Abstract

Ultra-precision single-point diamond turning (SPDT) remains the core process for fabricating optical-grade surfaces with nanometric roughness and sub-micrometer form accuracy. However, machining hard-to-cut or brittle materials such as high-entropy alloys, metals, ceramics, and semiconductors is limited by severe tool wear, high cutting forces, and brittle fracture. To overcome these challenges, a new generation of non-conventional assisted and hybrid SPDT platforms has emerged, integrating multiple physical fields, including mechanical, thermal, magnetic, chemical, or cryogenic methods, into the cutting zone. This review comprehensively summarizes recent advances in hybrid non-conventional assisted SPDT platforms that combine two or more assistive techniques such as ultrasonic vibration, laser heating, magnetic fields, plasma or gas shielding, ion implantation, and cryogenic cooling. The synergistic effects of these dual-field platforms markedly enhance machinability, suppress tool wear, and extend ductile-mode cutting windows, enabling direct ultra-precision machining of previously intractable materials. Recent key case studies are analyzed in terms of material response, surface integrity, tool life, and implementation complexity. Comparative analysis shows that hybrid SPDT can significantly reduce surface roughness, extend diamond tool life, and yield optical-quality finishes on hard-to-cut materials, including ferrous alloys, composites, and crystals. This review concludes by identifying major technical challenges and outlining future directions toward optimal hybrid SPDT platforms for next-generation ultra-precision manufacturing.

1. Introduction

Advanced manufacturing encompasses the application of modern techniques and enabling technologies to enhance manufacturing processes and improve product performance. It plays a critical role in the fabrication of high-value critical components across diverse industrial sectors, particularly in applications requiring superior surface finish and dimensional precision. With the increasing relevance of nano-scale features, specialized ultra-precision machining approaches have been developed to achieve improved geometrical fidelity [1,2,3]. Ultra-precision subtractive machining methods are capable of achieving nanometer to sub-nanometer surface finishes through highly controlled material removal processes. Core technologies include ultra-precision turning, milling, and grinding, which use diamond tools or fine abrasives on ultra-stable machines to machine metals, polymers, and hard ceramics with surface roughness typically in the 1–10 nm range [3,4]. Magnetorheological finishing [5,6,7] and ion beam figuring [8,9] enable deterministic, non-contact removal of nanometers or angstroms of material, reaching sub-nanometer smoothness ideal for optics. Other advanced methods like chemical mechanical polishing, fluid jet polishing, laser polishing, plasma polishing, and magnetic abrasive finishing offer localized or contactless finishing of diverse materials, including silicon, glass, ceramics, and metals [1,10]. These techniques are essential in different critical fields, including aerospace, optics, semiconductors, and precision metrology, where extreme surface quality and form accuracy are crucial.

Ultra-precision single-point diamond turning (SPDT) is a leading machining technology in advanced manufacturing for producing optical-quality surfaces. Using a single-crystal diamond tool on precision lathes, SPDT can achieve sub-micrometer form accuracy and nanometer-level surface roughness [3,11]. This capability often eliminates the need for post-polishing, enabling direct fabrication of mirrors, lenses, critical components, and microstructures. However, SPDT faces challenges related to surface finish, tool wear, and general machinability when machining hard-to-cut materials [12,13,14]. Many factors can influence the outcome of a diamond turning process. Environmental conditions, workpiece material properties, choice of cutting parameters, machine-tool dynamics, tool geometry, chip formation behavior, material recovery effects, and passive vibrations all have a direct or indirect impact on the generated surface quality [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. As a result, achieving high-quality optical surfaces using SPDT technology requires careful control and optimization of these factors. These challenges become even more pronounced when machining difficult-to-cut or brittle materials. For example, materials like silicon, titanium alloys, stainless steel, nickel-based superalloys, and other hard composites tend to cause low surface quality, high cutting forces, and rapid diamond tool wear [23,24,25,26,27,28].

To overcome these limitations, various non-conventional assisted machining techniques have been integrated into the diamond turning process. Non-conventional assistance in SPDT refers to the use of a single energy/mechanism to support the conventional purely mechanical SPDT process. By adding external energy inputs, such as heat, active vibration, magnetic fields, or cooling gases, to the cutting zone, the machinability of hard or brittle materials can be improved. Experimental studies have demonstrated that laser-assisted machining, ultrasonic vibration assistance, magnetic field application, and cryogenic or plasma jet cooling can all improve the surface finish of the turned workpiece and extend the life of the diamond tool [29,30,31]. Hybrid SPDT is a machining approach that simultaneously integrates two or more non-conventional assistance techniques with diamond turning, combining multiple mechanisms within a single operation. For example, a laser-assisted diamond turning process can be supplemented with ultrasonic vibration to intermittently separate the tool from the workpiece, thereby reducing heat build-up and tool wear. By independently controlling several energy-based assistance methods at once, hybrid SPDT systems can achieve synergies that significantly enhance performance. These benefits may include higher material removal rates, longer tool life, finer surface roughness, and improved dimensional accuracy compared to conventional SPDT [30,32,33,34].

This review consolidates and evaluates the most recent developments in hybrid non-conventional assisted SPDT technologies, clarifying the specific gaps it fills relative to prior surveys. This work provides an integrated synthesis of the physical principles, implementation strategies, and performance characteristics of newly developed hybrid SPDT platforms. By comparing the effectiveness of these hybrid approaches and assessing their applicability to emerging engineering materials, this review highlights the gap between current capabilities and the requirements of an ideal hybrid SPDT platform. This analysis identifies key opportunities, unresolved technical challenges, and the essential features needed for next-generation hybrid SPDT platforms, thereby offering a roadmap for future research and development.

The structure of this review is as follows. Section 2 offers a concise introduction to non-conventional assistance techniques and their influence on the SPDT process. Section 3 presents and discusses the most recent hybrid SPDT platforms derived from these methods. Section 4 outlines future research directions toward the development of an ideal hybrid SPDT system, followed by concluding insights in Section 5.

2. Non-Conventional Assistance Techniques

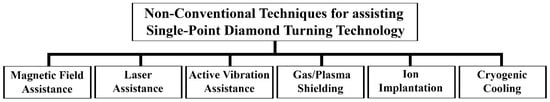

Figure 1 presents developed non-conventional techniques for assisting the SPDT process. In the following subsections, each technique and its effects on the SPDT process are introduced and discussed.

Figure 1.

Non-conventional technologies assisted ultra-precision SPDT technology.

2.1. Magnetic Field Assistance

Magnetic-field-assisted SPDT stabilizes chip formation and tool–work interactions by increasing dislocation mobility, reducing friction, and providing passive damping. When this technique is assisting the diamond cutting process, the magnetic field induces eddy currents in conductive workpieces, generating Lorentz forces that act as passive damping to suppress self-excited vibrations and chatter and yielding smoother, more uniform diamond tool engagement with the workpiece. This technique can enhance thermal conductivity and reduce cutting temperature and diamond tool wear. It can also generate a damping effect, which can reduce chatter and vibrations during the diamond cutting process. All these effects result in improved surface roughness and integrity while enabling the cutting of hard-to-cut materials and optical metals in dry cutting conditions [35,36,37,38,39].

Experiments report roughness reductions typically in the 30–60% range, for example, an improvement of ~62.5% on Ti–6Al–4V in dry cutting conditions, and improvements in materials like single-crystal Cu. Magnetic-field-assisted SPDT also lowers residual stresses and can improve fatigue life and form accuracy in titanium alloys at low fields in the range of 0.01–0.05 T [37,38,40]. While average cutting force may increase due to magnetic drag, force fluctuations and thrust ratios often decrease, benefiting tool life and stability [38]. The method is contactless, low-cost, retrofit-friendly, and supports green, coolant-free machining, but its effectiveness depends on electrical conductivity and magnetic susceptibility [35,36,37,41,42]. The application of magnetic field assistance during SPDT spans optics, aerospace, and biomedical implants, where machining hard-to-cut materials with a high surface finish and minimum surface roughness is required [36,37,38,41].

Paramagnetic materials such as titanium, copper, and nickel alloys benefit most from this technique; insulating ceramics and polymers experience negligible effects. Magnetic assistance has recently been combined with other methods, such as ultrasonic vibration and laser heating, to maximize benefits and enable the best possible machining conditions. As research efforts continue, one can envision hybrid systems where magnetic assistance plays a key role in achieving the next level of precision and efficiency in manufacturing the advanced components of the future. In recent years, substantial achievements have been made in understanding and using magnetic fields in SPDT, yet ongoing research continues to refine the technique. Challenges like optimal field tuning, integration for ferromagnetic materials, and synergy with other assist methods are actively being addressed. The technique is relatively low-cost and easy to implement, making it attractive for ultra-precision manufacturing industries. In summary, magnetic-assisted SPDT emerges from the recent literature as a powerful, green, and versatile approach to push the boundaries of machining accuracy and material machinability.

2.2. Laser Assistance

Laser-assisted machining has shown significant potential in enhancing the SPDT process by heating and softening the workpiece material, which improves the machinability of hard and brittle materials. This technique reduces cutting forces, tool wear, built-up edge formation, and the friction coefficient, thereby extending tool life and improving process efficiency. It also facilitates ductile regime cutting, leading to better chip formation, improved surface quality, and reduced risks of microcracking and subsurface damage. However, the use of laser assistance can also increase cutting temperature, which may negatively affect the optical surface quality if not properly controlled [29,31].

Recent implementations of laser-assisted single-point diamond turning have demonstrated wide applicability across semiconductors, optical glasses, hard ceramics, metals, composites, and advanced alloys by enabling localized ductile-mode cutting, lowering forces, and improving surface finish and tool life. Single-crystal silicon has been successfully machined with laser assistance to produce ductile removal and optical-quality surfaces [43,44]. In addition, µ-laser configurations enable highly localized preheating and fine control for microfeature and surface quality improvements [45,46]. In situ laser strategies have turned brittle silicon into ductile, cuttable material for high-precision components [47]. In situ laser-assisted SPDT has enabled ductile machining of fused silica for optical aspheres and freeform optics [48,49].

Germanium, including Ge(111), has been processed in situ in laser-assisted SPDT to produce infrared optics with excellent finishes [50,51]. Also, binderless tungsten carbide has repeatedly shown benefits; binderless WC turning attains mirror-quality surfaces, with a surface roughness of Ra < 50 nanometers, and large reductions in tool wear across in situ, in-process, and in-heat laser-assisted SPDT studies [52,53,54]. High-entropy alloys (HEAs) and multi-component alloys such as CoCrFeMnNi have been rendered more machinable with in situ laser assistance, reducing cutting forces and improving subsurface integrity [55], while metal–matrix composites (SiCp/Al) have benefited from in situ laser-assisted SPDT to minimize brittle fracture and achieve smoother finishes [56]. Ferroelectric and piezoelectric crystals (PMN-PT) have been successfully ductile-machined using laser-assisted SPDT methods to produce functional optical/electromechanical surfaces [57], and crystallized Ni–P mold cores have been finished in situ to meet mold fidelity requirements for precision replication [58].

Across these studies, advances such as synchronized (in-process) laser timing, adaptive control to compensate thermal growth, and tailored laser wavelengths/pulse regimes, including adaptive laser-assisted SPDT of silicon, have been critical to preserve form accuracy while reaping thermal-softening benefits [59]; collectively, these works show laser-assisted SPDT’s versatility in expanding the material envelope of ultra-precision SPDT when laser parameters, delivery geometry, and thermal management are carefully matched to the workpiece and diamond cutting conditions.

2.3. Active Vibration Assistance

Vibration-assisted SPDT, particularly through ultrasonic and elliptical vibration systems, provides considerable advantages in machining performance. It decreases tool wear by up to 58% and reduces friction forces by as much as 84%, which significantly improves diamond tool life. This technique enables effective machining of ferrous and brittle materials while achieving optical surface quality with roughness below 5 nm. Moreover, it reduces cutting forces, stress on the diamond tool, and chemical wear while enhancing surface roughness, wettability, and overall machining performance. Elliptical or two-dimensional vibration further improves surface wettability, wear resistance, and even self-cleaning properties [29,31].

Despite these advantages, vibration assistance may also induce unwanted machine-tool vibrations, and its full range of side effects remains insufficiently understood, requiring further investigation. Practical challenges remain for industrial adoption: designing transducer assemblies that withstand sustained cutting loads without degrading amplitude or frequency, developing robust rotary power transfer for spindle-integrated systems, ensuring automatic frequency tracking to maintain resonance under changing boundary conditions, and protecting electronics and sensors from the machining environment. Excessive amplitude or poor matching of feed/speed can collapse intermittent separation (especially at high cutting speeds) or create pits and waviness; therefore, careful process planning and closed-loop control are essential. Priority research needs include high-power, reliable 2D/3D actuators and rotary transfer solutions, predictive models for subsurface damage under intermittent cutting, and fully industrialized hybrid platforms (active vibration combined with laser or magnetic processes) to translate laboratory benefits into production-scale gains [29,60].

Recent advances in vibration-assisted SPDT demonstrate broad material coverage and practical benefits across freeform optics, steels, superalloys, HEAs, carbides, semiconductors, and microtexturing and microstructure applications [61,62]. Tool-path optimization for independently controlled fast-tool-servo SPDT has been combined with ultrasonic and vibration strategies to improve form accuracy and machining efficiency for freeform optics [63], and ultrasonic-assisted slow tool servo SPDT has enabled high-precision freeform and mold surfaces on die steel, with improved surface finish and reduced subsurface damage [64]. Ultrasonic vibration has been applied to HEAs (FeCrCoMnNi), where high-frequency ultrasonic assistance suppresses tool wear and enables ductile-regime removal and improved surface integrity in cutting difficult-to-cut HEAs [65]. Feasibility studies on tungsten carbide show that ultrasonic assistance mitigates wear and can produce mirror-like finishes when parameters are tuned, pointing to viable routes for machining binderless WC with extended tool life [66]. More generally, ultrasonic vibration assistance to diamond cutting of HEAs has reduced cutting forces and improved surface/subsurface quality compared with conventional SPDT [67].

High-frequency ultrasonic diamond turning has also been extended to hardened stainless steels, allowing ultraprecision finishes on materials previously thought unsuitable for diamond tools by lowering average cutting forces and suppressing adhesion-related wear [68]. For brittle semiconductors such as silicon, ultrasonic-assisted SPDT has been shown to operate in a ductile–brittle coupled regime, increasing the allowable cutting parameters for crack-free surfaces and informing models that predict when ductile removal is sustained [69]. Vibration-assisted end-fly diamond cutting and 3D/elliptical vibration strategies have been used to generate hierarchical microgroove and microlens surfaces with controlled texture and improved functional performance, enabling the fast fabrication of structured optics and microtextured surfaces [70].

Finally, double-frequency (dual-excitation) vibration cutting combines high-frequency ultrasonic benefits with lower-frequency profile generation to machine hardened steels and other hard-to-cut materials with better form accuracy and less tool wear, an approach that bridges freeform generation and enhanced machinability [71]. Collectively, these studies show that careful selection of the vibration mode (longitudinal, torsional, and elliptical) and frequency/amplitude and integration with tool-path control (fast- and slow-tool servo) can open new machining windows across a wide range of advanced materials, reduce tool wear, and enable functional surface texturing while maintaining form accuracy.

2.4. Gas/Plasma Shielding Assistance

Gas and plasma shielding modify the cutting-zone chemistry and convective environment to suppress oxidation, reduce chemical wear, and refresh protective surface films. These techniques can improve the machinability of the workpiece while enhancing tool life and reducing chemical affinity between the diamond and workpiece. Inert gases (N2 and Ar) exclude oxygen and limit oxidation of reactive metals, improving chip flow and reducing adhesion; reactive gases can form transient surface films that alter tool–work interactions. Controlled low-pressure O2 can form passivating oxides that reduce metal-catalyzed diamond graphitization. Also, cold-plasma jets (atmospheric and near-room-temperature plasmas) provide active species that both cool and chemically passivate freshly exposed metal surfaces; nitrogen cold-plasma jets promote rapid nitride/complex formation that raises the effective graphitization temperature at the diamond–metal interface and substantially reduces flank wear, mainly by chemical passivation rather than topographic change. Typical cold-plasma implementations use a slim capillary/nozzle with millimeter standoff and tuned discharge/flow so the jet bathes the rake face without disturbing chip evacuation; the reported results include reduced flank wear, lower cutting temperatures, and preserved or improved optical surface finishes [29,72,73,74,75,76,77,78].

Oxygen shielding presents a nuanced chemistry: Concentrated O2 supplied locally can accelerate the formation of native oxides that passivate freshly exposed metal surfaces and, counterintuitively, reduce diamond flank wear in some alloys [79,80]. In a recent study [81], researchers isolated oxygen’s role by comparing O2, air, and Ar shielding on hardened stainless steel and found that oxygen shielding lowered flank-wear rates relative to inert gases; element-specific responses emerged (Cr, Fe, and W behaved differently), implying that oxide growth kinetics and composition control the net effect on chemical wear. This chemistry-first perspective provides an actionable lever to stabilize diamond cutting of oxygen-active metals.

Despite clear benefits, cryogenic and gas/plasma assists have practical limits: added system complexity (cryogen supply, plumbing, power, and gas handling), sensitivity to nozzle alignment and flow, potential thermal-shock or dimensional effects, and the need for robust in situ diagnostics and thermal/chemical control strategies. For polymers and some workpieces, the process window shifts and must be re-optimized; long-run behavior (tool wear evolution, residual stress, and chip formation under sustained cryogenic or plasma exposure) often remains under-characterized. Nevertheless, when carefully engineered and combined with auxiliary assists (ultrasonic, magnetic, and laser), cryogenic cooling and gas/plasma shielding offer powerful, complementary routes to extend SPDT to temperature- and chemistry-sensitive materials while improving tool life, surface integrity, and process sustainability.

2.5. Ion Implantation for Tool/Workpiece Modification

Ion implantation and related surface-modification techniques tailor near-surface chemistry and microstructure to control hardness, ductility, friction, and tribochemistry at the tool–work interface, thereby expanding the material envelope accessible to SPDT. By accelerating selected ions—commonly N, B, C, H, Ga, Cu, and He—into a target surface at energies typically from tens to a few hundred keV, thin modified layers, in a range of tens to hundreds of nanometers, are produced that can increase hardness and fracture toughness, lower friction, or create graded/amorphous bands that promote ductile removal in otherwise brittle ceramics and semiconductors. Because implantation is performed in a vacuum and often requires post-implant annealing to stabilize the layer, it adds cost and processing steps and is, therefore, most attractive for high-value components or precision tool engineering [29,31].

On the tool side, focused-ion-beam (FIB) and related ion-modification techniques can enhance diamond cutting tools by altering surface chemistry and energy, reducing adhesion, friction, and graphitization. Ga+ FIB modification of single-crystal diamond creates thin altered layers (~10–50 nm) that lower forces, stabilize cutting, slow edge wear, and improve surface finish in Al6061 turning, provided that doses stay below amorphization thresholds. Practical demonstrations confirm benefits such as reduced cutting forces, lower temperatures, slower flank wear, and better surface quality, with improvements linked to surface wettability changes and sp2 enrichment [82,83,84].

On the workpiece side, ion implantation can enhance the machinability of hard, brittle workpieces by widening the ductile-removal window and reducing subsurface damage. In SiC, hydrogen implantation lowers dislocation activity, cutting stresses, and abrasive wear, promoting a more ductile cutting response. In silicon, effects are dose-dependent: low doses worsen machinability by reducing critical depth and promoting cleavage, while higher doses can suppress cleavage, increase critical depth, and reduce cutting forces, showing that outcomes depend on dose and crystallography [85,86].

Multi-ion implantation strategies create stratified subsurface architectures, including a near-surface amorphous Cu-rich band, a He-modified intermediate zone, and a deeper H-modified region, that combine crack-arresting behavior with defect-engineering to extend the brittle–ductile transition depth. For germanium, a Cu2+/He2+/H+ multi-implant produced a layered microstructure, doubled the ductile-removal depth, reduced subsurface damage, and enabled crack-free, high-throughput microlens array diamond turning at higher feeds while preserving optical finish [87].

Ion implantation not only offers benefits but also poses significant risks and limitations. On tools, improper dosing or energy can damage sp3 bonding and cause graphitic/amorphous layers, residual defects after annealing, and uneven damage that accelerates failure. On workpieces, low doses may increase brittleness, cutting resistance, anisotropy, and persistent defects that reduce the ductile cutting range. While strategies such as thermal annealing, etching, off-axis implantation, and tightly controlled process windows can mitigate these issues, they also add complexity and cost. These drawbacks and remedies have been well documented in comparative studies [88].

In summary, ion implantation and advanced surface modification techniques can enhance SPDT by expanding the ductile cutting window, reducing forces and wear, and improving throughput and surface quality in ultra-hard or brittle materials. However, high equipment costs, sensitivity to process variations, and reliance on post-treatments limit widespread industrial adoption.

2.6. Cryogenic Cooling Assistance

Temperature and chemical-environment control are powerful levers in SPDT. Cryogenic cooling, most commonly liquid nitrogen, LN2, rapidly removes heat from the tool–chip interface and suppresses thermally driven wear and tool softening. LN2 is typically delivered through capillaries or nozzles aimed at the rake/flank faces; liquid CO2 offers alternative cooling modes with different heat-capacity and flow properties and can be combined with minimal-quantity lubrication (cry0-MQL) to provide both cooling and lubrication. Cryogenic approaches are applied both in-process (jets/sprays and indirect conductive cooling) and as a pre-/post-cryo-processing treatment of tools to extend life, and they have been reported to slow wear, improve dimensional accuracy, improve chip control, and reduce friction at the tool–chip interface compared with dry or emulsion cutting. These advantages also carry environmental and operational benefits because LN2 flashes off and removes fluid recirculation/disposal burdens [89,90].

Cryogenic strategies also enable temperature-state control in polymers and other temperature-sensitive materials. Maintaining polymer workpieces below their glass transition temperature (Tg) shifts them into a glassy, high-modulus state that reduces elastic recovery and shape errors, making the optical-grade machining of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA), polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), and similar materials feasible [91,92,93,94]. In a recent study [95], the machinability and surface properties of PMMA during SPDT under cryogenic cooling are investigated for the first time. Using liquid nitrogen to cool PMMA to 0 °C, the authors found that hardness and Young’s modulus increased by 37% and 22%, respectively, compared to room temperature, leading to significant improvements in surface quality. Optimal machining parameters determined through Taguchi analysis showed that cryogenic SPDT achieved a surface roughness of 6 nm and form accuracy of 124 nm compared to 11 nm and 291 nm at room temperature. Dynamic mechanical analysis confirmed that reduced viscoelastic relaxation at low temperatures suppressed plastic side flow, thereby enhancing dimensional accuracy. Overall, the results demonstrate that cryogenic cooling effectively improves machinability and optical surface finish of PMMA in SPDT, opening new avenues for ultra-precision polymer machining.

2.7. Summary

Advanced assistive techniques are increasingly applied in SPDT to reduce tool wear, lower cutting forces, and enable ductile machining of hard-to-cut and brittle materials. Magnetic field assistance uses Lorentz-force damping or magnetophoretic effects to suppress chatter and enhance surface quality. Laser-assisted SPDT locally heats the workpiece, reducing yield strength and fracture toughness, which promotes ductile cutting and decreases tool wear. Vibration-assisted SPDT introduces high-frequency vibrations to the tool or workpiece, lowering cutting forces and achieving optical-grade surface finishes. Cryogenic cooling helps control workpiece temperature, limiting thermal damage and, in some cases, enhancing ductility. Gas/plasma shielding employs inert gases or plasma jets to prevent oxidation and chemical wear while improving surface integrity. Ion implantation and surface modification adjust the hardness and chemical properties of either the workpiece or diamond tool, improving machinability and extending tool life. Table 1 summarizes and compares the effects of these non-conventional assistance techniques on SPDT performance.

Table 1.

Non-conventional techniques for assisting SPDT.

Ultra-precision SPDT yields surfaces with nanometer-scale smoothness, necessitating advanced surface metrology tools for quality assessment and surface roughness measurement. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) plays a vital role in this context, offering sub-nanometer vertical resolution and 3D topographical mapping through nanoscale probe scanning, enabling the detection of minute surface defects and precise roughness characterization. Despite its high resolution, AFM is limited by slow scanning speed and small measurement areas [96,97]. Complementary technologies include scanning electron microscope (SEM), stylus profilometry (contact-based tracing), optical interferometry and white light interferometry (non-contact methods for form and roughness evaluation), laser scanning confocal microscopy (3D optical profiling), and laser triangulation sensors (non-contact profiling suitable for rougher surfaces), collectively providing a versatile toolkit for ultra-precision surface measurement [4,98,99,100]. These techniques are frequently employed in the surface assessment of diamond-turned products, which is why they are highlighted here to support a clearer understanding of the discussed and reviewed works.

3. Hybrid SPDT Platforms

Hybrid SPDT integrates multiple non-conventional machining techniques, each governed by different physical principles, into a single diamond cutting process. These methods operate independently but are applied simultaneously at the cutting zone, enabling interactions between the tool edge and workpiece surface. While individual assisting techniques such as magnetic field, active vibration, laser, or gas/plasma shielding have proven effective in improving machinability, reducing cutting forces, or extending diamond tool life, they may also introduce harmful effects. For instance, active vibration assistance can unintentionally cause chatter, and laser assistance, despite lowering cutting forces and enhancing tool performance, increases cutting temperatures that accelerate diamond tool wear.

To overcome these limitations, hybrid SPDT employs secondary assisting techniques to balance the benefits and drawbacks of different methods. For example, combining ultrasonic assistance with a magnetic field can suppress machine-tool vibrations and enhance surface profile accuracy, while integrating magnetic fields with laser-assisted SPDT improves thermal conductivity, reduces cutting temperature, and minimizes material deformation during solidification. Additional techniques, such as nitrogen cold plasma jets or gas shielding, further help reduce chemical tool wear. By leveraging hybrid platforms, specialized tooling, on-machine metrology, process modelling, and advanced control systems, hybrid SPDT offers significant advantages, including higher feed rates, longer tool life, optical-grade surface finishes, and superior dimensional accuracy. Recently, different hybrid SPDT platforms have been developed and applied for machining various materials. Following this, the most recent hybrid SPDT platforms are presented and discussed.

3.1. Active VibrationImplantation Assisted SPDT

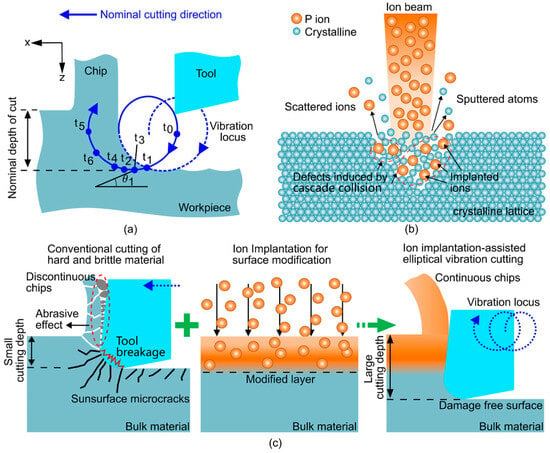

Recent investigations have introduced a hybrid machining approach known as ion-implantation-assisted elliptical vibration cutting (Ii-EVC), which enables the transition of sapphire from brittle to stable ductile removal under practical machining conditions. In this method, optically transparent sapphire single crystals with a C-plane orientation are first modified through phosphorus ion implantation, forming a surface layer with altered microstructural characteristics. Figure 2 presents the experimental setup of the developed hybrid platform, illustrating how surface modification by ion implantation, together with the EVC trajectory, mitigates diamond–workpiece collisions that typically lead to tool failure and subsurface damage, enabling ductile-mode machining at greater depths and with reduced material damage. Detailed analyses using Raman spectroscopy, transmission electron microscopy, and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy reveal that this implanted layer consists of an amorphous–nanocrystalline mixture enriched with dense crystal defects such as dislocations, twins, and stacking faults. These defects weaken atomic bonding and enhance ductility while preserving the underlying lattice integrity [101].

Figure 2.

Schematic of the ion implantation-assisted elliptical vibration cutting (Ii-EVC). (a) Elliptical vibration cutting (EVC). (b) Ion implantation process. (c) Hybrid Ii-EVC process [101].

When this pre-conditioned sapphire is subjected to ultrasonic elliptical vibration cutting, the process exhibits a significant enhancement in ductile-mode machinability. The hybrid method leads to smoother surfaces with sparse and isolated defects, reduced cutting forces, and a clear transition in chip morphology from cracked fragments to continuous lamellae. The wear of the diamond tool is markedly diminished, indicating the technique’s efficiency in mitigating tool degradation during prolonged machining. Experimental results confirm the practical advantages of Ii-EVC, showing a predominance of ductile-cut regions, superior surface integrity, and high optical transmittance in the finished sapphire components. Importantly, ion implantation alone causes only a minimal reduction in transmittance, suggesting that the process remains compatible with optical applications. Molecular dynamics simulations support these findings, illustrating that implantation-induced defects localize plastic deformation, dissipate stress concentrations, and transform potential cracks into removable surface damage. The simulations also indicate the formation of a thin amorphous surface layer over a largely undistorted crystalline substrate.

Overall, the Ii-EVC technique synergistically combines the softening effects of ion implantation with the intermittent cutting dynamics of elliptical vibration. This integration broadens the ductile machining window by increasing the ductile–brittle transition depth up to 500%, suppresses crack propagation, enhances surface finish, and significantly prolongs diamond tool life. These improvements are supported by a >10% reduction in hardness and Young’s modulus and an increase of up to 15% in plastic deformation capability, enabling more stable ultra-precision machining of hard, brittle optical materials such as single-crystal sapphire.

3.2. Active Vibration–Magnetic Field Assisted SPDT

To date, ultrasonic–magnetic field assisted SPDT has been experimentally demonstrated primarily on hard-to-cut metallic materials, notably HEAs and titanium alloys, due to their strong work-hardening behavior, high cutting forces, and severe tool–workpiece interaction in conventional purely mechanical diamond turning. Although no studies have yet reported the application of this hybrid technique to other workpiece materials, the underlying mechanisms suggest significant potential for extension to other difficult-to-machine conductive materials.

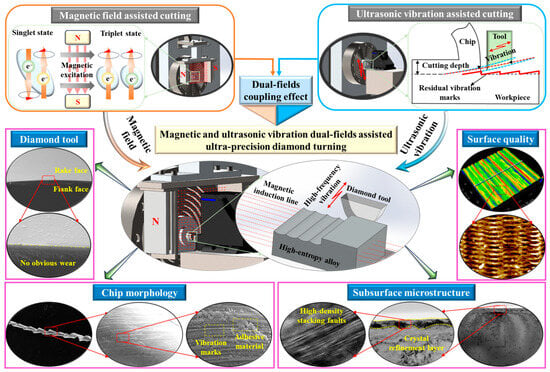

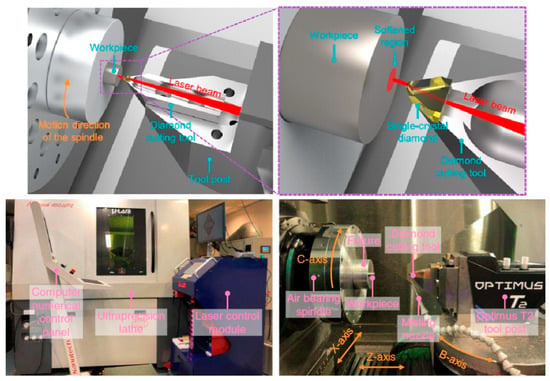

3.2.1. Ultrasonic–Magnetic Field Assisted SPDT of HEAs

HEAs present significant challenges for ultra-precision SPDT due to their strong work hardening, chemical affinity with diamond, and tendency to induce subsurface damage. Recent advances highlight ultrasonic vibration–magnetic-field dual-field assisted diamond cutting (MUVFDC) as an effective hybrid approach to overcome these limitations. Comparative studies against no-field, magnetic-only, and ultrasonic-only diamond cutting demonstrate that MUVFDC consistently achieves the lowest surface roughness, the most uniform chip morphology, minimal tool wear, and superior subsurface integrity [42]. The synergistic enhancement arises from the complementary mechanisms of the two fields: Ultrasonic vibration introduces high-frequency intermittent tool-workpiece contact that reduces average cutting forces and temperature, suppresses continuous ploughing, and stabilizes chip segmentation; simultaneously, the magnetic field induces magneto-plasticity and eddy-current damping, reducing chatter, moderating adhesive and thermal wear, and refining grain deformation beneath the machined surface [42,60,102].

Experimental validation on FeCoNiCrMn HEA confirms these effects [42]. As illustrated in Figure 3, in a controlled five-axis ultra-precision SPDT platform, MUVFDC outperformed conventional and single-field cutting under identical parameters. Surface roughness (Sa) significantly improved, from approximately 76 nm in conventional cutting to 3 nm (≈96% reduction), with subsurface roughness (Sz) reduced from 1583 nm to 70 nm. SEM and AFM surface characterization revealed elimination of tearing, pits, and vibration-induced scratches observed in single-field modes, while chip morphology transitioned from cracked, semi-continuous fragments to smooth, coiled, plastic-flow chips. Tool wear analysis showed that ultrasonic assistance alone curtailed wear but retained local built-up edges, whereas MUVFDC nearly eliminated adhesion and maintained a sharp cutting edge, demonstrating a strong synergy in prolonging diamond tool life.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of magnetic and ultrasonic vibration dual-field assisted diamond cutting (MUVFDC) for ultra-precision machining of HEAs [42].

Ultrasonic-assisted SPDT of HEAs demonstrates lower cutting forces, reduced tool wear, and improved surface finish on FeCrCoMnNi substrates, achieving a surface roughness reduction of approximately 85% compared to conventional purely mechanical SPDT. Additionally, magnetic-field-assisted machining can exploit magnetophoretic and magneto-plastic effects to organize surface nanotextures and enhance material plasticity, contributing to a surface roughness reduction of about 50% relative to conventional diamond cutting. Overall, MUVFDC integrates vibration-induced stability with magnetic-field-driven material softening, resulting in up to 96% improvement in surface roughness and an ≈81% reduction in residual vibration-mark height, thereby breaking the performance limits of single-field methods and offering a promising route for achieving optical-grade surfaces on HEAs [42,60].

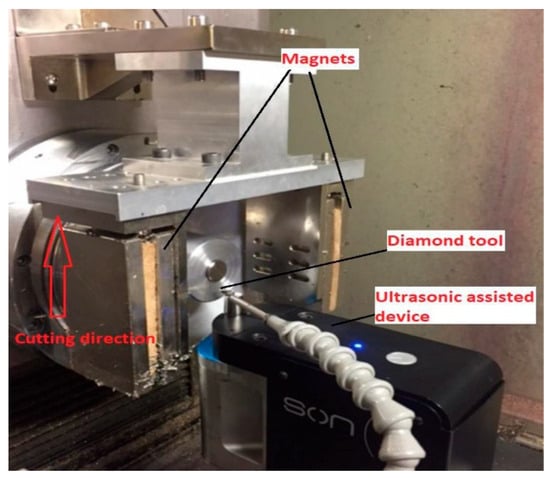

3.2.2. Ultrasonic–Magnetic Field Assisted SPDT of Titanium Alloys

A recent study used hybrid ultrasonic vibration–magnetic field assisted SPDT for cutting titanium alloys [102]. Ultrasonic-assisted machining improves cooling/lubrication at the tool–workpiece interface but leaves cyclic cutting scars and edge burrs that limit form accuracy on titanium alloys. This study superimposes a magnetic field onto the ultrasonic vibration system to suppress those defects during straight-groove cutting on Ti-6Al-4V. In an ultra-precision SPDT platform, three modes were compared: conventional diamond cutting, ultrasonic assistance only, and ultrasonic-magnetic field assistance. The developed hybrid SPDT platform is illustrated in Figure 4. The ultrasonic tool vibrated parallel to the cutting at 80 kHz with 1.25 µm amplitude. A 0.02 T field from two permanent magnets was applied; profiles were measured, and surface/edges examined. The hybrid mechanism leverages magnetophoresis: metallic constituents in the alloy migrate and align under the field, forming short, conductive chains that enhance interfacial heat transfer and suppress elastic material recovery during tool marking.

Figure 4.

Experimental setup of ultrasonic–magnetic field assisted SPDT [102].

The results show clear advantages of the ultrasonic–magnetic field assisted SPDT of titanium alloys over the ultrasonic-assisted sample and the normal diamond cut sample. Three-dimensional topographies reveal minimized cutting marks in ultrasonic–magnetic field assisted samples and linear metallic traces parallel to the field, which is direct evidence of magnetic particle migration; normal diamond cut sample surfaces exhibit pronounced waviness and material swelling, while the ultrasonic-assisted sample adds aggregated vibration-cycle scars. SEM confirms that ultrasonic–magnetic field assisted SPDT significantly reduces the size and areal coverage of scars compared with other implemented machining techniques; groove edges are cleaner with negligible burr formation. Surface profiles in the ultrasonic–magnetic field assisted sample closely match the tool form, eliminating the ragged marks seen in other samples. Quantitatively, the groove depth error is reduced from 757.14% (normal cutting) and 114.29% (ultrasonic-assisted) to as low as 1.69%, representing a ~96–99% improvement, while groove width error decreases from 22.66% and 5.02% to 1.77%, corresponding to a ~65–92% improvement. Overall, coupling a 0.02 T magnetic field with ultrasonic cutting mitigates the ultrasonic assistance’s intrinsic scarring/burr drawbacks and yields smoother surfaces and near-nominal groove geometry in Ti-6Al-4V. This method is an effective pathway to improve ultra-precision surface finish quality on difficult-to-cut materials, including titanium alloys.

3.3. Active Vibration–Laser-Assisted SPDT

Hybrid ultrasonic–laser-assisted SPDT has thus far been applied mainly to brittle and hard-to-cut materials such as single-crystal silicon, SiCp/Al composites, and selected metallic alloys, where thermal softening and vibration-induced intermittent cutting jointly promote ductile-mode material removal. The applicability of this technique is currently constrained by thermal management requirements and material-specific laser absorption characteristics; nevertheless, with appropriate parameter control, the approach shows strong potential for broader application to other brittle and composite materials.

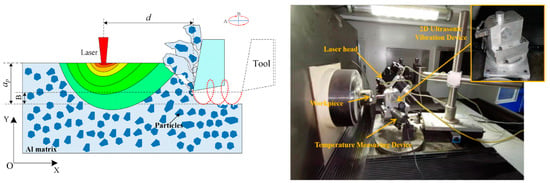

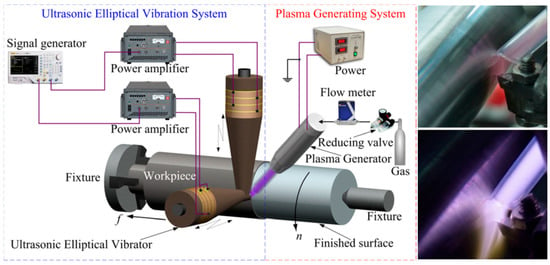

3.3.1. Ultrasonic–Laser-Assisted SPDT of SiCp/Al Composites

A recent study [103] combines laser with elliptical ultrasonic vibration to enhance the machinability of a 60 vol% SiCp/Al composite and explains the underlying deformation and surface formation mechanisms via a microstructure-resolved finite element method (FEM) validated by cutting trials. As shown in Figure 5, a Gaussian laser source and 28 kHz tool vibration reproduce an ultrasonic vibration-laser assisted SPDT platform, where laser preheating softens the Al matrix ahead of the tool and elliptical ultrasonic vibration enables intermittent cutting, jointly improving machinability. The experimental results show that laser softening weakens matrix support for SiC particles, enabling their shear-plane redistribution; dominant damage modes are particle fracture, particle–matrix interfacial debonding, and crack propagation along the shear plane. Ultrasonic vibration induces intermittent contact, promoting serrated, discontinuous chips and easing chip separation. Intermittent cutting also decreases cutting temperature and extends diamond tool life. The tool–particle relative position governs local outcomes, including deflection, fracture, or debonding. Compared with conventional SPDT, ultrasonic vibration–laser-assisted SPDT improves surface integrity: fewer pits and cracks, less particle breakage, and matrix coating that partially seals defects, accompanied by a surface roughness reduction of approximately 50%. Overall, the FEM and experiments are in close agreement, and ultrasonic vibration-laser assisted SPDT is validated as an efficient route to machine high-volume-fraction SiCp/Al with superior surface quality.

Figure 5.

Experimental setup and schematic diagram of laser–ultrasonic-vibration-assisted machining (A: amplitude in the X direction; B: amplitude in the Y direction; d: distance between the tool and the center of the laser; ap: the cutting depth) [103].

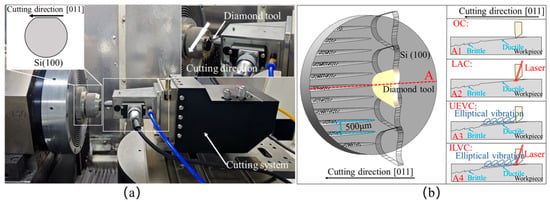

3.3.2. Ultrasonic–Laser-Assisted SPDT of Single-Crystal Silicon

A recent experimental investigation [104] validates an in situ hybrid vibration–laser-assisted SPDT system that combines ultrasonic elliptical vibration cutting with a 1064 nm laser to shift silicon removal from brittle to ductile mode and suppress subsurface damage. The authors benchmark ordinary cutting, laser-assisted SPDT, ultrasonic-assisted SPDT, and the hybrid ultrasonic–laser-assisted SPDT across groove tests, microlens fabrication, and sine-wave surface generation. The experimental setup of the developed hybrid platform is illustrated in Figure 6. It can be seen that in grooving, conventional normal SPDT shows a shallow brittle-to-ductile transition depth (DBT) of 99.1 nm; laser-assisted SPDT at 3 W raises DBT to 280.5 nm (+283%), while ultrasonic-assisted SPDT alone reaches 342.7 nm. Critically, hybrid ultrasonic-laser assisted SPDT at 3 W attains DBT = 1075 nm, whereas 4 W overheats and degrades the surface via thermal cracking. Hybrid ultrasonic–laser-assisted SPDT also enables one-pass, 1 µm high microlenses with smooth surfaces, while other techniques exhibit brittle fractures at similar depths, evidencing the larger safe process window under the hybrid field.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of grooving experiments: (a) experimental setup; (b) cutting process diagram with four different cutting methods [104].

Transmission electron microscopy cross-sections further show that hybrid ultrasonic-laser assisted SPDT achieves the smallest subsurface damage depth despite a thicker lubricating amorphous-Si layer, with markedly reduced lattice distortion relative to laser- and ultrasonic-assisted SPDT techniques. Overall, the proposed hybrid method integrates beneficial heat and force fields to expand ductile-cutting limits, elevate surface integrity, and enhance process outcome for silicon micro-optics manufacturing.

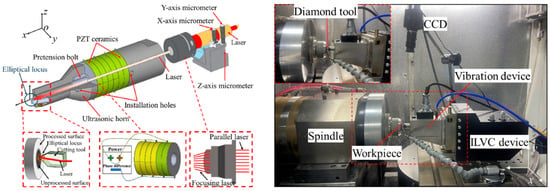

Another recent study [105] proposes and validates a hybrid ultrasonic, elliptical vibration–laser-assisted SPDT technique to rapidly machine silicon microlens arrays (MLAs) with low damage. As shown in Figure 7, a hollow ultrasonic horn lets the laser pass through the tool to locally soften Si while the diamond tool executes a high-frequency elliptical path in the cutting–depth plane; numerical analysis shows that the microlens geometry is governed by vibration amplitudes, nominal cutting speed, and tool shape and that one microlens is formed per vibration cycle. Plane cutting on Si(100) confirmed nanometric integrity (Sa ≈ 3.387 nm) with only slight tool wear (≈47.7 µm) under 35 kHz vibration, 4 µm/1 µm amplitudes (cut/depth), and 3 W laser power.

Figure 7.

Structural design of the in situ laser–vibration-assisted diamond cutting system and experimental setup of the developed laser–vibration-assisted SPDT platform [105].

Silicon MLAs were fabricated at 35 kHz using vibration amplitudes of 4 µm/1 µm and a laser power of 3 W. Increasing the cutting speed from 120 to 220 m/min enlarged the lens size and spacing, yielding microlenses of approximately 300 nm height and enabling uniform array fabrication within 3–5 s on a 25.4 mm wafer. The process achieved a throughput of ~35,000 microlenses per second with negligible additional tool wear. Overall, the hybrid ultrasonic–laser-assisted SPDT platform combines ductile-mode material removal with intermittent cutting kinematics to enable rapid fabrication of uniform silicon MLAs with low surface roughness and minimal tool degradation.

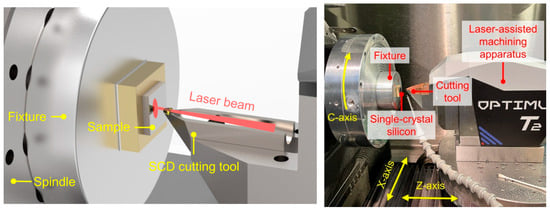

3.3.3. Laser-Assisted Slow-Tool-Servo SPDT of Single-Crystal Silicon

A recent study [106] introduced laser-assisted slow-tool-servo SPDT (LASTSDT) as a practical route to fabricate crack-free MLAs on single-crystal silicon with markedly improved surface finish over conventional slow-tool-servo-assisted SPDT. As illustrated in Figure 8, the process focuses a 1064 nm Nd:YAG beam through a U-channel single-crystal diamond tool to locally heat/soften the cutting zone while following a continuous servo toolpath, enabling complex optics with high finish at low wear. This work first quantifies machinability gains: The critical cutting depth at the ductile–brittle transition rises from 598.70 nm (no laser) to 646.92 nm under laser assistance, supporting deeper, more efficient cuts. MLAs with spherical elements are produced; measured average depth/diameter and form errors are comparable between LASTSDT and slow-tool-servo-assisted SPDT, indicating that accuracy is retained while finish improves. LASTSDT also achieved the best outcomes in terms of optical surface quality and generated surface roughness compared to the other techniques. Tool SEM and Raman spectroscopy show no appreciable tool wear or added residual stress, respectively. Molecular dynamics simulations support the mechanism, where elevated cutting temperature mitigates high-pressure phase transformation, enhances amorphous atomic flow, and suppresses elastic recovery, thereby lowering roughness. Overall, LASTSDT preserves form accuracy (depth and diameter errors within ~5%) while delivering nanoscale finishes and reducing surface roughness by 45.3% (Sa) and 60.9% (Sz) on silicon MLAs.

Figure 8.

Schematic and experimental setup of laser-assisted slow-tool-servo SPDT platform [106].

3.3.4. Laser-Assisted Slow-Tool-Servo SPDT of Titanium Alloys

Another recent study [107] introduces a hybrid ultra-precision SPDT that combines laser-assisted SPDT with slow-tool-servo kinematics to flexibly texture microstructure arrays on titanium alloys while preserving surface integrity. As shown in Figure 9, the laser locally softens the cutting zone throughout a single-crystal diamond tool with a large negative rake tracks slow-tool-servo toolpaths, enabling low-stress material removal under ultra-low feeds. The experimental setup employed ~0.87 W of laser power and ~95 RPM in spindle speed. The experimental results demonstrated two patterns: sine-shaped waves and a honeycomb array formed by spherical microlenses, both produced uniformly on titanium workpiece surfaces. The achieved surface quality was optical-grade, outperforming conventional SPDT and fast-tool-servo baselines by 79.3% and 74.5%, respectively, attributed to the combined effects of negative rake-induced hydrostatic pressure and laser-induced thermal softening. FEM indicated a 41.6% reduction in von Mises equivalent stress under hybrid heating, corroborating the observed burr suppression and smoother finish. Microstructural analyses confirmed process benignity and beneficial refinement. Overall, the hybrid laser-assisted slow-tool-servo SPDT platform route is evidencing a scalable pathway to high-accuracy, low-roughness microtextures on difficult-to-cut materials, including titanium alloys.

Figure 9.

Schematic of the working principle of the in situ laser-assisted diamond turning and experimental setup of the developed laser-assisted slow-tool-servo SPDT platform [107].

3.4. Active Vibration–Gas/Plasma Shielding Assisted SPDT

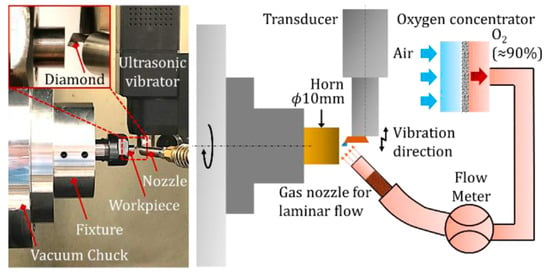

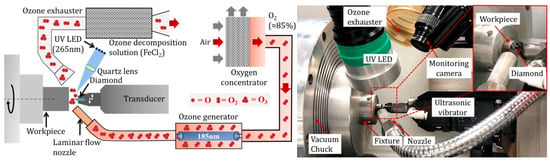

3.4.1. Ultrasonic Vibration–Oxygen-Shielded Assisted SPDT

A recent study [81] investigated and developed a hybrid SPDT approach that integrates ultrasonic vibration cutting with a concentrated oxygen shielding system to enable direct diamond machining of steels and other hard-to-cut alloys. The work explored how oxygen influences the intermittently opened tool–workpiece interface created by ultrasonic vibration, where periodic contact interruption allows ambient gases to interact with the freshly exposed metal surface. To isolate this effect, the researchers employed a controlled oxygen-shielding setup using an oxygen concentrator and a laminar nozzle without altering cutting or vibration conditions. Experiments on stainless steel demonstrated that oxygen-rich environments significantly reduced diamond wear compared with air, argon, or argon plasma, a trend consistent for diamond tools. Subsequent tests on pure Fe, Cr, and W revealed that the chromium workpiece produced the most severe wear, which increased as oxygen concentration decreased, whereas iron and tungsten workpieces showed less sensitivity but still benefited from elevated oxygen levels. Surface analyses and low-pressure oxidation experiments indicated rapid oxide formation on iron within a single 40 kHz vibration cycle, suggesting that oxygen promotes fast native-oxide growth on the freshly exposed workpiece surface during the off-contact phase. This oxide layer passivates the surface, suppressing metal-catalyzed graphitization of diamond and thereby extending tool life.

Building on these findings, the authors designed a hybrid ultrasonic vibration–oxygen-shielded assisted SPDT platform (Figure 10), in which ultrasonic vibration reduces cutting forces and tool wear by enabling intermittent cutting, while the concentrated oxygen shielding further mitigates chemical wear through interfacial modification. Overall, this study reframes the wear reduction mechanism in ultrasonic-assisted SPDT as a surface-science phenomenon governed by oxide growth kinetics and oxygen availability, offering a practical and effective route to extend diamond tool performance in machining hard-to-cut ferrous materials.

Figure 10.

Schematic and experimental setup of ultrasonic vibration–oxygen-shielded assisted SPDT [81].

3.4.2. Ultrasonic Vibration–Cold Plasma Jet Assisted SPDT

A recent research [75] proposed a combined process, ultrasonic elliptical vibration–cold plasma jet assisted SPDT, that delivers a flexible, room-temperature nitrogen cold-plasma jet directly to the tool–workpiece interface while driving the diamond tool on a precisely phased ultrasonic elliptical trajectory. The system, as depicted in Figure 11, incorporates a tube-guided plasma source operating with a high-purity nitrogen gas composition (99.999% N2) alongside a dual-channel ultrasonic actuator. This configuration allows for amplitude amplification and precise phase shifting, which can be adjusted to create either linear or elliptical tool paths. Such capabilities facilitate synchronized cutting motions, enhancing the efficiency and precision of the machining process. XPS analysis of plasma-assisted cuts on NAK80 reveals nitrogen incorporation (N1s) and formation of nitride/complex species, consistent with a transient surface nitriding that reduces Fe’s catalytic activity toward diamond graphitization. In parallel, the ultrasonic elliptical vibration periodically interrupts contact between the diamond tool and workpiece surface, reverses chip–tool friction, and allows intermittent heat release, collectively lowering cutting temperature and chemical wear.

Figure 11.

Schematic and experimental setup for hybrid ultrasonic vibration–cold plasma jet assisted SPDT [75].

The experimental results show that the combined process reduces diamond flank wear markedly relative to ordinary cutting, with wear under ultrasonic vibration–cold plasma jet assisted SPDT dropping to less than half that of conventional turning over identical cutting distance and parameters on NAK80. Meanwhile, surface finish improves versus ordinary cutting and remains comparable, indicating the plasma’s primary role is wear suppression rather than roughness modification. Overall, the hybrid integration of in situ nitrogen cold plasma and ultrasonic elliptical vibration effectively extends diamond tool life in ferrous machining, achieving > 50% reduction in flank wear, ~90% reduction in cutting force, and an ≈34% increase in the diamond graphitization threshold, while preserving optical-grade surface quality.

3.4.3. Ultrasonic Vibration–Ultraviolet-Ozone Assisted SPDT

A recent research work [108] introduces an ultraviolet–ozone-assisted ultrasonic vibration SPDT strategy to suppress chemical wear of single-crystal diamond tools when machining chemically active metals. The core idea is to exploit intermittent tool–workpiece separation in ultrasonic-assisted SPDT to drive oxidants into the interface and catalyze rapid surface oxidation; the resulting inert oxide film reduces metal-catalyzed diamond graphitization and wear. The results indicate that stronger oxidants, notably O3 and UV-generated monatomic oxygen, significantly increase oxide growth within each vibration cycle. As illustrated in Figure 12, a hybrid system was developed: 185 nm UV converts O2 to O3 upstream; a focused 265 nm UV spot at the tool tip photodissociates O3 to highly reactive O, delivered through a laminar-flow nozzle; excess ozone is neutralized in a FeCl2 scrubber. Experiments used stainless steel and high-purity tungsten workpieces on an ultra-precision Moore Nanotech 250 platform, with an ultrasonic vibration system, while the tool wear was tracked. The results show that ultraviolet–ozone-assisted ultrasonic vibration SPDT can significantly minimize wear compared to other shielding methods (O2 and O3). Overall, this study shows that enhancing interfacial oxidation during UVC substantially extends diamond tool life when machining difficult-to-cut metals, yielding greater than 67% reduction in tool wear and exceeding 70% wear reduction relative to oxygen-shielded UVC under comparable cutting conditions.

Figure 12.

Schematic and experimental setup for UV-O3-assisted ultrasonic vibration SPDT [108].

3.5. Summary

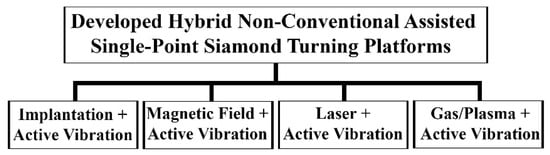

Hybrid platforms integrate two or more assisting techniques, often with real-time sensing and control, to address multiple limitations simultaneously and adapt to complex materials or geometries. Figure 13 illustrates and summarizes the developed hybrid techniques. It can be seen that in all developed hybrid non-conventional assisted SPDT platforms, active vibration is implemented in the hybrid combination while various secondary techniques assist the diamond cutting process simultaneously.

Figure 13.

Developed hybrid non-conventional assisted SPDT platforms.

Because hybrid SPDT studies target different hard-to-cut materials, direct quantitative comparison across different billet materials is not always possible; therefore, Table 2 provides a comparative synthesis of trends and mechanisms rather than absolute performance ranking. Table 2 summarizes and compares the recently developed non-conventional assisting techniques in a hybrid ultra-high-precision SPDT platform and their effects on the outcome of the SPDT process. Each hybrid SPDT combination yields measurable performance improvements, particularly in surface finish, expanded diamond tool life, and ductile cutting range. In particular, combining ultrasonic vibration with other assistance methods shows strong synergies: For example, a magnetic-assisted SPDT process with superimposed ultrasonic oscillation can significantly reduce surface roughness and extend tool life. Similarly, laser-assisted turning augmented by ultrasonic vibration achieves an optical surface finish with very low surface roughness and extends the critical brittle-to-ductile transition depth through combined thermal softening and intermittent cutting. In contrast, combinations like gas/plasma shielding and ultrasonic vibration provide useful performance gains, including extended diamond tool life, reduced cutting temperature, and cutting forces. The trend is that the largest performance gains, sub-nanometer finishes, and significantly deeper ductile cutting arise in laser- or vibration-dominated hybrids that demand complex integration.

Table 2.

Summarizing different combinations of hybrid non-conventional assisted SPDT platforms.

4. Prospects of Hybrid Non-Conventional Assisted SPDT Platforms

While hybrid SPDT shows great promise, this review highlights several gaps and challenges for further research. System integration complexity is a primary issue. Combining multiple assist mechanisms, including ultrasonics, magnets, lasers, gas shielding, and plasma jet shielding, into one platform demands precise alignment and synchronization of hardware. Many reported systems face engineering challenges such as integrating high-power actuators or lasers with tool motion, managing plasma or gas delivery, and preventing interference between subsystems. Future work must focus on modular, compact designs and robust assembly methods that can be controlled simultaneously using a high-precision hybrid controller [30,31,109]. Process stability and robustness also remain concerns. Interactions among assist fields can introduce new dynamic effects, including unwanted chatter, thermal runout, or uneven chip flow, that negatively affect form accuracy. Studies noted that excessive vibration amplitude or laser power can collapse the intermittent cutting gap or create surface waviness. To address this, advanced modelling and real-time monitoring are needed [110,111,112]. Researchers should develop predictive simulation tools for multi-field cutting and implement closed-loop control systems to maintain stable cutting conditions. Tool wear suppression continues to be a challenge, even with hybrid SPDT platforms. Although techniques like oxygen or plasma shielding effectively reduce chemical wear, the extreme cutting conditions still drive slow graphitization or microchipping of the diamond tool.

Future research should explore novel tool materials/coatings and quantify long-term wear under hybrid conditions. In addition, in situ diagnostics of tool condition (such as online wear sensing) would enable adaptive process adjustments before failure. Finally, adaptive control strategies and high-precision hybrid control systems are urgently needed for hybrid SPDT platforms. The development of hybrid controllers would enable employing and controlling different non-conventional techniques during the diamond cutting process. AI-based control systems can also optimize process conditions and tune machining parameters. There is a clear need for intelligent control frameworks that coordinate multiple assists in real time: for instance, synchronizing laser pulse timing and intensity with the instantaneous vibration phase and feed rate or modulating magnetic field strength based on measured cutting forces.

At the end, the optimal hybrid non-conventional SPDT platform would be an integrated hybrid mechanism by implementing multiple assistive techniques to benefit the SPDT process from different aspects and energy resources. There is room for developing an ideal hybrid SPDT platform that combines magnetic field, laser, and active vibration, and gas/plasma shielding techniques simultaneously. There is also a need for the development of specific high-precision hybrid control systems to control such complex manufacturing processes. The literature suggests that achieving this will require high-speed actuation, integrated sensors, and fast control algorithms. Future hybrid SPDT platforms should incorporate such adaptive controls to dynamically balance the assist effects, ensuring optimal performance and mitigating any instabilities. In summary, advancing hybrid SPDT will involve deeply understanding the combined process dynamics, enhancing tool life through material and environment control, and embedding real-time sensing/control to make these complex platforms reliable and practical for ultra-precision manufacturing. By focusing on hybrid non-conventional SPDT platforms, researchers can achieve greater process versatility, broader material applicability, and enhanced precision, driving ultra-high-precision machining toward the next generation of adaptable, efficient, and intelligent manufacturing systems.

5. Conclusions

Hybrid SPDT platforms have demonstrated that combining multiple non-conventional assists yields synergies unattainable by single methods. In practice, all reported hybrid systems incorporate active tool vibration along with one or more non-conventional techniques. These hybrid SPDT platforms significantly improve machining of hard, brittle, or heat-sensitive materials by simultaneously damping vibrations, controlling temperature/chemistry, and locally softening or reinforcing the workpiece. Across the studies, hybrid SPDT achieved markedly higher productivity and precision: feed rates were increased, diamond tool life was significantly extended, and optical-grade surface finishes and accuracy were realized even on hard-to-cut materials.

Hybrid SPDT methods combining ultrasonic vibration with magnetic, laser, cryogenic, or gas/plasma assistance significantly improved the machinability of the workpiece. These integrations produced smoother surfaces, extended tool life, expanded ductile cutting ranges, and reduced thermal and chemical wear, enabling optical-grade finishes even on hard-to-cut materials such as alloys, ceramics, and steels. Overall, the documented hybrid combinations produced substantially improved outcomes. These advances enabled the fabrication of complex optics and microtextures with optical surface roughness on hard-to-cut materials.

Despite their diverse mechanisms, the hybrid SPDT cases share common advantages. By balancing complementary physics, each hybrid platform overcame limitations of its constituent methods. Active vibration provides intermittent cutting that breaks chips and reduces force, while magnetic damping, laser softening, or gas/plasma shielding mitigate the remaining thermal or chemical complications. The result is a broad ductile cutting window, improved tool stability, and enhanced surface integrity even on alloys, composites, or crystals that normally experience brittle fracture or rapid tool wear. In summary, this state-of-the-art review finds that hybrid non-conventional assistance consistently leads to higher machining efficiency and optical-grade surface finishes compared to conventional SPDT methods. With continued interdisciplinary collaboration, hybrid non-conventional assisted SPDT platforms will play a central role in manufacturing the next generation of optical, electronic, and biomedical components.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support provided by the National Research Foundation (NRF) and the Advanced Mechatronics Technology Centre (AMTC) at Nelson Mandela University for this research. The authors also extend their sincere appreciation to Karl Du Preez (AMTC) for his valuable support of this research work. The views and conclusions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official positions of the NRF or AMTC.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yuan, J.; Lyu, B.; Hang, W.; Deng, Q. Review on the progress of ultra-precision machining technologies. Front. Mech. Eng. 2017, 12, 158–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julong, Y.; Zhiwei, W.; Donghui, W.; Binghai, L.; Yong, D. Review of the current situation of ultra-precision machining. J. Mech. Eng. 2007, 43, 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hatefi, S.; Abou-El-Hossein, K. Review of single-point diamond turning process in terms of ultra-precision optical surface roughness. The Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 106, 2167–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucca, D.A.; Klopfstein, M.J.; Riemer, O. Ultra-precision machining: Cutting with diamond tools. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2020, 142, 110817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheisari, R.; Ghasemi, A.; Jafarkarimi, M.; Mohtaram, S. Experimental studies on the ultra-precision finishing of cylindrical surfaces using magnetorheological finishing process. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2014, 2, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Li, S.; Guan, C.; Li, Y.; Hu, X. Ultra-precision optical surface fabricated by hydrodynamic effect polishing combined with magnetorheological finishing. Optik 2018, 156, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Tao, M.; Li, J.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Analysis and experimental study on influencing factors to magnetorheological finishing for ultra-precision optical mirror surfaces. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2025. OnlineFirst. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänsel, T.; Frost, F.; Nickel, A.; Schindler, T. Ultra-precision Surface Finishing by Ion Beam Techniques. Vak. Forsch. Prax. 2007, 19, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, T.; Pietag, F. Ion beam figuring machine for ultra-precision silicon spheres correction. Precis. Eng. 2015, 41, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Song, J.; Liu, X.; Lee, C.H.; Marinescu, I.D.; Hui, J.; Guo, L. Precision and ultra-precision machining with elastic polishing tools: A review. Surf. Sci. Technol. 2025, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, B.; Singh, S.; Sarepaka, R.V.; Mishra, V.; Khatri, N.; Aggarwal, V.; Nand, K.; Kumar, R. Diamond turning of optical materials: A review. Int. J. Mach. Mach. Mater. 2021, 23, 160–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, R.; Sarepaka, R.V.; Subbiah, S. Diamond Turn Machining: Theory and Practice; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brinksmeier, E.; Gläbe, R.; Schönemann, L. Review on diamond-machining processes for the generation of functional surface structures. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2012, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Cheng, K. Micro/nano-machining through mechanical cutting. In Manufacturing Engineering and Technology; Qin, Y., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.F.; Lee, W.B. Study of factors affecting the surface quality in ultra-precision diamond turning. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2000, 15, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.; Yang, H.; Sun, S.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Pan, L. Investigation on the surface roughness modeling and analysis for ultra-precision diamond turning processes constrained by the complex multisource factors. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2022, 236, 1295–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, G.; Zong, W.; Sun, T. Study regarding the influence of process conditions on the surface topography during ultra-precision turning. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 102, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarepaka, R.V.; Balan, S.; Doodala, S.; Panwar, R.S.; Kotaria, D.R. Study, analysis, and characterization of ultra-precision diamond tools for single-point diamond turning. J. Micromanuf. 2021, 4, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, Y.; Moronuki, N. Effect of material properties on ultra precise cutting processes. CIRP Ann. 1988, 37, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; To, S.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Z. A review of surface roughness generation in ultra-precision machining. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2015, 91, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A.; Gangopadhyay, S. State-of-the-art in surface integrity in machining of nickel-based super alloys. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2016, 100, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Collins, S.A., Jr.; Yi, A.Y. Optical effects of surface finish by ultraprecision single point diamond machining. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2010, 132, 021002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Dong, G.; Zhou, M. Investigation on frictional wear of single crystal diamond against ferrous metals. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2013, 41, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianxin, D.; Hui, Z.; Ze, W.; Aihua, L. Friction and wear behavior of polycrystalline diamond at temperatures up to 700 °C. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2011, 29, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Le, D.; Lee, S.W.; Song, K.H.; Lee, D.Y. Experiment-based statistical prediction on diamond tool wear in micro grooving NiP alloys. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2014, 41, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Dong, G.J.; Zhou, M. Tool wear and surface roughness in diamond cutting of die steels. Key Eng. Mater. 2014, 589, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narulkar, R.; Bukkapatnam, S.; Raff, L.; Komanduri, R. Graphitization as a precursor to wear of diamond in machining pure iron: A molecular dynamics investigation. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2009, 45, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, G.; Chen, N.; Zhou, M.; Chen, Y. A review of tool wear mechanism and suppression method in diamond turning of ferrous materials. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 113, 3027–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatefi, S.; Abou-El-Hossein, K. Review of non-conventional technologies for assisting ultra-precision single-point diamond turning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 111, 2667–2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatefi, S.; Abou-El-Hossein, K. Review of hybrid methods and advanced technologies for in-process metrology in ultra-high-precision single-point diamond turning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 111, 427–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, G.; Yu, Z.; Huang, J.; Wei, H. Status of research on non-conventional technology assisted single-point diamond turning. Nanotechnol. Precis. Eng. 2023, 6, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, F.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, M.J. Prediction of machining dimension in laser heating and ultrasonic vibration composite assisted cutting of tungsten carbide. J. Adv. Manuf. Syst. 2018, 17, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, S.; Zindani, D. Combined variant of hybrid micromachining processes. In Hybrid Micro-Machining Processes; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmik, S.; Zindani, D. Overview of hybrid micro-manufacturing processes. In Hybrid Micro-Machining Processes; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hatefi, S.; Abou-El-Hossein, K. Review of magnetic-assisted single-point diamond turning for ultra-high-precision optical component manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 120, 1591–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.K.; Yip, W.; To, S. Theoretical and experimental investigations of magnetic field assisted ultra-precision machining of titanium alloys. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 300, 117429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatefi, S.; Abou-El-Hossein, K. Experimental investigation on the effects of magnetic field assistance on the quality of surface finish for sustainable manufacturing of ultra-precision single-point diamond turning of titanium alloys. Front. Mech. Eng. 2022, 8, 1037372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Fang, C.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, F.; Sun, K.; Li, Y.; Lin, Y. Experimental investigation on the machinability improvement in magnetic-field-assisted turning of single-crystal copper. Micromachines 2022, 13, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yip, W.S.; Cao, H.; Zhang, H.; Tang, Y.M.; To, S. Chatter suppression in diamond turning using magnetic field assistance. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 321, 118150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.K.; Yip, W.; Rehan, M.; To, S. A novel magnetic field assisted diamond turning of Ti-6Al-4 V alloy for sustainable ultra-precision machining. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 105829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Rehan, M.; Sun, L.; Tang, J.; Li, D.; Chen, L.; Chen, L.; To, S.; Yip, W.S. Investigation of nanotexture fabrication by magnetic field assisted ultra-precision diamond cutting. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0326046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yin, T.; Li, D.; Sun, Z.; Xue, C.; Yip, W.S.; To, S. Magnetic and ultrasonic vibration dual-field assisted ultra-precision diamond cutting of high-entropy alloys. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2024, 202, 104208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Fu, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Xu, J. Investigation on system design methodology and cutting force optimization in laser-assisted diamond machining of single-crystal silicon. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 115, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H.; Xu, J. Enhancing the ductile machinability of single-crystal silicon by laser-assisted diamond cutting. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 118, 3265–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahinian, H.; Di, K.; Navare, J.; Bodlapati, C.; Zaytsev, D.; Ravindra, D. Ultraprecision laser-assisted diamond machining of single crystal Ge. Precis. Eng. 2020, 65, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, T.; Faisal, N.; Njuguna, J. Recent Developments in Mechanical Ultraprecision Machining for Nano/Micro Device Manufacturing. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhao, X.; Sun, T.; Zhang, J. Finite element simulation and experimental investigation of in-situ laser-assisted diamond turning of monocrystalline silicon. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2024, 39, 065006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; He, W.; Chen, X.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, K.; Huang, W.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J. Experimental and theoretical investigation on the ductile removal mechanism in in-situ laser assisted diamond cutting of fused silica. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 7704–7719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Fu, Y.; He, W.; Wei, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Xu, J. Thermal analysis of in-situ laser assisted diamond cutting of fused silica and process optimization. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 172, 110539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xing, Y.; Yin, S.; To, S. Fabrication of the optical lens on single-crystal germanium surfaces using the laser-assisted diamond turning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 4785–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Shi, G.; Meng, S.; Kong, D.; Yao, D. Experimental study on in-situ laser-assisted diamond turning of single crystal germanium. Precis. Eng. 2025, 94, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, K.; Fang, F.; Yan, G. Surface generation of tungsten carbide in laser-assisted diamond turning. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2021, 168, 103770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]