3.2. Author Co-Occurrence and Co-Citation Network Analysis

Table 1 ranks the 20 most productive authors in the field of REE research based on the number of publications in Web of Science (1975–2024), revealing a concentration of scholarly output among a select group of influential researchers. Leading the list is Poettgen, Rainer with 249 publications, followed by Santosh, M (213); Jiang, Shao-Yong (124); Qu, Xiaogang (120); and Wu, Fu-Yuan (118), all of whom have made significant contributions to REE mineralogy, geochemistry, and materials science. Notably, Huang, Fuqiang (113); Sun, Lingdong (111); and Ren, Jinsong (110) represent prominent Chinese researchers whose work reflects the country’s sustained interest and investment in REE-related technologies and resource development. Hower, James (109) and Bau, Michael (108) are internationally recognized for their contributions to coal-related REE studies and marine geochemistry, respectively. Other notable contributors include Wang, Limin (106); Song, Shuyan (101); and Dai, Shifeng (98), the latter being a key figure in REE-enriched coal research. Scholars such as Binnemans, Koen (93) and Liu, Xiaojuan (92) have advanced REE separation and recycling processes, while Shi, Yanqi (91); Xue, Dongfeng (85); and Zhou, Mei-Fu (82) have extensively investigated REE-bearing mineral systems. Pioneering work by Sobolev, B. P. (80) and Griffin, W.L. (73) further underscores the multidisciplinary breadth of REE research, spanning from petrogenesis to advanced materials. This author-based analysis highlights the global distribution and thematic diversity of REE research, evidencing both academic leadership and emerging research frontiers.

The top 20 most cited publications in REE-related research (

Table 2) represent key intellectual figures whose foundational contributions have shaped the development of the field across geochemistry, mineralogy, and materials science. Leading the list is Troullier, N. with 15,063 citations, widely recognized for pioneering work in density functional theory and pseudopotential methods, which are extensively applied in REE-bearing materials. Hoskin, P.W.O. (4410 citations) is known for his influential studies on zircon geochronology and trace element partitioning, particularly relevant to REE behavior in accessory minerals. Taylor, S.R. (3819 citations) made seminal contributions to crustal geochemistry and REE distribution models, while Catalan, G. (3711 citations) has advanced the understanding of ferroelectric and multiferroic materials incorporating REE.

Liu, Y.S. (3490 citations) and Belousova, E.A. (2491 citations) have notably influenced analytical geochemistry through LA-ICP-MS zircon analyses, providing crucial insights into REE partitioning and crustal evolution. Trovarelli, A. (3246 citations) and Subramanian, M.A. (1943 citations) significantly contributed to REE applications in catalysis and functional materials, including perovskites and pyrochlores. Nan, C.W. (3193 citations) and Ran, J.R. (2217 citations) have emphasized REE-enabled nanotechnology and photocatalysis, showcasing REE’ interdisciplinary importance. Plank, T. (3042 citations) and McLennan, S.M. (2814 citations) provided key models for sedimentary REE behavior and source tracing, including McLennan’s 1989 [

43] work on provenance and sedimentary processes.

Authors such as Coey, J.M.D. (2412 citations); Pearce, N.J.G. (2476); and Martin, H. (2481) have each anchored mineralogical and petrological studies involving REE, while Huang, Y.Y. (2565 citations) and Wang, X. (2454) have made notable advances in REE-doped luminescent materials. Stevens, W.J. (2200 citations) is renowned for quantum chemistry methods relevant to REE bonding environments in materials. These authors collectively represent the core of REE research and are consistently co-cited across disciplinary boundaries, reflecting the field’s multidimensional growth—from analytical geochemistry and crustal processes to materials science and photonics.

3.3. Distribution of Publications by Countries/Regions, Universities, and Departments/Laboratories

Results demonstrate the distribution of publications by country/region in REE research, highlighting national contributions based on publication counts (see

Figure 4). Country and institutional outputs were conducted using full counting, whereby each publication was fully attributed to all contributing countries and institutions. For clarity, the country-level analysis focuses on the top 20 most productive countries in REE research (1975–2024), ranked by publication output using the full-counting method; all other countries were aggregated to improve visualization clarity. Over this period, China emerged as the leading contributor, with 18,456 publications—more than double that of the second-ranked United States (8971). Germany (4926), Russia (4438), Japan (4022), and France (3587) also show strong engagement, reflecting their long-standing involvement in materials science and critical raw materials research. Other significant contributors include Canada (3261), Australia (3054), India (2840), and England (2816), indicating a globally distributed research effort across Asia, North America, and Europe. Countries such as Italy (1797), Poland (1371), Brazil (1350), and Spain (1240) also demonstrate consistent involvement. In East and Southeast Asia, South Korea (1101) has played a notable role, alongside Iran (921) and Turkey (826) from the Middle East. European nations like Switzerland (911), Sweden (830), and Austria (not listed) maintain moderate contributions, while African countries such as Egypt (784) and South Africa (not listed here) also participate. This distribution underscores the global strategic significance of REE and the wide-reaching international collaboration addressing technological, environmental, and economic challenges associated with these critical elements.

Additionally,

Figure 5 illustrates the collaborative relationships among the most productive countries in REE research. The collaboration networks were generated in VOSviewer using association-strength normalization, with a minimum threshold of publication numbers per country to ensure network clarity and robustness. The visualization reveals a well-structured international collaboration landscape comprising several distinct clusters, where node size reflects the number of publications and link thickness indicates the strength of collaborative ties.

The central cluster, prominently featuring China, USA, and Germany, represents the core of global REE research collaboration. China, with the largest node and highest centrality, is clearly the dominant contributor and a central hub, extensively collaborating with both Western and Asian countries. The USA, though slightly peripheral in the cluster, maintains strong ties with countries such as Canada, Australia, and Germany, demonstrating its significant but regionally differentiated influence.

To assess the sensitivity of these findings to the counting approach, the analyses were repeated using fractional counting, in which publication and collaboration weights are proportionally distributed among co-authoring countries. While fractional counting reduces the absolute publication counts and link strengths of highly collaborative countries—most notably China and the USA—the overall country rankings, cluster composition, and core–periphery structure of the collaboration network remain largely unchanged.

Five major regional collaboration clusters can be distinguished by color: Cluster 1 (purple—dominant contributor) is dominated by the largest and most central nodes—China, the USA, Canada, and Australia—indicating their leadership in REE research output and international collaboration. These countries serve as key hubs within the global cooperation network, reflecting their substantial investments in critical mineral research, technological development, and resource security. Their central positioning and strong linkages underscore their pivotal role in shaping the global REE research landscape across both academic and industrial domains.

Cluster 2 (red—Anglosphere and Europe-Oriented): This cluster is centered around England, Australia, the Netherlands, and Belgium, showing strong internal cooperation, especially between Commonwealth countries and European partners. Kazakhstan and Malaysia also appear here, indicating active participation in research partnerships with these nations.

Cluster 3 (green—Asian Collaborators): Comprising India, Japan, South Korea, and Spain, this cluster highlights robust intra-Asian research networks. India and Japan are particularly well-integrated, with significant connections to China and to each other, suggesting coordinated regional research efforts.

Cluster 4 (blue—Emerging Economies and Middle East and Africa): This group includes Brazil, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, and Turkey. These countries show growing involvement in REE research, frequently cooperating with both core (China and USA) and regional partners. Their position between clusters indicates their bridging role in expanding the global REE research network.

Cluster 5 (yellow—Eastern Europe and Peripheral Collaborators): This less dense group features Russia, Romania, Ukraine, and Bulgaria. These countries exhibit modest collaboration levels, mostly linking to central players like China and Germany, reflecting emerging participation in global REE research.

Figure 6 displays the Collaborative network of leading academies/universities in REE research, highlighting the major academic institutions involved and their collaborative linkages. Four prominent clusters can be distinguished: Cluster 1 (red and purple: China–Russia–International Nexus): At the core of the network lies the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), the largest and most central node, signifying its dominant role in REE research collaboration. Closely connected are institutions like the Russian Academy of Sciences, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Zhengzhou University, University of Toronto, and University of Witwatersrand, among others. This cluster underscores the strong research collaboration between China, Russia, and a selection of global institutions. The dense interlinkages within this group suggest coordinated multi-institutional projects and joint authorship on REE-focused studies, indicating a hub-and-spoke model centered on CAS.

Cluster 2 (orange—Elite Chinese Institutions): Institutions such as Lanzhou University and Peking University form a distinct cluster, indicating a sub-network of elite Chinese universities with strong internal collaboration. This group is positioned at the top of the graph and maintains connections with the core CAS cluster, indicating its significant—though more specialized—role in REE research. These institutions may be more focused on theoretical or applied materials science within the broader REE domain.

Cluster 3 (blue and yellow—Engineering and Metallurgical Research): To the right of the network, a blue-colored cluster includes institutions such as the General Research Institute for Nonferrous Metals, Jiangxi University of Science and Technology, Wuhan Institute of Technology, and University of Science and Technology of China. These are more technically oriented institutions, likely involved in applied mineral processing, metallurgy, and industrial-scale REE extraction research. The slightly peripheral positioning suggests specialized but collaborative research trajectories in contrast to the central academic hubs.

Clusters 4 (green and cyan—Geoscience-Oriented Universities): At the lower section of the network, universities such as the China University of Geosciences, Nagoya University, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, and Ocean University of China form two geoscience-driven clusters. These institutions contribute critical work in mineral exploration, sedimentology, and environmental aspects of REE. Their cluster boundaries reflect thematic rather than geographic alignment, emphasizing discipline-specific collaboration over national groupings.

Additionally,

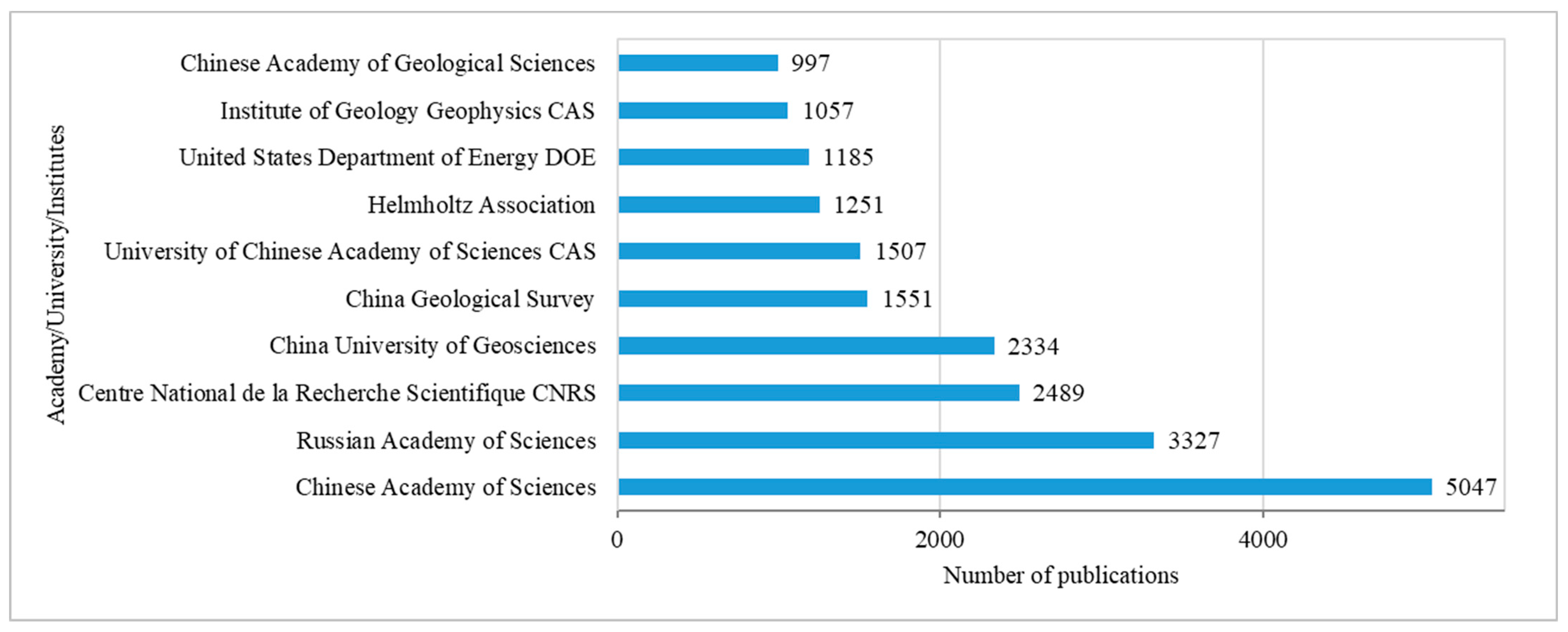

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 present the total publication count of the top 10 academies/universities/institutions and departments/laboratories involved in REE research. Between 1975 and 2024, the global landscape of REE research has been dominated by a set of leading institutions and departments, as recorded in Web of Science. The Chinese Academy of Sciences leads with 5047 publications, followed by the Russian Academy of Sciences (3327), the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) (2489), and major Chinese institutions such as the China University of Geosciences (2334), the China Geological Survey (1551), and the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (1507). Other notable contributors include Germany’s Helmholtz Association (1251), the United States Department of Energy (DOE) (1185), and specialized research arms such as the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, CAS (1057), and the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences (997). At the departmental and laboratory level, the Faculty of Earth Resources at the China University of Geosciences stands out with 478 publications, followed by the State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources (470) and the School of Earth Sciences and Engineering at Nanjing University (468). These are followed by the State Key Laboratory for Mineral Deposits Research (400), departments at Jilin University (386), the Australian National University (381 from the College of Science and 363 from the Research School of Earth Sciences), Northwest University (346), the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (315), and Germany’s University of Münster (272). This distribution reflects a strong Chinese research emphasis on REE exploration and mineralization, alongside significant contributions from European, North American, and Australian institutions—highlighting the global strategic importance of REE in energy, technology, and critical raw materials.

3.4. Distribution of WoS Categories and Discipline Pair Co-Occurrences

The distribution of publications across Web of Science (WoS) categories highlights the inherently multidisciplinary nature of REE research (see

Figure 9). The leading fields—geochemistry (17.4%), materials science (15.8%), and geosciences (13.6%)—demonstrate sustained scientific engagement with REE behavior in natural systems, resource development, and the engineering of advanced materials. Notable representation in mineralogy (10.9%) and metallurgy (9.9%) underscores the importance of mineralogical characterization and metallurgical innovation in REE extraction and processing. Contributions from chemistry (physical: 8.2%; general: 5.3%) reflect ongoing efforts to understand bonding, separation mechanisms, and thermodynamics. The presence of geology (6.7%) and environmental science (6.1%) signals a growing focus on exploration strategies and environmental sustainability. The inclusion of applied physics (5.8%) points to the expanding role of REE in high-tech applications such as magnetics, photonics, and electronics. Collectively, these patterns indicate that REE research is foundational to earth and material sciences, while being increasingly oriented toward technological innovation and sustainable development.

The CDPI quantifies the extent to which a discipline engages with other fields through citations, providing a measure of interdisciplinarity in research. For a primary discipline (D), the CDPI is defined as a normalized citation entropy (4):

where

pi is the proportion of citations from

D to discipline

i; values range from 0 (no cross-disciplinary engagement) to 1 (maximal engagement). To ensure comparability across fields, the CDPI is field-normalized to account for differences in publication and citation volumes, and bootstrapped confidence intervals are used to indicate variability and statistical reliability. Applying this metric to REE-related research over three periods (1985–1999, 2000–2014, and 2015–2024) reveals increasing cross-disciplinary engagement: for example, the geochemistry CDPI rose from 0.45 to 0.74, with strongest links to mineralogy (0.68), while materials science showed high engagement with nanotechnology (0.75) and mineralogy (0.62). Similar trends are observed across geosciences, metallurgy, chemistry, and environmental sciences, reflecting the growing interdisciplinarity of the field.

The CDPI matrix in

Table 3 presents the evolution of cross-disciplinary integration in REE-related research from 1975 to 2024, based on the CDPI across major WoS categories. The three time intervals—1975–1990, 1991–2006, and 2007–2024—highlight how research has progressively integrated diverse scientific domains. Notably, disciplines such as “Geochemistry”, “Mineralogy”, and “Materials Science” demonstrate consistently rising CDPI values, indicating stronger interdisciplinary linkages over time. Geochemistry shows an increase from 0.45 in the early period to 0.74 in the most recent interval, often paired with mineralogy (CDPI: 0.68). Materials science, which emerged prominently after 1990, now exhibits the highest CDPI (0.81), frequently intersecting with “Nanotechnology” and “Mineralogy”. The table also highlights discipline pairings with high co-occurrence, such as “Metallurgy × Chemistry Physical” (0.66) and “Geology × Materials Science” (0.56), emphasizing the collaborative nature of REE research spanning from resource exploration to materials engineering. The increasing involvement of “Environmental Sciences” and “Physics Applied Physics” underscores the growing relevance of REE in sustainable technologies and advanced functional materials. These patterns suggest that the future of REE research will increasingly depend on integrated, cross-disciplinary approaches to address both technological innovation and critical resource sustainability.

3.5. Core Fields Behind REE Research Growth

As revealed by the CDPI matrix, REE research (1975–2024) has evolved toward deep interdisciplinarity, with materials science emerging as the primary driver (CDPI = 0.81). Its frequent co-occurrence with nanotechnology (0.75) and mineralogy (0.68) highlights the focus on nanoscale characterization, functional materials, and REE-based devices in the 2008–2024 period [

17,

44]. Geochemistry, essential for REE exploration, rose from a 0.45 to 0.74 CDPI, often paired with mineralogy (0.68) and metallurgy × physical chemistry (0.66), reflecting the shift from descriptive petrogenesis to integrative, solution-oriented research [

43,

45]. The growing roles of environmental sciences and applied physics signal the field’s alignment with sustainable extraction, tailings valorization, and green technology applications [

41,

46]. Together, these trends confirm that REE research has matured into a strategically interdisciplinary domain linking resource geology, materials science, and sustainability.

The journal co-citation network (

Figure 10) provides strong evidence supporting the CDPI-based interpretation of REE research as an increasingly interdisciplinary field. Five distinct clusters of journals emerge, reflecting the same disciplinary integration trends captured by the CDPI matrix. Cluster 1 (blue) encompasses core geology and geochemistry journals such as “Earth and Planetary Science Letters”, “International Journal of Coal Geology”, and “Fuel”, representing foundational resource-focused studies. Cluster 2 (red) highlights environmental chemistry and analytical science, including “Chemical Geology”, “Plant and Soil”, “Science of the Total Environment”, and “Analytica Chimica Acta”, aligning with the rising CDPI scores of environmental sciences. Cluster 3 (green) and Cluster 4 (purple) illustrate the integration of materials science, metallurgy, and chemical engineering, hosting journals like “Journal of Alloys and Compounds”, “Separation and Purification Technology”, “Metals”, and “Rare Metals”, which reflect the dominant role of materials science (CDPI = 0.81) and its frequent co-occurrence with metallurgy and applied chemistry (0.66). Cluster 5 (light blue), anchored by the “Journal of Rare Earths”, serves as the intellectual nexus that bridges all other clusters, confirming the CDPI finding that REE research is no longer siloed but strategically interdisciplinary. This co-citation evidence reinforces the CDPI concept by demonstrating that knowledge production in REE is organized into interconnected thematic communities that reflect both disciplinary specialization and cross-domain integration [

17,

43,

44].

Table 4 provides clear evidence that geoscience and materials science are the foundational disciplines driving the advancement of REE research. This is demonstrated by the prominence of leading authors whose work centers on mineralogy, geochemistry, and material applications, as well as by the most cited papers that integrate analytical geochemistry techniques and computational materials science approaches. Furthermore, the data highlights a strong global leadership structure, where prolific researchers and high-impact publications form the intellectual backbone of the field. This leadership is further reinforced by the concentration of research activity within top institutions, notably the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Russian Academy of Sciences, and CNRS, which serve as interdisciplinary hubs bridging geology, environmental science, and material innovation. National contributions reveal a dominant role of China in publication volume and international collaboration, supported by substantial input from the USA and European countries, which contribute significantly through technological expertise and interdisciplinary research efforts. The primary journals where these findings are published reflect the integrative nature of REE research, combining domains such as earth sciences, chemistry, and materials engineering. Altogether, this evidence underscores a highly collaborative, multidisciplinary, and geographically diverse research ecosystem, with geoscience and materials science at its core, fueling both fundamental understanding and technological applications of REE globally.

The keyword co-occurrence network (

Figure 11) provides strong supporting evidence for the disciplinary integration and thematic diversity of REE research, directly illustrating how geoscience and materials science intersect with environmental and technological studies. The network is organized into four distinct color-coded clusters, each representing a core research focus: Cluster 1—green (extraction and recovery technologies): Focused on keywords like rare earth, lanthanides, acid, extraction, recovery, adsorption, separation, removal, and recycling, this cluster demonstrates the central role of physicochemical processes and industrial techniques for REE recovery from ores, wastes, and secondary resources. Terms like neodymium, enrichment, and waste emphasize the relevance of recycling and circular economy strategies in modern REE research. Cluster 2—red (environmental geochemistry and speciation): Dominated by keywords such as rare earth elements, fractionation, heavy metals, trace elements, speciation, accumulation, geochemistry, complexation, and soil, this cluster reflects the environmental behavior, distribution, and risk assessment of REE in natural systems. It supports the growing importance of mobility, bioavailability, and ecotoxicology in geoscience-led REE research. Cluster 3—blue (mineralogical and geological aspects): Featuring terms such as monazite, uranium, solubility, leaching, precipitation, and resources, this cluster captures the fundamental mineralogical and geochemical basis of REE exploration. Keywords like sorption and minerals highlight studies on primary REE sources, mineral–host interactions, and experimental geochemistry, underpinning resource identification and extraction strategies. Cluster 4—yellow (materials science and coal research): Although smaller, this cluster—centered on keywords like microstructure, coal, and behavior—illustrates the emerging integration of materials science and unconventional REE sources. It reflects rising interest in REE in coal and coal by-products, along with structural and physicochemical analyses using advanced material characterization techniques. Collectively, these clusters provide a conceptual framework confirming that REE research is inherently multidisciplinary, with geoscience and materials science forming its core. They demonstrate how the field encompasses resource recovery, environmental geochemistry, mineralogical fundamentals, and innovative material applications—together driving the strategic development of REE in both scientific and industrial contexts.

3.6. Global Distribution and Funding Trends in REE Research

The global distribution of REE research between 1975 and 2024 has been shaped by a highly concentrated linguistic distribution and a small number of dominant publishers.

According to the WoS database (see

Table 5), English overwhelmingly dominates scientific publishing, accounting for 73,372 publications, far surpassing all other languages. The next most common languages are Chinese (1729), Russian (968), German (206), and Japanese (189), followed by French (103), Spanish (43), Ukrainian (29), Korean (26), and Polish (26). This distribution underscores the global role of English as the primary language of scientific communication and reveals the limited visibility of non-English publications in international citation databases. The dominance of English in WoS highlights the need for greater multilingual inclusivity and improved representation of regional research outputs in global science.

Academic publishers, shown in

Table 6, reveal a highly concentrated distribution of REE-related publications. Elsevier leads by a wide margin with 22,556 publications, reflecting its strong portfolio in materials science, geochemistry, environmental science, and engineering. Springer Nature follows with 5718 publications, and Wiley with 2977, both contributing significantly through interdisciplinary and chemistry-focused journals. MDPI, with 2222 publications, stands out as a key open-access platform supporting rapid dissemination of REE research. Other notable contributors include the American Chemical Society (ACS) with 1655 publications, focusing on REE-related chemical synthesis and analysis, and Taylor & Francis (1549), which supports environmental and industrial research. The Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) adds 1225 publications, particularly in inorganic and materials chemistry. Science Press (China) contributes 1035 publications, reflecting China’s strategic investment in REE research. IOP Publishing Ltd. (827) and IEEE (775) highlight the role of REE in physics and electronic applications. This concentration of output among a few major publishers underscores their central role in shaping global visibility and access to REE research.

Table 7 highlights the top ten funding agencies supporting REE-related research globally. The National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) is the dominant contributor, funding 9971 publications, reflecting China’s strategic emphasis on rare earth elements for technological and economic development. The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) ranks second with 1639 publications, supporting fundamental research across geosciences, materials, and environmental science. China’s National Key Research and Development Program follows with 1207 publications, focusing on innovation and industrial applications. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), with 1072 publications, emphasizes REE in energy-critical technologies, including batteries, magnets, and clean energy systems. Similarly, China’s Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities support institutional research, contributing 1067 publications. Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) funds 1052 publications, promoting interdisciplinary studies in materials and energy. China’s National Basic Research Program (973 Program) follows with 1027 publications, underscoring its role in foundational research. The Spanish Government (970 publications), Canada’s NSERC (951), and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (928) round out the list, each playing a significant role in advancing REE science within their national priorities. This funding landscape highlights the leadership of China, followed by the U.S., Japan, and several Western agencies, reflecting both strategic priorities and global competition in REE innovation.

Additionally,

Table 8 presents the top ten conferences contributing to REE-related scientific output. The International Conference on f-Elements (ICFE) dominates the list, with its 6th edition (167 records), 2nd edition (138), 5th edition (101), 3rd edition (80), and 4th edition (42) all ranking among the highest. These conferences are central platforms for discussing the chemistry, physics, and applications of rare earth and actinide elements. The 3rd International Winter Workshop on Spectroscopy and Structure of Rare Earth Systems ranks fifth (78 records), emphasizing the structural and spectroscopic properties of REE-bearing compounds. Other notable events include the RARE EARTHS 2004 Conference (53 records) and the 2nd International Symposium on Fundamental Aspects of Rare Earth Elements Mining and Separation and Modern Materials Engineering (45 records), both reflecting industrial and applied aspects of REE extraction and processing. Finally, the 13th and 15th SGA Biennial Meetings (27 and 35 records, respectively) highlight REE in the broader context of economic geology and sustainable mineral resource development. These conferences collectively demonstrate the vibrant global community engaged in REE research, spanning fundamental science, applied technology, and resource sustainability.

3.7. Process Evolution of REE Deposit Discoveries and Their Bibliometric Reflections

The evolution of REE deposit discoveries from 1975 to 2024 mirrors the dynamic interplay between geological understanding, industrial demand, and strategic resource planning. As summarized in

Table 9, five decades of exploration and research have progressively diversified the recognized types of REE-bearing deposits, moving from classical carbonatite and placer systems to highly specialized and unconventional resources. These transitions are also mirrored in the thematic and temporal patterns observed through bibliometric analyses, indicating a clear correlation between real-world resource challenges and academic research focus.

In the earliest phase (1975–1984), REE exploration was dominated by classical deposits, particularly carbonatite-hosted systems and placer monazite. This period saw the sustained exploitation of Mountain Pass (USA) and the emergence of Bayan Obo (China) as the world’s principal REE supplier [

47,

48]. These deposits were rich in light REE, particularly La, Ce, Nd, and Pr. Concurrently, traditional monazite-bearing placer deposits in India, Brazil, and Australia supported industrial supply chains. Bibliometric data for this period reveals dominant keywords such as “monazite,” “bastnäsite,” and “carbonatite,” confirming a focus on high-grade, established mineral systems.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s (1985–1994), attention began to shift toward more complex and less conventional systems. Research on peralkaline igneous complexes such as Ilímaussaq (Greenland) and Lovozero (Russia) advanced the understanding of REE mineralization associated with eudialyte and other exotic minerals [

8,

49]. Simultaneously, geoscientists in China recognized a new class of heavy REE-enriched ion-adsorption clay deposits in the weathering crusts over granitic rocks in Jiangxi Province [

50]. These deposits, though low-grade, offered exceptional economic potential due to their easy leachability and high content of critical heavy REE like Dy and Y. The emergence of keywords such as “adsorption,” “weathering,” and “granite” in co-occurrence networks from this period corroborates the geoscientific pivot toward these alternative sources.

During 1995–2004, research on REE expanded into new geological environments. This included investigations into iron oxide–copper–gold (IOCG) deposits, such as at Olympic Dam in Australia, where REE are hosted in monazite and apatite alongside Cu, Au, and U [

51,

52]. This period marked the rise of multi-commodity exploration strategies that linked REE with hydrothermal systems. Additionally, renewed attention was given to secondary monazite-rich placer systems in Madagascar and Southeast Asia [

53]. While bibliometric evidence shows that “IOCG” remained a niche research theme, this decade laid important groundwork for understanding polymetallic REE occurrences and integrating REE into broader critical metals frameworks.

The 2005–2014 period marked a turning point driven by geopolitical pressures, particularly the 2010 Chinese export quota crisis. This decade witnessed a surge in REE publications, aligning with heightened global concern over supply security. Geologically, this period emphasized three key trends: expanded mapping and extraction of ion-adsorption clays in South China and parts of Africa [

26,

56], reevaluation of African carbonatite systems such as Kangankunde (Malawi) and Mabounié (Gabon) [

1], and growing interest in the REE potential of deeply weathered granitic systems. Bibliometric overlays from this decade show a burst of keywords such as “critical metals,” “rare earth supply,” and “heavy REE,” reflecting a sharp policy-driven redirection of REE research.

In the most recent decade (2015–2024), the REE research frontier has expanded significantly into unconventional and sustainable sources. Notably, deep-sea muds in the Japanese exclusive economic zone (EEZ) have been identified as promising sources of Y, Tb, and other heavy REE [

55]. At the same time, coal- and black shale-hosted REE, especially from fly ash and associated by-products, have gained increasing attention in the United States, China, and Kazakhstan [

10,

22,

23]. Alkaline complexes such as Norra Kärr (Sweden) and Kipawa (Canada) have also emerged as exploration targets for REE hosted in eudialyte, britholite, and other accessory minerals [

8]. Sedimentary phosphorites, with global reserves of about 69 billion metric tons and average ∑REE contents of 0.046 wt%, are of growing interest as unconventional REE resources, particularly in North African countries such as Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco, where extensive deposits offer both phosphate production and significant REE potential [

28,

54]. Thematic bibliometric clusters from this era are characterized by “urban mining”, “sedimentary phosphorites”, “circular economy”, “seafloor sediments”, and “coal ash”, confirming a strong interdisciplinary shift linking geoscience with sustainability and materials engineering.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate how REE research has transitioned from a narrow focus on high-grade deposits to a diverse array of geological and anthropogenic sources. Each decade reflects a new layer of scientific inquiry, technological innovation, or strategic urgency. Bibliometric co-occurrence networks and citation bursts mirror this transition, confirming that global research attention closely follows economic trends, resource scarcity, and technological innovation.

From a resource development perspective, the implications are clear: future REE supply will increasingly depend on unconventional deposits (e.g., ion-adsorption clays, marine sediments, and coal ash), the integration of secondary sources (e.g., urban mining and recycling), and the advancement of processing technologies for low-grade ores. These trends underscore the need for continued interdisciplinary collaboration in REE research—spanning geology, metallurgy, materials science, and environmental engineering—to secure long-term, sustainable access to these critical elements.

3.8. Five Decades of REE Research Process Evolution: From Analytical Methods to Green Extraction

Across five decades of publications, REE research demonstrates a clear evolution in analytical techniques, marked by significant gains in precision and capability. In

Table 10, the development of REE research from 1975 to 2024 reflects continuous analytical innovation, moving from descriptive geochemistry to highly integrated, application-driven science. Over five decades, methodological advances have enabled deeper understanding of REE behavior in natural systems, improved resource exploration, and supported high-tech and sustainable extraction technologies. This progression aligns with the temporal patterns shown by the TELM and the interdisciplinary growth captured by CDPI.

1975–1984 (Foundational Era)—Research primarily employed optical microscopy, X-ray diffraction (XRD), and wet chemical analysis to characterize REE in rocks and sediments [

57].

1985–1994 (Instrumental Modernization)—Adoption of inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and electron microprobe analysis (EMPA) enabled precise trace element studies and mineral-scale geochemistry [

43].

1995–2004 (High-Resolution Geochemistry)—Laser ablation ICP-MS (LA-ICP-MS), TIMS, and synchrotron X-ray spectroscopy allowed isotopic studies and detailed partitioning in accessory minerals [

58].

2005–2014 (Integration and Multidisciplinarity)—Emergence of multi-collector ICP-MS, atom probe tomography (APT), and computational modeling supported geoscience–materials linkages and ore-to-material workflows [

59].

2015–2024 (Sustainability and Application-Driven Era)—Advanced in situ microanalytical platforms, nano-scale characterization, and AI-assisted modeling drive innovation in recycling, environmental geochemistry, and high-tech applications [

60].

The continuous advancement of analytical technologies in REE research has significantly enhanced precision, fostered interdisciplinary collaboration, accelerated discovery, supported sustainable extraction, and strengthened strategic resource management to meet growing technological and environmental demands.

Table 10.

Five decades of technological development in REE investigations (1975–2024).

Table 10.

Five decades of technological development in REE investigations (1975–2024).

| Period | Analytical Focus | Key Methods/Technologies | Representative Contributions |

|---|

| 1975–1984 | Fundamental mineralogy and geochemistry | XRD, optical microscopy, wet chemical assays | e.g., [57] |

| 1985–1994 | Trace element geochemistry | ICP-MS, EMPA | e.g., [43,59] |

| 1995–2004 | High-resolution isotopic studies | LA-ICP-MS, TIMS, synchrotron X-ray spectroscopy | e.g., [58,60] |

| 2005–2014 | Integrated geoscience and materials research | MC-ICP-MS, SIMS, APT, computational modeling | e.g., [27,29] |

| 2015–2024 | Sustainable and application-driven research | In situ microanalysis, nano-APT, AI-assisted analytics | e.g., [33,61,62] |

The industrial value of environmentally friendly extraction technologies for REE has grown substantially over the last five decades, driven by increasing demand for critical raw materials, rising environmental regulations, and the need to minimize the ecological footprint of mining activities. Conventional REE extraction methods, which often rely on strong acids, high-temperature processing, and large-scale tailings generation, have raised significant environmental and social concerns [

63,

64,

65]. As a result, the industry is transitioning toward sustainable practices that enable efficient recovery of REE from both primary deposits and secondary sources, including mine tailings and industrial residues.

Table 11 presents the five-decade progression (1975–2024) of environmentally friendly REE extraction technologies, summarized in 10-year intervals. The evolution reflects a shift from conventional acid leaching and solvent extraction in the 1970s and 1980s toward bioleaching, membrane separation, ionic liquids, and ultimately AI-optimized, nano-enabled, and hybrid biohydrometallurgy techniques in recent years. The early decades were characterized by high waste generation and minimal environmental consideration, while the 1995–2014 period marked the introduction of transitional green technologies, emphasizing selective recovery and reduced chemical usage. By 2015–2024, the field reached a mature stage of sustainability, incorporating circular economy principles and strategic tailings recovery, demonstrating the growing industrial and environmental significance of eco-friendly REE extraction [

63,

66].

Environmentally friendly REE extraction technologies provide four major industrial advantages. First, resource maximization and circular economy benefits arise from recovering REE from low-grade ores and tailings using bioleaching, ionic liquids, and selective adsorption materials, which enhance resource efficiency and reduce waste [

66,

67]. Second, reduced environmental impact is achieved through techniques such as phytomining, membrane separation, and low-acid leaching, which limit chemical use and tailings toxicity, aligning with stricter global regulations [

3,

63,

68]. Third, these methods improve cost and energy efficiency by reducing reliance on energy-intensive roasting and high-volume solvent extraction; for instance, biohydrometallurgy and electrochemical processes can recover REE with lower energy and reagent consumption [

64,

69,

70]. Finally, strategic supply security is enhanced through secondary recovery from tailings, providing domestic REE sources and reducing vulnerability to geopolitical supply risks, as highlighted after China’s 2010 export restrictions [

13].

From an industrial perspective, these eco-friendly technologies not only ensure environmental compliance but also transform legacy mine waste into economic assets. Pilot projects in China, Australia, and the United States demonstrate that integrating green REE recovery into existing mining operations can generate new revenue streams while reducing environmental impacts [

61,

66,

71]. Recent techno-economic and lifecycle assessment (TEA/LCA) studies on REE [

62] provide insights into environmentally sustainable extraction, processing, and recovery pathways. These studies highlight the potential environmental benefits and trade-offs of different REE technologies, but also identify which process classes are emerging, where environmental and economic burdens are concentrated, and how these findings correlate with bibliometric trends. Incorporating this evidence strengthens the evaluation of green innovation and circularity in the field by linking observed research trends to real-world TEA/LCA outcomes. Looking forward, the combination of AI-driven process optimization with advanced sustainable extraction methods is expected to accelerate commercialization and strengthen the global REE supply chain in a sustainable manner.

Considering the time evolution and research trends, it can be noted that over the last five years, REE-related research has grown rapidly, reflecting shifting technological, environmental, and policy priorities. The most pronounced expansion is observed in REE recycling and recovery, particularly from end-of-life NdFeB magnets and electronic waste, alongside the increased adoption of greener hydrometallurgical and bioleaching methods. Research on unconventional and secondary resources has also intensified, including bauxite and bauxite residue (red mud), phosphorites, coal and coal by-products, and various mining and processing wastes, which are increasingly considered viable alternative REE sources. In parallel, the current research landscape is increasingly shaped by AI- and data-driven approaches, integrating natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning (ML) with geochemistry, materials science, and process engineering. Emerging studies illustrate applications of NLP and ML for mineral prospectivity mapping, process optimization, recycling efficiency, and supply chain analysis, often using geochemical datasets to identify promising REE deposits—including unconventional resources such as bauxite residues and phosphorites. AI also supports optimization of leaching and separation processes, prediction of recovery from end-of-life magnets and electronic waste, and forecasting of critical REE demand. Despite these advances, applications remain emerging and are limited by data quality and model interpretability, highlighting the need for further development and closer integration with domain knowledge. Overall, focusing on the last five years better captures these fast-evolving, geochemistry-intensive and AI-driven research themes, emphasizing new directions that are less visible in longer-term analyses.

3.9. Sectoral Process Impacts of REE: Geoscience, Materials Science, and Their Industrial Applications

REE research over the past five decades has evolved from a geoscience-centered field into a strategic industrial domain, driving green technologies, advanced materials, and sustainable resource development [

63,

64]. Analysis of Web of Science data (1975–2024), supported by VOSviewer visualizations and the CDPI/TELM frameworks, highlights the sectoral interplay between geoscience, materials science, and industry.

Geoscience provides the foundation for REE exploration and environmental assessment. Key disciplines—geochemistry (17.4%), mineralogy (10.9%), and geology (6.7%)—enable ore characterization, predictive exploration, and metallogenic mapping, which are crucial for identifying strategic deposits and mitigating environmental risks [

43,

64]. TELM trends indicate that research surges align with commodity price peaks and geopolitical events, emphasizing the economic sensitivity of REE geoscience.

Materials science is the fastest-growing sector, now comprising 15.8% of WoS publications, with applications in magnets, batteries, phosphors, and catalysts. CDPI analysis reveals strong interdisciplinary links with physical chemistry and applied physics, reflecting REE’ role in clean energy technologies such as wind turbines and EV motors [

63,

66]. Nanotechnology and computational modeling increasingly enhance material performance and energy efficiency.

Industrial applications demonstrate REE’ centrality to the green and digital economy, including renewables, defense, and electronics. The TELM framework shows that investments are increasingly aligned with supply chain security and ESG goals. Modern focus on eco-friendly extraction—bioleaching, ionic liquids, and tailings recovery—reflects the shift toward circular economy principles [

63,

66,

72]. Pilot projects in China, the U.S., and Australia prove that industrial–academic collaborations can turn mine waste into economic assets while lowering environmental impact [

64,

66,

72].

Future REE research and industrial strategies hinge on interdisciplinary integration, analytical innovation, and sustainable processing. Coordinated efforts across academia, government, and industry will be vital to secure supply chains and meet ESG-compliant demand for critical materials.