Abstract

The degradation of bisphenol A (BPA), the main monomer of polycarbonate, was investigated under subcritical water conditions to better understand its decomposition as a function of process conditions and to provide useful data for designing a recycling process to convert polycarbonate into valuable products. Hydrothermal experiments were conducted in a batch reactor at temperatures ranging from 250 to 350 °C, with reaction times from 5 to 30 min and water-to-material ratios of 5, 10, and 15 (mL/g), following a Box–Behnken design with response surface methodology (RSM). The influence of process parameters on phase distribution, total carbon content, and product composition was evaluated. The results showed that temperature and reaction time were the most significant factors affecting BPA decomposition, while the water-to-material ratio had a minor effect. The recovery of the DEE (diethyl ether)-soluble phase decreased with increasing temperature and time, accompanied by a corresponding increase in the water-soluble phase yield and total carbon content. Analysis of the DEE-soluble fraction revealed the sequential transformation of BPA into 4-isopropenylphenol, 4-isopropylphenol, and phenol, with phenol becoming the dominant degradation product at higher temperatures. These findings provide new insights into the hydrothermal decomposition mechanism of BPA and form a basis for understanding polycarbonate degradation and developing sustainable subcritical water recycling processes for polymeric materials.

1. Introduction

The growing global demand for plastic-based products has led to an exponential increase in plastic waste in recent decades [1,2,3]. Polycarbonate (PC) is a high-performance thermoplastic that is widely used in applications such as optical discs, automotive components, electronics, medical devices and food containers due to its transparency, mechanical strength and thermal stability [4,5]. The main monomer used in the production of PC is bisphenol A (BPA) [6]. BPA has attracted much attention not only because of its industrial importance, but also because of its persistence in the environment and potential health hazards [7,8]. As PC waste continues to accumulate in landfills and ecosystems, the development of effective recycling and degradation strategies is becoming increasingly important. One promising route for the chemical recycling of PC is hydrothermal treatment, in which water is used as a reaction medium at elevated temperature and pressure to break down polymer structures [9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

BPA has been detected in a variety of environmental matrices, including surface water, sediments and even human body fluids, raising serious concerns about its endocrine disrupting properties and toxicological consequences [16]. Therefore, understanding the degradation of BPA under environmentally relevant and industrially applicable conditions is of both scientific and practical importance. Advanced oxidation processes, such as UV/H2O2 [17], Fenton reagent [18], and ozone-based oxidation systems [19], have been extensively studied and can achieve high BPA degradation efficiencies, often approaching complete removal under optimized conditions. This makes them suitable for engineered water treatment applications; however, they typically require significant energy input, chemical reagents, and careful control of by-products and operating costs, which can limit their economic viability at large scale without integration or cost recovery strategies [20]. Adsorption and membrane technologies (e.g., activated carbon [21], nanofiltration [22]) are widely used to reduce BPA concentrations in effluents and show high removal efficiencies, but generate solid or concentrated waste streams that must be managed. Biological treatments [23,24] can contribute to BPA removal, but often require long retention times.

Subcritical water, defined as liquid water maintained at temperatures between 100 and 374 °C and under sufficient pressure to remain in a liquid state, has unique solvent properties that can significantly accelerate the degradation of organic compounds without additional chemicals [25]. Hydrothermal processing in subcritical water can rapidly decompose BPA without added oxidants or extensive pre-treatment, but it is inherently more energy- and capital-intensive due to the high pressures and temperatures required. Therefore, the economic feasibility of subcritical water treatment for BPA depends heavily on process integration, heat recovery, and specific treatment objectives, and has not yet been widely demonstrated at full industrial scale compared with more established water treatment technologies [26].

Hydrothermal treatment also fits in well with the principles of green chemistry and sustainable waste management [27]. It uses water as a harmless solvent, operates under relatively mild conditions and offers the potential for selective recovery of valuable intermediate products [28]. By optimizing process parameters such as temperature, reaction time and feedstock concentration, hydrothermal systems can be fine-tuned to increase conversion efficiency and control product selectivity [29]. In addition, the structure of BPA, which consists of two phenolic groups linked by a central isopropylidene bridge, is particularly susceptible to hydrolytic attack under subcritical water conditions, which can lead to smaller phenolic, ketonic or aromatic compounds. These advantages make subcritical water treatment a promising candidate for future applications.

Previous studies have reported partial or complete degradation of BPA under various hydrothermal conditions. Liu et al. [30] used a quartz tube reactor to investigate the stability of BPA in subcritical water and reported that increasing temperature and longer reaction times significantly enhanced BPA decomposition. At 15 min, the BPA yield dropped from 87.8% at 260 °C to 11.1% at 360 °C. Similarly, extending the reaction time from 15 to 75 min at 300 °C reduced the BPA content from 52.1% to 7.6%. However, the study focused primarily on BPA stability and did not quantify the degradation products. Pan et al. [31] reported that at temperatures of 280 °C, 300 °C, and 320 °C, as the reaction time increased from 5 min to 60 min, the yield of BPA decreased from 58 to 27%, from 49 to 10% and from 41 to 4%, respectively. While this study confirmed the strong temperature dependence of BPA decomposition, it addressed product distribution only partially. Adschiri et al. [32] reported over 90% decomposition of BPA at 400 °C (37.2 MPa) after only 5 min. The strength of this work is in demonstrating extremely fast conversion under severe conditions; however, the study reports 2-(hydroxy phenyl)-2-propanol as a decomposition product, which no later study has confirmed. Hunter et al. [33,34] investigated the synthesis of 4-isopropenylphenol via hydrothermal cleavage of BPA and reported 100% conversion of BPA to products (4-isopropenylphenol, 4-isopropylphenol, phenol, acetone) at 300 °C after 60 min. They reported the same maximum yield of 4-isopropenylphenol at 300 °C after 20 min and at 350 °C after 15 min, suggesting that the actual maximum may lie between these reaction conditions.

The motivation for this study goes beyond the decomposition of BPA as an isolated compound. Understanding the fate of BPA during subcritical water treatment is a necessary first step in broader efforts to chemically recycle PC waste into desired products. The degradation of PC is inextricably linked to the stability and degradation pathways of its monomeric components. Therefore, studying the degradation of BPA under controlled hydrothermal conditions helps to establish a mechanistic framework that can later be extended to the PC matrix itself. A response surface methodology (RSM) approach has also never been used before to investigate BPA decomposition under subcritical water conditions.

In this study, the degradation of BPA was systematically investigated under subcritical water conditions. The experiments were carried out in the temperature range from 250 to 350 °C, in time intervals from 5 to 30 min and with different water-to-material ratios of 5/1, 10/1 and 15/1 (mL/g). These parameters were chosen to reflect process conditions under which the degradation of PC also occurs in subcritical water, and to provide insight into the influence of temperature, reaction time and dilution of the feed on the BPA stability and its degradation to specific products. By evaluating the impact of these process variables, the study aims to identify optimal conditions for BPA degradation and clarify the degradation pathways during hydrothermal treatment. The knowledge gained is crucial for further work in the field of PC degradation, with BPA serving as a model compound representing the monomeric unit of the polymer backbone.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

BPA (≥99%), 4-isopropylphenol (4-IPP) (98%) and phenol (≥99%) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Diethyl ether (≥99.9%) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Helium (99.999%) and nitrogen (99.5%) were supplied by Messer (Ruše, Slovenia).

2.2. Hydrothermal Decomposition Procedure and Product Recovery

The hydrothermal degradation of BPA was carried out in a 75 mL batch reactor, series 4740 stainless steel (Parr Instruments GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, Germany). The experiments were conducted according to Box–Behnken design planning with response surface methodology (RSM). Experimental design was created using the Design-Expert Software (version 23.1.8) program and three parameters were optimized: temperature in the range of 250 °C to 350 °C, reaction time from 5 to 30 min and water-to-material ratio from 5 to 15 mL/g. The experimental design included 17 combinations (Table 1), with 5 central point replicates to determine the pure root mean square error.

Table 1.

Design of experiment.

To start the experiment, the required amounts of material and deionized water were added to the reactor together with a magnetic stirrer. To obtain different water-to-material ratio, the amount of water was kept constant, and the amount of material introduced into the reactor was changed. The system was then sealed and purged three times with nitrogen gas through a valve mechanism to create an inert environment. Heating was carried out at a rate of approximately 20 °C per minute until the desired temperature was reached, which was then maintained for a set period of time. Once the reaction was complete, the reactor was rapidly cooled by placing it in cold water to quickly lower the temperature. After the content cooled to room temperature, the gas was released, and the remaining mixture was extracted with diethyl ether (DEE) to separate unreacted BPA and degradation products. Phase separation of the aqueous and DEE layers was performed using a separatory funnel. The DEE-soluble fraction was obtained by evaporating the DEE under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator R-300 (Büchi Labortechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland), and the water-soluble fraction was isolated in a similar manner. The yields of the DEE-soluble and water-soluble products were determined using Equations (1) and (2), respectively.

where γ(DEE) and γ(aq) are the yields of the DEE-soluble and water-soluble phases, respectively, while m(DEE) and m(aq) are the weights of the DEE-soluble and water-soluble phases, respectively, and m(BPA) is the weight of the BPA introduced into the reactor.

γ(DEE) = m(DEE)/m(BPA) × 100%

γ(aq) = m(aq)/m(BPA) × 100%

2.3. Analytical Methods

The analysis of the DEE-soluble fraction was performed with a GC-FID 2010 system (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with an HP-5MS (Agilent Technologies, Santa Carla, CA, USA) capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm inner diameter, 25 µm film thickness) using helium as carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min and diethyl ether (DEE) as the solvent. Samples were introduced in split mode with a ratio of 1:20 at an injection temperature of 250 °C. The oven temperature program started with an initial hold at 50 °C for 5 min, followed by a ramp of 10 °C per minute to 100 °C, held for 1 min, and then further increased at a rate of 5 °C per minute to a final temperature of 280 °C, held for 5 min. The flame ionization detector (FID) was operated at 300 °C. Compound identification and quantification were based on external calibration curves for selected compounds, including BPA, 4-IPP and phenol. Since no commercial standard for 4-isopropenylphenol (4-IPENP) was available, its concentration was estimated using the calibration curve of 4-IPP, as previously described in the literature [33]. The presence of 4-IPENP in the DEE-soluble phase was further verified by GC-MS QP 2010 Ultra (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) analysis. Standards of 4-ethylphenol, p-cresol, 4-tert-pentylphenol and 4-tert-butylphenol were also used, as some studies [12,35] reported them as possible PC or BPA decomposition products, but they were not detected in the DEE-phase of this study. BPA, 4-IPENP, 4-IPP and phenol accounted for more than 85% of the relative peak area recorded by GC/FID.

The yield of the component was calculated according to Equation (3):

where γ(c) is the yield of the individual component, while m(c) is the weight of the component and m(BPA) is the weight of the BPA introduced into the reactor.

γ(c) = m(c)/m(BPA) × 100%

Total carbon (TC) in the water-soluble phase was measured using a TOC-L analyzer (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). Quantification was based on a calibration curve prepared with sodium hydrogen phthalate, covering concentrations from 10 to 1000 mg/L [36]. To ensure the accuracy of the TC values, corrections were made to account for the partial solubility of DEE in water.

3. Results and Discussion

The experimental results on which the RSM model was established and calculated results based on the established models are shown in Table A1 and Table A2 in Appendix A. Larger discrepancies between experimental and predicted values for γ(BPA) (runs 15–17) and for γ(phenol) (run 1) occur because these runs are at the edge of the experimental design space and correspond to very low product concentrations. At the design boundaries, the model has fewer neighboring data points and therefore greater prediction uncertainty; small absolute measurement noise at low concentrations produces large relative errors. In addition, these responses were modeled with a higher-order (quadratic) surface, which can become unstable near the limits of the domain and may amplify small experimental variation. Taken together, these factors explain the larger residuals observed in these specific experiments and do not undermine the overall predictive capability of the model within the central region of the design.

3.1. Product Recovery

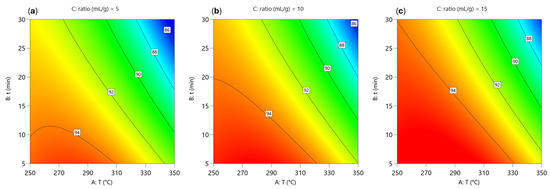

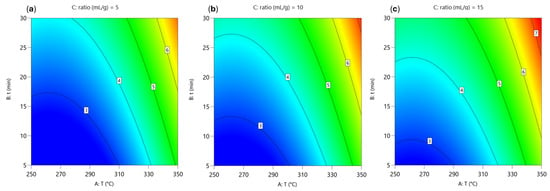

The contour plots in Figure 1 show the effect of temperature, reaction time and water-to-material ratio on the yield of the DEE-soluble phase. In all cases, the DEE-soluble phase yield decreases with increasing temperature and longer reaction time, with the highest yield (>94%) achieved at lower temperatures (250–280 °C) and shorter times (5–15 min). Above 300 °C and with reaction times of 20–30 min, the yield of the DEE-soluble phase decreases, indicating increased decomposition of compounds and their transformation into water-soluble or gaseous components. These trends illustrate the strong dependence of BPA degradation on both temperature and reaction time.

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional contour plots of the predicted yield of the DEE-soluble phase (γ(DEE)) during hydrothermal degradation of BPA. Each contour plot was generated by varying reaction temperature (parameter A) and reaction time (parameter B), while the water-to-material ratio (parameter C) was fixed at: (a) ratio = 5 mL/g, (b) ratio = 10 mL/g and (c) ratio = 15 mL/g.

The model describing the relationship between the yield of DEE-soluble phase and the three variables, obtained by fitting the experimental data, is shown in Equation (4). An F-value of 74.66 and a p-value of <0.0001 indicate that the model is significant. There is only a 0.01% chance that such a large F-value occurs due to noise. p-values below 0.05 indicate that the model terms are significant. In this case, A, B, C, AB, and A2 are significant model terms. The F-value of 0.93 for the lack of fit means that the lack of fit is not significant in relation to the pure error. The predicted R2 of 0.9185 is in reasonable agreement with the adjusted R2 of 0.9584, as the difference is less than 0.2. The value of adequate precision, which measures the signal-to-noise ratio (ratio greater than 4 is desirable), is 31.762, indicating a reasonable signal. This model can be used to navigate the design space.

where A is T (°C), B is t (min) and C is water-to-material ratio (mL/g).

γ(DEE) (%) = 47.78083 + 0.3293500 × A + 0.473000 × B + 0.115000 × C − 0.001210 × A × B − 0.000578 × A2

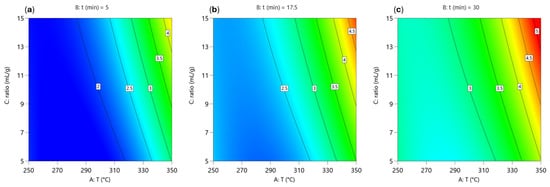

The contour plots in Figure 2 show the effect of temperature and reaction time on the yield of the water-soluble phase at different water-to-material ratios. In all cases, the lowest yields (1.5–2.0%) are observed at moderate temperatures (270–300 °C) and shorter reaction times (5–15 min). The yield increases gradually with both temperature and time, reaching maximum values of 3.5–4.0% at higher temperatures (>320 °C, >20 min). A clear effect of water-to-material ratio can be observed. Higher ratios (15 mL/g) shift the yield to higher values, especially at higher temperatures.

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional contour plots of the predicted yield of the water-soluble phase (γ(aq)) during hydrothermal degradation of BPA. Each contour plot was generated by varying reaction temperature (parameter A) and water-to-material ratio (parameter C), while the reaction time (parameter B) was fixed at: (a) t = 5 min, (b) t = 17.5 min and (c) t = 30 min.

The model for predicting the yield of water-soluble phase is given by Equation (5). The F-value of 36.31 and the p-value of <0.0001 indicate that the model is significant. In this case, A, B, C, AC, and A2 are significant model terms (p < 0.05). The F-value of 7.29 for lack of fit means that the lack of fit is not significant in relation to the pure error. The predicted R2 of 0.8112 is in reasonable agreement with the adjusted R2 of 0.9169. Adequate precision of 20.3091 indicates a reasonable signal. This model can be used to navigate the design space.

where A is T (°C), B is t (min) and C is water-to-material ratio (mL/g).

γ(aq) (%) = 26.82408 − 0.179408 × A + 0.039000 × B − 0.190526 × C + 0.001400 × A × C + 0.000305 × A2

3.2. DEE-Phase Composition

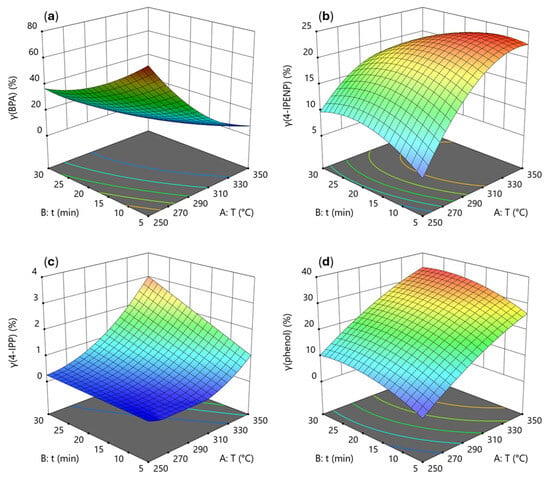

The modeling was also carried out for the residual BPA and the individual yields of the main degradation products in the DEE phase (Figure 3), which were 4-IPENP, 4-IPP, and phenol. The response surfaces were expressed by mathematical equations (Equations (6)–(9)) that allow predictions of the response as a function of the factor values. The mathematical models determined in this study are quadratic.

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional response surfaces representing the influence of temperature and time (water-to-material ratio = 10 mL/g) on degradation products: (a) γ(BPA), (b) γ(4-IPENP), (c) γ(4-IPP) and (d) γ(phenol).

According to the ANOVA results, the regression models for the yields of the main degradation products and residual BPA (Equations (6)–(9)) were highly significant (p < 0.0001). For BPA, the model reached a coefficient of determination of R2 = 0.9894 with a non-significant lack of fit (p = 0.0937). For 4-IPENP, R2 = 0.9716 (p = 0.1465); for 4-IPP, R2 = 0.9925 (p = 0.1590); and for phenol, R2 = 0.9683 (p = 0.4436). These results confirm a good fit of the model to the experimental data. The adequate precision values, which reflect the signal-to-noise ratio, confirmed that the models provided sufficient signals to make them suitable for navigation in design space.

After 5 min, γ(BPA) decreased from 77% at 250 °C to 32% at 300 °C and further to 9% at 350 °C. At 300 °C, extending the reaction time from 5 to 10 and then to 20 min reduced γ(BPA) from 32% to 24% and then to 13%. The yield of BPA steadily decreases with increasing temperature and time, reflecting its progressive decomposition.

From Equation (6) it can be observed that the water-to-material ratio (parameter C) does not have an influence on the BPA decomposition behavior. Hunter et al. [34] proved that the main hydrothermal decomposition mechanism of BPA is base catalysis by water. Thus, it can be concluded that, at all investigated water-to-material ratios, the excess of water is so great that the ratio does not affect the decomposition behavior in this step.

A preliminary kinetic study was conducted on BPA decomposition in subcritical water. Based on previous studies of BPA degradation and hydrothermal depolymerisation of polycarbonate [34,35], as well as testing zero-, first- and second-order kinetics on BPA concentration obtained in our experiments, BPA decomposition was assumed to follow first-order kinetics. Rate constants (k) were estimated independently at each temperature (250, 275, 300, 325, and 350 °C). It should be emphasised that the derived parameters were obtained from RSM model-based data. The rate constants (Appendix A, Table A3) increased with temperature, from 0.0326 min−1 at 250 °C to 0.2159 min−1 at 350 °C, indicating a strong temperature dependence of the reaction rate.

An Arrhenius analysis of the estimated rate constants gave an activation energy (Ea) of 50.6 kJ/mol and ln(A) of 8.1 min−1. This activation energy is within the range reported for BPA decomposition in subcritical water (15–80 kJ/mol) [30,34,35]. These kinetic parameters provide quantitative support for the conclusion that temperature is the key controlling factor for BPA decomposition under the investigated hydrothermal conditions.

One particularly interesting degradation product is 4-IPENP, which is used as a reactant in the preparation of indanols and also serves as an intermediate in the production of stabilizers, dyes, plastics, pesticides, and photochemical materials [33,34]. 4-IPENP is most conveniently synthesized through the cleavage of BPA. This reaction proceeds at low pressure (≈0.02 atm) and elevated temperatures (>150 °C) in the presence of an alkaline catalyst. However, achieving high 4-IPENP yields is challenging, as the product readily undergoes oligomerization [37].

The results of this research show that intermediate 4-IPENP accumulates significantly under harsher conditions and becomes one of the major components of the DEE-soluble phase. The optimal process conditions for recovery of 4-IPENP, as calculated by the model, are 335 °C, 12.3 min, and a ratio of 12.2 mL/g, where a yield of 4-IPENP of 24% is predicted. This agrees with the results of Hunter et al. [33], where the maximum yield of 4-IPENP by BPA hydrothermal decomposition was determined experimentally at a temperature of 300 and a reaction time of 20 min, and it was 31%. The difference in the maximum yield could be due to the influence of the heating rate and the size of reactor.

4-IPP occurs only in small amounts (<3%) at higher temperatures (>300 °C) and longer reaction times (>15 min). 4-IPP forms from 4-IPENP by hydrogenation reactions [33] and requires higher temperatures and longer reaction times. In the investigation of hydrothermal PC degradation by Jin et al. [35], 4-IPP formed intensively from 4-IPENP at temperatures higher than 350 °C and reaction times longer than 30 min.

Phenol shows the greatest increase in content among all investigated products, especially at elevated temperatures (>300 °C). Phenol is formed in the first decomposition step from BPA and also later from various intermediate products [34], confirming its role as the primary degradation product. Within the investigated design space, the maximum phenol content occurs at 350 °C, 24.8 min, and a ratio of 9.7 mL/g, where the yield was 34.7%. It is expected that at higher temperatures (>370 °C) phenol degradation will also begin [38]. The predicted maximum γ(phenol) does not differ much from the experimentally obtained value (35.0%) after 30 min (350 °C, 10 mL/g), but from a process optimization perspective, it is important to keep the reaction time as short as possible, as this reduces energy consumption for heating during the process. The maxima were determined within the scope of the design space (temperature from 250 to 350 °C, reaction time from 5 to 30 min, water-to-material ratio from 5 to 15 mL/g), with only the selected yield being the maximized parameter.

4-IPENP and phenol constitute the largest portion of the DEE phase, especially at higher reaction temperatures (above 300 °C). Both compounds are valuable chemical intermediates: phenol is an established industrial feedstock [39], while 4-IPENP can serve as a precursor for specialty polymers, additives, or fine chemical synthesis [33,34]. The separation of components in the DEE-phase could be achieved by conventional separation techniques; one option is azeotropic distillation [40].

where A is T (°C), B is t (min) and C is the water-to-material ratio (mL/g).

γ(BPA) (%) = 667.31771 − 3.40925 × A − 6.56824 × B + 0.014680 × A × B + 0.004416 × A2 + 0.036493 × B2

γ(4-IPENP) (%) = −239.31140 + 1.42090 × A + 1.99716 × B + 2.21950 × C − 0.004560 × A × B − 0.002041 × A2 − 0.019376 × B2 − 0.091100 × C2

γ(4-IPP) (%) = 16.36026 − 0.129576 × A − 0.126000 × B + 0.404079 × C + 0.000760 × A × B − 0.001800 × A × C − 0.006000 × B × C + 0.000254 × A2 + 0.007421 × C2

γ(phenol) (%) = −155.47560 + 0.806900 × A + 1.04764 × B + 2.27550 × C − 0.000949 × A2 − 0.021104 × B2 − 0.117900 × C2

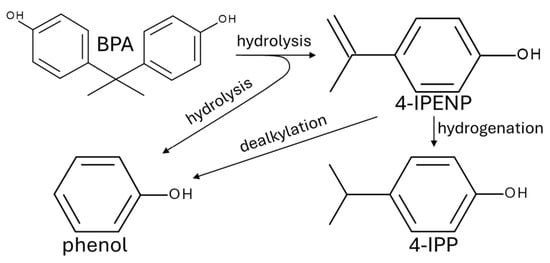

The trends in product composition provide insight into the degradation pathways of BPA (Figure 4). Due to its thermal instability in subcritical water, BPA readily undergoes hydrolytic cleavage of carbonate linkages, resulting in the formation of simpler phenolic compounds, primarily phenol and alkyl-substituted phenols. Among these, 4-IPENP was identified as a key intermediate. Its appearance at early reaction stages, before the formation of saturated alkylphenols, indicates that 4-IPENP is formed directly from BPA via hydrolysis reactions promoted by the elevated ionic product of subcritical water. In the temperature range investigated, subcritical water exhibits a significantly increased concentration of H+ and OH− ions and a reduced dielectric constant, which enhances both hydrolytic activity and the solubility of hydrophobic aromatic intermediates [41]. With increasing reaction severity, 4-IPENP undergoes subsequent hydrogenation to 4-IPP or decomposes through C–C bond cleavage (dealkylation) to yield phenol. The structural similarity between 4-IPENP and 4-IPP, along with the gradual decrease in 4-IPENP concentration and the concurrent increase in 4-IPP, supports a sequential conversion mechanism. The accumulation of phenol across a wide range of reaction conditions highlights its role as a central product and branching point in the degradation network. However, at high temperatures and prolonged exposure times, phenol can undergo secondary reactions, including further cracking, reforming, or gasification [42]. These observations collectively support the proposed degradation pathway and demonstrate that the evolution of product distributions is strongly governed by the temperature-dependent physicochemical properties of subcritical water.

Figure 4.

BPA decomposition mechanism in subcritical water.

3.3. Total Carbon Content in Water-Soluable Phase

The two-dimensional contour diagram in Figure 5 shows the influence of temperature (T, °C) and reaction time (t, min) on the total carbon (TC) concentration in the water-soluble phase at different water-to-material ratios (5, 10, and 15 mL/g).

Figure 5.

Two-dimensional contour plots of the predicted TC (g/L) during hydrothermal degradation of BPA. Each contour plot was generated by varying reaction temperature (parameter A) and reaction time (parameter B), while the water-to-material ratio (parameter C) was fixed at: (a) ratio = 5 mL/g, (b) ratio = 10 mL/g and (c) ratio = 15 mL/g.

The total carbon concentration in the water-soluble phase increases systematically with both temperature and reaction time, reflecting the progressive conversion of BPA and its degradation products into water-soluble intermediates and degradation products. At lower temperatures (250–300 °C) and short reaction times (5–15 min), TC values remain low (approximately 3–4 g/L). As the reaction temperature rises above 300 °C and the time extends beyond 20 min, TC concentrations increase (up to 6–7 g/L), suggesting intensified formation of smaller organic compounds. This trend is consistent with the previous finding on the yield of the water-soluble phase (γ(aq)), which also increases under more severe conditions and indicates that the enhanced yield is primarily driven by the accumulation of polar organic carbon species that likely originate from further fragmentation of DEE-soluble compounds and residuals not recovered in the organic (DEE) phase.

The model for TC in the water-soluble phase is presented in Equation (10). An F-value of 35.45 and a p-value of <0.0001 indicate that the model is significant. In this case, A, B, C and A2 are significant model terms (p < 0.05). The F-value of 0.2169 for lack of fit indicates that the lack of fit is not significant in relation to the pure error. The predicted R2 of 0.8714 is in reasonable agreement with the adjusted R2 of 0.8960. The R2 value for TC is lower compared to the other responses, but the model was optimized to capture general compositional trends rather than to maximize R2 specifically for TC; therefore, a slightly lower R2 is acceptable within the intended predictive scope. An adequate precision of 19.5414 indicates a reasonable signal. This model can be used to navigate the design space.

where A is T (°C), B is t (min) and C is the water-to-material ratio (mL/g).

TC (g/L) = 27.74809 − 0.200761 × A + 0.071620 × B + 0.057275 × C + 0.000383 × A2

4. Conclusions

The decomposition behavior of BPA under subcritical water conditions was investigated at temperatures between 250 and 350 °C, reaction times from 5 to 30 min, and water-to-material ratios of 5, 10 and 15 (mL/g), using RSM based on a Box–Behnken design. The results showed that both temperature and reaction time significantly affected BPA degradation and product distribution, while the water-to-material ratio had a less pronounced effect. The yield of the DEE-soluble phase decreased with increasing temperature and reaction time, indicating progressive BPA decomposition and redistribution of degradation products to other phases (water, gas phase).

Analysis of the DEE-soluble fraction showed that BPA decomposes sequentially, forming compounds such as 4-IPENP, 4-IPP, and phenol. The yield of BPA steadily decreases with increasing temperature and time (from 77% to 9% at a reaction time of 5 min as the temperature increases from 250 °C to 350 °C, and from 32% to 13% at 300 °C as the reaction time increases from 5 to 20 min). The maximum yield of 4-IPENP (24%) was calculated at 335 °C, 12 min, and a water-to-material ratio of 12 mL/g, confirming its role as the key intermediate in the hydrothermal decomposition pathway of BPA. Phenol was identified as the predominant product at higher temperatures and longer reaction times (calculated maximum of 34.7% at 350 °C after 24.8 min, ratio = 9.6 mL/g), formed both directly from BPA and from secondary degradation of intermediates.

The findings offer valuable insights into the hydrothermal degradation mechanism of BPA and its transformation pathways under subcritical water conditions. As BPA is the main monomeric unit of PC, the results also offer an important basis for designing hydrothermal recycling of PC to obtain desired products.

Author Contributions

M.I.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing—Original, Writing—Review & Editing. M.Č.: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing—Review & Editing. M.Š.: Conceptualization, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS) within the frame of research program no. P2-0421, project no. GC-0007 and young researcher fellowship awarded to M.I. The authors also acknowledge the funding within the project “Upgrading National Research Infrastructures—RIUM”, which was co-financed by the Republic of Slovenia, the Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Innovation, and the European Union from the European Regional Development Fund.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to the Laboratory for Separation Processes and Product Design, Faculty of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, University of Maribor for all the technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PC | Polycarbonate |

| BPA | Bisphenol A |

| 4-IPENP | 4-Isopropenylphenol |

| 4-IPP | 4-Isopropylphenol |

| TC | Total carbon |

| DEE | Diethyl ether |

| RSM | Response Surface Method |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Experimental and predicted results for γ(DEE), γ(aq) and TC.

Table A1.

Experimental and predicted results for γ(DEE), γ(aq) and TC.

| Experiment # | T (°C) | t (min) | Water-to-Material Ratio (mL/g) | γ(DEE) (%) | γ(aq) (%) | TC (g/L) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Predicted | Experimental | Predicted | Experimental | Predicted | ||||

| 1 | 250 | 5 | 10 | 95.2 | 94.8 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.91 | 2.46 |

| 2 | 250 | 17.5 | 5 | 93.3 | 94.1 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 2.75 | 3.06 |

| 3 | 250 | 17.5 | 15 | 94.6 | 94.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 3.42 | 3.64 |

| 4 | 250 | 30 | 10 | 93.4 | 93.4 | 3.2 | 2.9 | 4.32 | 4.25 |

| 5 | 300 | 5 | 5 | 94.5 | 94.9 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 3.00 | 2.68 |

| 6 | 300 | 5 | 15 | 95.0 | 94.9 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 3.03 | 3.25 |

| 7 | 300 | 17.5 | 10 | 92.2 | 92.8 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 3.24 | 3.86 |

| 8 | 300 | 17.5 | 10 | 92.4 | 92.8 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 4.40 | 3.86 |

| 9 | 300 | 17.5 | 10 | 93.0 | 92.8 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3.50 | 3.86 |

| 10 | 300 | 17.5 | 10 | 92.7 | 92.8 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 3.41 | 3.86 |

| 11 | 300 | 17.5 | 10 | 93.6 | 92.8 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 4.67 | 3.86 |

| 12 | 300 | 30 | 15 | 92.1 | 90.8 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 5.16 | 5.04 |

| 13 | 300 | 30 | 5 | 90.0 | 90.8 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 4.32 | 4.47 |

| 14 | 350 | 5 | 10 | 92.5 | 92.0 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 5.05 | 5.39 |

| 15 | 350 | 17.5 | 15 | 88.7 | 88.7 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 6.74 | 6.57 |

| 16 | 350 | 17.5 | 5 | 88.0 | 88.7 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 5.98 | 6.00 |

| 17 | 350 | 30 | 10 | 85.4 | 85.3 | 4.4 | 4.6 | 7.36 | 7.18 |

Table A2.

Experimental and predicted results for γ(BPA), γ(4-IPENP), γ(4-IPP) and γ(phenol).

Table A2.

Experimental and predicted results for γ(BPA), γ(4-IPENP), γ(4-IPP) and γ(phenol).

| Experiment # | T (°C) | t (min) | Water-to-Material Ratio (mL/g) | γ(BPA) (%) | γ(4-IPENP) (%) | γ(4-IPP) (%) | γ(phenol) (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Predicted | Experimental | Predicted | Experimental | Predicted | Experimental | Predicted | ||||

| 1 | 250 | 5 | 10 | 79.8 | 77.4 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 5.0 | 2.6 |

| 2 | 250 | 17.5 | 5 | 47.1 | 51.5 | 6.8 | 6.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 6.1 | 7.2 |

| 3 | 250 | 17.5 | 15 | 51.2 | 51.5 | 11.3 | 10.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 8.3 | 6.4 |

| 4 | 250 | 30 | 10 | 39.1 | 36.9 | 8.2 | 9.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 7.2 | 10.3 |

| 5 | 300 | 5 | 5 | 31.2 | 32.1 | 15.1 | 14.8 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 13.3 | 14.3 |

| 6 | 300 | 5 | 15 | 33.3 | 32.1 | 17.0 | 18.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 12.3 | 13.5 |

| 7 | 300 | 17.5 | 10 | 14.2 | 15.2 | 21.0 | 21.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 21.3 | 24.0 |

| 8 | 300 | 17.5 | 10 | 16.5 | 15.2 | 22.7 | 21.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 25.0 | 24.0 |

| 9 | 300 | 17.5 | 10 | 15.5 | 15.2 | 20.6 | 21.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 26.4 | 24.0 |

| 10 | 300 | 17.5 | 10 | 15.5 | 15.2 | 22.0 | 21.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 24.6 | 24.0 |

| 11 | 300 | 17.5 | 10 | 12.7 | 15.2 | 20.9 | 21.4 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 22.8 | 24.0 |

| 12 | 300 | 30 | 15 | 11.3 | 9.9 | 18.4 | 17.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 21.3 | 21.2 |

| 13 | 300 | 30 | 5 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 14.0 | 13.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 24.2 | 22.1 |

| 14 | 350 | 5 | 10 | 6.0 | 8.8 | 24.1 | 22.6 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 26.2 | 26.4 |

| 15 | 350 | 17.5 | 15 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 21.6 | 21.9 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 29.4 | 30.2 |

| 16 | 350 | 17.5 | 5 | 4.1 | 1.1 | 16.5 | 17.9 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 31.0 | 31.0 |

| 17 | 350 | 30 | 10 | 2.5 | 4.9 | 15.8 | 15.7 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 35.0 | 34.1 |

Table A3.

Rate constants (k), activation energy (Ea) and a pre-exponential factor ln(A) for BPA decomposition in subcritical water based on the RSM model.

Table A3.

Rate constants (k), activation energy (Ea) and a pre-exponential factor ln(A) for BPA decomposition in subcritical water based on the RSM model.

| T (°C) | k (mol∙L−1∙min−1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| 250 | 0.0326 | 0.9872 |

| 275 | 0.0484 | 0.9241 |

| 300 | 0.0695 | 0.8686 |

| 325 | 0.1216 | 0.8767 |

| 350 | 0.2159 | 0.9097 |

| Ea (kJ/mol) | 50.6 | 0.9761 |

| ln(A) (min−1) | 8.1 |

References

- Nayanathara Thathsarani Pilapitiya, P.G.C.; Ratnayake, A.S. The World of Plastic Waste: A Review. Clean. Mater. 2024, 11, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi Kalali, E.; Lotfian, S.; Entezar Shabestari, M.; Khayatzadeh, S.; Zhao, C.; Yazdani Nezhad, H. A Critical Review of the Current Progress of Plastic Waste Recycling Technology in Structural Materials. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2023, 40, 100763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiounn, T.; Smith, R.C. Advances and Approaches for Chemical Recycling of Plastic Waste. J. Polym. Sci. 2020, 58, 1347–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Grand, D.G.; Bendler, J.T. (Eds.) Handbook of Polycarbonate Science and Technology; Plastics Engineering; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, NY, USA; Basel, Switzerland, 2000; ISBN 978-0-8247-9915-1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Zhan, L.; Xie, B.; Gao, B. Products Derived from Waste Plastics (PC, HIPS, ABS, PP and PA6) via Hydrothermal Treatment: Characterization and Potential Applications. Chemosphere 2018, 207, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, K. 5.16—Polycarbonates. In Polymer Science: A Comprehensive Reference; Matyjaszewski, K., Möller, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 363–376. ISBN 978-0-08-087862-1. [Google Scholar]

- Metz, C.M. Bisphenol A: Understanding the Controversy. Workplace Health Saf. 2016, 64, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengstler, J.G.; Foth, H.; Gebel, T.; Kramer, P.-J.; Lilienblum, W.; Schweinfurth, H.; Völkel, W.; Wollin, K.-M.; Gundert-Remy, U. Critical Evaluation of Key Evidence on the Human Health Hazards of Exposure to Bisphenol A. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2011, 41, 263–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, A.; Katoh, K.; Tagaya, H. Monomer Recovery of Waste Plastics by Liquid Phase Decomposition and Polymer Synthesis. J. Mater. Sci. 2008, 43, 2437–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmer Pedersen, T.; Conti, F. Improving the Circular Economy via Hydrothermal Processing of High-Density Waste Plastics. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.A.; Shaver, M.P. Depolymerization within a Circular Plastics System. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 2617–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonakou, E.V.; Achilias, D.S. Recent Advances in Polycarbonate Recycling: A Review of Degradation Methods and Their Mechanisms. Waste Biomass Valorization 2013, 4, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, R.; Zenda, K.; Hatakeyama, K.; Yui, K.; Funazukuri, T. Reaction Kinetics of Hydrothermal Depolymerization of Poly(Ethylene Naphthalate), Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate), and Polycarbonate with Aqueous Ammonia Solution. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2010, 65, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grause, G.; Tsukada, N.; Hall, W.J.; Kameda, T.; Williams, P.T.; Yoshioka, T. High-Value Products from the Catalytic Hydrolysis of Polycarbonate Waste. Polym. J. 2010, 42, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagaya, H.; Katoh, K.; Kadokawa, J.; Chiba, K. Decomposition of Polycarbonate in Subcritical and Supercritical Water. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1999, 64, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- vom Saal, F.S.; Myers, J.P. Bisphenol A and Risk of Metabolic Disorders. JAMA 2008, 300, 1353–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.G.; Jo, E.Y.; Park, S.M.; Jeon, H.W.; Ko, K.B. Degradation of Bisphenol A by UV/H2O2 Oxidation in Aqueous Solution Containing Nitrate and Alkalinity. Desalination Water Treat. 2015, 54, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gözmen, B.; Oturan, M.A.; Oturan, N.; Erbatur, O. Indirect Electrochemical Treatment of Bisphenol A in Water via Electrochemically Generated Fenton’s Reagent. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 3716–3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Yun, J.; Zhang, H.; Si, J.; Fang, X.; Shao, L. Degradation of Bisphenol A by Ozonation in Rotating Packed Bed: Effects of Operational Parameters and Co-Existing Chemicals. Chemosphere 2021, 274, 129769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Costa, M.J.; Araújo, J.V.S.; Moura, J.K.L.; da Silva Moreno, L.H.; Pereira, P.A.; da Silva Santos, R.; Moura, C.V.R. A Brief Review of Detection and Removal of Bisphenol A in Aqueous Media. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2022, 233, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Lara, M.A.; Calero, M.; Ronda, A.; Iáñez-Rodríguez, I.; Escudero, C. Adsorptive Behavior of an Activated Carbon for Bisphenol A Removal in Single and Binary (Bisphenol A—Heavy Metal) Solutions. Water 2020, 12, 2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, S.; Kabay, N.; Yüksel, M. Removal of Bisphenol A (BPA) from Water by Various Nanofiltration (NF) and Reverse Osmosis (RO) Membranes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 263, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, G.; Wu, X.; Tang, K.H.D.; Li, R. Microbial Degradation of Bisphenol A—A Mini-Review. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2025, 43, 100595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razia, S.; Hadibarata, T.; Lau, S.Y. A Review on Biodegradation of Bisphenol A (BPA) with Bacteria and Fungi under Laboratory Conditions. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2024, 195, 105893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, A.; Pedroso, G.B.; Kuriyama, S.N.; Fidalgo-Neto, A.A. Subcritical and Supercritical Water for Chemical Recycling of Plastic Waste. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2020, 25, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, H.; Takesue, M.; Smith, R.L. Green Chemical Processes with Supercritical Fluids: Properties, Materials, Separations and Energy. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2011, 60, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P.T.; Warner, J.C.; Warner, J.C. Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice; 1. Paperback; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; ISBN 978-0-19-850698-0. [Google Scholar]

- Benmakhlouf, N.; Outili, N.; García-Jarana, B.; Sánchez-Oneto, J.; Portela, J.R.; Jeguirim, M.; Meniai, A.-H. Applications of Supercritical Water in Waste Treatment and Valorization: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boel, M.J.; Wang, H.; AL Farra, A.; Megido, L.; González-LaFuente, J.M.; Shiju, N.R. Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Plastics: A Survey of the Effect of Reaction Conditions on the Reaction Efficiency. React. Chem. Eng. 2024, 9, 1014–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jin, Z.; Liu, L.; Huang, Y.; Lin, C.; Pan, Z. Stability of Bisphenol A in High-Temperature Water in Fused Silica Capillary Reactor. Huagong Xuebao/CIESC J. 2011, 62, 2527–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, M.; Fang, Y. Stability of BPA in Near Critical Water. In Proceedings of the 2010 4th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering, Chengdu, China, 18–20 June 2010; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Adschiri, T.; Shibata, R.; Arai, K. Phenol Recovery by BPA Tar Hydrolysis in Supercritical Water. J. Jpn. Pet. Inst. 1997, 40, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.E.; Felczak, C.A.; Savage, P.E. Synthesis of P-Isopropenylphenol in High-Temperature Water. Green Chem. 2004, 6, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.E.; Savage, P.E. Kinetics and Mechanism of P-Isopropenylphenol Synthesis via Hydrothermal Cleavage of Bisphenol A. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 4724–4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Bai, B.; Wei, W.; Chen, Y.; Ge, Z.; Shi, J. Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Polycarbonate (PC) Plastics in Sub-/Supercritical Water and Reaction Pathway Exploration. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 7039–7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čolnik, M.; Knez, Ž.; Škerget, M. Sub- and Supercritical Water for Chemical Recycling of Polyethylene Terephthalate Waste. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2021, 233, 116389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corson, B.B.; Heintzelman, W.J.; Schwartzman, L.H.; Tiefenthal, H.E.; Lokken, R.J.; Nickels, J.E.; Atwood, G.R.; Pavlik, F.J. Preparation of Vinylphenols and Isopropenylphenols. J. Org. Chem. 1958, 23, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, T.L.-K.; Matsumura, Y. Kinetics Analysis of Phenol and Benzene Decomposition in Supercritical Water. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2014, 87, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Hassani, S.; Derakhshani, M. Phenol. In Encyclopedia of Toxicology, 3rd ed.; Wexler, P., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 871–873. ISBN 978-0-12-386455-0. [Google Scholar]

- Takahata, K.; Taniguchi, K.; Fujimoto, T. Process for Separation of Alkylphenols by Azeotropic Distillation. European Patent EP0013133B1, 12 January 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, A.G.; Mammucari, R.; Foster, N.R. A Review of Subcritical Water as a Solvent and Its Utilisation for the Processing of Hydrophobic Organic Compounds. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 172, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Cheng, Z.; Gao, X.; Yuan, T.; Shen, Z. Decomposition of 15 Aromatic Compounds in Supercritical Water Oxidation. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.