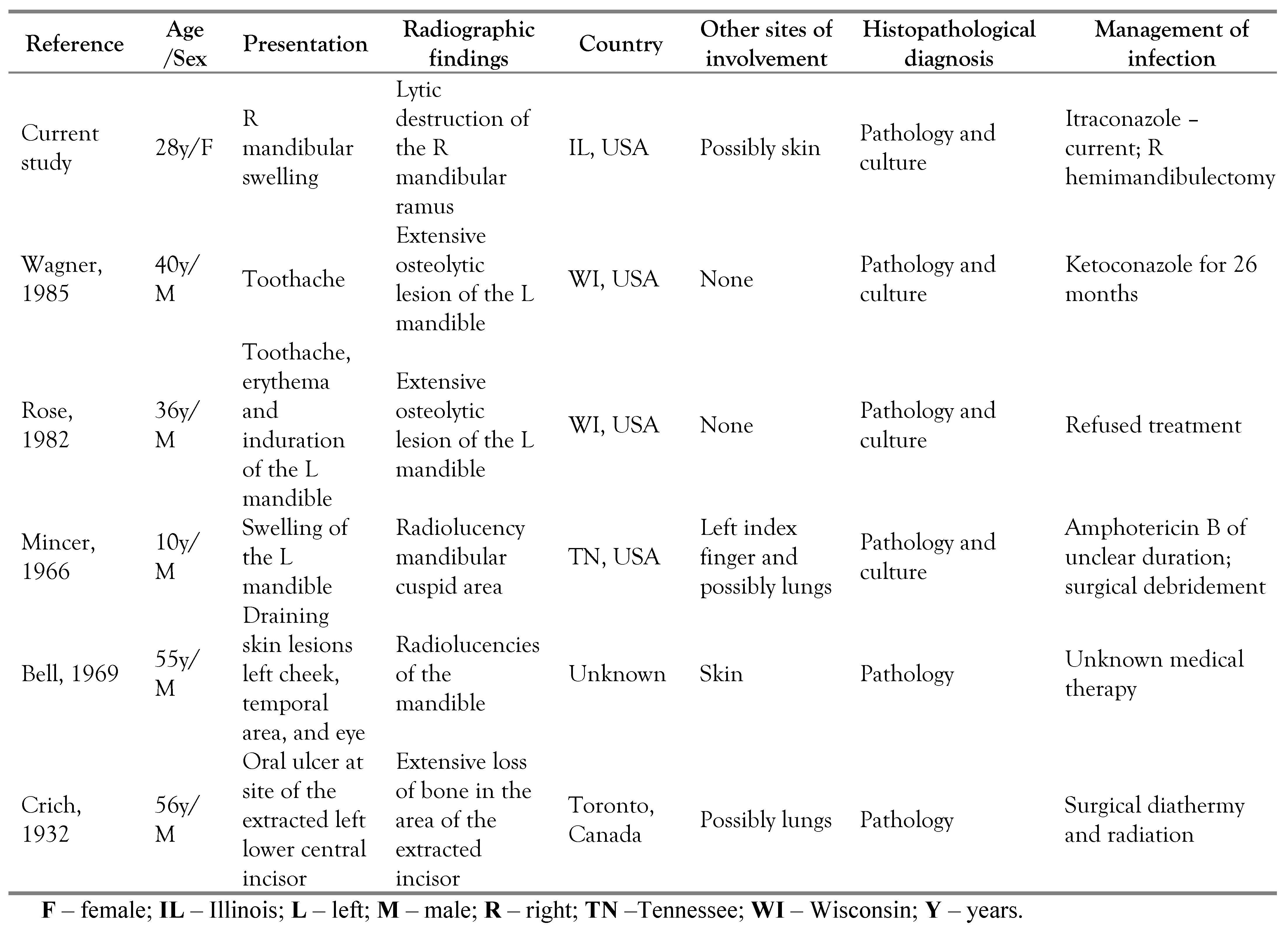

Table 1.

Summary of the characteristics of patients with mandibular blastomycosis.

Table 1.

Summary of the characteristics of patients with mandibular blastomycosis.

|

The clinical presentation for this patient is uncommon, and it remains unclear how she acquired blastomycosis. She improved after initial surgery and a course of antibiotics increasing the suspicion for a bacterial pathogen. She had no prior history of traumatic injury that could explain direct inoculation of the Blastomyces. Moreover, the original surgical pathology and culture were not consistent with Blastomyces infection, although no fungal cultures had been obtained. The patient did not have respiratory symptoms that would indicate the possibility of an initial pneumonia with hematogenous spread at the time of her presentation. Moreover, her chest imaging did not show any evidence of pneumonia. However, some patients with blastomycosis of the lungs present with self-limiting asymptomatic radiographic pulmonary abnormalities that resolve even without therapy [8]. Our patient did have a skin lesion that was suspicious for a deep fungal infection, yet pathology and microbiological results of the skin lesion did not reveal a fungal etiology. Interestingly, she had several negative urine Blastomyces antigen assays. One may speculate that the blastomycosis may represent a sequalae of bacterial mandibular osteomyelitis. Perhaps, she may have had subclinical pulmonary blastomycosis which disseminated to an already damaged mandible. Another theory is reactivation of the blastomycosis. Cases of blastomycosis reactivation at either the lungs or extrapulmonary sites following initial pneumonia with or without therapy have been described [18,19].

Blastomycosis has been considered as a great mimicker as clinical presentations can be similar to other common diseases [8]; thus, diagnosis can be a great challenge, which can potentially lead to fatalities. Between 1990 and 2010, there were 1,216 deaths related to blastomycosis, having a mortality rate of 0.21 per 1 million person-years adjusted by age [20]. Diagnosis can be established via culture and pathological examination of the infected area. Urine Blastomyces antigen can be very helpful in the diagnosis of this disease with a sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 79% [21]. However, cross-reactivity may arise with several fungal infections including histoplasmosis and paracoccidioidomycosis [21], both of which should also be considered in patients with fungal infections of the head and neck. Fortunately for this patient, subsequent mandibular cultures and pathological examination revealed the etiology prompting initiation of appropriate therapy. Treatment options for blastomycosis include amphotericin B or itraconazole, based on the severity of the disease [22]. For mild to moderate disease without central nervous system involvement, itraconazole is preferred due to fewer side effects. For patients with bone and joint blastomycosis, at least 12 months of systemic antifungal therapy is recommended [22].

Conclusion

We report a case of mandibular blastomycosis with no evidence of pulmonary involvement. The patient presented with progressive osteomyelitis of the mandible on radiographic imaging despite therapy for bacterial etiologies. Delay in diagnosis is not uncommon, leading to fatal consequences. In endemic regions, osteoarticular blastomycosis with or without evidence of dissemination should be considered in patients with recurrent or unresolving infections.

Author Contributions

FA and TV were involved in the diagnosis of the case and writing the manuscript. FA and SM supervised patient care. SM provided some of the images. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

None to declare.

Informed Consent Statement

Written consent was obtained from the patient prior to publication.

Conflicts of Interest

FA received grant from Hektoen Institute for Medical Research outside the submitted work. TV and SM—none to disclose.

References

- Bradsher, R.W.; Bariola, J.R. Blastomycosis. In Essentials of Clinical Mycology; Kauffman, C.A., Pappas, P.G., et al., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 337–348. [Google Scholar]

- Rucci, J.; Eisinger, G.; Miranda-Gomez, G.; Nguyen, J. Blastomycosis of the head and neck. Am J Otolaryngol 2014, 35, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Singh, G. Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis of the mandible: A study of 21 cases. Oral Health Dent Manag 2014, 13, 971–974. [Google Scholar]

- Fullmer, J.M.; Scarfe, W.C.; Kushner, G.M.; Alpert, B.; Farman, A.G. Cone beam computed tomographic findings in refractory chronic suppurative osteomyelitis of the mandible. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2007, 45, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.C.; Prasad, S.C.; Mouli, N.; Agarwal, S. Osteomyelitis in the head and neck. Acta Otolaryngol 2007, 127, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeoh, S.C.; MacMahon, S.; Schifter, M. Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis of the mandible: Case report. Aust Dent J 2005, 50, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, M.W.; Chow, A.W. An approach to oral infections and their management. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2005, 7, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccente, M.; Woods, G.L. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010, 23, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, J.A.; Kostiuk, S.L.; Dworkin, M.S.; Johnson, Y.J. Temporal and spatial distribution of blastomycosis cases among humans and dogs in Illinois (2001–2007). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2011, 239, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgardner, D.J.; Buggy, B.P.; Mattson, B.J.; Burdick, J.S.; Ludwig, D. Epidemiology of blastomycosis in a region of high endemicity in north central Wisconsin. Clin Infect Dis 1992, 15, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.W.; Lin, A.C.; Hendricks, K.A.; et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: Epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect 1997, 12, 219–228. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer, M.; Embil, J.M.; Black, B.; et al. Blastomycosis of bones and joints. South Med J 2007, 100, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, D.K.; Varkey, B.; Head, M.D. Blastomycotic osteomyelitis of the mandible: Successful treatment with ketoconazole. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1985, 60, 370–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, H.D.; Gingrass, D.J. Localized oral blastomycosis mimicking actinomycosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1982, 54, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mincer, H.H.; Oglesby, R.J., Jr. Intraoral North American blastomycosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1966, 22, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, W.A.; Gamble, J.; Garrington, G.E. North American blastomycosis with oral lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1969, 28, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crich, A. Blastomycosis of the gingiva and jaw. Can Med Assoc J 1932, 26, 662–665. [Google Scholar]

- Recht, L.D.; Philips, J.R.; Eckman, M.R.; Sarosi, G.A. Self-limited blastomycosis: A report of thirteen cases. Am Rev Respir Dis 1979, 120, 1109–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Bradsher, R.W. Histoplasmosis and blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis 1996, 22 (Suppl. 2), S102–S111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuu, D.; Shafir, S.; Bristow, B.; Sorvillo, F. Blastomycosis mortality rates, United States, 1990–2010. Emerg Infect Dis 2014, 20, 1789–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkin, M.; Witt, J.; LeMonte, A.; Wheat, B.; Connolly, P. Antigen assay with the potential to aid in diagnosis of blastomycosis. J Clin Microbiol 2004, 42, 4873–4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.W.; Dismukes, W.E.; Proia, L.A.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2008, 46, 1801–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).