Abstract

The degradation of mercapto organic contaminants is highly important for safety and environmental protection since the specific chemical properties and the strong nature of S-containing bonds can make them less susceptible to traditional degradation mechanisms compared to other types of organic bonds. Thus, degradation of mercapto organic contaminants often requires catalysts with specific bandgap properties to ensure efficient generation of reactive species and appropriate redox potential alignment. Hence, in this work, we prepared bandgap-engineered semiconductor photocatalysts based on nanoparticles of different silica-doped spinel cobalt ferrite [SiO2/CoFe2O4] (abbreviated as SiMCoF) [SiMCoF-1, SiMCoF-2, and SiMCoF-3] and characterized them by different analytical techniques. Since the dopant composition in a heterogeneous semiconductor material has important effects on its photocatalytic efficiency because adjusting the dopant profile can modulate impurity bands and enhance optical properties, which is crucial for the oxidative degradation of organic pollutants. Results from TEM, SEM, and their EDS analysis revealed that increased SiO2 content showed improved surface area in the matrix, facilitating the increased absorption of oxygen impurities. This is further observed by the higher Rmax values presented in AFM of SiMCoF-3 (139 nm) compared to SiMCoF-2 (116 nm) and SiMCoF-1 (8.78 nm), depicting its larger effective surface area (100 µm2), which in turn increases the active binding sites in the matrix. The Raman spectrum and XRD pattern of SiMCoF-3 showed various crystal planes with different atomic arrangements and a smaller crystallite size, leading to varying affinities for oxygen impurities. As a result, the optical bandgap decreased from 3.42 eV to 2.89 eV for SiMCoF-3, which is attributed to the quantum confinement effects caused by the smaller particle size and the dispersion of silica particles in the cobalt ferrite matrix. Thus, SiMCoF-3 showed elevated degradation performance without using any potential oxidants over the degradation of mercapto organic contaminants such as 2-mercaptobenzothiazole, 2-mercaptobenzimidazole, and thiophenol under sunlight irradiation compared to other ferrites, and showed better results than Fenton’s reagent.

1. Introduction

Broadband semiconductors are generally considered to be inactive or have very limited activity under direct sunlight because they can only absorb a small fraction of the solar spectrum, and they suffer from rapid recombination of photogenerated charge carriers [1]; however, suitable surface engineering allows these materials to be transformed into efficient photocatalysts under sunlight [2,3]. Surface-modified wide-bandgap semiconductor (WBGS)-based photocatalysts present a promising strategy to achieve greater potential to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) and manipulate intrinsic molecular interactions to favor a specific reaction pathway to degrade organic pollutants in water [4,5]. Recent investigations have been devoted to developing more efficient WBGS photocatalysts by using techniques like introducing defects or doping, phase transition, and using plasmonic nanoparticles to capture more of the solar spectrum [6]. Specifically, doping with other elements can modify the band structure of a semiconductor–photocatalyst, which can lead to new energy levels within the bandgap, enabling the absorption of lower-energy photons. Usually, WBGS like titanium dioxide (TiO2) and zinc oxide (ZnO2) have large band gaps; however, structural modification of these materials to change their band gaps is difficult primarily due to their inherent high chemical stability, strong Ti-O and Zn-O bond energies, and a propensity to form specific types of defects. Current studies show tuning of the optical bandgap in hybrid materials like spinel metal ferrite (MFe2O4; M = Ni, Cu, Zn, etc.), allowing them to be used in a wide range of applications such as optical and magnetic fields [7,8]. For example, reducing the particle size in the semiconductor materials increases their surface properties and also increases the bandgap due to the quantum confinement effect, where electrons and holes are confined to a smaller space, leading to a rise in the energy required to excite an electron from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB) [9]. Thus, the challenge of finding suitable mechanisms for enhancing surface properties and tuning the optical bandgap should be addressed. Introducing dopants can control carrier concentration and alter energy levels, thereby tuning the bandgap. For example, increasing the ability to adsorb impurities like oxygen on the surface [10], which can act as trapping centers helping to separate photogenerated electrons and holes and reducing their recombination, can improve the photocatalytic activities of ferrites over all [11,12,13]. However, the specific effects depend on the concentration of oxygen doping, since higher concentrations of oxygen impurities can act as recombination centers, which hinder charge transfer, reducing photocatalytic efficiency; therefore, controlling oxygen concentration is crucial for optimizing the photocatalytic performance of metal ferrites [14]. Despite different experimental conditions, the oxygen impurities only change in concentration but can not be eliminated from the catalyst matrix because they are beneficial to the structural stability of the catalyst [15]. Since the semiconductor defects, especially the shallow donors (or acceptors), are strongly correlated with carrier concentration, which is a critical factor affecting the semiconductor/metal interfacial properties [16]. For example, when the semiconductor/metal contact is the Schottky type, the change in electron concentration in the semiconductor may change the Schottky barrier height [17]. Since oxygen impurity is a shallow electron donor in a catalyst and its concentration strongly depends on experimental conditions, the controversial photoelectrochemical performances of the catalyst interface may be ascribed to the concentration change of oxygen impurities [18]. Therefore, constructing heterojunctions with metal spinel ferrites [19] and introducing oxygen vacancies [20] are effective strategies for enhancing charge transfer and boosting the performance of its photocatalytic activity because the synergistic effect of these two approaches creates an optimal interface for charge-carrier separation and transport. Since the presence of a suitable bandgap (about 2.1 eV) and band-edge positions, the spinel metal ferrites can produce ROS under sunlight irradiation, which is beneficial for practical applications [21]. Silica doping of metallic spinel ferrites has been studied and found to be effective in reducing particle agglomeration by reducing interactions between them [22]. It has also been found that silica doping of the ferrite keeps crystalline structure virtually unaltered, while other parameters are significantly affected, particularly optical/electrical properties [23,24].

On the other hand, compounds containing a mercapto group (thiol group, -SH) are used in various industrial processes, particularly as rubber accelerators in vulcanization and as corrosion inhibitors in cooling systems [25], leading to their role as industrial pollutants, their toxicity, and their interaction with heavy metals in the environment [26]. Thiols can undergo rapid abiotic oxidation to form disulfides in the environment, changing the chemical structure, potentially forming new compounds that may also be resistant to further biodegradation [27,28]. Also, the specific chemical properties and the strong nature of S-containing bonds can make them less susceptible to typical enzymatic degradation mechanisms compared to other types of organic bonds. Degradation of mercapto organic contaminants is difficult primarily because of the mercapto group (-SH) that hinders biodegradation for microorganisms, especially when compared to other functional groups like the hydroxyl group (-OH), making them relatively persistent in the environment [29]. Degradation methods for thiol-containing contaminants generally involve biological, chemical, and physical processes, often used in combination. For example, aerobic mixed cultures and specific bacterial strains like Staphylococcus capitis have shown the ability to utilize 2-mercaptobenzothiazole (MBT) as a carbon and energy source [30,31]. Fungal peroxidases, such as the DyP4 enzyme, can efficiently degrade specific mercapto compounds like MBT in water [32]. Though some mercapto compounds like 2-mercaptobenzothizaole are toxic to microorganisms, requiring pre-treatment with chemical methods like irradiation to improve biodegradability before a biological approach is viable [33]. On the other hand, novel adsorbents like MOFs and carbon nanomaterials are also being researched for their high efficiency and unique properties in mercaptan removal. For example, bimetallic Zn/Ni-MOF can effectively remove mercapto compounds from wastewater [34]. However, their primary drawbacks include limited practical applicability due to synthesis challenges of MOFs, poor water stability, and the small pore sizes (micropores) that can be easily blocked by the contaminants themselves during the adsorption process [35,36]. In addition, adsorption is highly dependent on specific environmental conditions such as pH, temperature, nutrients, and limited to only biodegradable compounds, and there is potential for incomplete degradation into more toxic intermediate products [37]. Since the degradation of mercapto (thiol) contaminants often produces harmful byproducts, some of which can be more toxic or more persistent than the original compound, this leads to significant concerns in environmental remediation and human health [38]. In that sense, catalyst-assisted advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) are highly effective for degrading mercapto contaminants because they generate strong, non-selective hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and other reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can break down the persistent and complex chemical bonds found in these pollutants [39]. Since degradation of mercapto organic contaminants often requires catalysts with specific bandgap properties to ensure efficient generation of reactive species and appropriate redox potential alignment, the high VB potential of broad bandgap catalysts enables the direct and efficient oxidation of organic molecules to form hydroxyl (•OH-) radicals. The high CB position allows for the formation of oxide (•O2−) radicals, which are crucial for the complete degradation and mineralization of complex organic sulfur compounds into less harmful substances [40].

In this study, to unravel the effects of oxygen impurity concentration in the metal ferrites that were prepared using different concentrations of SiO2, and their synergetic effects on photocatalytic property in the removal of mercapto organic contaminants such as 2-mercaptobenzothiazole (MBT), 2-mercaptobenzimidazole (MBI), and thiophenol (TP) under direct sunlight irradiation were investigated.

2. Experimental Design

2.1. Materials and Instruments

Iron(III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3.6H2O, 97%), cobalt chloride hexahydrate (CoCl2.6H2O, 98%), tetraethyl orthosilicate (Si(OC2H5)4, 98%), polyethylene glycol (<0.5%), and anhydrous ammonia (NH3, ≥99.98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. For all the synthesized SiMCoF particles, phase determination of the as-prepared powders was performed using a Powder X-ray diffractometer of D8 Advance Da Vinci diffractometer equipped with a Bruker AXS-Germany in a theta–theta configuration with CuKa (l = 1.54 Å). Raman spectra were registered using a Thermo Scientific DXR Raman Confocal Microscope, Waltham, MA, USA with a spatial resolution of approximately 2 μm and a confocal depth of 2 μm. The morphology and crystallinity of the samples were analyzed by a Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM, JEOL-Japan 2010, 200 kV) equipped with a LaB6 thermionic cannon (40 kV acceleration), and the composition of elements was estimated by Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectrometry (EDS, microanalyzer resolution 61.0 eV) by employing the Cliff–Lorimer Ratio Thin Section quantitative method with silicon (K series) as standard. The Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) studies were performed on a JEOL JSM-Japan 5900-LV connected with a tungsten thermionic canon camera working at 20.0 kV; the composition of the SiMCoF was carried out using an OXFORD-ISIS EDS probe for which the sample (200 μL, 0.1 mM) was dropped onto a carbon-coated film, and then the solvent was allowed to evaporate before the scanning was performed. Also, the size of the synthesized nanoparticles was determined by an atomic force microscope (AFM, Bruker-Germany Multimode 8-HR; Scan Rate: 1 Hz; Scan Size: 10 µm) in the tapping mode. A UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer Lambda 25, USA) was employed to determine the electronic properties of SiMCoF particles and monitor the oxidation kinetics of mercapto contaminants. During the degradation of the contaminants, sunlight intensity was measured by using a pyranometer (SperScientific, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, Model: 850009).

2.2. Degradation Study of Mercapto Contaminants

The degradation of different mercapto contaminants (Scheme 1) was performed in the presence of SiMCoF nanoparticles under sunlight irradiation (86 to 98 W/m2). For the experiment, 0.1 mg of catalyst was used to oxidize each mercapto contaminant (0.05 mM) in an aqueous medium at room temperature and at neutral pH. The concentration changes in mercapto contaminants were monitored by UV–Vis; the absorbance intensity changes in each substrate were recorded in the range between 200 and 400 nm at different time intervals during 1 h. After completion of oxidation, the reaction solution was centrifuged (10 min, 10,000 rpm) to separate the solid catalyst from the reaction medium, and it was washed several times with deionized water for reuse. The photocatalytic efficiencies of the metal ferrites were compared with those obtained without light irradiation (dark state), without using a catalyst (photolysis), using H2O2 alone, and using Fenton reagent as an oxidant under the same experimental conditions and oxidation kinetics for all the mercapto contaminants. Fenton’s reagent is typically prepared fresh by mixing ferrous sulfate (FeSO4.7H2O) with hydrogen peroxide in distilled water in a 1:10 (mass/mass) ratio, adjusting the pH of the experiment by adding NaOH or H2SO4 (0.1 mol L−1).

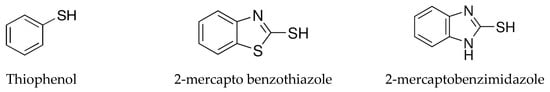

Scheme 1.

Mercapto contaminants.

2.3. Preparation of SiMCoF Particles

In the first step, cobalt ferrite nanoparticles (CoFe2O4) were prepared using the chemical coprecipitation method reported in the literature [41]. An analytical grade of iron(III) chloride hexahydrate [FeCl3.6H2O] and cobalt chloride hexahydrate [CoCl2.6H2O] were used as precursors. For the reaction, a 2:1 ratio of FeCl3.6H2O (0.2 mol L−1) and CoCl2.6H2O (0.1 mol L−1) was initially added to a solvent mixture of distilled water and ethylene glycol (1:1, 50 mL). To this mixture, sodium acetate (0.5 mol L−1) was added; the resulting mixture was then sonicated for 30 min, transferred to a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave, and heated at 180 °C for 20 h. The dark precipitate obtained was centrifuged and washed with distilled water.

In the second step, silica doping was carried out by the following procedure [42] with modifications. For this, an aqueous solution containing CoFe2O4 was added to the aqueous ammonia (NH4OH 25%) solution containing different concentrations (0.1 to 1 mol L−1) of tetraethyl orthosilicate [Si(OC2H5)4], and the mixture was stirred vigorously for 24 h at 60 °C. A dark precipitate that formed was centrifuged and calcinated at 400 °C.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Surface Morphology

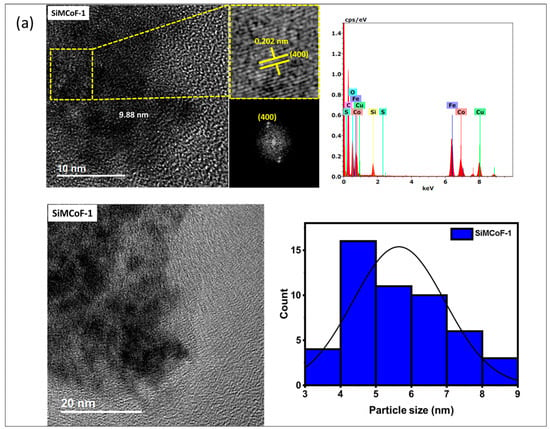

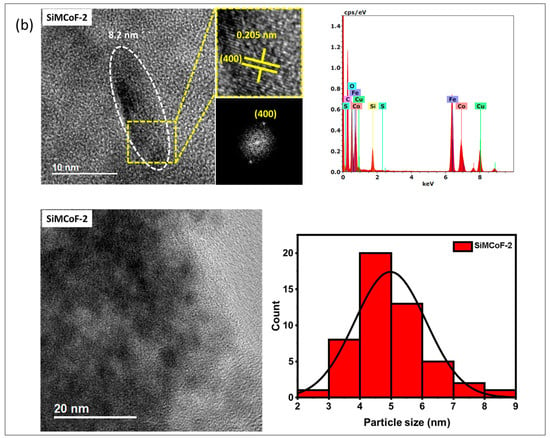

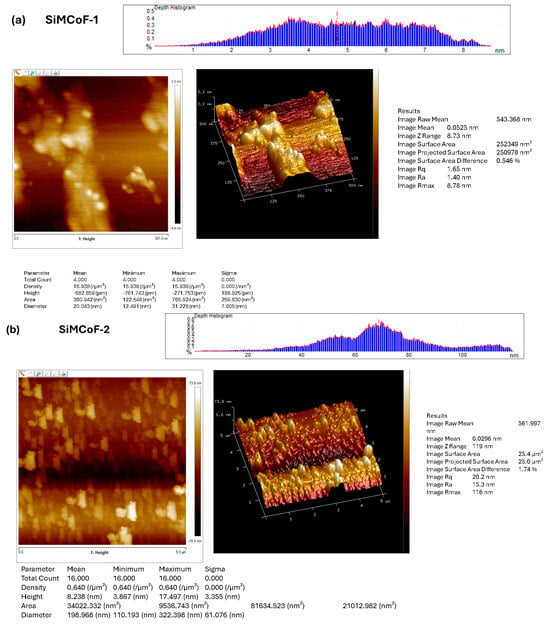

TEM and SEM analyses were performed to determine the morphology and size distributions of all SiMCoF samples.

TEM analysis: The TEM analysis of the synthesized nanoparticles, along with their size distributions, is shown in Figure 1. The TEM images were analyzed using freeware ImageJ V 1.44 to determine the particle size, allowing for the measurement of the average diameters of 100 nanoparticles. The analysis revealed that the average nanoparticle diameter was approximately 9.8 nm, 8.2 nm, and 6.4 nm for SiMCoF-1 (Figure 1a), SiMCoF-2 (Figure 1b), and SiMCoF-3 (Figure 1c), respectively. The increase in SiO2 content had a significant effect on the microstructure of the samples; for example, a higher concentration of SiO2 in SiMCoF-3 promotes the formation of a highly porous morphology and leads to finer particles. This observation coincides with D values determined by the Debye–Scherrer formula in XRD results; increased silica content showed a reduced particle size. In addition, the cubic spinel structure of spinel ferrite was observed as (400) planes in SiMCoF-1 and SiMCoF-2 with d-spacing values of 2.02 Å and 2.05 Å, respectively; however, SiMCoF-3 showed a typical d-spacing value of 1.426 Å associated with the (511) plane, which was further confirmed with its XRD pattern.

Figure 1.

TEM micrographs analysis of (a) SiMCoF-1, (b) SiMCoF-2, and (c) SiMCoF-3.

TEM-EDX analysis: The composition of elements in all the metal ferrites was determined by EDS by measuring around 20 spots in the TEM grid, and it showed the presence of Si, Co, Fe, and O in each compound, indicating the self-assembly of each element in all SiMCoF samples (see Table 1). Furthermore, EDS data indicates that the oxygen content was presented in the following order: SiMCoF-1 (63.57%) < SiMCoF-2 (73.6%) ˂ SiMCoF-3 (78.85%), suggesting that oxygen embedded within the cobalt ferrite matrix in SiMCoF-3 facilitates internal electric fields that can drive charge carriers to different locations, reducing their recombination rate and increasing photocatalytic efficiency compared to SiMCoF-1 and SiMCoF-2.

Table 1.

TEM-EDS chemical composition analysis for different SiMCoF nanoparticles.

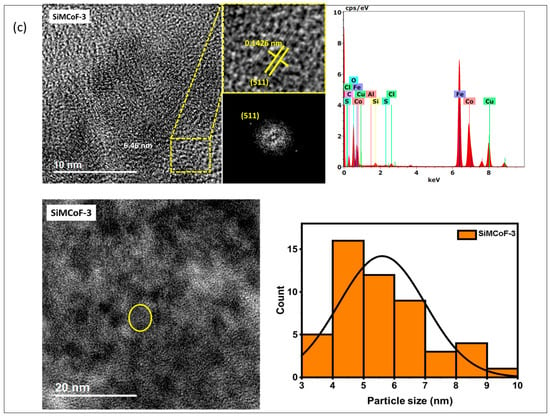

SEM analysis: Figure 2 (Figure 2a–c) shows SEM images of all the SiMCoF particles. In general, there is a uniform surface morphology for all SiMCoF, though there is no significant change in the general background of the image of the surface of SiMCoF upon the increase in SiO2. However, for SiMCoF-3 (Figure 2c), it is possible to observe that the surface structure of bigger clusters has an increased porous nature. The immobilization of SiO2 in the cobalt ferrite matrix partially unblocked the porosity of the surface due to the increased presence of oxygen impurities in the outer surface, as can be observed by EDS analysis of SEM; the increase in SiO2 content resulted in a higher measured oxygen content.

Figure 2.

SEM images and EDS analysis of (a) SiMCoF-1, (b) SiMCoF-2, and (c) SiMCoF-3.

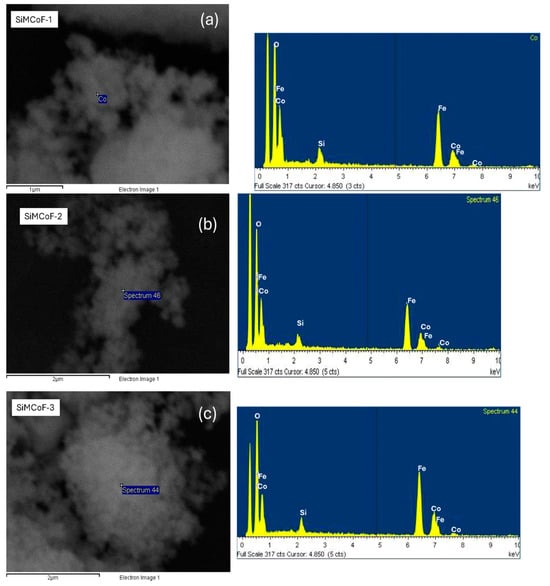

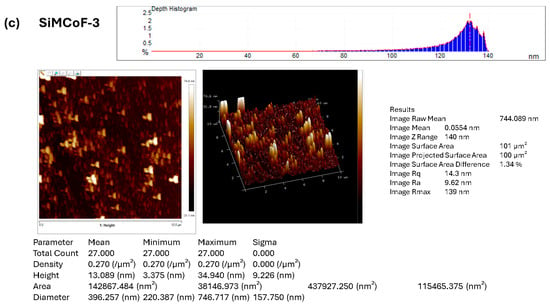

3.2. AFM Analysis

Atomic force microscopy was employed to investigate and visualize the change in the surface morphology upon the integration of different concentrations of SiO2 on the cobalt ferrite matrix, as presented in Figure 3. AFM images show significant morphological changes with increased SiO2. The roughness of the surface is generally characterized by the root-mean-square roughness (Rmax, Rq) and average roughness (Ra) values.

Figure 3.

AFM image analysis of (a) SiMCoF-1, (b) SiMCoF-2, and (c) SiMCoF-3.

The observed higher Rmax (maximum roughness depth) presented in SiMCoF-3 (139 nm) (Figure 3c) compared to other SiMCoF-2 (116 nm) (Figure 3b) and SiMCoF-1 (8.78 nm) (Figure 3a) depicts a rougher surface. Rmax reflects its larger effective surface area (100 µm2) available for the absorption of pollutant molecules and light, providing more active sites for the photocatalytic reaction [43]. In addition, this increased catalytic surface can enhance turbulence intensity close to the surface, which translates to an increase in the mass transfer rate of contaminants to the catalyst surface, thus improving efficiency and its ability to capture and absorb incident radiation energy, similar to the principle behind the enhanced emissivity of rough surfaces in optics due to increased effective area and light-trapping effects. These results are further confirmed by the Zrange value. For SiMCoF-3, it was observed to be 140 nm, while SiMCoF-2 showed 119 nm, and SiMCoF-1 showed 8.73 nm, which directly indicates enhanced light absorption and increased active sites on the surface of SiMCoF-3 [44].

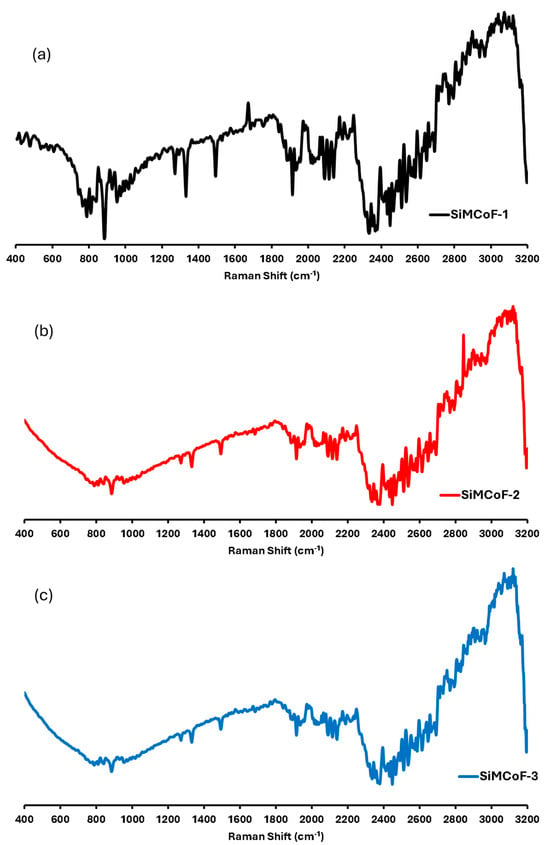

Raman spectroscopy: Figure 4 shows the micro-Raman spectrum of different SiMCoF samples. SiMCoF-1 (Figure 4a) and SiMCoF-2 (Figure 4b) show similar spectra to one another; however, SiMCoF-3 (Figure 4c) shows quite different shift signals since increased silica content showed significant surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) signals of SIMCoF-3, indicating the stable nanostructured metallic surface present. Agreeing with the results obtained from AFM, Raman scattering (SERS) signals of SIMCoF-3 often expose various crystal planes with different atomic arrangements and bonding site densities, leading to varying affinities for oxygen impurities [45]. The presence of more structural defects, steps, and dangling bonds on a rough surface increases the number of available sites for oxygen atoms to incorporate into the material’s lattice.

Figure 4.

Raman shifts for (a) SiMCoF-1, (b) SiMCoF-2, and (c) SiMCoF-3.

For example, the Raman spectrum of SiMCoF-3 presented a well-defined signal in the range of 800–900, 1250, 1380, and 1900 cm−1, which are characteristic of the cubic spinel structure for Fe2O4 [46]. The band at 2100 cm−1 was due to the Co2+/Co3+ redox process, indicating that SiO2 substitution induced Co2+ deficiency and increased Co3+ concentration in the cubic domain, which accelerates oxygen mobility that is beneficial for the catalytic activity [47].

Also, oxygen-vacancy-related signals were observed at 565, 589, and 626 cm−1; and the bands at 2250 cm−1 in all the SiMCoF particles were attributed to a non-degenerate Raman inactive longitudinal optical mode of SiO2 due to the presence of oxygen vacancy in the samples [48]. Since lattice expansion and contraction occur in finite-size particles, there is a larger number of defective sites with increased oxygen vacancies. In addition, the excitation bands in the range 2400–3000 cm−1 corresponded to the defect-induced (D) band and (G) band, respectively, which may have been raised during the annealing of the samples at 400 °C. These bands became sharper and finer in SiMCoF-3, indicating that increased SiO2 content induces phase transformation on the surface of the cobalt ferrite matrix. These results are consistent with the results obtained from the XRD patterns of different SiMCoF particles.

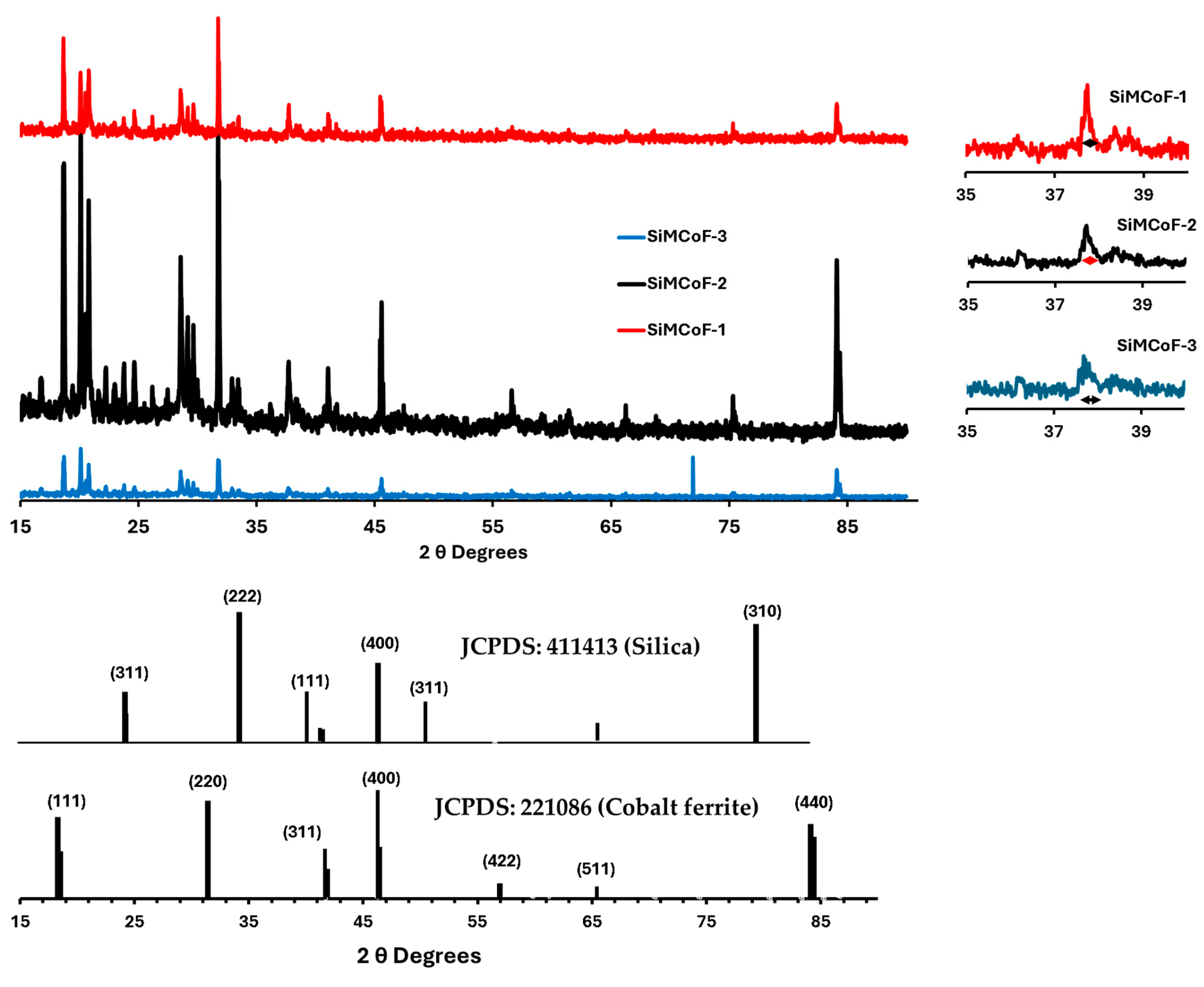

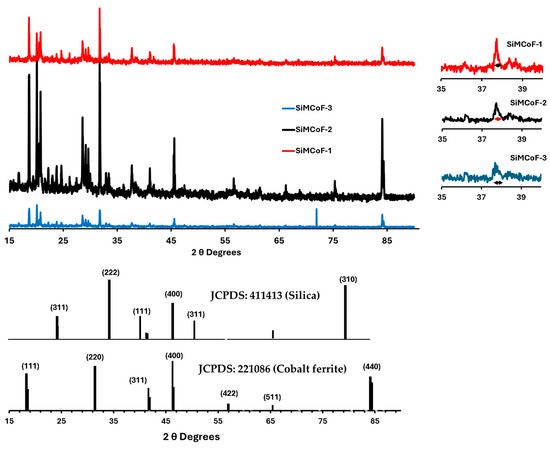

XRD analysis: X-ray diffraction (XRD) at 40 kV was used for phase identification and determination of structural parameters of all the SiMCoF particles, and the data are presented in Figure 5; the diffraction peak positions were compared with standard cards (JCPDS data with COD: 221,086 for cobalt ferrite and COD: 411,413 for silica).

Figure 5.

XRD for different SiMCoF particles.

From the X-ray diffraction (XRD), many broad peaks were observed in SiMCoF-3 with larger FWHM, depicting smaller crystallites and increased microstructural disorder compared to other SiMCoF particles. This may result in a larger surface area in SiMCoF-3, which can facilitate the absorption of oxygen impurities and increase the number of active reaction sites. This is also observed from its D values, which were determined by the Debye–Scherrer formula according to the following equation (Equation (1)):

where 0.9 is the shape factor, λ is the X-ray wavelength, B is the line broadening at half the maximum intensity (FWHM) in radians, and θ is the Bragg angle. Particle size calculated using the peak at 37.7°, SiMCoF-3 presents a particle size of 16.5 nm corresponding to the [220] facet of the cubic spinel ferrite structure [49]; however, SiMCoF-2 and SiMCoF-1 exhibited particle sizes of 38 nm and 87.7 nm, respectively. Also, the d-spacing value of SiMCoF, which was calculated using Bragg’s Law (Equation (2)), confirms the increased surface area and porosity in SiMCoF-3.

For example, SiMCoF-3 presented 2.8 Å at θ, 32°θ, while SiMCoF-2 had 1.2 Å at θ, 71°, and SiMCoF-1 showed 1.1 Å at θ, 84°, which indicates modifications in the crystal lattice parameters in SiMCoF-3, which can alter its electronic band structure, enhance light trapping ability, and thereby improve its photocatalytic performance. In addition, the presence of SiO2 was also identified from 21.8° [311], 31.2° [222], and 46.4° [400], and another set of peaks associated with cobalt ferrite corresponds to [422], [511], and [440] facets, indicating the characteristic diffraction pattern from fcc spinels with a grain size of 16.5 nm [50].

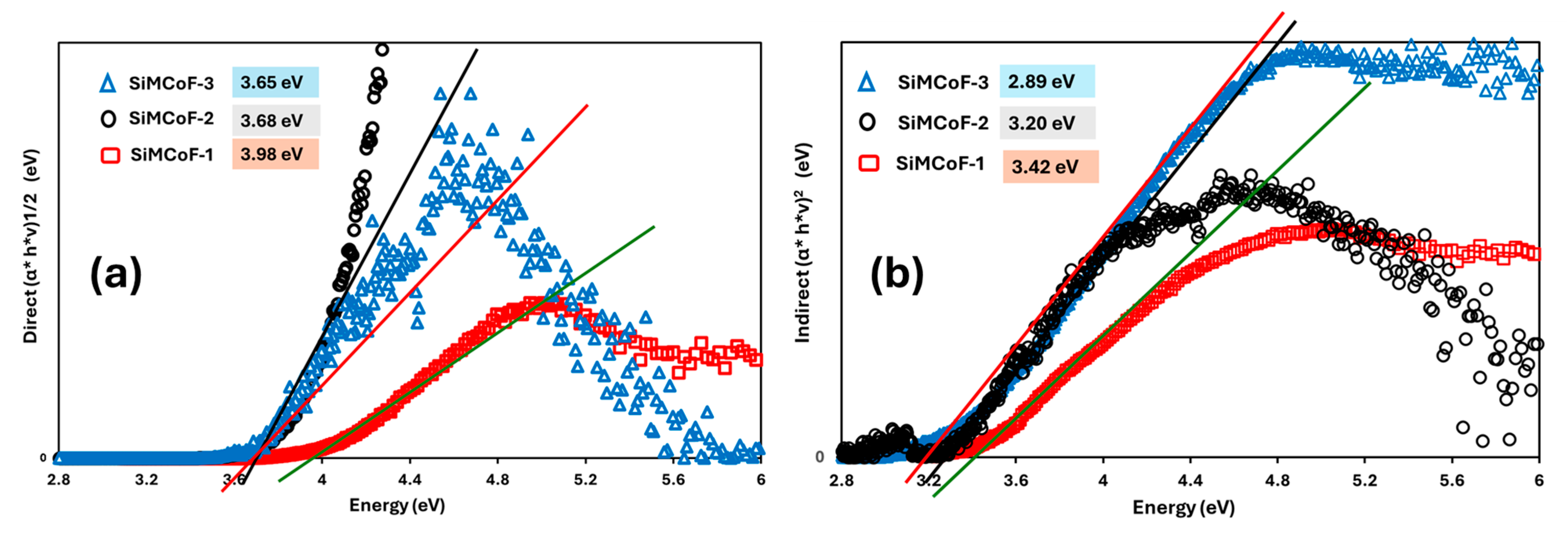

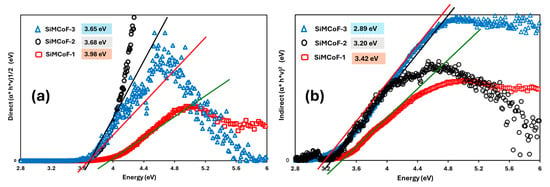

3.3. Electronic Properties of SiMCoF

To determine the minimum photon energy needed to excite an electron, which in turn affects how a SiMCoF interacts with light, direct and indirect bandgaps are determined by plotting the absorption coefficient versus photon energy. For a direct bandgap, a plot of (α h v)2 versus (h ʋ), while for an indirect bandgap, a plot of (α h v)1/2 versus (h ʋ) was obtained using Tauc exploration, Equations (3) and (4) [51]:

Direct bandgap:

(α h v)2

Indirect bandgap:

(α h v)1/2

The absorption coefficient (α), Planck constant (h), and photon frequency (v) were used to determine, e.g., from the extrapolated linear plot. The absorption coefficient (α) is determined by relating photon energy (h*ʋ) as follows in Equation (5):

where, e.g., optical bandgap energy and n: Power factor of the transition mode depend upon the nature of the material, whether it is crystalline or amorphous.

α = β/(hυ) (hυ − Eg)n or (αhυ)1/n = β(hυ − Eg)

Figure 6 shows the direct (Figure 6a) and indirect (Figure 6b) optical bandgap of different SiMCoF particles. The optical bandgap decreases significantly through the increase in SiO2 content in the matrix due to the increased presence of oxygen impurities; for example, the direct bandgap decreased from 3.98 (SiMCoF-1) to 3.65 eV for SiMCoF-3, similarly, its indirect bandgap showed a decrease from 3.42 (SiMCoF-1) to 2.89 eV for SiMCoF-3. This corresponds to the results observed in XRD of SiMCoF-3 with a higher interplanar spacing (d), which depicts the decrease in the energetic splitting between the bonding and antibonding states, shrinking the energy difference between the valence and conduction bands, resulting in a lower bandgap. In addition, the incorporation of silica particles introduces a structural change in the cobalt ferrite matrix, such as an increase in lattice strain and an increase in oxygen vacancies, which was observed by Raman and XRD results. These structural changes can affect the electronic band structure, often contributing to bandgap reduction by affecting available energy states and particle interactions. Therefore, SiMCoF-3 has a higher d-spacing and a lower bandgap, which is a desirable combination for improving its photocatalytic performance, since a lower bandgap allows the material to absorb a wider range of the solar spectrum.

Figure 6.

Tauc’s plot for (a) direct and (b) indirect bandgap of different SiMCoF particles.

3.4. Photocatalytic Studies

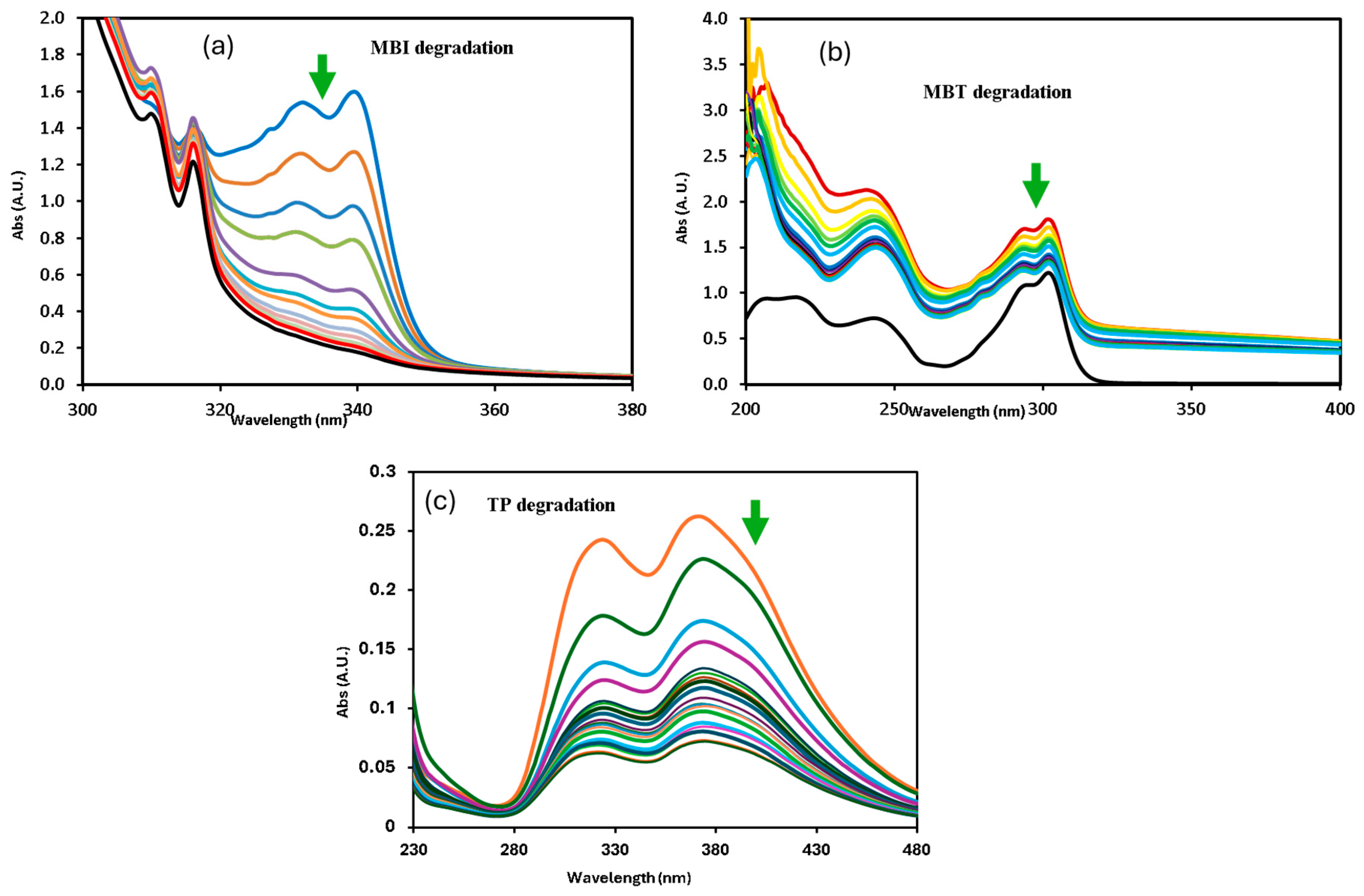

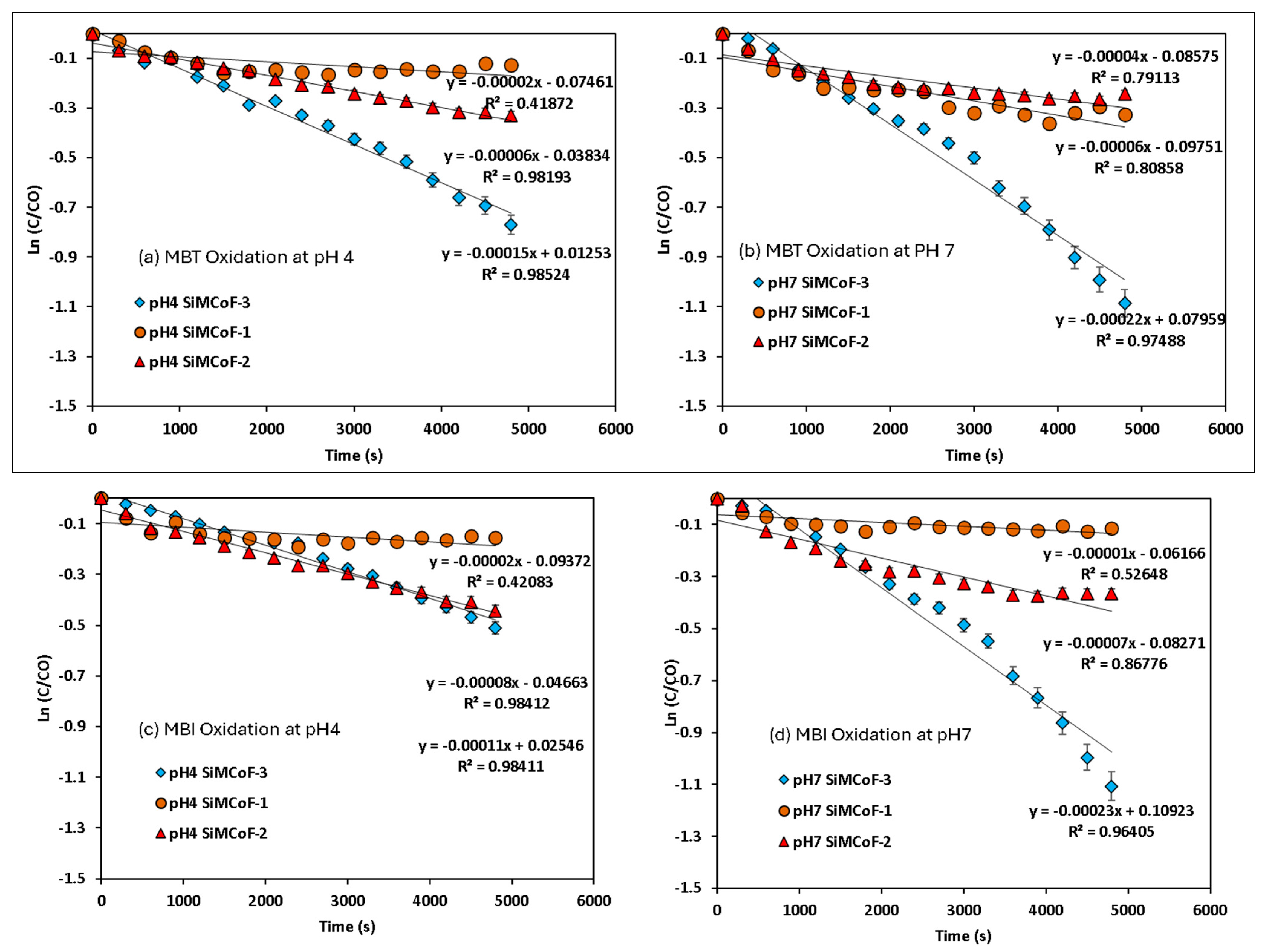

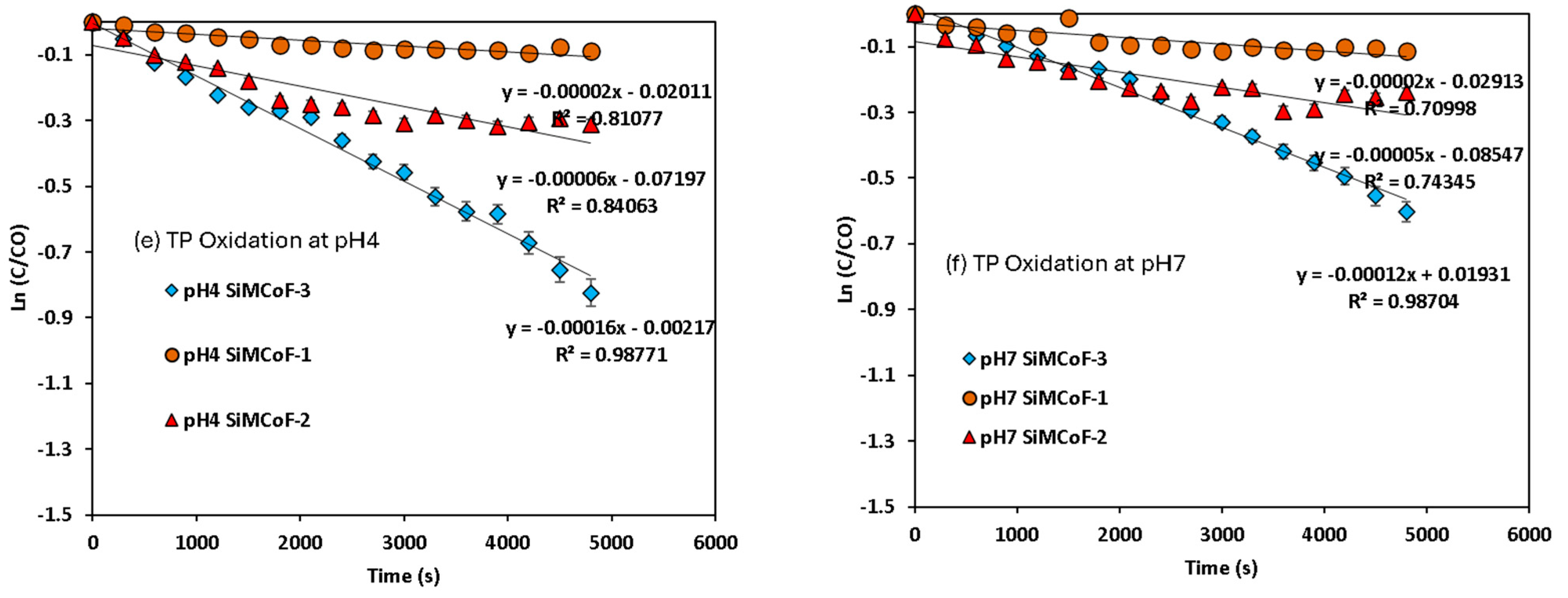

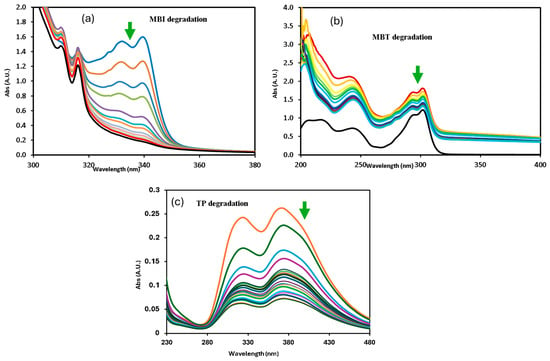

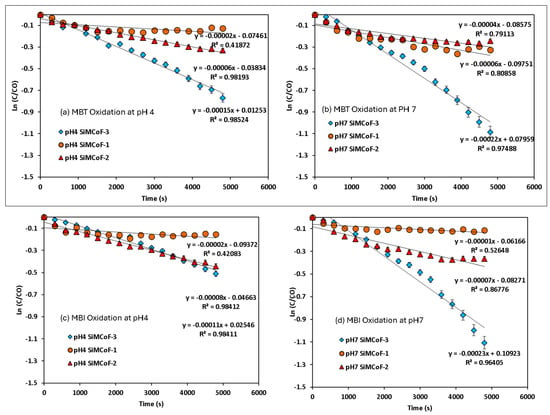

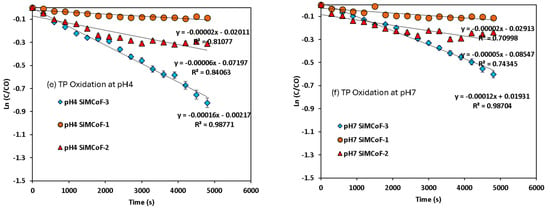

Photocatalytic activities of the synthesized SiMCoF catalysts were analyzed over the degradation of different mercapto contaminants such as 2-mercaptobenzothiazole (MBT), 2-mercaptobenzimidazole (MBI), and thiophenol (TP), in aqueous solution at pH 4 and pH 7 under sunlight irradiation. The observed absorbance changes during the degradation of each contaminant were recorded in the range of λmax 200–400 nm for 90 min at constant time intervals (Figure 7), and the corresponding concentration changes in the contaminants were measured (Figure 8) and plotted against time. The same experimental procedure was conducted with all the SiMCoF catalysts. The rate constant for all the contaminants was determined and compared.

Figure 7.

Changes in absorption profile of mercapto contaminants during the degradation under sunlight irradiation at pH 7: (a) MBI, (b) MBT, and (c) TP.

Figure 8.

Pseudo-first-order kinetics for mercapto contaminants during the degradation under sunlight irradiation: (a) MBT at pH 4, (b) MBT at pH 7, (c) MBI at pH 4, (d) MBI at pH 7, (e) TP at pH 4, and (f) TP at pH 7.

A decrease in band intensity in the UV range of all the contaminants corresponds to the π→π* and n→π* transitions of the studied mercapto contaminants, which was observed during the oxidation. Kinetic parameters obtained for the degradation under different experimental conditions are summarized in Table 2. The photocatalytic efficiency of SiMCoF catalysts was compared with using H2O2 and Fenton reagent under similar experimental conditions. For all the studied conditions, the experiment was conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility and accuracy of the results. The calculated average error percentage was within the predefined limits (<5%) deemed reliable for the experimental conditions studied.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for the degradation of mercapto contaminants by SiMCoF particles under sunlight irradiation.

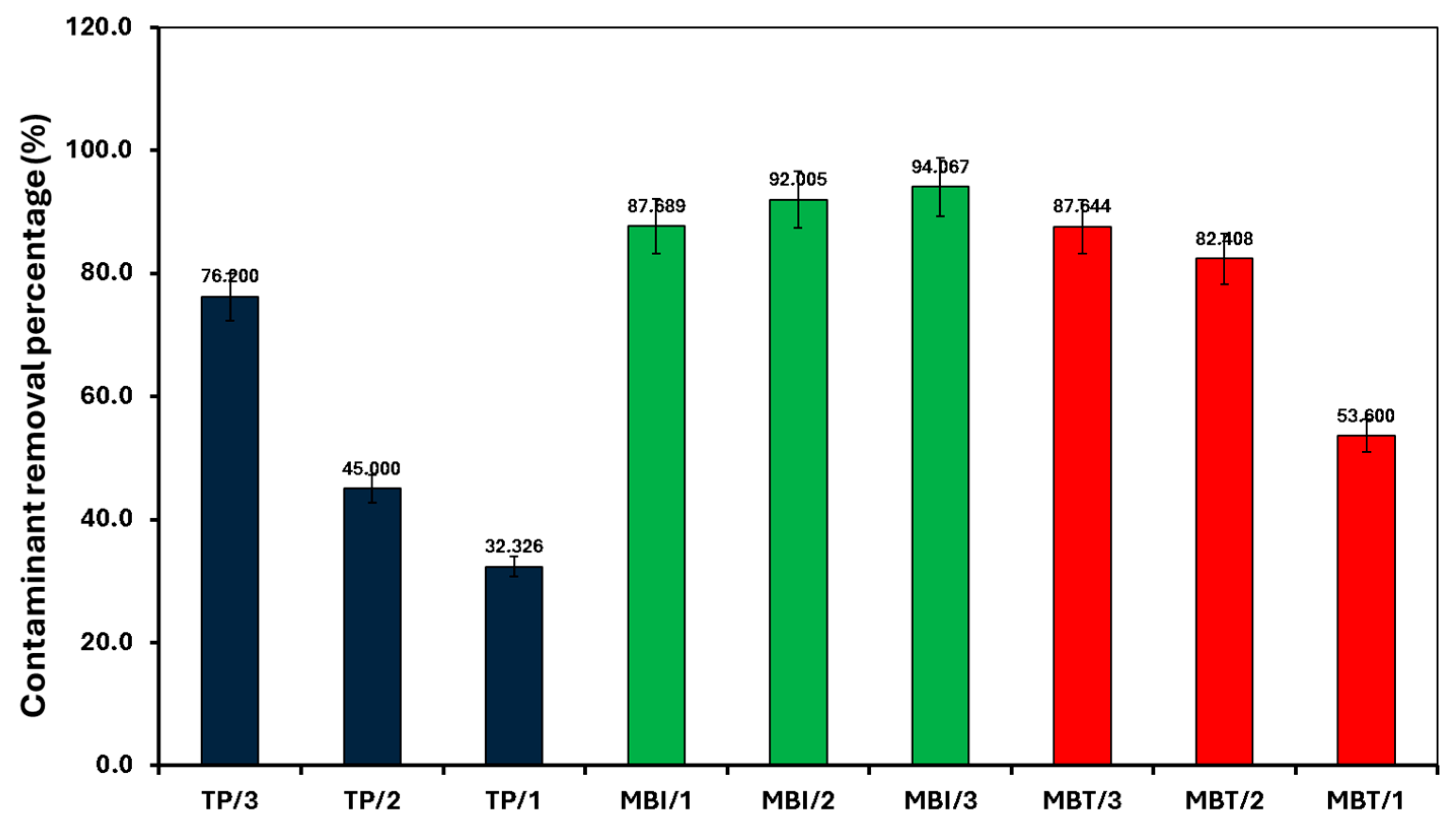

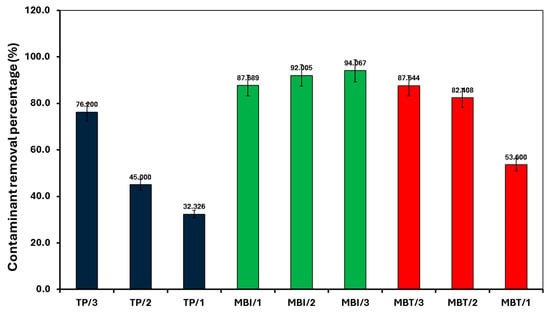

For all the contaminants studied, there was no degradation observed without sunlight irradiation (dark conditions) and without the presence of a catalyst (photolysis), suggesting that the degradation process appears to be a catalytic reaction triggered by a light source. The lack of reaction in the dark or without a catalyst confirms that both factors are critical for the observed degradation. For the other studied conditions, the fitted linear lines (R2~0.9) indicate that the degradation process follows pseudo-first-order kinetics. In all cases, SiMCoF-3 showed an elevated degradation rate and contaminant removal percentage (Figure 9), indicating the enhanced light absorption by SiMCoF-3 due to the increased oxygen vacancies that can introduce new energy levels below the conduction band, allowing the photocatalyst to absorb a wider range of light in the solar spectrum. For example, increased silica doping on cobalt ferrites (SiMCoF-3) has been shown to be effective, achieving over 94% removal of mercapto contaminants at a neutral pH, because the higher concentration of doped silica results in a larger total surface area and greater porosity. This expanded surface area provides more active sites for the mercaptan molecules and oxygen impurities for the oxidation of thiol groups. For all the contaminants, SiMCoF-3 showed similar results to peroxide oxidation and a higher velocity rate than the Fenton reagent. Since SiO2/CoFe2O4 is highly photoactive, it can effectively absorb photons from the light source due to a suitable band gap. The absorbed photon energy excites electrons from the VB to the CB, leaving behind positive “holes” in the VB. This facilitates the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide radicals (O2•−), by oxygen defects, which are crucial for photocatalytic reactions, which might be utilized in the degradation of the mercapto contaminants as follows:

SiO2/CoFe2O4 + hν → SiO2/CoFe2O4 + (h+ + e−)

H2O + h+ → ·OH (ROS) + H+

O2 + e− → ·O2− (ROS)

ROS + Mercapto contaminants → Favored degradation

Figure 9.

Removal of mercapto contaminants by different SiMCoF catalysts under sunlight irradiation at pH 7.

In addition, to verify the stability and reusability of SiMCoF catalysts, three cycles of photocatalytic experiments with the degradation of mercapto contaminants using each catalyst were performed under similar experimental conditions. The results show that the rate of degradation and percentage removal with each catalyst is still high (loss ≤ 5%) after five cycles.

The degradation efficiency of the present catalyst was compared with the reported results in the literature (Table S1), and it was found that the SiMCoF particles show a rate constant value 10 times higher than that of existing catalysts.

4. Conclusions

Nanoparticles of silica-doped cobalt ferrites of different stoichiometry were prepared, and their morphology and structural properties were analyzed. Results from TEM and SEM of the SiMCoF particles showed a uniform surface texture; their corresponding EDS analysis revealed that the higher concentration of SiO2 in the cobalt ferrite matrix presented a higher content of oxygen molecules. The AFM image of SiMCoF-3 presented a higher Rmax (139 nm) compared to other studied SiMCoF particles, revealing its increased surface area (100 µm2), which can facilitate the absorption of higher oxygen impurities, providing more active sites for the photocatalytic reaction. These observations coincide with the results from the Raman spectrum; it was detected that the increased silica content showed significant surface-enhanced Raman scattering signals of SIMCoF-3, indicating the stable nanostructured metallic surface present. This is further confirmed by the observed higher d-spacing value (2.8 Å) in XRD of SIMCoF-3, which also leads to affinity for oxygen impurities. Due to the smaller particle size of SiMCoF-3, the optical bandgap decreased from 3.42 (SiMCoF-1) to 2.89 eV for SiMCoF-3 because of the increased presence of oxygen impurities in the cobalt ferrite matrix. The photocatalytic behavior of each SiMCoF catalyst has been investigated over the oxidation of different mercapto contaminants at different pH conditions under sunlight irradiation. It was found that all the SiMCoF catalysts exhibited significant degradation over the contaminants studied without using any oxidation agents; in particular, SiMCoF-3 showed a similar yield to that achieved using a potential peroxide oxidant and was more effective than the Fenton reagent at neutral pH conditions. Therefore, these SiMCoF nanoparticles can be considered as alternative catalysts for mercapto contaminant removal under the natural environmental conditions in aqueous solution.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr14030483/s1, Table S1: Efficiency comparison of SiMCoF on the degradation of MBI, MBT and TP. Refs. [52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64] are cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.N.; Methodology, C.B.P.-C., J.N., and J.G.H.-H.; Validation, J.G.H.-H., M.d.C.D.-D.-d.-B., J.A.G.-O., G.H.-C., and J.A.J.-L.; Formal analysis, C.B.P.-C., A.J.S.-C., J.N., J.G.H.-H., J.A.G.-O., G.H.-C., and J.A.J.-L.; Investigation, C.B.P.-C., A.J.S.-C., J.G.H.-H., M.d.C.D.-D.-d.-B., J.A.G.-O., G.H.-C., and J.A.J.-L.; Data curation, C.B.P.-C., A.J.S.-C., J.G.H.-H., J.A.G.-O., G.H.-C., and G.H.-C.; Writing—original draft, J.N.; Writing—review and editing, J.N.; Supervision, M.d.C.D.-D.-d.-B.; Funding acquisition, J.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

J.N. acknowledges COMECyT (Consejo Mexiquense de Ciencia y Tecnología) for financial support under the Scheme “Cientifikas Mexiquenses 2025” (Folio: CIKAS--FICDTEM-25-074). The authors acknowledge USAII (Unidad de Servicios de Apoyo a la Investigación y a la Industria, Facultad de Química, UNAM) for analytical services.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, F.; Li, Q.; Xu, D. Recent Progress in Semiconductor-Based Nanocomposite Photocatalysts for Solar-to-Chemical Energy Conversion. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mchaouri, M.; Mallah, S.; Abouhajjoub, D.; Boumya, W.; Elmoubarki, R.; Essadki, A.; Barka, N.; Elhalil, A. Engineering TiO2 photocatalysts for enhanced visible-light activity in wastewater treatment applications. Tetrahedron Green Chem. 2025, 6, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashora, A.; Patel, N.; Kothari, D.C.; Ahuja, B.L.; Miotello, A. Formation of an intermediate band in the energy gap of TiO2 by Cu–N-codoping: First principles study and experimental evidence. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2014, 125, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, N.; Aravindan, S.; Ramki, K.; Murugadoss, G.; Thangamuthu, R.; Sakthivel, P. Sunlight-driven enhanced photocatalytic activity of bandgap narrowing Sn-doped ZnO nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 16792–16803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cao, J.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Li, D.; Wang, S.; Ao, Z. A new mechanism for visible light photocatalysis: Generation of intraband by adsorbed organic compounds with wide-bandgap semiconductors. Environ. Sci. Nano 2024, 11, 2415–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.; Erickson, S.; Matias, C.; Fluckiger, A.; Moses, L.; Colton, J.; Watt, R. Tuning the Band Gap of Ferritin Nanoparticles by Co-Depositing Iron with Halides or Oxo-anions. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 20782–20788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalla, N.; Taneja, S.; Thakur, P.; Sharma, P.K.; Mariotti, D.; Maddi, C.; Ivanova, O.; Petrov, D.; Sukhachev, A.; Edelman, I.S.; et al. Doping Independent Work Function and Stable Band Gap of Spinel Ferrites with Tunable Plasmonic and Magnetic Properties. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 9780–9788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C.A.; Ferrer, P.; Grinter, D.C.; Kumar, S.; da Silva, I.; Rubio-Zuazo, J.; Bencok, P.; de Groot, F.; Held, G.; Grau-Crespo, R. Spinel ferrites MFe2O4 (M = Co, Cu, Zn) for photocatalysis: Theoretical and experimental insights. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 29645–29656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holinsworth, B.S.; Mazumdar, D.; Sims, H.; Sun, Q.C.; Yurtisigi, M.K.; Sarker, S.K.; Gupta, A.; Butler, W.H.; Musfeldt, J.L. Chemical tuning of the optical band gap in spinel ferrites: CoFe2O4 vs NiFe2O4. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 103, 082406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, O.; Tayal, A.; Kim, J.; Song, C.; Chen, Y.; Hiroi, S.; Katsuya, Y.; Ina, T.; Sakata, O.; Ikeya, Y.; et al. Tuning of structural, optical band gap, and electrical properties of room-temperature-grown epitaxial thin films through the Fe2O3:NiO ratio. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.Y.; Bai, B.C.; Kim, Y.R. Effective Surface Structure Changes and Characteristics of Activated Carbon with the Simple Introduction of Oxygen Functional Groups by Using Radiation Energy. Surfaces 2024, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Lievanos, K.R.; Sun, T.; Gendrich, E.A.; Knowles, K.E. Surface Adsorption and Photoinduced Degradation: A Study of Spinel Ferrite Nanomaterials for Removal of a Model Organic Pollutant from Water. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 3981–3998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Dang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, H.; Ben, H.-J.; Li, J.; Lin, F.; Shao, K.; et al. Highly Efficient Adsorption of Organic Impurities in Industrial-Grade H2O2 Using π–π Interaction. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 16634–16639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Seebauer, E.G. Effects of adventitious impurity adsorption on oxygen interstitial injection rates from submerged TiO2(110) and ZnO(0001) surfaces. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2023, 41, 033203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, C.; Li, Y.; Lebedev, K.; Chen, T.; Day, S.; Tang, C.; Tsang, S.C.E. Characterisation of oxygen defects and nitrogen impurities in TiO2 photocatalysts using variable-temperature X-ray powder diffraction. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E.R. Understanding defects in semiconductors as key to advancing device technology. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2003, 340–342, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; He, X.; Wu, P.; Gong, F.; Wang, D.; Wang, S.; Lu, S.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, S.; Kai, T.; et al. Recent advances in the design of semiconductor hollow microspheres for enhanced photocatalyticv water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 27974–27996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Han, Y.; Yan, Y.; Zong, Y.; Zhao, R.; Han, J.; Wang, L. Construction of hollow NiTiO3/CuCo2S4 double-shell nanospheres for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 156864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Kumar, A.; Dhiman, P.; Sharma, G.; Wang, T. Recent advances in rare earth metal ferrites-based heterojunctions for photocatalytic water treatment, hydrogen production and CO2 conversion. J. Rare Earths 2025, 43, 1571–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zheng, Y.; He, C.-S.; Lai, B.; Ma, J.; Nan, J. Introduction of oxygen vacancy to manganese ferrite by Co substitution for enhanced peracetic acid activation and 1O2 dominated tetracycline hydrochloride degradation under microwave irradiation. Water Res. 2022, 225, 119176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Dong, W.; Huang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhou, J.L.; Li, W. Photocatalysis for sustainable energy and environmental protection in construction: A review on surface engineering and emerging synthesis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojić, B.; Giannakopoulos, K.P.; Cvejić, Ž.; Srdić, V.V. Silica coated ferrite nanoparticles: Influence of citrate functionalization procedure on final particle morphology. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, 6635–6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Menon, D.; Akhil Varri, V.S.; Sahoo, M.; Ranganathan, R.; Zhang, P.; Misra, S.K. Does the doping strategy of ferrite nanoparticles create a correlation between reactivity and toxicity? Environ. Sci. Nano 2023, 10, 1553–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soufi, A.; Hajjaoui, H.; Boumya, W.; Elmouwahidi, A.; Baillón-García, E.; Abdennouri, M.; Barka, N. Recent trends in magnetic spinel ferrites and their composites as heterogeneous Fenton-like catalysts: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 367, 121971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartsonakis, I.A.; Stamatogianni, P.; Karaxi, E.K.; Charitidis, C.A. Comparative Study on the Corrosion Inhibitive Effect of 2-Mecraptobenzothiazole and Na2HPO4 on Industrial Conveying API 5L X42 Pipeline Steel. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.S.; Nogara, P.A.; Lima, L.S.; Galiciolli, M.E.A.; Souza, J.V.; Aschner, M.; Rocha, J.B.T. Toxic metals that interact with thiol groups and alteration in insect behavior. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2022, 52, 100923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagiyan, G.A.; Koroleva, I.K.; Soroka, N.V.; Ufimtsev, A.V. Oxidation of thiol compounds by molecular oxygen in aqueous solutions. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2003, 52, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Stamatelatos, D.; McNeill, K. Aquatic indirect photochemical transformations of natural peptidic thiols: Impact of thiol properties, solution pH, solution salinity and metal ions. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2017, 19, 1518–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rücker, C.; Mahmoud, W.M.M.; Schwartz, D.; Kümmerer, K. Biodegradation tests of mercaptocarboxylic acids, their esters, related divalent sulfur compounds and mercaptans. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 18393–18411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B, U.; Rajaram, R. Microaerobic degradation of 2-Mercaptobenzothiazole present in industrial wastewater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 321, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebbi, A.; Hentati, D.; Cheffi, M.; Bouabdallah, R.; Choura, C.; Sayadi, S.; Chamkha, M. Promising abilities of mercapto-degrading Staphylococcus capitis strain SH6 in both crude oil and waste motor oil as sole carbon and energy sources: Its biosurfactant production and preliminary characterization. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 93, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Bilal, M.; Li, X.; Shah, S.; Mohamed, B.; Hadibarata, T.; Cheng, H. Peroxidases-based enticing biotechnological platforms for biodegradation and biotransformation of emerging contaminants. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 136035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Martín, M.I.; Escapa, A.; Alonso, R.M.; Canle, M.; Morán, A. Degradation of 2-mercaptobenzothizaole in microbial electrolysis cells: Intermediates, toxicity, and microbial communities. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 733, 139155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Li, F.; He, Y.; Bai, H.; Yang, X.; Wang, S.; Jiang, F. A novel mercapto-functionalized bimetallic Zn/Ni-MOF adsorbents for efficient removal of Hg(II) in wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Wang, Y.; He, P.; Wang, Y.; Wei, G. Recent Advances in Metal–Organic Framework (MOF)-Based Composites for Organic Effluent Remediation. Materials 2024, 17, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Zuniga, G.; Antwi, S.; Soni-Castro, P.; Olayiwola, O.; Chuprin, M.; Holmes, W.E.; Buchireddy, P.; Gang, D.; Revellame, E.; Zappi, M.E.; et al. Methyl Mercaptan Removal from Methane Using Metal-Oxides and Aluminosilicate Materials. Catalysts 2024, 14, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Shi, W.; Jia, D.; Fu, Z.; Gao, H.; Tao, J.; Guo, T.; Chen, J.; Shu, X. Review on advances in adsorption material for mercaptan removal from gasoline oil. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2024, 139, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Mu, W.; Qin, C.; Liu, T.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, W.; Fang, J.; Ai, T.; Tian, R.; Zhang, L.; et al. Synchronous catalytic elimination of malodorous mercaptans based VOCs: Controlling byproducts and revealing sites-pathway relationship. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2024, 357, 124253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.-H.; Zhang, Z.-Z.; Liu, Y.; Zou, L.-H. Recent Progress in Catalytically Driven Advanced Oxidation Processes for Wastewater Treatment. Catalysts 2025, 15, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Kim, T.-H.; Kim, T.-H.; Lee, J.; Yu, S. Enhancement of TOC removal efficiency of sulfamethoxazole using catalysts in the radiation treatment: Effects of band structure and electrical properties of radiocatalysts. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 312, 123390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Cuevas, A.-J.; Palacios-Cabrera, C.-B.; Tecuapa-Flores, E.D.; Bazany-Rodríguez, I.J.; Narayanan, J.; Padilla-Martínez, I.I.; Aguilar, C.A.; Pandiyan, T. CO2 Adsorption by carbon quantum dots/metal ferrites (M=Co2+, Ni2+, and Zn2+): Electrochemical and theoretical studies. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 13977–14000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygar, G.; Kaya, M.; Özkan, N.; Kocabıyık, S.; Volkan, M. Preparation of silica coated cobalt ferrite magnetic nanoparticles for the purification of histidine-tagged proteins. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2015, 87, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, H.; Truong, V.K.; Hasan, J.; Fluke, C.; Crawford, R.; Ivanova, E. Roughness Parameters for Standard Description of Surface Nanoarchitecture. Scanning 2012, 34, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.J.; Jakob, D.S.; Centrone, A. A guide to nanoscale IR spectroscopy: Resonance enhanced transduction in contact and tapping mode AFM-IR. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 5248–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enríquez, E.; del Campo, A.; Reinosa, J.J.; Konstantopoulos, G.; Charitidis, C.; Fernández, J.F. Correlation between structure and mechanical properties in α-quartz single crystal by nanoindentation, AFM and confocal Raman microscopy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 2655–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Kuřitka, I.; Vilcakova, J.; Havlica, J.; Másilko, J.; Kalina, L.; Tkacz, J.; Svec, J.; Enev, V.; Hajdúchová, M. Impact of grain size and structural changes on magnetic, dielectric, electrical, impedance and modulus spectroscopic characteristics of CoFe2O4 nanoparticles synthesized by honey mediated sol-gel combustion method. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 8, 045002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.W.; Pedroza, R.C.; Sartoratto, P.P.C.; Rezende, D.R.; Silva Neto, A.V.; Soler, M.A.G.; Morais, P.C. Raman spectroscopy of cobalt ferrite nanocomposite in silica matrix prepared by sol–gel method. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2006, 352, 1602–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.Z.; Wu, X.L.; Gao, F.; Shen, J.C.; Li, T.H.; Chu, P.K. Determination of surface oxygen vacancy position in SnO2 nanocrystals by Raman spectroscopy. Solid. State Commun. 2011, 151, 811–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rodríguez, J.; Soto, G.; Medina, J.L.; Portillo-López, A.; Hernández-López, E.; Viveros, E.V.; Elizalde Galindo, J.T.; Tiznado, H.; Flores, D.-L.; Muñoz-Muñoz, F. Cobalt–zinc ferrite and magnetite SiO2 nanocomposite powder for magnetic extraction of DNA. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, D.; Serrano-Garcia, R.; Govan, J.; Gun’ko, Y.K. Synthesis Characterization and Photocatalytic Studies of Cobalt Ferrite-Silica-Titania Nanocomposites. Nanomaterials 2014, 4, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makuła, P.; Pacia, M.; Macyk, W. How To Correctly Determine the Band Gap Energy of Modified Semiconductor Photocatalysts Based on UV–Vis Spectra. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 6814–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zhang, T.; Meng, S.; Zhou, P.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, M. BaFe12O19/BiOBr S-scheme heterojunction magnetic nanosheets for high-efficiency photocatalytic degradation of 2-mercaptobenzothiazole. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 326, 124746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, L.; Abedeen, M.Z.; Sharma, M.; Sharma, P.; Agarwal, M.; Gupta, R. Sustainable photocatalytic mitigation of 2-mercaptobenzothiazole by expired medicine derived metal-free graphitic carbon nitride photocatalyst. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 5387–5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Lu, H.; Wang, J.; He, S.; Duan, X.; Ren, Y. Mixed valence Fe/Mn bimetallic MOF modified carbon fiber paper cathode designed for the degradation of 2-mercaptobenzothiazole by inhomogeneous Electro-Fenton. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2025, 320, 122433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkhemkhem, K.N.; Bourahla, S.; Belayachi, H.; Nemchi, F.; Belhakem, M. Sonocatalytic degradation of 2-Mercaptobenzothiazole (MBT) in aqueous solution by a green catalyst Maghnite-H+. Iran. J. Catal. 2024, 14, 142415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, C.; Yang, J. High-efficiency photocatalytic degradation of 2-MBT under visible light using montmorillonite-modified Bi3O4Br catalysts. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 5365–5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Yadav, R.K.; Pande, P.P.; Singh, S.; Chaubey, S.; Singh, P.; Gupta, S.K.; Gupta, S.; Kim, T.W.; Tiwary, D. Dye degradation and sulfur oxidation of methyl orange and thiophenol via newly designed nanocomposite GQDs/NiSe-NiO photocatalyst under homemade LED light. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 2023, 99, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, K.; Shen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Fang, W. Photocatalytic 1,2-Thiosulfonylation of alkenes with thiophenols and sulfonyl chlorides promoted by directly knitted copper polymers. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 8585–8593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, J.; Ni, K.; Qin, X.; Wang, L.; Hou, J.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Wang, M.; An, J. Innovative application of polyether amine as a recyclable catalyst in aerobic thiophenol oxidation. Organics 2024, 5, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, Y.; Lin, X.-M.; Niklas, J.; Poluektov, O.G.; Diroll, B.T.; Lin, Y.; Wen, J.; Hood, Z.D.; Lei, A.; Shevchenko, E.V. Insights into the extraction of photogenerated holes from CdSe/CdS nanorods for oxidative organic catalysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 12690–12699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aazam, E. Visible light photocatalytic degradation of thiophene using Ag–TiO2/multi-walled carbon nanotubes nanocomposite. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 6705–6711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Cai, J.; An, Z.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.; Huang, S.; Lu, N.; Xie, Q.; et al. Photoelectrocatalytic selective removal of group-targeting thiol-containing heterocyclic pollutants. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 452, 131307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.-n.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, G. Selective electrocatalytic degradation of odorous mercaptans derived from S–Au bond recongnition on a dendritic gold/boron-doped diamond composite electrode. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 8067–8076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefi-Oskoui, S.; Jalali, D.; Sadeghi Rad, T.; Voskressensky, L.G.; Khataee, A. Synthesis and characterization of cobalt–gallium layered double hydroxide for sonocatalytic degradation of 2-mercaptobenzoxazole from water. ACS EST Water 2025, 5, 5563–5574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.