Abstract

The incorporation of utilized plastic waste into concrete mix designs for precast pavement applications presents a highly efficacious strategy, yielding demonstrably superior mechanical properties. High-density polyethylene (HDPE) is the proposed type of plastic in this study. It demonstrates remarkable performance and durability characteristics. The methodology not only significantly curtails landfill waste and incineration but also contributes to a reduction in energy consumption within the concrete sector, thereby establishing itself as a definitive sustainable solution that addresses environmental, economic, and societal imperatives. The optimal incorporation ratio for the recycled plastic within concrete matrices is determined to fall between 10% and 15%, as this range facilitates the attainment of the most desirable material properties. This study specifically focuses on plastic waste and the incorporation of recycled plastic into concrete materials. The emphasis on plastic is due to its material properties, which are particularly well-suited for concrete applications. Experimental tests are conducted on recycled concrete in comparison with the conventional concrete. The results demonstrate high mechanical properties to the recycled concrete. The novelty of this research is the type of plastic used in the concrete mix. Although most of the worldwide applications use Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET), HDPE showed exceeding properties and performance. Two important factors that influence the architectural aspect of construction materials are the heat island effect and the solar reflective index. These factors affect the energy absorption and emissivity rates of construction materials. The embodied carbon in the concrete mix impacts environmental and energy consumption rates, which directly relate to climate change, one of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

1. Introduction

Currently, the world is grappling with a crisis of dwindling essential resources, particularly non-renewable energy. As a result, the focus has shifted towards sustainability and energy conservation. Different industries have adopted various methodologies to achieve these goals, such as the cradle-to-cradle concept and the non-endless cycle. Implementing these concepts on multiple levels is critical to sustaining current resources for future generations. The misuse of natural resources has already begun to affect people, and all countries are now seeking achievable alternatives. The cradle-to-cradle concept is seeking the continuous cycle starting from the production of virgin plastic to the reuse process. Plastic manufacturing witnessed an astonishing 200-fold increase between 1950 and 2014, with projections indicating a doubling of current production volumes by 2050. The worldwide adoption and advancement of effective recycling methodologies have been notably sluggish. The prevailing approach to plastic utilization is characterized by a ‘‘cradle-to-grave’’ philosophy, emphasizing short-term use without including integrated recycling mechanisms [1,2].

The chasm between plastic production and its subsequent waste management is profound, resulting in disparate recycling rates globally. A mere 9% of the 330 million metric tons of plastic produced each year is recycled. In contrast, 12% is incinerated, and a staggering 79% is relegated to landfills. This alarming trajectory has led to a considerable accumulation of plastic waste and a persistent failure to confront this critical issue [1,3,4,5].

Concurrently, the concrete sector grapples with formidable energy consumption, positioning it as a primary contributor to environmental pollution. The industry’s extended construction timelines and specific concrete mix designs are key drivers of this trend, compounded by substantial waste generation and resource depletion. This underscores the imperative for innovative, sustainable alternatives that can foster energy conservation. As non-renewable energy sources and raw materials dwindle, the industry must urgently identify viable and efficient solutions to satisfy contemporary demands while simultaneously safeguarding the planet for future generations [6,7].

Scholarly discourse has increasingly focused on synergistic endeavors with energy-intensive sectors, notably construction, to facilitate the reprocessing of plastic waste. Investigations have demonstrated plastic’s potential to be transmuted into economical and ecologically sound materials, thereby conferring considerable value upon the construction industry. For example, the incorporation of recycled plastic as an aggregate substitute in concrete production represents a more sustainable methodological paradigm [8].

The integration of recycled plastic and concrete has seen implementation across both industrialized and developing nations, presenting a propitious avenue for further exploration and refinement of these strategies. Our present study will delve into diverse methodologies for plastic recycling, commencing with an exhaustive analysis of plastic waste and its recycled counterparts. Each distinct type possesses unique specifications and implementation protocols, which will be thoroughly elucidated herein [9,10].

As mentioned in this study, various types of plastic have different characteristics; each has its own characteristics that serve specific applications. Utilizing recycled plastic in the applications of the concrete industry is a recent approach that allows a platform for more trials and additions. Beyond plastic, a wide array of waste materials can serve as viable substitutes for conventional coarse aggregates in concrete mixes. Since this study aims to utilize recycled plastic in pavement applications and widen the horizon of recycled plastic in the construction industry, the method will experiment with different types of recycled plastics to enhance the pavement application properties, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Virgin plastic and recycled plastic [11].

The types of plastics are as follows [7,9,11]:

- Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET or PETE);

- High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE);

- Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC or Vinyl);

- Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE);

- Polypropylene (PP);

- Polystyrene (PS or Styrofoam).

Referring to the different plastic types, HDPE can be mixed and experimented with, as its characteristics and typical applications can fit in pavement applications, such as eco-friendly paver tiles and landscape pavements [11]. HDPE is produced by 13%, while used by 19%. This shows the high demand for HDPE in the market in various applications. However, the municipal solid waste (MSW) percentage of plastics, which is almost the second-highest solid waste quantity, is 12.2%. The reutilization of plastics is widely applicable and in high demand in the market. This is because of the efficient properties of the plastic materials in the recycled applications. For example, recycled plastic is used in the textile industry for its durability [7].

Various guidelines should be tackled regarding the advantages and limitations of plastic types. The first one is the right way to play with the materials without imposing limitations affecting the applications of the plastic types. In other words, the ability to treat some of these limitations, for example, by adding additives, can be minimized or treated.

The study employs the impact of plastic waste on various concrete properties. There are main properties that should be tested in order to maintain the standard properties and the functionality of the concrete mix design. The study also evaluates and compares the mechanical properties of conventional and recycled plastic concrete, focusing on compressive and tensile strength, as well as durability.

The impact of plastic waste on concrete properties depends on the type of plastic used and the specific formulation of the concrete mix. Additionally, how the plastic waste is prepared plays a pivotal role in determining this effect. Incorporating plastic can influence the workability of the concrete mix, particularly in terms of binding and strength.

A study found that incorporating plastic into the concrete mix leads to a reduction in bulk density as the plastic content increases. This decrease in density is primarily attributable to the lower density of plastic compared to the sand or aggregate it replaces. However, when the plastic is properly shredded, it can significantly improve both the binding properties and workability of the mix. As a result, this may contribute to stronger concrete and enhanced characteristics of the hardened material.

The key impacts are as follows: [12]

- Workability (it might be decreased because of the shredding size);

- Density (the material is lighter in weight, rendering it suitable for non-structural applications);

- Compressive and tensile strength (its strength can be comparable to conventional materials, given that the plastic waste is adequately shredded and treated);

- Shredding size;

- Water absorption (elevated levels may occur if the shredding size and compaction processes are not properly executed);

- It is crucial to note that the percentage of plastic in the mix should not exceed 15%, as higher concentrations may lead to voids that weaken the concrete. In contrast, including less than 10% plastic typically has little to no notable effect on strength.

Plastic recycling methodologies diverge significantly, necessitated by the inherent variations among different plastic types. Furthermore, national recycling strategies are profoundly shaped by the prevailing availability of plastic waste within a given country. For instance, while developing nations frequently contend with an abundance of HDPE plastics, the widespread recycling of plastic remains largely unadopted. Consequently, the selection of a specific plastic for recycling is contingent upon both its availability and its categorical classification [13].

The study endeavors to investigate HDPE, another ubiquitous plastic type prevalent in packaging applications. A significant proportion of energy embedded within discarded and incinerated waste is squandered due to unsustainable practices, thereby failing to align with the principles of a circular economy focused on closed-energy loop utilization. Furthermore, World Data indicates that, “The United States produces the most plastic waste per capita worldwide, with the average American producing 130.09 kg of plastic waste per year. The U.S. generated more than 42 million metric tons of plastic waste in 2016, making it the World’s biggest plastic waste generator” [1,2].

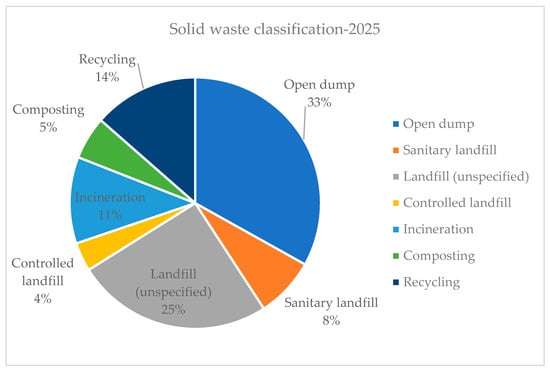

Figure 1 illustrates the varying MSW quantities directed to landfills. The chart shows that the predominant disposal method of the MSW is landfilling, far surpassing the volumes that are either incinerated or recycled; this is based on the World bank group. This trend highlights a significant deficit in the implementation of sustainable alternative waste management strategies, such as comprehensive recycling programs.

Figure 1.

Different quantities of MSW are reaching landfills, incineration, and recycling worldwide 2022 [14].

Consequently, this has led to the importance and the need for recognizing potential sustainability and recent initiatives from the European Commission towards recycled plastic. As measured towards increasing the applications from recycled plastic, considered by the EU, “The European Union (EU) takes measures to increase plastic recycling, introducing higher targets for recycling in its revised waste legislation. Sweden follows suit, prioritizing actions for improving plastic waste management” [3].

Improper waste disposal presents a significant environmental challenge. A primary concern is that the indiscriminate dumping of waste obstructs drainage systems, leading to substantial damage, particularly during periods of heavy rainfall. Furthermore, the emission of noxious gases, such as methane, contributes to the greenhouse effect. Additionally, the proliferation of plastics in our oceans is a major factor in the degradation of marine ecosystems. Consequently, a robust waste management system is imperative. Such a system is essential for mitigating these environmental harms and safeguarding the planet. As noted, the plastic waste management flow model can facilitate this effort by quantitatively assessing environmental, economic, and social impacts. The model’s key indicators for describing across each dimension of sustainability include [4,7,15]

- GHG emissions;

- Monetary costs and benefits;

- Number of jobs created.

Furthermore, demographic expansion remains a persistent trend across a majority of nations, particularly within developing economies. A direct correlation exists between elevated population density and increased waste generation.

Pollution, an inherent consequence of population growth, arises from inadequate waste management strategies. The pervasive issue of plastic waste, categorized into micro and macro forms, is commonly discharged into aquatic environments. This leads to severe marine pollution, often resulting in the demise of various marine species. Moreover, plastics exhibit prolonged persistence in marine ecosystems, accumulating over decades, as illustrated in the accompanying data. This accumulation poses a significant threat to marine life. Microplastics, defined as particles smaller than 0.5 cm, are readily ingested via water, subsequently impeding the growth and development of aquatic organisms. Consequently, the detrimental effects of microplastics extend to human health through the introduction of toxic substances. A striking factor is that approximately 50% of all plastic waste originates from household refuse, primarily in the form of packaging. This discarding of contaminated plastic packaging, followed by its attempted reuse, exacerbates the problem, leading to what is termed the “comingled plastics effect” [8].

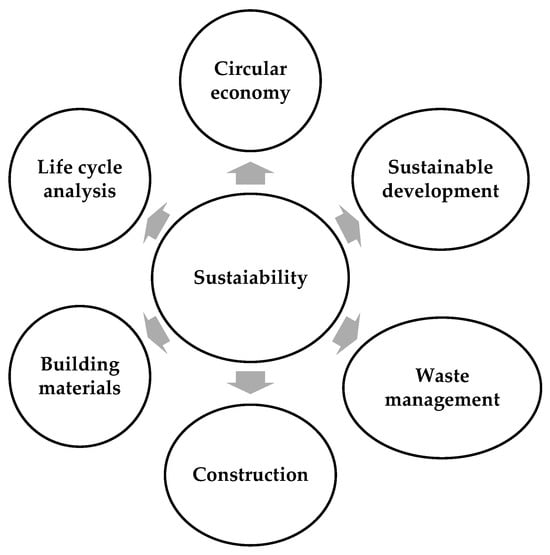

As depicted in Figure 2, a thorough life cycle assessment of sustainability can be integrated throughout all stages of construction. Fundamentally, realizing the concept of sustainability necessitates the consideration of six key factors. This journey begins with the construction phase itself and the procurement of the appropriate building materials. Subsequently, a life cycle analysis is conducted on these materials, specifically examining their contribution to the circular economy and the overarching sustainable development goals [16].

Figure 2.

Life cycle assessment and sustainability [6].

- Types of Eco-friendly Paver Tiles

- (1)

- Recyclable pavers: Eco-friendly pavement is another approach to recyclable material. The advantage of this type of pavement is that it is economically less costly and environmentally sustainable. The pavement includes recycled conventional materials, such as asphalt and concrete. Although the materials are not initially sustainable, the implementation process is more environmentally friendly. This can be used for various applications, such as sidewalks, parking lots, and pavement tiles. Also, it can be used for fire lanes, recycled, and mixed in with new surfaces [7,17].

- (2)

- Permeable and porous pavers: These innovative pavers, crafted from recycled plastic grids, obviate the need for asphalt or concrete in their production, thereby reducing equipment utilization. From an economic and environmental standpoint, permeable pavers demonstrably outperform porous paver tiles, offering superior cost-effectiveness and durability, along with reduced maintenance requirements. Their versatility makes them suitable for a wide array of applications, including residential areas, light commercial zones, areas with moderate traffic, bicycle paths, and pedestrian thoroughfares [17].

The principal advantage of porous paver tiles in their superior drainage efficiency is the efficiency of the drainage system. They are also more durable in heavy-traffic applications. Furthermore, they exhibit enhanced durability in environments subject to heavy traffic. A key environmental benefit is their ability to facilitate the unimpeded flow of water and other liquids. Notably, an environmentally conscious option for porous pavements involves the use of recycled porous asphalt or concrete [17].

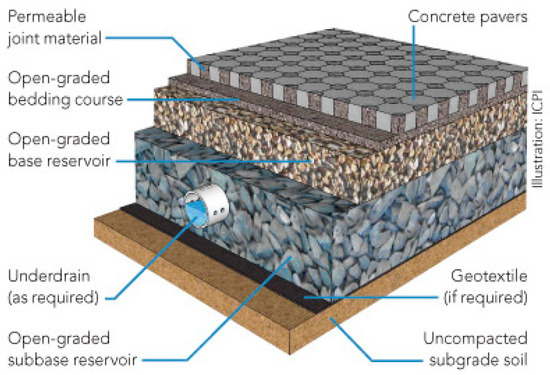

The accompanying Figure 3 elucidates permeable pavers, presenting a cross-sectional view that depicts the subterranean layers alongside their under-drainage systems. This mechanism delineates the operational principles of eco-friendly pavers when juxtaposed with conventional pavers, the latter of which typically lack these integral voids and spacing within their tile structure [7,17].

Figure 3.

Permeable pavers [17].

Since the planet has moved towards sustainability and saving renewable energy, plastics are considered to have promising potential for utilization in various aspects of the construction industry. “As shown, the energy that comes from using plastics as a primary construction material is enough to meet the average annual energy needs of 4.6 million U.S. households.” That is the equivalent of all the households in 11 out of 50 states. Plastics can be used in various applications as an ingredient in the construction industry. Each application has its properties, and the type of plastic is selected accordingly. The applications vary between interior and exterior applications. Recycled plastic can be an alternative to construction materials, such as bricks, pavement applications, structural lumber, and roofing. Also, it can be used for indoor insulation, flooring, doors, PVC windows, and ceiling tiles. Pipes for plumbing works can be made of recycled plastic, as well [7,17].

Accessible solutions offer an opportunity for developing and developed countries to accelerate towards improved economic conditions and more sustainable production methods. This transformative shift involves intensifying efforts to transition from conventional consumption patterns to those powered by renewable energy. Such a move could not only reduce emissions but also mitigate the adverse effects of resource mismanagement. Climate change, driven by these harmful emissions and other gases, is widely recognized as a global imperative. The urban heat island effect and the solar reflective index are two contributing factors to this phenomenon. Furthermore, greenhouse gases are released at every stage of the plastic production lifecycle [1,7].

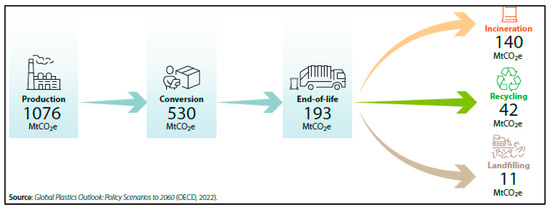

Nowadays, there are approaches to substituting fossil fuels for bio-based plastics. This change can lead to a positive output, which is a reduction in fossil fuel utilization in the production process of plastics. As a result, greenhouse gas emissions GHG will be decreased. As shown in Figure 4, plastic production is mainly made by fossil fuel-based primary plastics; bio-based plastics production is increasing, starting from 2019 and continuing to 2060. As stated, “Plastics’ production, conversion, and waste management generate about 4% of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Of these, 90% can be attributed to the production and conversion stage of the plastics lifecycle” [1]. Furthermore, a national goal of a 60% reduction in municipal solid waste (MSW) by 2030 underscores the government’s commitment to plastic recycling. This overarching target is supported by various regulations and incentives. Different industries have their own specific recycling targets for 2030. For instance, the packaging sector aims for 55% recycled materials, while building and construction also have targets for 30% recycled plastic. Although no formal legal agreement or explicit target currently exists for building and construction, this 30% figure is considered a benchmark for best practices within the industry [1,6,7,18].

Figure 4.

Carbon emissions of plastic production till end-of-life process [1].

Emittance, a surface property, quantifies its capacity to reflect solar energy, with values spanning from 0 to 1. Higher values correlate with lower emissivity. For example, a highly reflective surface might register 0.1, whereas a black nonmetallic surface could range between 0.85 and 0.95. Solar reflectivity, conversely, describes a material’s aptitude for reflecting solar energy back into the atmosphere, with values ranging from 0 to 1.0. A value of 0 signifies complete solar absorption, while 1.0 denotes total reflectance. Notably, materials prevalent in dry concrete mix design, such as cement, aggregates, and fly ash, often exhibit values that foster energy conservation, as per ASTM C 1549. Table 2 shows the solar reflectance of concrete mix design materials [1,7]. Optimal material selection favors light hues, as detailed in to ensure an excellent solar index and robust heat reflectively in roof or pavement construction.

Table 2.

Solar reflectance of construction materials [7,15].

Pervious materials, characterized by their high porosity, are instrumental in effective stormwater management, unlike imperious materials which, with their low porosity, impede water infiltration. Pervious materials are increasingly recognized as an intelligent substitute for traditional materials, finding common applications in areas such as gas stations, pavements, sidewalks, walkways, parking lots, greenhouses, rooftops, and landscape areas. Notable examples include pervious concrete, pervious asphalt, and pervious pavers. Previous pavement demonstrably mitigates excessive rainwater runoff and enhances water quality. Standardized metrics, specifically reflectance and emissivity, are employed to evaluate these paving materials, with relevant standards published by ASTM. The resulting measurement is expressed as a percentage from 0 to 100 which indicates that a value approaching 100% signifies optimal reflectivity and a minimized prosperity for heat island generation. It is important to note that this calculation is exclusively applicable for surfaces with an incline of a maximum of 9.5 degrees from the horizontal [7].

In alignment with contemporary environmental imperatives, particularly the objective of substituting virgin plastic production with recycled alternatives, Ncube and Borodin undertook a comprehensive life cycle assessment in Tomsk, Siberia, Russia. This pivotal report meticulously quantified the environmental footprint associated with HDPE waste. A subsequent tabular representation delineated the disparities in energy consumption and emissions across recycled HDPE, landfilling of incinerated waste, and virgin HDPE production. Notably, the recycling process exhibited the lowest energy requirement for treatment, 27.10 MJ, whereas the production of new materials and landfilling incurred the highest energy expenditures [1,7].

Furthermore, the greenhouse gas emissions for recycled waste were approximately 0.98 kg CO2-eq, a stark contrast to the substantial 44.65 kg CO2-eq. attributed to the landfill disposal. This underscores the profound environmental advantages of recycling and proper waste disposal over the production of new materials, also illustrating the multifaceted nature of sustainability’s influence on environmental factors, as detailed in a prior study [1,19]. Consequently, recycled plastic, specifically HDPE, represents diverse application possibilities aimed at mitigating energy consumption. The construction sector, being one of the most resource-intensive industries in terms of material consumption, stands to benefit significantly. The production of each concrete material, from its initial mix design to subsequent treatment stages, inherently imposes environmental burdens and elevates costs [1,19].

HDPE is a widely utilized thermoplastic polymer derived from petroleum and is valued as a versatile plastic material. Chemically, it is a polymer composed of numerous repeating monomer units with the formula (C2H4). A key characteristic is its relatively low degree of branching when compared to other polyethylene types. This structural difference accounts for the broad utility of its products, which include items such as plastic bottles, piping, and cutting boards. Notably, HDPE exhibits high tensile strength and an elevated melting point. It holds a significant position in the global market, accounting for over 34% of worldwide plastic consumption. As a Type 2 plastic, it is commonly employed in applications requiring thicker covers than those made from PET, such as containers for milk, shampoos, soap, motor oil, detergents, and bleach. The advantages of HDPE are well-documented and include [17,19]

- Exceptional outdoor durability as it effectively withstands extreme weather conditions.

- Efficient recyclability as it is amenable to straightforward recycling processes and applications.

- Ease of molding as its properties facilitate shaping and fabrication.

- Lightweight and robust: it offers a favorable strength-to-weight ratio.

- High chemical resistance; “HDPE plastic features a high chemical and impact resistance, in addition to being immune to rust, rotting, insects, mildew, and mold.” The stated chemical properties reflect the potential of HDPE in certain construction materials, such as outdoor applications.

- HDPE is a contributor towards achieving LEED credits. This is because HDPE is considered one of the safest recycled plastic materials for the environment. It is a totally recyclable plastic material.

The advantages of HDPE are as follows: [19]

- Affordable;

- High-quality;

- Operate at high temperatures;

- Non-leaching;

- UV resistant;

- Resistant to most chemicals;

- Stiff material;

- Amazing durability;

- Highly versatile.

HDPE’s gaps are as follows: [19]

- Poor weathering;

- Sensitive to stress cracking;

- Not resistant to chlorinated hydrocarbons;

- High thermal expansion.

The applications of HDPE are as follows: [19]

- Shampoo bottles;

- Toys;

- Flower pots;

- Chemical containers;

- Pipe systems;

- Milk jugs;

- Recycling bins;

- Grocery bags;

- Cereal box liners.

The targeted gap in this study is to utilize recycled HDPE as a substitution to the coarse aggregates in the concrete mix, which reduce the energy consumption rates in both the concrete and solid waste industries. Based on previous studies, various countries are already implementing this approach, such as India, the United States, China, the United Kingdom, and the United Arab Emirates. Although the main focus is on utilizing PET, HDPE’s advantages can achieve the standard mechanical properties of the concrete mix design for non-structural pavement applications [8]. Consequently, using recycled plastic in the concrete pavement is attainable and already applied. The key issue is in meeting the standard mechanical properties for the concrete application [8,12,13].

2. Materials and Methods

To achieve the most appropriate concrete mix design for pavements, the American Concrete Institute (ACI) standards offer helpful tables that take into account functionality and location. Table 3 outlines the standards for the concrete mix design and pavement specifications, including a water–cement ratio of 0.48 and a target strength of 30 to 35 MPa.; prior to conducting experimental work on a concrete mix design, it is important to consider certain guidelines and recommended prescriptions for fresh concrete testing [1,7,9,10,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Adhering to ACI standards, the concrete mix design intended for pavement cubes must satisfy a defined range of performance outcomes. The material specifications for concrete pavement should be outlined as follows: [17,24].

Table 3.

ASTM standards for concrete pavement [9,13,16,21,22].

- Molded concrete cubes of 0.15 × 0.15 × 0.15 m3;

- Experiments conducted at normal room temperature,

- Sieve analysis for the size of aggregates with a sieve opening size of 14 mm;

- Recommended size of shredded plastic is with sieve size of 5–6 mm.

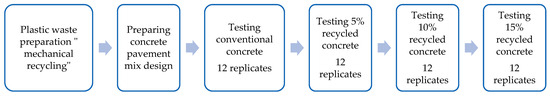

To conduct the lab experiments, specific equipment is necessary for testing and measuring the performance and properties of concrete. The process begins with cleaning and shredding plastic waste using a plastic shredding machine (Plastic shredding equipment machine, construction materials lab, AUC, Cairo, Egypt). Stage 1 displays HDPE waste prior to washing, drying, and shredding, while Stage 2 presents a similar view for HDPE waste. Stages 3, 4, and 5 showcase the steps after cleaning, washing, drying, and shredding. Once the recycled plastic is ready, all ingredients for the concrete mix are combined in a concrete mixer. The resulting mixture is then poured into wooden or metal molds and compacted on vibrators to eliminate any voids within the mix. The research development of the experimental procedure is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Research development.

2.1. Performance Measures

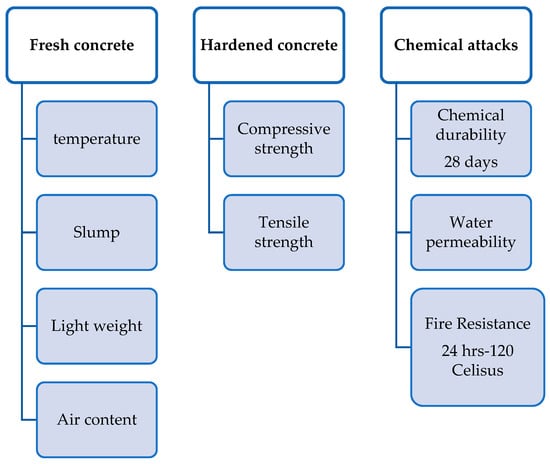

After conducting fresh concrete tests, such as temperature, slump, unit weight, and air content, the concrete cubes are placed in a curing chamber. The process of concrete mix design preparation begins with mixing all components, including the previously prepared shredded plastic. The below performance measures shown in Figure 6 are the conducted experiments for the recycled HDPE concrete pavement and the conventional concrete pavement as per the ASTM standards shown in Table 3 [16,19,21,23]. Once an appropriate mix design is achieved, the concrete is poured into the molds and compacted effectively; the concrete mix design procedure is shown in Figure 7. The cubes are then transferred to the curing room, where they remain for the required number of days to complete the curing process, before testing. The used equations are referred to in Section 2.2, to obtain the correct quantities of the concrete mix design ingredients based on ACI tables.

Figure 6.

Conducted lab experiments.

Figure 7.

Concrete mix design procedure.

2.2. Formatting of Mathematical Components [13]

Concrete mix design equations

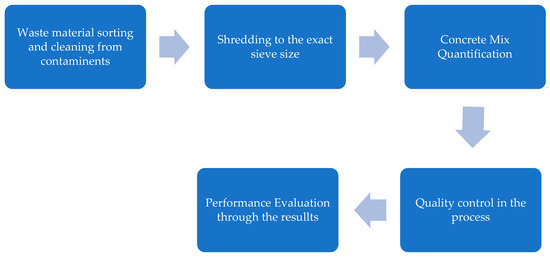

Various recycling methodologies exist for recycling plastic waste. The distinctions between these techniques are primarily determined by the type of plastic, its intended functionality, and the desired characteristics of the byproducts. Each technique is governed by its own specific parameters. After shredding the plastic waste, as shown in Figure 8, and removing all the contaminants, the recycled plastic becomes ready to be mixed with the concrete mix design. There are various types of recycling techniques, as shown in Table 4; the lowest consumed energy is achieved by the mechanical recycling technique. The mechanical recycling technique is the one used in this study [20].

Figure 8.

Waste material preparation.

Table 4.

Recycling techniques [20].

3. Results

According to American Concrete Institute standards (ACI), the concrete mix design for pavement cubes should meet a specific range of results. The materials’ specifications for concrete pavement should be within the standard range. For example, the slump test result should be between 1 and 3 cm. Table 2 shows four types of concrete mix designs that have been conducted. The first mix is the conventional concrete mix design for pavement cubes. However, the other three mixes contain recycled plastic in the concrete mix, ranging from five to fifteen recycled plastic quantities which are substituted for the coarse aggregate quantity in the mix in order to measure the best material properties by the plastic percentage in the concrete mix. As illustrated from the concrete mix design quantities used in the experiments, they are almost identical except for the coarse aggregates and the plastic percentage.

The experiments’ guidelines are as follows [13,22]:

- The temperature of the lab during the experiments is an effective factor, at 30–37 °C.

- The plastic waste preparation procedure should be accurately achieved, as depicted in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Recycled plastic waste before and after shredding.

Figure 9. Recycled plastic waste before and after shredding. - The air content test is a pressure method to measure the air content inside the concrete mix design and the unit weight, as well. This is as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Experimental work for fresh and hardened concrete.

Figure 10. Experimental work for fresh and hardened concrete. - The slump test is to measure the workability of the fresh concrete mix, to avoid air voids and weak concrete properties. This is shown in Table 2.

- The compressive strength test is to measure the concrete’s capacity to carry loads. The conventional compressive strength ranges between 2500 and 5000 psi after 28 days.

- Compressive strength results and properties are also based on the concrete functionality. The compressive strength is measured by breaking the concrete cube after 28 days. It is calculated from the load and the cross-sectional area per square meter.

- The tensile strength test determines the maximum load that a material can withstand without cracking. This measure assesses the strength of the concrete when subjected to tensile forces and its capacity to resist bending.

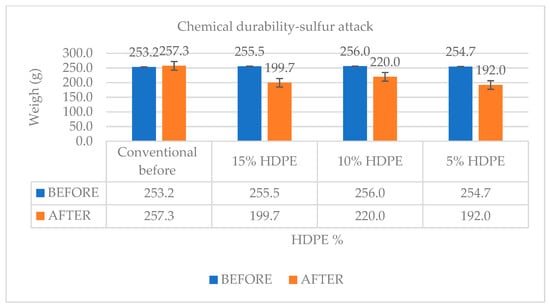

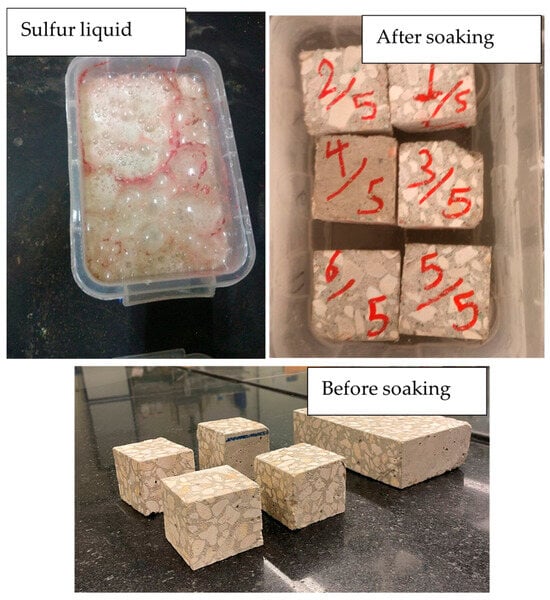

- The chemical durability test is for testing one of the limitations of HDPE. The concrete cube is divided into six pieces merged into sulfur for 28 days.

- Most of the admixture’s typical dosage ranges between 0.2 and 0.5% by weight of cement; it counts for 0.2–0.5% of the weight of the cement at a lower water–cement ratio (w/c). The type of admixture is chosen based on the weak point in the mix, such as water reducer, retarder, and accelerator, as referred to in Equation (2).

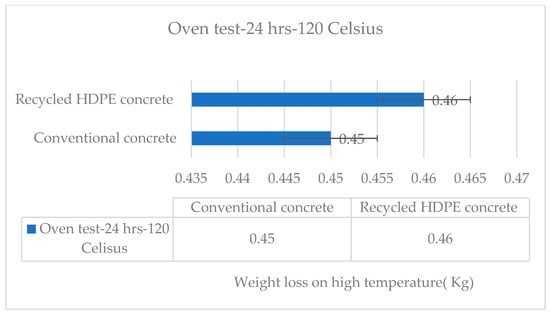

- The oven test is for 24 h at 120 °C.

Waste material preparation guidelines

The waste material preparation linear process, as shown in Figure 8, is considered a wide-ranging break down to any type of plastic waste that should be prepared before mixing with the concrete mix design. This will enhance the properties of the plastics in future applications, and it may widen the platform for using these plastics. Also, plastics are considered energy-saving materials if they pass through suitable recycling processes and the suitable shredding size, as shown in Figure 9.

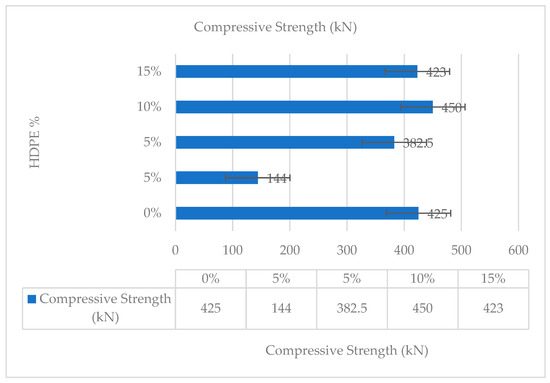

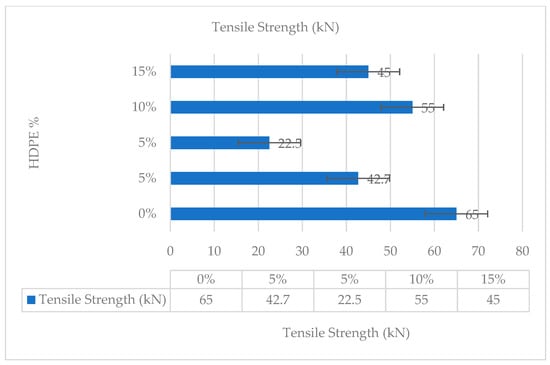

Shown in Table 5 are the results of the fresh concrete tests, such as slump, unit weight, and the air content test. This study examines Mix 1, which encompasses both the conventional mix and Mix–HDPE. Following the verification of the fresh concrete mix’s quality, compressive and tensile strength tests were conducted over a 28-day period. As depicted in Figure 10, the optimal compressive strength was achieved when recycled HDPE constituted 10% of the coarse aggregates, surpassing the performance of the conventional concrete mix, as shown in Figure 11. In terms of tensile strength, as shown in Figure 12, the best result was also observed at the 10% recycled HDPE level, as shown in Table 6, closely matching that of the conventional mix. Conversely, the 5% recycled HDPE mix exhibited failure, as shown in Figure 13. The failure was due to using different sizes of shredded plastic, which created many air voids in the mix. However, utilizing a smaller shredded plastic sieve size of 4.75 improved the results, although a 5% enhancement is still unsatisfactory.

Table 5.

Concrete mix design properties.

Figure 11.

Compressive strength for HDPE concrete mix.

Figure 12.

Tensile strength for HDPE concrete mix.

Table 6.

Compressive and tensile strength of the concrete mix design.

Figure 13.

Recycled concrete cubes with 5% to 15% of HDPE.

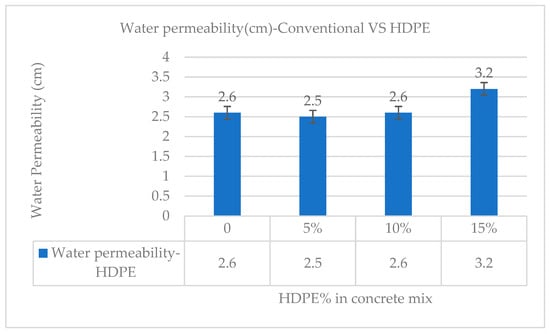

We are now progressing to the tests conducted on hardened concrete. Following the selection of the successful samples, we carried out a water permeability test to evaluate the depth of water penetration within the concrete cubes. Figure 14 demonstrates that both the conventional concrete and the HDPE-10% samples yielded satisfactory results. In Figure 15 and Figure 16, the sulfur attack test assesses the performance and durability of the recycled HDPE after the cubes have been combined and allowed to cure for 3 days. While the conventional concrete displayed moderate durability, the recycled concrete experienced a loss in weight. This suggests that stronger compaction and the incorporation of a superplasticizer may be essential to achieve adequate durability for pavement applications. As for the oven test, weight loss of the recycled HDPE is slightly higher than the conventional concrete, as shown in Figure 17. The results are the average values of the number of tested cubes.

Figure 14.

Water permeability test for recycled concrete.

Figure 15.

Chemical durability test.

Figure 16.

Chemical durability test—sulfur exposure for 28 days.

Figure 17.

Oven test for concrete cubes.

4. Discussion

The mechanical properties of recycled concrete pavement perform similarly to, or even better than, conventional concrete pavement in some trials. Additionally, recycled concrete is more cost-effective than traditional concrete mixes. This finding is supported by a cost analysis from previous research [13,19], which aligns with the principles of sustainability. As depicted, Table 7 summarizes the experimental results, highlights the limitations encountered during the experiments, and offers alternative solutions to improve the workability and performance of the concrete cubes.

Table 7.

The performance of the conducted tests and the proposed alternative solution.

During the experimental work, plastic waste preparation posed challenges, including removing contaminants, shredding, and ensuring it was ready to be added to the concrete mix. In alignment with contemporary environmental imperatives, particularly the objective of substituting virgin plastic production with recycled alternatives, Ncube and Borodin undertook a comprehensive life cycle assessment in Tomsk, Siberia, Russia [19].

Furthermore, the greenhouse gas emissions for recycled waste were approximately 0.98 kg CO2-eq, a stark contrast to the substantial 44.65 kg CO2-eq. attributed to the landfill disposal. These figures underscore the profound environmental advantages of recycling and proper waste disposal over the production of new materials, also illustrating the multifaceted nature of sustainability’s influence on environmental factors [1,19]. The construction sector, being one of the most resource-intensive industries in terms of material consumption, stands to benefit significantly. The production of each concrete material, from its initial mix design to subsequent treatment stages, inherently imposes environmental burdens and elevates costs. Therefore, integrating plastic waste into construction materials represents a viable and effective strategy for achieving sustainability benchmarks [15,19].

5. Conclusions

In summary, the contributions of the solid waste industry and the concrete industry represent a sustainable approach aimed at energy conservation within both sectors. The utilization of plastic waste, particularly HDPE, as a substitution for coarse aggregate in the concrete mix designs has demonstrated effective improvements in mechanical properties. The recycling method employed in this study is mechanical recycling, which is preferred due to its lower energy consumption throughout the process. The use of cold technology in the mechanical recycling approach contributes to energy conservation in both the concrete and solid waste industries. This method reduces reliance on landfills that depend on fossil fuels for transportation and lowers the energy required to produce new raw materials, such as coarse aggregates [20].

The results of the experimental work showed that the compressive and tensile strengths of the recycled concrete pavement tiles are superior to those of conventional concrete pavement, showing comparable or even better performance. As for the chemical durability, to mitigate sulfur attack, it is recommended to use a superplasticizer to enhance workability, while maintaining a minimal water–cement ratio. The shredding size of plastic is a major factor in enhancing the concrete mix properties and its workability. The best results are when HDPE is 10–15% of coarse aggregate. The integration of the solid waste industry with the concrete industry aligns with sustainable development goals by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and fossil fuel use. Notably, the mechanical properties of the recycled concrete are similar to, or even better than, those of conventional concrete [13].

As a result, this proposed framework is an effective strategy for energy conservation within both industries. The performance analysis indicates a potential reduction of up to 25% in carbon emissions associated with the operation of new raw materials like coarse aggregates. Additionally, the solid waste industry can achieve a reduction of 30–35% in landfill consumption through the reuse of waste materials, while the concrete industry can save up to 15% of the total coarse aggregate quantity which reduces the energy consumption of natural resources. Ongoing research in this area is crucial for identifying alternative solutions to the gaps identified during material performance testing. The potential for utilizing plastic waste in the concrete industry to lower energy consumption has not yet been explored in developing countries like Egypt, despite the abundant availability of plastic waste. An efficient waste management system is recommended to minimize energy consumption and enhance sustainability, which is a global necessity for conserving natural resources and reducing reliance on non-renewable energy [3,13].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S.; methodology, N.S.; software, N.S.; validation, M.A.; formal analysis, N.S.; investigation, N.S.; resources, N.S.; data curation, N.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S.; writing—review and editing, N.S.; visualization, N.S.; supervision, M.A.; project administration, N.S.; funding acquisition, N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HDPE | High-Density Polyethylene |

| PET | Polyethylene Terephthalate |

| LDPE | Low-Density Polyethylene |

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| ACI | American Concrete Institute |

| HDPE.0 (num) | Plastic Percentage in the Concrete Mix |

| SRI | Solar Reflective Index |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| MSW | Municipal Solid Waste |

References

- Climate Change and Plastics Pollution—OECD.ORG—OECD. Available online: www.oecd.org/environment/plastics/Policy-Highlights-Climate-change-and-plastics-pollution-Synergies-between-two-crucial-environmental-challenges.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Statista. Plastic Waste Generated by Select Countries Worldwide in 2016. 2016. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1166177/plastic-waste-generation-of-select-countries/ (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- El-Haggar, S.M. Sustainable Industrial Design and Waste Management; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 149–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marceau, M.L.; VanGeem, M.G. Solar Reflectance of Concretes for LEED Sustainable Sites Credit: Heat Island Effect; Portland Cement Association: Skokie, IL, USA, 2023; Available online: http://www2.cement.org/DVD021.02/code/reports/SN2982.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Awodiji, C.T.G.; Sule, S.; Oguguo, C.V. Comparative Study on the Strength Properties of Paving Cubes Produced from Municipal Plastic Waste. Niger. J. Technol. 2022, 40, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas & Boots. Ranked: The Countries That Produce the Most Plastic Waste; Atlas & Boots: London, UK, 2021; Available online: www.atlasandboots.com/travel-blog/which-countries-produce-the-most-plastic-waste/ (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Siddique, R.; Khatib, J.; Kaur, I. Use of recycled plastic in concrete: A review. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 1835–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, N. Utilizing plastic waste in the building and construction industry: A pathway towards the circular economy. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 383, 131311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HDPE Plastic (High Density Polyethylene)—Industrial Plastics. 2018. ASTM Standard List. Available online: https://pdfcoffee.com/astm-standard-list-pdf-free.html (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Ahmed, S.; Ali, M. Potential Applications of Different Forms of Recycled Plastics as Construction Materials—A Review. Eng. Proc. 2023, 53, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, T.R.; de Azevedo, A.R.G.; Cecchin, D.; Marvila, M.T.; Amran, M.; Fediuk, R.; Vatin, N.; Karelina, M.; Klyuev, S.; Szelag, M. Application of Plastic Wastes in Construction Materials: A Review Using the Concept of Life-Cycle Assessment in the Context of Recent Research for Future Perspectives. Materials 2021, 14, 3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammari, M.Z.J.; Sezen, H.; Castro, J. Effect of Different Plastics on Mechanical Properties of Concrete. Constr. Mater. 2025, 5, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, N.; AbouZeid, M. Recycling of Plastic Waste in the Construction Industry. Polymers 2025, 17, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The World Bank Group. Trends in Solid Waste Management. 2025. Available online: https://datatopics.worldbank.org/what-a-waste/trends_in_solid_waste_management.html (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Adesina, A. Recent advances in the concrete industry to reduce its carbon dioxide emissions. Environ. Chall. 2020, 1, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordonez-Ponce, E. Exploring the Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals on Sustainability Trends. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrick Steele June. Permeable Pavers. Farley Pavers. 2018. Available online: https://farleypavers.com/permeable-paver-installation/ (accessed on 22 May 2018).

- Ibrahim, N.A.; Abo El-Ata, G.A.; El-Hattab, M.M. Status, problems and challenges for municipal solid waste management in assiut governate. J. Environ. Stud. Res. 2020, 10, 362–384. Available online: https://journals.ekb.eg/article_136575_6b95fba57143b1ef6b51806116ae295f.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- “What Is High Density Polyethylene (HDPE)?” Xometrys RSS, Xometry. Available online: www.xometry.com/resources/materials/high-density-polyethylene-hdpe/#:~:text=High%20Density%20Polyethylene%20(HDPE%20for,a%20poly%2Dethylene%20molecular%20chain (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- Thabit, Q.; Nassour, A.; Nelles, M. Facts and Figures on Aspects of Waste Management in Middle East and North Africa Region. Waste 2023, 1, 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C936; Standard Specification for Solid Concrete Interlocking Paving Units. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM E.119; Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Building Construction and Materials. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Shaaban, I.G.; Rizzuto, J.P.; El-Nemr, A.; Bohan, L.; Ahmed, H.; Tindyebwa, H. Mechanical Properties and Air Permeability of Concrete Containing Waste Tyres Extracts. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04020472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Islam, A.; Badhon, F.F.; Imtiaz, T. Sieve Analysis. Available online: https://uta.pressbooks.pub/soilmechanics/chapter/sieve-analysis/ (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- ASTM C 143; Code for Slump Test, Case Studies in Construction Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM C 138; Code for Unit Weight Test, Case Studies in Construction Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM C231-97; Code for Air Content Test, Case Studies in Construction Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM C936; Code for Compressive Strength Test, Case Studies in Construction Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM C1371-15; Standard Test Method for Determination of Emittance of Materials Near Room Temperature Using Portable Emissometers. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM 1549-16; Standard Test Method for Determination of Solar Reflectance Near Ambient Temperature Using a Portable Solar Reflectometer. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.