A Systematic Review of Numerical Modelling Approaches for Cryogenic Energy Storage Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

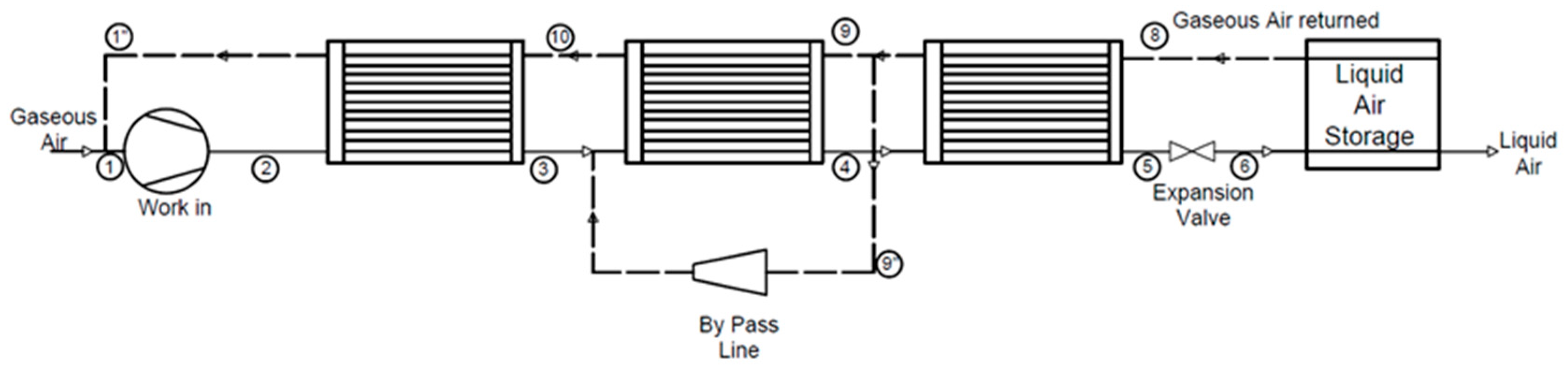

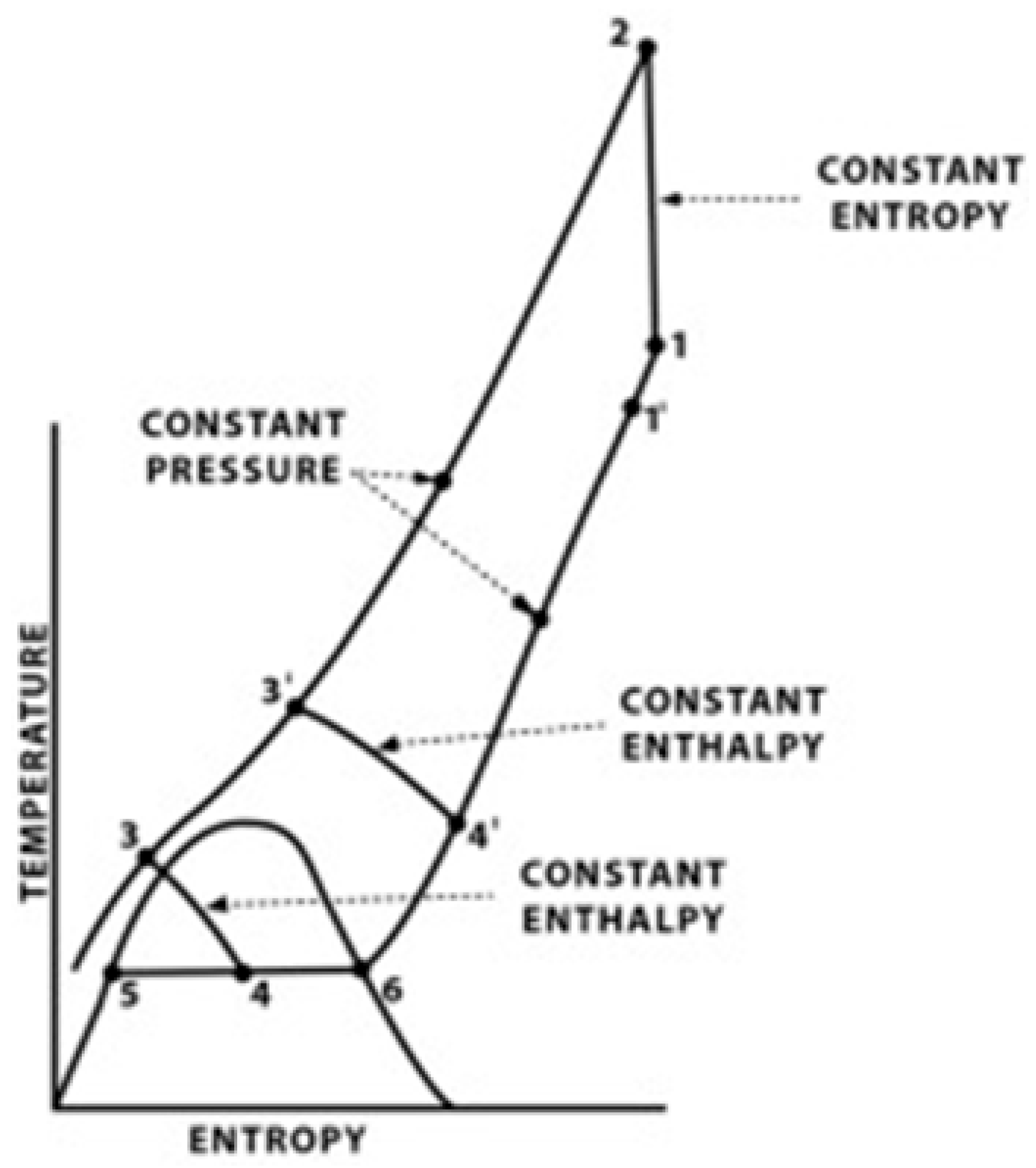

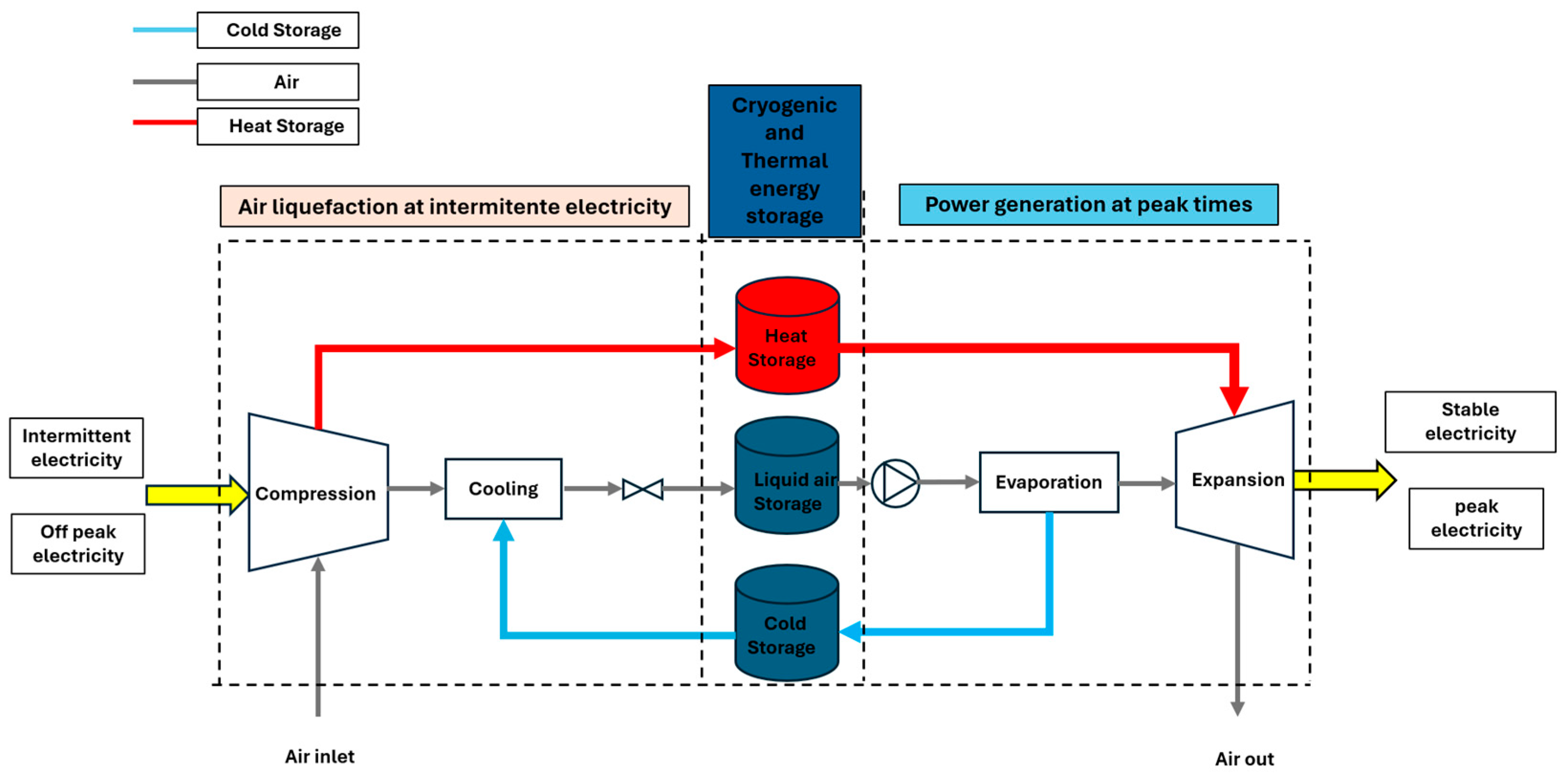

2. Fundamentals of Cryogenic Energy Storage

2.1. Thermodynamic Principles of Air Liquefaction

2.2. Principles of Cryogenic Systems

2.3. Energy Efficiency in Cryogenic Systems

3. Numerical Methods Applied to the Study of Cryogenics

4. Systematic Review of Numerical Studies on Cryogenic Energy Storage (CES)

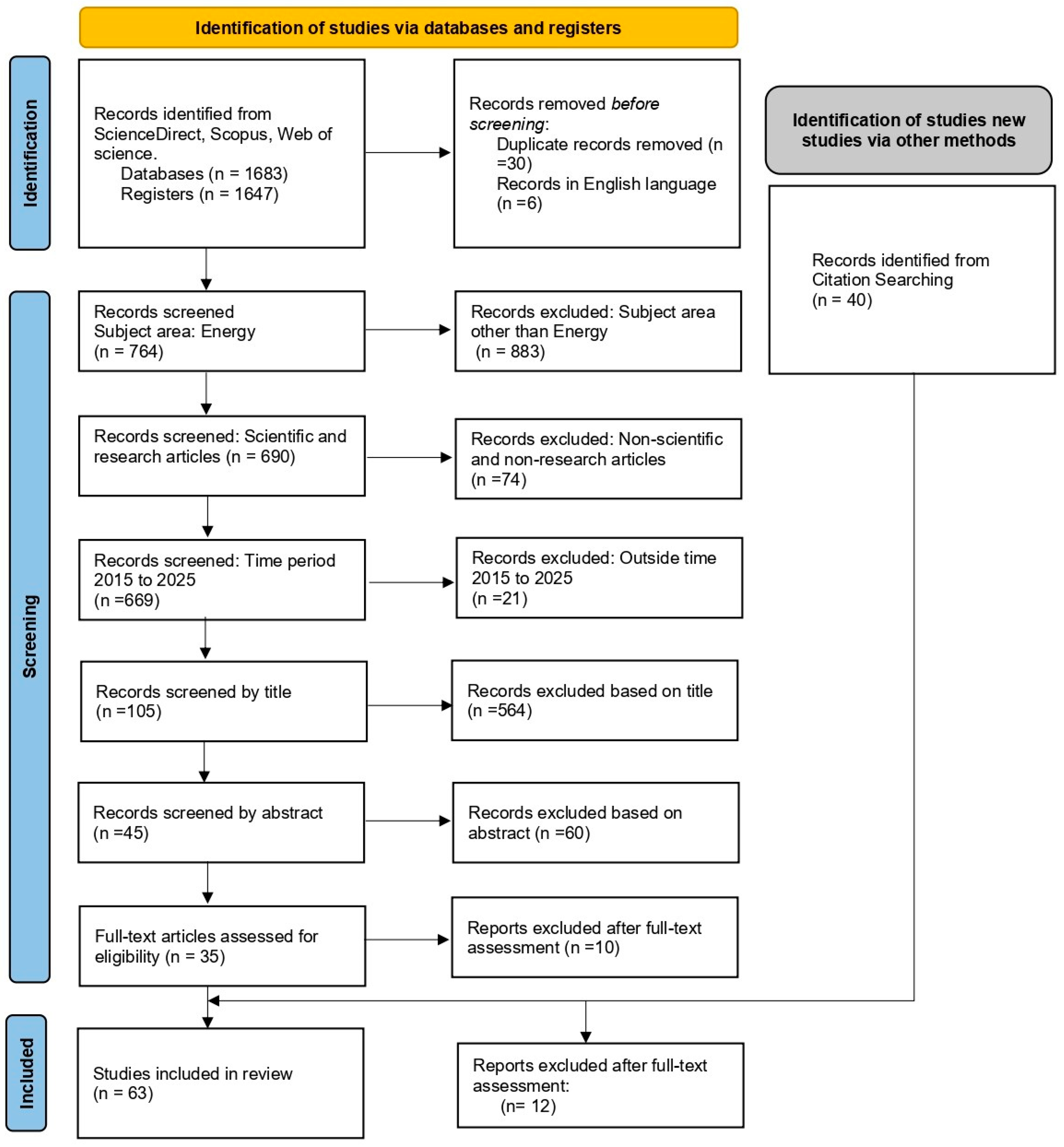

4.1. Methodology for the Systematic Retrieval and Selection of Scientific Publications

4.2. Classification of Numerical Studies

4.2.1. Global Thermodynamic Modeling Studies

4.2.2. Simulations of Specific Components

4.2.3. Transient Dynamic Modeling

4.2.4. Modeling and Performance of PB-TES Under LTNE Conditions

4.2.5. Multidimensional and Multi-Region Approaches in LAES

5. Challenges, Limitations, and Emerging Trends in Cryogenic Energy Storage Modeling

5.1. System-Level Limitations

5.2. Component-Level Limitations

5.3. Emerging Trends in CES Modeling

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Callaghan, O.; Donnellan, P. Liquid air energy storage systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 146, 111113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elalfy, D.A.; Gouda, E.; Kotb, M.F.; Bureš, V.; Sedhom, B.E. Comprehensive review of energy storage systems technologies, objectives, challenges, and future trends. Energy Strat. Rev. 2024, 54, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchi, A.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y.; Mancarella, P.; Sciacovelli, A. Liquid air energy storage (LAES): A review on technology state-of-the-art, integration pathways and future perspectives. Adv. Appl. Energy 2021, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, G.; Danieli, P.; Boatto, T.; Lazzaretto, A. Conceptual review and optimization of liquid air energy storage system configurations for large scale energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borri, E.; Tafone, A.; Romagnoli, A.; Comodi, G. A review on liquid air energy storage: History, state of the art and recent developments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 137, 110572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yvonne, L.; Mushtak, A.; Williams, R.A. Liquid air as an energy storage: A review. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2016, 11, 496–515. [Google Scholar]

- Semedo, A.; Garcia, J.; Brito, M. Cryogenics in Renewable Energy Storage: A Review of Technologies. Energies 2025, 18, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyekum, E.B.; Odoi-Yorke, F. Liquid air energy storage (LAES)—Systematic review of two decades of research and future perspectives. J. Energy Storage 2024, 102, 114022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damak, C.; Leducq, D.; Hoang, H.M.; Negro, D.; Delahaye, A. Liquid Air Energy Storage (LAES) as a large-scale storage technology for renewable energy integration—A review of investigation studies and near perspectives of LAES. Int. J. Refrig. 2020, 110, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüttermann, L.; Span, R. Investigation of storage materials for packed bed cold storages in liquid air energy storage (LAES) systems. Energy Procedia 2017, 143, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Wen, N.; Ding, Z.; Li, Y. Optimization of a cryogenic liquid air energy storage system and its optimal thermodynamic performance. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 15156–15173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; She, X.; Cong, L.; Zhang, T.; Li, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Tong, L.; Ding, Y. Thermodynamic study on the effect of cold and heat recovery on performance of liquid air energy storage. Appl. Energy 2018, 221, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Lv, H.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xing, X.; Ma, H. Cascade utilization of LNG cold energy by integrating cryogenic energy storage, organic Rankine cycle and direct cooling. Appl. Energy 2020, 277, 115570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. Large Scale Energy Storage CryoHub Developing Cryogenic Energy Storage at Refrigerated Warehouses as an Interactive Hub to Integrate Renewable Energy in Industrial Food Refrigeration and to Enhance Power Grid Sustainability Deliverable D8.1 Report on the Barriers to Uptake of Renewable and Low Carbon Technologies. 2017. Available online: https://ior.org.uk/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Chai, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Yue, L.; Yang, L.; Sheng, Y.; Chen, H.; Tan, C. Cryogenic energy storage characteristics of a packed bed at different pressures. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 63, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Bagdanavicius, A.; Barbour, E.R.; Pottie, D.L.; Garvey, S. Numerical analysis of the thermal performance of packed bed thermal energy storage in adiabatic compressed air energy storage systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 275, 126893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.S.; Kim, J.; You, H.; Chang, D. Experimental investigation of thermal stratification in cryogenic tanks. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2018, 96, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Olewski, T.; Véchot, L.N. Modeling of a cryogenic liquid pool boiling by CFD simulation. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2015, 35, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammad, M.; Liu, Y.; Olewski, T.; Véchot, L.N.; Mannan, M.S. Application of Computational Fluid Dynamics in Simulating Film Boiling of Cryogens. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 7548–7557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Ding, Z.; Wen, N. Numerical study on the thermodynamic performance of a packed bed cryogenic energy storage system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 214, 118903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanganeh, G.; Pedretti, A.; Haselbacher, A.; Steinfeld, A. Design of packed bed thermal energy storage systems for high-temperature industrial process heat. Appl. Energy 2015, 137, 812–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, C.; Dreyer, M.E.; Hopfinger, E.J. Pressure variations in a cryogenic liquid storage tank subjected to periodic excitations. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 66, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, E.; Agrawal, G.; Agarwal, D.K.; Pisharady, J.C.; Sunil Kumar, S. Effect of insulation thickness on pressure evolution and thermal stratification in a cryogenic tank. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 111, 1629–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandezi, M.S.; Naeenian, S.M.M. Investigation of an efficient and green system based on liquid air energy storage (LAES) for district cooling and peak shaving: Energy and exergy analyses. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incer-Valverde, J.; Hamdy, S.; Morosuk, T.; Tsatsaronis, G. Improvement perspectives of cryogenics-based energy storage. Renew. Energy 2021, 169, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; She, X.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y. Thermodynamic analysis of Liquid Air Energy Storage integrated with a serial system of Organic Rankine and Absorption Refrigeration Cycles driven by compression heat. Energy Procedia 2017, 142, 3440–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enayatizadeh, H.; Arjomand, A.; Tynjälä, T.; Inkeri, E. Cryogenic carbon capture design through CO2 anti-sublimation for a gas turbine exhaust: Environmental, economic, energy, and exergy analysis. Energy 2024, 304, 132244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, M.; Rodríguez-Antón, L.M.; Martinez-Arevalo, C.; Gutiérrez-Martín, F. Integration of liquid air energy storage into the Spanish power grid. Energy 2019, 187, 115965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabat, M.H.; Zeynalian, M.; Razmi, A.R.; Arabkoohsar, A.; Soltani, M. Energy, exergy, and economic analyses of an innovative energy storage system; liquid air energy storage (LAES) combined with high-temperature thermal energy storage (HTES). Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 226, 113486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Park, J.; Moon, I. Conceptual design and exergy analysis of combined cryogenic energy storage and LNG regasification processes: Cold and power integration. Energy 2017, 140, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umyshev, D.R.; Osipov, E.V.; Kibarin, A.A.; Korobkov, M.S.; Petukhov, Y.V. Analysis of Liquid Air Energy Storage System with Organic Rankine Cycle and Heat Regeneration System. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafone, A.; Pivetta, D.; Taccani, R.; Del Mondo, F.; Mazzoni, S.; Romagnoli, A. Multi-objective operational optimization of a multi-energy liquid air energy storage (LAES) in a hydrogen-based green energy hub in Singapore. J. Energy Storage 2025, 122, 116551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, R.F.; Pedro, H.T.; Koury, R.N.; Machado, L.; Coimbra, C.F.; Porto, M.P. Performance evaluation of various cryogenic energy storage systems. Energy 2015, 90, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Han, P.; Li, Y.; She, X. Thermodynamic analysis of a novel multi-layer packed bed cold energy storage with low exergy loss for liquid air energy storage system. Renew. Energy 2025, 240, 122271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Tan, H.; Shen, W.; Wen, N.; Sun, Y. Thermodynamic performance of a cryogenic energy storage system based on natural gas liquefaction. Energy Storage Sav. 2024, 3, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, W.; Chen, W.; Peng, H. Energy, conventional exergy and advanced exergy analysis of cryogenic recuperative organic Rankine cycle. Energy 2023, 268, 126648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Hong, Q.; Zhang, Y.X.; Lin, X.J.; Qiu, L.M.; Jiang, L. Cryogenic cold energy storage for liquefied natural gas utilization. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Liu, C.; Tong, L.; Yin, S.; Zhang, P.; Zuo, Z.; Wang, L.; Ding, Y. A cold thermal energy storage based on ASU-LAES system: Energy, exergy, and economic analysis. Energy 2025, 314, 134132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Ji, W.; Guo, L.; Gao, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, J. Thermo-economic analysis of the integrated system of thermal power plant and liquid air energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2023, 57, 106233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, M.R.; Soltani, M. Innovative energy and exergy optimization in SOFC and liquid air energy storage systems for peak demand management. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manassaldi, J.I.; Incer-Valverde, J.; Mussati, S.F.; Morosuk, T.; Mussati, M.C. Optimization of liquid air energy storage systems using a deterministic mathematical model. J. Energy Storage 2024, 102, 113940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, S.; Morosuk, T.; Tsatsaronis, G. Cryogenics-based energy storage: Evaluation of cold exergy recovery cycles. Energy 2017, 138, 1069–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borri, E.; Tafone, A.; Romagnoli, A.; Comodi, G. A preliminary study on the optimal configuration and operating range of a ‘microgrid scale’ air liquefaction plant for Liquid Air Energy Storage. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 143, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, C.; Du, D.; Liu, W. Thermodynamic analysis and optimization of liquefied air energy storage system. Energy 2019, 173, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzi, G.L.; Manno, M.; Tolomei, L.M.; Vitali, R.M. Thermodynamic analysis of a liquid air energy storage system. Energy 2015, 93, 1639–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Wang, C.; Hu, Y.; Yang, M.; Xie, H. Optimal operation strategies of multi-energy systems integrated with liquid air energy storage using information gap decision theory. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 132, 107078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Wang, K.; Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q. Multi-objective optimization of thermodynamics parameters of a biomass and liquefied natural gas complementary system integrated with liquid air energy storage and two-stage organic Rankine cycles. Energy 2025, 314, 134171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manassaldi, J.I.; Incer-Valverde, J.; Morosuk, T.; Mussati, M.C.; Mussati, S.F. A novel optimization strategy for designing cryogenic energy storage systems. Energy 2025, 332, 136490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; She, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T.; Ding, Y. Thermo-economic multi-objective optimization of the liquid air energy storage system. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansarinasab, H.; Fatimah, M.; Khojasteh-Salkuyeh, Y. Performance improvement of air liquefaction processes for liquid air energy storage (LAES) using magnetic refrigeration system. J. Energy Storage 2023, 65, 107304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Tong, L.; Wu, P.; Wang, L. Visualization study on double-diffusive convection during a rollover in liquid energy storage tanks. J. Energy Storage 2024, 76, 109813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Sun, P.; Jiang, W.; Qin, X.; Li, P.; Huang, Y. Thermal stratification suppression in reduced or zero boil-off hydrogen tank by self-spinning spray bar. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 20158–20172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, W.; Ren, J.; Zhang, H.; Bo, Y.; Bi, M. Analysis of the interfacial instability and the patterns of rollover in multi-component layered system. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 126, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassemi, M.; Kartuzova, O. Effect of interfacial turbulence and accommodation coefficient on CFD predictions of pressurization and pressure control in cryogenic storage tank. Cryogenics 2016, 74, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, F.; Vesovic, V. A 1-D model for the non-isobaric evaporation of cryogenic liquids in storage tanks. J. Energy Storage 2025, 132, 117913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.Y.; Park, J.H.; Lee, J.I. Experimental investigation of tank stratification in liquid air energy storage (LAES) system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 202, 117841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Xu, C.; Qiu, M.; Shi, Q.; Kong, D.; Xin, T. Thermodynamic modeling and dynamic performance analysis of the liquid CO2 storage tank within the liquid CO2 energy storage system. J. Energy Storage 2025, 130, 117358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ji, S.; Sun, M.; Ding, X.; Zheng, N.; Duan, L.; Desideri, U. Whole process dynamic performance analysis of a solar-aided liquid air energy storage system: From single cycle to multi-cycle. Appl. Energy 2024, 373, 123938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Duan, L.; Ding, X.; Zheng, N. Dynamic performance analysis of the discharging process of a solar aided liquid air energy storage system. J. Energy Storage 2023, 73, 108891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.B.; Ahmadi, P.; Hanafizadeh, P.; Khanmohammadi, S. Dynamic simulation and tech-no-economic analysis of liquid air energy storage with cascade phase change materials as a cold storage system. J. Energy Storage 2022, 50, 104179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Ji, W.; Gao, Z.; Fan, X.; Wang, J. Dynamic characteristics analysis of the cold energy transfer in the liquid air energy storage system based on different modes of packed bed. J. Energy Storage 2021, 40, 102712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.; He, W.; Ahmad, A.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y. Integration of liquid air energy storage with wind power—A dynamic study. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 242, 122415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Bian, Y.; You, Z.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, X.; Peng, H.; Ding, Y.; She, X. Dynamic analysis of a novel standalone liquid air energy storage system for industrial applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 245, 114537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Lu, C.; Shi, X.; Du, D.; He, Q.; Liu, W. Numerical investigation of dynamic characteristics for expansion power generation system of liquefied air energy storage. Energy 2021, 226, 120372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; He, Q.; Cui, S.; Shi, X.; Du, D.; Liu, W. Evaluation of operation safety of energy release process of liquefied air energy storage system. Energy 2021, 235, 121403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciacovelli, A.; Vecchi, A.; Ding, Y. Liquid air energy storage (LAES) with packed bed cold thermal storage—From component to system level performance through dynamic modelling. Appl. Energy 2017, 190, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nield, D.A.; Kuznetsov, A.V. Local thermal nonequilibrium effects in forced convection in a porous medium channel: A conjugate problem. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1999, 42, 3245–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, S.; Borah, A.; Boruah, M.P.; Randive, P.R. Critical review on local thermal equilibrium and local thermal non-equilibrium approaches for the analysis of forced convective flow through porous media. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 132, 105889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sumaily, G.F.; Al Ezzi, A.; Dhahad, H.A.; Thompson, M.C.; Yusaf, T. Legitimacy of the Local Thermal Equilibrium Hypothesis in Porous Media: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2021, 14, 8114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, R.; La Seta, A.; Hemmingsen, C.S.; Desai, N.B.; Haglind, F. Numerical analysis of measures to minimize the thermal instability in high temperature packed-beds for thermal energy storage systems. J. Energy Storage 2024, 94, 112431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonomo, B.; Cascetta, F.; Manca, O.; Sheremet, M. Heat transfer analysis of rectangular porous fins in local thermal non-equilibrium model. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 195, 117237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Luo, F.; Xu, R.; Jiang, P.; Liu, H. Heat Transfer and Fluid Transport of Supercritical CO2 in Enhanced Geothermal System with Local Thermal Non-equilibrium Model. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 7644–7650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Li, R.; Ling, X.; Dong, H. Modeling on heat storage performance of compressed air in a packed bed system. Appl. Energy 2015, 160, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, F.; Vesovic, V. CFD modelling of the non-isobaric evaporation of cryogenic liquids in storage tanks. Appl. Energy 2024, 356, 122420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, N.; Tan, H.; Pedersen, S.; Yang, Z.; Qin, X. Numerical study on the cyclic cold storage performance in a solid-packed bed tank. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.; Farooq, S.; Karimi, I.A.; Banerjee, R. A CFD simulation study of boiling mechanism and BOG generation in a full-scale LNG storage tank. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2018, 115, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovidi, F.; Pagni, E.; Landucci, G.; Galletti, C. Numerical study of pressure build-up in vertical tanks for cryogenic flammables storage. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 161, 114079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yan, T.; Wang, J.; Ye, S.; Li, Y.; Zhuan, R.; Wang, B. CFD investigation on thermodynamic characteristics in liquid hydrogen tank during successive varied-gravity conditions. Cryogenics 2019, 103, 102973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Modeling Approach | System/Scale | Key Results/Performance Indicators | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manassaldi et al. [41] | Deterministic optimization | LAES | +63% cycle efficiency; +48% liquid air production | Eliminated one component, simplifying system configuration |

| Hamdy et al. [42] | Thermodynamic modeling with exergy recovery | LAES with direct expansion & ORC | Round-trip efficiency (RTE) 40%; +25% discharge power | Significant increase in exergetic efficiency |

| Borri et al. [43] | Cycle comparison (Linde, Claude, Kapitza) | Microgrid-scale LAES | Specific energy consumption: 520–560 kWh/t | Two-stage Kapitza cycle with pressurized phase separator most efficient; highlights heat exchanger importance |

| Qing et al. [44] | Thermodynamic & exergy analysis | 4-stage compression-expansion LAES | Optimal storage/discharge pressures: 15 MPa/7.1 MPa | Component adiabatic efficiencies strongly influence overall performance |

| Guizzi et al. [45] | Integration of cold and heat storage | Stand-alone LAES | Efficiency ≈ 50% | Cryoturbine isentropic efficiency critical (>70%) |

| Yan et al. [46] | Multi-energy operational strategies | LAES in hybrid systems | Cost reduction up to 6.82% | Substitution of grid electricity with natural gas most economical during high-price periods |

| Duan et al. [47] | Multi-objective optimization + genetic algorithms & neural networks | Hybrid biomass–LNG–LAES system | Minimized exergy cost and carbon intensity | Demonstrates effectiveness of hybrid optimization frameworks |

| Manassaldi et al. [48] | Nonlinear optimization | LAES | +20% efficiency; +21% liquid air production | Highlights potential of advanced optimization frameworks |

| Liang et al. [49] | NSGA-II multi-objective optimization | LAES (high-budget investment) | Efficiency +9–14%; exergy destruction −16% | Trade-offs between efficiency, capital cost, and exergy destruction |

| Ansarinasab et al. [50] | Integration of Active Magnetic Refrigeration (AMR) | LAES | Specific energy consumption reduced by up to 11.2% | Kapitza-AMR achieved lowest levelized cost of product |

| Tan et al. [11] | Steady-state modeling + genetic algorithm | LAES | RTE 53.33%; liquefaction ratio 86.96%; compressor power −10.02% | Demonstrates effective optimization under steady-state conditions |

| Reference | Component/Focus | Methodology | Key Findings/Observations | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zuo et al. [51] | Cryogenic tanks | Experimental (Schlieren visualization) | Identified four-stage rollover process; higher heat flux accelerates interface collapse; small density differences increase rollover susceptibility | Analytical correlations support safety and efficiency improvements |

| Zuo et al. [52] | Liquid hydrogen tanks | Experimental (self-actuated rotating spray bars) | Reduced thermal non-uniformity by 41.2%, decreased cooling time by 50% and system weight by 76.5% | Demonstrates potential of active stratification control |

| Sha et al. [53] | Stratified NaCl solutions | Experimental | Identified W-shaped, Y-shaped, and hourglass convection patterns; higher buoyancy ratios did not necessarily increase rollover risk | Relevant to multi-component cryogenic systems |

| Kassemi et al. [54] | Cryogenic tanks | CFD (Sharp Interface & VOF) | Laminar models matched experiments; conventional turbulence models underestimated stratification and pressurization | Highlights need for improved turbulence representation |

| Huerta et al. [55] | Cylindrical tanks | CFD (OpenFOAM) | Vertical stratification suppressed buoyancy-driven convection; non-isobaric regime showed interface-driven heat transfer; bottom heating enhanced mixing | Boundary conditions critically influence tank design |

| Heo et al. [56] | Liquid air tanks | Experimental | Destratification times 8–29% shorter than LN2; times increased by factor of 2.4 at higher pressures | Stratification can be exploited to reduce BOG and improve efficiency |

| Kang et al. [17] | Liquid air tanks | Experimental | Strong correlation between fill level and stratification; BOR 0.05–0.34%/min, lower than homogeneous models | Confirms strategic use of stratification |

| Liu et al. [18] | Microgravity tanks | Experimental/CFD | Tank rotation extended time to full stratification; ullage pressure increased by 18.27% with evaporation | Microgravity effects relevant for space storage |

| Joseph et al. [23] | Cryogenic tanks | Experimental | Reduced insulation increased heat ingress and pressurization; solar radiation and wind strongly affected pressure evolution | Highlights importance of external conditions |

| Study | System or Process Modelled | Methodology | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dai et al. [57] | Liquid CO2 storage tank | Dynamic modelling of two-phase operation | Reduced pressure fluctuations; decrease in effective storage density (ESD); cooling strategy proposed for mitigation. |

| Zhou et al. [58,59] | Solar-aided LAES (SALAES) | Dynamic modelling of discharge and solar variability | Solar fluctuations and molten salt depletion significantly affect cycle/exergy efficiency; dynamic modelling enables rapid load adjustment and fault mitigation. |

| Mousavi et al. [60] | LAES with PCM-packed beds | Transient thermo-economic modelling | ~5.9% efficiency penalty due to transient PCM behaviour; payback period of 6.2 years; optimisation depends on PCM layering and melting temperature. |

| Guo et al. [61] | LAES cold-packed bed | Transient dynamic modelling | Cold energy losses and interruptions reduce efficiency by ~16.8%; highlights need for transient-aware packed-bed design. |

| Liang et al. [62] | LAES–battery hybrid system | Transient modelling under fluctuating wind input | LAES stabilises fluctuations > 130 s; hybrid configuration more economically viable than batteries alone. |

| Wang et al. [63] | Standalone LAES with pebble/rock beds | Dynamic modelling | Efficiency slightly lower than fluid-packed beds but industrially robust; cogeneration efficiency > 80%. |

| Cui et al. [64] | 12.5 MW expansion unit | Dynamic simulation | Segmented start-up reduces stabilisation time; enables frequency regulation within 20 s; valve delays negatively affect performance. |

| Lu et al. [65] | 500 kW expansion unit | Transient safety modelling | Rotor time constant and valve closing time are critical for limiting overspeed and ensuring safe shut-down. |

| Sciacovelli et al. [66] | Packed-bed LAES pilot plant | Validated algebraic-differential dynamic model | Thermal front propagation degrades performance; importance of thermal management and packed-bed design. |

| Study | System or Process Modelled | Methodology | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buonomo et al. [71] | Porous fins with adiabatic tips | LTNE modelling of solid–fluid temperature profiles | LTE assumption overestimates heat transfer for low Biot numbers; LTNE approach allows optimization of fin design considering phase temperature differences. |

| Zhang et al. [72] | CO2 in enhanced geothermal systems | LTNE numerical modelling | LTNE significantly affects production temperature and thermal breakthrough time; higher volumetric heat transfer coefficients amplify LTNE effects; highlights importance of accounting for phase temperature differences. |

| Peng et al. [73] | PB-TES with PCM particles in CAES systems | Numerical analysis | Higher porosity reduces thermal capacity and charging efficiency; smaller particles improve efficiency without major effect on total storage capacity; multiple storage materials and higher inlet pressures enhance performance. |

| Tan et al. [20] | Solid cryogenic packed beds | 3D CFD modelling | Cold storage efficiency relatively insensitive to porosity; pressure drop increases with decreasing porosity; basalt packing material achieves highest cold storage (77.69%) and cold exergy efficiency (75.21%). |

| Study | System or Process Modelled | Methodology | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Huerta et al. [55] | Cryogenic liquid storage tanks | Transient 1-D model for non-isobaric evaporation | Predicts time-dependent liquid/vapor temperatures, tank pressure, liquid volume, and evaporation rates; simplifies natural convection; calibrated 1-D models achieve accuracy comparable to CFD with >1000× faster computation. |

| Huerta et al. [74] | Cylindrical cryogenic tanks | 2-D CFD model with axial symmetry | >96% of heat through vapor phase transferred directly to liquid-vapor interface; wall-induced natural convection dampened by thermal stratification; bottom heating effectively circulates and warms liquid bulk. |

| Wen et al. [75] | Packed Bed Cold Storage (PBCS) in LAES | Transient 2-D model incorporating fluid-solid temperature differences | Superficial fluid velocity and number of storage cycles strongly affect cyclic exergy efficiency; emphasizes importance of detailed internal dynamics analysis. |

| Saleem et al. [76] | Full-scale LNG storage tanks | 2-D axisymmetric CFD with VOF and Lee phase-change model | Surface evaporation dominates in well-insulated tanks; nucleate boiling occurs only with poor insulation; small-scale experiments cannot fully replicate full-scale dynamic behavior. |

| Ovidi et al. [77] | Industrial cryogenic tanks (100 m3) | 3-D CFD with VOF, boundary conditions from 1-D insulation model | Captures vaporization and condensation; analyzes effects of fluid type, filling level, insulation on stratification and pressurization; supports large-scale operational decision-making. |

| Wang et al. [78] | Liquid hydrogen tanks under variable gravity | 3-D CFD with multicomponent effects and helium diffusion | Acceleration changes affect liquid coverage and vapor condensation; detailed 3-D modelling necessary to capture complex multiphase and microgravity phenomena accurately. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Semedo, A.; Garcia, J.; Brito, M. A Systematic Review of Numerical Modelling Approaches for Cryogenic Energy Storage Systems. Processes 2026, 14, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010051

Semedo A, Garcia J, Brito M. A Systematic Review of Numerical Modelling Approaches for Cryogenic Energy Storage Systems. Processes. 2026; 14(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleSemedo, Arian, João Garcia, and Moisés Brito. 2026. "A Systematic Review of Numerical Modelling Approaches for Cryogenic Energy Storage Systems" Processes 14, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010051

APA StyleSemedo, A., Garcia, J., & Brito, M. (2026). A Systematic Review of Numerical Modelling Approaches for Cryogenic Energy Storage Systems. Processes, 14(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010051