Abstract

The presence of paracetamol and ciprofloxacin in aquatic ecosystems is a cause for great concern due to their harmful effects on human health. The objectives of this investigation are to simulate an industrial-scale adsorption bed for the competitive removal of these pharmaceutical metabolites from effluents using banana-based activated carbon as the adsorbent. Aspen Adsorption simulation software (v.1) was used to model an industrial-scale packed-bed column under different conditions. Freundlich and Langmuir isothermal models were used in combination with the linear driving force (LDF) kinetic formulation. Adsorption efficiencies of 89.57% for paracetamol and 89.57% for ciprofloxacin were achieved using the Freundlich-LDF model, while the Langmuir-LDF model presented efficiencies of 89.60% for paracetamol and 89.59% for ciprofloxacin. This study used machine learning algorithms, combined with analyses of multiple statistical indicators (R2, RMSE, and MAE), to evaluate model performance. Coefficient of determination (R2) values of up to 0.99 were observed in validation and testing. The application of these mathematical models yielded high removal efficiencies, demonstrating the potential of this approach for drug-contaminated effluent remediation and for forecasting the performance of packed columns at scaled-up levels.

1. Introduction

Pollution is a complex process that alters the physical, chemical, and biological characteristics of water, reducing its quality and availability for various uses and promoting the introduction of pathogens, which significantly increases the risk of waterborne diseases in human populations. Among the primary sources of pollution are industrial waste discharges, which are rich in chemical compounds, and the disposal of untreated urban wastewater, which contributes organic matter, nutrients, and microorganisms to water resources [1].

In recent decades, the presence, distribution, and transport of pharmaceutical compounds in aquatic ecosystems have become the focus of an increasing number of studies. Although the concentrations of these compounds in wastewater are generally lower than those of other organic pollutants, the steady increase in the consumption of human and veterinary medicines has led to their accumulation in the environment [2,3].

Among drugs found in water bodies is acetaminophen (paracetamol), one of the most widely consumed pharmaceuticals worldwide due to its antipyretic and analgesic properties, which has been repeatedly detected in various water systems, raising environmental concerns [4]. The most relevant environmental effects include neurotoxicity and enzyme inhibition. Similarly, effects such as DNA damage, accumulation in body tissues, behavioral disorders in various aquatic organisms, and reduced reproductive capacity have been described [5].

Ciprofloxacin is a synthetic antibacterial agent widely used to treat systemic bacterial infections [6]. Its mechanism of action involves inhibiting bacterial DNA gyrase (topoisomerase II and IV), which is essential for DNA unwinding, supercoiling, and accurate DNA replication [7]. This drug can have adverse health effects if not used correctly, such as nausea, diarrhea, dizziness, abdominal pain, and, in some cases, tendinitis and nervous system problems [8].

Due to the growing presence of pharmaceutical products in wastewater and water resources, techniques for removing contaminants from water bodies have become increasingly important in recent years. Among these, electrocoagulation is an effective alternative whereby dissolved metal hydroxides remove contaminants by dissolving the metal at the anode and generating hydroxyl ions at the cathode [9]. Photocatalysis that chemically degrades substances rather than merely transferring them from one phase to another [10,11]. Similarly, advanced oxidation technologies (AOT) have been widely applied not only in drinking water treatment, but also in industrial effluents and hospital wastewater, with processes such as UV/H2O2, electrochemical oxidation and radiation. These technologies are based on the generation of highly reactive oxygen species, which gives them high potential for removing persistent pharmaceutical contaminants [12,13].

One of the most widely studied techniques is adsorption, owing to its effectiveness and versatility in removing contaminants from water bodies, as well as its simple design, low cost, ease of use, and relative insensitivity to contaminant toxicity. This process is based on the interaction of contaminated aqueous solutions with the porous surfaces of adsorbent materials, which retain the substances to be removed and contribute significantly to water decontamination [14,15].

This removal technique is classified into two types. In physisorption, also known as physical adsorption, molecules in the liquid phase are adsorbed onto the surface of a solid adsorbent via weak physical interactions, primarily van der Waals forces [16]. The other type is chemisorption, also known as chemical adsorption, and one of the main reasons this process occurs is the formation of chemical bonds between the contaminant to be removed and the material used to remove it, resulting in a more potent and more selective interaction, making the process difficult to reverse and requiring more energy to achieve desorption of the adsorbed species [17].

The use of activated carbon derived from agricultural materials has become widespread for wastewater pollutant removal due to its high efficiency, versatility, low installation and operating costs, ability to adsorb a wide range of pollutants, and the availability of numerous adsorbent materials [18]. Banana waste is an excellent adsorbent of contaminants. It is chosen for its wide availability, renewability, and low cost as an abundant agro-industrial waste product, which promotes the principles of the circular economy. Its high carbon content and the presence of inorganic compounds act as pyrogenic agents during pyrolysis, thereby generating well-developed porosity, enhancing contaminant retention, and highlighting its capacity as an activated carbon and adsorbent material [19].

Most research on this type of material has been conducted at the laboratory scale due to constraints on available resources, space, and time, which limit our understanding of pollutant adsorption. Therefore, to understand the behavior of these studies on a larger scale, technologies have been developed that allow such research to be reproduced under broader conditions. Aspen Adsorption software from AspenTech can be used to simulate adsorption processes. This enables the exploration of experiments under different parameter conditions or the variation of operating variables over a broader range, such as flow, bed height, and contaminant concentration, thereby facilitating process optimization before building a pilot or industrial plant.

The implementation of machine learning (ML) techniques allows systems to identify patterns and make decisions based on data without explicit programming. This tool is essential for automating processes, analyzing large volumes of information, and optimizing industrial operations. It also facilitates predictive modeling and process digitization, thereby supporting data-driven decision-making across scientific and technological fields [20,21]. Therefore, this work aims to model a compact adsorption column on an industrial scale through parametric analysis and ML presets to optimize the removal of paracetamol and ciprofloxacin from aqueous solutions, using activated carbon from banana waste as the adsorbent. The current study explores the potential of computational tools, combined with ML presets, to predict the performance of adsorption columns with high accuracy, providing quantitative information on a fixed-bed activated carbon column from agricultural waste.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Configuration and Simulation

A definition of the chemical components (i.e., contaminants to be removed from water sources) is required to develop a model of an adsorption column packed with activated carbon derived from agro-industrial waste for the removal of drug metabolites. The Aspen Adsorption software was employed. In this case, acetaminophen (C8H9NO2) and ciprofloxacin (C17H18FN3O3) are substances widely used in the health sector [22].

Subsequently, the thermodynamic package to be used to compute the physicochemical properties of the water phase of the solution to be treated in this study is defined. They are crucial for adequately characterizing the solution that interacts with the adsorbent, i.e., the water phase in contact with the adsorbent [23]. In this research, the NTRL (Non-Random Two-Liquid) method was defined as a thermodynamic package and a mathematical model widely used to simulate chemical separation processes. This model describes molecular interactions in the liquid phase, enabling more accurate calculation of solute concentration. This makes it a fundamental aspect of modeling adsorption processes, since reliable estimation of liquid-phase concentrations is indispensable for the correct application of adsorption isotherms and, therefore, for the accurate prediction of overall process performance in Aspen Adsorption [24].

Once the initial simulation process configuration is complete, the adsorption column is constructed in the software, incorporating a feed stream, a product stream, and a packed column. Figure 1 shows the resulting flow diagram, which serves as the basis for developing the adsorption model.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the packed adsorption column using Aspen Adsorption.

It is essential to define the parameters and criteria required to accurately configure the packed-adsorption column simulation. The system operating conditions were established as follows: 25 °C, atmospheric pressure (1 atm), an initial concentration of 50 mg/L for both contaminants, and simulation in dynamic mode. Subsequently, the key sections required to define the simulation parameters correctly were configured, as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Criteria established in the configuration of the column.

It is also necessary to establish several parameters for the sizing, operation, and modeling of the packed column in Aspen Adsorption, as these are essential for simulating the equipment used to remove drug metabolites from the selected solutions. To this end, various studies published in the literature were reviewed to identify the parameters required by the Aspen Adsorption software [25,26]. Therefore, a study, analysis, and adjustments of these parameters were carried out for this simulation model. Table 2 presents the parameter values for the packed-column configuration.

Table 2.

Parameters used for the adsorption column simulation.

The mass transfer coefficient was analyzed and adjusted during the packed-bed simulation, thereby numerically stabilizing the model and obtaining the dynamic behavior [27,28]. It should be noted that this parameter was not adjusted to reproduce experimental rupture curves, as no experimental validation was performed.

Similarly, this compact bed configuration requires specific constants for the selected isothermal model. These parameters were adjusted from adsorption studies in batch systems and are associated with the adsorbate-adsorbent interaction and the adsorption energy at the active sites, which depend on the physicochemical properties of the adsorbent and contact with the adsorbate, regardless of the hydrodynamic regime of the system (batch or continuous). The following values were used for this study:

Freundlich Isotherm

- For Acetaminophen ; [29]

- For Ciprofloxacin ; [29]

Langmuir Isotherm

- For Acetaminophen ; [29]

- For Ciprofloxacin ; [29]

It is important to note that these parameters describe only the adsorption equilibrium under static conditions. In dynamic fixed-bed processes, bed performance is not governed exclusively by equilibrium but also depends significantly on kinetic and mass-transfer phenomena, as well as on the hydrodynamic regime. Therefore, in this work, the equilibrium parameters derived from batch studies are used for exploratory purposes, aimed at a qualitative trend analysis and behavior under different operating conditions.

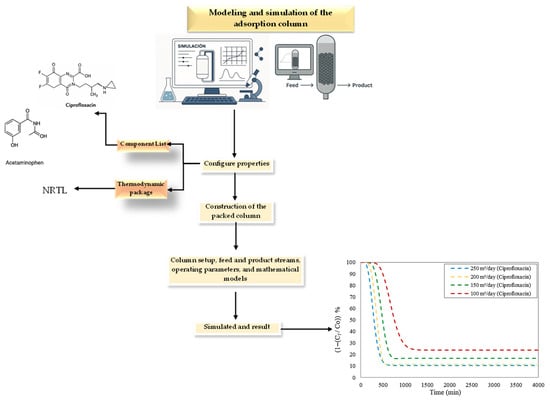

Figure 2 presents the methodology used in this study, which simulates the adsorption column in Aspen Adsorption, considering acetaminophen and ciprofloxacin as pollutants in water bodies.

Figure 2.

Methodology used in this study of Aspen Adsorption software.

2.2. Sensitivity Analysis

To analyze the effects of varying operating conditions on the adsorption process and their overall performance, a sensitivity analysis was performed on a model of the adsorption column for the removal of paracetamol and ciprofloxacin using software. This method enables us to identify how different critical parameters affect the performance of the adsorption column under varying operating conditions and to define the ranges that have the most significant impact on the process [30,31].

For this study, the effects of varying inlet flow rate and bed height on process performance, breakthrough time, and saturation time were analyzed. Table 3 presents the parameter ranges used in the parametric study of drug metabolite adsorption.

Table 3.

Range of values of the parameters during the parametric study.

2.3. Governing Equations

The Aspen Adsorption software integrates a set of necessary mathematical equations into its database, enabling simulations of adsorption processes. It determines the mass balance in the column using a partial differential equation (Equation (1)), which describes the evolution of metal-ion concentration within an infinitesimal control volume in the adsorbent bed [34].

Aspen Adsorption software also offers multiple isothermal models for analyzing interactions between the adsorbate and the adsorbent. The models employed are presented as follows:

- Langmuir isothermal model: it considers that adsorption occurs in a single layer on the surface of the adsorbate, making the adsorption energy constant [35].

- Freundlich model: it describes adsorption as a process that takes place on a homogeneous, multilayer surface, where the distribution of adsorbed components is influenced by both the duration of contact and the energy of the available adsorption sites [36].

These models are described using Equations (2) and (3), respectively.

In the competitive equilibrium framework for adsorption, the Langmuir isotherm assumes a homogeneous surface with a finite removal capacity shared among all contaminants, accounting for the individual concentrations of each species relative to the others in the solution. Meanwhile, the Freundlich isotherm assumes a heterogeneous surface. It constitutes an empirical extension that allows the effects of interaction between solutes to be implicitly incorporated, although without imposing an explicit saturation limit [37,38].

It also employs various kinetic models to describe the adsorption rate, such as the Linear Driving Force (LDF) model, which assumes that mass transfer is driven by a concentration function that governs contaminant adsorption [39], as shown in Equation (6).

2.4. Machine Learning Techniques

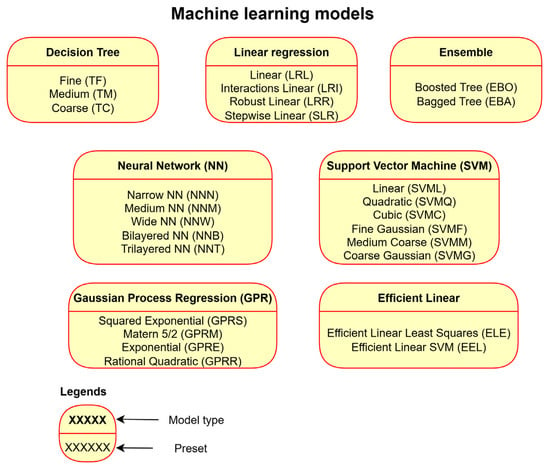

In this research, machine learning techniques were applied to reproduce simulations developed in Aspen Adsorption. Twenty-eight ML algorithms were applied to a dataset of 48 entries on the removal of drug metabolites via adsorption processes, using the Freundlich-LDF and Langmuir-LDF models, which describe the equilibrium and kinetics of the process. The algorithm simulations were performed using the Regression Learner application integrated into MATLAB R2024b, which facilitates the identification of the most appropriate algorithm for modeling the processes under analysis. The 28 ML algorithms used are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Machine learning presets employed in this study.

During the ML training stage, the following predictors were selected: contaminant type, packed bed height, inlet flow rate, and adsorption model type. The selected responses in this study were: breakthrough time (BT), saturation time (ST), and contaminant removal efficiency (1 − ).

To select the ML algorithm best suited to the three responses analyzed, various statistical indicators were used to evaluate model performance. For this purpose, the coefficient of determination (R-squared; R2) was used, selecting the highest value, ideally close to 1. This parameter is calculated using Equation (7):

The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), choosing the lowest value, is calculated by means of Equation (8):

And the mean absolute error (MAE), choosing the lowest value, is calculated using Equation (9):

Three ML presets were used in this study because they achieved the best fit during validation and testing, as measured by R-squared, RMSE, and MAE.

The results for ST and efficiency were better aligned with the Support Vector Machine (SVM) regression algorithm, a nonparametric technique based on kernel functions [40].

BT’s results were better suited to Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), a probabilistic model [41].

2.5. Reference Parameters

To establish reference parameters and contextualize the performance of agro-industrial waste in removing drug metabolites, a comparative analysis was conducted between the results of this research and those previously reported in the literature. The study focused mainly on the breakthrough and saturation times of the columns, which are considered key parameters for evaluating the efficiency of an adsorbent material. This approach enabled comparison of the behavior of the selected adsorbent biomaterial with that of other documented adsorbents, thereby reinforcing the interpretation of the results and highlighting its potential for water treatment applications [42].

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Inlet Flow Rate Effects

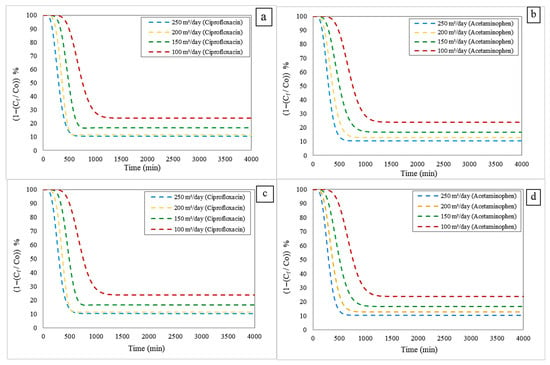

The adsorption column was analyzed by varying the inlet flow rate to 100, 150, 200, and 250 m3/day. During these simulations, the height of the compact bed (3 m) and the initial concentration of both contaminants (50 mg/L) were kept constant to isolate the effect of flow rate on system performance. Figure 4 shows the breakthrough curves for contaminant removal obtained for the isothermal models considered: Freundlich (Figure 4a,b) and Langmuir (Figure 4c,d), both coupled to the LDF kinetic model. These curves indicate the evolution of the adsorption process over time, allowing the fundamental parameters of bed performance to be identified: B.T, S.T, and efficiency.

Figure 4.

Adsorption profiles of contaminants considering inlet flow rates: (a) Freundlich-LDF model for Ciprofloxacin; (b) Freundlich-LDF model for Acetaminophen; (c) Langmuir-LDF model for Ciprofloxacin; and (d) Langmuir-LDF model for Acetaminophen.

According to the results, as the feed flow rate increases, the overall adsorption efficiency also increases due to greater mass transfer driven by the flow velocity. However, this same increase in velocity reduces both the BT and the ST. This phenomenon arises because higher liquid flow facilitates renewal of the boundary layer on the adsorbent surface, thereby promoting mass transfer from the liquid phase to the solid’s active sites. Mechanically, this results in higher flow, which increases the concentration gradient at the liquid-solid interface and increases the amount of contaminant removed before column saturation. However, this behavior has a limit, depending on operating conditions, because an excessively high flow rate shortens the bed’s useful life, thereby reducing process efficiency. This behavior is evident in Table 4.

Table 4.

Data were obtained from variations in the inlet flow rate during the adsorption process.

These values indicate the adsorbent column’s operational performance and service life: higher B.T. values indicate a delay in the advance of acetaminophen and ciprofloxacin, indicating better performance. On the other hand, high S.T. values indicate greater adsorption capacity of the bioadsorbent before regeneration or replacement is required. Therefore, as the flow rate decreases, better B.T. and S.T. values are obtained.

3.2. Bed Height Effects

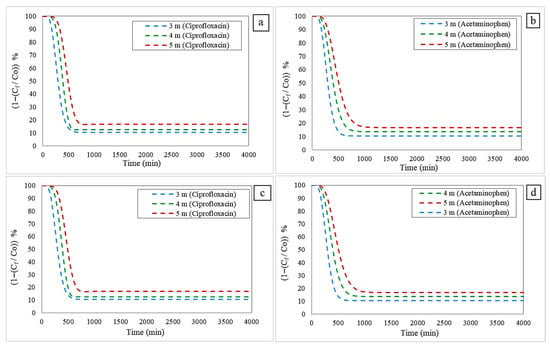

The impact of varying the compact adsorption bed column height was analyzed at 3, 4, and 5 m. In all simulations, the initial contaminant concentration (50 mg/L) and the inlet flow rate (250 m3/day) were held constant to isolate the effect of height on the process. Figure 5 shows the breakthrough curves for contaminant removal obtained with the isothermal models considered: the Freundlich (Figure 5a,b) and Langmuir (Figure 5c,d) models, each coupled to the linear driving force kinetic model. These curves indicate the evolution of the adsorption process over time, allowing the fundamental parameters of bed performance to be identified: B.T, S.T, and efficiency.

Figure 5.

Adsorption profiles of contaminants considering bed heights: (a) Freundlich-LDF model for Ciprofloxacin; (b) Freundlich-LDF model for Acetaminophen; (c) Langmuir-LDF model for Ciprofloxacin; and (d) Langmuir-LDF model for Acetaminophen.

The results show that increasing the bed height increases both the breakthrough time (BT) and the saturation time (ST), but it is accompanied by a decrease in overall process efficiency. This behavior is attributed to the greater volume of adsorbent material available in the system, which increases the number of active sites and delays their occupation, thereby prolonging the total adsorption duration. However, despite this advantage in extended operating time, increasing the height can also introduce practical limitations to overall efficiency, such as greater axial dispersion, additional pressure drops, and increased operating and design costs. These aspects must be carefully evaluated when scaling the process to industrial applications. This behavior is evident in Table 5.

Table 5.

Data obtained from the variation in bed height during the adsorption process.

These values indicate the adsorbent column’s operational performance and service life: higher B.T. values indicate a delay in the advance of acetaminophen and ciprofloxacin, indicating better performance. On the other hand, high S.T. values indicate greater adsorption capacity of the bioadsorbent before regeneration or replacement is required. Therefore, as bed height increases, B.T. and S.T. values also increase.

3.3. ML Implementations

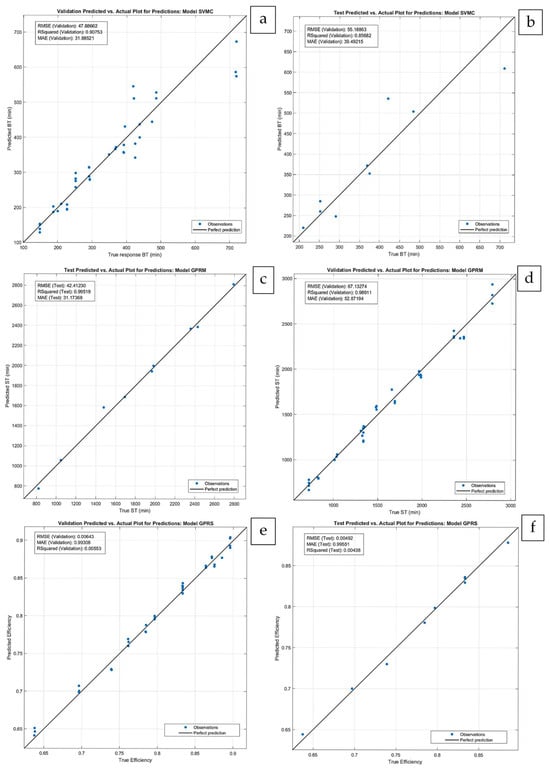

This section presents the results of the simulation of responses obtained by the adsorption model developed in Aspen Adsorption. In total, 28 ML presets (see Figure 3) were used to fit the best presets for each response (, , and (1 − )). The three response variables analyzed (BT, ST, and Efficiency) can be estimated with high accuracy using these techniques, which include both a validation and a testing phase. Table 6 shows the ML algorithms selected for Aspen Adsorption responses. The results obtained for the algorithms are presented in tables included as Supplementary Material.

Table 6.

ML algorithms selected for Aspen Adsorption responses.

The comparison of the values obtained with Aspen Adsorption (True) with the predicted values (Predicted) is shown in Figure 6. The proposed machine learning models achieve an excellent fit with the simulation results, showing good agreement in both the validation and testing phases, indicating that no overfitting occurred. In this study, the 48-point dataset was adequate for model calibration, as the data generated by Aspen software exhibited a pattern that the ML models effectively captured. High R2 values reflect the internal consistency of the simulation dataset.

Figure 6.

Comparison between actual values and predicted values: for BT (a) validation phase and (b) test phase; for ST (c) validation phase and (d) test phase; for efficiency (e) validation phase and (f) test phase.

3.4. Comparative Study

The results from a simulation of a compact bed column, in which activated carbon derived from banana waste was used as an adsorbent on an industrial scale, were compared with values reported in the scientific literature. These comparisons should be interpreted with caution, as the reference studies were conducted under heterogeneous operating conditions, including variations in feed flow rate and column height, as well as the use of different adsorbents. Analysis of the data confirms that the adsorbent material, used as a compact-bed filler at an industrial scale, is highly effective in removing drug metabolites from aqueous media. Table 7 summarizes the values reported in the specialized literature and compares them with the results of this study.

Table 7.

Comparative performance with previous studies.

4. Conclusions

The results of this study are presented as an exploratory study, demonstrating the behavior of an adsorption column packed with activated carbon derived from banana peel and highlighting its potential as a bioadsorbent for the competitive removal of paracetamol and ciprofloxacin in aqueous solutions. Although there is no direct experimental validation, the findings offer valuable information for trend analysis and hypothesis generation regarding system performance.

Significant quantitative values were obtained from simulations of industrial adsorption processes, in which flow rate and bed height affect column performance owing to the balance between mass transfer and the contact time between the solute and the adsorbent. Therefore, a longer adsorption bed delays system saturation, while a higher flow rate favors process performance, indicating that the proper selection of these variables is critical for efficient design and operation.

Similarly, this research demonstrates that ML algorithms can efficiently evaluate model performance, achieving R2 values of up to 0.99 on the validation and test sets. This highlights the viability of reproducing the analyzed process, providing a basis for implementing ML in water treatment operations. In this research, the machine learning models were trained exclusively on simulation-generated data from Aspen.

The integration of Aspen Adsorption, which enables simulation of column behavior under different operating conditions, with machine learning techniques that streamline scenario analysis by adjusting sensitive parameters to improve the model’s predictive capacity, represents a suitable tool for the design and optimization of adsorption systems.

In the future, a technical–economic resilience assessment study will be conducted to determine the viability and supportability of the optimal column configuration. Overall, extending the present approach through targeted experimental validation would enable the transition from an exploratory simulation framework to a more comprehensive, experimentally supported tool for the design and optimization of fixed-bed adsorption systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr14010129/s1, Table S1: Calculation of statistical measures for ML presets (RSquared); Table S2: Calculation of statistical measures for ML presets (RMSE); Table S3: Calculation of statistical measures for ML presets (MAE).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.T.-T. and Á.V.-O.; methodology, C.T.-T., Á.V.-O. and E.H.-R.; software, C.T.-T., O.E.C.-H. and R.D.M.-A.; formal analysis, C.T.-T., Á.V.-O. and E.H.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, C.T.-T., Á.V.-O. and E.H.-R.; writing—review and editing, O.E.C.-H. and R.D.M.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Universidad de Cartagena for providing the equipment, reagents, and technical support for the project approved by Resolution No. 01880 and Act No. 044 of 2022.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Porosity of the column | |

| Longitudinal dispersion coefficient (m2/s) | |

| Length of the bed (m) | |

| Amount of ions absorbed by the adsorbent (mg/g) | |

| Concentration of contaminants in the liquid phase (mg/L) | |

| Apparent density of the adsorbent (kg/m3) | |

| Velocity of the fluid through the bed (m/s) | |

| Adsorption capacity of the contaminant (mg/g) | |

| Maximum loading capacity (mg/g) | |

| Langmuir constant (L/mg) | |

| Concentration of contaminant in solution at equilibrium (mg/L) | |

| Represents competition between solutes for active sites (-) | |

| Freundlich constant indicating adsorption capacity [(mg/g) · (mg/L)n] | |

| Effect of initial concentration on adsorption capacity | |

| Total concentration of solutes present in the solution (mg/L) | |

| Empirical parameter that quantifies the intensity of competition between species (-) | |

| Concentration adsorbed in the solid for component k (mg/g) | |

| Amount that should be adsorbed if the system were in instantaneous equilibrium with the fluid phase (mg/g) | |

| Mass transfer coefficient (1/s) | |

| Indicates the efficiency of the adsorption process (%) | |

| Total number of observations | |

| True value of a response | |

| Predicted value of a response | |

| Average value of observations | |

| Kernel function between two data vectors | |

| Feature vectors of the dataset | |

| Dot product between feature vectors | |

| Degree of the polynomial | |

| Response variable | |

| Latent variable introduced in each observation | |

| Predictors | |

| Matrix of basic functions | |

| Coefficient computed from the dataset | |

| Identify matrix | |

| Error variance |

References

- Pásková, M.; Štekerová, K.; Zanker, M.; Lasisi, T.T.; Zelenka, J. Water pollution generated by tourism: Review of system dynamics models. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Qin, M.; Guo, Z.; Li, X.; Zhou, T.; Zeng, Z.; Zhou, C.; Song, B. Potential of Salvinia biloba Raddi for the remediation of water polluted with ciprofloxacin: Removal, physiological response, and root microbial community. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 480, 136038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, R.; Ding, J.; Li, W.; Wang, B.; Zhang, H. Metformin as an Emerging Pollutant in the Aquatic Environment: Occurrence, Analysis, and Toxicity. Toxics 2024, 12, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez-Restrepo, M.A.; López-Legarda, X.; Segura-Sánchez, F. Bioremediation of emerging pharmaceutical pollutants, acetaminophen and ibuprofen by white-rot fungi—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 977, 179379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.; Yang, X.; Lin, X.; Zhu, L.; Yang, P.; Wang, F.; Shen, Z.; Wang, J.; Ling, Y.; Qiu, Z. Environmental concentrations of acetaminophen and its metabolites promote the spread of antibiotic resistance genes through pheromone signaling pathway. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 488, 150994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwaza, V.; Mlala, S.; Aderibigbe, B.A. Advancements in Synthetic Strategies and Biological Effects of Ciprofloxacin Derivatives: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariati, A.; Arshadi, M.; Khosrojerdi, M.A.; Abedinzadeh, M.; Ganjalishahi, M.; Maleki, A.; Heidary, M.; Khoshnood, S. The resistance mechanisms of bacteria against ciprofloxacin and new approaches for enhancing the efficacy of this antibiotic. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1025633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badawy, S.; Yang, Y.Q.; Liu, Y.; Marawan, M.A.; Ares, I.; Martinez, M.A.; Martínez-Larrañaga, M.R.; Wang, X.; Anadón, A.; Martínez, M. Toxicity induced by ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin: Oxidative stress and metabolism. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2021, 51, 754–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, R.; Sheob, M.; Saeed, B.; Khan, S.U.; Shirinkar, M.; Frontistis, Z.; Basheer, F.; Farooqi, I.H. Use of Electrocoagulation for Treatment of Pharmaceutical Compounds in Water/Wastewater: A Review Exploring Opportunities and Challenges. Water 2021, 13, 2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Ruan, H.; Xue, Y.; Xiao, S. Unlocking photocatalytic NO removal potential in an S-type UiO-66-NH2/ZnS(en)0.5 heterostructure. Interdiscip. Mater. 2024, 3, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Deng, W.Q.; Lu, X. Metallosalen covalent organic frameworks for heterogeneous catalysis. Interdiscip. Mater. 2024, 3, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, M.; Sen, S. Advanced oxidation process: A sustainable technology for treating refractory organic compounds present in industrial wastewater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 25477–25505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, I.M.F.; Cardoso, R.M.F.; Esteves da Silva, J.C.G. Advanced Oxidation Processes Coupled with Nanomaterials for Water Treatment. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewis, D.; Ba-Abbad, M.M.; Benamor, A.; El-Naas, M.H. Adsorption of organic water pollutants by clays and clay minerals composites: A comprehensive review. Appl. Clay Sci. 2022, 229, 106686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, I.U.; Qurashi, A.N.; Adnan, A.; Ali, A.; Malik, S.; Younas, F.; Akhtar, H.T.; Farishta, F.; Janiad, S.; Ali, F.; et al. Bioremediation and Adsorption: Strategies for Managing Pharmaceutical Pollution in Aquatic Environment. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaqarbeh, M. Adsorption Phenomena: Definition, Mechanisms, and Adsorption Types: Short Review. RHAZES Green Appl. Chem. 2021, 13, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukmana, H.; Bellahsen, N.; Pantoja, F.; Hodur, C. Adsorption and coagulation in wastewater treatment—Review. Prog. Agric. Eng. Sci. 2021, 17, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewoyehu, M. Comprehensive review on synthesis and application of activated carbon from agricultural residues for the remediation of venomous pollutants in wastewater. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2021, 159, 105279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karume, I.; Bbumba, S.; Tewolde, S.; Mukasa, I.Z.T.; Ntale, M. Impact of carbonization conditions and adsorbate nature on the performance of activated carbon in water treatment. BMC Chem. 2023, 17, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.; Jameel Ibrahim Alazzawi, F.; Mironov, S.; Reegu, F.; El-Shafay, A.S.; Lutfor Rahman, M.; Su, C.H.; Lu, Y.Z.; Chinh Nguyen, H. Machine learning method for simulation of adsorption separation: Comparisons of model’s performance in predicting equilibrium concentrations. Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 103612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.A.; Jamil, S.; Piran, M.J.; Kwon, O.-J.; Lee, J.-W. A Comprehensive Survey on the Investigation of Machine-Learning-Powered Augmented Reality Applications in Education. Technologies 2024, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubiano, M.L.R.M.; Manacup, C.V.L.; Soriano, A.N.; Rubi, R.V.C. Continuous Biosorption of Pb2+ with Bamboo Shoots (Bambusa spp.) using Aspen Adsorption Process Simulation Software. ASEAN J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 23, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieva, A.D.; Garcia, R.C.; Ped, R.M.R. Simulated Biosorption of Cr6+ Using Peels of Litchi chinensis sonn by Aspen Adsorption® V8.4. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2019, 10, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, R.; Qiblawey, H.; El-Naas, M.H. Evaluation of activated carbon fiber packed-bed for the treatment of gas-to-liquid wastewater: Experimental, modeling and ASPEN Adsorption simulation. Emergent Mater. 2025, 8, 1591–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Upadhyay, U.; Sreedhar, I.; Anitha, K.L. Simulation studies of Cu(II) removal from aqueous solution using olive stone. Clean. Mater. 2022, 5, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Toro, R.; Tejada-Tovar, C.N.; Villabona-Ortiz, Á.; González-Delgado, Á.D.; Vergara-Villadiego, J.C. Computational prediction of packed-bed reactor performance for hexavalent chromium removal from aqueous solution. J. Water Land Dev. 2025, 66, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal Morales, D.M.; Aguirre Domelin, N.A. Escalamiento Columna de Adsorción Para la Remoción de Cromo en Las Aguas Residuales de la Industria de Curtiembre Por Medio de la Cáscara de Banano. Fundación Universidad de América. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11839/8848 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Koua, B.K.; Koffi, P.M.E.; Gbaha, P. Evolution of shrinkage, real density, porosity, heat and mass transfer coefficients during indirect solar drying of cocoa beans. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2019, 18, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Kumar, R.; Pittman, C.U.; Mohan, D. Ciprofloxacin and acetaminophen sorption onto banana peel biochars: Environmental and process parameter influences. Environ. Res. 2021, 201, 111218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Hameed, B.H.; Almomani, F.A.; Usman, M.; Ba-Abbad, M.M.; Khraisheh, M. Dynamic simulation of lead(II) metal adsorption from water on activated carbons in a packed-bed column. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 8283–8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grznár, P.; Gregor, M.; Mozol, Š.; Mozolová, L.; Krump, H.; Mizerák, M.; Trojan, J. A Comprehensive Analysis of Sensitivity in Simulation Models for Enhanced System Understanding and Optimisation. Processes 2024, 12, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadebo, D.; Atukunda, A.; Ibrahim, M.G.; Nasr, M. Integrating chemical coagulation with fixed-bed column adsorption using rice husk-derived biochar for shipboard bilgewater treatment: Scale-up design and cost estimation. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2023, 16, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araujo, C.M.B.; Ghislandi, M.G.; Rios, A.G.; da Costa, G.R.B.; do Nascimento, B.F.; Ferreira, A.F.P.; da Motta Sobrinho, M.A.; Rodrigues, A.E. Wastewater treatment using recyclable agar-graphene oxide biocomposite hydrogel in batch and fixed-bed adsorption column: Bench experiments and modeling for the selective removal of organics. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 639, 128357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Delgado, Á.D.; Tejada-Tovar, C.; Villabona-Ortíz, A. Computer-aided Modeling and Evaluation of a Packed Bed for Chromium (vi) Removal Using Residual Biomass of Theobroma cacao L. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2022, 92, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.K.; Kini, S.; Prabhu, B.; Jeppu, G.P. A simplified modelling procedure for adsorption at varying pH conditions using the modified Langmuir–Freundlich isotherm. Appl. Water Sci. 2023, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, M.R. Physical characteristics and Freundlich model of adsorption and desorption isotherm for fipronil in six types of Egyptian soil. Curr. Chem. Lett. 2023, 12, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Hakimabadi, S.G.; Van Geel, P.J.; Carey, G.R.; Pham, A.L.T. Modified competitive Langmuir model for prediction of multispecies PFAS competitive adsorption equilibria on colloidal activated carbon. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 345, 127368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorshidi, N.; Azadmehr, A.R. Competitive adsorption of Cd (II) and Pb (II) ions from aqueous solution onto Iranian hematite (Sangan mine): Optimum condition and adsorption isotherm study. Desalination Water Treat. 2017, 58, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikam, S.; Mandal, D.; Dabhade, P. LDF based parametric optimization to model fluidized bed adsorption of trichloroethylene on activated carbon particles. Particuology 2022, 65, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virmani, D.; Pandey, H. Comparative Analysis on Effect of Different SVM Kernel Functions for Classification. Lect. Notes Netw. Syst. 2023, 492, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Nemalipuri, P.; Vitankar, V.; Das, H.C. Multifluid Computational Fluid Dynamics Simulation for Sawdust Gasification inside an Industrial Scale Fluidized Bed Gasifier. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zimmerman, A.R.; Chen, H.; Wan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, B. Fixed bed column performance of Al-modified biochar for the removal of sulfamethoxazole and sulfapyridine antibiotics from wastewater. Chemosphere 2022, 305, 135475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, M.; Juela, D.M.; Cruzat, C.; Vanegas, E. Modeling and computational fluid dynamic simulation of acetaminophen adsorption using sugarcane bagasse. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juela, D.M. Comparison of the adsorption capacity of acetaminophen on sugarcane bagasse and corn cob by dynamic simulation. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2020, 30, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.