Green Synthesis of Silver Particles Using Pecan Nutshell Extract: Development and Antioxidant Characterization of Zein/Pectin Active Films

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

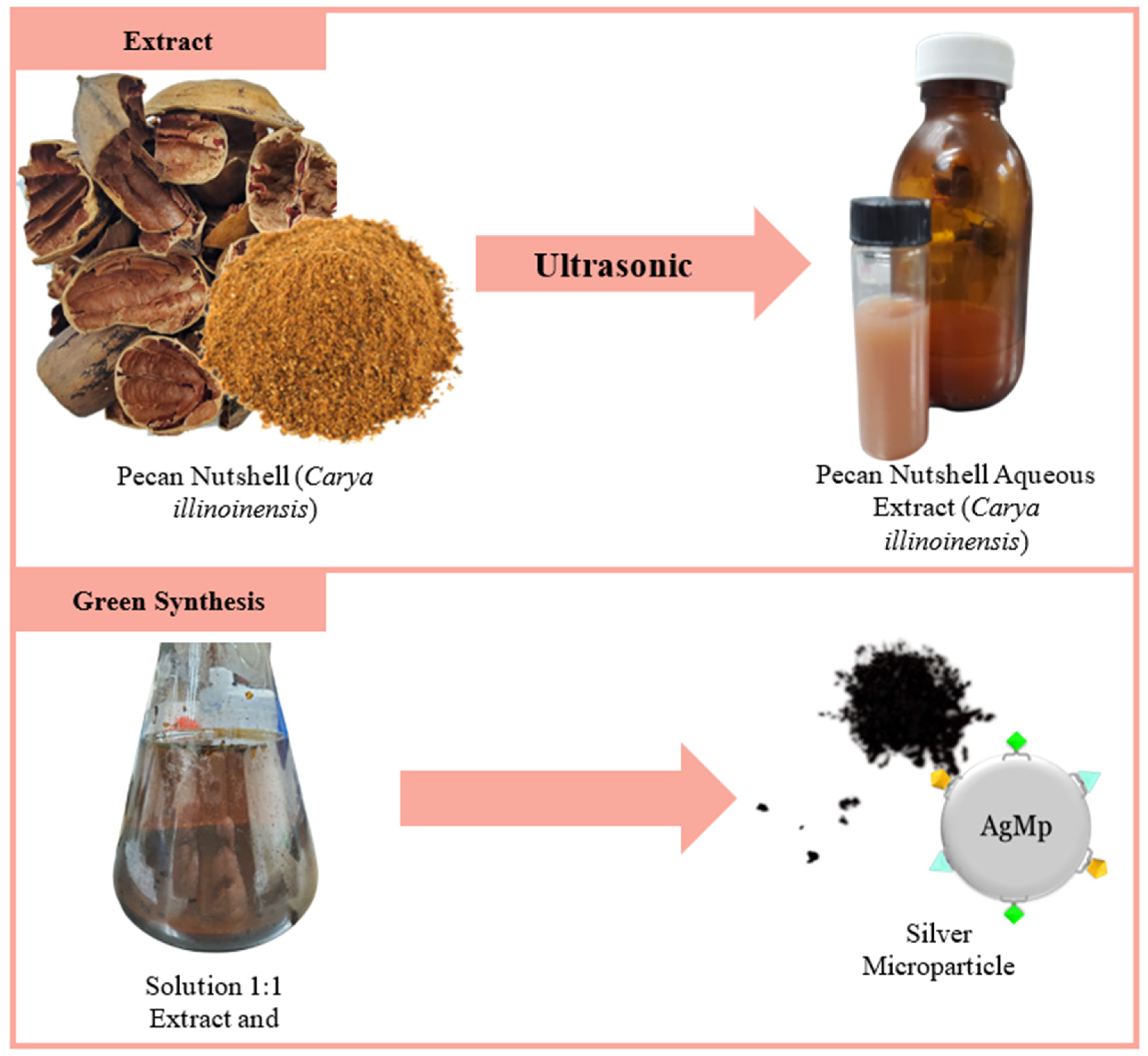

2.2. Green Synthesis of AgMp

2.2.1. Preparation of Aqueous Extract

2.2.2. Synthesis of AgMp

2.3. Characterization of AgMp

2.4. Determination of the Antioxidant Activity of AgMp

2.4.1. Quantification of Total Phenols

2.4.2. Quantification of Total Flavonoids

2.4.3. ABTS Radical Inhibition

2.4.4. DPPH Radical Inhibition

2.4.5. Ferric Reducing Capacity (FRAP)

2.5. Preparation of Zein/Pectin Film with AgMp

2.6. Characterization of Zein/Pectin Films with AgMp

2.6.1. Film Color

2.6.2. Film Thickness

2.6.3. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR)

2.6.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.6.5. Thermal Analysis by Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.7. Determination of the Antioxidant Activity of Zein/Pectin Films with AgMp

2.7.1. ABTS Radical Inhibition

2.7.2. DPPH Inhibition

2.7.3. Ferric Reducing Capacity (FRAP)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Green Synthesis of AgMp

3.2. Characterization of AgMp

3.2.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

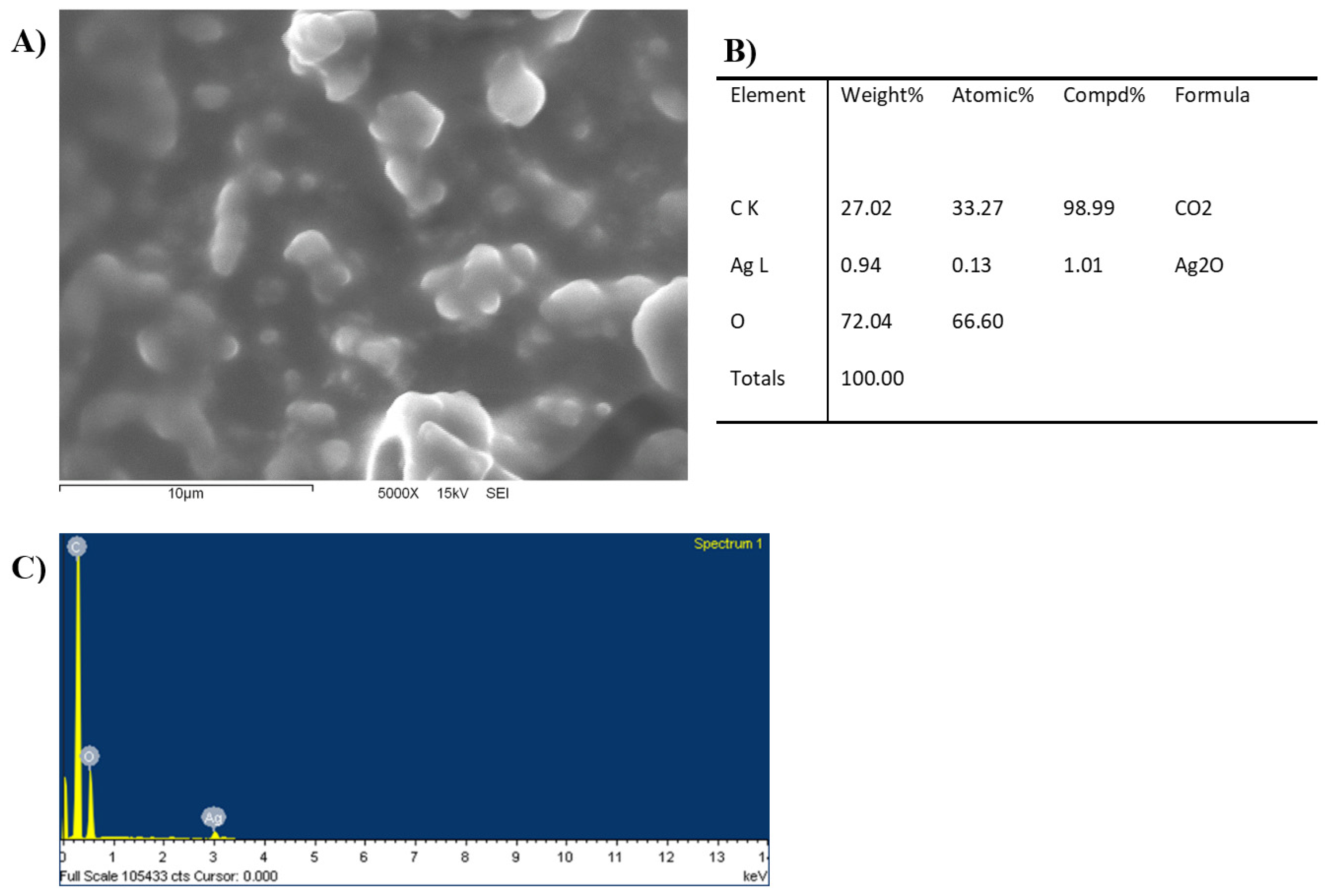

3.2.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

3.3. Determination of the Antioxidant Activity of AgMp

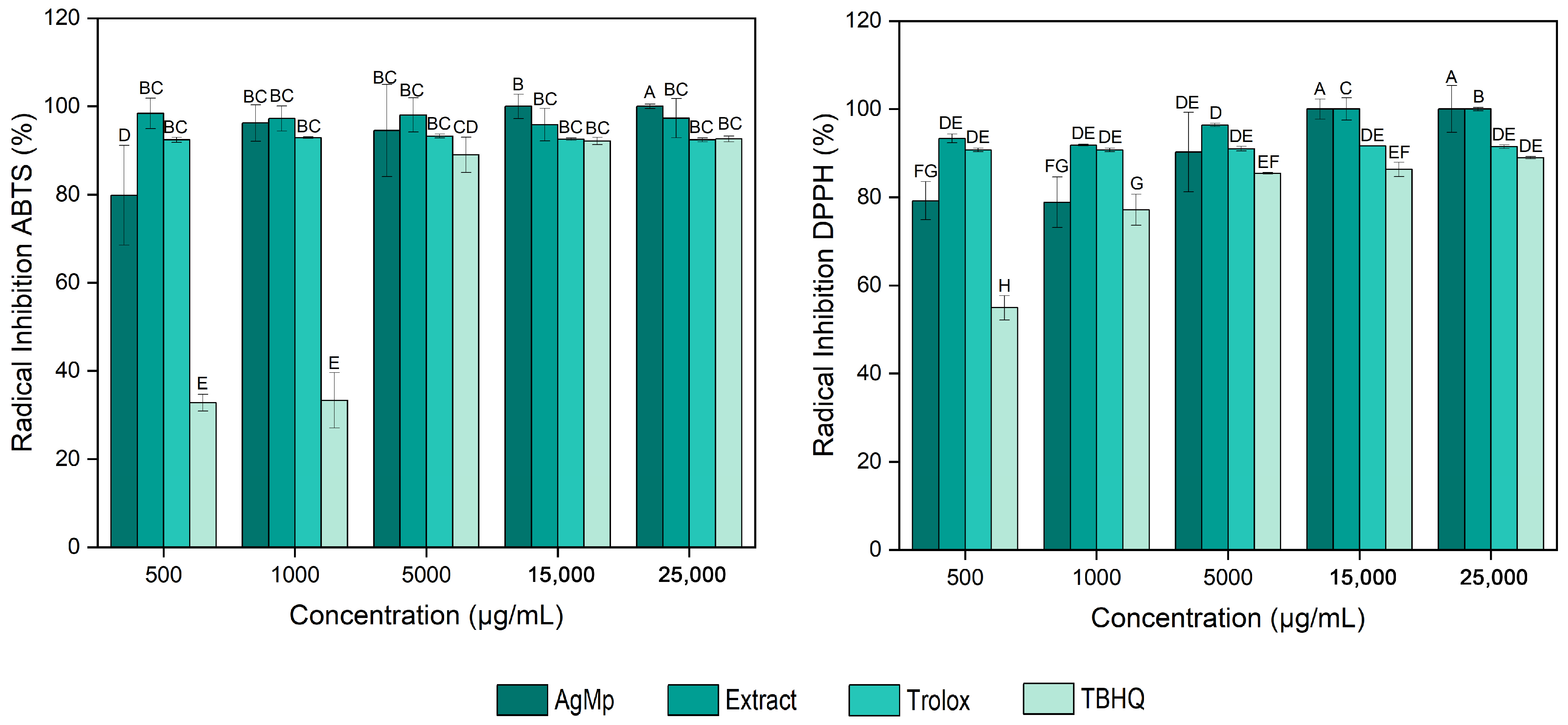

3.4. Preparation of Zein/Pectin Film with AgMp

3.5. Characterization of Zein/Pectin Films with AgMp

3.5.1. Film Color and Thickness

3.5.2. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR)

3.5.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

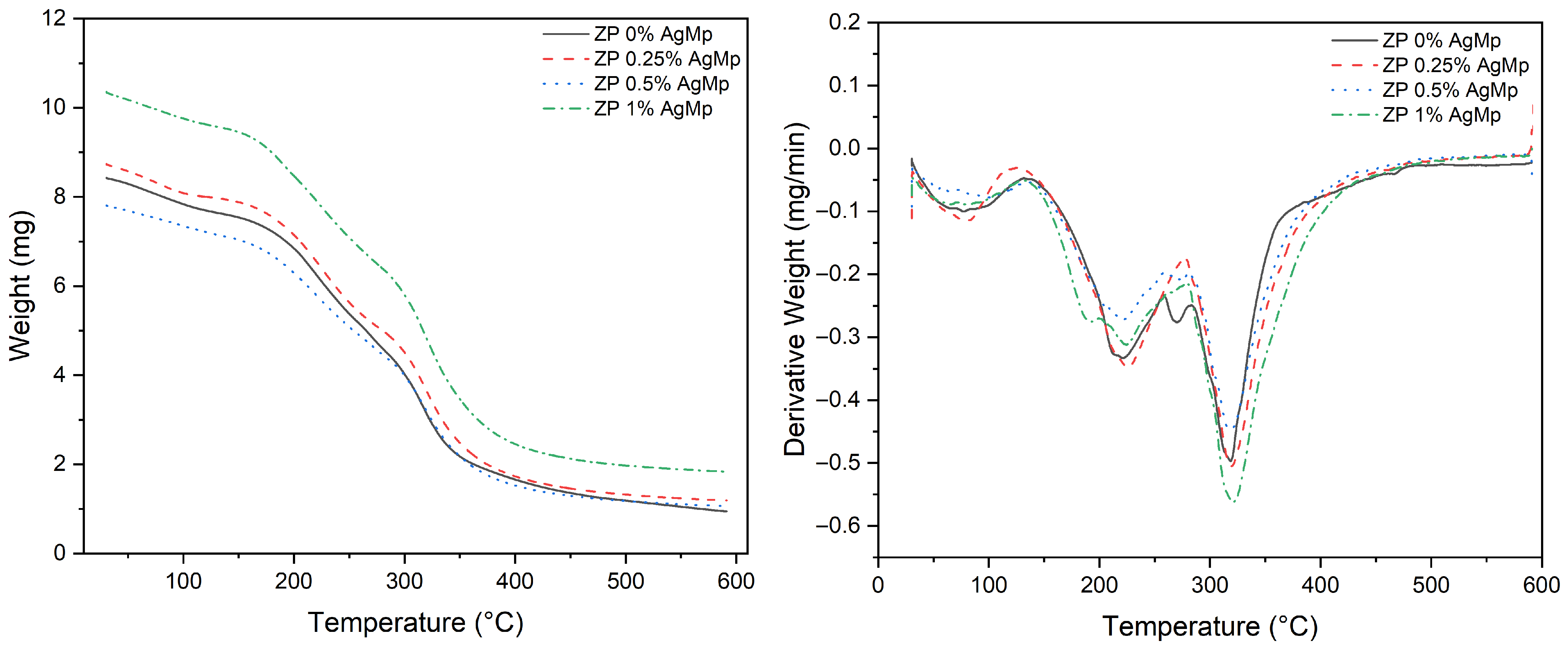

3.5.4. Thermal Analysis by Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

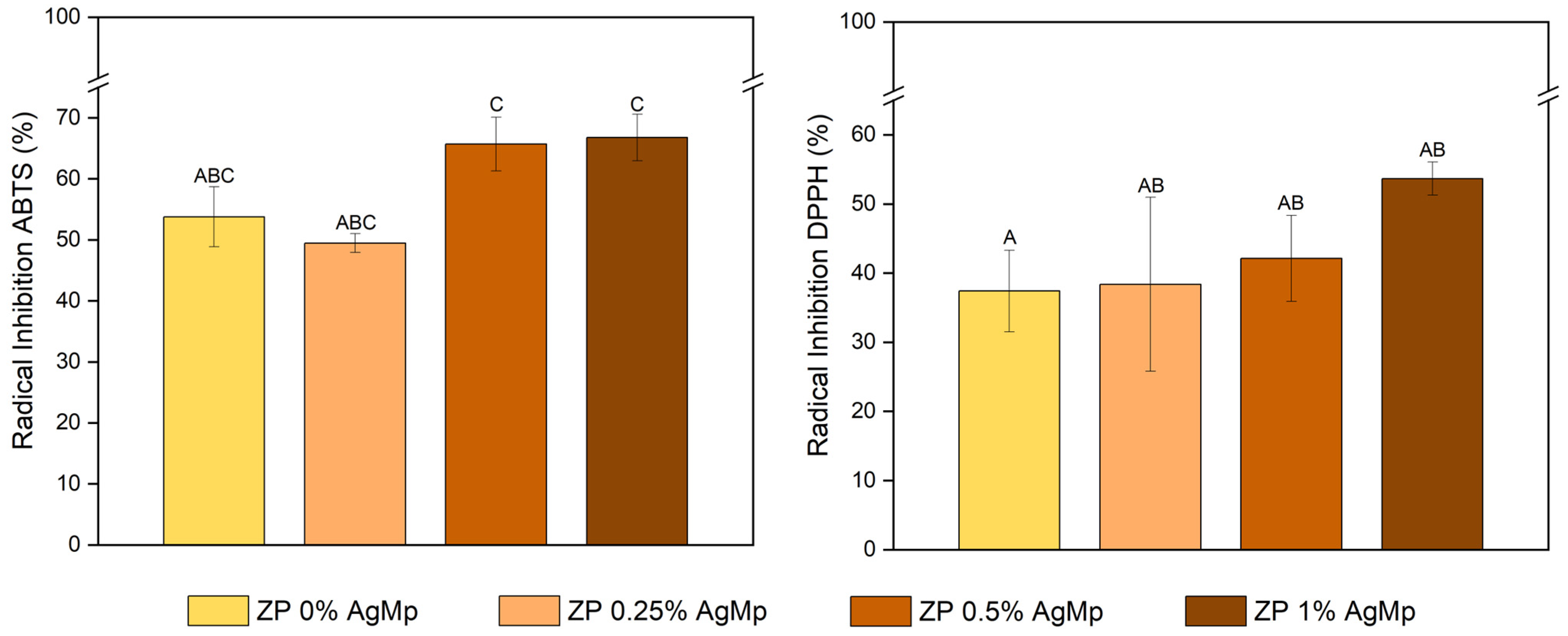

3.6. Determination of the Antioxidant Activity of Zein/Pectin Films with AgMp

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, K.; Wang, Y. Advances in Bio-Based Smart Food Packaging for Enhanced Food Safety. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 159, 104960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, M.C.; Leocádio, J.; Mendes, C.V.T.; Cardeira, M.; Fernández, N.; Matias, A.; Carvalho, M.G.V.S.; Braga, M.E.M. Biodegradable Film Production from Agroforestry and Fishery Residues with Active Compounds. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2021, 28, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheibani, S.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Qazanfarzadeh, Z.; Osadee Wijekoon, M.M.J.; Mohd Rozalli, N.H.; Mohammadi Nafchi, A. Sustainable Strategies for Using Natural Extracts in Smart Food Packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 267, 131537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sourav, C.; Sasidharan, A.; Mohan, C.O.; Sabu, S.; Sunooj, K.V. Prospects of Biodegradable Packaging in the Seafood Industry: A Review. Asian Fish. Sci. 2025, 38, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Jaiswal, A.K.; Jaiswal, S. A Critical Review of Consumer Perception and Environmental Impacts of Bioplastics in Sustainable Food Packaging. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozuna-Valencia, K.H.; Moreno-Vásquez, M.J.; Graciano-Verdugo, A.Z.; Rodríguez-Félix, F.; Robles-García, M.Á.; Barreras-Urbina, C.G.; Quintero-Reyes, I.E.; Cornejo-Ramírez, Y.I.; Tapia-Hernández, J.A. The Application of Organic and Inorganic Nanoparticles Incorporated in Edible Coatings and Their Effect on the Physicochemical and Microbiological Properties of Seafood. Processes 2024, 12, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouzakitis, C.K.; Sereti, V.; Matsakidou, A.; Kotsiou, K.; Biliaderis, C.G.; Lazaridou, A. Physicochemical Properties of Zein-Based Edible Films and Coatings for Extending Wheat Bread Shelf Life. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 132, 107856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z.; Ju, X.; Yuan, Y. A Review of Food Preservation Based on Zein: The Perspective from Application Types of Coating and Film. Food Chem. 2023, 424, 136403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, F.; Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Kang, M. Development and Characterization of Zein-Based Active Packaging Films Containing Catechin Loaded β-Cyclodextrin Metal-Organic Frameworks. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 31, 100810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, Z.; Xu, F.; Cheng, Y.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Wu, P. Enhancing the Performance of Konjac Glucomannan Films through Incorporating Zein–Pectin Nanoparticle-Stabilized Oregano Essential Oil Pickering Emulsions. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 124, 107222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Tong, C.; Wu, C.; Pang, J. Production and Characterization of Composite Films with Zein Nanoparticles Based on the Complexity of Continuous Film Matrix. LWT 2022, 161, 113396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaona-Sánchez, V.A.; Calderón-Domínguez, G.; Morales-Sánchez, E.; Moreno-Ruiz, L.A.; Terrés-Rojas, E.; Salgado-Cruz, M.d.l.P.; Escamilla-García, M.; Barrios-Francisco, R. Physicochemical and Superficial Characterization of a Bilayer Film of Zein and Pectin Obtained by Electrospraying. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 50045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Ge, X.; Zhou, L.; Wang, Y. Eugenol Embedded Zein and Poly(Lactic Acid) Film as Active Food Packaging: Formation, Characterization, and Antimicrobial Effects. Food Chem. 2022, 384, 132482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Jia, F.; Han, Y.; Meng, X.; Xiao, Y.; Bai, S. Development and Characterization of Zein Edible Films Incorporated with Catechin/β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex Nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 261, 117877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bueno, N.N.; Corradini, E.; de Souza, P.R.; Marques, V.D.S.; Radovanovic, E.; Muniz, E.C. Films Based on Mixtures of Zein, Chitosan, and PVA : Development with Perspectives for Food Packaging Application. Polym. Test. 2021, 101, 107279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.C.B.; Cunha, A.P.; da Silva, L.M.R.; Mattos, A.L.A.; de Brito, E.S.; de Souza Filho, M.d.S.M.; de Azeredo, H.M.C.; Ricardo, N.M.P.S. From Mango By-Product to Food Packaging: Pectin-Phenolic Antioxidant Films from Mango Peels. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 193, 1138–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivangi, S.; Dorairaj, D.; Negi, P.S.; Shetty, N.P. Development and Characterisation of a Pectin-Based Edible Film That Contains Mulberry Leaf Extract and Its Bio-Active Components. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 121, 107046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, B.R.; Facchi, S.P.; de Oliveira, A.C.; Nunes, C.S.; Souza, P.R.; Vilsinski, B.H.; Popat, K.C.; Kipper, M.J.; Muniz, E.C.; Martins, A.F. Bactericidal Pectin/Chitosan/Glycerol Films for Food Pack Coatings: A Critical Viewpoint. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Yang, J.; Duan, A.; Li, X. Pectin/Sodium Alginate/Xanthan Gum Edible Composite Films as the Fresh-Cut Package. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 181, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wei, N.; Wei, J.; Fang, C.; Feng, T.; Liu, F.; Liu, X.; Wu, B. Curcumin and Silver Nanoparticles Loaded Antibacterial Multifunctional Pectin/Gelatin Films for Food Packaging Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 107046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, M.; Chen, H. Characterization and Functional Properties of a Pectin/Tara Gum Based Edible Film with Ellagitannins from the Unripe Fruits of Rubus Chingii Hu. Food Chem. 2020, 325, 126964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fang, C.; Wei, N.; Wei, J.; Feng, T.; Liu, F.; Liu, X.; Wu, B. Antimicrobial, Antioxidative, and UV-Blocking Pectin/Gelatin Food Packaging Films Incorporated with Tannic Acid and Silver Nanoparticles for Strawberry Preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 308, 142445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, W.Y.; Ahmad Rafiee, A.R.; Leong, C.R.; Tan, W.N.; Dailin, D.J.; Almarhoon, Z.M.; Shelkh, M.; Nawaz, A.; Chuah, L.F. Development of Sodium Alginate-Pectin Biodegradable Active Food Packaging Film Containing Cinnamic Acid. Chemosphere 2023, 336, 139212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, E.; Franco, P.; Campardelli, R.; De Marco, I.; Perego, P. Zein Electrospun Fibers Purification and Vanillin Impregnation in a One-Step Supercritical Process to Produce Safe Active Packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 122, 107082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.W.; Haque, M.A.; Mohibbullah, M.; Khan, M.S.I.; Islam, M.A.; Mondal, M.H.T.; Ahmmed, R. A Review on Active Packaging for Quality and Safety of Foods: Current Trends, Applications, Prospects and Challenges. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 33, 100913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Larez, F.L.; Esquer, J.; Guzmán, H.; Zepeda-Quintana, D.S.; Moreno-Vásquez, M.J.; Rodríguez-Félix, F.; Del-Toro-Sánchez, C.L.; López-Corona, B.E.; Tapia-Hernández, J.A. Effect of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) Parameters on the Recovery of Polyphenols from Pecan Nutshell Waste Biomass and Its Antioxidant Activity. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 10977–10995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunford, N.T.; Gumus, Z.P.; Gur, C.S. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Pecan Shell Water Extracts. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alao, I.I.; Oyekunle, I.P.; Iwuozor, K.O.; Emenike, E.C. Green Synthesis of Copper Nanoparticles and Investigation of Its Antimicrobial Properties. Adv. J. Chem. Sect. B Nat. Prod. Med. Chem. 2022, 4, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rónavári, A.; Igaz, N.; Adamecz, D.I.; Szerencsés, B.; Molnar, C.; Kónya, Z.; Pfeiffer, I.; Kiricsi, M. Green Silver and Gold Nanoparticles: Biological Synthesis Approaches and Potentials for Biomedical Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Maldonado, A.; Bustos-Guadarrama, S.; Espinoza-Gomez, H.; Flores-López, L.Z.; Ramirez-Acosta, K.; Alonso-Nuñez, G.; Cadena-Nava, R.D. Green Synthesis of Copper Nanoparticles Using Different Plant Extracts and Their Antibacterial Activity. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.; Fazilati, M.; Nazem, H.; Mousavi, S.M. Green Synthesis of Magnetic Nanoparticles Using Satureja Hortensis Essential Oil toward Superior Antibacterial/Fungal and Anticancer Performance. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 8822645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nhat, H.; Tan, L.P.; Thien, H.H.; Raes, K.; Le, T.T.; Pham, L.; Quoc, T. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles from Extract from Mentha aquatica Linn. Var. Crispa and Evaluation of Their Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities. Herba Polonica 2023, 69, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Félix, F.; López-Cota, A.G.; Moreno-Vásquez, M.J.; Graciano-Verdugo, A.Z.; Quintero-Reyes, I.E.; Del-Toro-Sánchez, C.L.; Tapia-Hernández, J.A. Sustainable-Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) Waste Extract and Its Antibacterial Activity. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara, N.; Milán, N.S.; Rahman, A.; Mouheb, L.; Boffito, D.C.; Jeffryes, C.; Dahoumane, S.A. Photochemical Synthesis of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles-a Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.P.U.; Dang, N.T.; Doan, L.; Nguyen, T.T.H. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: From Conventional to ‘Modern’ Methods—A Review. Processes 2023, 11, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turdikulov, I.; Atakhanov, A.; Ergashev, D.; Mukhlisa, S.; A’zamkulov, S.; Sardor, O.; Maftuna, M.; Surayyo, F.; Gavharshod, R.; Thomas, S.; et al. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: A Comprehensive Review. Chem. Rev. Lett. 2025, 8, 1155–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwanath, R.; Negi, B. Conventional and Green Methods of Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Antimicrobial Properties. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 4, 100205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salayová, A.; Bedlovičová, Z.; Daneu, N.; Baláž, M.; Lukáčová Bujňáková, Z.; Balážová, L.; Tkáčiková, L. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles with Antibacterial Activity Using Various Medicinal Plant Extracts: Morphology and Antibacterial Efficacy. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Dutt, S.; Sharma, P.; Sundramoorthy, A.K.; Dubey, A.; Singh, A.; Arya, S. Future of Nanotechnology in Food Industry: Challenges in Processing, Packaging, and Food Safety. Glob. Chall. 2023, 7, 2200209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Gautam, P.K.; Verma, A.; Singh, V.; Shivapriya, P.M.; Shivalkar, S.; Sahoo, A.K.; Samanta, S.K. Green Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles as Effective Alternatives to Treat Antibiotics Resistant Bacterial Infections : A Review. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 25, e00427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, Y.K.; Nayak, D.; Mishra, A.K.; Chakrabartty, I.; Ray, M.K.; Mohanta, T.K.; Tayung, K.; Rajaganesh, R.; Vasanthakumaran, M.; Muthupandian, S.; et al. Green Synthesis of Endolichenic Fungi Functionalized Silver Nanoparticles: The Role in Antimicrobial, Anti-Cancer, and Mosquitocidal Activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabadi, H.; Jounaki, K.; Pishgahzadeh, E.; Morad, H.; Sadeghian-Abadi, S.; Vahidi, H.; Hussain, C.M. Antiviral Potential of Green-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles. In Handbook of Microbial Nanotechnology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 285–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M.K.Y.; Abu-Elghait, M.; Salem, S.S.; Azab, M.S. Multifunctional Properties of Silver and Gold Nanoparticles Synthesis by Fusarium pseudonygamai. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2022, 14, 28253–28270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña-Pacheco, L.V.; Moreno-Robles, A.L.; Plascencia-Jatomea, M.; Del Toro-Sánchez, C.L.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F.; Tapia-Hernández, J.A.; Moreno-Vásquez, M.J.; Graciano-Verdugo, A.Z. The Preparation and Characterization of an Alginate—Chitosan-Active Bilayer Film Incorporated with Asparagus (Asparagus officinalis L.) Residue Extract. Coatings 2024, 14, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.R.; Natarajan, A.; Pandey, S.S. Bioinspired Multifunctional Silver Nanoparticles for Optical Sensing. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2023, 11, 4549–4571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugan, D.; Tintelott, M.; Narayanan, M.S.; Vu, X.T.; Kurkina, T.; Rodriguez-Emmenegger, C.; Schwaneberg, U.; Dostalek, J.; Ingebrandt, S.; Pachauri, V. Recent Advances in Grating Coupled Surface Plasmon Resonance Technology. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2401862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira-Vielma, A.A.; Meléndez-Ortiz, H.I.; García-López, J.I.; Sanchez-Valdes, S.; Cruz-Hernández, M.A.; Rodríguez-González, J.G.; Ramírez-Barrón, S.N. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Pecan Nut (Carya illinoinensis) Shell Extracts and Evaluation of Their Antimicrobial Activity. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasieczna-Patkowska, S.; Cichy, M.; Flieger, J. Application of Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy in Characterization of Green Synthesized Nanoparticles. Molecules 2025, 30, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Córdova, M.A.; Sánchez, E.; Muñoz-Márquez, E.; Ojeda-Barrios, D.L.; Soto-Parra, J.M.; Preciado-Rangel, P. Phytochemical Composition and Antioxidant Capacity in Mexican Pecan Nut. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2017, 29, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manessis, G.; Kalogianni, A.I.; Lazou, T.; Moschovas, M.; Bossis, I.; Gelasakis, A.I. Plant-Derived Natural Antioxidants in Meat and Meat Products. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolat, E.; Sarıtaş, S.; Duman, H.; Eker, F.; Akdaşçi, E.; Karav, S.; Witkowska, A.M. Polyphenols: Secondary Metabolites with a Biological Impression. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Jiang, W. Antioxidant and Antibacterial Chitosan Film with Tea Polyphenols-Mediated Green Synthesis Silver Nanoparticle via a Novel One-Pot Method. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 1252–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman-Puyol, S.; Benítez, J.J.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.A. Transparency of Polymeric Food Packaging Materials. Food Res. Int. 2022, 161, 111792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, M.; Liu, C.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Y. Catharanthus Roseus Extract-Assisted Silver Nanoparticles Chitosan Films with High Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties for Fresh Food Preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 309, 142771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medici, S.; Peana, M.; Pelucelli, A.; Zoroddu, M.A. An Updated Overview on Metal Nanoparticles Toxicity. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021, 76, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Huang, J.; Yun, D.; Yong, H.; Liu, J. Antioxidant Packaging Films Developed Based on Chitosan Grafted with Different Catechins: Characterization and Application in Retarding Corn Oil Oxidation. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 133, 107970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Total Phenols (μg GAE/g PS) | Total Flavonoids (μM QE/g PS) |

|---|---|---|

| Silver microparticles | 42.82 ± 6.8 B | 4.38 ± 0.54 B |

| Pecan nutshell extract | 138.98 ± 2.5 A | 22.10 ± 2.95 A |

| Sample | Micromoles of Trolox Equivalents (μmol TE/g PS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ABTS | DPPH | FRAP | |

| Silver microparticles | 7728.39 ± 46.6 C | 2562.54 ± 110.2 B | 1800.45 ± 82.0 B |

| Pecan nutshell extract | 941.37 ± 3.2 A | 2859.37 ± 17.7 A | 1882.78 ± 129.6 B |

| TBHQ | 269.31 ± 23.3 D | 2058.01 ± 66.6 C | 2521.75 ± 55.8 B |

| Film | Color | Thickness | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | ΔE | (μm) | |

| Z/P | 74.42 ± 1.50 A | 5.18 ± 1.44 A | 46.31 ± 6.17 A | 251.60 ± 32.26 A | |

| Z/P 0.25% AgMp | 38.23 ± 4.39 B | 21.00 ± 4.39 B | 20.64 ± 8.39 B | 48.07 ± 2.26 A | 243.80 ± 30.52 B |

| Z/P 0.5% AgMp | 31.66 ± 5.25 B | 22.91 ± 5.25 B | 16.87 ± 6.00 B | 55.42 ± 4.11 A | 257.30 ± 44.75 B |

| Z/P 1% AgMp | 28.96 ± 1.93 B | 21.46 ± 1.93 B | 22.29 ± 3.93 B | 54.07 ± 2.67 A | 258.70 ± 30.62 B |

| Sample | Micromoles of Trolox Equivalents (μmol TE/g PS) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ABTS | DPPH | FRAP | |

| Z/P | 50.57 ± 1.1 B | 204.07 ± 12.7 B | 230.66 ± 12.1 A |

| Z/P 0.25% AgMp | 45.95 ± 1.6 B | 274 ± 11.3 A | 225.55 ± 8.9 A |

| Z/P 0.5% AgMp | 62.11 ± 4.6 A | 192.11 ± 6.5 B | 227.04 ± 8.0 A |

| Z/P 1% AgMp | 64.29 ± 3.9 A | 210 ± 2.4 B | 221.30 ± 4.0 A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ozuna-Valencia, K.H.; Barreras-Urbina, C.G.; Tapia-Hernández, J.A.; Moreno-Vásquez, M.d.J.; Graciano-Verdugo, A.Z.; Robles-García, M.Á.; Quintero-Reyes, I.E.; Rodríguez-Félix, F. Green Synthesis of Silver Particles Using Pecan Nutshell Extract: Development and Antioxidant Characterization of Zein/Pectin Active Films. Processes 2026, 14, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010004

Ozuna-Valencia KH, Barreras-Urbina CG, Tapia-Hernández JA, Moreno-Vásquez MdJ, Graciano-Verdugo AZ, Robles-García MÁ, Quintero-Reyes IE, Rodríguez-Félix F. Green Synthesis of Silver Particles Using Pecan Nutshell Extract: Development and Antioxidant Characterization of Zein/Pectin Active Films. Processes. 2026; 14(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleOzuna-Valencia, Karla Hazel, Carlos Gregorio Barreras-Urbina, José Agustín Tapia-Hernández, María de Jesús Moreno-Vásquez, Abril Zoraida Graciano-Verdugo, Miguel Ángel Robles-García, Idania Emedith Quintero-Reyes, and Francisco Rodríguez-Félix. 2026. "Green Synthesis of Silver Particles Using Pecan Nutshell Extract: Development and Antioxidant Characterization of Zein/Pectin Active Films" Processes 14, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010004

APA StyleOzuna-Valencia, K. H., Barreras-Urbina, C. G., Tapia-Hernández, J. A., Moreno-Vásquez, M. d. J., Graciano-Verdugo, A. Z., Robles-García, M. Á., Quintero-Reyes, I. E., & Rodríguez-Félix, F. (2026). Green Synthesis of Silver Particles Using Pecan Nutshell Extract: Development and Antioxidant Characterization of Zein/Pectin Active Films. Processes, 14(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010004