Abstract

A critical review on the synthesis, characterization, and modeling of polymer grafting is presented. Although the motivation stemmed from grafting synthetic polymers onto lignocellulosic biopolymers, a comprehensive overview is also provided on the chemical grafting, characterization, and processing of grafted materials of different types, including synthetic backbones. Although polymer grafting has been studied for many decades—and so has the modeling of polymer branching and crosslinking for that matter, thereby reaching a good level of understanding in order to describe existing branching/crosslinking systems—polymer grafting has remained behind in modeling efforts. Areas of opportunity for further study are suggested within this review.

1. Introduction

Graft copolymers consist of branches of polymer segments covalently bonded to primary polymer chains. Graft copolymers containing a single branch are known as miktoarm star copolymers. The backbone and branches can be homo- or copolymers with different chemical structures or compositions [1]. However, if the polymer molecule is a homopolymer, the reaction route to produce the branches is known as polymer branching; polymer grafting is usually considered as a chemical route to produce materials whose branches are chemically different from the backbone or primary polymer chain. The branches typically have the same chain size and are randomly distributed throughout the backbone’s length as a consequence of the synthetic route used synthesize them. However, more efficient methods that allow the synthesis of graft copolymers with equidistant and same-length branches, with which the microstructure and composition can be controlled to a remarkable level, have been developed [1]. From a surface-chemistry perspective, this definition of polymer grafting is extended to composites in which the main chain constitutes a diverse array of materials, ranging from brick and fiberglass to paper and wood [2]. Materials with improved or simply different polymer properties from mechanical, thermal, melt flow or dilute solution perspectives can be synthesized by polymer grafting [1,3,4,5,6,7]. The structure–properties relationship has been an important issue in the analysis of polymer grafting [1].

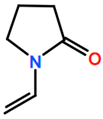

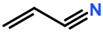

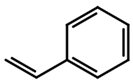

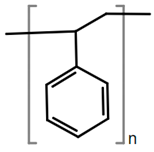

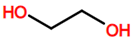

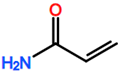

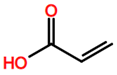

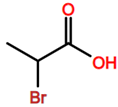

Some of the first reports on polymer grafting available in the open literature (e.g., the oldest records available through Web of Science) include the grafting of polystyrene (PSty) [8] and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) [9] onto “government rubber styrene” (GRS) [8], which is a synthetic copolymer of butadiene and styrene, or onto natural rubber [9]; grafting of PSty, poly(butyl methacrylate) (PBMA), poly(lauryl methacrylate) (PLMA), poly(methyl acrylate) (PMA), and poly(ethyl acrylate) (PEA) onto PMMA with pendant mercaptan groups [10]; grafting of polyacrylamide (PAM) onto polyacrylonitrile (PAN), or the other way around (PAN onto PAM) [11]; grafting of PMMA onto PAN [12]; grafting of PSty onto polyethylene (PE) [13]; and grafting of several polymers, such as PAN, PMMA, PSty, poly(acrylic acid) (PAA), and poly(vinylidene chloride) (PVDC), onto cellulose [14,15,16], to name a few. A more complete literature review on the chemistry of polymer grafting is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the synthesis and characterization of grafted copolymers with an emphasis on the period 1950 to 1970, plus some additional, more recent ones.

The renewed emphasis on the use of biobased monomers and biopolymers as a viable route to decrease (synthetic) polymer waste and disposal issues has invigorated the research efforts on the development of improved materials with important contents of biopolymers (frequently as backbones); grating is part of the synthetic procedure of such materials. These trends are in the scope of some recent review papers focused on polymer grafting, which include the grafting of polymers onto cellulose [27,28], chitin/chitosan [29,30], or polysaccharides in general [2,31].

The use of lignocellulosic waste as raw material for biorefining processes aimed at producing value-added chemicals or materials (e.g., bioethanol, cellulose, xylose, or hybrid materials, to name a few) has increased significantly since the start of the present century. Biorefineries from lignocellulosic waste require multistep processes, starting with pretreatment of the biomass. In this way, the constituent biopolymers are available for subsequent reactive processes [32,33,34,35]. The synthesis of value-added materials from lignocellulosic waste biomasses by using polymer grafting onto lignocellulose itself [36] or onto its individual components (cellulose [27], hemicellulose [37], or lignin [38]) represents an important route in the concept of biorefineries.

Although a few early studies focused on the mathematical descriptions of polymer grafting under specific circumstances—such as the calculation of grafting efficiency and molecular weight development of the grafted branches onto a pre-formed polymer containing pendant mercaptan groups capable of acting as effective chain transfer agents, based on a comprehensive kinetic model including chain transfer to polymer and bimolecular polymer radical termination [39], or the theoretical calculation of molecular weight distributions of vinyl polymers grafted onto solid polymeric substrates by irradiation, also based on a kinetic description of the growing of the grafted branches [40], and a few comprehensive recent models for other specific situations (e.g., the detailed description of free-radical polymerization (FRP)-induced branching in reactive extrusion of PE [41])—are indeed available, the fact is that the cases addressed by mathematical models are by far less common than the available experimental systems. The purpose of the present review is to first offer a rather detailed summary of what is known from a polymer chemistry angle about polymer grafting, with an emphasis on what backbones and grafts are used, how active sites on backbones are generated, and how polymer branches are grown or grafted, among other process details. The second objective is to review what polymer grafting situations have been modeled, which tools have been used, and what limitations persist. By doing that, we can show areas of opportunity. Do keep in mind that the system that motivated this study was the grafting of synthetic polymers onto lignocellulosic biopolymers.

2. Chemistry of Polymer Grafting

The main chemical routes for polymer grafting are the following: “grafting onto” (also referred as “grafting to”), “grafting from,” and the macromonomer or macromer (or “grafting through”) method [1,2,27,28]. There are general reviews focused on the synthesis of grafted copolymers [1,2]. The ranges of backbones and grafts, backbone activating methods, graft growing (polymerization) routes, characterization techniques, quantification methods of grafting and branching molar mass distributions, and applications are so vast that reviews on specific aspects or subtopics related to these issues have been written. For instance, there are reviews focused on the grafting of polymer branches onto natural polymers [42] and biofibers [43]; grafting onto cellulose [27] or cellulose nanocrystals [28]; grafting onto chitin/chitosan [29,30]; microwave-activated grafting [31,44]; laccase-mediated grafting onto biopolymers and synthetic polymers [2]; radiation-induced RAFT-mediated graft copolymerization [45]; and polymer grafting onto inorganic nanoparticles [46] to name a few.

Herein, brief descriptions of such chemical routes are provided. In Table 1 we provide an overview of the grafted copolymer materials synthesized in the 1950–1970 period, plus some additional more recent cases, considering backbone structure, functionalization or active site generation techniques or procedures, grafted arm structure, polymer grafting technique, polymer grafting conditions, measured properties and characterization methods, and related references. The literature on polymer grafting onto cellulose, chitin/chitosan, lignocellulosic biopolymers, other polysaccharides and natural biopolymers, inorganic materials, and metallic surfaces is addressed in the subsequent sections of this review.

2.1. Types of Polymer Grafting

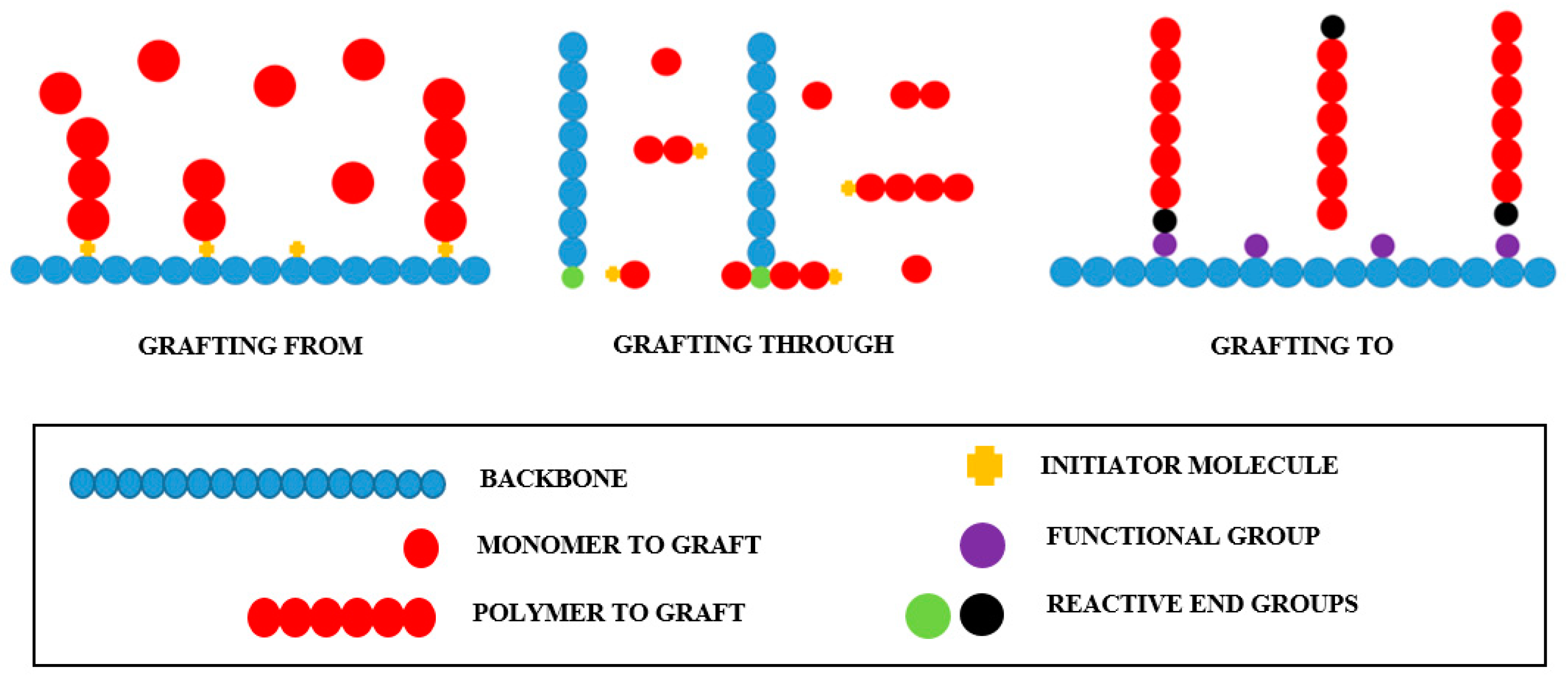

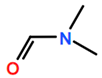

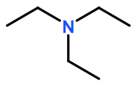

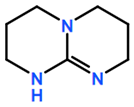

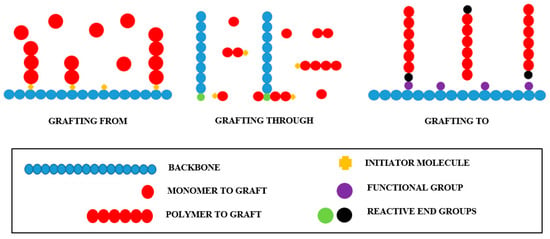

As stated earlier, polymer grafting can proceed by the “grafting to” technique, where a polymer molecule with a reactive end group reacts with the functional groups present in the backbone; by “grafting from,” where polymer chains are formed from initiating sites within the backbone; and by “grafting through,” where a macromolecule with a reactive end group copolymerizes with a second monomer of low molecular weight. Simplified representations of these grafting techniques are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Polymer grafting chemical routes.

“Grafting to” and “grafting from” are the most common polymer grafting chemical routes. Better defined graft segments are obtained by the “grafting to” technique since the polymerization is independent of the union between the backbone and grafts. In contrast, materials of higher grafting densities can be produced by the “grafting from” route due to the lack of steric hindrance restrictions [47].

However, each polymer grafting route has its own advantages and disadvantages in terms of chemical nature, density, dispersity, and length of the grafts obtained, and the ease and efficiency of the chemical reactions involved. Interestingly, different polymer grafting routes can be combined to produce specific grafted materials [48].

2.2. Main Backbones Used in Polymer Grafting

A polymer backbone is a polymer molecule that supports polymeric side chains, called branches or grafts. Side chains can be inserted onto the backbone during the synthesis of the backbone (copolymerization situation) or as a post-production process of the backbone [49]. In the first case, polymers with homogeneous bulk properties are obtained. The second case is very attractive since it allows the modification of many polymeric materials, including natural and synthetic fibers, or inorganic and metal particles. Backbones processed by polymer modification do not usually show significant changes in bulk properties. Surface modification is often carried out following a “grafting from” technique; that is why this method is also known as surface initiated polymerization (SIP) [50]. The backbones used for polymer grafting can be synthetic polymers, biopolymers, or inorganic and metal surfaces.

Synthetic polymers are human-made polymers and include a wide variety of materials, such as polyolefins, vinyl and fluorinated polymers, nylons, etc. The applications of synthetic graft copolymers include the synthesis of antifouling membranes [51], stimuli-response materials [52], and biomedical applications [53].

Biopolymers are produced by the cells of living organisms. Polysaccharides have become important lately because of their characteristics of availability, biocompatibility, low cost, and non-toxicity, making them candidates for substitution of petroleum-based materials [47]. Polysaccharide-based graft copolymers are used as drug delivery carrier, food packaging and wastewater treatment [54]. Some of the most studied polysaccharides are cellulose [27,28], lignin [55], chitin/chitosan [29,56,57,58], starch [59], and various gums [42].

Surface functionalization of inorganic and metallic particles that allow the incorporation of polymer shells by polymer grafting has also become important, since polymer coatings alter the interfacial properties of the modified particles. Zhou et al. reviewed different applications for inorganic and metallic particles grafted with biopolymers [50]. One important inorganic surface modified by polymer grafting is silica [60].

2.3. Backbone Functionalization Methods

Several chemical modification procedures have been developed due to the wide variety of backbones of interest. Chemical modification reactions depend on the functional groups (or absence thereof) along the backbone. Two main chemical routes used to attach, grow, or graft polymer molecules onto lignin have been proposed [55]: (a) creation of new chemically active sites, and (b) functionalization of hydroxyl groups.

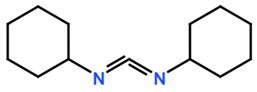

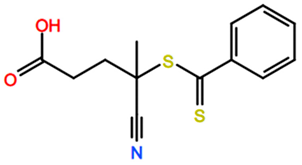

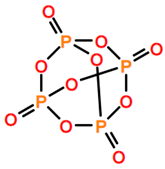

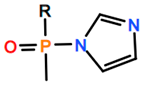

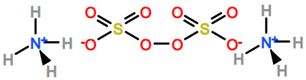

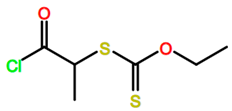

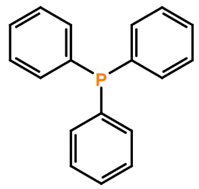

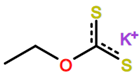

The introduction of functional groups into a polymer backbone increases its reactivity, making it accessible for forward polymerization or coupling reactions. Functionalization reactions are therefore required to generate the end functional pre-formed polymer or the reactive end of the macromolecule species involved in the “grafting to” and “grafting through” polymer grafting techniques, respectively. Functionalization is also required in the formation of the macromolecular species, such as macro-initiators and macro-controllers, involved in the “grafting from” polymer grafting technique [27,61]. The most important functionalization reactions involved in polymer grafting include sulfonation, esterification, etherification, amination, phosphorylation, and thiocarbonation, among others.

2.4. Backbone Activation Methods

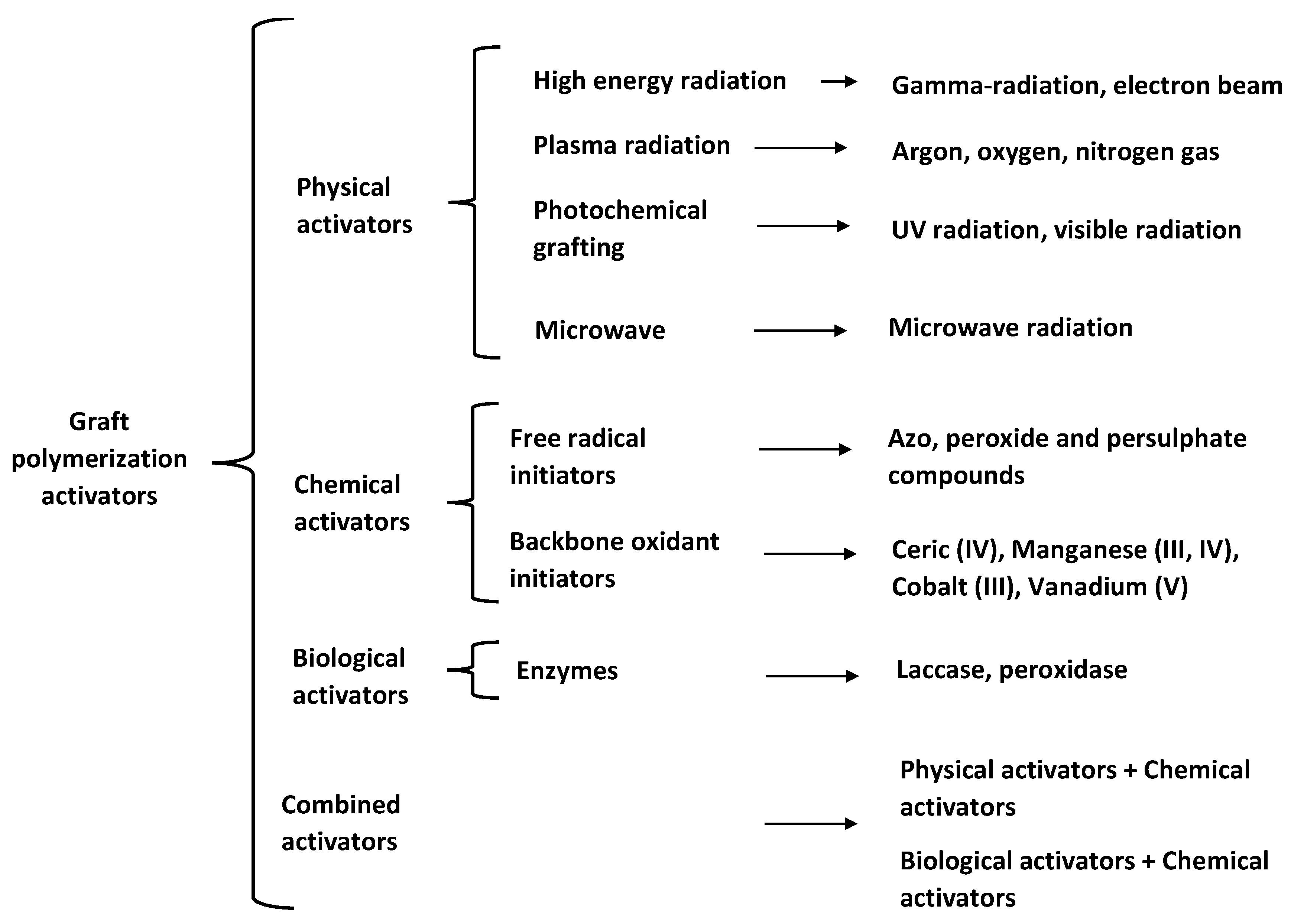

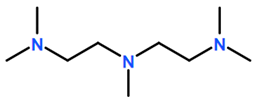

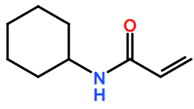

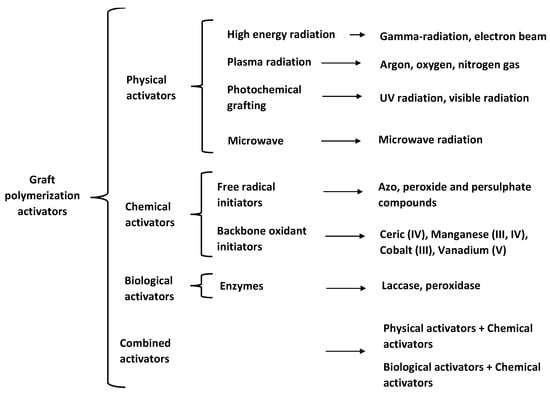

Another way to generate grafting sites within the polymer backbone is to use polymer grafting activators, such as free-radical initiators. As shown in Figure 2, polymer grafting activators can be classified into physical, chemical, and biological. The main characteristics of these activators are highlighted in Section 2.4.1, Section 2.4.2, Section 2.4.3 and Section 2.4.4.

Figure 2.

Backbone activators used for polymer grafting.

2.4.1. Physical Activators

High energy radiation, also referred to as ionizing radiation, includes γ-beam and electron-beam radiations. Radiation-promoted grafting may follow one of three possible routes: (a) pre-irradiation of the backbone in the presence of an inert gas to generate free radicals before placing the backbone in contact with monomers; (b) pre-irradiation of the backbone in an environment containing air or oxygen to produce hydroperoxides or diperoxides in its surface, followed by high temperature reaction with monomer; and (c) the mutual irradiation technique, where backbone and monomer are irradiated simultaneously to generate free radicals [62].

Plasma is a partially ionized gas where free electrons, ions, and radicals are mixed. Different functional groups can be introduced, or free radicals can be generated on backbones by this process, depending on the gas used. Polymer grafting reactions carried out in plasma are sometimes classified as high energy radiation reactions [63].

The absorption of UV light on the surface of the material generates free radicals that serve as nucleation sites. The surface is then placed in contact with monomer for subsequent polymerization [64].

Microwave irradiation consists of direct interaction of electromagnetic irradiation with polar molecules and ionic particles, promoting very fast non-contact internal heating, which enhances reaction rates and leads to higher yields. Singh et al. carried out a successful polymerization of acrylamide on guar gum under microwave irradiation [65]. They proposed a mechanism in which free radicals are produced within the polysaccharide backbone by the effect of microwave irradiation on the hydroxyl groups of the biopolymer [65].

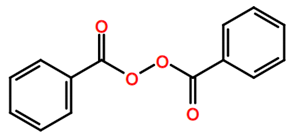

2.4.2. Chemical Activators

As shown in Figure 1, chemical activators include free radical and backbone oxidant initiators. Free radical initiators are compounds that present either direct or indirect homolytic fission. The first case involves the initiator itself and the second one requires participation of another molecule from the environment [66].

Oxidant initiators react directly with functional groups from the backbone, generating activation sites. Polymer grafting of polysaccharides using oxidant initiators has been reported in the literature [66].

2.4.3. Biological Activators

Enzymes catalyze polymer modification reactions through functional groups located at chain ends, along the main chain, or at side branches, promoting highly specific non-destructive transformations on backbones, under mild reaction conditions. Successful grafting of lignin by oxidation of its phenolic structures using laccases has been reported recently [2].

2.4.4. Combined Activators

Combinations of physical and chemical activators for polymer grafting have been successfully carried out. For instance, microwave assisted polymerization (MAP) has been combined with the use of chemical activators for the production of hydrogels synthesized by crosslinking graft copolymerization, taking advantage of the short reaction times required to obtain high yields [67,68]. Enzymes are also used in combination with radical initiators for more effective grafting copolymerization processes [69,70].

2.5. Polymer Grafting by Free-Radical Polymerization

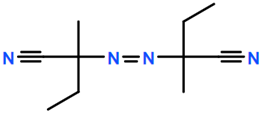

As stated earlier, the “grafting through” and “grafting from” techniques require a polymerization reaction to bond the polymer grafts to the backbone. Different polymerization methods have been used for polymer grafting, but the most effective ones use free radical methods (e.g., FRP, RDRP, and REX), due to their versatility to work with different chemical groups, and their tolerance to impurities. A short overview on free-radical polymerization reactions is presented in Table 2. Polymer grafting by FRP, and other reactions, is affected by several factors, including the chemical nature of the components contained in the system—backbone, monomer, initiator, and solvent—and the interactions among them. Other aspects related to polymer grafting, including temperature and the use of additives, need to be considered [67]. The synthetic routes and activators used in graft polymerization provide a variety of interesting and versatile routes for this type of polymer modification.

Table 2.

Free-radical polymerization methods.

3. Backbones and Supports Used in Polymer Grafting

As explained earlier, grafted materials consist of side chains or arms attached to primary polymers referred to as backbones. The purpose of polymer grafting is to combine chemical, mechanical, interfacial, electrical, or other polymer properties between the constituent materials. The diversity of backbones and the ways in which side chains are attached to them through polymer grafting will be briefly overviewed in this section.

3.1. Cellulose, Lignin, and Lignocellulosic Biomasses as Backbones

Lignocellulosic biopolymers are abundant in nature. They are made of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. They also contain moisture, extractive organic compounds, and ashes from inorganic compounds in lesser amounts. Each of these components has distinct characteristics. The extractive organic compounds present in lignocellulosic biopolymers are oligomers and oligosaccharides of low molecular weight, sugars, fatty acids, resins, etc. [76].

Cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin can be modified by polymer grafting leading to new promising materials with interesting properties. However, the extractables are not useful for this purpose since they are not part of a skeleton or stiff structure that may provide support or mechanical stability. Extractables also consume reactants required for the grafting process. They are usually removed prior to the polymer grafting process, although in some studies, they remain in the system during the formation of grafted arms [77].

Polymer grafting of xylan onto lignin has been studied since the early 1960s. Early reports on the topic reported the grafting of organic polymers, such as 4-methyl-2-oxy-3-oxopent-4-ene and methyl methacrylate polymers [78,79], xylan [80], ethylbenzene, and styrene [81,82,83,84], onto lignin or lignin derivatives. The topic of polymer grafting of synthetic polymers onto lignocellulosic biopolymers has gained renewed relevance in the last two decades due to environmental and sustainability issues [27,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94].

Cellulose can be extracted from lignocellulose and used as such or modified for other applications. Table 3 provides an overview of grafting of synthetic polymers onto cellulose and natural fibers. (See the tables of Section 6 for explanation of abbreviations and symbols.)

Table 3.

Overview of grafting of synthetic polymers onto cellulose and natural fibers.

Lignin follows cellulose in abundance on earth, providing a primary natural source of aromatic compounds [125]. Several industrial applications have been attempted for lignin [55,125,126,127] but not all of them have succeeded due to different reasons [125,128,129,130].

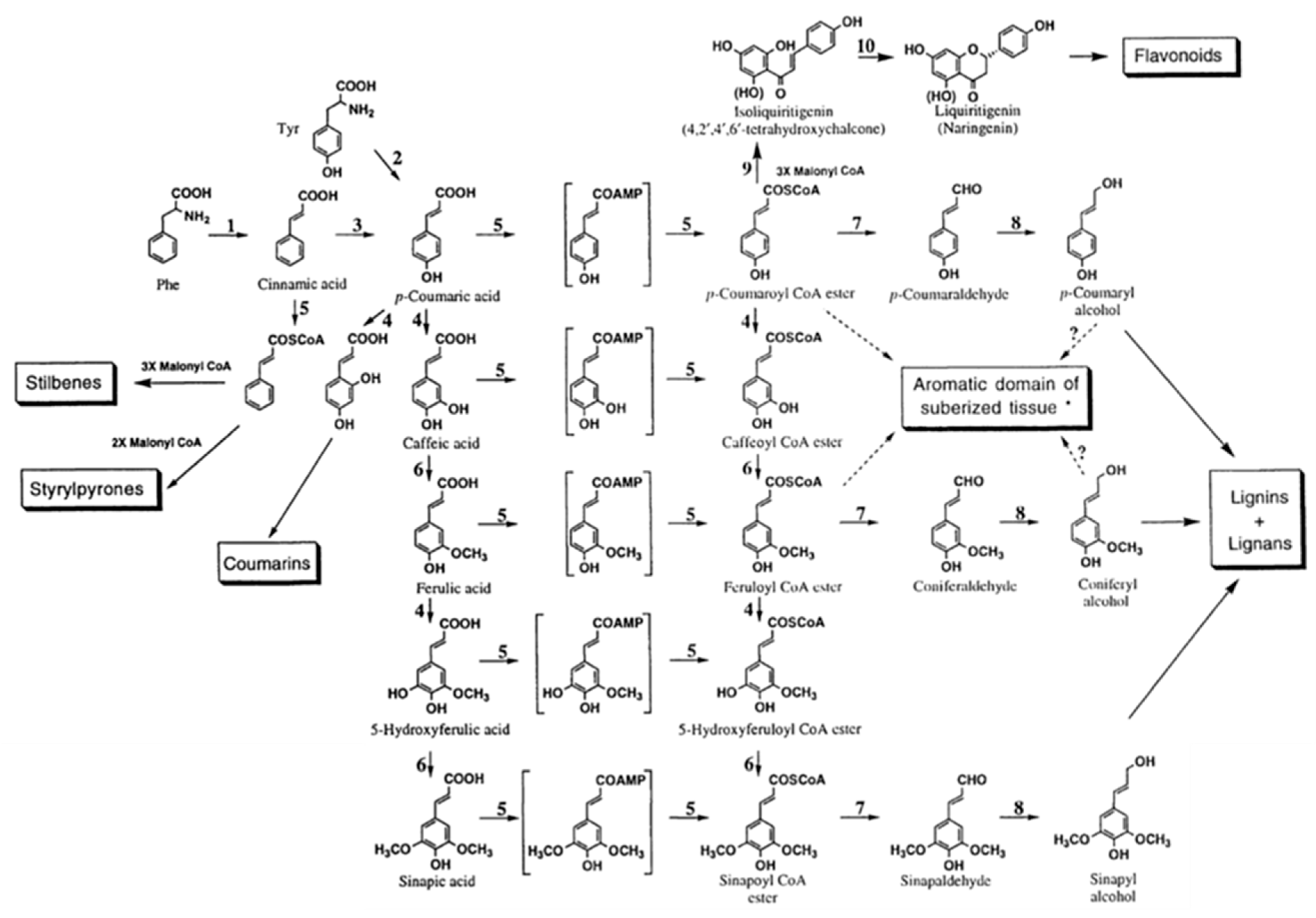

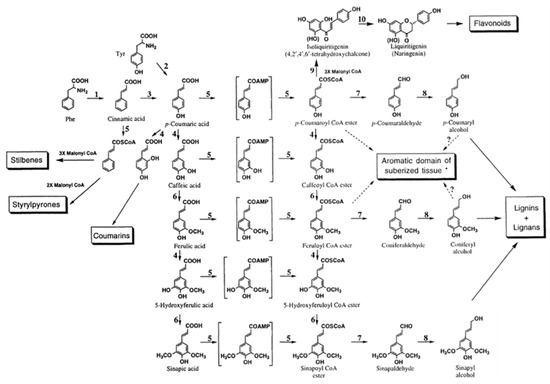

Marton [8] described fifty-four different constituents that can be found in lignin based on interpretation of experimental data from biochemical degradation, oxidation, and other ways of decomposition of different types of lignin materials. The combinations and proportions among these structures lead to different properties of lignin materials. Three decades later, Lewis and Sarkanen [130] organized these fifty-four structures into a map that they called phenylpropanoid pathway. As observed in Figure 3, lignins and lignans are monolignol derived compounds. Sharma and Kumar described lignin as a complex material consisting mostly of three single unit lignol precursors, coniferyl alcohol, p-coumaryl alcohol, and sinapyl alcohol, along with other atypical monolignol constitutive units in trace amounts [55].

Figure 3.

Main steps of the phenylpropanoid pathway: lignins and lignans are monolignol derived. 1, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase; 2, tyrosine ammonia-lyase (mostly in grasses); 3, cinnamate-4-hydroxylase; 4, hydroxylases; 5, CoA ligases involving AMP and CoA ligation, respectively; 6, O-methyltransferases; 7, cinnamoyl-CoA:NADP oxidoreductases; 8, cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenases; 9, chalcone synthase; 10, chalcone isomerase. (Note: conversions from 7-coumaric acid to sinapic acid and corresponding CoA esters are marked in boxes since dual pathways seem to take place; *: may also involve 7-coumaryl and feruloyl tyramines, and small amounts of single unit lignols). Source: Adapted with permission from Lewis N. G. and Sarkanen S. (1998). Lignin and Lignan Biosynthesis, Washington, D.C.: Oxford University Press pp. 6–7 [130] Copyright © 2021 by American Chemical Society.

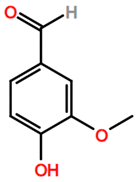

The process used for lignin extraction and the final properties of the material depend on the type of biomass employed [55]. Lignin is obtained from woods, which can be hard, soft, bushes, rinds, husks, corncobs, either products or residues. A pulp is obtained from these materials. The yield of lignin extraction depends on temperature, time, dispersion media, extraction method, and the amount of lignin present in the raw material. Lignin extraction methods can be biological or enzymatic, physical, or chemical. Integrated solutions are employed at the end to remove impurities from lignin so it can be bleached [55]. The complex structure of lignin contains specific surface moieties that provide reactive sites where polymers and other species can be synthesized, bonded, or modified [55]. These moieties were recognized as hydroxyl, carboxyl, carbonyl, and methoxyl groups.

There are two main routes for grafting of polymer chains onto lignin-based biopolymers [55]: (a) synthesis of new reactive sites within lignin’s structure; and (b) modification or functionalization of lignin’s hydroxyl groups. Route (a) allows lignin to become more reactive, both at the surface, and within the bulk. Polymer modification by route (a) improves both, the properties of lignin and those of the modified materials.

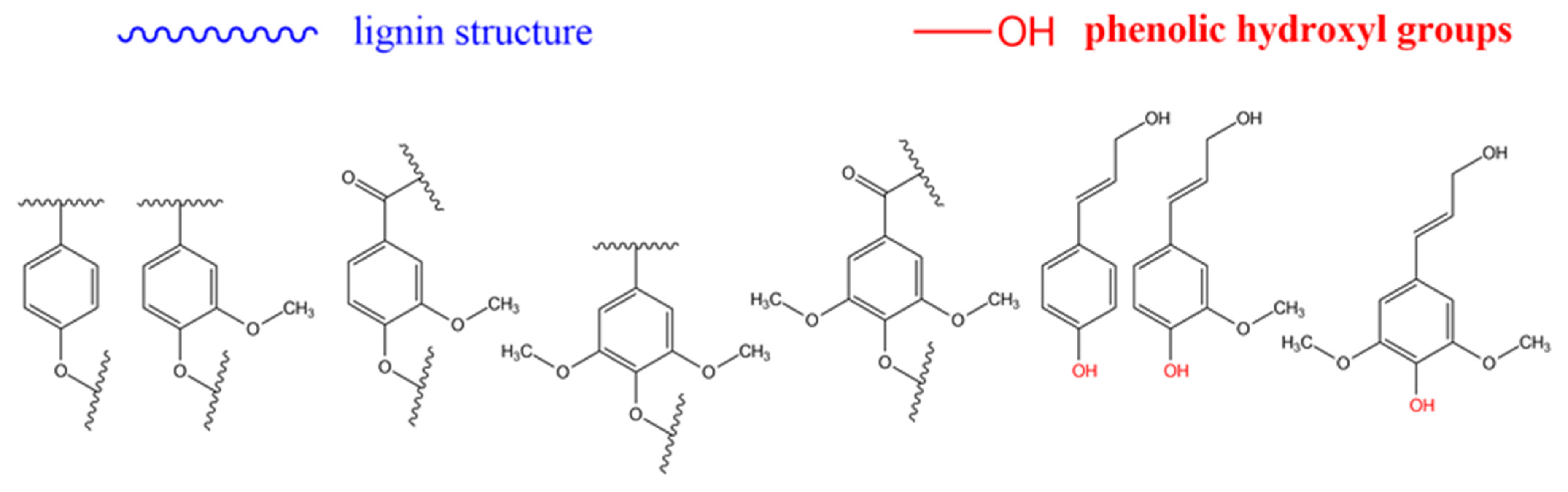

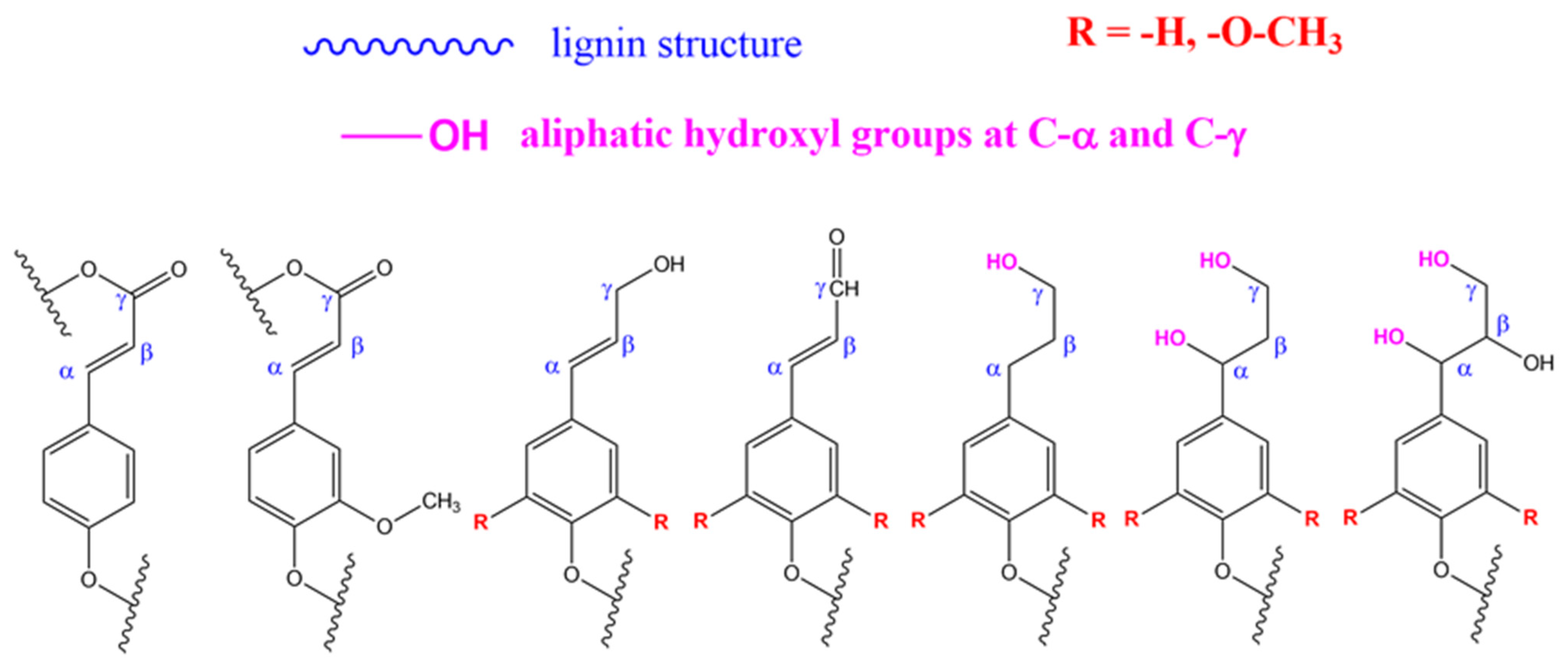

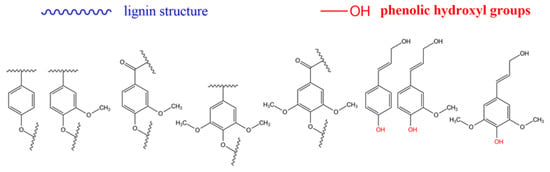

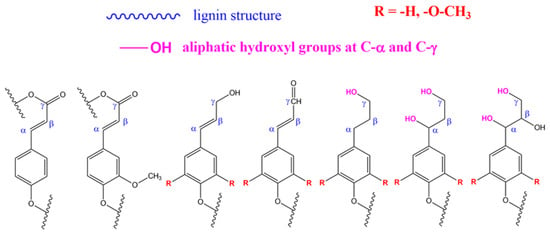

In route (b), a good number of functional groups can be placed in the end groups of lignin (what is sometimes referred to as the surface of lignin). Katahira et al. [131] identified seven side chain structures in the end groups of lignin: p-coumarate, ferulate, hydroxycinnamyl alcohol, hydroxycinnamaldehyde, arylglycerol, dihydrocinnamyl alcohol, and guaiacylpropane-1,3-diol end-units, as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5 [131]. However, it has been proposed that the phenolic hydroxyl groups shown in Figure 4, and the aliphatic hydroxyl functional groups corresponding to C-α and C-γ positions of the side molecule fragment shown in Figure 5, are the most reactive [55]. Both routes allow one to produce grafted materials, mainly polymers, and most of them come from route (b) above [85,132,133]. Further reports on lignin treatments and grafting can be found elsewhere [55,91,125,128].

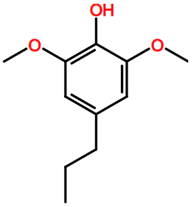

Figure 4.

Repeating units in lignin. From left to right: p-hydroxyphenyl, guaiacyl, metoxy guaiacyl, syringyl, metoxi syringyl, p-coumaryl alcohol, coniferyl alcohol, synapyl alcohol. Source: Adapted with permission from Katahira et al. (2018). Lignin Valorization. Emerging Approaches: Croydon UK pp. 3 [131]. Copyright © 2021 The Royal Society of Chemistry.

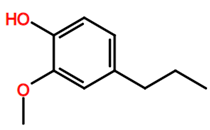

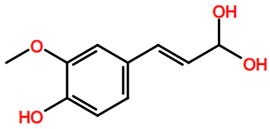

Figure 5.

Side chain structure in end-groups in lignin. From left to right: p-coumarate, ferulate, hydroxycinnamyl alcohol, hydroxycinnamaldehyde, dihydroycinnamyl alcohol, arylpropane-1,3-diol, arylglycerol end units. Source: Adapted with permission from Katahira et al. (2018). Lignin Valorization. Emerging Approaches: Croydon UK pp. 5 [131] Copyright © 2021 The Royal Society of Chemistry.

The overview on grafting of synthetic polymers onto cellulose and other lignocellulosic biopolymers presented in Table 3 is further expanded in Table 4 to include other examples of lignocellulosic biomasses, and other natural biopolymers, such as polysaccharides, chitin, and chitosan. Examples of recent research reports (2020–2021) on synthesis of grafted polymers are provided in Table 5. Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10, Table 11, Table 12 and Table 13 contain extensive information related to characterization of polymer grafting. Table 14 summarizes the literature on modeling of polymer grafting. Table 15 shows the polymerization scheme of FRP including CTP and crosslinking. Finally, Table 16, Table 17, Table 18 and Table 19 provide information on the many symbols and abbreviations used throughout the review.

Table 4.

Overview of grafting of synthetic polymers onto natural polymers: lignin, hemicellulose, polysaccharides, chitosan, and chitin backbones.

Table 5.

Recent reports on the production of materials using polymer grafting (2020–2021).

Table 6.

Common characterization methods.

Table 7.

Summary of thermal characterization techniques employed in grafted materials.

Table 8.

Summary of spectroscopic characterization techniques employed in grafted materials.

Table 9.

Summary of digital imaging and microscopy characterization techniques employed in grafted materials.

Table 10.

Summary of rheological characterization techniques used for grafted materials.

Table 11.

Summary of chromatographic characterization techniques used for grafted materials.

Table 12.

Summary of characterization techniques based on mechanical properties used for grafted materials.

Table 13.

Summary of biological, functional, and compositional characterization techniques employed in grafted materials.

Table 14.

Overview of studies focused on the modeling of polymer grafting.

Table 15.

Polymerization scheme for free-radical polymerization including CTP and crosslinking.

Table 16.

Symbols of application fields.

Table 17.

Abbreviations used for characterization techniques.

Table 18.

Abbreviations of properties and variables measured by characterization techniques.

Table 19.

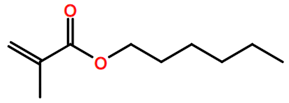

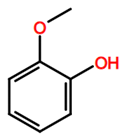

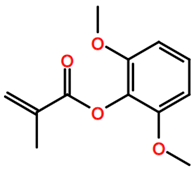

Abbreviations and formulae of some chemical compounds and materials used.

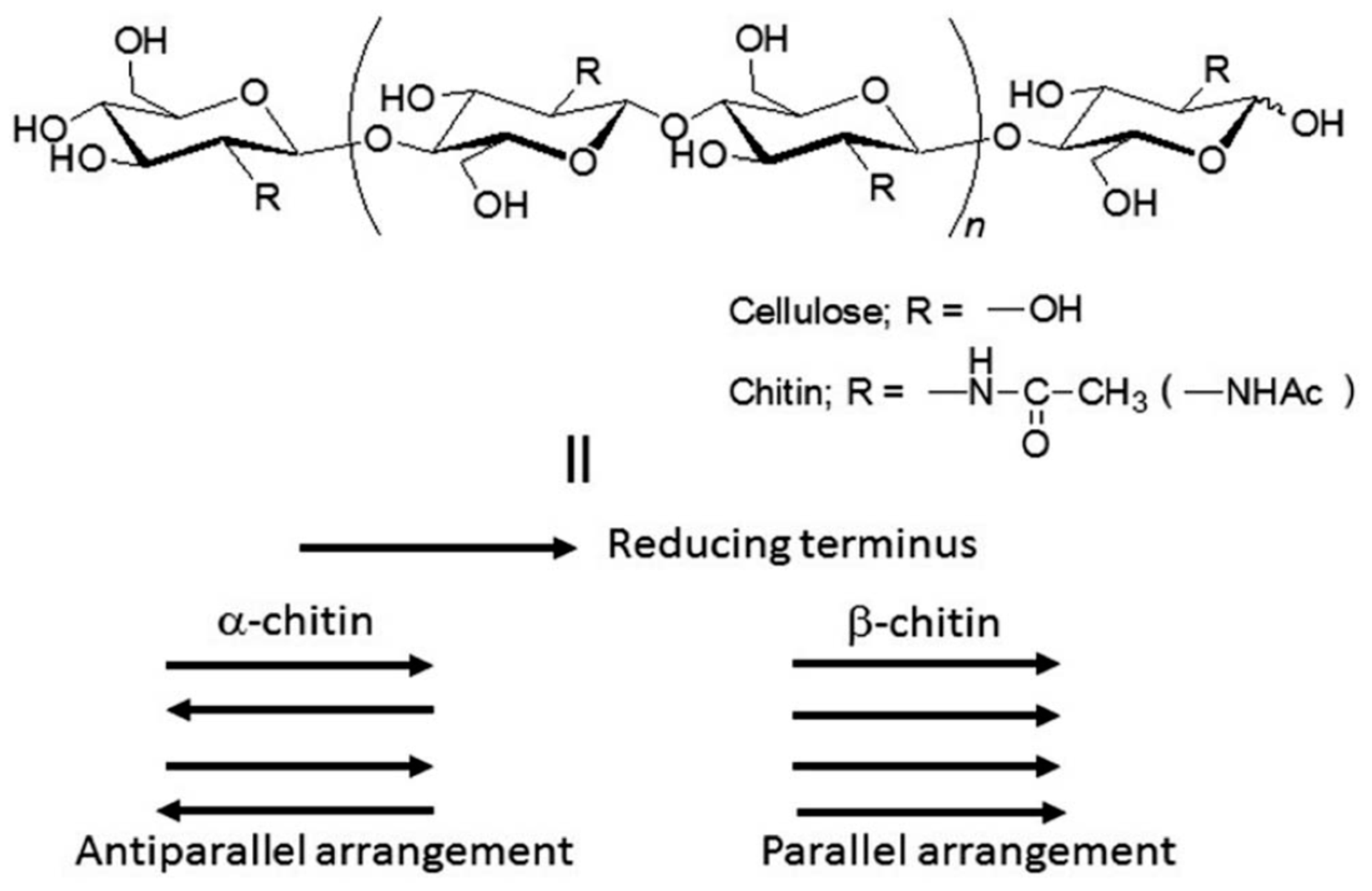

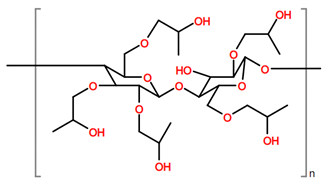

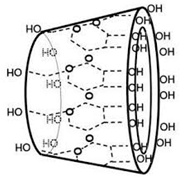

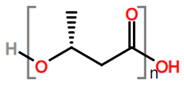

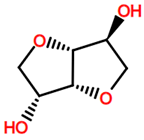

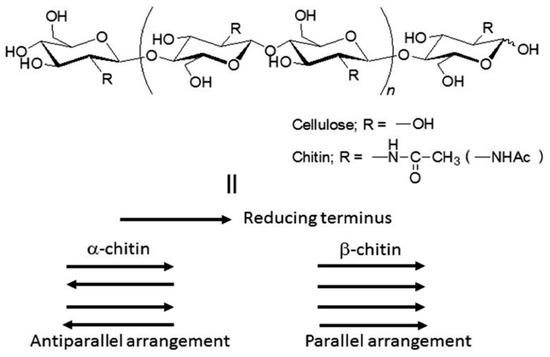

Polysaccharides are abundant in nature, no matter whether in plants or animals, and are important for in vivo functions. As observed in Figure 6, there is a wide variety of polysaccharides, but the most abundant ones are cellulose and chitin. Cellulose provides structure to the cell walls of plants. Chitin, on the other side, is part of the exoskeletons of crustaceans, shellfish, and insects [169].

Figure 6.

Cellulose and chitin structures (top). II: schematic diagram of crystalline structures for different forms of chitin. Source: Adapted with permission from Jun-ichi Kadokawa (2015). Fabrication of nanostructured and microstructured chitin materials through gelation with suitable dispersion media: RSC Adv. 5 12736 [169]. Copyright © 2021 The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Chitin is an abundant but only marginally used biomass. There are several reasons why not many practical applications for chitin have been developed [169]: (a) bulky structure; (b) insolubility in water and typical organic solvents; (c) it is harmful to recover chitin, since the available procedures require the use of strong acids and bases; (d) native chitin from crustaceans, which have exoskeletons that protect animals from their predators, has fibrous structures rich in proteins and minerals; and (e) there is a need to remove mineral and protein constituents in order to isolate chitin.

Chitosan was developed to overcome the drawbacks of chitin. Chitosan is commercially attractive for production of biocompatible polymers for environmental and biomedical applications [30]. It is basically a copolymer of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine and D-glucosamine. It is obtained from the hydration of chitin. This hydration takes place in alkaline solutions in a temperature range of 80–140 °C during 10 h [170,171].

Chitosan is a cationic polysaccharide, produced by deacetylation of chitin. Deacetylation proceeds to different levels depending on the intended uses. The physical properties of chitosan, particularly solubility, depend on molecular weight and degree of deacetylation of the material [172,173,174].

Modification of chitosan leads to a diversity of derivates, with differentiated properties. As shown in Figure 1 of Deng et al. [174], different chitosan moieties are possible. Each one of them is produced from grafting or other chemical or enzymatic modification forms. They differ in antimicrobial activity. Further studies on chitin-chitosan modification are available in the literature [58,175,176,177,178].

3.2. Polymer Backbones

Polymer backbones are the most common substrates for grafting modification. Several techniques can be used to create many possible combinations. Most of these developments are focused on property improvement for industrial applications. They include synthesis of adhesives; reinforcement of mechanical properties; improvement of chemical resistance; synthesis of electro, optical, thermo responsive polymers; health care applications; and self-healing polymers, among others [179].

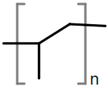

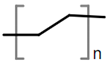

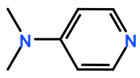

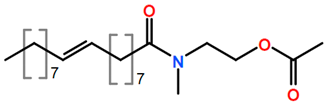

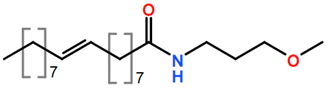

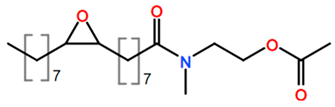

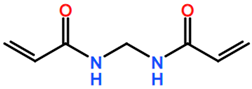

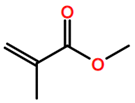

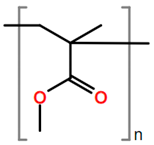

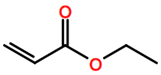

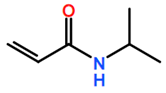

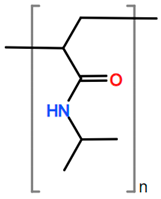

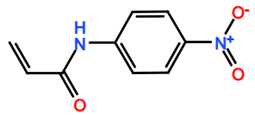

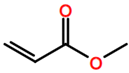

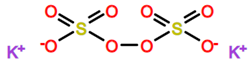

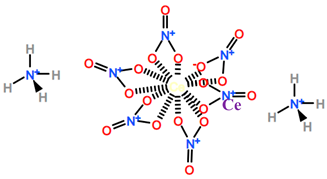

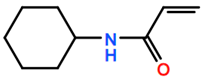

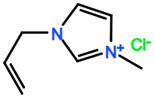

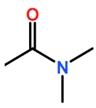

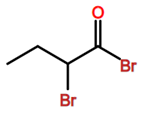

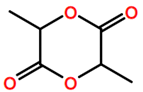

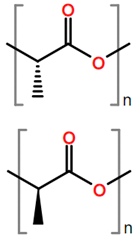

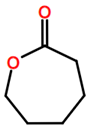

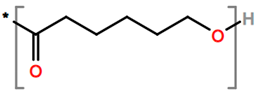

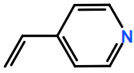

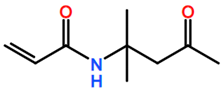

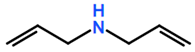

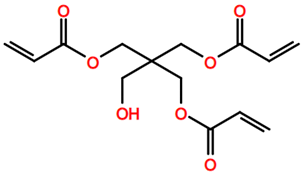

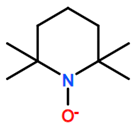

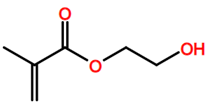

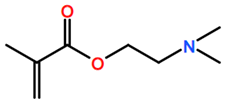

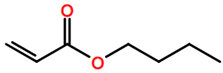

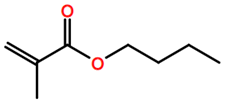

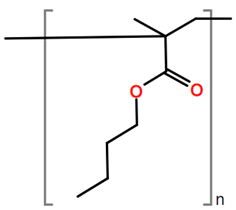

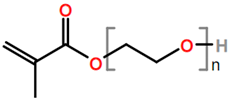

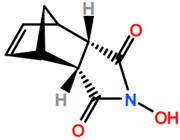

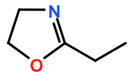

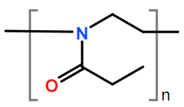

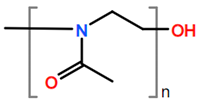

Polymer grafting techniques have been reported since the late 1950s [8,9,11]. Polymers based on acrylamide and acrylonitrile using polymer grafting techniques are included in the early reports. However, the huge increase in research related to synthesis of materials with controlled microstructures using polymer grafting techniques has been possible due to the advances in reversible deactivation radical polymerization (RDRP) techniques over the last three decades [180,181,182,183,184]. The main RDRP routes are nitroxide mediated polymerization (NMP) [185], reversible addition fragmentation transfer polymerization (RAFT) [180,186,187], and atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) [71,188], although there are other polymer synthesis techniques, such as ring-opening polymerization (ROP) [181] and click chemistry, among others, that can be used. Another important aspect in polymer grafting is the solvent used for the reaction, particularly when grafting proceeds as a heterogenous process. As observed in Table 19, solvents such as supercritical fluids, mainly supercritical carbon dioxide, water, DMF, or combinations of solvents are typically used for polymer grafting. These techniques have improved our skills to produce molecularly well-defined, chain-end tethered polymer brush films. The assets of RDRP have substantially impacted the synthesis and properties of surface-grafted polymers. Although vinyl monomers are widely use in graft polymerization for backbones or side-arms, other monomers coming from natural sources are increasingly being used. That is the case, for instance, of ɛ-caprolactone, lactic acid [189], L-lactide, and butyrolactone. It is also observed in Table 19 that other nontraditional monomers such as acrylamide (AM), N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAAM), and acrylates and methyl acrylates, such as methyl methacrylate (MMA) and acrylic acid (AA), are being increasingly used in polymer grafting applications.

To get a glimpse of the focus of research papers that involve polymer grafting as the chemical route for polymer modification, Table 5 summarizes journal reports on polymer grafting from the current period (2020–2021). As expected, an increasing trend toward the improvement of natural biopolymers using synthetic polymer arms is observable.

4. Characterization Techniques Used for Polymer Grafted Materials

The characterization of polymer grafted materials requires the use of a variety of methods due to the many possible combinations of backbones and polymer grafts [59]. The characterization methods can be classified as direct or indirect.

Direct methods are those used to identify changes in the chemical structure of grafted materials, such as the bonds between backbone and grafts. These methods include proton and carbon magnetic nuclear resonance, 1H-NMR, and 13C-NMR, respectively.

Indirect methods are based on differences in properties between the starting and grafted materials, relating these changes to the modified structures. Microscopy and thermal analysis are examples of indirect methods. A summary of the main characterization methods used for grafted materials is presented in Table 6.

The relevant information contained in selected articles is also gathered in this review to show how the characterization techniques were used to provide evidence of polymer grafting onto the corresponding backbones. Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10, Table 11 and Table 12 summarize the use of thermal, spectroscopic, imaging and microscopy, rheological, chromatographical, and mechanical characterization techniques, respectively, in the analysis of polymer grafted materials. Finally, a summary of biological, functional, and composition characterization techniques used for grafted materials is provided in Table 13.

5. Modeling of Polymer Grafting

5.1. Literature review on Modeling of Polymer Grafting

An overview of the literature on the modeling of polymer grafting is summarized in Table 14. The backbones considered, the functionalization methods, the polymer chains grafted, and summary comments on the modeling approaches used to carry out the simulations are included in the table.

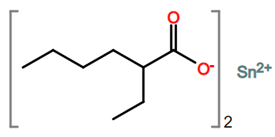

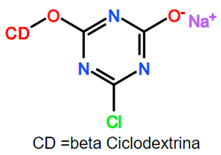

5.2. Modeling of Polymer Branching and Crosslinking

As observed in Table 14, most reports on the modeling of polymer grafting are related to cases where grafting involves free-radical growth of the grafts, and the generation of active sites proceeds through chain transfer to polymer reactions. In that sense, the growth of polymer grafts resembles the formation and growth of branches in polymer branching. The difference would be that the branches and primary polymer chains contain the same monomers, whereas grafts and backbones contain different monomers in polymer grafting. There are several papers focused on the modeling of polymer branching [262,263,264,265,266,267,268]. In some cases, as in the grafting of monochlorotriazinyl-β-cyclodextrin onto cellulose, the activation mechanism is not specified, and the modeling approach is fully empirical (neural network modeling) [237,238,239].

In general terms, the polymerization scheme of FRP including chain transfer to polymer (CTP) is given by the reactions shown in Table 15. The specific mathematical expressions containing CTP terms are given by Equations (1)–(7). I, R, and M in Table 15 are initiator, primary free radical, and monomer molecules, respectively; Pn and Dm denote live and dead polymer molecules, respectively, of sizes n and m. ki, kp, ktd, and ktrp (also denoted as kfp in Equations (8) and (9)) denote initiation, propagation, termination by disproportionation, and chain transfer to polymer kinetic rate constants, respectively.

Polymer branching can be modeled using a bivariate distribution of chain length and number of branches resulting from polymerizations involving branched polymers [269]. Pn, b in Table 15 accounts for a bivariate distribution of live polymer of length n and number of branches b. The moment equations shown below consider only the kinetic steps of propagation and chain transfer to polymer, for illustrative purposes. For a batch reactor, the application of the mass action law considering only these two kinetic steps results in Equation (1) [269]. It should be noticed that in the transfer to polymer reaction there are as many possible sites of reaction as monomeric units in the dead polymer chain participating in the reaction.

n = 1, …, ∞; b = 0, …, ∞

The bivariate moments for active and inactive polymer are defined respectively as shown in Equations (2) and (3). Number and weight-averaged molecular weights, and the average number of branches, are given by Equations (4)–(6) [269].

The moment equations for live polymer are given by Equation (7) [269].

Another approach with which to address the modeling of polymer branching in FRP is to use the concept of branching density, denoted as ρ, which is given by the ratio of the number of branching points to that of monomeric units, and it can be estimated using Equation (8), which when solved leads to Equation (9) [270]. kfp and kp in Equations (8) and (9) are chain transfer to polymer and propagation kinetic rate constants, respectively, and x is monomer conversion.

CTP and terminal double bond (TDB) polymerization produce tri-functional (long) branches, in addition to increasing the weight-averaged molecular weight and broadening the MWD. A reaction “similar” to TDB polymerization is the polymerization with internal (pendant) double bonds (double bonds “internal” in dead polymer chains, appearing therein due to (co)polymerization of di-functional (divinyl) monomers (e.g., butadiene). Internal double bond (IDB) polymerization produces tetra-functional (long) branches and leads eventually to the formation of crosslinked polymer (gel). Both molecular weight averages increase due to IDB polymerization and the MWD broadens considerably [43]. Crosslinking can be considered as interconnected branching, and in that sense, its growth by CTP and its modeling in terms of a crosslink density, denoted as ρa, can also be taken as a useful basis for the modeling of polymer grating by CTP and propagation through the intermediate free radicals. Balance equations for polymer radicals of size r (R*r) and ρa for a case of copolymerization with crosslinking of vinyl/divinyl monomers, using the pseudo-kinetic rate constants method, are given by Equations (10) and (11), respectively, where Ps is a dead polymer of size r; Q1 is first-order moment for the dead polymer; and kcp and kcs are primary and secondary cyclization rate constants, respectively [271].

5.3. Main Modeling Equations for Polymer Grafting

Grafting efficiency (ε) and number average molecular weights for the different polymer populations (WIH, WSH, WII, WIS, and WSS) for the grafting of vinyl polymers onto pre-formed polymer with highly active chain transfer sites of (pendant mercaptan groups) are given by Equations (12)–(17) [39]. Subscripts IH and SH in the molecular weights shown in Equations (12)–(17) account for primary chains formed by chain transfer or by disproportionation termination (without distinguishing between terminally saturated and unsaturated chains) of polymer radicals starting with I and S fragments, respectively. Subscripts II, IS, and SS, on the other hand, account for primary chains produced by combination of the appropriate pair of polymer radicals starting with I and S fragments, respectively. r in Equations (12)–(18) is the ratio of propagation to termination kinetic rate constants, namely, r = kp/2kt.

An example of calculation of the mole fraction chain length distribution (number distribution) (nx) for the case of polymer grafting of vinyl polymers onto solid polymeric substrates, considering no chain transfer and incomplete conversion, is shown in Equation (18) [40].

When addressing the modeling of polymer grafting of vinyl polymer onto polyolefins in extruders by CTP, Hamielec et al. [231] proposed a polymerization scheme and the corresponding kinetic equations where the prepolymer molecule bears abstractable hydrogens on its backbone and a second compound, denoted as additive (A), is bound to the prepolymer backbone via reaction with a free radical. The backbone radical then transfers its radical center to the active molecules. The radical is finally terminated with other radicals. Proper kinetic equations were written down for the participating species, and a degree of grafting, g, which is the average of number of grafted molecules per monomer unit on the prepolymer backbone, was defined as shown in Equation (19), where Q1 is the concentration of monomer units on prepolymer backbones which remains constant during branching, Ka,3 is the kinetic coefficient for the grafting (additive addition) reaction, and R03 designates a primary radical with radical center on backbone R0. Further mathematical treatment by the authors leads to Equation (20) for calculation of the full chain length distribution of the polymer population, w(r,s), where w0(r) is the initial chain length distribution of the prepolymer [231].

As stated above in Table 14, Gianoglio Pantano et al. [245] developed a very detailed model for grafting of PSty onto PE. Among the concentrations of species calculated by the model, the concentration of poly(ethylene-g-styrene) is calculated using Equation (21), and the concentration of grafted PS, denoted as Gr, is obtained from Equation (22). G(t) is a matrix array of “infinite” size whose elements contain the molar concentrations of the individual species with degree of polymerization indicated by its subscripts. VG is a vector that contains the corresponding reaction rate terms, I1,0 is a bivariate moment of order 1 for PS and order 0 for PE, which represents the mass of PS grafted onto PE, and MPS1 is the molar mass of PS.

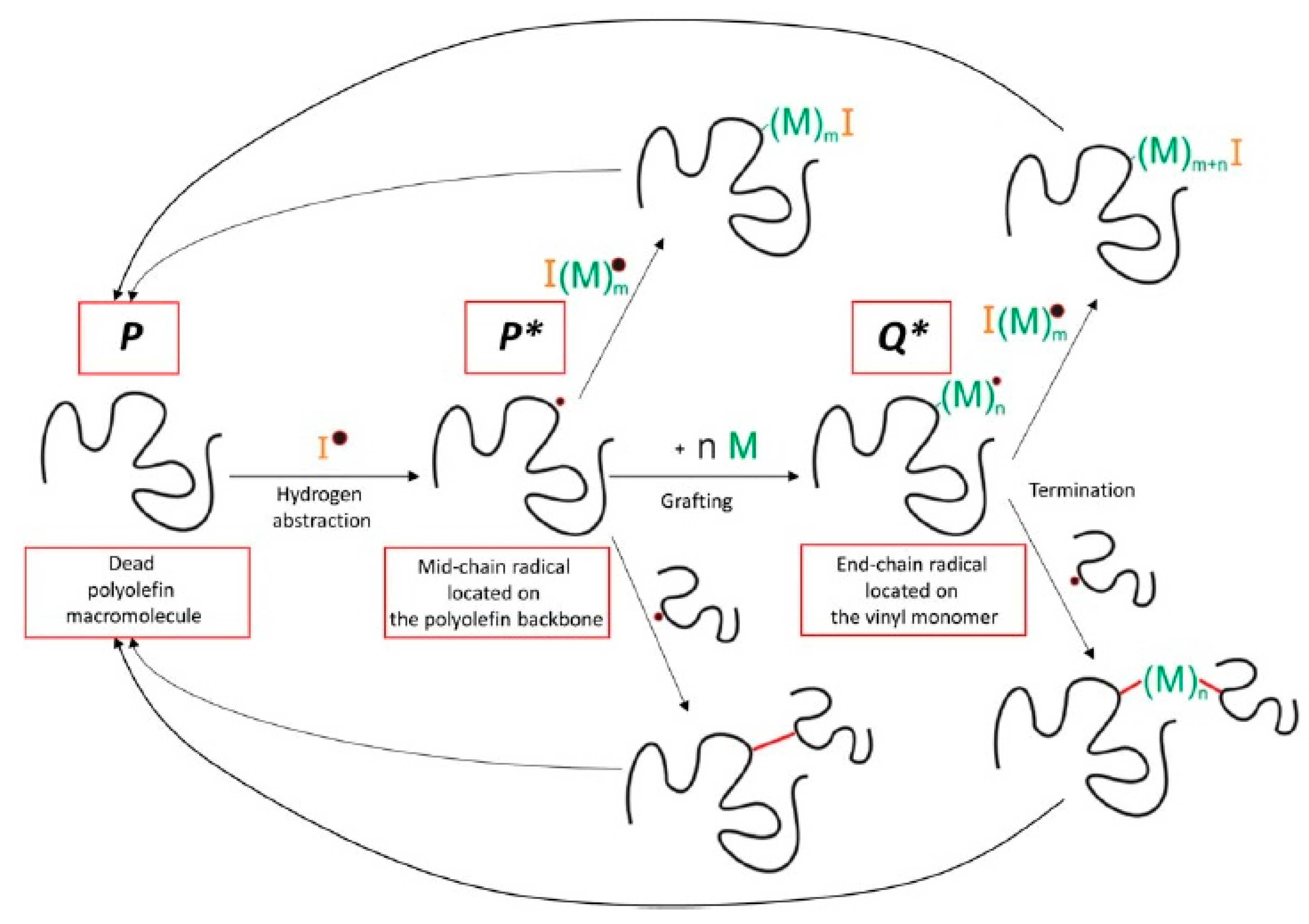

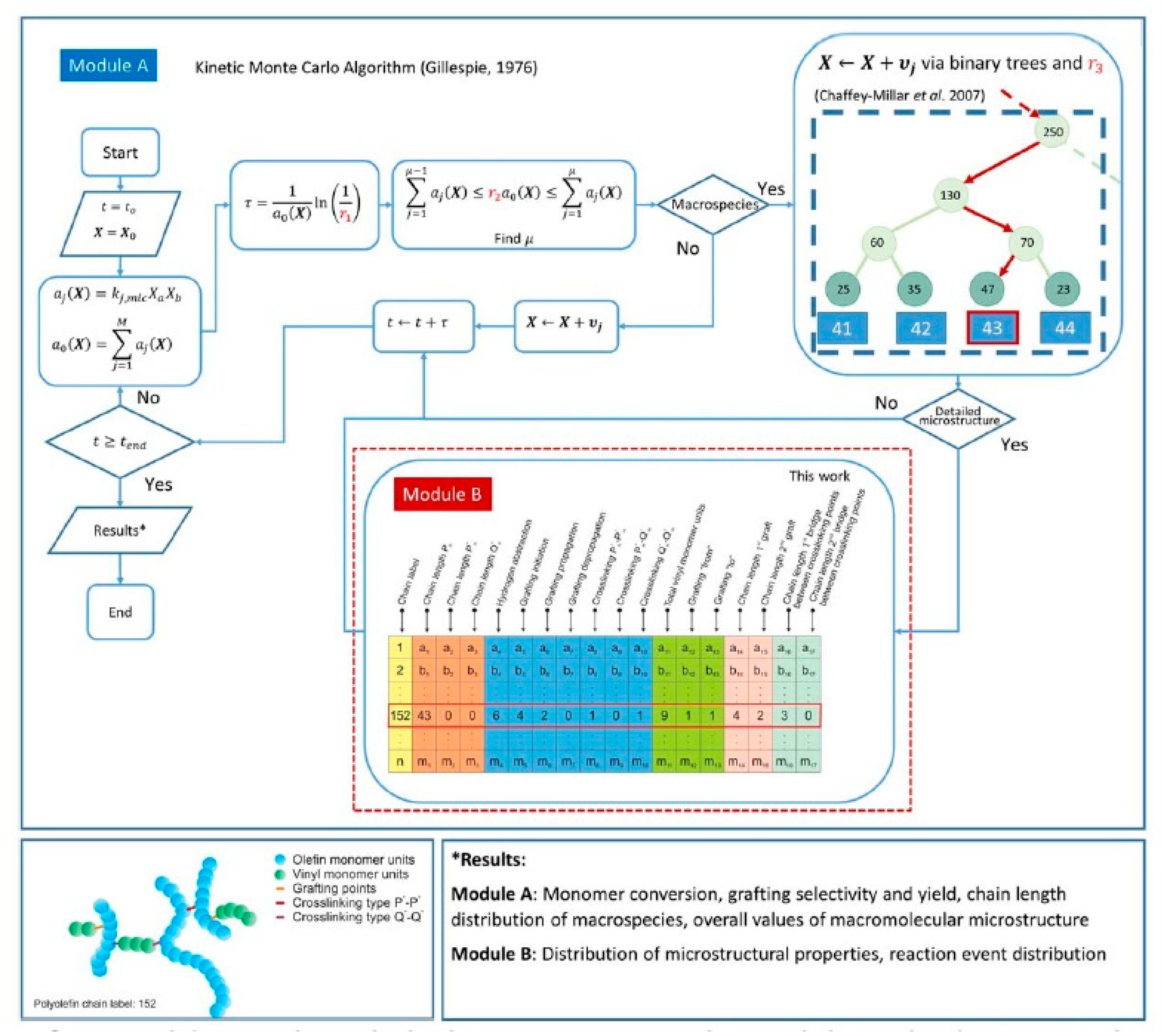

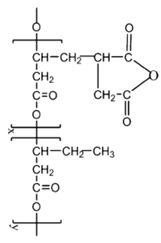

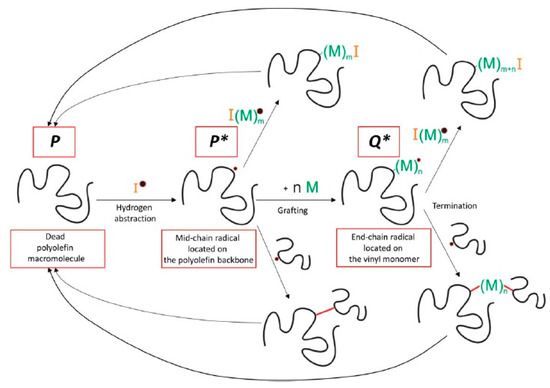

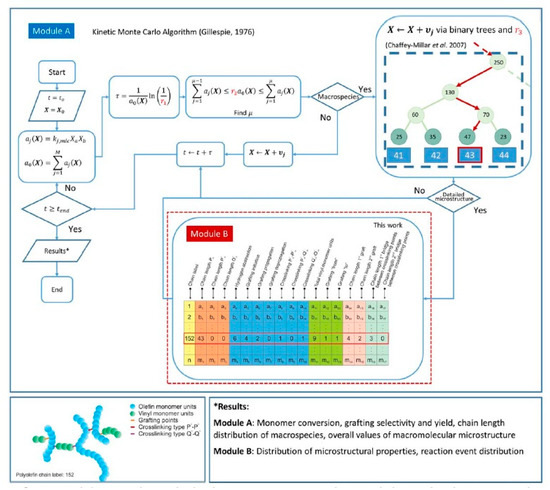

Very detailed simulation studies for the grafting of vinyl polymers onto PE using kMC were presented by Hernández-Ortiz et al. [41,259,260,261]. Some of the key reactions considered in this study are shown in Figure 7 and the modeling strategy is summarized in Figure 8 [259].

Figure 7.

Some of the key reactions present in the grafting of polyolefins with vinyl monomer M. Reprinted with permission from Hernández-Ortiz et al., AIChE J., 63(11), 4944–4961 [259]. Copyright 2017 John Wiley and Sons, New York.

Figure 8.

Simulation approach using kMC for the grafting of polyolefins with vinyl monomer M. Reprinted with permission from Hernández-Ortiz et al., AIChE J., 63(11), 4944–4961 [259]. Copyright 2017 John Wiley and Sons, New York.

6. Nomenclature, Symbols, Abbreviations, and Chemical Structures

7. Conclusions

Polymer grafting is a useful route for the synthesis of materials with interesting mechanical, thermal, dilute solution, and melt properties, and the ability to be compatible with otherwise incompatible mixtures. Systematic studies on polymer chemistry and characterization, and even modeling studies of polymer grafting started in about the 1950s. The interest in the grafting of natural biopolymers has escalated in the last 20 or so years due to environmental and sustainability issues.

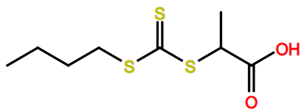

Most of the studies on modeling of polymer grafting have focused on insertion of active sites on the backbone by CTP and growth of grafts by FRP or variants of FRP, such as RDRP. The monomers of major use for polymer grafting purposes are acrylic monomers (MMA, NIPAAM, AM, AA, BA), styrene (STY) and vinyl ethers [140,184]. When fine control of grafted structures is not required, polymer grafting by FRP may be enough. However, when precise control of polymer grafts (size and separation) is required, RDRP techniques, such as NMP, ATRP, and RAFT, are more adequate. RDRP polymer grafting techniques usually proceed by the “grafting-from” route [140,180,184]. One disadvantage of RDRP techniques is that they require longer reaction times. For instance, polymer grafting by RAFT polymerization lasts from 8 to 48 h, plus the time required to prepare the related microcontrollers, which in many cases includes an esterification step through Steglich or anhydride procedures. Polymer grafting by ATRP takes from 24 h to several days.

Polymer grafting by ROP procedures using L-lactide (L-LA) and ε-caprolactone (CL) for the synthesis of poly(l-lactic acid) and poly(ε-caprolactone) polymer grafts is gaining importance [181,182,189]. Other monomers used are 2-ethyl-2-oxazoline, to produce PEOX, and ethylene glycol, to produce PEG. These reactions are commonly conducted at temperatures higher than 80 °C, which complicates solvent selection, when using metal catalysts such as Sn (Oct)2. Solvents should dissolve monomer and polymer, perform adequately at the selected temperatures, and show “green” characteristics. DMF, DMSO, p-dioxane, and toluene are some of the solvents most commonly used for polymer grafting by ROP. However, the recent advent of metal-free and organocatalyzed ROP has facilitated the polymerization at room temperature. For example, poly(lactide) materials can be made by ROP of L-LA at ambient conditions in the presence of 1,5,7-triazabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-ene (TBD) and 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) [272].

Polymer grafting is also important in the synthesis of “dendrigraft copolymers.” A large variety of heterogeneous dendrigraft copolymer architectures with core-shell and core-shell-corona morphologies can be produced, at significantly lower costs than for conventional dendrimer syntheses [18].

As observed in Table 14, the modeling of polymer grafting has focused on CTP or site formation by irradiation with FRP chemistry, in conventional flasks, stirred-tank reactors, or extruders. Other chemical routes have been addressed using semi-empirical approaches only. Therefore, there is still much to do in and contribute to this area.

Author Contributions

E.V.-L. and A.P. conceived the original idea (with discussions with A.R.-A., J.P.-A., M.G.H.-L., and A.M.). E.V.-L., M.G.H.-L., and A.M. assured funding acquisition through a project where experimental and theoretical work on polymer grafting of biopolymers from lignocellulosic biomasses has been carried out and provided background and motivation for this contribution. M.Á.V.-H., G.S.C.-D., A.R.-A., and E.V.-L. carried out critical literature reviews on different topics of the review. M.Á.V.-H., A.R.-A., and E.V.-L. wrote the original draft of the paper; E.V.-L., A.M., A.P., and Y.M. read and corrected different versions of the manuscript and provided extra references and discussion points. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by: (a) Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACYT, México), PhD scholarships granted to M.A.V.-H. and G.S.C.-D.; (b) DGAPA-UNAM, Projects PAPIIT IG100718, IV100119, TA100818, and TA102120, granted to E.V.-L.—the first two—and to A.R.-A.—the last two; and PASPA sabbatical support to E.V.-L. while at the University of Waterloo, in Ontario, Canada; (c) Facultad de Química, UNAM, research funds granted to E.V.-L. (PAIP 5000-9078) and A.R.-A. (PAIP 5000-9167); (d) NSERC funding to A.P.; and (e) the Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Waterloo, Canada, partial sabbatical support to E.V.-L. with research funds from A.P. No funding was received for APC.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hadjichristidis, N.; Pitsikalis, M.; Iatrou, H.; Driva, P.; Chatzichris, M.; Sakellariou, G.; Lohse, D. Graft copolymers. In Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Technology, 2nd ed.; Matyjaszewski, K., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 1–38. ISBN 978-047-144-026-0. [Google Scholar]

- Slagman, S.; Zuilhof, H.; Franssen, M.C.R. Laccase-Mediated Grafting on Biopolymers and Synthetic Polymers: A Critical Review. ChemBioChem 2017, 19, 288–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stannett, V.T. Block and graft copolymerization. In Journal of Polymer Science: Polymer Letters, 1st ed.; Ceresa, R.J., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1973; Volume 1, pp. 669–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, D.J. Theory of block copolymers. I. Domain formation in A-B block copolymers. J. Polym. Sci. C Polym. Symp. 1969, 26, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfand, E.; Block Copolymer Theory. III. Statistical Mechanics of the Microdomain Structure. Macromolecules 1975, 8, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfand, E.; Wasserman, Z.R. Block Copolymer Theory. 4. Narrow Interphase Approximation. Macromolecules 1976, 9, 879–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfand, E. Block copolymers, polymer-polymer interfaces, and the theory of inhomogeneous polymers. Acc. Chem. Res. 1975, 8, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, J.A.; Nielsen, L.E. Characterization of graft polymers. J. Polym. Sci. 1956, 20, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merret, F.M. Graft polymers with preset molecular configurations. J. Polym. Sci. 1957, 24, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, M.S.; Kampf, M.J.; O’brien, L.J.; Fox, T.G.; Graham, R.K. Graft copolymers from polymers having pendant mercaptan groups. II. Synthesis and characterization. J. Polym. Sci. 1959, 37, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.L. Block and graft polymers I. Graft polymers from acrylamide and acrylonitrile. Can. J. Chem. 1957, 36, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beevers, R.B.; White, E.F.T.; Brown, L. Physical properties of vinyl polymers. Part 3.—X-ray scattering in block, random and graft methyl methacrylate + acrylonitrile copolymers. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1960, 56, 1535–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, G.; Oster, G.K.; Moroson, H. Ultraviolet induced crosslinking and grafting of solid high polymers. J. Polym. Sci. 1959, XXXIV, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y. Gamma-ray–induced graft copolymerization of styrene onto cellulose and some chemical properties of the grafted polymer. J. Polym. Sci. 1961, 51, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgeford, D.J. Catalytic Deposition and Grafting of Olefin Polymers into Cellulosic Materials. Ind. Eng. Chem. Prod. Res. Dev. 1962, 1, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.Y.-M.; Immergut, B.; Immergut, E.H.; Rapson, W.H. Grafting vinyl polymers onto cellulose by high energy radiation. I. High energy radiation-induced graft copolymerization of styrene onto cellulose. J. Polym. Sci. A Gen. Pap. 1963, 1, 1257–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, N.; Zhu, S.-H.; Tzoganakis, C.; Penlidis, A. Grafting of ethylene-ethyl acrylate-maleic anhydride terpolymer with amino-terminated polydimethylsiloxane during reactive processing. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 101, 4230–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadena, L.-E.; Gauthier, M. Phase-segregated dendrigraft copolymer architectures. Polymers 2010, 2, 596–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aridi, T.; Gauthier, M. Chapter 6. Arborescent polymers with a mesoscopic scale. In Complex Macromolecular Architectures: Synthesis, Characterization, and Self-Assembly, 1st ed.; Hadjichristidis, N., Hirao, A., Tezuka, Y., Du Prez, F., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 169–194. ISBN 978-047-082-514-3. [Google Scholar]

- Moingeon, F.; Wu, Y.; Cadena-Sánchez, L.; Gauthier, M. Synthesis of arborescent styrene homopolymers and copolymers from epoxidized substrates. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2012, 50, 1819–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitton, G.; Gauthier, M. Arborescent polypeptides from γ-benzyl l -glutamic acid. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2013, 51, 5270–5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aridi, T.; Gauthier, M. Synthesis of arborescent polymers by click grafting. Mater. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 2014, 1613, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockendorff, J.; Gauthier, M. Synthesis of arborescent polystyrene-g-[poly(2-vinylpyridine)-b- polystyrene] core-shell-corona copolymers. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2014, 52, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitton, G.; Gauthier, M. Arborescent micelles: Dendritic poly(γ-benzyl l -glutamate) cores grafted with hydrophilic chain segments. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2016, 54, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, M.; Whitton, G. Arborescent unimolecular micelles: Poly(γ-benzyl L-glutamate) core grafted with a hydrophilic shell by copper(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition coupling. Polymers 2017, 9, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, M.; Aridi, T. Synthesis of arborescent polystyrene by “click” grafting. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2019, 57, 1730–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Semsarilar, M.; Guthrie, J.T.; Perrier, S. Cellulose modification by polymer grafting: A review. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 2046–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohlhauser, S.; Delepierre, G.; Labet, M.; Morandi, G.; Thielemans, W.; Weder, C.; Zoppe, J.O. Grafting Polymers from Cellulose Nanocrystals: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 6157–6189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, D.W.; Hudson, S.M. Review of vinyl graft copolymerization featuring recent advances toward controlled radical-based reactions and illustrated with chitin/chitosan trunk polymers. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 3245–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, V.K.; Thakur, M.K. Recent Advances in Graft Copolymerization and Applications of Chitosan: A Review. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 2637–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, L.; Gupta, G.D. A review on microwave assisted grafting of polymers. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2017, 8, 422–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodin, M.; Vallejos, M.; Opedal, M.T.; Area, M.C.; Chinga-Carrasco, G. Lignocellulosics as sustainable resources for production of bioplastics—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 646–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niphadkar, S.; Bagade, P.; Ahmed, S. Bioethanol production: Insight into past, present and future perspectives. Biofuels 2018, 9, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, J.; Singh, R.; Vijayaraghavan, R.; MacFarlane, D.; Patti, A.F.; Arora, A. Bioactives from fruit processing wastes: Green approaches to valuable chemicals. Food Chem. 2017, 225, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuling, U.; Kaltschmitt, M. Review of Biofuel Production—Feedstock, Processes and Markets. J. Oil Palm Res. 2019, 29, 137–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Hernández, M.Á.; Rosas-Aburto, A.; Vivaldo-Lima, E.; Vázquez-Torres, H.; Cano-Díaz, G.S.; Pérez-Salinas, P.; Hernández-Luna, M.G.; Alcaraz-Cienfuegos, J.; Zolotukhin, M.G. Development of polystyrene composites based on blue agave bagasse by in situ RAFT polymerization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, W.; Venditti, R.; Ayoub, A.; Prochazka, F.; Fernández-de-Alba, C.; Mignard, N.; Taha, M.; Becquart, F. Towards thermoplastic hemicellulose: Chemistry and characteristics of poly-(ε-caprolactone) grafting onto hemicellulose backbones. Mater. Des. 2018, 153, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

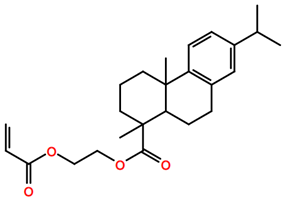

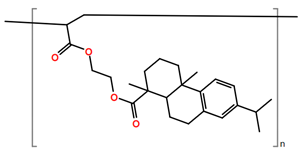

- Sun, Y.; Ma, Z.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, L.; Huang, G.; Liu, L.; Wang, H.; Song, P. Grafting Lignin with Bioderived Polyacrylates for Low-Cost, Ductile, and Fully Biobased Poly(lactic acid) Composites. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 2267–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, T.G.; Gluckman, M.S.; Gornick, F.; Graham, R.K.; Gratch, S. Graft copolymers from polymers having pendant mercaptan groups. I. Kinetic considerations. J. Polym. Sci. 1959, XXXVII, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, J. Molecular weight distributions of vinyl polymers grafted to a solid polymeric substrate by irradiation (theoretical). J. Polym. Sci. 1960, XLIV, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ortiz, J.C.; Van Steenberge, P.H.M.; Duchateau, J.N.E.; Toloza, C.; Schreurs, F.; Reyniers, M.-F.; Marin, G.B.; D’hooge, D.R. A two-phase stochastic model to describe mass transport and kinetics during reactive processing of polyolefins. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 377, 119980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, A.; Verma, S.; Imam, S.S.; Vyas, M. A review on techniques for grafting of natural polymers and their applications. Plant Arch 2019, 19, 972–978. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L.; McDonald, A.G. A Review on Grafting of Biofibers for Biocomposites. Materials 2016, 9, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesús Muñoz Prieto, E.; Rivas, B.; Sánchez, J. Natural polymer grafted with syntethic monomer by microwave for water treatment—A review. Cienc. Desarro. 2012, 4, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsbay, M.; Güven, O. A short review of radiation-induced raft-mediated graft copolymerization: A powerful combination for modifying the surface properties of polymers in a controlled manner. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2009, 78, 1054–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, R.; Joy, N.; Aparna, E.P.; Vijayan, R. Polymer Grafted Inorganic Nanoparticles, Preparation, Properties, and Applications: A Review. Polym. Rev. 2014, 54, 268–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Valdez, O.; Champagne, P.; Cunningham, M.F. Graft modification of natural polysaccharides via reversible deactivation radical polymerization. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2018, 76, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, L.; Thompson, M.P.; Schara, S.; Cao, W.; Choi, W.C.; Hu, Z.; Zang, N.; Tan, W.; Gianneschi, N.C. Recent Advances in Amphiphilic Polymer–Oligonucleotide Nanomaterials via Living/Controlled Polymerization Technologies. Bioconjugate Chem. 2019, 30, 1889–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, T.C. Synthesis of functional polyolefin copolymers with graft and block structures. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2002, 27, 39–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Wu, S.; Wang, X.; Cui, Z.; Yang, X.; Chu, P.K. Surface functionalization of biomaterials by radical polymerization. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2016, 83, 191–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyavoo, J.; Nguyen, T.P.N.; Jun, B.-M.; Kim, I.-C.; Kwon, Y.N. Protection of polymeric membranes with antifouling surfacing via surface modifications. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 506, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Hoogenboom, R.; Schubert, U.S. Temperature responsive bio-compatible polymers based on poly(ethylene oxide) and poly(2-oxazoline)s. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 686–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Choi, W.; Zang, N.; Battistella, C.; Thompson, M.P.; Cao, W.; Zhou, X.; Forman, C.; Gianneschi, N.C. Bioactive Peptide Brush Polymers via Photoinduced Reversible-Deactivation Radical Polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 17359–17364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Sharma, R.K.; Singh, A.P. Grafted cellulose: A bio-based polymer for durable applications. Polym. Bull. 2018, 75, 2213–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Kumar, A. Lignin. Biosynthesis and Transformation for Industrial Applications; Springer Series on Polymer and Composite Materials; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–252. ISBN 978-303-040-663-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mourya, V.K.; Inamdar, N.N. Chitosan-modifications and applications. React. Funct. Polym. 2008, 68, 1013–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argüelles-Monal, W.M.; Lizardi-Mendoza, J.; Fernández-Quiroz, D.; Recillas-Mota, M.T.; Montiel-Herrera, M. Chitosan Derivatives: Inducing new functionalities with a controlled molecular architecture for innovative materials. Polymers 2018, 10, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurita, K. Controlled functionalization of the polysaccharide chitin. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2001, 26, 1921–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lele, V.V.; Kumari, S.; Niju, H. Syntheses, characterization and applications of graft copolymers of sago starch. Starch 2018, 70, 1700133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, B.; Ranjan, R.; Brittain, W.J. Surface initiated polymerization from silica nanoparticles. Soft Matter 2006, 2, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, J.C.; Radzinsky, S.C.; Matson, J.B. Graft polymer synthesis by RAFT transfer-to. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2017, 55, 2865–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A. Radiation and industrial polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2000, 25, 371–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmet, T.; Morent, R.; De Geyter, N.; Leys, C.; Schacht, E.; Dubruel, P. Nonthermal plasma technology as a versatile strategy for polymeric biomaterials surface modification: A review. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 2351–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, T.H.A.; Tran, D.T.; Dinh, C.H. Surface photochemical graft polymerization of acrylic acid onto polyamide thin film composite membranes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 44418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Tiwari, A.; Tripathi, D.N.; Sanghi, R. Microwave assisted synthesis of guar-g-polyacrylamide. Carbohydr. Polym. 2004, 58, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Misra, B.N. Grafting: A versatile means to modify polymers technics, factors and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2004, 29, 767–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnik, A.; Gotelli, G.; Abraham, G.A. Microwave-assisted polymer synthesis (MAPS) as a tool in biomaterials science: How new and how powerful. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 1050–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Pandey, J.; Raj, V.; Kumar, P. A review on the modification of polysaccharide through graft copolymerization for various potential applications. Open Med. Chem. J. 2017, 11, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z. Grafting modification of kevlar fiber using horseradish peroxidase. Polym. Bull. 2006, 56, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannatelli, M.D.; Ragauskas, A.J. Conversion of lignin into value-added materials and chemicals via laccase-assisted copolymerization. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 8685–8691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, J.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, T. Atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP): A versatile and forceful tool for functional membranes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 124–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.E. Extrusion-back to the future: Using an established technique to reform automated chemical synthesis. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moad, G. The synthesis of polyolefin graft copolymers by reactive extrusion. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1999, 24, 81–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moad, G. Chemical modification of starch by reactive extrusion. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 218–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, K.E. Free radical graft polymerization and copolimerization at higher temperatures. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2002, 27, 1007–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monties, B. Les Polymères Végétaux: Polymères Pariétaux et Alimentaires non Azotés, 1st ed.; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, France, 1980; ISBN 978-204-010-480-1. [Google Scholar]

- Casarrubias-Cervantes, R.A. Análisis Fisicoquímico de Procesos de Pretratamiento de Materiales Lignocelulósicos para su Uso en Polímeros Conductores. Bachelor Degree, Facultad de Química—Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, CDMX, 2019, Biblioteca Digital UNAM. Available online: http://132.248.9.195/ptd2019/abril/0788572/Index.html (accessed on 25 May 2020).

- Koshijima, T.; Muraki, E. Radiation Grafting of Methyl Methacrylate onto Lignin. J. Jpn. Wood Res. Soc. 1964, 10, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Koshijima, T.; Muraki, E. Degradation of Lignin-Methyl Metacrylate Graft Copolymer by γ-Ray Irradiation. J. Jpn. Wood Res. Soc. 1964, 10, 116–119. [Google Scholar]

- Koshijima, T.; Timell, T.E. Factors Affecting Number Average Molecular Weights Determination of Hardwood Xylan. J. Jpn. Wood Res. Soc. 1966, 12, 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Koshijima, T.; Muraki, E. Solvent Effects upon Radiation-Induced Graft-copolymerization of Styrene onto Lignin. J. Jpn. Wood Res. Soc. 1966, 12, 139. [Google Scholar]

- Koshijima, T. Oxidation of Lignin-Styrene Graft polymer. J. Jpn. Wood Res. Soc. 1966, 12, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Koshijima, T.; Muraki, E. Radial Grafting on Lignin (II). Grafting of styrene into Lignin by Initiators. J. Jpn. Wood Res. Soc. 1967, 13, 355–358. [Google Scholar]

- Koshijima, T.; Muraki, E.; Naito, K.; Adachi, K. Radical Grafting on Lignin. IV. Semi-Conductive Properties of Lignin-Styrene Graftpolymer. J. Jpn. Wood Res. Soc. 1968, 14, 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Meister, J.J. Modification of Lignin. J. Macromol. Sci. Polymer Rev. 2002, 42, 235–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, D.N.S. Chemical Modification of Lignocellulosic Materials, 1st ed.; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-082-479-472-9. [Google Scholar]

- McDowall, D.J.; Gupta, B.S.; Stannett, V.T. Grafting of vinyl monomers to cellulose by ceric ion initiation. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1984, 10, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.N.; Maldas, D. Graft copolymerization onto cellulosics. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1984, 10, 171–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, D.N.S. Graft Copolymerization of Lignocellulosic Fibers; ACS Symposium Series 187; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1982; ISBN 978-084-120-721-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, O.Y.; Nagaty, A. Grafting of synthetic polymers to natural polymers by chemical processes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1985, 11, 91–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, D.; Lacasse, M.; Bernaczuk, L.M. Lignin-polymer sytems and some applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1986, 12, 271–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyjaszewski, K.; Möller, M. Celluloses and polyoses/hemicelluloses. In Polymer Science: A Comprehensive Reference; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 978-008-087-862-1. [Google Scholar]

- Pantelakis, S.; Tserpes, K. Revolutionizing Aircraft Materials and Processes; Springer Nature AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-303-035-346-9. [Google Scholar]

- Rol, F.; Belgacem, M.N.; Gandinia, A.; Bras, J. Recent advances in surface-modified cellulose nanofibrils. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2019, 88, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahran, M.K.; Morsy, M.; Mahmoud, R. Grafting of acrylic monomers onto cotton fabric using an activated cellulose thiocarbonate–azobisisobutyronitrile redox system. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 91, 1261–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, G.S.; Lal, H.; Sharma, R.; Sarwade, B.D. Grafting of a styrene–acrylonitrile binary monomer mixture onto cellulose extracted from pine needles. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 83, 2000–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaa, M.W.; Mokhtar, S.M. Chemically induced graft copolymerization of itaconic acid onto cellulose fibers. Polym. Test. 2002, 21, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.C.; Sahoo, S. Grafting of N,N ′-methylenebisacrylamide onto cellulose using Co(III)-acetylacetonate complex in aqueous medium. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2000, 76, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.C.; Sahoo, S. Co(III) acetylacetonate-complex-initiated grafting of N-vinyl pyrrolidone on cellulose in aqueous media. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 81, 2286–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.C.; Khandekar, K. Temperature-Responsive Cellulose by Ceric(IV) Ion-Initiated Graft Copolymerization of N-Isopropylacrylamide. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.C.; Khandekar, K. Graft copolymerization of acrylamide–methylacrylate comonomers onto cellulose using ceric ammonium nitrate. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2002, 86, 2631–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.C.; Khandekar, K. Graft copolymerization of acrylamide onto cellulose in presence of comonomer using ceric ammonium nitrate as initiator. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 101, 2546–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.C.; Sahoo, S. Graft Copolymerization of Acrylonitrile and Ethyl Methacrylate Comonomers on Cellulose Using Ceric Ions. Biomacromolecules 2001, 2, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.C.; Sahoo, S.; Khandekar, K. Graft Copolymerization of Ethyl Acrylate onto Cellulose Using Ceric Ammonium Nitrate as Initiator in Aqueous Medium. Biomacromolecules 2002, 3, 1087–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, K.C.; Khandekar, K. Ceric(IV) ion-induced graft copolymerization of acrylamide and ethyl acrylate onto cellulose. Polym. Int. 2005, 55, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledano-Thompson, T.; Loría-Bastarrachea, M.I.; Aguilar-Vega, M.J. Characterization of henequen cellulose microfibers treated with an epoxide and grafted with poly(acrylic acid). Carbohydr. Polym. 2005, 62, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, O.Y.; Nagieb, Z.A.; Basta, A.H. Graft polymerization of some vinyl monomers onto alkali-treated cellulose. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1991, 43, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semsarilar, M.; Ladmiral, V.; Perrier, S. Synthesis of a cellulose supported chain transfer agent and its application to RAFT polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2010, 48, 4361–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cankaya, N.; Temüz, M. Characterization and monomer reactivity ratios of grafted cellulose with n-(4-nitrophenyl)acrylamide and methyl methacrylate by atom transfer radical polymerization. Cell. Chem. Technol. 2012, 46, 551–558. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, V.K.; Thakur, M.K.; Gupta, R.K. Rapid synthesis of graft copolymers from natural cellulose fibers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 98, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routray, C.; Tosh, B. Graft copolymerization of methyl methacrylate (mma) onto cellulose acetate in homogeneous medium: Effect of solvent, initiator and homopolymer inhibitor. Cell. Chem. Technol. 2013, 47, 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Cankaya, N.; Temüz, M.M. Monomer reactivity ratios of cellulose grafted with N-cyclohexylacrylamide and methyl methacrylate by atom transfer radical polymerization. Cell. Chem. Technol. 2014, 48, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, O.; Dunca, S.; Grigoriu, A. Antibacterial action of silver applied on cellulose fibers grafted with monochlorotriazinyl-β-cyclodextrin. Cell. Chem. Technol. 2013, 47, 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, O.; Grigoriu, A.; Diaconescu, R.M.; Vasluianu, E. Optimization of the cellulosic materials functionalization with monochlorotriazinyl-β-cyclodextrin in basic medium. Ind. Textilá 2012, 63, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Chen, F. Homogeneous grafting copolymerization of methylmethacrylate onto cellulose using ammonium persulfate. Cell. Chem. Technol. 2014, 48, 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, L.; Shen, Y.; Li, D.; Xiao, S.; He, J. Cellulose-graft-poly(l-lactide) as a degradable drugdelivery system: Synthesis, degradation and drug release. Cell. Chem. Technol. 2014, 48, 237–245. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoming, S.; Songlin, W.; Shanshan, G.; Fushan, C.; Fusheng, L. Study on grafting copolymerization of methyl methacrylate onto cellulose under heterogeneous conditions. Cell. Chem. Technol. 2016, 50, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Y.; Jiang, T.X.; Wang, H.; Gao, W. Modification of cellulose nanocrystal via SI-ATRP of styrene and themechanism of its reinforcement of polymethylmethacrylate. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 142, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paula, E.L.; Roig, F.; Mas, A.; Habas, J.P.; Mano, V.; Vargas Pereira, F.; Robin, J.J. Effect of surface-grafted cellulose nanocrystals on the thermal and mechanical properties of PLLA based nanocomposites. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 84, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, J.; He, B.; Zhao, L. Fabrication of hydrophobic biocomposite by combining cellulosic fibers with polyhydroxyalkanoate. Cellulose 2017, 24, 2265–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, S.M. Functional cellulosic filter papers prepared by radiation-induced graft copolymerization for chelation of rare earth elements. Cell. Chem. Technol. 2017, 51, 551–558. [Google Scholar]

- Çankaya, N.; Temüz, M.M.; Yakuphanoglu, F. Grafting of some monomers onto cellulose by atom transfer radical polymerization. Electrical conductivity and thermal properties of resulting copolymers. Cell. Chem. Technol. 2018, 52, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Müssig, J.; Kelch, M.; Gebert, B.; Hohe, J.; Luke, M.; Bahners, T. Improvement of the fatigue behaviour of cellulose/polyolefin composites using photo-chemical fibre surface modification bio-inspired by natural role models. Cellulose 2020, 27, 5815–5827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, Z.; Han, Y.; Yang, S.; Fan, D.; Li, G.; Wang, S. Combination of water soluble chemical grafting and gradient freezing to fabricate elasticity enhanced and anisotropic nanocellulose aerogels. Appl. Nanosci. 2020, 10, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraghi Kazzaz, A.; Hosseinpour Feizi, Z.; Fatehi, P. Grafting strategies for hydroxy groups of lignin for producing materials. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 5714–5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, A.; Dusek, K.; Kobayashi, S. Biopolymers. Lignin, Proteins, Bioactive Nanocomposites, 1st ed.; Springer: Heidelberg/Berlin, Germany, 2010; Volume 232, ISBN 978-364-213-630-6. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Fu, S.; Gan, L. Lignin Chemistry and Applications, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 978-012-813-963-9. [Google Scholar]

- Marton, J. Lignin. Structure and Reactions, 1st ed.; Advances in Chemistry Series 59; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1966; ISBN 978-084-122-239-7. [Google Scholar]

- Glasser, W.G.; Sarkanen, S. Lignin. Properties and Materials, 1st ed.; ACS Symposium Series 397; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-084-121-248-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, N.G.; Sarkanen, S. Lignin and Lignan Biosynthesis; ACS Symposium Series 697; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; ISBN 084-123-566-X. [Google Scholar]

- Katahira, R.; Elder, T.J.; Beckham, G.T. Chapter 1 A brief introduction to lignin structure. In Lignin Valorization. Emerging Approaches, 1st ed.; Beckham, G.T., Ed.; The Royal Society of Chemistry: Croydon, London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-178-801-035-1. [Google Scholar]

- Laurichesse, S.; Avérous, L. Chemical modification of lignins: Towards biobased polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 1266–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, P.; Lintinen, K.; Hirvonen, J.T.; Kostiainen, M.A.; Santos, H.A. Properties and chemical modifications of lignin: Towards lignin-based nanomaterials for biomedical applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 93, 233–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yuan, L.; Wang, Z.; Wilbon, P.A.; Wang, C.; Chu, F.; Tang, C. Lignin and soy oil-derived polymeric biocomposites by “grafting from” RAFT polymerization. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 4974–4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Fu, S.; Song, P.; Lou, X.; Jin, Y.; Lu, F.; Wu, Q.; Ye, J. Functionalized lignin by grafting phosphorus-nitrogen improves the thermal stability and flame retardancy of polypropylene. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2012, 97, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieur, B.; Meub, M.; Wittermann, M.; Klein, R.; Bellayer, S.; Fontaine, G.; Bourbigot, S. Phosphorylation of lignin: Characterization and investigation of the thermal decomposition. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 16866–16877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieur, B.; Meub, M.; Wittemann, M.; Klein, R.; Bellayer, S.; Fontaine, G.; Bourbigot, S. Phosphorylation of lignin to flame retard acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS). Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2016, 127, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chung, H. Lignin-Based Polymers via Graft Copolymerization. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2017, 55, 3515–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, C.; Washburn, N.R. Polymer-grafted lignin surfactants prepared via Reversible Addition−Fragmentation Chain-Transfer polymerization. Langmuir 2014, 30, 9303–9312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganewatta, M.S.; Lokupitiya, H.N.; Tang, C. Lignin biopolymers in the age of controlled polymerization. Polymers 2019, 11, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kadla, J.F. Preparation of a thermoresponsive lignin-based biomaterial through atom transfer radical polymerization. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yao, J.; Korich, K.; Li, S.; Ma, S.; Ploehn, H.J.; Iovine, P.M.; Wang, C.; Chu, F.; Tang, C. Combining renewable gum rosin and lignin: Towards hydrophobic polymer composites by controlled polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2011, 49, 3728–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, B.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Li, J. Biomass-based thermogelling copolymers consisting of lignin and grafted poly (N-isopropylacrylamide), poly (ethylene glycol), and poly (propylene glycol). RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 42996–43003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Tang, C.; Chu, F. UV-Absorbent Lignin-Based Multi-Arm Star Thermoplastic Elastomers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2015, 36, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Dallmeyer, J.I.; Kadla, J.F. Synthesis of lignin nanofibers with ionic-responsive shells: Water-expandable lignin-based nanofibrous mats. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 3602–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilburg, S.L.; Elder, A.N.; Chung, H.; Ferebee, R.L.; Bockstaller, M.R.; Washburn, N.R. A universal route towards thermoplastic lignin composites with improved mechanical properties. Polymer 2014, 55, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]