Abstract

Material tracking and localization are key applications of Industry 4.0 in manufacturing process control. Traditional approaches—such as barcode or QR code identification and RTLS-based localization using RF/UWB, 5G or GPS–require a large and complex infrastructure. As an alternative, this paper proposes an IoT-based solution that combines short-range Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) communication with LPWAN LoRaWAN networks. Hybrid solutions using LoRaWAN and BLE technologies already exist, but pure localization based on BLE tags can lead to ambiguous asset identification in geometrically dense scenarios. Our paper aims to solve this problem with an alternative concept called Associated LoRaWAN Sensors (ALSs). An ALS enables logical grouping and integration of heterogeneous LoRaWAN sensors, providing their own data or directly scanning BLE tags. Sensor data can be combined and supplemented with new information, data, and events, supported by application logic (use case). Although ALS represents a general concept that could be applicable to various use cases (such as warehouse monitoring, object tracking), our paper will focus mainly on material tracking and validation in manufacturing. For this purpose, we designed a specific ALS model that integrates a classic LoRaWAN BLE sensor with an additional LoRaWAN magnetic contact sensor. The magnetic contact switch can provide validation of exact position, in addition to localization by BLE tag. Experimental validation using BLE tags (Trax 10229) and LoRaWAN sensors (IoTracker3, Milesight WS301) demonstrates the usability of the ALS model in typical industrial scenarios. We also measured RSSI and evaluated the accuracy of tag localization (3 × 25 = 75 tests) for the worst-case scenario: material validation on a machine with a BLE tag distance of ~0.5 m. While the traditional approach showed up to a 20% failure rate, our ALS model avoided the issue of incorrect accuracy. An additional magnetic switch in ALS confirmed that the correct carrier with the associated tag is attached to the machine and eliminated incorrect localization. The results confirm that a hybrid model based on BLE and LoRaWAN scanning can reliably support material localization and validation without the need for dense RTLS infrastructures.

1. Introduction

Efficient material flow tracking and validation are essential prerequisites for data-driven manufacturing and Industry 4.0 process optimization [1]. Manufacturing enterprises increasingly require continuous visibility of material carriers, semi-finished products, and logistics assets to improve internal logistics, reduce downtime, and increase Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE). In many practical scenarios, however, the primary requirement is not precise geometric localization but rather reliable detection of material presence, movement, and interaction with machines or workstations.

Conventional material identification methods, such as barcode or QR code scanning, provide only discrete and operator-dependent information, making them unsuitable for automated real-time monitoring [2]. More advanced solutions rely on Real-Time Locating Systems (RTLSs) using technologies such as UWB, Wi-Fi, active RFID, 5G, or NB-IoT [3], which enable high positioning accuracy through techniques such as Time of Flight (ToF), Time Difference of Arrival (TDoA), or Angle of Arrival (AoA) [4]. Despite their accuracy, RTLS deployments require dense anchor infrastructures, continuous power supply, and extensive calibration, leading to high installation and operational costs. As a result, such systems are often economically unjustifiable for medium-sized manufacturing enterprises or legacy production facilities.

The rapid development of Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) technologies has opened alternative approaches to material tracking based on low-power wireless sensors and long-range communication networks. Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) enables low-cost and energy-efficient object tagging with zone-level detection capabilities, while Low Power Wide Area Network (LPWAN) technologies—particularly LoRaWAN—provide long-range, infrastructure-light data transmission suitable for large industrial sites [5,6]. Hybrid BLE–LoRaWAN systems are therefore increasingly considered a practical alternative to classical RTLS solutions in scenarios where process validation and area-level localization are sufficient. However, existing hybrid tracking solutions primarily focus on sensor-level data forwarding or position estimation, while limited attention is paid to how heterogeneous sensor data can be systematically combined to represent higher-level process states. In many industrial use cases, material tracking is inherently a multi-sensor problem, requiring the joint interpretation of identification, proximity, and interaction events rather than isolated measurements.

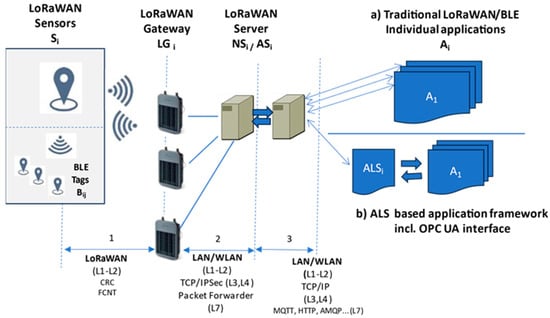

This limitation is illustrated by the traditional architecture shown in Figure 1a, where multiple independent applications process sensor data according to individual business logics. Sensors are logically grouped by application, which restricts interoperability and complicates the realization of integrated, cross-domain use cases. To address this gap, this paper proposes an Associated LoRaWAN Sensor (ALS) model, illustrated in Figure 1b. The ALS model introduces an application-layer abstraction that logically associates LoRaWAN sensors (Si) with BLE tags (Bij) and a magnetic sensor into virtual entities representing tracked material carriers. Instead of exposing raw measurements, the ALS framework provides pre-processed and semantically enriched information, including process-relevant states, events, and alarms derived from multi-sensor fusion.

Figure 1.

Proposed IT architecture with ALS application framework concept.

By shifting the focus from position-centric localization to process-aware sensor association, the proposed approach enables reliable validation of material–machine interactions without requiring high-precision localization infrastructure. The ALS framework further exposes its outputs through a standardized API, allowing integration with external systems; for industrial deployments, OPC UA is recommended.

The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

- Definition of an associated LoRaWAN sensor model, enabling logical grouping of heterogeneous IoT sensors for various business use-cases, e.g., material tracking;

- A process-oriented, or process-aware sensor association, that enables reliable validation of material while using BLE tag localization.

- Experimental validation of the proposed model using commercially available BLE and LoRaWAN devices in an industrial-like environment.

2. Background and Related Work

Material flow tracking (MFT) in manufacturing aims to provide continuous visibility of material carriers and their interactions with production resources, enabling process validation, traceability, and logistics optimization [7]. Existing approaches range from basic identification technologies to advanced localization systems.

2.1. Established Technologies for Material Tracking

Traditional identification methods, such as barcode and QR code scanning, are widely used due to their low cost and simplicity; however, they provide only discrete, operator-dependent information and are unsuitable for automated real-time monitoring. RFID-based systems improve automation but remain sensitive to metal environments or require battery-powered active tags, increasing maintenance demands. More advanced solutions are represented by Real-Time Locating Systems (RTLSs) employing UWB, Wi-Fi, 5G, or vision-based techniques. These systems achieve high positioning accuracy using methods such as Time of Flight (ToF), Time Difference of Arrival (TDoA), or Angle of Arrival (AoA), but require dense anchor infrastructures, continuous power supply, and careful calibration, leading to high deployment and operational costs. Consequently, RTLS solutions are often economically unjustifiable for medium-sized enterprises or legacy production lines, particularly when centimeter-level accuracy is not required [2,4].

2.2. Hybrid IoT-Based Tracking Approaches

Research and industrial practice are increasingly exploring hybrid IoT architectures combining short-range sensing technologies with long-range, low-power communication. Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) enables low-cost and energy-efficient object tagging with zone-level proximity detection, while LoRaWAN, as a representative LPWAN technology, provides long-range and infrastructure-light data transmission suitable for large industrial areas [8,9,10]. Hybrid BLE–LoRaWAN systems typically use BLE as a local sensing and identification layer, while LoRaWAN acts as a backhaul network for transmitting aggregated sensor data to a central server. This architecture reduces infrastructure density compared to RTLS solutions and is therefore attractive for large halls, warehouses, and outdoor industrial sites. Existing studies and commercial deployments confirm the technical feasibility of this approach for asset tracking and monitoring applications [5,11].

However, most existing hybrid solutions focus primarily on forwarding sensor measurements or estimating coarse asset positions, while the interpretation of heterogeneous sensor data at the process level remains largely application-specific and ad hoc. Scientific literature provides limited discussion on how multiple sensor modalities can be systematically combined to represent higher-level manufacturing states [2,8,9].

2.3. Research Gap and Motivation

While hybrid BLE–LoRaWAN systems reduce infrastructure costs and energy consumption, they lack a formalized application-layer mechanism for associating heterogeneous sensors and deriving process-oriented events from their combined outputs. In practical manufacturing scenarios, reliable validation of material–machine interaction often requires multi-sensor reasoning rather than precise continuous localization.

This work addresses this gap by introducing an Associated LoRaWAN Sensor (ALS) model, which enables logical grouping of heterogeneous sensors into a single virtual entity representing a tracked material carrier. The ALS supports event-based state detection and process validation, shifting the focus from position-centric localization to process-aware tracking.

3. Technology Background: BLE and LoRaWAN for the Associated Sensor

3.1. LoRaWAN Overview

LoRaWAN is a low-power wide-area network protocol (LPWAN) designed for long-range communication with minimal energy consumption. It operates in sub-GHz ISM bands, achieving communication over several kilometers in industrial and outdoor environments. End devices communicate with gateways in a star topology, and messages may be received by multiple gateways, improving robustness and reliability [10,12].

From a system perspective, LoRaWAN serves as a scalable and energy-efficient transport layer for ALS-related events, enabling reliable communication without the need for dense network infrastructure. Its support for battery-powered devices with a multi-year lifetime makes it particularly suitable for industrial tracking applications. The role of LoRaWAN within the proposed ALS-based application framework is illustrated in Figure 1, which highlights the interaction between LoRaWAN sensors, gateways, backend services, and the application-layer association logic.

3.2. BLE and iBeacon Overview

Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) is widely used for low-power, short-range localization in industrial IoT applications [8,9,13]. BLE beacons are small devices that transmit signals at regular intervals according to defined protocols. The two most common protocols are iBeacon and Eddystone, with iBeacon developed by Apple Inc., Los Altos, Kalifornia in 2013. While the exact data format may vary slightly across manufacturers, all iBeacons share core elements ensuring interoperability, as illustrated in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

iBeacon format [13-BLE].

- Universally Unique Identifier (UUID): a 128-bit unique identifier for each beacon or group;

- Major and minor numbers: used to group beacons into areas or zones;

- Measured power: indicates transmitting power, used to estimate distance.

These elements enable applications to define monitoring areas, detect entry/exit events, and differentiate locations. Proximity estimation is typically categorized into four states: immediate, near, far, and unknown. Interaction with beacons requires a compatible application installed on the receiving device, supporting motion monitoring and ranging. BLE beacons provide zone-level localization, sufficient for many MFT applications, and battery life can be optimized through adaptive scanning and advertising strategies [8,9].

4. System Architecture and Methodology

This section describes the research objective and methodology underlying the proposed Associated LoRaWAN Sensor (ALS) model. The objective is to design and validate an application-layer mechanism that enables process-oriented material tracking by associating heterogeneous IoT sensors within a hybrid BLE–LoRaWAN architecture.

Our approach uses the LoRaWAN network as a communication backbone for connecting LoRaWAN sensors that are capable of scanning BLE tags (iBeacon). The LoRaWAN network provides wide-area coverage and typically requires only two–three LoRaWAN gateways to fully cover a standard industrial site. The LoRaWAN infrastructure thus acts as an integration platform for both LoRaWAN and BLE devices. The overall architecture is shown in Figure 1. All LoRaWAN devices/sensors can communicate (1) through LoRaWAN gateways (LGi), which are connected to a LoRaWAN network server (NSi) via TCP/IP using the packet-forwarder protocol (2). Received LoRaWAN up-link data can be provided by the LoRaWAN application server (ASi) via supported IoT protocols, such as MQTT (3), or HTTP REST.

In practice, sensor payloads are encoded using the vendors’ specific up-link formats, which necessitates the use of dedicated payload decoders for each specific sensor type and manufacturer required, either on the LoRaWAN application server side or directly within the application itself. Having received sensor data (Si), which is processed by decoders, a dedicated application (Ai) can execute use-case-specific business logic, such as material tracking and localization based on combined LoRaWAN and BLE data. Each application typically maintains a separate connection to the application server via the selected protocol (e.g., MQTT, AMQP, OPC UA, or HTTP).

In the traditional architecture illustrated in Figure 1a, multiple independent applications process sensor data according to isolated business logics. As a consequence, sensors are logically grouped by application, which limits interoperability and complicates the realization of cross-domain use cases. To overcome this limitation, an Associated LoRaWAN Sensor (ALS) model is proposed. The ALS model integrates LoRaWAN sensors (Sij) with BLE tags (Bij) and provides pre-processed, semantically enriched sensor information to end applications. This application-layer abstraction simplifies application development while enabling advanced multi-sensor integration for complex industrial scenarios. Additionally, an application programming interface (API) is provided, enabling the consumption of enriched data, events, and alarms by external systems or direct integration into manufacturing processes. For industrial deployments, OPC UA is recommended.

4.1. Associated LoRaWAN Sensor (ALS) Model

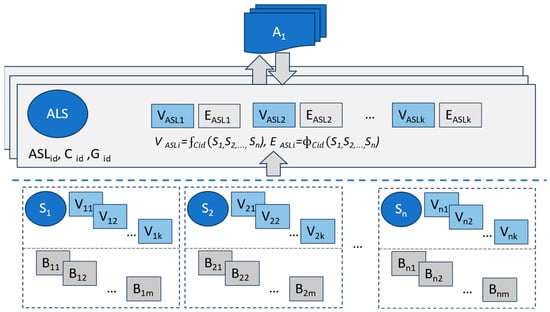

The proposed associated LoRaWAN sensor model (ALS) is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Associated LoRaWAN sensor (ALS) model.

The LoRaWAN application server (AS) provides data from n-sensors, which can be formally expressed as (1):

Each physical sensor (Si) produces its own set of measured values (Vij), such as temperature, motion detection states (0 or 1), or scanned BLE tag identifiers (m), such as iBeacons (Bij), as expressed by (2):

Each BLE tag (Bij) corresponds to an iBeacon identifier consisting of UUID, Major ID (M1), Minor ID (M2), and Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI), as described in chapter 1 with Figure 2. Then the iBeacon structure can therefore be defined as in (3):

By aggregating data from multiple sensors, the ALS model enables higher-level reasoning through application-specific business logic, producing derived values, events, and alarms. To support a generic and reusable framework, a logical group of LoRaWAN sensors (S1, S2, …, Sk) is represented by a single associated logical sensor (ALSi). Each ALS belongs to a specific application class (Cid) and application group (Gid). The ALS model is formally defined as follows.

Data collected from all available sensors creates an opportunity to process their values according to an assigned business logic and create the added information, events, or trigger alarms. To offer a generic model, a logical group of LoRaWAN sensors (S1, S2, …, Sk) shall be represented by an assigned associated logical sensor (ALSi). Each associated sensor can belong to a different application class with a specific business logic (Cid) and application group (Gid). The ALS model introduces an abstraction layer in which multiple physical sensors are represented as a single logical entity with defined state and event semantics. The associated LoRaWAN sensor model can be defined according to formula (4):

where VALSi denotes the processed values derived from the associated sensors (S1, S2, …, Sk) and EALSi represents events triggered according to a predefined state model. The transformation of raw sensor data into ALS values and events is fully dependent on the defined application logic associated with a given application class. This transformation can be formally expressed using the generic functions (), for both cases can be formally defined by Formulas (5) and (6):

where a logical group of LoRaWAN sensors, with assigned identifier ALSi, includes associated sensors Si, Sj, and Sk. In this case, the model provides pre-processed data in the form of the results derived from sensor values and BLE tag IDs. This model can even generate events EALS1 and additional data VALS1 beyond the data received from the LoRaWAN sensors. An example of two independent associated LoRaWAN sensor groups is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Use case 1—tag-based localization; traditional LoRaWAN/BLE implementation.

This abstraction enables ALS entities to deliver pre-processed, context-aware information rather than raw sensor readings, thereby decoupling application logic from low-level sensor handling.

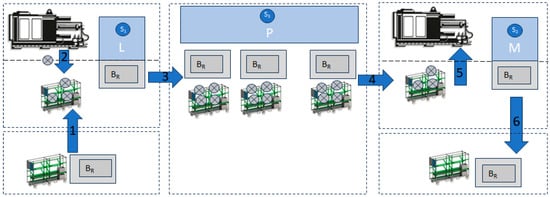

4.2. Validation Use Case: Material Tracking and Validation

To validate the proposed ALS model, there is a necessity to formalize the transformation functions according to a specific business use case. A simplified material tracking and localization use case with a material flow is therefore selected, as illustrated in Figure 4. In this scenario, material produced by a source production stage machine L (loader) must be transported to a target production stage machine M (feeder), where a material is consumed during the subsequent production of the next article from the input material. The material must be temporarily stored in a transport unit called R (rack). An empty rack must first be connected to the source production machine (1) so that the produced material can be loaded into the rack (2). As soon as the rack is full, it must be disconnected from the machine and moved to the temporary storage area (3). Whenever the target machine needs input material, the rack with the requested material is removed from temporary storage (4) and delivered to the target machine (5). When all material in the rack has been used and unloaded, the empty rack is disconnected from the target machine and delivered to the source machine again (6). Material localization and validation, based on a hybrid solution LoRaWAN/BLE, can be addressed by two different use cases: use case 1 and use case 2.

Use Case 1—BLE tag-based localization (Figure 4) represents a traditional approach in which all racks are equipped with BLE tags (BR), while LoRaWAN sensors are installed only at machines (L, M) and the warehouse (P). These sensors scan nearby BLE tags and forward the detected identifiers via the LoRaWAN network. Tags are filtered by UUID and sorted according to RSSI. However, when multiple racks are located within the same proximity zone, RSSI-based ranking may be ambiguous, potentially leading to incorrect rack identification and process validation errors.

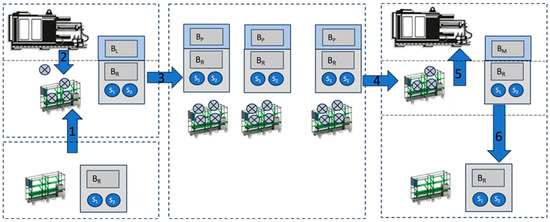

Use Case 2—BLE tag-based localization with associated LoRaWAN sensors (Figure 5) addresses this limitation by applying the proposed ALS model. In this case, each rack is represented by an individual ALS entity, combining BLE scanning data with additional physical sensor inputs. It means that each rack will have associated one LoRaWAN sensor with BLE scanning (S1) and another one for the detection of magnetic switch (S2). All in all, each LoRaWAN sensor can scan a maximum of three BLE tags in time (B11, B12, B13), sorted by RSSI value. Let us assign the ALS model for use case 2 according to (7):

where

- V11—LoRaWAN sensor (BLE scanner) status;

- V12—LoRaWAN sensor (BLE scanner) battery level;

- B11—iBeaconBLE tag with strongest RSSI;

- B12—BLE tag with the second strongest RSSI;

- B13—BLE tag with the third strongest RSSI;

- V21—LoRaWAN sensor (magnetic switch) status code;

- VALSi—BLE tag logical name (Tag_Rx-rack, Tag_Px-storage, Tag_L/Mx-machine);

- EALSi—triggered event associated with rack status (loading, storing, unloading).

Figure 5.

Use case 2—tag-based localization with associated LoRaWAN sensor groups.

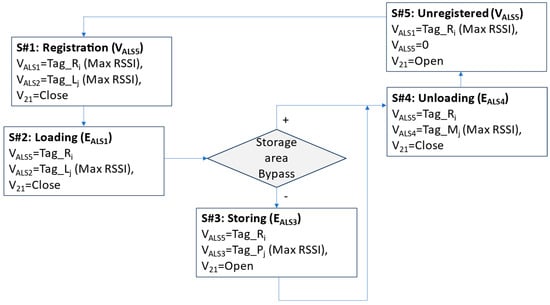

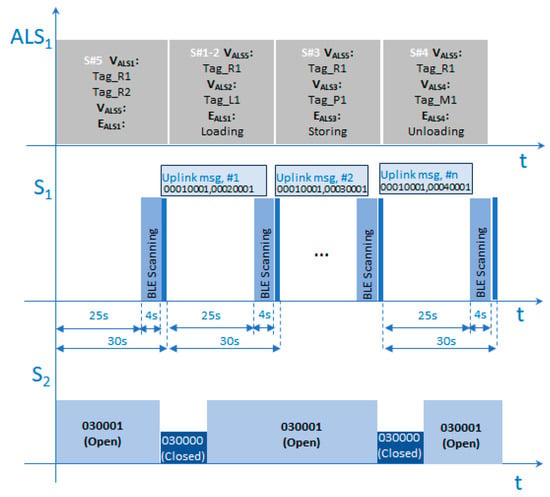

In addition, the ALS concept can also be represented using a state-based model, where each state S#id (registration, loading, storing, unloading, unregistered) has assigned exact values VALSi and events EALSi, as illustrated in Figure 6 and explained in experimental chapter 6, instead of formal definitions for transformation functions ().

Figure 6.

Associated LoRaWAN sensor (ALS) model with state diagram.

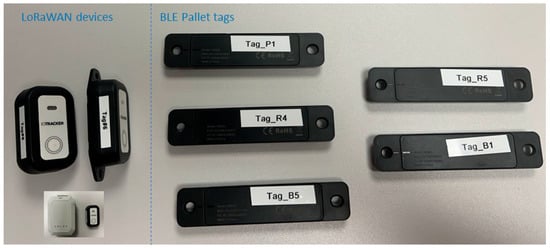

5. The Setting of the ASL Application, Sensors, and BLE Tags for the Experiment

In order to validate our associated LoRaWAN sensor model, we had to select appropriate tags and sensors, which would be supporting both protocol stacks LoRaWAN and BLE. For our testing, the following devices were configured and used; see Figure 7:

Figure 7.

Example of used devices—LoRaWAN sensors (IoTracker3, WS3901) and BLE Trax10229.

- A multi-sensor IoT tracker (IoTracker 3)—LoRaWAN/BLE;

- WS3901—LoRaWAN magnetic contact switch;

- Trax10229—rugged pallet BLE beacon.

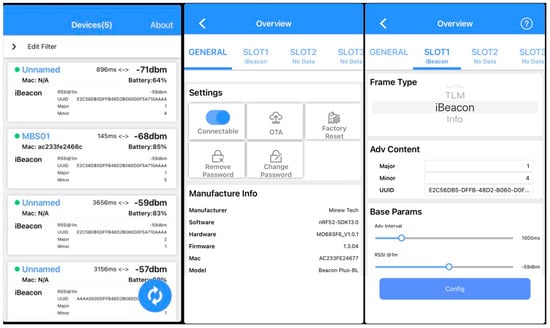

The configuration of BLE sensors is shown in Figure 8. Each BLE Tag has a BlueTooth MAC address and BLE_ID (iBeacon). iBeacon ID was assigned as follows:

Figure 8.

Configured BLE tags—Trax10229.

- UUID: tag vendor (16 B)—*********AAAA;

- Major: tag class (2 B)—0001 (Tag_R), 0002 (Tag_L), 0003 (Tag_P), 0004 (Tag_M);

- Minor: tag no (2B)—0001(Tag_R1),0002(Tag_R2).

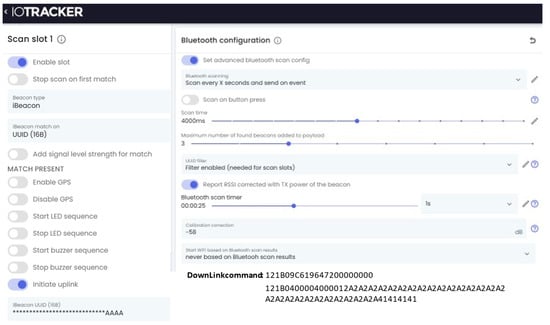

IoTracker 3 configuration is shown in Figure 9. This multi-sensor offers not only the LoRaWAN connection for sending the measured sensor’s values but also additional GPS and Bluetooth configurations. The BLE setting for our experimental test case includes regular scanning every 25 s, with a scanning time of 4 s. The device is configured with filtering according to UUID with the fixed prefix “AAAA”; therefore, only our BLE tag Trax10229 will be scanned and data from the minor and major prefix and RSSI will be transferred within the LoRaWAN up-link message to the application.

Figure 9.

Configuration of IoTracker3 LoRaWAN sensors—BLE parameters.

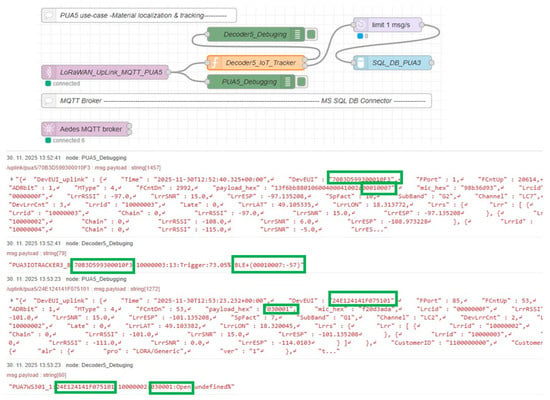

For testing, we used an existing LoRaWAN network, which was adjusted and configured for our selected sensors. Also, we have used Node-RED as an open-source tool, based on the Node.js framework, using visual programming and supporting various protocols (MQTT, HTTP/HTTPS, TCP/UDP, AMQP, CoAP). Node-RED’s main characteristic is that it is intended for rapid development and prototyping. It uses internal MQTT broker (Barebone MQTT broker Aedes), along with the necessary decoders (Decoder5_IoT_Tracker) and a database connector (SQL_DB_PUA3) for storage of all decoded up-link messages. The LoRaWAN application server (Actility ThingPark OCP) was connected to our application MQTT broker via an internal MQTT client (Publisher, Subscriber). The application itself read LoRaWAN up-link messages from the internal MQTT broker via an internal MQTT client in subscriber mode (LoRaWAN_Up-Link_MQTT_PUA5). In addition, there are specific debugging nodes to check received LoRaWAN up-link messages from the MQTT broker (PUA5_Debugging) and show decoded data from sensors (Decoder5_Debugging).

Figure 10 shows examples of up-link messages for both types of sensors. The DevEUI identifier of the specific sensor and essential up-link data (payload_hex) are highlighted in color. In the case of the IoTracker3 sensor, these are BLE iBeacon identifiers (major: 0001, minor: 0007), and the decoder (Decoder5_Debugging) extracts them for processing by the application prior to saving them to the database. The data from the second sensor, WS301, is shown as well with color marking, where the open magnetic contact (open) is coded in payload_hex as “03001”. Conversely, the closed contact (close) would be evaluated in payload_hex as “03000”.

Figure 10.

Node-Red decoders and debugging of LoRaWAN up-link messages.

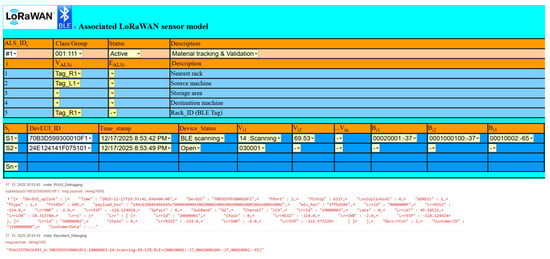

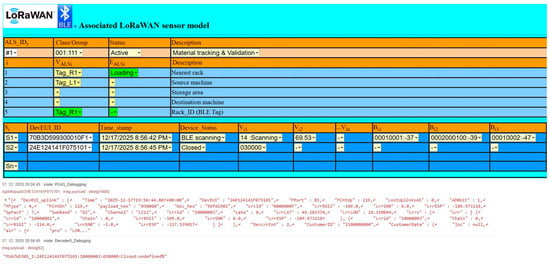

In order to illustrate the ALS model during our experiments, we have prepared a simple application to provide visualization of the ALS model with associated LoRaWAN sensors (Si), the sensor’s values (Vij), and BLE tags (Bij). In addition, ALS values (VALSi) and events belonging to the state diagram (EALSi) are included, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Associate LoRaWAN sensor model visualization.

6. Experimental Validation

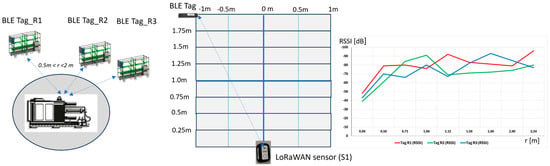

To verify the new model, we conducted at least partial testing of conditions close to the desired case. Within the material flow, the position of the racks relative to the machines was critical. The simulated conditions corresponded to real spatial constraints. In our case, there can be a maximum of three racks per machine and no more. The closest one at a distance of 0.5 m from the material feeder and no further than 2 m from the machine, where there is already a transport corridor. These conditions are visualized in Figure 12. Therefore, all tests were executed in exact positions: ±1 m on the left and right side of the feeder and distance from feeder (position of LoRaWAN sensor) was min. 0.5 m and max. 2 m.

Figure 12.

Setting of the testing condition—layout of BLE tag positions.

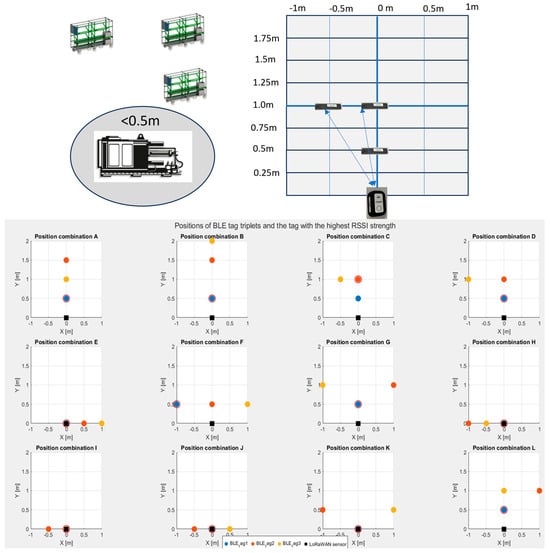

An even more important experiment was to test the probable geometric arrangements (tag positioning) of the racks relative to each other and the machine input feeder. In total, we tested the 12 most common combinations of tag positions (marked as A, B, …, L scenarios) according to the location of the racks, as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Testing of tag localization for use case 1—rack positioning.

We recorded RSSI values from three tags—Tag_R1 (1:1), Tag_R2 (1:2), Tag_R3 (1:3)— and, using MATLAB 2022, identified the candidate with the highest RSSI, being the red marked circle for the selected scenario. The measurement shows that while tag-based localization works for most scenarios, it can fail at distances below 1 m. In our testing case, there were three scenarios where the RSSI value did not reflect the real position (nearest) to the machine with the LoRaWAN sensor (scenario: C, F, and I; failure rate: 20%). This confirmed that traditional BLE localization is unreliable for material validation when several racks are in close proximity. These results justified our ALS approach, which combines a traditional LoRaWAN BLE scanner sensor with a LoRaWAN magnetic switch. For material validation (loading/unloading), an additional confirmation signal is necessary to verify that the rack reached the source or target machine (Tag_Lx, Tag_Mx).

To validate our model, we re-tested the three racks using the transformation function and state diagram, as shown in Figure 14. The LoRaWAN sensor S1 scans BLE tags periodically every 25 s, and the scanning time is set to 4 s. In the case of detection of a BLE tag, the sensor consequently sends an up-link message containing the scanned iBeacon identifiers sorted by RSSI. The number of iBeacon identifiers in one up-link message is limited to three, according to the assumptions explained in use case2. This setting then generates regularly up-link messages with a period of 30 s. In addition, LoRaWAN sensor S2 is checking the status of the magnetic switch; while it was open, the last up-link message contained the value “030001”. As soon as the magnetic switch is closed, the up-link message is sent containing the value “030000”. The Associated LoRaWAN Sensor (ALSi) combines the values of both sensors and calculates from sensor values the new logical values VALSi and events EALSi. The experiment starts with two BLE tags in proximity to S1 (0001001, 0001002), which are translated by ALS1 as Tag_R1 and Tag_R2. Then the carrier is moved to the vicinity of the source machine L1, identified by the tag (00020001, Tag_L1). Once the carrier is inserted into an output material loader and the magnetic switch is closed, then the carrier is registered as VALS5 = Tag_R1 (00010001), and event EALS1 = “Loading“ is generated. The process continues after the carrier is moved from source machine L1 to storage position P1. ALS recalculates values VALS3 = Tag_P1 (00030001) and generates event EALS3 = “Storing”. Finally, when the rack is moved from storage to the destination machine M1, the magnetic switch is closed. ALS recalculates values VALS4 = Tag_M1 (00040001) and generates event EALS4 = “Unloading”, while the carrier is unregistered VALS4 = “”.

Figure 14.

Explanation of state ALS model in experimental validation for use case 2.

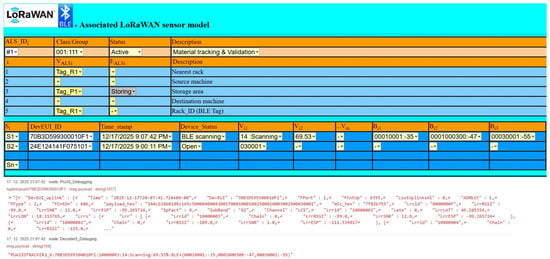

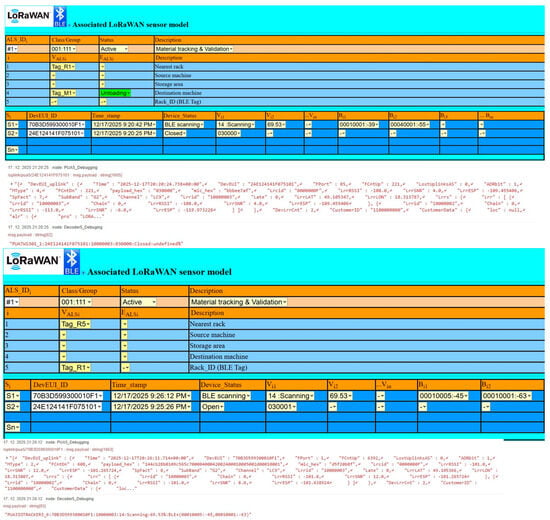

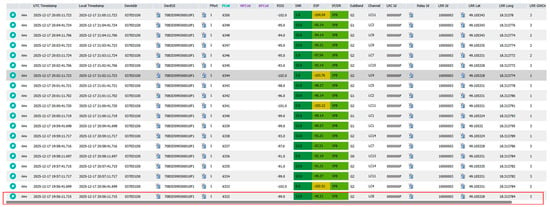

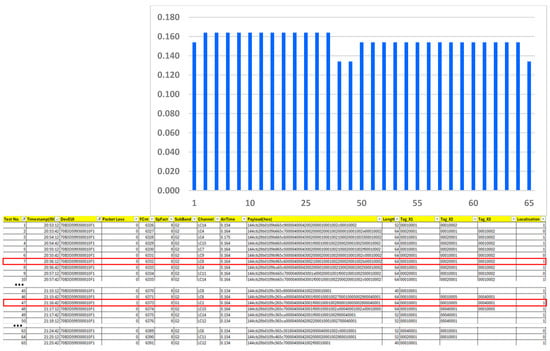

During experimental validation, all results were documented by recorded LoRaWAN up-link messages, including decoder results and visualization of the ALS model, as shown in Figure 15 and Figure 16.

Figure 15.

Testing of associated sensor model for material validation and material loading.

Figure 16.

Testing of the associated sensor model for material validation and material loading.

Figure 15 shows our testing results for material validation, where the racks Tag_R1 and Tag_R2 were correctly localized, and the magnetic switch signal (open- > close) triggered an event “Loading” that associated Tag_R1 with sensor S1 for the next steps.

After loading the rack and disconnecting it from the machine (the magnetic switch is again in the open position), the rack is moved to the storage area and stored, which can also be seen in the second example in Figure 15. In any case, after registration, the rack already has a permanently assigned BLE tag (Tag_R1), which is used in the next steps.

After a certain time, the rack is removed from storage (Tag_P1) and brought to the target machine with the tag (Tag_M), as shown in Figure 16. After identifying the machine tag (Tag_M1) and connecting to the machine (feeder), the magnetic switch is closed again, which is evaluated as a material unloading event, and the rack is also deregistered. The whole process can be repeated.

In addition, we also simulated the case of close rack positions, with the case of falsely assessing that rack Tag_R5 is closer to the S1 rack sensor than the original rack Tag_R1. In this case, the rack is already registered to the associated sensor ALS#1, so this case has no impact on the validation, which remains unchanged. This process is illustrated in the second part of Figure 16.

Examples of LoRaWAN up-link messages from the Actility ThingPark OCP server are shown in Figure 17, and the marked message (Counter Fcnt: 6332) is linked with the ALS model processed experimental values in Figure 18.

Figure 17.

Example of LoRaWAN up-link messages from experimental validation of ALS model.

Figure 18.

Example of processed test data with graph of LoRaWAN up-link message air time.

In total, we processed 65 LoRaWAN up-link messages during the experiment, as shown in Figure 18, including a graph with the LoRaWAN up-link message air time. Only one message (FCnt: 6372) was lost during the experiment (marked in the table in Figure 18), which gives a packet loss of 1.5%. Since we limited the maximum number of iBeacon identifiers to three, according to our use case 2 case, the length of the messages ranged between 40 and 60 characters, which influenced the up-link message air time as shown on the graph. Similar to use case 1, we noticed a localization error according to RSSI, when instead of the nearest tag, Tag_R1 (00010001), the machine tags Tag_L1 (00020001), Tag_M1 (00040001) appeared first, as shown in Figure 18; however, the ALS model kept localization without failure due to the registration process and the magnetic switch sensor. Table 1 summarizes all statistics from our ALS model experimental validation.

Table 1.

Statistics from experimental ALS model validation.

7. Discussion

The results of this work highlight the advantages of using associated LoRaWAN sensors combining LoRaWAN and BLE technologies for material tracking and validation in industrial environments. Compared to a traditional single-sensor approach (use case 1), which relies solely on BLE scanning within one LoRaWAN device, the proposed model with ALS (use case 2) demonstrates that a logical grouping of heterogeneous sensors can provide sufficient process-relevant localization while reducing cost, energy consumption, and complexity.

Key observations include the following:

- Precision vs. process requirements: Traditional solutions based on LoRaWAN sensor with BLE scanning offer only approximate RSSI-based localization. However, most material-tracking tasks in manufacturing require reliable presence detection, movement tracking, and validation of material connection to the machine rather than exact positioning. The proposed ALS model achieves 0.7–1.5 m accuracy, which is sufficient for process-relevant monitoring.

- Infrastructure and scalability: Minimal infrastructure (one–three LoRaWAN gateways) covers entire industrial sites in both use cases. However, the ALS model provides higher robustness by combining two complementary sensors, increasing reliability without adding infrastructure complexity.

- The ALS model shifts the focus from position-centric localization to process-aware sensor association, and the proposed approach enables reliable validation of material–machine interactions without requiring high-precision localization infrastructure.

- Process-oriented tracking: Logically associating two heterogeneous sensors, the ALS model enables event-driven monitoring, connection validation, and direct support of production workflows, whereas the single-sensor approach focuses only on raw BLE presence detection without the ability to confirm material readiness or machine connection.

The comparison in Table 2 illustrates that use case 1 provides a simple and low-cost approach for basic BLE-based detection. However, its reliance on a single sensor limits robustness and prevents machine-connection validation, which is critical for many material flow processes.

Table 2.

Comparison of Use Cases.

In contrast, the ALS model (use case 2) provides a more balanced trade-off: while it requires two sensors, it offers significantly higher reliability, supports event-driven logic, reduces false detections, and enables validation of the transport unit connection prior to material consumption. This makes ALS particularly suitable for medium-sized plants and flexible production layouts.

Limitations and future implications: The ALS solution cannot replace high-precision real-time systems in applications requiring sub-second response times or exact spatial coordinates. However, its ability to associate multiple low-cost sensors into a single logical entity enables scalable and sustainable deployments.

Future research may explore hybrid sensor integration, improved BLE-based positioning, enhanced association logic, MES/ERP integration, and predictive analytics to further support Industry 4.0 applications.

8. Conclusions

Based on the proposed model of associated sensors, we conclude that the concept successfully confirms the validity of the approach. Unlike traditional solutions relying on a single LoRaWAN sensor performing BLE scanning, our approach creates a logical model tailored to the needs of a specific process, enabling multi-sensor association, event-driven logic, and process-relevant validation.

The main findings of our work can be summarized as follows:

Firstly, we have selected LoRaWAN as the backbone protocol for the integration of various sensors within an associated logical group. LoRaWAN provides sustainable long-range communication technology, mitigating the necessity of extensive hardware installation with multiple active components, required powering and connections via a LAN/WLAN network in contrast to traditional technologies. On the contrary, LoRaWAN can cover entire industrial areal just by 1-3 LoRaWAN gateways.

Secondly, we created an abstract sensor model that supports not only the sensor’s own data but also detected BLE tag data (iBeacon) as a basis for tag-based localization. The model also incorporates event logic and aggregated outcomes, allowing the application layer to focus on process states rather than individual sensor values.

Thirdly, we validated the theoretical model using a defined use case for material localization and tracking, demonstrating the system’s ability to verify that a transport unit with material is physically connected to the machine. In our experimental setup, the model integrated two sensor types. While the first sensor (IoTracker3) provided BLE-based localization, the second sensor ensured accurate validation of the physical connection, enabling reliable process control.

The proposed Associated LoRaWAN Sensor (ALS) model was verified and validated on selected use case 2 with the following results:

- The proposed architecture is limited by performance restrictions of LoRaWAN technology (latency, data throughput). It can therefore be applied for business processes with a slower dynamic (refresh time/update time ~20–30 s) while benefiting from simple infrastructure coverage. Therefore it cannot be used for control systems, machine control (PLCs), and material flow systems with very low latency (<1 s). On the contrary, it is very useful for a variety of integrated solutions when there is a need to combine various sensors and create a framework for various applications, such as material tracking, material validation, warehousing, device tracking, user tracking, tracking of objects (AGVs, trucks, …) etc.

- Up-link decoders were able to process application up-link protocols and transform data into the ALS logical sensor model.

- Processed data and events generated by the model worked accurately and confirmed real material movement.

- Machine-connection validation met all requirements, enabling both localization and pre-consumption validation.

- BLE-based localization achieved 0.7–1.5 m accuracy, sufficient for the supported process, which was acceptable by the supported process, providing the cost and sustainability of installation.

- The combination of two sensors mitigated the issue with BLE tag accuracy and enabled material validation by using a very cheap and sustainable approach, which would not be possible if using traditional use case 1, with just one LoRaWAN sensor.

The comparison between ALS and the traditional single-sensor approach demonstrates that ALS provides a more flexible, robust, and process-oriented solution for material tracking. It achieves sufficient accuracy for material flow applications, requires minimal infrastructure, supports event-driven logic, and remains particularly suitable for small- and medium-sized enterprises.

Overall, the results show that associating multiple LoRaWAN + BLE sensors into a unified logical entity significantly improves system robustness, reduces the limitations of BLE-only tracking, and enables new opportunities for process-centric monitoring and validation.

However, the association of multiple low-cost sensors into one logical model is the key novelty of this work.

Finally, the findings should be interpreted within the context of previous work and underlying hypotheses. Broader implications and directions for future research include advanced analytics, hybrid localization techniques, and integration with higher-level industrial information systems.

Author Contributions

The work presented in this paper was carried out in collaboration with all authors. P.P. defined the research topic, guided the research goals, and performed the experiments. E.B. and A.K. created the figures and conducted the formal analysis. E.B. and A.K. wrote the theoretical part and edited and reviewed the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by VEGA through the Research on motion data analysis methods for applications in diagnosis and therapy of gnostically relevant symptoms under Grant 1/0147/25.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, D.; Zheng, L. Optimizing Information Flow in Manufacturing Operations Management Through Lean–Industry 4.0 Integration. Eng. Manag. J. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafari, F.; Gkelias, A.; Leung, K.K. A Survey of Indoor Localization Systems and Technologies. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2568–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sammak, K.A.; Al-Gburi, S.H.; Marghescu, I.; Drăgulinescu, A.-M.C.; Marghescu, C.; Martian, A.; Al-Sammak, N.A.H.; Suciu, G.; Alheeti, K.M.A. Optimizing IoT Energy Efficiency: Real-Time Adaptive Algorithms for Smart Meters with LoRaWAN and NB-IoT. Energies 2025, 18, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küpper, C.; Rösch, J.; Winkler, H. Use of real time localization systems (RTLS) in the automotive production and the prospects of 5G—A literature review. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2022, 10, 840–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.S.; Abdullah, M.; Riaz, S.; Alvi, A.; Rustam, F.; Flores, M.A.L.; Galán, J.C.; Samad, A.; Ashraf, I. A Survey on the Role of Industrial IoT in Manufacturing for Implementation of Smart Industry. Sensors 2023, 23, 8958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LoRa Alliance. LoRaWAN Specification 2023. Available online: https://resources.lora-alliance.org/document/lorawan-specification-v1-0-3 (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- Čamaj, J.; Bulková, Z.; Gašparík, J. Material Flow Optimization as a Tool for Improving Logistics Processes in the Company. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, A.A. On the accuracy of BLE indoor localization systems: An assessment survey. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 118, 109455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, F.; da Rocha, H.; Laracca, M.; Ferrigno, L.; Espírito Santo, A.; Salvado, J.; Paciello, V. BLE-Based Indoor Localization: Analysis of Some Solutions for Performance Improvement. Sensors 2024, 24, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Raza, U. Low power wide area networks: An overview. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 19, 855–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Hu, X.; Gao, Z.; Hu, J.; Chen, L.; He, Z.; Pei, L.; Chen, K.; Wang, M.; et al. Toward Location-Enabled IoT (LE-IoT): IoT Positioning Techniques, Error Sources, and Error Mitigation. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 4035–4062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, V.; Campoverde, B.; Yoo, S.G. A Systematic Literature Review of LoRaWAN: Sensors and Applications. Sensors 2023, 23, 8440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE): A Complete Guide. Available online: https://novelbits.io/bluetooth-low-energy-ble-complete-guide/ (accessed on 6 September 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.