Abstract

In this paper, coal samples from multiple regions on the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin in the North China Craton were selected as the subject of study. All the samples are selected based on their ash content. Then, micropore volume and heterogeneity of the pore size distribution of deep coal seams are studied by using low-temperature liquid nitrogen and high-pressure methane adsorption experiments. Then the factors influencing methane adsorption capacity as constrained by ash content are studied. The results are as follows: (1) The coal samples can be divided into two categories based on ash content: high-ash and medium-to-low-ash. The micropore structure distribution curve for medium-to-low-ash coal exhibited a four-peak distribution, and that of high-ash coal also showed a four-peak distribution. (2) Micropore volume and heterogeneity of micropore distribution are controlled by thermal evolution. Conversely, for high-ash coal, the micropore volume and heterogeneity are constrained by ash content; the micropore volume decreases and heterogeneity increases with rising ash content. (3) The methane adsorption capacity of medium-to-low-ash coal was higher than that of high-ash coal. A critical pore size range of 0.3~0.6 nm for controlling methane adsorption was found. Within this range, an increase in pore size distribution heterogeneity leads to a decrease in adsorption capacity.

1. Introduction

It is noted that the production ratio between adsorbed gas and free gas methane directly results in uncertainties in the production behavior of deep CBM [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Moreover, under the constraints of great burial depth, whether the adsorption pore characteristics of deep coal reservoirs differ from those of shallow coal seams remains an open question. Such differences may cause marked variations in production patterns between deep and shallow CBM reservoirs [14,15,16,17]. Therefore, it is necessary to characterize the adsorption pores of deep coals, particularly the development features of micropore volumes, in order to elucidate the pore–fracture system of deep CBM reservoirs. This would provide theoretical guidance for the subsequent exploration and development of deep CBM.

On this basis, a study on the pore–fracture structures of deep coal seams has been discussed. Taking No. 8 coal of the Benxi Formation at the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin as a case study, researchers preliminarily investigated the development characteristics of its pore–fracture system. The results show that the primary pore–fracture structures of No. 8 coal are dominated by small pores (<100 nm), with a pore volume proportion exceeding 85% [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Meanwhile, to achieve a quantitative description of the heterogeneity of pore and fracture structures in deep coal seams, fractal theory is used to quantitatively characterize the complexity of pore structures. This theory achieves a quantitative description of pore and fracture structures in deep coal reservoirs and can be used for a refined description of deep coal seams.

It should be noted that due to the thinness of coal seam 8, the degree of thermal evolution within the same coal seam does not change significantly, resulting in a weaker impact of thermal maturity on the pore fracture system of the same coal seam. By contrast, coal maceral composition plays a more significant role, especially ash content, which becomes the main factor controlling pore–fracture development [25,26]. In addition, some scholars have begun to apply nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques to investigate the pore–fracture system of coal reservoirs and the microscopic distribution of water within them. The results indicate that in deep coal seams, water mainly exists in the forms of free water, bound water, and capillary water, while methane occurs mainly in adsorbed and free states [12,19].

Above all, although research has begun to address the pore–fracture structures of deep coal seams, several issues remain unresolved. First, the controlling factors for adsorption pores in deep coal seams—particularly micropore volume development—require further investigation. Second, as the Benxi Formation at the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin represents the core breakthrough zone for deep CBM in China, the adsorption characteristics constrained by micropore structures in its deep coal seams need clarification.

In this paper, coal samples of No. 8 coal from Block X of the Benxi Formation in the eastern Ordos Basin were collected. Based on the coal quality of the selected samples, the samples are classified by using ash content. On this basis, the distribution characteristics of micropore (<2 nm) volumes in samples with different ash contents are discussed. Furthermore, the heterogeneity of micropore volume distribution is quantitatively characterized using single-scale and multi-scale analysis theories. Meanwhile, high-temperature and high-pressure methane adsorption experiments are comprehensively applied to quantitatively characterize the adsorption properties of coal samples, thereby exploring the adsorption behavior of methane as constrained by micropore volume and heterogeneity in deep coal reservoirs.

2. Sample Collection and Experimental Methods

2.1. Geological Setting and Sampling Collection

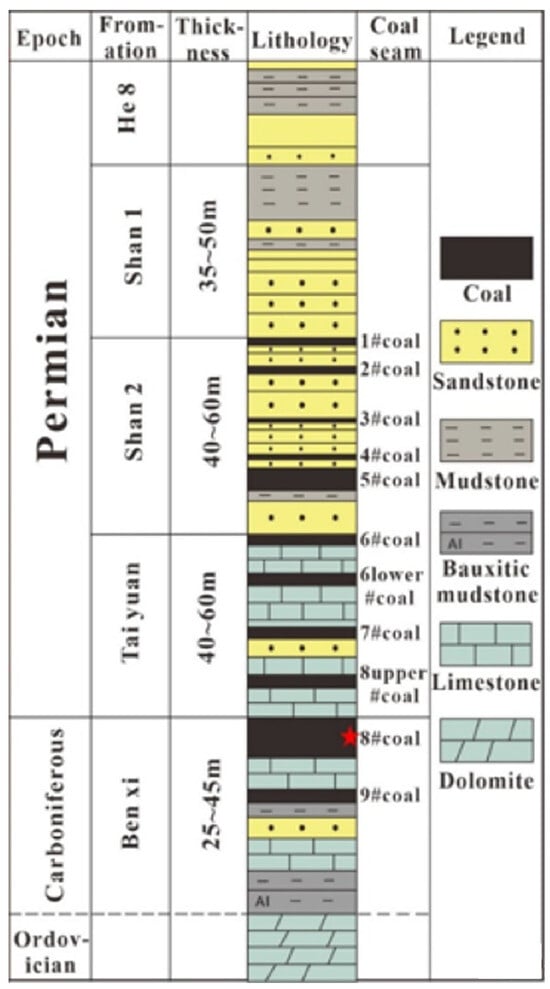

The Ordos Basin is situated at the western margin of the North China Craton, and the topography generally exhibits a planar distribution characterized by “a relatively broad and gentle eastern basin, a steep and narrow western basin, and asymmetry between the southern and northern parts of the basin”. Influenced by Caledonian tectonic movements, the Ordos Basin underwent overall subsidence during the Late Carboniferous Benxi Formation deposition period. It began receiving sediments and developed a series of marine–terrestrial interbedded deposits. The Benxi Formation is known for its well-preserved marine invertebrate fossils (including conodonts, foraminifera, ammonoids, rugose corals, and brachiopods), as well as plant fossils such as ferns and seed ferns. Gymnosperms have also arisen at this time. With the expansion of land area, land plants invaded continental settings from coastal regions, forming large-scale forests and swamps, which provided the prerequisite conditions for coal formation. The study area is situated in the central-eastern part of the Ordos Basin, bordered by the Yimeng Uplift to the north, the Weibei Uplift to the south, the Tianhuan Depression to the west, and the Jinxi Fold Belt to the east. The overall tectonic setting is stable, which belongs to a gently dipping monocline trend that is NNE-trending and NW-trending. There are few faults and fractures within the area. The Paleozoic coal-bearing strata in the study area mainly include the Carboniferous Benxi formation, the Permian Taiyuan formation, and the Permian Shanxi formation [27,28]. Among these, the target coal seam—Benxi formation coal seam 8—is widely distributed throughout the study area. Its burial depth ranges from 1800 to 4000 m. The roof consists of interbedded limestone and mudstone, while the floor comprises bauxitic mudstone (Figure 1). The coal thickness varies from 3 to 10 m, with some sections exceeding 15 m. Overall, it exhibits a distribution characterized by “greater thickness in the north and lesser thickness in the south”. This coal seam exhibits stable development, with locally developed gangue intercalations, well-developed pore and fracture networks, and pronounced heterogeneity [29,30].

Figure 1.

Comprehensive stratigraphic column chart of the study area.

2.2. Experimental Methods and Fractal Models

2.2.1. Experimental Methods

Low-Temperature Carbon Dioxide Adsorption Test (LTCO2 GA)

Upon collection, the samples were immediately sealed with plastic film and promptly transported to the laboratory in strict compliance with the Chinese National Standard GB/T 19222-2003 [31] for preliminary preparation and pretreatment. Low-temperature CO2 adsorption experiments were conducted following the Chinese National Standard GB/T 21650.2-2008 [32]. Representative sample portions weighing between 2 and 5 g were crushed and sieved to a particle size range of 40–60 mesh (0.25–0.42 mm). Prior to the study, the samples were subjected to degassing and drying at a constant temperature of 273.15 K (0 °C) to thoroughly remove surface-adsorbed impurities.

The CO2 adsorption–desorption behavior was measured using an ASAP 2460 fully automated surface area and porosity analyzer. During the experiment, the relative pressure (P/P0) was controlled within the range of 0–0.1, with an equilibrium time of 10 s allotted for each pressure point. Based on the obtained CO2 adsorption isotherms, the microporous structure was inversely modeled and quantitatively characterized by applying the Density Functional Theory (DFT) method. Pore volume and pore size distribution characteristics within the range of pores smaller than 2 nm were derived. The primary objective of this experiment was to characterize the microporous structure of the samples [33,34]. Before conducting low-temperature CO2 adsorption tests, all samples were degassed in a vacuum degassing device at 110 °C for 12 h to ensure surface cleanliness and avoid the influence of impurities adsorbed in the early stage on the experimental results.

High Temperature and High Pressure Isothermal Adsorption Test (HTHP)

The isothermal adsorption experiments presented in this study were conducted using a KT100-40HT high-pressure isothermal adsorption apparatus. All experimental procedures were strictly performed in accordance with the Chinese National Standards GB/T 19559-2008 [35] and GB/T 19560-2008 [36]. Prior to formal testing, all coal samples were subjected to a 12 h drying and vacuum degassing treatment in a drying oven to thoroughly remove inherent moisture and pre-adsorbed gases. To ensure the leak-tightness of the experimental system, high-purity helium gas (He, purity ≥ 99.99%) was employed for leakage detection [37,38]. During the measurement process, the measured samples were tested 2–3 times, and the isothermal adsorption curve was obtained by taking the average value.

2.2.2. Calculation of the Fractal Dimension

The fractal dimension of the specific surface area of coal serves as a key parameter for characterizing the complexity and heterogeneity of its pore surfaces. Based on fractal theory, a specific surface area fractal model can be established under the assumption that the pore structure exhibits fractal characteristics. It is assumed that a power-law relationship exists between the specific surface area S and the pore diameter r. By applying a logarithmic transformation to the experimental data, the following relationship can be derived [39]:

where S is the specific surface area, m2/g; r is the pore diameter, nm; E is a constant term that is related to the properties of the material itself; and C is the slope, which is a dimensionless power exponent.

From this, the calculation formula for the fractal dimension Ds of the specific surface area can be obtained [39]:

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Coal Quality

Core observation results indicate that the selected samples are mostly gray or dark gray and columnar or short columnar, and the primary structural coal is well developed. The coal exhibits a glassy luster, and the macroscopic coal rock type is dominated by semi-bright or semi-dark coal, which also demonstrates the strong heterogeneity characteristics of the macroscopic coal rock type in the deep CBM of this area. Typical samples were selected for microscopic observation. In the selected samples, the content of the vitrinite group ranged from 43.69% to 88.27%, the content of the exinite group ranged from 0% to 20.35%, and the inertinite group content ranged from 11.17% to 56.34%. The microscopic components are dominated by the vitrinite group, indicating that the coal formation process mainly occurred in a reducing environment. Meanwhile, the industrial composition indicates that Mad ranged from 0.4% to 0.89%, with an average of 0.57%; Aad ranged from 7.33% to 55.99%, with an average of 28.35%; Vdaf content ranged from 7.64% to 21.59%, with an average of 11.09%; and FCdaf content ranged from 39.49% to 82.74%, with an average of 64.52% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic information of coal samples.

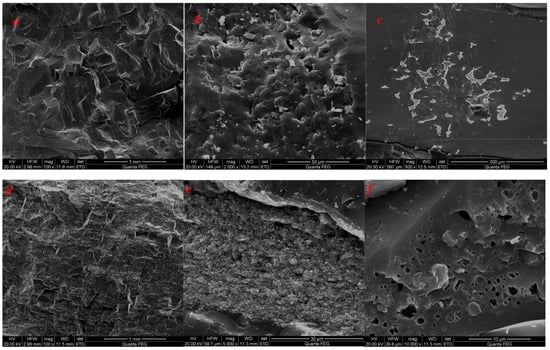

By scanning electron microscopy (SEM), as shown in Figure 2, a large number of pores and microcracks are observed in the samples. The pores include cavity pores, inorganic pores, and organic matter pores. Among them, organic matter pores are dominant, and micro-nano pores are developed within the organic matter pores. Relevant studies indicate that this type of pore is the main storage space for micropores, which further demonstrates the important role of micropores in deep CBM.

Figure 2.

Well Q85: (a) Coal, mainly consisting of vitrinite, with short fractures; (b) structural vitrinite, with deformed lacuna structures, filling, and mineral content (clay-rich); (c) deposits on bedding planes or other interfaces, primarily iron sulfide; Well b15: (d) overview, mainly vitrinite, homogeneous vitrinite develops static pressure fractures, layering visible, dense; (e) clay-rich, mainly kaolinite; (f) dense development of micro-nano pores.

In summary, there are significant differences in micro-components and industrial components of the selected coal samples, while little variation was found in the vitrinite reflectance (Ro). Therefore, to discuss the impact of Aad on the micropore structure, all samples were divided into two types based on Aad = 20%. Type A mainly consists of medium-to-low Aad coal samples, while Type B mainly consists of high Aad coal samples. The subsequent discussion will be based on this two-type classification.

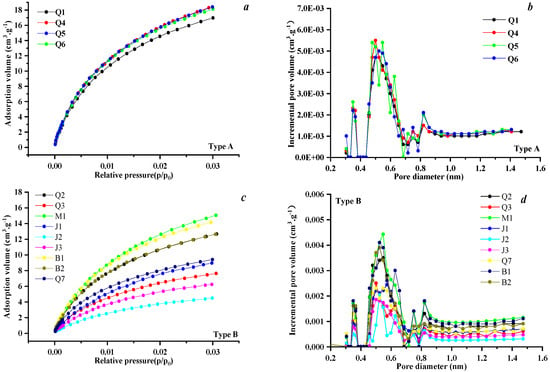

3.2. Effect of Coal Facies and Coal Quality on Micro-Pore Distribution Heterogeneity

Based on low-temperature CO2 adsorption curves, the micropore distribution of the selected samples are analyzed (Figure 3). As shown in Figure 3a, the maximum CO2 adsorption capacity of Type A samples ranges from 14.04 to 16.97 cm3/g, with an average of 14.98 cm3/g. Figure 3b reveals that the micropore distribution curve of this type displays a “four-peak” profile, with distinct peaks located at 0.3 nm, 0.35 nm, 0.5 nm, and 0.85 nm, indicating a complex and heterogeneous micropore structure.

Figure 3.

Carbon dioxide adsorption curves and pore size distribution of different coal facies. (a) Type A carbon dioxide adsorption curve; (b) Pore size distribution of type A; (c) Type B carbon dioxide adsorption curve; (d) Pore size distribution of type B.

In contrast to Type A, there is a significant variation in maximum CO2 adsorption capacity of Type B samples, which ranges from 10.53 to 12.66 cm3/g and averages 11.67 cm3/g—lower than that of Type A. The micropore distribution curve displays a “three-peak” profile, with peaks at 0.35 nm, 0.55 nm, and 0.75 nm. Overall, the pore structure heterogeneity is more pronounced in Type A.

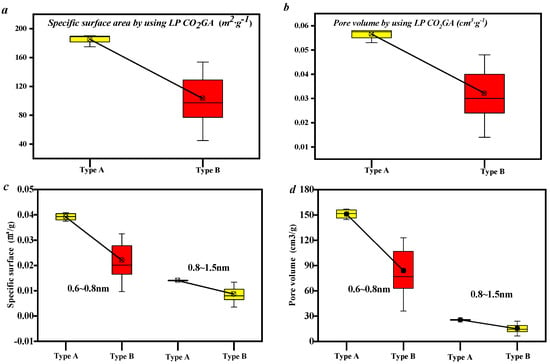

Based on this, the differences in pore volume and specific surface area of different types of micropores are compared. Figure 4a shows that the pore-specific surface area (PSSA) of Type A is 174.80~190.19 m2/g, with an average value of 185.61 m2/g, while the PSSA of Type B is 44.86~153.63 m2/g, with an average value of 103.44 m2/g; therefore, the PSSA of Type A is much higher than that of Type B. And Figure 4b shows that the pore volume of Type A (where the pore volume is 0.053~0.058 m3/g, with an average value of 0.0565 m3/g) is also much higher than that of Type B (where the pore volume is 0.014~0.048 m3/g, with an average value of 0.0321 m3/g). This also indicates that Aad% has a significant impact on micropore volume and specific surface area. Meanwhile, the relationship between micropore volume and specific surface area at different pore size scales and different types of samples was studied. As shown in Figure 4c,d, the pore volume and specific surface area of pores at the same pore size are both greater for Type A than for Type B, which indicates that the development of micropores at different pore size scales are consistent in terms of micropore volume.

Figure 4.

Micro-pore volume and SSA in different lithofacies samples. (a) Comparison of micropore specific surface area of different lithofacies samples; (b) Comparison of micropore pore volume of different lithofacies samples; (c) Comparison of microporous segmented specific surface area of different lithofacies samples; (d) Comparison of segmented pore volumes of micropores in different lithofacies samples.

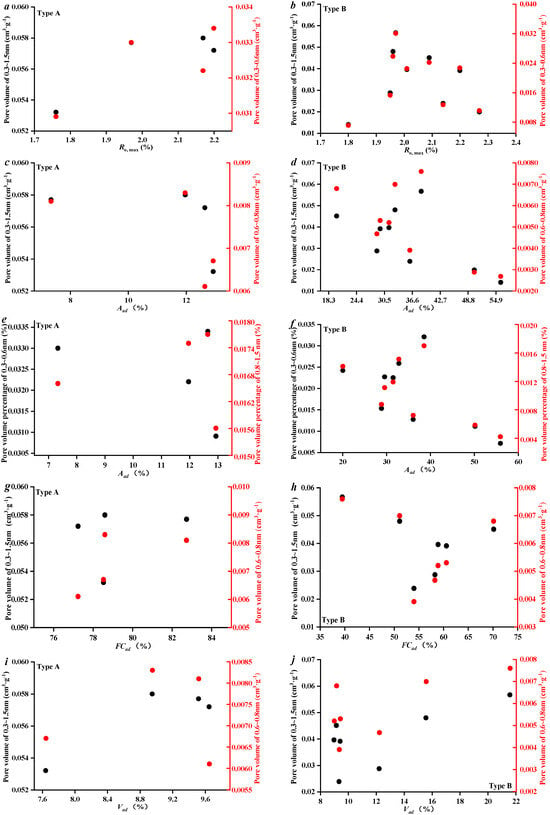

Figure 5a,b show that Ro,max has a differential impact on the micropore distribution of the different sample types. There is a weak positive correlation between Ro,max and micropore volume in type A samples. Aad% in this type is low, making the influence of ash on the pore–fracture structure less pronounced. In contrast, the correlation between Ro,max and pore volume for Type B samples is not obvious. This is because these samples have a higher Aad%, which allows pores to be easily filled, resulting in poor pore development even in coal samples with a high degree of thermal evolution. The correlation between Ro,max and pore volume in Type B samples is not obvious. This is attributed to the higher Aad% in these samples, which tends to fill pores, preventing the development of coal samples with high-heat evolution conditions. Similarly, Figure 5c,d shows the influence of ash content on micropore volume. Type A exhibits a lower correlation between Aad% and pore volume. As previously noted, this type contains minimal ash, resulting in weaker pore-blocking effects. In Type B samples, ash content shows a positive correlation with micropore volume. And when the ash content reaches 30%, the micropore volume gradually decreases as the ash content increases, since this type of sample has a lower Ro value. Figure 5e,f show that pores at different pore size, scales also have distinct differences, and the results are consistent with those in Figure 5c,d. This indicates that the influencing factors of microporous pore structure are not singular. The ash content occupies the pore space, thereby revealing a negative correlation between the ash content and adsorption pore volume.

Figure 5.

Relationship between PV parameter, proximate analysis, and Ro,max. (a) The correlation between the micropore volume of type A sample and Ro,max; (b) The correlation between the micropore volume of type B sample and Ro,max; (c) The correlation between the micropore volume of type A sample and Aad; (d) The correlation between the micropore volume of type B sample and Aad; (e) The correlation between the percentage of micropore pore volume of type A sample and Aad; (f) The correlation between the percentage of micropore pore volume of type B sample and Aad; (g) The correlation between the micropore pore volume of type A sample and FCad; (h) The correlation between the micropore pore volume of type B sample and FCad; (i) The correlation between the micropore pore volume of type A sample and Vad; (j) The correlation between the micropore pore volume of type B sample and Vad.

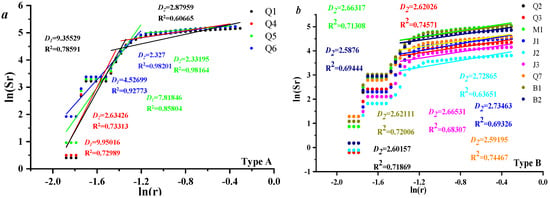

The micropore single-weight fractal dimension was calculated by using Formula (1). Figure 6a shows the single-fractal curve of Type A samples, indicating that the micropore volume of Type A has significant fractal characteristics. ln(r) = −1.2 (r = 0.6 nm) was taken as the boundary; the curve is divided into two segments, which also indicates that the pore structures of 0.3~0.6 nm and 0.6~1.5 nm show significant differences. And the sample D2 ranges from 2.32 to 2.88, with an average value of 2.54; D1 ranges from 4.53 to 9.95, with an average value of 7.91. Similarly, the pore volume of Type B micropores also exhibits fractal characteristics; it is worth noting that when the pore diameter is less than 0.6 nm, the fractal characteristics are not evident. This also suggests to some extent that there are significant differences in the pore structure distribution of the two types of samples. The 0.6~1.5 nm pores of Type B samples exhibit significant fractal characteristics; that is, D2 ranges from 2.59 to 2.73, with an average value of 2.64; D1 ranges from 4.16 to 9.12, with an average value of 6.386889.

Figure 6.

Single and multi-fractal curves of different coal facies. (a) Single fractal curve of type A sample; (b) Single fractal curve of type B sample.

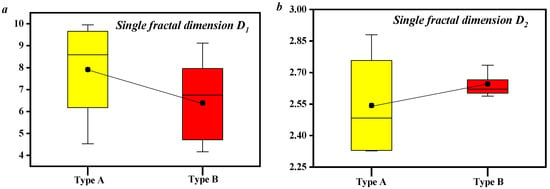

As shown in Figure 7, the fractal dimensions and pore volume distributions are compared between the two sample types, with Type A showing a higher pore volume percentage below 0.6 nm (Figure 7a) and Type B showing a greater proportion within the 0.6–1.5 nm range (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

Single and multi-fractal dimensions of different coal samples. (a) Comparison of D1 fractal dimensions of different coal samples; (b) Comparison of D2 fractal dimensions of different coal samples.

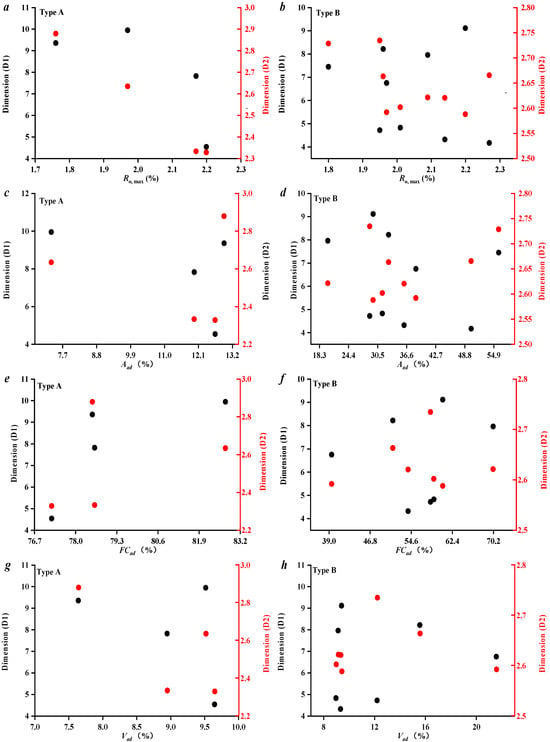

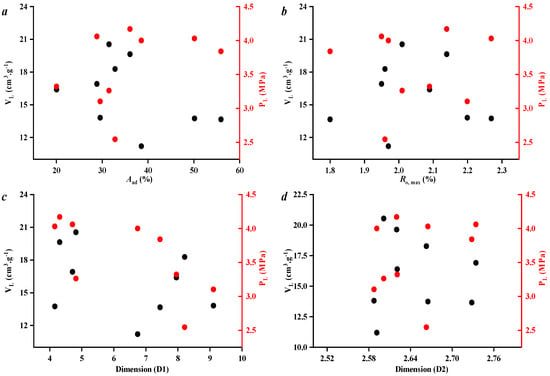

The results show that as Ro increases, the single-weight fractal dimensions D1 and D2 of Type A decrease gradually. This suggests that with the increase in Ro, the heterogeneity of the micropore volume in this type tends to be simplified. In contrast to Type A, the correlation between Ro and the fractal dimension of Type B is weaker, which indicates that Ro is not the only factor affecting the heterogeneity of micropore distribution. In summary, there is a negative correlation between ash content and Type A single fractal, but the fit is low. This also indicates that the main factor affecting the heterogeneous micropore distribution of Type A is Ro, rather than ash content. Figure 8d shows that as the ash content increases, the single fractal dimension value of type B gradually decreases, which also indicates that ash content is one of the factors affecting the heterogeneity of micropore distribution in Type B. Similarly, Figure 8e–h show that here is a poor correlation between fixed carbon/volatile matter and the single fractal dimensions of both types, suggesting that these two factors are not major influences on micropore size distribution heterogeneity.

Figure 8.

Single and multi-fractal dimensions of different coal facies. (a) The correlation between the fractal dimension of type A samples and Ro,max; (b) The correlation between the fractal dimension of B-type samples and Ro,max; (c) The correlation between the fractal dimension of type A samples and Aad; (d) The correlation between the fractal dimension of B-type samples and Aad; (e) The correlation between the fractal dimension of type A samples and FCad; (f) The correlation between the fractal dimension of B-type samples and FCad; (g) The correlation between the fractal dimension of A-type samples and Vad; (h) The correlation between fractal dimension of B-type samples and Vad.

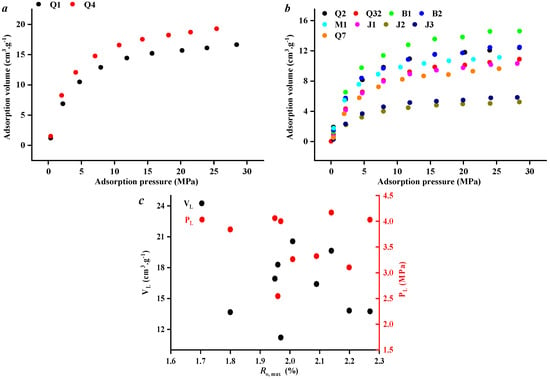

3.3. Effect of Coal Facies and Coal Quality on Methane Adsorption Ability

Adsorption characteristics of the selected samples are described based on the high-temperature and high-pressure methane adsorption experiments in Section 2.2. The results show that the maximum methane adsorption capacity for Type B is 4.21 to 14.62 cm3·g−1, and the methane adsorption amount is enhanced gradually by higher pressures. As the adsorption pressure is below 15 MPa, the methane adsorption amount increases sharply. As the adsorption pressure is higher than 15 MPa, the methane adsorption amount increases slowly and eventually approaches equilibrium. This also indicates that there is a limit to methane adsorption capacity. Compared to Type A, the maximum methane adsorption capacity of Type B shows larger differences, resulting in an average methane adsorption capacity that is less than that of Type A. Overall, Type A exhibits stronger adsorption capacity than Type B, and it is worth noting that there are fewer samples of Type A. Based on the findings above, the ash content in Type B exhibits a more pronounced influence on the pore–fracture structure compared to Type A. To further investigate the effect of ash on pore–fracture structure, subsequent analysis was conducted using Type B samples.

Building upon this foundation, the Langmuir volume (VL) and Langmuir pressure (PL) were derived from Figure 9a,b. Research has shown that VL, which represents the maximum methane adsorption capacity, can serve as a key indicator of the methane adsorption ability of deep CBM. PL is the adsorption pressure corresponding to half of the maximum adsorption capacity for methane, which can also represent the adsorption capability of methane to a certain extent. Therefore, this article selects VL and PL to explore the relationship with Ro. The results indicate that the correlation between Ro and VL and PL in Type B is weak, which further demonstrates that for coal samples with high ash content, the degree of thermal evolution of deep coal seams is not the main factor affecting methane adsorption capacity.

Figure 9.

Isothermal adsorption curves and adsorption parameter of different coal facies. (a) Isothermal adsorption curve of type A; (b) Isothermal adsorption curve of type B; (c) The relationship between adsorption constants VL and PL and Ro,max.

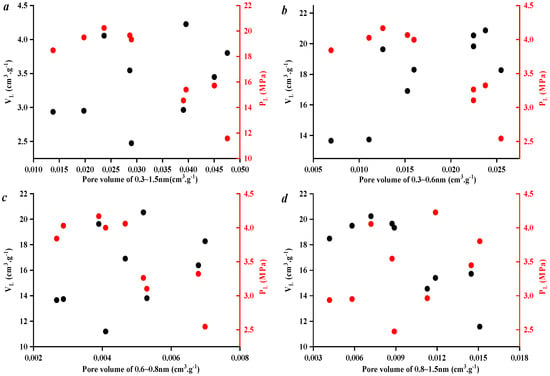

Figure 10a shows that VL increases gradually while PL decreases with increasing micropore volume, though the linear fitting shows a lower correlation. This indicates that while micropores provide adsorption sites for methane, not all specific surface areas across different pore size scales can offer abundant methane adsorption sites. Figure 10b demonstrates a strong linear relationship between the pore volume in the 0.3–0.6 nm range and both VL and PL. This suggests that the specific surface area of micropores in the range of 0.3~0.6 nanometers can provide methane adsorption sites, which are critical pore sizes influencing methane adsorption capacity. Meanwhile, Figure 10c indicates a positive correlation between the pores of 0.6~0.8 nm and VL and a negative correlation with PL. However, the fit is much lower than that shown in Figure 10b. This indicates that the pore structure in this stage has a small impact on methane adsorption capacity, but it is not the main pore size range for methane adsorption. The graph indicates that as the pore volume increases from 0.8 to 1.5 nm, VL gradually decreases while PL gradually increases, but the correlation is weaker. This is attributed to the fact that pores in the 0.8–1.5 nm range account for a small proportion of both pore volume and specific surface area, making them non-primary contributors to the total specific surface area of the micropore system.

Figure 10.

Relationship between micro-pore structure and adsorption parameter. (a) The relationship between microporous pore volume and VL and PL; (b) The relationship between 0.3–0.6 nm microporous pore volume and VL and PL; (c) The relationship between 0.6–0.8 nm microporous pore volume and VL and PL; (d) The relationship between pore volume of 0.8–1.5 nm micropores and VL and PL.

Figure 11a indicates that as Aad% content increases, the VL gradually decreases linearly, suggesting that ash is the main factor affecting the methane adsorption capacity of microporous pores. This is attributed to the higher content of ash filling the micropores, resulting in a gradual reduction in the pore volume within the 0.3–0.6 nm range. Similarly, as shown in Figure 11b, as Ro increases, its correlation with the adsorption parameters becomes less obvious, which indicates that Ro is not the main effecting factor. Figure 11c shows that as D1 gradually increases, VL and PL gradually decrease, indicating that the heterogeneity of pore distribution less than 0.6 nm controls the methane adsorption capacity, which is consistent with the previous understanding.

Figure 11.

Relationship between single and multi-fractal dimension and adsorption parameter. (a) The relationship between Aad and VL and PL; (b) The relationship between Ro,max and VL and PL; (c) The relationship between D1 and VL and PL; (d) The relationship between D2 and VL and PL.

4. Conclusions

(1) Coal samples can be divided into two categories according to Aad%: high-Aad% samples and medium- to low-Aad% samples. The micropore distribution curve of the medium to low-Aad% samples shows a distinct four-peak pattern, while the pore distribution of high-Aad% samples presents a three-peak pattern.

(2) Micropores of 0.3 to 0.6 nm are the key pore sizes affecting methane adsorption capacity. That is, as the non-uniformity of pore volume in the 0.3 to 0.6 nm range increases, the methane adsorption capacity (VL and PL) decreases. This also indicates that not all micropores (0.3~2 nm) and the heterogeneity of pore volume distribution effect methane adsorption capacity.

It should be noted that this article mainly focuses on the study of the pore and fracture structure of deep coal seams in the same well. The difference in thermal evolution degree among these samples is relatively small, which is also the main reason why ash content affects the development characteristics of micropores. Therefore, attention should be paid to this issue in the subsequent research process.

Author Contributions

Methodology, G.R. and Z.Q.; Software, Z.Q.; Validation, V.A.; Formal analysis, G.R.; Writing—original draft, G.R.; Resources, Z.Q.; Investigation: V.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was sponsored by the Natural Scientific Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2023MD110), and Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region Science and Technology Department (2022CGSF0069ZKT).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, S.; Qin, Y.; Tang, D.; Shen, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, S. A comprehensive review of deep coalbed methane and recent developments in China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2023, 279, 104369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Hou, W.; Xiong, X.; Xu, B.; Wu, P.; Wang, H.; Feng, K.; Yun, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; et al. The status and development strategy of coalbed methane industry in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 765–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhao, G.; Ge, Z.; Jia, Y.; Tang, J.; Gong, T.; Huang, S.; Li, Z.; Fu, W.; Mi, J. Challenges and development direction of deep fragmented soft coalbed methane in China. Earth Energy Sci. 2025, 1, 38–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, P.; Zhang, J.; Lv, D.; Vandeginste, V.; Chang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D.; Han, S.; Liu, Y. Effect of water occurrence in coal reservoirs on the production capacity of coalbed methane by using NMR simulation technology and production capacity simulation. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 243, 213353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Bi, Y.; Xian, B. Technical advances in well type and drilling & completion for high-efficient development of coalbed methane in China. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2022, 9, 561–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, J.; Xia, Y. Risk Prediction of Gas Hydrate Formation in the Wellbore and Subsea Gathering System of Deep-Water Turbidite Reservoirs: Case Analysis from the South China Sea. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhang, P.; Li, D.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Duan, Y.; Wu, J.; Liu, N. Reservoir characteristics and gas production potential of deep coalbed methane: Insights from the no. 15 coal seam in shouyang block, Qinshui Basin, China. Unconv. Resour. 2022, 2, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yan, D.; Zhuang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, H. Implications of the pore pressure and in situ stress for the coalbed methane exploration in the southern Junggar Basin, China. Eng. Geol. 2019, 262, 105305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Wang, H.; Sun, B.; Liu, Y.; Fu, X.; Dou, W.; Du, L.; Zhang, B.; Luo, B.; Yang, M.; et al. Quantitative Prediction of Deep Coalbed Methane Content in Daning-Jixian Block, Ordos Basin, China. Processes 2023, 11, 3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, Z.; Yan, X.; Zhou, G.; Wang, G.; Gao, W.; Liu, C.; Lu, B.; Liang, Y. Distribution Law of Occurrence State and Content Prediction of Deep CBM: A Case Study in the Ordos Basin, China. Nat. Resour. Res. 2024, 33, 1843–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xu, J.; Peng, S.; Yan, F.; Zhang, C.; Han, E. Different adsorbed gas effects on the reservoir parameters and production in coalbed methane extraction by multibranch horizontal wells. Energy Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 1370–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, D.; Sun, X.; Wang, H. Quantitative characterization of the evolution of in-situ adsorption/free gas in deep coal seams: Insights from NMR fluid detection and geological time simulations. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2024, 285, 104474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lin, Q.; Zhu, S.; Han, C.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y. NMR investigation on gas desorption characteristics in CBM recovery during dewatering in deep and shallow coals. J. Geophys. Eng. 2023, 20, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Deng, Z.; Hu, H.; Ding, R.; Tian, F.; Zhang, T.; Ma, Z.; Wang, D. Pore structure of deep coal of different ranks and its effect on coalbed methane adsorption. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 59, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ren, T.; Li, X.; Qiao, M.; Yang, X.; Tan, L.; Nie, B. Multi-scale pore fractal characteristics of differently ranked coal and its impact on gas adsorption. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2023, 33, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, K.; Yao, H.; Hao, H. Pore distribution characteristics of various rank coals matrix and their influences on gas adsorption. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2020, 189, 107041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Long, Z.; Song, Y.; Qu, Z. Supercritical CO2 adsorption and desorption characteristics and pore structure controlling mechanism of tectonically deformed coals. Fuel 2022, 317, 123485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ze, D.; Hongyan, W.; Zhenxue, J.; Rong, D.; Yongzhou, L.I.; Tao, W. Influence of deep coal pore and fracture structure on occurrence of coalbed methane: A case study of Daning-Jixian Block in eastern margin of Ordos Basin. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 52, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Chen, B.; Song, L.; Sun, X. Integrated NMR Analysis for Evaluating Pore-Fracture Structures and Permeability in Deep Coals: A One-Stop Approach. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 6854–6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Lv, M.; Li, C.; Sun, Q.; Wu, M.; Xu, C.; Dou, J. Effects of Crosslinking Agents and Reservoir Conditions on the Propagation of Fractures in Coal Reservoirs During Hydraulic Fracturing. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lin, B.; Yang, W.; Li, H.; Lin, M. Fracture and pore development law of coal under organic solvent erosion. Fuel 2022, 307, 121815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, D.; Hu, J.; Zhou, G.; Du, X. Reservoir characteristics of Carboniferous Benxi Formation coal-rock gas in the central and eastern Ordos Basin. Nat. Gas Ind. 2024, 44, 51–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, D.; Li, X. Microscopic pore characteristics of coal seam and the controlling effect of sedimentary environment on pore structure in No.8 coal seam of the Ordos Basin. Coal Sci. Technol. 2024, 52, 142–154. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, D.; Li, X. Discussion on pore characteristics and forming mechanism of coal in the deep area, Ordos Basin: Case study of No.8 coal seam in Well M172 of Yulin area. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2024, 35, 202–216. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Hou, A.; Guo, C. Analysis on correlation between nanopores and coal compositions during thermal maturation process. Mar. Petrol. Geol. 2020, 121, 104608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Qin, Q.; Shao, L.; Liang, G.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Liu, S. Study on the Applicability of Reservoir Fractal Characterization in Middle–High Rank Coals with NMR: Implications for Pore-Fracture Structure Evolution within the Coalification Process. Acs Omega 2021, 6, 32495–32507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Dong, S.; Hu, J. Neotectonics around the Ordos Block, North China: A review and new insights. Earth Sci. Rev. 2020, 200, 102969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Hu, C.; Chen, H.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, F. Tectonosedimentary Patterns of Multiple Interacting Source-to-Sink Systems of the Permian Shanxi Formation, Ordos Basin, China: Insights from sedimentology and detrital zircon U-Pb geochronology. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 168, 107034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, C.; Meng, C. Predicting gas content in coalbed methane reservoirs using seismic waveform indication inversion: A case study from the Upper Carboniferous Benxi Formation, eastern Ordos Basin, China. Acta Geophys. 2022, 70, 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Dong, D.; Qiu, Z.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Deng, Z.; Zhou, S.; Pan, S. Sedimentology and geochemistry of Carboniferous-Permian marine-continental transitional shales in the eastern Ordos Basin, North China. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2021, 571, 110389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 19222-2003; Sampling of Coal Petrology. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2003.

- GB/T 21650.2-2008; Pore Size Distribution and Porosity of Solid Materials by Mercury Porosimetry and Gas Adsorption—Part 2: Analysis of Mesopores and Macropores by Gas Adsorption. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China; China National Standardization Administration: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Zhang, J.; Wei, C.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, T.; Lu, G.; Zou, M. Effects of nano-pore and macromolecule structure of coal samples on energy parameters variation during methane adsorption under different temperature and pressure. Fuel 2021, 289, 119804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Han, R.; Zhang, J.; Vandeginste, V.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Han, S. Prediction of Coal Body Structure of Deep Coal Reservoirs Using Logging Curves: Principal Component Analysis and Evaluation of Factors Influencing Coal Body Structure Distribution. Nat. Resour. Res. 2025, 34, 1023–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 19559-2008; Method of Determining Coalbed Gas Content. China National Coal Association: Beijing, China, 2008.

- GB/T 19560-2008; Experimental Method of High-Pressure Isothermal Adsorption to Coal. China National Coal Association: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Zhang, J.; Hu, Q.; Chang, X.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, X.; Marsh, S.; Grebby, S.; Agarwal, V. Water Saturation and Distribution Variation in Coal Reservoirs: Intrusion and Drainage Experiments Using One- and Two-Dimensional NMR Techniques. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 6130–6143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Vandeginste, V.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Chang, X.; Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, C.; Luo, J.; Quan, F.; et al. Control mechanism of pressure drop rate on coalbed methane productivity by using production data and physical simulation technology. Fuel 2026, 406, 137060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Vandeginste, V.; Miao, H.; Guo, Y.; Ji, Y.; Liu, P.; Peng, Y. Effect of litho-facies on nano-pore structure of continental shale in shuinan formation of Jiaolai Basin. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 228, 212020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.