Abstract

The uncertainty of baseline load forecasting critically influences both the assessment of load reduction potential and demand response (DR) settlement. Therefore, this paper focuses on assessing load reduction potential based on probabilistic predictions of the baseline load. First, the uncertainty of the baseline load prediction is analyzed through calculating the conditional probability density function (PDF) and interval estimation of baseline load prediction errors from the convolutional neural network (CNN) model. Then, the probabilistic model of load reduction potential is proposed based on the results from the probabilistic prediction of baseline load and the terms about the interruptible load in DR contracts. Finally, the Monte Carlo simulation method is used to assess the load reduction potential, and probability distributions of the load reduction states, the lower and upper limits of the load reduction potential, are analyzed. Case studies demonstrate that the proposed method effectively characterizes the uncertainty of prediction results, with the prediction interval normalized average width (PINAW) decreased by 10.97%, thereby enabling the effective assessment of load reduction potential from the probabilistic perspective, helping decision makers take better choices.

1. Introduction

Demand response (DR) is defined as “the change in electric usage by demand-side resources from their normal consumption patterns in response to changes in electricity prices or incentive payments designed to induce lower electricity use when wholesale market prices are high or when system reliability is at risk” [1,2]. In related research on DR, obtaining advance knowledge of baseline load levels and their reduction potential is often key to implementing DR. Therefore, baseline load forecasting and load reduction potential assessment are both focal points in DR research [3].

Existing research on baseline load forecasting primarily focuses on short-term predictions, with forecasting cycles typically ranging from a few hours to several days [4,5,6,7]. Among current baseline load forecasting methods, some scholars employ traditional point forecasting techniques to predict future load with high accuracy, including statistical methods, machine learning, and deep learning. In statistical methods, time series models such as autoregressive moving average (ARMA), autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA), and vector autoregression (VAR) are widely used. For example, A. Elmouatamid et al. [8] accurately predicted short-term future data using an ARIMA model based on historical baseline load data. However, statistical methods can only handle single time series data and are unable to capture complex nonlinear relationships, meaning they can only predict future data based on the historical data of the variable being forecasted. In contrast, machine learning can not only handle multi-time series datasets but also more accurately model nonlinear relationships between variables. Classic machine learning methods include support vector machine (SVM), support vector regression (SVR), and random forest (RF). For instance, Yongbao Chen et al. [1] proposed a baseline load forecasting method based on SVR. This method uses the ambient temperature from the two hours preceding DR as input variables and employs SVR to model the nonlinear relationship between ambient temperature and baseline load, achieving good prediction accuracy and stability. However, when the dataset is excessively large and structurally complex, machine learning struggles to learn and optimize efficiently [9]. To address this, deep learning based on neural networks can effectively overcome issues caused by large dataset sizes. These methods include feedforward neural network (FFNN), backpropagation neural network (BPNN), recurrent neural network (RNN), long short-term memory (LSTM), and convolutional neural network (CNN), among others. Shengyou Wang et al. [10] proposed a short-term baseline load forecasting method based on LSTM neural networks. By comparing the prediction results of the LSTM model with those of ARIMA and multilayer perceptron (MLP) models in different application scenarios, they found that the LSTM model achieved higher prediction accuracy. In some application scenarios, combining machine learning and deep learning methods yields better forecasting performance. Harikrishnan G R et al. [11] proposed a weighted average ensemble model for short-term baseline load forecasting that combines the machine learning method XGBoost with the deep learning method ANN. Compared to models using only a single machine learning or deep learning method, the XGBoost–ANN ensemble model demonstrated higher prediction accuracy. Abdo Abdullah et al. [12] proposed a short-term forecasting method for DR baseline load based on deep learning, incorporating bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM), LSTM, gated recurrent unit (GRU), CNN, deep neural network (DNN), and RNN. This approach significantly improved baseline load forecasting accuracy across different levels of consumer aggregation.

While traditional point forecasting methods can provide accurate predicted values, they are unable to quantify the uncertainty in the forecasting process. In contrast, probabilistic interval forecasting can provide a fluctuation range for future baseline load, enabling the quantification of result reliability in load reduction assessments [13,14,15,16]. Traditional probabilistic interval forecasting methods, like point forecasting methods, also include statistical approaches and machine learning. Kadir Amasyali et al. [17] proposed a Gaussian process regression-based method for aggregated baseline load forecasting, which quantifies the uncertainty of the baseline load through probabilistic confidence intervals of the predicted values. Nima H. Tehrani et al. [18] introduced a baseline load interval forecasting method using a recursive Bayesian framework, which derives confidence intervals from historical baseline load and temperature data, effectively improving the accuracy of baseline load forecasting. Kangping Li et al. [19] proposed a two-stage decoupled aggregated baseline load estimation method. This method first uses SVR for high-accuracy point estimation and then obtains confidence intervals by analyzing the historical error distribution of the baseline load. When dealing with small-scale and structurally simple datasets, the aforementioned studies achieve high prediction accuracy and fast operational speeds. In summary, at present, most studies mainly use various high-performance prediction models to improve the prediction accuracy of baseline load, and the aforementioned point prediction and probabilistic prediction methods have achieved commendable results.

Additionally, the load reduction potential is crucial for ensuring the safety and stability of modern power systems, effectively supporting load shifting and peak shaving management, and guiding load aggregators in formulating optimal bidding strategies in the market. Some researchers developed deterministic assessment methods to identify high-potential participants [20,21]. Current research on load reduction potential remains limited.

However, significant gaps remain in addressing the probabilistic assessment of load reduction potential by considering the uncertainty of baseline load prediction. Previous studies exhibit limitations in several areas:

- (1)

- As we all know, it is impossible for any prediction method to forecast the baseline load completely accurately, so there is bound to be uncertainty in the prediction results. Since the uncertainty of the baseline load forecast is unavoidable and it directly affects the assessment of load reduction potential, it is very important to study the load reduction potential assessment that takes into account the uncertainty of the baseline load forecast. However, the probabilistic assessment of load reduction potential, grounded in a thorough uncertainty analysis of the baseline load forecast, has not yet been systematically explored.

- (2)

- In the field of load reduction potential assessment, there is a lack of a systematic probabilistic modeling method and algorithm that comprehensively integrates probabilistic baseline load prediction with the specific terms of DR contracts. This methodological gap leads to significant assessment biases and decision-making risks, rendering the evaluation results unsuitable for the execution and settlement of DR contracts, thereby diminishing their practical utility.

Therefore, this study proposes a probabilistic assessment framework for load reduction potential based on baseline load prediction. Following the widely adopted average method in the power industry—valued for its simplicity and transparency—this paper employs the same transparent input data structure while utilizing a CNN to generate probabilistic baseline load forecasts. These probabilistic predictions are then applied to enable a probability-informed assessment of load reduction potential. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

- A method to analyze the uncertainty of the baseline load prediction is proposed, which provide the foundation for the probabilistic assessment of load reduction potential through calculating the conditional probability density function (PDF) and interval estimation of baseline load prediction errors.

- (2)

- The probabilistic assessment model of load reduction potential is proposed based on the results from the probabilistic prediction of baseline load and the terms about the interruptible load in DR contracts.

- (3)

- The Monte Carlo simulation method which performs an assessment of the load reduction potential probabilistic model is presented, and probability distributions of the load reduction states, the lower and upper limits of load reduction potential, are analyzed, helping understand the impact of prediction uncertainty on the load reduction potential.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 develops the CNN prediction model of baseline load. In Section 3, the method to analyze the uncertainty of the baseline load prediction is proposed by using a CNN-based probabilistic prediction model. Section 4 presents the probabilistic assessment model of the load reduction potential and the Monte Carlo simulation method to assess the load reduction potential. Section 5 provides case studies validating the effectiveness of the proposed model and method. Finally, Section 6 provides a summary of the paper.

2. CNN Prediction Model for DR Baseline Load

2.1. Concept of Baseline Load

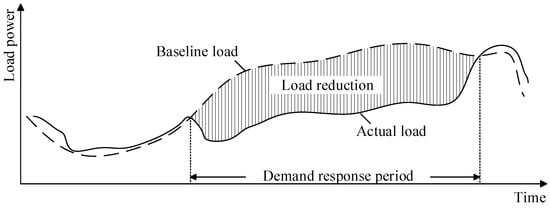

In DR projects, the baseline load refers to the load predicted by the consumer’s historical load data, which does not include those when the consumer participated in DR projects. It reflects the consumer’s own electricity demand when they are not participating in the DR project and is an important basis for the DR project implementation agency to compensate consumers [22]. The load reduction amount, obtained by comparing the predicted consumer baseline load with real-time-monitored actual load data, is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of customer’s baseline load and load reduction.

2.2. CNN Prediction Model for Baseline Load

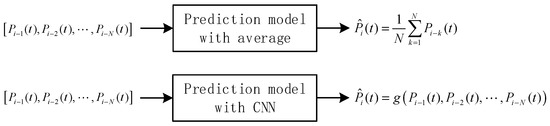

The average method is widely used due to its simplicity and high transparency. It calculates the baseline load for a target day by averaging the loads of similar days preceding it. A similar day refers to a historical day that shares comparable characteristics with the target day, such as day type (weekday/weekend/holiday) and weather conditions, used for baseline load calculation in DR programs. The procedure for selecting similar days involves three main steps: first, identify the target day’s key characteristics (day type, weather, etc.); second, calculate similarity scores between the target day and historical days using distance metrics; third, select the top most similar historical days based on these scores for baseline calculation. The calculation equation of baseline load by the average method is

where represents the predicted value for the t-th period on the i-th day, serving as the baseline load; is the measured historical load for the t-th period of the k-th similar day prior to the i-th day.

The essence of the average method is a linear fitting of the same period load values from days preceding the DR event. Inspired by this, to improve prediction accuracy, a CNN model is constructed to capture the complex nonlinear relationship between the loads of N similar days at the same period and the baseline load at the same period. Therefore, the input data of CNN model are the same as the average method. The Conceptual diagrams of the average method and the CNN method are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Conceptual diagrams of the average method and CNN method.

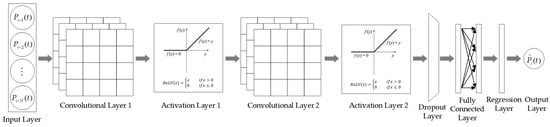

CNNs are characterized by good robustness and the ability to capture spatial hierarchical features of data, gradually becoming one of the important methods in short-term prediction [23]. CNNs fit predicted values by extracting high-dimensional nonlinear features from data through convolutional calculations. The structure of the CNN in the following case study consists of an input layer, convolutional layers, activation layers, dropout layers, fully connected layers, and a regression layer, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Structure of the CNN in the following case study.

- (1)

- Convolutional layer

The convolutional layer is the core of a CNN. It uses a set of learnable filters (or kernels) that slide vertically and horizontally over the input data, performing convolution operations with the covered data. Each filter is responsible for extracting a specific local feature from the input data. Through the mechanism of local connectivity and parameter sharing, the network can efficiently learn features from the data.

- (2)

- Activation layer

The activation layer follows immediately after the convolutional layer, serving to perform nonlinear transformations. Without nonlinear activation functions, the entire network would remain equivalent to a linear model regardless of how many convolutional layers are stacked, rendering it unable to simulate complex nonlinearities. By using nonlinear functions such as ReLU, the neural network is capable of fitting highly complex nonlinear relationships.

- (3)

- Dropout layer

The dropout layer is a regularization technique used during the training phase to prevent model overfitting. During training, it randomly “drops” (i.e., temporarily disables) a portion of the neurons and their connections in the network. This forces the network not to rely overly on a small number of neurons but to learn more robust and uniformly distributed features that remain effective even when neurons are randomly missing, thereby significantly enhancing the model’s generalization ability.

- (4)

- Fully connected layer

The fully connected layer is typically located at the end of a CNN. Its core function is to integrate the highly abstract features extracted by the preceding convolutional layers and make final decisions such as classification or regression. Unlike the local connectivity of convolutional layers, every neuron in a fully connected layer is connected to all neurons in the previous layer, thereby achieving global feature synthesis.

- (5)

- Regression layer

The regression layer is the output layer for solving regression problems, functioning to predict a continuous numerical value. This layer calculates the difference between the network’s predicted value and the true target value via a loss function and guides the entire network’s learning direction by optimizing the loss function value, ultimately outputting the required continuous result.

3. Probabilistic Prediction of DR Baseline Load Based on CNN

3.1. Overall Framework for CNN-Based Probabilistic Prediction of Baseline Load

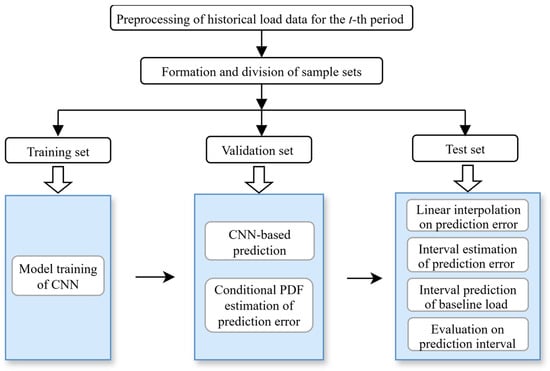

Taking the prediction of the baseline load for the t-th period as an example, the overall framework for CNN-based probabilistic prediction is shown in Figure 4:

Figure 4.

Overall framework of CNN-based probabilistic prediction of baseline load.

First, historical data for the t-th period of the target day is preprocessed, including supplementing missing data and correcting anomalies. Then, a rolling window method is used to form a sample set, which is proportionally divided into training, validation, and test sets. All data are normalized based on the statistics of the training set. Subsequently, the CNN model is trained using the training set data. Next, nonparametric kernel density estimation (KDE) of prediction errors on the validation set is performed, and the conditional PDF of prediction errors is estimated based on Bayesian theory. Finally, linear interpolation is used to obtain the conditional PDF of prediction errors on the test set, thereby deriving confidence intervals of prediction errors and prediction intervals for the baseline load on the test set, followed by an assessment of the performance of prediction intervals.

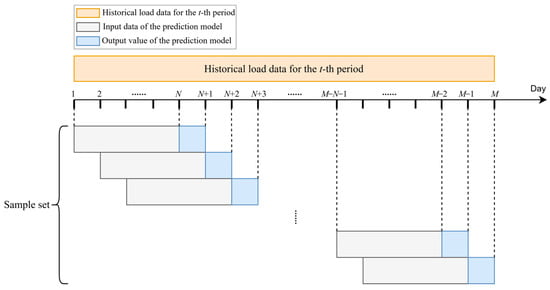

3.2. Formation and Division of Sample Sets

After excluding special days, such as weekends, holidays, and days when DR was implemented, historical load data for the same period (e.g., the t-th period) are obtained and preprocessed. Then, a rolling window method is adopted to form a sample set, where samples consist of input data from the modeling period and output values from the prediction period. Finally, the sample set is divided into training, validation, and test sets. The above process is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Formation of sample sets via rolling window method.

3.3. Nonparametric KDE of Prediction Errors on Validation Set

The CNN model is trained to generate point predictions of the baseline load. After obtaining these predictions, we calculate the prediction errors between the CNN outputs and the actual observed values on the validation dataset. These errors are then used to fit a nonparametric KDE of prediction errors that characterizes the prediction uncertainty.

Assume that, on the validation set, the true value is , the predicted value is , and the prediction error is , , where is the number of samples in the validation set. The prediction error is calculated as

Using the nonparametric KDE method, the marginal PDF of the predicted values on the validation set is estimated according to Equation (3):

where is the PDF estimation of predicted values on the validation set; is the number of samples in the validation set; is the bandwidth in the dimension of predicted values; is the predicted value of the i-th sample; and is a kernel function, such as the standard Gaussian kernel.

The selection of the bandwidth in nonparametric KDE represents a critical bias–variance trade-off. An excessively large bandwidth over-smooths the estimate, suppressing important data features and increasing bias, whereas a bandwidth that is too small yields an under-smoothed, noisy estimate with high variance. Common data-driven selection methods include Silverman’s rule of thumb, least-squares cross-validation, and plug-in methods. The final choice often depends on the data characteristics, sample size, and computational considerations, typically followed by graphical diagnostics to validate the result.

Using the two-dimensional nonparametric KDE method, the joint PDF of predicted values and prediction errors on the validation set is estimated as

where represents the joint PDF estimation of the predicted values and prediction errors on the validation set; denotes the total number of samples in the validation set; is the bandwidth in the dimension of predicted values; is the bandwidth in the dimension of prediction errors; and are the predicted value and prediction error of the i-th sample, respectively; is a two-dimensional kernel function, such as the standard Gaussian kernel.

In nonparametric KDE, the probability density at any given point is estimated via bilinear interpolation over a regular grid formed by predicted values and prediction errors. Specifically, the target point is first located within the grid to identify its four neighboring grid points. Then, based on the relative horizontal and vertical distances to these neighbors, two successive linear interpolations are performed on their known density values, yielding a smoothly interpolated joint probability density at the target point. This process ultimately enables the construction of a continuous conditional PDF.

According to Bayes’ theorem, the conditional PDF estimation of prediction errors on the validation set is obtained as follows:

where represents the conditional PDF estimation of the prediction error on the validation set.

3.4. Conditional PDF Estimation and Interval Estimation of Prediction Errors on Test Set

In contrast to a marginal distribution, conditional distribution of prediction errors can account for heteroscedasticity—the phenomenon where the variance of prediction errors depends on the magnitude of the predicted value. Conditioning on the predicted value can generate prediction intervals that adapt to different load levels, providing more accurate uncertainty quantification for demand response applications.

Assume the predicted values on the test set are , where is the number of samples in the test set. The conditional PDF of prediction errors estimated on the validation set can be used to approximate that on the test set, under the assumption that both sets are drawn from the same distribution, such as the following:

The bilinear interpolation is applied to , obtaining the conditional PDF estimation of the prediction error when the predicted value is .

The confidence level of the prediction interval is denoted as . For each predicted value , the two quantiles and need to satisfy Equation (7):

where is the degree of confidence; and are the lower and upper quantiles, respectively.

The calculation steps are as follows:

- (1)

- First, calculate the cumulative distribution function (CDF) based on the conditional PDF of prediction errors on the test set.

- (2)

- Then, solve the inverse of CDF to obtain the lower quantiles and upper quantiles .

- (3)

- Finally, the interval estimation of the prediction error on the test set with a confidence level of is , which satisfies the following:

3.5. Baseline Load on Test Set

The baseline load for the t-th period on the i-th day is calculated using the predicted baseline load value and the prediction error :

where is a random variable; therefore, the baseline load is also random.

4. Assessment of Load Reduction Potential

4.1. Probabilistic Model of Load Reduction Potential

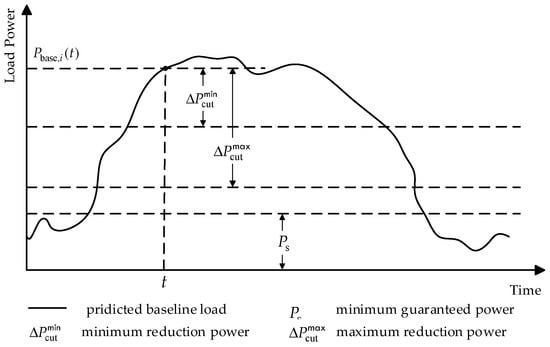

Interruptible load programs are implemented through contracts that establish the terms and conditions of load interruption with participating consumers. Before system operators making optimal dispatch decisions on load interruption, it is necessary to assess the load reduction potential. Typically, DR contracts specify the consumer’s minimum guaranteed power , minimum reduction power , and maximum reduction power . These quantities in DR contracts are illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Illustration of quantities in DR contracts.

If the load reduction potential in the t-th period is denoted by , it should satisfy the two inequality constraints shown in

where the first inequality indicates that the reduction potential should be between the minimum and maximum reduction power, and the second inequality indicates that the reduction potential should not exceed the difference between the baseline load and the minimum guaranteed power. Solving the above inequality yields the calculation equation for the load reduction potential during the t-th period as

From Equation (13), it can be seen that the load reduction is categorized into three states: (1) the load reduction potential is zero; (2) the lower limit of the load reduction potential is the minimum reduction power, and the upper limit is the difference between the baseline load and the minimum guaranteed power; (3) the lower and upper limits of the load reduction potential are the minimum reduction power and maximum reduction power, respectively.

The calculation of the lower limit of the load reduction potential, , is as follows:

The calculation of the upper limit of the load reduction potential, , is as follows:

Since the baseline load is uncertain and stochastic, the model of the load reduction potential shown in Equations (13)–(15) is essentially a probabilistic model.

4.2. Assessment of Load Reduction Potential Based on Monte Carlo Simulation

Since the conditional PDF of prediction errors is known, by iteratively sampling from the PDF, a Monte Carlo simulation method can be employed to easily estimate the probability distribution of the load reduction potential in the t-th period. The steps are as follows.

- (1)

- Set the number of simulations .

- (2)

- Initialize simulation count ; initialize state counters , counting for the three states shown in Equation (13).

- (3)

- According to the conditional PDF estimation of the prediction error when the predicted value is , use the inverse transform method to perform Monte Carlo sampling on prediction errors to obtain prediction error .

- (4)

- Calculate the baseline load for the t-th period according to Equation (11);

- (5)

- Update state counting according to Equation (16):

- (6)

- Calculate the lower limit and upper limit of the load reduction potential, i.e., and , according to Equation (14) and Equation (15), respectively.

- (7)

- Let , and check if holds: if yes, go to step (3); otherwise, go to step (8).

- (8)

- Calculate the probability distribution of load reduction potential :

- (9)

- Calculate the probability distribution of the lower and upper limits of load reduction potential:

- (a)

- Probability distribution of the lower limit of load reduction potential

The lower limit of the load reduction potential is a discrete random variable with two possible scenarios: the load reduction potential is zero or the load reduction potential is . The probability that the load reduction potential is zero is , and the probability that the load reduction potential is is .

- (b)

- Probability distribution of the upper limit of load reduction potential

The upper limit of the load reduction potential is a discrete–continuous hybrid random variable with three possible scenarios: the load reduction potential is zero, the load reduction potential is , and the load reduction potential is (with its value ranging between and ).

In Scenario 1, the upper limit of the load reduction potential is zero, with a probability of .

In Scenario 2, the upper limit of the load reduction potential is the random variable , with a probability of .

In Scenario 3, the upper limit of the load reduction potential is , with a probability of .

Based on , by eliminating from Scenario 1 and Scenario 3, the histogram of the upper limit of the reduction potential between and can be obtained.

5. Case Study

An industrial power consumer in Anhui, China is used as an example. To predict its baseline load at 11:00 a.m. on 6 August 2024, the consumer’s historical electricity consumption data for the past 14 months are used, and the data from weekends, holidays, and the DR days in which the consumer participated are excluded. Thus, the final data size at 11:00 a.m. is 305. The number of similar days is 10, and the rolling window method is applied to form the sample set, which includes 295 samples, with the first 70% of the data used as the training set, the middle 15% as the validation set, and the last 15% as the test set.

In the CNN model, the Adam optimization algorithm is employed, with the maximum number of training epochs set to 50 and the mini-batch size fixed at 10. The initial learning rate is initialized at 0.008 and adjusted using a piecewise learning rate schedule, where the learning rate is reduced by a factor of 0.01 every eight epochs. To enhance the training stability and generalization capability, the training samples are shuffled at the beginning of each epoch. Furthermore, in the assessment of the load reduction potential, 1,000,000 Monte Carlo simulations are performed

The proposed method was implemented in MATLAB (Version 23.2; Release name 2023b; The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) and tested on a computer with an Intel Core i7-10510U CPU and 16 GB RAM, without the use of GPU acceleration. The computation time was approximately 80 s, with most time consumed by the CNN model training process.

5.1. Comparison Prediction Results by CNN Method and Average Method

The CNN used in this case study consists of the input layer, convolutional layer, activation layer, dropout layer, fully connected layer, and regression layer. Pooling layers are omitted to prevent temporal compression, as pooling operations (e.g., MaxPooling) may discard fine-grained temporal features critical for regression tasks. Instead, all convolutional layers employ same padding and unit strides to preserve the full temporal resolution of the input sequence.

Additionally, the parameters of the CNN architecture are optimized through a systematic design procedure considering both the characteristics of the time-series data and the complexity of the regression task. A three-layer convolutional structure with progressively decreasing filter numbers and shrinking kernel sizes is adopted to enable hierarchical, multi-scale feature extraction while maintaining computational efficiency. This optimized configuration enhances the model’s ability to capture both broad and localized temporal patterns essential for accurate regression outcomes.

The structural parameters of the CNN model are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Structural parameters of the CNN model in the case study.

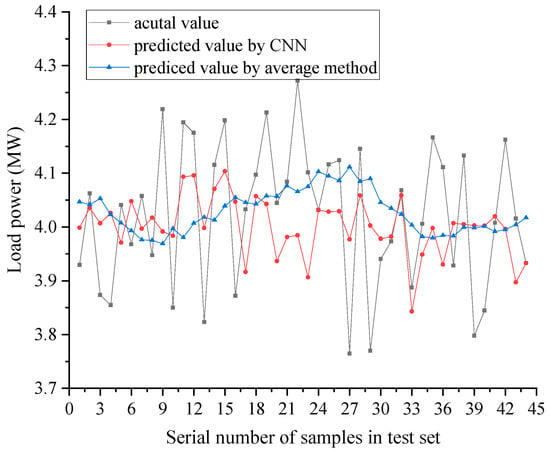

Taking the baseline load prediction at 11 a.m. every day on the test set as an example, the prediction results by the CNN method and the average method, and the actual value of load are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Comparison of prediction results between the CNN method and the average method.

The indices of point prediction error, Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) [24], by the two prediction methods are shown in Table 2. As can be seen from Figure 7 and Table 2, the prediction results of the CNN method are superior to those of the average method, primarily because the former can better capture the nonlinear relationship between the output and input variables of the prediction model. Therefore, the remainder of this paper only studies the probabilistic analysis of the baseline load prediction error based on the CNN model.

Table 2.

Comparison of prediction error indices between CNN method and average method.

5.2. Probabilistic Analysis of Baseline Load Prediction Error Based on CNN

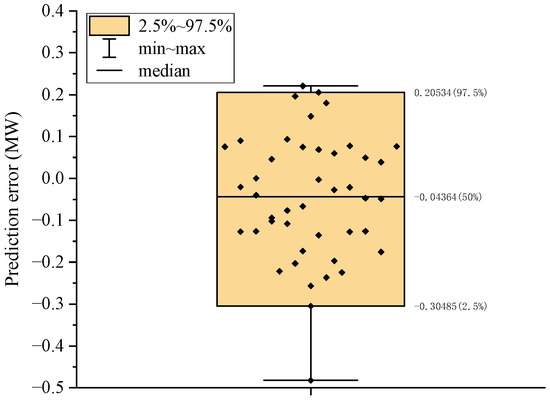

- (1)

- Marginal PDF of prediction errors

The box plot of the prediction errors by the CNN method on the validation set is shown in Figure 8. The maximum and minimum prediction errors are 0.22077 MW and −0.48201 MW, respectively, while the mean and median prediction errors are −0.04709 MW and −0.04364 MW, respectively.

Figure 8.

Box plot of prediction errors by CNN method on the validation set at 11:00 a.m.

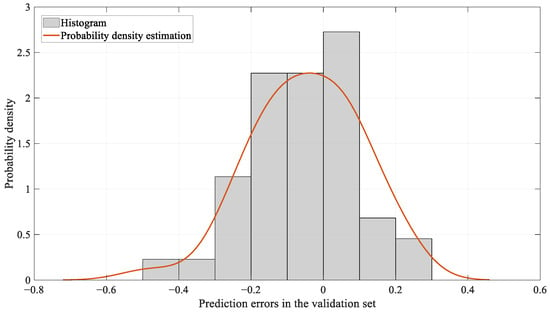

Based on the prediction errors from the empirical set, a nonparametric PDF estimation using a Gaussian kernel density function with a bandwidth of 0.0795 was performed to obtain the marginal PDF of the prediction errors, as shown in Figure 9. It can be observed that the PDF estimation of the prediction errors fits the prediction error histogram quite well.

Figure 9.

Marginal PDF estimation of prediction errors by CNN method.

- (2)

- Conditional PDF of prediction errors

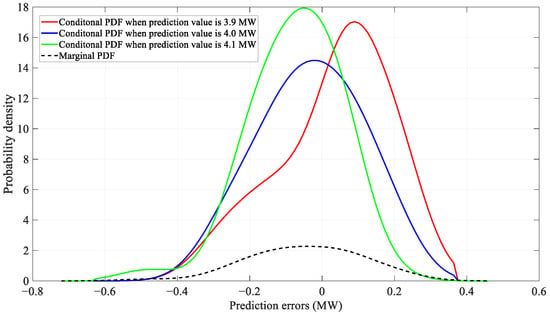

Figure 10 shows the conditional PDF of prediction errors, with bandwidths of 0.0437 and 0.0795 in the predicted value and error dimensions, respectively. A key observation is the systematic shift in the peak of these conditional distributions relative to the marginal PDF, which is directly correlated with the magnitude of the predicted value. When the predicted power is 3.9 MW, the peak of the conditional PDF shifts distinctly to the right of the marginal PDF’s peak. This rightward shift indicates a positive error, meaning the model exhibits a systematic underestimation tendency when predicting lower load values. In contrast, when the predicted power increases to 4.1 MW, the peak shifts to the left, revealing a negative error and corresponding to a systematic overestimation tendency at higher load levels. At the intermediate predicted value of 4.0 MW, the peak aligns almost exactly with that of the marginal PDF, suggesting minimal conditional bias near this point. Furthermore, all three conditional PDFs are noticeably taller and narrower than the marginal PDF, reflecting a significant reduction in prediction uncertainty when conditioning on a specific predicted value.

Figure 10.

Comparison of marginal PDF and conditional PDF of prediction errors.

The confidence intervals of prediction errors under the confidence level of 95%, derived from the marginal PDF and the conditional PDF of the prediction errors, respectively, are shown in Table 3. The three predicted values in the table are the point prediction values for the test set. It can be seen that, under the same confidence level, the interval length derived from the conditional PDF shown in Table 3 is smaller than the that from the marginal PDF, indicating that the uncertainty is reduced.

Table 3.

Confidence intervals of prediction errors.

- (3)

- Analysis of the prediction interval of baseline load

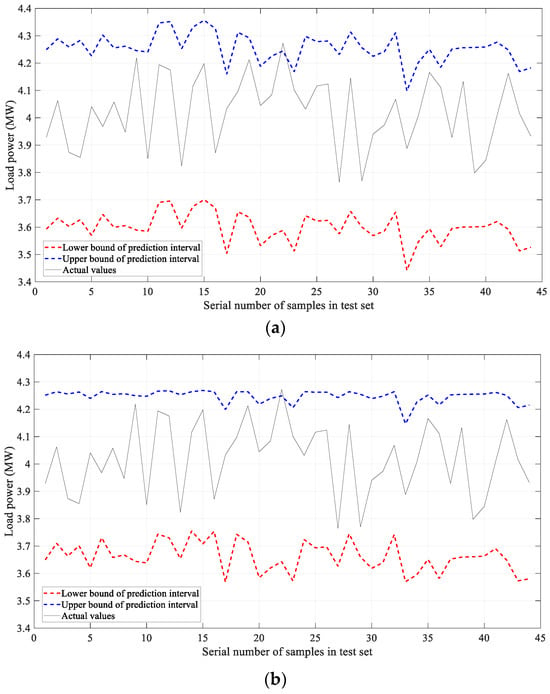

The prediction intervals with a confidence level of 95%, derived from the marginal and the conditional PDF of the prediction errors, respectively, are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Prediction intervals with a confidence level of 95%. (a) Prediction intervals by using the marginal PDF of prediction errors. (b) Prediction intervals by using the conditional PDF of prediction errors.

The performance indices of the prediction intervals, prediction interval coverage probability (PICP) [25] and prediction interval normalized average width (PINAW) [26], are presented in Table 4. Here, the PINAW is normalized with respect to mean of the actual load values on the test set, which is 4.0216 MW.

Table 4.

Performance indices of prediction intervals.

When using the marginal PDF of prediction errors, the PICP is 97.73%, and the PINAW, normalized by the mean of the actual load values on the test set, is 0.1632. When using the conditional PDF of prediction errors, the PICP remains at 97.73%, while the PINAW is 0.1453, decreased by 10.97%. This demonstrates that, when the conditional PDF is used to characterize the uncertainty of prediction errors, the PINAW is reduced while maintaining the same PICP, thereby improving the sharpness of intervals.

5.3. Load Reduction Potential Analysis

It is assumed that the DR contract stipulates a minimum guaranteed power of 0.6 MW, a minimum reduction power of 2.0 MW, and a maximum reduction power of 3.8 MW for the electricity consumer.

- (1)

- Probability distribution of load reduction states

Using the Monte Carlo simulation with 1,000,000 samples, the probability distribution of the consumer’s load reduction states at 11:00 a.m. was obtained, as shown in Table 5. Due to limited space in the paper, only the first 12 samples in the test set are displayed. It can be seen that the consumer’s load reduction is only in state 2 in most cases, never appears in state 0, and occasionally appears in state 3, so state 2 plays a leading role in its load reduction potential. According to Equation (13), the baseline load intervals corresponding to the three states of reduction potential are (0, 2.6) MW, [2.6, 4.4] MW, and (4.4, ∞) MW, respectively. And in the Monte Carlo sampling results, no baseline load values appear within (0, 2.6) MW; instead, a large number fall within [2.6, 4.4] MW, with very few appearing in (4.4, ∞) MW. Therefore, state 2 is dominant and state 1 never occurs.

Table 5.

Probability distribution of load reduction states at 11:00 a.m.

- (2)

- Probability distribution of lower and upper limits of load reduction potential

The probability distribution of the lower limit of the load reduction potential follows a discrete distribution. The probability distributions of the lower limit of load reduction potential for the first 12 samples in the test set are shown in Table 6. For the first 12 samples in the test set, the lower limit of the load reduction potential is 2 MW, and zero reduction potential will not occur.

Table 6.

Probability distribution of the consumer’s lower limit of load reduction potential at 11:00 a.m.

The probability distribution of the upper limit of the load reduction potential follows a discrete–continuous distribution. The probability distributions of the upper limit of the load reduction potential for the first 12 samples in the test set are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Probability distribution of the consumer’s upper limit of load reduction potential at 11:00 a.m.

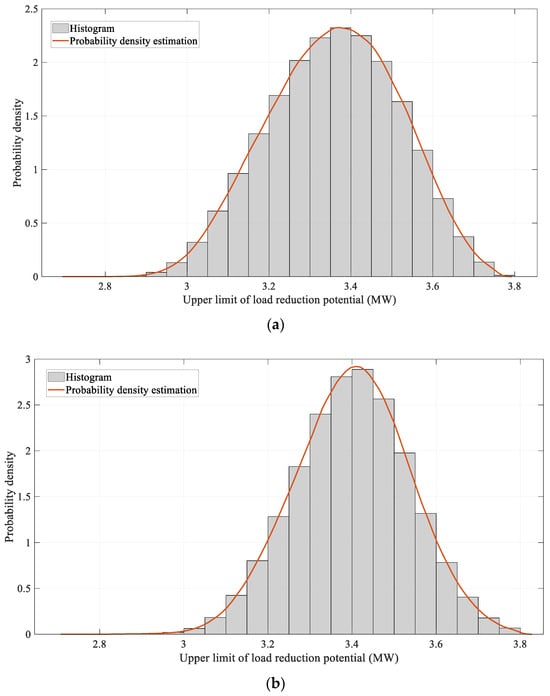

The normalized histograms for the upper limit of the load reduction potential for the first and sixth samples in the test set, within the interval of (2, 3.8) MW, are shown in Figure 12. From Table 7 and Figure 12, it can be seen that, for the first 12 samples in the test set, the upper limit of the load reduction potential mainly appears in the interval of (2, 3.8) MW, and the probability density of each point in this interval is different; the possibility of reaching 3.8 MW is very small, and there will be no situation where the upper limit of the load reduction potential is zero.

Figure 12.

Normalized histograms of the upper limit of load reduction potential within the (2, 3.8) MW interval. (a) The upper limit of load reduction potential for the 1st sample in the test set. (b) The upper limit of load reduction potential for the 6th sample in the test set.

The consumer’s lower and upper limits of load reduction potential at 11:00 a.m., when not considering the uncertainty of baseline load prediction, are shown in Table 8. Comparing this with Table 6 and Table 7 and Figure 12, ignoring the uncertainty of baseline load prediction leads to a point estimation on the upper limit of the load reduction potential, without taking into account the possibility in the range 2–3.8 MW.

Table 8.

Consumer’s lower and upper limit of load reduction potential at 11:00 a.m. without considering the uncertainty of baseline load prediction.

To assess the generalizability of the model beyond the detailed analysis at 11:00 a.m., we have evaluated its performance across multiple representative time periods, including the peak and off-peak periods. The results indicate that the primary conclusions drawn from the 11:00 a.m. case—specifically, the consistent dominance of probability of the load reduction potential in the second state and the reliable coverage of the prediction intervals—hold true throughout the day.

6. Conclusions

The main purpose of this paper was to analyze the uncertainty of forecasting baseline load rather than just improve prediction accuracy; on this basis, we modeled and assessed the load reduction potential in DR programs. The following conclusions are obtained through the analysis of case studies:

- (1)

- The CNN method can capture a complex nonlinear relationship between the loads at the same period on similar days before the calculation day and the load at the same period on the calculation day, so its prediction results are better than the average method. MAPE decreased from 0.0297 to 0.0273 and RMSE decreased from 0.1364 MW to 0.1297 MW in this case.

- (2)

- The proposed prediction error analysis method based on the conditional PDF can reflect the uncertainty of prediction results; it reduced the PINAW from 0.1632 to 0.1453 while maintaining the same PICP in the prediction interval. That is, it can improve the sharpness of the prediction interval.

- (3)

- The probabilistic model of the load reduction potential takes into account the uncertainty of baseline load prediction and the terms on interruptible loads in DR contracts, which can provide decision makers more useful information about the load reduction potential, e.g., the probability that the load reduction potential is dominant in the second state.

- (4)

- The Monte Carlo simulation can assess the load reduction potential and determine the probability distributions of the load reduction states, as well as the lower and upper limits of the load reduction potential, thus helping decision makers make better choices.

Based on the methodology developed in this paper, several promising directions for future research are identified. Firstly, although the probabilistic prediction model presented herein is based on a CNN architecture, the proposed framework for uncertainty quantification is general. It can be extended to other data-driven forecasting methods (e.g., transformer-based models and graph neural networks) or hybrid physics-informed models to analyze the uncertainty of their prediction results, enabling a comparative study on the robustness of uncertainty estimates across different model architectures.

Secondly, and more importantly, the proposed probabilistic assessment framework for load reduction potential can be further developed to address key technical challenges in DR settlement. The current deterministic settlement, based on a single baseline estimate, is often contentious. A direct and valuable extension of this work is to develop a probabilistic settlement mechanism that incorporates the probabilistic model of load reduction potential provided by our method. This mechanism could, for instance, calculate fair consumer compensation or incentives based on the likelihood of actual load reduction, thereby enhancing the fairness and market efficiency of DR programs.

Finally, the current model validation is based on an individual consumer case, and its generalizability to aggregated or heterogeneous consumer groups requires further investigation. Future work will focus on testing and extending the proposed framework to multi-consumer scenarios.

Author Contributions

Methodology, X.Q.; software, X.Q., M.G. and H.L.; validation, M.G., F.H. and H.L.; data curation, F.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G. and H.L.; writing—review and editing, X.Q.; Conceptualization, X.Q. and F.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Project of State Grid Anhui Electric Power Co., Ltd. (No. B312N0240009).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Feng Huang was employed by the Lu’an Power Supply Company of State Grid Anhui Electric Power Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, Y.; Xu, P.; Chu, Y.; Li, W.; Wu, Y.; Ni, L.; Bao, Y.; Wang, K. Short-term electrical load forecasting using the Support Vector Regression (SVR) model to calculate the demand response baseline for office buildings. Appl. Energy 2017, 195, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, F.; Bai, L. Power load forecasting method based on demand response deviation correction. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 148, 109013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Huang, R.; Cui, C.; Towey, D.; Zhou, L.; Tian, J.; Wang, J. Short-Term Electricity-Load Forecasting by deep learning: A comprehensive survey. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 154, 110980. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, P.; Xu, F.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, C.; Peng, X.; Zhao, J.; Li, K.; Wang, F. Graph convolutional network-based aggregated demand response baseline load estimation. Energy 2022, 251, 123847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Islam, S.N.; Mahmud, M.A.; Haque, M.E.; Dong, Z.Y. Energy forecasting in smart grid systems: Recent advancements in probabilistic deep learning. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2022, 16, 4461–4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, O.; Andreadou, N.; Bertoldi, P.; Lucas, A.; Saviuc, I.; Kotsakis, E. Demand Response Impact Evaluation: A Review of Methods for Estimating the Customer Baseline Load. Energies 2022, 15, 5259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ai, Q.; Li, Z. Improving aggregated baseline load estimation by Gaussian mixture model. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmouatamid, A.; Ouladsine, R.; Bakhouya, M.; Zine-Dine, K.; Khaidar, M. A Control Strategy Based on Power Forecasting for Micro-Grid Systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Smart Cities Conference (ISC2), Casablanca, Morocco, 14–17 October 2019; pp. 735–740. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Li, C.; Li, M.; Liu, F.; Taukenova, M. An overview of deterministic and probabilistic forecasting methods of wind energy. iScience 2023, 26, 105804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhuge, C.; Shao, C.; Wang, P.; Yang, X.; Wang, S. Short-term electric vehicle charging demand prediction: A deep learning approach. Appl. Energy 2023, 340, 121032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harikrishnan, G.R.; Sreedharan, S.; Nikhil Binoy, C. Advanced short-term load forecasting for residential demand response: An XGBoost-ANN ensemble approach. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 242, 111476. [Google Scholar]

- Gassar, A.A.A. Short-Term Energy Forecasting to Improve the Estimation of Demand Response Baselines in Residential Neighborhoods: Deep Learning vs. Machine Learning. Buildings 2024, 14, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Fan, S. Probabilistic electric load forecasting: A tutorial review. Int. J. Forecast. 2016, 32, 914–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Abellón, M.C.; Fernández-Jiménez, L.A.; Guillamón, A.; Gabaldón, A. Applications of Probabilistic Forecasting in Demand Response. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Y.; Yu, J.; Rajagopal, R. Probabilistic baseline estimation based on load patterns for better residential customer rewards. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 100, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, P.; Mohajeryami, S.; Cecchi, V. Building a Better Baseline for Residential Demand Response Programs: Mitigating the Effects of Customer Heterogeneity and Random Variations. Electronics 2020, 9, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amasyali, K.; Olama, M. Gaussian Process Regression for Aggregate Baseline Load Forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2021 Annual Modeling and Simulation Conference (ANNSIM), Virtual, 19–22 July 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tehrani, N.H.; Khan, U.T.; Crawford, C. Baseline load forecasting using a Bayesian approach. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 15–18 May 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Yan, J.; Hu, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, N. Two-Stage Decoupled Estimation Approach of Aggregated Baseline Load Under High Penetration of Behind-the-Meter PV System. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 4876–4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gang, W.; Ling, Z.; Su, L.; Dai, H. An assessment and ranking method on demand response potential for urban-scale buildings based on the energy usage portrait. Energy 2025, 335, 138196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Li, Z.; Huang, C.; Ai, Q. Online transfer learning-based residential demand response potential forecasting for load aggregator. Appl. Energy 2024, 358, 122631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H. Customer baseline load estimation for virtual power plants in demand response: An attention mechanism-based generative adversarial networks approach. Appl. Energy 2024, 357, 122544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Shi, J. A novel CNN-LSTM-based forecasting model for household electricity load by merging mode decomposition, self-attention and autoencoder. Energy 2025, 330, 136883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, W.; Song, Q.; Li, X. Load forecasting method based on CNN and extended LSTM. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 2452–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Tian, Z.; Qiu, Y. Enhancing accuracy in point-interval load forecasting: A new strategy based on data augmentation, customized deep learning, and weighted linear error correction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 272, 126686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Xiao, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wen, R. Enhancing short-term net load forecasting with additive neural decomposition and Weibull Attention. Energy 2025, 322, 135486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.