Kinetic Study of Color, Texture and Exergy Analysis of Halloumi Cheese During Deep-Fat Frying Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Manufacture of Halloumi Cheese

2.2. Deep-Fat Frying of Halloumi Cheese

2.3. Measurements of Color Values

2.4. Texture Profile Analysis (TPA)

2.5. Kinetic Modeling

2.6. Exergy Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis and Model Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

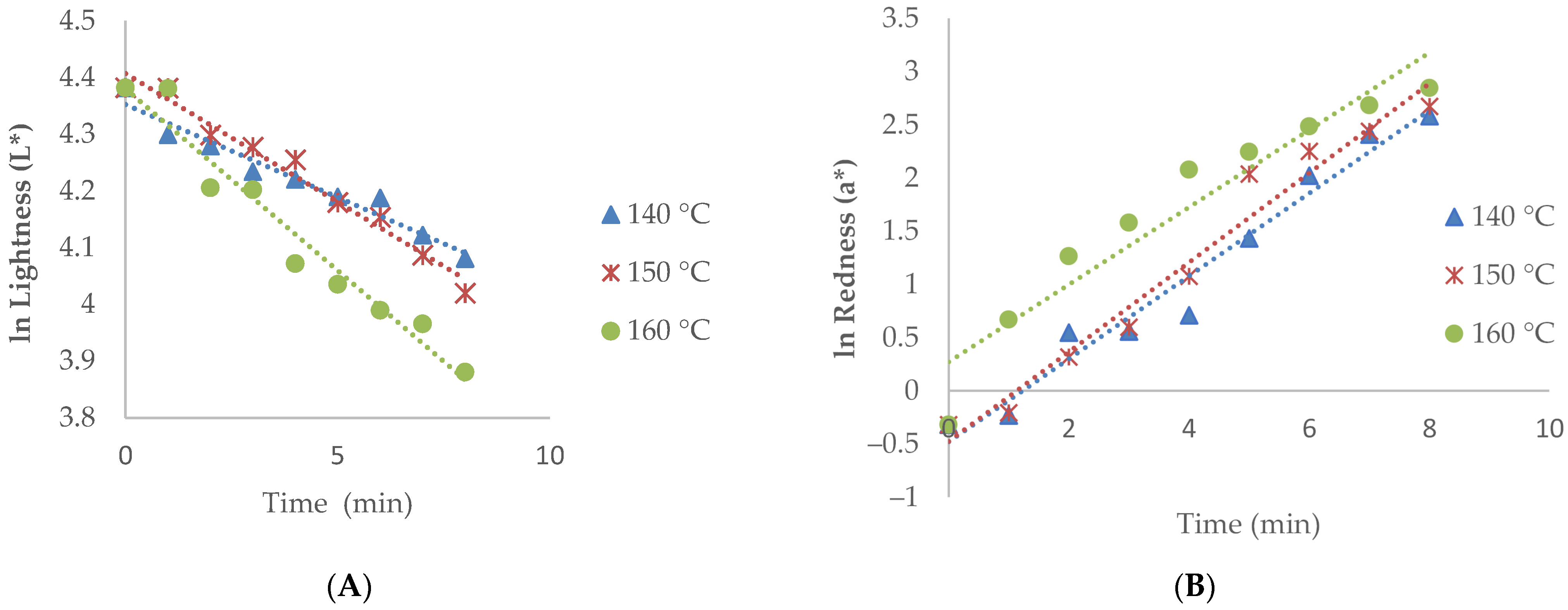

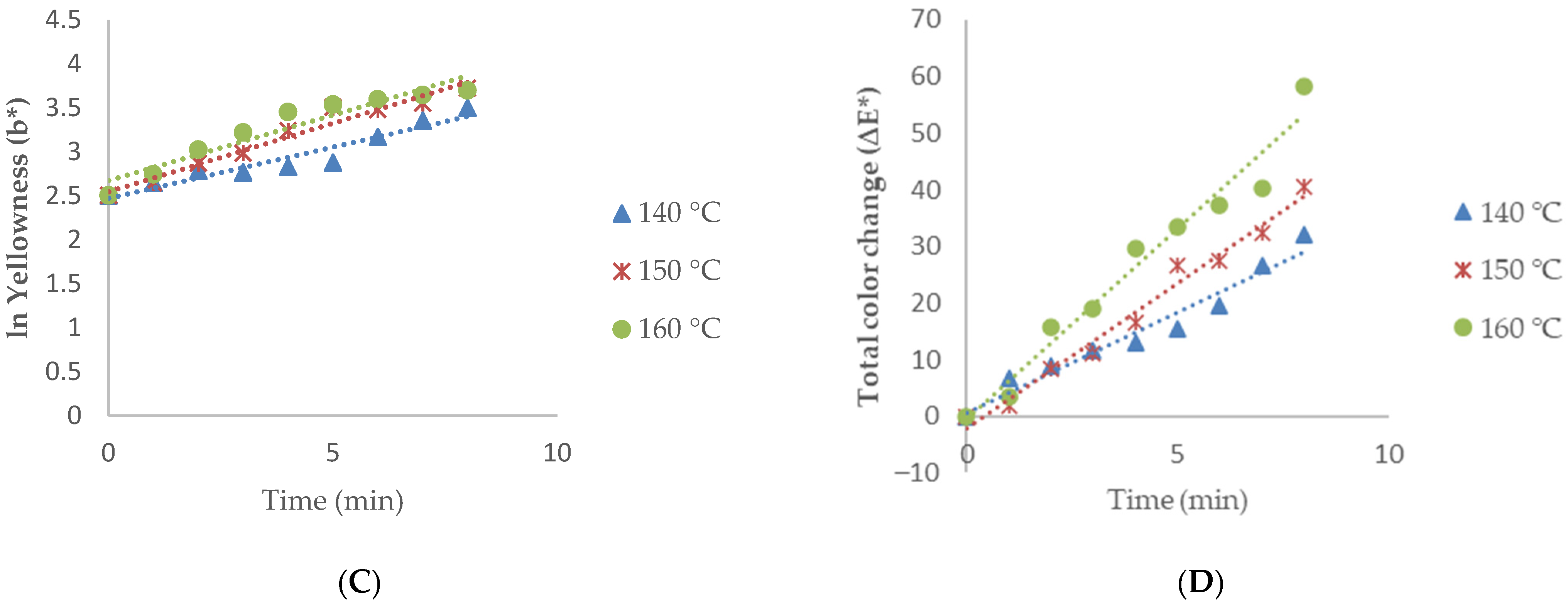

3.1. Kinetics of Color

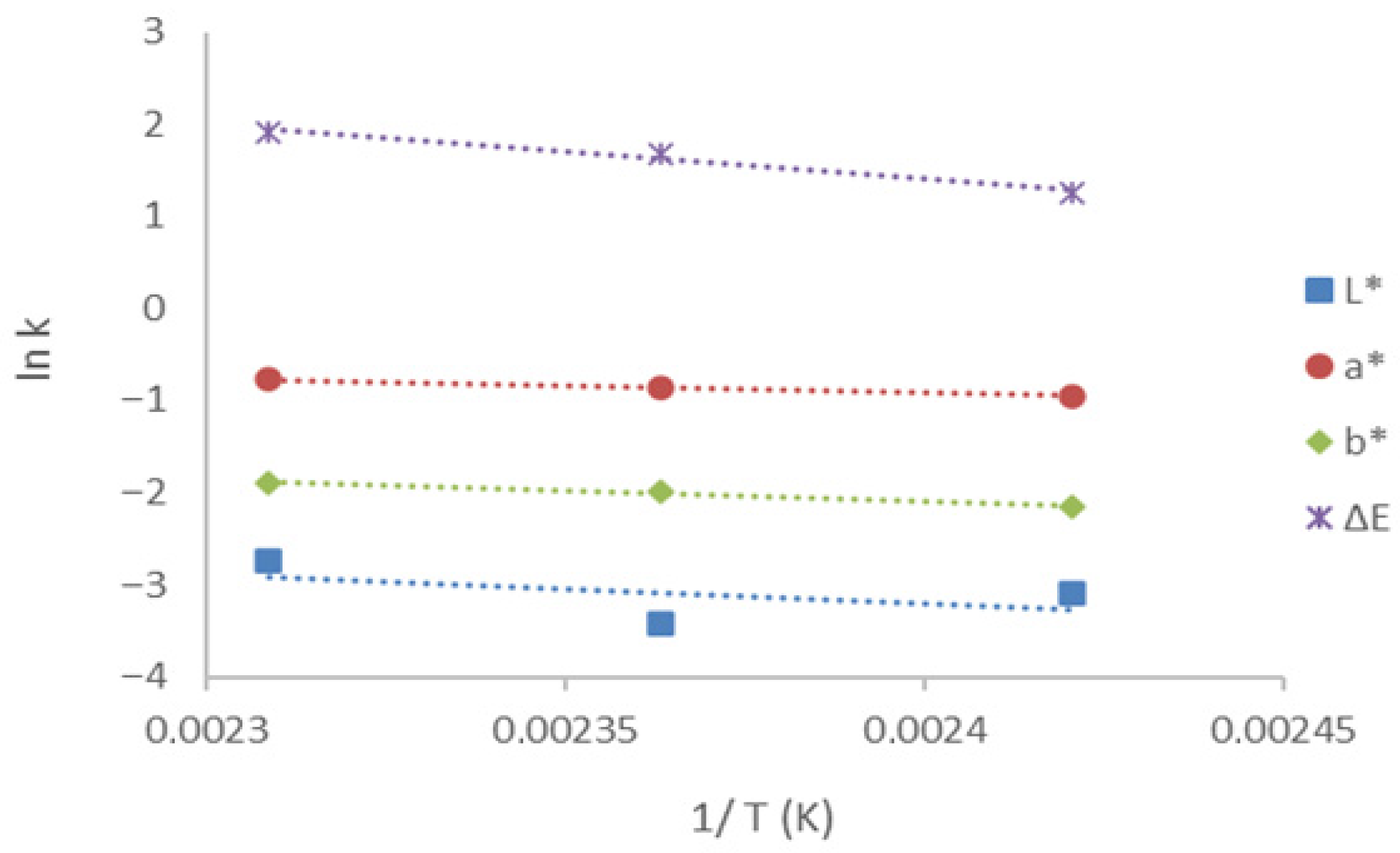

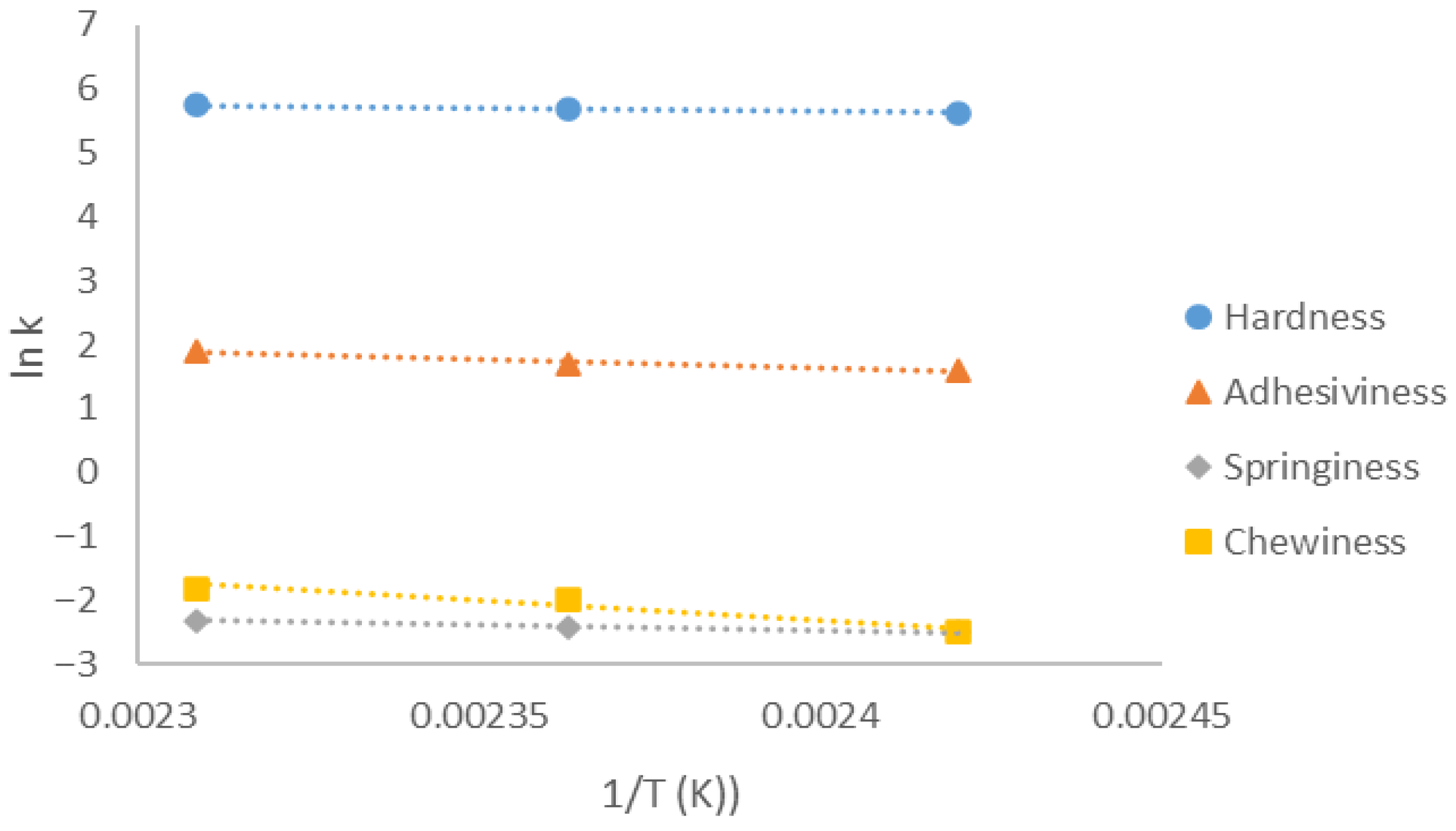

3.2. Kinetics of Texture

3.3. Exergy Analysis Results

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| T | Frying Temperature (°C) |

| t | Frying Time (min) |

| Core T | Core Temperature of Cheese (°C) |

| Ψ | Exergy (kJ) |

| Ψ_in | Input Exergy (kJ) |

| Ψ_cheese | Product (Cheese) Exergy (kJ) |

| Ψ_vap | Evaporation Exergy (kJ) |

| η_cheese | Exergy Efficiency without Evaporation (%) |

| Qt | Total Heat Input (kJ) |

| hfg | Latent Heat of Vaporization (kJ/kg) |

| m | Mass (kg) |

| min | minute |

| k | Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) |

| ρ | Density (kg/m3) |

| cp | Specific Heat Capacity (kJ/kg·K) |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| L* | Lightness (0 = black, 100 = white) |

| a* | Redness (+a)/Greenness (−a) |

| b* | Yellowness (+b)/Blueness (−b) |

| ΔE | Total Color Difference |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

References

- Papademas, P.; Robinson, R.K. The sensory characteristics of different types of halloumi cheese as perceived by tasters of different ages. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2001, 54, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminarides, S.; Rogoti, E.; Mallatou, H. Comparison of the characteristics of halloumi cheese made from ovine milk, caprine milk or mixtures of these milks. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2000, 53, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüş, S. Branding within the scope of destination marketing: Hallum example. ASES Int. J. Cult. Art Lit. 2024, 3, 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, R.; Robinson, R.K.; Wilbey, R.A. Cheesemaking Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Elgaml, N.B.; Moussa, M.A.; Saleh, A.E. Impact of adding Moringa oleifera on the quality and properties of halloumi cheese. Egypt. J. Agric. Res. 2018, 96, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiony, M.; Hassabo, R. Composition and quality of low-fat halloumi cheese made using modified starch as a fat replacer. Starch-Stärke 2022, 74, 2100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzamaloukas, O.; Neofytou, M.C.; Simitzis, P.E.; Miltiadou, D. Effect of farming system (organic vs. conventional) and season on composition and fatty acid profile of bovine, caprine and ovine milk and retail Halloumi cheese produced in Cyprus. Foods 2021, 10, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lteif, L.; Olabi, A.; Baghdadi, O.K.; Toufeili, I. The characterization of the physicochemical and sensory properties of full-fat, reduced-fat, and low-fat ovine and bovine Halloumi. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 4135–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamage, A.N.; Jeyasiri, R.; Hettiarachchi, D.D.; Munasinghe, S.S.; Dilrukshi, N. Physicochemical, microbiological, and sensory characterization of halloumi cheese fortified with garlic (Allium sativum) and pepper (Piper nigrum). Eng. Proc. 2023, 37, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Karimy, M.F.; Febrisiantosa, A.; Sefrienda, A.R.; Setiyawan, A.I.; Pratiwi, D.; Khasanah, Y.; Wahyono, T. The impact of adding different levels of spirulina on the characteristics of halloumi cheese. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2024, 38, 101050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordin, K.; Tomihe Kunitake, M.; Kazue Aracava, K.; Silvia Favaro Trindade, C. Changes in food caused by deep fat frying—A review. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2013, 63, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asokapandian, S.; Swamy, G.J.; Hajjul, H. Deep fat frying of foods: A critical review on process and product parameters. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2020, 60, 3400–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, L.; Kumar, M.; Kaushik, D.; Kaur, J.; Kumar, A.; Oz, F.; Oz, E. A review on the frying process: Methods, models and their mechanism and application in the food industry. Food Res. Int. 2023, 172, 113176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erim Köse, Y.; Doğan, İ.S. Determination of simultaneous heat and mass transfer parameters of tulumba dessert during deep-fat frying. J. Food Process Preserv. 2017, 41, e13082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, B.; Tang, J.; Kong, F.; Mitcham, E.J.; Wang, S. Kinetics of food quality changes during thermal processing: A review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2014, 8, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šeruga, B.; Budžaki, S.; Ugarčić-Hardi, Ž. Individual heat transfer modes during baking of “mlinci” dough. Agric. Conspect. Sci. 2007, 72, 257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.J.; Singh, R.R.B.; Patel, A.A.; Patil, G.R. Kinetics of colour and texture changes in Gulabjamun balls during deep-fat frying. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 39, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Ruiz, J.F.; Sosa-Morales, M.E. Evaluation of physical properties of dough of donuts during deep-fat frying at different temperatures. Int. J. Food Prop. 2003, 6, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, O.D.; Mittal, G.S. Kinetics of tofu color changes during deep-fat frying. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2003, 36, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourian, F.; Ramaswamy, H.S. Kinetics of quality change during cooking and frying of potatoes: Part II. Color. J. Food Process Eng. 2003, 26, 395–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, I.H.; Dash, K.K. Textural, color kinetics, and heat and mass transfer modeling during deep fat frying of Chhena Jhili. J. Food Process Preserv. 2017, 41, e12828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitrac, O.; Trystram, G.; Raoult-Wack, A.L. Deep-fat frying of food: Heat and mass transfer, transformations and reactions inside the frying material. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2000, 102, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genç, Ş.; Hepbaşlı, A. Performance assessment of a potato crisp frying process. Drying Technol. 2015, 33, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papademas, P.; Robinson, R.K. Halloumi cheese: The product and its characteristics. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 1998, 51, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahyaoğlu, T.; Kaya, S.; Kaya, A. Effects of fat reduction and curd dipping temperature on viscoelasticity, texture and appearance of Gaziantep cheese. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2005, 11, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zisopoulos, F.K.; Rossier-Miranda, F.J.; Van der Goot, A.J.; Boom, R.M. The use of exergetic indicators in the food industry—A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bühler, F.; Nguyen, T.V.; Jensen, J.K.; Holm, F.M.; Elmegaard, B. Energy, exergy and advanced exergy analysis of a milk processing factory. Energy 2018, 162, 576–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedreschi, F.; Kaack, K.; Granby, K. Acrylamide content and color development in fried potato strips. Food Res. Int. 2006, 39, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduh, S.B.M.; Leong, S.Y.; Zhao, C.; Baldwin, S.; Burritt, D.J.; Agyei, D.; Oey, I. Kinetics of colour development during frying of potato pre-treated with pulsed electric fields and blanching: Effect of cultivar. Foods 2021, 10, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lin, L.; Zhang, P. Color development kinetics of Maillard reactions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 3495–3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, E.K.; Idowu, M.A.; Sobukola, O.P.; Adeyeye, S.A.O.; Akinsola, A.O. Frying of food: A critical review. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2018, 16, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Nema, P.K.; Kumar, S.; Chandra, A. Kinetics of change in quality parameters of khaja during deep-fat frying. J. Food Process Preserv. 2022, 46, e16265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Rahman, N.A.; Abdul Razak, S.Z.; Lokmanalhakim, L.A.; Taip, F.S.; Mustapa Kamal, S.M. Response surface optimization for hot air-frying technique and its effects on the quality of sweet potato snack. J. Food Process Eng. 2017, 40, e12507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.B.; Shamsudin, R.; Mohammed, A.P.; Abdul Rahman, N.A. Colour changes during deep-frying of sesame cracker’s dough balls. In Proceedings of the III International Conference on Agricultural and Food Engineering, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 23–25 August 2016; Volume 1152, pp. 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, P.; Mondal, I.H.; Dash, K.K.; Geetika; Suthar, T.; Ramzan, K.; Béla, K. Deep fat frying characteristics of Malpoa: Kinetics, heat, and mass transfer modeling. Processes 2024, 12, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayaloglu, A.A. Cheese varieties of Cyprus. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2009, 62, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, F.J.; Jiménez-Pérez, S. Free radical scavenging capacity of Maillard reaction products. Food Chem. 2004, 90, 695–701. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, S.I.F.S.; Jongen, W.M.F.; van Boekel, M.A.J.S. A review of Maillard reaction in food and implications to kinetic modelling. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2001, 11, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buera, M.P.; Schebor, C.; Elizalde, B.E. Effects of carbohydrate–protein interactions on Maillard browning kinetics in dehydrated food systems. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2003, 9, 143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahi Moghaddam, M.R.; Rafe, A.; Taghizadeh, M. Kinetics of color and physical attributes of cookie during deep-fat frying by image processing techniques. J. Food Process Preserv. 2015, 39, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, K.D.; Petridis, D.; Raphaelides, S.; Omar, Z.B.; Kesteloot, R. Texture assessment of French cheeses. J. Food Sci. 2000, 65, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamrui, K.; Dutta, S.; Dave, K. Effect of frying, freezing and rehydration on texture profile of Paneer and relationships between its instrumental and sensory textural attributes. Milchwiss.-Milk Sci. Int. 2004, 59, 640–645. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P.; Zambrano, A.; Zamora, A.; Castillo, M. Thermal denaturation of milk whey proteins: A comprehensive review on rapid quantification methods being studied, developed and implemented. Dairy 2022, 3, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarapata, J.; Szymańska, E.; van der Meulen, L.; Miltenburg, J.; Huppertz, T. Moisture Loss from Cheese During Baking: Influence of Cheese Type, Cheese Mass, and Temperature. Foods 2025, 14, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erim Köse, Y. Kinetic Modeling of Heat and Mass Transfer During Deep Fat Frying of Churro. Bilge Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2025, 6, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rywotycki, R. A model of heat energy consumption during frying of food. J. Food Eng. 2003, 59, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | T (°C) | Model | k (min−1) | R2 | RMSE | Ea (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | 140 150 160 | First-order kinetic | 0.0453 ± 0.21 b 0.0237 ± 0.04 a 0.0641 ± 1.01 c | 0.975 0.9573 0.9567 | 0.035 0.033 0.033 | 25.235 ± 0.59 c |

| a* | 140 150 160 | First-order kinetic | 0.3889 ± 0.35 a 0.4220 ± 0.05 b 0.4631 ± 0.21 c | 0.966 0.967 0.914 | 0.178 0.189 0.186 | 12.976 ± 0.44 a |

| b* | 140 150 160 | First-order kinetic | 0.1163 ± 0.02 a 0.1358 ± 0.42 b 0.1491 ± 0.11 c | 0.919 0.963 0.911 | 0.084 0.073 0.113 | 18.516 ± 0.28 b |

| ∆E | 140 150 160 | Zero-order kinetic | 3.4849 ± 1.22 a 5.3454 ± 1.20 b 6.7192 ± 0.82 c | 0.934 0.982 0.950 | 1.005 1.007 0.993 | 48.950 ± 0.46 d |

| Parameter | T (°C) | Model | k (min−1) | R2 | RMSE | Ea (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardness | 140 150 160 | Zero-order kinetic | 279.24 ± 0.59 a 294.85 ± 0.42 b 315.57 ± 0.29 c | 0.957 0.996 0.986 | 0.143 0.411 0.880 | 9.089 ± 0.11 a |

| Adhesiveness | 140 150 160 | Zero-order kinetic | 4.957 ± 0.22 a 5.467 ± 0.21 b 6.619 ± 0.22 c | 0.9865 0.9917 0.9762 | 0.151 0.122 0.253 | 21.438 ± 0.08 c |

| Springiness | 140 150 160 | First-order kinetic | −0.082 ± 0.011 c −0.090 ± 0.010 b −0.098 ± 0.011 a | 0.999 0.998 0.995 | 0.005 0.007 0.016 | 12.761 ± 0.08 b |

| Chewiness | 140 150 160 | First-order kinetic | −0.083 ± 0.22 c −0.138 ± 0.19 b −0.164 ± 0.018 a | 0.895 0.988 0.976 | 0.083 0.052 0.043 | 50.857 ± 0.41 d |

| T (°C) | Time (min) | Core T (°C) | Product Exergy (kJ) | Evaporation Exergy (kJ) | Exergy Efficiency Without Evap (%) | Exergy Efficiency with Evap (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 140 | 2 | 41.2 | 0.0109 | 0.0492 | 5.62 a | 31.08 a |

| 140 | 4 | 55.1 | 0.0360 | 0.0984 | 9.80 b | 36.58 c |

| 140 | 6 | 67.0 | 0.0679 | 0.1477 | 12.90 e | 40.97 e |

| 140 | 8 | 77.3 | 0.1016 | 0.1969 | 15.15 g | 44.52 f |

| 150 | 2 | 45.4 | 0.0169 | 0.0789 | 5.97 a | 33.53 b |

| 150 | 4 | 62.5 | 0.1039 | 0.1577 | 10.07 c | 39.20 d |

| 150 | 6 | 76.8 | 0.1219 | 0.2369 | 12.83 e | 43.52 f |

| 150 | 8 | 88.8 | 0.1421 | 0.3145 | 14.63 f | 46.83 h |

| 160 | 2 | 46.8 | 0.0192 | 0.0984 | 5.57 a | 33.99 b |

| 160 | 4 | 65.1 | 0.0610 | 0.1969 | 9.32 b | 39.30 b |

| 160 | 6 | 80.4 | 0.1105 | 0.2953 | 11.78 d | 43.29 f |

| 160 | 8 | 93.3 | 0.1592 | 0.3938 | 13.33 f | 46.31 g |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Erim Köse, Y. Kinetic Study of Color, Texture and Exergy Analysis of Halloumi Cheese During Deep-Fat Frying Process. Processes 2026, 14, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010039

Erim Köse Y. Kinetic Study of Color, Texture and Exergy Analysis of Halloumi Cheese During Deep-Fat Frying Process. Processes. 2026; 14(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleErim Köse, Yağmur. 2026. "Kinetic Study of Color, Texture and Exergy Analysis of Halloumi Cheese During Deep-Fat Frying Process" Processes 14, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010039

APA StyleErim Köse, Y. (2026). Kinetic Study of Color, Texture and Exergy Analysis of Halloumi Cheese During Deep-Fat Frying Process. Processes, 14(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010039