Abstract

This study comprehensively analyzed the evolution behavior of titanium-bearing phases in carbonized slag during the low-temperature fluidized chlorination process using XRD, SEM-EDS, MLA, and other instruments. The XRD analysis shows that the TiC0.70O0.30 phase is the only crystallization phase present in both titanium-bearing carbonized slag (TiBCS) and titanium extraction tailings (TiET). The intensity of the diffraction peak of this phase is significantly lower in TiET than in TiBCS. The SEM-EDS and MLA indicate that melilite is the main phase in TiBCS and TiET, accounting for 79.16% and 78.13%, respectively. Melilite is composed of a composite of elements, such as Ca, Mg, Si, Al, Ti, and O. The phase remained largely unchanged before and after the chlorination reaction. The TiCxOy and metallic iron content in TiET are significantly lower than in TiBCS. The values decreased from 17.19% and 3.65% to 7.38% and 1.31%, respectively. The main reason affecting the chlorination rate of TiC/TiCxOy and metallic iron is that they are enveloped by dense melilite. Another significant feature of TiET is the presence of numerous Cl-bearing holes of a similar size to TiCxOy. These holes are formed in situ by the chlorination reaction of TiCxOy. The results of this study will provide a clearer understanding for research and industrial production based on the low-temperature chlorination reaction of TiBCS. The results can also provide a reference for optimizing the chlorination reaction process and for improving the efficiency of titanium extraction.

1. Introduction

Titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4) is a critical raw material for producing metallic titanium and titanium dioxide. The traditional processes for the industrial production of TiCl4 mainly include fluidized chlorination and molten-salt chlorination techniques [1,2,3,4]. Titanium-bearing carbonized slag (TiBCS) is a low-grade titanium-bearing raw material that is obtained by subjecting high titanium blast furnace slag (HT-BFS) to a carbonization reduction reaction at a high temperature in the presence of carbon. During the carbonization reduction process, TiO2 will be reduced to TiC by utilizing the disparate reduction trends of various components in HT-BFS, while the remaining oxides remain in their original form [5,6,7,8]. Presently, the accumulation of HT-BFS in the Panxi region of China has surpassed 100 million tons, with an annual increase of 7 million tons [9]. However, the overall utilization rate of the slag remains less than 3% [10]. This situation has led to two impacts. Firstly, a significant quantity of valuable resources is not being used as effectively as it could be. Secondly, it creates a considerable amount of pressure on the local environment and ecology.

Fluidized chlorination refers to the suspension of solid particles in a fluidizing bed, endowing the solid particles with certain characteristics of fluids. Under the agitation and shearing action exerted by the fluid, the interparticle voids expand, enabling intimate contact and enhanced reaction kinetics between solids and fluid, thus achieving excellent mass and heat transfer effects [11,12,13,14]. With the continuous depletion of high-grade titanium raw materials and the increasingly stringent environmental protection requirements, the fluidized chlorination process of TiBCS, as an emerging industrial technology for TiCl4 production, has gradually become the focus of the industry [15,16,17,18,19].

The TiC content in TiBCS is low and dispersed, while the content of other oxide components (CaO, MgO, SiO2, Al2O3, etc.) is as high as 75% or more [20,21,22,23]. This special chemical composition makes it a key technical challenge to improve the selective separation and extraction process of titanium. So far, there have been few studies on the low-temperature chlorination reaction of TiC or TiCxOy in carbonized slag. The existing research mainly focuses on the phase changes during the high-temperature carbonization reduction of HT-BFS to TiBCS, or the product composition of high-grade titanium resources (such as ilmenite) during the reduction process. Some studies directly use analytical reagents containing the titanium element to conduct chlorination reaction research and explore suitable reaction parameters. For example, Najwa Ibrahim et al. [24] successfully demonstrated the conversion of titanium carbonitrides or nitrides (TiC0.7N0.3, TiN, TiC) into TiCl4 at temperatures between 200 and 400 °C, achieving chlorination efficiencies of 79.52% up to near-complete conversion, with XRD analysis showing a significant decrease in the characteristic peak intensity of TiC0.70N0.30. Xiang et al. [25] investigated the carbothermal reduction–nitridation (CRN) process of a nanosized anatase/carbon black mixture and concluded that the phase evolution sequences are as follows: TiO2 (anatase) → TiO2 (rutile) → Ti5O9 → Ti4O7 → Ti3O5 → Ti(N,O) → TiN → Ti(C,N), or TiO2 (anatase) → TiO2 (rutile) → Ti5O9 → Ti4O7 → Ti2O3 → Ti(C,N,O) → Ti(C,N). Yuan et al. [26] studied the chlorination process of Panzhihua titanium concentrate using a new process and found that below 1573 °C, the reduction products of ilmenite included iron, ilmenite, golden rutile, reduced rutile, and carbon. Above 1573 °C, the reduction products consisted of iron, rutile, reduced rutile, carbon, and Ti3O5. Ahmadi et al. [27] experimentally investigated the chlorination behavior of TiN in the temperature range of 250–350 °C and found that the degree of chlorination of TiN increased significantly with rising temperature. Characterization confirmed the shrinking core behavior of TiN and titanium oxycarbonitride (TiO0.02C0.13N0.85) during chlorination. Adipuri et al. [28,29] reported that TiCxO1−x (or TiCxNyOz) could be derived from ilmenite (or rutile) through carbothermal reduction, followed by metallic iron separation and subsequent low-temperature chlorination (200–400 °C) to yield TiCl4. Ren [30,31], Gan [32] et al. conducted a study on the crystallization behavior of blast furnace slag during the cooling process. The results of the experiment indicate that the process of crystal precipitation commences at a temperature of 1350 °C. The primary phases of precipitated crystals are magnesium melilite (Ca2MgSi2O7) and calcium aluminum melilite (Ca2Al2SiO7). In our preceding research [22], we conducted a thorough analysis of the primary phase evolution process and element distribution law of HT-BFS carbonization reduction to TiBCS, employing a range of characterization methods. The results also indicate that the phase that undergoes changes during the carbonization reduction process is mainly perovskite. These phases are almost entirely transformed into TiC or TiCxOy. Furthermore, in TiBCS particles of greater size, it was found that the content of TiC or TiCxOy was higher. These research results have provided a deep understanding of the reaction process from a microscopic level. Unfortunately, the TiBCS low-temperature chlorination reaction process is the core step in extracting titanium resources from HT-BFS → TiBCS → TiET → TiCl4. However, there is a lack of crucial research on the phase evolution process in TiBCS before and after chlorination reaction, especially regarding the titanium-bearing phase. This greatly limits our understanding in this area. The ultimate manifestation in the industrial production process is the inability to effectively improve the efficiency of the TiBCS chlorination reaction for titanium extraction.

A comprehensive investigation was conducted into the microstructure, chemical composition, and mineral composition of TiBCS both before and after the chlorination reaction. This study utilized a range of multi-scale experimental characterization methods. These methods included X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD), scanning electron microscopy–energy dispersive spectroscopy analysis (SEM-EDS), and mineral liberation analysis (MLA). The limiting factors influencing the chlorination rate of the titanium-bearing phase are analyzed. The findings aim to provide theoretical support and a scientific basis for achieving environmentally sustainable and highly efficient separation and extraction of titanium resources from TiBCS. It can also provide optimization directions for the TiBCS chlorination reaction process and reaction parameters.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

TiBCS is supplied by Pangang Group Research Institute Co., Ltd. (Panzhihua, China). As shown in Table 1, its typical chemical composition contains 13.86 wt.% TiC, with combined oxides (CaO, MgO, SiO2, and Al2O3) accounting for 76.22% of total mass. The liquid chlorine (supplied by Panzhihua Gangcheng Group Co., Ltd., Panzhihua, China) is vaporized to provide Cl2 gas with a volumetric purity of 98%.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of TiBCS (wt.%).

In the context of industrial production, TiBCS is introduced in a continuous manner from the upper part of the chlorination furnace material layer. It is evident from extant research results that the chlorination reaction necessitates occurrence within a suitable temperature range [33,34]. If the temperature is low, the chlorination efficiency of TiCxOy is low. If the temperature is too high, it may cause material melting and bonding in the furnace, leading to a flow loss problem. Taking all factors into consideration, the actual temperature for the chlorination reaction in industrial production is maintained between 500 and 530 °C.

The Cl2 and N2 gases are mixed in a volume ratio of 7:3 and continuously introduced from the bottom to react with the slag. The primary function of N2 is to reduce the concentration of Cl2 and prevent the instantaneous release of a large amount of heat when higher concentrations of Cl2 react with the slag. The second consideration is from an economic perspective of utilizing Cl2. The appropriate concentration of Cl2 can improve its utilization efficiency and prevent a large amount of Cl2 from flowing out of the chlorination furnace without reacting. In addition, it can also reduce the pressure during the subsequent TiCl4 refining process.

The titanium-extraction tailings (TiET) are continuously discharged from the middle-upper region of the bed. The TiCl4-bearing mixed gas exits through the top outlet of the furnace and is directed to a spray tower for collection.

2.2. Analytical Methods

2.2.1. Chlorination Rate

The chlorination rate (α) is calculated based on the changes in the content of various components (such as TiC, CaO, MgO, etc.) in the slag before and after the reaction in industrial production, as shown in Equation (1).

In Equation (1), M1 denotes the mass of the slag before chlorination. C1 represents the content of a component in the slag before the reaction, wt.%. M2 is the mass of the slag after chlorination. C2 corresponds to the content of the component in the slag after the reaction in wt.%.

2.2.2. Material Characterization

The main chemical composition and content of TiBCS and TiET are determined by chemical titration analysis [35]. The TiC content in the slag is determined by a combination of chemical reagents and ICP instruments [36]. Specifically, the process entails the transfer of the ground slag to a beaker, followed by the introduction of a sulfuric acid–hydrofluoric acid mixture. This approach is designed to facilitate the dissolution of other oxides, with the exception of TiC. Following filtration, the residue should be incinerated in order to produce the powder for testing. The powder to be tested is mixed with lithium tetraborate and lithium carbonate flux in order to create a sheet-like sample. Finally, the sample is subjected to XRF detection to obtain the total Ti content contained therein. The calculation of the mass proportion of TiC in the slag is undertaken on the basis of the Ti content in the form of TiC.

Particle size analysis was conducted by wet-method testing using a Malvern laser particle size analyzer (WFXZetasizer 3000, Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK). The X-ray diffraction pattern was obtained by detection with an X-ray diffractometer (Empyrean, Cu–Kα, 10–120° (2θ), step 0.013°, scanning speed 2°/min, 50 mA, and 35 kV). The analysis of the X-ray diffraction pattern was conducted utilizing the MDI Jade 9 software.

The microstructure, elemental distribution, and phase types were characterized by a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Sigma 500, Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany) equipped with an energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS) and a Mineral Liberation Analyzer (MLA650F, FEI Company, USA). We have a basic understanding of the types of elements contained in slag. Therefore, the types of elements analyzed during SEM-EDS testing are manually determined.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. XRD Patterns and Particle Size Distributions

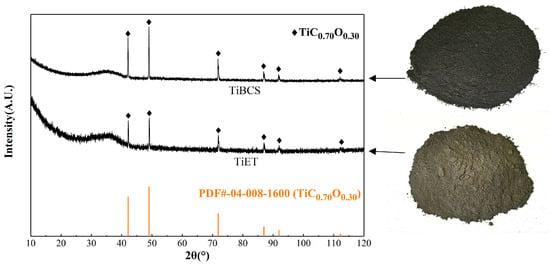

Figure 1 shows the X-ray diffraction patterns of TiBCS and TiET. In comparison with TiBCS, the diffraction peak intensity of the TiC0.70O0.30 phase in TiET is significantly reduced. The calculation yielded a percentage decrease in diffraction peak intensity of 69.87% (calculated based on the strongest diffraction peak). However, the incomplete disappearance of its diffraction peak also indicates the presence of an unreacted TiC0.70O0.30 phase in TiET.

Figure 1.

X-ray diffraction patterns of TiBCS and TiET materials.

As illustrated in Table 1, in addition to TiC, TiBCS also contains numerous other components. However, no sharp diffraction peaks indicating the presence of other phases are observed in the X-ray diffraction pattern. A broad and smooth diffuse peak appears in the low-angle region. It belongs to the characteristic peak of the amorphous phase. It is hypothesized that the presence of TiC or TiCxOy in the structure of the material contributes to its high hardness, melting point, and stable structure. During the high-temperature carbonization and reduction process of HT-BFS, the formation of TiC or TiCxOy by reduction results in a stable crystal structure. Consequently, diffraction peaks of pertinence can be identified. In the case of impurity oxides, these elements bind together in a molten state, resulting in an absence of a fixed crystal structure. Therefore, no diffraction peaks corresponding to the expected crystalline structure could be identified in the X-ray diffraction pattern.

Furthermore, for phases that clearly have crystal structures but have not found corresponding diffraction peaks, such as metallic iron and free carbon, it is speculated that there may be two reasons for this phenomenon. Firstly, the content is relatively low, falling below the detection limit of the X-ray diffractometer. Secondly, the presence of strong diffraction peaks in TiC or TiCxOy results in the masking of lower intensity diffraction peaks, thereby rendering them undetectable against the background. This complicates the process of accurate identification.

The particle size distributions of TiBCS and TiET are presented in Figure 2. Among them, D [4,3] represents the volume average particle size. DV(10), DV(50), and DV(90) represent the corresponding particle size values when the cumulative volume fraction reaches 10%, 50%, and 90%, respectively. The particle size detection results indicate that the particle size of TiET is decreasing compared to TiBCS. It can be inferred from the reaction mechanism and process that TiC or TiCxOy exposed on the surface or shallow layer of particles reacts with Cl2 to form gas-phase TiCl4 products, which may be the reason for the decrease in particle size. This phenomenon is similar to the common unreacted nucleus model in gas–solid reactions. In addition, the flushing of solid particles by the airflow inside the fluidized bed reactor and the high-speed impact between particles under the action of the airflow may also lead to a decrease in particle size.

Figure 2.

The particle size distributions of TiBCS and TiET.

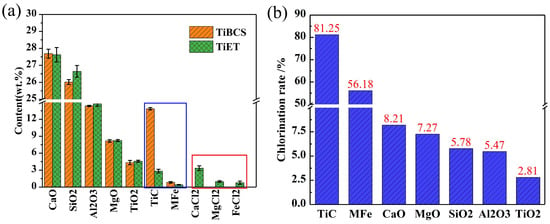

3.2. Chemical Composition and Chlorination Selectivity

Table 2 presents the composition and content of TiET formed by TiBCS following the chlorination reaction process. It is estimated that approximately 8% by mass is lost following chlorination of TiBCS to form TiET during the production process. Consequently, by integrating the composition alterations depicted in Table 1 and Table 2, the chlorination rates of each constituent can be determined. As illustrated in Figure 3, the alterations in the composition of each constituent of the slag are demonstrated before and after the chlorination reaction (Figure 3a), along with the chlorination rate (Figure 3b).

Table 2.

Chemical composition of TiET (wt.%).

Figure 3.

The chemical compositions (a) and chlorination rates (b) of TiBCS and TiET.

As demonstrated in Figure 3a, the reaction with Cl2 leads to a substantial decline in the content of TiC or TiCxOy and MFe (within the blue box) in the slag. As demonstrated in Figure 3b, the chlorination rates are recorded as 81.25% and 56.18%, respectively. The content of the quinary slag system (CaO-MgO-SiO2-Al2O3-TiO2) in the slag did not show significant changes before and after the chlorination reaction, and its chlorination rate was also low, ranging from 2.81% to 8.21%. It has been established that the AlCl3 and SiCl4 substances escape directly from the chlorination furnace in gaseous form at the reaction temperature. Consequently, the newly introduced chlorides in the slag following the chlorination reaction are predominantly CaCl2, MgCl2, and FeCl2 (see red box). The concentrations of these substances are relatively low, with percentage concentrations of 3.35%, 0.98%, and 0.78%, respectively. This also fully reflects the selectivity of the chlorination reaction of TiBCS. Both TiC or TiCxOy in the slag and metallic iron have high reaction priority.

Furthermore, a component has been identified whose content changes have hitherto been overlooked in previous related research. This component is free carbon. Theoretical calculations indicate that if the TiC content is 13.86%, all TiC in 100 g of slag will react to produce 2.76 g of free carbon. It is evident from the existing free carbon content (2.30%) of TiBCS that the theoretical mass fraction of free carbon in TiET should be approximately 5.71%. As demonstrated in Table 2, the content of free carbon in TiET is a mere 2.96%. This is considerably lower than the theoretical content. It is speculated that the newly generated free carbon exhibits high reactivity and undergoes a carbon chlorination reaction with oxides (especially CaO and MgO) in the slag. This process will react with free carbon to reduce its mass fraction.

3.3. SEM Morphological Analysis

Figure 4 presents the SEM micrographs of TiBCS and TiET particles. As observed in Figure 4a,c, both TiBCS and TiET exhibit the particle structures with heterogeneous sizes, which is consistent with the particle size distribution results in Figure 2. A greater quantity of debris is observed to be attached to the surface of TiBCS particles, while the surface of TiET particles is found to be relatively smooth. This should be caused by the debris attached to the surface of the particles being reacted or washed away by the airflow during the chlorination reaction. In comparison with the dense surface of TiBCS particles, a greater number of obvious holes are present on the surface of TiET particles. It is speculated that TiC or TiCxOy inside the particles is reacted to form gas-phase TiCl4. Further analysis will be conducted based on the distribution of elements to support this viewpoint.

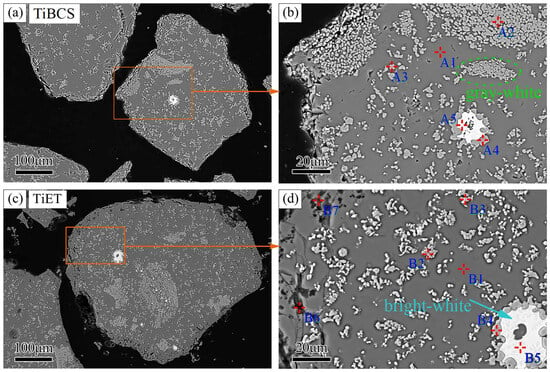

Figure 4.

The SEM morphology of TiBCS and TiET particles (The (a,c) are the microstructure images of TiBCS and TiET particles, respectively. The (b,d) are enlarged images of the box areas in (a,b), respectively).

3.4. Internal Structure, Composition, and Elemental Distribution

TiBCS and TiET particles are dispersed and solidified with epoxy resin to reveal the evolution of particle internal structures before and after chlorination. The subsequent process involves the exposure of the internal structure through grinding and polishing, followed by observation through backscattered electron imaging (BSE) under a scanning electron microscope, as illustrated in Figure 5. Table 3 and Table 4 present the energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) point analysis for the elemental composition of TiBCS and TiET.

Figure 5.

The internal structure of TiBCS and TiET particles (The (a,c) are the microstructure images of TiBCS and TiET particles, respectively. The (b,d) are enlarged images of the box areas in (a,b), respectively).

Table 3.

Elemental point analysis of TiBCS using EDS.

Table 4.

Elemental point analysis of TiET using EDS.

The internal structures of TiBCS (Figure 5a) and TiET (Figure 5c) exhibit similar irregular shapes with poor sphericity and dense matrices. The holes are prominently distributed around TiET particles. The high-resolution BSE images of TiBCS (Figure 5b) and TiET (Figure 5d) are captured with point composition analysis. The main regions of TiBCS and TiET particles appear gray (positions A1 and B1), containing a small amount of Ti and abundant elements of O, Al, Si, Ca, and Mg. This indicates that the gray region is formed by the composite of multiple oxides.

The fine gray-white particles in TiBCS and TiET (positions A2, A3, B2, B3) are dominated by Ti, C, and O, with trace Al, Si, and Ca. The main composition of gray-white particles is TiC0.66O0.29, close to the TiC0.70O0.30 phase measured by an X-ray diffractometer. The bright-white particles (positions A5, B5) with Fe contents of 97.96% and 83.62%, containing trace Ti, C, Si, and Mn, are identified as iron beads. Larger gray-white particles (positions A4, B4) continuously distribute around iron beads, mainly containing Ti and C with V, Fe, and Ca, indicating that TiCxOy aggregates around iron beads. As shown in Figure 5d, in the hole regions at TiET particle edges (positions B6, B7), Ti content decreases significantly while O, Al, Si, and Ca are enriched; the edge region of TiCxOy reacts with Cl2 and is consumed during chlorination.

As illustrated in Figure 6 and Figure 7, there is a high degree of overlap in the distribution of O, Ca, Mg, Si, and Al elements in the gray matrix. As previously stated, they constitute a composite oxide. It can be seen that the elemental content in this composite oxide did not significantly change before and after the chlorination reaction from the point scan results in Figure 6j and Figure 7k.

Figure 6.

The elemental analysis of TiBCS using EDS (The (b–i) represents the types and distribution of elements in image (a). The numbers 1–4 in (j) represent the types and specific contents of elements in the corresponding numerical regions of image (a)).

Figure 7.

The elemental analysis of TiET using EDS (The (b–j) represents the types and distribution of elements in image (a). The numbers 1–4 in (k) represent the types and specific contents of elements in the corresponding numerical regions of image (a)).

As illustrated in Figure 7, the TiET is characterized by the presence of unchlorinated gray-white TiCxOy and bright-white iron beads. Both of these phases are enveloped by gray composite oxides, which exhibit significant diffusion barriers at the reaction kinetics level. Therefore, this is the main reason why they did not undergo chlorination reaction.

Another significant feature of TiET particles compared to TiBCS particles is the presence of holes, as indicated by the white arrow in Figure 7c. In these regions, the distribution of C and Ti elements no longer exhibits significant overlap. Conversely, a substantial distribution of the Cl element is observed. This finding further proves that these holes are left behind after the TiCxOy chlorination reaction.

3.5. Evolution of Titanium Phase

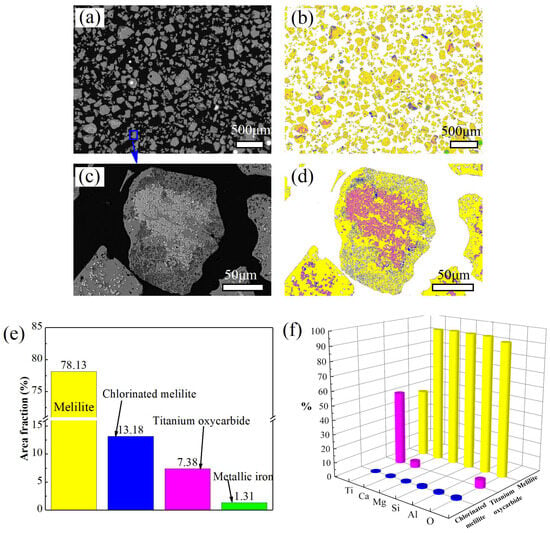

The XRD analysis in Figure 1 confirms that the sole crystalline phase before and after chlorination of TiBCS is TiC0.70O0.30. However, as demonstrated in the above micrograph, the majority of the slag is occupied by the gray area. It is an amorphous composite oxide formed by elements such as Ca, Mg, Si, Al, Ti, and O. Therefore, its phase cannot be identified when using an X-ray diffraction analyzer. In order to compensate for this deficit, a detailed and comprehensive analysis was conducted on the distribution and content of phases and the Ti element in the slag using a mineral dissociation analyzer (MLA).

As demonstrated in Figure 8 and Figure 9, TiBCS predominantly constitutes three phases: melilite, titanium oxycarbide, and metallic iron. The TiET is primarily constituted of four phases: melilite, titanium oxycarbide, metallic iron, and chlorinated melilite. The respective area proportions are illustrated in Figure 8e and Figure 9e. As illustrated in Figure 8f and Figure 9f, the analysis indicates that the elements Ca, Mg, Si, Al, and O are predominantly present in the melilite phase within both TiBCS and TiET. In the study of the phase composition of HT-BFS, Ca2Al2SiO7 and Ca2MgSi2O7 are considered to be its primary constituent phases. The term melilite is used to denote this group collectively. During the high-temperature carbonization reduction of HT-BFS and the low-temperature selective chlorination reaction of TiBCS, the impurity oxides did not react significantly. Consequently, it is hypothesized that the composition of melilite in TiBCS and TiET is essentially congruent with that in HT-BFS. As demonstrated in the preceding EDS point scan analysis, the melilite phase exhibited a minimal content of the Ti element. It is evident that the presence of the melilite phase is particularly pronounced in both types of slag, exhibiting an exceptionally high proportion. This results in the distribution of the Ti element in a roughly equal proportion in the melilite and TiCxOy phases (see Figure 8f and Figure 9f). The Ti element in the melilite exists predominantly in the form of TiO2, thereby precluding the possibility of a reaction with Cl2 to form TiCl4 during the course of low-temperature chlorination. This phenomenon also exerts a substantial influence on the efficiency of titanium extraction in the TiBCS low-temperature chlorination reaction. In order to enhance the efficiency of titanium extraction from TiBCS in the future, it is recommended that this aspect be analyzed and considered in depth.

Figure 8.

The MLA of TiBCS particles (The (c) is an enlarged image of the boxed area in image (a). The (b,d) are the phase recognition results of images (a,c), respectively. The (e) is the proportion of the area of different phases in the statistical image (a). The (f) is the proportion of each element in image (a) in different phases).

Figure 9.

The MLA of TiET particles (The (c) is an enlarged image of the boxed area in image (a). The (b,d) are the phase recognition results of images (a,c), respectively. The (e) is the proportion of the area of different phases in the statistical image (a). The (f) is the proportion of each element in image (a) in different phases).

Following the chlorination reaction, the proportion of TiCxOy in the slag decreased from 17.19% to 7.38%. Concurrently, the proportion of metallic iron has experienced a decline from 3.65% to 1.31%. As previously discussed, the underlying cause of the incomplete chlorination reaction is its encapsulation by melilite. Notwithstanding the evident propensity for chlorination reactions at the thermodynamic level, it is an inevitable consequence of the inherent properties of the system that diffusion and mass transfer obstacles will be present at the level of reaction kinetics.

In comparison with TiBCS, a novel phase, designated as chlorinated melilite, has emerged in TiET. As illustrated in Figure 9c,d, its presence is predominantly observed at the edges of the holes. It is evident from the results of the detection and analysis that the initial phase of the hole area is occupied by the TiCxOy phase. During the chlorination reaction, TiCxOy reacts with Cl2 to form gas-phase TiCl4, leaving holes in the reaction site. The TiCxOy chlorination reaction produces elemental carbon, but there is not much of it, and it does not fill the formed holes completely. Conversely, due to its high reactivity, it can undergo a carbon-catalyzed chlorination reaction with the adjacent melilite phase, resulting in the formation of chlorinated melilite. This phenomenon can also provide a rationale for the absence of a substantial increase in the free carbon content subsequent to the transition from TiBCS to TiET.

Figure 10 shows the thermodynamic calculation results of the main components in TiBCS reacting with Cl2 using FactSage 8.1 software. Table 5 shows the relationship between the ΔGθ values of different components reacting with Cl2 and the chlorination temperature (T). The databases selected are FactPS and FToxid. Each chlorination reaction equation is calculated using 2 mol Cl2 as the standard. The temperature range is 0–1000 °C.

Figure 10.

Thermodynamic reactivity trends of the main components in TiBCS with chlorine gas.

Table 5.

The main chlorination reaction equations and ΔGθ in TiBCS.

As demonstrated in Figure 10 and Table 5, the standard Gibbs free energy for the reaction of TiC and metallic iron with Cl2 is negative within the temperature range of the chlorination reaction (500–530 °C). The negative ΔGθ values are found to be larger in comparison to the chlorination reactions of Ca2MgSi2O7 and Ca2Al2SiO7. This finding indicates that the chlorination reaction trend between TiC and metallic iron is greater than that of Ca2MgSi2O7 and Ca2Al2SiO7, which is consistent with the previously observed phase evolution and element distribution patterns. Furthermore, an examination of the ΔGθ values of Ca2MgSi2O7 and Ca2Al2SiO7 pure chlorination reactions reveals that both are positive, thereby indicating that these reactions are not capable of occurring in isolation. However, in the presence of free carbon in the system, a carbon-catalyzed chlorination reaction can occur, with the formation of CO2 being the preferred outcome. This finding is consistent with the detection of elevated levels of CO2 in exhaust gas during the course of actual production.

Based on the integrated characterization, Figure 11 schematizes the titanium phase evolution of TiBCS during the fluidized chlorination. The original TiBCS structure comprises a gray melilite matrix embedded with finely dispersed TiCxOy (gray-white) and metallic iron (bright-white) particles. After the fluidized chlorination, the TiET particles retain unreacted TiCxOy and iron phases internally, while holes form at the edges of the particles due to the consumption of TiCxOy during the reaction. These hole regions are occupied by the chlorinated melilite, demonstrating the hindering role of the melilite matrix against complete titanium extraction.

Figure 11.

Schematic diagram of titanium phase evolution in TiBCS during fluidized chlorination.

4. Conclusions

The characterization of the samples was conducted using a range of analytical techniques, including XRD, laser particle size analyzer, SEM-EDS, and MLA. The study systematically elucidated the evolution behavior of the titanium-bearing phases during the fluidized chlorination process of titanium-bearing carbonized slag (TiBCS). The key findings are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- The crystallization phase in TiET is still only TiC0.70O0.30, but compared to TiBCS, its diffraction peak intensity is significantly reduced. The thermodynamic calculations and characterization results fully demonstrate the characteristics of low-temperature selective chlorination.

- (2)

- TiBCS and TiET are mainly composed of calcium aluminum melilite (Ca2Al2SiO7) and magnesium melilite (Ca2MgSi2O7). The MLA shows that their area proportions reach 79.16% and 78.13%, respectively, with almost equal content between the two. After the chlorination reaction, the proportion of TiCxOy and metallic iron decreased from 17.19% and 3.65% to 7.38% and 1.31%, respectively.

- (3)

- The main reason for the incomplete chlorination reaction between TiCxOy and metallic iron is the formation of encapsulated structures. The dense melilite matrix completely envelops them, hindering the inward diffusion trend of chlorine gas. This significantly affects the probability of their chlorination reaction.

- (4)

- One of the main features of TiET is the presence of numerous chlorinated melilite holes formed in situ by the TiCxOy chlorination reaction.

Author Contributions

J.W.: Writing—original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Validation. L.W.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration. D.Y.: Visualization. F.Z.: Formal analysis, Resources. Y.Z.: Investigation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Major Science and Technology Achievement Transformation Project of Central Universities in Sichuan (Project Number: Grant No. 2022ZHCG0123. Accept the sponsor as Jianxin Wang).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Jianxin Wang and Fuxing Zhu were employed by the Pangang Group Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yang, F.; Wen, L.Y.; Peng, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, J.; Hu, M.L.; Zhang, S.F.; Yang, Z.Q. Prediction of structural and electronic properties of Cl2 adsorbed on TiO2(100) surface with C or CO in fluidized chlorination process: A first-principles study. J. Cent. S. Univ. 2021, 28, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wen, L.Y.; Yue, D.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, Q.; Hu, M.L.; Yang, Z.Q. Study on reaction behaviors and mechanisms of rutile TiO2 with different carbon addition in fluidized chlorination. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 18, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.Z.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Che, Y.S.; He, J.L. Efficient separation process of niobium and titanium: In-situ chlorination-cascade con-densation assisted by molten salt. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 379, 135101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.; Li, L.; Jia, Y.Q.; Liu, D.C.; Jiang, W.L.; Kong, L.X. Chlorination Behavior of Low-Grade Titanium Slag in AlCl3-NaCl Molten Salt. JOM 2022, 74, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Jiang, T.; Chen, B.J.; Wen, J. Overall Utilization of Ti-Extraction Blast Furnace Slag as a Raw Building Material: Removal of Chlorine from Slag by Water Washing and Sintering. J. Sustain. Metall. 2021, 7, 1116–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.Q.; Wang, M.; Dang, J.; Zhang, R.; Lv, Z.P.; He, W.C.; Lv, X.W. A novel recycling approach for efficient extraction of titanium from high-titanium-bearing blast furnace slag. Waste Manag. 2021, 120, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.T.; Song, J.W.; An, Y.F.; Hu, T.; Lin, G. Reduction of ilmenite and preparation of titanium-based carbides in the CH4-H2 system. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1034, 181315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Liu, P.S.; Yue, Y.H.; Zhang, J.Z. Vacuum Carbothermic Reduction of Panzhihua Ilmenite Concentrate: A Thermodynamic Study. Miner. Process. Extr. Metall. Rev. 2017, 38, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Lv, X.M.; Shi, Z.X.; Gao, J. Process Mineralogical Study on Blast Furnace Slag During High-Temperature Carbonization—Low-Temperature Chlorination. Metall. Anal. 2025, 45, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Tu, G.F. Extraction of vanadium and enrichment of titanium from modified Ti-bearing blast furnace slag. Hydrometallurgy 2021, 201, 105577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, R.Y.; Wang, Y.L.; Zhang, T.A.; Wang, X.J.; Li, J.D.; Zhao, X.X.; Li, W.J. Research and application mechanism of chlorination roasting for polymetallic minerals and waste. Miner. Eng. 2025, 232, 109493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.Q.; Zhang, H.X.; Wang, X.F.; Hu, H.; Zhu, Z.P. Characterization of fluidized reduction roasting of nickel laterite ore under CO/CO2 atmosphere. J. Cent. S. Univ. 2024, 31, 3068–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.Z.; Middlemas, S.; Guo, J.; Fan, P. A new, energy-efficient chemical pathway for extracting Ti metal from Ti minerals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18248–18251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.X.; Ma, S.R.; Ma, Z.S.; Qi, L.H.; Peng, W.X.; Li, K.H.; Qiu, K.H. Preparation of TiCl4 from panzhihua ilmenite concentrate by boiling chlorination. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 2703–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.J.; Qiu, Y.C.; Yu, B.; Xie, X.K.; Dong, J.J.; Hou, C.L.; Li, J.Z.; Liu, C.S. Titanium Extraction from Titania-Bearing Blast Furnace Slag: A Review. JOM 2022, 74, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.Y.; Liu, S.L.; Lv, X.W.; Bai, C.G. Preparation of rutile from ilmenite concentrate through pressure leaching with hydrochloric acid. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2017, 48, 1333–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Tu, G.F. Recovery of Fe, V, and Ti in modified Ti-bearing blast furnace slag. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2022, 3, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.C.; Li, Z.C.; Zhang, J.B.; Mao, H.C.; Ma, S.G.; Fan, C.L.; Zhu, Q.S. Chlorination behaviors for green and efficient vanadium recovery from tailing of refining crude titanium tetrachloride. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 420, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; He, F.P.; Hu, Q.Q.; Huang, Q.Y.; You, Z.X.; Qiu, G.B.; Lv, X.W. Isothermal reduction and nitridation kinetics of ilmenite concentrate in ammonia gas. Miner. Eng. 2023, 203, 108319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Zhang, J.L.; Zhao, B.J.; Liu, Z.J. Extraction of titanium resources from the titanium-containing waste slag: Thermodynamic analysis and experimental verification. Calphad 2020, 71, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H.; Kou, J.; Sun, T.C.; Wu, S.C.; Zhao, Y.Q. Effects of calcium compounds on the carbothermic reduction of vanadium titanomagnetite concentrate. Int. J. Min. Met. Mater. 2020, 27, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.X.; Yue, D.; Wen, L.Y.; Hu, L.W.; Lv, X.M. Experimental characterization of chemical mineral composition and morphology of titanium in carbonized slag particles. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 34, 1571–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.H.; Rao, M.J.; Xiao, P.D.; You, J.X.; Li, G.H. Beneficiation of Nb and Ti carbides from pyrochlore ore via carbothermic reduction followed by magnetic separation. Miner. Eng. 2022, 180, 107492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.; Kin, L.H.; Ahmadi, E.; Baharun, N.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Rezan, S.A. Chlorination of Titanium Carbonitride (TiC0.7N0.3) for Production of TiCl4. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1082, 012032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.P.; Liu, Y.; Gao, S.J.; Tu, M.J. Evolution of phase and microstructure during carbothermal reduction-nitridation synthesis of Ti(C,N). Mater. Charact. 2008, 59, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.F.; Zhu, Y.Q.; Xi, L.; Xiong, S.F.; Xu, B.S. Preparation of TiCl4 with multistage series combined fluidized bed. Trans. Nonferr. Met. Soc. China 2013, 23, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, E.; Rezan, S.A.; Baharun, N.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Fauzi, A.; Zhang, G.Q. Chlorination kinetics of titanium nitride for production of titanium tetrachloride from nitrided ilmenite. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2017, 48, 2354–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adipuri, A.; Zhang, G.Q.; Ostrovski, O. Chlorination of titanium oxycarbonitride produced by carbothermal nitridation of rutile. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adipuri, A.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.Q.; Ostrovski, O. Chlorination of reduced ilmenite concentrates and synthetic rutile. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2011, 100, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.Q.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Long, Y.; Chen, S.S.; Zou, Z.S.; Zhang, C.X. Study on Crystallization Behavior in Fibrosis Process of Molten Blast Furnace Slag. Iron Steel Vanadium Titan. 2017, 38, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.Q.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Long, Y.; Zou, Z.S. Study of Non-isothermal Crystallization Kinetics of Modified Blast Furnace Slag. J. Northcastern Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2017, 38, 960–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Zhang, C.X.; Zhou, J.C.; Shangguan, F.Q. Continuous cooling crystallization kinetics of a molten blast furnace slag. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2012, 358, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.X.; Yang, Y.J.; Lu, P.; Liu, S.L. Research on Low-temperature Chlorination Process of Pangang Carbonized Slag. Iron Steel Vanadium Titan. 2011, 32, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.X.; Yang, Y.J.; Lu, P.; Liu, S.L.; Wang, Y. Study on Preparation of TiCl4 Using Titanium-containing Carbonized Blast Furnace Slag as Raw Material. Iron Steel Vanadium Titan. 2016, 37, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, B.L. X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometric Determination of Major and Minor Components in Titanium-Rich Material with Fusion Sample Preparation. Metall. Anal. 2013, 33, 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.P.; Yang, X.N. Determination of Titanium Carbide in Titanium Carbide Slag by X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry with Fusion Sample Preparation. Metall. Anal. 2025, 45, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.