Mechanical and Shrinkage Properties of Alkali-Activated Binder-Stabilized Expansive Soils

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

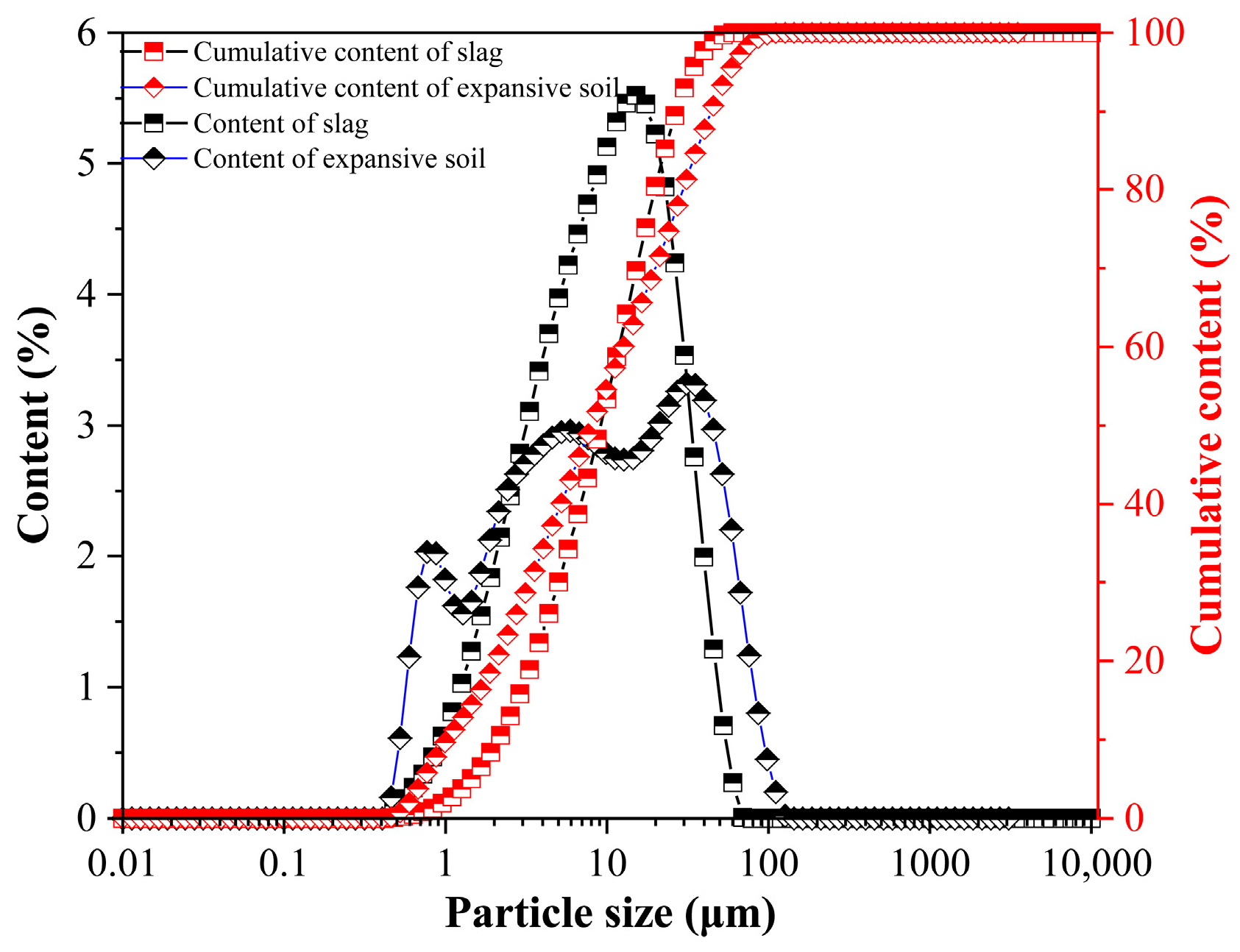

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Mix Proportion and Samples

2.3. Testing Methods of Samples

2.3.1. Setting Times

2.3.2. Fluidity

2.3.3. Hydration Kinetics

2.3.4. Autogenous Shrinkage

2.3.5. Hydration Products Analysis

2.3.6. Compressive Strength

2.3.7. Microstructural Characterization

3. Results

3.1. Setting Times

3.2. Fluidity

3.3. Hydration Kinetics

3.4. Autogenous Shrinkage

3.5. XRD

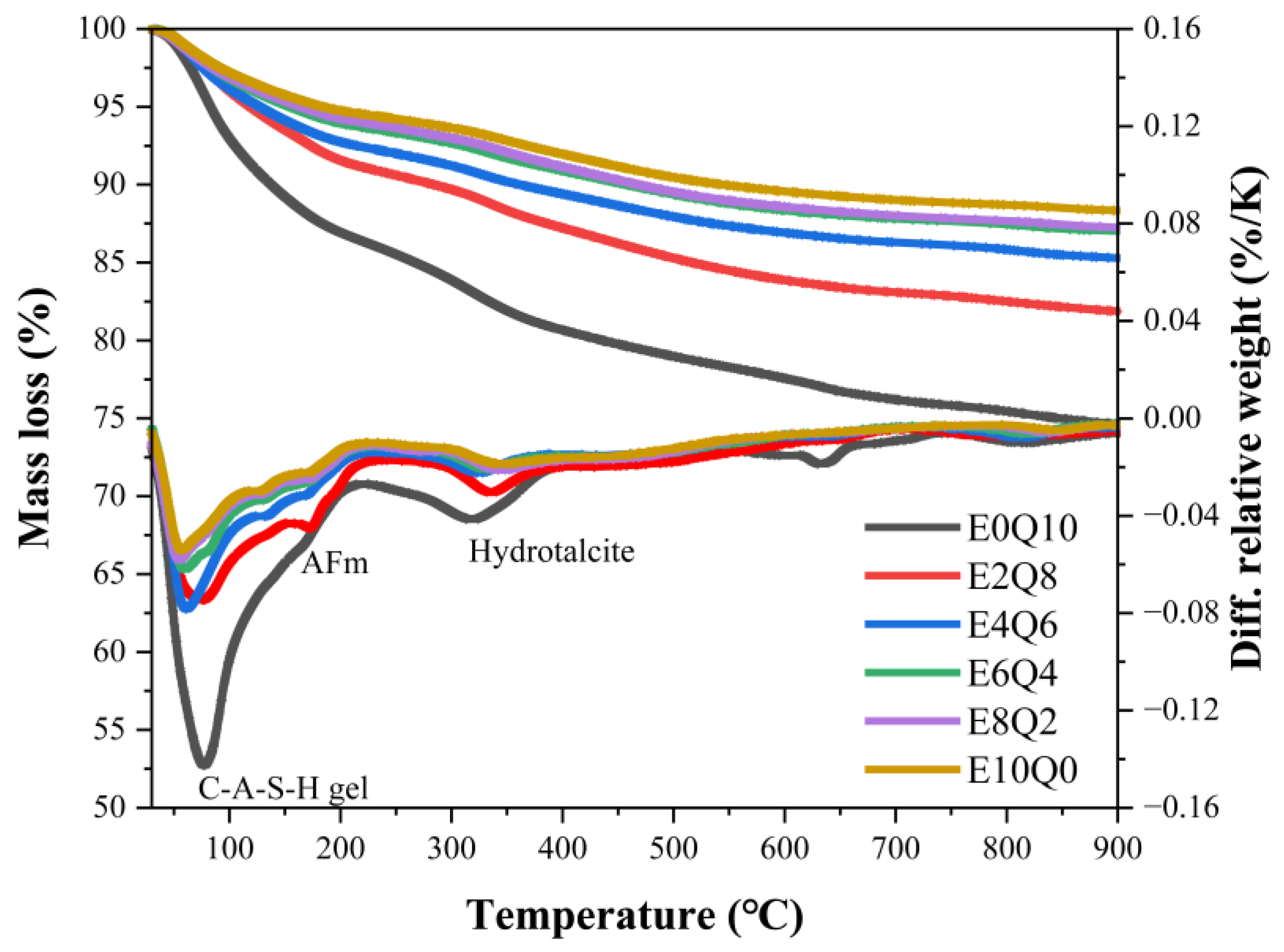

3.6. TG-DTG

3.7. Compressive Strength

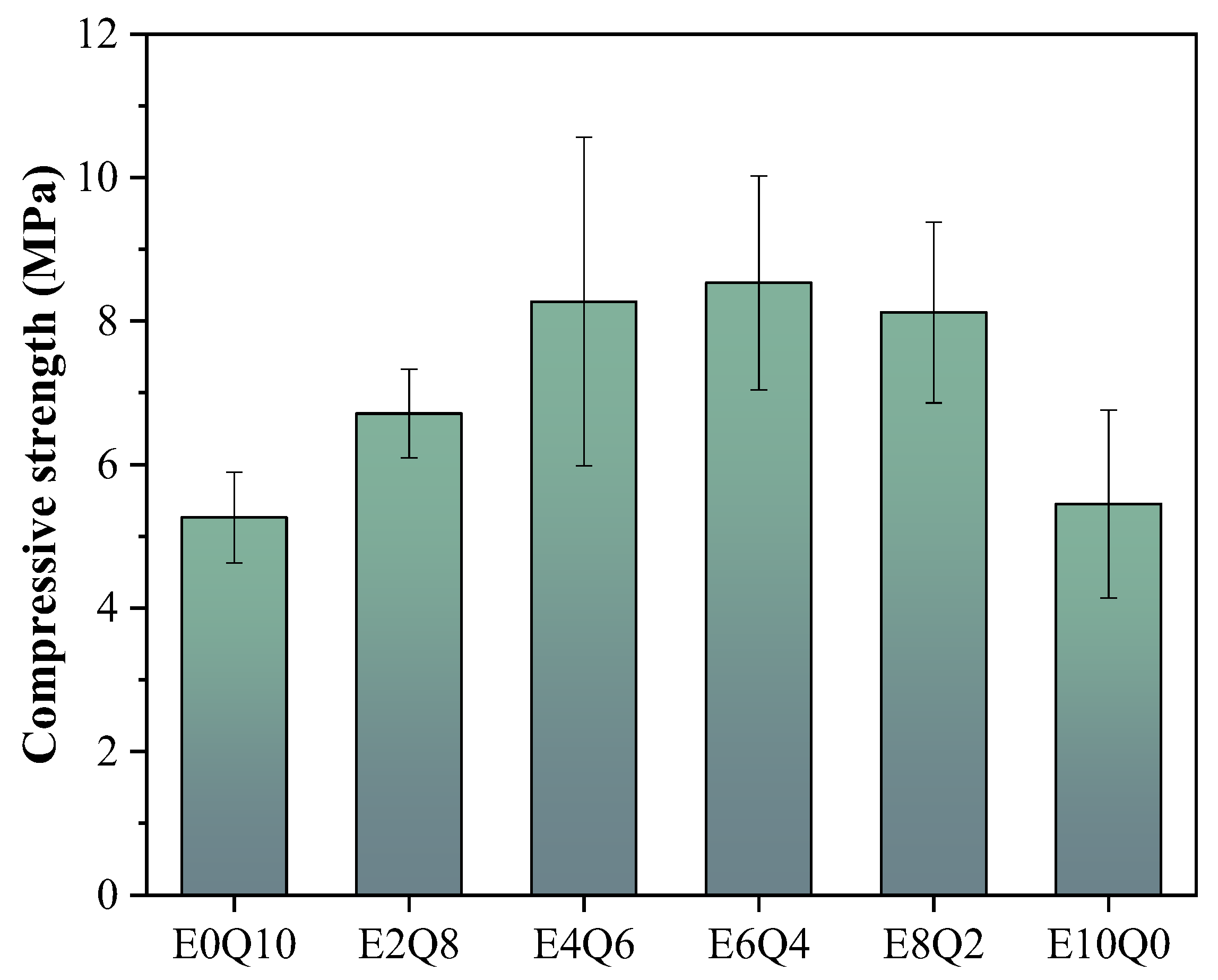

3.7.1. Compressive Strength for 7 Days

3.7.2. Unconfined Compressive Strength for 10 Days

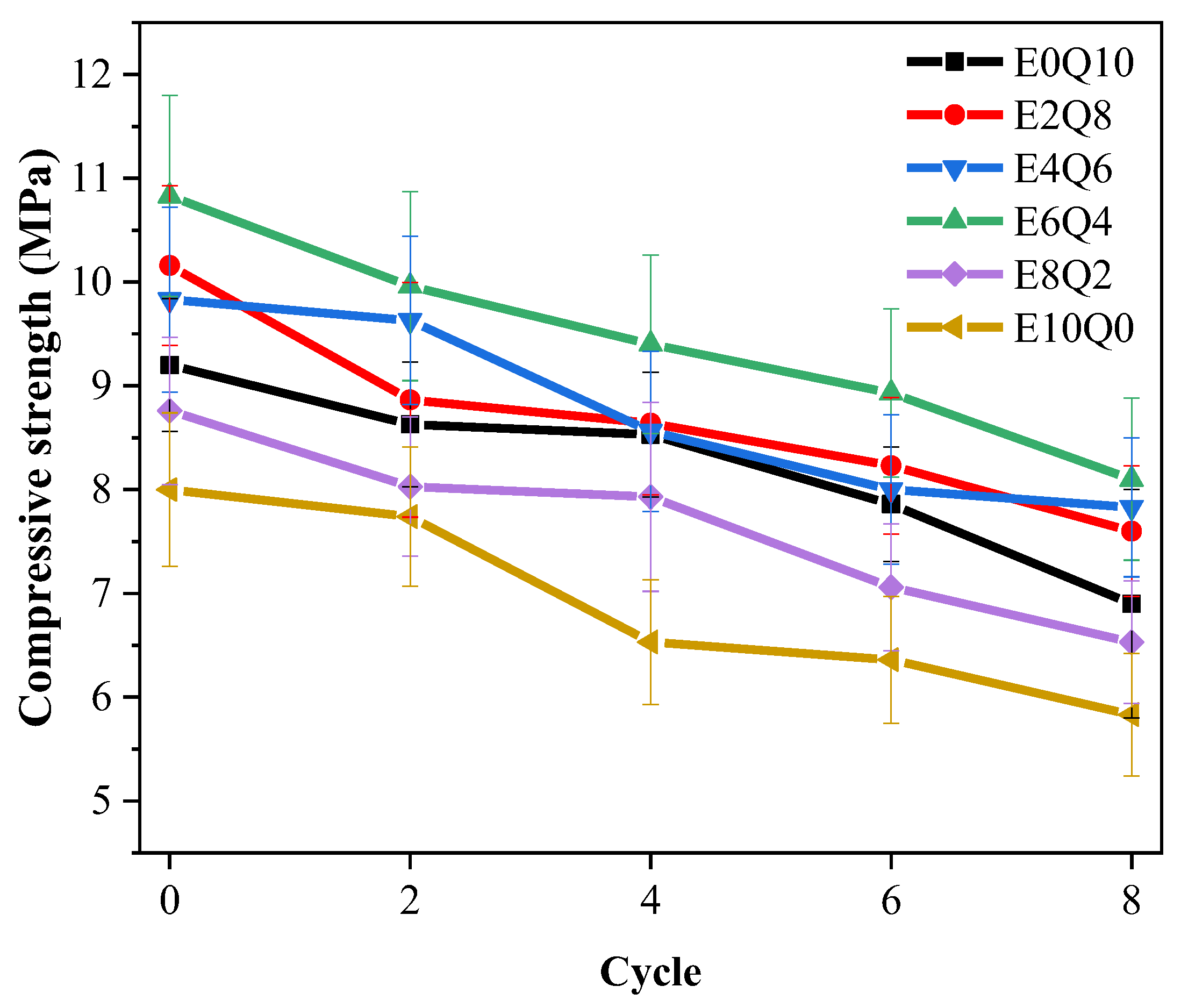

3.7.3. Unconfined Compressive Strength for Drying and Wetting Cycle

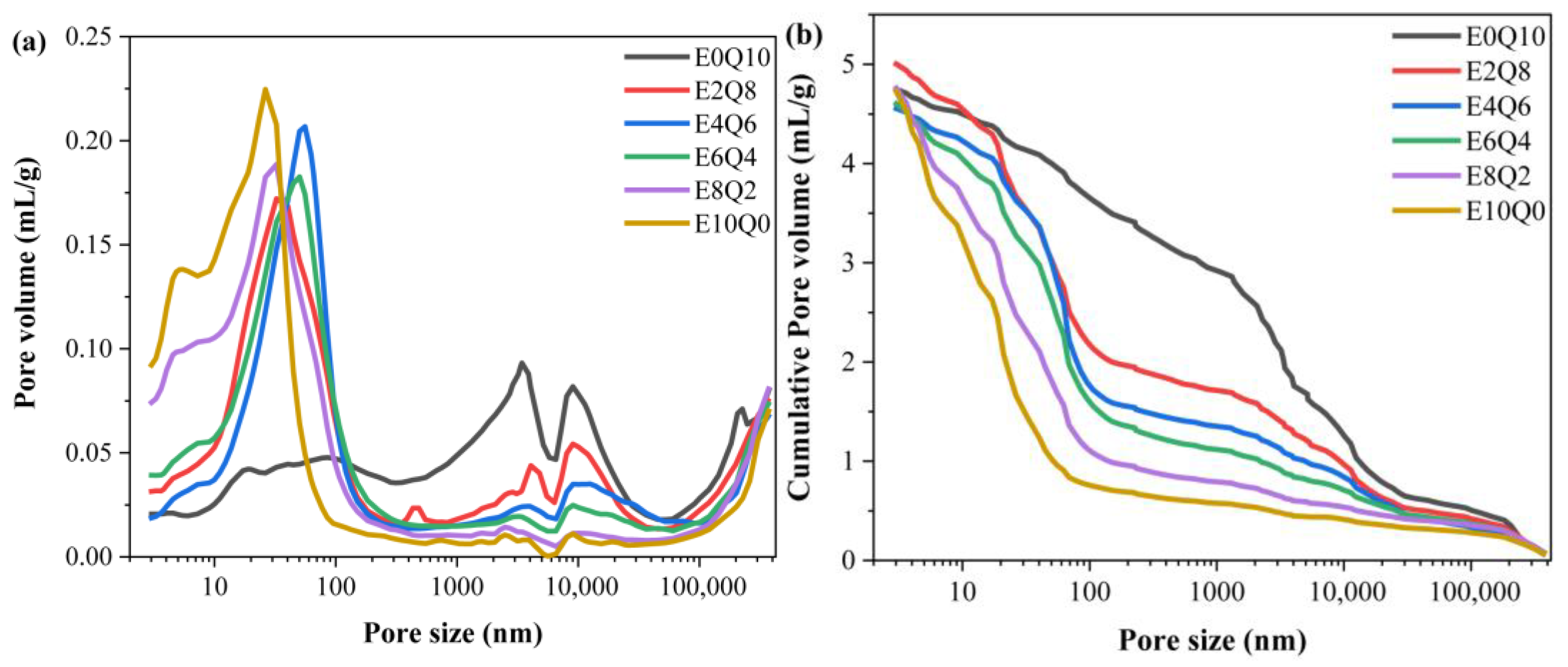

3.8. MIP

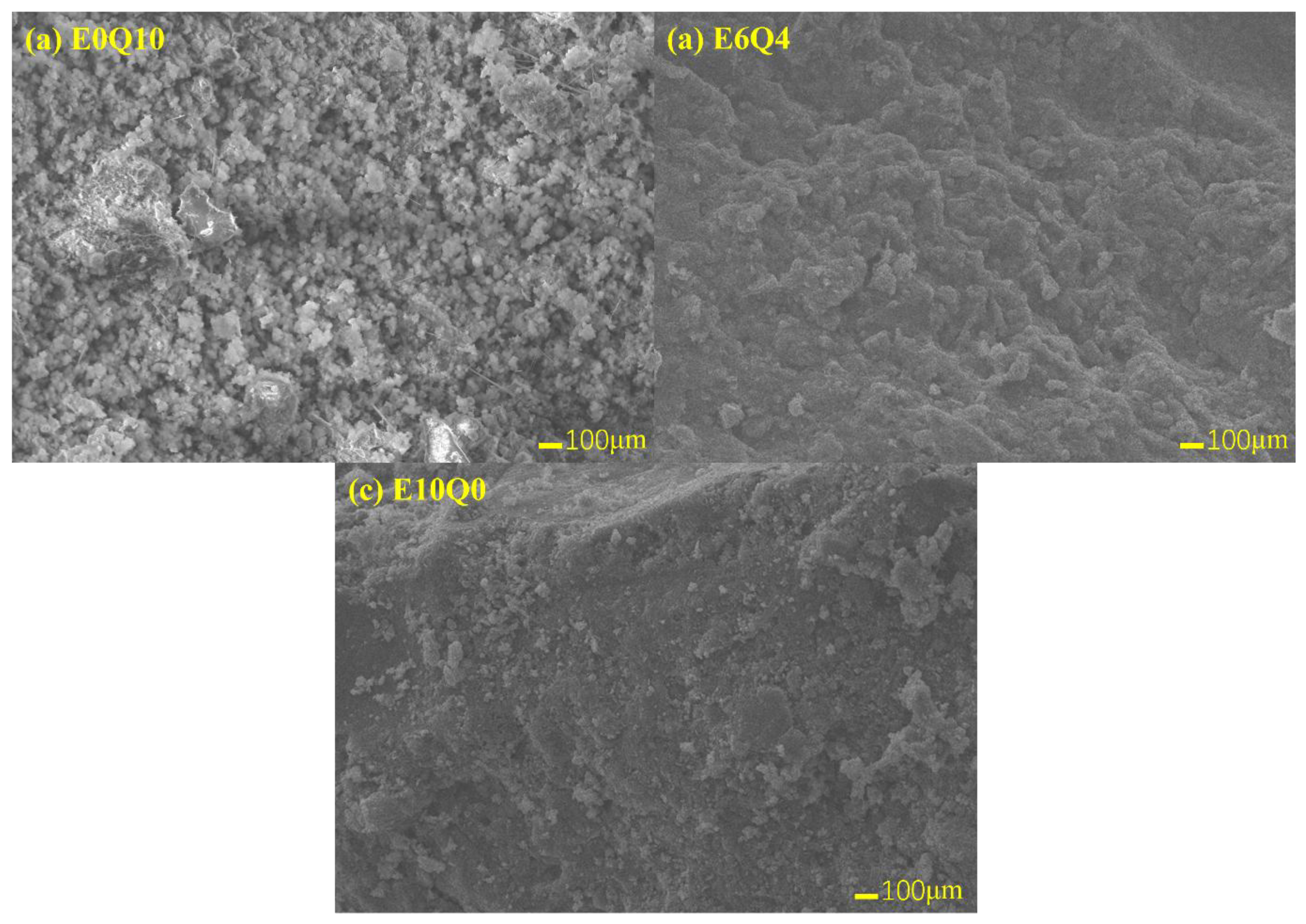

3.9. SEM

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Syed, M.; GuhaRay, A.; Goel, D. Strength characterisation of fiber reinforced expansive subgrade soil stabilized with alkali activated binder. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2021, 23, 1037–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Gu, L.; Liu, S. Microstructural and mechanical properties of marine soft clay stabilized by lime-activated ground granulated blastfurnace slag. Appl. Clay Sci. 2015, 103, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppala, A.J.; Pedarla, A. Innovative ground improvement techniques for expansive soils. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2017, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, F.; Liu, S.; Du, Y.; Cui, K. Behavior of expansive soils stabilized with fly ash. Nat. Hazards 2008, 47, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldesenbet, T.T. Experimental Study on Stabilized Expansive Soil by Blending Parts of the Soil Kilned and Powdered Glass Wastes. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 12, 9645589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamei, T.; Ahmed, A.; Ugai, K. Durability of soft clay soil stabilized with recycled Bassanite and furnace cement mixtures. Soils Found. 2013, 53, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppala, A.J.; Manosuthikij, T.; Chittoori, B.C.S. Swell and shrinkage characterizations of unsaturated expansive clays from Texas. Eng. Geol. 2013, 164, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraei, A.; Herki, B.M.A.; Sherwani, A.F.H.; Zare, S. Slope Stability in Swelling Soils Using Cement Grout: A Case Study. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2018, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltz, G.; Cuisinier, O.; Masrouri, F. Weathering of a lime-treated clayey soil by drying and wetting cycles. Eng. Geol. 2014, 181, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Xu, G.; Yan, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, D.; Cai, G.; Sun, Y.; Chen, R.; Pu, S.; Shi, X. Study on the optimization and performance of expansive soil stabilized by alkali-activated fly ash-phosphogypsum using response surface methodology. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 114032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, W.; Wang, B.; Zhan, X.; Zuo, J.; Shan, Y.; Han, S.; Wang, T. Synergistic effects of cement–silica fume composite on expansive soil stabilization: Mechanisms, microstructure, and durability. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhendro, B. Toward Green Concrete for Better Sustainable Environment. Procedia Eng. 2014, 95, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provis, J.L.; Palomo, A.; Shi, C. Advances in understanding alkali-activated materials. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 78, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Fan, C.; Wang, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z. Workability, rheology, and geopolymerization of fly ash geopolymer: Role of alkali content, modulus, and water–binder ratio. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 367, 130357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, B.; Chang, J. Adsorption behavior and solidification mechanism of Pb(II) on synthetic C-A-S-H gels with different Ca/Si and Al/Si ratios in high alkaline conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 493, 152344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Provis, J.L.; Cizer, Ö.; Ye, G. Autogenous shrinkage of alkali-activated slag: A critical review. Cem. Concr. Res. 2023, 172, 107244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraki, H.; Shariatmadari, N.; Ghadir, P.; Jahandari, S.; Tao, Z.; Siddique, R. Clayey soil stabilization using alkali-activated volcanic ash and slag. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 14, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, M.; GuhaRay, A.; Kar, A. Stabilization of Expansive Clayey Soil with Alkali Activated Binders. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2020, 38, 6657–6677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianynejad, M.; Toufigh, M.M.; Toufigh, V. Mechanical Performance of Alkali-activated Stabilized Sandy Soil Reinforced with Glass Wool Residue Microfibers. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, S. Alkali-Activated Ground-Granulated Blast Furnace Slag for Stabilization of Marine Soft Clay. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2015, 27, 04014146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C191; Standard Test Methods for Time of Setting of Hydraulic Cement by Vicat Needle. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM C1437; Standard Test Method for Flow of Hydraulic Cement Mortar. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ASTM C476; Standard Specification for Grout for Masonry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- ASTM C1702; Standard Test Method for Measurement of Heat of Hydration of Hydraulic Cementitious Materials Using Isothermal Conduction Calorimetry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ASTM C1698; Standard Test Method for Autogenous Strain of Cement Paste and Mortar. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- Pei, C.; Chen, P.; Tan, W.; Zhou, T.; Li, J. Effect of wet copper tailings on the performance of high-performance concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 74, 106931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C192; Standard Practice for Making and Curing Concrete Test Specimens in the Laboratory. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- Parhi, P.S.; Garanayak, L.; Mahamaya, M.; Das, S.K. Stabilization of an Expansive Soil Using Alkali Activated Fly Ash Based Geopolymer. In Advances in Characterization and Analysis of Expansive Soils and Rocks; Hoyos, L.R., McCartney, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, D.; Jia, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, P.; Yu, B. Effects of Mud Content on the Setting Time and Mechanical Properties of Alkali-Activated Slag Mortar. Materials 2023, 16, 3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Luo, Q.; Jiang, L.; Cao, Z.; Wang, T.; Zhang, L. Fluidized solidification modification tests on expansive soil and its mixing proportions study. J. Zhejiang Univ. Eng. Sci. 2024, 58, 2137–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, W.; Ling, J. Evaluation the performance of controlled low strength material made of excess excavated soil. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y. Perforated cenospheres: A reactive internal curing agent for alkali activated slag mortars. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 104, 103351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salles, F.; Douillard, J.-M.; Bildstein, O.; Gaudin, C.; Prelot, B.; Zajac, J.; Van Damme, H. Driving force for the hydration of the swelling clays: Case of montmorillonites saturated with alkaline-earth cations. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 395, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srasra, E.; Bekri-Abbes, I. Bentonite clays for therapeutic purposes and biomaterial design. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, K. Effect of clay content on shrinkage of cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 322, 125959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, N.; Dai, F.; Meng, L.; Rehman, Z.u.; Zhang, H. Integrating lignosulphonate and hydrated lime for the amelioration of expansive soil: A sustainable waste solution. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 254, 119985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, P.; Li, S.; Shen, X.; Fang, J.; Gu, Z.; Wang, Y. Enhancing the performance of NaOH-activated slag using waste green tea extract as a multi-function admixture. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.; Bernal, S.A.; Provis, J.L.; Hamdan, S.; van Deventer, J.S.J. Drying-induced changes in the structure of alkali-activated pastes. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 3566–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, A.; Heath, A.; Patureau, P.; Evernden, P.; Walker, P. Influence of clay minerals and associated minerals in alkali activation of soils. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 229, 116816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lv, B.; Zhang, C.; Li, N.; Pu, S. Mechanical and micro-structure characteristics of cement-treated expansive soil admixed with nano-MgO. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi Chenarboni, H.; Hamid Lajevardi, S.; MolaAbasi, H.; Zeighami, E. The effect of zeolite and cement stabilization on the mechanical behavior of expansive soils. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 272, 121630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Wang, C.; Yan, Y.; Yi, S.; Teng, K.; Li, C. Study on Mechanism of Mechanical Property Enhancement of Expansive Soil by Alkali-Activated Slag. Materials 2025, 18, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Mo, P.; Tian, Q.; Miao, Q.; Liu, D.; Pan, J. Study on Strength and Micromorphology of Expansive Soil Improved by Cement–Coal Gangue under Dry–Wet Cycle. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2024, 2024, 9976102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lu, K.; Wu, Z.; Liu, X.; Garg, A.; Qin, Y.; Mei, G.; Lv, C. Expansive soil improvement using industrial bagasse and low-alkali ecological cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 423, 135806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Feng, J.; Wang, B. Relationship between fractal feature and compressive strength of fly ash-cement composite cementitious materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 139, 105052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, T.; Yan, C.; Wang, J. Expansive Soil Stabilization Using Alkali-Activated Fly Ash. Processes 2023, 11, 1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | K2O | TiO2 | MgO | CaO | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expansive soils | 82.63 | 11.04 | 2.96 | 1.48 | 1.15 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.26 |

| Slag | 27.2 | 18.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | - | 7.8 | 45.2 | 0.8 |

| Groups | Expansive Soils | Quartz Powder | Slag | Superplasticizer | NaOH | Water Glass | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E0Q10 | 0 | 49.83 | 19.93 | 0.35 | 3.15 | 12.53 | 14.32 |

| E2Q8 | 9.96 | 39.86 | 19.93 | 0.35 | 3.15 | 12.53 | 14.32 |

| E4Q6 | 19.63 | 29.90 | 19.93 | 0.35 | 3.15 | 12.53 | 14.32 |

| E6Q4 | 29.90 | 19.63 | 19.93 | 0.35 | 3.15 | 12.53 | 14.32 |

| E8Q2 | 39.86 | 9.96 | 19.93 | 0.35 | 3.15 | 12.53 | 14.32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wei, Y.; Tan, W.; Ju, J.-W.W.; Tian, Y.; Feng, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, Q.; Chen, P. Mechanical and Shrinkage Properties of Alkali-Activated Binder-Stabilized Expansive Soils. Processes 2026, 14, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010003

Wei Y, Tan W, Ju J-WW, Tian Y, Feng S, Wang C, Wang Q, Chen P. Mechanical and Shrinkage Properties of Alkali-Activated Binder-Stabilized Expansive Soils. Processes. 2026; 14(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Yongke, Weibo Tan, Jiann-Wen Woody Ju, Yinghui Tian, Shouzhong Feng, Changbai Wang, Qiang Wang, and Peiyuan Chen. 2026. "Mechanical and Shrinkage Properties of Alkali-Activated Binder-Stabilized Expansive Soils" Processes 14, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010003

APA StyleWei, Y., Tan, W., Ju, J.-W. W., Tian, Y., Feng, S., Wang, C., Wang, Q., & Chen, P. (2026). Mechanical and Shrinkage Properties of Alkali-Activated Binder-Stabilized Expansive Soils. Processes, 14(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010003