1. Introduction

Wound healing is a highly coordinated biological process involving the sequential yet overlapping phases of hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [

1]. Disruption of these stages frequently leads to impaired tissue repair, particularly in wounds compromised by microbial colonization or elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [

2]. Chronic wounds, such as diabetic ulcers, venous leg ulcers, and pressure injuries, are characterized by persistent infection, sustained inflammation and oxidative stress, which collectively contribute to delayed granulation, extracellular matrix degradation, and impaired re-epithelialization [

3]. The wound microenvironment is frequently populated by pathogenic organisms, including

Staphylococcus aureus,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

Escherichia coli, and

Candida species, which are known for virulence, biofilm formation and antimicrobial resistance. Concurrently, excessive ROS accumulation in damaged tissue exacerbates inflammation and cellular injury, ultimately delaying the healing process [

4].

Conventional therapeutic approaches typically address either infection or oxidative stress, but most available agents provide only single-function activity [

5]. This limitation has driven increasing interest in multifunctional molecules capable of simultaneously reducing microbial burden and counteracting oxidative imbalance [

6]. Azole-based compounds, particularly those containing an imidazole moiety, represent a versatile platform for drug design due to their established antifungal activity and potential for structural modification [

7].

Ketoconazole is a widely prescribed antifungal imidazole; however, its poor aqueous solubility, restricted antibacterial spectrum and lack of intrinsic antioxidant activity limit its direct applicability in wound-healing [

8]. Recent studies in medicinal chemistry have demonstrated that targeted modification of azole scaffolds, particularly via hydrazone formation, can markedly enhance biological activity [

9]. Hydrazone derivatives often exhibit improved lipophilicity, optimized electron distribution, and increased hydrogen bonding capacity, facilitating stronger interactions with microbial membranes and reactive free radicals [

10]. These structural features are associated with enhanced antimicrobial potency, a broader spectrum of activity against resistant strains and the emergence of intrinsic antioxidant capabilities [

11]. Despite these advantages, the literature investigating ketoconazole-derived hydrazones or other analogues specifically designed for wound-care remains scarce. For instance, while ketoconazole has been investigated for its potential to reduce post-burn cortisol [

12], evidence regarding its ability to positively modify inflammatory or catabolic responses in burn injuries, remains inconclusive.

Furthermore, fungal invasion of deep tissues represents a major factor contributing to delayed wound healing, particularly in diabetic and burn patients. This often leads to prolonged hospitalization, increased morbidity, and, in severe cases, amputation. Depending on the type and severity of infection, as well as the anatomical site involved, four major classes of antifungal agents are currently employed: azoles, which inhibit ergosterol biosynthesis; echinocandins, which interfere with β-(1,3)-glucan synthesis in the fungal cell wall; polyenes, which bind to ergosterol and induce pore formation resulting in rapid intracellular ion leakage; and nucleoside analogues, which inhibit fungal DNA and RNA synthesis [

13]. Among these therapeutic options, azoles remain the cornerstone of fungal infection management. For systemic infection, fluconazole and itraconazole are commonly prescribed, whereas ketoconazole is used primarily for topical infections [

14,

15].

Recent research has increasingly highlighted the importance of antifungal therapy in wound management, particularly in chronic and diabetic wounds where fungal species frequently coexist with bacterial pathogens, impeding the healing process. In this context, antifungal azoles have been successfully explored as active components of advanced wound dressings. Fluconazole-loaded biomaterial systems, including hydroxyapatite-based hydrogels and alginate dressings, have demonstrated sustained drug release and effective antifungal activity against

Candida albicans, supporting the feasibility of azole incorporation into wound care platforms for local infection control [

16]. Moreover, dual-drug alginate dressings co-delivering fluconazole and ciprofloxacin have been developed to address mixed bacterial–fungal infections commonly encountered in diabetic foot ulcers, underscoring the growing need for multifunctional wound therapies [

17]. Beyond fluconazole, antifungal imidazoles such as miconazole or ketoconazole have attracted attention for their broader antimicrobial potential, particularly against Gram-positive bacteria, frequently implicated in wound infections, including those in which

Staphylococcus aureus is incriminated Preclinical studies have further suggested that certain azoles may influence wound healing parameters, including epithelialization and inflammatory responses, indicating that their role in wound therapy may extend beyond antifungal activity alone [

18]. Notably, previous research has reported the successful loading of ketoconazole into cotton-based and hydrogel wound dressings via β-cyclodextrin inclusion complexes, primarily to enhance its aqueous solubility and local availability [

19].

Despite these advances, most azole-based wound formulations rely on conventional antifungal agents that possess limited antibacterial efficacy and exert minimal impact on oxidative stress or tissue regeneration. Ketoconazole, while widely used in topical antifungal therapy, exemplifies this limitation; standard formulations primarily target fungal pathogens without significantly accelerating wound closure or collagen deposition. These observations underscore the urgent need for next-generation azole derivatives with enhanced multifunctionality.

Given the multifactorial pathology of chronic wounds, there is a critical need for therapeutic compounds that combine antimicrobial and antioxidant activities, within a single molecular entity [

5]. Such multifunctional agents are attractive candidates for incorporation into advanced wound-management platforms, including hydrogel dressings, electrospun nanofiber mats, polymeric films, and smart stimuli-responsive systems [

20,

21]. Consequently, the present work focuses on the design, synthesis, and in vitro evaluation of ketoconazole-based derivatives with improved antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. By integrating dual activities into a unified structural framework, this study aims to identify novel compounds with significant potential for modern wound-healing technologies application, thereby addressing the complex pathophysiology of infected wounds.

Beyond biological profiling, this study places significant emphasis on optimizing the synthetic pathway. A central objective was to develop a scalable and energy-efficient protocol that minimizes environmental impact. By employing mild reaction conditions and eliminating the need for solvent-intensive chromatographic purification, the proposed method aligns with green chemistry principles, offering a streamlined process characterized by high reproducibility and operational simplicity compared to conventional multi-step syntheses of pharmacological scaffolds.

2. Materials and Methods

Building upon our previous investigations involving aromatic aldehydes in various synthetic pathways aimed at yielding compounds with reduced toxicity [

22], the present study aims to modify the molecular scaffold of ketoconazole to mitigate its tissue toxicity while enhancing its therapeutic efficacy. The Schiff base derivative

K1, was synthesized following the procedure previously described by our group [

22]. Subsequently, this compound served as a key intermediate for the new series development. To this end, novel condensation products incorporating hydrazone moieties, were synthesized, designed to augment the antimicrobial potential of ketoconazole, while concurrently minimizing its cytotoxicity. The synthesis involved condensation reactions employing two aromatic aldehydes, specifically 4-nitrobenzaldehyde and 4-bromobenzaldehyde, followed by cyclization with chloroacetyl chloride to afford the target compounds, bearing a β-lactam ring.

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

All used chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade and were used as received without further purification. Hydrazine hydrate, chloroacetyl chloride, sulfuric acid, sodium phosphate, ammonium molybdate, sodium phosphate buffer, potassium ferricyanide, trichloroacetic acid, ferric chloride, 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl and dimethyl sulfoxide were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Ettlingen, Germany). For antimicrobial activity assays, standardized Mueller-Hinton medium, Sabouraud medium and sterile paper discs were used. Reagents for the cytotoxicity assessment (MTT assay), including Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with 1% PSN antibiotic mixture (penicillin, streptomycin, neomycin) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), were also obtained from Sigma Aldrich.

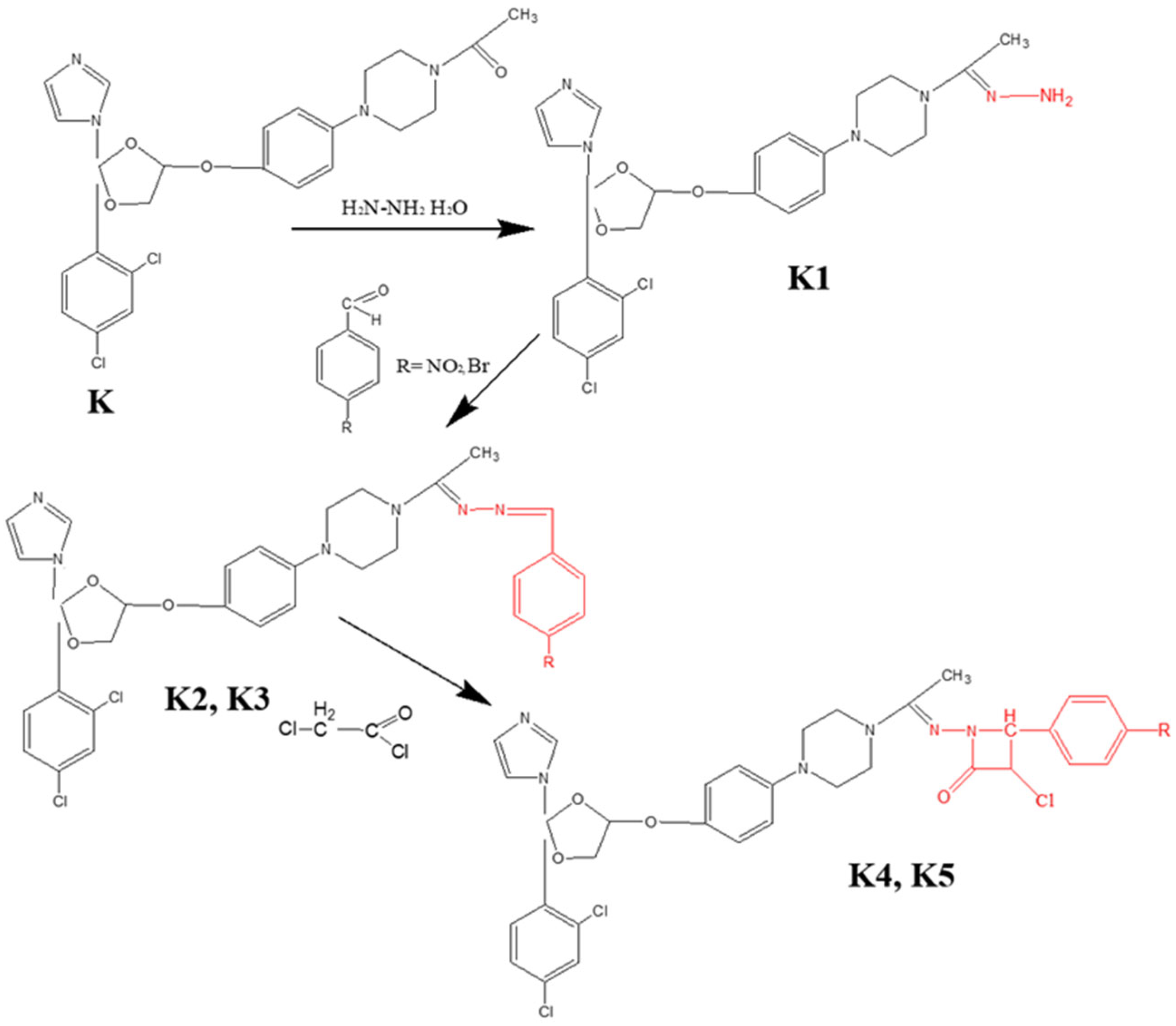

2.2. General Procedure for Obtaining Ketoconazole Condensation Hydrazones

The synthesis of the target derivatives involved a multi-step protocol starting with the conversion of the parent compound, ketoconazole, into the corresponding hydrazine (K1), followed by condensation with substituted benzaldehydes to yield hydrazone intermediates (K2, K3), and finally, cyclization to form the β-lactam derivatives (K4, K5).

Synthesis of Hydrazone Intermediates (

K2,

K3); Initially, ketoconazole was treated with an excess of hydrazine hydrate (1:3 molar ratio) under reflux for 12 h to obtain

K1. Subsequently,

K1 was condensed with 4-nitrobenzaldehyde (to yield

K2) or 4-bromobenzaldehyde (to yield

K3) in a 1:2 molar ratio. The reaction was conducted in absolute ethanol (50 mL) containing a catalytic amount of glacial acetic acid (2–3 drops). The mixture was refluxed for 8 h. The resulting precipitates were filtered, washed with distilled water, air-dried at room temperature, and purified by recrystallization [

23].

Synthesis of β-Lactam Derivatives (

K4,

K5); The hydrazone derivatives (

K2,

K3) were reacted with chloroacetyl chloride in the presence of triethylamine using 1,4-dioxane (30 mL) as the solvent. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h, after which the precipitated triethylamine hydrochloride was removed by filtration. The filtrate was then refluxed for 5 h. Upon completion, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting solid product was washed with water (20 mL), filtered, dried, and recrystallized from absolute ethanol to afford the final compounds

K4 and

K5 [

24].

Beyond the structural novelty of the derivatives K2–K5, the synthetic protocol employed highlights significant process improvements in terms of operational simplicity and efficiency. Unlike conventional functionalization strategies that often require harsh conditions or complex catalytic systems, this optimized procedure utilized mild reaction conditions to achieve the target compounds.

A key advantage of this protocol is the high atom economy and the efficiency of the purification process. The target compounds precipitated directly from the reaction mixture or were isolated via simple recrystallization, thereby eliminating the need for labor-intensive and solvent-consuming chromatographic separations. This approach not only improves the overall reaction yields but also aligns with sustainable chemistry principles by minimizing solvent waste and processing time.

2.3. Green Chemistry Metrics Assessment

The environmental impact and sustainability of the synthetic protocols were evaluated by calculating key Green Chemistry metrics: Atom Economy (AE), Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) and complete the Environmental Factor (E-Factor). These metrics are key mass-based metrices useful for the evaluation of the greenness of a synthetic process [

25,

26,

27]. Parameters were determined for each target compound (

K1–

K5) using the experimental data obtained from the optimization studies.

Atom Economy (AE) was calculated as a theoretical measure of the efficiency with which reactant atoms are incorporated into the final product, ignoring the reaction yield, according to Equation (1) [

26]:

Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) was computed to provide a realistic evaluation of the process efficiency, accounting for both the atom economy and the chemical yield. This metric represents the percentage of the mass of the reactants that remains in the final isolated product, calculated using Equation (2) [

26]:

The Environmental Factor (E-Factor) was determined to quantify the amount of waste generated per kilogram of product. In this study, the calculation included all reagents, reaction solvents, and solvents used during the work-up and purification steps, as described in Equation (3) [

28]. Ideally, an E-Factor of 0 represents zero waste, while typical values for pharmaceutical synthesis range between 25 and 100 [

28].

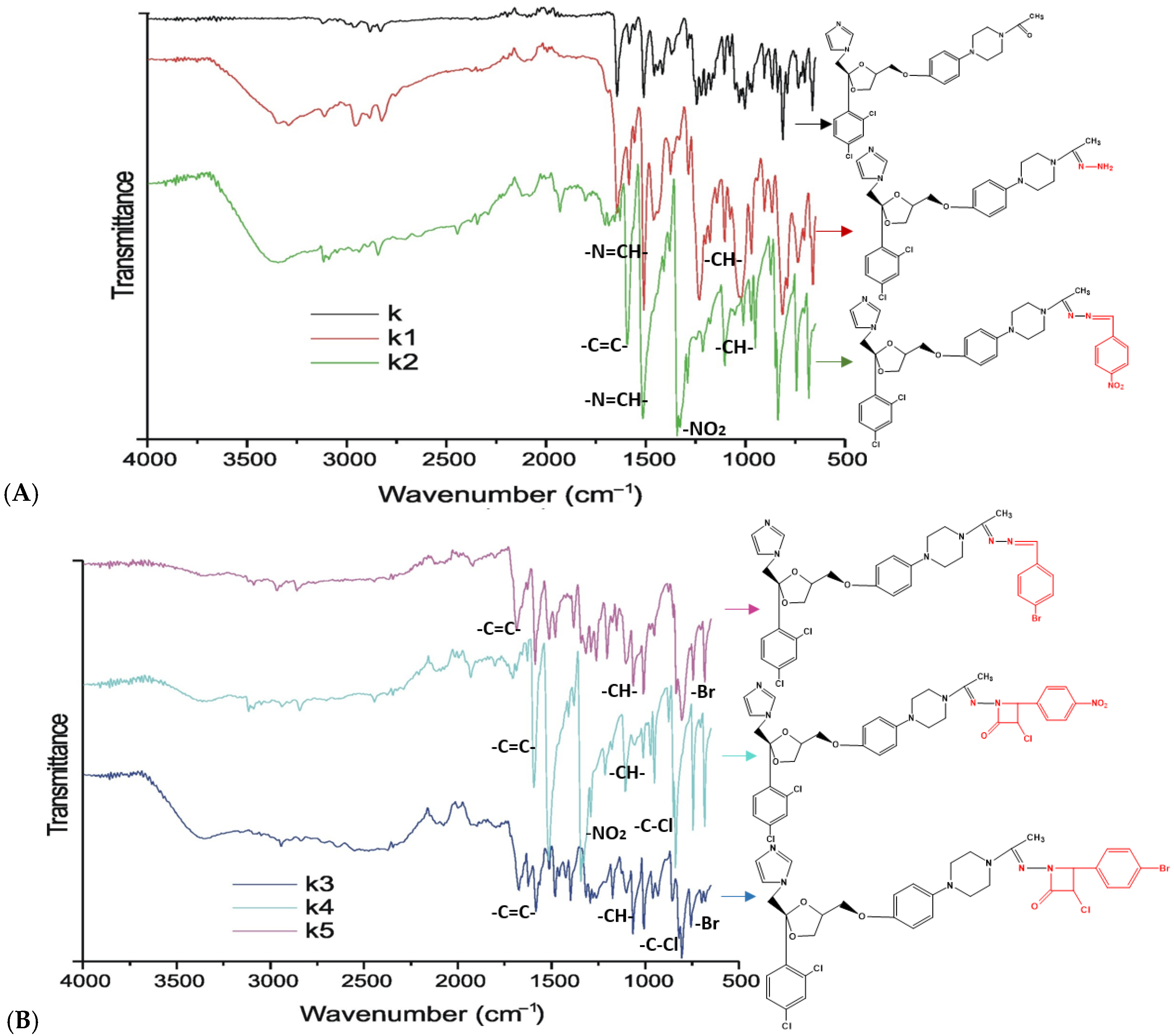

2.4. Physico-Chemical Characterization and Structural Confirmation of Derivatives with Azole Nucleus

The synthesized ketoconazole derivatives were characterized by their physicochemical properties, including melting point, reaction yield, molecular formula, and molecular weight. Melting points were determined using a Stuart SMP10 melting point apparatus (Stuart, London, UK). Structural confirmation was performed using Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy to identify characteristic functional groups [

29], while the IR spectrum represents a characteristic fingerprint of a pure compound, allowing the identification of structural features and providing insights into its purity and concentration within a mixture. FT-IR spectra were acquired using a Cary 630 spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Selangor, Malaysia) equipped with a KBr engine and operated via MicroLab software version B.05.6. Spectra were recorded in transmittance mode across the 4000–500 cm

−1 spectral range. Data acquisition involved 32 scans per sample at a resolution of 8 cm

−1, with the crystal cleaned with isopropyl alcohol prior to each measurement. Subsequent spectral processing was performed using Horizon MB software version 3.3.

2.5. Antimicrobial Activity of Derivatives with Azole Nucleus

2.5.1. Antibacterial Activity

Antibacterial susceptibility testing was initially evaluated using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method on standardized Mueller-Hinton agar, following Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and EUCAST guidelines [

30].

Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213) and

Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) were selected as representative strains for Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, respectively. The bacterial inoculum was prepared by suspending 3–5 colonies in saline solution, and turbidity was adjusted to 0.5 on the McFarland scale (equivalent to approximately 1.5 × 10

8 CFU/mL) using a nephelometer. Sterile paper discs (6 mm diameter) were impregnated with 30 µL of the test compound solutions or the positive control, Gentamicin (30 mg/mL), and placed on the inoculated agar plates. The plates were incubated under aerobic conditions at 37 °C for 24 h. The diameter of the inhibition zones was measured in millimeters (mm). All tests were performed in triplicate, and the mean values were calculated.

Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC). The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) were determined using the broth microdilution method against Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213 and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, on 96-well plates. Dispersions of 100 µg/mL of all compounds in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were added to micro-wells in a serial dilution, giving concentrations of 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.75, and 1.5 µg/mL.

A bacterial suspension containing approximately 5 × 105 colony-forming units/mL was prepared from a 24-h culture plate, and 25 µL of this inoculum was added to each well. Positive growth controls (bacteria in Mueller-Hinton broth with DMSO) and sterility controls (broth and DMSO only) were included in each assay. The microplates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h in the dark.

The MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of the compound that completely inhibited visible bacterial growth. To determine the MBC, 10 µL aliquots from wells showing no visible growth were subcultured onto agar plates and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The MBC was defined as the lowest concentration required to kill more than 99.9% of the initial bacterial inoculum. All experiments were performed in triplicate and the results represent the average of the three measurements.

2.5.2. Antifungal Activity

Disk Diffusion Assay: Ketoconazole was used as a reference agent to evaluate inhibitory activity against the tested fungal strains: Candida albicans (ATCC 10231), Candida parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) and a clinical isolate of Cryptococcus neoformans obtained from the “Sf. Cuvioasa Parascheva” Clinical Hospital for Infectious Diseases. A concentration of 2% was used for all derivatives.

Antifungal susceptibility was assessed using the disk diffusion method in accordance with CLSI guidelines [

31]. Fungal suspensions were inoculated onto the surface of Sabouraud medium dispersed in Petri dishes. Sterile paper discs (6 mm in diameter) were placed on the agar surface and impregnated with 30 µL of each test compound. A 2% ketoconazole solution served as positive control. The plates were incubated at 35 °C/±2 °C for 24 h (extended to 48 h if no growth was observed after the initial period). Following incubation, the diameters of the zone of inhibition (mm) were measured. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.6. Antioxidant Activity of Derivatives with Azole Nucleus

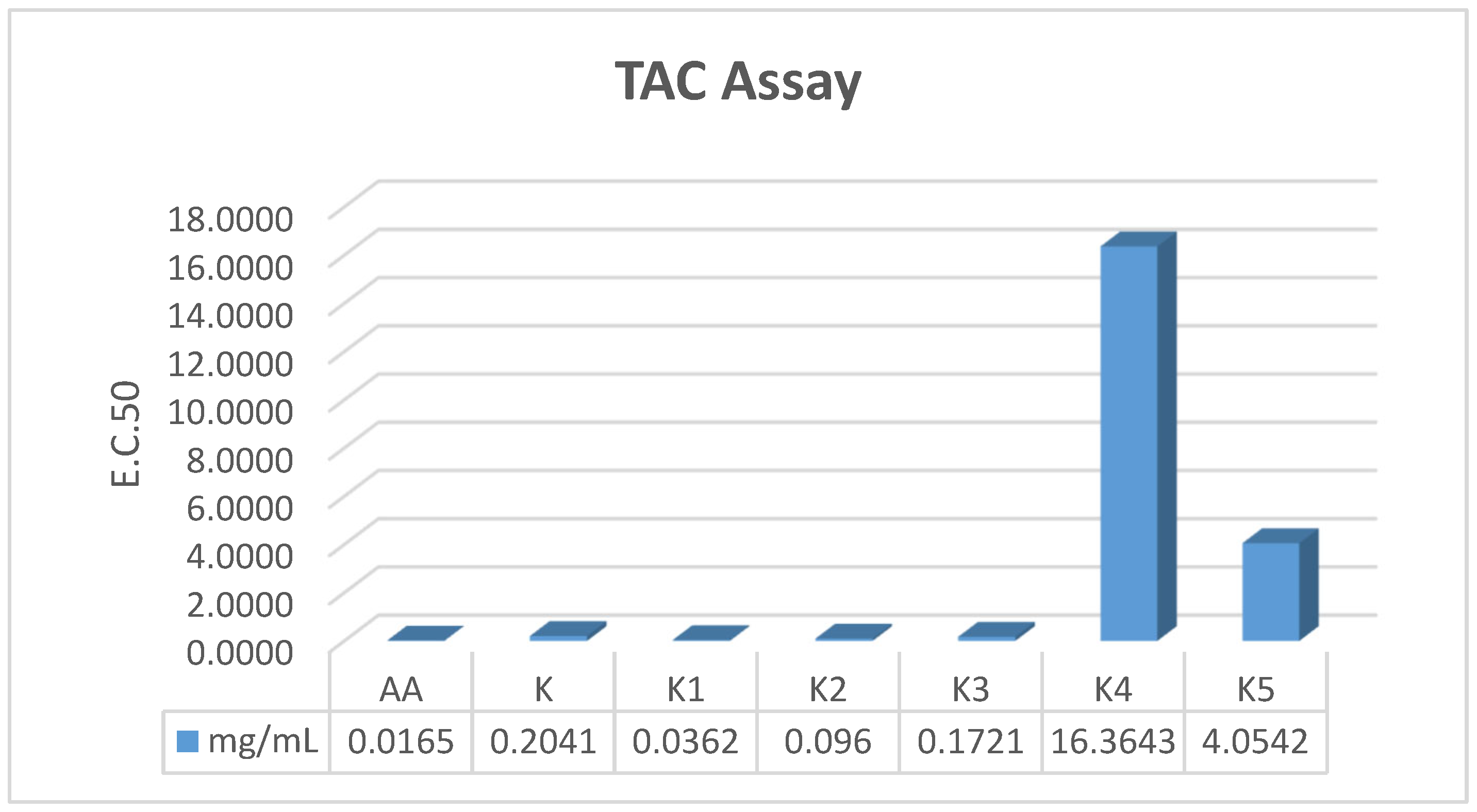

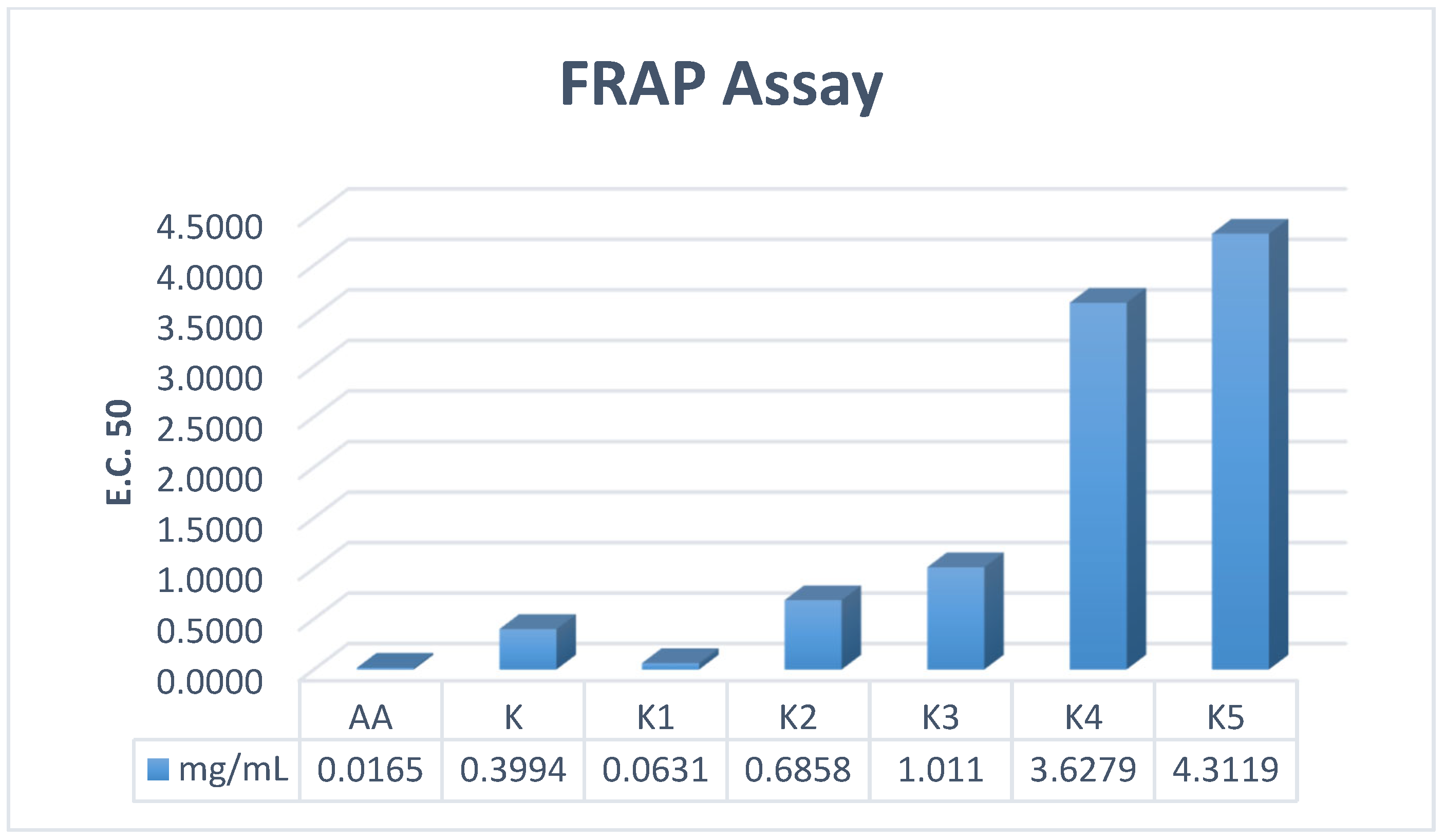

The antioxidant properties of the synthesized compounds were evaluated in vitro using spectrophotometric assays, specifically Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC), Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) and DPPH radical scavenging activity. All spectrophotometric measurements were performed using a UV-1900 spectrophotometer (Schimadzu, Columbia, MD, USA), following standard analytical protocols.

2.6.1. Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) Assay

The antioxidant capacity of the ketoconazole derivatives was determined using the phosphomolybdenum assay [

32]. Briefly, 100 μL of each sample solution (prepared from stock solutions in DMSO: 20 mg/mL for

K,

K2,

K3; 1 mg/mL for

K1; and 10 mg/mL for

K4,

K5) was mixed with 4 mL of reagent solution consisting of 0.6 M sulfuric acid, 28 mM sodium phosphate, and 4 mM ammonium molybdate. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 95 °C for 90 min and subsequently allowed to cool to room temperature. Absorbance was recorded at 695 nm using a corresponding blank consisting of 100 μL DMSO and 4 mL reagent solution. The effective concentration required to achieve 50% antioxidant activity (EC

50) was calculated for each derivative. All experiments were conducted in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

2.6.2. Ferric Reducing Power (FRAP) Assay

The ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) of the ketoconazole derivatives was assessed according to previously reported protocols with minor modifications [

33]. Briefly, 1 mL of each stock solution (20 mg/mL for

K,

K2, and

K3; 1 mg/mL for

K1; and 10 mg/mL for

K4 and

K5, prepared in DMSO) was mixed with 1 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 6.6) and 1 mL of potassium ferricyanide (1%

w/

v). The mixtures were incubated at 50 °C for 20 min, after which the reaction was terminated by the addition of 1 mL trichloroacetic acid (10%

w/

v). The samples were then centrifuged at 4500 rpm for 15 min. A 1.5 mL aliquot of the resulting supernatant was mixed with 1.5 mL deionized water, followed by the addition of 0.3 mL ferric chloride solution (0.1%

w/

v). After a 5-min reaction time, absorbance was recorded at 700 nm. A blank sample, containing all reagents except the test compound (replaced with 1 mL DMSO), was used for baseline correction. The effective concentration required to achieve 50% reducing activity (EC

50) was calculated for each derivative. All analyses were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

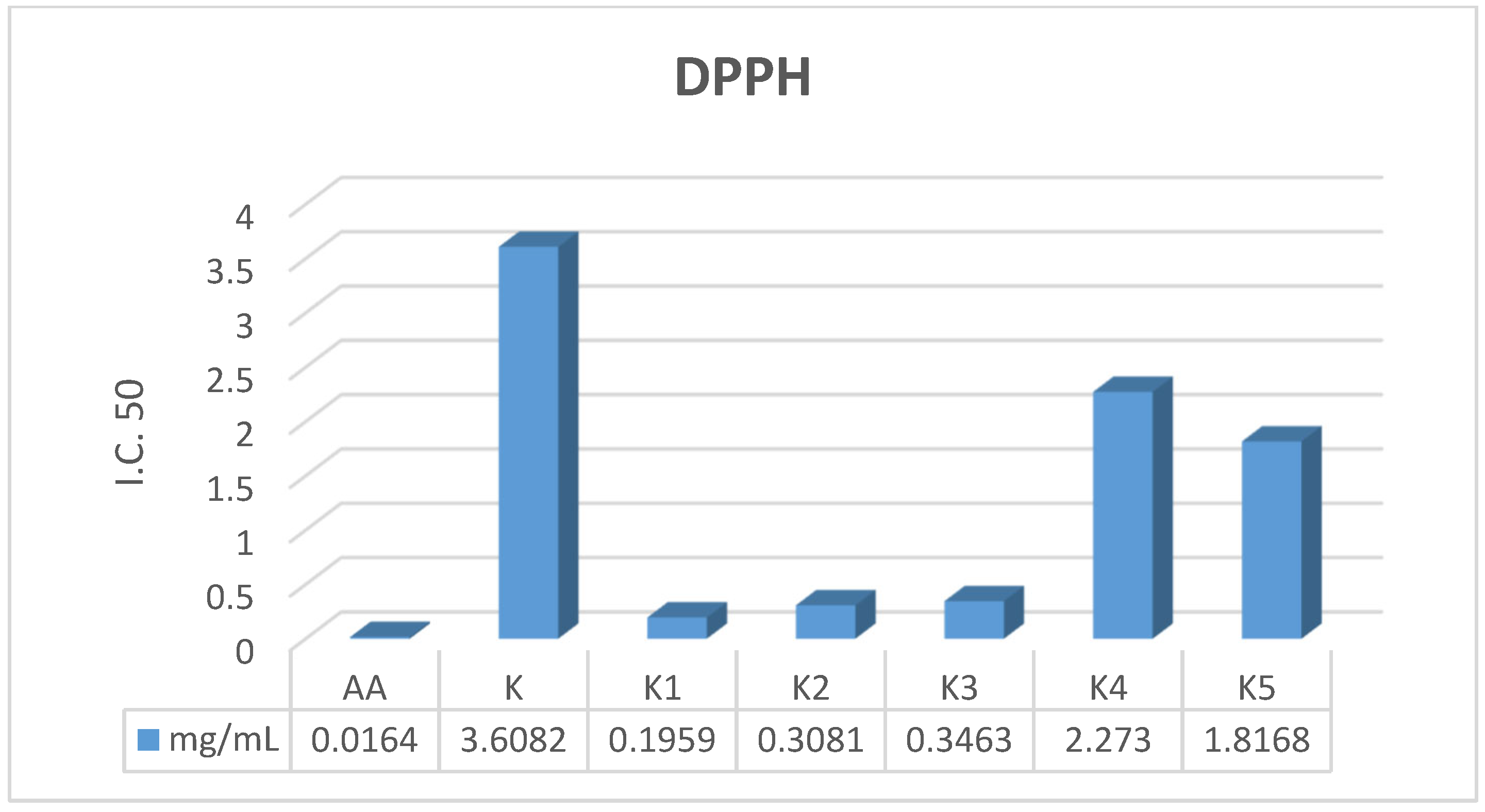

2.6.3. DPPH (1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl) Radical Scavenging Ability

The radical scavenging activity of the ketoconazole derivatives against 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical was assessed according to established methods with minor modifications [

34]. Briefly, 100 μL of each stock solution (20 mg/mL for

K,

K2, and

K3; 1 mg/mL for

K1; and 10 mg/mL for

K4 and

K5, prepared in DMSO) was mixed with 2900 μL of DPPH solution (0.1 mM in methanol). The reaction mixture was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. Subsequently, the absorbance was measured at 517 nm. A methanolic DPPH solution without sample served as the control. The percentage of radical scavenging activity (I%) was calculated using Equation (4):

where Ac and As are the absorbance of the control and sample, respectively. Inhibitory concentration (IC

50) for each derivative was calculated. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

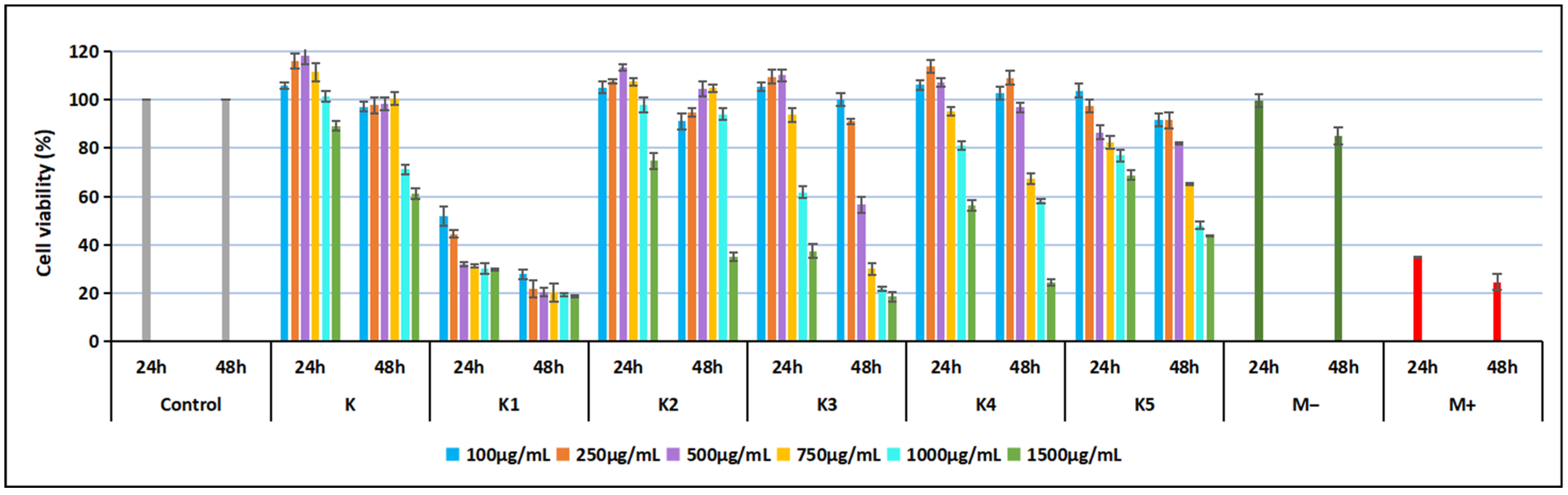

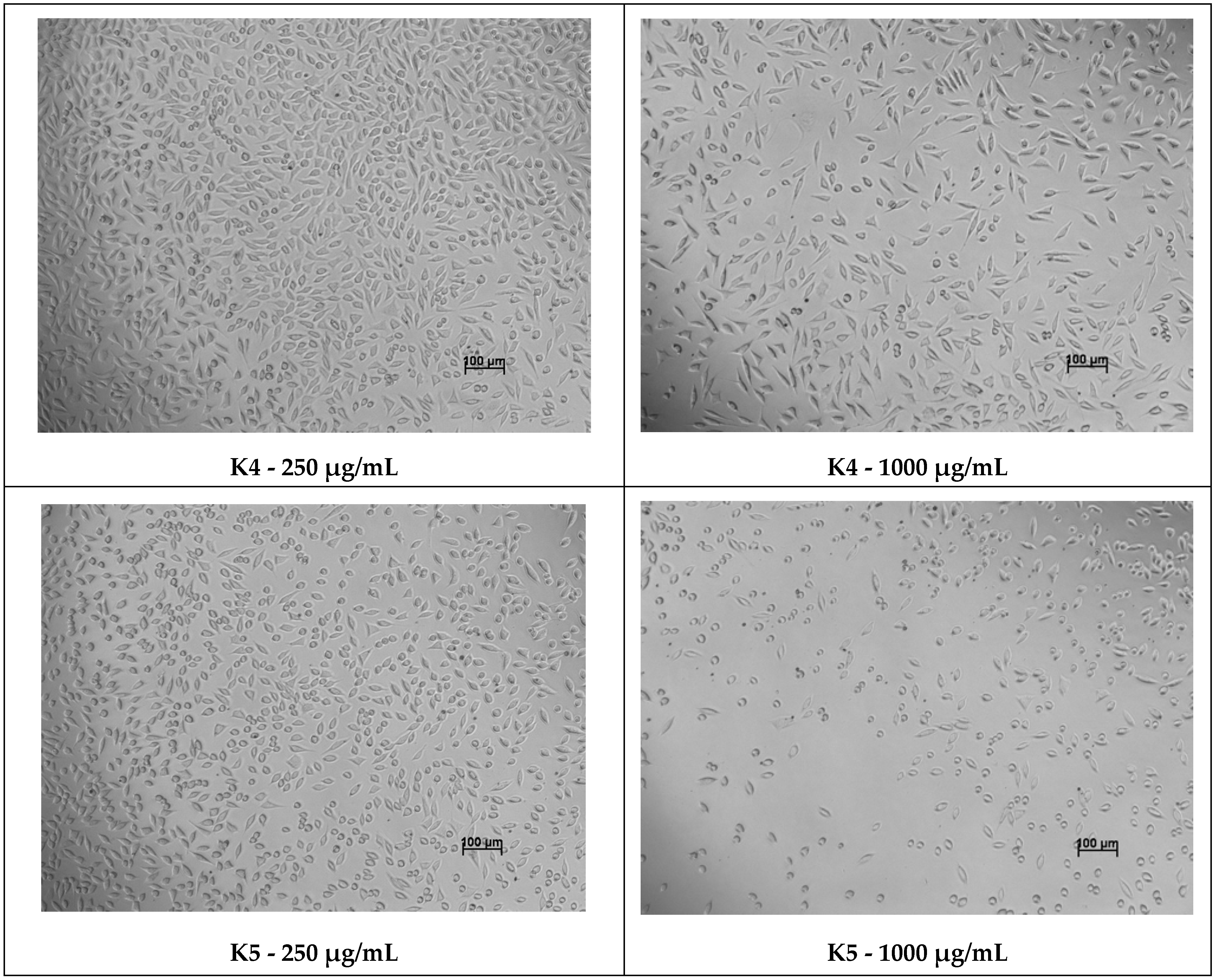

2.7. Cytotoxicity Evaluation on Normal NCTC Fibroblasts Using MTT Method

The cytotoxicity of the ketoconazole derivatives (

K,

K1,

K2,

K3,

K4, and

K5) was in vitro evaluated using the MTT assay on a stabilized line of normal mouse fibroblasts (NCTC, L929). Cells were seeded at a density of 40,000 cells/mL in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) supplemented with 1% PSN antibiotic mixture (penicillin, streptomycin, neomycin) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Sample stock solutions were prepared by dissolving each compound in a minimal volume of DMSO, followed by dilution in culture medium to obtain a final stock concentration of 1500 μg/mL. From these stocks, working concentrations of 100, 250, 500, 750, 1000, and 1500 μg/mL were prepared for testing. Cytotoxicity was assessed using the extract method, with exposure times of 24 and 48 h, and morphological evaluation of fibroblasts was performed at 48 h. Appropriate controls were included in all experiments: a culture control (Mc, untreated cells), a negative control (M

−, extract of high-density polyethylene granules at 0.2 g/mL in culture medium), and a positive control (M

+, 0.3% phenol solution in culture medium). Following incubation, MTT reagent was applied, and cell viability was quantified spectrophotometrically, enabling comparative assessment of the cytotoxic effects of each compound across the tested concentration range [

35].

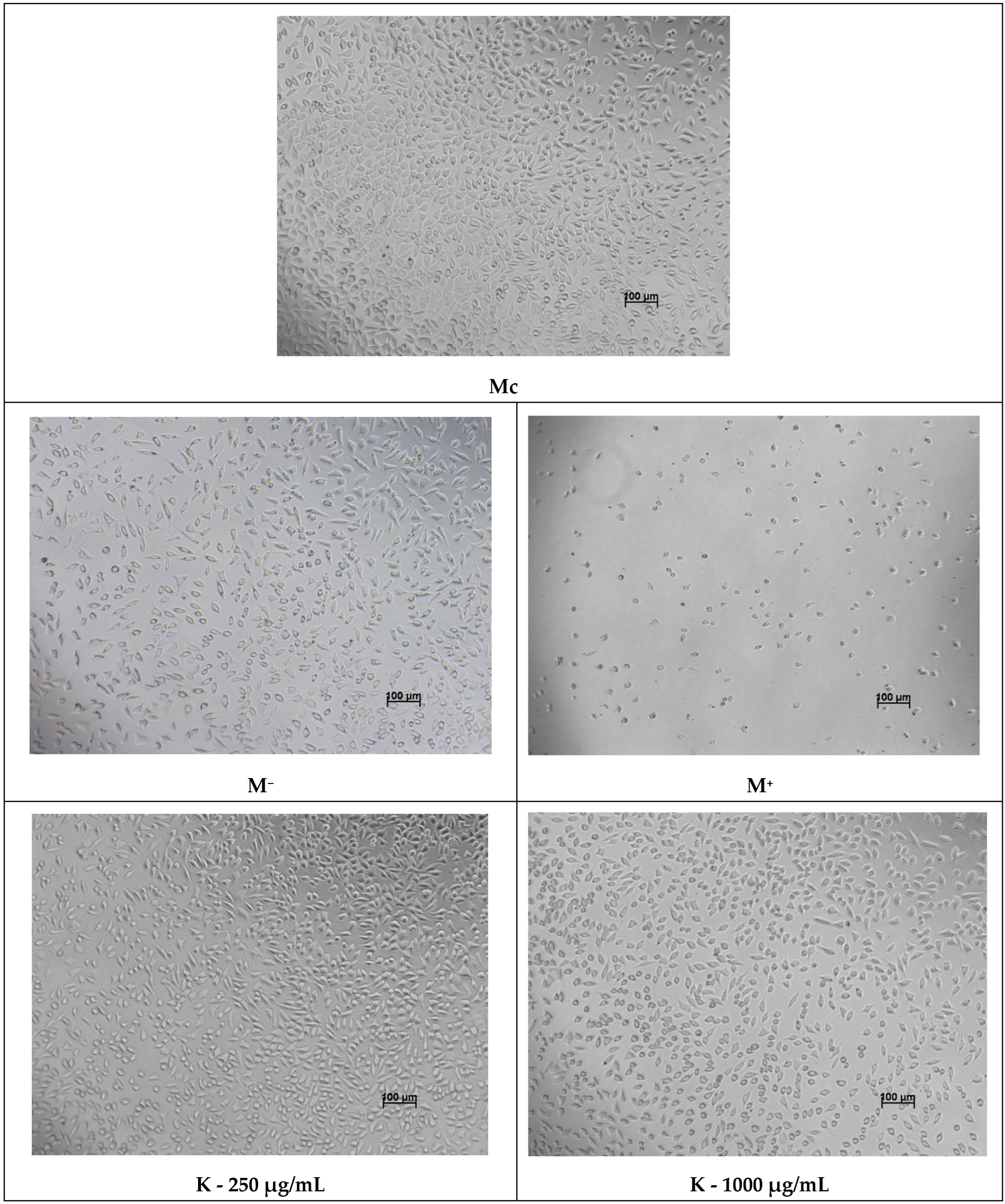

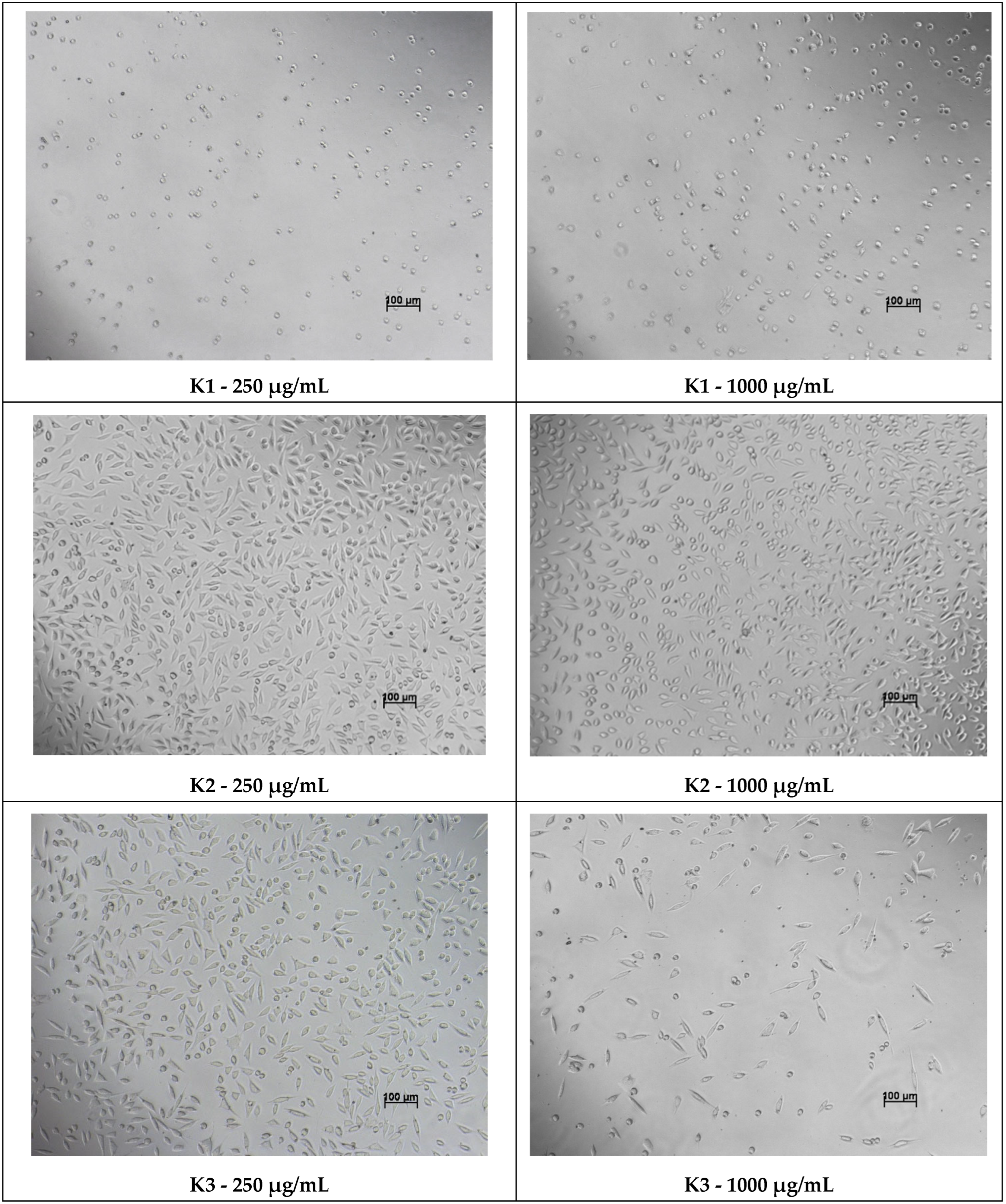

The cytotoxicity of the tested ketoconazole derivatives was assessed using an indirect contact method on a stabilized mouse fibroblast cell line, NCTC clone L929. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the European standard SR EN ISO 10993-5:2009 [

36], which outlines procedures for in vitro evaluation of cytotoxic effects [

37]. Cell viability in the presence of the azole compounds was quantified using the MTT spectrophotometric assay after 24 and 48 h of exposure, while cellular morphology was examined after 48 h to identify potential structural alterations induced by the samples.

The MTT assay (thiazolyl-blue-tetrazolium-bromide) is based on the reduction of tetrazolium salt by mitochondrial dehydrogenases present in metabolically active cells, resulting in the formation of insoluble blue–violet formazan crystals. Following solubilization with isopropanol, resulting colored solution allows quantitative measurement of viable cells by spectrophotometric absorbance at 570 nm [

38]. The percentage of viable cells was calculated using the following formula:

For the experiments, confluent fibroblast cultures were trypsinized and seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 40,000 cells/mL (100 μL/well), with three replicates for each test condition. The plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 to allow cell adherence and stabilization. Stock solutions of the compounds (1500 μg/mL) were prepared by dissolving the samples in a minimal amount of DMSO, followed by dilution in MEM supplemented with PSN and 10% fetal bovine serum. Control solutions were also prepared: a positive control consisting of 0.3% phenol in culture medium, and a negative control represented by an extract of high-density polyethylene (HDPE) granules at 0.2 g/mL. All sample and control solutions were extracted for 24 h at 37 °C and subsequently sterilized through 0.22 µm Millipore filters (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

After the cells reached the subconfluently phase (24 h post-seeding), the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium for the culture control wells, while the wells designated for testing received the appropriate sample concentrations or control solutions. The plates were then incubated for an additional 24 h under standard culture conditions. At the 24-h time point, cytotoxicity was evaluated by replacing the treatment solutions with MTT reagent (50 μg/mL) and incubating for 3 h. The resulting formazan crystals were solubilized with isopropanol under orbital shaking for 15 min. Absorbance was recorded at 570 nm using a Spectro Star BMG Labtech spectrophotometer (Ortenberg, Germany), and viability percentages were calculated relative to the untreated culture control.

The 48-h viability assessment was performed following the same procedure. Additionally, microscopic examination of cellular morphology was conducted at the 48-h interval to qualitatively evaluate structural changes associated with potential cytotoxic effects of the compounds.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All assays were carried out in triplicate. Data were analyzed by an analysis of variance (ANOVA) (

p < 0.05) and were expressed as means ± SD. The total antioxidant activity, expressed as EC

50 values, was calculated using the linear equations, resulting from plotting the calibration curves, available in the

Supplementary Materials of this article.

4. Discussion

In medicinal chemistry, azole heterocycles are widely recognized as critical pharmacophores due to their proven ability to potentiate antimicrobial and antifungal efficacy. Imidazole and triazole moieties exert their biological effects by coordinating with heme-containing enzymes, thereby disrupting membrane sterol biosynthesis and forming stable complexes with essential microbial targets [

40]. Specifically, their high affinity for cytochrome P450-dependent 14α-demethylase (CYP51) renders them highly potent antifungal agents [

41]. Furthermore, the structural versatility of the azole scaffold facilitates the design of derivatives with expanded pharmacological profiles, including antibacterial, antiviral, and antiparasitic activities [

42,

43]. Consequently, the successful clinical integration of numerous azole-based drugs underscores the enduring importance of this moiety in the discovery of novel antimicrobial therapeutics.

While ketoconazole is a well-established antifungal agent that targets the CYP51 enzyme to disrupt sterol biosynthesis, its application is increasingly limited by drug resistance, toxicity, and a narrowing spectrum of activity [

8]. To overcome these drawbacks, medicinal chemistry efforts have focused on optimizing the ketoconazole scaffold to improve efficacy and safety. Recent literature confirms that targeted chemical modifications can yield derivatives with superior potency and pharmacokinetic properties [

44]. For instance, Renzi et al. demonstrated that optimizing specific substituents significantly improved efficacy against

Malassezia species [

44], while Biernasiuk et al. reported derivatives characterized by favorable lipophilicity and enhanced antimicrobial profiles [

45]. Moreover, the synthesis of hybrid molecules combining ketoconazole with other pharmacophores has proven effective in broadening the antimicrobial spectrum and bypassing resistance mechanisms [

46].

Motivated by these precedents, this study investigates the synthesis and biological evaluation of a novel series of ketoconazole derivatives (K1–K5) designed to address these clinical challenges. The primary objective was to chemically modify the ketoconazole scaffold to expand its pharmacological profile beyond traditional antifungal applications. The synthesis provided the target compounds in good yields, ranging from 69.13% to 89.3%, with melting points indicating high purity. The formation of Schiff base intermediates (K1, K2, K3) proceeded with consistent yields (~69–74%), demonstrating the stability of the azomethine linkage formation. Interestingly, the cyclization to azetidinone derivatives revealed a dependency on the substituent. Compound K4 (containing a nitro-substituted ring) was obtained with the highest yield of 89.3%. In contrast, the bromo-substituted derivatives K3 and K5 were isolated in slightly lower yields (69.13% and 74.1%), respectively. This variance is likely attributable to the steric hindrance exerted by the bulkier bromide atom which slightly impedes the cycloaddition process required to form the strained β-lactam ring.

Regarding thermal properties, all synthesized derivatives exhibited higher melting points than the parent Ketoconazole (148–150 °C), confirming the increased molecular rigidity of the modified scaffolds. A notable trend was observed among the azetidinones: the brominated derivatives K3 (225–227 °C) and K5 (202–203 °C) displayed significantly higher melting points compared to the nitro analog K4 (160–162 °C) and the Schiff base precursors. This enhancement is consistent with the presence of the heavy halogen (bromine), which increases molecular weight and polarizability, thereby strengthening intermolecular dispersion forces within the crystal lattice.

The successful synthesis of Schiff base (

K1–

K3) and azetidinone (

K4,

K5) derivatives was confirmed via FTIR spectroscopy, which provided definitive evidence of functional group interconversion. The formation of the Schiff base derivatives was corroborated by the emergence of the characteristic azomethine (-C=N-) stretching vibration, a diagnostic band absent in the parent precursor. This observation is consistent with previous reports describing hydrazone formation from imidazole-containing ketone precursors, where the formation of the -C=N- bond represents the primary spectral marker of successful condensation [

47]. Furthermore, the presence of bromine in compounds

K3 and

K5 was substantiated by low-frequency vibrations in the 600–650 cm

−1 region, consistent with the reduced mass effect of heavy halogen atoms described in foundational vibrational spectroscopy literature.

The synthetic pathway of compounds K1–K5 was also designed to adhere to Green Chemistry principles. The protocol utilized ethanol and dioxane, solvents with relatively lower toxicity profiles and relied on precipitation for product isolation. This approach significantly improved the process mass intensity (PMI) by avoiding the large volumes of eluent typically required for silica gel chromatography. Furthermore, the high yields obtained (up to 89.3% for K4) indicate a high atom economy, while the use of moderate reflux temperatures ensures energy efficiency, making the method suitable for potential scale-up applications.

The evaluation of Green Chemistry metrics highlights the balance between the molecular complexity of the synthesized derivatives and the environmental footprint of the protocol. A remarkable feature of this synthetic pathway is the consistently high Atom Economy (AE) observed across all compounds, ranging from 94% to 98%. For the Schiff base series (K1–K3), the AE values approached the theoretical maximum, confirming that the condensation mechanism is inherently atom-efficient. Notably, the β-lactam derivatives (K4 and K5) also maintained high AE values (>95%), despite the elimination of hydrochloric acid during the cycloaddition process. This suggests that the substantial molecular weight of the target azetidinone scaffold dominates the mass balance, rendering the loss of the small HCl molecule negligible in terms of atomic efficiency.

While Atom Economy reflects theoretical potential, the Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) provides a more realistic assessment of process performance by accounting for isolated yields and stoichiometric excesses. Among the synthesized derivatives, compound K4 exhibited the highest efficiency, with an RME of 79%, closely mirroring its isolated yield of 89.3%. This narrow disparity between yield and RME indicates that the synthesis of the nitro-substituted β-lactam required minimal reagent excess and resulted in low material loss during purification. In contrast, the brominated derivatives K3 and K5 displayed lower RME values (54% and 66%, respectively), a decrease that correlates with their moderate yields. This trend suggests that the steric hindrance introduced by the bulky bromine atoms may have impeded the reaction completeness or necessitated more intensive purification steps, thereby lowering the overall mass transfer efficiency compared to the nitro-analogues.

The environmental impact was further quantified using the E-Factor metric, which revealed significant variations based on structural complexity. Compound

K1 exhibited a low E-Factor of 5, a value typically associated with bulk chemical production rather than pharmaceutical synthesis, indicating a highly efficient isolation process with minimal solvent waste. As expected, a transition from the Schiff bases (

K2,

K3: E-Factors ~45) to the β-lactam derivatives (

K4,

K5: E-Factors ~63–76) resulted in an increased waste footprint. This elevation is scientifically justified by the requirements of the cyclization step, which involves additional reagents (chloroacetyl chloride, triethylamine) and generates stoichiometric salt by-products. However, it is crucial to note that all calculated E-Factors fall well within, or significantly below, the typical range of 25–100 defined by Sheldon for fine chemical and pharmaceutical synthesis [

25]. Even the highest value obtained (

K5, E-Factor 76) demonstrates that the optimized protocol remains sustainable and competitive with established industrial standards for early-stage drug discovery.

The antimicrobial evaluation highlights how structural modifications to the imidazole scaffold can significantly modulate both antibacterial and antifungal effectiveness. In the Kirby–Bauer assay, the derivatives displayed variable diffusion and activity patterns, with

K1,

K4, and

K5 consistently outperforming the parent compound against several microorganisms. The increased inhibition zones observed for

K1 against

Staphylococcus aureus (25 mm) and fungal strains such as

Candida albicans (28 mm) and

Cryptococcus neoformans (49.3 mm) suggest that its specific structural modification may enhance membrane permeability or improve interaction with fungal CYP51, a known ketoconazole target [

41]. These observations align with similar enhancement trends for other modified imidazole, triazole or tetrazole derivatives, where small substitutions increased lipophilicity and resulted in stronger antifungal profiles [

48,

49]. For instance, Gupta et al. (2015) [

50] synthesized a series of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives that, similar to

K1, exhibited strong antibacterial activity against

Staphylococcus aureus, in some cases proving superior to the standard streptomycin.

The antifungal results obtained in this study were particularly robust, consistent with the established mechanism of azole derivatives, which involves the inhibition of lanosterol 14-α-demethylase in fungal cells. Compounds

K1,

K4, and

K5 exhibited inhibition zones comparable to or surpassing standard ketoconazole, especially against

Candida parapsilosis and

Cryptococcus neoformans. These findings corroborate previous reports showing that structural modifications to the azole ring or its substituents can broaden the antifungal spectrum and potentially circumvent certain resistance mechanisms [

51].

While broad-spectrum activity is often prioritized for polymicrobial wounds, the selective profile exhibited by compounds K2 and K3 offers a distinct therapeutic advantage. These derivatives demonstrated potent antifungal activity against Cryptococcus neoformans and Candida parapsilosis but showed no inhibitory effect against bacterial strains.

This selectivity suggests that K2 and K3 could serve as microbiome-sparing antifungal agents. In clinical dermatology, the preservation of commensal skin flora (such as non-pathogenic staphylococci) is crucial for maintaining skin immunity and preventing secondary colonization by opportunistic pathogens. Unlike broad-spectrum agents that often induce cutaneous dysbiosis, these derivatives target the fungal infection specifically without disrupting the beneficial bacterial ecosystem. Consequently, K2 and K3 represent promising candidates for the treatment of specific fungal dermatomycoses where minimizing collateral damage to the host microbiome is a priority.

A notable observation is that while the synthesized derivatives exhibited superior activity against Gram-positive strains, the parent Ketoconazole demonstrated higher efficacy against the Gram-negative bacterium

Escherichia coli. This discrepancy can be rationalized by considering the distinct structural architecture of the Gram-negative outer membrane, which functions as a selective molecular sieve. The passage of antimicrobial agents across this barrier is largely restricted to hydrophilic molecules with low molecular weight (<600 Da) that can diffuse through porin channels. As shown in

Table 1, the chemical modification of the ketoconazole scaffold significantly increased the molecular weight from 531.43 g/mol (Parent

K) to values ranging between 685.57 and 788.94 g/mol for the derivatives

K2–

K5. This substantial increase in molecular size and steric bulk likely hinders the passage of the new derivatives through the narrow porin channels of

E. coli. Furthermore, the increased lipophilicity associated with the addition of aromatic rings and halogen atoms (-Br, -Cl) may further impede transport across the hydrophilic periplasmic space, rendering the derivatives less effective against Gram-negative pathogens compared to the smaller, parent molecule.

Given that chronic wounds are characterized by a persistent inflammatory state driven by excessive Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) [

52], the introduction of antioxidant capability into the antimicrobial scaffold provides a synergistic therapeutic benefit. Compound

K1 demonstrated superior antioxidant activity across all three mechanistic assays, significantly outperforming the parent drug: Radical Scavenging (DPPH): IC

50 = 0.1959 mg/mL (18-fold improvement over parent

K), Electron Donation (FRAP): EC

50 = 0.0631 mg/mL (6-fold improvement over parent

K), Total Capacity (TAC): EC

50 = 0.0362 mg/mL (comparable to the standard Ascorbic Acid). These data suggest that the Schiff base modification in

K1 facilitates both Electron Transfer (ET) and Hydrogen Atom Transfer (HAT) mechanisms, effectively neutralizing free radicals. This dual-action is critical for wound healing, where controlling oxidative stress is as vital as preventing infection.

In contrast, while the Schiff base derivative K1 exhibited potent antioxidant activity, the cyclized β-lactam analogues (K4 and K5) showed a marked reduction in scavenging capacity. This decline can be attributed to the disruption of the conjugated π-electron system. The conversion of the azomethine double bond (-N=CH-) into the saturated azetidinone ring interrupts the electronic communication between the aromatic systems, thereby diminishing the molecule’s ability to stabilize the resulting radical species through resonance after electron or hydrogen donation. Furthermore, the introduction of the rigid four-membered ring, particularly when substituted with bulky halogens, creates significant steric hindrance. This steric shielding likely obstructs the access to the active redox sites of the molecule, reducing the efficiency of the electron transfer process compared to the more planar and accessible Schiff base precursors.

It is noteworthy that while K2 and K3 lacked antibacterial activity, they proved to be potent antioxidants. This suggests their potential utility in non-infected but inflamed tissues, or in specific fungal infections where oxidative damage is a primary pathology. Conversely, the beta-lactam derivatives K4 and K5 showed significantly reduced antioxidant capacity, indicating that the rigid cyclization may sterically hinder the radical scavenging active sites.

The findings of this study demonstrate that chemical modification of ketoconazole through hydrazone formation and subsequent chloroacetylation produced derivatives with significantly improved antioxidant profiles and acceptable biocompatibility at moderate concentrations, suggesting their suitability as candidates for wound-healing applications. The enhanced antioxidant capacity observed particularly in compounds

K2 and

K3 aligns with previous reports showing that hydrazone scaffolds often possess superior redox behavior due to resonance stabilization and electron delocalization along the -C=N- linkage, which facilitates proton or electron donation depending on the assay conditions [

53]. Substituent effects also appear to play a critical role: electron-withdrawing groups such as nitro or bromo, present in our aromatic aldehydes, are known to modulate radical-quenching efficiency by altering electron density and stabilizing intermediate radicals, a trend similarly described in the antioxidant evaluation of structurally related hydrazones [

54,

55].

Interestingly, certain derivatives, particularly

K and

K2, not only exhibited minimal cytotoxicity but also stimulated fibroblast proliferation at low–moderate concentrations, an effect that parallels the behavior of some azole derivatives previously reported to possess pro-regenerative or anti-inflammatory properties [

56]. This biphasic dose–response characterized by stimulation at low doses and inhibition at high doses aligns with the toxicological concept of hormesis described by Calabrese et al. [

57]. While classical azoles are primarily known for their inhibitory action on ergosterol synthesis, our data suggest that at sub-cytotoxic concentrations, these derivatives may induce a mild cellular stress response. According to general hormetic principles, such mild stress can trigger compensatory survival mechanisms and metabolic upregulation in fibroblasts [

58]. This pro-proliferative profile of

K2 at low concentrations is a notable finding, suggesting potential utility in supporting the granulation phase of wound repair by avoiding the net suppression of tissue regeneration often seen with purely cytotoxic antiseptics.

In contrast, a critical assessment of Compound

K1 reveals a significant trade-off between its superior antimicrobial potency and its biocompatibility profile. The data indicates that at bactericidal concentrations,

K1 also exerts toxic effects on host cells, which limits its suitability for direct application on granulating tissue. To overcome this, future development should prioritize advanced formulation strategies. By encapsulating

K1 in controlled-release vehicles such as liposomes or hydrogel matrices, it may be possible to modulate its release rate, maintaining antimicrobial efficacy while shielding host cells from cytotoxic spikes. Alternatively, the compound’s utility may be restricted to the initial debridement phase of infected wounds, where aggressive reduction in the microbial load takes precedence over tissue regeneration. The overall biocompatibility of the most promising derivatives aligns well with studies demonstrating that ketoconazole-based molecules or imidazole derivatives can achieve favorable safety profiles when appropriately modified or formulated [

59,

60]. Importantly, the combination of antioxidant activity and fibroblast compatibility represents a desirable dual action highly relevant to wound-healing environments characterized by oxidative stress and impaired cellular proliferation.

Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Summary. To rationalize the observed biological profiles, a structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis was conducted to interpret the specific contributions of the chosen pharmacophores. The robust antioxidant activity observed for the Schiff base derivatives (K1, K2, K3) can be directly attributed to the presence of the azomethine double bond (-N=CH-). This conjugated system facilitates the resonance stabilization of free radicals, acting as the critical structural determinant for scavenging efficiency. Consequently, the cyclization of this bond into the saturated azetidinone ring in derivatives K4–K5 disrupted the electronic conjugation, leading to the observed reduction in antioxidant capacity. Conversely, the introduction of the β-lactam ring was strategically aimed at broadening the antimicrobial spectrum. Our data suggests that this cyclic amide, particularly when substituted with halogen atoms, enhances the intrinsic antibacterial potential relative to the parent drug by increasing the scaffold’s lipophilicity and affinity for microbial membranes. Specifically, the presence of nitro (K2, K4) and bromine (K3, K5) substituents appears to drive the activity against Gram-positive pathogens, although the increased steric bulk associated with the heavier halogens imposes permeability constraints against Gram-negative strains, highlighting a delicate balance between lipophilicity and molecular size.

Limitations and Future Perspectives. Despite the promising dual-action profile of the synthesized derivatives, this study has limitations inherent to in vitro screening. While the biological assays demonstrated potent antimicrobial and antioxidant activities, these simplified models do not fully replicate the complex pathophysiology of chronic wounds, which involves dynamic interactions between the host immune system, vascular supply, and polymicrobial biofilms. Additionally, the low aqueous solubility of the halogenated derivatives (particularly K3 and K5) and the cytotoxicity observed for K1 pose challenges for direct topical application.

Future work will focus on overcoming these physicochemical and safety barriers through formulation development. We aim to incorporate the lead compounds into advanced wound dressings, such as electrospun nanofibers or biocompatible hydrogels, to achieve controlled drug release and mitigate local toxicity [

61,

62,

63,

64]. Furthermore, the therapeutic efficacy and safety of these optimized formulations will be validated using ex vivo human skin explants and relevant in vivo wound healing models to assess re-epithelialization rates and systemic safety prior to clinical translation.