Abstract

Conventional drilling parameter optimization, heavily reliant on lagging lithology data from periodic mud logging, suffers from significant delays between formation change detection and parameter adjustment. This latency often leads to reduced Rate of Penetration (ROP), accelerated tool wear, and increased risk of drilling complications. To address this, this work introduces a closed-loop machine learning framework for real-time lithology identification and autonomous parameter optimization. Its core is a hybrid deep learning model (1D-CNN-LSTM) that establishes a direct mapping from surface drilling parameters, Weight on Bit (WOB), Rotary Speed (RPM), Torque, ROP, to formation lithology, deliberately excluding dependency on expensive Logging-While-Drilling (LWD) tools to ensure cost-effective and broad applicability. Upon lithology change detection, the system retrieves the historically optimal Mechanical Specific Energy (MSE) value for the identified rock type and solves an inverse MSE model to compute optimal WOB and RPM setpoints within operational constraints. Field validation in a comparative trial demonstrated the framework’s efficacy: the test well achieved a 17.4% increase in ROP, a 37.8% reduction in Non-Productive Time, and an 87.5% decrease in stuck pipe incidents compared to an offset well drilled conventionally.

1. Introduction

The perpetual pursuit of enhanced drilling efficiency remains a cornerstone objective within the hydrocarbon industry, driven by compelling economic and operational imperatives to reduce non-productive time (NPT) and minimize well construction costs [1,2]. The efficacy of rotary drilling operations is fundamentally governed by the complex, non-linear interplay between controllable surface parameters—notably Weight on Bit (WOB) and Rotary Speed (RPM)—and the intrinsic, often heterogeneous, mechanical characteristics of the subsurface formations being penetrated [3,4]. Historically, the selection and adjustment of these critical parameters have predominantly relied upon historical field experience, generalized drilling manuals, and periodic, lagging analysis of mud logging data [5,6]. This inherently reactive paradigm introduces significant latency between the detection of a formation change and the subsequent implementation of an optimal parameter adjustment [7]. Such delays become critically problematic in geologically complex environments, including heterogeneous and interbedded formations, where improper or delayed parameter selection can precipitate a cascade of detrimental outcomes. These include sub-optimal Rate of Penetration (ROP), accelerated wear of the drill bit and downhole tools, severe torsional or axial vibrations, and an elevated risk of costly drilling complications such as stuck pipe or wellbore instability [8,9].

In response to these persistent challenges, the concept of Mechanical Specific Energy (MSE), rigorously defined as the energy input required to excavate a unit volume of rock, has emerged as a pivotal metric for the quantitative, real-time evaluation of drilling efficiency [10,11]. The foundational work of Teale established MSE as a robust means to assess the efficiency of the rock-breaking process, postulating that the theoretical minimum MSE represents the most efficient drilling condition for a given rock type under specific downhole conditions [12,13]. While real-time MSE monitoring has been progressively adopted as a standard practice in many modern drilling operations, its application has largely remained diagnostic and reactive [14]. Engineers typically observe elevated MSE values as a post-facto indicator of inefficient drilling, but the crucial transition to a prescriptive methodology—one that proactively and autonomously determines the optimal parameters required to achieve a target, formation-specific MSE—remains an underdeveloped area [15]. Previous research efforts have predominantly focused on forward modeling of MSE or establishing threshold-based alarm systems; however, a comprehensive, real-time, and formation-aware framework for closed-loop drilling parameter optimization continues to be a subject of ongoing investigation and a significant gap in practical implementation.

For the lithology prediction, prior research applying machine learning for formation characterization often implicitly or explicitly depended on these downhole LWD feeds as model inputs [10,11], creating an accessibility barrier. This sets the stage to clearly position the novelty of the proposed 1D-CNN-LSTM model that deliberately excludes LWD dependency and uses only ubiquitous surface drilling parameters (WOB, RPM, Torque, ROP), a deliberate design choice for universal applicability. In terms of real-time drilling optimization strategies, from Teale’s foundational work [12,13] and its adoption for diagnostic, reactive monitoring [14], to threshold-based alarm systems. Alsubaih et al. emphasized the introduction of mechanical efficiency factors (Ef) to account for energy losses in deviated wells and the practical uncertainties of using surface-derived MSE data, the application of the drill-off test to determine the founder point and optimal WOB for specific bit-formation interactions, linking operational practice with MSE optimization goals, as well as the use of statistical multi-regression analysis (e.g., Bourgoyne and Young model) for ROP prediction, representing a complementary, data-driven optimization approach [16]. Previous optimization strategies can be categorized into: (a) Experience-based manuals and historical trend analysis [5,6], which lack real-time adaptation; (b) Forward-modeling approaches that predict ROP or MSE but do not prescribe parameters; and (c) Simple inversion attempts that lack formation-awareness and integrated constraint management. Such strategies constructed a closed-loop, prescriptive framework that not only monitors MSE but also automatically derives and recommends optimal parameters to achieve a formation-specific target MSE, bridging the diagnostic-prescriptive divide [15]. Concurrently, recent paradigm-shifting advances in machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) present transformative opportunities to overcome these longstanding limitations [17,18,19]. A growing body of research has demonstrated the considerable potential of various data-driven approaches, including supervised classification algorithms and advanced neural networks, for real-time formation characterization from drilling data [20]. Nevertheless, many successful ML models for formation evaluation [20,21] are contingent on specific, high-fidelity downhole data streams (e.g., gamma ray, density). This creates a “generalization gap” [22,23], as noted in the manuscript, where models are not transferable to wells without such tools.

A significant constraint limiting the broad adoption of many proposed intelligent models is their inherent dependence on downhole measurements from Logging-While-Drilling (LWD) tools, such as gamma ray, resistivity, and density logs [20,21]. This reliance faces substantial practical limitations: (1) Non-Universality of Equipment. LWD tools are capital-intensive and are therefore not deployed in all drilling campaigns, particularly in development wells, marginal fields, or operations governed by stringent cost controls. (2) Lack of Data Continuity. LWD data streams can suffer from intervals of missing or poor-quality data due to tool failure, adverse drilling conditions, or telemetry issues. (3) Barrier to Model Generalization. A model whose performance is predicated on specific LWD data would be inapplicable to the vast number of wells drilled without such tools, thereby limiting its industrial scalability [22,23]. This identified gap motivates the core design philosophy of our framework: to leverage exclusively standard, high-frequency surface drilling data to achieve robust real-time formation recognition and optimization, ensuring practical utility across the widest possible range of operations.

This identified gap motivates the development of a novel, comprehensive, and pragmatically designed framework that leverages exclusively standard, high-frequency surface drilling data to achieve robust real-time formation recognition and subsequent, actionable parameter optimization. This paper introduces a closed-loop intelligent methodology designed to bridge this gap through three key, seamlessly integrated contributions: (1) the development and validation of a robust hybrid deep learning model for high-accuracy, real-time lithology identification utilizing only ubiquitous surface drilling parameters, thereby eliminating LWD dependency; (2) a novel knowledge-driven approach for establishing dynamic, formation-specific MSE targets derived from historical performance benchmarks within a contextual depth window; and (3) an efficient inverse solution method for deriving optimal, actionable drilling parameters (WOB, RPM) from the target MSE values, explicitly subject to real-world operational and safety constraints. The integrated system represents a significant advancement toward the realization of intelligent, autonomous drilling systems capable of continuous, formation-adaptive optimization, thereby unlocking new levels of performance, reliability, and economic value in hydrocarbon well construction.

2. Methodology

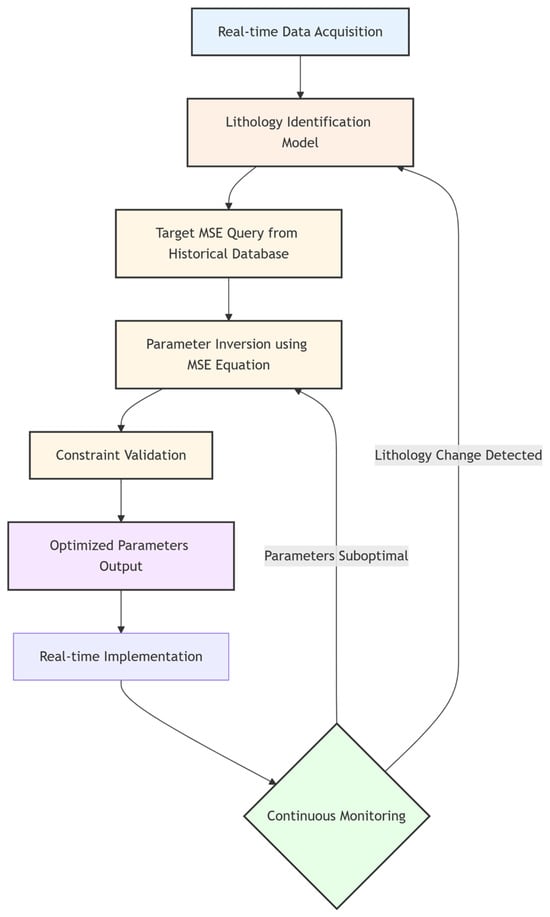

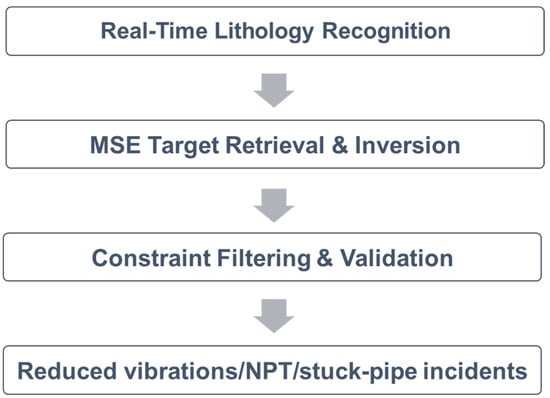

The proposed intelligent optimization framework, conceptually illustrated in Figure 1, establishes a sequential, automated workflow comprising three logically interconnected modules: real-time lithology identification, dynamic target MSE determination, and parameter optimization through MSE inversion. This architecture ensures a seamless flow from geological awareness to operational action.

Figure 1.

Technical framework for autonomous drilling parameter optimization based on real-time lithology identification and MSE inversion via a hybrid machine learning model.

2.1. Real-Time Lithology Identification Module Based on Machine Learning

The foundational and critical first step of this methodology is to establish a high-fidelity, non-linear mapping from real-time surface engineering parameters to discrete formation lithology classes [24]. To achieve this objective, a supervised hybrid deep learning model was meticulously constructed, with real-time streaming drilling parameters serving as inputs and meticulously curated mud logging lithology descriptions acting as the supervised learning target [25,26]. The core design philosophy prioritizes engineering universality and minimal data dependency to ensure broad applicability across diverse drilling environments and asset portfolios.

2.1.1. Input Feature Selection and Data Sources

The input feature vector for the model is deliberately restricted to the fundamental engineering parameters that are routinely, reliably, and necessarily acquired during any conventional rotary drilling operation. These include [27]: Weight on Bit (WOB, kN), Rotary Speed (RPM, min−1), Torque (T, kN·m), Rate of Penetration (ROP, m/h), Bit Diameter (used to calculate the bit cross-sectional area, A_bit, m2), and Measured Depth (MD, m) [28].

While LWD data (e.g., gamma ray, resistivity, density) can undoubtedly provide rich and direct formation information, the incorporation of such data was intentionally avoided due to several pragmatic limitations: (1) Non-Universality of Equipment: LWD tools represent a significant capital expenditure and are therefore not universally deployed, especially in cost-sensitive development wells, marginal field explorations, or projects operating under strict financial controls. (2) Lack of Data Continuity: LWD data can suffer from intervals of missing or poor-quality data due to tool failure, adverse drilling conditions, or telemetry issues. (3) Barriers to Model Generalization: A model whose performance is predicated on the availability of specific LWD data would be fundamentally inapplicable to the vast majority of drilling scenarios lacking that particular data source, thereby severely limiting its value for broad industrial promotion and deployment [29,30].

Consequently, this model deliberately eschews dependence on LWD data, instead utilizing the most core mechanical parameters that are mandatorily recorded in all rotary drilling operations as its features. This strategic choice endows the model with a powerful generalization capability, effectively enabling a “one model, applicable to multiple wells” paradigm, usable wherever rotary drilling is performed.

2.1.2. Target Labels and Training Data Preparation

The training target for the supervised model is the lithological classification derived from rigorous cuttings analysis. On the drilling site, geologists periodically collect rock cuttings returned to the surface via the drilling mud and identify their lithology through microscopic examination and description [31,32]. This data, recorded at discrete depth intervals, serves as the “ground truth” label for model training and validation [33].

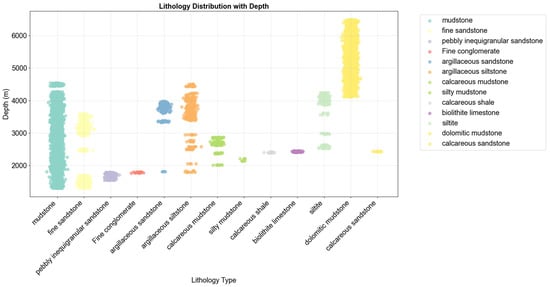

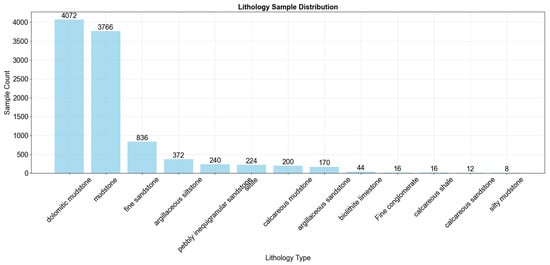

Training and testing datasets were sourced from historical databases containing high-frequency drilling parameters and corresponding depth-aligned mud logging reports from multiple completed wells within the same geological basin [34,35]. Drilling parameters and lithology labels at corresponding depth points were meticulously aligned and synchronized to form a comprehensive training sample set [36]. The data was partitioned chronologically, using older wells for training and more recent wells for testing to ensure a realistic evaluation of predictive performance. Figure 2 shows the lithology distribution with depth from the training dataset, illustrating the vertical stratification and sequence complexity. Figure 3 illustrates lithology sample distribution within the training dataset, showing the relative prevalence of different rock types. The data descriptions are as follows.

Figure 2.

Lithology distribution with depth from the training dataset, illustrating the vertical stratification and sequence complexity.

Figure 3.

Lithology sample distribution within the training dataset, showing the relative prevalence of different rock types (e.g., dolomitic mudstone, mudstone, fine sandstone, etc.).

(1) Dataset Scale. The model was trained and validated on a dataset comprising 15 offset wells from the same geological basin. The total number of processed samples exceeded 120,000. The sample distribution per lithology class (e.g., ~45,000 for mudstone, ~38,000 for fine sandstone) will be detailed in a revised table.

(2) Train/Validation/Test Split. To prevent data leakage and ensure temporal generalization, the split was performed chronologically by well. Specifically, 12 older wells were used for training (with 10% of this set held out for validation during training), and 3 most recently drilled wells were reserved as a completely unseen test set. This simulates a real-world deployment scenario.

(3) Sampling and Sequence. The high-frequency data was resampled to a 1 m interval. The input to the 1D-CNN-LSTM model was a sequential window of 10 m (10 consecutive data points), chosen to capture local drilling dynamics and short-term trends relevant to lithology transitions.

2.1.3. Model Architecture and Training

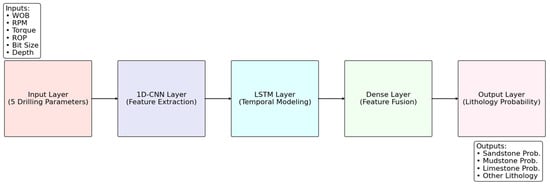

This study employs a sophisticated hybrid neural network architecture combining a one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) with a Long Short-Term Memory network (LSTM) to fully capture both the spatial and temporal dependencies inherent within the sequential drilling parameter data (Figure 4) [37,38].

Figure 4.

Schematic structure of the proposed hybrid 1D-CNN-LSTM model for real-time lithology identification.

The specific architecture, depicted in Figure 4, consists of the following key layers: (1) 1D-CNN Layers: These layers are responsible for extracting local, high-frequency feature patterns from short sequences of engineering parameters. These patterns are often mechanistically associated with specific rock-breaking states and transient responses when drilling through rocks of different hardness and abrasiveness [39,40]. (2) LSTM Layers: This component is responsible for learning long-term trends and contextual relationships of the drilling parameters along the temporal (depth) dimension. This is crucial for identifying the transitional characteristics and subtle “precursors” of parameter changes when crossing lithological boundaries, thereby enhancing prediction robustness and temporal consistency [41,42]. (3) Output Layer: A fully connected layer followed by a Softmax activation function is used to output the probability distribution of the current depth point belonging to each of the pre-defined lithology classes (e.g., shale, sandstone, limestone).

The model was trained using the categorical cross-entropy loss function and the Adam optimizer for efficient stochastic gradient descent. To enhance model robustness and prevent overfitting, stringent data preprocessing (including outlier filtering using statistical methods and precise depth alignment) and data augmentation techniques (such as adding small, random Gaussian noise to simulate realistic measurement errors) were rigorously applied during the training phase. Dropout layers were also incorporated for regularization. The key hyperparameters are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key Hyperparameters of the 1D-CNN-LSTM Model.

2.1.4. Real-Time Identification and Confidence Assessment

In real-time application, the deployed model receives the latest time-series window of drilling parameters via a sliding window mechanism and outputs a probabilistic lithology classification result for the current depth [43]. The system simultaneously calculates a quantitative prediction confidence score based on the output probability distribution. An automated alert is triggered for the drilling engineer under the following two primary circumstances: (1) The predicted lithology class changes compared to the previous depth step, indicating a potential formation boundary. (2) The prediction confidence score falls below a pre-defined threshold (e.g., 80%), indicating anomalous current parameter patterns, potential sensor failure, or high model uncertainty, thereby necessitating manual verification and oversight.

The principal advantage of this model lies in its establishment of an intelligent, data-driven mapping channel from universally available engineering parameters to complex geological attributes. It achieves robust formation awareness without requiring expensive downhole hardware, utilizing only existing, high-frequency surface data streams. This capability lays a solid and practical foundation for the subsequent module of adaptive, formation-specific parameter optimization [44].

2.2. Target MSE Determination

Upon the model identifying a significant lithology change (e.g., from sandstone to shale) with high confidence, the system immediately triggers an alarm and initiates the subsequent parameter optimization process. The first step in this process is to determine an optimal target for drilling energy efficiency—the target MSE—specific to the newly identified lithology [45,46].

Mechanical Specific Energy (MSE), defined as the energy required to crush a unit volume of rock, is calculated using the classical Teale model [47]:

where WOB is the weight on bit (kN), RPM is the rotary speed (min−1), T is the surface torque (kN·m), ROP is the rate of penetration (m/h), and Abit is the cross-sectional area of the drill bit (m2).

The system maintains and continuously updates a historical performance database storing numerous measured MSE values and their associated lithology, depth, and operational context from previously drilled offset wells. For the currently identified lithology at a given depth, the system executes the following query: First, it filters data from the historical database where the measured depth is within a specified contextual window (e.g., ±50 m) of the current depth to account for regional stress and pore pressure trends. From this depth-filtered subset, it then selects all data points where the lithology classification matches the currently identified lithology (e.g., if “sandstone” is identified, it retrieves all historical “sandstone” data within the depth window). From this matching lithology dataset, the most efficient MSE value (i.e., the numerically smallest MSE, indicative of the least energy required per volume) is selected as the target MSE (MSE_optimal) for the current lithology. This value effectively represents the benchmark of optimal rock-breaking energy efficiency historically achieved in that specific lithology type under similar depth conditions and serves as the quantitative target for the subsequent parameter inversion process.

2.3. Parameter Optimization via MSE Inversion

After obtaining the context-aware MSE_optimal target, the objective is to adjust the primary controllable parameters (WOB and RPM) to drive the real-time, calculated MSE (from Equation (1)) towards this target value [48]. The inversion process is formulated by rearranging the MSE equation to solve for one parameter while fixing the other, providing operational flexibility.

For a fixed WOB strategy, the optimal RPM is calculated as:

For a scenario where adjusting RPM is constrained and WOB is the preferred variable, the optimal WOB is given by:

Considering that adjusting WOB often involves greater mechanical inertia and potentially higher risks related to downhole vibrations and stick-slip, the default parameter adjustment strategy prioritizes fixing the current WOB and adjusting RPM as the primary control variable [49]. The WOB adjustment option is typically considered only if adjusting RPM alone cannot converge the MSE to the target value while respecting all operational constraints.

Critically, whether adjusting RPM or WOB, the recommended values are subjected to a comprehensive set of real-world operational constraints to ensure safety and equipment integrity:

(1) WOBmin ≤ WOB ≤ WOBmax (Limits defined by drill string and BHA design)

(2) RPMmin ≤ RPM ≤ RPMmax (Limits defined by top drive or rotary table capacity)

(3) T ≤ Tmax (Torque safety threshold to prevent overloading)

(4) Avoidance of parameter combinations known to induce severe axial or torsional vibrations, stick-slip oscillations, or potential stuck pipe conditions, often defined by empirical rules or secondary models.

Finally, the constrained optimization module outputs a specific, actionable recommended parameter combination (WOBrecommended, RPMrecommended) that satisfies all safety and equipment constraints. This recommendation is presented to the driller or engineer via the human–machine interface in the form of clear, instructive guidance (e.g., “Recommend increasing RPM to X rpm while holding WOB constant”) to assist in data-driven decision-making [50]. The system operates in a continuous advisory loop, periodically re-evaluating lithology and re-calculating optimal parameters as drilling progresses.

3. Results and Discussion

To rigorously verify the effectiveness and practical value of the proposed integrated method, a comprehensive field trial was conducted in a selected oilfield block with known geological complexity. Two offset wells with highly similar geological prognoses and design profiles were chosen for a controlled comparison: Well X was drilled using the traditional, experience-based method for parameter adjustment, serving as the baseline case. Well Y was drilled concurrently, utilizing the proposed intelligent framework for real-time lithology-aware parameter guidance.

3.1. Model Performance Evaluation

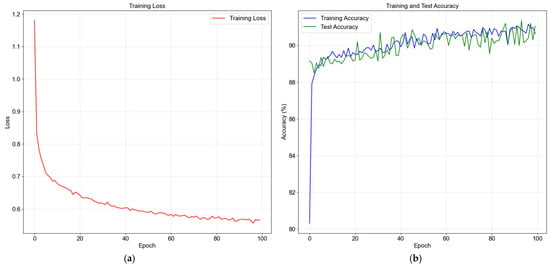

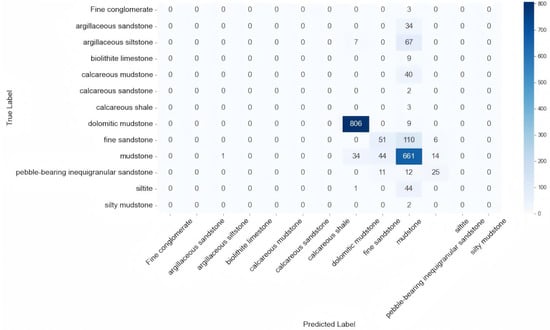

Training results based on historical drilling data show that the proposed hybrid deep learning model exhibits excellent performance in the lithology identification task. Figure 5 shows the lithology identification in terms of model loss and accuracy curves. It is shown that the model loss has been decreasing from 1.2 to 0.55 with the increasing epoch from 0 to 100 (Figure 5a). Additionally, the training accuracy has been increasing from 0.88 to 0.91 while the text accuracy has an increasing trend of 0.884~0.908 (Figure 5b). The model’s generalization capability was further quantified using a hold-out test dataset. The resultant confusion matrix (Figure 6) indicates a good discriminative ability for each lithology class, with particularly high precision and recall for the dominant classes like mudstone and fine sandstone. Minor confusion was observed between lithologically similar classes such as argillaceous siltstone and siltite, which is understandable given their often overlapping mechanical responses.

Figure 5.

Lithology identification model performance. (a) Training and validation loss curves showing steady decrease from ~1.2 to ~0.55 over 100 epochs; (b) Training and validation accuracy curves showing convergence to approximately 91% and 90.8%, respectively.

Figure 6.

Normalized confusion matrix for the lithology identification model on the test dataset, showing prediction accuracy across different lithology classes.

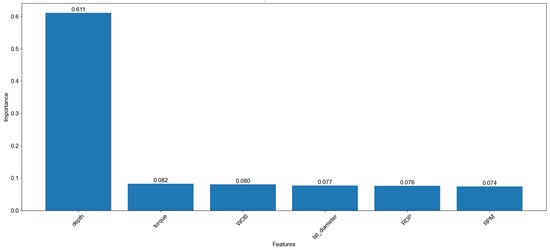

3.2. Feature Importance Analysis

To interpret the model’s decision-making process, a permutation feature importance analysis was conducted. The results, summarized in Figure 7, identified Measured Depth as the single most important feature for lithology prediction, which is fully consistent with the fundamental principles of stratigraphy and the practical experience of field engineers.

Figure 7.

Feature importance ranking derived from permutation analysis, showing Measured Depth (MD) as the most significant predictor, followed by ROP and WOB.

Measured Depth (MD) emerges as the most significant feature for the lithology classification model because it provides a strong prior geological context. Stratigraphy follows a predictable vertical sequence; knowing the depth gives the model a powerful baseline expectation of the formation being drilled, which aligns with standard field practice. This does not hinder operational applicability. In real-time deployment, the model uses the current depth along with real-time drilling parameters (WOB, RPM, etc.) to make its prediction. The depth is used for contextual awareness, not as a control variable. The system’s operational action—parameter optimization—is triggered solely by a change in the predicted lithology (based on the combined input of depth and real-time parameters), not by depth alone.

Despite the primacy of depth, the other engineering parameters (ROP, WOB, Torque, RPM) collectively play crucial corrective and refining roles in lithology identification, allowing the model to detect anomalies, subtle facies changes, and discrepancies from the expected geological column [51].

It is also noted that the feature importance analysis (Figure 7) was conducted solely for interpreting the lithology classification model. It helps understand which inputs the model finds most predictive, confirming it leverages geological principles (stratigraphy via depth) and real-time mechanics. It is not used for optimization decisions. The optimization module is entirely separate and uses only controllable parameters (WOB, RPM) and the target MSE derived from the identified lithology. Depth does not directly influence the parameter calculation in the inversion equations (Equations (2) and (3)).

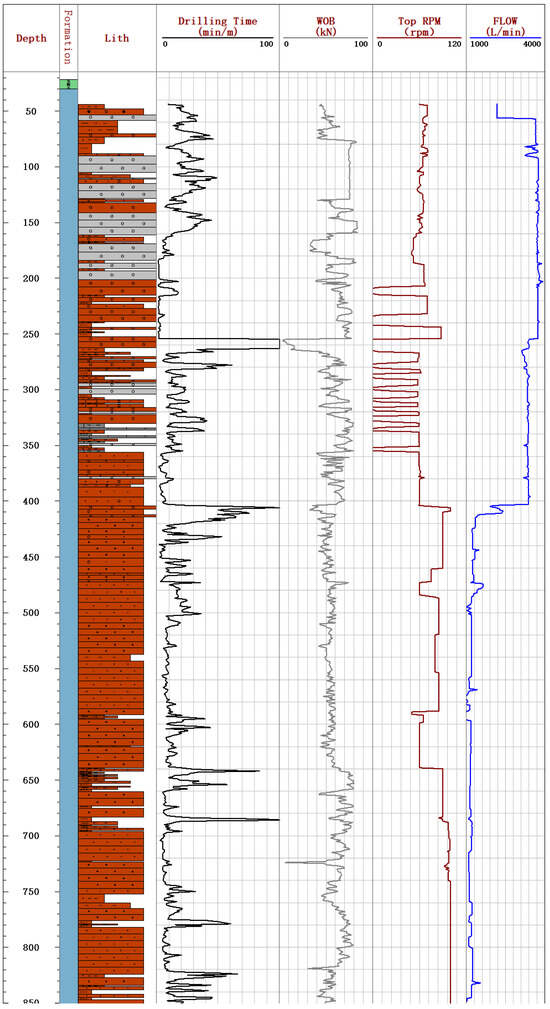

3.3. Lithology Identification Performance

During the drilling of Well Y, the real-time classification system successfully identified 12 major lithology changes, with an average prediction confidence score of 87.2%. Figure 8 provides a depth-based comparison between the model’s real-time output and the subsequently obtained, lab-verified mud logging data, demonstrating close alignment throughout the drilled section. The width of lithology bands correlates with the clay content (e.g., mudstone is the shortest while the sandstone is the longest). The model accurately captured the major transitions from shale to sandstone and vice versa, with a minimal depth lag attributable to the cuttings lag time calculation. This performance confirmed the model’s capability to provide sufficiently accurate and timely formation awareness using only surface data.

Figure 8.

Lithology prediction performance chart for a section of Well Y. The color denotes the lithology color. The width of lithology bands correlates with the clay content (e.g., mudstone is the shortest while the sandstone is the longest). The corresponding WOB and RPM trends are shown in the tracks.

3.4. Drilling Performance Metrics

Implementation of the proposed method yielded significant performance improvements (Table 2). The “stuck-pipe incident” metric was defined based on formal operational records. Events were identified and counted from the wells’ official Non-Productive Time (NPT) records and daily drilling reports, where an incident was logged as “stuck pipe” requiring specific intervention. A confirmed incident required meeting the following operational criteria: a sustained overpull exceeding 50,000 lbs above the expected drag, coupled with a complete loss of string movement, persisting for more than 10 min without resolution through standard driller responses.

Table 2.

Performance comparison between the traditional method (Well X) and the proposed intelligent method (Well Y).

It is noted that Well Y achieved an average ROP of 25.0 m/h, representing a 17.4% increase over Well X (21.3 m/h). Non-productive time was reduced from 45 h to 28 h (37.8% reduction), while stuck pipe incidents decreased dramatically from 0.8 to 0.1 per well.

A representative optimization event occurred at 400 m depth when the system detected a transition from shale to sandstone. The recommended RPM adjustment from 85 to 102 RPM (at constant WOB) resulted in an immediate 22% increase in ROP for that section while maintaining stable torque values.

A representative optimization event occurred at approximately 400 m measured depth when the system detected a transition from a shale to a more drillable sandstone layer. The system recommended an RPM adjustment from 85 to 102 RPM while holding WOB constant. The implementation of this recommendation resulted in an immediate 22% increase in ROP for that section while maintaining stable torque and vibration levels, directly demonstrating the framework’s ability to capitalize on formation changes proactively.

The demonstrated performance improvements translate to substantial economic benefits through reduced rotating hours (directly lowering rig time costs) and a dramatic decrease in troubleshooting operations associated with NPT and stuck pipe events. The framework’s deliberate reliance on standard surface parameters makes it readily and cost-effectively deployable across a wide range of drilling operations without requiring capital-intensive new instrumentation. Furthermore, the system’s advisory nature maintains essential human-in-the-loop oversight while providing robust, data-driven decision support, thereby facilitating smoother technology adoption and workflow integration in traditionally conservative drilling environments.

3.5. Results Analysis

3.5.1. Causal Interpretation of the ROP Improvement

Conventional methods suffer from a significant lag between formation change detection and parameter adjustment [7]. Our real-time lithology identification model (with an average confidence of 87.2%) minimizes this delay. As shown in Figure 8, upon detecting a lithology change (e.g., shale to sandstone at ~400 m), the system immediately triggers optimization. This aligns with findings in [18] on the importance of real-time data for drilling efficiency, but our work automates the execution through a closed-loop system rather than merely providing information.

The ROP gain is directly attributable to the system’s proactive drive towards the historically optimal MSE. Teale’s theory [12,13] posits that the minimum MSE corresponds to the most efficient rock-breaking condition. Our framework operationalizes this theory through real-time inverse solution, translating it into continuous practice. Compared to passive methods that only monitor and alarm based on MSE [14], our framework bridges the gap from “identifying a problem” to “prescribing a solution.” The immediate 22% ROP increase in the 400 m section, for instance, resulted from parameters being automatically optimized to a lower-MSE operating point more suitable for sandstone.

3.5.2. Mechanistic Analysis of the NPT and Stuck Pipe Reduction

The reduction in NPT and stuck pipe incidents is primarily a consequence of the rigorous constraint checking within the optimization module (e.g., torque limits, vibration avoidance rules) (Figure 9). Numerous studies [8,9] identify improper parameter combinations as a root cause of downhole complications. Our system’s “inverse solution + constraint filtering” mechanism fundamentally prevents recommended parameters from entering high-risk zones. This supports conclusions from [48] on the importance of parameter management for downhole dynamic stability, but provides an automated enforcement tool.

Figure 9.

The schematic plot for mechanistic analysis of the NPT and stuck pipe reduction.

Drilling consistently in a high-efficiency (low MSE) state means more energy is used for rock fragmentation rather than detrimental friction and vibration, promoting a more regular and cleaner borehole. Literature [9] indicates that inefficient drilling often leads to cuttings accumulation and wellbore instability. Therefore, pursuing and maintaining the optimal MSE is, in itself, an active borehole quality management strategy, mitigating the root causes of stuck pipe and NPT.

3.5.3. Positioning the Model’s Performance

Our 1D-CNN-LSTM model achieved a 90.3% lithology identification accuracy using only surface data. While some studies [19,20] using LWD data have reported higher accuracy, their applicability is limited. The accuracy achieved here without LWD dependency responds directly to the need for generalizable models highlighted in [22]. It demonstrates the feasibility of reliable geological steering using high-frequency surface data, offering an intelligent solution for the vast number of wells drilled without LWD tools.

In summary, the overall performance leap observed in this trial is the direct result of the closed-loop synergy between real-time geological awareness, data-driven efficiency targeting, and physics-model-based, constrained optimization. It validates that transforming lagging, post-diagnosis (like traditional MSE monitoring) into proactive, formation-specific prescriptive optimization can yield systemic gains in both efficiency and safety. This not only corroborates prior findings on the value of individual technologies (e.g., MSE theory, ML identification, parameter optimization) but, more importantly, addresses the critical “information-to-action” gap through engineered system integration, advancing the concept of autonomous drilling intelligence from theory to field practice.

3.5.4. Assumptions and Validation

For the link between lithology change and rock strength, the manuscript implicitly treats a detected lithology change as a proxy for a significant change in the formation’s mechanical properties, including rock strength (e.g., UCS). This is a foundational assumption, as different lithologies typically exhibit distinct and characteristic strength and drillability ranges. The change point triggers the optimization because the rock-breaking efficiency (MSE) target is lithology-specific.

In terms of the demonstration via MSE, the framework explicitly uses this link. The core action upon detecting a change point is to retrieve the historically optimal MSE for the new lithology. This MSE value inherently represents the most efficient energy state for crushing that specific rock type, which is directly governed by its strength. Therefore, by driving the process toward this new, lithology-specific MSE target (as shown in the 400 m case study, Figure 8), the system is directly responding to the change in rock strength. The observed systematic adjustment of parameters (RPM) to achieve a different MSE level is the operational demonstration that the identified change point coincides with a required shift in the energy input, corresponding to the changed rock strength.

In terms of corrections and implications, no downhole correction factors (e.g., for downhole vs. surface torque, hydraulics, or confining stress) were applied in this work. This is a deliberate pragmatic choice aligning with the framework’s core objective of using only universally available surface data. We acknowledged that this can introduce some absolute error in the calculated MSE value compared to a downhole-corrected ideal. However, the framework’s robustness relies on relative benchmarking, not absolute accuracy. The system uses MSE as a consistent, real-time efficiency index. The “historically optimal MSE” target is derived from the same calculation applied to past data from the same basin. Therefore, any systematic error is consistent across the database and the real-time calculation, making the relative comparison and optimization toward the benchmark valid and effective, as proven by the field results (ROP increase, NPT reduction). This approach prioritizes broad applicability and real-time feasibility over theoretically perfect but data-intensive corrections.

3.6. Future Works

This study’s primary novelty lies in its closed-loop integration of three elements: a real-time, LWD-independent lithology identification model; a knowledge-driven method for setting dynamic, formation-specific MSE targets; and a constrained inverse solution for actionable parameter optimization. This moves beyond purely diagnostic MSE monitoring or offline modeling to create an autonomous, prescriptive system. However, the framework’s effectiveness is subject to two main conditions: (a) The requirement for a geologically similar historical database from the same basin to train the model and define target MSE values. (b) Its performance is contingent on the quality and consistency of real-time surface sensor data. Therefore, to build upon this foundation and transition from a successful prototype to a universally robust technology, several key research extensions are envisioned in the future.

3.6.1. Broader Validation and Generalization

Conducting large-scale field trials across diverse geological basins (e.g., carbonate plays, complex salt structures) and different well types (e.g., high-pressure-high-temperature, deepwater) is crucial. This will test the framework’s adaptability, refine its hyperparameters for various contexts, and build a more comprehensive historical performance database for target MSE determination.

3.6.2. Integration with Advanced Sensor Systems

Fusing the current model’s recommendations with real-time data from downhole vibration, pressure, and imaging tools could create a next-generation advisory system. This would enable multi-objective optimization, balancing ROP with tool health mitigation and precise geopressure management, moving from efficiency optimization towards full-process risk mitigation.

3.6.3. Adaptation to Autonomous Drilling Rig Controls

The logical progression is direct integration with automated drilling control systems. Research should focus on developing secure, low-latency communication protocols and adaptive control algorithms that can execute the framework’s recommendations as setpoints, closing the loop fully without human intervention while ensuring failsafe protocols.

3.6.4. Real-Time Optimization Under Uncertainty

Enhancing the system to quantify and act upon uncertainty is vital. This involves developing Bayesian versions of the lithology model that output probability distributions, and subsequently formulating a robust or stochastic optimization scheme for parameter inversion. This would allow the system to make conservative, risk-aware decisions when confidence is low or sensor data is noisy.

3.6.5. Integration of Additional Physical and Geological Models

Incorporating real-time estimates of unconfined compressive strength (UCS) from drilling data, and contextualizing lithology predictions with seismic or basin models, could provide a richer geological awareness. This would enable physics-informed machine learning, potentially improving accuracy and allowing for predictive optimization ahead of the bit.

In summary, pursuing these directions will transform the framework from a responsive advisor into a predictive, resilient, and universally applicable core component of the autonomous drilling ecosystem.

4. Conclusions

This study has developed and field-validated a novel, closed-loop intelligent framework for real-time lithology identification and autonomous drilling parameter optimization. The work directly addresses the critical industry challenge of delayed response to formation changes inherent in conventional methods, while deliberately eliminating dependency on costly Logging-While-Drilling (LWD) tools to ensure broad and cost-effective applicability.

The core methodological contribution is the seamless integration of three key innovations. First, a hybrid 1D-CNN-LSTM deep learning model was developed to achieve accurate (90.3% test accuracy), real-time lithology classification using exclusively standard, high-frequency surface drilling parameters (WOB, RPM, Torque, ROP). Second, a knowledge-driven system establishes dynamic, formation-specific efficiency targets by retrieving historically optimal Mechanical Specific Energy (MSE) values, contextualized by both lithology and depth. Third, a constrained inverse solution translates these targets into actionable, safe parameter recommendations by solving Teale’s MSE model and rigorously enforcing operational safety limits.

Field validation in a controlled offset well trial confirmed the framework’s transformative efficacy and preventive safety logic. Compared to a well drilled with conventional methods, the intelligently optimized well achieved a 17.4% increase in Rate of Penetration (ROP), a 37.8% reduction in Non-Productive Time (NPT), and a dramatic 87.5% decrease in stuck pipe incidents. These improvements are mechanistically attributable to the system’s closed-loop operation: real-time lithology awareness triggers proactive optimization towards formation-specific efficiency targets, while embedded constraint filtering (as illustrated in the mechanistic flowchart) ensures recommendations avoid parameter combinations known to induce vibrations and other dysfunctions, thereby mitigating risks at their root cause.

The primary practical contribution of this work is a field-deployable, prescriptive optimization system that transforms ubiquitous surface data into actionable intelligence, offering a significant step toward autonomous drilling. A key acknowledged limitation is the framework’s current dependence on a representative historical database from a geologically similar basin for model training and MSE benchmark calibration. Future work will focus on enhancing model generalization across diverse geological settings, integrating real-time downhole dynamics for multi-objective optimization, and advancing direct integration with automated drilling control systems to fully realize the potential of autonomous, adaptive well construction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L. and F.N.; methodology, Q.L. and G.H.; validation, D.L. and H.L.; formal analysis, S.W. and S.L.; investigation, Y.Z. and C.Z.; data curation, K.L. and P.D.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.L.; writing—review and editing, G.H.; funding acquisition, Q.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Core Technology Research Projects of China National Petroleum Corporation (No. 2025ZG84).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their instructive comments that considerably improved the manuscript’s quality.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Qingshan Liu, Dengyue Li, Hefeng Liang, Conghui Zhao and Kun Liu were employed by the CNPC Bohai Drilling Engineering Company No. 1 Mud Logging Company. Author Shuo Liu was employed by the CNPC Bohai Drilling Engineering Company No. 2 Mud Logging Company. Author Yuchen Zhou was employed by the CNPC Changqing Oilfield Digital and Intelligent Division. Author Peng Du was employed by the CNPC Greatwall Drilling Company Mud Logging Company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Song, Y.; Song, Z.; Yang, J.; Wei, L.; Tang, J. Enhancing Energy Efficiency and Sustainability in Offshore Drilling through Real-Time Multi-Objective Optimization: Considering Lag Effects and Formation Variability. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 261, 111138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukredera, F.S.; Youcefi, M.R.; Hadjadj, A.; Ezenkwu, C.P.; Vaziri, V.; Aphale, S.S. Enhancing the Drilling Efficiency through the Application of Machine Learning and Optimization Algorithm. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 126, 107035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oparin, V.N.; Karpov, V.N.; Timonin, V.V.; Konurin, A.I. Evaluation of the Energy Efficiency of Rotary Percussive Drilling Using Dimensionless Energy Index. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 14, 1486–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangxin, F.; Yujie, W.; Guolai, Z.; Yufei, Z.; Shanyong, W.; Ruilang, C.; Enshang, X. Estimation of Optimal Drilling Efficiency and Rock Strength by Using Controllable Drilling Parameters in Rotary Non-Percussive Drilling. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 193, 107376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeinzadeh, H.; Yong, K.-T.; Withana, A. A Critical Analysis of Parameter Choices in Water Quality Assessment. Water Res. 2024, 258, 121777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumarasamy, K.; Belmont, P. Calibration Parameter Selection and Watershed Hydrology Model Evaluation in Time and Frequency Domains. Water 2018, 10, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.; Zhu, D.; Liu, C.; Wang, L. The Multi-AUV Time-Varying Formation Reconfiguration Control Based on Rigid-Graph Theory and Affine Transformation. Ocean Eng. 2023, 270, 113521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, C.; Millwater, H.; Pyrcz, M.; Daigle, H.; Gray, K. Rate of Penetration (ROP) Optimization in Drilling with Vibration Control. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2019, 67, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.-C.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Gao, D.-L. Optimization of Rate of Penetration through Improved Bit Durability and Extended Directional Nozzle. Pet. Sci. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zeng, C.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y.; Su, Q.; Wang, X.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Intelligent Evaluation of Sandstone Rock Structure Based on a Visual Large Model. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2025, 52, 548–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Elkatatny, S.; Al-Majed, A. Coupling Rate of Penetration and Mechanical Specific Energy to Improve the Efficiency of Drilling Gas Wells. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 83, 103558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Yang, S.; Chi, Y.; Lei, Y.; Peng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ling, D.; Wang, L. Bit Optimization Method for Rotary Impact Drilling Based on Specific Energy Model. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 218, 110977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Gao, D.; Guo, B.; Feng, Y. Real-Time Optimization of Drilling Parameters Based on Mechanical Specific Energy for Rotating Drilling with Positive Displacement Motor in the Hard Formation. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 35, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M.; Tan, F.; Zhang, Y.; Sheng, D.; Zuo, C.; Jiao, Y. Development and Application of a Monitoring-While-Drilling System with an Optimized Machine Learning Algorithm for Lithology Identification and Rock Strength Prediction. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025, 58, 10381–10399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, J.; Li, B.; Gan, L.; Zhang, F.; Wang, X.; Wu, Q. Real-Time Drilling Parameter Optimization Model Based on the Constrained Bayesian Method. Energies 2022, 15, 8030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubaih, A.; Albadran, F.; Alkanaani, N. Mechanical Specific Energy and Statistical Techniques to Maximizing the Drilling Rates for Production Section of Mishrif Wells in Southern Iraq Fields. In Proceedings of the SPE/IADC Middle East Drilling Technology Conference and Exhibition, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 29–31 January 2018; SPE: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2018; p. D031S002R003. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, G.; Chen, S.; He, Y.; Wang, H.; Gu, F. Machine Learning-Based Production Forecast for Shale Gas in Unconventional Reservoirs via Integration of Geological and Operational Factors. J. Nat. Gas. Sci. Eng. 2021, 94, 104045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, G.; Ren, Y.; Bi, J.; Wang, M.; Liu, C. Artificial Intelligence Applications and Challenges in Oil and Gas Exploration and Development. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2025, 17, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, G.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Gu, F. An Integrated Machine Learning-Based Approach to Identifying Controlling Factors of Unconventional Shale Productivity. Energy 2023, 266, 126512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Furtado, K.; Zhou, T.; Wu, P.; Chen, X. Constraining Extreme Precipitation Projections Using Past Precipitation Variability. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapucci, M.; Mansueto, P. Cardinality-Constrained Multi-Objective Optimization: Novel Optimality Conditions and Algorithms. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2024, 201, 323–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badshah, A.; Daud, A.; Alharbey, R.; Banjar, A.; Bukhari, A.; Alshemaimri, B. Big Data Applications: Overview, Challenges and Future. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, J.; Cheng, S.; Casas, C.Q.; Liu, C.; Fan, H.; Platt, R.; Rakotoharisoa, A.; Johnson, E.; Li, S.; Shang, Z.; et al. Facing & Mitigating Common Challenges When Working with Real-World Data: The Data Learning Paradigm. J. Comput. Sci. 2025, 85, 102523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Meng, S.; Peng, Y.; Tao, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H. Evaluation of the Adaptability of CO2 Pre-Fracturing to Gulong Shale Oil Reservoirs, Songliao Basin, NE China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2025, 52, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, M.; Elsayed, S.K.; Mahmoud, O. A Supervised Machine Learning Model to Select a Cost-Effective Directional Drilling Tool. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batanero, E.A.; Pascual, Á.F.; Jiménez, Á.B. RLBoost: Boosting Supervised Models Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Neurocomputing 2025, 618, 128815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, P.; Hui, G.; Hu, Y.; Song, R.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, K.; Pi, Z.; Li, Y.; Ge, C.; Yao, F.; et al. Comprehensive Characterization of Hydraulic Fracture Propagations and Prevention of Pre-Existing Fault Failure in Duvernay Shale Reservoirs. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 173, 109461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alali, A.M.; Abughaban, M.F.; Aman, B.M.; Ravela, S. Hybrid Data Driven Drilling and Rate of Penetration Optimization. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 200, 108075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Li, N.; Duan, Y.; Li, H.; Tang, H. Logging-While-Drilling Formation Dip Interpretation Based on Long Short-Term Memory. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2021, 48, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Cao, J.; Yang, T. Remediation of LWD Data Lag with Hybrid Real-Time Data Using Self-Attention-Based Encoder-Decoder Model. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 244, 213461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagbemi, S.; Tahmasebi, P.; Piri, M. Pore-Scale Modeling of Multiphase Flow through Porous Media under Triaxial Stress. Adv. Water Resour. 2018, 122, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Wang, B.; Chen, X.; Tan, P. Reservoir Stimulation for Unconventional Oil and Gas Resources: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Adv. Geo-Energy Res. 2024, 13, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Tang, Y.; Li, G.; Yue, C.; Han, Y.; Wu, X.; Fan, S. Wellbore Stability Prediction Method Based on Intelligent Analysis Model of Drilling Cuttings Logging Images. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 252, 213961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, G.; Chen, S.; Gu, F. Strike–Slip Fault Reactivation Triggered by Hydraulic-Natural Fracture Propagation during Fracturing Stimulations near Clark Lake, Alberta. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 18547–18555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, G.; Chen, Z.; Schultz, R.; Chen, S.; Song, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Song, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, M.; Gu, F. Intricate Unconventional Fracture Networks Provide Fluid Diffusion Pathways to Reactivate Pre-Existing Faults in Unconventional Reservoirs. Energy 2023, 282, 128803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, G.; Chen, Z.-X.; Lei, Z.-D.; Song, Z.-J.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Yu, X.-R.; Gu, F. A Synthetical Geoengineering Approach to Evaluate the Largest Hydraulic Fracturing-Induced Earthquake in the East Shale Basin, Alberta. Pet. Sci. 2023, 20, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xia, J.; Chen, K.; Zhang, D. A Hybrid Model Based on LSTM-CNN Combined with Attention Mechanism for MPC Concrete Strength Prediction. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, T.Q.; Matos, J.C.; Sousa, H.S.; Ngoc, S.D.; Van, T.N.; Nguyen, H.X.; Nguyễn, Q. Data Reconstruction Leverages One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Networks (1DCNN) Combined with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks for Structural Health Monitoring (SHM). Measurement 2025, 253, 117810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, S. Deformable and Residual Convolutional Network for Image Super-Resolution. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiranyaz, S.; Avci, O.; Abdeljaber, O.; Ince, T.; Gabbouj, M.; Inman, D.J. 1D Convolutional Neural Networks and Applications: A Survey. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 151, 107398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, B.; Müller, T.; Vietz, H.; Jazdi, N.; Weyrich, M. A Survey on Long Short-Term Memory Networks for Time Series Prediction. Procedia CIRP 2021, 99, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Selwi, S.M.; Hassan, M.F.; Abdulkadir, S.J.; Muneer, A.; Sumiea, E.H.; Alqushaibi, A.; Ragab, M.G. RNN-LSTM: From Applications to Modeling Techniques and beyond—Systematic Review. J. King Saud Univ.—Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 36, 102068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, C.; Song, X.; Li, Z.; Su, Y.; Li, G.; Zhu, Z. Real-Time Prediction of Logging Parameters during the Drilling Process Using an Attention-Based Seq2Seq Model. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 233, 212279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, H.; Xiong, J.; Luo, Y. Composite Filter-Based Detection of Rock Joints from Drilling Parameters. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 42061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qingfeng, L.; Chi, P.; Jianhong, F.; Xiaomin, Z.; Yu, S.; Chengxu, Z.; Pengcheng, W.; Chenliang, F.; Yaozhou, P. A Comprehensive Machine Learning Model for Lithology Identification While Drilling. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 231, 212333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadeldin, R.; Gamal, H.; Elkatatny, S. Machine Learning Solution for Predicting Vibrations While Drilling the Curve Section. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 35822–35836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazen, A.Z.; Rahmanian, N.; Mujtaba, I.M.; Hassanpour, A. Effective Mechanical Specific Energy: A New Approach for Evaluating PDC Bit Performance and Cutters Wear. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 108030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, T.R.; Nascimento, A.; Mantegazini, D.Z.; Reich, M. Drilling Optimization by Means of Decision Matrices and VB Tool Applied to Torsional Vibration and MSE Surveillance. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hai, W.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Shan, Y.; Wang, C.; Xue, Q. Multi-Element Drilling Parameter Optimization Based on Drillstring Dynamics and ROP Model. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 244, 213460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Long, X.; Meng, G. Mitigation of Stick-Slip Vibrations in Drilling Systems With Tuned Top Boundary Parameters. J. Vib. Acoust. 2021, 143, 051005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; He, R.; Huang, L.; Bai, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, W.; Wang, W. Exploring the Effect of Engineering Parameters on the Penetration of Hydraulic Fractures through Bedding Planes in Different Propagation Regimes. Comput. Geotech. 2022, 146, 104736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.