Abstract

To achieve the upcycling of annually upsurging lignocellulosic wastes, the artificial humification of furfural residue is investigated under hydrothermal conditions with the objective of producing a high-concentration nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium (NPK) suspension fertilizer. Through orthogonal analysis, process conditions are optimized as a liquid-to-solid (aqueous KOH to furfural residue) ratio of 15, a reaction time of 5 h and a hydrothermal temperature of 160 °C. Subsequently, we screen out a formulation of suspension agents to stabilize the alkaline leachate, in which 0.50% sodium lignosulfonate, 0.20% xanthan gum and 0.05% potassium sorbate are incorporated via wet ball-milling. The Herschel–Bulkley equation well fits the rheological characteristics of the resulting suspension fertilizer with R2 value exceeding 0.99. This suspension system is thus determined as one pseudoplastic non-Newtonian fluid. Due to higher static viscosity, it demonstrates superior anti-agglomeration capacity within a temperature range of 15–55 °C, while flowing smoothly through pipes during high-speed spraying onto the soil relied on its shear thinning. These findings provide novel insights for the high-value utilization of bio-waste and the development of new fertilizers with less consumption of energy and water.

1. Introduction

Furfural residue is a solid waste generated after the high-temperature acid hydrolysis of corn cobs to produce furfural. For every ton of furfural produced, 12–15 tons of furfural residue are generated [1]. Furfural residue is composed of approximately 45% cellulose and 35% lignin, with a small amount of hemicellulose [2]. As an acidic and organic-rich solid waste, China produces an estimated 7.8 million tons of furfural residue annually [3]. Furfural residue contains large molecular weight lignocellulose with complex components and low solubility; thus, it can hardly be directly utilized, for instance, given its little nutritional activity, as fertilizer [4]. Currently, it is mainly disposed of by burning or piling up, which not only causes pollution to land, water and air, but also wastes these considerable biomass resources [5].

Humic substances comprise a series of amorphous and polydispersed organic compounds originating from the complex bio- and physico-chemical degradation of plant and animal residues. These substances are ubiquitous in soil, peat and lignite [6]. Based on their solubility in alkaline or acidic media, humic substances are classified into alkali-soluble humic acid (HA), ampho-soluble fulvic acid (FA) and ampho-insoluble humin (HM), with HA recognized as the principal bioactive component [7]. HA can improve soil texture while nourishing rhizosphere-beneficial microorganisms, thereby facilitating plant uptake of mineral nutrients [8]. The primary source of HA is extraction from lignite, a low-rank coal. Although deposits of lignite are abundant, they constitute a finite and non-renewable resource. Therefore, renewable biomass such as lignocellulosic material has been extensively explored as a substitute for hydrothermal conversion to HA [9]. The degradation of lignocellulose usually yields a range of low molecular-weight compounds, including monosaccharides, organic acids and phenolic derivatives, which serve as essential precursors in the subsequent HA formation [10]. Meanwhile, an alkaline environment is required to move forward this artificial humification process [11]. In the process of extracting humic acid for the purpose of organic fertilizers, KOH is often used as the alkali agent. K+ remains in the alkali solution and provides nutrients for plants together with the obtained humic acid [12].

Converting the lignocellulose in discarded biomass into humic acid-containing fertilizers through hydrothermal technology not only helps save lignite resources, but also contributes to the low-carbon management of these wastes [7,9]. However, there is now a lack of studies on the preparation of humic acid-containing suspension fertilizers using waste cellulose resources. Concerned studies either mix and granulate commercial humus with mineral fertilizers, which incurs high energy consumption for evaporation and waste of water [2,12,13], or the humus leachate is diluted and used as solution fertilizers, during which the issue of stability (anti-precipitation) after nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) fertilizers are introduced could be ignored [14]. Therefore, it is urgently necessary to develop a stable suspension fertilizer with high nutrient concentration based on humic acid leachate after alkali hydrothermal treatment of lignocellulose [15]. But before that, it is necessary to clarify the mechanism behind the formation of humic acid from waste lignocellulose to conduct the alkali hydrolysis towards a higher yield of humic acid. In addition, an interface-suitable and rheology-feasible suspension system should also be obtained through optimization of the subsequent nutrient formulation. Then, the economy can be improved due to high nutrient concentration during storage and transportation. Finally, this cost-effective suspension fertilizer can be smoothly sprayed out from the pipeline without sedimentation and clogging during fertilization.

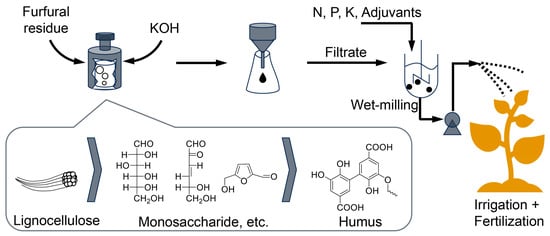

Herein, we employ potassium hydroxide-assisted hydrothermal treatment of furfural residue to generate humic acid. On this basis, the alkali leachate is used to prepare a humic acid-containing suspension fertilizer, and the accompanying water is directly contributed to the terminal irrigation (Scheme 1). Through elemental and structural analysis, extracted humic acid is compared with commercial lignite humic acid to assess the feasibility of agricultural applications. An optimal suspension agent scheme was determined by investigating particle size distribution, ξ potential and thixotropy. The influence of temperature on the rheological properties of the suspension system was also evaluated, and the rheological results were fitted using the Herschel–Bulkley equation to account for the accessible “shear thinning” effect, which is crucial for available agricultural spraying. The byproducts of crop processing can be reactivated as an organic fertilizer to return carbon to the soil. Therefore, this technology, characterized by low cost, no organic solvents, low energy consumption and water conservation, is expected to digest biomass waste on a large scale in the future, thus contributing to the low-carbon cycle of global bioresources.

Scheme 1.

Furfural residue to humic acid-containing suspension fertilizer upon artificial humification.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Furfural residue was purchased from Xinlianxin Chemical Industry Group Co., Ltd., Xinxiang, China. A company in Inner Mongolia, China provided wet-process phosphoric acid with concentration of 30% P2O5 by weight. Commercial humic acid (CHA), potassium hydroxide, sulfuric acid, potassium dichromate, ferrous ammonium sulfate, urea, potassium chloride, sodium lignosulfonate (SL), potassium pyrophosphate (PP), sodium dodecylbenzene sulfonate (SDBS), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), xanthan gum (XG), sodium alginate (SA), polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), bentonite (Bent), sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (SCC) and potassium sorbate (PS) were all of analytical grade and purchased from Macklin, Shanghai, China. Deionized water with a resistivity of 18.25 MΩ·cm was used throughout.

2.2. Artificial Humification of Furfural Residue

Artificial humification experiments were conducted in 80 mL polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)-lined autoclaves placed in a drying oven. According to the design outlined in Table 1, 5 g of furfural residue and 2 g of urea were reacted with a 1.5 mol/L potassium hydroxide solution under varying conditions (liquid-to-solid ratio, reaction temperature and reaction time). After humification, the solid residue and alkaline hydrolysate were separated via vacuum filtration. The contents of HA and FA in the alkaline leachate were determined using the potassium dichromate oxidation titration method [16].

Table 1.

Factors and levels of orthogonal experiment.

HA determination: 2 g of the alkaline hydrolysate was mixed with 1 mL of 0.1 mol/L NaOH solution and diluted to 100 mL. Accurately transfer 5 mL of the dilution into a centrifuge tube and add 5 mL of 1 mol/L H2SO4 solution. After centrifuged at 3500 r/min for 10 min, the sediment at the bottom was collected as humic acid. The separated humic acid was then oxidized with concentrated sulfuric acid and potassium dichromate. The remaining potassium dichromate content was titrated with ferrous sulfate so that the content of HA was ultimately calculated.

FA determination: 2 mL of the filtered alkaline hydrolysate was transferred into a conical flask. Add an appropriate amount of water and conduct extraction in a boiling water bath for 2 h. The cooled solution was then filtered and diluted to 250 mL. The pH of 100 mL of this dilution was adjusted to 1.5 with 2 mol/L H2SO4 solution to ensure the full precipitation of possible HA. The supernatant was analyzed for FA content by a method similar to that used for HA determination, which involved potassium dichromate oxidation combined with ferrous sulfate titration as well.

An orthogonal experiment was employed to investigate the effects of parameters on the yield of target products (Table 1). For solid-phase analysis, the pH of the alkaline hydrolysate was adjusted to 1.00 using a 2 mol/L HCl solution to precipitate the humic acid. The resulting suspension was then centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 15 min with supernatant decanted. The collected humic acid precipitate was dried in a forced-air oven at 60 °C for 24 h and was defined as artificial humic acid (AHA).

2.3. Preparation of Humic Acid-Containing Suspension Fertilizer

Wet-process phosphoric acid and alkaline hydrolysate were mixed at a mass ratio of 5:1. Urea and potassium chloride were then introduced as supplementary N and K sources, respectively, with a mass ratio of N:P2O5:K2O = 1:1:1. The mixture was then combined with a dispersant, a thickener and an antimicrobial agent [17]. The blended slurry underwent a grinding for 15 min at a milling speed of 3000 rpm to finally obtain the humic acid-containing suspension fertilizer.

2.4. Characterizations

Elemental analysis (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and sulfur) of humic acid samples was performed using an elemental analyzer (Flash EA1112, Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Hesse, Germany). Their functional groups were analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Nicolet 6700, Nicolet Instruments Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, AXIS Ultra DLD, Kratos Corporation, Manchester, UK). The particle size distribution of the suspension fertilizers was determined using a Malvern Mastersizer 3000E laser diffraction particle size analyzer (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, UK). The ξ potential of the suspensions was measured using a DT-300 electroacoustic ξ potential analyzer (Dispersion Technology, Bedford Hills, NY, USA). The thixotropic loop and flow curves of fertilizers were investigated using a rheometer (HAAKE MARS iQ Air, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Parameter Optimization of Hydrothermal Humification

The yields of humic acid (HA) and fulvic acid (FA) after artificial humification treatment are summarized in Table 2. For each 5 g of furfural residue reacted, the humic acid yield ranged from 0.04 to 1.26 g, and the fulvic acid yield ranged from 0.57 to 1.16 g. Variance analysis (ANOVA) was performed as presented in Table 3 to assess the significance of the hydrothermal parameters on the yield of humic substance [14]. The liquid-to-solid ratio exhibited the most significant impact on humic substance yield, followed by hydrothermal time and reaction temperature. Regarding FA yield, the significance of influence is liquid-to-solid ratio > temperature > time. As for HA yield, their significance is slightly changed: liquid-to-solid ratio > time > temperature. Based on the recently proposed mechanism of artificial humification, small molecules such as organic acids produced from lignin decomposition, along with phenolic compounds and furan compounds, aggregate again to form humic substances (Scheme 1) [18]. Urea decomposes under hydrothermal conditions to produce NH3 and CO2. The released NH3 provides the necessary nitrogen source for the reaction system, enabling it to participate in the Maillard reaction and form nitrogen-containing humic acids.

Table 2.

Yields of humus from artificial humification.

Table 3.

Variance analysis of orthogonal experiment with humus yield as response (S: sum of squares; f: degrees of freedom; F: F-statistic).

KOH significantly accelerates the initial depolymerization and hydrolysis of cellulose by causing OH− to attack the glycosidic bonds, thereby reducing the reaction energy barrier. Increasing the liquid-to-solid ratio leads to sufficient active OH−, which promotes the degradation of lignin and the release of humification precursors, thereby boosting the humification process [19]. Hydrothermal time and temperature exert comparatively less influence on humic substance yield. Therefore, a shortened time of 5 h and a lowered temperature of 160 °C are selected from an economic perspective. A higher liquid-to-solid ratio of 15 is accordingly chosen though restraining the capacity of humus processing. In addition, the excessive water introduced would not increase the subsequent concentration energy consumption. In fact, these water sources do not need to evaporate at all. Instead, they directly provide a flowing substrate for the suspension fertilizer formulation and eventually participate in irrigation.

3.2. Characterization of Resulting Humic Acid

3.2.1. Elemental Analysis

Artificial humic acid (AHA) was prepared using the following conditions: furfural residue of 5 g, urea addition of 2 g, potassium hydroxide concentration of 1.5 mol/L, liquid-to-solid ratio of 15:1, hydrothermal time of 5 h and reaction temperature of 160 °C. Commercial humic acid (CHA) was also equally analyzed for comparison. As shown in Table 4, the carbon (C) content of CHA reaches 50.80%, and its oxygen (O) content reaches 30.80%, both higher than that of AHA. Both HAs possess equal hydrogen (H) or sulfur (S) content. Specifically, the nitrogen content of AHA is 2.85%, significantly higher than that of CHA. The higher oxygen content of CHA, along with its higher O/C ratio, suggests more oxygen-containing functional groups such as carboxyl groups (–COOH) and phenolic hydroxyl groups (–OH) compared to AHA [20]. The H/C ratio of AHA is slightly higher than that of CHA, indicating that its aromaticity and degree of unsaturation are slightly lower than that of CHA. The increased N in AHA is significantly related to the participation of urea in its humic transformation. The addition of nitrogen-rich compounds promotes the generation of nitrogen functional groups within the humic acid molecule, which can serve as a potential organic slow-release nutrient to alleviate nitrogen loss.

Table 4.

Elemental analysis of humic acids.

3.2.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

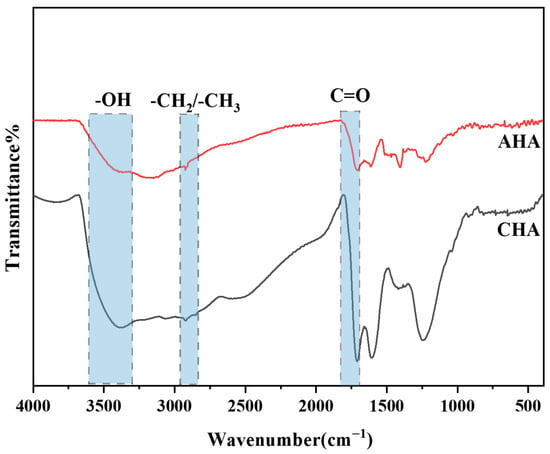

As shown in Figure 1, AHA and CHA exhibit similar infrared spectra. Both humic acids show strong absorption peaks at 1500 cm−1 and 1610 cm−1, which may originate from the stretching vibration of the skeletal C=C in their benzene ring structures. The presence of aromatic structures in AHA indicates the successful decomposition of lignin during the hydrothermal reaction [21]. In the range of 3370–3400 cm−1, both humic acids exhibit O-H stretching vibration peaks of hydroxyl groups, and at around 1710 cm−1, an absorption peak caused by C=O stretching vibration is also observed as a characteristic of –COOH structures. Both humic acids contain carbonyl and carboxylic acid groups, which coincides the structural characteristics of humic acids with multiple acidic functional groups. In the 2910–2930 cm−1 band, stretching vibration peaks of branched alkyl –CH2/–CH3 are observed [22]. The alkyl absorption intensities are similar, indicating similar branched structures and comparable stability in the two humic acids. Overall, the peak intensities of AHA are weaker, suggesting that although aromatic substances such as lignin from furfural residue participated in the synthesis reaction, their content was relatively lower. There might be some inorganic impurities in the furfural residue so both the C and O in the obtained AHA are diluted (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Infrared spectra of humic acids.

3.2.3. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

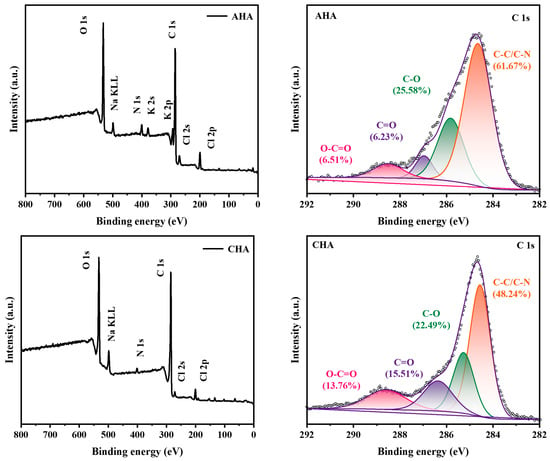

The XPS spectra of the two humic acids are depicted in Figure 2. A potassium (K) peak appeared in the wide-scan spectrum of AHA, which was due to the addition of KOH during the alkaline hydrolysis process. Introduction of K+ is also one reason for the slightly lower organic matter content of AHA in the elemental analysis (Table 4). The C1s spectrum can be deconvoluted into four peaks (284.60, 285.26, 286.97 and 288.51 eV), corresponding to C–C/C–N, C–O, C=O and O–C=O bonds, respectively. The peak area ratio of AHA at 284.60 eV (61.67%) is higher than that of CHA (48.24%) due to the increased C–N bonds in the AHA with urea introduced in the humification process, which is consistent with the result of elemental analysis. Accordingly, ratios of C=O and O–C=O bonds from AHA (6.23%, 6.51%) are lower than those of CHA (15.51%, 13.76%). Apart from the dilution effect of N, a possible cause is that the humification degree of AHA is slightly lower than that of CHA. There are insufficient oxygen-containing polar functional groups in AHA, which exactly highlights the necessity of supplementing these groups from the subsequent additives to maintain the dispersion of the suspension fertilizer and the activity of humic acid.

Figure 2.

Wide-scan and C1s spectra of XPS analysis of humic acids.

3.2.4. Aromaticity Analysis

The absorbance characteristics of humus at specific wavelengths in ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (UV-Vis) can be correlated with its structure. For instance, a lower E4/E6 value (ratio of absorbance at 465 nm to that at 665 nm) indicates a larger molecular weight, stronger aromaticity and a higher degree of humification of humic acid [23]. The E2/E3 ratio (400 nm/600 nm) reflects the molecular weight distribution. The ΔlgK, defined as the difference in the logarithm of absorbance at two different wavelengths of 465 and 665 nm, can be used to characterize the oxidation degree of humic substances [24]. These spectral parameters of the two humic acids differ only slightly, indicating similar structural characteristics (Table 5). A considerable portion of lignocellulose in the furfural residue underwent hydrothermal reaction, resulting in its degradation into small-molecule intermediates, which further polymerized into highly aromatic humic substances with structure even approaching commercial humic acids. Generally, the E2/E3 and E4/E6 values of AHA are slightly greater than those of CHA, indicating that its aromatization degree is slightly lower than that of CHA, which corroborates the results of the preceding XPS analysis.

Table 5.

Aromaticity analysis of humic acids by UV-Vis.

3.3. Humic Acid-Containing Suspension Fertilizer

3.3.1. Influence of Dispersants

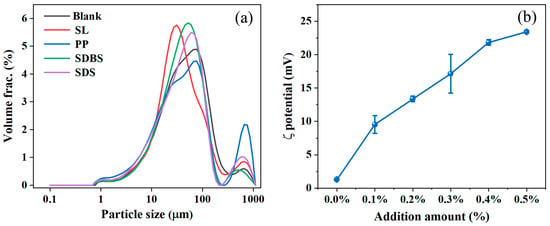

In a suspension fertilizer system, the particle size and viscosity of the suspension system both affect the settling rate of solid particles. Smaller particle sizes and higher viscosities result in lower settling rates. The alkaline hydrolysate was mixed with wet-process phosphoric acid, urea and potassium chloride. By regulating the type and dosage, the suitable dispersant for the suspension was screened to achieve smaller particle size and high absolute ζ potential [25]. As indicated in Figure 3, the particle size of the suspensions using dispersants is generally decreased compared to the blank treatment, indicating that the four dispersants perform a certain dispersing effect, thereby improving the suspension stability. Among them, sodium lignosulfonate reduces the D50 size to the smallest: 36.80 μm. Sodium pyrophosphate reduces the D10 size to the smallest, 8.38 μm, but its D90 particle size was the largest: 531.00 μm. Sodium pyrophosphate may have altered the fracture mechanism of the fertilizer particles to promote milling and crushing into more small crystals, but its phosphate skeleton is too short to prevent the re-aggregation of particles, thus resulting in a bimodal hydrodynamic size distribution. Therefore, sodium lignosulfonate was selected as the dispersant for the suspension system [26].

Figure 3.

(a) Particle size distribution under different dispersants. (b) ξ potentials of suspensions with different sodium lignosulfonate additions.

The blank treatment without addition of dispersant possesses a ξ potential of only 1.29 mV. With the increased addition of sodium lignosulfonate, the ξ potential increases significantly with the highest value at an addition amount of 0.5%, reaching 23.41 mV. At lower addition amounts, the ξ potential is lower and the dispersant hardly envelops the suspended particles uniformly. The surface charge density of particles is low, making it difficult to form a stable double-layer structure, leading to an unstable suspension state [27]. With increased addition, the electrostatic repulsion between particles was intensified, reducing particle aggregation (Ostwald ripening) and improving the suspension stability. Therefore, the addition amount of sodium lignosulfonate was determined to be 0.50%.

3.3.2. Influence of Thickeners

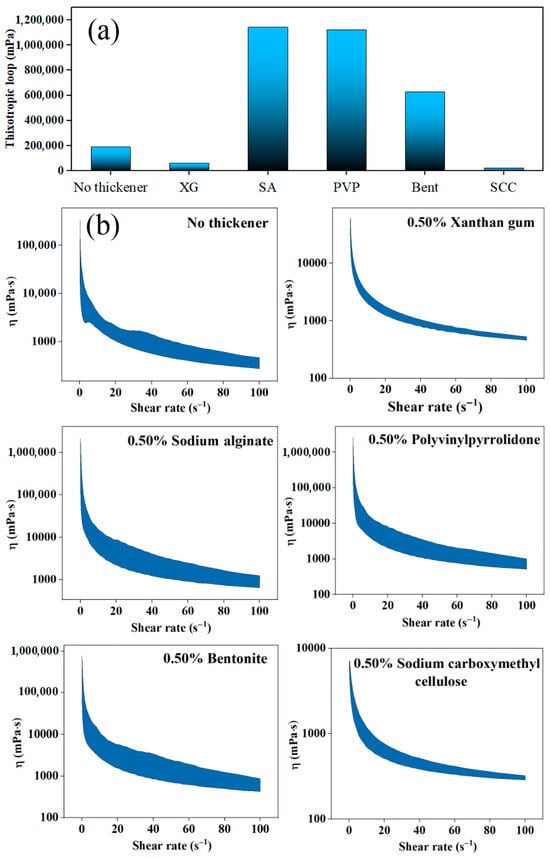

The alkaline hydrolysate, wet-process phosphoric acid, urea, potassium chloride and 0.50% sodium lignosulfonate were mixed. Suitable thickener and dose for this suspension fertilizer were investigated for an outstanding rheological performance. The thixotropic loop of systems involving different thickeners reflects the quality of thixotropic properties as shown in Figure 4. All tested samples exhibit time-dependent structural recovery when subjected to shear force [28]. Suspension fertilizers treated with sodium alginate and polyvinylpyrrolidone receive the largest thixotropic loop areas over one million mPa. Generally, the larger the thixotropic loop area, the better the suspension stability [17,29]. However, in this humic acid-containing suspension fertilizer system, an excessively large thixotropic loop area can cause a turn into a gel state with extremely poor flowability after standing for 12 h, which is hardly beneficial for the following pumping process during fertilization. Meanwhile, the suspension with carboxymethyl cellulose exhibits the smallest thixotropic loop area of only 21,821 mPa, which is excessively small. Under the selected addition amount, xanthan gum might be more accessible. Herein, xanthan gum actually thins the blank fertilizer without thickener but still retains the stability of the suspension (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Influence of thickener types on the thixotropy of suspension fertilizers: (a) Thixotropic loop; (b) Viscosity, η.

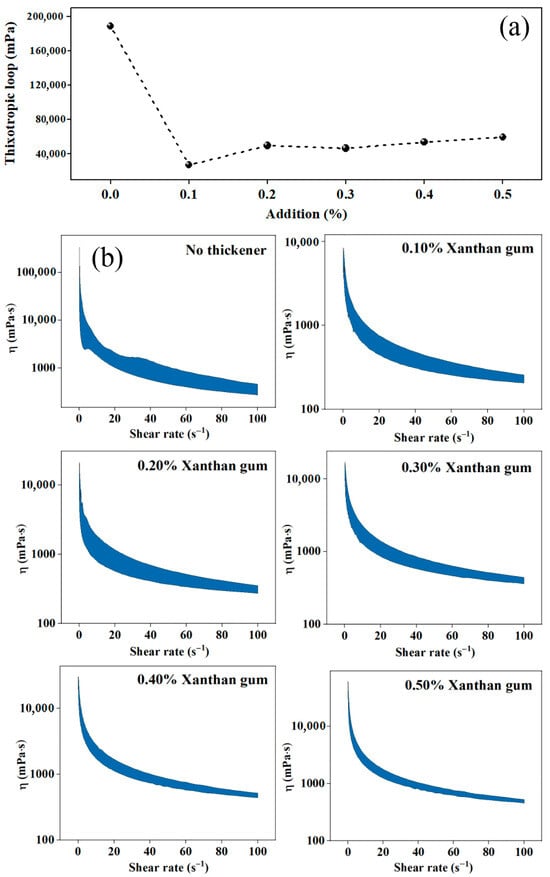

Increased usage of xanthan gum has expanded the thixotropic loop area (Figure 5). There is an abrupt increase of area from 27,205 to 49,879 mPa with an augmentation of 83% when the xanthan gum dose changed from 0.10% to 0.20%. The internal structure of the system with a 0.20% addition is strengthened, causing an easier transition from the solid state to fluid state during shearing, which can significantly reduce the mechanical load of fertilizer blending and pumping. A sufficiently large thixotropic loop area indicates that the viscosity is not prone to a sharp increase when the shear rate decreases. Whether the flow fluctuated or the stirring/pumping stopped, equipment for spraying would not be broken down due to a sudden increase in viscosity [30]. Since the addition of 0.2% to the suspension is already sufficient for stability and a further increase causes limited improvement, 0.2% of xanthan gum is thus a more appropriate dosage with controllable cost.

Figure 5.

Influence of xanthan gum dosage on the thixotropy of suspension fertilizers: (a) Thixotropic loop; (b) Viscosity, η.

3.3.3. Influence of Antimicrobial Agents

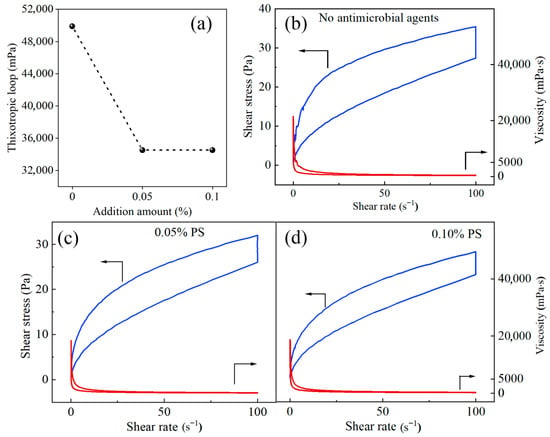

An antimicrobial agent (potassium sorbate) was introduced to inhibit the propagation of harmful microorganisms in this organic suspension fertilizer [31]. In Figure 6, the thixotropic loop area of the blank treatment (no antimicrobial agent), 0.05% potassium sorbate and 0.10% potassium sorbate is 49,880 mPa, 34,533 mPa and 31,945 mPa, respectively. The addition of potassium sorbate leads to an acceptable decreasing trend in the thixotropic loop area because of its inhibitory effect on the suspension viscosity. An increased concentration of antimicrobial agent slightly decreases the thixotropic loop area but also augments the cost. Therefore, the final addition amount of potassium sorbate was selected to be 0.05%, with which the shelf life of suspended fertilizer can reach up to 2 years.

Figure 6.

Influence of potassium sorbate dosage on the thixotropy of suspension products: (a) Thixotropic loop; (b) No antimicrobial agents; (c) 0.05% PS; (d) 0.1% PS.

3.4. Variable-Temperature Rheological Test

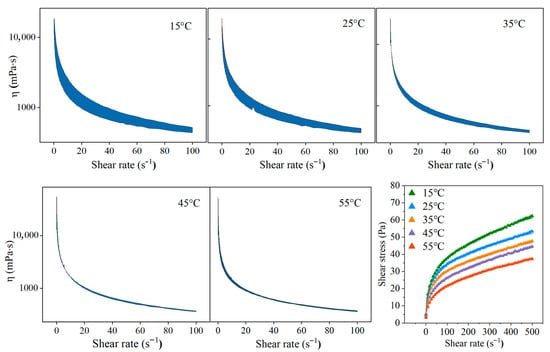

The accessibility of production, storage and usage of suspension fertilizers may be affected by different ambient conditions. Consequently, ascertaining the effect of temperature changes on suspension fertilizers is of practical importance. The rheology is discussed within the temperature range of 15–55 °C. As shown in Figure 7 and Table 6, the apparent viscosity of the suspension fertilizer decreases with increasing shear rate, and the shear stress increases with increasing shear rate, exhibiting the characteristics of a pseudoplastic fluid. To quantitatively analyze their flow properties, the Herschel–Bulkley model is used for fitting [32]. This model can reflect the rheological properties of non-Newtonian fluids, especially fluids with yield stress characteristics under specific conditions. The fitting coefficients (R2) of the Herschel–fBulkley equation for suspension systems at the five temperatures all surpass 0.99, indicating a successful fitting. The resulting flow index (n) is always less than 1, indicating a typical pseudoplastic non-Newtonian fluid with certain yield values. Within the range of 15–55 °C, the yield value (τ) of the suspension system first increases and then decreases when temperature rises, with a peak value obtained at 25 °C. A larger yield value means a more stable suspension system. Meanwhile, the consistency index (K) also shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. Therefore, K and τ both reach a peak at 25 °C, indicating the highest stability at room temperatures. This is beneficial for the most common room-temperature scenarios of storage and transportation. The flow index (n) is also an indicator of the deviance degree of a real fluid from a Newtonian fluid. The flow index (n) of the suspension system slightly decreases and then increases with the enhanced temperature, but the amplitude is small to hardly influence the suspension stability. Higher temperatures facilitate sedimentation, which is easier to understand as the viscosity decreases. At lower temperatures, there is a tendency of colloid particles forming a stable hydrogen bond network with water through dispersants indeed, but the unfavorable yield stress persists, which might be due to the fact that fertilizers are more prone to crystallize into larger particles at low temperatures, causing collapse of the suspension system [33]. Nevertheless, the yield values within the range of 15–55 °C are all acceptable.

Figure 7.

Influence of different temperatures (15–55 °C) on the thixotropic ring of suspension (0.50% sodium lignosulfonate, 0.20% xanthan gum and 0.05% potassium sorbate).

Table 6.

Rheological parameters as results of thixotropic ring fitting basing Herschel–Bulkley model.

4. Conclusions

According to Stokes law, high viscosity can slow down particle settling. Since most of the particles in the obtained suspended fertilizer exceeded the range of colloidal particles (>1 μm), their sedimentation driving force should mainly originate from the deviation between the gravity and buoyancy of the particles, while the electrostatic repulsive force from the surface charge plays a relatively minor role. Therefore, in this work, the effect of the thickener should be greater than that of the dispersant. In the future, more attention should be focused on the direct regulation of the viscosity of similar systems to resist the sedimentation driving force. However, the thickener should not be used in excessive amounts, otherwise it will greatly increase the stirring and transportation load when spraying these fertilizers. In conclusion, the production of artificial humic acid was achieved through the artificial humification of furfural residue. The appropriate process parameters were determined as a liquid-to-solid ratio of 15:1, hydrothermal time of 5 h and a reaction temperature of 160 °C, where 2.21% of FA content and 1.54% of HA content were obtained. The type and dosage of the suspension additives were optimized to formulate suspensions combined with N P K inorganic fertilizers. As a result, 0.50% sodium lignosulfonate, 0.20% xanthan gum and 0.05% potassium sorbate were selected to economically stabilize fertilizers. The nutrient content of the optimized suspension fertilizer is calculated as 25%N, 25%P2O5, 25%K2O and 0.63% of total humic acid. In the well-fitted Herschel–Bulkley model, the suspension system exhibits shear-thinning characteristics within the range of 15–55 °C, demonstrating expected suspension stability. The idea of floating fertilizers directly using the waste-biomass derivate intermediate, can contribute to the large-scale water-saving and carbon-sustainable agriculture in the future. But before that, a more detailed life-cycle assessment (LCA) must be conducted. In addition to supplementing levels of the parameters in experiments, future work should focus on comparing the cultivation effects of this suspended fertilizer with equal commercial phosphorus fertilizers. Along with the exploration of the fine structure that AHA progresses, its agricultural efficacy–structure relationship is expected to be resolved.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.B., X.Y., D.X., B.Z. and X.W.; Methodology, N.B., S.L., F.H. and X.W.; Software, N.B. and J.Y.; Validation, N.B., X.Y. and Z.Y.; Formal analysis, F.H., D.X. and X.W.; Investigation, N.B., X.Y. and S.L.; Resources, X.Y., X.L., F.H., D.X., Z.Y., B.Z. and X.W.; Data curation, S.L.; Writing—original draft, N.B., X.Y. and S.L.; Writing—review and editing, N.B., X.Y., S.L., J.Y., X.L. and D.X.; Visualization, J.Y. and F.H.; Supervision, J.Y., X.L., F.H. and B.Z.; Project administration, Z.Y., B.Z. and X.W.; Funding acquisition, J.Y., Z.Y. and X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Xinjiang Key Laboratory of Clean Conversion and High Value Utilization of Biomass Resources, Yili Normal University (CN) (Grant no. XJSWZ202407), the 145th National Key Research and Development Plan (CN) (Grant no. 2023YFD1700204), National Natural Science Foundation of China (CN) (Grant no. 32502829), and Phosphorus Resources Efficient Use Engineering Characteristic Team Project of Sichuan University (CN) (Grant no. 2020SCUNG113).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Inkoua, S.; Li, C.; Fan, H.; Bkangmo Kontchouo, F.M.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.; Hu, X. Pyrolysis of furfural residues: Property and applications of the biochar. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Ran, M.; Fang, G.; Wu, T.; Ni, Y. Biochars from lignin-rich residue of furfural manufacturing process for heavy metal ions remediation. Materials 2020, 13, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Kang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Siyal, A.A.; Ao, W.; Ran, C.; Fu, J.; Deng, Z.; Song, Y.; Dai, J. Microwave-assisted pyrolysis of furfural residue in a continuously operated auger reactor: Biochar characterization and analysis. Energy 2019, 168, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Meng, X.; Qu, J.; Liu, C.; Qu, B. A Review on the Transformation of Furfural Residue for Value-Added Products. Energies 2020, 13, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; He, Z.; Yang, L.; Wei, X.; Hu, J.; Li, P.; Yan, Z.; Chen, Z.; Chang, C. Preparation and characterization of furfural residue derived char-based catalysts for biomass tar cracking. Waste Manag. 2024, 179, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, X.; Li, Q.; Su, Y.; Zhao, W. Exploration of the H2O2 oxidation process and characteristic evaluation of humic acids from two typical lignites. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 24051–24061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Antonietti, M. Artificial humic acids: Sustainable materials against climate change. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1902992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaetxea, M.; De Hita, D.; Garcia, C.A.; Fuentes, M.; Baigorri, R.; Mora, V.; Garnica, M.; Urrutia, O.; Erro, J.; Zamarreño, A.M.; et al. Hypothetical framework integrating the main mechanisms involved in the promoting action of rhizospheric humic substances on plant root- and shoot- growth. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 123, 521–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Du, Q.; Sui, L.; Cheng, K. One-step fabrication of artificial humic acid-functionalized colloid-like magnetic biochar for rapid heavy metal removal. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 328, 124825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Yang, R.; Pei, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, J.; He, D.; Huang, Q.; Zhong, H.; Jin, F. Hydrothermal synthesis of similar mineral-sourced humic acid from food waste and the role of protein. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 828, 154440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Z.; Sun, K.; Fan, H.; Li, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Ding, K.; Gao, G.; Hu, X. Understanding evolution of the products and emissions during chemical activation of furfural residue with varied potassium salts. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 357, 131936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, K.; Antonietti, M. A hydrothermal process to turn waste biomass into artificial fulvic and humic acids for soil remediation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 686, 1140–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobreira, H.d.A.; Ferreira, M.V.; Faria, A.M.d.; Assunção, R.M.N.d. Commercial organomineral fertilizer produced through granulation of a blend of monoammonium phosphate and pulp and paper industry waste post-composting. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, D.; Deng, F.; Cao, Z.; Zheng, G. Production of artificial humic acid from rice straw for fertilizer production and soil improvement. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Bao, M.; Huo, W.; Ye, R.; Liu, Y.; Lu, W. Production of artificial humic acid from biomass residues by a non-catalytic hydrothermal process. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 335, 130302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Yin, J. Comparison of two kinds of methods on humic acids in weathered coal and soils. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2007, 23, 277–279. [Google Scholar]

- He, F.; Zhou, X.; Luo, T.; Wang, X. Study on the preparation of high-concentration ammonium phosphate suspension fertilizer from wet-process phosphoric acid and its rheological properties. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 161, 105497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Lu, Q. Degradation or humification: Rethinking strategies to attenuate organic pollutants. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Muhmood, A.; Dong, R.; Wu, S. Synthesis of humic-like acid from biomass pretreatment liquor: Quantitative appraisal of electron transferring capacity and metal-binding potential. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, G.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, R.; Liang, S.; Lu, S.; Ma, L. Preparation and structural characterisation of coal-based fulvic acid based on lignite. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1260, 132766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G.; Yoon, H.Y.; Cha, J.-Y.; Kim, W.-Y.; Kim, P.J.; Jeon, J.-R. Artificial humification of lignin architecture: Top-down and bottom-up approaches. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 107416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zheng, J.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Yan, X.; Davronbek, B.; Wu, J.; Boguta, P.; Zhang, L.; Ren, J.; et al. Air heating-alkaline hydrothermal production of artificial humic acid: Rapid and efficient humification of waste biomass. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlaja, J.P.K. Molecular size distribution and spectroscopic properties of aquatic humic substances. Anal. Chim. Acta 1997, 337, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Liu, H.; Wen, J.; Zhao, C.; Dong, L.; Liu, H. Underestimated humic acids release and influence on anaerobic digestion during sludge thermal hydrolysis. Water Res. 2021, 201, 117310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, C.G.; Lehmann, M.; Kulmer, D.; Zaeh, M.F. Modeling of the stability of water-based graphite dispersions using polyvinylpyrrolidone on the basis of the DLVO theory. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Xiang, D.; Zhang, W.; Bai, X. Stability of lutein in O/W emulsion prepared using xanthan and propylene glycol alginate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 152, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, M.; Li, Y.; Gao, W.; Qiu, X. Relationship between the hydrophilicity of lignin dispersants and their performance towards pesticide particles. Holzforschung 2016, 70, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dullens, R.P.A.; Bechinger, C. Shear thinning and local melting of colloidal crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 138301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bi, H.; Shen, S. Thixotropy of aqueous suspensions containing Mg-Al hydrotalcite-like compound and low-substituted cationic starch: Comparison between oscillatory shear and thixotropic loop measurements. Chin. J. Chem. 2011, 29, 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Elella, M.H.; Goda, E.S.; Gab-Allah, M.A.; Hong, S.E.; Pandit, B.; Lee, S.; Gamal, H.; Rehman, A.u.; Yoon, K.R. Xanthan gum-derived materials for applications in environment and eco-friendly materials: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 104702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinlapapanya, P.; Palamae, S.; Buatong, J.; Saetang, J.; Zhang, B.; Fu, Y.; Benjakul, S. Synergistic effect of hyperoside and amentoflavone found in cashew leaf crude extract and potassium sorbate on inhibition of food spoilage bacteria. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Zhou, J. Experimental study on the rheological properties of MF lubricant based on the Herschel-Bulkley model. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2022, 35, 3333–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogusz, P.; Rusek, P.; Brodowska, M.S. Suspension Fertilizers: How to Reconcile Sustainable Fertilization and Environmental Protection. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.