Abstract

The contamination of ecosystems with heavy metals necessitates the inspection of effective, eco-friendly bioremediation strategies over expensive conventional methods. This study examined the capacity of filamentous fungi to withstand and remove heavy metals under controlled laboratory conditions. Fungal isolates were obtained from tree bark and soil samples collected from Coimbatore (Tamil Nadu) and Palakkad (Kerala), India. Preliminary examination revealed that Trichoderma viride PSGSS01, Purpureocillium lilacinum PSGSS05, and Aspergillus nidulans PSGSS08 are potential isolates for the bioremoval of heavy metals. Tolerance assays indicated that T. viride PSGSS01 displayed the greatest resistance, particularly to copper, with a tolerance index of 0.95. Biosorption experiments revealed notable Cu (II), Zn (II), and Co (II) removal efficiencies by T. viride, A. nidulans, and P. lilacinum, respectively. Scanning electron micrographs of metal-exposed mycelia showed pronounced structural alterations. The isolated native ascomycetes demonstrated a higher potential to remove heavy metals. These novel strains are strong candidates for mycoremediation of environments contaminated with multiple heavy metals, as they are not only sustainable but also reusable and can be subjected to the recovery of the metals.

1. Introduction

Urbanization, industrialization, and the use of agrochemicals have led to the pollution of aquatic habitats with heavy metals, which is a growing global concern. The major causes of heavy metal accumulation in water bodies include mining, metallurgical operations, dyeing, tanning, etc. [1,2]. Due to their persistent nature, heavy metals remain in the environment for longer periods and have resulted in bioaccumulation in the food chain [2]. Even at trace concentrations, heavy metals have been reported to be highly toxic [3], and their prevalence in the environment has created apprehensions about their potential effect on human wellness and the habitat [4,5,6,7,8]. Due to the profuse health effects, heavy metals must be removed from aquatic bodies/aqueous solutions.

Conventional strategies or the elimination of heavy metals include electro-/chemical processes, chromatographic techniques, adsorption, etc. [9]. However, these technologies are expensive and energy-intensive [10]. Therefore, the employment of efficient microorganisms for the bioaccumulation of heavy metals provides a constructive substitute [11], as they can withstand elevated concentrations of heavy metals [12] and, especially, molds are suitable agents, as they can disassemble compounds of complexity with their metabolic processes [13].

Fungi are widely distributed, versatile, and better able to adapt to environmental restrictions, such as variations in temperature, raised metal concentrations, pH, and nutrition availability [14]. Due to their commendable aspect ratio, fungal mycelia proliferate to optimize their physiological interaction with contaminants [15]. Mycoremediation is bioremediation that employs molds to segregate pollutants from various substrates [16]. Most of the reported fungal genera exhibiting heavy metal tolerance belong to ascomycetes [13,17]. Fungi take up heavy metals through various modes, including binding to the cell surface (bioadsorption), intracellular accumulation (bioaccumulation), extracellular precipitation, and volatilization [18,19]. Importantly, fungi are non-toxic, sustainable bioadsorbents that can be cultivated on a large scale and are amenable to the recovery of heavy metals. Hence, the current research aimed to isolate indigenous fungi with heavy-metal bioremoval capabilities for application as bioadsorbents for heavy metals in mycoremediation processes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aqueous Solution of Metal Ions

Heavy metal-containing corresponding salts, viz., cadmium nitrate [Cd (NO3)2], cobalt chloride [CoCl2], potassium dichromate [K2Cr2O7], copper nitrate [Cu (NO3)2], lead nitrate [Pb (NO3)2], nickel nitrate [Ni (NO3)2], and zinc nitrate [Zn (NO3)2] (Hi-Media Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India), were dissolved in double-distilled water and sterilized using a 0.2 µm filter (PTFE Millipore filter) to prepare the required solution for the experiments.

2.2. Isolation of Filamentous Fungi

For the present study, soil (100 g) and wood bark (1 cm3 sections) samples were collected in sterile polythene collection bags from Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu state, and Palakkad district, Kerala state, India, and transferred to the laboratory and processed within 24 h. The serially diluted soil samples were spread over Sabouraud’s dextrose agar (SDA) plates and kept at 28 °C for 7 days. The bark samples were inoculated directly into sterile Sabouraud’s dextrose broth (SDB) and incubated at 28 °C for 5 d. Subsequently, the serially diluted broth was spread on SDA and incubated at 28 °C for 7 d [20]. The single spore isolates [21] were stored in 0.85% saline at 27 °C.

2.3. Screening of Fungi for Heavy Metal Tolerance

Spores from the fungal colonies on potato dextrose agar (PDA) were suspended in sterile distilled water, followed by the addition of one or two drops of Tween 20 to facilitate better suspension. Sterile composite media agar plates (MgSO4·7H2O, 0.1 g/L; NaCl, 1 g/L; K2HPO4, 0.5 g/L; NH4NO3, 0.5 g/L; yeast extract, 2.5 g/L; glucose, 10 g/L; pH 6.8 ± 0.2) amended with 175 mg/L [25 mg/L of each metal Cd (II), Cr (VI), Co (II), Cu (II), Ni (II), Pb (II), and Zn (II)] of multi-metal salt solution were prepared [22]. The plates were inoculated with 30 µL of the spore suspension and incubated at 28 °C for 7 d. The isolates that formed distinct growth on the multi-metal amended composite media were considered for further experiments.

2.4. Characterization of Heavy Metal-Resistant Fungi

For morphological characterization, the colony characteristics of the 5–7-day-old culture of test isolates on PDA & Czapek-Dox agar (CDA) were observed. The microscopic features were recorded after lactophenol cotton blue wet mount preparation [20] under 40× and 100× objectives of Trinocular Research Microscope (Model: Axio Scope A1- Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany.

The DNA was purified from the fungi with a DNA extraction kit from Bogar Bio Bee Stores Pvt Ltd., Coimbatore, India. The purity was assayed spectrophotometrically, and the DNA was visualized on 1% agarose gel after electrophoresis. The amplification of extracted DNA was carried out using internal transcribed space (ITS) region primer sets: ITS1—Forward: 5′ TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG 3′ and ITS4—Reverse: 5′ TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC 3′. The amplicons were sequenced (Model: ABI 3730XL, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The sequences were analysed employing Chromas Life (Technelysium Pvt. Ltd., Madurai, India), BioEdit, Clustal X 2.0.11 and subjected to a BLAST (blastn suite) search against sequences available at National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), and the sequenced data were submitted to GenBank.

2.5. Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) of Heavy Metals Against the Fungal Isolates

Spore suspensions of the test isolates were prepared by counting spores with a Haemocytometer under a light microscope to achieve a desired concentration (equivalent to 1.2 × 106 CFU/mL). Sterile potato dextrose agar (PDA), with appropriate concentrations of individual metals, was inoculated with 30 µL spore suspension (106 spores/mL) and incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 7 d. The MIC was noted as the lowest concentration of the heavy metal that could inhibit the growth of the fungal isolate.

2.6. Evaluation of Heavy Metal Tolerance Index of the Isolates

Heavy metal tolerance of test fungal isolates was assessed on appropriate Composite media agar plates amended with 30 mg/L, 60 mg/L, and 100 mg/L of specific metals [Cd (II), Cr (VI), Co (II), Cu (II), Pb (II), Ni (II), and Zn (II)]. Composite media agar plates without heavy metals were used as growth control. Exactly, 30 µL of spore suspension of test fungal isolates were inoculated at the center of the plates and incubated at 28 ± 2 °C for 7 d. Following incubation, the radial growth diameter (mm) of the fungal colony was measured, and the tolerance index (TI) was calculated as follows:

2.7. Quantification of Heavy Metal Removal

Appropriate 250 mL conical flasks containing SDB (100 mL) amended with 50 mg/L of individual metals were inoculated with 1.0 mL spore suspension (106 spores/mL) and kept for 7 d at 28 ± 2 °C. Subsequently, the biomass was recovered by filtration and dried at 60 °C to a constant weight. Precisely, 10 mL of culture filtrate was centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was subjected to acid digestion as described by Uddin et al. (2016) [23], and the metal ions in the samples were quantitatively determined through atomic absorption spectroscopy (Model: AA-6300, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The metal removal efficiency of the test isolates was calculated according to Zhang [24].

2.8. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Analysis

One sample each of pristine and treated biomass of all three isolates was subjected to SEM analysis. Conical flasks containing 100 mL of sterile potato dextrose broth with heavy metal (50 mg/L) were inoculated with 1 mL of spore suspension (106 spores/mL) of the test isolates and incubated for 7 d at 30 °C in an orbital shaker (Model: RIS-24, Remi Elektrotechnik Limited, Mumbai, India) at 100 rpm. The air-dried mycelia were fixed for two hours with 2.5% (v/v) aqueous glutaraldehyde, followed by centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 15 min. The mycelial mass was dehydrated using a gradient of ethyl alcohol (10–100%), followed by a final wash with pure ethyl alcohol, and was stored at −30 °C overnight. The lyophilized (Model: Christ Alpha 1-2 LD Plus, Sigma Laborzentrifugen GmbH) preparation was subjected to field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE SEM) analysis at various magnifications (Model: Zeiss SIGMA VP-FESEM, Germany). The images were examined to determine differences in surface morphology and texture of the pristine and metal-loaded fungal biomass.

3. Results

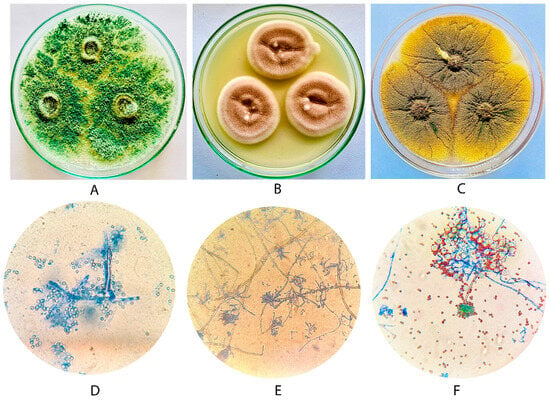

A total of 5 bark samples from Palakkad, Kerala, and 7 soil samples rich in organic matter from Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, were collected and appropriately processed for the isolation of filamentous fungi. The isolates (n = 32) obtained were morphologically characterized as Alternaria sp. (n = 1), Aspergillus spp. (n = 8), Bipolaris spp. (n = 5), Cladosporium sp. (n = 1), Fusarium spp. (n = 3), Mucor spp. (n = 5), Penicillium spp. (n = 6), Purpureocillium sp. (n = 1), and Trichoderma spp. (n = 2). The higher metal tolerance served as the basis for screening the robust fungal strains. Three isolates that had a colony diameter of at least 45 mm on day 8 in multi-metal-amended composite media were selected for further studies (Table 1). Molecular characterization of the selected fungal isolates, based on ITS sequencing, confirmed the identity of the strains as Trichoderma viride PSGSS01 (GenBank Accession No. PP033757), Purpureocillium lilacinum PSGSS05 (GenBank Accession No. OR994706), and Aspergillus nidulans PSGSS08 (GenBank Accession No. OR994710) (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Growth of selected fungal isolates on multi-metal amended composite media.

Figure 1.

Colony morphology of selected fungal isolates on Czapek-Dox agar and observation under 40× of light microscope after lactophenol cotton blue wet mount of Trichoderma viride PSGCSS01 (A,D), Purpureocillium lilacinum PSGSS05 (B,E) and Aspergillus nidulans PSGSS08 (C,F).

3.1. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of Fungal Isolates

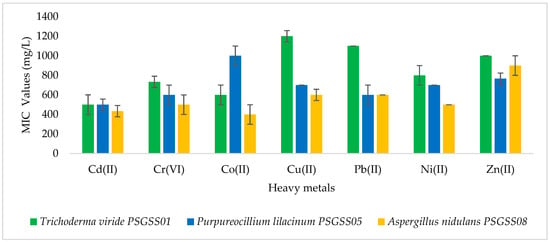

MICs of the heavy metals against the test isolates ranged from 400 mg/L to 1200 mg/L. From Figure 2, it could be inferred that the highest MIC value of 1200 mg/L of Cu (II), followed by 1100 mg/L of Pb (II), was recorded against T. viride PSGSS01. T. viride PSGSS01 showed the highest overall MIC (1200 mg/L) for Cu (II). Among the other two, P. lilacinum had the highest MIC for Co (II) (1000 mg/L) and A. nidulans for Zn (II) (900 mg/L). Compared to the other two isolates, T. viride PSGSS01 required a higher concentration of heavy metals for inhibition. The lowest MIC of 400 mg/L was recorded with Co (II) and Cd (II) against A. nidulans PSGSS08.

Figure 2.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations of heavy metals against the fungal isolates.

3.2. Tolerance Index of Test Fungal Isolates

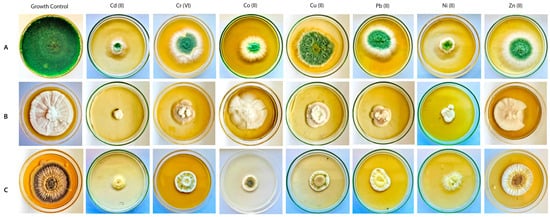

The tolerance of the three test isolates was diverse at varying concentrations of heavy metals (Table 2). When compared to other isolates, T. viride PSGSS01 exhibited higher tolerance to all the heavy metals analyzed, notably toward Cu (II) (0.95 TI at 30 mg/L; 0.87 at 60 mg/L & 0.83 at 100 mg/L), Pb (II) (0.9 TI at 30 mg/L; 0.84 TI at 60 mg/L), and Zn (II) (0.88 TI at 30 mg/L). A. nidulans PSGSS08 recorded the highest tolerance index of 0.86 at 30 mg/L of Zn (II). P. lilacinum PSGSS05 exhibited high metal tolerance to Co (II) (0.85 TI at 30 mg/L, 0.72 TI at 60 mg/L & 0.67 TI at 100 mg/L). Also, none of the isolates was inhibited in the experiment. Of all the values, the lowest TI of 0.12 was recorded for P. lilacinum PSGSS05 at 100 mg/L of Cd (II) (Table 2; Figure 3).

Table 2.

Tolerance Index of fungal isolates to heavy metals.

Figure 3.

Growth of T. viride PSGSS01 (A), P. lilacinum PSGSS05 (B) and A. nidulans PSGSS08 (C) on composite media plates supplemented with 100 mg/L of heavy metals.

3.3. Bioaccumulation Efficiency

The heavy metal removal/bioaccumulation capabilities of the test isolates varied with the metals subjected to analysis. T. viride PSGSS01 recorded the highest removal efficiency of 91.28% for Cu (II), followed by Pb (II) (77.59%) and Zn (II) (65.43%). P. lilacinum PSGSS05 removed Co (II) at a higher rate of 82.70%, followed by Cu (II) and Pb (II) at 75.74% and 73.76%, respectively. Interestingly, A. nidulans PSGSS08 had the highest capacity to remove Zn (II), with a removal efficiency of 89.32%, followed by Pb (II) (75.48%). The highest dry biomass of 5.32 g/L was recorded for T. viride PSGSS01 in Cu (II), followed by A. nidulans PSGSS08 (4.98 g/L) in Zn (II) and P. lilacinum PSGSS05 (3.91 g/L) in Co (II). The results showed that the heavy metal removal efficiency was proportional to the biomass (Table 3). None of the test isolates could efficiently remove Cd (II) and Ni (II). In contrast to the other two isolates, A. nidulans PSGSS08 removed Cr (VI) efficiently (43.28%). There was no notable difference in the accumulation of Pb (II) by the test isolates, as the removal efficiency ranged from 73.76% to 77.59% for all isolates.

Table 3.

Heavy metal removal efficiency of the fungal isolates.

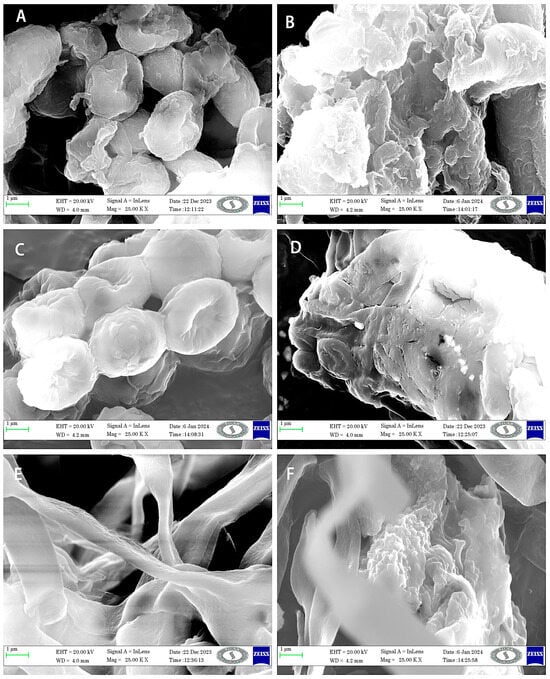

3.4. SEM Analysis

Stemming from the results of tolerance studies, T. viride PSGSS01, P. lilacinum PSGSS05, and A. nidulans PSGSS08 were treated with 50 mg/L of Cu (II), Co (II), and Zn (II), respectively, and the treated and pristine hyphal filaments were subjected to SEM analysis. It was observed that there were morphological variations between the pristine and heavy metal-treated fungal hyphae. The hyphae of the pristine biomass were normal, and no distortions were observed. The biosorption of heavy metals by the treated mycelium was confirmed by identifiable anomalies in the hyphal filaments (Figure 4), including distorted cell walls, shrunken regions, and clumping and clustering of filaments.

Figure 4.

SEM micrograph of the pristine and heavy metal-treated biomass [pristine (A) and Cu (II) treated T. viride PSGSS01 (B); pristine (C) and Co (II) treated P. lilacinum (D); pristine (E) and Zn (II) treated A. nidulans PSGSS08 (F)].

4. Discussion

Owing to the specificity, affordability, and reusability of biomass, biosorption offers numerous benefits over heavy metal removal methods [25]. Due to the biomass production capacity, fungi are widely considered for heavy metal biosorption [26]. The heavy metal tolerance among fungal species has been mainly attributed to extracellular and intracellular sequestration of metals [27]. As fungi have the intrinsic capability to tolerate environmental extremities, mycoremediation strategies are gaining substantial attention for the bioremediation of heavy-metal-polluted sites. The fungal cell wall composition, including chitin, and the production of extracellular enzymes and acids have been attributed to their heavy metal tolerance, biosorption, and detoxification [28]. Analogous to the present study, Alvarado-Campo et al. (2023) [29] and Shalaby et al. (2023) [30] have isolated heavy metal-tolerant fungi from under-explored regions and uncontaminated heavy metal soil samples.

The highest MIC value for Zn (II) against T. viride was reported by Konieczna et al. (2024) [31]. T. viride isolated from municipal solid wastes susceptible to 5 mg/L of Cd and 50 mg/L of Cu was reported by Manna et al. (2020) [32]. According to Siddiquee et al. (2013) [33], the T. virians strain T128 exhibited the highest tolerance for Ni3+ and Pb2+ at 1200 mg/L concentration, and the values are comparable to the present study. P. lilacinum isolated from the soil of cadmium plant tolerated 9.22 mg/L of Cd, 6.2 mg/L of Zn, 2.22 mg/L of Cu, 7.25 mg/L of Pb, and 0.5 mg/L of Co [34]. Xia et al. (2015) [35] reported that P. lilacinum XLA isolated from Cd-contaminated soil had higher MICs of Cd (II), Co (II), Zn (II), Cu (II), and Cr (VI) at 29786 mg/L, 2945 mg/L, 9425 mg/L, 5080 mg/L, and 204 mg/L, respectively, which is quite high when compared to current research. Elkhawaga (2011) [36] specified that A. nidulans isolated from wastewater-treated agricultural soil had Co (II), Pb (II), Zn (II), and Ni (II) MICs of 700 mg/L, 1000 mg/L, 5000 mg/L, and 400 mg/L, respectively.

Overall, the results of the present study indicated that all three test isolates could tolerate heavy metals efficiently, and the highest tolerance was exhibited by T. viride PSGSS01.

P. lilacinum M15001, tolerant to 6.3 mg/L of Cu2+ isolated from a water and sediment sample (river), was reported by Oggerin et al. (2024) [37]. Kerga et al. (2023) [38] reported that P. lilacinum had a Cr (VI) tolerance index of 1.19 ± 0.23 at 0.1 g/L of K2Cr2O7. P. lilacinus from Pb-polluted soil samples was able to tolerate 1437 mg/L of Pb, as stated by Zucconi et al. (2003) [39]. According to Hassan et al. (2019) [40], P. lilacinus (MH541018) from heavy metal-contaminated landfill soil showed a TI of 0.5 and 0.6 for Cu and Fe & Mn, respectively. Mohmmadian Fazli et al. (2015) [41] reported Cd TI of 0.56 and 0.52 at 200 mg/L for Paecilomyces sp. G and Paecilomyces sp. 9, respectively. The findings of Prakash et al. (2023) [42] revealed that Trichoderma spp. isolated from soil related to mining activity exhibited a lead TI of 0.83 at 100 mg/L & 0.42 at 200 mg/L and Zinc TI of 0.79 at 10 mg/L. De Padua et al. (2021) [43] reported six strains of Trichoderma spp. isolated from marine and terrestrial environments had considerable growth in the presence of 1200 mg/L nickel. The Trichoderma F14 strain from heavy metal-contaminated soil sludge showed TI of 1 at 0.6 mg/L Cd & Ni and 1.63 mg/L Zn [44]. According to Chauhan et al. (2020) [45], lead TI of alkali-treated Aspergillus spp. isolated from wastewater-irrigated agricultural soil, it ranged from 0.3 to 0.5 at a 1.45 mg/L concentration. A. niger isolated from tannery discharge with Cr (VI) TI of 1.175 was reported by Sule et al. (2022) [46].

The results of this investigation prove that all the test isolates can accumulate heavy metals. Comparable to the present study, Ting and Choong (2009) [47] reported that Trichoderma sp. SP2F1 was a promising candidate for Cu (II) removal. Efficient biosorption of Cr (VI), Ni (II), and Zn (II) ions from aqueous solution by T. viride biomass was reported by Kumar et al. (2011) [48]. Parallel to the present study, Ali and Hashem (2007) [49] reported 68.3% and 54.3% removal of Pb (II) and Zn (II) by T. viride. This study documented a low uptake of Ni (II) by T. viride (9.47 mg/g). Like the current investigation, De Padua and dela Cruz (2021) [43] reported lower Ni (II) removal (20–30%) capacity of T. asperellum and T. virens. Contrary to this, a 47.6 mg/g biosorption of Ni (II) by T. viride was reported by Sujatha et al. (2012) [50]. Ameen et al. (2024) [51] reported 60.87–76.96%, 61.95–82.50%, 74–86.32%, 60.96–71.11%, 79.2–85.72%, and 54.8–73.62% removal efficiency of Ni2+, Cr6+, Zn2+, Cu2+, Cd2+, and Pb2+, respectively, by Purpureocillium sp. isolated from wastewater from a refinery. According to Xia et al. (2015) [35], P. lilacinum XLA isolated from Cd-polluted soil demonstrated a high capability to adsorb Cd2+. The efficient uptake of Zn2+ and Pb2+ by Paecilomyces marquandii was reported by Słaba and Długoński (2011) [52]. P. lilacinum (#NIOSN-SK56-S76) isolated from Arabian sea sediment was able to remove 8 mg Cr/g biomass [53]. The effective biosorption potential of P. lilacinus is also documented by Yang et al. (2024) [54] and Kerga et al. (2023) [38]. Barros Júnior et al. (2003) [55] reported that A. niger biomass (0.7 g/L) could remove 5 to 10 mg/L of cadmium. Aspergillus spp. displaying sorption capacity of 32–41 mg/g Pb2+ and 3.5–6.5 mg/g Cu2+ dry weight of mycelia was reported by Gazem and Nazareth (2013) [56]. The proportionality in Cu (II) uptake with the increase in A. tamarii NRC3 biomass was described by Saad et al. (2019) [57]. Bioadsorption of Cr and Cd by Aspergillus sp. from sewage/industrial effluent-treated agricultural soil ranged from 6.2–9.5 mg and 2.3–8.21 mg/g of dry biomass [58].

Similar to the results of the SEM analysis in the present study, Lotlikar et al. (2018) [53] observed irregularities in the mycelia in Cr (VI) treated P. lilacinum. The findings of the present investigation of heavy metal-induced morphological changes in fungal hyphae is supported by the reports of Chen et al. (2019) [1].

The differences in the performance of the three isolates employed in the present investigation may be attributed to variations in their metabolic capabilities, including the secretion of diverse extracellular enzymes, organic acids, charges on the cell wall, concentration of various pigments, including melanin, etc. The results presented here are from the experiments run under controlled laboratory conditions. These results must be further experimentally verified to overcome the limitations of the present study, including the biosorption behavior of the isolates in different environmental conditions (pH, temperature, presence of other chemicals/ions/pollutants), commercial workability for the biomass production, desorption feasibilities for the reuse of biomass, etc.

5. Conclusions

Heavy metal tolerance characteristics of Trichoderma viride PSGSS01, Purpureocillium lilacinum PSGSS05, and Aspergillus nidulans PSGSS08 are well documented in the current study through their MICs, Tis, and bioaccumulation. These native isolates effectively removed all the heavy metals, Cu (II), Co (II), and Zn (II), in particular, except Cd (II) and Ni (II). Hence, these isolates are suitable candidates for the biosorption of heavy metals from aqueous solutions/environments. Exploration of the limitations discussed, the large-scale production of fungal biomass of these potential fungi, and their subsequent utilization in a suitably designed bioreactor for the biosorption and detoxification of heavy metals from polluted water is a promising and sustainable technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.S., S.P., and P.M.; methodology, S.P., M.S., and R.A.; software, P.M., C.S.S., and R.V.; validation, C.S.S., S.S., and M.J.; formal analysis, P.M., S.S., and M.J.; investigation, S.P.; resources, S.P., C.S.S., and P.M.; data curation, C.S.S. and P.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P.; writing—review and editing, R.V., M.S., and R.A.; visualization, S.P. and C.S.S.; supervision, C.S.S. and P.M.; project administration, C.S.S. and P.M.; funding acquisition, S.P., C.S.S., P.M., and R.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Management of PSG College of Arts & Science, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu 641 014, India, for extending the required research facilities. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Majmaah University for funding this work under the project number R-2025-2225.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, S.H.; Cheow, Y.L.; Ng, S.L.; Ting, A.S.Y. Mechanisms for metal removal established via electron microscopy and spectroscopy: A case study on metal tolerant fungi Penicillium simplicissimum. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 362, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Srivastava, S.; D’Souza, S.F. An integrative approach toward biosensing and bioremediation of metals and metalloids. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 15, 2701–2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huët, M.A.L.; Puchooa, D. Bioremediation of heavy metals from aquatic environment through microbial processes: A potential role for probiotics. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2017, 5, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, M.; Freitas, H. Influence of metal resistant-plant growth-promoting bacteria on the growth of Ricinus communis in soil contaminated with heavy metals. Chemosphere 2008, 71, 834–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coradduzza, D.; Congiargiu, A.; Azara, E.; Mammani, I.M.A.; De Miglio, M.R.; Zinellu, A.; Carru, C.; Medici, S. Heavy metals in biological samples of cancer patients: A systematic literature review. Biometals 2024, 37, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Liu, G.; Yousaf, B.; Ahmed, R.; Rashid, M.S.; Irshad, S.; Shakoor, A.; Farooq, M.R. Morpho-chemical characterization and source apportionment of potentially toxic metal(oid)s from school dust of second largest populous city of Pakistan. Environ. Res. 2021, 196, 110427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, P.R.S.; Fernandes, G.J.T.; Moraes, E.P.; Moreira, L.F.F. Tropical climate effect on the toxic heavy metal pollutant course of road-deposited sediments. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 251, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuana, R.A.; Okieimen, F.E. Heavy metals in contaminated soils: A review of sources, chemistry, risks and best available strategies for remediation. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2011, 2011, 402647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zeng, G.M.; Huang, J.H.; Zhang, D.M.; Shi, L.J.; He, S.B.; Ruan, M. Simultaneous removal of cadmium ions and phenol with MEUF using SDS and mixed surfactants. Desalination 2011, 276, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.L. Zn biosorption by Rhizopus arrhizus and other fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999, 51, 686–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, J.; Rajib, M.M.R.; Khan, M.N.E.A.; Khandaker, S.; Zubayer, M.; Ashab, K.R.; Kuba, T.; Marwani, H.M.; Asiri, A.M.; Hasan, M.M.; et al. Assessment of heavy metals accumulation by vegetables irrigated with different stages of textile wastewater for evaluation of food and health risk. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo Alkasem, M.I.; El-Abd, M.A.E.H.; Maany, D.A.; Ibrahim, A.S.S. Hexavalent chromium reduction by a potent novel Haloalkaliphilic Nesterenkonia sp. strain NRC-Y isolated from hypersaline soda lakes. Egypt. J. Chem. 2023, 66, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaksmaa, A.; Guerrero-Cruz, S.; Ghosh, P.; Zeghal, E.; Hernando-Morales, V.; Niemann, H. Role of fungi in bioremediation of emerging pollutants. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1070905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, P.; Malik, A. Process optimization for efficient dye removal by Aspergillus lentulus FJ172995. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 185, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, V.; Singh, D.P. Biodegradation of lindane pesticide by non white-rots soil fungus Fusarium sp. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 1747–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, M.K.; Panda, J.; Panda, B.P.; Mohanta, T.K.; Mohanta, Y.K. Mycoremediation of heavy metals and/or metalloids in soil. In Land Remediation and Management: Bioengineering Strategies; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 161–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Chen, D.; Xu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Huang, J.; Hou, Q. Effects of different heavy metal stressors on the endophytic community composition and diversity of Symphytum officinale. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, V.; Pandey, S.C.; Sati, D.; Bhatt, P.; Samant, M. Microbial interventions in bioremediation of heavy metal contaminants in agroecosystem. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 824084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Văcar, C.L.; Covaci, E.; Chakraborty, S.; Li, B.; Weindorf, D.C.; Frențiu, T.; Pârvu, M.; Podar, D. Heavy metal-resistant filamentous fungi as potential mercury bioremediators. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.T.; Mahalakshmi, R.; Revathy, K.; Panneerselvam, K.; Manikandan, P.; Shobana, C.S. Effectiveness of application of lignolytic fungal strains, Cladosporium uredinicola GRDBF21 and Bipolaris maydis GRDBF23 in the treatment of tannery effluent. J. Environ. Biol. 2019, 40, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.S.; Kunimoto, R.K.; Ko, W.H. A simple technique for purifying fungal cultures contaminated with bacteria and mites. J. Phytopathol. 2001, 149, 509–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.; Gola, D.; Mishra, A.; Malik, A.; Kumar, P.; Singh, D.K.; Patel, N.; von Bergen, M.; Jehmlich, N. Comparative performance evaluation of multi-metal resistant fungal strains for simultaneous removal of multiple hazardous metals. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 318, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uddin, A.H.; Khalid, R.S.; Alaama, M.; Abdualkader, A.M.; Kasmuri, A.; Abbas, S.A. Comparative study of three digestion methods for elemental analysis in traditional medicine products using atomic absorption spectrometry. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ren, H.X.; Zhong, C.Q.; Wu, D. Biosorption of Cr (VI) by immobilized waste biomass from polyglutamic acid production. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, J.N.; Oommen, C. Removal of heavy metals by biosorption using freshwater alga Spirogyra hyalina. J. Environ. Biol. 2012, 33, 27. Available online: http://www.jeb.co.in./journal_issues/201201_jan12/paper_05.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025). [PubMed]

- Shakya, M.; Sharma, P.; Meryem, S.S.; Mahmood, Q.; Kumar, A. Heavy metal removal from industrial wastewater using fungi: Uptake mechanism and biochemical aspects. J. Environ. Eng. 2016, 142, C6015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzy, E.M.; Abdel-Motaal, F.F.; El-zayat, S.A. Biosorption of heavy metals onto different eco-friendly substrates. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2017, 9, 35–44. Available online: https://academicjournals.org/journal/JTEHS/article-full-text-pdf/36A24FA64028 (accessed on 5 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Priyanka; Dwivedi, S.K. Fungi mediated detoxification of heavy metals: Insights on mechanisms, influencing factors and recent developments. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 53, 103800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Campo, K.L.; Quintero, M.; Cuadrado-Cano, B.; Montoya-Giraldo, M.; Otero-Tejada, E.L.; Blandón, L.; Gómez-León, J. Heavy metal tolerance of microorganisms isolated from coastal marine sediments and their lead removal potential. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, M.A.; Matter, I.A.; Gharieb, M.M.; Darwesh, O.M. Biosorption performance of the multi-metal tolerant fungus Aspergillus sp. for removal of some metallic nanoparticles from aqueous solutions. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczna, W.; Turkan, S.; Warchoł, M.; Skrzypek, E.; Dąbrowska, G.B.; Mierek-Adamska, A. The Contribution of Trichoderma viride and Metallothioneins in Enhancing the Seed Quality of Avena sativa L. in Cd-Contaminated Soil. Foods 2024, 13, 2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, M.C.; Sahu, A.; De, N.; Thakur, J.K.; Mandal, A.; Bhattacharjya, S.; Manna, M.C.; Sahu, A.; De, N.; Thakur, J.K.; et al. Novel bio-filtration method for the removal of heavy metals from municipal solid waste. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 17, 100619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiquee, S.; Aishah, S.N.; Azad, S.A.; Shafawati, S.N.; Laila Naher, L.N. Tolerance and biosorption capacity of Zn2+, Pb2+, Ni3+ and Cu2+ by filamentous fungi (Trichoderma harzianum, T. aureoviride and T. virens). Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2013, 4, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Tang, J.; Yin, H.; Liu, X.; Jiang, P.; Liu, H. Isolation, identification and cadmium adsorption of a high cadmium-resistant Paecilomyces lilacinus. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 9, 6525–6533. Available online: https://academicjournals.org/journal/AJB/article-abstract/FD2504321500 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Xia, L.; Xu, X.; Zhu, W.; Huang, Q.; Chen, W. A comparative study on the biosorption of Cd2+ onto Paecilomyces lilacinus XLA and Mucoromycote sp. XLC. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 15670–15687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkhawaga, M.A. Morphological and Metabolic Response of Aspergillus nidulans and F. oxysporum to Heavy Metal Stress. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2011, 7, 1737–1745. Available online: https://www.aensiweb.com/old/jasr/jasr/2011/1737-1745.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Oggerin, M.; Del Moral, C.; Rodriguez, N.; Fernandez-Gonzalez, N.; Martínez, J.M.; Lorca, I.; Amils, R. Metal tolerance of Río Tinto fungi. Front. Fungal Biol. 2024, 5, 1446674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerga, G.A.; Shibeshi, N.T.; Prabhu, S.V.; Varadharajan, V.; Yeshitla, A. Biosorption potential of Purpureocillium lilacinum biomass for chromium (VI) removal: Isolation, characterization, and significance of growth limiting factors. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2023, 66, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucconi, L.; Ripa, C.; Alianiello, F.; Benedetti, A.; Onofri, S. Lead resistance, sorption and accumulation in a Paecilomyces lilacinus strain. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2003, 37, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Pariatamby, A.; Ahmed, A.; Auta, H.S.; Hamid, F.S. Enhanced bioremediation of heavy metal contaminated landfill soil using filamentous fungi consortia: A demonstration of bioaugmentation potential. Water Air Soil Poll. 2019, 230, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian Fazli, M.; Soleimani, N.; Mehrasbi, M.; Darabian, S.; Mohammadi, J.; Ramazani, A. Highly cadmium tolerant fungi: Their tolerance and removal potential. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2015, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, S.; Prasad, R.; Yadav, P.K. Assessing the tolerance impact of fungal isolates against lead and zinc heavy metals under controlled conditions. Environ. Ecol. 2023, 41, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Padua, J.C.; dela Cruz, T.E.E. Isolation and characterization of nickel-tolerant Trichoderma strains from marine and terrestrial environments. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, B. Heavy metal tolerance of filamentous fungi isolated from metal-contaminated soil. Asian J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Environ. Sci. 2015, 17, 965–968. Available online: https://www.envirobiotechjournals.com/issues/article_abstract.php?aid=6604&iid=205&jid=1 (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Chauhan, J.; Yadav, V.K.; Sahu, A.P.; Jha, R.K.; Kaushik, P. Biosorption potential of alkali pretreated fungal biomass for the removal and detoxification of lead metal ions. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2020, 79, 636–639. Available online: https://nopr.niscpr.res.in/bitstream/123456789/54984/1/JSIR%2079%287%29%20636-639.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sule, A.M.; Inuwa, B.; Bello, S.Z.; Gero, M.; Mohammed, H.A.; Muhammad, Z.A. Isolation, characterization and heavy metals tolerance indices of indigenous fungal flora from a tannery located at Challawa Industrial Estate of Kano State, Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2022, 26, 1289–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, A.S.Y.; Choong, C.C. Bioaccumulation and biosorption efficacy of Trichoderma isolate SP2F1 in removing copper (Cu (II)) from aqueous solutions. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 25, 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Bhatia, D.; Singh, R.; Rani, S.; Bishnoi, N.R. Sorption of heavy metals from electroplating effluent using immobilized biomass Trichoderma viride in a continuous packed-bed column. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2011, 65, 1133–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.H.; Hashem, M. Removal efficiency of the heavy metals Zn (II), Pb (II) and Cd (II) by Saprolegnia delica and Trichoderma viride at different pH values and temperature degrees. Mycobiology 2007, 35, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujatha, P.; Kalarani, V.; Kumar, B.N. Effective biosorption of nickel (II) from aqueous solutions using Trichoderma viride. J. Chem. 2013, 2013, 716098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, F.; Alsarraf, M.J.; Abalkhail, T.; Stephenson, S.L. Evaluation of resistance patterns and bioremoval efficiency of hydrocarbons and heavy metals by the mycobiome of petroleum refining wastewater in Jazan with assessment of molecular typing and cytotoxicity of Scedosporium apiospermum JAZ-20. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słaba, M.; Długoński, J. Efficient Zn2+ and Pb2+ uptake by filamentous fungus Paecilomyces marquandii with engagement of metal hydrocarbonates precipitation. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2011, 65, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotlikar, N.P.; Damare, S.R.; Meena, R.M.; Linsy, P.; Mascarenhas, B. Potential of marine-derived fungi to remove hexavalent chromium pollutant from culture broth. Indian J. Microbiol. 2018, 58, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Dai, T.; Zou, P.; Bi, X.; Li, S. Screening and performance optimization of fungi for heavy metal adsorption in electrolytes. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1371877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros Júnior, L.M.; Macedo, G.R.; Duarte, M.M.L.; Silva, E.P.; Lobato, A.K.C.L. Biosorption of cadmium using the fungus Aspergillus niger. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2003, 20, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazem, M.A.; Nazareth, S. Sorption of lead and copper from an aqueous phase system by marine-derived Aspergillus species. Ann. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.M.; Saad, M.M.; Ibrahim, N.A.; El-Hadedy, D.; Ibrahim, E.I.; El-Din, A.Z.K.; Hassan, H.M. Evaluation of Aspergillus tamarii NRC 3 biomass as a biosorbent for removal and recovery of heavy metals from contaminated aqueous solutions. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2019, 43, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Zafar, S.; Ahmad, F. Heavy metal biosorption potential of Aspergillus and Rhizopus sp. isolated from wastewater treated soil. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2005, 9, 123–126. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1807/6431 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.