Abstract

This study presents a cost-efficient Hardware-in-the-Loop platform for liquid-level process control education, designed to bridge the gap between theoretical learning and real-world industrial practice. The proposed system integrates NI myRIO and NI myDAQ hardware with LabVIEW-based real-time simulation and controller implementation, enabling flexible experimentation across a range of linear and nonlinear tank models. Through real-time controllers, students can design, tune, and validate classical digital controllers while gaining hands-on experience with real-time process dynamics. Experimental results from Model-in-the-Loop and Hardware-in-the-Loop configurations confirm the high accuracy between simulated and hardware responses, with low normalized root mean square error (NRMSE < 0.07) and high normalized cross-correlation (NCC > 0.99) between MIL and HIL responses. Additionally, learning outcomes were assessed using rubrics and student perception surveys aligned with ABET criteria. The platform successfully satisfies ABET student outcomes (SO1, SO2, SO7) by promoting modeling, system identification, and real-time implementation skills. Student surveys reveal high satisfaction mean = 5.44 and a Cronbach’s α of 0.91367, highlighting enhanced engagement, flexibility, and confidence in control system design. This work demonstrates an adaptable, scalable educational solution that strengthens engineering competencies while keeping implementation costs low.

1. Introduction

Process control is the cornerstone of industrial automation, essential across sectors such as chemical, oil and gas, paper, food, power generation, and pharmaceuticals. These industries depend on robust control systems and skilled engineers who must master both theory and the practical dynamics of processes to ensure product quality, operational safety, and energy efficiency. Process control education is indispensable in engineering curricula worldwide [1,2,3,4]. However, conventional teaching methods such as simulations and physical labs often leave gaps. Simulations lack real-world complexity, while labs are costly, hard to scale, and can be unsafe [5,6]. This gap poses a critical challenge as industry shifts towards Industry 5.0, demanding engineers adept at real-time monitoring, advanced controls, and human–machine interaction [7,8,9]. Students trained solely through basic simulations or isolated labs are often underprepared for the complex, nonlinear, multivariable processes in modern plants.

To address this issue, Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) simulation has emerged as an effective and promising approach that combines real-time process simulation with physical control hardware. HIL offers a safe, cost-efficient, and educational platform for hands-on learning and testing, bridging the gap between academic knowledge and industrial practice to help future engineers meet the demands of Industry 5.0. While HIL has become popular in engineering areas such as aerospace, electric vehicles, power electronics, robotics, and renewable energy [10,11,12,13,14], its use in control systems engineering remains limited. Most laboratory studies focus on simple processes or linear models [15,16,17]; these support the teaching of basic concepts but fall short in real-world industrial training because they do not adequately illustrate differences among systems. In contrast, many HIL platforms cannot simulate a wide range of processes, which limits their use for advanced control instruction. Consequently, students still face a gap between theory and practice. A flexible, easy, safe, and cost-effective HIL platform for process control education remains lacking, as learners need tools to study both linear and nonlinear, as well as multivariate dynamics, as observed in industry.

The primary objective of this research is to develop an HIL platform that directly enhances control engineering education by integrating theory with practical process-control systems. It focuses on creating a reconfigurable HIL framework for both linear and nonlinear process dynamics, establishing real-time closed-loop interaction between a simulated process and physical controller hardware, and enabling safe simulation of industry-relevant conditions, such as disturbances, nonlinearities, and actuator constraints.

This study aims to integrate the HIL system into the process control laboratory module to provide students with hands-on experience with classical and advanced control strategies. Another objective is to assess the platform’s effectiveness in improving learning outcomes, student engagement, and readiness for industrial applications compared with conventional teaching approaches. The study also seeks to demonstrate the platform’s cost-effectiveness and scalability, highlighting its potential for adoption across engineering institutions with varying educational requirements.

To align with these objectives, this study hypothesizes that the proposed HIL platform will outperform simulation-only and traditional laboratory approaches for studying liquid-level control in a tank process. Specifically, the HIL platform is expected to (1) provide a more realistic and flexible environment by enabling direct interaction and exposing students to real-world unpredictability, (2) significantly improve students’ performance in controller design, tuning, and troubleshooting due to more dynamic feedback, (3) enhance engagement and motivation through hands-on, industry-relevant experience in a safe environment, and (4) offer a cost-effective, scalable alternative to traditional laboratories, thus supporting widespread academic adoption.

This study aims to advance process control education by closing the gap between theory and practice. The proposed HIL platform allows students to work with realistic process dynamics. This deepens their understanding and improves problem-solving abilities. The platform supports instruction in both classical and advanced control methods. It provides a safe and adaptable environment. For the industry, it helps prepare future engineers to manage complex, nonlinear, and multivariable processes. Key sectors include the chemical, petrochemical, energy, and manufacturing industries. The HIL platform offers hands-on experience in real-time control and system optimization. This helps produce graduates who are ready for industry challenges. The platform is also cost-effective and scalable. These features make it a practical solution for universities with limited resources, expanding access to quality process control education worldwide.

Although similar HIL implementations exist in prior work, these studies typically emphasize technical realization without reporting Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET) aligned learning impact or demonstrating a complete pedagogical workflow. This work differentiates itself by offering an integrated instructional workflow connecting (1) modeling, (2) Model-in-the-Loop (MIL) simulation, (3) real-time HIL execution, (4) fidelity assessment, and (5) ABET outcome evaluation. While it does not advance methodological knowledge in control engineering, it contributes by demonstrating how such experimental frameworks translate into measurable improvements in learning.

Although low-cost microcontroller-based or NI-based HIL platforms exist in the literature, they tend to emphasize technical prototyping rather than linking implementation with ABET frameworks or systematic educational assessment. Thus, the novelty of this work lies in integrating multi-geometry HIL capability with outcome-based evaluation in a single platform—filling a gap in instructional design rather than advancing control methodology.

This study focuses on the design and implementation of an HIL platform for undergraduate liquid-level control, primarily using tank process models. While the platform can be adapted to other nonlinear processes, such as heat exchangers and distillation towers, its main emphasis is on integrating classical digital controllers and cascade control methods in a laboratory setting. The platform was evaluated through student experiments that assessed learning outcomes, engagement, and practical skills. However, this study has several limitations. The HIL platform is intended for small- to medium-sized process dynamics and does not simulate all industrial processes. Evaluation was limited to a controlled academic environment with a small student group, which may not represent broader industrial or classroom contexts. The platform prioritizes educational and approximate real-time applications over complete industrial robustness. Implementation may also require specialized hardware, which could limit accessibility for institutions with fewer resources.

This study examines whether a cost-efficient HIL platform integrating LabVIEW 2021 32bit, NI myRIO-1900, and NI myDAQ can effectively support student learning in modeling and PI/PID controller implementation for multi-tank processes, while preserving real-time behavior consistent with Model-in-the-Loop simulations. Although conceptually simple, PI/PID controllers remain central to control engineering education and industrial practice, providing an essential foundation for understanding more advanced control methodologies.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work in process control and the use of HIL in education. Section 3 describes the HIL Laboratory environment. Section 4 covers system design and implementation. Section 5 discusses students’ experimental results. Section 6 assesses learning outcomes. Section 7 provides a detailed discussion of the results Finally, Section 8 presents the conclusions.

2. Literature Review

HIL has been used in industry for a long time, but the high cost and complexity of the required equipment limit its use in education. For example, in the field of power electronics, electric vehicle technology, motors and drives, renewable energy, etc., there are widely known similar HIL software such as OPAL-RT®, Typhoon®, and dSPACE® (https://www.opal-rt.com/, https://www.typhoon-hil.com/, and https://www.dspace.com/en/pub/home.cfm) [18,19,20], which provide high efficiency in design and testing, suitable for practical applications in industries that require high reliability. However, most of the software focuses specifically on mechanical, power electronics, and electrical work. In addition, the cost of software and hardware is very high. Therefore, it is unsuitable for teaching laboratory subjects in universities that require sufficient experimental sets for students. However, in recent years, many researchers have focused on the use of HIL in engineering across various fields, including control systems engineering.

Recently, a group of researchers has focused on using low-cost hardware to build HIL systems for control system studies, including modeling and simulation, controller design, and communication [21,22,23]. It has been shown that a Raspberry Pi-based HIL simulator is a low-cost, effective solution for supplementing control engineering instruction. Students will practice designing and testing controllers using systems that closely mimic real-world conditions. This clearly connects theoretical knowledge to practice. However, using a Raspberry Pi can be less deterministic than specialized RTOS devices, which may affect simulations requiring high timing accuracy. Furthermore, I/O limitations and scalability may be insufficient to simulate systems that need many channels or high-resolution signals. Additionally, using a Raspberry Pi requires programming skills in Linux and Python https://www.linux.org/pages/download/ and https://www.python.org/downloads/ (accessed on 15 November 2025), which may necessitate more practice time for students without prior experience with text-based programming.

While [24] has taken it a step further by applying Digital Twin with an HIL system to teaching control engineering, using a low-cost and straightforward simulation model to align with the curriculum and enhance students’ practical understanding, utilizing a PLC as a real controller in the process to provide students with hands-on experience in control. However, the Digital Twin model realistically and visually simulates cocoa production, but does not provide mathematical validation of the virtual model against the real system. Although this work effectively connects PLC to Unity 3D via IoT, it lacks real-time, deterministic HIL testing that emphasizes time response (latency, jitter) and dynamic closed-loop simulation, which are core to HIL in industry. The evaluation focused solely on student accuracy and running time, but it included no standardized, in-depth learning-outcome indicators.

The authors of [25] developed a learning and testing framework for control systems that integrates MIL and HIL using inexpensive yet efficient BeagleBone hardware for teaching real-world process control. The focus is on understanding closed-loop control circuits, from mathematical modeling to controller design. Based on a smooth model-based design process, as in [20,21,22], the use of microcontrollers requires a basic knowledge of text-based programming languages, which makes the experiments complex, difficult to understand, and potentially confusing. Moreover, it can lead to student boredom, reducing confidence in future controller design. Unfortunately, it has not been measured how much using MIL and HIL improves students’ learning or understanding.

The literature review concludes that significant research gaps exist. First, most research focuses on applying HIL to low-cost controllers. This limitation is constrained by the flexibility and simulation capabilities of various HIL platforms, making it infeasible to scale to future, high-complexity systems. This is not cost-effective for designing laboratories for sustainable control systems. Second, most HIL-related research utilizes microprocessors, microcontrollers, and Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs), creating barriers in text-based programming languages. This problem becomes even more significant and complex when systems are integrated. Third, HIL systems developed from an educational perspective lack an evaluation framework grounded in engineering outcomes for assessing student satisfaction and learning. A comparative summary of related studies is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of comparative research on related research.

We propose a novel process-control laboratory that addresses the challenges mentioned earlier. The platform provides substantial support for improving process-control education in hands-on environments. Students can begin the learning process by engaging in hands-on activities with a secure, fully interactive, and customizable platform. It is possible to revolutionize classroom control by supporting the latest trends in HIL adoption. Instructors can create a variety of process simulations and control systems to engage with students rapidly. Once students have piqued their interest, they can discuss theoretical, physical, and mathematical concepts related to the topic. Finally, students are encouraged to integrate their designed control algorithms with real-time hardware to validate the real controller for a virtual tank process. With this HIL platform, students can complete controller and tank process designs much more quickly, which led to the concept of rapid control prototyping (RCP). Students can also use the same HIL hardware and software tools to extend their studies in other engineering processes and complete final undergraduate projects. The customizable rapid prototyping platform aligns with the ABET student outcome requirements for SO1, SO2, and SO7. Specifically, SO1 is demonstrated through the modeling and system identification of dynamic processes, enabling students to identify, formulate, and solve complex control engineering problems using experimental data and mathematical analysis. SO2 is achieved through the systematic design, tuning, and implementation of digital controllers that satisfy defined performance specifications, thereby strengthening students’ ability to apply engineering design principles to practical control problems. SO7 is reinforced through experiential learning and real-time experimentation with emerging hardware and software tools, fostering students’ capacity to acquire and apply new knowledge independently [26]. Overall, the proposed platform cultivates essential competencies that prepare undergraduate students for professional careers in control system design, instrumentation, motor control, semiconductor systems, and related engineering domains. In addition to control systems, students can directly access real-time processing units using the high-level graphical language LabVIEW. New students can implement a control system for a tank process even with minimal LabVIEW training, without prior knowledge of a text-based programming language such as Python, Java, VHDL, Verilog, C, C#, or C++.

The key contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- A reconfigurable low-cost HIL platform is developed for liquid-level process education, enabling real-time interaction between simulated plant dynamics and physical controller hardware.

- (2)

- The framework integrates MIL and HIL execution within the same environment, streamlining rapid controller prototyping and validation using NI myRIO, myDAQ, and LabVIEW.

- (3)

- Four representative tank geometries—vertical cylindrical, horizontal cylindrical, spherical, and conical—are implemented to allow progressive exposure to linear and nonlinear process behaviors.

- (4)

- Quantitative validation is provided through NRMSE and NCC metrics, demonstrating high consistency between MIL and HIL responses and supporting claims of simulation fidelity.

- (5)

- The laboratory methodology is aligned with ABET SO1, SO2, and SO7 educational outcomes, with student performance metrics and satisfaction surveys confirming effectiveness.

- (6)

- The platform is scalable for future integration of advanced controllers such as fuzzy-PI, Model Predictive Control (MPC), and optimization-based tuning, highlighting opportunities for research extension.

- (7)

- Compared with existing HIL educational setups, the proposed platform emphasizes a balance among cost-efficiency, deterministic execution, user accessibility, and ease of implementation.

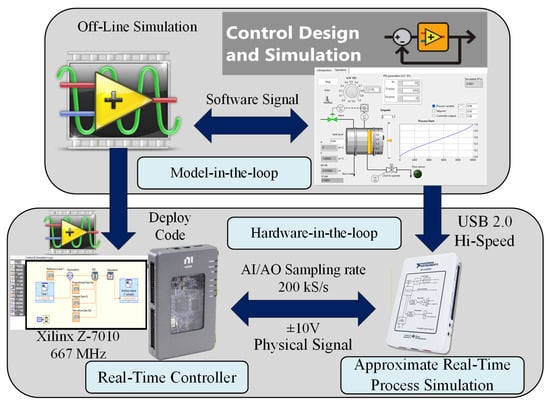

Therefore, the author conceived the idea of creating a process control laboratory that combines the advantages of computer simulation and hardware testing at a cost-effective price. This laboratory would provide students with hands-on hardware experience while also allowing them to benefit from software simulation. First, students will simulate various tank processes using the open-loop method to study their system behavior. Second, students will simulate the process using MIL to develop a LabVIEW controller and a tank process using the Control Design and Simulation Toolkit (CDST). Utilizing this simulation, students can verify and test the behavior of the tank process and controller with adjustable parameters. Once the tank process and controller produce satisfactory results in software simulation, students can implement the designed controller on the myRIO module using the same LabVIEW code. The input/output connections between the controller and the tank process are also made via the myDAQ module for experimental measurement. The proposed educational laboratory setup, shown in Figure 1, reduces time and provides flexibility for designing efficient control algorithms applicable to real-time (RT) targets. Additionally, this laboratory setup can be reused for future complex simulations with many variables.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed HIL platform.

3. Environment of HIL Laboratory

HIL process control labs enable students to simulate and experiment with industrial control systems, deepening theoretical understanding. Accurate, real-time simulations closely replicate real processes and offer more realistic results than offline simulations. HIL labs also reduce maintenance time and costs compared to traditional process control labs. National Instruments (NI) is a leading provider of real-time simulation tools, offering FPGAs integrated with Xilinx for low-latency, parallel processing. The LabVIEW FPGA module enables users to program FPGAs using graphical blocks, thereby eliminating the need for specialized HDL or Verilog expertise. This lab uses the cost-effective myRIO module, which supports both LabVIEW Real-Time and FPGA functionality, making it accessible for students. The myDAQ module provides portable, high-resolution data logging and measurement, with analog and digital I/O for process experimentation. LabVIEW is used to efficiently configure the myRIO controller and simulate processes on the myDAQ module [27,28,29].

In this laboratory setup, shown in Figure 2, a real-time controller is connected to a virtual process running on a simulator. A liquid-level controller is developed using a real-time controller and integrated with the virtual process via HIL techniques, using NI hardware and LabVIEW software. This approach allows students to test and customize controllers without physical tanks or equipment, reducing the risk of hardware damage. Experiments can be conducted safely and repeatedly, even under conditions that are not easily replicated in real-world processes. The setup enables students to design controllers and simulate tank processes, with the myDAQ module handling simulation and Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) display, and the myRIO module managing controller design and HMI display. Communication between modules is achieved via voltage-limited wiring within specified requirements.

Figure 2.

Environment of the HIL laboratory setup for process control system.

4. Mathematical Modeling of Tank Process

In this paper, four examples are presented to demonstrate how students can use the HIL laboratory facility with a single control. This reflects the design of an external controller in a closed loop. As a learning outcome of this exercise, students gain hands-on experience implementing closed-loop control for various types of tanks under varying parameter conditions.

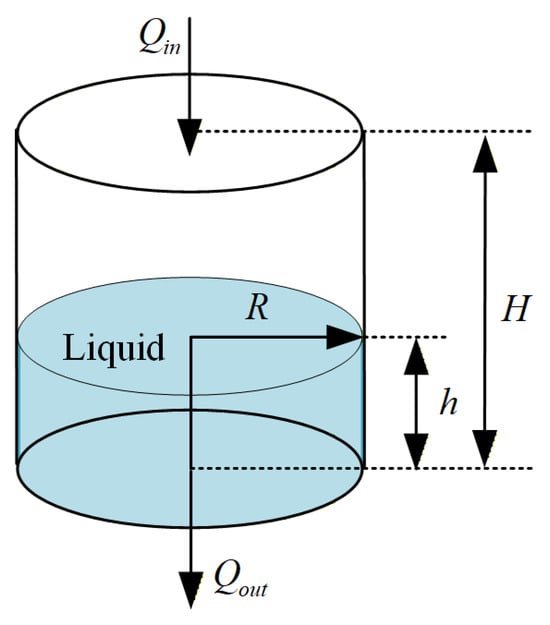

4.1. Vertical Cylindrical Tank [30,31,32]

Figure 3 shows a vertical cylindrical tank, commonly used to study liquid-level control in process industries. The tank has a uniform cross-sectional area. Water inflow (Qin) and outflow (Qout) set the liquid height (h). Tank radius (R) and height (H) are defined to derive the mathematical relationship between flow and level. This setup forms the basis for the dynamic model and control implementation.

Figure 3.

Vertical cylindrical tank structure.

The liquid-level dynamics in a vertical cylindrical tank can be derived from the continuity equation in conjunction with Torricelli’s law. The mass balance of the tank is expressed as

where V denotes the liquid volume (m3), Qin is the inflow rate (m3/s), and Qout is the outflow rate (m3/s). For a vertical cylindrical tank with a constant cross-sectional area A = πR2, the liquid volume is given by

Differentiating vertical volume with respect to time yields

Assuming an orifice located at the bottom of the tank, the outflow rate is modeled using Torricelli’s law as

where Cd is the discharge coefficient, Ao is the orifice area (m2), and g denotes the gravitational acceleration (m/s2).

Substituting the vertical chain rule and vertical outflow into the vertical mass balance, the nonlinear differential equation governing the liquid level dynamics is obtained as

It is noted that the system’s nonlinearity arises solely from the square-root outflow term. In contrast, the constant cross-sectional area yields a relatively simple level dynamics compared with non-uniform tank geometries.

Figure 4a shows the implementation of the mathematical model of the vertical cylindrical tank using differential equations based on the parameters in Table 2. The scaling was intentionally selected to produce slow process dynamics suitable for educational demonstrations, controller-tuning exercises, and HIL experimentation, rather than to replicate a specific physical installation. The level dynamics are computed from the inflow-outflow relationships derived from the tank geometry and the orifice equation. These model equations are embedded in the LabVIEW environment to enable real-time computation of the water level. Figure 4b presents the developed SCADA interface for monitoring and controlling the tank process, allowing users to visualize process variables such as level, valve status, and pump flow. Integrating the mathematical model and SCADA interface enables simulation and control experiments under real operating conditions.

Figure 4.

Simulation of VCT: (a) differential equation; (b) SCADA of vertical cylindrical tank process.

Table 2.

Vertical cylindrical tank model parameter.

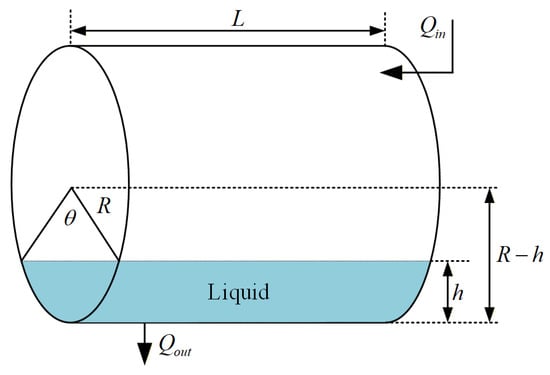

4.2. Horizontal Cylindrical Tank [33,34,35]

Figure 5 shows a horizontal cylindrical tank with a cross-sectional area that varies nonlinearly with the liquid height h. The tank has a radius R and a length L, which affect the dynamics of the fluid level. Inflow Qin and outflow Qout drive transient behavior as liquid volume changes. This structure is used to analyze nonlinear level dynamics and validate control performance under varying flow conditions.

Figure 5.

Horizontal cylindrical tank structure.

The liquid volume in a horizontal cylindrical tank of radius R and length L, as a function of liquid level h, is given by

where A(h) denotes the wetted cross-sectional area of the liquid. The cross-sectional area A(h) of the liquid is expressed as

Since the liquid volume is a function of the level h, the rate of change in volume can be obtained using the chain rule as

This formulation explicitly links the mass balance to the level dynamics through the geometry-dependent term dV/dh.

Differentiating volume with respect to h yields

The derivative of the cross-sectional area with respect to the liquid level is given by

Applying mass balance to the tank yields

The outflow is modeled using the orifice equation as

Substituting the chain rule outflow into the mass balance, the nonlinear level dynamics of the horizontal cylindrical tank are obtained as

It is noted that the system nonlinearity arises primarily from the geometry-dependent term dA(h)/dh and the square-root outflow relationship, which makes the horizontal cylindrical tank a suitable benchmark for nonlinear process control studies.

Table 3 lists the principal parameters for modeling the horizontal cylindrical tank (HCT) system, specifying geometric, physical, and hydraulic constants. The scaling was intentionally selected to produce slow process dynamics suitable for educational demonstrations, controller-tuning exercises, and HIL experimentation, rather than to replicate a specific physical installation. These parameters support the mathematical model and numerical simulation. Figure 6a shows the differential equations executed in LabVIEW to describe the tank level’s dynamic behavior. Figure 6b shows the developed SCADA interface for process monitoring and control, with manual and automatic modes. Together, these figures detail the modeling and implementation workflow for real-time simulation of the HCT process.

Table 3.

Horizontal cylindrical tank model parameter.

Figure 6.

Simulation of HCT: (a) differential equation; (b) SCADA of horizontal cylindrical tank process.

4.3. Spherical Tank [36,37,38]

Figure 7 illustrates the geometry of the spherical tank, highlighting its highly nonlinear relationship between liquid height and volume. The figure provides a visual reference for the challenging benchmark in level control created by the variable cross-sectional area. This visual context supports analysis of system dynamics and controller performance under nonlinear conditions.

Figure 7.

Spherical tank structure.

For a spherical tank of radius R, the volume of liquid as a function of the liquid level h is given by

Since the liquid volume is a function of the fluid level h, the rate of change in volume can be obtained using the chain rule as

Differentiating: spherical volume with respect to h yields

Substituting dV/dh spherical into the spherical chain rule, the volume dynamics become

Applying mass balance to the spherical tank gives

The outflow rate is modeled using the orifice equation as

Substituting dV/dt spherical–spherical outflow into spherical mass balance, the nonlinear level dynamics of the spherical tanks are obtained as

It is observed that the nonlinearity of the spherical tank arises from both the geometry-dependent cross-sectional area and the square-root outflow term, making this system a representative benchmark for nonlinear level-control studies.

Table 4 summarizes the key parameters used to model the spherical tank, including geometric (e.g., tank diameter and height) and hydraulic (e.g., flow rate and liquid level) characteristics required for dynamic analysis. The scaling was intentionally selected to produce slow process dynamics suitable for educational demonstrations, controller-tuning exercises, and HIL experimentation, rather than to replicate a specific physical installation. Figure 8a shows the differential equations implemented in LabVIEW, a graphical programming environment. These equations describe the nonlinear behavior of the liquid level. Figure 8b shows the SCADA interface for monitoring and control of the spherical tank system. Together, these elements illustrate the integration of mathematical modeling and real-time simulation within the educational control platform.

Table 4.

Spherical tank model parameter.

Figure 8.

Simulation of ST: (a) differential equation (b); SCADA for a spherical tank process.

4.4. Conical Tank [39,40,41]

The conical tank serves as a standard for evaluating advanced control algorithms and reveals key characteristics of the nonlinear dynamics of process systems. As illustrated in Figure 9, the geometry features a cross-sectional area that varies with height. This inherent nonlinearity complicates precise regulation of the liquid level, particularly under variable inflow conditions.

Figure 9.

Conical tank structure.

For a conical tank with base radius R and total height H, the volume of liquid at level h is expressed as

Due to geometric similarity between the liquid cone and the whole tank geometry, the radius of the fluid surface at height h is given by

Substituting the conical radius into the conical volume basic, the liquid volume as a function of the level h becomes

Differentiating conical volume with respect to time yields

The derivative of the liquid volume with respect to the level is given by

Substituting dV/dh conical into the conical chain rule, the volume dynamics become

Applying the mass balance to the conical tank yields

The outflow rate is modeled using Torricelli’s law as

Substituting dV/dt conical by conical outflow into conical mass balance, the nonlinear level dynamics of the conical tank are obtained as

It is observed that the conical tank exhibits strong nonlinear behavior due to the quadratic dependence of the effective cross-sectional area on the liquid level, which makes it more challenging to control compared to uniform-geometry tanks.

The conical tank parameters used in the simulation are summarized in Table 5, which specifies the system’s geometric and physical characteristics. The scaling was intentionally selected to produce slow process dynamics suitable for educational demonstrations, controller-tuning exercises, and HIL experimentation, rather than to replicate a specific physical installation. Figure 10a shows the implementation of the mathematical model in LabVIEW, a visual programming environment for data acquisition and control. The model uses differential equations to model the tank’s fluid dynamics, outflow, and water-level changes. The relationships between the cross-sectional area and water height are computed from Equations (3), (13) and (15), ensuring real-time level updates within specified limits. Figure 10b presents the SCADA interface, process monitoring, and control. This configuration enables real-time visualization of the conical tank response and allows evaluation of control performance under various operating conditions.

Table 5.

Conical tank model parameter.

Figure 10.

Simulation of CT: (a) differential equation; (b) SCADA of conical tank process.

In Figure 11, a pyramid automation ANSI/ISA-95 or IEC-62264 (ANSI/ISA-95.00.01; Enterprise–Control System Integration—Part 1: Models and Terminology. International Society of Automation (ISA): Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2010. IEC 62264-1; Enterprise–Control System Integration—Part 1: Models and Terminology.). International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.) is an international standard developed by the International Society of Automation (ISA) for separating the HIL experimental configuration between the controller and the simulated plant process. At the SCADA level, the engineering and operations station uses programming and HMI monitoring, and the process simulation station uses mathematical modeling to communicate with the NI myDAQ module via a USB cable linking it to the NI myRIO module. At the Control level, the myRIO module serves as the real-world controller, executing LabVIEW-developed control algorithms, including PID control. At the Field level, the myDAQ module bridges the simulated and physical domains by converting mathematical process model outputs into analog signals and receiving control inputs from real-world hardware. The myRIO and myDAQ modules are linked by physical wires that carry real electrical signals (typically in the ±10 V range). This step of the control loop:

Figure 11.

A proposed automation pyramid for development and simulation setup is presented.

- The user sets parameters and reference values (setpoints) through the HMI on the development computer and transfers them to the myRIO module.

- The myRIO module executes the control algorithm and outputs a control signal via analog output to the myDAQ module input.

- The simulation computer receives the control signal through the myDAQ module, updates the plant model response, and generates the simulated process variable.

- The myDAQ module outputs this simulated process variable as a voltage signal back to the myRIO module input.

- The myRIO module reads this feedback signal, processes it in the next control cycle, and the loop repeats.

Figure 12 illustrates the proposed HIL platform developed for real-time control of the tank process. The architecture is divided into two main sections: the Real-Time Controller and the Approximate Real-Time Simulation. The upper section employs the NI myRIO device as the controller. It implements the PID algorithm with embedded signal filtering and saturation functions. These features ensure stability and prevent actuator overdrive. The setpoint signal SP(s) is compared to the measured process variable P(s) to produce error signal E(s), which drives the control output MV(s). Analog interfaces (±10 V) enable communication between the controller and process simulation.

Figure 12.

Block diagram of the proposed HIL platform.

In the lower section, the NI myDAQ module serves as the data-acquisition and process-simulation unit. It executes the mathematical model of the conical tank in approximate real-time. The control signal from myRIO is converted into a simulated pump voltage Vpum(s). The resulting tank level h(s) is then fed back as an analog signal to close the control loop. This configuration allows realistic emulation of nonlinear tank dynamics. It also maintains flexibility for parameter tuning and fault injection. The overall system enables rapid testing, validation, and optimization of control algorithms before hardware deployment in real plant environments.

5. Results

5.1. Open-Loop Test with Outlet Valve Closed

Accurate differential equations are essential for representing process behavior in the HIL platform, especially during open-loop tests with a closed outlet. These tests prevent water loss and help determine system linearity. Measuring dh/dt with Qin allows precise calculation of the tank’s cross-sectional area or sensor calibration. Figure 13 illustrates changes in tank response time and behavior, using a simulation resolution of 0.01 s. Pump rates from 20% to 100% generate the responses shown in Figure 13a–d. Linear behavior is observed with constant inflow, while nonlinear transitions occur in circular tanks at varying water levels. The conical tank exhibits pronounced nonlinearity at the apex due to a higher height-to-area ratio.

Figure 13.

Time response of tank process with open loop test: (a) Vertical Cylindrical Tank, (b) Horizontal Cylindrical Tank, (c) Spherical Tank, and (d) Conical Tank.

5.2. Open-Loop Test with Outlet Valve Opened

In the open-loop test, opening the outlet valve reveals First-Order plus Dead-Time (FOPDT) behavior. Understanding FOPDT behavior is crucial for controller design. FOPDT is a practical approximation commonly used to model the dynamic behavior of industrial processes. The FOPDT model equation is simple, with three main parameters. The static gain K represents the ratio of the steady-state change. The time constant τ shows how quickly the system responds. The dead time L marks the initial delay before the process starts to respond, as shown in Figure 14. This approximation is handy for designing and tuning PID controllers. It efficiently captures important process features, such as exponential responses and delays, which are common in process control engineering. Step response analysis was used to determine K, τ, and L. Static gain (K) is the ratio of the input change to the steady-state output; τ is the time to reach 63.2% of the response; and Ld is the delay before the process responds. These parameters ensure model validity and simplify controller design.

Figure 14.

Parameters for FOPDT.

For all open-loop experiments, the pump was set to 100%. Figure 15a–d confirm that the FOPDT model can approximate tank processes, simplifying initial PID controller design. Due to minimal dead time, IMC-PI and fine-tuning methods were employed to adjust the PI control parameters. These methods balance speed and robustness via the parameter λ: larger values yield slower, more stable responses, whereas smaller values increase speed but may cause oscillations [42,43]. FOPDT parameters were analyzed, and controller gains Kp and Ki were calculated as shown in Table 6.

Figure 15.

Time response of tank process with open loop loop MIL and HIL test: (a) Vertical Cylindrical Tank, (b) Horizontal Cylindrical Tank, (c) Spherical Tank, and (d) Conical Tank.

Table 6.

Parameters of FOPDT in each tank process and parameters of control.

And the parameters of the PID controller obtained from the IMC-PI method are calculated as follows:

To evaluate the consistency of the process model response during MIL and HIL testing, we quantitatively assessed it using the Normalized Root Mean Squared Error (NRMSE) and Normalized Cross-Correlation (NCC), defined as follows:

Figure 15a–d and Table 7 summarize the calculated NRMSE and NCC values. For four tank types, NRMSE values range from 0.01 to 0.07, indicating very low error and high model accuracy. All models achieved NCCs above 0.99, indicating excellent waveform similarity and dynamic consistency with real signals. All models are rated “Very Good” in amplitude and waveform matching. This demonstrates robust model performance and accurate system identification. Therefore, these models are well suited to controller design, dynamic prediction, and the validation of process control systems.

Table 7.

NRMSE and NCC of the open-loop test.

5.3. Closed-Loop Test with MIL and HIL

Closed-loop control experiments were performed in both MIL and HIL configurations at a rotation speed of 0.01 s. The objective was to limit time-overshoot to less than 10% of the steady state and achieve a 5% steady state time within 200 s, as shown in Figure 16. Each tank type required specific Kp and Ki values for PI controller tuning, with reference liquid levels set at 5 m for vertical cylindrical and circular tanks, 2.5 m for the horizontal cylindrical tank, and 1.5 m for the conical tank. The IMC-PI method and subsequent fine-tuning were used to analyze the relationship between the controller gain and the time-overshoot response. All experiments were conducted without system delay. Controller settings for each experiment were: Figure 16a VCT, Kp = 1, Ki = 0.8; Figure 16b HCT, Kp = 2, Ki = 4.22; Figure 16c ST, Kp = 1.014, Ki = 0.744; Figure 16d CT, Kp = 4, Ki = 5.93.

Figure 16.

Time response of tank process with closed loop MIL and HIL test: (a) Vertical Cylindrical Tank, (b) Horizontal Cylindrical Tank, (c) Spherical Tank, and (d) Conical Tank.

Overall, both the MIL and the HIL precisely tracked their setpoint, with settling times of less than 200 s and overshoots of less than 10%. Specifically, for the vertical cylindrical tank (VCT), the overshoot was 6.2% before returning to 5 m, with the HIL providing a slightly smoother profile. Moving to the horizontal cylindrical tank (HCT), the MIL had a rise time of 36.5 s and a 6.1% overshoot from SP = 2.5 m, while the HIL settled slightly faster and more stably. Regarding the spherical tank (ST), the highest overshoot was 8.9%, accompanied by a slight dip before convergence; the HIL reduced both overshoot and vibration. Finally, the conical tank (CT) exhibited the quickest response and minimal overshoot, with settling times of approximately 80.2 s for the MIL and 70.63 s for the HIL. The time-response characteristics are summarized in Table 8, and the calculated NRMSE and NCC values are presented in Table 9.

Table 8.

Comparison of the specification time response between MIL and HIL.

Table 9.

NRMSE and NCC of the closed-loop test.

Table 10 presents the estimated hardware costs for the proposed HIL laboratory setup, totaling US$2215.27. This amount covers essential equipment, including two Dell Latitude 3550 notebooks, a National Instruments myRIO-1900 controller board, and a myDAQ data acquisition unit, which together form a cost-effective yet powerful platform for real-time control and data acquisition experiments in educational environments.

Table 10.

The hardware cost of the HIL laboratory is proposed.

6. Assessment of Learning Outcomes

System and Control Engineering is a required course in the Instrumentation and Automation Engineering undergraduate program at King Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok (KMUTNB), with 18 students enrolled in the 1/2025 semester. The group of 18 participants reflects the full enrollment in the core control laboratory course, which serves as the institutional cohort for ABET outcome assessment; therefore, this group represents the course population rather than a subsample. The proposed HIL platform was used in the laboratory, enabling students to design and implement control processes for various tank systems. The curriculum included four key modules, see Table 11. The effectiveness of the HIL platform was assessed through a student satisfaction survey.

Table 11.

Teaching Objectives & ABET SO Mapping.

The assessment was conducted by assigning a group of our 3rd- and 4th-year undergraduate students in the Instrumentation and Automation Engineering program to a practical placement in the Systems and Control Engineering course during the 2025 academic year. The study included 18 students, with an age range of 20–22 years, and a gender distribution of male (72.3%) and female (27.7%). This rubric Table 12 aligns with ABET SO1, emphasizing students’ ability to identify, formulate, and solve engineering problems through modeling and system identification. It systematically evaluates competencies from problem definition through model validation and interpretation. The criteria ensure that learners demonstrate analytical rigor, experimental accuracy, and engineering judgment—key elements for mastering real-world control system design and analysis. This rubric Table 13 reflects ABET SO2, emphasizing the design, tuning, implementation, and analysis of control systems. It evaluates students’ ability to define control objectives, apply proper tuning techniques, implement controllers in LabVIEW, and interpret system responses. The assessment ensures that learners can integrate theoretical design with real-time testing while accounting for performance limitations and safety constraints in controller implementation.

Table 12.

Rubric of SO1 about modeling & system identification.

Table 13.

Rubric of SO2 about the controller design & implementation.

Table 14 presents the students’ performance evaluations for ABET SO1 and SO2, highlighting the achievement of learning outcomes in modeling, system identification, and controller design. Most students achieved an average score above 3.0, indicating satisfactory attainment of both outcomes. This result confirms the effectiveness of the HIL-based learning approach in enhancing students’ analytical, design, and implementation competencies.

Table 14.

Score table for SO1 and SO2.

To evaluate learning outcomes, student perception, and satisfaction with the HIL Laboratory, an eight-question survey was administered via Google Forms, as shown in Table 15. The survey assessed various benefits, including increased motivation, improved theoretical understanding, reduced design time, greater agility, greater flexibility, and greater applicability. A modified 6-point Likert scale was used to avoid neutral responses and better capture participants’ opinions. The scale included the following designations: “Strongly Agree” (STL), “Agree” (A), “Slightly Agree” (SLA), “Strongly Disagree” (STD), “Disagree” (D), and “Slightly Disagree” (STD). The survey statements were aligned with the laboratory’s learning outcomes and objectives.

Table 15.

Eight questions for students about the lab and its effectiveness.

Table 15 summarizes students’ feedback on the HIL Process Control Laboratory, indicating high satisfaction across all evaluated aspects, with mean scores ranging from approximately 5.2 to 5.6. The results suggest that students effectively linked theoretical knowledge with real-time experimentation, appreciated the flexibility and safety provided by the HIL setup, and developed greater confidence in both controller design and implementation. Figure 17 illustrates the students’ responses to the HIL laboratory survey, showing that most participants either strongly agreed or agreed with all eight statements. These outcomes affirm the pedagogical effectiveness of the HIL platform in supporting the ABET SO1, SO2, and SO7 competencies.

Figure 17.

Results of the questions Q1 to Q8 survey taken by students involved in the HIL lab activity.

7. Discussion

The experimental and pedagogical findings of this study highlight the dual contributions of the proposed HIL platform: technical performance and educational impact. From a control engineering perspective, both MIL and HIL experiments demonstrated strong correspondence in transient and steady-state responses. Quantitatively, NCC values above 0.99 and NRMSE values below 0.07 confirmed the system’s high accuracy and real-time fidelity, validating its ability to replicate real process dynamics across multiple tank geometries. These results verify that integrating NI myRIO and myDAQ with LabVIEW provides a sufficiently deterministic real-time environment for evaluating and tuning classical controllers.

In terms of system behavior, the nonlinearities observed in spherical and conical tanks provided an effective benchmark for students to analyze the performance of IMC-PI–based control, including overshoot, rise time, and steady-state error. The closed-loop experiments confirmed that all four tank processes achieved less than 10% overshoot and settling times of less than 200 s, satisfying the design criteria for stability and performance. The ability to rapidly modify controller parameters via the RCP workflow reduced development time and enabled immediate visual feedback via SCADA and HMI interfaces, reinforcing theoretical learning through practical validation.

In practice, loop jitter, sensor noise, sampling-rate effects, and actuator limits influence dynamic response and HIL fidelity. These considerations are now highlighted to motivate future extensions to robustness and uncertainty testing. Tank parameters were intentionally scaled to yield observable dynamic behavior within 0–5 V interface limits consistent with the LabVIEW-NI setup. While NI myRIO enables deterministic execution, it presents constraints in channel count, network variable latency, and scalability for multi-loop systems.

Extending this analysis to educational outcomes, ABET SO1 (problem solving), SO2 (engineering design), and SO7 (acquiring new knowledge) mappings indicate that the HIL platform develops key skills in system modeling, control design, and independent learning. Rubric-based assessments found over 85% of students scored above 3.0, indicating strong achievement in system identification and controller implementation. To provide interpretive context, our program defines SO1 and SO2 as “attained” when the cohort average ≥ 3.0. In this cohort, 15 of 18 students exceeded this threshold, and the mean score was 3.27, indicating successful attainment of program expectations. The three students below the threshold were either late enrollees or missing assignment submissions, reinforcing that continuous engagement and task completion are critical determinants of successful learning outcomes. The eighth-question Likert-scale survey, with a mean of 5.44 on a 6-point scale, showed high satisfaction with the platform’s flexibility, safety, and industrial relevance. Furthermore, the eight-item perception survey achieved a Cronbach’s α of 0.91367, indicating strong internal consistency by educational research standards. This demonstrates that the assessment is a reliable measure. The results suggest that platform structure has a significant and statistically validated effect on student understanding. To clarify outcome alignment, Q1–Q2 primarily assess the theory–practice connection (SO1), Q3–Q4 evaluate students’ ability to adapt to new tools (SO7), and Q5–Q8 reflect confidence and performance in real-time controller design and implementation (SO2). This is consistent with the students’ report: students’ greater confidence in connecting models to real-time control hardware supports outcome-based education goals.

After reviewing the reflection notes and post-lab discussions, two main learning points emerged. Initially, many students believed that the First Order Plus Dead Time (FOPDT) model could be applied to all tank types. By using HIL simulations to compare round and cone-shaped tanks in both upright and inverted configurations, students observed where the FOPDT model fails. They noted how different tank shapes affect the extent of system deviation from the target and the settling time. They also observed that when the system does not behave as expected, it causes tuning problems that do not appear in MIL simulations. These results indicate the need to tune the system multiple times and to adhere to safety rules in real-world settings.

Compared with Raspberry Pi HIL, PLC-based digital twin implementations, and MATLAB/FPGA prototyping, the proposed platform offers a balanced trade-off among deterministic timing, programming accessibility, and ABET-aligned outcome measurement.

In broader pedagogical terms, the proposed HIL system promotes experiential and adaptive learning by enabling real-time experimentation in a safe and reconfigurable environment. It bridges the gap between simulation-based training and industrial-grade systems, addressing key Industry 5.0 competencies, including cyber-physical integration, human–machine interaction, and sustainability in engineering education. The low-cost structure (~US$2215) further supports scalable implementation across academic institutions, particularly in developing regions, without compromising functionality or learning depth.

Although the present study focuses on PI/PID control, the platform architecture is designed to readily support fuzzy-PI, gain scheduling, MPC, and metaheuristic tuning without modifying the core HIL structure.

In summary, this work does not claim theoretical control innovation but instead proposes a novel approach to teaching control systems in an outcome-verified, ABET-aligned manner.

8. Conclusions

This research developed and validated an HIL platform for liquid-level process control education. It integrates simulation and experimentation into a single environment. The system lets undergraduate students design, implement, and evaluate PI/PID controllers using LabVIEW, NI myRIO, and myDAQ, providing real-time learning akin to industrial practice. Experimental results from four tank setups—vertical, horizontal, spherical, and conical—showed accurate modeling, stable closed-loop control, and high consistency between MIL and HIL results (NCC > 0.99).

The low modeling error (NRMSE < 0.07) and strong correlation (NCC > 0.99), together with SO1/SO2 attainment scores exceeding the institutional threshold 3.0, corroborate both the MIL–HIL fidelity and the educational effectiveness claimed in this work.

In terms of educational outcomes, the HIL laboratory fulfilled ABET SO1, SO2, and SO7 by enhancing students’ ability to model dynamic systems, design digital controllers, and perform real-time experimentation. Additionally, survey results confirmed high levels of student satisfaction, reflecting increased confidence, understanding, and engagement with control theory and practice. Beyond the reported technical and educational results, the novelty of this work lies in integrating a multi-geometric HIL process-control architecture with ABET-aligned learning assessment and cost-effectiveness analysis within a single, reusable, and extensible platform.

From a control engineering standpoint, the proposed HIL system offers a realistic, reconfigurable, and safe platform for studying nonlinear dynamics, FOPDT modeling, and evaluating controller performance. Its cost-effective architecture (≈ US$2215) and modular design support scalable implementation across academic institutions. Future work will extend this platform to advanced control strategies such as fuzzy-PI, cascade, and MPC, and integrate it with Digital Twin frameworks to further improve real-time fidelity and industrial relevance.

In summary, this study explicitly links HIL implementation to measurable learning outcomes rather than to purely technical innovation. While PI and PID control constitute the primary pedagogical focus, the proposed HIL architecture is deliberately structured to accommodate advanced control strategies, including fuzzy PID, gain scheduling, and model predictive control, without requiring modifications to the underlying hardware or data exchange mechanisms. As a result, the platform establishes a robust foundation for future extensions, including fuzzy PI, cascade control, optimization-based intelligent control, and real-time Digital Twin integration. Furthermore, it enables the concurrent evaluation of technical performance and educational effectiveness within a unified experimental environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and W.K.; methodology, S.M.; software, S.M.; validation, S.M., W.K. and T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, T.S. and W.W.; visualization, S.M., N.T.-U. and T.S.; supervision, W.W. and N.T.-U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our sincere thanks to the faculty of engineering, our staff, and students within the Department of Instrumentation and Electrical Energy Engineering, Advanced Control and Intelligent Systems Laboratory (ACISLab) at the Prachinburi campus, and the Center of Excellence on Instrumentation Technology and Automation (CEITA) at King Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok, Thailand.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Acronyms | |

| ABET | Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology |

| DAQ | Data Acquisition |

| FPGA | Field Programmable Gate Array |

| HCT | Horizontal Cylindrical Tank |

| HIL | Hardware-in-the-Loop |

| HMI | Human–Machine Interface |

| IMC | Internal Model Control |

| LabVIEW | Laboratory Virtual Instrument Engineering Workbench |

| MIL | Model-in-the-loop |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| MV | Manipulated Variable |

| NCC | Normalized Cross-Correlation |

| NRMSE | Normalized Root Mean Square Error |

| NI | National Instruments |

| PID | Proportional-Integral-Derivative |

| PV | Process Variable |

| RCP | Rapid Control Prototyping |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| SO | Student Outcome |

| SP | Setpoint |

| ST | Spherical Tank |

| VCT | Vertical Cylindrical Tank |

| Abbreviations | |

| λ | Time constant of IMC (s) |

| τ | Time constant (s) |

| A | Cross-section (m2) |

| CT | Conical tank |

| FOPDT | First Order Plus Dead Time |

| InAE | Instrumentation and Automation Engineering |

| V | Volume (m3) |

| KMUTNB | King Mongkut University of Technology North Bangkok |

| L | Length (m) |

| Q | Flow Rate (m3/s) |

| R | Radius (m) |

| RT | Real Time |

| Subscripts | |

| i | Integral |

| in | Inflow |

| out | Outflow |

| p | Proportional |

| pump | Water pump |

| o | Orifice |

| d | Delay |

References

- Kong, Z.Y.; Omar, A.A.; Lau, S.L.; Sunarso, J. Introducing process simulation as an alternative to laboratory session in undergraduate chemical engineering thermodynamics course: A case study from Sunway University Malaysia. Digit. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, D.L.; Prempeh, G.O. Making a chemical process control course an Inductive and deductive learning experience. Chem. Eng. Educ. 2010, 44, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, L.F.; Brandao, D.; Oliveira, M.A. A multi-process pilot plant as a didactical tool for the teaching of industrial processes control in electrical engineering course. Int. J. Electr. Eng. Educ. 2019, 56, 62–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, B.; Woods, P.C. Virtual Laboratories in Engineering Education: The Simulation Lab and Remote Lab. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2009, 17, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroso, L.; Batista, P. Reproducible low-cost flexible quadruple-tank process experimental setup for control educators, practitioners, and researchers. J. Process Control 2022, 118, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalič, F.; Truntič, M.; Hren, A. Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulations: A Historical Overview of Engineering Challenges. Electronics 2022, 11, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagcang, H.; Stobart, R.; Steffen, T. A review of component-in-the-loop: Cyber-physical experiments for rapid system development and integration. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2022, 14, 16878132221109969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Nolasco, J.; Sámano-Ortega, V.; Rodriguez Estrada, H.; Santoyo-Mora, M.; Rodriguez-Segura, E.; Zavala Villalpando, J. Controller Hardware in the Loop Platform for Evaluating Current-Sharing and Hot-Swap in Microgrids. Energies 2024, 17, 3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazrat, M.A.; Hassan, N.M.S.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Rasul, M.G.; Taylor, B.A. Developing a Skilled Workforce for Future Industry Demand: The Potential of Digital Twin-Based Teaching and Learning Practices in Engineering Education. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balla, M.; Haffner, O.; Kucera, E.; Cigánek, J. Educational Case Studies: Creating a Digital Twin of the Production Line in TIA Portal, Unity, and Game4Automation Framework. Sensors 2023, 23, 4977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardana, I.; Ho, C.N.M.; Zhang, Y. A Comprehensive Study and Validation of a Power-HIL Testbed for Evaluating Grid-Connected EV Chargers. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2022, 10, 2395–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamo, P.; de Castro, A.; Sanchez, A.; Ruiz, G.A.; Azcondo, F.J.; Pigazo, A. Hardware-in-the-Loop and Digital Control Techniques Applied to Single-Phase PFC Converters. Electronics 2021, 10, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisoy, A.; Sen, D.K. A Hardware-in-the-Loop Simulation Case Study of High-Order Sliding Mode Control for a Flexible-Link Robotic Arm. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, V.S.; Medina, A.P.; Sanchez, M.B.; Segura, E.R.; Garibay, A.J.; Nolasco, J.M. Hardware in the Loop Platform for Testing Photovoltaic System Control. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangkalajan, S.; Koodtalang, W.; Sangsuwan, T.; Pudchuen, N. Virtual Process Using LabVIEW in Combination with Modbus TCP for Fieldbus Control System. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering (ICCSCE) 2019, Penang, Malaysia, 29 November–1 December 2019; pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangkalajan, S.; Koodtalang, W.; Sangsuwan, T.; Deelertpaiboon, C.; Jirasereeamornkul, K. The Design of PI + Approximation 2 Degree of Freedom Cascade Controller for Vertical Coupled Liquid Tank System. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 29 November–1 December 2022; pp. 885–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, J.A. Modernising the Control Curriculum and Delivery to Meet 21st Century Needs. Processes 2025, 13, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karad, S.G.; Thakur, R.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Khan, M.J.; Malik, H.; Márquez, F.P.G.; Hossaini, M.A. Optimal Design of Fractional Order Vector Controller Using Hardware-in-Loop (HIL) and Opal RT for Wind Energy System. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 35033–35047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.; Sunjury, M.S.A.A.; Ashraf, A.; Meraj, M.; Tricoli, P. Fault-Tolerant Operation of Photovoltaic Systems Using Quasi-Z-Source Boost Converters: A Hardware-in-the-Loop Validation with Typhoon HIL. Electronics 2025, 14, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalón, A.; Muñoz, C.; Muñoz, J.; Rivera, M. A Detailed dSPACE-Based Implementation of Modulated Model Predictive Control for AC Microgrids. Sensors 2023, 23, 6288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobota, J.; Goubej, M.; Königsmarková, J.; Čech, M. Raspberry Pi-based HIL simulators for control education. In Proceedings of the 12th IFAC Symposium on Advances in Control Education ACE 2019, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 7–9 July 2019; pp. 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, M.; Goubej, M.; Sobota, J.; Visioli, A. Model-based system engineering in control education using HIL simulators. IFAC Pap. 2020, 53, 17302–17307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čech, M.; Vosahlo, M. Digital Twins and HIL Simulators in Control Education—Industrial Perspective. In Proceedings of the 13th IFAC Symposium on Dynamics and Control of Process Systems, Busan, Republic of Korea, 14–17 June 2022; pp. 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, J.S.; Quishpe, E.K.; Sailema, G.X.; Guamán, N.S. Digital Twin-Based Active Learning for Industrial Process Control and Supervision in Industry 4.0. Sensors 2025, 25, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Farias, A.B.D.; Rodrigues, R.S.; Murilo, A.; Lopes, R.V.; Avila, S. Low-Cost Hardware-in-the-Loop Platform for Embedded Control Strategies Simulation. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 111499–111512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.abet.org/accreditation/accreditation-criteria/criteria-for-accrediting-engineering-programs-2025-2026/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Souza, I.D.T.; Silva, S.N.; Teles, R.M.; Fernandes, M.A.C. Platform for Real-Time Simulation of Dynamic Systems and Hardware-in-the-Loop for Control Algorithms. Sensors 2014, 14, 19176–19199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordi, F.; Barnard, C.; Fortier, P.; Miled, A. FPGA-Based Hardware-in-the-Loop Real-Time Simulation Implementation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 66th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 6–9 August 2023; pp. 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.N.; Goldbarg, M.A.S.d.S.; Silva, L.M.D.d.; Fernandes, M.A.C. Real-Time Simulator for Dynamic Systems on FPGA. Electronics 2024, 13, 4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlabac, T.; Antic, S.; Calasan, M.; Milovanovic, A.; Marvucic, N. Nonlinear Tank-Level Control Using Dahlin Algorithm Design and PID Control. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H. A Water Tank Level Control System with Time Lag Using CGSA and Nonlinear Switch Decoration. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2023, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, X. Inverse Tangent Functional Nonlinear Feedback Control and Its Application to Water Tank Level Control. Processes 2020, 8, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, S.A.; Mohamed, A.I.M.; Ali, E.A.; Nawari, M.O. Level Control of Horizontal Cylindrical Tank. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Computer, Control, Electrical, and Electronics Engineering, Khartoum, Sudan, 21–23 September 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elumalai, G.K.; Ponnusamy, V. An improvement of level control of non-linear horizontal tank process using sliding mode controller. Chem. Prod. Process Model. 2025, 20, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Hu, H.; Lin, H.; Chen, L.; Wan, Y.; Xiao, T.; Peng, Y. Research on Capacity Measurement Method of Horizontal Cylindrical Tank Based on Monte Carlo Method. Chem. Technol. Fuels Oils 2022, 58, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrea, C.; Garcia-Garcia, Y. Design and Performance Analysis of Level Control Strategies in a Nonlinear Spherical Tank. Processes 2023, 11, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwini, A.; Sriram, S.R.; Joel, L.A. Quadruple spherical tank systems with automatic level control applications using fuzzy deep neural sliding mode FOPID controller. J. Eng. Res. 2025, 13, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegatheesh, A.; Kumar, C.A. Novel fuzzy fractional order PID controller for a nonlinear interacting coupled spherical tank system for level process. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2020, 72, 102948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaluisa, K.; Vargas, L.; Llanos, J.; Velasco, P. Model Predictive Control for Level Control of a Conical Tank. Processes 2024, 12, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrea, C.; Páez, F. Design and Comparison of Strategies for Level Control in a Nonlinear Tank. Processes 2021, 9, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govind, K.R.A.; Mahapatra, S. Frequency Domain Specifications Based Robust Decentralized PI/PID Control Algorithm for Benchmark Variable Area Coupled Tank Systems. Sensors 2022, 22, 9165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, T.-Y.; Jung, B.-G. A Study of PI Controller Tuning Methods Using the Internal Model Control Guide for a Ship Central Cooling System as a Multi-Input, Single-Output System. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, D.C.; Castrillón, F.; Vásquez, R.E.; Smith, C. PID Tuning Method Based on IMC for Inverse-Response Second-Order Plus Dead Time Processes. Processes 2020, 8, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.