Abstract

To improve the identification accuracy of leakage layer location in an open-hole well with a distributed fiber optic temperature system, a transient temperature field heat transfer numerical calculation model for bare hole wellbore leakage process was established based on process of the distributed fiber optic open-hole well temperature measurement technology, considering factors such as drilling fluid frictional pressure drop, casing section and bare hole section boundary conditions. The distributed fiber optic test data was compared with the calculation model, and the wellbore calculated temperature distribution was consistent with the test temperature curve, and the temperature characteristics of the leakage layer location were obvious, with a maximum error of less than 5.5%. The calculation results show that when using distributed fiber optic open-hole well leak detection, by extending the continuous injection time of drilling fluid to 30 min and increasing the injection flow rate of drilling fluid by 30 L/s, the temperature at the wellbore leak location reaches 2.7 °C and 6.6 °C, respectively, which can reduce the difficulty of identifying the leak location and improve the accuracy of leak location identification. However, after changing the type of drilling fluid, the calculated wellbore temperature distribution showed a difference of no more than 0.01 °C. When detecting the location of the leakage layer in open-hole wells with high temperature gradients, the temperature difference at the leakage layer is more pronounced, which can reduce the difficulty of leak location via distributed fiber optic system.

1. Introduction

Formation loss is a prevalent issue during drilling operations and has emerged as one of the key research topics in integrated drilling engineering focused on lost-circulation prevention and remediation [1]. As oil and gas exploration advances toward deeper, ultra-deep, and more complex formations, the risks associated with formation loss have grown increasingly prominent [2,3]. Once lost circulation occurs, substantial volumes of drilling fluid are lost, which can contaminate the subsurface environment. Additionally, prolonged drilling duration significantly increases operational costs. Therefore, rapid and accurate identification of the lost-circulation zone along the open-hole section is critical for improving drilling efficiency.

At present, conventional leak-detection techniques primarily include ultrasonic logging, electromagnetic flaw-detection logging, multi-arm caliper imaging, and straddle packer pressure testing [4]. However, these methods are primarily designed for cased-hole environments and suffer from long operating times, low positioning accuracy, and high costs. To overcome these limitations, the successful deployment of distributed fiber-optic temperature sensing in pipeline leak detection and in monitoring production wells has provided a novel technical avenue for locating lost-circulation zones in open-hole wells [5].

In 2013, Yang et al. [6] established a transient heat-conduction equation between the wellbore and the formation under lost-circulation conditions, analyzing how formation temperature, circulation time, and shut-in time affect wellbore temperature. In 2014, Pan et al. [7] used three-dimensional numerical methods to simulate the temperature fields in the wellbore and surrounding formation near a loss zone in carbonate formations. In 2016, Chen et al. [8] developed a wellbore temperature-prediction model after lost circulation based on mass and energy balance equations. In 2019, Wu Xueting et al. [9] further refined the model by incorporating heat generated by bit friction. In 2024, Zhang Zheng et al. [10] derived a two-dimensional transient temperature-field equation for the open-hole section after lost circulation in geothermal wells and solved the annular drilling-fluid temperature distribution using the finite-volume method.

Existing research on post-loss temperature fields primarily center on temperature distributions during drilling-fluid circulation in the drilling process [11,12,13,14], seeking to identify the loss-circulation zone from the derived temperature profile. However, real-time temperature profiles along the wellbore cannot be acquired during drilling, and acquiring bottom-hole temperatures requires additional time [15]. Therefore, grounded in the characteristics of lost circulation in open-hole wells and integrating distributed fiber-optic temperature measurement protocols, this paper establishes a temperature-field model for leak detection that incorporates drilling-fluid properties and frictional effects. The subsequent analysis of temperature variations around the lost-circulation zone offers a theoretical reference for the application of distributed fiber-optic systems in open-hole leak location.

2. Distributed Optical Fiber Open—Hole Wellbores

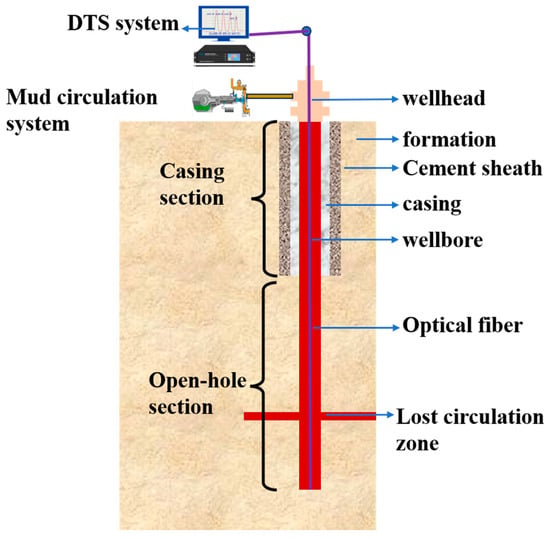

As illustrated in Figure 1, the principle for detecting the location of the distributed optical fiber open-hole wellbore loss zone is as follows, with the operational steps outlined below:

Figure 1.

Schematic of lost circulation in an open-hole.

- (1)

- On the condition that the wellbore is secure, lower the distributed optical fiber into the wellbore for measurement using specialized tools, and complete the instrument connection and calibration.

- (2)

- Keep the wellbore stationary for an adequate duration to allow the drilling fluid, casing, cement sheath, and formation temperature within the wellbore to achieve a balanced state.

- (3)

- Utilize the drilling fluid circulation system to inject drilling fluid with a certain flow rate into the wellbore. The pressure balance between the wellbore and the formation is broken, causing the drilling fluid to flow into the formation through the leakage point.

- (4)

- Once the drilling fluid begins to flow, the thermal equilibrium within the wellbore is altered, destabilizing the temperature distribution throughout the entire wellbore. The temperature must vary above and below the leakage point due to the different modes of heat transfer. Thus, obtaining the temperature curve and the variation characteristics of the wellbore can help identify the location of leakage points in the open-hole wellbore.

3. Study on the Temperature—Field Model of the Lost-Circulation Process in an Open-Hole Wellbore

3.1. Basic Assumptions

The wellbore structure of the open-hole section is illustrated in Figure 1. The upper portion of the wellbore consists of the cased section, which primarily includes the casing, annulus, and formation. The lower section consists of an open-hole, primarily surrounded by formation rocks. Drilling fluid enters the wellbore through the surface manifold, flows through both the cased and open-hole sections, and exits at the lost-circulation zone. During this process, heat is exchanged between the drilling fluid and the wellbore wall, while heat is also generated by flow friction. To establish the temperature-field control equations for each section, the following assumptions are made:

- (1)

- The fluid temperature field varies solely in the axial direction.

- (2)

- The impact of wellbore trajectory eccentricity is minimal.

- (3)

- The flow regime has no impact.

- (4)

- The drilling fluid beneath the lost-circulation zone is assumed to be stationary.

- (5)

- The properties of the formation rocks, casing, and cement sheath are considered to be unaffected by temperature and pressure.

3.2. Transient Heat Transfer Model

3.2.1. Drilling Fluid Energy Conservation Equation

When the drilling fluid flows through the casing section, its mathematical model is established by considering heat transfer with the inner wall of the casing, the heat generated by friction during the flow process, and the heat conduction of the drilling fluid in the axial direction.

In the equation, represents the frictional heat source term generated by the flow of drilling fluid within the casing section, W/m; represents the thermal conductivity of the drilling fluid (W/(m·°C)); and represent the temperatures of the casing’s inner wall and the drilling fluid, respectively (°C); represents the length of the casing section (m); represents the density of the drilling fluid (kg/m3); represents the rate of injection for the drilling fluid (m3/s); represents the inner diameter of the casing (m);The convective heat transfer coefficient of the casing’s inner wall is denoted as (W/(m2·°C)); represents the time (s); represents the specific heat capacity of the drilling fluid (J/(kg·°C)). As the effect of temperature on the specific heat capacity of drilling fluid is significant, the relationship between these two factors is outlined as follows [16]:

In the equation, , , and are the coefficients, with values of 0.0224, 8.4234, and 2275.9, respectively.

In the model, the heat source term is defined as follows:

In the equation, represents the frictional pressure drop of the drilling fluid per unit length of casing (Pa/m); denotes the dimensionless overall friction factor for the flow of drilling fluid within the casing; and represents the casing unit length (m); indicates the cross-sectional area of the casing (m2).

When the drilling fluid flows through the open-hole section, the heat-balance model accounts for the heat exchange between the fluid and the open-hole wall, the heat generated by friction during flow, and the axial thermal conduction of the drilling fluid.

In the formula, represents the frictional heat source term generated by the flow of drilling fluid in the open-hole section, measured in watts per meter (W/m); denotes the inner diameter of the open-hole section, measured in meters (m); and is the convective heat transfer coefficient between the open-hole wellbore wall and the flowing drilling fluid, expressed in watts per square meter per degree Celsius (W/(m2·°C)).

In the model, the heat source term is defined as follows:

In the equation, represents the frictional pressure drop per unit length of drilling fluid in the open-hole section (Pa/m); denotes the overall friction factor of drilling fluid flow in the open-hole section (dimensionless); and indicates the cross-sectional area of the open-hole section (m2).

The drilling fluid below the leak zone remains stationary, while the drilling fluid above the leak zone flows out of the wellbore through the leak point. This fluid exchanges heat with the drilling fluid below the leak zone at the interface [17]. The energy conservation equation is as follows:

In the formula, represents the natural convection heat transfer coefficient between the open-hole wellbore wall and the drilling fluid, measured in W/(m2·°C).

3.2.2. Energy Conservation Equation for Casing

The heat transfer process within the casing involves both axial and radial heat conduction, as well as heat exchange between the flowing drilling fluid and the casing wall. The mathematical model is as follows [18]:

In the equation, represents the thermal conductivity of the casing (W/(m2·°C)); represents outer-wall temperature of the casing (°C); represents casing outer diameter (m); represents heat transfer coefficient at the casing outer wall (W/(m2·°C)); represents casing density (kg/m3); represents specific heat capacity of the casing (J/(kg·°C)); represents inner-wall temperature of the cement sheath (°C).

3.2.3. Cement Sheath Heat Transfer Model

The inner wall of the cement sheath is bonded to the outer wall of the casing, while its outer wall is in intimate contact with the formation; the heat-conduction equation for the cement sheath is as follows [18];

In the equation, represents thermal conductivity of the cement sheath (W/(m2·°C)); represents outer diameter of the cement sheath (m); represents inner diameter of the cement sheath (m); represents inner-wall temperature of the cement sheath (°C); represents temperature at the interface between the formation and the outer wall of the cement sheath (°C); represents heat transfer coefficient at the inner wall of the cement sheath (W/(m2·°C)); represents heat transfer coefficient at the outer wall of the cement sheath (W/(m2·°C)); represents density of the cement sheath (kg/m3); represents specific heat capacity of the cement sheath (J/(kg·°C)).

3.2.4. Formation Heat Transfer Model

Throughout the entire wellbore structure, heat transfer involving the formation can be divided into two regions: the cement-sheath section and the open-hole section. In the upper interval, the formation is in contact with the outer wall of the cement sheath. In the open-hole section, the formation at the borehole wall is in direct contact with the drilling fluid; below the loss-circulation zone, the drilling fluid is static. Owing to the axisymmetric of the wellbore and the assumption that the formation rock has identical thermal conductivities in all directions, only axial and radial heat conduction is considered; the heat-balance equation for the formation is as follows [19].

In the equation, represents axial distance from the wellbore center (m); represents the temperature of formation (°C); represents specific heat capacity of the formation (J/(kg·°C)); represents formation density (kg/m3).

3.3. Initial Conditions and Boundary Conditions

3.3.1. Initial Conditions

Before the drilling fluid begins to circulate in the wellbore, the entire model has reached thermal equilibrium; the temperatures of the drilling fluid, casing, and cement sheath are all equal to the original formation temperature.

In the equation, represents well depth (m); represents surface temperature (°C), represents formation temperature gradient (°C/m).

3.3.2. Boundary Conditions

The temperature of the drilling fluid pumped into the wellbore is equal to the ambient surface temperature.

With the surface temperature taken as the ambient temperature, the boundary condition is as follows.

At the location in the formation closest to the wellbore wall where the original formation temperature remains unaffected by the wellbore temperature, the thermal boundary condition is as follows.

At the bottom of the well, the drilling-fluid temperature is assumed to equal the formation temperature.

At the inner wall of the casing and the wall of the open-hole section, the convective heat exchange with the drilling fluid is as follows.

4. Model Validation

A well in Jimsar County, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, experienced lost circulation at a depth of 1287 m. Subsequently, a distributed fiber optic temperature measurement system was deployed to monitor the wellbore temperature. The key parameters include:

Surface temperature: 10.5 °C

Surface casing density: 8060 kg/m3

Casing depth: 700 m

Casing outer diameter: 244.5 mm

Casing inner diameter: 224.5 mm

Casing thermal conductivity: 43 W/(m·°C)

Cement thermal conductivity: 1.7 W/(m·°C)

Formation lithology: Variegated conglomerate layer

Density: 2100 kg/m3

Thermal conductivity: 2.5 W/(m·°C)

Specific heat capacity: 900 J/(kg·°C)

Drilling fluid: Bentonite-polymer water-based drilling fluid

Specific heat capacity: 4200 J/(kg·°C)

Density: 1150 kg/m3

Thermal conductivity: 0.6 W/(m·°C)

Open-hole diameter: 215.9 mm

Geothermal gradient: 0.0184 °C/m

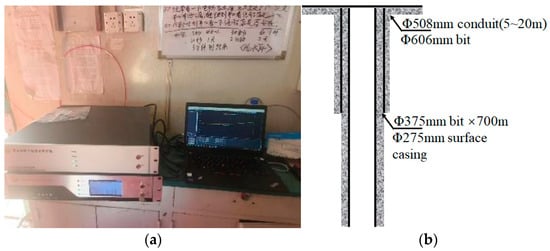

The distributed fiber-optic instrument (CNPC, Beijing, China) and the wellbore structure are shown in Figure 2. The temperature resolution of the distributed fiber-optic instrument is 0.01 °C and the depth of the test wellbore is 1287 m. The leak zone was initially identified at a depth of 900 m using conventional logging methods. Subsequently, a distributed fiber optic temperature measurement system was deployed for relogging. After the installation, equipment debugging, and stabilization of the wellbore temperature field, continuous grouting was initiated at a flow rate of 400 L per minute for 15 min. The first wellbore temperature profile test was then conducted.

Figure 2.

Field Test of Distributed Fiber-Optic Wellbore Temperature. (a) the distributed fiber-optic instrument. (b) wellbore structure.

Following the complete stabilization of both the wellbore fluid level and thermal equilibrium, grouting resumed at an increased flow rate of 800 L/min for a duration of 10 min. Subsequently, temperature data acquisition along the wellbore was conducted.

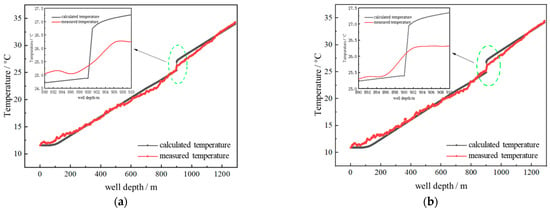

A comparison between the test results and the computational model presented in this study is illustrated in Figure 3. For both drilling fluid injection rates, the experimental temperature curves correspond closely with the computational temperature distribution patterns. It can be found that the measured temperatures surpass the calculated values near the wellhead, with a maximum temperature discrepancy of 0.6 °C observed at a depth of 100 m. This deviation occurs because the experimental wellbore was not fully filled with drilling fluid during injection, which hindered adequate thermal exchange between the fluid and the wellbore. Additionally, the fiber optic cable was not entirely submerged in the drilling fluid. In contrast, the computational model assumes a wellbore that is completely filled with fluid. These factors collectively account for the observed temperatures being higher than the modeled values.

Figure 3.

Comparison of measured and calculated wellbore temperature profiles from distributed fiber-optic testing. (a) qf = 400 L/min Wellbore Temperature Profile. (b) qf = 800 L/min Wellbore Temperature Profile.

Compare the temperature distribution from 200 m to 900 m; the temperature curve of computation is a straight line, while the test temperature cure shows significant fluctuations. The reason is that the rough wellbore affects the flow of drilling fluid and the heat transfer is complex. It can be calculated that the temperatures are 0.37 °C and 0.26 °C for 400 L/min and 800 L/min, respectively.

At the leak zone within the wellbore, the temperature of the drilling fluid flowing downward from above gradually decreases, while the fluid below the leak zone remains static with a nearly constant temperature [20]. Consequently, a sharp temperature transition occurs precisely at the leak zone, establishing this thermal signature as a diagnostic indicator for leak localization.

When comparing the measured and modeled temperatures from both tests, the temperature discrepancies at the leak zone were 0.5 °C and 0.68 °C, respectively. This variance occurs because the computational model assumes equal inflow and outflow rates of drilling fluid, while actual wellbore conditions demonstrate flow rate differences resulting from the combined effects of fluid viscosity and pressure differentials.

5. Example Analysis

When detecting leak points in open-hole wellbores using distributed fiber optics, the temperature signature at the leak zone is often obscured by complex well conditions, making leak localization challenging. To address this issue, we optimized the parameters of the distributed fiber optic temperature field testing process to reshape the temperature distribution profile within the wellbore. This enhancement amplifies the thermal signature of the leak zones, significantly improving the accuracy of leak detection in open-hole wellbores.

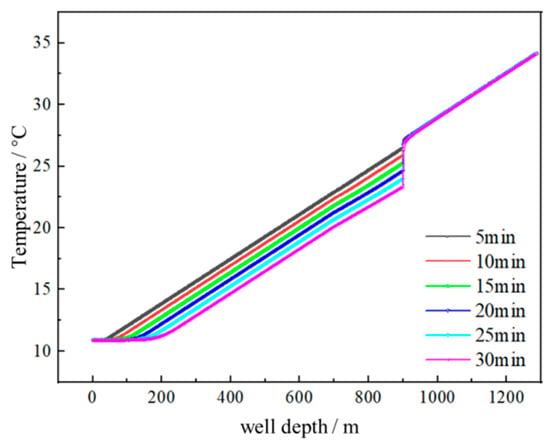

5.1. The Impact of Flow Duration

Figure 4 illustrates the temperature distribution curves of the wellbore following the continuous injection of various drilling fluids over different durations. When the drilling fluid injection rate is set at 5 L/s, the impact depth at the wellhead increases from 47 m to 170 m as the time progresses from 5 to 30 min. Concurrently, above the leaky layer, the temperatures of the drilling fluid in both the casing and open-hole sections decrease by 2.8064 °C and 3.0643 °C, respectively. Below the leaky layer, the temperature of the drilling fluid in the open-hole wellbore remains largely unaffected by time. At the location of the leaky layer, a longer continuous injection time of drilling fluid results in a more significant temperature difference. Specifically, when the continuous injection time is 5 min, the temperature difference across the leaky layer is 0.6398 °C, which increases to 2.7004 °C when the time is extended to 30 min. With a constant flow rate and consistent wellbore structural parameters, the volume of drilling fluid injected into the wellbore is directly proportional to the injection time. Consequently, a greater outflow volume leads to increased heat removal, resulting in a more pronounced temperature difference at the leaky layer and providing a more accurate indication of its location.

Figure 4.

The impact of continuous drilling fluid injection duration on the wellbore temperature distribution.

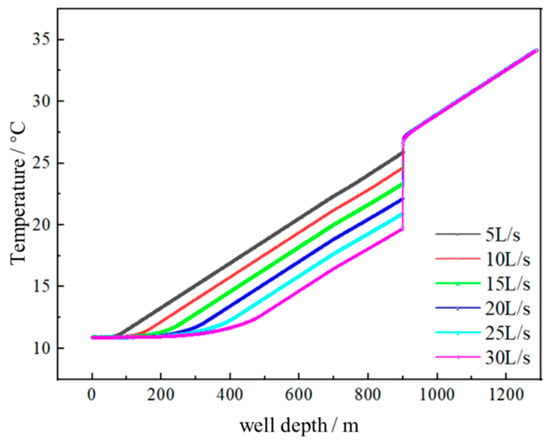

5.2. The Impact of Flow Rate

When the injection time is maintained at 5 min, the effect of the drilling fluid flow rate on the wellbore temperature distribution is illustrated in Figure 5. At a flow rate of 5 L/s, the temperature of the drilling fluid above the leaky layer is 25.8851 °C. However, as the flow rate increases to 30 L/s, the temperature decreases to 19.7132 °C, causing the temperature difference across the leaky layer to rise from 1.1601 °C to 6.595 °C. Under these conditions, a higher flow rate results in increased drilling fluid leakage, which enhances heat removal over the same duration, leading to a more pronounced temperature drop in the wellbore.

Figure 5.

The impact of lost circulation rate at the lost circulation zone on the wellbore temperature.

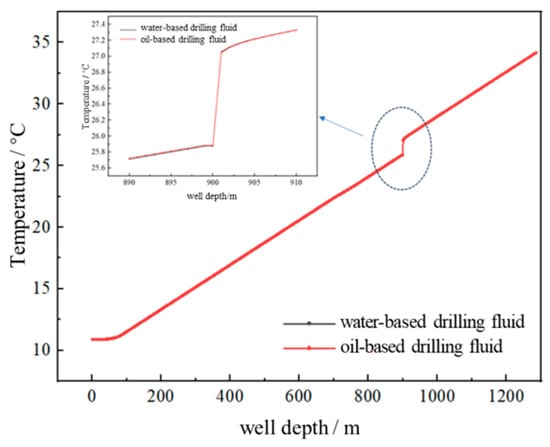

5.3. The Impact of Drilling Fluid Type

As illustrated in Figure 6, the type of drilling fluid has minimal impact on the wellbore temperature distribution curve. With an injection rate of 10 L/s over a duration of 5 min, the temperature curves for both water-based and oil-based drilling fluids are nearly identical. The temperature difference of approximately 0.01 °C between the two fluids, above and below the leaky layer, is negligible. According to Table 1, the thermal diffusivity of water-based drilling fluid is 1.5 times greater than that of oil-based fluid. However, since the temperatures of the wellbore drilling fluid and the formation are similar under the same conditions, both types of drilling fluid exert an insignificant influence on the wellbore temperature.

Figure 6.

The impact of drilling fluid type on the wellbore temperature.

Table 1.

Thermal properties of oil-based and water-based drilling fluids at ambient temperature.

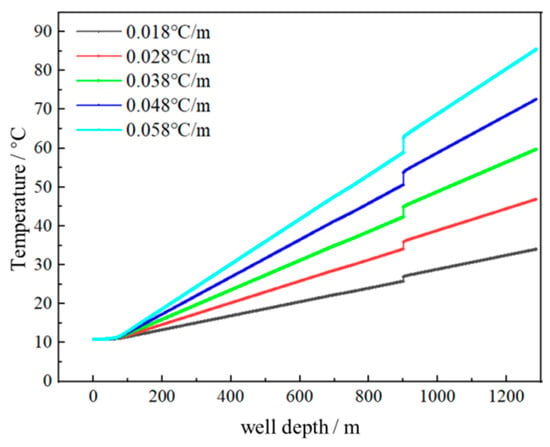

5.4. The Impact of Temperature Gradient During Formation

As illustrated in Figure 7, an increase in the formation temperature gradient steepens the wellbore temperature curve, consistent with the definition of the formation temperature gradient. When the formation temperature gradient rises from 0.018 °C/m to 0.058 °C/m, the temperature difference at the location of the leaky layer increases from 1.1735 to 3.881 °C. Elevated formation temperatures cause the drilling fluid to extract more heat from the wellbore, resulting in more pronounced temperature variations. Consequently, when conducting distributed fiber-optic leaky layer detection in wellbores with a high formation temperature gradient, the temperature difference at the leaky layer location becomes more pronounced.

Figure 7.

The impact of formation temperature gradient on the wellbore temperature distribution.

6. Conclusions

A temperature calculation model for detecting open-hole wellbore leakage layers was established based on distributed optical fiber detection technology. By comparing the temperature curve obtained from distributed fiber optic testing with the model prediction, the distribution patterns were found to be consistent, with a temperature error of less than 5.5%.

Once an open-hole wellbore leakage occurs, the wellbore temperature curve exhibits an abrupt change at the leakage layer. Lower temperatures are recorded above the leakage layer, while higher temperatures are observed below it. Consequently, the temperature curve is effectively divided into two segments at the leakage layer, and this distinct characteristic can be used as a reliable indicator to identify the location of the wellbore leakage layer.

During the detection of leakage zones in open-hole wellbores using distributed optical fiber, increasing both the duration of continuous drilling fluid injection and the fluid flow rate can significantly amplify the wellbore temperature difference. This, in turn, enhances the accuracy of identifying the location of the leakage layer.

The type of drilling fluid exerts a negligible influence on the temperature distribution curve of the open-hole wellbore subsequent to leakage occurrence. Changing the drilling fluid does not significantly improve the capability to identify the location of the open-hole wellbore leakage layer using distributed optical fiber technology. Conversely, in conditions with a higher formation temperature gradient, the temperature characteristics of the exposed wellbore leakage layer detected by distributed optical fiber are more pronounced.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z., Z.H., L.Q., J.W. and Z.J.; Methodology, Z.H.; Software, X.H.; Validation, X.H.; Formal analysis, L.Q. and J.W.; Investigation, X.H., H.T. and Z.L.; Resources, X.H., J.W., Z.L. and Z.J.; Data curation, L.Q., H.T., Z.L. and Z.J.; Writing—original draft, W.Z.; Writing—review & editing, Z.H.; Project administration, L.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by: Research and Technology Development Project of CNPC Well Services Co., Ltd., “Key Technologies Research and Application of CCUS Storage and Utilization” (Grant No. 2024T-001-004-01). Research and Technology Development Project of CNPC Western Drilling Engineering Co., Ltd., “Research on Identification, Early Warning, and Integrated Control Technologies for Complex Lost Circulation Formations” (Grant No. 2025XZ012). Research and Technology Development Project of CNPC Western Drilling Engineering Co., Ltd., “Surface-Excited Magnetic Steering Technology for SAGD” (Grant No. 2023XZ019). Tianshan Talent Program (Grant No. 2024TSYCQNTJ0017).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Wenyuan Zhang, Zhenbao Li and Zhe Jing were employed by the CNPC Western Drilling Company; Xiaobo He, Linjun Qiu and Jie Wu were employed by the Fucheng Oil Sand Resource Development Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The CNPC Western Drilling Company had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Zheng, Y.; Guo, J. Application of expandable tubular plugging technology in long open-hole wells with severe lost circulation. Nat. Gas Ind. 2023, 43, 98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H. Key technical challenges and prospects of drilling and completion in ultra-deep reservoirs. Drill. Prod. Technol. 2024, 47, 28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, Q.; Huang, H.; Ji, G. Challenges and development prospects of oil and gas drilling and completion in myriametric deep formation in China. Drill. Prod. Technol. 2024, 47, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Yan, F.; Pi, S. Seeking fundamental innovations in geoscientific instruments to explore geophysical technology. Chin. J. Geophys. 2024, 67, 4433–4455. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; Li, H.; Zhu, X.; Lu, H.; Tu, K. Fracture parameters diagnosis during staged multi-cluster fracturing based on distributed temperature sensing. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2025, 52, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Meng, Y.; Li, G.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, H. Estimation of wellbore and formation temperatures during the drilling process under lost circulation conditions. Math. Probl. Eng. 2013, 2013, 579091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Li, D.; Chen, G.; Wang, Q.; Ma, L.; Liu, S. Numerical simulation of wellbore and formation temperature fields in carbonate formations during drilling and shut-in in the presence of lost circulation. Pet. Sci. 2014, 11, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, M.; Miska, S.; Ozbayoglu, E.; Zhou, S.; Al-Khanferi, N. Fluid flow and heat transfer modeling in the event of lost circulation and its application in locating loss zones. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2017, 148, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zou, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhou, C. The prediction of wellbore temperature and the determination of thief zone position under conditions of lost circulation. Pet. Drill. Tech. 2019, 47, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, G. Influence of leakage on wellbore temperature distribution during geothermal well drilling. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2024, 24, 9819–9826. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Ji, H.; Xing, P.; Su, Y.; Liu, S.; Wei, F. Theoretical solutions of temperature field and thermal stress field in wellbore of a gas well. Acta Pet. Sin. 2021, 42, 84–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Liu, G. New model of wellbore temperature field during drilling process. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field 2018, 25, 240–243. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Li, J.; Liu, G.; Li, H.; Ya, H. Prediction model of wellbore temperature field during deepwater cementing circulation stage. Pet. Drill. Tech. 2024, 52, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zeng, X.; Jia, S.; Sui, X.; Zhang, Y.; He, H. Wellbore temperature field prediction and influencing factors analysis of gas storage injection production wells. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2022, 22, 7890–7902. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Zhao, C.; Wang, P.; Liang, X.; Yang, M. A comparative study on the calculation accuracy of numerical and analytical models for wellbore temperature in ultra-deep wells. Pet. Drill. Tech. 2022, 50, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; He, M.; Zhang, Y. Research on wellbore temperature prediction model and cooling method for small-diameter ultra-deep wells. Drill. Prod. Technol. 2024, 47, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Luo, M.; Wu, J.; Han, C.; Xiang, S.; Zhang, Z. Coupling analysis of wellbore temperature and pressure field in offshore extreme high pressure-high temperature drilling. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 19, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J.; Hu, Z.; Wang, W.; Dou, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y. Computational fluid dynamics modeling and analysis of axial and radial temperature of wellbore during injection and production process. SPE J. 2024, 29, 2399–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Gao, D.; Yang, J. Prediction of wellbore temperature profile for deep-water ultra-deep wells. Pet. Drill. Prod. Technol. 2020, 42, 558–563. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Xiong, Y.; Peng, G.; Wang, G.; Lu, J.; Zhong, L.; Wang, J.; Yan, Z.; Wei, R. Study on borehole temperature distribution when the well-kick and the well-leakage occurs simultaneously during geothermal well drilling. Geothermics 2022, 104, 102441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.