Abstract

The increasing impact of global warming is predominantly driven by the extensive use of fossil fuels, which release significant amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. This has led to a critical need for alternative, sustainable energy sources that can mitigate environmental impacts. Photovoltaic technology has emerged as a promising solution by harnessing renewable energy from the sun, providing a clean and inexhaustible power source. Perovskite solar cells (PSCs) are a class of hybrid organic–inorganic solar cells that have recently attracted significant scientific attention due to their low cost, relatively high efficiency, low–temperature processing routes, and longer carrier lifetimes. These characteristics make them a viable alternative to traditional fossil fuels, reducing the carbon footprint and contributing to the fight against global warming. In this study, the SCAPS–1D numerical simulator was used in the computational analysis of a PSC device with the configuration FTO/ETL/BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3/HTL/Ir. Different hole transport layer (HTL) and electron transport layer (ETL) material were proposed and tested. The HTL materials included copper (I) oxide (Cu2O), 2,2′,7,7′–Tetrakis(N,N–di–p–methoxyphenylamine)9,9′–spirobifluorene (spiro–OMETAD), and poly(3–hexylthiophene) (P3HT), while the ETLs included cadmium suphide (CdS), zinc oxide (ZnO), and [6,6]–phenyl–C61–butyric acid methyl ester (PCBM). Finally, BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 was proposed as an absorber, and a fluorine–doped tin oxide glass substrate (FTO) was proposed as an anode. The metal back contact used was iridium. Photovoltaic parameters such as short circuit density (Isc), open circuit voltage (Voc), fill factor (FF), and power conversion efficiency (PCE) were used to evaluate the performance of the device. The initial simulated primary device with the configuration FTO/CdS/BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3/spiro–OMETAD/Ir gave a PCE of 5.75%. Upon testing different HTL materials, the best HTL was found to be Cu2O, and the PCE improved to 9.91%. Thereafter, different ETLs were also inserted and tested, and the best ETL was established to be ZnO, with a PCE of 10.10%. Ultimately an optimized device with a configuration of FTO/ZnO/BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3/Cu2O/Ir was achieved. The other photovoltaic parameters for the optimized device were as follows: FF = 31.93%, Jsc = 14.51 mA cm−2, and Voc = 2.18 V. The results of this study will promote the use of environmentally benign BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3–based absorber materials in PSCs for improved performance and commercialization.

1. Introduction

The global energy demand has surged in recent decades, driven by population growth and technological advancements. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global energy consumption is expected to increase by 50% by 2050, highlighting the pressing need for sustainable and efficient energy sources [1,2,3]. Solar energy, a pivotal player in the renewable energy sector, has gained significant attention due to its abundant availability and potential to reduce carbon emissions [4]. Among the various types of solar cells, perovskite solar cells (PSCs) have emerged as a highly promising technology due to their remarkable power conversion efficiencies (PCEs) and low fabrication costs [5]. The continuous optimization of materials and device structures in PSCs is crucial to achieving commercially viable solutions that can contribute to global energy needs [6].

The simulation and optimization of perovskite solar cells using advanced materials and techniques have become an active area of research. One such innovative approach involves the use of BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 as a novel absorber material in PSCs [7]. This material is of particular interest due to its unique electronic properties, which are hypothesized to enhance the efficiency and stability of solar cells [8]. Simulation tools like SCAPS–1D provide a powerful platform for understanding the behavior of these materials within the device architecture and predicting their performance under various conditions [9]. Several studies have explored the use of alternative materials in PSCs to enhance their performance. For instance, recent research has investigated the incorporation of mixed–halide perovskites, which have shown improved stability and tunable bandgaps [10,11]. Another study explored the use of two–dimensional materials like graphene as an ETL, demonstrating enhanced charge transport and device stability. A third example is the use of hybrid organic–inorganic perovskites, which have achieved high PCEs while maintaining low production costs [12]. These studies underline the potential for novel materials to push the boundaries of solar cell efficiency, aligning with the goals of the current research.

Chalcogenide perovskites recently emerged as a promising, lead–free class of photovoltaic absorbers because they combine favorable optoelectronic properties with improved thermal and moisture stability compared with many halide perovskites [13,14,15]. In particular, BaZr(S,Se)3 alloys facilitate continuous tuning of the optical band gap and absorption edge between the BaZrS3 and BaZrSe3 end members, enabling targeted adjustment of visible–light absorption for single–junction and tandem applications [16]. Recent experimental work has advanced thin–film synthesis routes for BaZrS3 and related alloys, demonstrating that anion exchange and controlled sulfurization/selenization can produce mixed–anion films with bandgaps in the ~1.5–1.9 eV range [7,17], while careful process control mitigates secondary phases and defect formation. These developments motivate the present simulation study of BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 as an absorber candidate, since S–Se alloying offers a practical means of tailoring absorption and electronic structure while retaining the chemical robustness desirable for device stability.

Although several recent studies have examined BaZrS3 and BaZrSe3 individually, there is still rare comprehensive device–level investigation of mixed–anion BaZr(S,Se)3 absorbers particularly the BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 composition evaluated across multiple ETL and HTL configurations within a unified SCAPS–1D framework. Most existing simulations consider only a single device architecture, leaving the combined effects of anion alloying, transport–layer selection, and back–contact choice largely unaddressed. The present work fills this gap by performing the first systematic comparative optimization of BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 PSCs, identifying how ETL/HTL pairing, absorber thickness, and interface properties collectively influence device performance. This establishes a quantitative baseline for BaZr(S,Se)3 absorbers and provides guidance for future experimental development of chalcogenide–based perovskite solar cells.

Despite these advancements, there are still challenges to be addressed in the development of PSCs. One significant issue is the long–term stability of these devices, as they are prone to degradation under environmental conditions such as humidity and temperature fluctuations [18]. Additionally, the optimization of material interfaces within the solar cell structure remains critical, as non–ideal interfaces can lead to significant energy losses [19]. The current study aims to address these challenges by systematically exploring different combinations of ETLs and HTLs with the BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 absorber, thereby identifying the most effective configuration for maximizing device performance [20].

The focus of this study is on the development and optimization of perovskite solar cells incorporating BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 as the absorber layer. The device architecture under investigation includes various electron transport layers (ETLs) such as CdS, PCBM, and ZnO [21], as well as hole transport layers (HTLs) including Spiro–OMeTAD, P3HT, and Cu2O [22]. Additionally, fluorine–doped tin oxide (FTO) is employed as the transparent conducting oxide (TCO), with iridium (Ir) serving as the back contact due to its high work function of 5.25 eV, which is expected to improve hole extraction. Followed by a comprehensive analysis of key performance metrics such as open–circuit voltage (Voc), short–circuit current density (Jsc), fill factor (FF), and overall PCE [23]. The choice of these materials is driven by their respective electronic properties, which are anticipated to contribute to the overall efficiency and stability of the solar cells [20]. By comparing these metrics across different configurations, this study seeks to pinpoint the most promising material combination for further experimental validation.

2. Simulation Methodology and Device Configuration

To investigate the performance of a perovskite solar cell (PSC) using a BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3–based absorber, a systematic simulation approach was employed using SCAPS–1D (version 3.3.07) software. Developed by researchers at the University of Gent in Belgium, SCAPS–1D (Solar Cell Capacitance Simulator) was initially introduced in the 1990s by Professor Marc Burgelman and his team to model thin–film solar cells [24]. This one–dimensional simulator is widely used for photovoltaic device modelling due to its robust handling of complex material properties [25]. SCAPS–1D is particularly effective for PSCs, as it can accurately simulate device performance under varying conditions, including energy band structure, carrier mobilities, doping concentrations, and interface properties [25]. The software enables a thorough analysis of how material modifications impact device efficiency metrics, such as open–circuit voltage (Voc), short–circuit current density (Jsc), fill factor (FF), and power conversion efficiency (PCE) [26].

The device configuration selected for this simulation was FTO/ETL/BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3/HTL/Ir, where different electron transport layers (ETLs), CdS, PCBM, and ZnO were analyzed alongside the BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 absorber layer. The hole transport layers (HTLs) tested included Cu2O, Spiro–OMeTAD, and P3HT, while iridium (Ir) was used as the back contact due to its high work function of 5.67 eV, which facilitates efficient hole extraction. Iridium (Ir) was selected as the back contact, following the approach of Meyer et al. (2025), who demonstrated using SCAPS–1D that Ir (work function ~5.67 eV) provides favorable band alignment and stable electrical behavior compared with other high–work–function metals [27]. Fluorine–doped tin oxide (FTO) was chosen as the transparent conducting oxide (TCO) at the front contact. Optical losses in the FTO layer, including both reflection and absorption, were included in the simulation through its wavelength–dependent refractive index and absorption coefficient, ensuring that the transmitted photon flux into the absorber is realistically reduced.

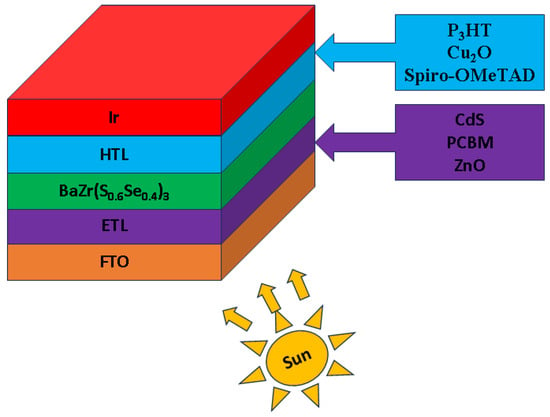

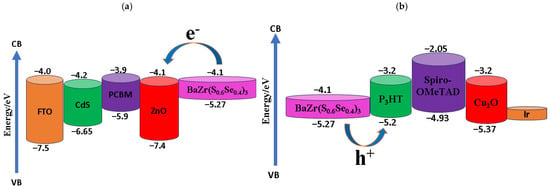

To provide an overview of the simulated structure, Figure 1 presents the full device architecture used throughout this study, including the FTO front contact, chosen ETL, BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 absorber, HTL, and Ir back electrode. This schematic establishes the baseline geometry for all subsequent optimization steps. Following this, Figure 2 illustrates the corresponding band alignment diagrams. Figure 2a shows the alignment between FTO, the different ETLs, and the absorber, while Figure 2b depicts the alignment between the absorber and the various HTLs interfacing with the high–work–function Ir back contact. These diagrams clarify the energetic driving forces for charge extraction in the proposed structures.

Figure 1.

Architectural design of solar cell devices.

Figure 2.

Band alignment of proposed device with (a) varies ETLs between FTO and absorber (BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3) and (b) varies HTLs between work function (Ir) and absorber (BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3).

2.1. Device Modeling and Parameter Selection

In the device modeling and parameter selection process, specific parameters for each layer were referenced from established studies and experimental data, as shown in Table 1. Key properties, including bandgap energy (Eg), electron affinity (χ), dielectric permittivity (er), carrier mobilities (μe and μh), and doping concentrations (ND for n–type and NA for p–type), were carefully assigned to optimize device behavior. For the BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 absorber layer, the bandgap and electron affinity values used align with typical chalcogenide perovskites, with an initial defect density based on reported standards.

Table 1.

Basic parameters of each layer material used for the simulation of PSCs [28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

The mobility, defect density, and doping values used in this simulation are based directly on experimental and numerical data available for BaZr–based chalcogenide perovskites. Recent SCAPS–1D studies of BaZrS3 absorbers by Meyer et al. [27], report parameter ranges that reflect measured transport behavior, donor–type defect formation, and the moderately n–type character commonly observed in BaZr chalcogenide films. Because BaZr(S,Se)3 alloys, including BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3, exhibit similar defect chemistry and charge–transport trends as confirmed by alloy studies, the same experimentally supported parameter ranges apply to the mixed S–Se composition [35]. The defect–density range and doping type used here therefore reflect values already validated in prior SCAPS modeling and experimental thin–film studies, ensuring that the simulation parameters are realistic and literature–supported.

The electron transport layers (ETLs), CdS, PCBM, and ZnO, each have the electron affinities specified in Table 1, facilitating the analysis of their impact on the device. Similarly, the hole transport layers (HTLs), Cu2O, Spiro–OMeTAD, and P3HT were selected considering their bandgap and electron affinities, ensuring alignment with the work function of the back contact, Iridium (Ir). Interface parameters, including the introduction of traps at the ETL/absorber and absorber/HTL interfaces with specified electron and hole capture cross–sections, were modeled following a single–level energetic distribution. The defect energy level was positioned above the highest energy level in alignment with similar PSC studies, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Interface defect parameters [7,33,36,37].

The interface defect parameters in Table 2, used at the ETL/BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 and BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3/HTL contacts, were not chosen arbitrarily. These values were carefully selected based on the ranges reported in previous SCAPS–1D simulations and material studies of BaZrS3, BaZrSe3 and other chalcogenide perovskite solar cells, where mid–gap interface states with typical capture cross–sections are used to represent realistic recombination–active junctions rather than perfectly ideal interfaces. By adopting interface defect energies and capture parameters consistent with these earlier works, our model incorporates physically reasonable interface recombination and maintains consistency with established practices in BaZr–based device simulation.

2.2. Key Equations Applied in SCAPS–1D Simulations

The behavior of charge carriers within the perovskite solar cell (PSC) was modeled using fundamental semiconductor equations commonly applied in SCAPS–1D simulations, including Poisson’s equation, the continuity equations for electrons and holes, and current density equations [38]. These equations govern the movement of charge carriers and the electric field distribution within the device, providing a comprehensive understanding of the device physics [26]. The relationship between electric field (E) and space charge density is expressed in Equation (1) below:

where ψ is the electrostatic potential, q is the elementary charge, is the relative static permittivity of free space, n and p are the electron and hole densities, and are the ionized donor and acceptor densities, respectively, and is the defect density of the acceptor or donor.

Equations (2) and (3) are equations of continuity for electrons and holes, respectively.

where and are the electron current density and the hole current density, respectively, Un,p represents the net recombination rate, and G is the generation rate. Equations (4) and (5) express how the charge carriers in the device move by diffusion and drift for the electrons and holes, respectively:

where Dn is the electron diffusion coefficient, Dp is the hole diffusion coefficient, µn is the electron mobility, µp is the hole mobility, ∅ is the electrostatic potential.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Thickness Optimization

In this work, numerical simulations were conducted to explore the performance of perovskite solar cells (PSCs) with the following configuration: FTO/ETL/BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3/HTL/Ir. Thickness optimization emerged as a critical step in improving the solar cell performance, motivating the systematic optimization of the thicknesses of the HTL, ETL, BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 absorber, and FTO layers. Each layer’s thickness was varied sequentially, while keeping the other layers at their initial thicknesses, to achieve optimal values for parameters such as PCE, FF, Jsc, and Voc. For the starting device configuration, FTO/CdS/BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3/Spiro–OMeTAD/Ir, optimization began with the HTL layer, which included Cu2O, Spiro–OMeTAD, and P3HT as candidates. For each HTL material, its thickness was varied incrementally while the thicknesses of the ETL (CdS, PCBM, or ZnO), the absorber, and the FTO were kept constant. The optimal HTL thickness for each configuration was selected based on its ability to enhance hole transport and minimize recombination losses, ensuring the highest PCE. Once optimized, the HTL thickness was fixed for subsequent layers. Next, the ETL layer was optimized. The thickness of the ETL was systematically varied for each HTL material while maintaining the fixed HTL thickness and initial absorber and FTO thicknesses. The optimization of the ETL focused on improving electron transport and reducing resistive losses. Once the optimal thickness was determined for the ETL in each device, it was fixed, and the absorber layer was optimized. The BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 absorber layer was then optimized to balance light absorption and charge carrier extraction. Its thickness varied over a wide range for each HTL and ETL combination to maximize photocurrent generation and overall efficiency. Finally, the FTO layer’s thickness was optimized to minimize resistive losses while preserving high light transmittance. The sequential optimization process ensured that each layer contributed synergistically to the device’s performance, resulting in the identification of optimal configurations for each HTL and ETL combination.

To clarify the optimization approach used in this study, the thicknesses of the HTL, ETL, absorber, and FTO layers were varied sequentially rather than simultaneously. This means that each layer was optimized while the previously optimized layers were held fixed, resulting in a locally optimized device structure within this step–by–step framework. Because this method does not explore the full multidimensional parameter space, the obtained thicknesses should be regarded as local optima rather than true global optima. A full multi–parameter optimization, where interdependencies between layers are explored (for example, absorber thickness versus ETL or HTL thickness), would provide a more comprehensive picture and represents an important direction for future work.

To examine how layer thickness influences device performance, the optimized thickness values obtained for each transport layer are summarized in Table 3. Table 3 lists the optimized thicknesses of the different HTL materials while keeping the FTO, absorber, and ETL constant, allowing a direct comparison of how each HTL behaves under identical conditions. Building on this, Table 3 presents the optimized thicknesses for the various ETL materials using the same common FTO, absorber, and HTL configuration. This table highlights the impact of ETL thickness on overall device performance and supports the selection of the most effective transport–layer combination.

Table 3.

Thickness of different HTLs materials with common FTO, absorber and, ETL material. Thickness of different ETLs materials with common FTO, absorber and HTL material.

3.2. Simulated J–V and QE for Various ETL and HTL Materials

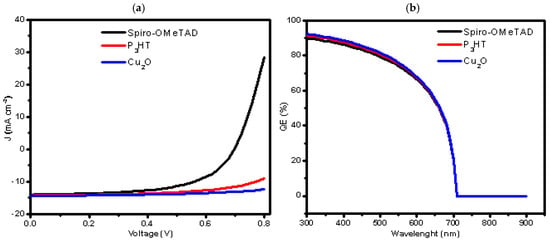

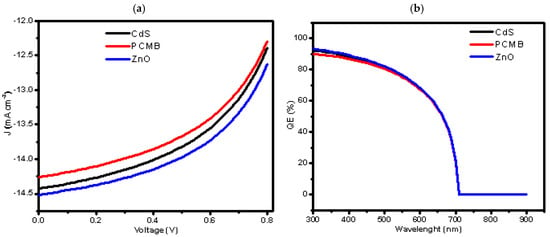

To understand how the choice of charge–transport layers influences the overall behaviour of the BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3–based device, the current density–voltage (J–V) characteristics and external quantum efficiency (QE) spectra were simulated for each ETL and HTL configuration. These two diagnostic tools provide complementary insight into the internal physics of the cell: the J–V curves reveal the combined effects of band alignment, recombination, and resistive losses on parameters such as Voc, Jsc, FF, and PCE, while the QE profiles indicate how efficiently photogenerated carriers are created and extracted across the solar spectrum [9,34]. By comparing the electrical and optical responses of devices incorporating different transport materials, the relative strengths and limitations of each HTL and ETL can be identified and linked directly to variations in device performance. The trends observed in Figure 3 and Figure 4 therefore form the basis for selecting the optimal transport–layer combination for the BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 absorber.

Figure 3.

Simulated characteristics of three devices with different HTL materials (a) J–V curve and (b) Quantum efficiency.

Figure 4.

Simulated characteristics of three devices with different ETL materials (a) J–V curve and (b) Quantum efficiency.

Figure 3a presents the J–V characteristics for different HTLs, where Cu2O shows the highest Voc (2.1043 V, Table 4) but a lower fill factor (32.63%), leading to an overall PCE of 9.91%. This suggests that while Cu2O’s high Voc is promising, improvements in its fill factor could significantly boost efficiency. P3HT strikes a balance with a higher FF of 53.60%, resulting in a competitive PCE of 8.11%. These trends in the J–V curve are directly reflected in the performance metrics detailed in Table 4. In Figure 3b, the quantum efficiency (QE) data shows Cu2O with a broader and higher spectral response, corresponding to the highest Jsc (14.429 mA cm−2) in Table 4. This confirms that Cu2O is more effective at capturing a broader range of light wavelengths, especially beyond 600 nm. P3HT and Spiro–OMeTAD show similar patterns but with reduced efficiency, particularly for Spiro–OMeTAD, which has a lower Jsc (14.038 mA cm−2).

Table 4.

Photovoltaic parameters for devices with CdS as a common ETL material and different HTL (Spiro–OMeTAD, P3HT, Cu2O) materials.

In Figure 4a, the J–V curves for electron transport layers (ETLs) reveal that ZnO provides the best performance, followed closely by PCBM and CdS, which is also supported by Table 5. ZnO delivers a Voc of 2.1793 V, the highest among the ETLs, leading to the best PCE of 10.10%. The fill factor and current density (Jsc) are nearly identical across the three ETLs, but ZnO’s efficiency stems from its superior Voc, making it a preferable choice over CdS and PCBM. Table 5 supports this, as ZnO has the highest Voc, reinforcing the importance of this parameter in optimizing device performance. The QE results in Figure 4b confirm ZnO’s effectiveness in capturing light across a wide spectrum. Its higher response at longer wavelengths suggests better light harvesting properties, contributing to the higher Jsc value (14.512 mA cm−2) in Table 5, compared with the slightly lower Jsc value for PCBM and CdS which is evidence in their lower QE responses at longer wavelengths, confirming ZnO’s superior light absorption capabilities and its resulting higher efficiency particularly at wavelengths beyond 600 nm. These figures and tables demonstrate the clear advantage of ZnO as an ETL and Cu2O as an HTL, with room for further enhancement through improving Cu2O’s fill factor.

Table 5.

Photovoltaic parameters for devices with Cu2O as a common HTL material and different ETL (CdS, PCBM, ZnO) materials.

The relatively high open–circuit voltages observed in the simulated devices arise from the idealized conditions used in the SCAPS–1D model. Because the absorber BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 was simulated with very low bulk and interface defect densities, and with limited non–radiative recombination pathways, the model approaches the radiative–limit behavior. Under such minimized recombination conditions, SCAPS is known to yield voltages that exceed typical experimental values, as discussed by Burgelman [39]. The Voc values shown in Table 4 and Table 5 should therefore be interpreted as theoretical upper limits achievable under nearly loss–free conditions; real devices would exhibit lower voltages once realistic defect states and interface recombination are considered. In addition, the relatively low fill factors reported in the optimized structures stem from recombination at the interfaces and non–ideal band alignment in the ZnO/BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3/Cu2O stack, which introduce resistive and recombination losses near the maximum power point. These effects limit FF even when Voc and Jsc remain high. The absorber and interface parameters, including bandgap, electron affinity, defect densities, capture cross sections, and surface recombination velocities, were re–verified against recent BaZr–based SCAPS studies, and radiative recombination was explicitly enabled to ensure physical consistency in the model.

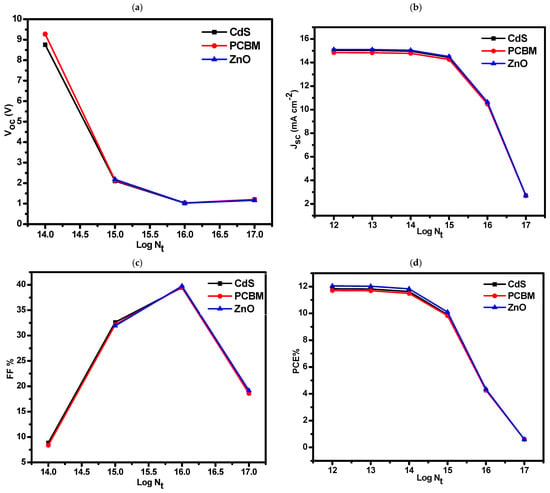

3.3. Effect of Absorber Defect Density (Nt) on Performance with Various ETLs

In the simulation conditions, various physical and operational parameters were systematically varied to understand their effects on device performance. The range of absorber defect densities (Nt = 1012–1017 cm−3) explored in this section includes both realistic values reported for well–crystallized BaZr–chalcogenide films and higher values that represent degraded or defect–rich material. The upper end of the range is therefore used only as an exploratory limit to study how severe non–radiative recombination would influence device performance. The trends shown here should be interpreted with this context in mind. The range of absorber defect densities (Nt = 1012–1017 cm−3) explored in this section includes both realistic values reported for well–crystallized BaZr–chalcogenide films and higher values that represent degraded or defect–rich material. The upper end of the range is therefore used only as an exploratory limit to study how severe non–radiative recombination would influence device performance. The trends shown here should be interpreted with this context in mind. Figure 5 bellow, show the sensitivity of perovskite solar cell (PSC) performance to defect density, revealing how higher defect densities contribute to recombination losses and efficiency decline [40].

Figure 5.

Effect of absorber defect density (Nt) on the photovoltaic performance of BaZr(S0,6Se0,4)3–based perovskite solar cells with different ETLs: (a) open–circuit voltage (Voc), (b) short–circuit current density (Jsc), (c) fill factor (FF), and (d) power conversion efficiency (PCE), as functions of the total absorber defect density (Nt).

In Figure 5, as the defect density (Nt) increases from 1012 to 1017 cm−3, the fill factor (FF) initially rises slightly and then declines sharply. This behavior likely occurs because low defect densities support charge collection, leading to an improvement in FF; however, as Nt increases beyond 1014, the buildup of defects hinders charge extraction, resulting in FF degradation. This trend aligns with findings in other studies, which observed similar FF trends due to recombination effects at higher defect levels [36].

Voc, PCE, and Jsc all decrease as Nt increases, albeit at different rates. The decline in Voc can be attributed to increased recombination due to higher defect states, which reduces the separation potential across the absorber and ETL interfaces. PCE follows this decline, driven by the combination of decreasing Voc and FF. Similar observations were made by Baishya et al. (2024), where increased defect densities in perovskite solar cells led to notable efficiency losses due to enhanced recombination rates and reduced carrier lifetimes [41].

Jsc’s more gradual decrease compared to Voc and FF may result from its reliance on incident light absorption and the generation rate of carriers, which are initially unaffected by moderate defect levels. This trend is consistent with Roy et al. (2020), which found that Jsc typically declines at a slower pace under increased Nt in perovskites, as it depends less directly on recombination factors [42].

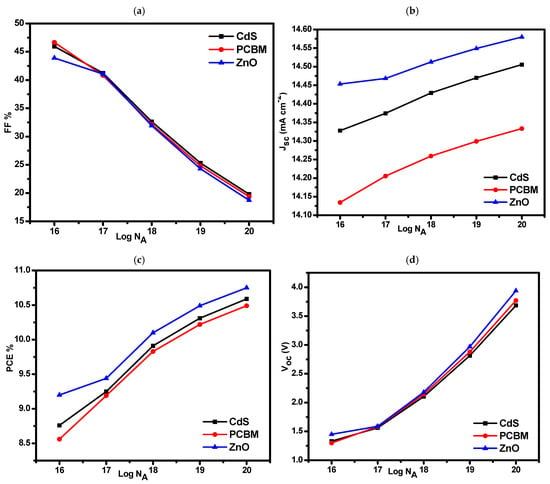

3.4. Impact of Cu2O p–Type Doping (NA) on Device Efficiency Across ETLs

The p–type doping concentration (NA) in the Cu2O hole transport layer (HTL) was varied from 1016 to 1020 cm−3, as illustrated in Figure 6. The lower part of this range corresponds to experimentally reported Cu2O conductivities, whereas values approaching 1020 cm−3 represent highly doped or idealized cases that exceed typical experimental limits. These higher values are included only to probe the sensitivity of device performance to strong p–type doping and should be viewed as exploratory rather than routinely achievable. This range, based on the methodology of Kumar et al. (2023), allows for the investigation of doping’s role in enhancing the electric field, thereby supporting improved charge separation and Voc stabilization [43].

Figure 6.

Effect of Cu2O p–type doping concentration (NA) on the photovoltaic performance of BaZr(S0,6Se0,4)3–based perovskite solar cells with different ETLs: (a) FF%, (b) Jsc, (c) PCE%, and (d) Voc, as functions of the Cu2O acceptor doping concentration (NA).

Figure 6 shows that as the doping density (NA) increases from 1016 to 1020 cm−3, Voc gradually rises, a trend that can be explained by the improved electric field in the depletion region, which facilitates better charge separation. Higher NA effectively reduces the carrier recombination rate, leading to a more stable Voc. This outcome has been corroborated by other studies, such as those by Nalianya et al. (2021), where increased NA positively impacted Voc due to stronger internal electric fields in perovskite layers [44].

Jsc remains nearly constant across the NA range, suggesting that changes in doping density do not significantly affect the light absorption and carrier generation properties of the absorber material. Similar conclusions are found in Wu et al. (2023), who noted that Jsc in PSCs is generally unaffected by moderate NA variations, as light absorption remains stable under typical illumination conditions [45]. Interestingly, FF decreases with increasing NA, while PCE still increases. This trade–off might be due to an increase in series resistance as NA rises, which affects FF. However, the overall improvement in Voc compensates for this effect, leading to a net PCE gain. This pattern is in line with observations by Chawki et al. (2024), who reported that although higher doping levels reduced FF, they improved Voc sufficiently to enhance overall efficiency in PSCs [46].

In addition to these qualitative trends, the behavior of Voc and FF can also be explained using well–established semiconductor principles. As the acceptor doping (NA) increases, the concentration of minority carriers becomes lower in a predictable manner based on equilibrium carrier statistics. This reduction in minority carriers directly suppresses Shockley–Read–Hall (SRH) recombination both at the interface and within the depletion region. With fewer carriers available for recombination, the separation between the electron and hole quasi–Fermi levels increases, which manifests as the observed rise in Voc. The slight decrease in FF at higher NA values aligns with known mobility–related effects: with elevated doping, carrier–carrier scattering becomes more pronounced, reducing mobility and contributing to resistive losses within the device. These trends are consistent with established doping–dependent recombination and mobility behaviors reported in chalcogenide and perovskite semiconductors, where increasing doping strengthens the built–in field but can also introduce mobility limitations and non–radiative pathways at high concentrations. Similar doping–dependent behavior has been reported in other SCAPS–1D studies, where variations in absorber carrier concentration strongly affect Voc and FF, while Jsc remains comparatively stable, as seen in Nalianya et al. for CsSn0.5Ge0.5I3 [44], Srinivasan et al. for BaZrSe3 and related ABSe3 absorbers [47], Aly et al. for BaZrSe3 [33], and Kumar et al. for SnS–based chalcogenide devices [24].

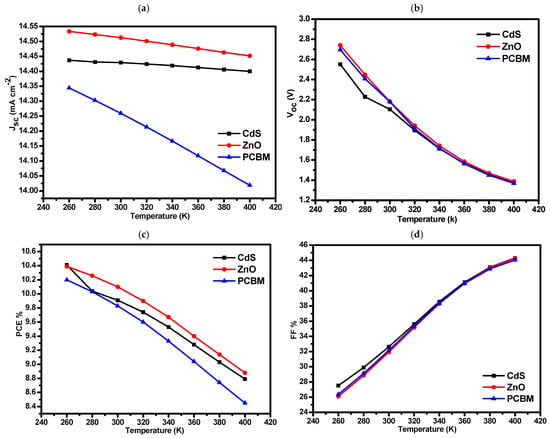

3.5. Temperature Impact on Performance with Different ETLs

In this simulation, the temperature was varied manually from 260 K to 400 K while the remaining material parameters were kept at their predefined or SCAPS default values. As temperature increases, SCAPS internally raises the intrinsic carrier concentration and thermal velocities, which strengthens SRH and radiative recombination and directly contributes to the observed drop in Voc. Because optical absorption was not modified in the model, Jsc remains almost unchanged across the temperature range. Although FF increases slightly due to the thermally assisted improvement in carrier mobility within the transport layers, this enhancement is not sufficient to compensate for the Voc reduction, resulting in the clear overall decrease in PCE shown in Figure 7. Since no extra temperature–dependent laws for bandgap, mobilities, or defect parameters were added beyond SCAPS’ built–in treatment of thermal recombination processes, the decreasing PCE trend represents a physically consistent thermal response of the simulated device.

Figure 7.

Temperature dependence of key photovoltaic parameters for BaZr(S0,6Se0,4)3–based perovskite solar cells employing different ETLs: (a) Jsc, (b) Voc, (c) PCE%, and (d) FF%, illustrating the influence of thermal effects on carrier recombination, transport, and overall device efficiency.

As observed in Figure 7, with an increase in temperature from 260 K to 400 K, Voc decreases, which can be attributed to the enhanced thermal activation of carriers that increases recombination rates. This trend is well–documented in studies like Zhang et al. (2022), where temperature–induced recombination lowered Voc in perovskite solar cells due to reduced charge–carrier separation efficiency at higher temperatures [48]. Despite the decline in Voc, Jsc remains relatively constant, indicating that temperature has less influence on carrier generation rates. This stability in Jsc with rising temperature aligns with findings from AlZoub et al. (2023), who found minimal impact of temperature on Jsc in perovskite devices under similar thermal conditions, attributing this stability to the robustness of light absorption at elevated temperatures [49]. Interestingly, although FF increases with temperature reflecting reduced resistive losses and slightly improved carrier transport this improvement is not sufficient to compensate for the loss in Voc. As a result, the overall PCE still decreases with rising temperature. This behaviour is consistent with temperature–dependent studies reported in the literature. For example, Mercy et al. [50] noted that higher temperature improves FF through enhanced carrier mobility, but the simultaneous reduction in Voc usually dominates and leads to lower efficiency. Similar trends of declining Voc and PCE with increasing temperature have been observed in other perovskite and chalcogenide systems [50].

To strengthen the physical interpretation further, the temperature–dependent trends in Figure 7 can be explained quantitatively using well–known semiconductor behavior. As temperature rises, the intrinsic carrier concentration increases exponentially, which enhances SRH recombination and naturally lowers the achievable Voc. This effect is widely reported in perovskite and chalcogenide semiconductors, where the recombination current dominates the temperature dependence of Voc. In addition, higher temperatures cause a slight narrowing of the bandgap, which further reduces Voc by lowering the energy separation between the quasi–Fermi levels under illumination. Meanwhile, the increase in FF with temperature is consistent with the thermally activated enhancement of carrier mobility, which reduces resistive losses in the transport layers. However, the combined reduction in Voc and the modest variation in Jsc outweigh these mobility gains, leading to the observed decline in overall PCE. These mechanisms are well supported by temperature–dependent studies in chalcogenide and hybrid perovskite devices, which consistently report reduced Voc and PCE with increasing temperature due to enhanced recombination and bandgap narrowing effects. Similar temperature–dependent behavior has been widely reported in recent SCAPS–1D and experimental studies, where rising temperature consistently lowers Voc due to enhanced recombination, while Jsc remains almost unchanged and FF shows moderate improvement. These trends have been observed in AlZoubi et al. for MAGeI3 devices [49], Baishya et al. for perovskite defect–mediated recombination under thermal stress [41], and Zhang et al., who linked elevated temperature to reduced carrier–separation efficiency and a decline in overall PCE despite improved mobility [48].

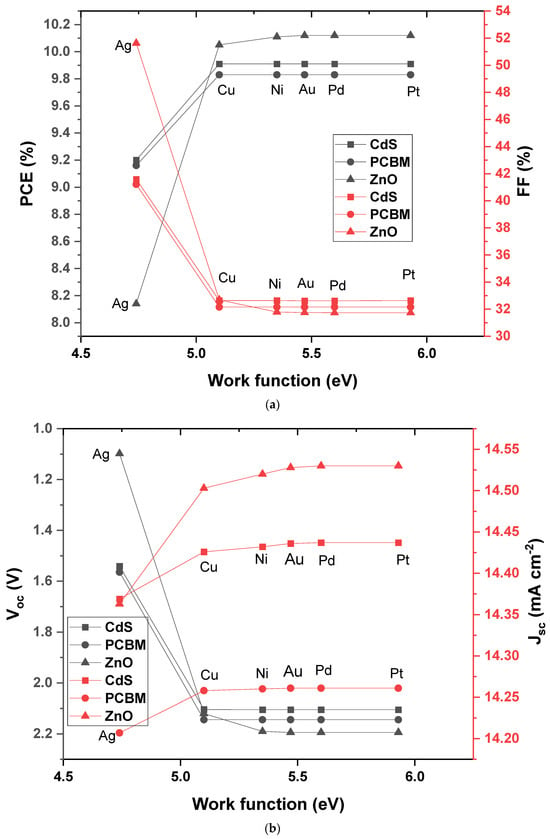

3.6. Effect of Different Work Function on Performance Parameters with Various ETLs

The impact of back contact work function was explored by testing metals with work functions ranging from 4.74 to 5.93 eV (Ag, Cu, Ni, Au, Pd, Pt), as illustrated in Figure 8a,b. This approach identified optimal alignment conditions for efficient charge extraction, confirming observations by Rono et al. (2023) on the critical role of back contact work function in PSC performance [32].

Figure 8.

(a): Effect of different work function on PCE and FF with varying ETL materials. (b): Effect of different work function on Voc and Jsc with varying ETL materials.

In Figure 8a, we observe the effect of different work functions (obtained from different literatures, [26,29,32,51,52]) of back contact metals (Ag, Cu, Ni, Au, Pd, and Pt) on PCE and FF with varying ETL materials (CdS, PCBM, and ZnO) while keeping Cu2O as the HTL. When using CdS as the ETL, Ag (with the lowest work function of 4.74 eV) gives a lower PCE of 9.20% compared to the other metals, which achieve a PCE of 9.91%. This lower efficiency is due to Ag’s lower work function, which creates a less effective barrier for hole extraction, leading to charge recombination at the back contact [53]. This finding aligns with research by Xu et al. (2023), where lower work function metals similarly limited PCE due to inefficient charge extraction [54].

For FF, Ag results in a higher FF of 41.58%, while the other metals show FF values between 32.62 and 33.64. This could be because Ag, despite limiting PCE, provides improved conductivity at the back contact, slightly enhancing the FF. When using PCBM, Ag maintains this trend with a PCE of 9.16% and an FF of 41.21%, while the other metals yield a slightly higher PCE of 9.83% and a lower FF around 32.16%. Studies by Zhou et al. (2022) report similar behavior, where Ag’s high conductivity contributes to improved FF but limited PCE due to suboptimal energy alignment with PCBM [55].

With ZnO as the ETL, Ag’s PCE (8.14%) is notably lower than that of Cu2O (10.05%) and other metals (up to 10.12%), as ZnO requires a high work function metal for efficient hole collection. Higher work function metals like Au and Pt, with values of 5.47 eV and above, align better with ZnO, thereby reducing recombination losses and increasing PCE. These results match findings by Jan and Noman (2023), where metals with work functions closer to ZnO’s electron affinity showed optimal performance in PSCs [56].

In Figure 8b, the back contact metal significantly impacts Voc and Jsc. For CdS as the ETL, Ag gives a lower Voc of 1.5 V, while other metals provide a Voc of 2.1 V. This lower Voc with Ag is due to its lower work function, creating a weaker barrier for holes and resulting in higher recombination rates. The slight increase in Voc with higher work function metals is supported by findings in Menon and Krishnamoorthy (2022), where higher work function metals better matched the absorber material, reducing recombination losses and thus boosting Voc [57].

With PCBM, Ag again shows a lower Voc (1.56 V) compared to the 2.14 V observed with other metals. This aligns with Ag’s limitations in barrier formation for hole collection when paired with an ETL like PCBM, which benefits from metals with higher work functions. For Jsc, the differences across metals are minimal, as the current density primarily depends on the ETL’s light absorption capabilities and is less influenced by the back contact. A study by Patil et al. (2023) confirms this, showing similar Jsc stability across metals in PSCs when using PCBM [58].

Using ZnO as the ETL, Ag shows the lowest Voc (1.1 V), while metals with higher work functions, like Pt and Pd, provide a Voc of 2.2 V, indicating the role of a high work function metal in reducing recombination for ZnO–based devices. Jsc remains stable across metals, slightly increasing with higher work function materials. This consistency is attributed to ZnO’s effective electron transport properties, as reported by Aftab et al. (2023), where ZnO–based devices showed steady Jsc regardless of back contact variations [59].

To contextualize the simulated performance of our BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3 device, Table 6 compares the key photovoltaic parameters reported in previous BaZrS3, BaZrSe3, and BaZr(S,Se)3 studies with the results obtained in this work. The values extracted from literature include bandgaps, open–circuit voltages, current densities, fill factors, and efficiencies, allowing a direct assessment of how the present SCAPS–1D predictions relate to both earlier numerical models and experimentally reported devices.

Table 6.

Comparison of photovoltaic performance parameters for reported BaZrS3, BaZrSe3, and BaZr(S,Se)3 perovskite solar cells and the present simulated device.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we successfully demonstrated the potential of a novel BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3–based absorber for perovskite solar cells (PSCs) through comprehensive simulations using SCAPS–1D. This research highlighted the critical role of material selection and device architecture optimization in achieving superior photovoltaic performance. The systematic exploration of various electron transport layers (ETLs), including CdS, PCBM, and ZnO, and hole transport layers (HTLs) such as Spiro–OMeTAD, P3HT, and Cu2O, revealed ZnO as the optimal ETL and Cu2O as the best HTL. The optimized device configuration, FTO/ZnO/BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3/Cu2O/Ir, achieved a remarkable power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 10.10%, with a short–circuit current density (Jsc) of 14.51 mA/cm2, open–circuit voltage (Voc) of 2.18 V, and fill factor (FF) of 31.93%. Moreover, the incorporation of ZnO and Cu2O as transport layers highlights the significance of selecting materials with optimal energy alignments and high stability under operational conditions. In this study, we revealed that increasing defect density negatively impacts Voc and PCE due to elevated recombination rates, while doping concentration significantly enhances the internal electric field, improving charge separation and stability. Furthermore, the analysis of thermal effects underscored the robustness of the PSC architecture, where higher temperatures increased fill factor (FF) and carrier mobility despite a reduction in Voc. The role of back contact metals was pivotal, with higher work function materials like Pt and Pd enhancing charge extraction efficiency, thereby driving PCE improvements. These findings establish BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3–based PSCs as a promising avenue for future research, providing a strong foundation for experimental validation and further optimization.

The simulation results presented in this study provide guidance for the practical development of BaZr(S0.6Se0.4)3–based chalcogenide perovskite solar cells. The predicted performance trends, particularly the sensitivity to interface quality, absorber defect density, and transport–layer selection offer clear targets for experimental optimization. Recent advances in sulfur–selenium anion–exchange processing suggest that BaZr(S,Se)3 alloys with controlled composition and improved crystallinity are now experimentally achievable, creating a realistic pathway to validate the device configuration proposed here. Future work should focus on thin–film growth, passivation strategies, and interface engineering to evaluate how closely practical devices can approach the performance limits identified by the simulations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M., N.R. and M.A.A.; methodology, L.M.; validation, L.M., N.R. and M.A.A.; formal analysis, L.M., N.R. and M.A.A.; investigation, L.M., N.R. and M.A.A.; resources, S.M., T.N. and E.L.M.; data curation, L.M., N.R. and M.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.; writing—review and editing, E.L.M., N.R., S.M., T.N. and M.A.A.; visualization, E.L.M., N.R., S.M., T.N. and M.A.A.; supervision, E.L.M., N.R., S.M., T.N. and M.A.A.; project administration, E.L.M., N.R., S.M., T.N. and M.A.A.; funding acquisition, E.L.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation grant number (GUN: 137944 and 118947) and the APC was funded by the Govan Mbeki Research and Development Centre (GMRDC) at the University of Fort Hare, South Africa.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Department of Science and Innovation, the National Research Foundation (GUN: 137944 and 118947), and the Govan Mbeki Research and Development Centre (GMRDC) at the University of Fort Hare, South Africa for their financial support. Also, N.R. and L.M. express their gratitude to Marc Burgelman of the University of Gent, Belgium, for granting access to the SCAPS–1D simulation software version 3.3.12.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Coronavirus Crisis Has ‘Severe Impact’ on Global Energy and Oil Markets; Global Oil Demand in 2020 Will Be down Around 90,000 Barrels a Day from 2019, According to the Latest Report from International Energy Agency. M2 Presswire 2020. Available online: https://www.energylivenews.com/2020/03/09/coronavirus-crisis-has-severe-impact-on-global-energy-and-oil-markets/ (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Global Oil Demand ‘Could Exceed Pre–Covid Levels Without Clean Energy Moves’; Figures from International Energy Agency Dash Hopes That World Consumption Had Peaked. The Guardian (London) 2021. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/mar/17/global-oil-demand-could-exceed-pre-covid-levels-without-clean-energy-moves (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Mdleleni, L.; Mlala, S.; Naki, T.; Meyer, E.L.; Agoro, M.A.; Rono, N. Characterization of Perfluoro Sulfonic Acid Membranes for Potential Electrolytic Hydrogen Production and Fuel Cell Applications for Local and Global Green Hydrogen Economy. Fuels 2025, 6, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Duan, R.; Zheng, Z.; Xiao, X.; Shen, C.; Hu, C.; Tang, S.; Qin, W. Grid aided combined heat and power generation system for rural village in north China plain using improved PSO algorithm. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 435, 140461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayhan, A.; Khan, M.; Islam, M.R. Enhancing CsSn0.5Ge0.5I3 Perovskite Solar Cell Performance via Cu2O Hole Transport Layer Integration. Int. J. Photoenergy 2024, 2024, 8859153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.J.; Pereira, A.M.; Moura, N.M.; Neves, M.G. Porphyrin–Based Hole–Transporting Materials for Perovskite Solar Cells: Boosting Performance with Smart Synthesis. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 31196–31219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthick, S.; Velumani, S.; Bouclé, J. Chalcogenide BaZrS3 perovskite solar cells: A numerical simulation and analysis using SCAPS–1D. Opt. Mater. 2022, 126, 112250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahamir, S.R.; Kamarudin, M.A.; Ripolles, T.S.; Baranwal, A.K.; Kapil, G.; Shen, Q.; Segawa, H.; Bisquert, J.; Hayase, S. Enhancing the Electronic Properties and Stability of High–Efficiency Tin–Lead Mixed Halide Perovskite Solar Cells via Doping Engineering. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 3130–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, M.; Amiri, O. Chalcogenide perovskites for solar energy applications: The role of Sn substitution in BaZrS3–based photovoltaic devices. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 168, 112977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartono, N.T.P.; Tremblay, M.–H.; Wieghold, S.; Dou, B.; Thapa, J.; Tiihonen, A.; Bulovic, V.; Nienhaus, L.; Marder, S.R.; Buonassisi, T.; et al. Tailoring capping–layer composition for improved stability of mixed–halide perovskites. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. Energy Sustain. 2022, 1, 2957–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Song, J.; Mao, J.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Deng, Z.; Pan, L.; Yu, Z. Impact of bromide incorporation on strain modulation in 2D Ruddlesden–Popper perovskite solar cells. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Yao, X.; Wu, H.; Zhu, T.; Gong, X. The compositional engineering of organic–inorganic hybrid perovskites for high–performance perovskite solar cells. Emergent Mater. 2020, 3, 727–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent Mercy, E.N.; Srinivasan, D.; Marasamy, L. Emerging BaZrS3 and Ba (Zr, Ti) S3 chalcogenide perovskite solar cells: A numerical approach toward device engineering and unlocking efficiency. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 4359–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, T.; Jamshaid, S.; Monavvar, M.; Wellmann, P. Synthesis of BaZrS3 and BaS3 thin films: High and low temperature approaches. Crystals 2024, 14, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhole, S.; Wei, X.; Hui, H.; Roy, P.; Corey, Z.; Wang, Y.; Nie, W.; Chen, A.; Zeng, H.; Jia, Q. A facile aqueous solution route for the growth of chalcogenide perovskite BaZrS3 films. Photonics 2023, 10, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, I.; Van Sambeek, J.; Simonian, T.; Xu, M.; Ye, K.; Nicolosi, V.; LeBeau, J.M.; Jaramillo, R. A new semiconducting perovskite alloy system made possible by gas–source molecular beam epitaxy. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.10787. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, K.; Sadeghi, I.; Xu, M.; Van Sambeek, J.; Cai, T.; Dong, J.; Kothari, R.; LeBeau, J.M.; Jaramillo, R. A processing route to chalcogenide perovskites alloys with tunable band gap via anion exchange. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2405135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kwok, H.H.; Cheng, J.C. Heritage building facades preservation: Automatic fresh air curtain wall generation for air pollutant dilution based on digital twins. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 90, 109358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zeng, X.; Yan, C.; Yang, S.; Pan, L.; Li, C.; Mu, M.; Li, W.; Tang, G.; Yang, W. Suppressing leakage current and charge accumulation via perovskite interface morphology regulation for efficient light–emitting diodes. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.; Almawgani, A.H.; Das, S.; Pal, A.; Rahman, M.F.; Alhawari, A.R.; Bhattarai, S. Numerical investigation of a high–efficiency BaZr x Ti 1− x S 3 chalcogenide perovskite solar cell. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 2474–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Sengar, B.S.; Kumar, A. FASnI3 and FAMASnGeI3 as absorbers with TCOs as ETLs for eco–friendly high–performance perovskite solar cells. J. Opt. 2024, 54, 1883–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, S.; Borah, J.; Reddy, P.Y.; Sindhupriya, C.; Sathvika, N.; Rajasekaran, S. Device engineering of lead–free FaCsSnI3/Cs2AgBiI6–based dual–absorber perovskite solar cell architecture for powering next–generation wireless networks. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2024, 37, e5903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, N.; Bakkar, A.; Haque, M.D.; Al Ahmed, S.R.; Rahman, M.H.; Irfan, A.; Chaudhry, A.R.; Rahman, M.F. Impact of CdTe BSF layer on enhancing the efficiency of MoSe2 solar cell. J. Opt. 2024, 54, 1246–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Ranjan, R.; Mishra, V.K.; Srivastava, N.; Tiwari, R.N.; Singh, L.; Sharma, A.K. Boosting the efficiency up to 33% for chalcogenide tin mono–sulfide–based heterojunction solar cell using SCAPS simulation technique. Renew. Energy 2024, 226, 120462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatopoulos, P.; Zeneli, M.; Nikolopoulos, A.; Bellucci, A.; Trucchi, D.M.; Nikolopoulos, N. Introducing a 1D numerical model for the simulation of PN junctions of varying spectral material properties and operating conditions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 230, 113819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njema, G.G.; Kibet, J.K.; Ngari, S.M.; Rono, N. Numerical optimization of interface engineering parameters for a highly efficient HTL–free perovskite solar cell. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 108957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, E.L.; Mvokwe, S.A.; Oyedeji, O.O.; Rono, N.; Agoro, M.A. Computational study of chalcogenide–based perovskite solar cell using SCAPS–1D numerical simulator. Materials 2025, 18, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zein, W.; Alanazi, T.I.; Saeed, A.; Salah, M.M.; Mousa, M. Proposal and design of organic/CIGS tandem solar cell: Unveiling optoelectronic approaches for enhanced photovoltaic performance. Optik 2024, 302, 171719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rono, N.; Merad, A.E.; Kibet, J.K.; Martincigh, B.S.; Nyamori, V.O. Simulation of the photovoltaic performance of a perovskite solar cell based on methylammonium lead iodide. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2022, 54, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rono, N.; Merad, A.E.; Kibet, J.K.; Martincigh, B.S.; Nyamori, V.O. A theoretical investigation of the effect of the hole and electron transport materials on the performance of a lead–free perovskite solar cell based on CH3NH3SnI3. J. Comput. Electron. 2021, 20, 993–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Pandey, B.; Dwivedi, D. Modeling of highly efficient and low cost CH3NH3Pb (I1–xClx) 3 based perovskite solar cell by numerical simulation. Opt. Mater. 2020, 100, 109631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rono, N.; Ahia, C.C.; Meyer, E.L. A numerical simulation and analysis of chalcogenide BaZrS3–based perovskite solar cells utilizing different hole transport materials. Results Phys. 2024, 61, 107722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, K.; Thakur, N.; Kumar, P.; Saddeek, Y.; Shater, T.; Ismail, Y.A.; Sharma, P. Optimizing solar cell performance with chalcogenide Perovskites: A numerical study of BaZrSe3 absorber layers. Sol. Energy 2024, 282, 112961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, M.; Taleb–Abbasi, M.; Akhavan, O. Using Cu2O/ZnO as two–dimensional hole/electron transport nanolayers in unleaded FASnI3 perovskite solar cells. Materials 2024, 17, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, N.; Kumar, P.; Neffati, R.; Sharma, P. Design and simulation of chalcogenide perovskite BaZr (S, Se) 3 compositions for photovoltaic applications. Phys. Scr. 2023, 98, 065921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njema, G.G.; Kibet, J.K.; Rono, N.; Ahia, C.C. Numerical simulation of a novel high performance solid–state dye–sensitised solar cell based on N719 dye. IET Optoelectron. 2024, 18, 96–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Khanna, A.; Singh, K.; Patel, S.K.; Singh, H.; Madan, J. Device simulations: Toward the design of >13% efficient PbS colloidal quantum dot solar cell. Sol. Energy 2020, 207, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rono, N.; Merad, A.E.; Kibet, J.K.; Martincigh, B.S.; Nyamori, V.O. Optimization of Hole Transport Layer Materials for a Lead–Free Perovskite Solar Cell Based on Formamidinium Tin Iodide. Energy Technol. 2021, 9, 2100859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgelman, M. Implementing the Shockley–Queisser Efficiency Limit in SCAPS; University of Gent: Ghent, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, F.–T.; Hasan, M.; Hossen, B.; Islam, R. Deep insights into the optoelectronic properties of AgCdF3–based perovskite solar cell using the combination of DFT and SCAPS–1D simulation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baishya, H.; Adhikari, R.D.; Patel, M.J.; Yadav, D.; Sarmah, T.; Alam, M.; Kalita, M.; Iyer, P.K. Defect mediated losses and degradation of perovskite solar cells: Origin, impacts and reliable characterization techniques. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 94, 217–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Sinha, N.K.; Tiwari, S.; Khare, A. Influence of defect density and layer thickness of absorption layer on the performance of tin based perovskite solar cell. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Raipur, India, 21–22 December 2019; p. 012020. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, P.; You, S.; Vomiero, A. Recent progress in materials and device design for semitransparent photovoltaic technologies. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2301555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalianya, M.A.; Awino, C.; Barasa, H.; Odari, V.; Gaitho, F.; Omogo, B.; Mageto, M. Numerical study of lead free CsSn0.5Ge0.5I3 perovskite solar cell by SCAPS–1D. Optik 2021, 248, 168060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Ma, B.; Li, S.; Han, J.; Zhao, W. Powering the Future: A Critical Review of Research Progress in Enhancing Stability of High–Efficiency Organic Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2305445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawki, N.; Essajai, R.; Rouchdi, M.; Braiche, M.; Al–Hattab, M.; Fares, B. Efficacy analysis of BaZrS3–based perovskite solar cells: Investigated through a numerical simulation. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 2024, 11, 389–402. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, D.; Rasu Chettiar, A.–D.; Vincent Mercy, E.N.; Marasamy, L. Scrutinizing the untapped potential of emerging ABSe3 (A = Ca, Ba; B = Zr, Hf) chalcogenide perovskites solar cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Guo, X.; Cui, Z.; Yuan, H.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Fang, J. Strategies for Improving Efficiency and Stability of Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2311025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlZoubi, T.; Mourched, B.; Al Gharram, M.; Makhadmeh, G.; Abu Noqta, O. Improving photovoltaic performance of hybrid organic–inorganic MAGeI3 perovskite solar cells via numerical optimization of carrier transport materials (HTLs/ETLs). Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercy, P.A.M.; Wilson, K.J. Design of an innovative high–performance lead–free and eco–friendly perovskite solar cell. Appl. Nanosci. 2023, 13, 3289–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njema, G.G.; Kibet, J.K.; Rono, N.; Meyer, E.L. Numerical Investigation of a Highly Efficient Hole Transport Layer–Free Solid–State Dye–Sensitized Solar Cell Based on N719 Dye. J. Electron. Mater. 2024, 53, 3368–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, C.; Gupta, G.K.; Mishra, V. Computational analysis of lead free and highly efficient intrinsic Ch3NH3SnI3 based solar cell with suitable transport layers. Results Opt. 2023, 13, 100517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Xue, J.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J.; Wang, T.; He, T.; Fu, G.; Yang, S. Precisely adjusting the organic/electrode interface charge barrier for efficient and stable Ag–based regular perovskite solar cells with >23% efficiency. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 463, 142445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Peng, B.; Davey, K.; Sun, L.; Li, G.; Zhang, S.; Guo, Z. C60 and derivatives boost electrocatalysis and photocatalysis: Electron buffers to heterojunctions. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2302438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Wang, J.; Xu, Z.; Xu, H.; Quan, J.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Tong, Y.; Hu, B.; Chen, L. Recent advances of nonfullerene acceptors in organic solar cells. Nano Energy 2022, 103, 107802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, S.T.; Noman, M. Comprehensive analysis of heterojunction compatibility of various perovskite solar cells with promising charge transport materials. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, V.S.; Krishnamoorthy, A. Hole Selectivity of n–Type Molybdenum Oxide Carrier Selective Layer for Commercial and Emerging Thin–Film Photovoltaics: A Critical Analysis of Interface Energetics and Ensuant Device Physics. Energy Technol. 2023, 11, 2300608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.; Maibam, A.; Sangale, S.S.; Mann, D.S.; Lee, H.–J.; Krishnamurty, S.; Kwon, S.–N.; Na, S.–I. Chemical bridge–mediated heterojunction electron transport layers enable efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 29597–29608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aftab, S.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Hussain, S.; Kabir, F.; Al–Kahtani, A.A.; Hegazy, H.H. Quantum junction solar cells: Development and prospects. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2303449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.