Abstract

Under the national carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals, electrical equipment plays a crucial role in energy production, transmission, and end-use systems, making the research on its lifecycle carbon emissions and mitigation strategies particularly significant. Based on the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) framework, this review systematically examines carbon emission characteristics across raw material acquisition, manufacturing, transportation, usage, and end-of-life recycling stages of electrical equipment. The analysis indicates that the manufacturing and usage stages are generally the main contributors to total lifecycle emissions. Moreover, challenges such as incomplete carbon data, inconsistent boundary definitions, and insufficient recycling systems are highlighted. Correspondingly, this review summarizes key mitigation pathways, including low-carbon design and material optimization, low-carbon manufacturing processes, energy-efficient operation supported by intelligent monitoring, and enhanced recycling and remanufacturing practices. Finally, future perspectives are proposed, emphasizing the need to establish unified LCA databases, develop intelligent and data-driven carbon monitoring systems, and strengthen cross-sector collaboration to support the green and low-carbon transformation of electrical equipment industries.

1. Introduction

As global industrialization progresses, greenhouse gas emissions from human activities have increased, contributing to a worsening global warming crisis. Industrial construction and ongoing maintenance require substantial material consumption, which has become a significant source of carbon dioxide emissions [1]. Reports indicate that, in the U.S. construction industry, emissions related to electricity account for approximately 40% of the country’s total emissions [2]. Therefore, it is essential to address excessive greenhouse gas emissions to mitigate the impacts of climate change. In response, Chinese authorities have issued the Guiding Opinions on Coordinating Energy Conservation, Carbon Reduction, and Recycling to Accelerate the Update and Transformation of Key Product Equipment in Key Sectors, urging the electrical equipment industry to accelerate carbon emission accounting. Similarly, numerous countries globally have implemented carbon footprint management measures [3] to combat climate change and fulfill international obligations.

Energy systems are the largest global GHG emission source, accounting for ~60% of total emissions [4]. As the “backbone” of energy production, transmission, distribution, and end use, electrical equipment encompasses power grid transformers/switchgear, industrial motors/inverters, EV charging infrastructure, and renewable-integrated energy storage. Their ubiquity and long lifespan result in lifecycle carbon footprints spanning raw material extraction, manufacturing, transportation, operation, and end-of-life disposal. For instance, a 50 MVA 110 kV transformer emits ~27 t CO2e over its life cycle, with manufacturing and usage contributing 55% and 40%, respectively. Yet, its carbon mitigation role has long been overshadowed by broader energy policies (e.g., renewable deployment), leading to a lack of targeted life cycle emission strategies. Key carbon footprint management methods currently include the life cycle approach, the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) method, and input-output analysis. The material-intensive nature and long lifespan of electrical equipment contribute to significant carbon emissions across its life cycle. These emissions occur not only during the usage phase but also throughout the manufacturing, transportation, disposal, and recycling stages, all of which play a significant role in its overall carbon footprint. LCA has been widely used to evaluate emissions at each stage, from raw material extraction to manufacturing, transportation, use, and end-of-life recycling [4]. Although some studies have focused on specific life cycle stages, comprehensive research covering the entire life cycle of electrical equipment remains insufficient [2].

The life cycle of electrical equipment consists of six stages: raw material acquisition, raw material transportation, product manufacturing, product transportation, product use, and product recycling. This review will analyze the carbon emission characteristics of each stage, highlighting key challenges such as incomplete data, inconsistent boundary definitions, and insufficient recycling systems, all of which impact the accuracy of carbon footprint assessments. The manufacturing and usage stages are typically the primary sources of carbon emissions, particularly due to the energy-intensive processes involved in producing materials like copper, steel, and aluminum. Additionally, the operational phase of electrical equipment, especially for devices that rely on fossil fuels, further increases carbon emissions. Nonetheless, significant emission reductions can be achieved through low-carbon design, energy-efficient technologies, and improved recycling and remanufacturing practices. Increasing recycling rates, expanding remanufacturing applications, and optimizing material use, alongside better operational efficiency, can help reduce the overall carbon footprint.

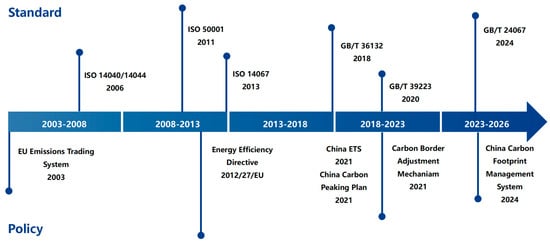

Policy incentives and industry standards are also essential in driving the low-carbon transformation of the electrical equipment industry. Many countries have established frameworks that integrate policy guidance with standardization [5]. At the same time, the development of standards such as ISO 14040 [6], ISO 14044 [7], and ISO 14067 [8] (ISO stands for the International Organization for Standardization) has provided valuable guidance for carbon footprint quantification. Additionally, policies like carbon pricing and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) offer market incentives to encourage the adoption of low-carbon solutions.

Against this backdrop, this review’s core motivation is threefold: Using a unified LCA framework to analyze electrical equipment’s lifecycle carbon emissions, addressing fragmented research and identifying emission hotspots; unpacking key challenges to accurate carbon assessment (incomplete data, inconsistent boundaries, underdeveloped recycling) and their impacts on practice/policy; and integrating tech innovation, circular economy, and policy/standards to develop actionable emission reduction strategies and a holistic low-carbon roadmap. By filling these gaps, the review offers evidence-based support for stakeholders (manufacturers, energy firms, policymakers) to align with global carbon neutrality, while highlighting understudied areas to guide future research.

2. Lifecycle Carbon Emission Framework of Electrical Equipment

2.1. LCA Methodology Overview

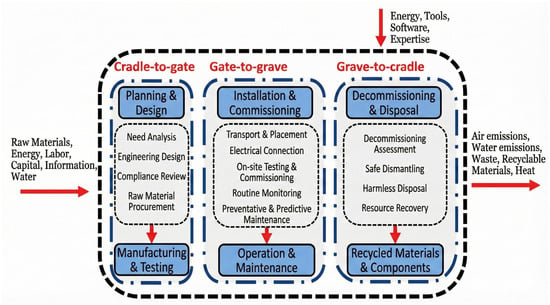

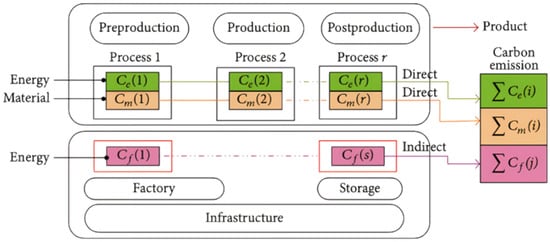

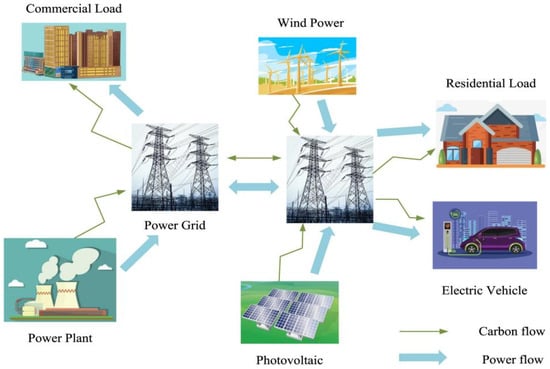

LCA is a systematic method used to quantify the resource consumption and environmental impacts of a product, process, or service throughout its entire life cycle, from raw material acquisition to manufacturing, transportation, use, and disposal. As one of the most widely used and respected environmental impact assessment methods globally, LCA focuses on a cradle-to-grave system boundary. By identifying, quantifying, and evaluating material and energy flows at each stage, it provides an objective reflection of the environmental burdens throughout the product’s life cycle (ISO 14040, 2006). An example of the life cycle process for an electrical product is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The life cycle process for an electrical product.

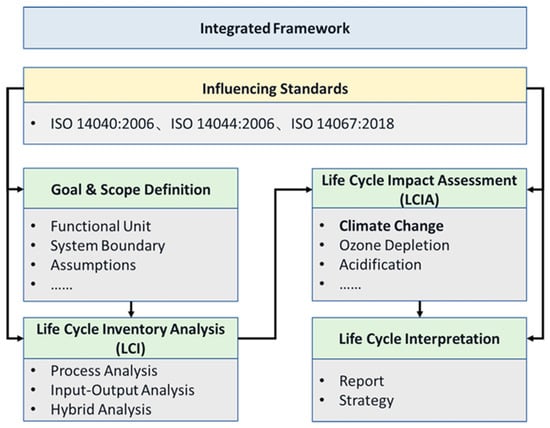

The International Organization for Standardization has published two core standards, ISO 14040 and ISO 14044, which provide unified guidelines for the principles, framework, implementation processes, and data requirements of LCA (ISO 14040, 2006; ISO 14044, 2006). According to these standards, LCA generally consists of four stages: (1) goal and scope definition, (2) Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) analysis, (3) Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA), and (4) interpretation of results. The introduction of these standards has enhanced the comparability and transparency of environmental assessments, providing a foundational methodology for carbon emission accounting and the development of emission reduction strategies across various industries. The structure of these four LCA stages is shown in Figure 2.

With the introduction of dual carbon goals, the LCA method has become widely used in carbon emission assessment studies of electrical equipment, including transformers, circuit breakers, cables, and switchgear. While the number of LCA studies on traditional electrical equipment like transformers, switchgear, and circuit breakers is still relatively limited, the methods have been validated in power infrastructure, power electronic devices, transmission systems, and component materials, laying the groundwork for equipment-level LCA. For instance, Finnveden et al. [9] emphasized that LCA is particularly useful for identifying system carbon emissions from energy-consuming equipment and is an essential tool for energy system assessments. Given that electrical equipment involves large quantities of metal materials (such as copper, aluminum, and steel) and complex manufacturing and operational processes, LCA has become a critical tool for quantifying carbon emissions. Nuss et al. [10] noted that metal production, especially during the purification and refining stages, is a significant source of carbon emissions. For example, the global annual production of metals like iron, aluminum, and copper contributes substantially to overall emissions. This insight is crucial for carbon footprint assessments of electrical equipment: emissions not only result from electricity consumption during operation but are also closely tied to the production processes of the metal raw materials used. Nuss’s study employed an LCA model compliant with ISO 14040/14044 standards, using SimaPro8 software and the Ecoinvent database to develop life cycle inventory data for global metal production. By applying the economic allocation method to multi-output processes, environmental burdens from various metals were systematically allocated, providing reliable data and methodological support for the carbon footprint calculation of metal materials in electrical equipment.

Figure 2.

Comprehensive Framework for Life Cycle Assessment [11].

The LCA method and its international standards offer a unified, transparent, and comparable tool for assessing the carbon emissions of electrical equipment. This approach helps identify high-emission stages and supports strategies for low-carbon design, material optimization, and green supply chain management.

2.2. Life Cycle Stages and Boundary Definition

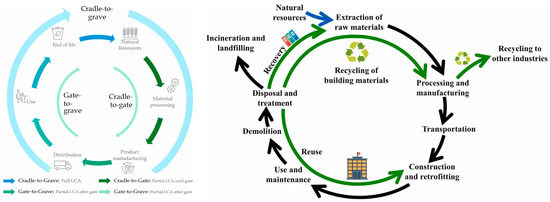

In analyzing the carbon emissions across the life cycle of electrical equipment, it is crucial to systematically identify the sources of emissions at each stage, including key phases such as raw material acquisition, manufacturing, transportation, use, and disposal/recycling. Each stage must clearly define its carbon emission boundaries—covering materials, energy, transportation, maintenance, waste treatment, and other relevant activities—and choose the appropriate evaluation methods. Figure 3 shows a schematic diagram of the life cycle stages.

Figure 3.

A schematic diagram of the life cycle stages (The arrows shown in the figure represent the different stages and processes in the cycle) [12,13].

The raw material stage [14] is a major source of carbon emissions in electrical equipment, covering the processes from mining, smelting, and material processing of key raw materials (such as steel, copper, aluminum, insulation materials, and oil/coolants) to the supply of these materials to the manufacturing plant. For boundary setting, the Cradle-to-Gate model can be applied, which covers the extraction of natural resources for raw materials and extends to the delivery of qualified materials or components to the manufacturing plant. This boundary includes energy consumption and upstream carbon emissions associated with mining and smelting processes, direct energy consumption and process emissions from material processing, and carbon emissions from logistics transportation of raw materials from processing plants to manufacturing plants. This phase adopts the process method for evaluation, first by accounting for the types and quantities of energy consumed in processes such as mining, smelting, and processing, with the consumption of each energy type being converted into CO2 emissions using corresponding emission factors [15,16].

Priority should be given to using enterprise-specific measured data for particular scenarios; if unavailable, secondary data meeting the requirements of GB/T 24044 should be used, with a data time span not exceeding 10 years. For greenhouse gas leak emissions such as SF6, the leak quantity should first be estimated using the leakage coefficient according to equipment type and maintenance status, based on industry standards. Then, the leakage amount should be converted according to the global warming potential (GWP) of the corresponding gas, and the emissions should ultimately be converted into CO2 equivalents. During the purification and storage process, leakage emissions should be estimated based on equipment technical performance, operational history, and industry literature. If measured data is available, it should be prioritized; if not, estimates should be made based on relevant research and industry standards [17].

The manufacturing stage [18] includes processes such as processing, assembly, testing, and final preparation before shipment, once raw materials enter the manufacturing plant. This stage covers component processing, equipment assembly, oil impregnation or dry-type filling, testing, casing manufacturing, wiring, and control system installation. The carbon emission boundary is defined as the production system within the factory gate, which includes direct emissions from fossil fuel combustion, indirect emissions from purchased electricity, and emissions from the consumption of auxiliary materials and process waste gases. Non-production-related activities, such as office and living energy consumption within the plant and temporary storage of waste materials, are excluded. Additionally, methane emissions from the production wastewater treatment process are included in the assessment scope. This stage is evaluated using the process analysis method, where unit processes are broken down according to the production procedures. Activity data for each unit (such as energy and auxiliary material consumption) is collected, and carbon emissions are calculated using the emission factors specified in GB/T 32150. For complex assembled equipment, emissions are calculated separately for each component production process and then aggregated. Sensitivity analysis is also conducted to assess the impact of high-energy-consuming processes, such as welding and heat treatment, on the results. Carbon emissions from this stage typically account for 20–30%, and are directly related to the complexity of the production process [19]. When using renewable energy, the carbon emission boundary should consider the green-house gas emissions generated by the direct combustion or consumption of renewable energy in the production process; if the electricity purchased by the enterprise is green electricity, the emission factor of this electricity should be set to zero or close to zero [15,20]. The emissions in this section should be calculated using the market-based method, which accounts for the carbon emissions based on the actual type of electricity purchased; alternatively, the location-based method can be used, which calculates emissions based on the average emission factor of the electricity grid in the enterprise’s region [21].

The transportation stage [22] involves the logistics process of delivering the product from the manufacturing site to the usage location and may also include the transportation of raw materials or components to the manufacturing plant. This stage uses a door-to-door boundary, starting when the material leaves the supplier’s gate and ending when it reaches the destination. The assessment scope includes emissions from fuel combustion in transportation vehicles and energy consumption for refrigeration and insulation during transport, but excludes indirect impacts such as the manufacturing of transportation vehicles and road construction. However, there are significant differences in carbon emission factors for different fuels. Traditional fossil fuels have higher carbon content, resulting in larger CO2 emissions during combustion; compared to fossil fuels, biofuels generally have lower carbon emissions; if electric transport vehicles are used, the source of electricity directly affects the carbon emissions during the transportation process. At the same time, the energy density of different fuels also affects the emissions per unit of fuel. Therefore, when evaluating emissions during the transportation phase, the corresponding emission factor should be chosen based on the type and mass of fuel actually used by the transport vehicle. If mixed fuels are used, the overall emission factor of the fuel should be calculated by weighting the proportions of different components [23].

The typical assessment method [24] is the fuel consumption method, where the fuel consumed by transportation or the electricity used by transportation vehicles is converted into CO2 equivalent emissions. If detailed data is unavailable, the ton-kilometers method, multiplied by the emission factor, can also be used. However, it is essential to account for factors such as load factor, empty load rate, transportation distance, and mode of transport, as these significantly influence emissions.

The usage stage [18] refers to the phase in the life cycle of electrical equipment during its actual operation, including losses during operation after installation and commissioning, regular maintenance, and material and energy consumption associated with component replacement. For electrical equipment, the usage stage typically accounts for the largest portion of carbon emissions. The carbon emission boundary is defined as the equipment operating system, which includes electricity consumption, fuel consumption emissions, leakage emissions of insulating gases such as SF6, and emissions from auxiliary material consumption during maintenance. External factors, such as transmission losses on the grid side and energy consumption from other supporting equipment at the usage site, are excluded. For energy-consuming equipment such as transformers and switchgear, electricity consumption over the entire life cycle is calculated based on the operating load curve and energy efficiency parameters, with indirect carbon emissions assessed by incorporating regional grid emission factors. For equipment containing SF6, leakage emissions are calculated based on leakage rates and service life, and these emissions are converted to carbon dioxide equivalents using the GWP coefficient.

The end-of-life and recycling stage [25] covers processes that occur after the life cycle of electrical equipment ends, including dismantling, transportation to waste disposal or remanufacturing/recycling facilities, as well as component/material recovery, waste disposal, and recycling. This stage may generate carbon emissions, but it can also offer emission reduction benefits through recycling and reuse. The decommissioning to final disposal boundary [22] begins with the dismantling of the equipment after it has been decommissioned and ends with the recycling or safe disposal of materials. The assessment scope includes emissions from energy consumption during dismantling, emissions from waste incineration or landfilling, and the carbon emissions savings from material recycling. The End-of-Life assessment method [26] is applied, where unit processes are broken down according to the dismantling procedures. Data on energy consumption during dismantling, waste generation, etc., are collected, and direct carbon emissions are calculated using emission factors corresponding to the disposal methods. Carbon savings from material recycling are calculated by subtracting the carbon emissions from recycling energy consumption from the carbon emissions of primary material production, with metal recycling significantly reducing carbon emission intensity. Material recycling and substitution are prioritized in low-carbon design for electrical equipment, and further emission reduction potential can be achieved by optimizing recycling processes. The assessment for this stage must adhere to the principles of ISO 14067 to ensure the accuracy of recycling benefits quantification. The relevant summary is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Life Cycle Stages, Definitions, and Carbon Emission Boundaries with Assessment Methods.

2.3. Data Sources and Uncertainty

The data used in LCA primarily comes from the following sources: (1) Measured data from equipment: This includes data on energy consumption, material usage, waste gas/wastewater emissions, and other factors from actual operations or manufacturing processes within the company. This type of data is more representative and less biased, making it the preferred source. (2) Database or literature data: When measured data is unavailable, secondary data sources such as national or industry databases, public literature, or LCA reference databases (e.g., Ecoinvent 3 or GaBi 10.0) can be used. However, such data often has regional, temporal, and process differences, so it should be used with caution [27]. (3) Estimation data or expert judgment: For stages that are difficult to measure or for which data is not yet available (such as certain auxiliary materials or leakage of special gases), estimation methods or expert surveys can be used. However, this data typically carries the highest level of uncertainty [28].

LCA, as a key method for analyzing the carbon emissions of electrical equipment, heavily depends on the accuracy and completeness of the input data. The data used in LCA mainly includes energy consumption, emission factors, and process parameters from stages such as material extraction, manufacturing, transportation, use, and disposal. However, in practice, the heterogeneity and uncertainty of data sources are significant factors that affect the reliability of carbon emission assessment results.

The structure and material composition of different equipment can cause significant variations in their life cycle carbon emissions. For instance, in transformers or switchgear, core materials such as copper, silicon steel, and insulating oil vary in terms of sources, purity, and recycling rates, all of which impact the carbon emission assessment results [29]. Even for similar equipment, differences in production processes can lead to substantial variations in energy consumption, waste gas emissions, and resource use, making it difficult for standard databases to accurately reflect real-world conditions. Additionally, variations in the equipment’s load, environmental factors (such as temperature and humidity), and maintenance frequency can also influence carbon emissions during the usage phase.

Databases commonly used in LCA provide a wealth of background data. However, these data can sometimes be contentious due to regional, temporal, or industry differences [30]. For example, data developed for the European region, when directly applied to the life cycle analysis of electrical equipment in China, may overlook variations in local power structures and production efficiencies. Additionally, the choice of boundary settings in different studies can influence the results. For instance, some studies may exclude the maintenance cycle of the equipment or changes in energy efficiency during the usage phase, leading to an underestimation of the carbon footprint in the usage stage [31]. The final disposal method of the equipment—such as dismantling, incineration, or recycling—can also significantly affect the assessment results.

Uncertainty analysis has become a critical tool for enhancing the transparency and scientific rigor of LCA. Some studies use Monte Carlo simulations to assess the sensitivity of carbon emissions to changes in input variables, providing confidence intervals and scenario analysis [32]. In the context of electrical equipment, a high-complexity system, methods like parametric modeling and fuzzy multi-attribute decision making (e.g., Fuzzy Best Worst Method) are increasingly being applied [29]. In related fields such as Information and Communication Technology (ICT), researchers have also noted that different time scales and measurement methods significantly impact LCA results, highlighting the need for systematic uncertainty modeling [33].

To better understand the impact of data uncertainty in LCA, several specific examples illustrate how variations in material production, operational conditions, and recycling processes introduce significant uncertainties into carbon emission assessments. These examples highlight the complexities in data collection and estimation, demonstrating the challenges in achieving reliable and consistent LCA results.

The carbon emission factors of key materials, such as copper used in transformers, vary significantly due to differences in production processes. For instance, copper production, especially during the smelting and refining stages, generates substantial carbon emissions. These emissions vary greatly depending on the energy sources used in different regions. According to Nuss et al. [10], there are significant differences in the carbon emission factors of copper production across different countries, primarily due to variations in local electricity generation methods and smelting technologies. In regions where coal is the primary energy source, the copper production process results in much higher carbon emissions, which can significantly affect LCA results.

In electrical equipment like gas-insulated switchgear (GIS), SF6 gas is used as an insulating medium, and its leakage during operation is a key factor in LCA. However, the estimation of SF6 leakage is fraught with uncertainty, as it depends on factors such as equipment maintenance, operational conditions, and environmental influences. Zhou et al. [17] emphasized that the leakage rate of SF6 is closely related to the equipment’s maintenance frequency, usage duration, and the technology used. As a result, SF6 leakage estimation carries a high level of uncertainty, which impacts the accuracy of LCAs.

The recycling rate of metals plays a crucial role in reducing the carbon footprint of electrical equipment throughout its lifecycle. For example, recycling copper and aluminum significantly reduces carbon emissions compared to primary production. However, the recycling process itself introduces variability, as recycling efficiency differs across technologies. According to Li et al. [34], efficient copper recycling can reduce carbon emissions by approximately 3–4 kg of CO2e per kilogram of copper. In contrast, less efficient recycling systems result in smaller emission reductions, making recycling rate variations a significant source of uncertainty in LCA.

In conclusion, LCA studies of electrical equipment should prioritize the systematic review of data sources and the quantification of uncertainties. Enhancing data representativeness and establishing localized databases are key approaches to improving the accuracy of carbon emission assessments and supporting decision making for carbon neutrality.

3. Carbon Emission Characteristics Across Life Cycle Stages

3.1. Carbon Emissions During Manufacturing

The manufacturing stage of electrical equipment is a significant source of carbon emissions, mainly due to energy consumption, raw material use and waste treatment in the production process. In the entire life cycle of electrical equipment, carbon emissions in the manufacturing stage occupy an important position, especially during the raw material production phase.

Under the guidance of the concept of green development, the level of energy consumption and carbon emissions in the manufacturing process has become a crucial basis for evaluating and optimizing the selection of production equipment. When different equipment is used to produce the same product, the energy consumption and carbon emissions vary significantly [35]. In the manufacturing process, carbon emissions are directly linked to energy consumption, as energy is the primary source of carbon emissions in the production process. Carbon emissions depend largely on the energy grid used, especially whether the energy comes from fossil fuels or renewable energy. Fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas will release substantial carbon emissions in the process of converting into electricity. For example, coal is the fuel with the highest emissions, which releases 112 kg of carbon dioxide per gigajoule of energy, while natural gas and oil release 49 kg and 66 kg of carbon dioxide, respectively. The use of clean energy (such as hydro, solar, and wind power) does not produce carbon emissions in the energy production process [36]. Energy consumption during the manufacturing process, particularly the use of fossil fuels, is one of the primary sources of carbon emissions. In regions where energy production depends on coal, carbon emissions from manufacturing can be even more significant. Additive manufacturing (AM) can help reduce carbon emissions in some cases by optimizing design and minimizing material waste. However, these emerging technologies should be evaluated cautiously, as they introduce new variables that could either reduce or increase carbon emissions depending on the specific conditions [37].

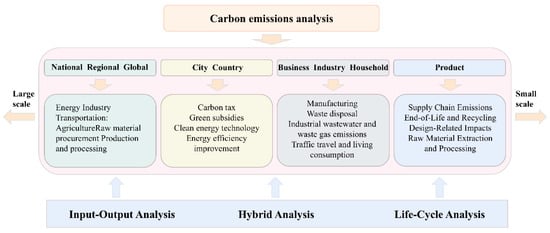

There is a significant positive correlation between electricity consumption and carbon emissions. An increase in electricity consumption leads to a corresponding rise in carbon emissions. Although electricity itself is a relatively clean energy source, the nonclean energy sources, such as coal and natural gas, relied upon in its production process still result in carbon emissions [38]. The manufacturing stage of electrical equipment involves multiple materials and processes that consume large amounts of energy, particularly during the production of energy-intensive raw materials, resulting in high carbon emissions. The carbon emission analysis method is shown in Figure 4. While the operational phase of electrical equipment (such as motor operation) also generates carbon emissions, emissions from the manufacturing stage are more significant, especially from the raw material production phase, which accounts for a large portion of total emissions. Common materials such as copper, steel, and aluminum have relatively high carbon emission factors. For instance, electrical steel, commonly used in motor cores, has a carbon emission factor of approximately 2.12 kgCO2e/kg. Copper, widely used in motor windings, has a carbon emission factor ranging from 3.81 to 8.00 kgCO2e/kg, depending on its production process [39].

Figure 4.

The carbon emission analysis method.

Globally, carbon emissions from manufacturing have risen significantly in developing countries due to the growth of energy-intensive industries, particularly in emerging economies like China and India, where coal remains the primary energy source. Transitioning to more sustainable manufacturing processes, such as adopting energy-efficient production techniques and material recycling, will help mitigate the impact of this growth on global carbon emissions [40].

3.2. Carbon Emissions During Usage

Carbon emissions during the usage phase of electrical equipment primarily result from the energy consumed during operation. The operational efficiency of the equipment directly affects its energy consumption and, consequently, its carbon emissions. Within the framework of Integrated Energy Systems (IESs), the carbon emission characteristics of electrical equipment are influenced by various factors, with the most critical being the type of energy used and its conversion efficiency. In traditional coal and natural gas power generation modes, the usage phase of electrical equipment leads to significant carbon emissions, primarily through fuel combustion, which releases carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases [41]. Different types of production equipment can show considerable differences in energy consumption and carbon emissions when processing the same product. For example, in a comparison of milling machines, lathes, and drilling machines, the energy consumption and carbon emissions of the drilling machine are much higher than those of the other two types of equipment. For the same product, the carbon emission differences between different equipment can exceed 1.5 times [35]. Although carbon emissions from raw materials mostly occur during production and transportation, these emissions still affect the operation of the final equipment. In the manufacturing process of electrical equipment, especially with metal materials such as electrical steel, copper, and aluminum alloys, carbon emissions account for a significant portion. For example, electrical steel contributes to 45% of the total carbon emissions in the equipment, while copper wire accounts for 23%. This is largely because these materials consume substantial energy during production and processing. The carbon emission analysis framework for the product manufacturing process is shown in Figure 5. The operating environment of electrical equipment (such as temperature and humidity) also significantly impacts energy consumption and carbon emissions. In high or low-temperature environments, equipment efficiency typically decreases, leading to higher energy consumption and greater carbon emissions. Additionally, changes in the equipment load can further affect its carbon emissions [42].

Figure 5.

The carbon emission analysis framework for the product manufacturing process [42].

Power transmission and distribution equipment plays a vital role in the power system, and the carbon emissions in its use phase mainly stem from energy loss. Studies have shown that, in the life cycle of key equipment, such as transformers, the carbon emissions in the use phase account for more than 90%. The energy loss of the transformer mainly includes no-load loss and load loss, particularly under low-load conditions. Although the energy efficiency is high, power losses remain the primary source of carbon emissions [11]. Carbon emissions are also generated during no-load loss and load loss of the transformer. Even under low-load conditions, the CO2-eq emissions during transformer operation in the initial stage of operation can exceed the carbon emissions in the production stage. According to the analysis, the carbon emissions of the transformer in the operation stage account for 94% to 99% of the total carbon emissions, which indicates that the operation stage is crucial to the environmental impact. Therefore, reducing no-load and load loss, using high-quality building materials and modern design solutions are the key to reducing the life cycle carbon emissions of transformers [18].

3.3. Carbon Emissions During End-of-Life and Recycling

In the life cycle of electrical equipment, carbon emissions during the decommissioning and recycling phase, while lower than those in the production and usage phases, still play a significant role in overall emission reductions. Emissions in this phase primarily result from dismantling, transportation, and waste disposal. The dismantling process, which involves mechanical equipment (such as cutters and crushers) and manual labor, consumes energy and generates direct carbon emissions. Transportation, especially for large equipment like transformers and motors, also contributes indirect emissions due to the higher energy consumption required to move bulky and heavy items [43]. Through life cycle assessment combined with material flow modeling, it is revealed that carbon emissions at the end-of-life stage of terminal equipment are primarily concentrated in three key processes: energy consumption during disassembly, losses associated with large-scale transportation, and the disposal of non-recyclable materials. This general pattern also provides important reference value for carbon emission mitigation strategies in the end-of-life stage of electrical equipment [44]. For waste disposal, materials that cannot be recycled, such as certain polymer insulation materials and waste oils, may need to be incinerated or landfilled, processes that also release greenhouse gases.

The carbon emission characteristics of the recycling phase are more complex, as they are heavily influenced by the recycling processes and types of materials involved. The recycling efficiency and carbon emission intensity vary significantly among different materials, such as metals, plastics, and composite materials, which is consistent with the “material dependence” characteristic widely discussed in the field of electronic waste recycling [45]. Recycling metal materials in electrical equipment, such as copper, aluminum, and steel, generally has high energy efficiency and can significantly reduce carbon emissions. For example, the energy consumption for recycling copper is only 10–20% of that required for primary smelting, leading to a reduction of approximately 3–4 kg of CO2 equivalent emissions for every 1 kg of copper recycled [34]. The recycling of aluminum can also reduce carbon emissions by over 80%, with higher recycling rates providing more substantial emission reduction benefits. However, some materials, such as insulation resins and composite materials, are more difficult to recycle and often require incineration or pyrolysis treatment. This process not only consumes more energy but may also result in higher carbon emissions. The pronounced disparities in recovery efficiency and carbon emission intensity across materials further corroborate the material-dependent nature of carbon emissions during the recovery stage, providing important implications for targeted emission reduction strategies [46].

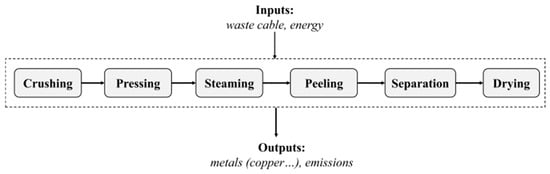

High recycling and remanufacturing rates are considered key strategies for reducing carbon emissions [47]. Specifically, increasing the recycling rate can effectively reduce the demand for primary materials, thereby lowering carbon emissions during the production process. For instance, high recycling rates of metals such as copper and aluminum can replace primary smelting, significantly reducing the carbon footprint. Remanufacturing is another important approach. Especially for equipment such as motors and transformers, remanufacturing not only reduces raw material consumption during manufacturing but also lowers energy consumption. For example, remanufacturing a motor consumes about 20–30% of the energy required to manufacture a new motor, with carbon emissions reduced by 60–80%. Therefore, improving the recycling and remanufacturing rates of electrical equipment is crucial for emission reduction. Figure 6 shows the system boundary for the reuse of waste cables. Establishing a sound recycling system and supply chain is key to achieving high recovery rates, while policy incentives and ecodesign play a significant role in facilitating this process [48].

Figure 6.

The system boundary for the reuse of waste cables [47].

The carbon emission characteristics of the decommissioning and recycling phase are influenced by factors such as recycling technologies, material types, and recycling rates. Enhancing the recycling efficiency of metals is crucial for reducing carbon emissions across the entire life cycle of electrical equipment. As recycling technologies continue to advance and the remanufacturing industry grows, carbon emissions from electrical equipment are expected to be further controlled and reduced in the future.

3.4. Total Carbon Emissions Across Life Cycle Stages

Electrical equipment involves multiple stages throughout its life cycle, including raw material extraction, manufacturing, transportation and installation, operation and maintenance, and decommissioning and recycling. The carbon emissions contribution from each stage varies significantly. Overall, the manufacturing stage typically dominates life cycle carbon emissions, particularly for material-intensive products such as transformers, switchgear, and energy storage equipment. The production of core materials like silicon steel, copper, aluminum, and insulation materials is energy-intensive, often accounting for 40–70% of the total life cycle emissions [49]. The smelting and processing of metal materials are the primary sources of emissions, and the complexity of the equipment structure, along with the weight of the materials, further increases the carbon emission intensity of this stage. The adoption of low-carbon smelting technologies, such as electric arc furnace steelmaking and inert anode aluminum electrolysis, can significantly reduce carbon emission intensity at the metal raw material stage from the source. Electric arc furnace steelmaking avoids coke consumption through the recycling of scrap steel, while inert anode aluminum electrolysis eliminates direct process emissions via electrode material innovation. Together, these technologies provide critical process-level support for carbon emission reduction across the entire life cycle of electrical equipment [46].

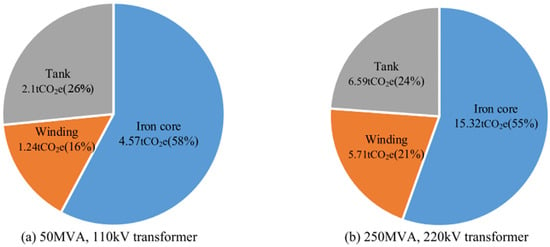

Carbon emissions during the operational phase vary depending on the type of equipment. For long-term operating devices, such as power transformers and power electronic devices, electrical losses (such as core losses and copper losses) account for a significant portion of their life cycle carbon emissions, typically ranging from 20% to 40% [50]. These emissions are closely tied to operating efficiency, load factor, and equipment aging, so improving energy efficiency is a key approach to reducing life cycle carbon emissions. In contrast, for equipment that either consumes no energy or very little energy during operation, such as certain primary switchgear, the carbon emissions during the operational phase are relatively low. Figure 7 shows the proportion of greenhouse gas emissions from transformers at different voltage levels.

Figure 7.

The proportion of greenhouse gas emissions from transformers at different voltage levels [50]: (a) 50 MVA, 110 kV; (b) 250 MVA, 220 kV.

The transportation and installation phases typically account for a small proportion of total emissions (generally less than 5%). However, for large equipment, such as ultra-high voltage transformers and offshore wind power electrical equipment, long-distance transportation and hoisting processes can lead to additional carbon emissions, which should be considered in the assessment [51]. Although direct emissions during the decommissioning and recycling phase are relatively limited, this phase plays a critical role in life cycle carbon reduction. High recycling and remanufacturing rates can significantly reduce the demand for primary materials, resulting in substantial avoided emissions (carbon reduction benefits). Some studies suggest that the recycling phase can offset 10–30% of the emissions from the production stage [34].

The life cycle carbon emissions of electrical equipment are characterized by manufacturing dominance, significant operational impact, and a notable contribution from recycling. By systematically quantifying emissions at each stage, key carbon emission hotspots can be identified, providing a scientific foundation for optimizing equipment design, material substitution, improving energy efficiency, and developing recycling strategies.

4. Carbon Mitigation Pathways and Strategies

4.1. Low-Carbon Design and Material Optimization

Low-carbon design [52] is an approach focused on minimizing carbon emissions throughout the entire life cycle of a product. This concept emphasizes addressing carbon emission factors at every stage, from product design and material selection to manufacturing processes, usage, and disposal. The essence of low-carbon design is to optimize resource efficiency, reduce energy consumption, and minimize waste generation, thereby lowering the overall carbon footprint [53].

In electrical equipment manufacturing, low-carbon design can be applied in several ways. For example, by selecting materials with higher energy efficiency and lower environmental impact, optimizing product structural design, and reducing material waste and energy consumption. Additionally, low-carbon design promotes the use of renewable resources and recyclable materials, which helps reduce environmental burdens at the product’s end-of-life stage.

Material selection is a crucial aspect of low-carbon design. Traditional materials are often linked to higher carbon emissions, so finding low-carbon alternative materials is a key strategy for reducing emissions during the manufacturing phase [54].

High-conductivity copper is an advanced material with superior performance, offering significantly higher electrical conductivity than traditional copper materials. The advantage of this material is that it enables the use of conductors with smaller cross-sections under the same current conditions, thus reducing material usage and energy consumption during the manufacturing process. By minimizing resistive losses, high-conductivity copper not only improves power transmission efficiency but also lowers operating costs and overall carbon emissions of electrical equipment. In electrical equipment such as motors and transformers, replacing traditional copper with high-conductivity copper can enhance equipment performance while achieving substantial carbon emission reductions over long-term operation.

Low-loss silicon steel [55] is a high-quality material widely used in the electrical equipment industry, particularly in the core parts of motors and transformers. Compared to conventional silicon steel, low-loss silicon steel significantly reduces iron losses and eddy current losses through optimal alloy composition and heat treatment processes, thereby improving energy efficiency. During the operation of electrical equipment, iron and eddy current losses are major sources of energy waste. The use of low-loss silicon steel can enhance the overall energy efficiency of equipment, reduce energy consumption, and lower carbon emissions [56]. The application of this material not only improves the performance of electrical equipment but also supports global low-carbon economic development goals.

Low-carbon design and material optimization offer significant value in the manufacturing of electrical equipment. By incorporating advanced materials such as high-conductivity copper and low-loss silicon steel, product performance can be enhanced while effectively reducing carbon emissions during the manufacturing phase. With ongoing advancements in technology and materials science, the concept of low-carbon design will expand its applications in the future, driving the electrical equipment industry toward a greener and more sustainable path.

Driven by both policies and market forces, companies should actively explore innovative approaches to low-carbon design and material optimization, aiming to achieve a win-win outcome for both economic and environmental benefits, while supporting global efforts to address climate change.

4.2. Carbon Reduction in Manufacturing Processes

Clean energy [57] and low-carbon processes play a vital role in the manufacturing of electrical equipment. The use of renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, and hydro power can significantly reduce carbon emissions during production. By optimizing production processes and adopting low-carbon technologies, energy efficiency can be improved, and carbon emissions per unit of product can be reduced. The integration of clean energy and low-carbon processes not only helps reduce carbon emissions but also boosts production efficiency. By refining the energy structure and improving manufacturing processes, enterprises can achieve efficiency gains while maintaining product quality.

In recent years, as carbon neutrality goals advance in manufacturing, an increasing number of companies have been exploring energy structure optimization. Specifically, in the field of electrical equipment manufacturing, integrating clean energy has become a key strategy for achieving low-carbon transformation in production processes. Research has shown that incorporating renewable energy into industrial processes can not only significantly reduce carbon emissions per unit of product but also enhance energy security and economic stability [58]. The following section will discuss the specific applications and emission reduction effects of solar, wind, and hydro energy in electrical equipment manufacturing.

In electrical equipment manufacturing plants, the installation of solar photovoltaic systems can supply a portion of the electricity needed for production. By converting solar energy into electricity, the plant reduces its reliance on traditional fossil fuels, thereby lowering carbon emissions [59]. For example, some factory rooftops are equipped with photovoltaic systems that provide stable electricity during peak summer periods, further reducing electricity costs.

Wind energy, as a clean energy source, is well-suited for production environments with high electricity demands. By installing wind turbines, manufacturing enterprises can achieve self-sufficiency in regions rich in wind resources, reducing dependence on external power grids. The integration of wind energy not only lowers electricity procurement costs but also effectively reduces carbon emissions [60].

Hydropower is a mature clean energy source, particularly in regions with abundant water resources, where hydropower stations can provide stable, low-carbon electricity. In electrical equipment manufacturing, using hydropower as the primary energy source can significantly reduce carbon emissions during the production process.

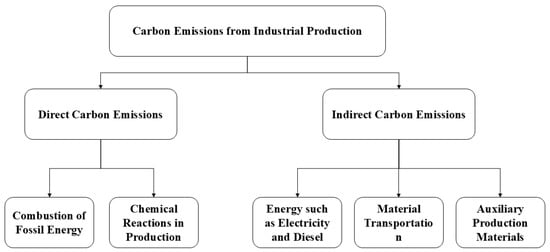

In industrial production, 70% of carbon emissions come from the combustion of fossil fuels and electricity consumption, while some emissions result from the auxiliary materials required in the manufacturing process [61]. Based on the source of emissions, carbon emissions in industrial production can be divided into two categories: direct carbon emissions and indirect carbon emissions. Direct carbon emissions result from the direct burning or use of fossil fuels in industrial production, leading to greenhouse gas emissions. Indirect carbon emissions are caused by the consumption of electricity in industrial production and the greenhouse gas emissions from the production of auxiliary materials such as cutting fluids, lubricants, and tools. Based on the analysis above, the categorization of carbon emissions in industrial production is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The categorization of carbon emissions in industrial production.

In the manufacturing of electrical equipment, using high-efficiency equipment and energy-saving technologies is a key strategy for reducing carbon emissions. For example, employing high-efficiency motors and frequency converters can significantly reduce electricity consumption.

Improving heating and cooling processes by using high-efficiency heat exchangers and insulation materials is another effective way to reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions. Advanced manufacturing technologies, such as additive manufacturing (3D printing) and smart manufacturing, also play a crucial role in optimizing material use and improving production efficiency. Additive manufacturing helps minimize material waste during processing and lowers energy consumption by precisely controlling manufacturing parameters. In addition, smart manufacturing boosts production flexibility and efficiency through data analysis and automated control, contributing to reduced energy consumption and carbon emissions.

Green manufacturing processes, including solvent-free coating and low-temperature welding, offer further opportunities to lower carbon emissions during production. Solvent-free coating technology reduces not only Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) emissions but also energy consumption. Similarly, low-temperature welding technology enables welding to be completed at lower temperatures, which further decreases energy consumption.

In electrical equipment manufacturing, adopting the concept of Life Cycle Management (LCM) allows companies to factor in carbon emissions from the design stage, helping to reduce emissions during production through design optimization and material selection. By applying LCA [57], companies can identify carbon emission hotspots at each stage, enabling them to implement targeted improvements for effective emission reductions.

4.3. Carbon Reduction During Usage

The usage phase of electrical equipment is the most significant stage for carbon emissions throughout its life cycle, typically accounting for over 60% of total emissions, and even more for long-term operating equipment such as transmission and transformation devices and motor systems. These emissions primarily result from indirect carbon emissions due to the electricity consumed during equipment operation. As such, the main focus for emission reduction is on improving energy efficiency, optimizing operations, and implementing intelligent control. Through technological innovation and management upgrades, a low-carbon operation can be achieved across the entire life cycle.

The most effective way to reduce carbon emissions during the usage phase of electrical equipment is by improving energy efficiency. Using high-efficiency motors, variable frequency drive (VFD) systems, and optimizing equipment matching can significantly cut electricity consumption. As noted by Sundaramoorthy et al., industrial motors and drive systems account for about 17% of total energy use and 21% of carbon emissions in U.S. manufacturing industries [62]. Additionally, combining variable frequency drives with high-efficiency motors is recognized as an effective strategy to reduce both carbon footprints and costs [63].

In power transmission and transformation systems, smart grid technology plays a crucial role in supporting emission reductions during the usage phase. By establishing a coordinated scheduling system for source-grid-load-storage, power supply and demand can be balanced in real-time, minimizing carbon emissions from electrical equipment operating inefficiently. For example, in transformer operation, the traditional fixed-load mode often leads to increased losses at light loads (no-load losses can account for up to 40% of total losses). However, with dynamic load adjustment technology based on smart grids, transformer operations can be optimized by real-time monitoring of electricity demand, maintaining the load in the 70–80% efficiency range. A single 110 kV transformer can reduce carbon emissions by approximately 12 tons per year. Additionally, the widespread adoption of smart meters and energy consumption monitoring devices enables detailed energy management for industrial motors, distribution equipment, and other systems. This helps users identify inefficiently operating equipment and reduce electricity losses by an average of 8–15%. Moreover, research on transformers in distribution networks has shown that carbon emissions during the operation phase can account for over 90%, emphasizing the significant emission reduction potential during the usage period [64].

Figure 9 shows the carbon flow energy structure diagram for sustainable development goals.

Figure 9.

Energy structure diagram of the SDG with carbon flow [65].

The application of smart operations and maintenance (O&M) technology further extends the efficient operating period of electrical equipment, thereby indirectly reducing carbon emissions. By leveraging the Internet of Things (IoT) and condition monitoring sensors, key parameters such as equipment temperature, vibration, and insulation performance can be collected in real-time. This enables early detection of potential failure risks, helping to prevent energy waste and a surge in carbon emissions caused by unexpected downtime. For example, with high-voltage cables, the traditional periodic inspection approach tends to have a relatively high fault detection delay. In contrast, a smart O&M system using distributed fiber optic sensors can improve fault location accuracy to within 10 m, reducing fault handling time by 60%. This results in an average reduction of about 3.2 tons of additional carbon emissions per year from a single 10 kV cable due to faults. Furthermore, by creating a virtual operational model of equipment using digital twin technology, energy consumption and carbon emission levels under various operating conditions can be simulated, offering decision support for optimizing operating parameters. For instance, a wind farm utilized this technology to optimize its wind turbine pitch control strategy, increasing turbine generation efficiency by 5%, which led to a reduction of approximately 800 tons of carbon emissions per year [66].

Extending the service life of equipment is another crucial pathway for reducing emissions during the usage phase. The service life of electrical equipment is directly linked to the quality of its operation and maintenance. Effective maintenance can extend the actual life of equipment by 10–20% beyond its designed lifespan, reducing carbon emissions associated with early equipment replacement and manufacturing. For example, high-voltage circuit breakers can extend their service life from 20 years to 25 years through regular insulation testing and mechanical maintenance. This not only avoids the need for one equipment replacement but also prevents approximately 5 tons of carbon emissions that would have been generated during the manufacturing phase.

Additionally, the energy efficiency reassessment mechanism before equipment decommissioning is essential. For equipment that still meets basic operational requirements but has low energy efficiency, improvements can be made by adding energy-saving attachments, such as motor frequency converters, instead of replacing the equipment. For example, an industrial park installed frequency converters on 100 old motors, reducing carbon emissions by approximately 200 tons per year, at only 30% of the cost required to replace the motors with new ones [67].

4.4. Circular Economy and Equipment Recycling

Driven by global carbon neutrality goals, the electrical equipment industry has become a crucial part of the low-carbon transformation of energy systems, owing to its material intensity, long operational life, and increasing decommissioning rates. Core equipment such as transformers, transmission lines, and switchgear generates significant greenhouse gas emissions during the production of materials, manufacturing, operation, and decommissioning stages [18,50]. Therefore, by increasing recycling rates, expanding remanufacturing applications, and optimizing recycling technologies, carbon emissions throughout the entire life cycle can be substantially reduced, contributing to the development of a circular economy.

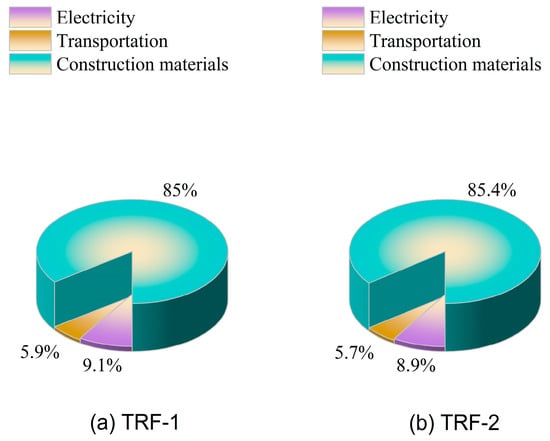

Electrical equipment is primarily made of metals such as copper, aluminum, and silicon steel, whose primary smelting processes are energy-intensive and generate significant carbon emissions [39]. Life cycle studies of transformers indicate that the material stage contributes a substantial portion of total emissions [18], as shown in Figure 10. Therefore, increasing the recycling rate of metals is a key strategy for reducing upfront carbon emissions.

Figure 10.

Carbon Emission Contributions from Primary Sources during the Production [18]: (a) Percentage contribution of primary CO2-eq emission sources during the production of TRF-1. (b) Percentage contribution of primary CO2-eq emission sources during the production of TRF-2.

Industry practices show significant potential for recycling metal materials in transformers. The International Copper Association (ICA) notes that core metals like copper maintain nearly unchanged performance during recycling, allowing for high recycling rates and a significant reduction in carbon emissions. The World Steel Association (2021) [68] also highlights the strong recycling value of silicon steel sheets and structural steel. By establishing a comprehensive recycling system that includes decommissioning registration, dismantling enterprises, and recycling plants, and integrating digital identification and material flow tracking technologies, high-purity metal separation and reuse can be achieved, significantly reducing carbon emissions throughout the equipment life cycle.

Recycling is particularly critical for SF6-containing switchgear. The IPCC AR6 (2021) [69] clearly states that SF6 has a very high global warming potential. Therefore, sealed dismantling and gas recovery technologies are essential to prevent greenhouse gas leakage while increasing the reuse rate of SF6, which significantly reduces emissions during the recycling phase.

Remanufacturing involves standardized dismantling, testing, and repair, restoring decommissioned equipment’s performance to near-new condition. Literature indicates that remanufacturing can result in significant savings in both energy consumption and material use [70]. In electrical equipment remanufacturing, components with high emissions, such as cores and housings, can be retained, thus reducing implicit emissions in the supply chain phase [26].

Remanufacturing relies not only on process capabilities but also on support from standardized systems, including component testing, performance evaluation, and carbon footprint accounting. By leveraging third-party certification and quality management, market trust can be enhanced, and the adoption of remanufactured equipment can be expanded, further amplifying emission reduction benefits across the industry.

Traditional recycling methods face challenges such as low dismantling efficiency, low material purity, and high energy consumption, which limit their potential for emission reduction. However, the use of technologies such as automated dismantling, X-ray sorting, and electromagnetic separation can improve the accuracy of material separation (e.g., copper, aluminum, and steel) while reducing energy consumption during recycling [71]. For complex components, such as composite material insulators, a combination of chemical and physical separation methods can be employed to enable the recycling of non-metal materials.

At the same time, optimizing the energy structure of the recycling system is crucial for reducing indirect emissions. By introducing renewable energy to power disassembly and sorting equipment, a low-carbon recycling system will be established, further unleashing the emission reduction potential of the recycling process.

In fact, the three stages of production, use, and recycling/remanufacturing are not isolated but are closely coupled and coordinated. Given the high proportion of carbon emissions during the material stage [18], the product design stage should emphasize dismantlability and material optimization. The end-stage recycling and remanufacturing process, through resource recycling, feeds back to the earlier stages, reducing the demand for raw materials and new equipment. This closed-loop system facilitates the synergistic effect of the three stages: low-carbon design during production establishes the foundation for recycling, extended product life in the usage phase reduces the replacement pressure, and resource recycling ensures the supply of raw materials for emission reduction at the front end. Together, they form a systematic model of low-carbon production, efficient operation, and resource recycling, providing long-term momentum for deep emission reduction in the industry.

To achieve deep decarbonization within this closed-loop system, it is essential to go beyond the limitations of individual stages and adopt a hybrid lifecycle assessment-optimization framework, integrating environmental evaluation directly into system-level decision-making. Research shows that this framework can effectively balance the technical feasibility, economic costs, and environmental goals throughout the entire lifecycle of the system. In practice, Çiçek et al. [72] used Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) to integrate railway regenerative braking energy and idle capacity of traction transformers for electric vehicle charging. This strategy not only optimized multi-source energy management but also significantly reduced redundant infrastructure investment and carbon footprint during the operational phase. Meanwhile, Al-Sahlawi et al. [73] developed a multi-objective improved arithmetic optimization algorithm (MOIAOA) to optimize the capacity configuration of photovoltaic, wind power, and battery systems, successfully coordinating conflicting lifecycle objectives such as Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE), Grid Contribution Factor (GCF), and Electricity Sales (ESOLD), achieving an optimal design balancing both economic viability and renewable energy utilization.

In conclusion, improving recycling rates, expanding remanufacturing applications, and combining advanced system optimization algorithms are key strategies for achieving carbon reduction throughout the entire lifecycle of electrical equipment. By combining policy guidance, standardized management, and technological innovation, a resource-efficient recycling industry ecosystem can be built, providing strong support for the carbon neutrality goals of energy systems.

4.5. Policy Incentives and Industry Standards

Policy incentives and industry standards play a crucial role in driving the green transformation of the electrical equipment industry, acting as key institutional frameworks for global low-carbon development. Countries are creating systems that combine policy guidance and standard regulations, which not only help enterprises develop carbon reduction strategies and technological solutions but also accelerate the research, development, and widespread adoption of low-carbon electrical equipment through market mechanisms and regulatory measures. This system has a particularly significant impact on lifecycle emissions, as the implementation of policies and standards directly determines the emission reduction pathways of enterprises and promotes green transformation through measurable indicators.

Policy incentives are essential in driving the green transformation of businesses. For instance, in China, the Action Plan for Accelerating the Green and Low-Carbon Innovative Development of Electric Power Equipment was jointly issued by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and five other departments. This plan designates power equipment as a key sector and supports the green remanufacturing and low-carbon innovation of core equipment, such as transformers and switchgear. Furthermore, during the 14th Five-Year Plan period, China proposed encouraging power grid companies to incorporate carbon footprint indicators into their procurement processes through subsidies, fiscal support, and other measures. This policy not only incentivizes enterprises to adopt low-carbon technologies through subsidies and financial support but also directly impacts the measurement and control of carbon emissions throughout the lifecycle of equipment through carbon footprint requirements, ensuring that emission reduction effects at each stage are effectively implemented.

At the international level, the European Union has implemented the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and introduced the CBAM, which imposes carbon costs on high-emission products. This mechanism encourages both domestic and international businesses to adopt energy-saving technologies [74]. It not only compels foreign manufacturers to green their operations through price signals but also helps prevent carbon leakage, having a profound impact on carbon emissions throughout the product lifecycle. For ex-ample, the EU mandates carbon footprint reporting requirements, requiring importers to provide carbon footprint data for the entire lifecycle of a product, from production to recycling, with emissions quantified at each stage. Additionally, countries such as the United States and Japan have introduced tax incentives to reward equipment manufacturers that use low-carbon materials and energy-saving processes, further reducing their transformation costs [75].

Industry standards provide structured technical guidelines for low-carbon design and manufacturing. At the international level, ISO standards offer unified metrics for life cycle carbon emissions. For example, ISO 14040/14044 outlines the methodology for LCA, helping enterprises to perform comprehensive carbon footprint calculations from product design, production, and use to retirement and recycling, while ISO 50001 and ISO 14001 help enterprises establish systematic energy and environmental management systems [76], improving production efficiency and enhancing emission reduction capabilities. In China, efforts to develop standards are also progressing. The national standard Quantification Methods and Requirements for Product Carbon Footprint of Greenhouse Gases—Electrical Equipment Products is being implemented, covering the entire life cycle from manufacturing and usage to decommissioning and recycling. The implementation of these standards not only helps clarify the carbon emission requirements at each lifecycle stage of electrical equipment but also encourages enterprises to optimize production and operational processes to reduce their carbon footprint. Additionally, industry-specific carbon footprint calculation rules are being developed for various types of electrical equipment, such as switchgear and transformers. At the enterprise level, the Green and Low-Carbon Evaluation Guidelines for Electrical Equipment Manufacturing Enterprises define comprehensive indicators for carbon accounting, energy-saving technologies, and management systems, providing a standardized framework for evaluating enterprises.

Green manufacturing standards play a crucial role in driving low-carbon upgrades across the entire industrial chain. In China, standards such as GB/T 36132-2018 General Principles for Green Factory Evaluation and GB/T 39223-2020 Green Manufacturing Evaluation Requirements—Electrical Equipment have established evaluation systems covering areas such as raw materials, energy, production, and recycling. These standards guide enterprises in integrating low-carbon principles into the product design stage. ISO 14067, Requirements for Quantifying and Communicating Product Carbon Footprints, provides a universal standard for the international market, encouraging global companies to adopt low-carbon solutions in design, material selection, and manufacturing processes.

These policies and industry standards work together to promote the widespread ap-plication of low-carbon electrical equipment and achieve measurable emission reduction goals through standardized management of lifecycle carbon emissions. For instance, the European Union’s CBAM requires importers to provide carbon footprint reports and gradually bear the carbon costs, which puts significant pressure on exporters, urging them to align with international high standards. Meanwhile, Chinese domestic equipment manufacturers, by implementing carbon footprint standards and green factory evaluations, not only enhance the environmental value of their products but also gain a competitive advantage in the international market. Mutual recognition of standards and policy alignment are driving the development of a globally unified low-carbon technology framework [77].

Figure 11 illustrates the timeline of policy incentives and industry standards, highlighting key milestones in the development of carbon-related regulations and guidelines from 2003 to 2026.

Figure 11.

Policy Incentives and Industry Standards.

5. Conclusions

This review explores the lifecycle carbon emissions of electrical equipment, focusing on the key emission sources at each stage, from material acquisition to decommissioning and recycling. It highlights that, while the manufacturing and usage phases account for the largest share of emissions, the decommissioning and recycling stages also contribute significantly to overall reductions. Effective strategies for reducing carbon emissions include low-carbon design, energy-efficient manufacturing processes, and improvements in recycling and remanufacturing techniques. Specifically, enhancing material efficiency, optimizing energy use during production, and incorporating smart energy management systems during the usage phase are crucial for minimizing emissions. The findings suggest that, by targeting each phase of the lifecycle, substantial reductions in carbon emissions are achievable.

Despite the progress made, several challenges persist in addressing carbon emissions across the entire lifecycle. One key challenge is the lack of large-scale, reliable field data, particularly in the raw material extraction, usage, and decommissioning stages. This data gap limits the accuracy and reliability of carbon footprint assessments, making it difficult to fully understand the impact of each phase. In addition, inconsistencies in boundaries, emission factors, and methodologies across various studies lead to differing results, complicating comparisons and hindering progress toward standardized carbon assessments. The complexity of quantifying emissions during the usage phase is especially challenging, as factors like equipment load, maintenance, and operation directly influence emissions but are often difficult to measure accurately. Furthermore, recycling and remanufacturing technologies are not yet advanced enough to adequately control emissions during the decommissioning phase, particularly for materials like polymers and composites. To overcome these challenges, it is essential to establish standardized data collection methods, build a unified LCA database, and encourage international collaboration to improve assessment accuracy and accelerate the adoption of low-carbon technologies in the electrical equipment sector.

Author Contributions

Investigation, Writing—original draft, S.L.; formal analysis, Y.J.; Data curation, J.Y.; investigation, B.M.; methodology, C.L.; resources, investigation, Z.L.; project administration, Supervision, writing—review & editing, G.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research and Development Project of China Electric Power Research Institute Co., Ltd. (HL83-25-002).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Shuzhen Li, Yingwei Jiang, Jun Yi, Bo Miao and Chao Liu were employed by the China Electric Power Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, N.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.S.; Xue, S.; Yu, Q.; Li, Q. Road life-cycle carbon dioxide emissions and emission reduction technologies: A review. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 9, 532–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Luo, T.; Luo, H.; Liu, R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z. A comprehensive review of building lifecycle carbon emissions and reduction approaches. City Built Environ. 2024, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C.; Williams, I.D.; Turner, D.A. Evaluating the carbon footprint of WEEE management in the UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soust-Verdaguer, B.; Llatas, C.; García-Martínez, A. Critical review of bim-based LCA method to buildings. Energy Build. 2017, 136, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana-Pedraza, G.A.; Vieira-Agudelo, S.C.; Muñoz-Galeano, N. A cradle-to-grave multi-pronged methodology to obtain the carbon footprint of electro-intensive power electronic products. Energies 2019, 12, 3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryshlakivsky, J.; Searcy, C. Fifteen years of ISO 14040: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 57, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkbeiner, M.; Inaba, A.; Tan, R.; Christiansen, K.; Klüppel, H. The new international standards for life cycle assessment: ISO 14040 and ISO 14044. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2006, 11, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Xia, B.; Wang, X. The contribution of ISO 14067 to the evolution of global greenhouse gas standards—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnveden, G.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Ekvall, T.; Guinée, J.; Heijungs, R.; Hellweg, S.; Koehler, A.; Pennington, D.; Suh, S. Recent developments in life cycle assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuss, P.; Eckelman, M.J. Life cycle assessment of metals: A scientific synthesis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J. Carbon Footprint Calculation for Power Transmission and Distribution Equipment: A Comprehensive Review of Methodologies, Standards, and Applications. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. Adv. 2025, 28, 200295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaynak, E.; Piri, I.S.; Das, O. Revisiting the Basics of Life Cycle Assessment and Lifecycle Thinking. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Das, B.B. Life Cycle Assessment of construction materials: Methodologies, applications and future directions for sustainable decision-making. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxha, E.; Maierhofer, D.; Saade, M.R.M.; Passer, A. Influence of technical and electrical equipment in life cycle assessments of buildings: Case of a laboratory and research building. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 852–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Resources Institute (WRI); World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). The Greenhouse Gas Protocol: A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard; WRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, G.; Wang, W.; Wu, W.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Y. Carbon emission prediction model for the underground mining stage of metal mines. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Teng, F.; Tong, Q. Mitigating sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) emission from electrical equipment in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, T.; Markowska, D. Carbon Footprint of Power Transformers Evaluated Through Life Cycle Analysis. Energies 2025, 18, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]