Review of CO2 Corrosion Modeling for Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) Infrastructure

Abstract

1. Introduction

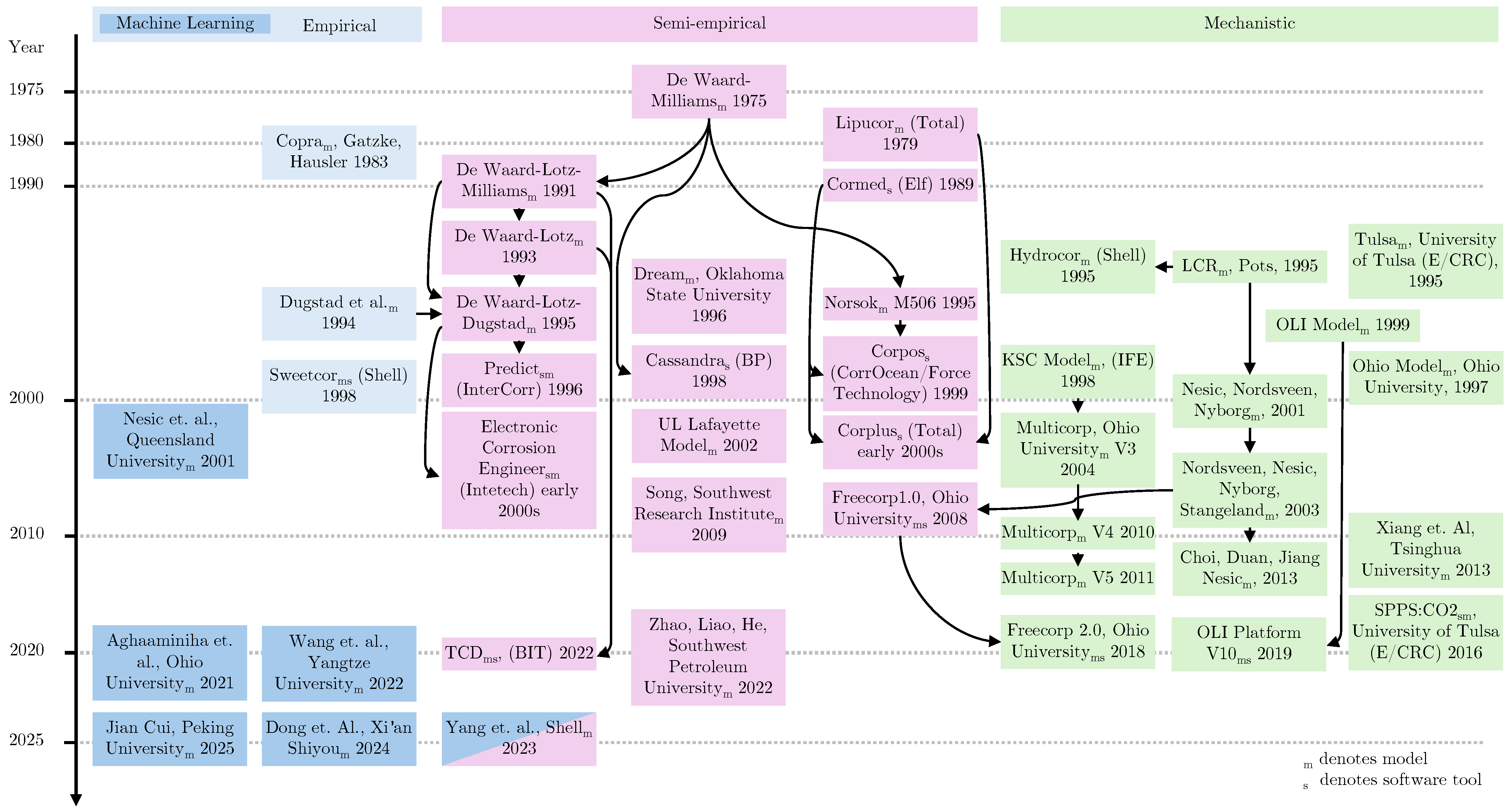

- A historical overview of CO2 corrosion models and software tools, illustrating the major trends, with the recent popularity of machine learning approaches.

- An overview of CO2 corrosion models with their respective strengths, assumptions, and limitations.

- Identification of challenges in CO2 corrosion modeling, with emphasis on data-related problems when applying machine learning approaches to predict CO2 corrosion rate.

- Proposed opportunities given these challenges, through gathering data and increasing the quality of new data by more unified experimental approaches.

2. Properties of CO2 Corrosion

2.1. CO2 Phase Conditions

2.2. Presence of Impurities

2.3. Flow Conditions

2.4. Materials

2.5. Time

3. Modeling Approaches

- Empirical model type is defined by arbitrary mathematical expressions, where parameters are found by fitting the expression to corrosion data.

- Semi-empirical model type is defined by a mathematical expression informed by at least some electrochemical or physical principles, where parameters are found by fitting the expression to corrosion data.

- Mechanistic model type is defined by electrochemical and physics-based equations that generally require more inputs but little to no experimental data.

3.1. Empirical Models

Machine Learning

3.2. Semi-Empirical Models

3.3. Mechanistic Models

3.4. Challenges and Opportunities

- Follow the standard cleaning process of corrosion coupons.

- Verify concentration of impurities.

- State flow conditions, rather than flow versus no flow.

- Consider obtaining samples with different exposure times.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial neural networks |

| CCUS | Carbon capture, utilization, and storage |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| CO | Carbon monoxide |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| Cr | Chromium |

| DT | Decision tree |

| EOR | Enhanced oil recovery |

| Fe | Iron |

| Fe2+ | Ferrous ion (iron in +2 oxidation state) |

| FeCO3 | Iron carbonate |

| FeSO3 | Iron sulfite |

| FeSO4 | Iron sulfate |

| H2 | Hydrogen |

| H2CO3 | Carbonic acid |

| H2O | Water |

| H2S | Hydrogen sulfide |

| KNN | K-nearest neighbors |

| LPR | Linear polarization resistance |

| MEA | Monoethanolamine |

| MDEA | Methyldiethanolamine |

| ML | Machine learning |

| MLP | Multilayer perceptron |

| Mn | Mangan |

| N2 | Nitrogen |

| Ni | Nickel |

| NOx | Nitrogen oxides (e.g., NO, NO2) |

| O2 | Oxygen |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PSO | Particle swarm optimization |

| RF | Random forest |

| Si | Silicon |

| SOx | Sulfur oxides (e.g., SO2, SO3) |

| SVR | Support vector regression |

References

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pörtner, H.O.; Roberts, D.; Skea, J.; Shukla, P.R.; Pirani, A.; Moufouma-Okia, W.; Péan, C.; Pidcock, R.; et al. Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Technical Report; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Ansari, U. From CO2 Sequestration to Hydrogen Storage: Further Utilization of Depleted Gas Reservoirs. Reserv. Sci. 2025, 1, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Hefny, M.; Abdel Maksoud, M.I.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Rooney, D.W. Recent Advances in Carbon Capture Storage and Utilisation Technologies: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, K.; Hay, M.; Ombudstvedt, I.; Skagestad, R.; Joos, M.; Nysæter, G.; Sjøbris, C.; Gimnes Jarøy, A.; Durusut, E.; Craig, J. The Status and Challenges of CO2 Shipping Infrastructures. Ssrn Electron. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, R.T.; Fairweather, M.; Pourkashanian, M.; Woolley, R.M. The range and level of impurities in CO2 streams from different carbon capture sources. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2015, 36, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Ortiz, E.; Yao, C.; Barnes, J.; Winter, M.; Healey, M. Development of a CO2 Specification for Industrial CCS Transport Networks: Methodology, Limitations and Opportunities. In Proceedings of the Annual Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 2–5 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, K.R.; Hansen, D.S.; Pedersen, S. Challenges in CO2 transportation: Trends and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 191, 114149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitali, M.; Corvaro, F.; Marchetti, B.; Terenzi, A. Thermodynamic challenges for CO2 pipelines design: A critical review on the effects of impurities, water content, and low temperature. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2022, 114, 103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loria, P.; Bright, M.B. Lessons captured from 50 years of CCS projects. Electr. J. 2021, 34, 106998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonke, J.; Morland, B.H.; Moulie, G.; Franke, M.S. Corrosion and chemical reactions in impure CO2. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2024, 133, 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morland, B.H.; Tjelta, M.; Dugstad, A.; Svenningsen, G. Corrosion in CO2 systems with impurities creating strong acids. Corrosion 2019, 75, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, K.R.; Hansen, D.S.; Pedersen, S. Experimental Approaches for Emulating CO2 Transportation. In Proceedings of the 17th Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies Conference (GHGT-17), Calgary, AB, Canada, 20–24 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, H.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, J. Corrosion challenges in supercritical CO2 transportation, storage, and utilization—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 179, 113292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Shang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, Q.; Ma, J.; Liu, W. Effect of Temperature on Corrosion Behavior and Mechanism of S135 and G105 Steels in CO2/H2S Coexisting System. Metals 2022, 12, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, K.R.; Goebel, J.; Hansen, D.S.; Pedersen, S. The influence of temperature, H2O, and NO2 on corrosion in CO2 transportation pipelines. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 198, 107190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugstad, A.; Morland, B.; Clausen, S. Corrosion of transport pipelines for CO2—Effect of water ingress. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 3063–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morland, B.H.; Norby, T.; Tjelta, M.; Svenningsen, G. Effect of SO2, O2, NO2, and H2O concentrations on chemical reactions and corrosion of carbon steel in dense phase CO2. Corrosion 2019, 75, 1327–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, R.; Hua, Y.; Neville, A. Internal corrosion of carbon steel pipelines for dense-phase CO2 transport in carbon capture and storage (CCS)—A review. Sage J. 2017, 62, 1176306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Xu, M.; Choi, Y.S. State-of-the-art overview of pipeline steel corrosion in impure dense CO2 for CCS transportation: Mechanisms and models. Sage J. 2017, 62, 1304690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morland, B.H.; Svenningsen, G.; Dugstad, A. The challenge of monitoring impurity content of CO2 streams. Processes 2021, 9, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Lyu, W.; Yu, H.; Lv, W.; Wei, K.; Jiang, L. Advances in Synergistic Corrosion Mechanisms of and Management Strategies for Impurity Gases During Supercritical CO2 Pipeline Transportation. Molecules 2025, 30, 4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonke, J.; Bos, W.; Paterson, S. Materials challenges with CO2 transport and injection for carbon capture and storage. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2022, 114, 103601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Liu, G.; Rao, S.; Fan, X.; Li, Y.; Hu, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z. A critical review on corrosion challenges and prospects in supercritical offshore CO2 pipelines. J. Pipeline Sci. Eng. 2025, 5, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, K.R. CO2 Transportation in CCUS: Impurity Monitoring and Corrosion Challenges; Aalborg University: Aalborg, Denmark, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zero Emissions Platform (ZEP). The Costs of CO2 Transport Post-Demonstration CCS in the EU; Technical Report; Global CCS Institute: Melbourne, Australia, 2011; Available online: https://zeroemissionsplatform.eu/publication/the-costs-of-co2-transport/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Doctor, R.; Palmer, A.; Coleman, D.; Davison, J.; Hendriks, C.; Kaarstad, O.; Ozaki, M.; Austell, M. Transport of CO2. In IPCC Special Report on Carbon dioxide Capture and Storage; Chapter 4; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- de Waard, C.; Milliams, D.E. Carbonic Acid Corrosion of Steel. Corrosion 1975, 31, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesic, S.; Nordsveen, M.; Maxwell, N.; Vrhovac, M. Probabilistic modelling of CO2 corrosion laboratory data using neural networks. Corros. Sci. 2001, 43, 1373–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Wang, C.; Shi, L. CO2 Corrosion Rate Prediction for Submarine Multiphase Flow Pipelines Based on Multi-Layer Perceptron. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Zhang, M.; Li, W.; Wen, F.; Dong, G.; Zou, L.; Zhang, Y. Development of a Predictive Model for Carbon Dioxide Corrosion Rate and Severity Based on Machine Learning Algorithms. Materials 2024, 17, 4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaaminiha, M.; Mehrani, R.; Colahan, M.; Brown, B.; Singer, M.; Nesic, S.; Vargas, S.M.; Sharma, S. Machine learning modeling of time-dependent corrosion rates of carbon steel in presence of corrosion inhibitors. Corros. Sci. 2021, 193, 109904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J. Deep learning-based modeling of CO2 corrosion rate prediction in oil and gas pipelines. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lu, L.; Tsai, K.; Sidahmed, M. A Hybrid Physics and Active Learning Model For CFD-Based Pipeline CO2 and O2 Corrosion Prediction. In Proceedings of the International Petroleum Technology Conference, Bangkok, Thailand, 1–3 March 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyborg, R. CO2 corrosion models for oil and gas production systems. In Proceedings of the Nace Corrosion, NACE, San Antonio, TX, USA, 14–16 March 2010; p. 10371. [Google Scholar]

- Nyborg, R. Guidelines for Prediction of CO2 Corrosion in Oil and Gas Production Systems; Technical Report; Institute for Energy Technology (IFE): Kjeller, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kahyarian, A.; Singer, M.; Nesic, S. Modeling of uniform CO2 corrosion of mild steel in gas transportation systems: A review. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 29, 530–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Yang, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, Z. A comprehensive review of metal corrosion in a supercritical CO2 environment. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2019, 90, 102814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesic, S.; Postlethwaite, J.; Vrhovac, M. CO2 Corrosion of Carbon Steel—From Mechanistic to Empirical Modelling. Corros. Rev. 1997, 15, 211–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosbøl, P.L. Carbon Dioxide Corrosion: Modelling and Experimental Work Applied to Natural Gas Pipelines. Ph.D. Thesis, IVC-SEP Department of Chemical Engineering Technical University of Denmark, Kongens Lyngby, Denmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fontes, E.; Nistad, B. Modeling Corrosion and Corrosion Protection. Comsol White Pap. Ser. 2019, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, D.; Tagliari, M.; Guaglianoni, W.; Tamborim, S.; Borges, M. Carbon Dioxide Corrosion Mechanisms: Historical Development and Key Parameters of CO2-H2O Systems. Int. J. Corros. 2024, 2024, 5537767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachega Cruz, J.P.; Veruz, E.G.; Aoki, I.V.; Schleder, A.M.; de Souza, G.F.M.; Vaz, G.L.; de Barros, L.O.; Orlowski, R.T.C.; Martins, M.R. Uniform corrosion assessment in oil and gas pipelines using corrosion prediction models—Part 1: Models performance and limitations for operational field cases. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 167, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Barker, R.; Neville, A. The effect of O2 content on the corrosion behaviour of X65 and 5Cr in water-containing supercritical CO2 environments. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 356, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X.; Li, X.; Cheng, X.; Liu, H. Synergistic effect of O2, H2S and SO2 impurities on the corrosion behavior of X65 steel in water-saturated supercritical CO2 system. Corros. Sci. 2016, 107, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Ni, W.D. Effect of exposure time on the corrosion rates of X70 steel in supercritical CO2/SO2/O2/H2O environments. Corrosion 2013, 69, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoa, L.Q.; Baessler, R.; Bettge, D. On the Corrosion Mechanism of CO2 Transport Pipeline Steel Caused by Condensate: Synergistic Effects of NO2 and SO2. Materials 2019, 12, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Li, C.; Vera, J.R.; Kovacs, W., III; Evans, K. Effect of CO on Stress Corrosion Cracking of Carbon Steel Pipelines in CCS Environments. In Proceedings of the AMPP Annual Conference + Expo, New Orleans, LO, USA, 3–7 March 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Span, R.; Wagner, W.; Span, R.; Wagner, W. A New Equation of State for Carbon Dioxide Covering the Fluid Region from the Triple-Point Temperature to 1100 K at Pressures up to 800 MPa. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1996, 25, 1509–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, K.R.; Hansen, D.S.; Pedersen, S. Framework for CO2 impurity monitoring in CCUS infrastructure. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2025, 16, 100453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna Ortiz, E. CO2cktails in a pipeline’: The Phase Behaviour of CO2 with >20 impurities. In Proceedings of the 11th Trondheim Conference on Carbon Capture, Transport and Storage, Virtual Conference, 22–23 June 2021; pp. 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Ma, X.; Huang, K.; Fu, L.; Azimi, M. Carbon dioxide transport via pipelines: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 121994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, I.S.; Paterson, D.A.; Corrigan, P.; Sim, S.; Birbilis, N. State of the aqueous phase in liquid and supercritical CO2 as relevant to CCS pipelines. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2012, 7, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Equinor. Northern Lights FEED Report; Technical Report; Equinor: Stavanger, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Peletiri, S.P.; Rahmanian, N.; Mujtaba, I.M. CO2 Pipeline design: A review. Energies 2018, 11, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brescini, M.; Antomarioni, S.; Ciarapica, F.E.; Bevilacqua, M. Techno-economic and environmental assessment of carbon capture solutions in maritime transportation. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 330, 121252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. Thermophysical Properties of Fluid Systems; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025.

- Danish Energy Agency. Carbon Capture, Transport and Storage: Technology Descriptions and Projections for Long-Term Energy System Planning; Danish Energy Agency: København, Denmark, 2024; pp. 1–198. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, F.; Lu, Y. Effects of Impurities on Anthropogenic CO2 Pipeline Transport. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 9958–9966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, D.; Ramdin, M.; Vlugt, T.J. Thermophysical Properties and Phase Behavior of CO2 with Impurities: Insight from Molecular Simulations. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2024, 69, 2735–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyebuchi, V.E.; Kolios, A.; Hanak, D.P.; Biliyok, C.; Manovic, V. A systematic review of key challenges of CO2 transport via pipelines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 2563–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, I.S.; Corrigan, P.; Sim, S.; Birbilis, N. Corrosion of pipelines used for CO2 transport in CCS: Is it a real problem? Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2011, 5, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Sun, J.; Luo, J.L. Unlocking the impurity-induced pipeline corrosion based on phase behavior of impure CO2 streams. Corros. Sci. 2020, 165, 108367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, E.; Liu, W.; Qiao, W. A new hybrid algorithm model for prediction of internal corrosion rate of multiphase pipeline. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 85, 103716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Graver, B.; Gulbrandsen, E.; Dugstad, A.; Morland, B. Update of DNV recommended practice RP-J202 with focus on CO2 corrosion with impurities. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 2432–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morland, B.H.; Tjelta, M.; Norby, T.; Svenningsen, G. Acid reactions in hub systems consisting of separate non-reactive CO2 transport lines. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2019, 87, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Gersen, S. Water Solubility in CO2 Mixtures: Experimental and Modelling Investigation. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 2402–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairy, S.K.; Zhou, S.; Turnbull, A.; Hinds, G. Corrosion of pipeline steel in dense phase CO2 containing impurities: A critical review of test methodologies. Corros. Sci. 2023, 214, 110986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Cui, C.; Dong, S.; Xu, X.; Liu, H. An overview on the corrosion mechanisms and inhibition techniques for amine-based post-combustion carbon capture process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 304, 122091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halseid, M.; Dugstad, A.; Morland, B. Corrosion and bulk phase reactions in CO2 transport pipelines with impurities: Review of recent published studies. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 2557–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.S.; Colahan, M.; Nesic, S. Effect of Flow on the Corrosion Behavior of Pipeline Steel in Supercritical CO2 Environments with Impurities. Corrosion 2023, 79, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.; Li, C.; Hesitao, W.; Long, Z.; Yan, W. Understanding the pitting corrosion mechanism of pipeline steel in an impure supercritical CO2 environment. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 138, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal, J.; Laverde, D.; Fuentes, C. Carbon-steel corrosion in multiphase slug flow and CO2. Corros. Sci. 2006, 48, 2363–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhl, A.S.; Kranzmann, A. Investigation of Pipeline Corrosion in Pressurized CO2 Containing Impurities. Energy Procedia 2013, 37, 3131–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Barker, R.; Neville, A. The influence of SO2 on the tolerable water content to avoid pipeline corrosion during the transportation of supercritical CO2. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2015, 37, 412–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Zou, Q.; Liao, K.; Leng, J.; Zhao, S. Corrosion mechanism of high temperature and O2 content in steamed CO2/O2/SO2 system and failure behavior of 20G steel on steam-injection pipelines. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 163, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, R.; Burkle, D.; Charpentier, T.; Thompson, H.; Neville, A. A review of iron carbonate (FeCO3) formation in the oil and gas industry. Corros. Sci. 2018, 142, 312–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Xu, L.C.; Zeng, Z.X.; Pan, W.G. Mechanism and anti-corrosion measures of carbon dioxide corrosion in CCUS: A review. iScience 2024, 27, 108594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM International. ASTM G1-03; Standard Practice for Preparing, Cleaning, and Evaluating Corrosion Test Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2003. [CrossRef]

- ASTM International. ASTM G31-21; Standard Guide for Laboratory Immersion Corrosion Testing of Metals. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Elgaddafi, R.; Ahmed, R.; Shah, S. Corrosion of carbon steel in CO2 saturated brine at elevated temperatures. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 107638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. Corrosion Monitoring. In Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology; Buschow, K.J., Cahn, R.W., Flemings, M.C., Ilschner, B., Kramer, E.J., Mahajan, S., Veyssière, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 1698–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahyarian, A.; Achour, M.; Nesic, S. Mathematical modeling of uniform CO2 corrosion. Trends Oil Gas Corros. Res. Technol. 2017, 34, 805–849. [Google Scholar]

- Nesic, S. Key issues related to modelling of internal corrosion of oil and gas pipelines—A review. Corros. Sci. 2007, 49, 4308–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyborg, R.; Andersson, P.; Nordsveen, M. Implementation of CO2 Corrosion Models in a Three-Phase Fluid Flow Model 2000. In Proceedings of the CORROSION 2000, Orlando, FL, USA, 26–31 March 2000; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S. CO2 Corrosion Prediction by Use of the NORSOK M-506 Model—Guidelines and Limitations. In Proceedings of the CORROSION 2003, San Diego, CA, USA, 16–21 March2003; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.H. Modelling CO2 Corrosion of Pipeline Steels. Ph.D. Thesis, Newcastle University, Newcastle, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nyborg, R. Overview of CO2 Corrosion Models for Wells and Pipelines 2002. In Proceedings of the CORROSION 2002, Denver, CO, USA, 7–11 April 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Liao, K.; Liu, Y.; Miao, C.; Wei, C.; He, G. Corrosion prediction model of submarine mixed pipeline X65 steel under a CO2/Cl- synergistic system. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2022, 47, 11673–11685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, R.C.; Jordan, K.G.; Young, A.; Kapusta, S.; Thompson, W. SweetCor: An information system for the analysis of corrosion of steels by water and carbon dioxide. In Proceedings of the CORROSION 1998. Association for Materials Protection and Performance, San Diego, CA, USA, 22–27 March 1998; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Nesic, S.; Li, H.; Huang, J.; Sormaz, D. An open source mechanistic model for CO2/H2S corrosion of carbon steel. In NACE–International Corrosion Conference Series; AMPP: Houston, TX, USA, 2009; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pots, B. Mechanistic Models for the Prediction of CO2 Corrosion Rates under Multi-phase Flow Conditions. In Proceedings of the Corrosion 1995, Orlando, FL, USA, 26–31 March 1995; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Gopal, M.; Jepson, W.P. Development of a Mechanistic Model for Predicting Corrosion Rate in Multiphase Oil/Water/Gas Flows. In Proceedings of the CORROSION 1997, New Orleans, LA, USA, 9–14 March 1997; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F. A comprehensive model for predicting CO2 corrosion rate in oil and gas production and transportation systems. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, M.; Li, Z.; Ni, W. A mechanistic model for pipeline steel corrosion in supercritical CO2–SO2–O2–H2O environments. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2013, 82, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.S.; Duan, D.; Jiang, S.; Nesic, S. Mechanistic modeling of carbon steel corrosion in a methyldiethanolamine (MDEA)-based carbon dioxide capture process. Corrosion 2013, 69, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesic, S.; Zheng, Y.; Jing, N.; Esmaeely, S.N.; Ma, Z. Freecorp Tm 2.0 Theoretical Background and Verification; Technical Report; Institute for Corrosion and Multiphase Technology Ohio University: Athens, OH, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- OLI Systems Inc. OLI Studio: Corrosion Analyzer Reference Guide; Technical Report; OLI Systems Inc.: Parsippany, NJ, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- de Waard, C.; Lotz, U.; Milliams, D.E. Predictive Model for CO2 Corrosion Engineering in Wet Natural Gas Pipelines. Corrosion 1991, 47, 976–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbun, B.T.H.; Fadholi, B.Z.; Sinaga, S.Z.; Purbantanu, B.A. Integrated Design and Analysis of Corrosion Rate Model on Tubular Pipe of Oil and Gas Production Well. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1031, 012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.C.; Benson, S.M. (Eds.) Carbon Dioxide Capture for Storage in Deep Geologic Formations—Results from the CO2 Capture Project; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; p. 1358. [Google Scholar]

- Erosion/Corrosion Research Center. Erosion/Corrosion Research Center (E/CRC)—SPPS Modules. Available online: https://www.ecrc-tusmp.org/ecrc (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Nassef, A.; Keller, M.; Hassani, S.; Shirazi, S.; Roberts, K. A Review of Erosion-Corrosion Models for the Oil and Gas Industry Applications. In Recent Developments in Analytical Techniques for Corrosion Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 205–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waard, C.; Lotz, U.; Dugstad, A. Influence of Liquid Flow Velocity on CO2 Corrosion: A Semi-Empirical Model. In Proceedings of the CORROSION 1995, Orlando, FL, USA, 26–31 March 1995; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waard, C.; Lotz, U. Prediction of CO2 Corrosion of Carbon Steel. In Proceedings of the CORROSION 1993, New Orleans, LA, USA, 7–12 March 1993; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugstad, A.; Lunde, L.; Videm, K. Parametric Study of CO2 Corrosion of Carbon Steel. In Proceedings of the CORROSION 1994, Baltimore, MD, USA, 27 February–4 March 1994; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesic, S.; Kahyarian, A.; Choi, Y.S. Implementation of a Comprehensive Mechanistic Prediction Model of Mild Steel Corrosion in Multiphase Oil and Gas Pipelines. Corrosion 2018, 75, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Z.; Zou, X.; Xiong, G.; Yue, X.; Zhang, L. Hybrid Intelligent Model for Predicting Corrosion Rate of Carbon Steel in CO2 Environments. Mater. Corros. 2025, 76, 14840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordsveen, M.; Nesic, S.; Nyborg, R.; Stangeland, A. A Mechanistic Model for Carbon Dioxide Corrosion of Mild Steel in the Presence of Protective Iron Carbonate Films—Part 1: Theory and Verification. Corrosion 2003, 59, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesic, S.; Nordsveen, M.; Nyborg, R.; Stangeland, A. A Mechanistic Model for Carbon Dioxide Corrosion of Mild Steel in the Presence of Protective Iron Carbonate Films—Part 2: A Numerical Experiment. Corrosion 2003, 59, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesic, S.; Lee, K. A Mechanistic Model for Carbon Dioxide Corrosion of Mild Steel in the Presence of Protective Iron Carbonate Films—Part 3: Film Growth Model. Corrosion 2003, 59, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Shen, K.; Tang, S.; Shen, R.; Parker, T.; Wang, Q. Synergistic effect of O2 and SO2 gas impurities on X70 steel corrosion in water-saturated supercritical CO2. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 130, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, L.B.; Zhang, D.; Van Ingelgem, Y.; Steckelmacher, D.; Nowé, A.; Terryn, H. Reviewing machine learning of corrosion prediction in a data-oriented perspective. Npj Mater. Degrad. 2022, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Type | Temp. Range | Pressure Range | Inputs | Limitations | Assumptions | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Waard-Milliams (1975) | Semi-empirical | <90 °C | - | CO2 partial pressure and temperature. | Does not include bicarbonate or hydrogen ions. pH only defined by CO2 equilibrium. Disregard reactions with carbonate. | Relationship between temperature and CO2 partial pressure. Linking potential to corrosion current with pH-dependent expressions. | [28,88,107] |

| LIPUCOR (Total) (1979) | Semi-empirical | 20–150 °C | <250 bar, <50 bar CO2 | H2S in mole%, total pressure, temperature, diameter, water chemistry, and production rate. | - | Based on lab and field data. Calculates pH from CO2 concentration, water chemistry, and temperature. | [20,88,101] |

| CORMED (Elf) (1989) | Semi-empirical | <120 °C | - | - | Does not include oil wetting or liquid flow velocity. | Accepts higher temperatures and ionic strengths but displays a warning, as the pH calculation becomes uncertain. The corrosion risk prediction is still valid. pH calculated from pressure, CO2 concentration, temperature, water chemistry, and free acetic acid. | [20,88,101] |

| De Waard-Lotz-Milliams (1991) | Semi-empirical | - | - | - | No flow velocity. | Correction factors for the effect of corrosion product formation and pH were added. | [99] |

| De Waard-Lotz (1993) | Semi-empirical | - | - | pH, effect of corrosion product film fugacity of CO2, temperature. | No flow velocity. | Builds on top of the de Waard-Milliams equations. The correction factors were adjusted from the 1993 version. Uses correction factors to avoid overestimation of corrosion. | [105] |

| De Waard-Lotz-Dugstad (1995) | Semi-empirical | 0–140 °C | <10 bar CO2 partial pressure | pH, temperature, velocity, CO2 partial pressure. | - | The effects of fluid velocity, mass transport, and composition of the steel were added. This model often gives a lower corrosion rate than the 1991 and 1993 models at low flow rates. | [88,104] |

| NORSOK (1995) | Semi-empirical | 20–150 °C | <1000 bar, <10 bar CO2 | Temperature, total pressure, CO2 concentration, wall shear stress, glycol concentration, and pH. | pH between 3.5–6.5. | Spreadsheet that is open access. Fitted to data from IFE. | [20,88,101] |

| HYDROCOR (Shell) (1995) | Mechanistic | 0–150 °C | <200 bar, <20 bar CO2 | Multi-phase flow. Pressure, temperature, diameter, concentration, H2S, and CO2 in mole%, organic acid, glycol, and bicarbonate concentration, and production rate. | - | The LCR model by Pots is used for the prediction of corrosion. Determines the corrosion rate along the pipeline. Calculation of pH takes the iron and bicarbonate production into account. | [20,88,101] |

| TULSA (1995) | Mechanistic | 38–116 °C | <17 bar CO2 partial pressure | Temperature, liquid flow velocity, pipe diameter, CO2 partial pressure, and pH. | Single-phase flow. Does not take effect from oil wetting. | Electrochemical reaction kinetics and mass transfer. It can be used in straight and elbow pipes. pH can be input directly or calculated from water chemistry. | [20,88,101] |

| PREDICT (InterCorr) (1996) | Semi-empirical | 20–200 °C | <100 bar CO2 partial pressure | Temperature, H2S and CO2 partial pressure, and flow velocity. | pH between 2.5–7. Does not give any limits, either in the software or in the manual. | Based on the de Waard model, with other correction factors. Calculates CO2 partial pressure from the pH. pH can be input directly or calculated from water chemistry or from bicarbonate concentration and ionic strength. | [20,88,101] |

| Dream (1996) | Semi-empirical | - | - | Temperature and pressure at wellhead, separator, and bottomhole, well depth, diameter, water chemistry, gas composition, gas and water production rates. | Does not include hydrocarbon condensates. | Corrosion prediction in annular flow gas wells. Includes effects from protective corrosion films. | [88] |

| Ohio model (1997) | Mechanistic | 10–110 | <20 bar | Temperature, pressure, CO2 concentration, flow rate, pipe diameter, water chemistry. | Protective film formation is not predicted. | pH is either an input or calculated from water chemistry. | [88,93,101] |

| Cassandra (BP) (1998) | Semi-empirical | <140 °C | 200 bar, <10 bar CO2 | Water chemistry, total pressure, temperature, velocity, CO2 in mole% Glycol concentration, oil type, diameter. | - | Implements the de Waard model and BP’s own experience. pH calculated on CO2 content, water chemistry, and temperature. Accepts input outside these values but displays a warning. | [20,88,101] |

| KSC (IFE) (1998) | Mechanistic | 5–150 °C | <250 bar, <50 bar CO2 | Temperature, pressure, partial pressure of CO2, liquid flow velocity, and pH. | Flow velocity between 0.2 and 30 m/s. Does not take oil wetting into account. | Based on electrochemistry. Calculates corrosion rate with and without protective film formation. pH calculated on ionic strength and bicarbonate. | [20,88,101] |

| SweetCor (Shell) (1998) | Empirical | 5–121 °C | 0.2–170 bar CO2 partial pressure | Temperature, pressure, pipe diameter, CO2 mole%, water chemistry, and gas/liquid superficial velocities. | - | Large corrosion dataset from laboratory and field data. Data is grouped using statistics to make correlations and predict the corrosion rate, or by filtering data that closely matches the conditions. pH and corrosion rate are calculated from inputs. | [20,88,90,101] |

| Corpos (CorrOcea) (1999) | Semi-empirical | - | - | Needs calculations of pH, probability of water wetting, and an external fluid flow model. | - | Norsok model is used to calculate corrosion rate at several points along the pipeline. | [88] |

| OLI model (1999) | Mechanistic | - | - | Temperature, pressure, molar composition, flow velocity. | Does not account for oil wetting. | Combines thermodynamic and electrochemical corrosion modeling. Modeling of formation and dissolution of sulfide and carbonate scales. Scale formation has been calibrated from laboratory data. | [88] |

| Electronic Corrosion Engineer (ECE) (early 2000s) | Semi-empirical Software | - | - | O2, H2S, and CO2, and NaCl concentration, water density, liquid density, and length of tubing. | Quantitatively assess corrosion by using thermodynamic simulations to predict free water content for dense phase or supercritical CO2 systems. | Based on de Waard 95 model. Calculates pH from bicarbonate and water chemistry. | [88,100] |

| ULL (2002) | Semi-empirical | - | - | Temperature and pressure at wellhead, separator, and bottomhole, well depth, diameter, water chemistry, gas composition, condensate density, gas, condensate, and water production rates. | - | Developed for gas condensate wells, predicting corrosion rate along the well. Predicts corrosion only when water condenses. | [88] |

| Freecorp 1.0 (2008) | Semi-empirical | 1–120 °C | - | Concentration of H2S, acetic acid, O2, Fe2+, temperature, pressure. | Pipe diameter: 0.01 to 1 m Liquid velocity: 0.001 to 20 m/s Fe2+: 0 to 100 ppm acetic acid: 0 to 1000 ppm pH: 3 to 7, O2: 0 to 10,000 ppm. | Point model: predicts corrosion at a single location with known conditions. Single-phase flow only. Uniform corrosion only. Ideal water chemistry (infinite dilution assumed). No interaction between diffusing species. Salinity effects are ignored. Iron carbonate film growth based on simple supersaturation correlation. The dominant mechanism between CO2 and H2S corrosion is chosen based on the higher predicted corrosion rate. Fe2+ is required for FeCO3 film growth kinetics. Total time must be provided if H2S is present. | [91] |

| Freecorp 2.0 (2018) | Semi-empirical | - | - | H2S, organic acids, flow rate, time. | Ignore effects of high salinity, oxygen, elemental sulfur, etc. | Includes formation and protection by corrosion product layer. Uniform corrosion only. Bulk water chemistry is used, which may differ from surface conditions. No corrosion product layer formation included. Steady-state model, no time-dependent effects. Ideal water chemistry (infinite dilution assumed). Single-phase flow only, uses empirical mass transfer correlations. | [97] |

| OLI Corrosion analyzer (2019) | Mechanistic | - | - | Temperature, pressure, impurity concentration, salt concentration. | Aqueous systems only, not valid for concentrated acids, alcohols, etc. No film shear removal, erosion-corrosion is not modeled. Thin films are not fully included. Transport and gas/liquid equilibrium are simplified. | Thermophysical and electrochemical simulation showing effects of temperature, pressure, pH, concentration, and velocity on corrosion. Inclusion of half-reactions for elements, alloys, and solution species. Electrochemical parameters such as the Tafel slope and the exchange current density are calibrated from the literature. Rigorous transport predictions include diffusion, electrical conductivity, and viscosity. Supports many alloys, including carbon steel, nickel alloys, stainless steel, and aluminum. | [98] |

| Tubular Corrosion Desktop (TCD) (2022) (Bandung Institute of Technology) | Semi-empirical Software created in C++. | - | - | O2, H2S, N2, bicarbonate, CO2, and NaCl concentration, water density, and liquid density. | - | Based on work by de Waard, Liane Smith, and Mike Billingham. | [100] |

| Yang et al. (2023) (Shell) | Machine learning model | - | - | CO2 and O2 partial pressure, pH, and temperature. | - | Uses data generated from CFD simulations. A total of 1122 data points for training and testing of the LightGBM model. The hybrid model is 106 times faster than CFD simulations alone. | [34] |

| Dong et al. (2024) | Machine learning model | 0–200 °C | - | Material, chromium content, H2O, O2, SO2, NO2, and H2S concentration, pressure, temperature, and time. | - | Six different models using SVM, LightGBM, XGBoost, GBDT, KNN, and RF made on 248 data points. | [31] |

| Juian Cui (2025) | Deep learning model | - | - | Temperature, pressure, pH, material, flow rate, water content, carbonic acid concentration, and CO2 concentration. | - | Deep confidence network model optimized with Adam algorithm, made on 75 sets of data. | [33] |

| Empirical | Machine Learning | Semi-Empirical | Mechanistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basis | Data correlation | Data-driven | Physics-informed | Physics-based |

| Interpretability | Low | Low | Medium | High |

| Extrapolation | Poor | Dependent on training | Poor to reasonable | Good |

| Computation time | Low | Low after training | Low | Moderate to high |

| Data need | High | High | Moderate | Little or none |

| Number of Inputs | Few | Moderate | Moderate | Many |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Simonsen, K.R.; Ostadi, M.; Zychowski, M.; Pedersen, S.; Bram, M.V. Review of CO2 Corrosion Modeling for Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) Infrastructure. Processes 2026, 14, 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010170

Simonsen KR, Ostadi M, Zychowski M, Pedersen S, Bram MV. Review of CO2 Corrosion Modeling for Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) Infrastructure. Processes. 2026; 14(1):170. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010170

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimonsen, Kenneth René, Mohammad Ostadi, Maciej Zychowski, Simon Pedersen, and Mads Valentin Bram. 2026. "Review of CO2 Corrosion Modeling for Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) Infrastructure" Processes 14, no. 1: 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010170

APA StyleSimonsen, K. R., Ostadi, M., Zychowski, M., Pedersen, S., & Bram, M. V. (2026). Review of CO2 Corrosion Modeling for Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) Infrastructure. Processes, 14(1), 170. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010170