Abstract

Introduction: The involvement of bacteria in the pathogenesis of biliary tract disease is largely unknown. In this study, we investigated the microbiota of the biliary tissue among adult patients with choledocholithiasis during endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP). Methods: 16S rDNA sequencing of bile samples, culture, and data of the medication history, underlying diseases, and liver function tests were used for the interpretation of differences in the composition of detected bacterial taxa. Results: The four most common phyla in the bile samples included Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes. Infection with anaerobic and microaerophilic bacteria showed host specificity, where Fusobacterium, Prevotella, Veillonella, Propionibacterium, Gemella, and Helicobacter coexist in the same patients. Clostridium and Peptoclostridium spp. were detected in 80% and 86% of the patients, where the highest relative abundance rates were detected in patients with elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels and leukocytosis, respectively. Higher diversity in the bacterial population was detected in patients with common bile duct (CBD) stone, in which the richness of an unclassified member of Alphaproteobacteria plus Helicobacter, Enterobacter/Cronobacter spp., Sphingomonas, Prevotella, Fusobacterium and Aeromonas were detected. Conclusions: Our findings suggested correlations between the presence and relative abundance of several bacterial taxa and CBD stone formation and the effect of medication and underlying diseases on the bile microbial communities. A study on a higher number of bile samples from patients compared with the control group could reveal the role of these bacteria in the pathogenesis of biliary tract disease.

Introduction

Gallstone disease is one of the most common human gastrointestinal diseases with an incidence rate between 5-20% among adults [1]. No 1definite etiological risk factors have been described for the formation of gallstones; however, several factors, including ethnicity, gender (female vs. male), age (advanced vs. younger age), high/low body mass index, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, high-fat-diet, lifestyle factors (e.g., reduced physical activity), socioeconomic status, underlying chronic diseases, such as cystic fibrosis and Crohn’s disease, and drugs (e.g., ceftriaxone) showed epidemiological links that vary between different countries [2].

Most studies have focused on the abnormal metabolism and secretion of bile acids and cholesterol as the primary pathophysiological defect in gallstone formation [3]. Brown-pigmented stones are formed in the common bile duct (CBD), which causes a type of biliary disease known as choledocholithiasis. It is believed that CBD stones, especially brown pigment stones, result from infection with bacteria and parasites/helminths secondary to obstruction [4]. These types of stones could cause recurrent cholangitis and are correlated with primary biliary cirrhosis [5]. Changes in the composition of bile, and disorders such as cholestasis could predispose patients to biliary infection. Following the infection, direct or indirect interaction of bacteria with the biliary tissue (through cell-surface components, like adhesins, or metabolites or enzymes, such as β-glucuronidase, respectively) could promote the formation of cholesterol monohydrate crystals of biliary sludge [5,6]. The microbiota of the upper digestive tract seems to have a major role in this interplay. In patients with underlying disease, it is known that these bacteria themselves can reach the bile duct and the gallbladder; however, little data exist about their identity, either as transient or common members of the gut microbiota [7]. Different types of bacteria, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus faecium, were isolated or detected in the bile or gallstone samples by the culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods [8,9]. It is now well accepted that the vast majority of microbial species are uncultivable and as a result, culture-independent molecular methods are sought to characterize the causative agents of infectious diseases [10]. New data indicated a more complex population of bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract, and their possible contribution to biliary tract diseases is not negligible. 16S ribosomal gene-specific-next generation sequencing (16S rDNA-NGS) is a culture-independent technique used to identify the population and the proportion of bacterial species within an environment, including human biological samples, without any need for isolation or identification by traditional cultural methods [11]. 16S rDNA-NGS technology has improved our understanding of bacterial communities in different human tissues. This technology could improve our understanding of the composition of the gallstone microbiota and its involvement in biliary diseases, which could be explored for the management of hepatobiliary diseases. Accordingly, the objective of the present study was 16S rDNA-NGS analysis of bile samples in symptomatic patients with underlying diseases after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The association of the characterized bacteria with changes in liver function tests and markers of inflammation was also measured in this study.

Methods

Patients and sample collection

Patients suspected to have choledocholithiasis, with related signs and symptoms including jaundice, fever, and epigastric pain were enrolled in this study between August 2015 and October 2016. The ERCP procedure was done in Ayatollah Taleghani Hospital in Tehran, Iran. Patients who received antibiotics one month before the sampling and those with insufficient amount of bile or complications, like primary sclerosing cholangitis, were excluded from the study. Clinical features and demographic data were filled out for all patients through a questionnaire on the day of admission. Written informed consent was also obtained from all the patients under a protocol approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Research Institute for Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases in Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Culture and characterization of the bacterial isolates

Approximately 5 mL of bile samples were collected from the patients in sterile tubes at the time of the examination. The samples were cultured on Blood agar and MacConkey agar media aerobically and also inoculated into thioglycollate medium and Columbia agar at anaerobic conditions. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24-72 hours. Biochemical characterization of the grown colonies was done according to Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology [12].

DNA extraction from bile samples

Bile samples were transported to the laboratory in sterile containers immediately after collection and were subsequently frozen at −20 °C for future analysis. Total DNA was extracted by the phenol-chloroform method as described previously [13]. The extracted DNA was suspended into Tris-EDTA buffer and used as a template for amplification with specific primers (27f: 5′-AGMGTTYGATYMTGGCTCAG-3′ and Eub338-r: 5′-GCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT-3′) [14]. The quality and quantity of DNA extracts were measured by electrophoresis on 1.2% agarose gel and Nanodrop, respectively )Labtech, Palaiseau, France).

16S rDNA sequencing, OTU analysis, alignment, and classification

Library preparation and subsequent paired-end sequencing was conducted according to 16S rDNA sequencing service offered by BGI Genomics Co, China. Mothur pipeline was used for the downstream analyses. Accordingly, reverse and forward reads were combined into contigs using the “make.contigs “command. Subsequently data cleaning was carried out on the resulted contigs employing the “screen.seqs” command. “unique.seqs” command was then used to remove duplicate sequences and the “count.table” of unique sequences was generated applying “count.seqs” command. Afterwards unique sequences were aligned on Silva-V4 reference fasta file followed by running “screen.seqs” to remove poorly aligned reads. After pre-clustering of reads, chimeric sequences resulted from the PCR amplification step were removed from the sequence data using “chimera.vsearch” function. In order to remove non-bacterial sequences “classify.seqs” and “remove.lineage” commands were subsequently applied. OTU picking was carried out using “cluster.split” command based on 97% sequence similarity and taxonomic assignment was determined by “classify.otu” command.

To specify the number of sequences in each sample, “count.groups” was used and then alpha diversity rarefaction curve was generated. Beta diversity was also calculated among 15 samples and its result was visualized in the form of heatmap. For validation purpose, KRAKEN metagenomics pipeline was also employed. FastQ files were fed into the Galaxy bioinformatics pipeline and the following steps were taken to characterize the bacterial composition of each sample. FastQ files were first trimmed using the Trimmomatic program to remove low quality bases from both ends of every read. The trimmed paired files for each sample were then introduced into the Kraken taxonomic sequencing classifier, a sensitive and highly precise algorithm, choosing “Bacteria” as the database used by Kraken. In brief, Kraken searches for k-mers within each read in a database of k-mers and tries to assign the lowest common ancestor (LCA) to each k-mer in a taxonomic tree for all genomes that contain that k-mer. A single taxonomic label is subsequently assigned to each read following an analysis of the set of LCA that corresponds to all k-mers constituting each read. The Kraken report program was then used to get the number of reads covered by the clade rooted at each specified taxon and also the number of reads assigned directly to this taxon.

Results

Patients and infection

Among patients who underwent the ERCP procedure, an appropriate amount of bile samples for the conventional microbiological and molecular assays was obtained from the common bile ducts of 15 patients (males, 6 and females, 9) with a mean age of 52.4±18.7 years. CBD stone was detected in 60% (9/15) of the patients. The other complications included jaundice (2/15), epigastric pain (2/15), and fever of unknown origin (1/15). Hydatid cyst was reported in one febrile patient. Underlying diseases included diabetes mellitus (3/15), pancreatic cancer (3/15), incomplete cholecystectomy (2/15), sphincterotomy (1/15), chronic kidney disease (1/15), ischemic heart disease (1/15), and hypertension (3/15). Based on the culture method, infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and E. coli was detected in 33.3% (5/15) and 13.3% (2/15) of the patients, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Diversity of cultivable bacteria in bile samples of patients with distinct types of underlying diseases after endoscopic retrograde cholangiography.

16S rDNA sequencing

Out of 14.4-55.5 Mbp raw data, 402075 pairs of reads were recovered following the 16S rDNA-NGS sequencing after trimming, filtering and binning (mean length: 300 bp), ranging from 13911 to 47952 sequences per sample (average 26805 tags). OTU assignment with Mothur showed a total of 181 OTUs with an OTU coverage of 99.9%±0.05% (mean±standard deviation – SD) (Supplementary Figure 3). Dominant phyla across these samples, as was determined by Kraken, included Proteobacteria (100%, 15/15), Firmicutes (100%, 15/15), Actinobacteria (100%, 15/15), Bacteroidetes (93.3%, 14/15), Cyanobacteria/Chloroplast (73.3%, 11/15), Fusobacteria (73.3%, 11/15), Acidobacteria (46.6%, 7/15), and Deinococcus-Thermus (26.6%, 4/15) (Figure 1).

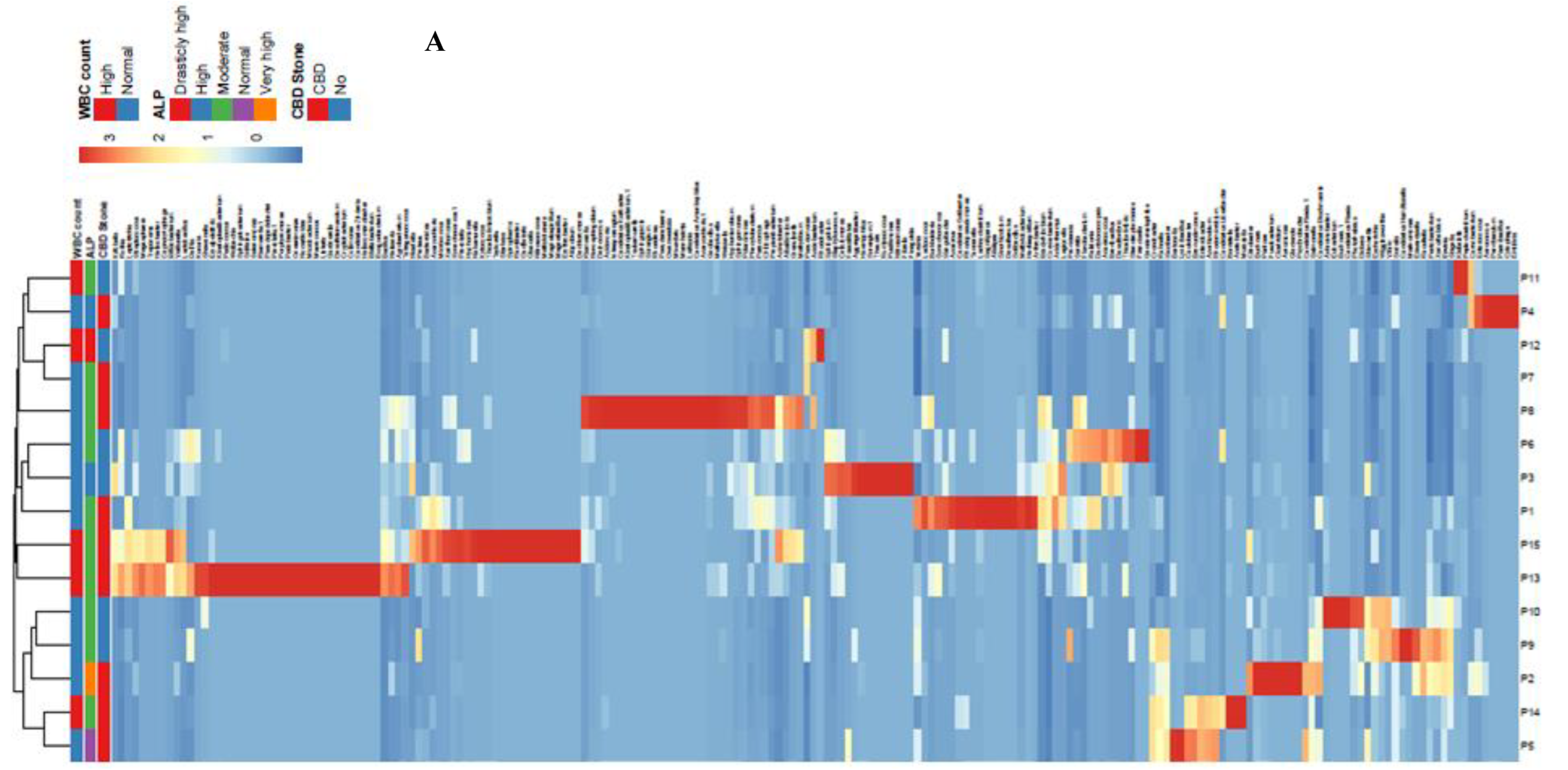

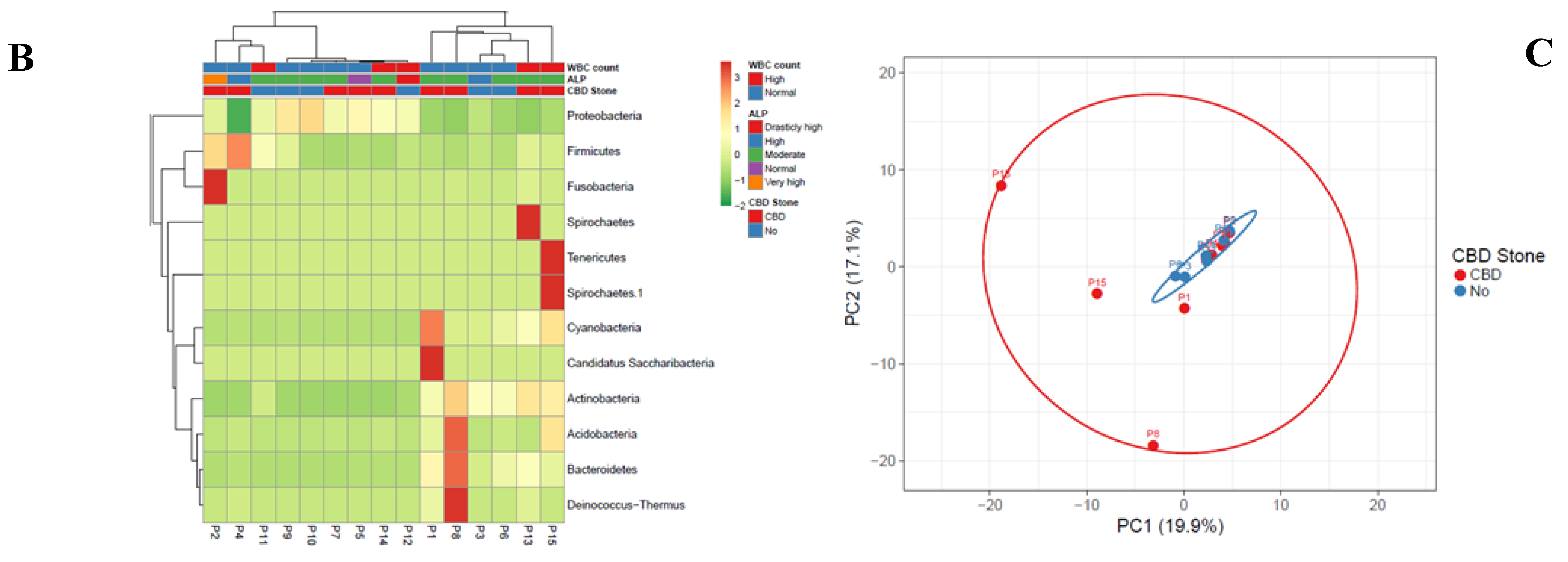

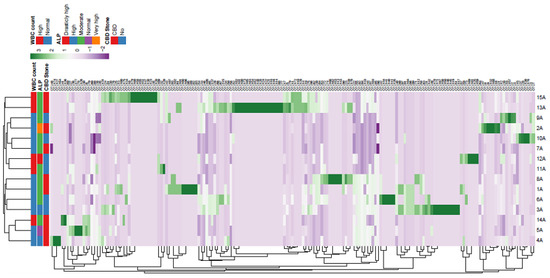

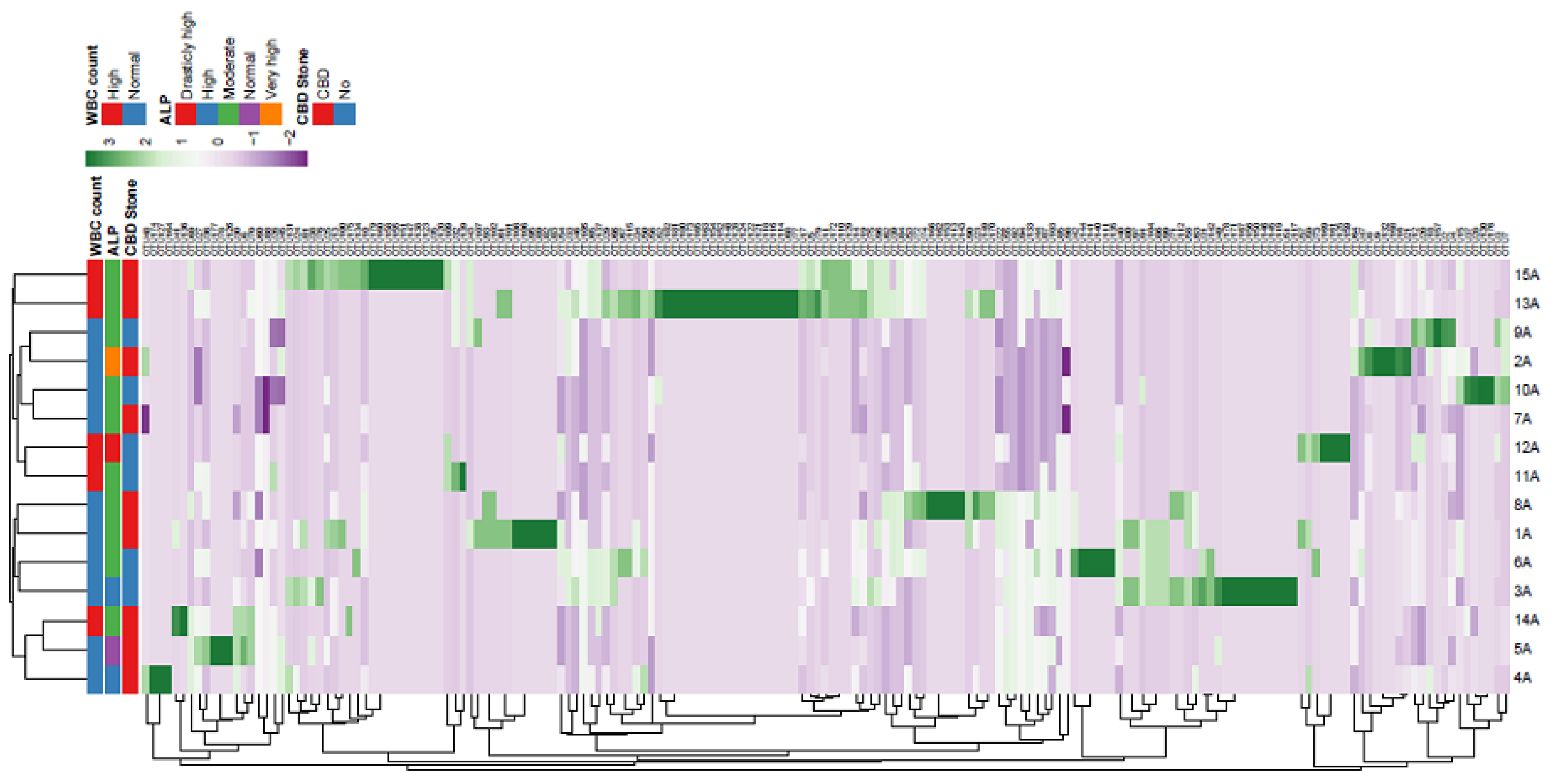

Figure 1.

Heatmap and clustering for multivariable data of bacterial genera (A) and phyla (B) characterized in bile samples of patients with biliary diseases. Communities of the bacterial genera were clustered using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) of the unweighted UniFrac distance matrix (C). Unit variance scaling was applied to rows; SVD with imputation was used to calculate principal components. X and Y axis show principal component 1 (PC1) and principal component 2 (PC2) that explain 19.9% and 17.1% of the total variance, respectively. N=15 data points. Each point corresponds to a community colored according to existence of CBD (red = yes; blue = no). The percentage of variation explained by the plotted principal coordinates is indicated on the axes.

Statistical analysis showed no correlation among total numbers of the reads for bacterial phyla and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels and white blood cell (WBC) counts in the patients. Moreover, no significant difference was detected between the presence and numbers of reads between patients with CBD stone and those with no stone. Proteobacteria (mean±SD of 23877.3±13197) and Firmicutes (3427.7±4803) were among the most frequent phyla in the studied bile samples (Table 2). While patients with diabetes and CBD stone showed the highest amounts of Firmicutes (CBD vs. non-CBD stone, mean number of reads±SD of 4064±5932 vs. 2364±2366, respectively), the highest count of Proteobacteria was measured in a patient with sphincterotomy. Pseudomonas spp. constituted the highest population of the bacterial genera in patients with a history of cholecystectomy, sphincterotomy, pancreatic cancer, and hydatid cyst. Pseudomonas spp., Achromobacter, and Klebsiella in patient with sphincterotomy, Pseudomonas+Stenotrophomonas together with Enterococcus and Klebsiella in patients with pancreatic cancer, and Pseudomonas together with Cronobacter, Enterobacter, and Caulobacter in patients with cholecystectomy were among the dominant genera with the highest number of reads in the studied samples. Bacterial genera confirmed in all the bile samples included Cronobacter, Pseudomonas, Enterococcus, Achromobacter, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter spp. The most common bacteria were as follows: Cronobacter, Pseudomonas, Escherichia/Shigella, Enterococcus, Sphingomonas, Achromobacter, Klebsiella, Morganella, Stenotrophomonas, Streptococcus, Brevundimonas, Lactobacillus, Burkholderia, and Clostridium spp. Infection with anaerobic and microaerophilic bacteria showed host specificity. Accordingly, Fusobacter, Prevotella, Veillonella, Propionibacter, Gemella, and Helicobacter co-existed in the same patients. The coexistence of anaerobic bacteria, mainly Clostridium, Fusobacter, Veillonella, Propionibacterium, Peptoclostridium, Tannerella, and Prevotella, was mainly detected in patients with pancreatic cancer (P6, P3, and P15); however, this presence was also detected in patients with CBD stone (P13) and a patient with sphincterotomy (P10). Clostridium and Peptoclostridium spp. were detected in 80% and 86% of the patients, where the highest relative abundance rates were detected in patients with elevated ALP levels and WBC counts, respectively. In patients with elevated white blood count (WBC), a higher rate of colonization with Pseudomonas, Cronobacter, Enterococcus, Klebsiella, Peptoclostridium, and Streptococcus were measured. H. pylori was detected in 4 patients with CBD stone (4/9, 44.4%) and 1 patient with no CBD stone (1/6, 16.6%).

Table 2.

The number of paired reads for the characterized bacterial phyla in bile samples of patients with biliary diseases.

Analysis of OTUs at the species level showed dominance of the following species with >100 reads per sample: P. putida (12/15), S. maltophilia (11/15), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (10/15), Pseudomonas stutzeri group (6/15), Achromobacter xylosoxidans (6/15), Acinetobacter calcoaceticus/baumannii complex (5/15), Chitinophaga pinensis (4/15), Enterococcus hairae (4/15), Sphingomonas wittichii (4/15), Burkholderia genera incertae (3/15), E. casseliflavus (2/15), Streptococcus anginosus (2/15), Fusobacterium nucleatum (2/15), Haemophilus parasuis (2/15), H. parainfluenzae (2/15), Veillonella parvula (2/15), Alkalilimnicola ehrlichii (2/15), Prevotella melaninogenica (2/15), Sphingopyxis alaskensis (1/15), Aeromonas veronii (1/15), Providencia stuartii (1/15), Brevundimonas subvibrioides (1/15), Rothia dentocariosa (1/15), Novosphingobium aromaticivorans (1/15), Serratia marcescens (1/15), and K. pneumoniae (1/15).

Effects on richness and diversity

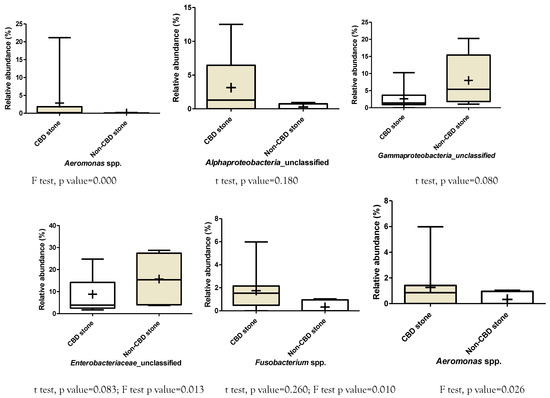

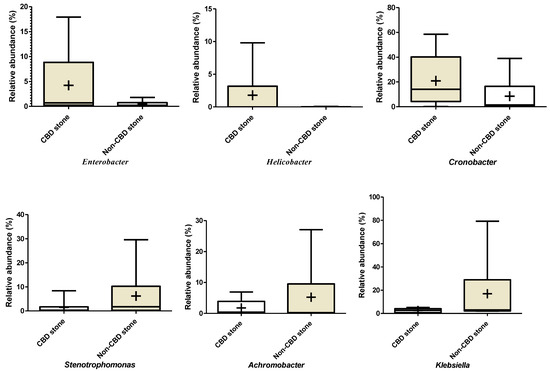

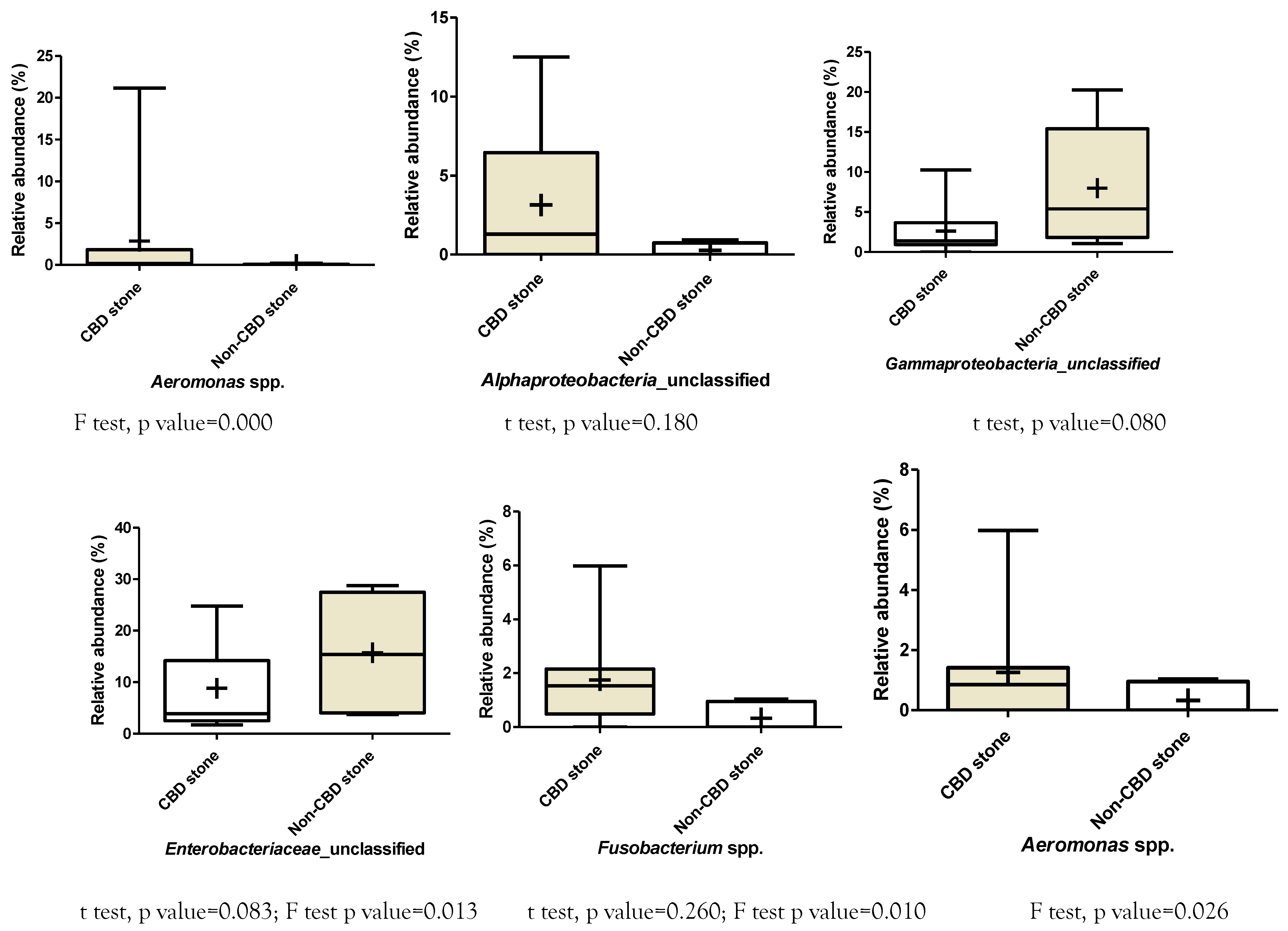

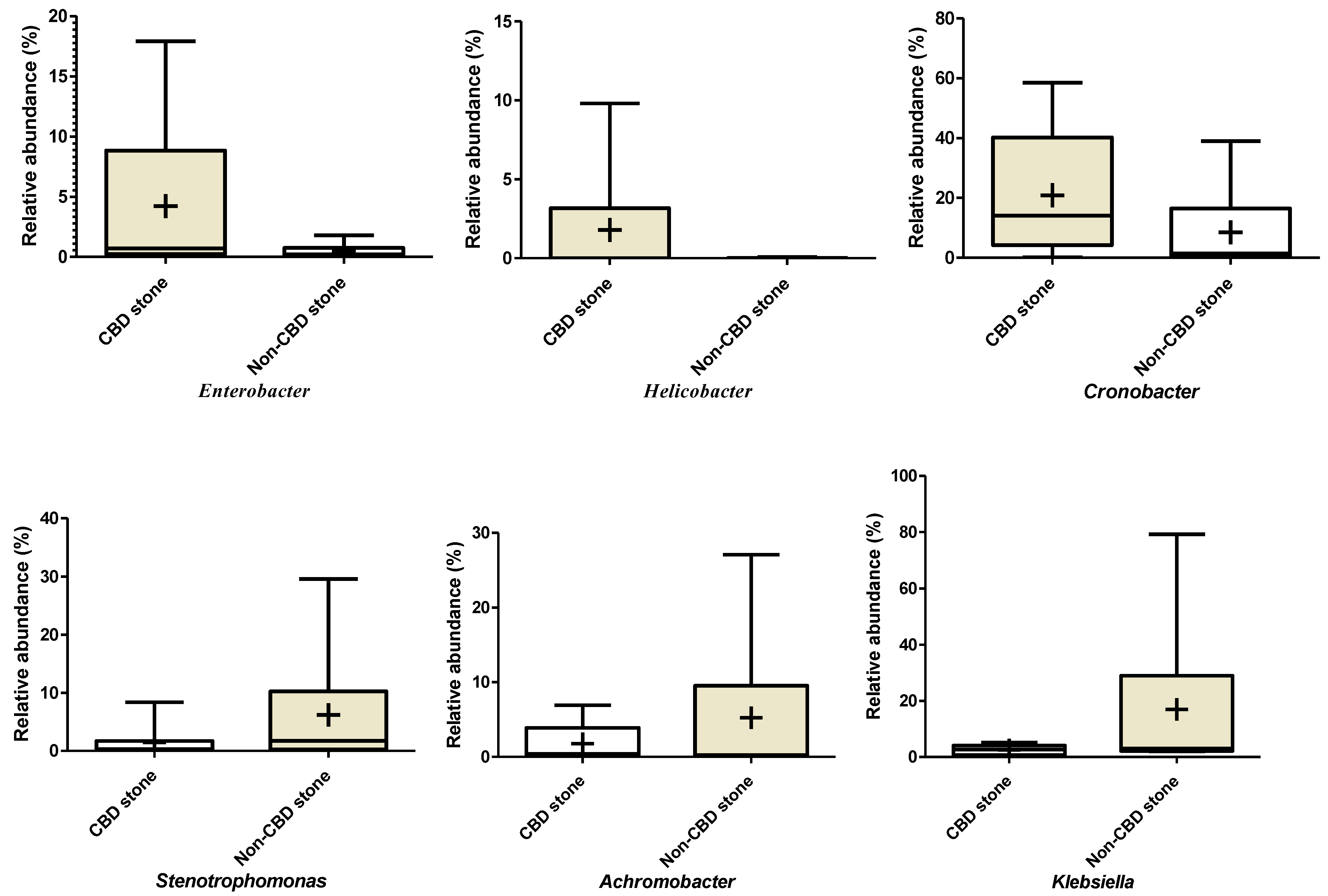

Enrichment of some of the bacterial genera in patients with CBD stone compared with non-CBD stone were detected based on the measured relative abundance rates. Accordingly, based on the Kraken results, Helicobacter, and Enterobacter/Cronobacter spp. were among the more frequent genera that were observed in patients with CBD stone. While mean values of the relative abundance rates did not show significant difference, variances of the two bacterial genera were significantly different (p<0.000, Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 2). Similarly, this difference was also confirmed in the cases of Sphingomonas (p=0.003), Prevotella (p=0.009), Fusobacterium (p<0.000) and Aeromonas (p<0.000). Klebsiella, Stenotrophomonas and Achromobacter spp. showed higher relative abundance rates in patients with no CBD stone (p<0.000 and 0.000, respectively). Results of Mothur showed richness of an unclassified member of Alphaproteobacteria, and Helicobacter, Prevotella, Fusobacterium and Aeromonas in patients with CBD stone, while unclassified members of Pseudomonadaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, and Gammaproteobacteria were enriched in the non-CBD stone group (Table 3). The bacterial taxa showed higher diversity in patients with CBD stone (158/181, 87.3%), compared with the non-CBD stone patients (120/181, 66.3%).

Table 3.

Differences in the relative abundance of the main bacterial OTUs were calculated using Mothur in patients with CBD stones and those with no CBD stones.

Discussion

It is assumed that a combination of risk factors, including genetic background, anatomical, physiological, and immunological disorders, history of medications, and composition of the gut microbiota could mediate distinct types of diseases in the biliary system. The ability of microbes to interact with the biliary tract, and the production of toxins, metabolites, and enzymes possibly play roles in the promotion of these disorders. Recent progresses in the development of advanced technologies for DNA sequencing have provided us with the opportunity to better analyze common members of the microbiome in association with this system, and to study their involvement in related disorders. The primary purpose of this study was to analyze the composition of the bile microbiota in patients with biliary tract diseases using 16S rDNA sequencing, and their correlation with CBD stone formation, the elevated WBC count, and ALP level was investigated. Accordingly, a high level of diversity in the composition of the bile microbiome was revealed in the studied samples. While this analysis confirmed the existence of P. aeruginosa as one of the most prevalent bacteria in the biliary tract, which was also in accordance with the results of the culture-based method, most of the cases showed mixed-type infection by a variety of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. The results showed no statistically significant difference in the composition of the bacteria phyla and genera between the patients with and without CBD stone. The most common phyla in our samples included Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Cyanobacteria and Fusobacteria, respectively. In a study by Ye F. et al., all of these phyla plus Synergistetes and TM7 were characterized in bile samples of patients with choledocholithiasis [15]. Existence of Cyanobacteria, as was shown in our study, was similarly reported in a study on bile samples of patients with gallbladder stones [16]. Regardless of the status of CBD stone formation and underlying diseases in the studied patients, more frequent genera of the bacteria in the bile samples included Cronobacter, Pseudomonas, Chitinophaga, Enterococcus, Sphingomonas, Achromobacter, Klebsiella, Aeromonas, Providencia, Stenotrophomonas, Synechococcus, Bradyrhizobium, Acinetobacter, Enterobacter, Lactococcus, Methylobacterium, Bacillus, Propionibacterium, Peptoclostridium, Alkalilimnicola, and Streptococcus. These genera showed completely different patterns in comparison to those characterized by Ye F. et al., so that Prevotella, Streptococcus, Veillonella, Fusobacterium, Haemophilus, Neisseria, and E. coli and Klebsiella, Pyramidobacter, Enterococcus, Fusobacterium, Streptococcus, and Veillonella were dominant, respectively [15]. Although our results did not show a significant difference in the characterized bacterial genera in the bile samples of patients with and without bile duct stone, this association for gallstone was shown in the study of Wu et al. They showed this association for Lactococcus, Bacteroides, Caulobacter, Propionibacterium, Clostridium, Staphylococcus, Acinetobacter, Anoxybacillus, Arthrobacter, Cahryseobacterium, and E. coli [16]. The presence of some bacterial genera in the studied bile samples, such as those that are linked with the oral and upper respiratory tract (e.g., Veillonella, Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus, Prevotella, Haemophilus, Neisseria, Legionella, Bordetella, Pseudomonas, and Prevotella), those colonizing the gastric tissue (Helicobacter, Lactobacillus, Leptotrichia, and Streptococcus), beside common enteric pathogens (e.g., Yersinia, Salmonella, C. difficile, C. perfringens), proposed the biliary tract as a suitable niche for the colonization and possibly pathogenesis of these bacteria. Our results showed the preference for Cronobacter, Pseudomonas, and Enterococcus for colonization and proliferation in the biliary tract, as higher numbers of their sequence reads were detected. Cronobacter sakazakii could produce exopolysaccharide, which forms biofilm and also encodes active efflux pumps that mediate resistance to bile salts [17]. This property in A. baumannii could also mediate resistance to bile salts [18]. In the case of Enterococcus, a permease protein (GltK), which is a glutamate/aspartate transport system, is responsible for its resistance to bile salts. In the case of Salmonella, upregulation of genes, including RpoS-dependent and independent stress response genes, biofilm formation, the outer membrane, the cytoplasmic membrane, efflux pump systems, genes of the multiple antibiotic resistance (mar) and PhoPQ regulons, and those mediating DNA repair functions, play a crucial role in bile resistance [19]. The resistance property of these bacteria to bile salts could facilitate their persistent residence, promotion of the infection and pathogenesis, stone formation through precipitation of bile salts, induction of inflammatory response, or DNA damage. Some of the bacteria could deconjugate bilirubin, leading to their precipitation as calcium salts. Deconjugation of bile salts could be caused by bacterial bile salt hydrolases, and their presence in Lactobacillus, Enterococcus, Bifidobacterium, Bacteroides, Methanobrevibacter, Methanosphera, and Clostridium was established [20]. Oxidation and epimerization of bile salts, which generates isobile (β-hydroxy) salts, is also mediated by some of the enteric bacteria that were characterized in our studied bile samples, including Clostridium, Peptostreptococcus, Bacteroides, Eubacterium, and Escherichia coli [20].

The ability of bacteria to secrete enzymes, such as β-glucuronidase, phospholipases, bile acid hydrolases, and urease, is involved in gallstone formation and calcium salts precipitation [16,21]. In our study, we characterized urease-producing bacteria, including Clostridium, Corynebacterium, Citrobacter, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Morganella, Proteus, Providencia, Haemophilus, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Yersinia, Pseudomonas, and Helicobacter in bile samples of the patients; however, no significant difference in their relative abundance was detected, except for Enterobacter (>8 fold) and Helicobacter (>240 fold) that showed higher mean values in patients with CBD stone. There are contrary reports about the involvement of Helicobacter spp. in biliary tract diseases. In a study by Jahani Sherafat S. et al., Helicobacter pylori was detected in 2.7% of patients with gallstones, which was lower than those reported before by Fatemi SM. et al (14.3%) [22,23]. This involvement was not limited to gallstone disease, but also confirmed among patients with hepatolithiasis (53%), and those with choledocholithiasis (47%) [24]. Interestingly, in our study, patients with H. pylori infection (P1, P8, P13, P15, P6) showed a more complex microbiome compared with H. pylori-negative patients. This finding was supported by other studies in humans or animals, where coinfection with several bacteria, including Helicobacter spp., was determined as a prerequisite for induction of cholesterol gallstones [16,21]. It is not clear yet how urease can promote gallstone formation in cooperation with other bacteria. In animal models, it was shown that coinfection with several bacteria could develop cholesterol gallstones at a higher level than the cases infected with a single bacterial genus (80% vs 40%) [16].

Beta-glucuronidase, the other bacterial enzyme that is linked with gallbladder and CBD stone formation, is encoded by Bacteroides, Clostridium perfringens, some members of Enterobacteriaceae (e.g., Escherichia coli), Firmicutes (e.g., Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Clostridium, Ruminococcus, Roseburia, and Faecalibacterium), a species of Actinobacteria (Bifidobacterium dentium), Anaerococcus prevotii, and Desulfitobacterium hafniense [25]. In our study, among the noted bacteria, the highest amounts of sequence reads in patients with CBD stone were related to Bacteroides, C. perfringens, Lactobacillus, Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Clostridium spp., and Bifidobacterium; however, they were also present in patients with non-CBD stone in lower abundances.

Our results at the species level showed the existence of Sphingomonas wittichii, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia group, Chitinophaga pinensis, Providencia stuartii, together with Pseudomonas putida group, Pseudomonas stutzeri subgroup, Pseudomonas aeruginosa group, Enterococcus hirae, Achromobacter xylosoxidans, Brevundimonas subvibrioides, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus/baumannii complex, Veillonella parvula, and Prevotella melaninogenica in amounts >100 reads per sample. High counts of these bacteria showed their ability for colonization, which promote their probable interaction with the biliary system. Further studies are needed to determine mechanisms that are used by these bacteria for tolerating bile salts and to characterize virulence factors promoting their pathogenicity.

A comparison of analysis methods by Mothor and Kraken showed a congruency between the results. Enrichment of an unclassified member of Alphaproteobacteria, which was characterized by Mothur, was in accordance with a higher abundance of Sphingomonas (a member of this phylum that was determined by the Kraken) in patients with CBD stone. Similarly, the dominance of unclassified members of Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonadaceae, as was detected by Mothur, in non-CBD stone samples were in congruence with the abundance of Klebsiella and Pseudomonas spp. that were detected by Kraken in the non-CBD stone group, respectively. Despite this similarity, Kraken showed a preference for detection of higher numbers of OTUs, genera of the bacteria (202 vs. 181 genera), and ability for characterization of some of the sequences at species level.

Conclusions

In general, 16S rDNA analysis showed high level of diversity in the composition of the bile microbiome, which mainly included uncultivable and fastidious bacteria. Higher relative abundance rates of some bacterial taxa in association to the formation of CBD stone and elevated ALP and WBC levels were detected in the patients; however, the presence of these bacteria showed no statistically significant difference compared to patients with no CBD stone. These results showed the impact of underlying diseases, such as cholecystectomy, sphincterotomy, and pancreatic cancer on the bacterial composition of the biliary tract; however, performing this experiment with a larger number of patients will help to suggest an actual correlation between the presence of specific bacterial communities and disease phenotype.

Supplementary Materials

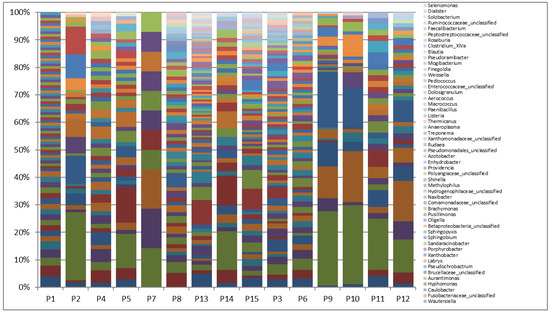

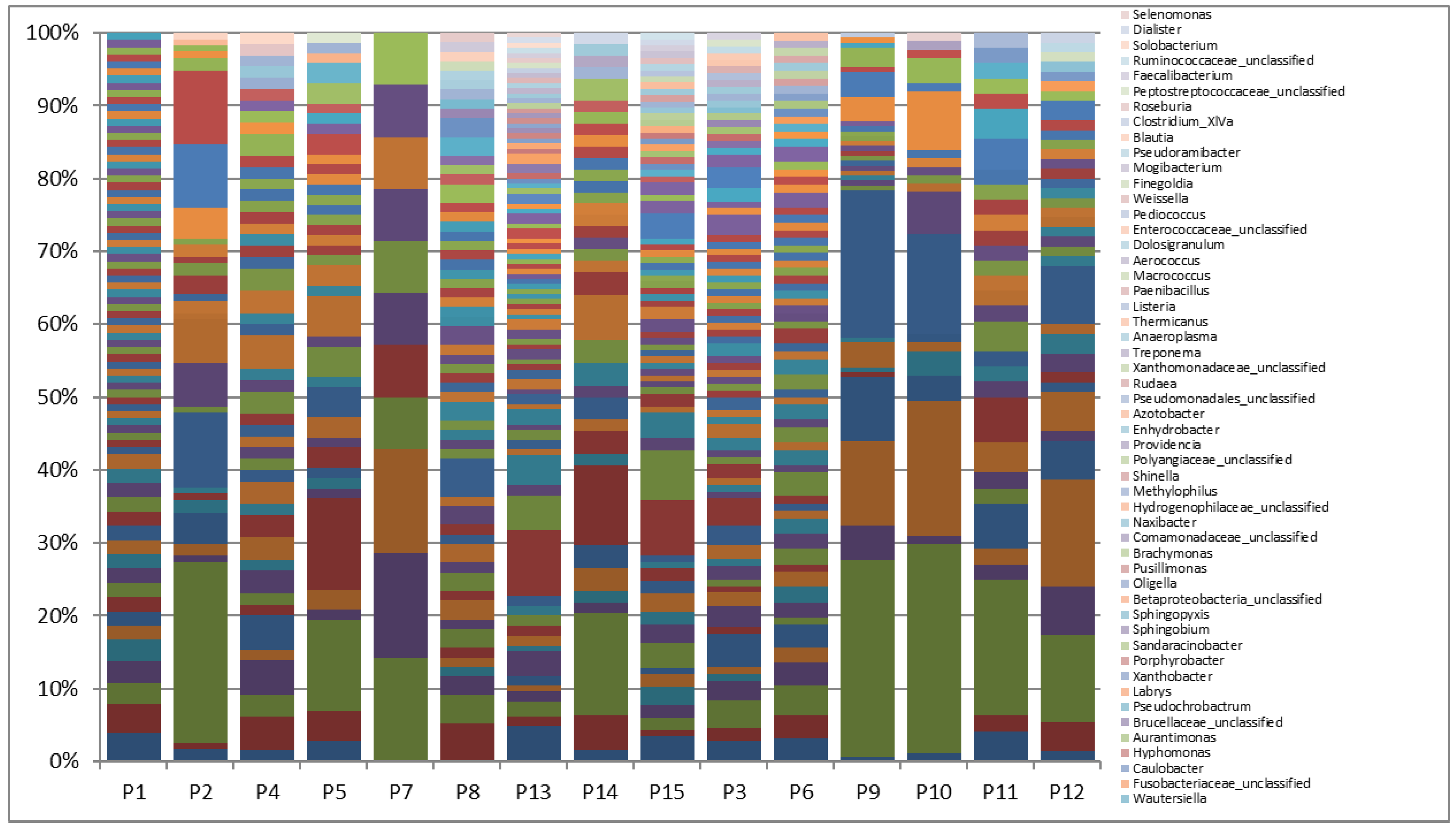

Supplementary Figure 1.

Relative abundance of bacterial genera in bile samples of symptomatic patients with CBD vs. non-CBD stone formers. Legend: Patients with CBD stone: P1, P2, P4, P5, P7, P8, P13, P14, P15. Patients with no CBD stone: P3, P6, P9-P12. The analysis was done using Mothur.

Supplementary Figure 1.

Relative abundance of bacterial genera in bile samples of symptomatic patients with CBD vs. non-CBD stone formers. Legend: Patients with CBD stone: P1, P2, P4, P5, P7, P8, P13, P14, P15. Patients with no CBD stone: P3, P6, P9-P12. The analysis was done using Mothur.

Supplementary Figure 2.

Differences in relative abundances of bacterial genera between symptomatic patients with common bile duct stone and non-CBD stone formers. Klebsiella: p values for unpaired t test: 0.170, F test: 0.000. Achromobacter: p values for unpaired t test: 0.360, F test: 0.001. Cronobacter: p values for unpaired t test: 0.240, F test: not significant. Helicobacter: p values for unpaired t test: 0.250, F test: 0.000. Enterobacter: p values for unpaired t test: 0.240, F test: 0.000. Stenotrophomonas: p values for unpaired t test: 0.250, F test: 0.000.

Supplementary Figure 2.

Differences in relative abundances of bacterial genera between symptomatic patients with common bile duct stone and non-CBD stone formers. Klebsiella: p values for unpaired t test: 0.170, F test: 0.000. Achromobacter: p values for unpaired t test: 0.360, F test: 0.001. Cronobacter: p values for unpaired t test: 0.240, F test: not significant. Helicobacter: p values for unpaired t test: 0.250, F test: 0.000. Enterobacter: p values for unpaired t test: 0.240, F test: 0.000. Stenotrophomonas: p values for unpaired t test: 0.250, F test: 0.000.

Supplementary Figure 3.

Heatmap and cluster analysis of OTU in bile samples of patients with biliary diseases. Legend: ID of patients is shown in Y axis. Presence of common bile duct (CBD) stone, and levels of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and white blood cell (WBC) counts are shown for each sample. Diversity in no. of each OUT is shown by different color range. The average method was used for cluster analysis.

Supplementary Figure 3.

Heatmap and cluster analysis of OTU in bile samples of patients with biliary diseases. Legend: ID of patients is shown in Y axis. Presence of common bile duct (CBD) stone, and levels of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and white blood cell (WBC) counts are shown for each sample. Diversity in no. of each OUT is shown by different color range. The average method was used for cluster analysis.

Author Contributions

MA conceived the study. NH and MA oversaw and analyzed the 16S rDNA gene sequencing and data analysis. AS, MAR, and SZM provide the samples and related clinical data. MAR cultured the samples and performed laboratory experiments. NH and MA contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Collecting and analyzing studies is funded by the Research Institute for Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. The process of preparing reports and publications does not get funding from outside.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Research Institute for Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases in Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. Informed consent form was signed by all the participants before the ERCP procedure.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the endoscopic retrograde cholangiography unit of Ayatollah Taleghani hospital for their cooperation in this study. All authors have read the journal’s authorship agreement and the final manuscript has been approved by all named authors.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors – none to declare.

References

- Bansal, A.; Akhtar, M.; Bansal, A.K. A clinical study: prevalence and management of cholelithiasis. Int Surg J 2014, 1, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinton, L.M.; Shaffer, E.A. Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer. Gut Liver 2012, 6, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Q.; Cohen, D.E.; Carey, M.C. Biliary lipids and cholesterol gallstone disease. J Lipid Res 2009, 50 (Suppl), S406–S411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vítek, L.; Carey, M.C. New pathophysiological concepts underlying pathogenesis of pigment gallstones. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2012, 36, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reshetnyak, V.I. Concept of the pathogenesis and treatment of cholelithiasis. World J Hepatol 2012, 4, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.H.; Portincasa, P.; Liu, M.; Tso, P.; Wang, D.Q. Similarities and differences between biliary sludge and microlithiasis: their clinical and pathophysiological significances. Liver Res 2018, 2, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrov, V.A.; Fernández-Peralbo, M.A.; Derks, R.; et al. Biliary microbiota and bile acids composition in cholelithiasis. Biomed Res Int 2020, 1242364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; De Waha, P.; Hapfelmeier, A.; et al. Risk factors for increased antimicrobial resistance: a retrospective analysis of 309 acute cholangitis episodes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014, 69, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swidsinski, A.; Khilkin, M.; Pahlig, H.; Swidsinski, S.; Priem, F. Time dependent changes in the concentration and type of bacterial sequences found in cholesterol gallstones. Hepatology 1998, 27, 662–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaletti, L.; Monciardini, P.; Bamonte, R.; et al. New lineage of filamentous, spore-forming, gram-positive bacteria from soil. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006, 72, 4360–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salipante, S.J.; Sengupta, D.J.; Rosenthal, C.; et al. Rapid 16S rRNA next-generation sequencing of polymicrobial clinical samples for diagnosis of complex bacterial infections. PLoS One 2013, 8, e65226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, J.G.; Williams, S.T.; Holt. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology, Vol. 4; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J.; Russell, D.W. Purification of nucleic acids by extraction with phenol: chloroform. CSH Protoc 2006, pdb.prot4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.W.; Martin, J.C.; Scott, P.; Parkhill, J.; Flint, H.J.; Scott, K.P. 16S rRNA gene-based profiling of the human infant gut microbiota is strongly influenced by sample processing and PCR primer choice. Microbiome 2015, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Shen, H.; Li, Z.; et al. Influence of the biliary system on biliary bacteria revealed by bacterial communities of the human biliary and upper digestive tracts. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0150519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, B.; et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis and bacterial community assembly associated with cholesterol gallstones in large-scale study. BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, B.; Cooney, S.; O’Brien, S.; et al. Cronobacter (Enterobacter sakazakii): An opportunistic foodborne pathogen. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2009, 7, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Blasco, L.; Gato, E.; et al. Response to bile salts in clinical strains of Acinetobacter baumannii lacking the AdeABC efflux pump: virulence associated with quorum sensing. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017, 7, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, S.B.; Cota, I.; Ducret, A.; Aussel, L.; Casadesús, J. Adaptation and preadaptation of Salmonella enterica to bile. PLoS Genet 2012, 8, e1002459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urdaneta, V.; Casadesús, J. Interactions between bacteria and bile salts in the gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary tracts. Frontiers in Medicine 2017, 4, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belzer, C.; Kusters, J.G.; Kuipers, E.J.; van Vliet, A.H. Urease induced calcium precipitation by Helicobacter species may initiate gallstone formation. Gut 2006, 55, 1678–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahani Sherafat, S.; Tajeddin, E.; Reza Seyyed Majidi, M.; et al. Lack of association between Helicobacter pylori infection and biliary tract diseases. Pol J Microbiol 2012, 61, 319–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatemi, S.M.; Doosti, A.; Shokri, D.; Ghorbani-Dalini, S.; et al. Is there a correlation between Helicobacter pylori and enterohepatic Helicobacter species and gallstone cholecystitis? Middle East J Dig Dis 2018, 10, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dar, M.Y.; Ali, S.; Raina, A.H.; et al. Association of Helicobacter pylori with hepatobiliary stone disease, a prospective case control study. Indian J Gastroenterol 2016, 35, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Cholesterol gallstones and bile host diverse bacterial communities with potential to promote the formation of gallstones. Microb Pathog 2015, 83–84, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© GERMS 2023.