Abstract

The use of food packaging derived from petroleum-based polymers has developed significant environmental problems, as these materials require centuries to degrade and release hazardous pollutants. Consequently, the food industry is shifting toward biodegradable alternatives developed from agro-industrial by-products, such as proteins, polysaccharides, and lipids. Whey protein is a by-product of the cheese industry, which is emerging as a promising material for producing edible and biodegradable films with effective barrier properties. Whey-based films can be incorporated with bioactive compounds, particularly phenolic compounds. These substances, naturally present in fruits, legumes, and vegetable waste, possess potent antimicrobial and antioxidant activities that are essential for extending the shelf life of perishable foods. This review provides a systematic evaluation of how the incorporation of phenolic compounds influences the physicochemical and bioactive properties of whey-based films. Thus, an analysis of film-forming methods, the interaction between protein matrices and phenolic compounds, and a critical discussion of the challenges remaining for their industrial application as active food packaging were evaluated. The discussion focuses on how the incorporation of phenolic extracts influences the physicochemical, mechanical, and barrier properties of the films, as well as their antioxidant and antimicrobial efficiency. The novelty of this review lies in its comprehensive focus on the sustained release of phenolic compounds from a whey protein film and their application in real food systems. By utilizing these natural additives, the industry can provide sustainable alternatives to synthetic preservatives. Active whey protein packaging represents a viable strategy to inhibit food spoilage, prevent lipid oxidation, and maintain sensory quality, while reducing the environmental problems.

1. Introduction

The food industry widely uses plastic packaging with the main goal of containing and protecting food before consumption [1,2]. Many of these packages are elaborated by petroleum-based materials, such as polyethylene and polypropylene. However, incorrect disposal of these can lead to pollution in landfills, rivers, oceans, and it represents an environmental problem, as these polymers are not biodegradable [3,4,5]. Furthermore, the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to an increase in plastic waste. The main causes of the increase in this waste are the use of plastic for medical purposes and food packaging [5,6].

Biodegradable films are being studied and developed from natural renewable sources, such as polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids [1,7], to reduce the adverse effects of packaging and petroleum-based materials [1]. These films can be degraded in environmental conditions by the action of microorganisms, soil conditions, water, and other factors [3,7]. The utilization of whey protein for the elaboration of biodegradable films has gained attention. Milk has two proteins, casein (~80%) and whey (~20%), and whey is a highly globular protein powder derived from cow’s milk. Films from whey protein are interesting due to their biodegradable, eco-friendly, film-forming, and nutrient-rich properties, with good barrier properties against oxygen, aromatic compounds, and oil [7,8].

Natural compounds, such as phenolic compounds, can be incorporated into these matrices to create active films [7,8,9]. These films can protect food products by preventing physical damage, moisture absorption, and steam. Furthermore, they can act as a barrier to microorganisms, oxidation, and other causes of food spoilage. The interaction of phenolic compounds with the bacterial cell membrane can modulate its permeability, resulting in the loss of cell integrity and subsequent bacterial death [3,8].

The incorporation of active compounds into whey films is promising, combining the film-forming potential of whey with the bioactive capacity of natural compounds because phenolic components show strong antioxidants and antimicrobial activities [3]. While promising, the development of these materials faces challenges related to formulation optimization. Specifically, it is difficult to achieve a balance that preserves both desirable mechanical properties and adequate barrier of these films [3,10]. According to Phoolklang et al. [10], phenolic compounds can increase the water resistance (WR) of the film, but some extracts had a negative effect in WR, because different types of extracts have varying effects on film properties. This resistance can be attributed to the hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonds formed between the phenolic compounds and the polar groups in protein film matrix, which reduced the inter-chain space of matrix and the availability of amino and OH groups and hindered the binding with water.

Phenolic compounds are natural substances known to have one or more unique aromatic rings coupled to a hydroxyl group. Phenolic compounds are secondary metabolites in plants, generally found in vegetables, fruits, tea, and wine, among other sources [11,12,13]. They are responsible for organoleptic characteristics, such as bitterness and color, and act as plant defense strategies [14]. However, they can also be obtained from unconventional parts of plants characterized by being by-products, such skin and other parts [15]. Studies are being carried out with the incorporation of phenolic compounds from different sources, such as rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum) and peanut skin (Arachis hypogaea L.), among others, in biodegradable films [15,16], with promising results being reported. This review provides a systematic evaluation of how the incorporation of phenolic compounds influences the physicochemical and bioactive properties of whey-based films. Thus, an analysis of film-forming methods, the interaction between protein matrices and phenolic compounds, and a critical discussion of the challenges remaining for their industrial application as active food packaging were evaluated.

2. Biodegradable Films

A film can be defined as a pre-formed thin layer, developed from biopolymers, which, after formation, can be used as food packaging [17]. Films can be made using biopolymers, which are biologically based polymers with a biodegradable nature, with proteins, lipids, and polysaccharides being the most widely used [1,7].

Biodegradable films are an alternative replacement for synthetic polymers, due to their fast decomposition by the action of microorganisms. Extracellular enzymes secreted by microorganisms catalyze the primary biodegradation processes for biopolymers, including the hydrolysis of ester bonds to liberate monomers [1,18]. Furthermore, biopolymers can be made from natural, renewable, low-cost sources, which can form a continuous matrix and are found in large quantities in by-products from agroindustry, such as polysaccharides and proteins [19].

Several studies seek to develop films from raw materials, such as whey proteins [20], soy [19] and corn [3], as well as collagen and gelatine [21], in addition to polysaccharides such as starch [22], and chitosan [23], among others. In this context, protein films showed a good barrier to oxygen and other gases with good mechanical resistance. However, protein films are sensitive to humidity [20].

Whey proteins have been gaining prominence in the production of active edible films and coatings for food packaging. In cheese production, whey is generated as a by-product, which deserves special attention as it is possible to obtain an isolated protein with more than 90% protein and concentrated protein between 35% and 80% protein [24]. Thus, whey and dairy products have stood out in the production of biodegradable films, as they form films with important characteristics, such as transparency, flexibility, absence of taste and odor, as well as mechanical and oxygen barrier properties [25]. Furthermore, they can serve as a matrix for the incorporation of bioactive compounds, which can be released into food, which is one of the active film characteristics [20].

When incorporated into films, these bioactive compounds with antimicrobial and antioxidant effects interact with the product and can improve its conservation through the release or absorption of compounds [26]. Therefore, the bioactive film can protect the food from lipid oxidation and spoilage and/or pathogenic microorganisms, increasing the shelf life of the food and improving the quality of the product [2,27]. According to Li and Chan [28], whey protein concentrate (WPC) and whey protein isolate (WPI) films were rapidly degraded in a compost pile, showing visible darkening within two days, with over 80% of total solids lost in a week.

2.1. Production of Whey Protein Films and Derivatives

Cow’s milk contains proteins casein (nearly 80%) and whey (nearly 20%) [29]. Temperature, pH, shear forces, and organic solvents result in protein unfolding and dissociation. Whey proteins are globular proteins, and the initial step is protein unfolding by relieving low-energy intermolecular bonds [29,30].

Biodegradable protein films are obtained through the homogenization of a polymer matrix, a solvent, a plasticizer, and an adjustment of pH, which are subjected to heat treatment. Biodegradable whey protein films (WPF) can be elaborated from protein isolate (WPI, >90% protein) or concentrate (WPC, 35–80% protein) in different concentrations, and their formation depends on the thermal denaturation of the protein in aqueous solutions to obtain strength, resistance, and poor solubility in water [31,32].

Films without plasticizers are very brittle and have little elasticity, which makes their use unfeasible. The plasticizers, which have good compatibility with films, are used to improve the elasticity and extensibility of films [31,32,33]. The most used plasticizers are water, polyols (glycerol and sorbitol), monosaccharides (fructose and glucose), disaccharides (sucrose), and lipids (fatty acids) [31,33]. Plasticizers modify the structure of bonds and reduce intermolecular forces, due to their ability to restrict hydrogen bonds between polymer chains, reducing their rigidity. As a result, they increase the mobility of polymer chains and improve film properties, contributing to reducing fragility, and increasing flexibility and extensibility [31,32].

In the formation of films based on whey and derivatives, the most used plasticizer is glycerol, This occurs due to its structure and hydrophilic nature, facilitating incorporation and compatibility with macromolecules [32] at the time of homogenization with the polymer and solvent. Therefore, the separation of these components is avoided, reducing the formation of hydrogen bonds and causing an increase in the free volume of the polymer [33]. Additionally, when formulating the films, in addition to the film-forming agent (macromolecule) and the plasticizer, it is essential to add a solvent, such as water or ethanol, to solubilize the polymer matrix [9,31,32].

In many studies regarding the production of films using whey protein, the denaturation temperature range used was between 75 and 100 °C, which promotes the unfolding of globular whey proteins, exposing internal hydrophobic groups that later form intermolecular disulfide (S–S) bonds during drying. This molecular reorganization is what ultimately results in a more resistant and water-insoluble matrix [20,31,34,35]. This occurs because β-lactoglobulin, one of the major proteins in whey, is denatured at temperatures above 60–70 °C [31,36]. Briefly, temperature favors the denaturation of protein molecules, causing a modification of the 3-D structure of whey proteins by exposing internal hydrophobic groups, and, after drying, these S–H groups stimulate links between intermolecular and hydrophobic S–S bonds [29,37]. This causes the bonds to be ordered during drying, obtaining stronger, more resistant, and water-insoluble films [38].

It is also known that the pH of protein solubilization can directly influence the properties of the films [31,39]. This parameter alters the electrostatic repulsion between protein chains, as it favors hydrogen bonds. This electrostatic repulsion occurs when the pH is far from the isoelectric point (pI) of the proteins. For instance, adjusting the pH away from the isoelectric point (pI) of β-lactoglobulin (pH 5.2) or α-lactalbumin (pH 4.2–4.8) is crucial to induce electrostatic repulsion, which facilitates protein solubilization and ensures a homogeneous film-forming solution (FS) [31,36]. When the pH is between 5–6, that is, at the pI or close to it, proteins accumulate, and their precipitation occurs [39]. However, at pHs above the pI, the protein has a net negative charge, and, when below its pI, it has a net positive charge. Therefore, these excess charges of protein molecules interact with water molecules, contributing to their solubilization [39,40]. So, to obtain a more homogeneous film, pH adjustment is carried out with acid or base, such as acetic, ascorbic acid, and sodium hydroxide, among others, aiming for the macromolecule to reach maximum solubility [9,31,33,39,40].

Due to their hydrophilic nature, these films are highly permeable to water, which limits their application in products that require a moisture barrier, such as cookies [41]. Guimarães et al. [25] incorporated lactic acid bacteria Lactobacillus buchneri and Lactobacillus casei (10, 20, or 30%) in films of whey protein concentrate (10%; w/w) to evaluate the antifungal effect on cheeses. Films containing different concentrations of L. buchneri showed antifungal activity during 30 days of storage. Furthermore, the properties of these films did not change when compared to the control film (without the addition of lactic acid bacteria).

Ampessan and Giarola [42] produced films using whey protein isolate as a macromolecule, glycerol as a plasticizer, and coconut oil at concentrations of 1, 2, and 3%. The films presented antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant properties. An increase in coconut oil concentration from 1% to 3% caused the film thickness to rise from 1.2 mm to 1.5 mm. This is because the added hydrophobic substance induces molecular interactions and reorganization during the film’s formation and drying stages [42].

Silva et al. [43] developed blends based on a whey protein isolate (5%) using glycerol (2%) and dispersed in water. Different concentrations of pectin (0.5%, 1%, and 2%) were added and the pH was adjusted to 3.0. For films without pectin, the pH was adjusted to 7.0, at 75 °C. The solubility of the film with 1% pectin was higher (75.3%) when compared to the control film (66.8%). The tensile strength varied from 0.94 MPa and 2.12 MPa, for the films added with 0.5 and 2% pectin, respectively. The elongation at break of films with pectin decreased when compared to the control film, demonstrating a reduction in the mechanical properties of the film added with pectin.

Andrade et al. [34] developed bioactive films based on whey protein concentrate (8%, w/w), with glycerol (8%, w/w) as a plasticizer, water as solvent (83%, w/w), and incorporated with rosemary extract (1%, w/w) to inhibit or delay lipid oxidation of salami slices. This solution was heated to a temperature of 80 °C for better interaction between the protein chains. The active films showed a reduction in lipid oxidation with a hexanal amount of approximately 70 μg/100 g after 90 days when compared to fresh salami (without coating), which presented approximately 140 μg/100 g.

Kontogianni et al. [35] created films based on whey protein concentrate using glycerol as a plasticizer, and rosemary and sage extracts (2%) as bioactive compounds, at 75 °C and pH 5.5. They observed that the solubility of films with sage extract increased from 25.2% (control) to 26.3%. The film containing rosemary extract showed higher solubility (28.7%) when compared to the control film (25.2%). The tensile strength of films with added rosemary extract (1.44 MPa) and sage extract (1.56 MPa) showed a higher value when compared to the control film (1.33 MPa). However, the elongation and rupture decreased in the films containing the different extracts, which may have been caused by the reduction in mobility between the interactions of the polyphenolic compounds within the polymer chain.

Agudelo-Cuartas et al. [20] prepared films of whey protein concentrate (10%) in distilled water added with glycerol (5%), and tocopherol (2%), Natamycin (0.0123 ppm), or a mixture of both, at pH 7 and 90 °C. The films incorporated with active compounds showed lower tensile strength (3.3 MPa tocopherol, 6.4 MPa Natamycin, and 5.9 MPa with the two active compounds) and an increase in elongation at break (45.6% Natamycin, 48.6% tocopherol, and 46.4% with both), when compared to the control film (10.8 MPa; 29.4%). These results indicate that tocopherol and Natamycin acted as plasticizers in the film.

2.2. Film Elaboration

2.2.1. Casting Technique

In the formation of films based on whey and derivatives, as shown in Table 1, are used some raw materials and compounds by casting. It is based on the solubilization of the polymer (macromolecule) in the solvent and the incorporation of plasticizers, thus obtaining the film-forming solution. The FS is dispersed in molds or plates, using different materials, such as glass, Teflon, and plastic, among others. Subsequently, they are dried through solvent evaporation, thus obtaining films, consisting of continuous and cohesive matrices [20,35,44].

Table 1.

Films based on whey protein and derivatives by casting method.

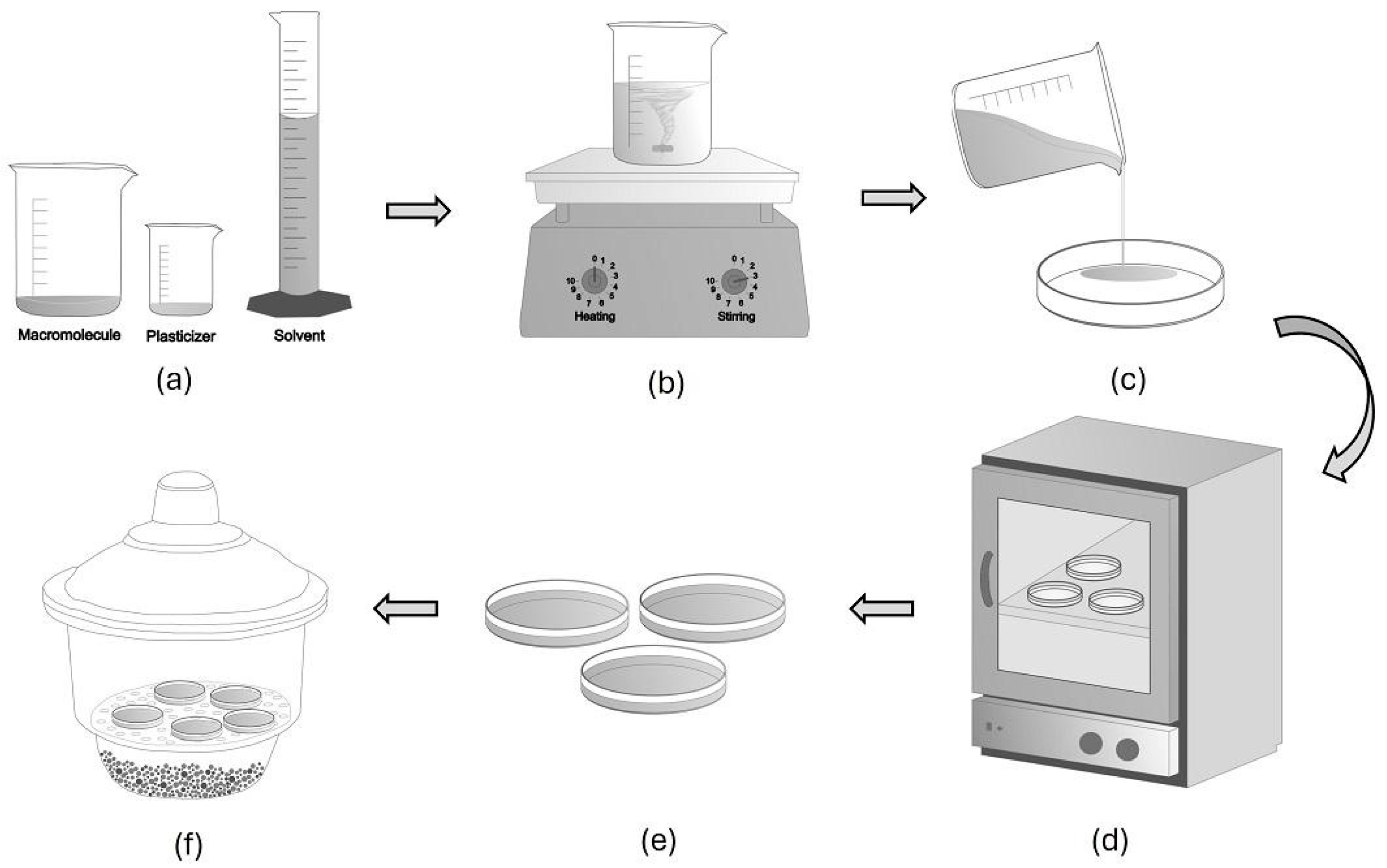

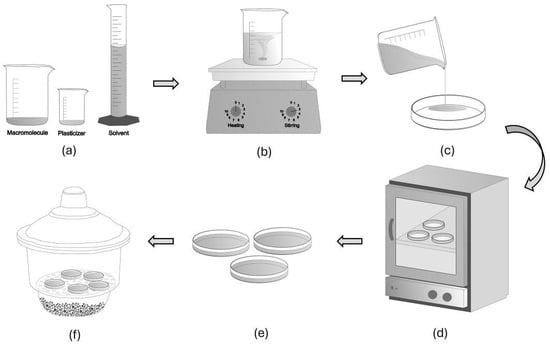

The steps involved in the casting technique are shown in Figure 1. To prepare protein films, the macromolecule (whey protein and derivatives) is first homogenized, and different concentrations of water can be used (Figure 1a). Then, the plasticizer is added to different specifications, according to the type of film that we are seeking to obtain. Then, homogenization occurs under constant stirring [20,46]. Subsequently, the film-forming solution is heated to a given temperature, which can vary between 75 and 90 °C [43,45] (Figure 1b). For the development of active films, after cooling the film-forming solution, bioactive compounds are added. Then, the film-forming solution is transferred to the molds (Figure 1c), which can be acrylic [20] or glass [42] Petri dishes, as well as Teflon plates [46,47].

Figure 1.

Steps involved in the casting technique: (a) homogenization, (b) denaturation, (c) film-forming solution is transferred to the molds, (d) drying, and (e,f) storage under controlled relative humidity.

The molds containing the film-forming solution are taken to ovens with forced air circulation with temperatures that can vary from 25 to 40 °C [25,42], for 12–48 h [20,47] (Figure 1d). Drying is the removal of water from the material by heated air, where there is a difference between the partial water vapor pressure of the film surface and the partial vapor pressure of the drying air. In this way, the moisture contained in the material exerts vapor pressure, so the moisture in the film will evaporate until its water vapor partial pressure is equal to the partial pressure of the environment [48]. After drying, the plates are placed in desiccators with controlled relative humidity (Figure 1e,f) to balance the humidity.

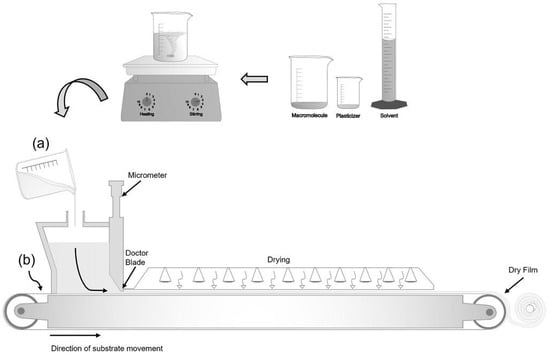

2.2.2. Tape Casting

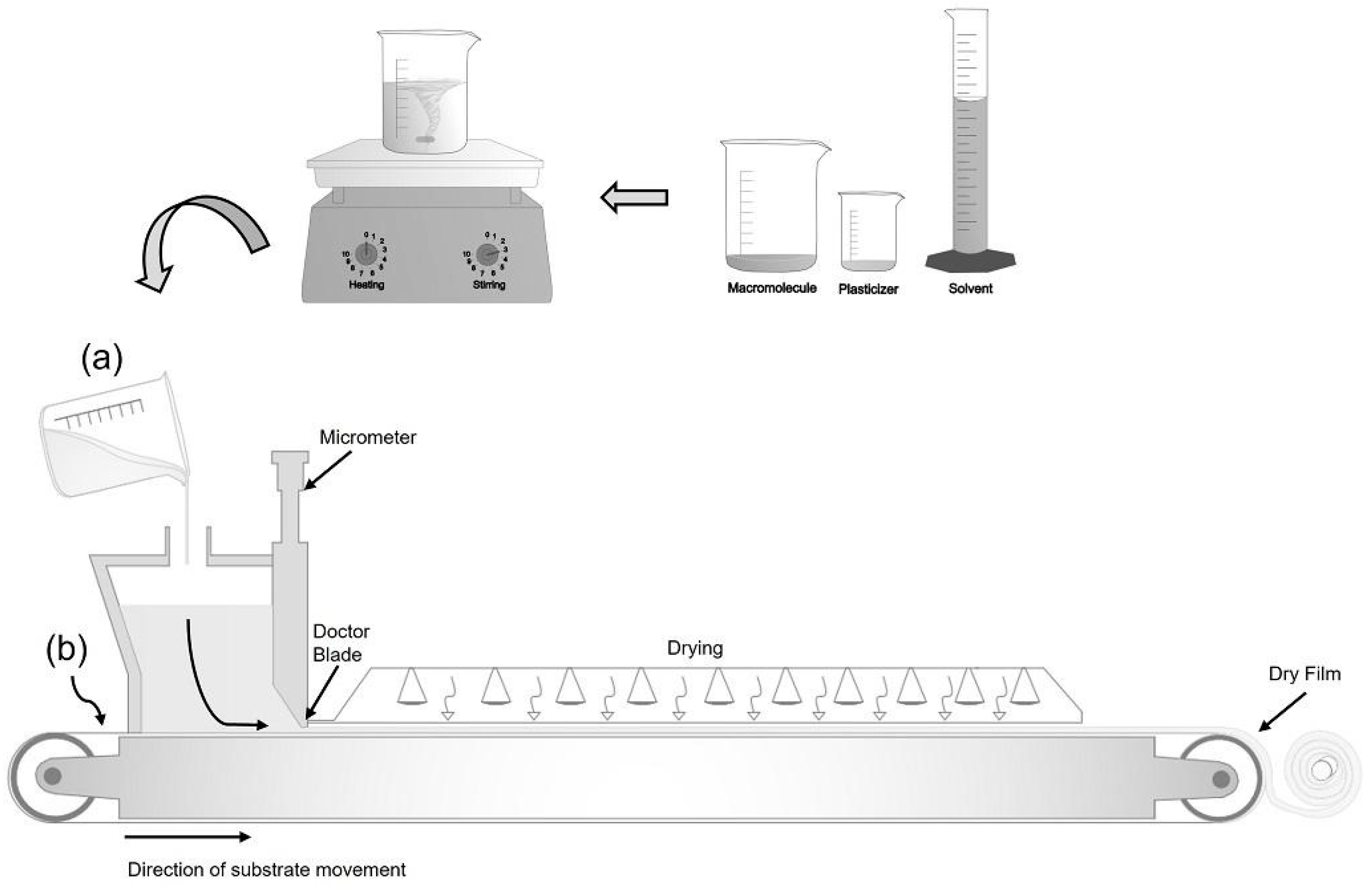

The tape-casting technique, an improvement on the casting method, is underutilized to produce biodegradable films, but it is widespread in the paper and ceramics industries (Figure 2). Tape casting has become a suitable technique for producing biodegradable films on a larger scale, as it allows obtaining films with a larger area and more uniform thickness [49,50].

Figure 2.

Tape-casting technique: (a) preparing the solution and (b) spreading the solution on a continuous conveyor.

The basic principle of the process consists of preparing a film-forming solution containing the polymer (macromolecule), solvent, and plasticizer (Figure 2a). This suspension is spread on a support with a continuous conveyor (Figure 2b), where a leveling blade (Doctor Blade) controls the thickness of the suspension. This spread suspension is dried at a temperature controlled by heat conduction, convection by infrared radiation, or the union of these mechanisms [49,51].

2.3. Properties of Active Whey Protein Films

In recent decades, the packaging and food industries have been joining efforts to reduce synthetic polymers for food packaging and to use biodegradable materials as an environmentally friendly alternative [39]. Protein-based films are a sustainable alternative to conventional petroleum-based materials for food packaging applications. Whey protein film showed flexible, translucent, flavorless, and colorless films with good mechanical properties and are effective gas barriers. This characteristic makes these films an excellent matrix for incorporating bioactive compounds to potentially increase the antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of phenolic compounds [52,53].

Films elaborated from whey proteins with added plasticizers become transparent and flexible and have excellent oxygen barrier properties [31]. However, the different compositions of whey protein isolates or concentrate can have a strong influence on the barrier, mechanical, and thermal properties of the films, as well as the method used in its production and environmental factors [54]. Furthermore, adding plant extracts, such as phenolic compounds, to filmogenic solutions resulted in alteration in barrier, physicochemical, mechanical, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties compared to films elaborated with control film without active components [39,52].

The antioxidant effect is a direct result of the chemical structure of the phenolics present in the whey protein matrix. Phenolic compounds interact with proteins, such whey protein, by some mechanisms, which are essential for developing active films. Phenolic groups act as hydrogen donors that bond with protein carboxyl groups, often initiating the formation of protein–phenolic complexes. Phenolic structures have hydroxyl (-OH) groups that can donate a hydrogen atom to a free radical, stabilizing it and breaking the chain reaction of auto-oxidation [13].

The antimicrobial activity of phenolic compounds can occur due to these interactions with microbial cells, which can lead to growth inhibition or cell death. Furthermore, the phenolic compounds interact with the microbial cell membrane, resulting in structural destabilization. This alteration in membrane permeability results in a loss of cell wall integrity and the leakage of essential intracellular components. The antimicrobial activity of these compounds is because they bind to the hydrophobic regions of extracellular microbial proteins and enzymes, therefore reducing their activity and disrupting the metabolic processes of the microorganism [30,50,52,55].

Nonpolar aromatic rings of phenolics bind to nonpolar protein side chains. Under specific conditions, such as alkaline pH, phenolics oxidize into quinones, forming irreversible cross-links that can improve the thermal stability and structural integrity of films. In packaging, these interactions allow for the controlled release of phenolics, providing sustained antioxidant and antimicrobial protection to food. The resulting cross-linking alters the protein’s secondary and tertiary structures, typically decreasing solubility while enhancing the mechanical properties of the active film [10,15,34,35,55].

2.3.1. Mechanical Properties

Plastic materials are widely used in packaging due to their robust resistance properties to a range of mechanical and environmental factors [29,55]. The mechanical properties of films, including tensile strength (TS), elongation at break (EAB), Young’s modulus of elasticity, and others, are important because they allow packaging to provide adequate mechanical resistance and maintain its integrity during food handling and storage [39]. According to Kontogianni et al. [35] the TS corresponds to the maximum tensile stress that the film can sustain; Young’s modulus indicates the stiffness of the film, while EAB indicates the increase in film length from the initial point to the break point, determining its extensibility [35]. They depend on raw material composition and elaboration conditions [29,39].

Elaboration conditions, the process of obtaining the film and its formulation, such as the concentration of the biopolymer and the plasticizer content, affect the mechanical properties. The lower the plasticizer content used in production, the more brittle the films will be. However, the higher the plasticizer content in the films, the greater the elongation until rupture and the lower the tensile strength [39,42].

Guimarães et al. [25] created films with 10% whey protein concentrate added with 5% glycerol, obtaining a film with 0.6 MPa of TS and 53.8% EAB. Silva et al. [43] evaluated the mechanical properties of films made with 5% whey protein isolate and 2% glycerol, obtaining a tensile strength of 2.18 MPa and an elongation at a break of 11.24%. According to these authors, it is clear how the formulation and plasticizer content can interfere with the mechanical properties of the films: (i) the film with the lowest plasticizer content showed greater rigidity, that is, greater resistance to deformation, while (ii) the film with higher plasticizer content proved to be more elastic, as it presented lower resistance to deformation.

In some studies, it has been shown that nanoparticle incorporation can improve the characteristics of whey protein films. Zinc oxide nanoparticles, when added into whey protein films, can change the mechanical and barrier properties [29,56]. The nanoparticles increase the number of discontinuities and aggregates in the material, which promotes the nucleation and propagation of cracks by creating localized stress concentrations [56].

Many studies have demonstrated an increase in TS and EAB with the addition of natural extracts, such as phenolics [35]. Kontogianni et al. [35] evaluated whey protein films activated by rosemary and sage extracts to preserve soft cheese. They verified that extract does not interfere significantly in the film structure. The presence of rosemary infusion did not significantly influence the mechanical properties of the films and sage infusion reinforced films compared to the control film without phenolic extract. However, the modulus elasticity and TS of aqueous sage extract reinforced films compared to the control film. Furthermore, the EAB diminished with sage extract addition in whey protein films because this reduced the mobility of the chain by stronger interactions of the polyphenolic compounds with the polymer chain. This behavior is attributable to the higher content of rosmarinic acid and flavonoids in sage, as well as the unique contribution of salvianolic acid K, where polyphenols act as cross-linkers. Ampessan et al. [42] showed that most extracts reinforce the film; coconut oil acted as a dual agent, increasing TS and EAB. This suggests that the lipid fraction of certain extracts can provide flexibility that pure phenolic powders or aqueous extracts cannot.

Ju and Song [16] verified that the TS of Red algae (Gloiopeltis furcata) film incorporated with yellow onion peel extract decreases as the concentration of the extract increases. The EAB verified that the film incorporated with yellow peel onion extract had higher values than the control film 27.4%. However, it decreased as the concentration of the extract increased from 0.3% to 1% with 35.7% and 20.5%, respectively. The extract incorporation into film results in modified structural changes in the film through interactions between the polymer and extract molecules, respectively.

According to Chollakup et al. [15] rambutan peel extract (RPE) and cinnamon oil (CO) incorporated in cassava starch (CS) and whey protein isolate blends, in proportion 1:4; m/m, results in increased TS, coincident with reduced EB values and suggesting that the addition of starch in the presence of RPE and CO formed more rigid chain networks. In general, the results show that differences can depend on different interactions between the protein backbone of the WPC-based film and phenolic compounds present in the extracts. Several authors reported the occurrence of intermolecular hydrogen bonding between the N-terminal protein end and the hydroxyl group (-OH) of the aromatic hydrocarbon in edible films containing polyphenols phenolics [20,35,47,56].

2.3.2. Barrier Properties

Barrier properties, such as water vapor permeability (WVP), relative humidity, and oxygen permeability [57], are important parameters in defining the film for many applications. WPFs are hydrophilic in nature and, for this reason, have an affinity for water, which affects their physical and barrier properties. These properties indicate how they will remain intact after contact with water, temperature, and specific time of storage or exposure [58].

Barrier properties, such as permeability to oxygen and carbon dioxide, are important because many foods degrade in the presence of O2. This property is essential to better define the application of films and contribute to food conservation [25,35,57]. WPFs are fragile because of the bonding of proteins through hydrogen and disulfide bonds, which show a hydrophilic nature. The films have greater permeability to water vapor than caseinate-, soy protein-, wheat gluten-, and corn zein-based films [31,35,58].

WVP is evaluated because some applications require insolubility in water to maintain the integrity of the product [58]. During storage, foods are susceptible to chemical and enzymatic reactions due to their water activity, which can harm their nutritional and organoleptic characteristics, in addition to the possible development of spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms [25,35,46].

WPFs showed high water vapor permeability, due to the amount of hydrophilic amino acids in their structure, but low gas permeability [59]. Agudelo-Cuartas et al. [20] prepared films containing 10% whey protein concentrate and 5% glycerol and found that water solubility and WVP were 58.9% and 1.4 × 10−10 gm−1·s−1·Pa−1, respectively. Fernandes et al. [45] produced films of whey protein isolate with 30 g/100 g of glycerol, finding a value of 1.09 g·mm·h−1·m−2·kPa−1.

The addition of phenolic compounds generally shows a reduction in WVP to protect food from moisture. Kontogianni et al. [35] verified that the incorporation of phenolic compounds of rosemary and sage infusions resulted in interactions between them and the group of whey proteins, which decreased water interaction with the polymer chain. It is suggested that the films containing phenolic compounds have hydroxyl groups (OH) and cross-linking between proteins and phenolic compounds, thus lowering WVP. However, Chollakup et al. [15] demonstrated that the incorporation of plant extracts, such as rambutan peel extract (RPE), results in an increase in WVP, highlighting a key structural limitation because phenolic extracts exhibit high hygroscopicity or cause excessive protein network disruption; these factors can supersede the benefits of cross-linking, leading to higher permeability.

2.3.3. Bioactive Properties

Films based on whey protein and derivatives are excellent carriers of additives, such as natural antioxidants, antimicrobials, and flavors [52]. The incorporation of active agents makes the film more efficient, due to the slow migration of the active compound to the food surface; this slow release guarantees action for as long as the product is packaged [60,61]. The choice of active agent depends on the desired antimicrobial and antioxidant activities, the resistance of the microorganism and its growth rate, the physical–chemical characteristics of the food and the active agent, the release mechanism, and the storage conditions, among others [8,15,60,61].

Asdagh and Pirsa [41] studied the effect of adding copper oxide nanoparticles containing coconut essential oil (0–0.8%) and/or paprika extract (0–0.06%) to copper-based whey protein isolate films. The antimicrobial activity against the microorganisms Escherichia coli O157:H7 (Gram-negative) and Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) was significant for the films containing nanoparticles with coconut EO when compared to the films containing only the nanoparticles.

Aziz and Almasi [62] studied the incorporation of thyme extract and nanoliposomes to evaluate the antimicrobial, antioxidant, and release properties in whey-based films. The film incorporated with 15% thyme extract showed the highest free radical scavenging activity and obtained an inhibition zone of 112.25 mm2 for the Gram-negative bacterium E. coli O157:H7 and 167.19 mm2 for the Gram-positive bacterium S. aureus, when compared to the film without an active compound and that with a lower concentrations. The difference in the inhibition zone of the antimicrobial activity of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria occurs due to structural differences in the bacterial membrane, where the cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., S. aureus) is less complex than that of Gram-negative (e.g., E. coli), the latter having greater resistance due to the presence of an external membrane that acts as a permeability barrier, reducing the absorption of bioactive compounds [63,64,65].

Chollakup et al. [15] demonstrated that the incorporation of plant extracts, such as rambutan peel extract (RPE) and cinnamon oil, into CS and whey protein isolate blend films significantly enhanced their antibacterial activity against Bacillus cereus, E. coli, and S. aureus. These films exerted an inhibitory effect through a mechanism of action that included the degradation of the bacterial cell wall, the leakage of cytoplasmic cell contents, and the disruption of both mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity and the plasma membrane, ultimately leading to cell death.

Oliveira et al. [59] produced whey-based films incorporated with oregano essential oil (EO) (0.5–1.5%) and evaluated the antimicrobial activity against Penicillium commune. Films with a concentration of 1.0% and 1.5% showed good antimicrobial activity when compared to films without active compounds. The antimicrobial activity of EO is the result of their hydrophobic character that acts by disrupting the microbial membrane, thus compromising the functions of the microbial cell and disrupting the structure, losing its impermeability.

Çakmak et al. [66] studied the antimicrobial activity of films based on whey protein isolate incorporated with lemon and bergamot EOs and their antimicrobial activity against E. coli, S. aureus, and Aspergillus niger. The authors observed that the antimicrobial activity of bergamot EO was superior to that of lemon. Sheerzad et al. [67] verified that a whey protein isolate incorporating cinnamon essential oil (CEO) significantly improved its antibacterial activity, effectively retarding the proliferation of mesophilic bacteria, psychrotrophic bacteria, Pseudomonas spp., Enterobacteriaceae, Lactic acid bacteria, S. aureus, mold, and yeast.

Bioactive Properties of Phenolic Compounds

Bioactive compounds offer a promising natural alternative to artificial food preservatives, meeting consumer demand for sustainable solutions that ensure food quality and safety [13]. Most natural antioxidants are phenolic compounds and can be found in fruits, vegetables, spices, and aromatic plants [15,35]. Phenolic compounds of plant origin can be divided into four groups: phenolic acids, phenolic diterpenes, flavonoids, and volatile oils. The arrangement of functional groups in the nuclear structure is preponderant for antioxidant activity and it is responsible for several properties of aromatic plants, such as antioxidant and antimicrobial capacities [13].

Many vegetal have been studied in recent years for the extraction of phenolic compounds, such as date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) [68], feijoa (Acca sellowiana), cherry of the Rio Grande (Eugenia involucrata) [69], juçara palm (Euterpe edulis), yellow and red araçá (Psidium cattleianum), butiá (Butia capitata), guabiroba (Campomanesia xanthocarpa), jabuticaba (Plinia cauliflora), pitanga (Eugenia uniflora) [70], and peanut skin (Arachis hypogaea L.) [71], due to their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties.

Industrial by-products are an important source of bioactive compounds, such as peanut skin, which is rich in phenolic compounds with bioactive properties, and has low economic value [71]. By-products from fruits are natural sources of phenolic compounds, which exert important antioxidant properties primarily associated with the presence of hydroxyl groups in their molecular structure [13].

Peanut skin represents around 3.5 to 4.5% of the grain mass and is underutilized, with only a fraction destined to produce animal feed [16,72]. However, it is a source of phenolic acids, such as proanthocyanidins, flavonoids, and resveratrol [13,72,73]. The predominant phenolic compounds are proanthocyanidins, which can represent 17% of the skin mass and are present in a higher concentration of procyanidin trimers and tetramers (type A) resveratrol [72,73]. Meng et al. [74] evaluated the antioxidant ability of peanut shell and skin extracts and their effects on the physical and structure properties of starch–chitosan film, and verified an influence on these properties.

Due to their promising antioxidant and health-promoting qualities, alongside favorable consumer acceptance, phenolic compounds are emerging as an effective alternative to synthetic antioxidants [11,13]. The antioxidant power of phenolic compounds is derived from their redox (oxidation-reduction) properties, which lead to the adsorption and neutralization of free radicals, suppression of oxygen molecules, or decomposition of peroxides [11,12,13,73].

The antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds depends on the hydroxyl group, which is responsible for scavenging free radicals. The greater the degree of hydroxylation, the greater its antioxidant activity, and this activity will occur due to the donation of hydrogen to free radicals. The affinity of phenolic compounds with proteins is related to the position of the hydroxyl group, methylation of -OH groups, or replacement of these by methyl groups [11,12,13].

Natural antimicrobial substances, such as phenolic compounds, play a key role here, as they effectively prolong food shelf life by suppressing or destroying microbial development [13,75]. Many microorganisms, including fungi and bacteria, can cause a series of health problems in humans. In food, fungi can cause changes in sensory properties, resulting in loss of product quality. Fungal contamination in food can occur through environmental contamination by fungal spores at different stages of the food production chain [76,77].

Fungal infections, which occur in various parts of the human and animal body, are caused by pathogenic fungi and many antifungals and preservatives can be used as a way of inhibiting or eliminating them. Diseases caused by fungi are treated by many types of antifungals, such as polyenes and azoles, among others. The type of antifungals used depends on the targeted pathogen [76,77,78]. The antifungal agents generally used are the disruptors that target fungal ergosterol biosynthesis, β-glucan synthesis, fungal membranes, or nucleic acid synthesis, among others [76]. Phenolic compounds act as antifungals, as they inhibit the multiplication of fungi by preventing the construction of components (i) of the cell wall, such as chitin and glucan, or (ii) the cell membrane [77,79].

Antimicrobial activity of phenolic compounds occurs because of the interaction with proteins in the bacterial cell wall, resulting in cell lysis, as well as their ability to bind to hydrophobic regions of extracellular microbial proteins. Furthermore, they can cause a change in the protein structure and denaturation makes the protein non-functional, which results in cellular death. However, the volatility and stability of the phenolic compounds still limit their industrial application. Alternatives, such as nanoencapsulation and incorporation into edible films and coatings, can overcome these limitations, enabling the broader use of these compounds in food preservation activity [13,79,80]. Films and coatings are particularly advantageous for controlling microbial food contamination and oxidation reactions, as they can act as compound carriers and release active compounds into foods. Spoilage occurs on the food surface, where films can be used to inhibit microbial growth and spoilage reactions [13,80,81].

3. Active Film Application

Active films interact with food through the release or absorption of unwanted substances, without altering the sensory and safety characteristics, maintaining the expected quality of the food and prolonging its shelf life [52,82]. This type of packaging aims to delay, inhibit, or reduce the multiplication of pathogenic and spoilage microorganisms in food. Its interaction with food is defined as an exchange of mass and energy between the product, packaging, and environment and it is classified as migration, permeability, and sorption [83]. Several formulations of bioactive films based on whey proteins incorporated with active compounds have been studied and evaluated for their active potential for applications aimed at extending the shelf life of foods (Table 2).

The active potential of films developed with whey protein as a matrix has been proven, highlighting their antioxidant and antimicrobial capacity. However, it is important to emphasize the need to apply such films in real food systems to prove their effectiveness in reducing food spoilage reactions and, consequently, increasing their shelf life [60,61,84]. In the literature, there are reports of whey protein films incorporated with oils and plant extracts, whose active mechanisms are due to the presence of phenolic compounds. Among the applications are dairy products, mainly cheeses, meat products, fruits, and seafood, among others [8,15,67,85].

The interaction of active films with the food is determined by diffusion in the matrix and in the food of the component that migrates, in addition to the balance (partition coefficient) and the geometric dimensions. The amount of migrated compound is controlled by the diffusion and partition coefficients, which, in turn, are directly linked to the food composition, the film hydration capacity, the molecules mobility of the active compound, and the film thickness [8,15,60,61,65].

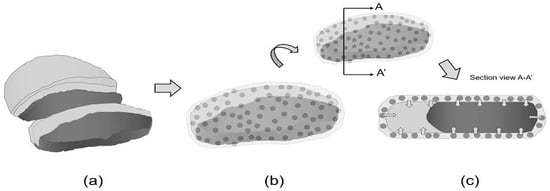

Active films release these active compounds progressively into the food, interacting and inhibiting degrading agents. These compounds can be incorporated into the packaging matrix, and their gradual release occurs through contact between the film and the food, maintaining the concentration of the active ingredient at desirable levels during storage time [52,86].

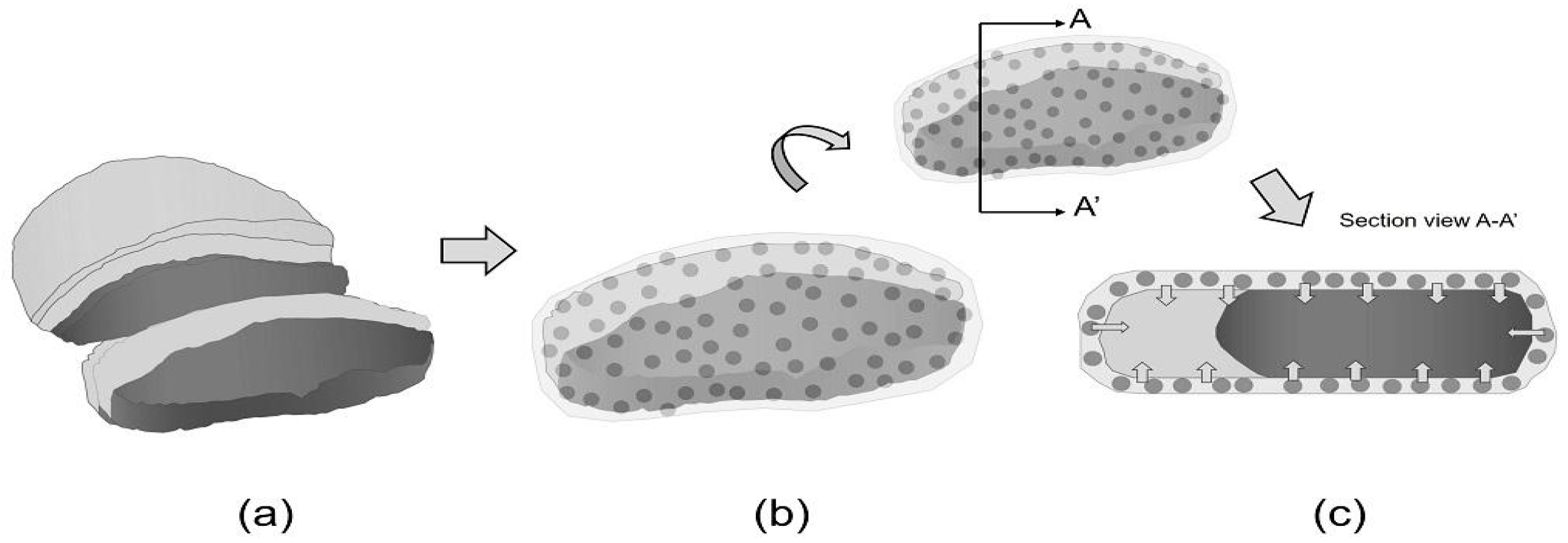

Figure 3 shows the dynamic interaction between active packaging and food, specifically showcasing the gradual migration of active compounds from the film into the food. Figure 3a shows an uncoated meat where the meat is directly exposed to external environmental factors, such as oxygen and microorganisms, leading to rapid degradation, spoilage, and a shorter shelf life. Degrading agents can freely interact with the food surface, accelerating oxidative processes and microbial growth [86,87].

Figure 3.

Bioactive film packaging: (a) uncoated meat, (b) meat coated with bioactive film and (c) migration of active compounds from the film to food surface.

Table 2.

Active films of whey protein.

Table 2.

Active films of whey protein.

| Matrix | Phenolic Compound (PC) | Concentration of PC (%) | Purpose of Adding of PC | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WPC | F. vesiculosus L. (seaweed) | 1 | Lipid oxidation in chicken breast | [82] |

| WPI | Thyme, nanoliposomes containing thyme extract | 5–15 | Antibacterial activity evaluated against Staphylococcus. aureus and Escherichia. coli | [62] |

| WPI+CS | Cinnamon oil and rambutan peel | 0.04 | Antibacterial activity of Bacillus cereus, S. aureus and E. coli | [15] |

| WPI | Oregano essencial oil | 0.5–1.5 | Antimicrobial activity tested against a lyophilized culture of Penicillium commune | [59] |

| WPI | CuO nanoparticles containing coconut and paprika EO | 0–0.8 0–0.06 | Antimicrobial activity tested against S. aureus; E. coli and Aspergillus niger | [41] |

| WPI | Lemon and bergamot essencial oil | 1.4–5.6 | Antimicrobial activity against E. coli, S. aureus and A. niger | [66] |

| WPI+FU | extract of yerba mate and white tea | 15 | Influence on the quality and shelf life of fresh curd cheese | [88] |

| WPC | Cinnamon and rosemary EO | 1–5 | Lipid oxidation in salami | [47] |

| WPC | Rosemary extract | 1 | Antimicrobial activity tested against Listeria monocytogenes and S. aureus | [34] |

| WPI | Ginger and rosemary EO | 0.5–1 | Microbiological analysis: Pseudomonas spp., Brochothrix thermosphacta, lactic acid bacteria and yeast | [26] |

WPC: Whey protein concentrate; WPI: Whey protein isolate; CS: Cassava starch; FU: furcellaria; EO: essencial oil.

Figure 3b shows meat coated with bioactive film, incorporated with active compounds, such as antimicrobials or antioxidants, in the matrix. This direct contact allows for the initial interaction between the film and the food surface. Figure 3c shows the migration of active compounds from the film to food surface. These compounds gradually diffuse from the film matrix to the food surface and, over time, can penetrate deeper into the food. These compounds interact with and inhibit degrading agents, such as spoilage bacteria or free radicals. They effectively prolong the meat’s freshness, inhibit microbial growth, and prevent oxidative deterioration, extending its overall shelf life and enhancing safety.

Nourmohammadi et al. [83] developed whey and nano clay bio-compounds incorporated with Thymus fedtschenkoi Ronniger EO and resveratrol and evaluated the cheeses for lipid oxidation, microbiology, and sensory properties. It is important to highlight that the main substances responsible for the active potential of this EO are thymol and carvacrol, two phenolic compounds.

In the study by Pluta-Kubica et al. [88], a positive effect of phenolic compounds from yerba mate and white tea incorporated into furcellaran films and whey proteins on cheese conservation was observed. In this study, the authors highlighted that the organoleptic quality of the cheese packaged with active films was superior, compared to samples packaged in a commercial polymer (PEBD).

Seydim, Sarikus-Tutal, and Sogut [35] incorporated EOs from plants (oregano and garlic) into whey protein films and applied them to cheese. They observed a significant reduction in the growth of E. coli 0157:H7 (1.48 log reduction) and S. aureus (2.15 log reduction) in samples containing layers of active films between cheese slices compared to control samples. The active films prevented the development of spoilage and pathogenic bacteria in cheese stored at 4 °C for 60 days [32]. They also contribute to conservation as they protect the product from oxygen in the external environment of the packaging.

In meat products, active whey protein films containing Origanum virens EO were applied to Portuguese sausages during their industrial production. Color maintenance, decreased lipid oxidation, inhibition of microbial load, and sensory acceptance were observed, increasing shelf life between 15 and 20 days [89]. In minced lamb meat, ginger and rosemary EOs helped preserve it when incorporated into whey protein films. Among the results, an improvement in microbiological quality and a decrease in oxidation were observed [26].

In salami, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity was obtained with the use of blends of cassava starch and whey proteins incorporated with rambutan bark extract and cinnamon oil [15]. Also in salami, Ribeiro-Santos et al. [47] observed that the addition of cinnamon and rosemary EOs to whey protein concentrate films was effective against lipid oxidation. The films did not show deterioration during the 180 days of storage.

In products other than cheese and meat, films of tamarind starch and whey concentrate were incorporated with thyme EO and applied to tomatoes. The films reduced the respiration rate and delayed the ripening of tomatoes, increasing their shelf life by up to 14 days. Furthermore, due to the presence of phenolic compounds, such as thymol and carvacrol, antioxidant activity and antimicrobial activity against E. coli and S. aureus were obtained [90]. Whey proteins have also been used together with jujube polysaccharides and cellulose nanocrystals to increase banana shelf life [27]. In sunflower seeds, whey protein concentrate coatings contribute to increasing the oxidative stability and color of the seeds [91].

These studies demonstrate the potential of active films of whey protein concentrates or isolates and other sources, especially incorporated with phenolic compounds. A range of food products, from cheeses and meats to fruits, vegetables, and even seeds, were studied to demonstrate their ability to extend shelf life by mitigating lipid oxidation, inhibiting microbial growth, and maintaining desirable sensory attributes like color and flavor. Furthermore, the synergistic effect of whey proteins as a matrix for the sustained release of phenolic compounds, such as thymol, carvacrol, and those derived from various plant extracts, underpins their remarkable efficiency. The consumer demand for natural, safe, and sustainable food solutions continues to grow. Whey protein-based active films, particularly those leveraging the power of phenolic compounds, stand out as a highly promising and versatile technology for the future of food preservation.

Future Perspectives

Recent studies demonstrate the promising antioxidant and antimicrobial capacities of whey protein-based films incorporated with phenolic compounds. However, these films can present some limitations, such as the high volatility and sensitivity of phenolic compounds to industrial processing. Some results have shown that the presence of phenolic compounds improves or decreases some properties, such as mechanical and barrier properties, which depend on the concentration of the phenolic compound, the WPI, or WPC concentration. Thus, studies are needed to determine the mechanical, barrier, and functional properties of other types of whey protein-based films, such as flavor and odor absorption/release film formulation, which can be studied to improve film characteristics [10,15,59,66].

Edible films and coatings can be categorized as food contact materials, food additives, or even food products. There is different legislation, such as Regulation (EC) 1333/2008 for additives and Regulation (EC) 1935/2004 for materials in contact with food, which require they be produced under Good Manufacturing Practices to ensure they do not threaten human health or unacceptably change food composition. Furthermore, accurate labeling regarding nutritional information and allergens is important. The EU specifies limits for plastic packaging in EC 10/2011; many protein-based ingredients are not yet on that list, meaning regulatory compliance currently requires individual evaluation based on specific formulations and applications [91,92].

4. Conclusions

Biodegradable polymers, such as whey proteins, are a sustainable alternative to synthetic plastics. Their ability to form transparent and odorless films makes them ideal for packaging. Phenolic compounds can be incorporated into these films to create active films to enhance their functionality. This addition results in packaging with antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. The elaboration process involves a casting technique, where a homogenized mixture of the polymer matrix and a plasticizer is dried. These active films not only protect food from physical damage, moisture, and oxidation but also allow for the gradual release of bioactive compounds. Consequently, whey protein films with phenolic compounds show great potential for extending food shelf life, ensuring greater safety and quality, and simultaneously reducing food waste and environmental impact. The main challenges include maintaining the stability of phenolic compounds during industrial processing and ensuring that the sensory changes in food are acceptable to consumers.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, grant number 409603/2021-0.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico–CNPQ.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hidayati, S.; Maulidia, U.; Saytajaya, W.; Hadi, S. Effect of glycerol concentration and carboxy methyl cellulose on biodegradable film characteristics of seaweed waste. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jylhä, H.; Johansson, A.; Sorvari, J.; Salminen, J. A novel method of accounting for plastic packaging waste. Waste Manag. 2025, 196, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, N.K.; Alnemr, T.; Ali, S. Development of low-cost biodegradable films from corn starch and date palm pits (Phoenix dactylifera). Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestido-Cardama, A.; Barbosa-Pereira, L.; Sendón, R.; Bustos, J.; Losada, P.P.; de Quirós, A.R.B. Chemical safety and risk assessment of bio-based and/or biodegradable polymers for food contact: A review. Food Res. Int. 2025, 202, 115737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lens-Pechakova, L. Recent studies on enzyme-catalysed recycling and biodegradation of synthetic polymers. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2021, 4, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, R.K.; Chakraborty, S.K. Plastic waste management during and post Covid19 pandemic: Challenges and strategies towards circular economy. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Kolodjski, S.; Lewis, G.; Onan, G.; Kim, Y. Physical and Functional Characterization of Whey Protein-Lignin Biocomposite Films for Food Packaging Applications. Future Foods 2025, 11, 100554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Lyu, J.S.; Han, J. Nanoencapsulation and crosslinking of trans-ferulic acid in whey protein isolate films: A comparative study on release profile and antioxidant properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 303, 140737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorofte, A.L.; Bleoanca, I.; Bucur, F.I.; Mustatea, G.; Borda, D.; Stan, F.; Fetecau, C. Biocomposite Active Whey Protein Films with Thyme Reinforced by Electrospun Polylactic Acid Fiber Mat. Foods 2025, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoolklang, A.; Hemung, B.-O.; Jirukkakul, N. Characteristics of gelatin/sarcoplasmic protein films supplemented with red water lily petal extract. LWT 2025, 228, 118136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xia, P. Health effects of synthetic additives and the substitution potential of plant-based additives. Food Res. Int. 2024, 197, 115177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiorcea-Paquim, A.; Enache, T.A.; De Souza Gil, E.; Oliveira-Brett, A.M. Natural phenolic antioxidants electrochemistry: Towards a new food science methodology. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 1680–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, I.; Santos-Buelga, C.; Aquino, Y.; Barros, L.; Heleno, S.A. New frontiers in the exploration of phenolic compounds and other bioactives as natural preservatives. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alara, O.R.; Abdurahman, N.H.; Ukaegbu, C.I. Extraction of phenolic compounds: A review. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chollakup, R.; Pongburoos, S.; Boonsong, W.; Khanoonkon, N.; Kongsin, K.; Sothornvit, R.; Sukyai, P.; Sukatta, U.; Harnkarnsujarit, N. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of cassava starch and whey protein blend films containing rambutan peel extract and cinnamon oil for active packaging. LWT 2020, 130, 109573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, A.; Song, K.B. Active biodegradable films based on water soluble polysaccharides from white jelly mushroom (Tremella fuciformis) containing roasted peanut skin extract. LWT 2020, 126, 109293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falguera, V.; Quintero, J.P.; Jiménez, A.; Muñoz, J.A.; Ibarz, A. Edible films and coatings: Structures, active functions and trends in their use. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, E.M.N.; Gruter, G.-J.M.; Parsons, J.R.; Tietema, A. Comparison of the aerobic biodegradation of biopolymers and the corresponding bioplastics: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 753, 141953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, X.; Wang, Z.; Chu, X.; He, Z.; Zeng, M.; Chen, Q.; Chen, J. A high moisture extrusion technique for improved properties in soy protein isolate films: Impact of branch structure of polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 318, 144892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo-Cuartas, C.; Granda-Restrepo, D.; Sobral, P.J.A.; Hernandez, H.; Castro, W. Characterization of whey protein-based films incorporated with natamycin and nanoemulsion of α-tocopherol. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, S.; Wang, L.; Rhim, J.-W. Effect of melanin nanoparticles on the mechanical, water vapor barrier, and antioxidant properties of gelatin-based films for food packaging application. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 21, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekhit, M.; Tehrany, E.A.; Kahn, C.J.F.; Cleymand, F.; Fleutot, S.; Desobry, S.; Sánchez-González, L. Bioactive films containing alginate-pectin composite microbeads with Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis: Physicochemical characterization and antilisterial activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xia, R.; Yuan, T.; Sun, R. Use of xylooligosaccharides (XOS) in hemicelluloses/chitosan-based films reinforced by cellulose nanofiber: Effect on physicochemical properties. Food Chem. 2019, 298, 125041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalermthai, B.; Chan, W.Y.; Bastidas-Oyanedel, J.-R.; Taher, H.; Olsen, B.D.; Schmidt, J.E. Preparation and characterization of whey protein-based polymers produced from residual dairy streams. Polymers 2019, 11, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, A.C.S.E.; Ramos, Ó.; Cerqueira, M.; Venâncio, A.; Abrunhosa, L. Active whey protein edible films and coatings incorporating Lactobacillus buchneri for Penicillium nordicum control in cheese. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2020, 13, 1074–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsironi, M.; Kosna, I.S.; Badeka, A.V. The Effect of Whey Protein Films with Ginger and Rosemary Essential Oils on Microbiological Quality and Physicochemical Properties of Minced Lamb Meat. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibzahedi, S.M.T.; Ahmadigol, A.; Khubber, S.; Altintas, Z. Whey protein isolate/jujube polysaccharide-based edible nanocomposite films reinforced with starch nanocrystals for the shelf-life extension of banana: Optimization and characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, H. Biodegradation of whey protein-based edible films. J. Environ. Polym. Degrad. 2000, 8, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Mujahid, M.; Shahzad, S.; Rauf, Z.; Hussain, A.; Ayyash, M.; Ullah, A. Exploring protein-based films and coatings for active food packaging applications: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 320, 146070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseto, M.; Rigueto, C.V.T.; Alessandretti, I.; de Oliveira, R.; Wohlmuth, D.A.R.; Loss, R.A.; Dettmer, A.; Richards, N.S.P.D.S. Whey-based polymeric films for food packaging applications: A review of recent trends. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2023, 103, 3217–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, H.; Bian, H.; Pan, Y.; Sun, J.; Han, W. Application of protein-based films and coatings for food packaging: A review. Polymers 2019, 11, 2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seydim, A.C.; Sarikus-Tutal, G.; Sogut, E. Effect of whey protein edible films containing plant essential oils on microbial inactivation of sliced Kasar cheese. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 26, 1005672020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulou, E.; Maurizzi, E.; Bigi, F.; Quartieri, A.; Pulvirenti, A.; Tsironi, T. Comparative effect of different plasticizers on physicochemical properties of hydroxypropyl methyl cellulose (HPMC) based films appropriate for gilthead seabream packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2025, 10, 100839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.A.; Santos, R.R.; Guerra, M.; Silva, A.S. Evaluation of the oxidative status of salami packaged with an active whey protein film. Foods 2019, 8, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontogianni, V.G.; Kasapidou, E.; Mitlianga, P.; Mataragas, M.; Pappa, E.; Kondyli, E.; Bosnea, L. Production, characteristics and application of whey protein films activated with rosemary and sage extract in preserving soft cheese. LWT 2022, 155, 112996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, M.; Ramchandran, L.; Donkor, O.N.; Vasiljevic, T. Denaturation of whey proteins as a function of heat, pH and protein concentration. Int. Dairy J. 2013, 31, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, S.; Yoo, J.; Yun, J.; Kang, H.B.; Seol, K.-H.; Kim, H.-W.; Ham, J.-S. Application of whey protein-based edible films and coatings in food industries: An updated overview. Coatings 2021, 11, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuchell, Y.M.; Krochta, J.M. Enzymatic Treatments and Thermal Effects on Edible Soy Protein Films. J. Food Sci. 1994, 59, 1332–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wihodo, M.; Moraru, C.I. Physical and chemical methods used to enhance the structure and mechanical properties of protein films: A review. J. Food Eng. 2013, 114, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, L.; McClements, D.J. Current insights into protein solubility: A review of its importance for alternative proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 137, 108416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asdagh, A.; Pirsa, S. Bacterial and oxidative control of local butter with smart/active film based on pectin/nanoclay/Carum copticum essential oils/β-carotene. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ampessan, G.A.; Giarola, D.A. Study of mechanical properties of whey protein films modified with coconut oil. Rev. Ciências Exatas E Nat. 2016, 18, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.S.; Fonseca, T.M.R.; Amada, L.R.; Mauro, M.A. Physicochemical and microstructural properties of whey protein isolate-based films with addition of pectin. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2018, 16, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudali, L.; Belouaggadia, N.; Nagoor, B.S.; Zamma, A.; Elfarissi, L. Innovative whey protein isolate-based biopolymer film with glycerol for sustainable food packaging applications. Hybrid Adv. 2025, 11, 100519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, L.M.; Guimarães, J.T.; Silva, R.C.; Rocha, R.S.; Coutinho, N.M.; Balthazar, C.F.; Calvalcanti, R.N.; Piler, C.W.; Pimentel, T.C.; Neto, R.P.C.; et al. Whey protein films added with galactooligosaccharide and xylooligosaccharide. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 104, 105755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, F.V.R.; Andrade, M.A.; Silva, A.S.; Vaz, M.F.; Vilarinho, F. The contribution of a whey protein film incorporated with green tea extract to minimize the lipid oxidation of salmon (Salmo salar L.). Foods 2019, 8, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro-Santos, R.; de Melo, N.R.; Andrade, M.; Azevedo, G.; Machado, A.V.; Carvalho-Costa, D.; Sanches-Silva, A. Whey protein active films incorporated with a blend of essential oils: Characterization and effectiveness. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2017, 31, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foust, A.S.; Wenzel, L.A.; Clump, C.W.; Maus, L.; Andersen, L.B. Principles of Unit Operations, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, C.M.; de Moraes, J.O.; Vicente, A.R.; Laurindo, J.B.; Mauri, A.N. Scale-up of the production of soy (Glycine max L.) protein films using tape casting: Formulation of film-forming suspension and drying conditions. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 66, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parada-Quinayá, C.; Garces-Porras, K.; Flores, E. Development of biobased films incorporated with an antimicrobial agent and reinforced with Stipa obtusa cellulose microfibers, via tape casting. Results Mater. 2024, 24, 100637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moraes, J.O.; Laurindo, J.B. Properties of starch–cellulose fiber films produced by tape casting coupled with infrared radiation. Dry. Technol. 2018, 36, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, V.M.; Dias, M.V.; Elias, H.H.d.S.; Fukushima, K.L.; Silva, E.K.; Carneiro, J.d.D.S.; Soares, N.d.F.F.; Borges, S.V. Effect of whey protein isolate films incorporated with montmorillonite and citric acid on the preservation of fresh-cut apples. Food Res. Int. 2018, 107, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Brooks, M.S.L. Enhancing Bio-based Polysaccharide/Protein Film Properties with Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADESs) and NADES-based Bioactive Extracts–A Review. Future Foods 2025, 11, 100590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Ó.L.; Reinas, I.; Silva, S.I.; Fernandes, J.C.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Pereira, R.N.; Vicente, A.A.; Poças, M.F.; Pintado, M.E.; Malcata, F.X. Effect of whey protein purity and glycerol content upon physical properties of edible films manufactured therefrom. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 30, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Gao, R.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, Q. Applications of biodegradable materials in food packaging: A review. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 91, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, P.; Ronchetti, S.; Mollea, C.; Sangermano, M.; Onida, B.; Bosco, F. Whey proteins–zinc oxide bionanocomposite as antibacterial films. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zink, J.; Wyrobnik, T.; Prinz, T.; Schmid, M. Physical, chemical and biochemical modifications of protein-based films and coatings: An extensive review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Isquierdo, V.M.; Krochta, J.M. Thermoplastic Processing of Proteins for Film Formation—A Review. J. Food Sci. 2008, 73, R30–R39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, S.P.L.F.; Bertan, L.C.; de Rensis, C.M.V.B.; Bilck, A.P.; Vianna, P.C.B. Whey protein-based films incorporated with oregano essential oil. Polímeros 2017, 27, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquavia, M.A.; Benitez, J.J.; Guzman-Puyol, S.; Porras-Vazquez, J.M.; Hierrezuelo, J.; Ruiz, M.G.; Romero, D.; Di Capua, A.; Bochicchio, R.; Laurenza, S.; et al. Enhanced extraction of bioactive compounds from tea waste for sustainable polylactide-based bioplastic applications in active food packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 46, 101410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, J.; Lv, Y.; Du, J.; Rojas, O.J.; Wang, H. Controlled release of active food packaging by nanocarriers: Design, mechanism, models and applications. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2025, 49, 101524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.G.-G.; Almasi, H. Physical characteristics, release properties, and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of whey protein isolate films incorporated with thyme (Thymus vulgaris L.) extract-loaded nanoliposomes. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2018, 11, 1552–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wu, F.; Xiang, M.; Zhang, W.; Wu, Q.; Lu, Y.; Fu, J.; Chen, M.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; et al. Encapsulation of tea polyphenols into high amylose corn starch composite nanofibrous film for active antimicrobial packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 245, 125245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, S.; Zeynali, F.; Almasi, H. Antimicrobial and antioxidant efficiency of nanoemulsion-based edible coating containing ginger (Zingiber officinale) essential oil and its effect on safety and quality attributes of chicken breast fillets. Food Control 2012, 84, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, C.; Ma, W.; He, R.; Rong, Y.; Sarker, S.; Liu, Q.; Tian, F. A novel active packaging film containing citronella oil: Preparation, characterization, antimicrobial activity and application in grape preservation. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 40, 101168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, H.; Özselek, Y.; Turan, O.Y.; Firatligil, E.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F. Whey protein isolate edible films incorporated with essential oils: Antimicrobial activity and barrier properties. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2020, 179, 109285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheerzad, S.; Khorrami, R.; Khanjari, A.; Gandomi, H.; Basti, A.A.; Khansavar, F. Improving chicken meat shelf-life: Coating with whey protein isolate, nanochitosan, bacterial nanocellulose, and cinnamon essential oil. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 197, 115912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.K.B.D.; Almeida, F.D.A.C.; Gomes, J.P.; Lima, A.R.N.; Melo Neto, I.D.B.; Silva Júnior, P.R.D.; Ramos, K.R.D.L.P. Physical chemical composition and bioactive compounds of aqueous extract of peanuts without skin and enriched with peanut skin. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2021, 24, e2020166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlFaris, N.A.; AlTamimi, J.Z.; AlGhamdi, F.A.; Albaridi, N.A.; Alzaheb, R.A.; Aljabryn, D.H.; Aljahani, A.H.; Almousa, L.A. Total phenolic content in ripe date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 3566–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Schmidt, H.; Rockett, F.C.; Klen, A.V.B.; Schmidt, L.; Rodrigues, E.; Tischer, B.; Augusti, P.R.; de Oliveira, V.R.; da Silva, V.L.; Flores, S.H.; et al. New insights into the phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of feijoa and cherry fruits cultivated in Brazil. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, R.A.; Sousa, H.M.S.; Alves, L.R.P.; Martins, G.A.d.S. Emerging trends in the valorization of Brazilian native fruits and nuts: Innovative extraction technologies and green solvents for the recovery of lipids and bioactive compounds. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 164, 105238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, M.P.; Monaco-Lourenco, C.A.; Carvalho, R.A. Characterization of oral disintegrating film of peanut skin extract—Potential route for buccal delivery of phenolic compounds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 97, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, J.; Du, F. Potential use of peanut by-products in food processing: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 49, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Shi, J.; Zhang, X.; Lian, H.; Wang, Q.; Peng, Y. Effects of peanut shell and skin extracts on the antioxidant ability, physical and structure properties of starch-chitosan active packaging films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 152, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Goda, A.A.; Salem, S.H.; Deabes, M.M.; Ibrahim, M.I.M.; Naguib, K.; Mohamed, S.R. valuation of some artificial food preservatives and natural plant extracts as antimicrobial agents for safety. Discov. Food 2024, 4, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armengol, E.S.; Harmenci, M.; Laffeur, F. Current strategies to determine antifungal and antimicrobial activity of natural compounds. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 252, 126867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ-Ribeiro, A.; Graça, C.D.S.; Kupski, L.; Badiale-Furlong, E.; de Souza-Soares, L.A. Cytotoxicity, antifungal and anti mycotoxins effects of phenolic compounds from fermented rice bran and Spirulina sp. Process Biochem. 2019, 80, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campoy, S.; Adrio, J.L. Antifungals. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 133, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabka, M.; Pavela, R. Antifungal efficacy of some natural phenolic compounds against significant pathogenic and toxinogenic filamentous fungi. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, S.; Jia, W.; Guo, T.; Wang, F.; Li, J.; Yao, Z. Natural antimicrobials from plants: Recent advances and prospects. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanim, A.; Fazita, M.R.N.; Ramle, S.F.M.; Aziz, A.A.; Abdullah, C.K.; Rashedi, A.; Haafiz, M.K.M. Physical, thermal, mechanical, antimicrobial and physicochemical properties of starch based film containing aloe vera: A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 1572–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.A.; Barbosa, C.H.; Souza, V.G.L.; Coelhoso, I.M.; Reboleira, J.; Bernardino, S.; Ganhão, R.; Mendes, S.; Fernando, A.L.; Vilarinho, F.; et al. Novel active food packaging films based on whey protein incorporated with seaweed extract: Development, characterization, and application in fresh poultry meat. Coatings 2021, 11, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourmohammadi, A.; Hassanzadazar, H.; Aminzare, M.; Hashemi, M. The effects of whey protein/nanoclay biocomposite containing Thymus fedtschenkoi Ronniger essential oil and resveratrol on the shelf life of liqvan cheese during refrigerated storage. LWT 2023, 187, 115175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, T.E.B.; de Oliveira, Y.P.; de Carvalho, L.B.A.; Santos, J.A.B.D.; Lima, M.D.S.; Fernandes, R.; de Assis, C.F.; Passos, T.S. Nanoparticles based on whey and soy proteins enhance the antioxidant activity of phenolic compound extract from Cantaloupe melon pulp flour (Cucumis melo L.). Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, B.; Bousfield, D.W.; Wujcik, E.K. Antibacterial and biodegradable whey protein/gelatin composite films reinforced with lotus leaf powder and garlic oil for sustainable food packaging. Compos. Part B 2025, 303, 112549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; He, L.; Tian, Y.; Xie, J. Improving the preparation process to enhance the retention of cinnamon essential oil in thermoplastic starch/PBAT active film and its antimicrobial activity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 230, 120990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, P.; Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Li, C.; Jiang, F.; Xiao, M. Fast water absorption and antibacterial konjac glucomannan/xanthan gum/carboxymethyl cellulose film incorporated with rosmarinic acid for extending shelf life of chilled pork. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 229, 118102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluta-Kubica, A.; Jamróz, E.; Kawecka, A.; Juszczak, L.; Krzyściak, P. Active edible furcellaran/whey protein films with yerba mate and white tea extracts: Preparation, characterization and its application to fresh soft rennet-curd cheese. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 1307–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoshal, G.G.; Thakur, S. Thyme essential oil nano-emulsion/Tamarind starch/Whey protein concentrate novel edible films for tomato packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 124, 107312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, H.; Hamgini, E.Y.; Jafari, S.M.; Bolourian, S. Improving the oxidative stability of sunflower seed kernels by edible biopolymeric coatings loaded with rosemary extract. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2020, 89, 101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.D.L.D.; Carvalho, M.V.D.; Melo, L. Health promoting and sensory properties of phenolic compounds in food. Rev. Ceres 2014, 61, 764–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltelli, M.-B.; Wild, F.; Bugnicourt, E.; Cinelli, P.; Lindner, M.; Schmid, M.; Weckel, V.; Müller, K.; Rodriguez, P.; Staebler, A.; et al. State of the art in the development and properties of protein-based films and coatings and their applicability to cellulose based products: An Extensive Review. Coatings 2015, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.