Abstract

The increasing digitalization of smart grids has made them vulnerable to false data injection attacks (FDIAs), which can bypass traditional bad data detection (BDD) schemes and compromise grid security. While machine learning offers promising detection capabilities, existing methods often struggle with generalization, interpretability, and the effective integration of the grid’s inherent spatio-temporal properties. To address these challenges, this paper presents a hierarchical spatio-temporal graph attention network (HST-GAT) for FDIA detection in smart grids. The proposed FDIA detection method employs a dedicated two-stage architecture. First, a graph attention network (GAT) explicitly captures the complex spatial dependencies and physical constraints of the grid topology. Second, a temporal module with multi-head self-attention and a gated recurrent unit (GRU) analyzes evolving attack patterns across time steps. This hierarchical separation ensures a more interpretable and physically grounded representation of cyber intrusions compared to joint spatio-temporal models. Explainability analysis using the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method reveals the decision-making process of the proposed FDIA detection method, validating its alignment with the grid topology and identifying the key buses that influence its predictions. The results confirm the robustness of the proposed method and its value in improving cybersecurity in modern smart grids.

1. Introduction

Modern power grids have undergone a rapid transformation with the integration of renewable energy resources, distributed generation, and advanced information and communication technologies. The concept of smart grids has emerged as a cornerstone of this transformation, enabling increased efficiency, reliability, and resilience in electricity generation, transmission, and distribution. As a key component of smart grid operation, state estimation has been widely applied. It utilizes measurements from supervisory control and data acquisition systems, as well as phasor measurement units, to determine grid conditions. Accurate state estimation is essential for control, stability assessment, and contingency analysis of the grid. Therefore, the integrity of measurement data is of paramount importance for the secure and reliable functioning of smart grids [1].

However, the increasing reliance on interconnected digital infrastructures has exposed power systems to sophisticated cyber threats [2]. Among these, false data injection attacks (FDIAs) represent a particularly insidious class of attacks. By carefully manipulating sensor data, adversaries can craft malicious inputs that evade traditional bad data detection (BDD) schemes [3]. Consequently, the estimated grid states can be replaced by false data without triggering alarms [4]. Such undetected manipulation can lead to erroneous control decisions, resulting in financial losses, equipment damage, or even cascading blackouts with devastating societal consequences [5,6].

Early detection of measurement anomalies in smart grids relies on statistical BDD techniques, including chi-square tests and the largest normalized residual test. While effective against random noise, these methods fail against structured intrusions. Liu et al. [4] first demonstrated that adversaries can exploit knowledge of the measurement Jacobian to design undetectable false data injection vectors. Since then, the inherent inability of residual-based approaches to counter coordinated attacks has been widely acknowledged, motivating a shift toward data-driven detection.

Machine learning provides the next wave of solutions. Classifiers such as support vector machines, decision trees, and shallow artificial neural networks are applied to distinguish compromised from normal data [7,8]. These models improve detection accuracy under known attack patterns, but they rely heavily on large, balanced, and labeled datasets. Such datasets are scarce in real grids where attack events are rare and varied [9]. Few-shot learning approaches have been proposed to mitigate this issue [10], yet they often overlook the spatio-temporal dependencies inherent in grid data. Moreover, supervised classifiers often generalize poorly to adaptive or unseen attack vectors, restricting their practical deployment. To overcome feature engineering limitations, deep learning architectures are adopted. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been used to extract spatial correlations among measurements, while recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks capture temporal dynamics [11,12]. More recently, hybrid CNN–LSTM models, such as the convolutional LSTM proposed by Hasan et al. [13], have been used to integrate spatial and temporal features for pseudo-measurement modeling and attack detection. However, these architectures often entangle spatio-temporal dependencies into opaque representations. This complicates interpretability and risks overfitting on limited FDIA datasets, raising questions about their scalability to unseen attack scenarios.

Recognizing that smart grids are inherently graphs, recent studies have employed graph neural networks (GNNs) to embed topological constraints into detection models [14,15]. Graph convolutional networks (GCNs) and graph attention networks (GATs) allow the learning process to reflect physical connectivity between buses and lines, improving both detection accuracy and interpretability. Complementary approaches in semi-supervised and unsupervised learning, such as autoencoders and variational methods, address the scarcity of labeled attack data [16,17]. However, most graph-based detection methods focus on static spatial structures, while temporal correlations are either simplified or modeled with basic recurrent layers. Moreover, existing joint spatio-temporal methods often fuse both dimensions simultaneously. This risks conflation of distinct propagation processes, i.e., the spatial spread of anomalies across the grid and their temporal evolution through state transitions.

To address these gaps, we propose an FDIA detection method based on a hierarchical spatio-temporal GAT (HST-GAT). The main contributions of this work are fourfold:

- (1)

- A hierarchical architecture: We decouple the learning process into distinct spatial and temporal stages, moving beyond joint spatio-temporal models. This design provides superior interpretability and aligns more closely with the physical propagation characteristics of cyber intrusions in smart grids.

- (2)

- Advanced spatial encoding: We employ a GAT [18] to explicitly capture the complex structural dependencies and inherent physical constraints among buses and transmission lines, ensuring a faithful representation of the grid topology.

- (3)

- Coordinated temporal analysis: We integrate temporal self-attention mechanisms [19] to identify subtle and evolving attack patterns across successive time steps, enabling the detection of sophisticated, coordinated attacks that manifest only over time.

- (4)

- Interpretable and robust detection: The proposed model is designed not only for high accuracy but also for robustness under class imbalance, with an architecture amenable to explainability analysis, enhancing trustworthiness for real-world deployment.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 details the problem formulation and the architecture of the proposed HST-GAT. Section 3 describes the experimental setup, including the dataset, baseline methods, and evaluation metrics. Section 4 presents and discusses the results, including performance comparisons and explainability analyses. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Proposed Methodology

2.1. Graph Representation of the Grid

In the context of FDIA detection in smart grids, the system is modeled as a dynamic graph

where represents the set of nodes, which are generators or loads in the grid; denotes the connections (transmission lines) between nodes; and is the measurement data in time series, with being the feature matrix of the nodes at time step t, where F denotes the number of features per node.

Each node feature vector comprises four key physical quantities, i.e.,

The FDIA detection task is formulated as a spatio-temporal graph classification problem, i.e., given the historical measurements over a time window and the grid topology , the goal is to predict whether an attack is present at the current time step:

where is the binary label (0 for normal, 1 for attacked), f denotes the HST-GAT function, and represents the model parameters.

This detection task addresses the classical FDIA threat model [4], where an attacker is assumed to possess knowledge of the grid topology (e.g., bus-branch connectivity) and have the capability to compromise and manipulate measurements from a subset of sensors or buses.

2.2. Hierarchical Spatio-Temporal Graph Attention Network

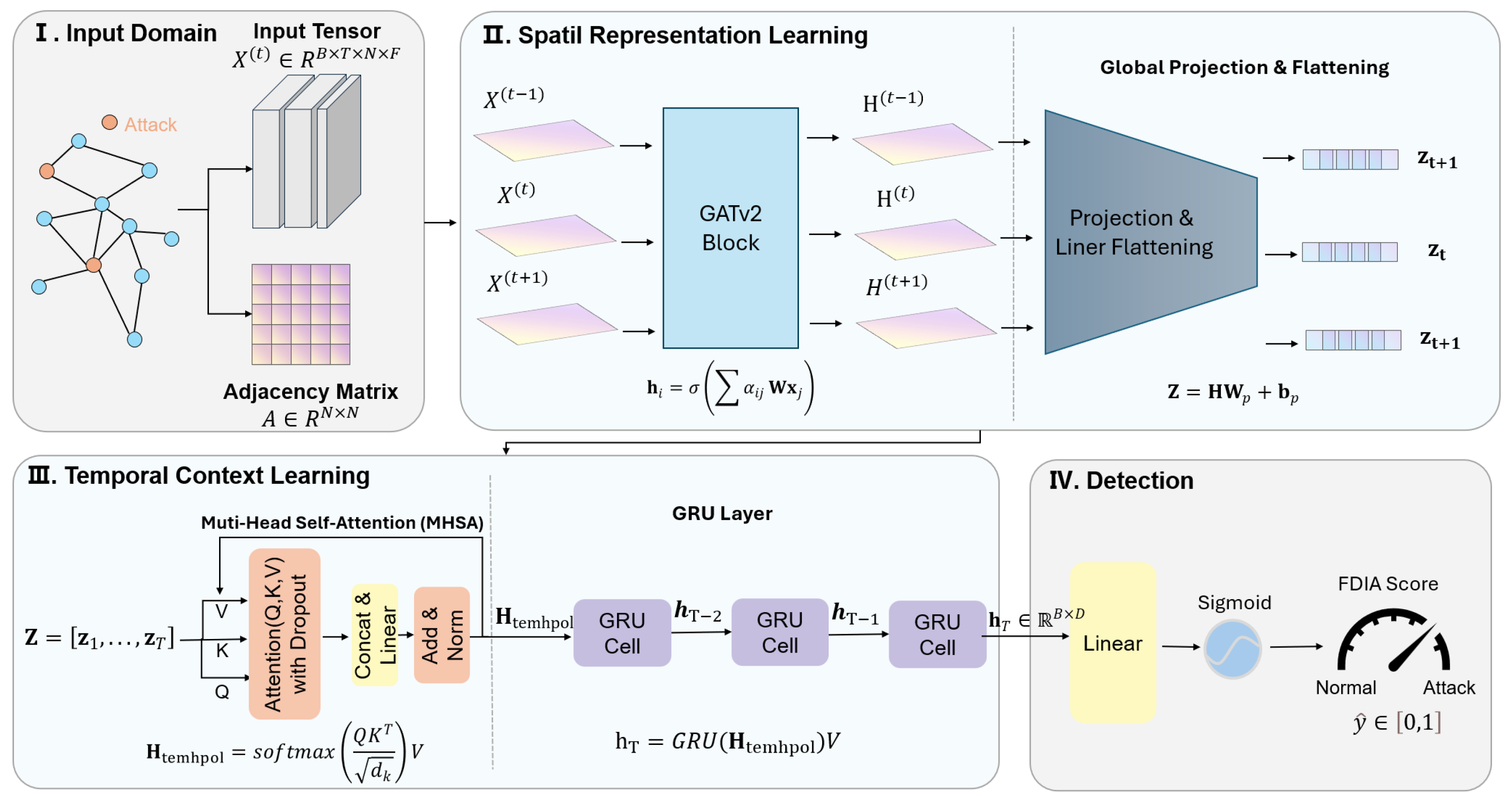

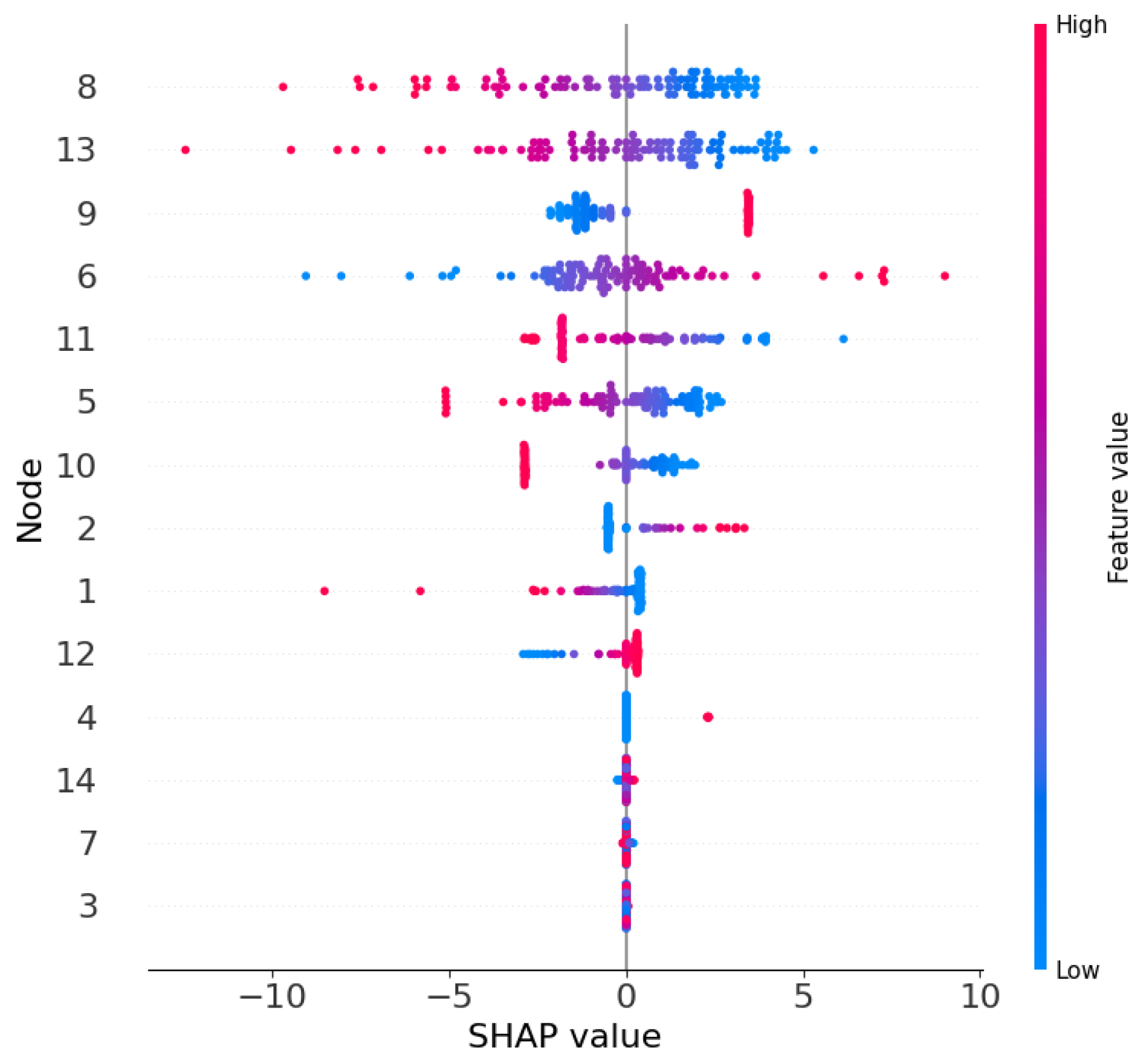

To explicitly decouple spatial and temporal dependencies, we designed the HST-GAT as a three-tier hierarchical architecture as shown in Figure 1. The input to the network is batched spatio-temporal graph data , where B is the batch size, T is the number of time steps, N is the number of nodes, and F is the feature dimension.

Figure 1.

An illustrative structure of the proposed HST-GAT.

The framework pipeline is as follows:

- (1)

- Spatial feature extraction layer: Utilizes GATv2Conv to encode spatial attention for the graph structure at each time step.

- (2)

- Temporal feature fusion layer: Employs linear projection and temporal attention mechanism to capture temporal dependencies.

- (3)

- Sequence modeling layer: Uses a gated recurrent unit (GRU) to further learn temporal dynamics.

- (4)

- Classification output layer: Performs attack detection classification based on the final hidden state.

This hierarchical design enables progressive feature learning from local spatial patterns to global spatio-temporal representations. Each step is detailed in the following sections.

2.3. Spatial Attention Layer with GATv2Conv

The standard GAT computes attention with a monotonic function, which may fail to capture nuanced interactions between nodes. To deal with this issue, GATv2Conv is utilized in this study, which learns a dynamic attention mechanism capable of expressing non-monotonic relationships. The attention mechanism is computed as follows:

- (1)

- Attention coefficient calculation:where is a learnable weight matrix, is the attention vector, and ∥ denotes concatenation.

- (2)

- Normalized attention weights:where denotes the neighborhood of node i.

- (3)

- Node feature aggregation:

The model employs multi-head attention, and the output of each head is concatenated as follows:

The output of this layer has dimensions , where K is the number of attention heads and is the output dimension per head.

2.4. Temporal Attention Mechanism

The temporal attention layer aims to capture the importance of different time steps, addressing the gradient vanishing problem in traditional RNN for long sequences.

- (1)

- Feature reshaping and projection:First, the spatial features are reshaped into and then projected to a lower dimension via a linear layer:where is the projection matrix, is the bias vector and D is the projected dimension.

- (2)

- Multi-head temporal attention calculation:where Query (), Key (), and Value () are all derived from the projected features . The model uses two heads for temporal attention to enhance the capture of diverse temporal patterns.

The output of the temporal attention layer is a weighted temporal feature representation , along with an attention weight matrix that can be used for interpretability analysis.

2.5. GRU-Based Temporal Sequence Processing

While temporal attention identifies salient time steps, it may overlook longer-range dependencies. Therefore, we augment the temporal module with a GRU to capture sequential evolution patterns that span beyond the attention window. This hybrid design ensures that both short-term anomalies and prolonged attack campaigns are detectable. The GRU mechanisms are given as follows:

- (1)

- Update gate and reset gate:

- (2)

- Candidate hidden state:

- (3)

- Final hidden state update:

The GRU layer outputs the hidden state of the last time step as a compact representation of the entire spatio-temporal sequence.

2.6. Output Layer and Loss Function

The output layer and loss function are calculated as follows:

- (1)

- Classification output layer:where is the sigmoid activation function, and denotes the probability of an attack.

- (2)

- Loss function:The binary cross-entropy loss is used:

- (3)

- Regularization strategies:Dropout with a rate of 0.2 is applied to prevent overfitting, weight decay (L2 regularization) with a coefficient is used, and batch normalization is applied after the spatial attention layer to accelerate training convergence.

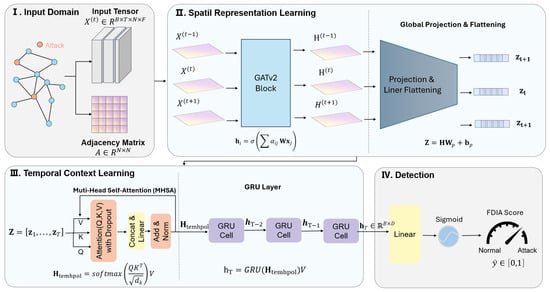

The proposed HST-GAT method is given in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: HST-GAT Forward Propagation |

|

3. Experiment Setup

This section elaborates on various aspects of the experimental design, including dataset construction, baseline methods, evaluation metrics, and implementation details. The experiments were based on real-world grid data, utilizing the IEEE 14-bus and IEEE 118-bus test cases as the simulation platforms. All experiments were conducted under identical hardware and software environments to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the results.

3.1. Dataset Construction

The dataset was constructed using a generation method based on real load data, which was sourced from the historical load data provided by the New York Independent System Operator, with a time resolution of 5 min. The regional load data was mapped to the corresponding nodes of the test system using a proportional allocation method, ensuring a reasonable load distribution.

The attack injection strategy was designed considering the stealthiness characteristics of real-world attacks. Target nodes were selected randomly, and FDIAs were constrained by physical limits. Specifically, the modification range for voltage magnitude was controlled within ±10–20%, and the phase angle modification range was within ±5–15°. Attack patterns included single-node attacks and multi-node coordinated attacks. The attack duration was categorized into short-term attacks (5–10 time steps) and sustained attacks (20–30 time steps). The final generated dataset contained 10,000 samples, comprising 7000 normal samples and 3000 attack samples, resulting in an attack sample ratio of 30%.

In the data preprocessing stage, Gaussian noise with a standard deviation of 0.05 was incorporated into the measurement data to simulate real sensor imperfections. The original measurement data were first normalized using the formula:

where and s are the mean and standard deviation of the feature, respectively. Subsequently, time window sequences were constructed with a window length of 10 time steps and a sliding step of 1, forming a tensor format suitable for spatio-temporal graph models.

3.2. Baseline Methods

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed method, we performed extensive comparisons with both traditional and advanced FDIA detection methods, including GGNN-GAT [20], TSGCN [21], DAMGAT [22], SAGE [23], GCN [24], CNN-GRU [25], Transformer [26], and CNN [27]. Table 1 provides a targeted architectural comparison between HST-GAT and representative spatio-temporal GNNs, highlighting our key methodological contributions.

Table 1.

Comparison of spatio-temporal graph neural network architectures.

All baseline methods used the same input data and training–test split. Hyperparameters were determined through grid search to find the optimal configuration, ensuring a fair comparison. Specifically, for GNN-based methods, the same graph structure information—the topological connectivity of the IEEE 14-bus and IEEE 118-bus systems—was used.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

A multi-dimensional evaluation index system was adopted to comprehensively assess the detection performance. The primary detection metrics included accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, which reflect the classifier’s performance from different angles. The precision and recall are defined as follows:

where , , and denote true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. The F1-score was calculated as the harmonic mean of precision and recall:

In addition to these basic metrics, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and precision–recall (PR) curves were used to evaluate the model’s overall performance under different thresholds.

3.4. Implementation Details

The experiments were conducted on a server equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4060 Laptop GPU and an Intel i7-12800HX CPU. The software environment included Python 3.10, PyTorch 2.8.0, and PyTorch Geometric 2.6.1. Power flow calculations were performed using the pandapower 3.1.2 toolbox.

To ensure the optimal performance of the proposed HST-GAT model, a grid search strategy was employed to determine the key hyperparameters. The search space included learning rates within , hidden dimensions within , and temporal window sizes within . The final hyperparameter configuration, selected based on the highest F1-score on the validation set, is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Optimal hyperparameters for the HST-GAT model.

An early stopping strategy was employed to prevent overfitting, with a patience value of 15. To address the class imbalance issue, a weighted binary cross-entropy loss function was used:

where the weight for normal samples is 0.3, and the weight for attack samples is 0.7. The dataset was randomly split into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:1:2 ratio. Five-fold cross-validation was used during training to evaluate model generalization. To ensure the reproducibility of the experimental results, the random seed was fixed to 1234.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Performance Analysis and Comparative Evaluation

The overall performance metrics are summarized in Table 3. One can notice that the proposed HST-GAT achieves competitive results across all evaluation criteria. The model also shows distinctive characteristics in precision and recall trade-offs.

Table 3.

Comparison of different detection methods in the IEEE 14-bus and IEEE 118-bus systems.

In addition to detection accuracy, we evaluated the inference time of HST-GAT to assess its real-time applicability. The model achieves an average detection latency of 11.971 ms per sample on the IEEE 14-bus system, and 12.637 ms per sample on IEEE 118-bus system, corresponding to a detection frequency of 83.5 Hz and 79.1 Hz, which meets the common real-time requirement in grid monitoring environments.

4.1.1. Overall Performance Comparison

On the IEEE 14-bus system, the proposed HST-GAT achieves an accuracy of 98.70%, a precision of 100%, a recall of 96.02%, and an F1-score of 97.97%. While the model demonstrates superior performance compared to baseline methods, the results reveal an important characteristic of the detection behavior. The perfect precision score of 100% indicates that the model completely avoids false positive detections, meaning all identified attacks are genuine. However, the recall of 96.02% suggests that approximately 4% of actual attacks remain undetected.

To assess scalability, we further evaluated HST-GAT on the larger and more complex IEEE 118-bus system. As shown in Table 3, the model maintains a precision of 100%, and the overall accuracy remains high at 92.38%, significantly outperforming all baselines. However, the recall drops to 75.56%, indicating increased difficulty in capturing all attack signatures within more intricate topologies and diverse propagation paths. This performance trade-off highlights both the model’s strength in reliability and an important challenge for detecting subtle attacks in large-scale grids.

4.1.2. Analysis of Precision–Recall Trade-Offs

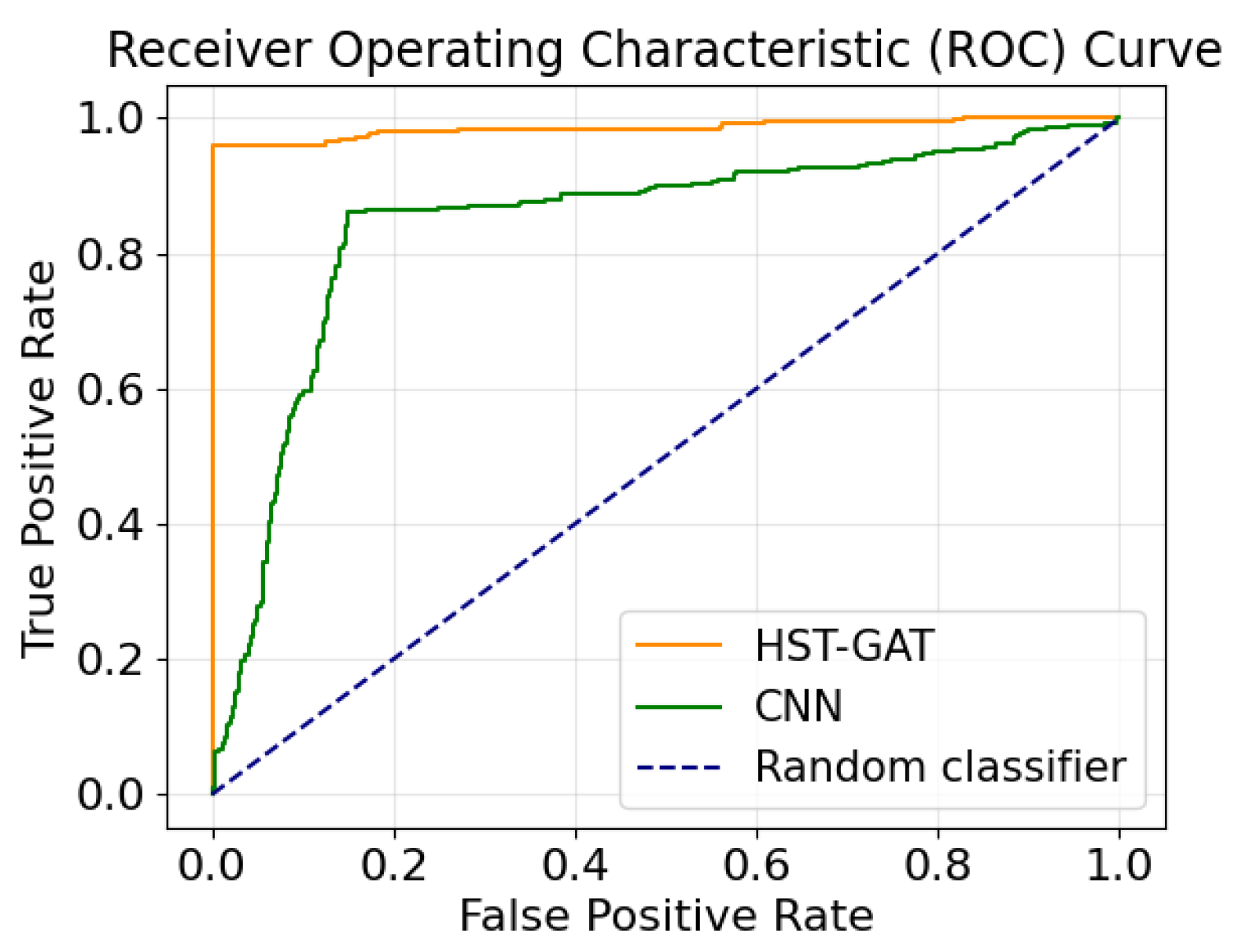

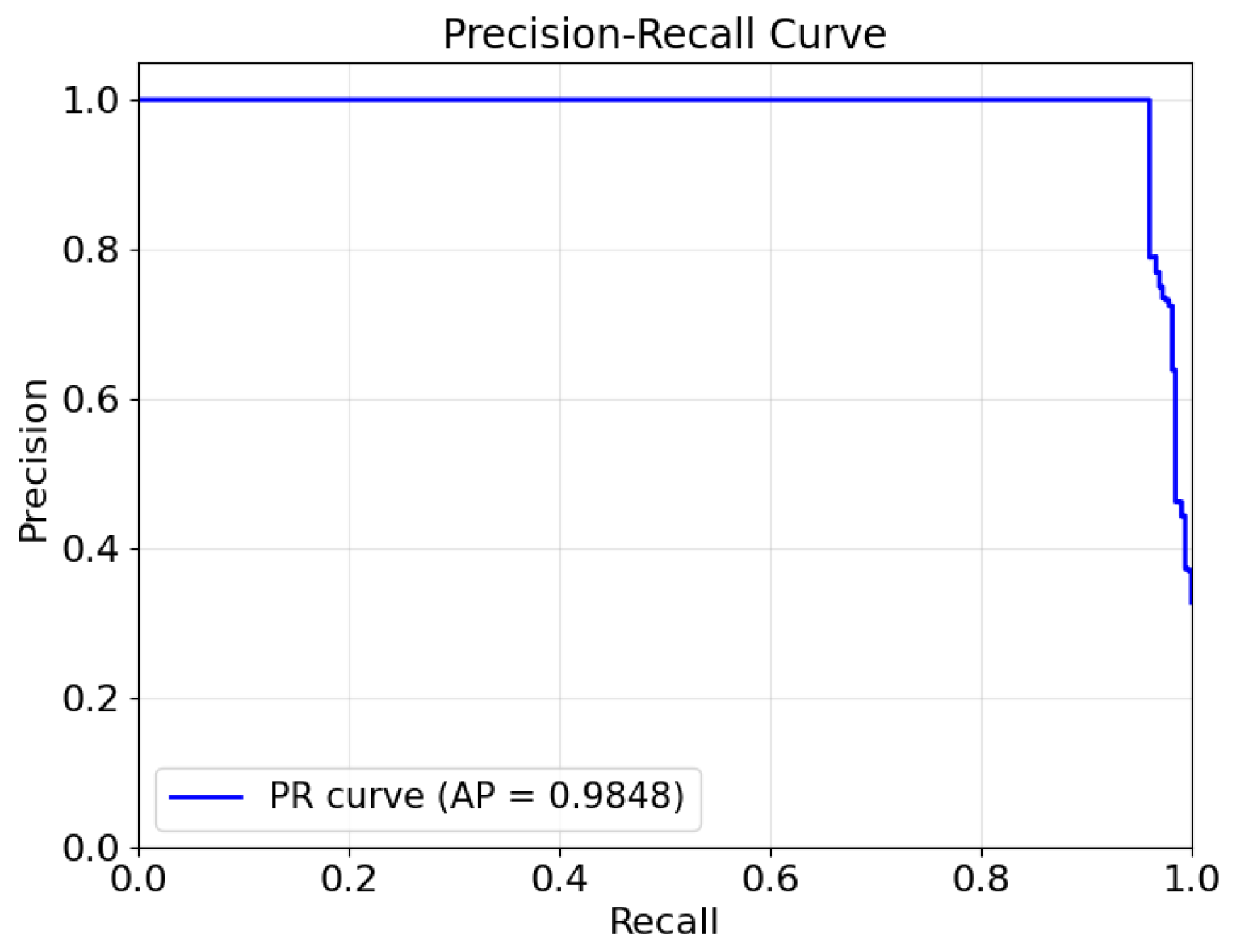

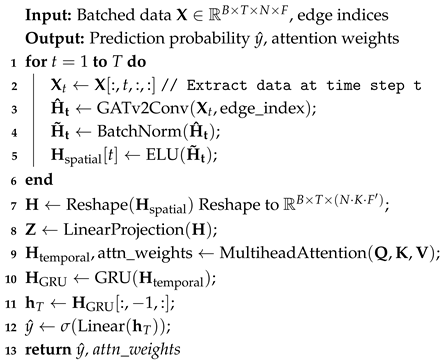

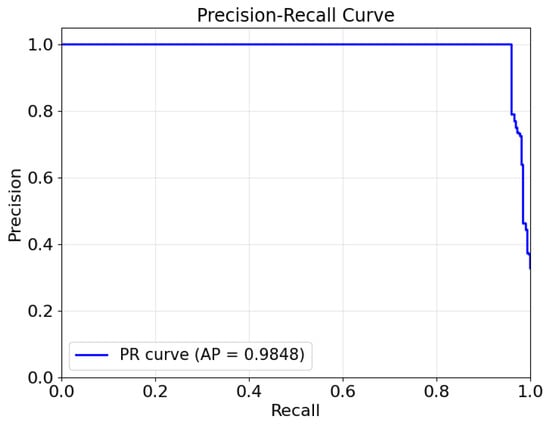

To holistically evaluate the model performance across all classification thresholds and under class imbalance, we present the ROC and PR curves in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively.

Figure 2.

HST-GAT’s and CNN’s ROC curves on the IEEE 14-bus system.

Figure 3.

HST-GAT’s PR curve on the IEEE 14-bus system.

The exceptional precision performance of the HST-GAT can be attributed to several architectural features. The spatial attention mechanism employing GATv2Conv enables highly selective focus on genuinely anomalous patterns while effectively filtering out normal operational variations. This selective attention reduces false positives but may also lead to missed detections when attack signatures are subtle or resemble normal operation patterns.

The observed recall rate of 96.02% indicates several potential limitations. Some attack patterns may not sufficiently deviate from normal operation to trigger detection, particularly if they affect nodes with lower attention weights or occur during periods of high system variability. Additionally, the model’s conservative detection threshold, while beneficial for precision, inevitably results in some missed detections.

4.1.3. Comparative Performance Analysis

The performance comparison reveals distinct operational characteristics across different model architectures. HST-GAT’s precision-focused performance contrasts with models like DAMGAT, which achieves higher recall (93.12%) but lower precision (92.14%). This difference reflects fundamental architectural choices and optimization objectives.

The performance gap between HST-GAT and other methods widens on the 118-bus system. Sequence models, e.g., CNN-GRU and Transformer, suffer dramatic performance degradation, reflecting their inability to encode large-scale topological constraints effectively. Graph-based baselines, e.g., GGNN-GAT and DAMGAT, also exhibit notable drops in recall and F1-score. In contrast, HST-GAT retains a clear advantage, validating that its hierarchical decoupling of spatial and temporal learning generalizes more effectively to complex grid topologies.

4.2. Explainability Analysis

For the detection of FDIAs in smart grids, deep learning models such as HST-GAT have demonstrated high accuracy, but their decision-making processes are often regarded as “black boxes”, which limits the trustworthiness and deployability of these models in critical infrastructure. To unveil the internal decision-making mechanism of HST-GAT, this section presents an explainability analysis based on the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method. SHAP is an explainability technique grounded in game theory, capable of quantifying the contribution of each input feature to the model’s predictions, making it suitable for complex spatio-temporal graph networks.

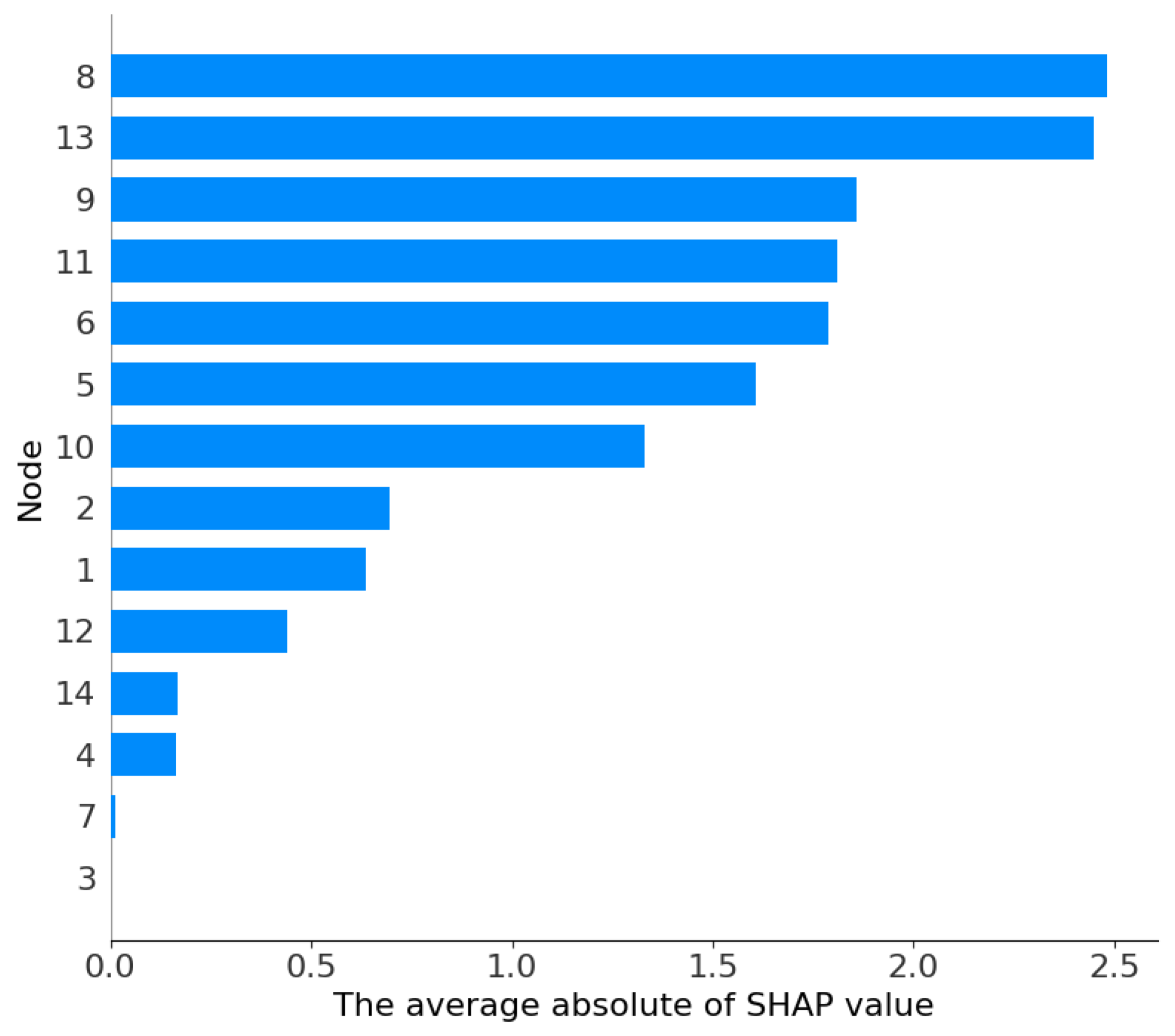

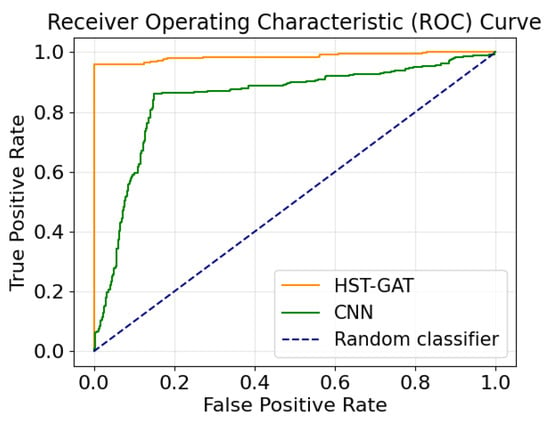

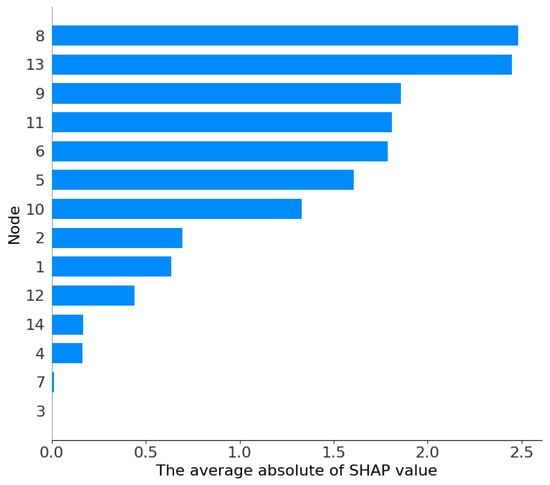

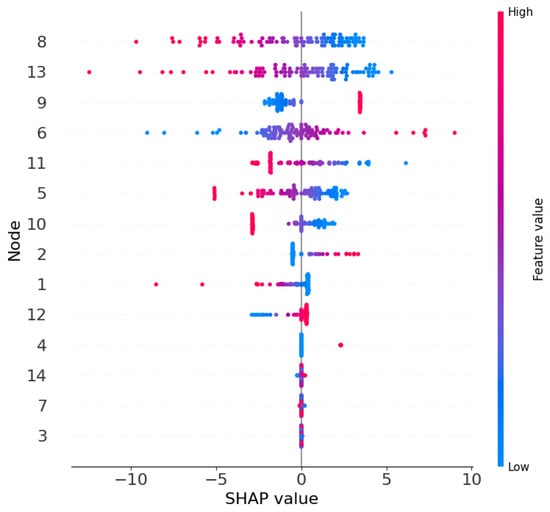

The SHAP analysis aims to quantify the contribution of each node feature in the HST-GAT model to FDIA detection decisions. Visualization was generated using the Python SHAP library, producing two key figures: Figure 4, a bar chart of feature ranking without distinguishing feature values, showing the average absolute SHAP values for each node to evaluate feature importance, and Figure 5, a scatter plot of feature ranking distinguishing feature values, showing the distribution of SHAP values for each sample, where point colors indicate feature values, red corresponds to high feature values, and blue corresponds to low feature values.

Figure 4.

SHAP feature contribution plots on the IEEE 14-bus system.

Figure 5.

SHAP bar for the IEEE 14-bus system.

4.2.1. Results Analysis

According to Figure 4, the SHAP importance ranking of the nodes is as follows: 8, 13, 9, 6, 11, 5, 10, 2, 1, 12, 4, 7, 14, 3. Among these, nodes 8 and 13 have the highest SHAP importance, and nodes 9, 6, and 11 have secondary importance. This ranking aligns with the topological roles in the IEEE 14-bus system. Nodes 8 and 13 are typically load buses. Their high importance is consistent with expectations for FDIA detection, as attacks often target load measurements for FDIA. In contrast, nodes 14 and 3 are located at the network periphery or play minor roles; hence, their contribution is lower.

Figure 5 reveals the impact patterns of feature values on SHAP values. In the figure, point colors represent feature values: red points correspond to high feature values, and blue points correspond to low feature values.

For nodes 8 and 13, high feature values primarily correspond to negative SHAP values, while low feature values correspond to positive SHAP values. This indicates that when the measurements of these nodes are high, the model tends to predict a normal state, leading to negatively impacting attack detection. Conversely, low measurements promote the detection of an attack. In contrast, for nodes 9 and 6, the low feature values correspond to the negative SHAP values, and the high feature values correspond to positive SHAP values.

Overall, the pattern of high feature values corresponding to negative SHAP values dominates in key nodes, which may cause the model to miss detections when attacks lead to high measurements.

4.2.2. Case Studies

To further validate the results of the SHAP analysis, two typical attack samples were selected for case studies, demonstrating how SHAP values explain the decision-making process of HST-GAT.

The first case is a missed detection sample: a multi-node attack with abnormally elevated voltage measurements on nodes 8 and 13. The SHAP value calculation shows that the contributions of nodes 8 and 13 are negative, while the contributions of other nodes, such as 9 and 6, are smaller. This indicates that the model tends to predict a normal state due to the high feature values of nodes 8 and 13, leading to missed detection.

The second case is a correctly detected sample. In this sample, the power measurement of node 9 is abnormally high, while other nodes show minor changes. The SHAP values indicate that the contribution of node 9 is positive, while the contributions of nodes 8 and 13 are neutral. This indicates that the model relies on the high feature value of node 9 to correctly detect the attack, consistent with the impact pattern of the feature value. Visualization in Figure 5 supports this result: the red points for node 9 are concentrated in the positive SHAP value region. The case study demonstrates that SHAP analysis can effectively trace the model’s decisions, highlighting the HST-GAT’s dependency on specific node patterns.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we have presented a comprehensive study on the detection of FDIAs in smart grids using the HST-GAT method. The proposed FDIA detection method is designed to overcome critical gaps in the existing literature, particularly the inadequate handling of topological constraints and the entangled modeling of spatial and temporal dynamics. Our work systematically formulated the FDIA detection problem within a spatio-temporal graph learning framework and introduced an architecture that processes spatial and temporal features in a dedicated and hierarchical manner.

The core contribution of this research lies in the synergistic integration of GATv2Conv for dynamic spatial attention and a sequential temporal module with self-attention and GRU layers. This design not only achieves superior detection performance but also provides a more interpretable model that mirrors the physical propagation characteristics of the FDIAs. Experimental results on IEEE test systems provide compelling evidence of the method’s efficacy. The proposed FDIA detection method achieves a precision of 100% on the IEEE 14-bus and IEEE 118-bus systems, demonstrating its exceptional ability to eliminate false positives. However, the observed recall of 75.56% highlights the increased challenge of detecting attacks in larger and more complex topologies, which is a key limitation requiring further investigation.

Future work will focus on improving accuracy in large-scale grids through adaptive detection mechanisms, extending the framework to more stealthy attack variants, and exploring semi-supervised learning to reduce reliance on labeled attack data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z. and R.G.; methodology, D.W.; software, J.C.; validation, X.B., D.W. and R.G.; formal analysis, D.W.; investigation, J.C.; resources, X.B.; data curation, H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.; writing—review and editing, B.F.; visualization, B.F.; supervision, J.C.; project administration, H.Z.; funding acquisition, B.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Project of State Grid Ningxia Electric Power Company Ltd. (No. 2024-1025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to project restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Hongjie Zhang was employed by the State Grid Ningxia Electric Power Company; Authors Jichuan Cheng, Xue Bai and Dong Wang were employed by the Ultra-High Voltage Company, State Grid Ningxia Electric Power Company.The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The Science and Technology Project of State Grid Ningxia Electric Power Company Ltd. (No. 2024-1025) had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Qu, B.; Wang, Z.; Shen, B.; Dong, H.; Zhang, X. Secure particle filtering with Paillier encryption–decryption scheme: Application to multi-machine power grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 15, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.; Hahn, A.; Govindarasu, M. Cyber–physical system security for the electric power grid. Proc. IEEE 2011, 100, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shen, C.; He, N.; Han, S.; Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Guan, X. False data injection attacks against smart gird state estimation: Construction, detection and defense. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2019, 62, 2077–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ning, P.; Reiter, M.K. False data injection attacks against state estimation in electric power grids. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. Secur. (TISSEC) 2011, 14, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, G.O.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Marnerides, A.K. Energy Market Manipulation via False-Data Injection Attacks: A Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 42559–42573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, C.; Su, Q. Analysis of cascading failures of power cyber-physical systems considering false data injection attacks. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2021, 4, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozay, M.; Esnaola, I.; Vural, F.T.Y.; Kulkarni, S.R.; Poor, H.V. Machine learning methods for attack detection in the smart grid. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2015, 27, 1773–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Yan, J. Cyber-physical attacks and defences in the smart grid: A survey. IET Cyber-Phys. Syst. Theory Appl. 2016, 1, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, K.; Zhang, M.; Guo, F.; Lu, R.; Guan, X. Detection of False Data Injection Attacks in Smart Grids: An Optimal Transport-Based Reliable Self-Training Approach. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, K.; Zhang, M.; Chen, K.; Li, Y.; Zhan, X.; Guan, X. Learning to Match Prototype for Few-Shot Classification of Attacks and Faults in Smart Grids. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, A.; Mohamed, A.r.; Hinton, G. Speech recognition with deep recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 26–31 May 2013; pp. 6645–6649. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, P.; Vig, L.; Shroff, G.; Agarwal, P. Long short term memory networks for anomaly detection in time series. In Proceedings of the 2015 European Symposium on Artificial Neural Networks, Computational Intelligence and Machine Learning, Bruges, Belgium, 22–24 April 2015; pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.N.; Toma, R.N.; Nahid, A.A.; Islam, M.M.; Kim, J.M. Electricity theft detection in smart grid systems: A CNN-LSTM based approach. Energies 2019, 12, 3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Dai, H.N.; Tang, H. Graph neural networks for anomaly detection in industrial Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 9214–9231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; He, D.; Yu, L. Locational detection of false data injection attacks in smart grids: A graph convolutional attention network approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 11, 9324–9337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takiddin, A.; Ismail, M.; Atat, R.; Davis, K.R.; Serpedin, E. Robust graph autoencoder-based detection of false data injection attacks against data poisoning in smart grids. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2023, 5, 1287–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, K.; Zhang, M.; Fan, B.; Guan, X. Domain Adaptive Representation Learning for Attack Detection in Smart Grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. A comprehensive survey on graph neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z. Graph-based detection for false data injection attacks in power grid. Energy 2023, 263, 125865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Dou, C.; Yue, D.; Hancke, G.P.; Zeng, Z.; Guo, W.; Xu, L. End-edge-cloud collaboration-based false data injection attack detection in distribution networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 20, 1786–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Deng, C.; Yang, J.; Li, F.; Li, C.; Fu, Y.; Dong, Z.Y. DAMGAT-based interpretable detection of false data injection attacks in smart grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2024, 15, 4182–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, Q.; Chen, L.; Liang, Y.; Huang, H. An improved GraphSAGE to detect power system anomaly based on time-neighbor feature. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, E.; Korki, M.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Stojcevski, A.; Mekhilef, S. Reinforcement learning-empowered graph convolutional network framework for data integrity attack detection in cyber-physical systems. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 10, 797–806. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Gong, Y. False Data Injection Attack Detection Method Based on Deep Learning with Multi-Scale Feature Fusion. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 89262–89274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, X.; Li, Y.; Dong, Z.; Shahidehpour, M. Detection of false data injection attacks in smart grid: A secure federated deep learning approach. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 4862–4872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.D.; Zhou, L.; Wu, Z.G. Representation-learning-based CNN for intelligent attack localization and recovery of cyber-physical power systems. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 35, 6145–6155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.