Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the substitution of wheat flour (WF) for grape (Vitis vinifera L.) pomace (GP) on cookie formulation. The techno-functional properties of GP flour (GPF) were characterized, and cookie formulations containing 15% (C15) and 20% (C20) GPF were developed. To evaluate the antioxidant and functional potential, free (FPF, soluble phenols) and bound phenolic fraction (BPF, insoluble phenols) were extracted. The total phenolic content (TPC) and antioxidant potential (ABTS and DPPH assays) were measured. The GPF shows differences in oil and water retention, non-foaming properties, and non-significant differences in swelling capacity compared to WF. C15 and C20 show L* values from 27.9 to 36.2, b* values from 2.22 to 2.64, and a* values from 8.84 to 10.49. GPF addition elevates ash and fiber content by 3.5–4.2 and 14–31.6 times. GPF cookie (C15) exhibited a significantly higher TPC compared to WF. Although the FPF fraction in the cookies was higher compared to BPF, the contribution of BPF to antioxidant activity was high (DPPH = 29.9%, ABTS = 16.3%) compared to FPF (DPPH = 26.3%, ABTS = 20.3%). Given that FPF is traditionally the only antioxidant fraction measured, the antioxidant potential of incorporating grape by-products is being underestimated; this is the first report of this in a cookie.

1. Introduction

The grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) represents one of the most cultivated fruit crops worldwide. The 2021 estimated grape production rose to 73 million tons, where nearly 50% to 75% of the total was destined for wine and juice production [1,2]. Throughout the winemaking process, one of the main byproducts is grape pomace (GP).

GP is obtained from grape crushing and represents between 20 and 30% of the total grape weight. GP could include stems, leaves, peels, and seeds [3,4,5]. This by-product is rich in several nutritional components, including proteins, lipids, vitamins, minerals, and phenolic compounds, showing promising potential [6,7]. Nevertheless, dietary fibers constitute the major component (43–75%) [5,8]. Dietary fiber consumption is closely related to colon health and contributes to chronic non-infectious disease prevention [9,10]. Furthermore, the phenolic compounds bound to polysaccharides in dietary fibers like cellulose and pectin exhibit important antioxidant activities, linked to neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, anticarcinogenic, and other benefits [11,12]. It is estimated that 30 Kg of GP is produced by each 100 L of wine, with nearly 70% of the polyphenolic content remaining in this by-product [13].

Normally, manufacturers use diverse practices for fruit pomace management, where incineration and landfilling are the most common, provoking an elevated environmental impact [14,15]. In addition, the elevated consumption of highly palatable and ultra-processed foods is highly related to the development of health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease, and even mental issues such as depression or anxiety [16,17]. Bakery products are an example of this type of food, which are highly preferred by the population but low in nutrient content [18], highlighting the idea that fortifying food adds value to emerging snacks, transforming simple foods into nourishing foodstuffs.

Cookies are baked products with the potential for functionalization due to their elevated popularity, long shelf life, storage simplicity, and affordable nature [19]. Furthermore, the incorporation of agro-industrial by-products into this class of foods remains challenging, as key molecules such as polyphenols can be affected by elevated temperatures, which are essential for developing bakery products [20]. Likewise, although some studies have already documented the partial substitution of wheat flour (WF) by GP in bakery product formulation [21,22,23,24,25,26], there is a lack of studies focused on the incorporation of this class of by-product and its effects on the antioxidant capacities of bound phenols (BP) in cookie formulation. BPs are usually attached to cell wall components through covalent bonds (e.g., ether, ester, or C-C), which makes their extraction difficult [27,28], but also presents an opportunity for phenol bioactivity preservation at the intestinal level. This study aims to evaluate the physicochemical, nutritional, and bioactive effects of substituting WF with grape pomace in the elaboration of functional cookies to produce a formulation with a reduced ingredient number and a short baking process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2,2′-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid (ABTS) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA); 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); sodium carbonate (Jalmek, San Nicolás, N.L., Mexico), sodium hydroxide (GOLDEN BELL, Mexico City, Mexico), ethanol (Jalmek, San Nicolás, N.L., Mexico), Hexane (Jalmek, San Nicolas, N.L., Mexico), chlorohydric acid (GOLDEN BELL, Mexico City, Mexico), Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (GOLDEN BELL, Mexico City, Mexico), gallic acid (Jalmek, San Nicolas, N.L., Mexico), potassium persulfate (Analytyka, Mexico City, Mexico).

2.2. Grape Pomace Flour Preparation

GP from Vitis vinifera var. Cabernet Sauvignon, derived from wine production, was obtained from a local winery in Parras, Coahuila, Mexico. Briefly, GP was oven-dried (MIGSA FD-1, Mexico City, Mexico) at 60 °C for 24 h, ground in a multifunctional grinder (GM–800S, Shenzhen, China), and separated using a sieve (FIICSA, Mexico City, Mexico) to obtain flours with particle sizes of 150 and 250 μm. The Grape Pomace Flours (GPFs) were stored using vacuum-sealed food-grade packaging until further analysis.

2.3. Flour Characterization

2.3.1. Water and Oil Retention Capacity

To determine water retention capacity (WRC), the samples were over-hydrated using distilled water for 24 h. After, the samples were centrifuged at 2000× g for 25 min, and the supernatant was removed. During oil retention capacity (ORC) analysis, samples were mixed with 20 mL of sunflower oil and centrifuged at 2000× g for 20 min. Finally, the supernatant was decanted. WRC and ORC were expressed as g of liquid per g of sample [29].

2.3.2. Swelling Capacity

Samples (1.0 g) were placed into a 10 mL graduated cylinder, and the occupied volume (V0) was measured. Distilled water (5 mL) was added and manually mixed for 5 min. The volume of settled particles was evaluated after 24 h of room-temperature (~25 °C ± 1) hydration (V1) [30]. Swelling capacity (SWC) was calculated using Equation (1).

2.3.3. Foaming Properties

Samples (2.0 g) were mixed with 50 mL of distilled water and placed into a 100 mL graduated cylinder, and the occupied volume was measured (volume before whipping). The suspension was properly whipped using a blender for 3 min to form a foam. The foamed content was transferred to the cylinder again, and the generated volume was recorded [31].

The foaming capacity (FC%) was calculated using Equation (2). Foaming stability (FS%) was calculated using Equation (3).

2.3.4. pH and Titratable Acidity

For the production of extracts, samples (5.0 g) were mixed with 100 mL of distilled water and kept under magnetic stirring for 30 min. The sample suspension was filtered using a Büchner funnel. pH value was determined using a potentiometer (LAQUAact PC110, Horiba, Kyoto, Japan).

For the titratable acidity (TA%), extracts (15 mL) were titrated using NaOH 0.1 N, until reaching 8.2 pH value, corresponding to the end point of phenolphthalein. The titratable acidity was calculated using Equation (4), using a 0.075 g/meq for tartaric acid [32,33].

2.4. Cookies Preparation

The raw ingredients in the cookie formulation were butter, sugar, salt, and vanilla extract. For the experimental formulations, 15% (C15) and 20% (C20) weight per weight (w/w) of wheat flour were substituted with GPF, while other ingredients were added in fixed amounts (Table 1). A control cookie (CC) without GPF was also formulated. All ingredients were mixed to obtain a homogeneous dough and refrigerated for 15 min. Dough portions (5.0 g) were weighed and rolled out to a thickness of 1 cm and approximately ~4.0 cm in diameter. The shaped dough was transferred to trays and refrigerated for 15 min. Samples were baked (Gourmia, GTF7660, New York, NY, USA) at 180 °C for 4 min. Samples were cooled at room temperature and packaged in plastic bags until further analysis.

Table 1.

Experimental formulation for fortified cookies (g).

2.5. Color Analysis

Color measurements for samples (cookies and flours) were determined using a digital colorimeter (Konica Minolta, CR–400, Osaka, Japan). The color results were expressed using the CIELAB parameters, with L* used for luminance (black = 0; white = 100), a* used for green (negative values) to red colors (positive values), and b* used for blue (negative values) to yellow (positive values) colors. The apparatus was calibrated with a white tile as a standard. Measures were taken at three different sample locations.

2.6. Proximal Characterization

The proximate composition for all samples was determined using the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) 1990 methods, including moisture (964.22), ashes (923.03), crude fat (920.39), and crude fiber (62.09).

2.7. Bioactive Characterization

2.7.1. Phenolic Extraction

Extracts from flour and cookies were produced. In cookies, free (FPF) and bound (BPF) phenolic fractions were extracted. The GPF (1.0 g) was mixed with ethanol and agitated at 230 revolutions per minute (rpm) for 24 h. The ethanolic extract was filtered using a Büchner funnel. The extracts were stored at −2 °C until use. For cookies, samples were defatted before analysis. The cookie samples (2.5 g) were homogenized using a pestle and mortar. The milled samples were mixed with hexane (25 mL) and magnetically stirred at 45 °C for 45 min. Hexane in the sample was decanted, and the residual solvent evaporated in a fume hood. The defatted samples were used for ethanol extract production.

For BPF, defatted samples (1.0 g) were mixed with 25 mL of NaOH 0.1 M for 2 h using a magnetic stirrer. The reaction solution was acidified using HCl 2 M, until a ~2 pH value and transferred to a separation funnel, and 30 mL of ethyl acetate was added. The mixture was homogenized and rested for 30 min. The aqueous phase was decanted. The organic solvent was evaporated, and the resulting phenolics were suspended in ethanol (96%) [34].

2.7.2. Total Phenolic Content

The Total Phenolic Content (TPC) was measured spectrophotometrically. During the analysis, 800 µL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent was mixed with 800 µL of the sample, and the solution was mixed for 1 min, and incubated for 5 min more at room temperature in dark conditions. After incubation, 800 µL of Na2CO3 0.01 M was added, and the mixture was diluted with 1000 µL of distilled water. The absorbance was read at 790 nm (VELAB, VE–5000V, Mexico City, Mexico). A standard curve was prepared using gallic acid (1–6 mg/mL) and employed to calculate the sample concentration. The results were expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalents per g of sample (GAE mg/g sample) [35].

2.7.3. Antioxidant Capacity

Antioxidant capacity (AC) was measured in cookies and flour samples.

ABTS

For ABTS scavenging activity, the ABTS radical was produced by mixing ABTS 7 mM and potassium persulfate 2.45 mM. After a dark incubation for 16 h, the radical was diluted to reach an absorbance of 0.7 ± 0.01 at 734 nm in a spectrophotometer. An aliquot of a 50 µL sample was added to 950 µL of the ABTS radical solution, gently mixed, and incubated in dark conditions for 2 min. Using the same wavelength, the sample absorbance was recorded [36].

DPPH

For DPPH scavenging activity, 100 µL of the sample was added to 2900 µL of the 60 mM DPPH radical solution. After vortex homogenization, the reaction solution was incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The sample absorbance was read at 517 nm [37].

For ABTS and DPPH, the results were expressed as % of radical reduction. To calculate the AC, the control (Ac) and sample (As) absorbance were used in Formula (5). The employed control was ethanol.

2.8. Statistics

The results were presented as the mean value from a triplicate. A t-independent t in bioactive characterization or a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) in techno-functional and proximal analysis was conducted for the experiments, followed by Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test for mean comparison. All analyses were performed on the software STATISTICA 2004 (version 7.0.61.0). The statistical calculation was made at a significance of p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Flour Characterization

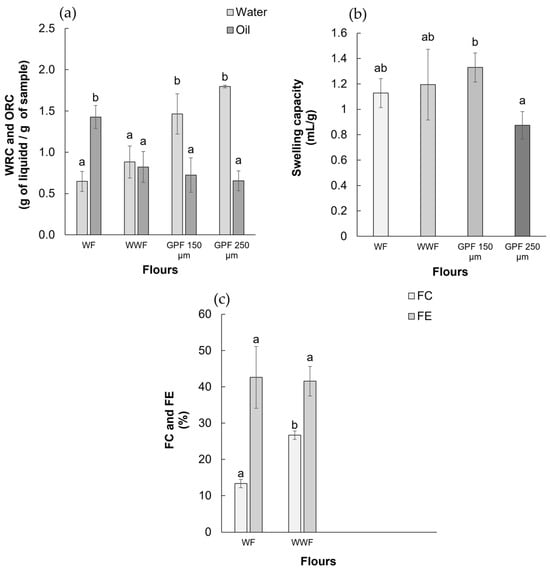

GPF in 150 and 250 μm has a yield of 9.56% and 22.52%, respectively. The techno-functional analysis was developed in both particle-size GPF, WF, and whole-wheat flour (WWF).

3.1.1. Water and Oil Retention Capacity

Figure 1a shows the results for WRC and ORC. The WRC was statistically higher in GPFs. The 250 µm particle size shows a 1.80 ± 0.01 g/g WRC value, while the small particle size was 1.46 ± 0.24 g/g, with no statistically significant differences. The WF and WWF showed WRC, at 0.64 ± 0.12 g/g and 0.88 ± 0.19 g/g, respectively, with no significant differences between them. On the other hand, the ORC was elevated in WF with (1.42 ± 0.13 g/g), with no differences among WWF (0.82 ± 0.18 g/g) and GPFs (0.65 ± 0.12 and 0.72 ± 0.20 g/g).

Figure 1.

Techno-functional parameter characterization for different flours: (a) water retention capacity and oil retention capacity; (b) swelling capacity; (c) foam capacity and foam stability. WF: wheat flour. WWF: whole-wheat flour. GPF: grape flour with 150 µm and 250 µm particle size. Columns within different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences according to the Tukey test (p < 0.05).

3.1.2. Swelling Capacity

Figure 1b shows the SWC results. The GPF with a 150 µm particle size shows the higher values (1.33 ± 0.11 g/g) compared with the 250 µm (0.87 ± 0.11 g/g), while WF (1.13 ± 0.11 g/g) and WWF (1.19 ± 0.28 g/g) show no statistically significant differences among them and are comparable with both GPFs.

3.1.3. Foaming Properties

Figure 1c shows the FC% and FE% of the four analyzed flours. The WWF presents major FC values (26.33% ± 1.15), followed by WF (13.33% ± 1.15), with no statistical differences in wheat flour stability (~41–42%). The GPFs lack foam after analysis. The following analysis was carried out using only WF and GPF 250 µm due to the low differences between functional properties and the expected application in a food product.

3.1.4. pH and Titratable Acidity

WF presents pH 5.78 ± 0.02, while GPF presents pH 3.71 ± 0.03. The titratable acidity in GPF (6.86 ± 0.20%) was higher than in WF (0.12 ± 0.01%).

3.2. Cookies’ Characterization

3.2.1. Color Analysis

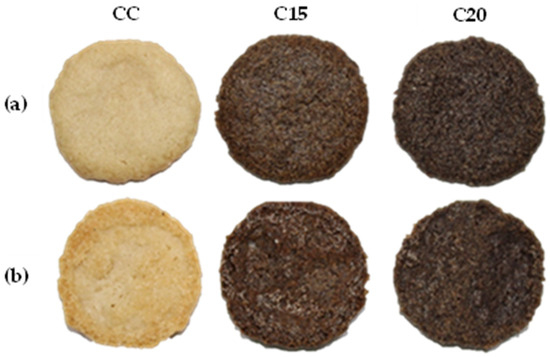

Figure 2 shows the cookies obtained after the baking procedure, with perceptible color changes between the respective formulations.

Figure 2.

Different cookie formulations after baking: (a) top surface; (b) bottom surface in control cookies (CC); cookie with 15% of GPF (C15); and cookie with 20% of GPF (C20).

The color analysis for the flour and cookies is shown in Table 2. The GPF presents warm tones with low luminosity, with L* values from 24.8 to 30.34, a* values near 12.97–17.37, and b* values between 1.08 and 15.18. In Table 2, it is possible to appreciate that in fortified cookies, all the color parameters are statistically different compared to the control cookie. In the case of the luminosity (L*) parameter, a decrease is observed after the addition. For all individual samples, no statistical differences were detected between the bottom- and top-surface luminosity. The red and green color (b*) parameter shows differences, especially between the top and bottom surfaces, with a slight improvement in redness color after GPF incorporation. The blue and yellow (b*) parameters are also affected by the GPF addition, with an important yellow displacement during cookie fortification.

Table 2.

Color analysis for flour and cookie formulations.

3.2.2. Proximal Characterization

Table 3 shows the proximal composition of the control and formulations. The moisture percentage is not statistically different; both samples present low moisture content. The ashes are higher in the C15 and C20 formulation, indicating a 3.5–4.2-fold increase compared to the control sample. The fat content is maintained in both formulations, probably because this ingredient is not related to flour incorporation or substitution. Nevertheless, crude fiber increases 13.8 times with GPF incorporation in C15 and 31.6-fold in C20.

Table 3.

Proximal characterization of different cookie formulations.

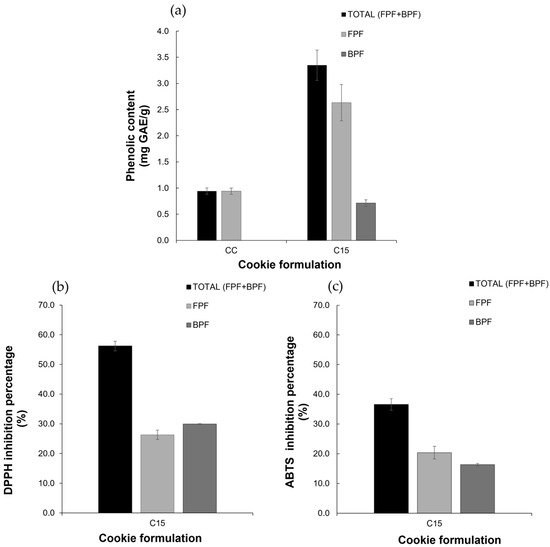

3.3. Bioactive Characterization

Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Capacity

The phenolic content in the cookie formulations is presented in Figure 3a. The FPF analysis reveals that CC (0.94 ± 0.06 mg GAE/g) exhibits lower phenolic content than C15 (2.63 ± 0.35 mg GAE/g), while BPF presents notable differences with 0.71 mg GAE/g for C15 and no detection for CC.

Figure 3.

Bioactive characterization in control cookie (CC) and cookie with 15% of GPF (C15) formulation: (a) phenolic content; (b) DPPH assay; (c) ABTS assay.

The GPF presents an antioxidant capacity of 95.47% of DPPH radical inhibition. Figure 3b and Figure 3c show the antioxidant capacity in formulated cookies in DPPH and ABTS assays, respectively. For the DPPH inhibition assay, sample C15 shows significant antioxidant activities in FPF (26.28 ± 1.55% radical inhibition) and BPF (29.94 ± 0.10% radical inhibition), with null activities in CC. During the ABTS inhibition assay, the FPF in C15 cookies shows (20.38 ± 2.14% radical inhibition), while BPF shows (16.32 ± 0.40% radical inhibition). The CC presents lower antioxidant capacity (1.54 ± 0.61% radical inhibition) in FPF, without antioxidant activity in BPF.

4. Discussion

Flour hydration properties are a key factor for their use in the food industry, as they are directly related to the functional and quality properties of bakery products [38]. Also, characteristics such as flavor, texture, and odor in cookies, cakes, and donuts are attributed to the oil retention capacity of the flours [39]. Other studies report similar WRC values in GPF from the Syrah variety, 1.72–1.86 g/g. At the same time, the ORC reveals differences between GPF dried at various temperatures, specifically 0.95 and 1.25 g/g at 55 °C and 75 °C, respectively [40]. GPF is a fiber-rich product that allows for physicochemical phenomena such as water absorption and adsorption, but also retains some non-bound water [41]. The hydroxyl (-OH) groups in the polysaccharide structure are responsible for interactions with water, forming hydrogen bonds [42]. The ORC is normally related to the non-polar side chains in molecules, such as proteins, cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose, which normally bind to hydrocarbon structures in lipids, promoting micelle formation [40,43]. Protein–oil interaction includes hydrophobic, electrostatic, and hydrogen bonds, which are essential to provide stability, where proteins with more hydrophobic regions show major oil retention [44]. Glutenin in WF and WWF shows these characteristics, facilitating the oil–flour interaction, and starchy components promote oil sorption [45,46], which could explain the high ORC in WF.

The hydration levels of flours are directly related to particle size. In fine particles, absorption rates and swelling capacities are higher [47]. As the particles are finer, a larger surface interaction area exists, generating major viscosity, which is beneficial during the cooking process [48,49]. The swelling effect is attributed to the soluble (pectin and hemicellulose) and insoluble fibers (cellulose and lignin) present in flour [50,51,52], whose hydrophilic capacity enables reticule formation with water-trapping activity [42,53]. Other classes of fruit pomaces have been employed in the elaboration of cookies, showing elevated SCs, which normally relate to the fiber content in non-conventional flours. Naseem et al. 2024 [54] elaborated cookies with 0, 5, 10, and 15% of apple pomace flour (APF). The APF shows a high SWC (4.66 ± 0.08 g/g) and generates a low-hardness product. The hardness diminishes as elevated quantities of APF are used [54]. Similar results were reported by Kuchtová et al. 2018, when using GPF in a cookie formulation [21]. Swelling capacities play a key role in texture, structure, and product volume in bakery products, especially in those where the dough or paste needs to maintain its form during the baking process [55,56]. In the present work, the GPFs present similar SWCs; therefore, the dough characteristics could remain adequate after their incorporation.

The foaming capacity affects the consistency and appearance of foods due to the formation of air bubbles [57]. Foam production requires a rearrangement of protein moieties, with the polar sections moving to water and non-polar sections to the non-aqueous phases until they form a stabilizing film around the air bubbles to avoid coalescence. Gluten is often involved in food-foam properties [58]. Foam stability is influenced by surfactant capacities in samples, but also is involved in cohesive, stable, and viscoelastic film formation, which is promoted by multiple intermolecular interactions [59]. The protein content in GP is normally around 6–15% depending on the grape variety. Grape proteins are distributed in the pulp, skin, and seeds. GP proteins possess high glutamic and aspartic acid contents, similarly to cereal proteins; nevertheless, skin proteins are rich in alanine and lysine, while seed proteins lack these amino acids [60]. Also, seed proteins are characterized by high hydrophobicity in their amino acid composition [61]. The foaming properties in proteins are mainly related to their adsorption rate, which depends on protein concentration, molecular weight, and structure [62]. GPF may contain a low protein quantity due to the small number of seeds in this agro-industrial waste; in addition, the seeds are rich in storage proteins with elevated molecular mass and a highly hydrophobic character, which could interfere with the unfolding and adsorption behavior needed for foaming activities.

Alvarez-Ossorio et al. 2022 [61] report that protein isolate from grape seeds does not show foaming properties at pH 3, due to its proximity to the isoelectric point. The foaming properties improved at higher pH (until ~7.0) and decreased at pH 8 and 9 [61]. The acidic nature of GPFs could be related to the absence of foam due to acid pH’s influence on the minimal protein charge, provoking reduced interfacial adsorption [62,63]. The real foaming properties in GPF could not be fully appreciated due to GPF’s natural pH, but could be enhanced during cookie formulation. Further analyses with flour and GPF mixtures are needed to evidence the real contribution of GPF in multiple techno-functional assays, and should be addressed in future studies. Zhou et al. 2011 analyze the foaming properties in grape seed protein (GSP) and report low foaming capacities of 0.28 mL/mL at pH6, compared to ~3.25 mL/mL of soybean protein (SBP) at the same pH [64]. Nevertheless, other GPF components could enhance foam stability. Diaz et al. 2022 show that polyphenol-rich blueberry extracts and Whey Protein Isolate (WPI) generate stable foam with smaller-sized bubbles than standard WPI foams [65]. Yadav et al. 2012 [66] made cookies with WF, banana, and chickpea flour (CPF). They observe that CPF presents an elevated FC (35.9 ± 0.01%) and considerable FE (97.5 ± 0.03%), with effects on the final product’s texture. A higher range of CPF substitutions produces cookies with elevated fracture resistance (21.1 ± 0.28 N) [66]. Proteins and starch could interact through hydrogen bonds, which stimulate the product’s hardness [67,68]. The interactions could retard the starch hydration with a compact dough in formulation [69].

The pH of food is important due to its effect on quality, security, and uniformity parameters. The GPF presents a considerably acidic pH compared with the slightly acidic pH in WF. Other authors report GPF pH near 3.3 from the variety Benitaka. Low pH in food material could influence its microbiological stability. Normally, yeast and fungi grow at a pH near 4.5–5.0, and bacteria between 6.5 and 7.0 [70]. Nogueira et al. 2022 [71] report similar acidic content, with 5.60 g tartaric acid/100 g in grape extracts. The authors relate the elevated acidity to the presence of an elevated number of organic acids in grapes and the macerating process in wine, including malic, citric, succinic, lactic, acetic, and tartaric acid [71].

The characteristic tonality in GPF could be attributed to the presence of molecules like anthocyanins, a group of phenolic pigments that exhibit red, purple, and blue colors in grapes [72]. These molecules have the capacity to form co-pigments when they interact with other phenolic compounds in grape pomace, like flavonoids or phenolic acids, promoting an intensification in color as well as higher stability [73]. Color changes in fortified cookies are derived from the addition of colored compounds present in GPFs as previously mentioned, as well as their transformation during processing. The polyphenolic molecules in GPF serve as a substrate for polyphenol oxidase enzymes, which, in the presence of oxygen, transform single phenolic units into diphenols through a hydroxylation process for further the production of quinones, which exhibit a brown color [22]. Also, the browning effect could be driven by caramelization and Maillard reactions, which are associated with temperature application [74].

Emerging food development is complex. The choice of ingredients demands the integration of scientific knowledge, nutritional requirements, and sensory trials. During the present study, the selected rates of GPF are supported by an extended revision of GPF-formulated cookies’ ingredients; however, the lack of a sensory evaluation represents a limitation. The sensory analysis will remain as a further perspective to complement the formulation; however, proximal and bioactive characterization also contribute important insights into functional food development when trying to maximize the consumer benefits.

The moisture in foods is directly related to shelf life and flavor. Low-moisture-content foods are stable against oxidation reactions and microbial growth, facilitating their handling and transport [75]. Jofre et al. 2024, formulated cookies, employing grape pomace flour, bream gum, and cassava flour; the proximal analysis shows moisture near 3.99–3.61% and ash values ranging from 0.30 to 0.39% [76]. Fontana et al. 2024, employed wheat flour and grape pomace flour, producing cookies with 7.37% of moisture and 1.59% ash [23]. Final moisture in a cookie product is related to several factors, including the origin of ingredients and their capacity to retain water, as well as the product’s thickness, baking time, and temperature. GPF is a mineral-rich product, and its mineral content changes depending on the part of the grape that is used, crop variety, and, especially, the characteristics of the cultivated land, as well as the class of fertilizers employed [77]. GPF is a product with important quantities of multiple polysaccharides, like pectin, cellulose, hemicellulose, xyloglucans, or arabinan, distributed in a complex network with protein, lignin, and other polyphenolic molecules to form the plant–cell wall [13,78]. The fiber content in a foodstuff could be enhanced through the incorporation of GPF.

Maner et al. 2017, reported 0.305 and 0.460 mg GAE/g for the TPC analysis in cookies with 15 and 20% of added GRP from the Cabernet Sauvignon variety [24], while Rocchetti et al. 2021, reported ~1.2 mg GAE/g in TPC in the free polyphenolic fraction and ~0.05 mg GAE/g in a bound fraction for bread with 10% of GP of the Corvina variety [25]. The GPF addition enhanced the phenolic content. The grapes and seeds of the Cabernet Sauvignon variety contain polyphenolic compounds like flavonoids (catechin, epicatechin, anthocyanin), non-flavonoid molecules (gallic acid), flavanols, flavan-3-ols, and procyanidins, which are linked to several biological activities, including antioxidant capacity [79]. The CC cookie shows a slightly phenolic content with low antioxidant capacity. Phenolic content in wheat has been previously reported. The main portion corresponds to the free phenolics fraction and is most abundant in whole grains, being extensively distributed in bran, but also present in white flour, and commonly understudied [80]. The Folin–Ciocalteu reaction could also be attributed to contamination during the milling process (small amounts of bran grain), as well as the occurrence of other antioxidant substances. Other authors also quantified low phenolic and antioxidant capacity in control formulations [24,80].

The GPF antioxidant capacity was previously documented—Mohamed Ahmed et al. 2020, analyzed ten different Turkish varieties of Grape pomaces with DPPH inhibition percentages of 71.18–98.47% [77]. The authors link the potent antioxidant activity in GPFs to the presence of phenolic compounds in grapes, which are normally affected by several factors, including cultivar, climate, cultivation practices, or extraction techniques. Grape pomace is a by-product with strong antioxidant properties whose incorporation could be considered in circular economic strategies.

The determination of antioxidant capacities in food and natural extracts is crucial to evaluating the potential health benefits of dietary incorporation in matrices like fiber-rich by-products. Antioxidants perform a key role in the prevention of cell damage caused by free radicals [81]. In the case of antiradical assays, Karnopp et al. 2015, obtained 19.31% DPPH radical inhibition in a cookie formulation using 20% of organic Bordeaux grape pomace and 50% of whole-wheat flour [26]. Both radical scavenging assays could help to evaluate different classes of antioxidant molecules. Normally, the ABTS assay helps to assess antioxidant compounds with hydrophilic, lipophilic, and highly pigmented molecules, while the DPPH assay’s applicability is mainly directed to hydrophobic systems, where radical solubility is performed in organic solvents [82]. BPF in by-products has received attention recently due to the lack of extensive studies on its antioxidant potential. BPFs are strongly attached to other molecules (e.g., lignin, hemicellulose, and other cell wall components), and therefore are not easily extractable by traditional methods [27,28]. The FPF and BPF possess different antioxidant capacities, mainly attributed to the nature of the molecule, with stronger activities being reported for BPF [27], but also related to the radical scavenging assay affinity. One of the key challenges in the incorporation of highly polyphenolic matrices into bakery products is their thermal stability, due to the requirement for temperatures above 60 °C, and BPF could provide a solution to this constraint. BPFs in food matrices could change the phenolic fraction released in the intestine [83]. Cell wall polyphenols could be further released by different gastrointestinal procedures, including microbiome action (e.g., Clostridium sp., Eubacterium sp.), which transforms complex polyphenolic compounds into simple molecules [84], while undergoing other biochemical transformations (e.g., de-glycosylation, de-hydroxylation, C-ring fission or de-methylation, among others) [83]. The produced molecules are moved into enterocytes by specific transporters (SGLT1), where they are hydrolyzed into absorbable aglycons [84]. This could provide some health benefits at the intestinal level, including local antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity, which can avoid or reduce oxidative stress in the colon [85]; phenolic biotransformation by gut microbiota, which enhances its bioavailability and promotes beneficial effects at other systemic levels, such as microbiome modulation and promoting the growth of probiotics strains as Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus helveticus, or Bifidobacterium longum, and could also inhibit the dissemination of pathogenic strains such as Helicobacter pylori [83]. Despite this, the in vivo real potential of BPF bioactive coverage or its health impact has not been extensively studied, and nor has the synergistic effect produced in high-fiber foods.

5. Conclusions

GPF’s techno-functional properties provide it with a unique character compared with traditional flours, with special positive features in water-binding activity, but its oil-binding and foaming properties remain challenging. Despite this, the incorporation of GPF in cookie formulation promotes higher quantities of key health-related molecules such as ash, fiber, and antioxidants, which remain in the formulation after the baking process. The study provides information about BPF, which is commonly understudied in functional foods. The BPF in the selected cookie formulation possesses important antioxidant capacity and represents a topic of interest for further studies; its nature could be linked to the preservation of phenolic molecules in the food matrix with thermal procedures, as well as gastrointestinal availability and release. The addition of GP in emerging food formulations could contribute to solving actual environmental and health issues.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.E.G.-C., G.A.M.-M., C.T.-L. and N.R.-G.; methodology, N.R.-G., C.E.G.-C., J.A.M.-V. and C.T.-L., software, G.A.M.-M., M.M.-C. and M.L.Q.-B. validation, A.Y.H.-A., M.L.Q.-B., M.M.-C. and C.T.-L.; formal analysis, J.A.M.-V., N.R.-G. and C.T.-L., investigation, N.R.-G. and C.T.-L., resources, R.G.-G. and C.T.-L., data curation, N.R.-G., C.T.-L. and R.G.-G. writing—original draft preparation, G.A.M.-M., C.E.G.-C., N.R.-G. and C.T.-L.; writing—review and editing, G.A.M.-M. and R.G.-G.; visualization, G.A.M.-M., A.Y.H.-A. and N.R.-G.; supervision, N.R.-G. and C.T.-L.; project administration, N.R.-G. and C.T.-L.; funding acquisition, N.R.-G., R.G.-G. and C.T.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support from the Biologicals Sciences Faculty, and Research Center and Ethnobiological Garden (CIJE-UAdeC) from Autonomous University of Coahuila, Coahuila, Mexico.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GP | grape pomace |

| L | liters |

| Kg | kilograms |

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid |

| DPPH | 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl |

| µm | micrometer |

| GPF | grape pomace flour |

| WRC | water retention capacity |

| ORC | oil retention capacity |

| SWC | swelling capacity |

| V0 | initial sample volume (SWC assay) |

| V1 | settled particles’ volume (SWC assay) |

| min | minute |

| mL | milliliter |

| g | grams |

| FC % | foaming capacity percentage |

| FS% | foaming stability percentage |

| pH | hydrogen potential |

| w-w % | weight per weight percentage |

| g/meq | grams per milliequivalent |

| °C | centigrade |

| CC | control cookie formulation |

| C15 | cookie formulation with 15% of grape pomace flour |

| C20 | cookie formulation with 20% of grape pomace flour |

| AOAC | Association of Official Analytical Chemists |

| FPF | free phenolic fraction |

| BPF | bound phenolic fraction |

| M | molar |

| TPC | total phenolic content |

| GAE mg/g sample | gallic equivalent milligrams per gram of sample |

| AC | antioxidant capacity |

| µL | microliter |

| nm | nanometer |

| mM | millimolar |

| Ac | control absorbance |

| As | sample absorbance |

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| HSD | honest significant difference |

| ± | plus, minus |

| g/g | gram per gram |

| WF | wheat flour |

| WWF | whole-wheat flour |

| -OH | hydroxyl group |

| APF | apple pomace flour |

| GSP | grape seed protein |

| SBP | soybean protein |

| WPI | whey protein isolate |

| CPF | chickpea flour |

| N | Newton |

References

- Sinrod, A.J.G.; Shah, I.M.; Surek, E.; Barile, D. Uncovering the Promising Role of Grape Pomace as a Modulator of the Gut Microbiome: An in-Depth Review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkitasamy, C.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, R.; Pan, Z. Grapes. In Integrated Processing Technologies for Food and Agricultural by-Products; Pan, Z., Zhang, R., Steven, Z., Eds.; Elsevier: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 133–163. [Google Scholar]

- Beres, C.; Costa, G.N.S.; Cabezudo, I.; da Silva-James, N.K.; Teles, A.S.C.; Cruz, A.P.G.; Mellinger-Silva, C.; Tonon, R.V.; Cabral, L.M.C.; Freitas, S.P. Towards Integral Utilization of Grape Pomace from Winemaking Process: A Review. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkinomagoulos, E.; Kandylis, P. Grape Pomace, an Undervalued by-Product: Industrial Reutilization within a Circular Economy Vision. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 22, 739–773. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, A.D.; Ballesteros, M.; Negro, M.J. Biorefineries for the Valorization of Food Processing Waste. In The Interaction of Food Industry and Environment; Galanakis, C.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 155–190. [Google Scholar]

- Gazzola, D.; Vincenzi, S.; Gastaldon, L.; Tolin, S.; Pasini, G.; Curioni, A. The Proteins of the Grape (Vitis vinifera L.) Seed Endosperm: Fractionation and Identification of the Major Components. Food Chem. 2014, 155, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Astorga, M.; Molina-Quijada, C.C.; Ovando-Martínez, M.; Leon-Bejarano, M. Orujo de Uva: Más Que Un Residuo, Una Fuente de Compuestos Bioactivos. Epistemus 2022, 16, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhu, M.; Shi, T.; Guo, C.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xie, M. Recovery of Dietary Fiber and Polyphenol from Grape Juice Pomace and Evaluation of Their Functional Properties and Polyphenol Compositions. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alahmari, L.A. Dietary Fiber Influence on Overall Health, with an Emphasis on CVD, Diabetes, Obesity, Colon Cancer, and Inflammation. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1510564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, I.S.; Orfila, C. Dietary Fiber in the Prevention of Obesity and Obesity-Related Chronic Diseases: From Epidemiological Evidence to Potential Molecular Mechanisms. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 63, 8752–8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo-López, J.E.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; Ascacio-Valdes, J.A.; Contreras Esquivel, J.C.; Torres-León, C.; Rúelas-Chácon, X.; Aguilar, C.N. Antioxidant Dietary Fiber Sourced from Agroindustrial Byproducts and Its Applications. Foods 2022, 12, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, H.; Xu, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cao, Y.; Xing, X. Research Progress on Classification, Sources and Functions of Dietary Polyphenols for Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Diseases. J. Future Foods 2023, 3, 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Beres, C.; Freitas, S.P.; Godoy, R.L.d.O.; de Oliveira, D.C.R.; Deliza, R.; Iacomini, M.; Mellinger-Silva, C.; Cabral, L.M.C. Antioxidant Dietary Fibre from Grape Pomace Flour or Extract: Does It Make Any Difference on the Nutritional and Functional Value? J. Funct. Foods 2019, 56, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Lan, J.C.-W.; Jambrak, A.R.; Chang, J.-S.; Lim, J.W.; Khoo, K.S. Upcycling Fruit Waste into Microalgae Biotechnology: Perspective Views and Way Forward. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2024, 8, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-León, C.; Ramírez-Guzman, N.; Londoño-Hernandez, L.; Martínez-Medina, G.A.; Díaz-Herrera, R.; Navarro-Macias, V.; Alvarez-Pérez, O.B.; Picazo, B.; Villarreal-Vázquez, M.; Ascacio-Valdes, J.; et al. Food Waste and Byproducts: An Opportunity to Minimize Malnutrition and Hunger in Developing Countries. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, O.O.; Akinnusi, E.; Ottu, P.O.; Bridget, K.; Oyubu, G.; Ajiboye, S.A.; Waheed, S.A.; Collette, A.C.; Adebimpe, H.O.; Nwokafor, C.V. The Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on Cardiovascular Diseases and Cancer: Epidemiological and Mechanistic Insights. Asp. Mol. Med. 2025, 5, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí del Moral, A.; Calvo, C.; Martínez, A. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Obesity-a Systematic Review. Nutr. Hosp. 2021, 38, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A. Concept of a Nutritious Food: Toward a Nutrient Density Score. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, M.; Chudasama, M.; Kataria, A.; Chauhan, K. Cookies. In Cereal-Based Food Products; Shah, M.A., Valiyapeediyekkal Sunooj, K., Mir, S.A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Blanch, G.P.; Ruiz del Castillo, M.L. Effect of Baking Temperature on the Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Black Corn (Zea mays L.) Bread. Foods 2021, 10, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchtová, V.; Kohajdová, Z.; Karovičová, J.; Lauková, M. Physical, Textural and Sensory Properties of Cookies Incorporated with Grape Skin and Seed Preparations. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2018, 68, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mildner-Szkudlarz, S.; Bajerska, J.; Zawirska-Wojtasiak, R.; Górecka, D. White Grape Pomace as a Source of Dietary Fibre and Polyphenols and Its Effect on Physical and Nutraceutical Characteristics of Wheat Biscuits. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2012, 93, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, M.; Murowaniecki Otero, D.; Pereira, A.M.; Santos, R.B.; Gularte, M.A. Grape Pomace Flour for Incorporation into Cookies: Evaluation of Nutritional, Sensory and Technological Characteristics. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2024, 22, 850–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maner, S.; Sharma, A.K.; Banerjee, K. Wheat Flour Replacement by Wine Grape Pomace Powder Positively Affects Physical, Functional and Sensory Properties of Cookies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 87, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchetti, G.; Rizzi, C.; Cervini, M.; Rainero, G.; Bianchi, F.; Giuberti, G.; Lucini, L.; Simonato, B. Impact of Grape Pomace Powder on the Phenolic Bioaccessibility and on in vitro Starch Digestibility of Wheat Based Bread. Foods 2021, 10, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnopp, A.R.; Figueroa, A.M.; Los, P.R.; Teles, J.C.; Simões, D.R.S.; Barana, A.C.; Kubiaki, F.T.; de Oliveira, J.G.B.; Granato, D. Effects of Whole-Wheat Flour and Bordeaux Grape Pomace (Vitis labrusca L.) on the Sensory, Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Cookies. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 35, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Franquesa, A.; Casertano, M.; Tresserra-Rimbau, A.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Torres-León, C. Recent Advances in Bio- Based Extraction Processes for the Recovery of Bound Phenolics from Agro-Industrial by-Products and Their Biological 535 Activity. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 10643–10667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-León, C.; Ramírez-Guzmán, N.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.; Serna-Cock, L.; dos Santos Correia, M.T.; Contreras-Esquivel, J.C.; Aguilar, C.N. Solid-State Fermentation with Aspergillus niger to Enhance the Phenolic Contents and Antioxidative Activity 538 of Mexican Mango Seed: A Promising Source of Natural Antioxidants. LWT 2019, 112, 108236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, M.C.; Simal, S.; Rossello, C.; Femenia, A. Effect of Air-Drying Temperature on Physico-Chemical Properties of Dietary Fibre and Antioxidant Capacity of Orange (Citrus aurantium v. Canoneta) by-Products. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 1014–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo López, J.E.; Flores Gallegos, A.C.; Rodríguez Jasso, R.M.; Aguilar González, C.N.; Serna Cock, L. Nutritional and Techno Functional Properties of Pseudocereal Bars Added with Soy, Mango and Pomegranate. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2023, 73, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, U.; Gani, A.; Ahmad, M.; Shah, U.; Baba, W.N.; Masoodi, F.A.; Maqsood, S.; Gani, A.; Wani, I.A.; Wani, S.M. Characterization of Cookies Made from Wheat Flour Blended with Buckwheat Flour and Effect on Antioxidant Properties. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 6334–6344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, B.L.; Deaquiz Oyola, Y.A. Caracterización de Parámetros Fisicoquímicos En Frutos de Mora (Rubus alpinus Macfad). Acta Agron. 2016, 65, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, V.; Blejan, A.M.; Codină, G.G. Use of Bilberry and Blackcurrant Pomace Powders as Functional Ingredients in Cookies. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šťastná, K.; Sumczynski, D.; Yalcin, E. Nutritional Composition, in vitro Antioxidant Activity and Phenolic Profile of Shortcrust Cookies Supplemented by Edible Flowers. Foods 2021, 10, 2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-León, C.; de Azevedo Ramos, B.; dos Santos Correia, M.T.; Carneiro-da-Cunha, M.G.; Ramirez-Guzman, N.; Alves, L.C.; Brayner, F.A.; Ascacio-Valdes, J.; Álvarez-Pérez, O.B.; Aguilar, C.N. Antioxidant and Anti-Staphylococcal Activity of Polyphenolic-Rich Extracts from Ataulfo Mango Seed. LWT 2021, 148, 111653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molyneux, P. The Use of the Stable Free Radical Diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH) for Estimating Antioxidant Activity. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2004, 26, 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Berton, B.; Scher, J.; Villieras, F.; Hardy, J. Measurement of Hydration Capacity of Wheat Flour: Influence of Composition and Physical Characteristics. Powder Technol. 2002, 128, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Maximiuk, L.; Fenn, D.; Nickerson, M.T.; Hou, A. Development of a Method for Determining Oil Absorption Capacity in Pulse Flours and Protein Materials. Cereal Chem. 2020, 97, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldan, Y.; Riveros, M.; Fabani, M.P.; Rodriguez, R. Grape Pomace Powder Valorization: A Novel Ingredient to Improve the Nutritional Quality of Gluten-Free Muffins. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 9997–10009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongeau, R.; Brooks, S. Dietary Fiber: Properties and Sources in the Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Caballero, B., Finglas, P.M., Toldra, F., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 1813–1822. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, S.W.; Wu, Y.; Ding, H. The Range of Dietary Fibre Ingredients and a Comparison of Their Technical Functionality. In Fibre-Rich and Wholegrain Foods; Delcour, J.A., Poutanen, K., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 96–119. [Google Scholar]

- Benitez, V.; Rebollo-Hernanz, M.; Hernanz, S.; Chantres, S.; Aguilera, Y.; Martin-Cabrejas, M.A. Coffee Parchment as a New Dietary Fiber Ingredient: Functional and Physiological Characterization. Food Res. Int. 2019, 122, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sharan, S.; Rinnan, Å.; Orlien, V. Survey on Methods for Investigating Protein Functionality and Related Molecular Characteristics. Foods 2021, 10, 2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopf, M.; Wehrli, M.C.; Becker, T.; Jekle, M.; Scherf, K.A. Fundamental Characterization of Wheat Gluten. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wen, J.; Fan, X.; Zheng, X. Control of the Oil Content of Fried Dough Sticks through Modulating Structure Change by Reconstituted Gluten Fractions. Food Chem. 2024, 455, 139909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyeyinka, S.A.; Bassey, I.-A. Composition, Functionality, and Baking Quality of Flour from Four Brands of Wheat Flour. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2025, 23, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jima, B.R.; Abera, A.A.; Kuyu, C.G. Effect of Particle Size on Compositional, Functional, Pasting, and Rheological Properties of Teff [Eragrostis Teff (Zucc.) Trotter] Flour. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmjou, A.; Simon, G.P.; Wang, H. Effect of Particle Size on the Performance of Forward Osmosis Desalination by Stimuli-Responsive Polymer Hydrogels as a Draw Agent. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 215, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, Z.; Boye, J.I. Novel Food and Industrial Applications of Pulse Flours and Fractions. In Pulse Foods: Processing, Quality and Nutraceutical Applications; Tiwari, B.K., Gowen, A., McKenna, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 283–323. [Google Scholar]

- Spinei, M.; Oroian, M. The Potential of Grape Pomace Varieties as a Dietary Source of Pectic Substances. Foods 2021, 10, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, W.; Fu, G.; Liu, C.; Zhong, Y.; Zhong, J.; Luo, S.; Liu, W. Effects of Cellulose, Lignin and Hemicellulose on the Retrogradation of Rice Starch. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2014, 20, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero Álvarez, E.; González Sánchez, P. La Fibra Dietética. Nutr. Hosp. 2006, 21, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Naseem, Z.; Bhat, N.A.; Mir, S.A. Valorisation of Apple Pomace for the Development of High-Fibre and Polyphenol-Rich Wheat Flour Cookies. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Martinez, M.M.; Bohrer, B.M. The Compositional and Functional Attributes of Commercial Flours from Tropical Fruits (Breadfruit and Banana). Foods 2019, 8, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Azlie, N.A.; Jailani, F. Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Bario Rice Varieties as Potential Gluten-Free Food Ingredients. J. Gizi Pangan 2024, 19, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, H.; Shad, M.A.; Mehmood, R.; Rehman, T.; Munir, H. Comparative Evaluation of Functional Properties of Some Commonly Used Cereal and Legume Flours and Their Blends. J. Food Allied Sci. 2015, 1, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zayas, J.F. Foaming Properties of Proteins. In Functionality of Proteins in Food; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 260–309. [Google Scholar]

- Bertsch, P.; Böcker, L.; Mathys, A.; Fischer, P. Proteins from Microalgae for the Stabilization of Fluid Interfaces, Emulsions, and Foams. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 108, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Lomillo, J.; González-SanJosé, M.L. Applications of Wine Pomace in the Food Industry: Approaches and Functions. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Ossorio, C.; Orive, M.; Sanmartín, E.; Alvarez-Sabatel, S.; Labidi, J.; Zufia, J.; Bald, C. Composition and Techno-Functional Properties of Grape Seed Flour Protein Extracts. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuropatwa, M.; Tolkach, A.; Kulozik, U. Impact of pH on the Interactions between Whey and Egg White Proteins as Assessed by the Foamability of Their Mixtures. Food Hydrocoll. 2009, 23, 2174–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wu, Z.; Wangb, Y.; Ding, L.; Wang, Y. Role of pH-Induced Structural Change in Protein Aggregation in Foam Fractionation of Bovine Serum Albumin. Biotechnol. Rep. 2016, 9, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, T.; Zhang, T.; Liu, W.; Zhao, G. Physicochemical Characteristics and Functional Properties of Grape (Vitis vinifera L.) Seeds Protein. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, J.T.; Foegeding, E.A.; Stapleton, L.; Kay, C.; Iorizzo, M.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Lila, M.A. Foaming and Sensory Characteristics of Protein-Polyphenol Particles in a Food Matrix. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 123, 107148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.B.; Yadav, B.S.; Dhull, N. Effect of Incorporation of Plantain and Chickpea Flours on the Quality Characteristics of Biscuits. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 207–213. [Google Scholar]

- Mulla, M.F.Z.; Mullins, E.; Lynch, R.; Gallagher, E. A Mixture Design Approach to Investigate the Impact of Raw and Processed Chickpea Flour on the Techno-Functional Properties in a Bakery Application. LWT 2025, 229, 118206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriya, M.; Rajput, R.; Reddy, C.K.; Haripriya, S.; Bashir, M. Functional and Physicochemical Characteristics of Cookies Prepared from Amorphophallus paeoniifolius Flour. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 2156–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Rooyen, J.; Simsek, S.; Oyeyinka, S.A.; Manley, M. Wheat Starch Structure–Function Relationship in Breadmaking: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 2292–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, E.C.; Uchôa-Thomaz, A.M.A.; Carioca, J.O.B.; de Morais, S.M.; de Lima, A.; Martins, C.G.; Alexandrino, C.D.; Ferreira, P.A.T.; Rodrigues, A.L.M.; Rodrigues, S.P. Chemical Composition and Bioactive Compounds of Grape Pomace (Vitis vinifera L.), Benitaka Variety, Grown in the Semiarid Region of Northeast Brazil. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 34, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, G.F.; Soares, I.H.B.T.; Soares, C.T.; Fakhouri, F.M.; de Oliveira, R.A. Development and Characterization of Arrowroot Starch Films Incorporated with Grape Pomace Extract. Polysaccharides 2022, 3, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Mu, L.; Yan, G.-L.; Liang, N.-N.; Pan, Q.-H.; Wang, J.; Reeves, M.J.; Duan, C.-Q. Biosynthesis of Anthocyanins and Their Regulation in Colored Grapes. Molecules 2010, 15, 9057–9091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinei, M.; Oroian, M. Characterization of Băbească Neagră Grape Pomace and Incorporation into Jelly Candy: Evaluation of Phytochemical, Sensory, and Textural Properties. Foods 2023, 13, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agcam, E. A Kinetic Approach to Explain Hydroxymethylfurfural and Furfural Formations Induced by Maillard, Caramelization, and Ascorbic Acid Degradation Reactions in Fruit Juice-Based Mediums. Food Anal. Methods 2022, 15, 1286–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M. Oxidative Stability and Shelf Life of Low-Moisture Foods. In Oxidative Stability and Shelf Life of Foods Containing Oils and Fats; Elsevier: London, UK, 2016; pp. 313–371. [Google Scholar]

- Jofre, C.M.; Campderrós, M.E.; Rinaldoni, A.N. Integral Use of Grape: Clarified Juice Production by Microfiltration and Pomace Flour by Freeze-Drying. Development of Gluten-Free Filled Cookies. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 4, 100583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Ahmed, I.A.; Özcan, M.M.; Al Juhaimi, F.; Babiker, E.F.E.; Ghafoor, K.; Banjanin, T.; Osman, M.A.; Gassem, M.A.; Alqah, H.A.S. Chemical Composition, Bioactive Compounds, Mineral Contents, and Fatty Acid Composition of Pomace Powder of Different Grape Varieties. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llobera, A.; Canellas, J. Dietary Fibre Content and Antioxidant Activity of Manto Negro Red Grape (Vitis vinifera): Pomace and Stem. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cerda-Carrasco, A.; López-Solís, R.; Nuñez-Kalasic, H.; Peña-Neira, Á.; Obreque-Slier, E. Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Capacity of Pomaces from Four Grape Varieties (Vitis vinifera L.). J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 1521–1527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.C.B.; da Silva Lima, L.R.; dos Santos D’Almeida, C.T.; Victorio, V.C.M.; Cameron, L.C.; Bourlieu-Lacanal, C.; Ferreira, M.S.L. Foodomics in Wheat Flour Reveals Phenolic Profile of Different Genotypes and Technological Qualities. LWT 2022, 153, 112519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez Ovando, A.; Mejía Reyes, J.D.; García Cabrera, K.E.; Velázquez Ovalle, G. Capacidad Antioxidante: Conceptos, Métodos de Cuantificación y Su Aplicación En La Caracterización de Frutos Tropicales y Productos Derivados. Rev. Colomb. Investig. Agroind. 2022, 9, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floegel, A.; Kim, D.-O.; Chung, S.-J.; Koo, S.I.; Chun, O.K. Comparison of ABTS/DPPH Assays to Measure Antioxidant Capacity in Popular Antioxidant-Rich US Foods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Rocchetti, G.; Gregorio, R.P.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Barba, F.J.; Oliveira, P.G.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Mosele, J.I.; Motilva, M.; Tomas, M. Functional Implications of Bound Phenolic Compounds and Phenolics–Food Interaction: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 811–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta-Estrada, B.A.; Gutierrez-Uribe, J.A.; Serna-Saldívar, S.O. Bound Phenolics in Foods. Food Chem. 2014, 152, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosele, J.I.; Macià, A.; Motilva, M.-J. Metabolic and Microbial Modulation of the Large Intestine Ecosystem by Non-Absorbed Diet Phenolic Compounds: A Review. Molecules 2015, 20, 17429–17468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.