1. Introduction

The Jurassic Shaximiao Formation in the central–northeastern Sichuan Basin is widely developed in a foreland tectonic setting, and its reservoirs generally exhibit typical tight-sandstone characteristics, including thin bedding, low porosity and permeability, and strong heterogeneity [

1,

2]. This foreland setting is mainly reflected by the development of broad, gentle detachment-controlled folds, thin-skinned structural styles, and long-term compressional deformation related to peripheral orogenic belts, rather than by strongly developed syn-tectonic growth strata. The Yingshan area is located in the transitional zone between the gentle structural belt of central Sichuan and the fold belt of northeastern Sichuan [

3]. It is jointly controlled by multi-phase compressional and detachment structures, forming a “dome–gentle slope” structural pattern dominated by the Yingshan anticline. In a shallow-water delta–fluvial depositional background, the Shaximiao Formation contains widely developed, multi-phase, superimposed channel sand bodies, which provide important storage and enrichment spaces for natural gas [

4]. In this system, deltaic deposits are mainly represented by distributary channels and mouth-bar-related sand–mud alternations, characterized by relatively frequent mudstone interbeds and moderate lateral continuity, whereas fluvial components are dominated by erosional-based channel sand bodies with blocky to bell-shaped log responses and higher vertical stacking frequency. These differences exert direct control on sand-body geometry, continuity, and reservoir connectivity.

However, the tight sandstone gas reservoirs of the Shaximiao Formation in the Yingshan area exhibit strong heterogeneity [

5]. The channel sand bodies are thin and vary laterally rapidly, and the complex near-surface conditions further degrade the imaging resolution and attribute sensitivity of conventional seismic data [

6,

7]. These limitations hinder the fine identification and reliable evaluation of favorable reservoirs. In practical exploration, this problem is particularly prominent: although drilling and test-production data indicate good overall oil and gas potential in the Shaximiao Formation—especially industrial gas flows widely obtained in the middle–lower part of the first member—the thinly bedded reservoirs, complex sand-body geometries, and frequent mudstone interlayers significantly reduce the stability and reliability of traditional reservoir prediction methods in delineating effective thick sands and major gas-bearing zones.

From the perspective of hydrocarbon accumulation mechanisms, the Yingshan area exhibits a clear “tri-element coupling” pattern [

8]: deep hydrocarbon-generating faults provide continuous vertical migration pathways; the crest of the anticline serves as the primary structural background for hydrocarbon updip accumulation and preservation; and the multi-phase, relatively well-connected channel sand bodies determine the scale of reservoir enrichment and the distribution of high-quality intervals [

9]. However, the superposition of these controlling factors further increases the complexity of sand-body distribution and imposes higher requirements on seismic resolution and quantitative interpretation.

In this study, we develop an integrated workflow that combines 2D-3D seismic processing with a quantitative interpretation for the Shaximiao Formation, emphasizing amplitude preservation and high resolution to achieve fine-scale three-dimensional characterization of tight sandstone reservoirs. Rather than introducing new geophysical methodologies, the primary scientific contribution of this work lies in the integrated, forward-modeling-constrained application of established seismic processing, multi-attribute analysis, and rock-physics-driven inversion techniques to systematically resolve the detectability, thickness quantification, and spatial distribution of thin, heterogeneous tight sandstone reservoirs. By quantitatively identifying the seismic responses of thin sand bodies and predicting the distribution of effective reservoir thickness, and by integrating interpretation results with structural position, hydrocarbon-supply pathways, and sedimentary microfacies, we establish a reservoir-forming model characterized by “deep hydrocarbon generation with upward migration, fault-controlled charging, structural trapping, and microfacies-controlled enrichment.” The results provide a reliable and transferable basis for predicting sweet spots and for subsequent exploration and deployment of tight sandstone gas reservoirs in the Yingshan area and comparable foreland-basin settings.

3. Methods and Results

In this study, we developed the geological complexity of the Yingshan Shaximiao oil–gas reservoir by adopting an integrated research approach of “from macro to micro, from structure to reservoir, and from qualitative to quantitative.” A systematic workflow—combining structural interpretation, reservoir prediction, and hydrocarbon accumulation analysis—was established, as illustrated in

Figure 3. In this workflow, key techniques such as coherent-noise suppression (to enhance seismic signal continuity), wavelet compression (to improve vertical resolution), first-break picking and static corrections (to ensure accurate time positioning), and attribute optimization (to highlight thin-sandstone responses) are implemented at appropriate stages to improve data quality and facilitate interpretation. The workflow aims to accurately delineate reservoir characteristics, identify the main controlling factors of hydrocarbon accumulation, and ultimately guide exploration and development decision-making. To ensure the reliability of amplitude-based attributes and quantitative interpretation, amplitude-preserving processing strategies—including surface-consistent corrections, true-amplitude recovery, Q-compensation, and controlled gain application—were explicitly applied throughout the seismic processing workflow.

First, a detailed structural framework interpretation and evolutionary analysis were conducted. The structural configuration exerts fundamental control over hydrocarbon migration and accumulation. Based on high-resolution 3D seismic data and well-seismic calibration, the major reflection interfaces within the Shaximiao Formation were precisely correlated and interpreted, leading to the establishment of a reliable structural–stratigraphic framework. Key faults that control hydrocarbon migration and accumulation were systematically characterized, including analyses of their geometric and kinematic features. On this basis, structural evolution was reconstructed to reveal the spatiotemporal development of the structural–fault system, clarify the evolution stages of hydrocarbon-source faults, and determine their coupling relationship with hydrocarbon-charging stages, thereby defining the macro-scale structural controls on hydrocarbon accumulation.

Second, fine-scale reservoir characterization and sedimentary microfacies analysis were conducted at the sublayer level. To achieve accurate reservoir prediction, high-resolution sequence stratigraphic division and correlation were performed within the structural framework, subdividing the target interval into multiple key sublayers. For these sublayers, the following approaches were integrated:

Forward modeling analysis: Geological models were built for seismic forward modeling to identify seismic response characteristics of different sand-body geometries, providing a theoretical basis for seismic interpretation.

Seismic attributes and inversion: Multiple seismic attributes (e.g., RMS amplitude, instantaneous frequency) were used for qualitative reservoir identification and boundary delineation. Subsequently, quantitative reservoir prediction—such as porosity and sandstone thickness—was achieved through acoustic-impedance inversion and related geophysical techniques.

Sedimentary microfacies characterization: By integrating inversion results, log facies, and core data, fluvial-channel-dominated sedimentary microfacies were analyzed to determine the spatial distribution patterns of favorable reservoirs. Single-well and well-to-well correlation further validated the reservoir-prediction results, leading to the establishment of a 3D geological model of reservoir distribution. To extrapolate sedimentary microfacies into interwell areas, an integrated, constraint-driven approach was adopted. Microfacies identified at well locations based on core observations and log facies served as calibration points. In interwell regions, seismic attribute responses were interpreted only when they were consistent with forward-modeled seismic signatures of fluvial sand bodies in terms of amplitude polarity, frequency content, and apparent thickness. Rock-physics–constrained seismic inversion results, particularly acoustic impedance and effective thickness volumes, were further used to distinguish sand-dominated from mud-dominated facies quantitatively. Microfacies interpretation was accepted only when seismic attributes, inversion responses, and stratigraphic trends were mutually consistent, thereby reducing subjectivity in interwell extrapolation. Consequently, prediction confidence is highest in areas characterized by strong well control and stable bipolar seismic responses, and decreases toward zones with thinner beds or weaker seismic illumination.

Finally, a comprehensive hydrocarbon accumulation analysis and exploration-target optimization were performed. Based on the structural and reservoir analysis results, the hydrocarbon accumulation characteristics of the study area were systematically summarized. By analyzing the key accumulation factors—including source, reservoir, seal, migration, trap, and preservation—the main controls on hydrocarbon enrichment were identified, and a hydrocarbon accumulation model consistent with the geological setting was established. Integrating favorable structural zones, reservoir-development trends, and accumulation dynamics, the exploration potential of different target zones was quantitatively evaluated and ranked. Ultimately, potential blocks and optimal well-location targets were selected, providing direct scientific support for subsequent exploration deployment.

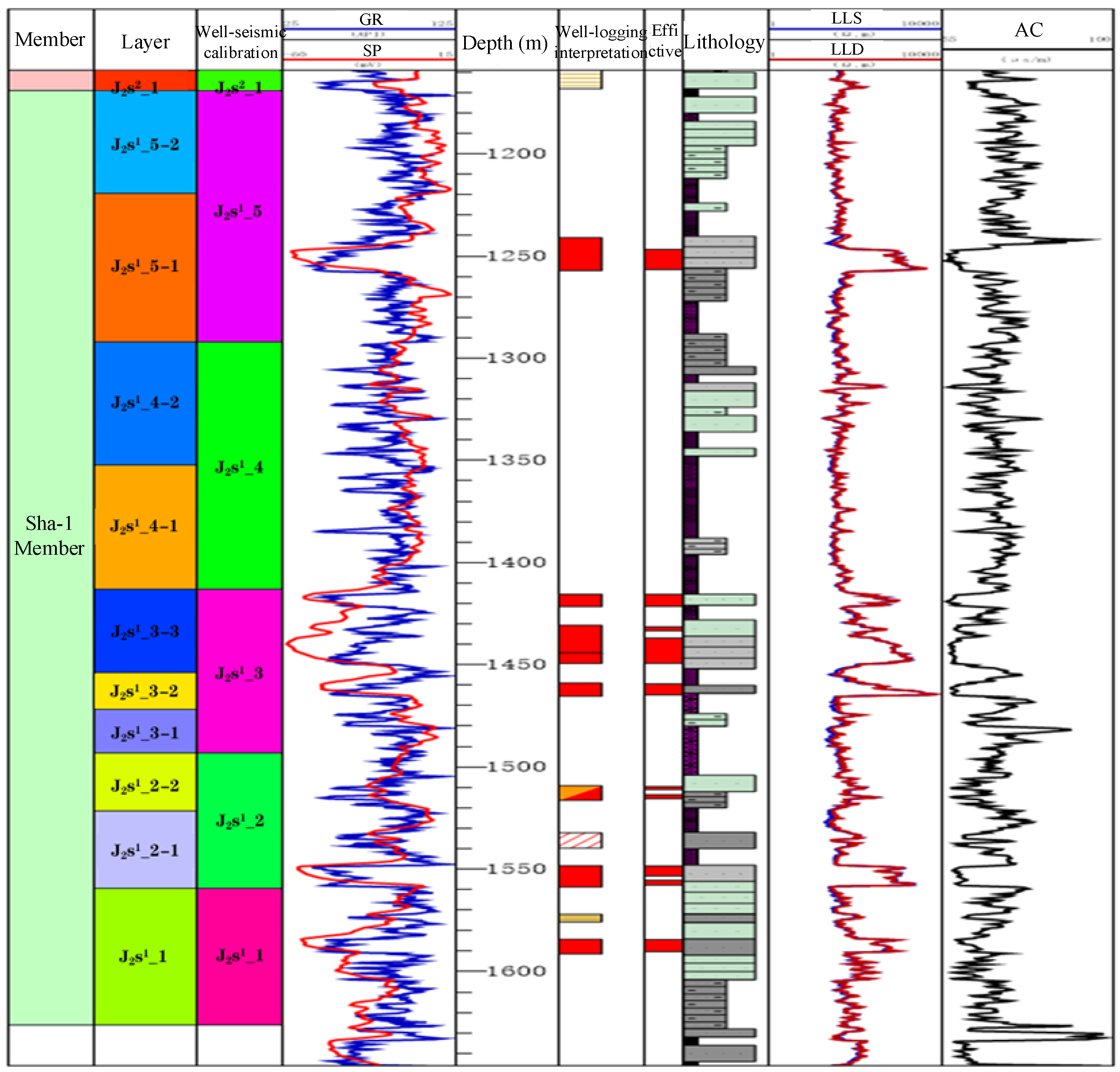

3.1. Fine-Scale Sublayer Division and Correlation

To enable accurate correlation of thin interbeds and narrow channels, the Shaximiao Formation was subdivided into cross-well comparable sublayer units based on regional sequence stratigraphy. Stable sequence boundaries and marker shales (e.g., maximum lacustrine flooding surfaces) were used as references. Logging facies (GR, SP, sonic/density) and core-identified depositional cycles [

16] were combined to recognize vertical rhythms such as coarsening-up or fining-up patterns, forming a three-tier framework of sublayer–sub-member–member. Such frameworks, tied to key stratigraphic surfaces and system tracts/subsequences, are standard practice in sequence stratigraphy to ensure cross-well connectivity and constrain attribute and inversion windows [

17,

18].

For well-to-seismic calibration, synthetic seismic traces were generated for each key well, as shown in

Figure 4, to ensure phase consistency, time–depth accuracy, and waveform stability prior to inversion and attribute analysis. The main procedures are summarized below.

- (1)

Reflection coefficient calculation

Based on QC-ed sonic transit time Δt and density ρ, the P-wave velocity is obtained as

, and the acoustic impedance is then computed as

. The reflection coefficient at each interface is given by

which forms the basis for subsequent synthetic seismogram construction.

- (2)

Wavelet estimation near the well

Wavelet estimation was performed using commonly adopted approaches such as statistical matching, constant-phase rotation, and frequency-domain least-squares optimization [

19,

20,

21]. In this study, a least-squares criterion was used to derive a wavelet compatible with the local seismic bandwidth and well-log reflectivity:

with the frequency-domain solution

where * denotes complex conjugation and λ is a stabilization factor. A zero-phase wavelet was selected to facilitate direct alignment between seismic peaks/troughs and impedance contrasts. The wavelet length was determined according to the dominant frequency range of the seismic data and the stability of the well tie, ensuring a balance between temporal resolution and noise suppression.

- (3)

Time–depth relationship and velocity correction

Checkshot and/or VSP data were used to establish the depth–two-way-time relationship

. Residual velocity drift was corrected to minimize cumulative timing errors:

where

represents the drift-compensation term derived from well-to-seismic misfit analysis.

- (4)

Synthetic seismogram generation

Synthetic seismic traces were generated using the convolutional model:

with localized phase and time-shift adjustments applied to optimize waveform similarity between synthetic and field seismic data in terms of amplitude, phase, and frequency content.

- (5)

Crossline closure checking

The interpretability of key horizons is validated on strike/dip sections around the well, and the closure misfit is quantified as follows:

Here, smaller misfit values indicate more reliable horizon tracking. In this study, only well ties satisfying a closure misfit of approximately 1–2 ms were accepted for subsequent inversion and attribute analysis.

Following single-well calibration, cross-well correlation was performed along survey lines within the established stratigraphic framework. Sublayer boundaries were used as control surfaces for horizon tracking in the 3D seismic volume, enabling the identification of systematic seismic response variations among different depositional units. In the Shaximiao Formation, fluvial-controlled sand bodies typically exhibit a strong-peak top and strong-trough base bipolar response under suitable frequency bands and velocity contrasts, whereas upward transitions commonly show weaker amplitudes, reduced continuity, and more chaotic reflection patterns. This characteristic “stronger at the base, weaker at the top” seismic expression reflects fluvial–interdistributary bay depositional cycles, but its detectability is strongly dependent on the local frequency content and effective bed thickness, which are quantitatively evaluated in subsequent forward-modeling analyses.

The fine-scale sublayer correlation is shown in

Figure 5. Based on the fluvial-channel development characteristics of the study area, the first member of the Shaximiao Formation was subdivided into ten sublayers, corresponding to ten stages of major channel development. On the seismic profiles, this interval is characterized by weak amplitudes, poor continuity, short-axis reflections, and sub-parallel configurations with observable incisions and imbricated reflection patterns. These multi-phase channel-filling cycles and thin interbeds are interpreted to be predominantly controlled by autocyclic processes, such as lateral channel migration, avulsion, and repeated incision-filling under relatively stable climatic and tectonic conditions. Allocyclic controls, including regional base-level fluctuations, are considered secondary and mainly influence accommodation space and vertical stacking intensity. As a result, reservoir distribution is characterized by strong lateral heterogeneity and localized connectivity at the sublayer scale, which increases uncertainty in well-based prediction but allows effective delineation of channel belts and stacked sand-prone zones using high-resolution seismic attributes.

In the quality-control (QC) workflow, fine sublayer correlation was accompanied by three concurrent checks. First, wavelet phase and polarity consistency were verified to avoid peak–trough inversion caused by polarity reversal, using waveform coherence and wavelet spectral-ratio diagnostics. Second, horizon closure and residual statistics were examined, requiring crossline and cross-azimuth misfits to remain within approximately 1–2 ms; otherwise, time–depth calibration or wavelet estimation was re-adjusted. Third, geological plausibility was assessed by ensuring consistency with sedimentary facies interpretation, log-facies patterns, inter-well thickness trends, and channel-distribution geometry. Only sublayer boundaries satisfying all three criteria were retained, ensuring reliable inter-well correlation and a robust foundation for subsequent inversion and attribute-based analysis.

It should be emphasized that these sublayers represent stratigraphically consistent interpretation units rather than seismically independent beds. Their definition is primarily constrained by well-log cycles and sequence-stratigraphic markers, while seismic data provide support for lateral continuity and sand-prone trends within the limits of vertical resolution.

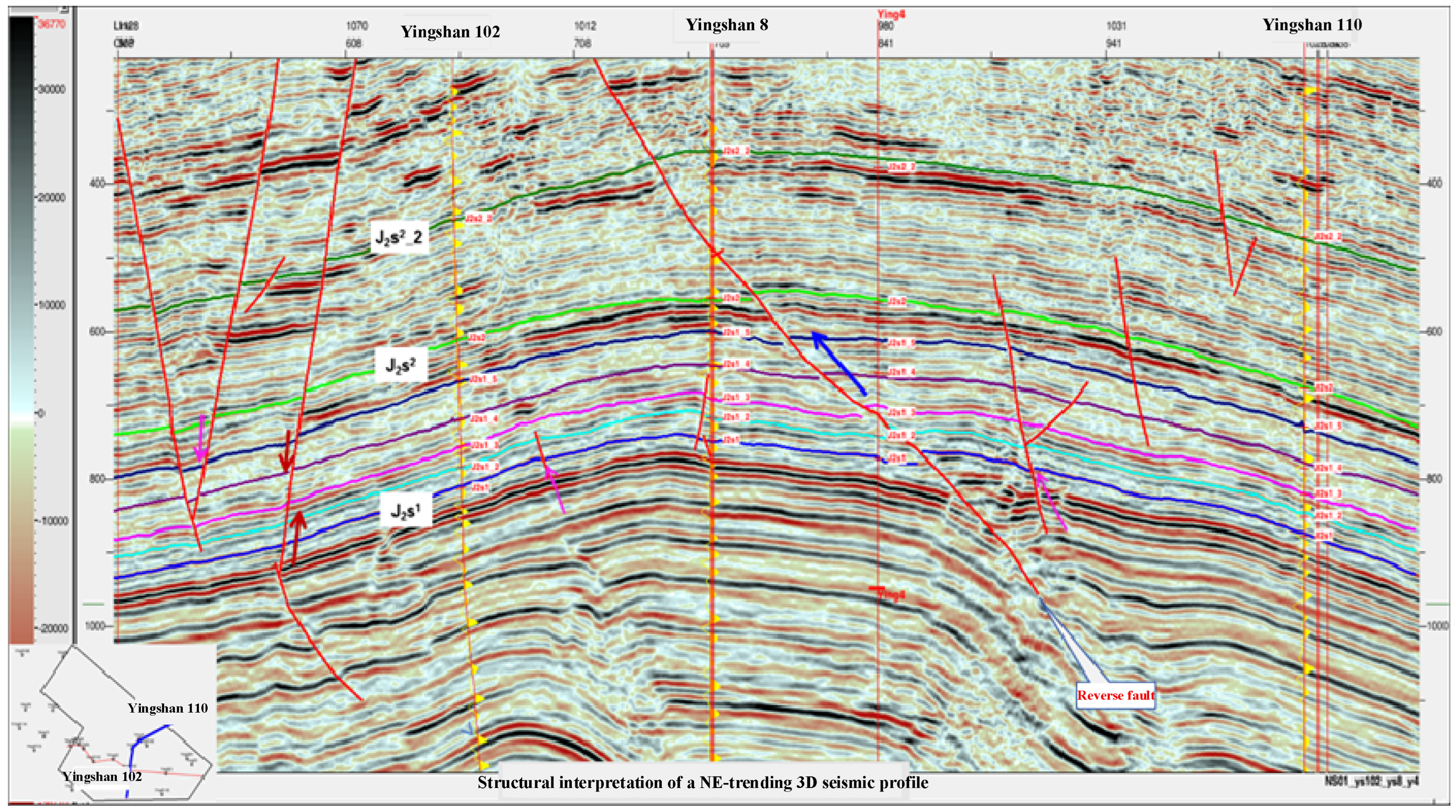

3.2. Detailed Structural and Fault Interpretation

In the Yingshan area and the Shaximiao Formation, where the overall structure is gentle and local minor faults develop, faults not only control sedimentary microtopography and sand-body distribution but also determine trap integrity and hydrocarbon migration pathways [

22]. Therefore, it is essential to enhance the identification of subtle faults and minor discontinuities within the 3D seismic volume. To achieve this, a “hierarchical interpretation-integrated discrimination” workflow was adopted.

First, a first-order fault–fold framework was established on conventional pre-stack and post-stack sections. Subsequently, voxel-scale discontinuity and geometric attributes were computed, including coherence and its improved algorithms [

23], curvature, multi-band 3D curvature [

24], and ant/particle-swarm-based fault-enhancement volumes [

25]. Structurally oriented filtering was applied to suppress noise and improve fault discrimination. Horizon and horizontal slices were then used to verify closure, connectivity, and displacement, resulting in a reliable fault system map.

The detailed procedure is as follows:

- (1)

Coherence attributes and discontinuity characterization: Coherence, based on waveform similarity, is the fundamental approach for three-dimensional fault detection. Its most widely used form is the eigenvalue-based coherence coefficient (C3 coherence) derived from the cross-trace covariance matrix. For a covariance matrix within a voxel neighborhood and its ordered eigenvalues , the three-dimensional coherence is expressed as

When faults or discontinuities occur, waveform dissimilarity among traces increases and becomes significantly larger than the other eigenvalues, resulting in a reduction in Coh; in contrast, within continuous reflectors, the three eigenvalues are comparable, and Coh approaches 1. Coherence attributes displayed on time or horizon slices can directly highlight fault streaks, channels, and other geometric discontinuities, thereby providing a base map for automatic tracking and fault extraction.

- (2)

Curvature and multi-scale curvature volumes: Curvature attributes are more sensitive to subtle bending, flexure, folding, and small-offset faults along reflectors, and therefore compensate for the limited resolution of coherence in weak-discontinuity domains. Using spatial variations in the reflector-normal vector field , the principal curvatures and can be derived, and the mean curvature is given by

High-curvature regions commonly correspond to fault-tip zones, drag folds, channel margins, or depositional terraces. Multi-scale curvature volumes, produced by filters of different wavelengths, enhance sensitivity to structural morphologies at multiple scales, providing a more complete depiction of fault strikes, variations in fault throw, and paleo-geomorphologic features.

- (3)

Mathematical formulation of structure-oriented filtering: To enhance subtle fault breaks in seismic volumes—particularly in settings characterized by “continuous reflectors but broken faults” or elevated noise—we apply structure-oriented filtering within voxel neighborhoods. Its fundamental principle is to smooth along reflector dip/azimuth directions while preserving edges in the perpendicular direction:

The first exponential term enforces smoothing consistent with structural orientation (structural coherence), whereas the second term preserves amplitude contrasts at faults (edge preservation). Consequently, the filter suppresses random noise while retaining essential structural information such as fault offsets and phase discontinuities.

- (4)

Ant-tracking fault-enhancement volumes: Furthermore, the ant-tracking algorithm constructs a composite cost field from coherence, gradients, curvature, and related attributes, and simulates swarm-intelligence behavior to search for optimal fracture/fault pathways. Its basic cost function is

and the ants migrate along paths of minimal cumulative cost, progressively constructing the skeleton of faults. This approach enables automatic linkage of discontinuous fault segments, enhances the detectability of weak faults, and reduces subjectivity in interpretation.

- (5)

Structural mapping and displacement-consistency verification: During structural mapping, fault picks on each interpreted horizon are merged into fault surfaces according to the criteria of “displacement consistency plus geometric continuity.” A crossline–inline closure test is performed using

and when

is small (typically <2–4 ms), the assembled fault surface is considered reliable. For weak normal faults developed on structural flanks, connectivity is further validated by cross-examining curvature extrema, coherence low-value streaks, and ant-tracking enhancement volumes, thereby improving the robustness of structural interpretation.

The result is shown in

Figure 6. The integrated interpretation shows that the Yingshan anticline is overall continuous and complete. Several small-scale normal faults are identifiable at the flanks, potentially connecting deep hydrocarbon source rocks with overlying reservoirs, serving as local vertical migration pathways and lateral sealing units. This fault framework provides spatial constraints for subsequent trap evaluation and favorable-zone delineation.

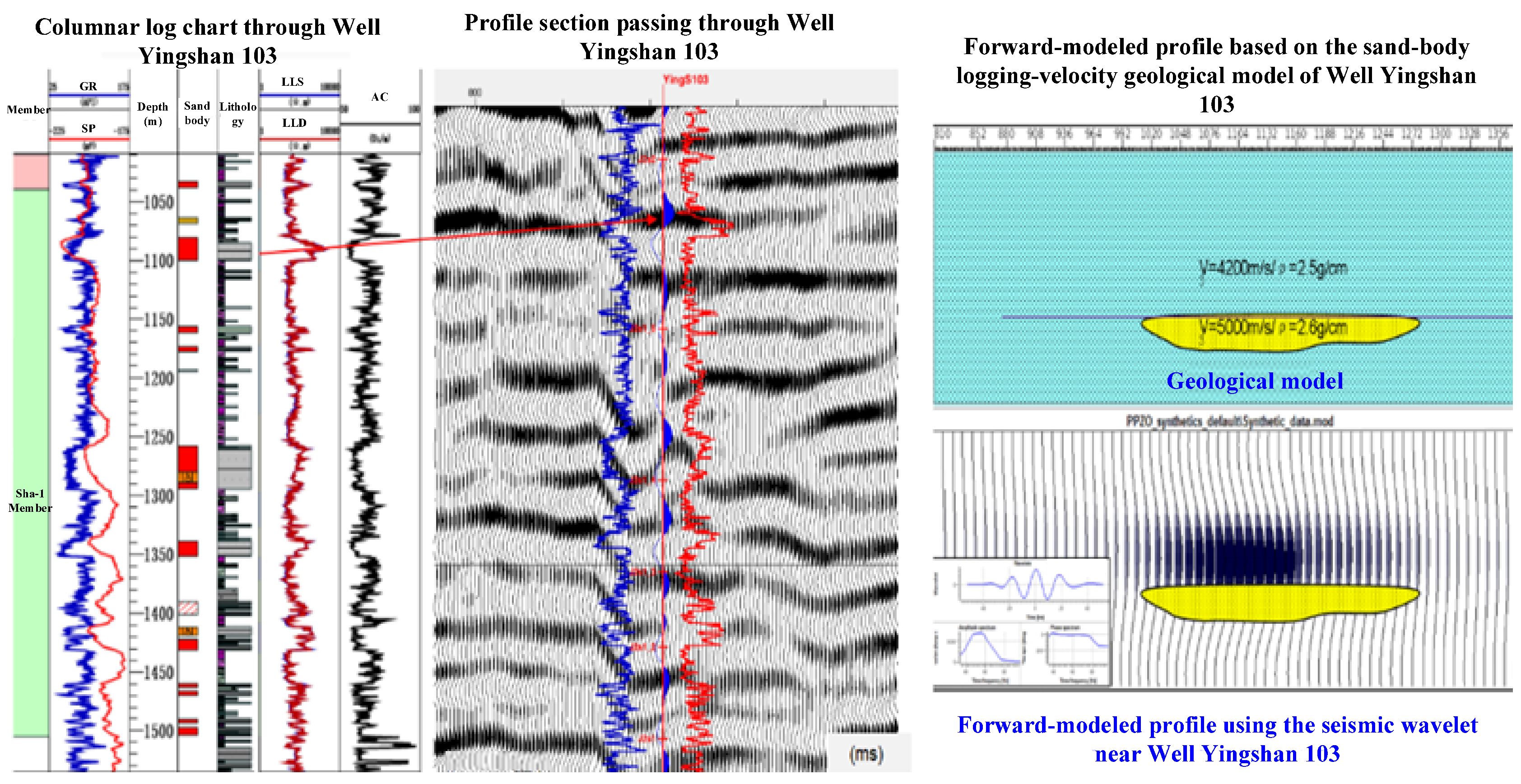

3.3. Seismic Forward Modeling Analysis

To quantify the detectability of typical sand bodies in the Shaximiao Formation under varying frequency, thickness, and lithology contrasts, and to determine thresholds for “bright spot/bipolar” responses, a convolutional seismic forward modeling approach was used. The dominant frequency of the amplitude-preserved 3D seismic data after high-resolution processing is approximately 50–55 Hz. Considering an average P-wave velocity of about 4.6–5.1 km/s for the Shaximiao sand–mud succession, the corresponding quarter-wavelength vertical resolution is on the order of 5–6 m. This vertical resolution is comparable to the thickness of the target fluvial channel sand bodies (typically 2–8 m), indicating that many of the effective reservoir sands lie near or above the tuning thickness. In the horizontal direction, the dense 3D seismic bin size and effective lateral resolution allow delineation of channel belts and sand-prone zones at scales of several tens of meters, which is sufficient to capture the width and lateral continuity of individual channel sand bodies and their stacked belts. Two-dimensional geological models of sand bodies, including semi-lenticular channel sands, bulbous sand bars, and sheet-like sands, were constructed using core and log-derived parameters. Reflection coefficients were calculated from sonic and density logs and then convolved with zero-phase Ricker wavelets [

26] to generate synthetic seismic records, which were subsequently compared and calibrated against actual seismic sections, as shown in

Figure 7.

It should be noted that the seismic forward modeling in this study adopts a convolutional approximation based on P-wave reflection theory, rather than full-waveform or elastic modeling. The forward modeling assumes horizontally layered, laterally homogeneous sand–mud successions with gentle structural relief, which is consistent with the geological characteristics of the Shaximiao Formation in the Yingshan area. Elastic parameters, including P-wave velocity and density, were directly derived from quality-controlled well logs and primarily represent brine-saturated sandstone and mudstone conditions. No explicit fluid-substitution modeling was conducted to simulate gas- and water-saturated scenarios separately, and shear-wave effects, mode conversions, and complex scattering were not explicitly considered.

The sensitivity of the modeled seismic responses was evaluated qualitatively by systematically varying key controlling parameters, including the dominant frequency, sand-body thickness, and sand–mud velocity contrast. The results indicate that seismic responses are most sensitive to the interaction between dominant frequency and bed thickness, particularly near the tuning thickness. At the same time, wavelet phase and bandwidth exert secondary but important control on amplitude stability and polarity. Variations in elastic parameters within the observed log-derived ranges mainly influence amplitude magnitude rather than response type. Because gas saturation would further reduce P-wave velocity and density of sandstones and enhance impedance contrast, the detectability thresholds derived from brine-saturated models should be regarded as conservative estimates for gas-bearing sands.

The modeling’s primary objective justifies this choice: to evaluate thin-bed detectability and tuning-controlled amplitude–polarity responses within the dominant seismic bandwidth of the amplitude-preserved 3D data. The Shaximiao Formation in the Yingshan area is characterized by gentle structural relief, small reflector dip angles, and relatively limited lateral velocity variations at the reservoir scale. Under such conditions, first-order P-wave reflection behavior dominates the seismic response, and the convolutional model provides a robust, physically meaningful approximation for analysis of the thickness–frequency–velocity relationship.

Elastic wave effects, such as mode conversions, transmission losses, and complex scattering, are not explicitly simulated in the forward models and are therefore treated as second-order effects for the purpose of thin-sand detectability analysis. Their cumulative influence is partially embedded in the real seismic data through amplitude-preserving processing and well–seismic calibration. Accordingly, the forward modeling results are not intended to reproduce full seismic wavefields, but rather to establish dataset-consistent thresholds and response patterns that can guide attribute interpretation and inversion within a constrained, interpretable framework.

At key well locations, the forward-modeled seismic responses were explicitly calibrated against well-log-derived sandstone thickness, lithology, and impedance contrasts, as well as available core descriptions of depositional facies. Particular attention was paid to the correspondence between modeled strong-peak/strong-trough bipolar reflections and log-identified sand layers of different thicknesses. This calibration establishes a quantitative relationship between thin-sand thickness and seismic amplitude–polarity expression, providing a physical basis for interpreting similar seismic responses away from wells.

The forward modeling analysis follows classical thin-bed tuning principles; however, the emphasis here is on their dataset-specific implications. Within the parameter ranges of this study—mudstone velocities of approximately 4.0–4.35 km/s, sandstone velocities of approximately 4.6–5.1 km/s, and a zero-phase 50–55 Hz Ricker wavelet—the detectability of thin sand bodies is strongly controlled by the interaction between dominant frequency, velocity contrast, and bed thickness.

It should be noted that the elastic parameters used in the forward modeling are primarily derived from well-log measurements that largely represent brine-saturated sandstone conditions. No explicit fluid-substitution modeling was performed to simulate gas-versus water-saturated scenarios separately. This approach was adopted to define conservative and internally consistent detectability thresholds under a unified reference state.

From a rock-physics perspective, gas saturation would generally reduce both P-wave velocity and bulk density of sandstones, leading to a larger impedance contrast relative to surrounding mudstones. Such changes would enhance reflection amplitude and polarity stability, thereby improving the detectability of thin gas-bearing sands and potentially lowering the effective thickness threshold compared to the brine-saturated case. Therefore, the modeled detectability limits in this study should be regarded as conservative estimates, while gas-charged sand bodies calibrated at producing wells are expected to exhibit stronger seismic responses under equivalent frequency conditions.

Modeling results indicate that sand layers thinner than approximately 2–4 m are dominated by waveform interference, producing unstable or ambiguous amplitude responses. It should be emphasized that the 2–4 m thickness threshold is not an absolute value, but a conditional detectability range controlled by seismic bandwidth, noise level, and wavelet phase. Forward modeling tests show that increasing the dominant frequency or effective bandwidth narrows the tuning zone and improves vertical resolution, allowing thinner sand bodies to generate more stable bipolar amplitude responses. Conversely, reduced bandwidth or elevated noise levels enhance waveform interference, resulting in less stable amplitude expression and a higher effective detectability threshold.

Wavelet phase also plays a critical role. The zero-phase wavelet adopted in this study provides optimal peak–trough symmetry and maximizes tuning sensitivity, thereby stabilizing the polarity of the amplitude near the tuning thickness. In contrast, non-zero-phase wavelets would broaden the interference zone and further reduce the reliability of amplitude anomalies associated with very thin beds. Therefore, under the dominant frequency (~50–55 Hz), signal-to-noise conditions, and zero-phase wavelet assumption of the present dataset, sand bodies thinner than approximately 2–4 m tend to exhibit unstable seismic responses, whereas thicker sands are more consistently detectable. This threshold should be regarded as dataset-specific and conservative, rather than universally applicable.

When the thickness exceeds 6 m, clear strong-peak/strong-trough bipolar reflections emerge, significantly enhancing continuity and interpretability. Increasing sand–mud velocity contrast further stabilizes polarity and amplitude expression, although the critical thickness remains constrained by dominant frequency and wavelet bandwidth.

These forward-modeling results provide quantitative constraints for attribute window selection and anomaly threshold definition, thereby establishing a direct link between seismic response characteristics and interpretable reservoir thickness in subsequent attribute and inversion analyses. On the one hand, attributes such as top-to-bottom peak separation, local dominant frequency, and instantaneous amplitude or “sweetness” can be aligned with forward-modeled responses to determine optimal extraction windows and anomaly thresholds, thereby avoiding misinterpretation of noise or topographic effects as fluvial sand bright spots. On the other hand, the relationship among detectable thickness, dominant frequency, and velocity contrast can be converted into a detectability chart, which allows rapid assessment of the geometric and petrophysical plausibility of attribute anomalies and serves as a prior constraint for subsequent rock-physics–driven inversion. By comparing with actual seismic sections, when zones of strong bipolar amplitude consistent with forward modeling predictions appear and satisfy the frequency–thickness relationship defined in the detectability chart, it can be reasonably inferred that the sand body thickness is approximately 6 m or more and has the potential to form an effective reservoir.

Therefore, seismic interpretation in this study does not attempt to resolve every thin bed individually. Instead, it focuses on identifying sand-prone sublayer packages and effective thickness intervals that are consistent with seismic resolution, forward-modeling constraints, and well calibration, thereby minimizing the risk of over-interpretation beyond seismic limits.

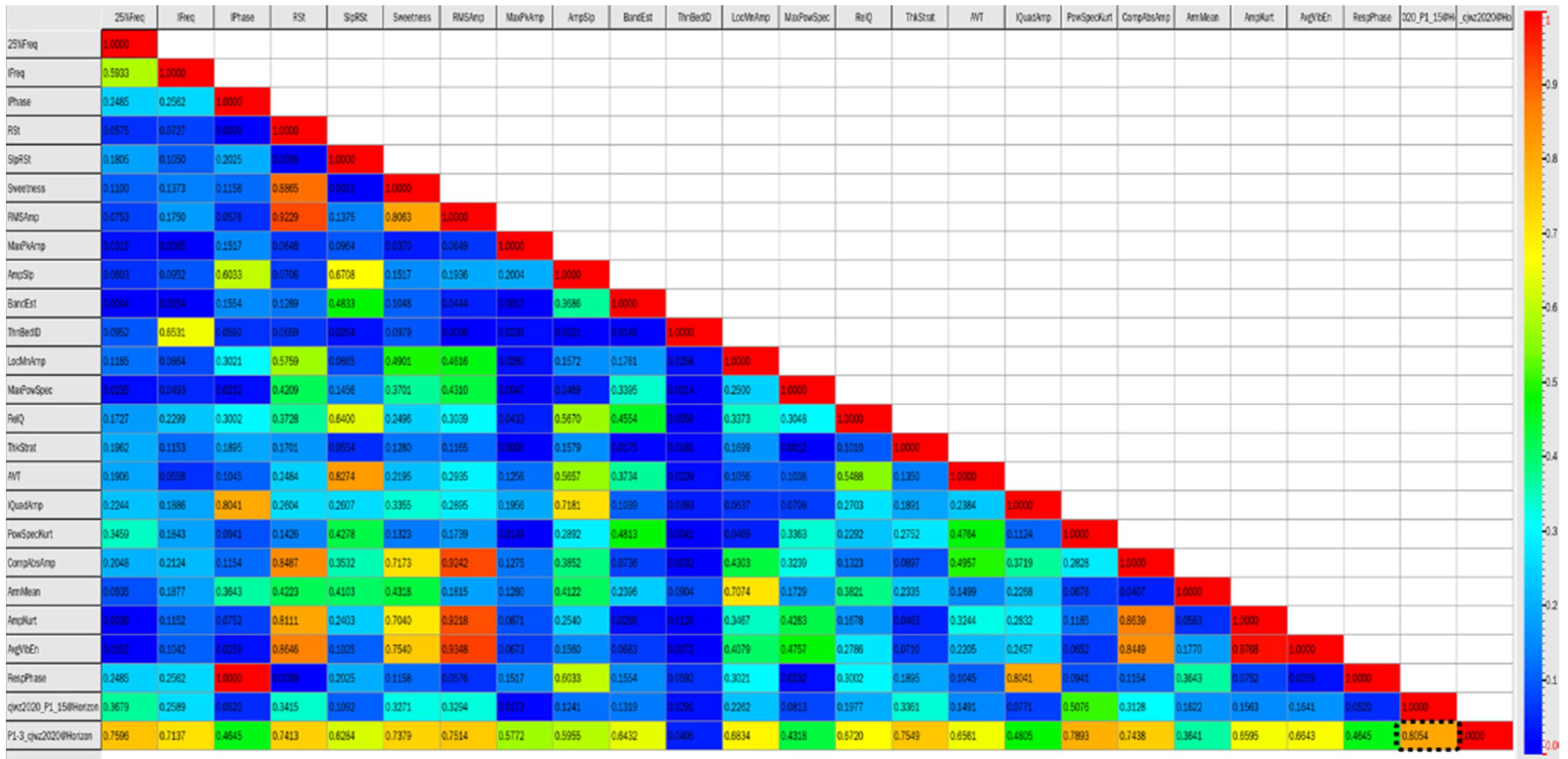

3.4. Seismic Attribute Analysis and Reservoir Prediction

Based on the refined stratigraphic framework and well–seismic calibrated horizons, a “broad-to-fine” attribute selection strategy was implemented for each sublayer of the Sha-1 section in the Shaximiao Formation. Candidate attributes from time-domain amplitude measures (e.g., peak amplitude, RMS amplitude), instantaneous attributes (e.g., envelope, instantaneous frequency, phase), and frequency-domain attributes were first screened using well-based correlation analysis with sandstone relative thickness and porosity. Subsequently, multicollinearity diagnostics were applied to evaluate redundancy among candidate attributes, ensuring that selected attributes exhibit both strong geological sensitivity and low mutual dependence. Attributes with stable correlations with reservoir parameters and minimal redundancy were retained for subsequent analysis.

The results indicate that amplitude-related attributes exhibit stronger sensitivity to vertical tuning responses of thick sandstone bodies (

Figure 8). In particular, RMS amplitude and sweetness provide robust indicators of the relative thickness and connectivity of fluvial channel sandstones in the study area. Sweetness is defined as

where

is the instantaneous amplitude,

is the Hilbert transform, and

denotes the instantaneous frequency. High sweetness values typically correspond to low-frequency, high-energy reflections, often highlighting isolated sandstone bodies within shale-prone backgrounds. Compared with RMS amplitude and other conventional attributes, sweetness more effectively suppresses high-frequency noise and thin-bed interference because the normalization by instantaneous frequency reduces the impact of rapid vertical fluctuations, enhancing the detectability of narrow or discontinuous sand bodies. This property facilitates the identification of narrow channels, distributary channels, and channel-fill sequences that may be obscured in single-attribute maps.

It is well recognized that instantaneous frequency attributes derived from the Hilbert transform are sensitive to noise and phase instability, particularly in thin-bed interference zones. To stabilize instantaneous frequency estimates, several preprocessing and quality-control measures were applied prior to attribute extraction. These include amplitude-preserving processing to enhance signal-to-noise ratio, structure-oriented filtering to suppress random noise while preserving reflector phase continuity, and strict wavelet phase and polarity calibration through well-to-seismic ties. A zero-phase wavelet was consistently adopted to minimize phase-induced frequency artifacts.

Furthermore, instantaneous frequency was not interpreted in isolation. Instead, it was mainly incorporated into the sweetness attribute, where the square root of the instantaneous frequency normalizes amplitude. This formulation effectively suppresses spurious high-frequency fluctuations and reduces sensitivity to local noise, making it more robust for highlighting thin and discontinuous sand bodies. Attribute extraction was conducted within horizon-constrained, layer-parallel windows defined by sequence boundaries and marker beds, thereby avoiding stratigraphic mixing and artificial frequency variations associated with constant-time slicing. Consequently, instantaneous frequency anomalies were considered meaningful only when they were consistent with forward-modeling-predicted frequency–thickness behavior and supported by amplitude and inversion responses.

Within this framework, horizon-consistent attribute slices were extracted for each target sublayer using a layer-parallel window, which was slightly adjusted based on the sublayer thickness to align the tuning peak. Three-dimensional visualization reveals banded zones of positive-amplitude anomalies that occur widely in the core of the anticline and along its extension, consistent with the orientation of the channel system. Areas with high anomaly values typically correspond to predicted thicker sand bodies and may serve as priority candidates for potential sweet spots.

To reduce the non-uniqueness caused by brightness effects, local noise, and topographic interference in single-attribute analysis, multi-attribute integration was implemented under physically meaningful constraints. Sensitive attributes such as RMS amplitude, sweetness, and envelope dominant frequency were fused using fuzzy logic, unsupervised clustering, or statistically weighted learning. Attribute weighting and clustering were guided by their consistency with forward-modeling-derived frequency–thickness responses and their relative sensitivity to effective sandstone thickness, rather than by purely mathematical criteria. This integration strategy emphasizes attributes that jointly reflect geometric continuity and petrophysical contrasts of sand bodies, thereby improving the robustness and geological interpretability of the fused response volumes.

Based on the integrated interpretation of selected and composite attributes, planar maps of sand-body distribution and predicted effective thickness were generated for each sublayer, as shown in

Figure 9. Overall, the sand bodies of the Sha-1 interval exhibit a northeast-trending belt-like distribution with relatively good continuity. In contrast, sand bodies in the Sha-2 interval are generally thinner and less laterally continuous. This difference is mainly attributed to depositional and accommodation controls: Sha-2 formed under relatively limited accommodation space and more variable fluvial energy conditions, leading to discontinuous, isolated channel sands, whereas Sha-1 represents a more stable, channel-dominated depositional system with enhanced accommodation, favoring laterally extensive, stacked sand bodies. Post-depositional modification is considered secondary in controlling the observed continuity contrast. Guided by the forward-modeling-derived detectability thresholds, attribute anomalies were interpreted only when their amplitude, frequency content, and spatial continuity were consistent with the modeled frequency–thickness relationships, thereby reducing uncertainty associated with thin-bed interference.

3.5. Rock-Physics Analysis and Seismic Inversion

Building on qualitative attribute prediction, an integrated rock-physics–seismic inversion approach was introduced to obtain quantifiable, comparable reservoir parameter volumes. First, multi-well log curves were quality-controlled and standardized to establish statistical relationships between lithology and properties. In this area, sandstones exhibit lower acoustic impedance than mudstones, which is controlled by both higher sonic transit times and lower densities [

27,

28]. The impedance contrast between sandstones and mudstones provides the physical basis for distinguishing sand from mud in inversion. Meanwhile, based on regional analogues and local well-log statistics, an empirical porosity–impedance relationship was established, which can be expressed using either an exponential or linear model:

where

,

,

, and

are derived from well-log regression. This relationship constrains the reasonable range and uncertainty of porosity inversion results, providing a reliable prior parameter for subsequent identification of effective thickness and gas-bearing potential.

For inversion, a constrained sparse-spike/sparse-point inversion (SSI/CSSI) approach [

29] was employed, aiming to recover geologically meaningful sparse reflection series while maintaining a good fit to seismic data. The optimization objective is expressed as

where

is the observed seismic trace,

is the estimated wavelet,

is the reflection coefficient series to be estimated, and

is the sparsity constraint parameter.

Absolute impedance volumes are obtained by integrating the reflection coefficient series and adding low-frequency trends derived from multiple wells:

For tight sandstone gas reservoirs, sparse inversion effectively enhances vertical resolution under thin interbeds and limited bandwidth, and multi-trace constraints improve lateral continuity, yielding more reliable sand–mud differentiation and effective thickness estimation.

The inversion workflow includes ① preprocessing and depth–time alignment of well curves; ② estimation and stability verification of wellbore wavelets; ③ joint construction of low-frequency impedance trends from multiple wells; ④ constrained sparse spike inversion to obtain three-dimensional impedance volumes; ⑤ well-based calibration of effective thickness and threshold setting (e.g., integrating impedance upper/lower bounds with net sand identification criteria for net thickness calculation); and ⑥ cross-validation with attribute-fusion volumes to evaluate lateral consistency and uncertainty. Through these steps, the reliability of inversion-derived parameters is jointly constrained by well control, rock-physics relationships, and independent seismic-attribute responses. Uncertainty and sensitivity are mainly addressed by (i) forward-modeling-constrained thickness–frequency relationships that define the detectability limits of thin sand bodies, (ii) comparison and cross-validation between single-attribute, fused-attribute, and inversion-derived results to assess lateral stability, and (iii) well-based calibration using effective thickness and production test data to evaluate prediction consistency. Although a fully probabilistic uncertainty quantification was not performed, these integrated constraints provide a practical and geology-consistent assessment of uncertainty for the quantitative interpretation results.

The inversion results, as shown in

Figure 10, demonstrate a high degree of consistency between the inverted section and the lithology encountered in wells. The sandstone bodies exhibit distinct inversion responses, with smooth lateral transitions and high reliability. Moreover, the channel sand bodies correspond to low-impedance facies, showing good agreement with the effective intervals revealed by the wells.