Abstract

The CO2 capture process in coal-fired power plant flue gas still faces the difficulties of low material performance and high energy and cost consumption. It is necessary to develop new capture solvents and materials, and also new capture process configurations, to achieve breakthroughs in capture performance and process technology. In various process configurations for CO2 absorption, lean solution vaporization and compression (LVC) is a commonly used and effective one for reducing the energy and cost consumption. This work propose a partial lean solution vaporization and compression (PLVC) configuration to decrease energy and cost consumption for CO2 capture, considering the price difference in heat and electricity with the high prices of compressors. The three heat exchange methods of no heat exchange, separate heat exchange, and merged heat exchange for lean solution after flash evaporation are also proposed with PLVC, which could be used in the range of low (0–25%), middle (25–75%), and high split ratios (75–100%) of lean solution for the lowest total heat consumption of the aqueous AMP + PZ solvent. Therefore, the comprehensive cost of the capture process can be minimized by considering different prices of steam heat, electricity, and compression facility.

1. Introduction

The emission of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2) is a major factor causing climate change, but there are still high energy consumption and cost issues in capture, which affect the large-scale promotion and usage. The large amount of industrial flue gas emitted from coal-fired power plants and other sources contains 5% to 30% CO2, while other gases mainly consist of N2, O2, and H2O. The chemical absorption method, as one of the most important methods of carbon capture technology for post-combustion fuel gases, generally has the advantages of technological maturity, large scale, and relative low cost. It adopts the absorption–desorption process, which has the characteristics of high removal efficiency, fast absorption rate, and easy integration with coal-fired power plants. However, traditional absorbents and processes still face the bottleneck problem of high energy consumption and costs of investment and operating that could be further reduced. It is important to develop more efficient new absorbents and new processes to reduce energy consumption and cost for CO2 capture [1].

At present, the solvents widely used for capturing CO2 in the industry are mainly chemical absorption solvents such as organic alkanol amines and inorganic salts. Monoethanolamine (MEA), diethanolamine (DEA), 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (AMP), diisopropanolamine (DIPA), and methyl diethanolamine (MDEA) are commonly used organic alkanol amine solvents. In order to improve the absorption rate of CO2 by the absorption solution, solvents with fast absorption rates such as piperazine (PZ) are added to form a mixed solvent with high absorption capacity and fast absorption rate, which can reduce the energy consumption and cost of CO2 capture. More new solvents and phase exchange solvents are also studied to increase CO2 solubility and reduce absorption reaction enthalpy [2,3,4].

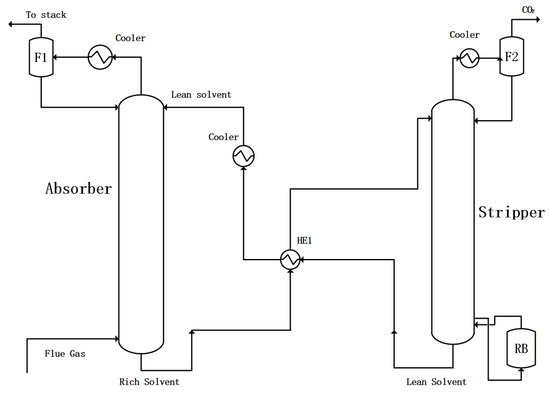

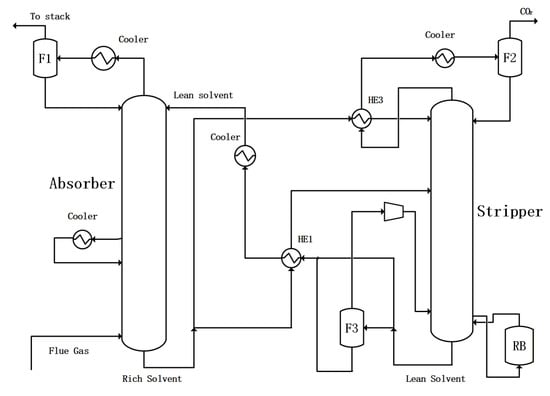

In addition to improving solvents, innovation in the absorption process configuration is also key to reducing energy consumption and cost for CO2 capture. The simplest absorption process configuration for CO2 capture includes fuel gas pretreatment, absorption, purified gas cooling and flashing (F1), heat exchange (HE1) between lean and rich solutions, heating desorption with a reboiler (RB), regenerated gas cooling with flashing (F2), and lean liquid cooling, as seen in Figure 1. Based on the simplest configuration, the following process improvements have been proposed to significantly reduce the energy consumption for CO2 capture [5,6].

Figure 1.

The basic configuration for CO2 capture with the absorption method.

Absorber inter-cooling (AIC) is a widely recognized improved configuration [7,8,9]. Cooling inside the absorption tower refers to extracting most or all of the liquid from about the middle of the absorption tower, cooling it through heat exchange equipment, and then returning it to the absorption tower. Cooling devices can also be directly added to the corresponding position of the absorption tower. Due to the exothermic nature of CO2 absorption, the temperature rise inside the absorption tower is not conducive to absorption, reducing the solvent absorption efficiency, increasing the circulation of solvent, and increasing the energy consumption of the reboiler of the desorption tower. By cooling liquids and gas phases in the absorption tower, the temperature of the absorption tower decreases, which increases the absorption capacity of the solvent, reduces the amount of solvent used, and lowers the capture energy consumption. The energy consumption of the reboiler can be reduced by 3–7% for different solvents [10].

The study of the process of rich solution split (RSS) began with the research of Eisenberg and Johnson [6,11,12,13]. This improved process divides the rich liquid extracted from the bottom of the absorption tower into two parts. One part is not heated by the lean-rich heat exchanger and is directly pumped into the top of the desorption tower, while the other part is first heated by the lean-rich heat exchanger before entering the lower part of the top of the desorption tower. The energy consumption of the reboiler in the desorption tower can be significantly reduced. The unheated cold rich solvent enters the top of the desorption tower and comes into contact with the high-temperature gas phase. It absorbs the heat of the high-temperature gas phase and releases some CO2, while a portion of the water vapor in the gas phase is cooled and liquefied. The temperature of the gas phase going out of the tower top is decreased, which reduces the heat carried away by the gas phase and thus lowers the energy consumption of the reboiler. By adopting the energy-saving configuration of rich solution split, the energy consumption of the reboiler can be reduced by 8–15% [10].

Another similar method for utilizing the heat of desorption gas is to use the method of exchanging heat between the rich liquid and desorption gas [14]. The principle is the same as the above-mentioned method of separating the rich solvent, but there is no material exchange between the rich solution and desorption gas, resulting in a better heat exchange effect.

Lean solution vaporization and compression (LVC) is also one of the widely used improved processes [5,15,16,17,18]. The high-temperature lean solution extracted from the bottom of the desorption tower or the reboiler first enters a low-pressure flash tank for flash evaporation. The vapor phase obtained from the flasher is then compressed and passed to the lower part of the desorption tower, while the liquid phase after flash still goes to the lean-rich heat exchanger, and then is cooled and enters the absorption tower for the next cycle of CO2 absorption. The vapor phase is obtained through flash evaporation and compression, and its temperature is increased. After entering the bottom of the desorption tower, it provides some heat to the tower, thereby reducing the heat duty of the reboiler. By adopting the energy-saving process of lean solution evaporation and compression, the energy consumption of the reboiler can be reduced by 10–13% [10]. Due to the addition of a compressor in LVC configuration, there is a certain amount of electricity consumption. Also, LVC achieves a 3–5% reduction in overall energy consumption [10]. Furthermore, the high cost of compressors leads to higher equipment investment.

When heating the cold rich solution in the lean-rich heat exchanger, the temperature difference at the hot end can be designed to be below 5 K with enough heat exchange surface, but the temperature difference at the cold end could be as high as 20 K. This indicates that the heat from the hot lean solution is more than that for heating the cold rich solution. There is no need to put all the hot lean solution into LVC. It is more reasonable to take out some of the lean solution sent to the heat exchanger to heat the cold rich solution; meanwhile, the other part of the lean solution is sent to LVC to use the redundant heat in the lean solution.

In this work, a new partial lean solution vaporization and compression configuration (PLVC) is proposed in the absorption method of CO2 capture. With this configuration, only partial lean solution from the desorber is used for LVC to decrease the vaporization gas flowrate, and then smaller compression equipment can be used, and to decrease the electricity consumption, while the other lean solution with high temperature is still pumped to the lean-rich heat exchanger to maintain heat utilization. The important point of PLVC is that some amount of heat in the hot lean solution, which could be used in the lean-rich heat exchanger, is not necessary to be transferred to the heat of the vapor phase in LVC.

2. Methodology

In order to simulate the result of partial lean solution vaporization–compression (PLVC), the widely used aqueous AMP/PZ solution is used as an example in this work. The AMP/PZ/H2O solvent has high CO2 solubility, high absorption rate with PZ added, and relatively low energy consumption [19]. The simulation for CO2 capture was carried out using Aspen Plus V9.0 as described in former works [20,21]. The main settings and assumptions for the simulation are described as follows.

2.1. Simulation Module

The thermodynamic and reaction kinetics model for the AMP-PZ-H2O-CO2 system was first defined. Based on the use of rate models to simulate key equipment such as absorption and desorption towers, a process simulation model for the CO2 capture standard process was established.

2.1.1. Thermodynamic Model

In Aspen Plus, the system contains the following components: H2O, CO2, N2, AMP, PZ, H+, OH−, HCO3−, CO32−, PZH+, PZH22+, HPZCOO, PZCOO−, PZ(COO)22−, AMPH+, and ENRTL-RK is set as the physical property method. This study uses the established thermodynamic model [20] to calculate the thermodynamic properties of the components in the AMP-PZ-H2O-CO2 system.

In terms of chemical equilibrium, the reaction mechanism of the two amines is mainly as follows: AMP reacts with H+ to form AMPH+, and reacts with CO2 to form an unstable amino carbonate. The unstable amino carbonate quickly reacts with other ions in the solution, and the final product is AMPH+; PZ reacts with H+ to generate PZH+, and reacts with CO2 to generate PZCOO− and PZ(COO−)2. Therefore, the following eight reactions are considered in the simulation:

The reaction equilibrium constant can be calculated from the Gibbs free energy difference between reactants and products, and its calculation form is

In Aspen Plus, the Gibbs free energy difference between reactants and products can be calculated from the standard Gibbs free energy and enthalpy of formation of each component in the reaction equilibrium equation at the reference state, as well as the heat capacity in an infinitely diluted aqueous solution. For custom ion components in the system (such as PZH+, PZCOO−, etc.), parameters [20] were also used in this study to calculate related thermodynamic properties.

2.1.2. Kinetic Model

In this study, the Aspen Plus’ rate-based distillation tower model was used to carry out simulations for the absorption tower and the desorption tower. Rate-based model is widely used to calculate multi-stage separation processes, which is more accurate than traditional equilibrium stage models [22]. The use of rate-based models to simulate CO2 absorption processes has been reported in the literature, and the simulation results are in good agreement with experimental data [23,24]. In the rate-based distillation tower model, in addition to the chemical reaction equilibrium, reaction kinetics also need to be considered. In this model, reactions of CO2 with hydroxide ions and amines are considered as kinetic controlled, and the calculation of the reaction rate is as follows:

The reactions and related parameters controlled by kinetics in this model are the same as described in the literature [21].

2.1.3. Absorption Configurations and Simulation Setting

The basic process configuration for CO2 absorption with an absorption tower and a stripper tower is shown in Figure 1. The feed to the absorption tower consists of the aqueous AMP + PZ solvent containing a small amount of CO2, and pretreated flue gas, which contains CO2, N2, O2, and H2O. The composition of flue gas and liquid, as well as various equipment parameters, are set as listed in Table 1, in which CO2 concentration is set to 12% in mole as usual. The solvent concentration of aqueous AMP-PZ solution is set as 30% AMP-10% PZ, and the CO2 loading as mole ratio of CO2 over AMP + PZ in the lean solvent is set to be 0.114. The CO2 capture ratio is set to be 90% with the change in the lean solvent flowrate.

Table 1.

Data settings of main flows for simulation of the system.

The flue gas enters the bottom of the tower, and the solvent flows in from the top of the tower. In the absorption tower, the flue gas comes into contact with the solvent, and the CO2 in the gas reacts with the amine in the solvent and is absorbed. The treated gas is discharged from the top of the tower. The rich solution after absorbing CO2 flows out from the bottom of the absorption tower and enters the heat exchanger HE1 after being pressurized by a pump. The heat exchanger is simulated using the HeatX model in Aspen Plus, with the calculation type selected as shortcut. The temperature difference between the hot and cold logistics outlets is 5 K. The cold rich liquid exchanges heat with the hot lean liquid flowing out from the bottom of the desorption tower in the heat exchanger HE1 and flows into the top of the desorption tower. The rich solution flows down from the top of the desorption tower and comes into contact with the steam generated by the bottom reboiler. Under the temperature and pressure conditions inside the desorption tower, the reaction between CO2 and amine proceeds in reverse, and CO2 is desorbed from the solution and enriched at the top of the desorption tower. To reduce solvent loss, a cooler and a flash evaporation tank is added at the top of both the absorption tower and desorption tower. After flash evaporation, the gas is discharged and the liquid refluxes into the tower. The hot lean solution flowing out from the bottom of the desorption tower is cooled to the temperature of the absorption tower after heat exchange in the heat exchanger HE1, and finally enters the absorption tower to form a complete circulation process.

For simulation of absorber and stripper, the RadFrac module is adopted in Aspen Plus, and the calculation type of rate-based is used. The rate-based model requires a custom packing size, and the packing type for both towers. As listed in Table 2, the type of packing is selected as Sulze mellapack 250Y, with a packing diameter of 2 m for absorber and 1.5 m for stripper, and total packing height is 15 m for absorber and 12 m for stripper with 0.5 m height for every packing section. Br-85, Chilton and Colburn equation, and Br-92 equations are selected separately for mass transfer correlation, heat transfer correlation, and liquid holding model. File reaction is used for film resistance option both for liquid and vapor phases.

Table 2.

Setting of equipment parameters for absorption tower and desorption tower.

For the absorber, the lean solution and liquid from flash F1 are input at top tray 1 of the absorption tower. The cooler temperature for the overhead vapor phase and the lean solution are all set at 313.15 K. The absorber intercooler is set on plate 20, and the liquid temperature is changed to fix the temperature of the rich liquid at the bottom of the absorber as 313.15 K. The capture rate of CO2 in the absorber is optimized to be 90% by varying the flowrate of the lean solution.

For the stripper, three liquid flows at the top are all input at the top tray 1 of the stripper. Pressure is set 1.3 at the top tray and 1.35 at the reboiler. During simulation, reboiler duty is optimized to achieve the 3020 kg/h for CO2 in the top gas flow of the stripper to make sure the flow ‘CO2’ contains 3000 kg/h CO2. The cooler temperature of the overhead vapor phase is also set at 313.15 K and the liquid flow after flash F2 is input to the top tray of stripper.

Heat exchangers HE1 and HE3 are set with the model fidelity as ‘Shortcut’ and ‘Design’ as calculation model, with specifications of ‘Hot inlet-cold outlet temperature difference’ or ‘Hot outlet-cold inlet temperature difference’ of 5 K, while minimum temperature approach is also set as 5 K. After the simulation, the logarithmic mean temperature difference (LMTD) for the two heat exchangers are calculated and listed in the tables of results.

After successfully running the simulation program, Aspen Plus software gives the temperature, pressure, and composition (including customized ions) of each stream, as well as the temperature, pressure, energy consumption, and other results of each unit equipment. All values of heat duty for reboiler, heat exchangers HE1 and HE3, and coolers are also calculated.

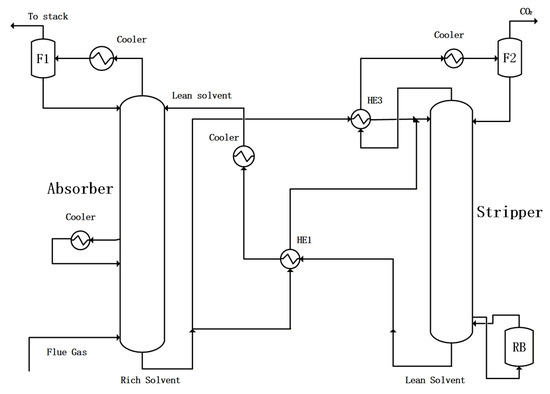

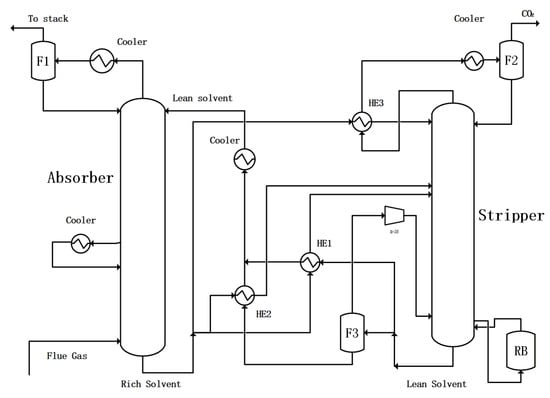

The standard configuration with AIC and RSS for CO2 absorption is shown in Figure 2, in which AIC and RSS are used to reduce energy consumption. The ratio of rich solvent split RRSS is defined as the split flowrate of the rich solvent split stream to the heat exchanger HE3 divided by the total rich solvent from the bottom of the absorber.

Figure 2.

The standard configuration for CO2 absorption with AIC and RSS.

For AIC, the temperature of the rich solvent at the bottom of the absorber is set as 313.15 K with a change in heat duty for the absorber inert cooler. For rich solvent split (RSS), the temperature of the mixed stream to the overhead cooler of the stripper from HE3 is set to be 343.15 K with the change in RRSS value.

The heat consumption (HC) is defined as the heat duty of the reboiler per ton of CO2 captured. The electricity consumption (EC) is defined as the electricity consumption per ton of CO2 captured only for the isentropic compressors of lean or partial lean vapor stream. The total energy consumption (TEC) for per ton of CO2 captured is defined as the sum of heat consumption (HC) plus electricity consumption (EC) which is transferred from kWh to GJ with the calculation equation for Carnot efficiency with the reboiler temperature plus 10 K. The reduction rate of heat consumption (DRHC) is defined as the heat consumption of a configuration compared with that of the standard configuration in Figure 2 with AIC and RSS. The reduction rate of total heat consumption (DRTEC) is defined as the total energy consumption of a configuration compared to that of the standard configuration in Figure 2.

The result for the standard configuration in Figure 2 is listed as the first line in Table 3. The heat consumption HC is 3.24 GJ/t with RRSS 0.186 and LMTDHE1 of 11.2 K. Based on this standard case and the above settings and assumptions, LVC or partial LVC are added and simulation results are compared.

Table 3.

Simulation results for regular and LVC configurations.

2.2. Lean Vapor Compression (LVC) Configuration

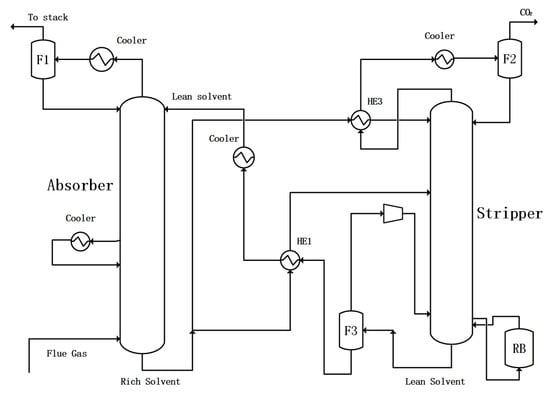

On the basis of the above regular configuration for CO2 capture from a flue gas, the lean vapor compression (LVC) configuration is used as shown in Figure 3. For lean solution flasher F3, pressure is set as 0.7 bar, and heat duty is set as 0.0. For the vapor phase from F3, a compressor is used to increase its discharge pressure to 1.4 bar with isentropic type of isentropic efficiency as 0.8 and mechanic efficiency as 0.9.

Figure 3.

CO2 capture configuration with the lean vapor compression (LVC).

The ratio of lean solvent split RLSS is defined as the split flowrate of the lean solvent split stream to flash 3 over the total lean solvent from the bottom of the stripper.

After simulation for the configuration with LVC, the result is listed in the second line of Table 3. RSS ratio is optimized to be 0.059, and LMTD for HE1 is 7.6 K. Electricity consumption EC is 27.3 kWh/t, and heat consumption is 2.41 GJ/t with about 25.6% decrease compared with that of the basic configuration with only AIC and RSS. Then, total energy consumption is 2.66 GJ/t with an 18% decrease compared with that of the basic configuration.

2.3. New Configurations of Partial Lean Solvent Vaporization and Compression (PLVC)

On the basis of the existing processes, considering the high electricity consumption of lean vapor compression, it is not cost-effective in energy consumption accounting. However, lean vapor input into the stripper can indeed save the steam consumption of the reboiler. This work proposes a new configuration called partial lean solution vaporization and compression (PLVC), with the aim of flexibly using partial lean liquid for flash evaporation to reduce electricity consumption and equipment costs of the flash vapor compressor. When adopting the partial lean solution vaporization and compression configuration, it is best to use it in combination with rich solution split configuration. Taking the AMP + PZ solution also as an example, simulation is carried out using Aspen Plus software.

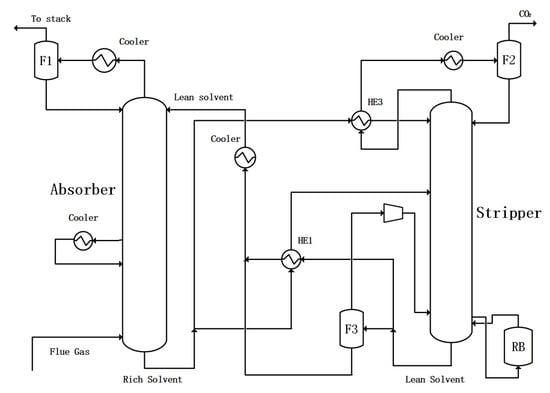

2.3.1. PLVC Without Heat Exchange for Flash Residue Liquid

The first PLVC is shown in Figure 4, in which the lean solution from the bottom of stripper is split, one part of it enters flasher F3, and then the flash vapor is compressed and enters the bottom of the stripper. The remaining solution after flash evaporation directly enters the lean solution cooler. Another part of the lean solution goes to heat exchanger HE1 as usual. The split ratio of lean solution to flasher F3 is defined as RLSS. This configuration is called PLVC without heat exchanger for flash residue liquid.

Figure 4.

CO2 capture configuration with partial lean solution vaporization–compression without more heat exchange.

2.3.2. PLVC with Merged Heat Exchange for Flash Residue Liquid

However, the liquid remaining after the flash evaporation of the partial lean solvent in the above process has not undergone heat exchange with rich liquid, which may result in some heat loss. Therefore, this work proposes to also perform heat exchange between the lean solvent of the flash evaporation residue and the rich solution, which can be performed in two ways:

One way is to combine the flash evaporation residue liquid with other lean liquids together and exchange heat with the rich solution. The flowchart is shown in Figure 5. In this configuration, some of the lean solution from flasher F3 and the remaining liquid from the stripper is pumped to mix with each other and exchange heat with the rich solution. This scheme is called PLVC with merged heat exchange.

Figure 5.

CO2 capture configuration with partial lean solvent vaporization–compression with merged heat exchange.

2.3.3. PLVC with Separate Heat Exchange for Flash Residue Liquid

Another approach is to perform independent heat exchange between the flash evaporation residual liquid and a portion of the rich solution. The flowchart is shown in Figure 6. This flowchart needs a heat exchanger such as HE2 in Figure 6. This approach is called PLVC with separate heat exchange.

Figure 6.

CO2 capture configuration with partial lean solvent vaporization–compression with separate heat exchange.

Also, the ratio of rich solvent split RRSL is defined as the split ratio of the rich solution split stream to HE2. The value of RRSL is minimized accordingly to have the lowest total energy consumption (TEC).

2.3.4. Calculation of Total Energy Consumption for CO2 Capture

For LVC and PLVC flowcharts, electricity is used as the gas compressor. In order to know the total energy consumption, electricity is converted to heat and is added with the heat consumption of reboiler. The normal power generation efficiency is calculated as 42%, the heat exchanger temperature difference is set at 10 K, and the power generation efficiency of steam with a reboiler temperature 383.15 K plus 10 K is 16.8%. Therefore, the PLVC power consumption in kWh needs to be multiplied by 3.6/1000 × 0.42/0.168 = 0.009, to convert the electricity consumption kWh/t to heat GJ/t. Then, it is added with heat consumption to give the total heat consumption (TEC).

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. PLVC Without Heat Exchange for Flash Residue Liquid

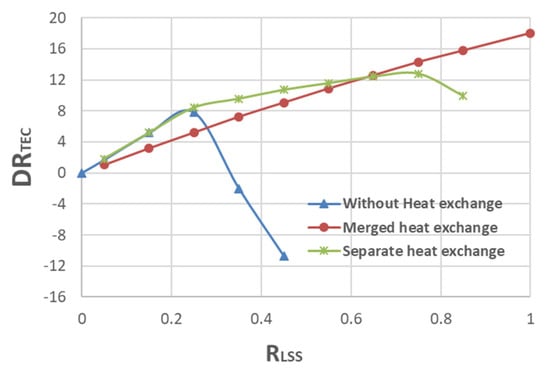

The energy-saving effect of partial lean solution vaporization and compression without heat exchanger as shown in Figure 4 is listed in Table 4 and in Figure 7 (blue line). From Table 4, one can see that when the lean solution split ratio RLSS is increased from 0.0 to 0.25, the heat consumption (HC) and the total energy consumption (TEC) are reduced from 0.0 to 9.7% and 0.0 to 7.8% separately. When the lean solution split ratio RLSS is 0.25 and the rich solution split ratio RRSS is 0.178, the total energy consumption (TEC) is reduced by 7.8%, reaching its maximum value. In this case, only 25% lean solution is needed for flash vaporization and compression, greatly reducing the equipment costs by about 75% of the flasher and compressor.

Table 4.

Energy-saving effect of PLVC without heat exchange for the lean solution split.

Figure 7.

Energy-saving ratio of PLVC with different heat exchange methods.

However, when RLSS is further increased with the optimized RRSS, the heat consumption and total energy consumption start to increase instead, and the energy-saving ratio starts to decrease. When RLSS is 0.35 with the optimized RRSS as 0.08, the heat consumption and total energy consumption are close to those of RLSS at 0.0. This means that there is almost no energy saving compared with the result without lean solvent split. This result indicates that if the residual liquid from flash evaporation does not undergo heat exchange, it has no effect for energy saving.

3.2. PLVC with Merged Heat Exchange for Flash Residue Liquid

The energy-saving effect of PLVC with a merged heat exchange as shown in Figure 5 is listed in Table 5 and in Figure 7 (red line). When RLSS is changed from 0.0 to 1.0 with the optimized RRSS from 0.186 to 0.059, the heat consumption (HC) is reduced from 3.24 to 2.41 GJ/t, and the total energy consumption (TEC) is reduced from 3.24 to 2.66 GJ/t. These data mean that the decrease ratio of heat consumption and total energy consumption are from 0.0 to 25.6% and 0.0 to 18.0% separately.

Table 5.

Energy-saving effect of PLVC with a merged heat exchange.

The increase in the energy-saving effect is almost linearly related to the proportion of lean solution split. This means that spliting the entire lean solution for LVC is most heat efficient. Meanwhile, it is understood that the increase in the split ratio also increases the equipment costs of flashers and compressors with relatively more electricity consumption.

3.3. PLVC with Separate Heat Exchange for Flash Residue Liquid

The energy-saving effect of PLVC with separate heat exchange as shown in Figure 5 is listed in Table 6 and in Figure 7 (green line). When RLSS is changed from 0.0 to 0.75 with the optimized RRSS from 0.186 to 0.105, the heat consumption (HC) is reduced from 3.24 to 2.65 GJ/tCO2, and the total energy consumption (TEC) is reduced from 3.24 to 2.82 GJ/tCO2.

Table 6.

Energy-saving effect of PLVC with separate heat exchange.

Then, when RLSS continues to increase to 0.85, the heat consumption (HC) and total energy consumption (TEC) rise to 2.72 and 2.92 GJ/tCO2, respectively. In this configuration of PLVC with separate heat exchange, 0.75 is the best value for RLSS with the highest energy-saving rate of 12.8%, greatly reducing the equipment costs by about 25% of flasher and compressor costs.

3.4. Comparison of Three Methods of Heat Exchange for PVLC

All results for the three heat exchange methods for PVLC are shown in Figure 7. The three heat exchange methods, after comprehensive lean solution split flash evaporation, include no heat exchange, merged heat exchange, and separate heat exchange for flash residue liquid.

From Figure 7, one can see that during 0.0 to 0.25 of RLSS, the reduction ratio of TEC with no heat exchange and separated heat exchange are the same and better than that with merged heat exchange. Considering the facility cost further, the configuration with no heat exchange is the best choice. During 0.25 to 0.75 of RLSS, the reduction ratio of TEC with separate heat exchange is better that those of TEC with no heat exchange of negative DRTEC and merged heat exchange. Also, further considering the facility cost in this case, the configuration with separate heat exchange is better than that with a merged heat exchanger of a larger volume. Further, during 0.75 to 1.0 of RLSS, the reduction ratio of TEC with merged heat exchange is better than those of TEC with no heat exchange and with separate heat exchange.

For the no heat exchange method, when the lean solution split ratio RLSS is less than 25%, although the energy-saving ratio of the method is slightly lower than that of separate heat exchange, it eliminates one heat exchanger and its corresponding pipelines, reduces equipment investment, and may be suitable from the perspective of comprehensive equipment and operating costs. When the split ratio RLSS is between 25 and 75%, the energy-saving ratio of independent heat exchange is the highest. When RLSS is greater than 75%, the energy-saving ratio of PLVC with a mixed heat exchange is the highest, and it also cut down the separate heat exchanger and its corresponding pipelines to appropriately reduce equipment costs.

In PLVC, not all lean solutions are used for vaporization and compression. The physical meaning is that most enthalpy of the lean solution at high temperatures can be transferred to enthalpy of the rich solution through the lean-rich heat exchanger. The main advantage of PLVC configurations is that the processing capacity of the LVC facility and then the LVC facility cost and electricity consumption could be reduced. However, the detailed setting for the split ratio of the lean solution should be based on the different prices of the steam, electricity, and facilities. It is necessary to have different settings for different industrial cases.

The above calculation results are based on the AMP + PZ system and flue gas with 12% CO2. For all other organic amine systems, PLVC can also be used. The key is to determine the ratio of the lean solvent split RLSS of PLVC based on the costs of steam, electricity, and LVC facilities to find the lowest total cost for CO2 capture. For flue gases with higher CO2 concentration, a larger change in parameters could be expected for best performance.

4. Conclusions

In the research of energy-saving processes and energy integration for organic amine absorption–desorption, considering the high cost of lean liquid flash evaporation compression equipment and the inverted prices of steam and electricity for CO2 capture, a partial lean solution vaporization and compression configuration is proposed, which is equipped with three heat exchange methods: no heat exchange, separate heat exchange, and mixed heat exchange for flash residue liquid. These methods are applicable in the lower (0–25%), middle (25–75%), and higher (75–100%) ranges of the lean solution split ratio for the lowest total heat consumption of the aqueous AMP + PZ solvent. Therefore, the comprehensive cost can be minimized by combining the cost of the flash and compression equipment with electricity and heat prices. The simulation results in this work are based on the AMP + PZ system and flue gas with 12% CO2. For further research, different flue gases with different CO2 concentrations, different solvents, and different prices of steam, electricity, and facilities can be considered for the selection of configurations and parameter optimization with the purpose of lower energy consumption and lower cost for CO2 capture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G. and J.C.; Methodology, D.G., Y.L. (Ye Li) and J.C.; Software, Z.H.; Validation, Y.L. (Yang Li) and J.C.; Formal analysis, H.W., Y.L. (Ye Li) and Y.L. (Yang Li); Investigation, D.G., Z.H., H.W. and Y.L. (Ye Li); Resources, H.W. and Y.L. (Ye Li); Data curation, Z.H. and Y.L. (Yang Li); Writing—original draft, Z.H.; Writing—review and editing, D.G. and J.C.; Visualization, H.W. and Y.L. (Yang Li); Supervision, J.C.; Project administration, Y.L. (Ye Li); Funding acquisition, D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the China Huaneng Group Science and Technology Project (HNKJ22-H14, HNKJ21-H67).

Data Availability Statement

All data have been included in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The China Huaneng Group had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kazemifarh, F. Areview of technologies for carbon capture, sequestration, and utilization: Cost, capacity, and technology readiness. Greenh. Gases Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 200–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardsen, I.M.; Knuutila, H.K. A review of potential amine solvents for CO2 absorption process: Absorption capacity, cyclic capacity and pKa. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2017, 61, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghel, B.; Janati, S.; Wongwises, S.; Shadloo, M.S. Review on CO2 capture by blended amine solutions. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2022, 119, 103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmarghni, S.; Ansarpour, M.; Borhani, T.N. Effect of Different Amine Solutions on Performance of Post-Combustion CO2 Capture. Processes 2025, 13, 2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Moullec, Y.; Neveux, T.; Al Azki, A.; Chikukwa, A.; Hoff, K.A. Process modifications for solvent-based post-combustion CO2 capture. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2014, 31, 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, O.; Alkhatib, I.I.I.; Bahamon, D.; Alhajaj, A.; Abu-Zahra, M.R.M.; Vega, L.F. Modifying absorption process configurations to improve their performance for Post-Combustion CO2 capture—What have we learned and what is still Missing? Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 133096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, A.; Wardhaugh, L.T.; Feron, P.H.M. Analysis of combined process flow sheet modifications for energy efficient CO2 capture from flue gases using chemical absorption. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 1331–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Hillestad, M.; Svendsen, H.F. Investigation of intercooling effect in CO2 capture energy consumption. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 1601–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanpasertparnich, T.; Idem, R.; Tontiwachwuthikumul, P. CO2 absorption in an absorber column with a series intercooler circuits. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 1676–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Yu, Y.; Chen, J. Process simulation and energy consumption for CO2 capture with different flowsheets. Int. J. Glob. Warm. 2017, 12, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Cousins, A.; Yu, H.; Feron, P.; Tade, M.; Luo, W. Systematic study of aqueous monoethanolamine-based CO2 capture process: Model development and process improvement. Energy Sci. Eng. 2016, 4, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moullec, Y.; Kanniche, M. Optimization of MEA based post combustion CO2 capture process: Flowsheeting and energetic integration. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, A.; Wardhaugh, L.T.; Feron, P.H.M. Preliminary analysis of process flow sheet modifications for energy efficient CO2 capture from flue gases using chemical absorption. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2011, 89, 1237–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrin, J.P. Process Sequencing for Amine Regeneration. US Patent 4798910, 17 January 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; St’ephenne, K. Shell Cansolv CO2 capture technology: Achievement from First Commercial Plant. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 1678–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayittey, F.K.; Obek, C.A.; Saptoro, A.; Perumal, K.; Wong, M.K. Process modifications for a hot potassium carbonate-based CO2 capture system: A comparative study. Greenh. Gases Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Yu, Y.; Chen, J. Process Simulation and Energy Consumption Analysis for CO2 Capture with Different Solvents. In Exergy for A Better Environment and Improved Sustainability 1; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 1413–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.T.; Ju, Y.; Chung, K.; Lee, C.-H. Techno-economic analysis of advanced stripper configurations for post-combustion CO2 capture amine processes. Energy 2020, 206, 118164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løge, I.A.; Demir, C.; Vinjarapu, S.H.B.; Neerup, R.; Jensen, E.H.; Jørsboe, J.K.; Dimitriadi, M.; Halilov, H.; Frøstrup, C.F.; Gyorbiro, I.; et al. Pilot-scale CO2 capture in a cement plant with CESAR1: Comparative analysis of specific reboiler duty across advanced process configurations. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 159429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Frailie, P.T.; Rochelle, G.T.; Chen, J. Thermodynamic modeling of piperazine/2-aminomethylpropanol/CO2/water. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2014, 117, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, J.; Luo, X.; Wang, M. Modelling and process analysis of post-combustion carbon capture with the blend of 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol and piperazine. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2017, 63, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüser, N.; Schmitz, O.; Kenig, E.Y. A comparative study of different amine-based solvents for CO2-capture using the rate-based approach. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2017, 157, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Nhien, L.C.; Lee, M. Rate-based modeling and assessment of an amine-based acid gas removal process through a comprehensive solvent selection procedure. Energies 2022, 15, 6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirkhosrow, M.; Pérez-Calvo, J.-F.; Gazzanic, M.; Mazzotti, M.; Lay, E.M. Rigorous rate-based model for CO2 capture via monoethanolamine-based solutions: Effect of kinetic models, mass transfer, and holdup correlations on prediction accuracy. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 1491–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.