Abstract

The deep brine reservoirs in the Jianshishan area of the Qaidam Basin are abundant in strategic mineral resources. Traditional extraction methods suffer from insufficient reservoir energy and low recovery efficiency, while CO2 flooding technology offers a new solution integrating brine development and CO2 sequestration. However, the reservoir comprises three typical lithologies (calcareous mudstone, laminated mudstone, and massive sandstone) with distinct mineral compositions and structural characteristics and the mechanisms by which CO2–brine–reservoir reactions affect their pore structures remain unclear. This study conducted laboratory simulation experiments combined with multiple analytical techniques to investigate the evolutionary characteristics of the three lithologies under CO2 action. The results show that (1) calcareous mudstone has the strongest dissolution effect, with porosity increasing from 6.25% to 9.29% (an increase of 48.6%) and permeability increasing from 0.0012 mD to 0.0511 mD (an increase of 41.6 times); (2) laminated mudstone shows a trend of “first improvement, then deterioration”, with porosity initially rising to 11.84% and then slightly decreasing, and permeability decreasing from 0.0042 mD to 0.0036 mD; and (3) massive sandstone has stable mineral composition, with porosity increasing from 10.74% to 11.63% (an increase of 8.3%) and permeability fluctuating slightly between 0.0028 and 0.0032 mD. This study reveals that lithological mineral composition and structural characteristics are core factors controlling pore structure evolution, providing theoretical and experimental support for optimizing differentiated CO2 flooding schemes for deep brine reservoirs.

1. Introduction

The Qaidam Basin, renowned as a strategic hub for mineral resources in China, hosts abundant deep brine reservoirs in the Jianshishan area that are enriched with critical strategic minerals [1,2,3]. These mineral resources play an indispensable role in supporting national industrial development and safeguarding resource security, making the efficient extraction of deep brine a research focus in the fields of resource development and energy utilization [4,5,6]. However, traditional brine extraction methods are plagued by inherent limitations: the insufficient energy of deep reservoirs leads to sluggish fluid flow, resulting in low brine recovery efficiency and failure to fully exploit the resource potential. This not only causes the waste of valuable mineral resources but also restricts the economic and environmental benefits of brine development projects [7].

In recent years, CO2 flooding technology has emerged as a revolutionary solution that integrates brine extraction and CO2 geological sequestration [8,9,10,11,12]. By injecting CO2 into deep brine reservoirs, this technology not only supplements reservoir energy to enhance brine recovery but also achieves long-term safe sequestration of CO2, aligning with the global goals of carbon neutrality and emission reduction [13]. This dual-benefit characteristic has made CO2 flooding a promising direction for sustainable development of deep brine resources. Nevertheless, deep brine reservoirs in the Jianshishan area exhibit significant lithological heterogeneity [1,4,14,15]. These lithologies differ drastically in mineral composition—such as varying contents of soluble carbonate minerals, stable quartz, and clay minerals—and structural characteristics, including pore type, connectivity, and initial porosity–permeability. These differences are expected to lead to distinct reaction behaviors between CO2, brine, and reservoir rocks (i.e., CO2–brine–reservoir reactions) during flooding.

The CO2–brine–reservoir reaction is a complex physicochemical process involving CO2 dissolution, carbonic acid formation, mineral dissolution–precipitation, and ion exchange. These reactions directly alter the reservoir’s pore structure—including porosity, permeability, and pore connectivity—which in turn affects brine migration and extraction efficiency [16,17,18,19,20]. However, the current understanding of how lithological differences regulate pore structure evolution during CO2 flooding remains limited. The lack of systematic research on these mechanisms hinders the formulation of targeted CO2 flooding schemes, leading to inefficient resource extraction and potential reservoir damage in practical applications.

Based on this, this study focuses on calcareous mudstone, laminated mudstone, and massive sandstone from the deep brine reservoirs in the Jianshishan area of the Qaidam Basin. Laboratory experiments were conducted to simulate CO2–brine–reservoir reactions during CO2 flooding. CO2 is injected into the deep brine reservoir as a displacement medium, which not only supplements reservoir energy to improve brine recovery, but also achieves long-term geological storage of CO2 through dissolution and mineralization reactions, realizing the dual goals of resource development and carbon emission reduction. Combined with analytical techniques including low-field NMR, porosity–permeability testing, and XRD, the pore structure evolution characteristics, mineral composition changes, and brine occurrence-state responses of the three lithologies under CO2 action were systematically studied. The dominant factors and micro-mechanisms controlling pore structure evolution of reservoirs with different lithologies were revealed, providing theoretical basis and experimental support for optimizing CO2 flooding schemes for deep brine reservoirs in the Jianshishan area.

2. Samples and Experiments

2.1. Samples

Core samples of different lithologies were collected from the middle-deep brine reservoirs in the Jianshishan area of the Qaidam Basin to investigate the effects of CO2 flooding for brine extraction on the pore structure of brine reservoirs with different lithologies. Sample 1 and sample 2 were obtained from the YaZK0701 well in the Yahu area. Sample 3 was obtained from the upper and lower Youshashan Formation in the JianZK1001 well in the Jianshi Mountain area. Using wire cutting (Taizhou Taizhong CNC Machine Tool Co., Ltd., Taizhou, China), core samples were processed into small core columns with a diameter of 2.5 cm and length of 6 cm along the bedding direction. Each small core column was further cut into three segments with lengths of 4 cm, 1 cm, and 1 cm. The two 1 cm short core segments were used for mineral composition testing before and after the experiment, respectively.

2.2. Experiments

2.2.1. CO2–Brine–Rock Reaction Experiment

Two cylindrical core samples (4 cm and 1 cm in length) were placed in a high-pressure reactor (Haian Petroleum Scientific Research Instrument Co., Ltd., Nantong, China), and formation brine was injected to completely submerge the cores, with a water–rock volume ratio of approximately 3:1. After standing for 24 h, supercritical CO2 (99.99%, Linde, Shanghai, China) was injected into the reactor, and the pressure was maintained at 10 MPa. The temperature of the entire reaction system was 75 °C. After 5 days of reaction, the 4 cm core sample was removed for porosity, permeability, and NMR testing. After testing, the above process was repeated to continue the CO2–brine–rock reaction experiment. When the cumulative reaction time reached 10 days and 30 days, the core samples were removed for porosity, permeability, and NMR testing. The 1 cm cylindrical core sample was only taken out when the cumulative reaction time reached 30 days, and then was rinsed with water (Milli-Q system, Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), dried, and crushed for mineral composition analysis. The evolutionary trend of the pore structure obtained in the experiment can be used as a preliminary qualitative judgment of the long-term burial process.

2.2.2. XRD Experiment

XRD experiments were performed on the 1 cm core segment A (before reaction) and 1 cm core segment B (after reaction). First, the samples were dried in an oven (DHG-9140A, Shanghai Yiheng Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at 60 °C for 24 h to ensure complete drying. Then, the samples were crushed and ground to more than 200 meshes. Finally, the fully mixed sample powder was pressed into tablets to prepare test samples, which were tested using an Empyrean DY1411 X-ray diffractometer (PANalytical, Almelo, The Netherlands). The instrument operated at a voltage of 40 kV and current of 40 mA. The test results were analyzed using JADE 6.0 software, and the mineral content was calculated by the whole-pattern fitting method.

2.2.3. Porosity and Permeability Testing

To ensure the integrity of core samples for subsequent experiments, porosity and permeability testing were performed in accordance with the national standard GB/T 34533-2023 [21] “Determination Methods for Rock Porosity and Permeability”. First, after drying the standard plunger core samples, a helium porosimeter (Quantachrome Instruments, Boynton Beach, FL, USA) was used to measure the particle volume. Combined with the total volume measured by a vernier caliper and the dry weight measured by an electronic balance, the effective porosity of the core samples was calculated. Permeability was determined using a steady-state gas permeability meter (Haian Petroleum Scientific Research Instrument Co., Ltd., Nantong, China). Under set confining pressure and temperature conditions, a stable gas pressure difference was applied across the core sample. After the gas flow reached a steady state, the inlet and outlet flow rates and pressure values were accurately measured. Finally, the gas permeability of the core sample at the specified average pressure was calculated according to Darcy’s law. Each sample was tested in parallel three times, and the average value was taken as the final result to ensure data repeatability and accuracy. The pulse attenuation method permeability tester (model: HP-PAM-100) was used, with a measurement limit of 10−6 mD.

2.2.4. Core Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Testing

Low-field NMR technology was used for systematic characterization of core samples. All samples were tested directly after the CO2–brine–rock reaction experiment. Measurements were performed using a MicroMR02 (NIUMAG Corporation, Suzhou, China) NMR spectrometer under a constant magnetic field of 0.5 T, with a CPMG pulse sequence used to collect NMR spin-echo signals. The scanning parameters were as follows: temperature = 32 °C; waiting time (TW) = 8000 ms; echo time (TE) = 0.1 ms; number of scans = 32; receive gain = 100%; number of echoes = 12,000. Finally, the collected original echo train data were inverted and fitted to obtain the transverse relaxation time (T2) spectrum, which reflects the pore structure and fluid distribution of the core samples. This spectrum not only intuitively presents the distribution characteristics of pores of different sizes but also quantitatively distinguishes the volumes of bound fluid and movable fluid in the core samples by setting a standard T2 cutoff value, providing key basis for reservoir physical property evaluation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Changes in Mineral Composition

After CO2 injection into the deep brine reservoir, CO2 dissolves in water. Most of the dissolved CO2 exists in molecular form, and only a small amount reacts with water to form carbonic acid, which disrupts the original thermodynamic equilibrium of the brine reservoir. Carbonic acid reacts with ions in the brine and minerals in the rocks, mainly including carbonate mineral dissolution and precipitation, as well as silicate mineral dissolution. The reaction rate is affected by CO2 solubility, brine composition, and reservoir rock composition. These series of reactions impact the ion concentration, mineral composition, and rock physical properties of the aquifer.

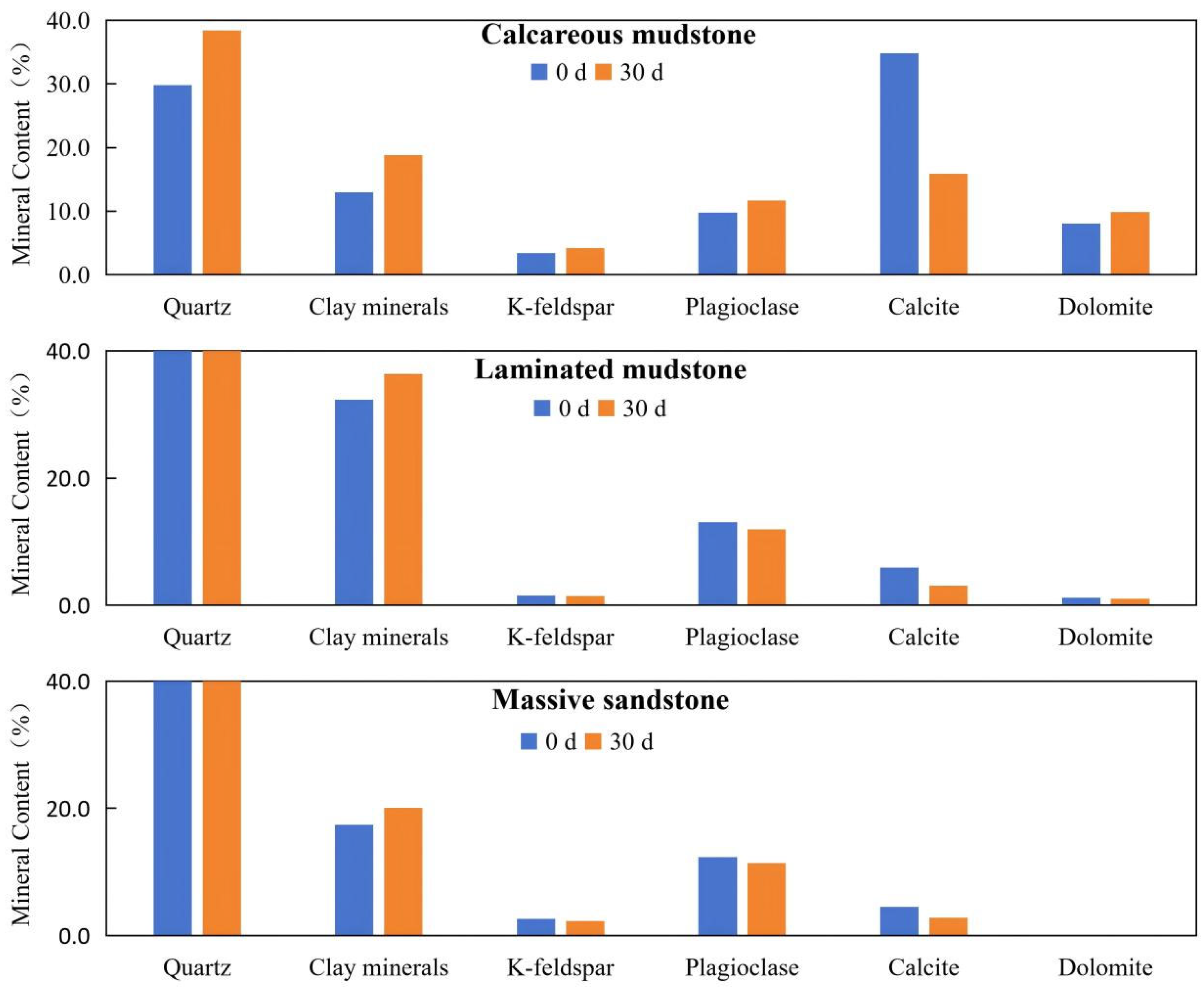

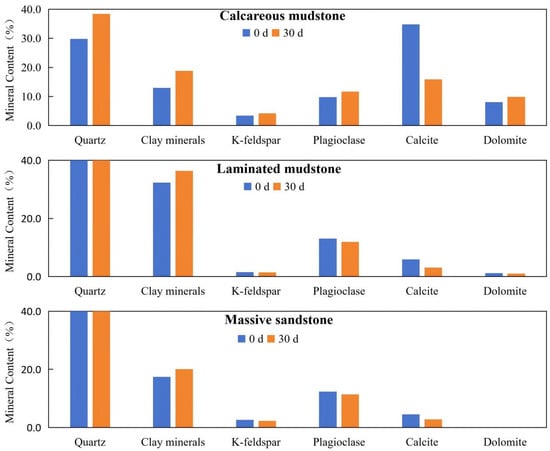

In terms of mineral composition before and after the reaction, calcareous mudstone showed the most significant changes, while laminated mudstone and massive sandstone exhibited no obvious changes. After the reaction, the calcite content in calcareous mudstone decreased significantly, and the contents of quartz and clay minerals increased slightly. In contrast, the quartz content of laminated mudstone and massive sandstone with low calcite content showed no obvious changes (Table 1, Figure 1), indicating that the change in quartz content in calcareous mudstone samples was caused by the significant decrease in calcite content.

Table 1.

Mineral composition before and after CO2–brine–rock reaction.

Figure 1.

Mineral composition variations of three lithologies before (0 d) and after (30 d) CO2–brine–rock reaction. Notes: This figure displays the mineral content (in percentage) of calcareous mudstone, laminated mudstone, and massive sandstone, measured before (0 d, blue bars) and after 30 days (30 d, orange bars) of CO2–brine–rock reaction. The minerals analyzed include quartz, clay minerals, K-feldspar, plagioclase, calcite, and dolomite. Significant decreases in calcite content are observed in calcareous mudstone and laminated mudstone after the reaction, indicating the dissolution of carbonate minerals induced by CO2–brine–rock interaction. In contrast, the mineral composition of massive sandstone remains relatively stable, with only minor changes in calcite content.

Numerous studies have shown that carbonate mineral dissolution and precipitation are usually the main reactions in the CO2–brine–rock system, while quartz hardly reacts. This leads to significant changes in carbonate mineral content, with corresponding changes in quartz content. Therefore, in this study, quartz was used as a reference to identify the real changes in mineral composition before and after the reaction by analyzing the ratio of other mineral contents to quartz content.

For the three samples with different mineral compositions, the calcite/quartz ratio decreased significantly before and after the experiment, with the highest rate of change compared to other parameters, indicating that calcite dissolution was the most obvious reaction in the CO2–brine–rock system. The calcite/quartz ratio of calcareous mudstone samples showed the largest decrease, reflecting extensive calcite dissolution. Although the dolomite content increased from 8.1% to 9.9%, the dolomite/quartz ratio still decreased slightly, indicating minor dolomite dissolution. The K-feldspar/quartz and plagioclase/quartz ratios decreased slightly, indicating dissolution of feldspar minerals. The clay minerals/quartz ratio increased slightly, indicating the formation of a small amount of clay minerals in the experimental system.

3.2. Changes in Porosity and Permeability

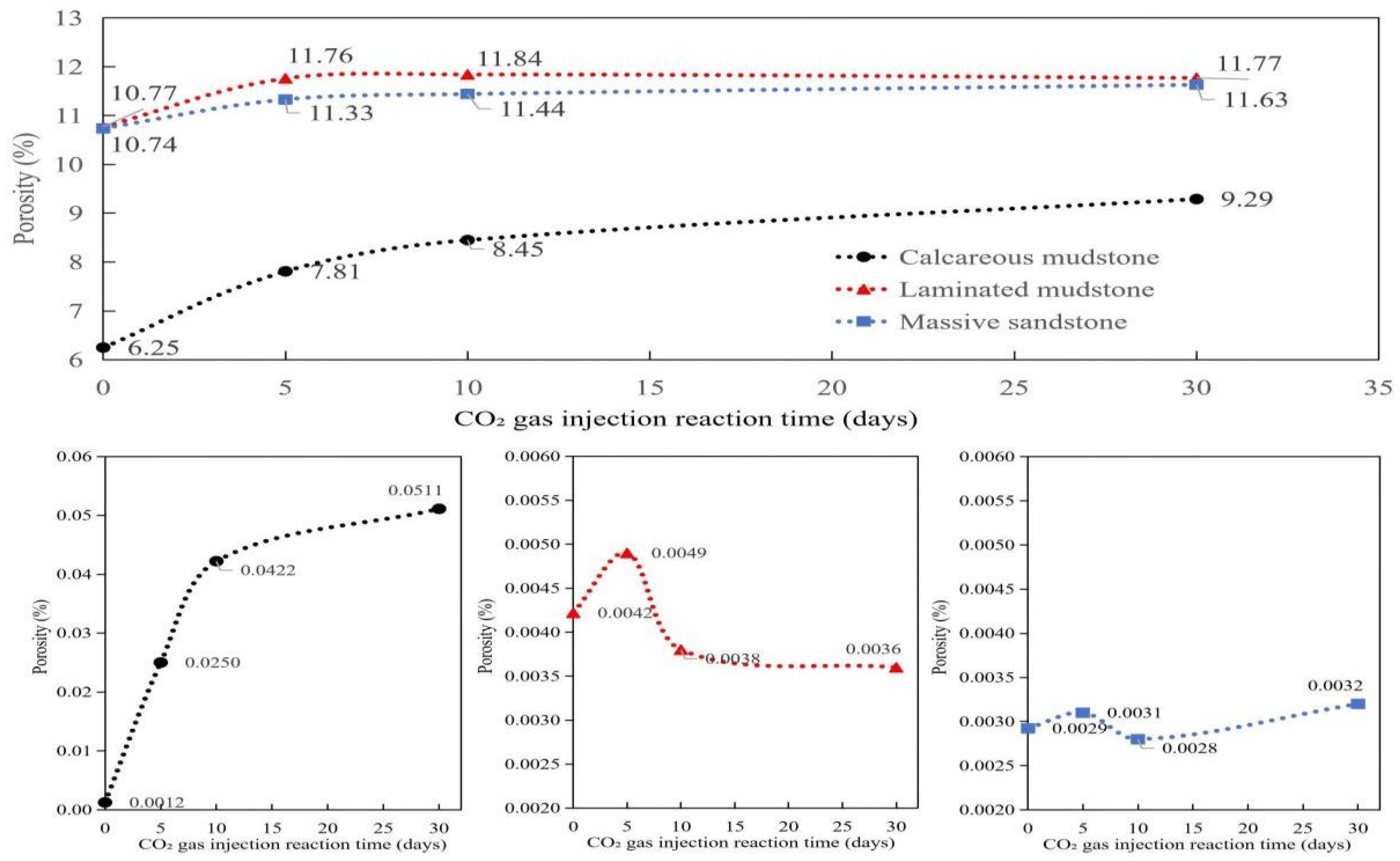

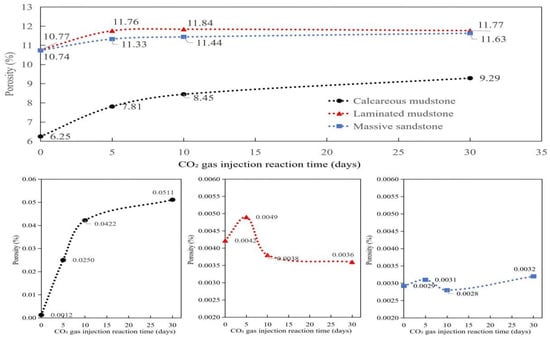

Due to differences in mineral composition and initial pore structure, different lithologies exhibited distinct responses to CO2–brine–rock reactions. The porosity and permeability at different reaction times are shown in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Table 2.

Porosity and permeability before and after CO2–brine–rock reaction.

Figure 2.

Porosity and permeability evolution of three lithologies with reaction time during CO2–brine–rock interaction. Notes: The lithologies include calcareous mudstone, laminated mudstone, and massive sandstone. The porosity is expressed as percentage (%), and the permeability is in millidarcy (mD). The reaction time is the duration of CO2–brine–rock reaction. Calcareous mudstone exhibits the most significant increases in both porosity and permeability, while massive sandstone maintains relatively stable porosity and permeability values throughout the reaction process.

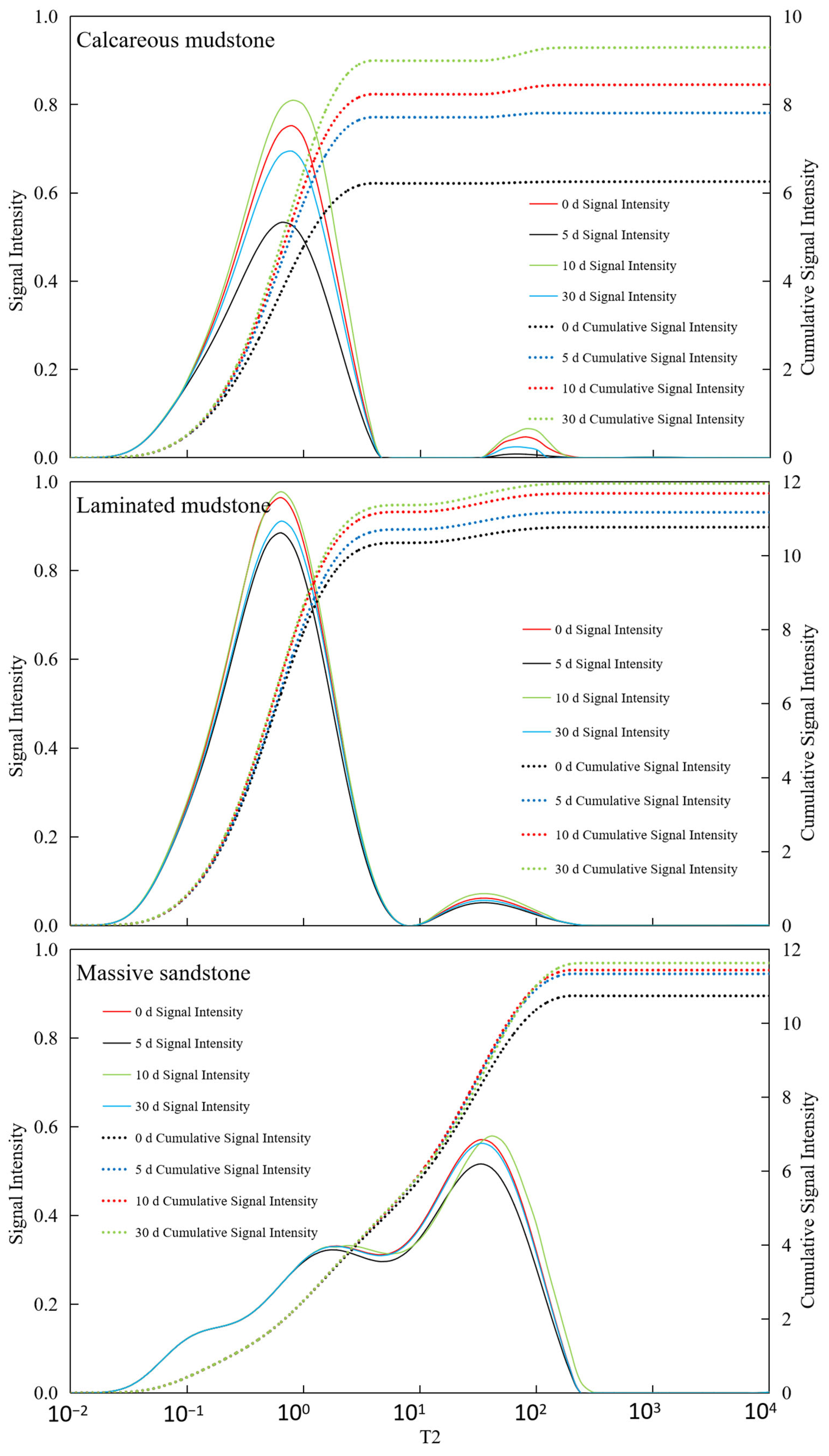

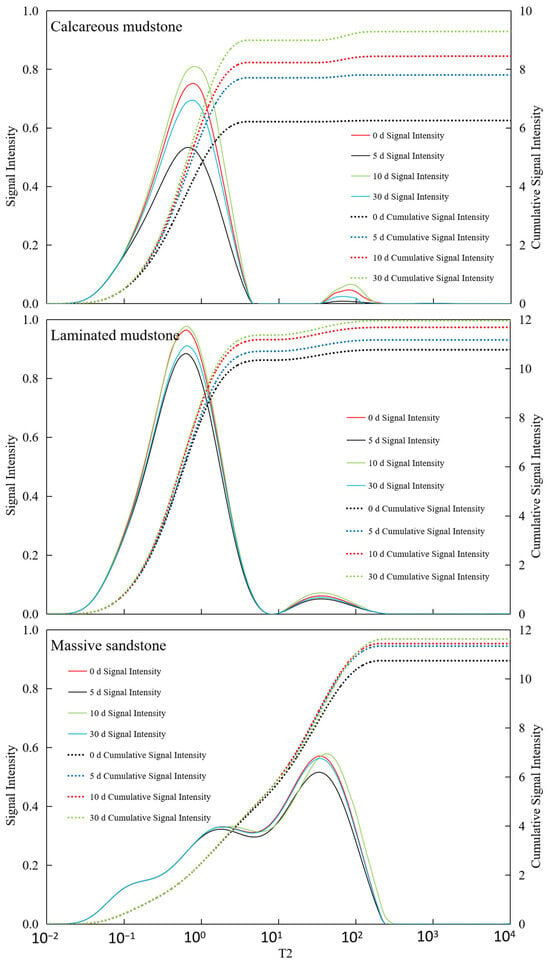

As shown in Figure 3, Calcareous mudstone: Pore structure was significantly improved, and reservoir storage and seepage capacity were greatly enhanced. Calcareous mudstone showed the most positive and significant response to CO2 flooding. NMR data clearly indicated that the cumulative amplitude of pore fluid increased continuously from 6.25 before the reaction to 9.29 after 30 days of reaction, reflecting a substantial increase in total effective pore volume. This result was confirmed by porosity and permeability data: porosity increased significantly from 6.25% to 9.29%, and permeability jumped by two orders of magnitude from an extremely low 0.0012 mD to 0.0511 mD. These positive changes were mainly attributed to its high carbonate mineral content (calcite content of 34.8% before the reaction). The acidic fluid formed by CO2 dissolution in brine effectively dissolved minerals such as calcite, not only expanding the original micropores but also potentially dredging or generating new seepage channels, thereby simultaneously optimizing reservoir porosity and permeability. This indicates that CO2 flooding has strong modification potential for calcareous mudstone reservoirs.

Figure 3.

NMR T2 spectra of three lithologies at different CO2–brine–rock reaction durations. Notes: The figure presents nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) T2 relaxation spectra of calcareous mudstone, laminated mudstone, and massive sandstone, measured at 0 d, 5 d, 10 d, and 30 d of CO2–brine–rock reaction. The horizontal axis (T2) corresponds to pore size (smaller T2 indicates smaller pores), while the left vertical axis represents signal intensity (proportional to the volume fraction of pores with corresponding sizes) and the right vertical axis denotes cumulative signal intensity (representing the total pore volume fraction). The spectra show that calcareous mudstone exhibits a more significant shift toward longer T2 (larger pores) after reaction, reflecting the evolution of pore structure induced by CO2–brine–rock interaction.

Laminated mudstone: Pore structure first improved then deteriorated, with a risk of pore blockage. The reaction process of laminated mudstone was relatively complex, showing an obvious “first enhancement, then inhibition” trend. NMR cumulative signals and porosity data increased in the early stage of the reaction (0–10 days), indicating that mineral dissolution also increased pore space initially. However, in the later stage (10–30 days), porosity decreased slightly from 11.84% to 11.77%, and permeability continued to decline from 0.0049 mD to 0.0036 mD, significantly lower than the initial value. This phenomenon reveals that in addition to constructive mineral dissolution, destructive processes occurred during CO2 action. It is likely that while acidic fluid dissolved minerals, it released fine particles such as clay minerals, which blocked key seepage throats during fluid migration. Changes in small-pore-size signals in the later stage of the NMR T2 spectrum may reflect this blocking process. This indicates that for reservoirs with high clay mineral content such as laminated mudstone, although CO2 flooding can increase total pore volume, it may cause permeability damage due to fine particle migration, requiring careful risk assessment in practical applications.

Massive sandstone: Pore structure was moderately optimized, and reservoir storage and seepage capacity increased stably and slightly. The reaction of massive sandstone was relatively mild. Its NMR cumulative signal increased slowly from 10.74 to 11.63, indicating that CO2 action brought a certain increase in pore space, but the increase was much smaller than that of calcareous mudstone. Correspondingly, its porosity also increased slightly from 10.74% to 11.63%. However, its permeability changed little during the entire reaction process, fluctuating within a narrow range of 0.0028 to 0.0032 mD, without showing the leapfrog growth observed in calcareous mudstone. This is related to its mineral composition: although it also contains a small amount of carbonate cement (calcite content of 4.5% before the reaction), its framework particles are dominated by quartz with a stable structure. CO2 dissolution mainly targets limited cement, having little impact on the overall pore structure, especially the large pores and throats that play a key role in seepage. Therefore, CO2 flooding can improve the storage performance of massive sandstone reservoirs to a certain extent, but the effect on enhancing seepage capacity is not significant.

3.3. Changes in Brine Occurrence State

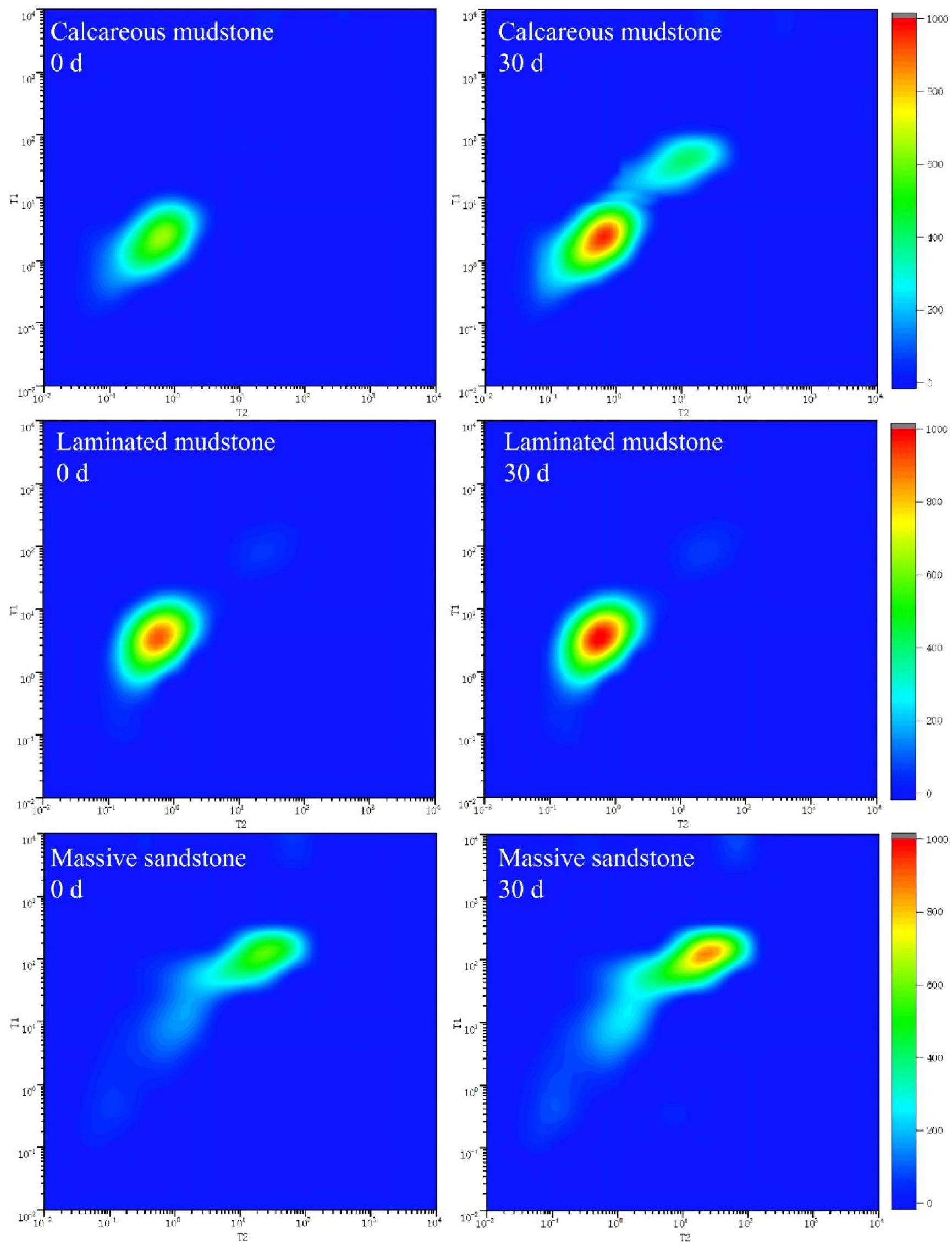

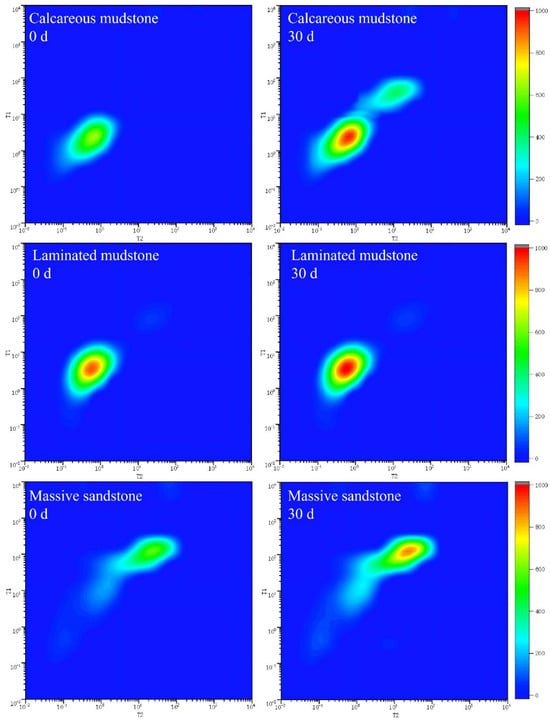

From the 2D NMR data of calcareous mudstone, the signals of saturated water samples before the reaction were mainly distributed in the ranges of T2 = 1–100 ms and T1 = 10–1000 ms, forming a continuous signal band along the T1~T2 diagonal (Figure 4), indicating that the pore structure was dominated by medium-connected medium-micropores. Brine was mainly stored in narrow pore spaces ranging from nanometers to micrometers, with poor fluidity. After 30 days of reaction, the overall signal intensity increased significantly, especially the appearance of obvious signal clusters in the long relaxation region of T2 > 100 ms, indicating extensive dissolution of carbonate minerals during the reaction. Dissolution expanded some pores to form larger-scale pores or pore throats, improving pore connectivity and expanding brine storage space from micropores to medium and large pores. Porosity and permeability data showed that the porosity of calcareous mudstone increased continuously from 6.25% in the initial stage to 9.29% at 30 days, and the permeability increased sharply from 0.0012 mD to 0.0511 mD, with an increase of more than 40 times. These significant changes not only expanded the total brine storage space but also, more importantly, formed a better-connected pore network, enabling brine originally confined in narrow pores to flow in a wider range. The brine storage space transformed from isolated micropores to a connected medium-large pore system.

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional NMR relaxation spectra of three lithologies before (0 d) and after (30 d) CO2–brine–rock reaction. Notes: This figure presents 2D nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) relaxation spectra of calcareous mudstone, laminated mudstone, and massive sandstone, obtained before (0 d) and after 30 days (30 d) of CO2–brine–rock reaction. The color intensity (scaled by the right-side color bar) represents NMR signal intensity, corresponding to the volume fraction of pores with specific relaxation properties. For calcareous mudstone, the spectra show an additional signal cluster after 30 d, indicating the formation of new pores induced by reaction. In contrast, the spectra of laminated mudstone and massive sandstone exhibit only minor changes, reflecting relatively stable pore structures during the reaction.

The 2D NMR signals of laminated mudstone were highly concentrated in the extremely short relaxation regions of T2 < 10 ms and T1 < 10 ms, with low overall signal intensity, indicating an extremely dense pore structure dominated by isolated micropores and interlayer slit pores. Pore connectivity was poor, brine storage space was limited, and fluidity was weak. This structure showed a weak response to brine–rock reactions. After the reaction, the signal distribution showed no obvious changes, indicating that the reaction mainly expanded existing pores rather than forming new ones. Porosity and permeability data further verified this characteristic: porosity increased slowly from 10.77% to 11.77%, with an increase of only 9.3%; permeability increased from 0.0042 mD to 0.0049 mD in the early stage of the reaction and then decreased to 0.0036 mD, with an overall change of less than 7%. These changes indicate that laminated mudstone has a certain inhibitory effect on CO2–brine–reservoir reactions. Mineral dissolution mainly occurs inside existing pores without forming obvious new pore channels. Although the brine storage space expanded slightly, it remained limited by the bedding structure, and fluidity improvement was not obvious.

The pore structure change of massive sandstone during CO2–brine–reservoir reaction was between that of calcareous mudstone and laminated mudstone, showing a moderate improvement trend. Before the reaction, the maximum NMR signal intensity of massive sandstone was 887.35, and the total signal intensity was similar to that of laminated mudstone, but pore connectivity was relatively better. Brine was stored in intergranular pores and a small amount of cement pores, with uniform distribution of storage space. After the reaction, the maximum signal intensity increased to 1313.28, and the total signal intensity increased by 48.00%, the same as that of laminated mudstone, but the number of effective pores did not change, indicating that the reaction mainly acted on cement dissolution and pore expansion. Porosity and permeability data showed that the porosity of massive sandstone increased steadily from 10.74% to 11.63%, with an increase of 8.3%; permeability fluctuated slightly between 0.0028 and 0.0032 mD, with an overall change of less than 13%. This change characteristic is derived from the particle-supported structure of massive sandstone: CO2–brine–reservoir reactions mainly dissolved the carbonate cement between particles, expanding existing intergranular pores without damaging the particle framework structure. Therefore, pore connectivity remained stable, and brine storage space expanded uniformly based on the original pore system. Fluidity improved slightly but moderately, forming a more stable brine storage environment.

Combined with the 2D NMR spectra and porosity–permeability data of the three lithologies, the effects of CO2–brine–reservoir reactions during CO2 flooding for brine extraction on reservoir pore structure and brine storage space are closely related to lithological structural characteristics. Due to its high content of soluble carbonate minerals and loose structure, calcareous mudstone underwent fundamental changes in pore structure after the reaction, with brine storage space transforming from closed micropores to a connected medium-pore system. Laminated mudstone has low carbonate content, and the reaction only limitedly expanded existing pores, with no obvious change in brine storage space. Due to the stable particle framework of massive sandstone, the reaction mainly dissolved cement, leading to uniform expansion of brine storage space. The core mechanism of this difference is that the mineral composition of lithologies determines the material basis for reactions.

4. Conclusions

This study explores the pore structure evolution of three typical lithologies (calcareous mudstone, laminated mudstone, and massive sandstone) in the Jianshishan deep brine reservoir under CO2 flooding via laboratory simulations and multi-technical analysis. The key conclusions are as follows:

- The mineral composition of lithologies is the core factor regulating pore structure responses to CO2 flooding. Calcareous mudstone, rich in soluble carbonate minerals, undergoes extensive mineral dissolution induced by CO2-derived acidic fluid, leading to significantly improved porosity and permeability, enhanced pore connectivity, and expanded brine storage space to medium and large pores.

- Laminated mudstone, characterized by high clay mineral content and low carbonate content, exhibits a “first improvement, then deterioration” pore structure evolution. Early mineral dissolution slightly increases pore space, while late-stage migration of fine particles causes pore throat blockage, resulting in reduced permeability.

- Massive sandstone, dominated by stable quartz particles, experiences mild cement dissolution under CO2 action. This leads to a modest increase in porosity but no significant change in permeability, as the stable particle framework maintains the overall pore structure stability. Sandstone, dominated by stable quartz particles, experiences mild cement dissolution under CO2 action. This leads to a modest increase in porosity but no significant change in permeability, as the stable particle framework maintains the overall pore structure stability.

- Overall, the findings clarify the differentiated pore structure evolution mechanisms of multi-lithology reservoirs under CO2 flooding, providing theoretical support for formulating targeted and efficient CO2 flooding schemes for deep brine reservoir development. According to different lithological characteristics, The CO2 injection rate and pressure can be adjusted to maximize the improvement of brine recovery and CO2 storage efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C. and J.J.; Date Curation, X.Z., L.C. and T.G.; Investigation, X.Z., Z.W. and S.Z.; Methodology, J.C. and T.P.; Resources, Z.W.; Supervision, J.C. and J.J.; Validation, D.F., S.Z. and T.G.; Visualization, T.P.; Writing—original draft, X.Z.; Writing—Review & Editing, J.C., D.F. and Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFC2904301), the Shaanxi Provincial Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. 2024SF-YBXM-622), and the Shaanxi Provincial “Sanqin Talents” Program for Outstanding Young Talents.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all colleagues who provided assistance during the experiments and data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Deliang Fu and Liaoliao Cui were employed by the company Shaanxi Coal Geology Group Co., Ltd., Xi’an. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Meng, F.; Zhou, L.; Yuan, X.; Miao, W.; Yuan, W. Formation of deep brine in the Qaidam Basin, north Qinghai-Xizang Plateau: Constraints from Ca isotopes and geochemistry. Ore Geol. Rev. 2025, 183, 106676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hu, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z. Hydrogen and Oxygen Isotopes as Key Monitoring Indexes for Deep Confined Brine Mining: Insights from Mahai Salt Lake, Qaidam Basin. Water 2025, 17, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.Q.; Gao, C.L.; Cheng, A.Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; He, X. Geomorphic, hydroclimatic and hydrothermal controls on the formation of lithium brine deposits in the Qaidam Basin, northern Tibetan Plateau, China. Ore Geol. Rev. 2013, 50, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Cui, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, N.; Yao, F.; Wang, Q.; Hu, S. Exploration Methods for Potassium-Rich and Lithium-Rich Brine in the Mihai Mining Area, Qaidam Basin, Qinghai. Geol. J. 2025, 60, 1986–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, Q.; Li, Q.; Du, Y.; Qin, Z.; Wei, H.; Shan, F. The Source, Distribution, and Sedimentary Pattern of K-Rich Brines in the Qaidam Basin, Western China. Minerals 2019, 9, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, J.; Xia, Y. Risk Prediction of Gas Hydrate Formation in the Wellbore and Subsea Gathering System of Deep-Water Turbidite Reservoirs: Case Analysis from the South China Sea. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Fu, D.; Pan, T.; Han, Y.; He, M.; Guo, T.; Meng, X.; Zhang, S.; Jia, J.; Zhang, X.; et al. Key problems and countermeasures of high efficiency mining of deep brine. Geol. China 2025, 52, 1268−1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Liu, D. Effect of supercritical CO2 injection capillary pressure on salt precipitation in deep brackish water layer. Saf. Environ. Eng. 2015, 22, 61−65. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Li, Y.; Ma, X.; Atrens, A.; Ni, H. Modeling Study of Enhanced Thermal Brine Extraction Using Supercritical CO2. Geol. Sci. Technol. Inf. 2014, 33, 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, Q.; Jiang, B.; Su, C. Review on technologies of geological resour-ces exploitation by using carbon dioxide and its synchronous storage. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 50, 84−95. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, G.; Fang, Q.; Tan, K.; Lv, J. Well group layout method for supercritical CO2 enhanced deep brine mining. J. Univ. South China (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 31, 47−52. [Google Scholar]

- Huq, F.; Haderlein, S.B.; Cirpka, O.A.; Nowak, M.; Blum, P.; Grathwohl, P. Flow-through experiments on water-rock interactions in a sandstone caused by CO2 injection at pressures and temperatures mimicking reservoir conditions. Appl. Geochem. J. Int. Assoc. Geochem. Cosmochem. 2015, 58, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ansari, U. From CO2 Sequestration to Hydrogen Storage: Further Utilization of Depleted Gas Reservoirs. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chen, X.; Shi, Z.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Zuza, A.V.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Wang, Z. Cenozoic Kinematic Evolution of the Northern Tibetan Plateau: Implication for the Tectonic Setting of Deep Brines Mineralization in the Southwestern Qaidam Basin. Tectonics 2025, 44, e2024TC008525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, N.; Shen, L.; Li, R.; Liu, C.; Jiao, P.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, X. Contribution of deep material sources to shallow potash formation of the Quaternary Mahai Salt Lake in the Qaidam Basin: Evidence from isotopes and trace elements. Ore Geol. Rev. 2024, 171, 106166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Wei, Y.; Gao, S.; Ye, L.; Liu, H.; Zhu, W. Simulation Experiment of CO2-Water-Rock Reaction Seepage Capacity in Gas Reservoirs with Different Lithology. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 24916–24931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Du, Y.; Duan, Y.; Peng, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, S.; Sepehrnoori, K. Microscopic experimental study on the reaction of shale and carbon dioxide based on dual energy CT mineral recognition method. Fuel 2024, 371, 131874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Wang, Y.; Rui, Z.; Chen, B.; Ren, S.; Zhang, L. Assessing the combined influence of fluid-rock interactions on reservoir properties and injectivity during CO2 storage in saline aquifers. Energy 2018, 155, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiwagi, H.; Shikazono, N. Water-rock reaction in sequestration of carbon dioxide in sedimentary basin. J. Groundw. Hydrol. 2005, 47, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cao, L.; Lv, M.; Li, C.; Sun, Q.; Wu, M.; Xu, C.; Dou, J. Effects of Crosslinking Agents and Reservoir Conditions on the Propagation of Fractures in Coal Reservoirs During Hydraulic Fracturing. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 34533-2023; Determination Methods for Rock Porosity and Permeability. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.