A Review on the Applications of Various Zeolites and Molecular Sieve Catalysts for Different Gas Phase Reactions: Present Trends in Research and Future Directions

Abstract

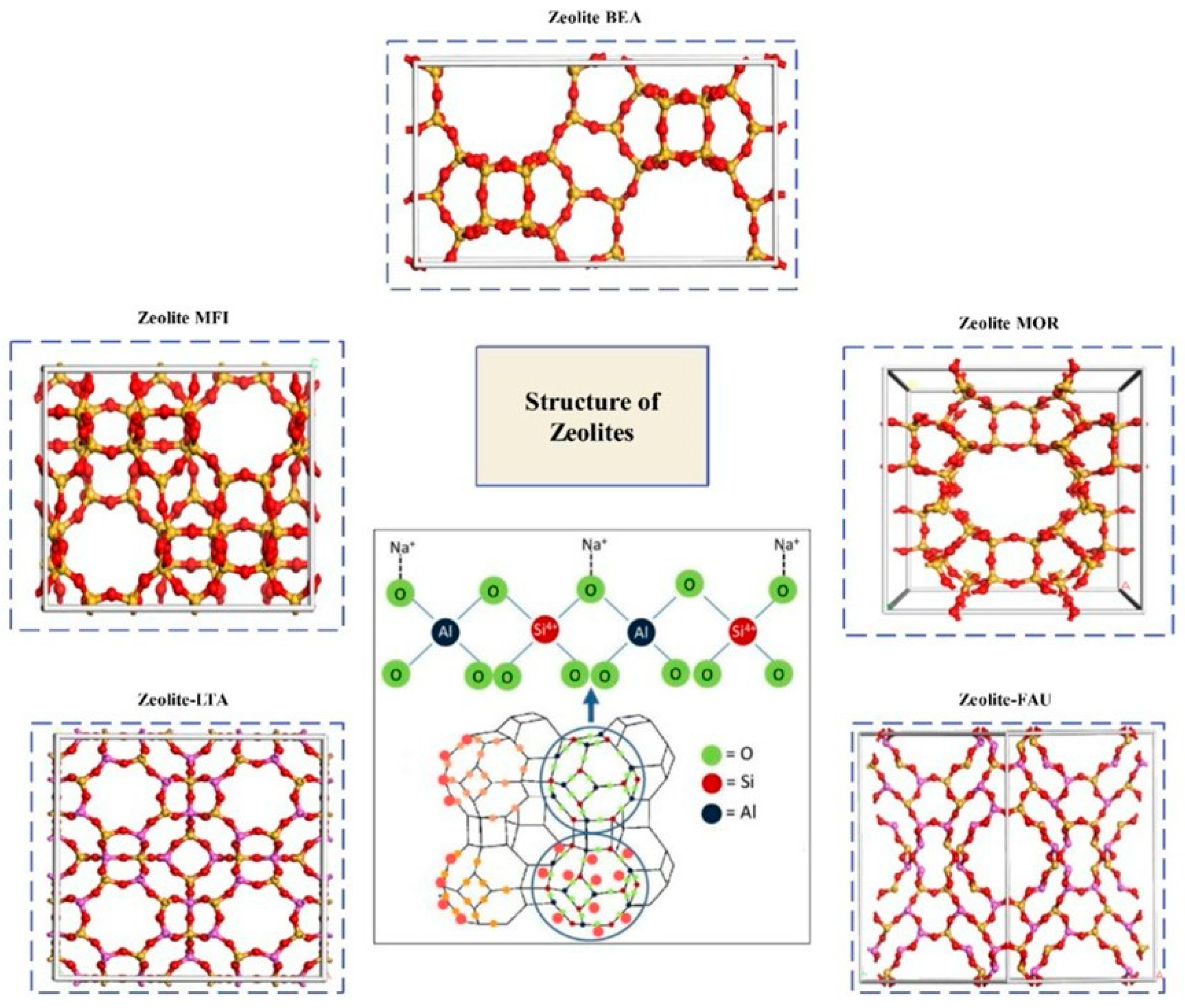

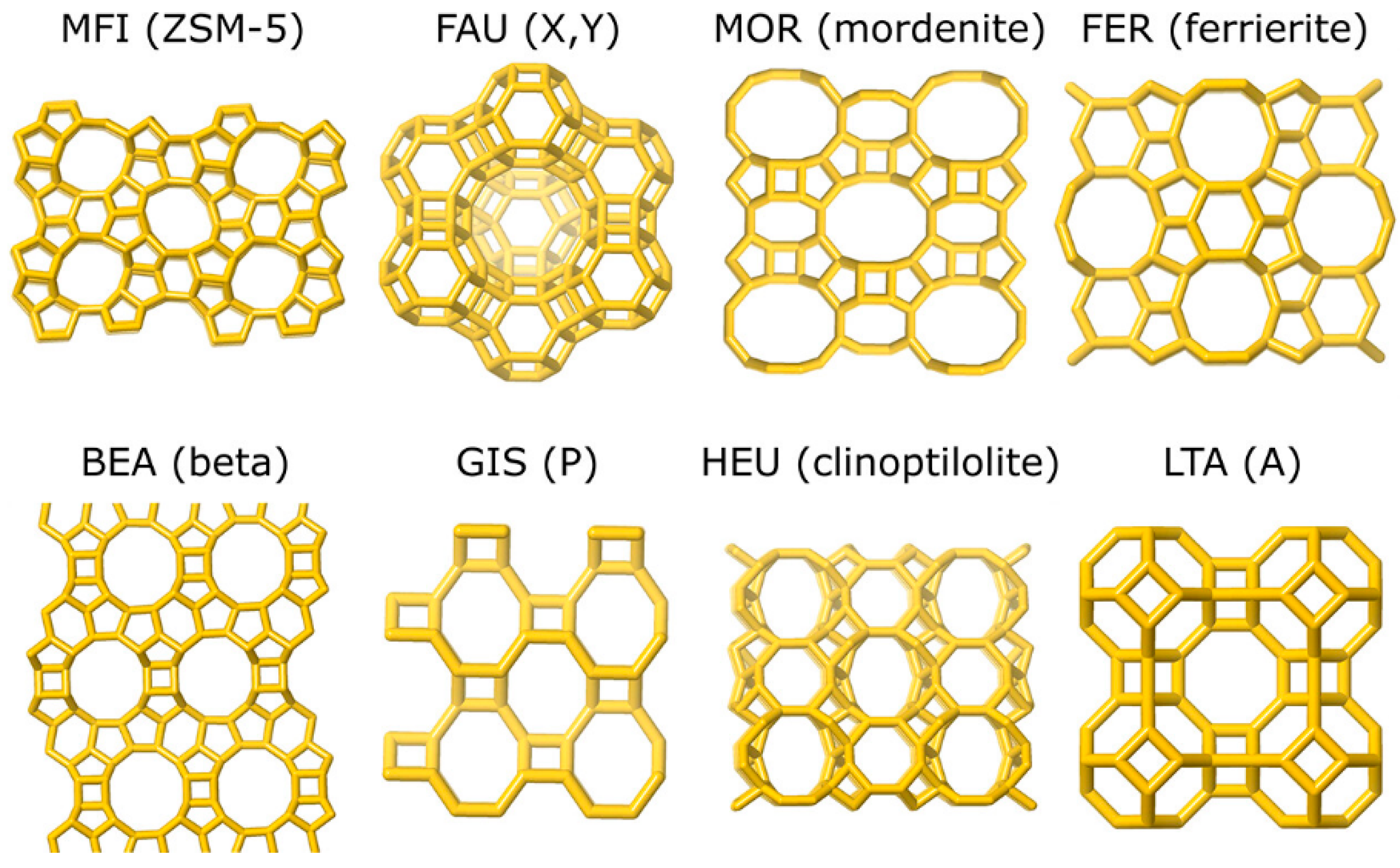

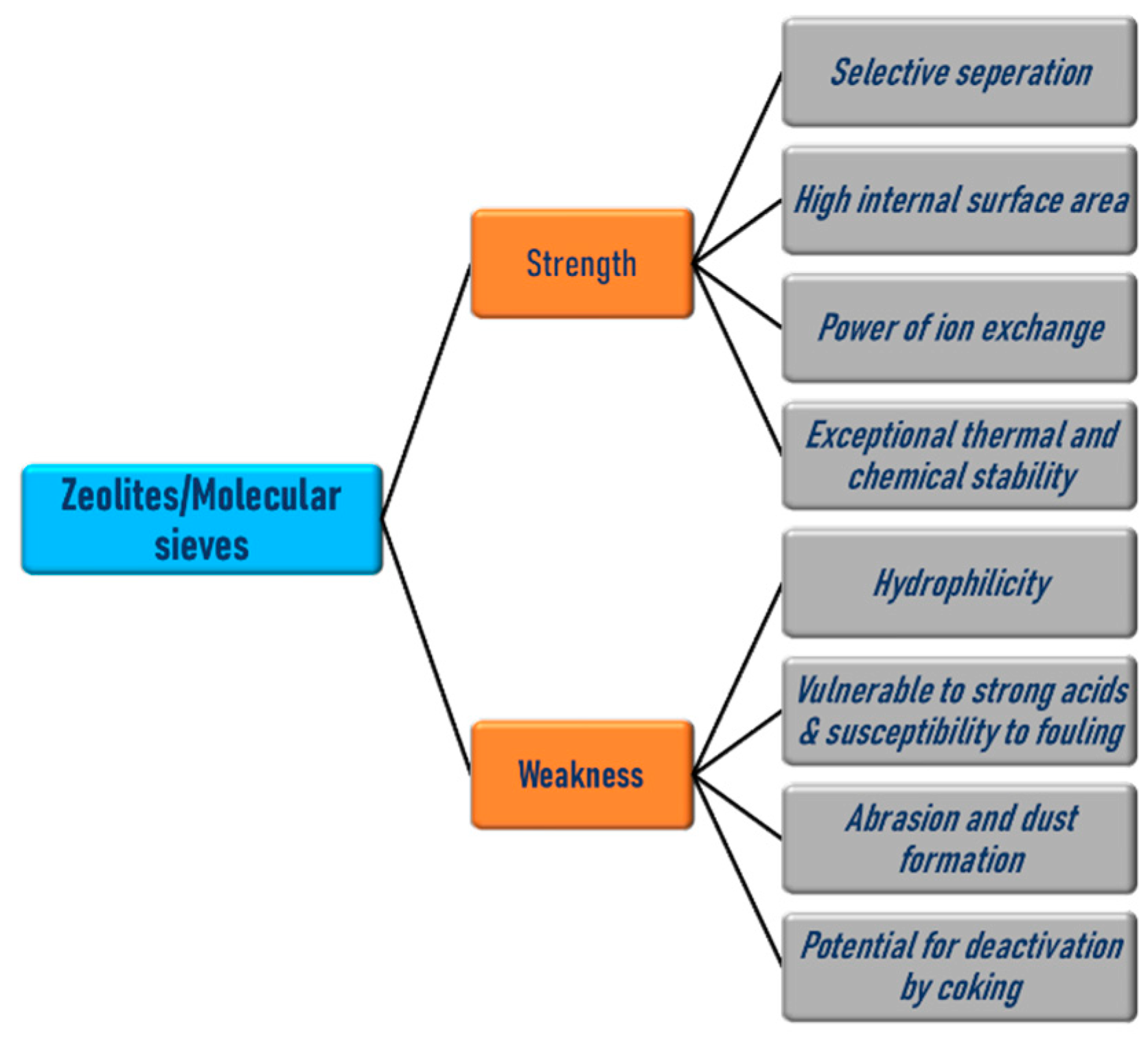

1. Introduction

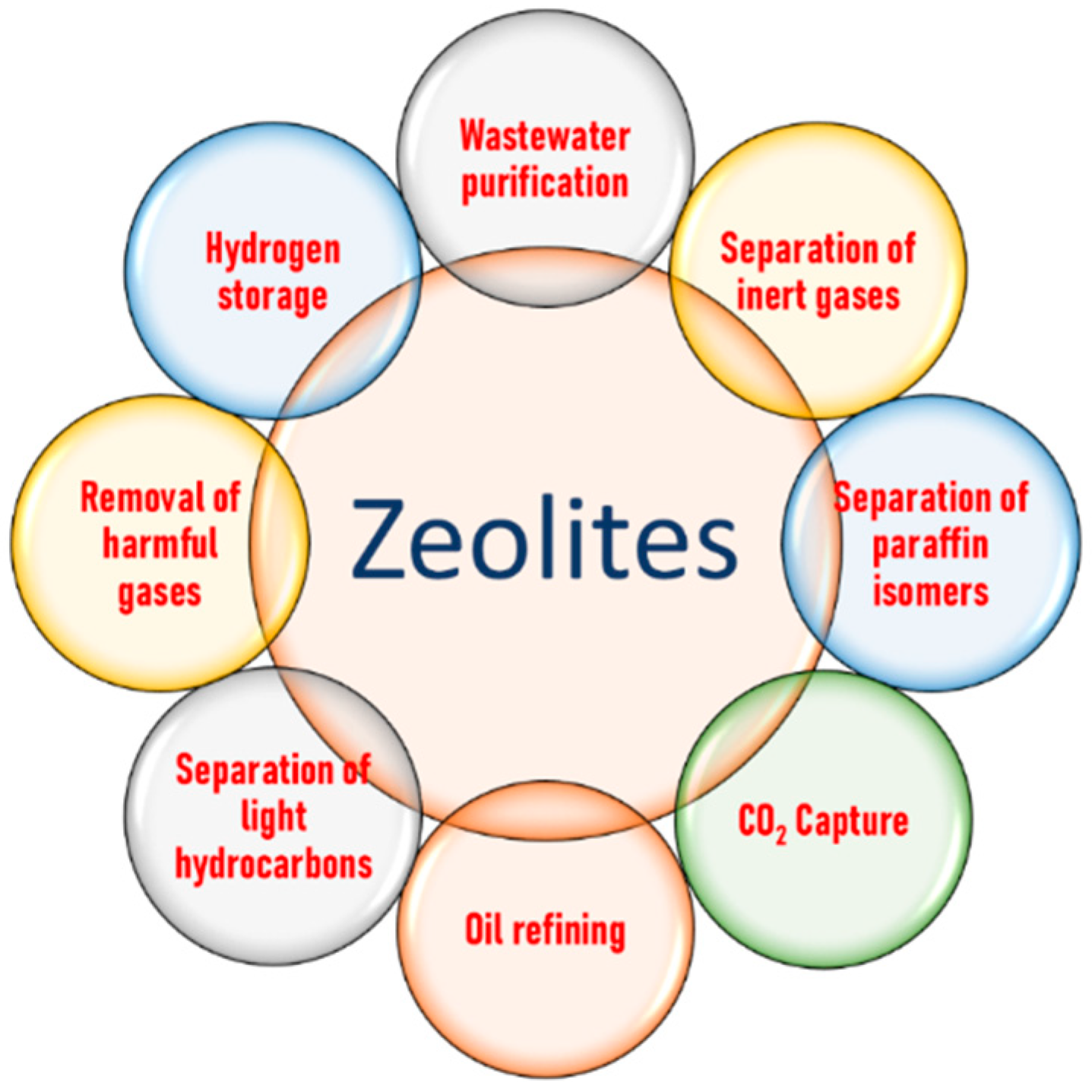

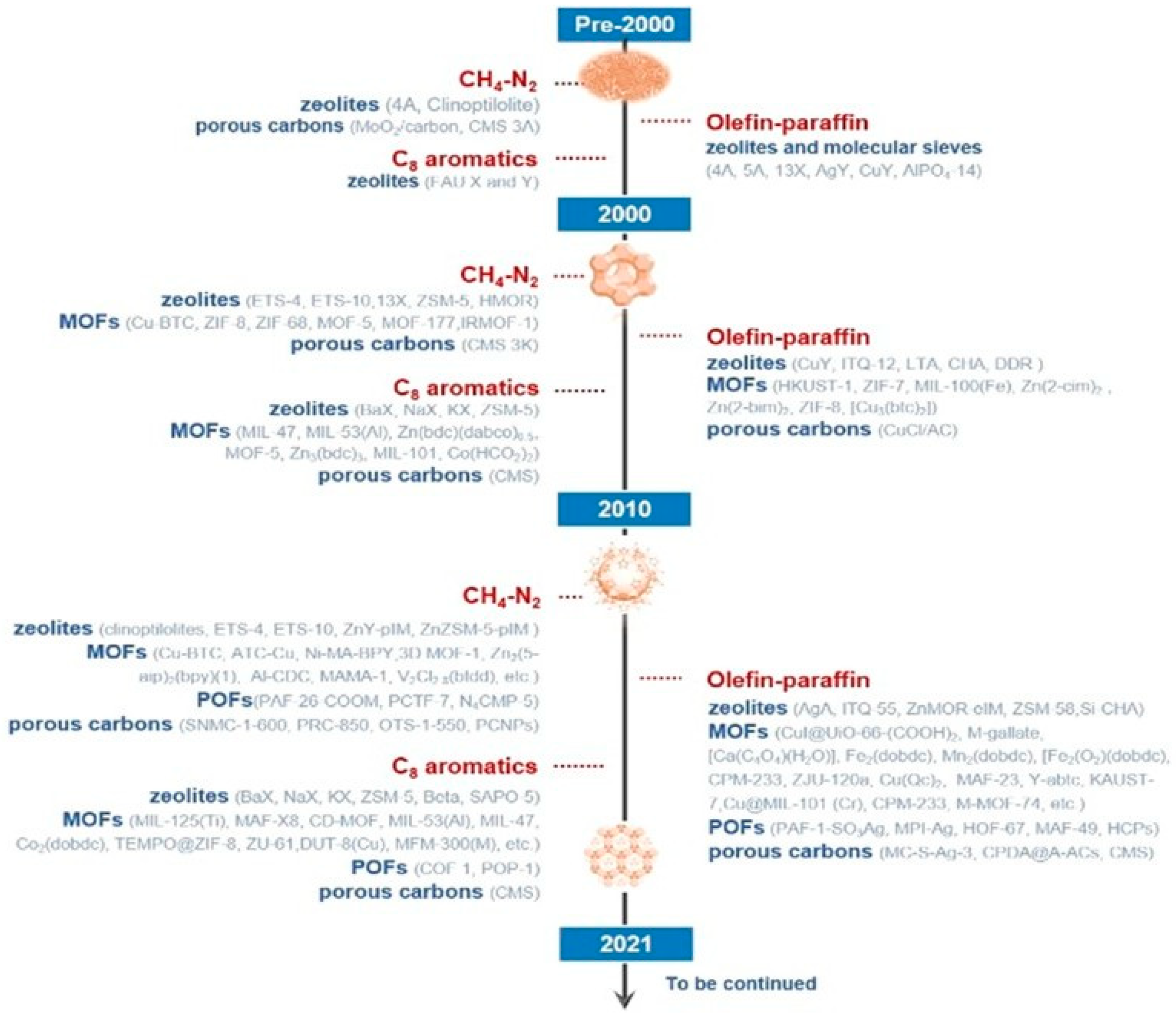

2. Zeolites and Molecular Sieves for Adsorption

2.1. Capture and Separation of Carbon Dioxide

2.1.1. Mechanism of Zeolites for CO2 Separation

- (i)

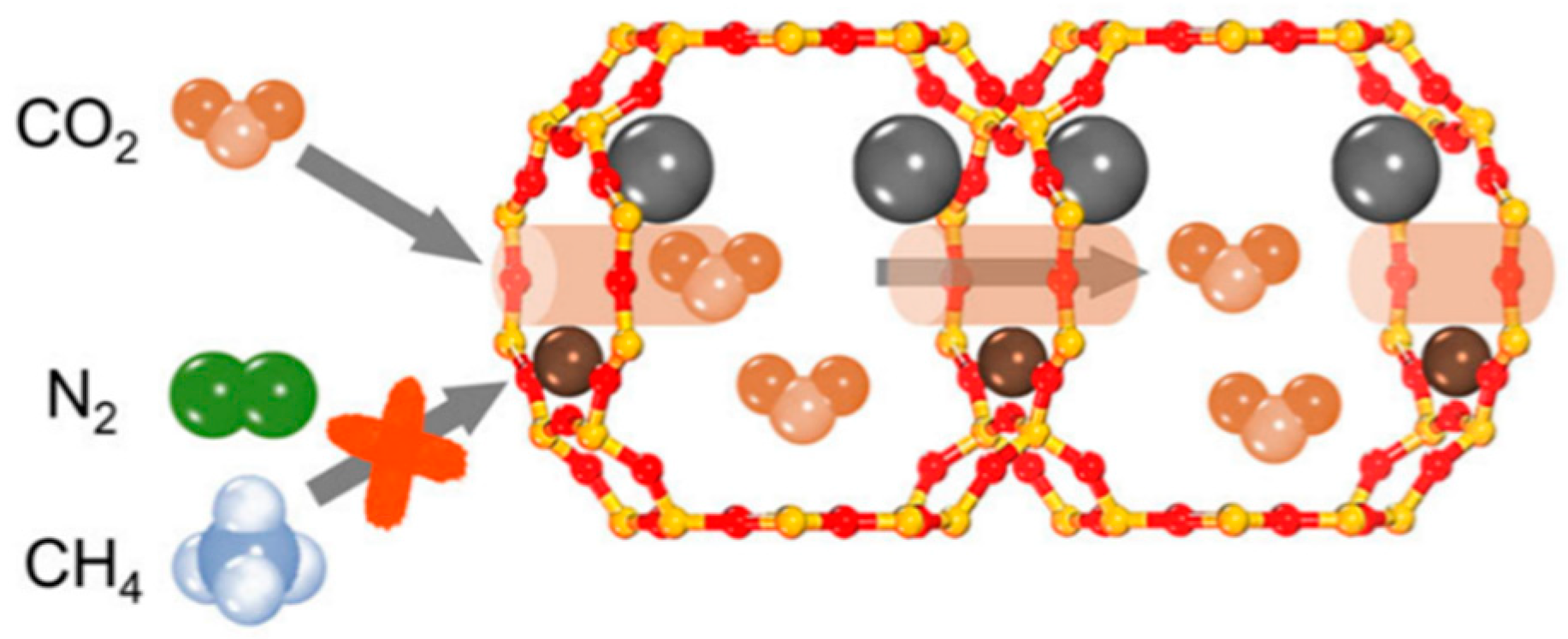

- Steric Effect

- (ii)

- Kinetic Effect

- (iii)

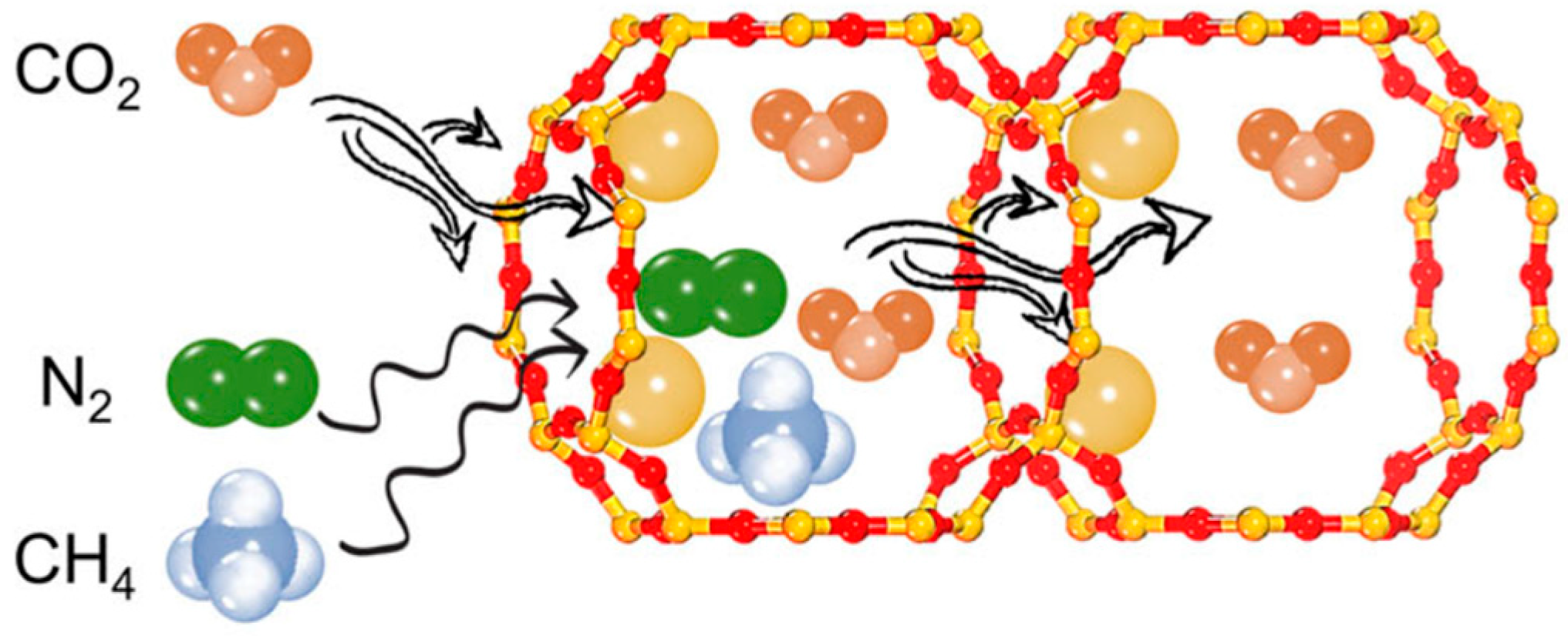

- Gating Effect

2.1.2. CO2 and H2 Separation from Water–Gas Shift (WGS) Reaction

2.1.3. CH4/CO/CO2 Separation

2.1.4. CO2/CO Separation

2.2. Separation of Inert Gases

2.3. Separation of Paraffin Isomers

2.4. Oil Refining

2.5. Separation of Light Hydrocarbons

2.6. Removal of Harmful Gases

2.6.1. Nitrogen Oxide Capture

2.6.2. Desulfurization

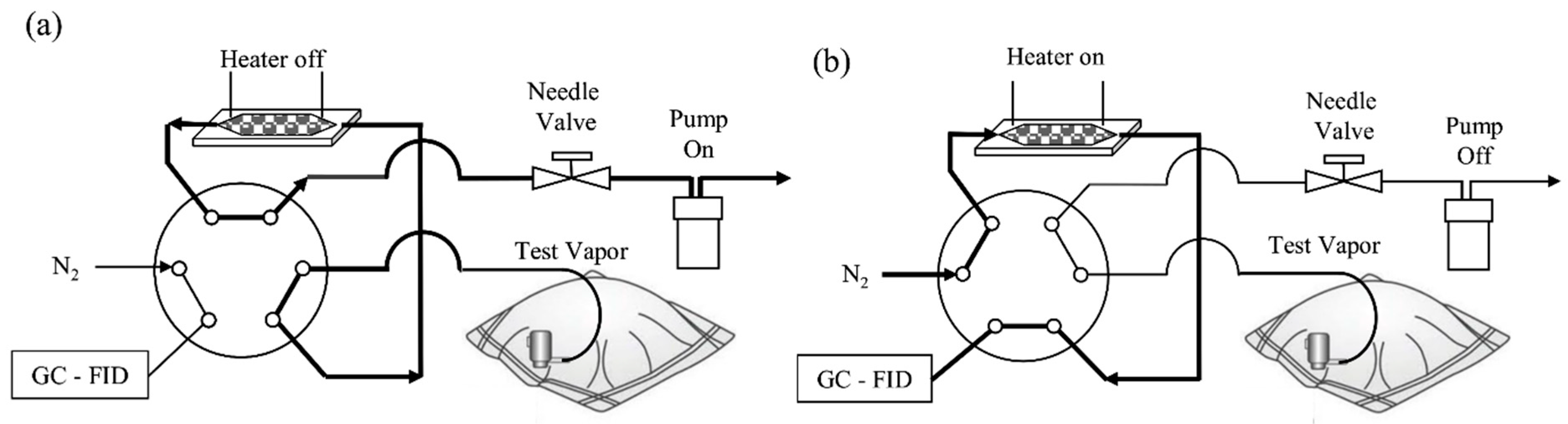

2.6.3. VOC Removal

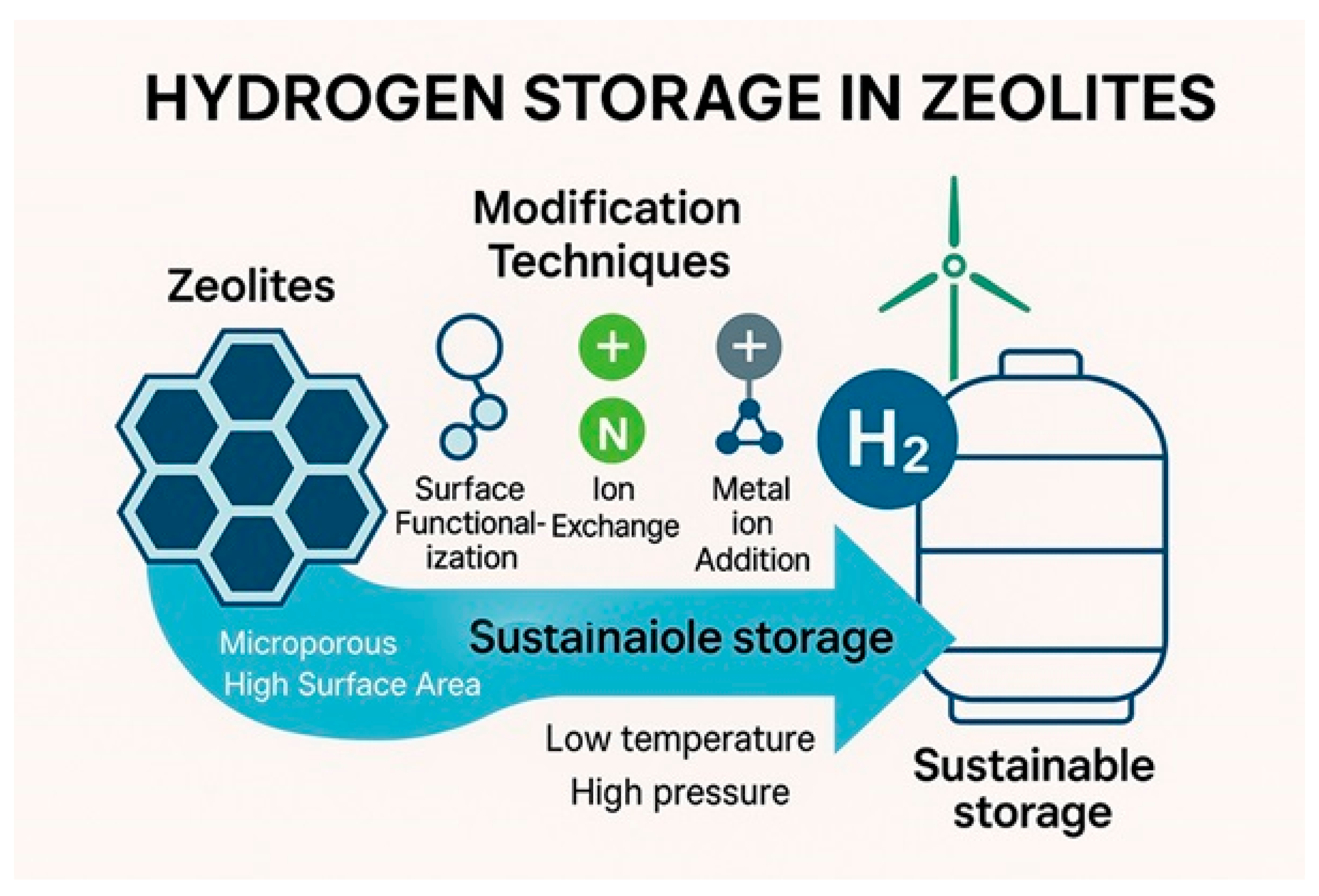

2.7. Hydrogen Storage

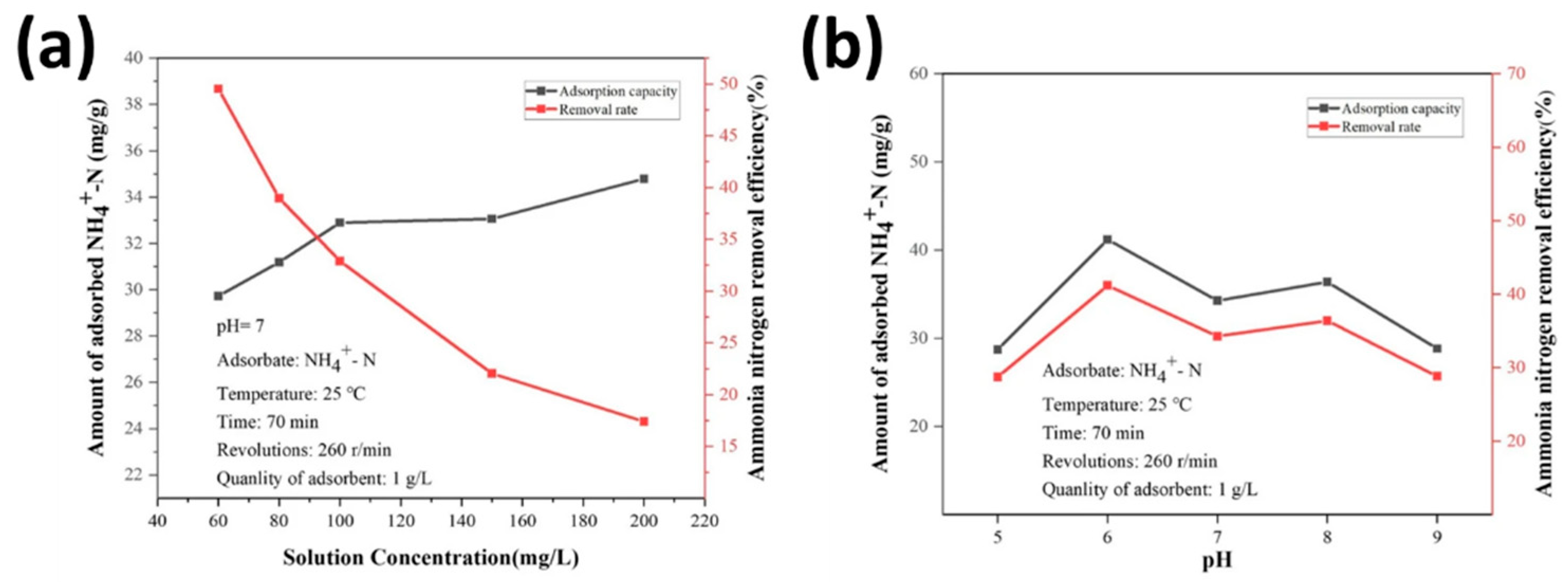

2.8. Wastewater Purification

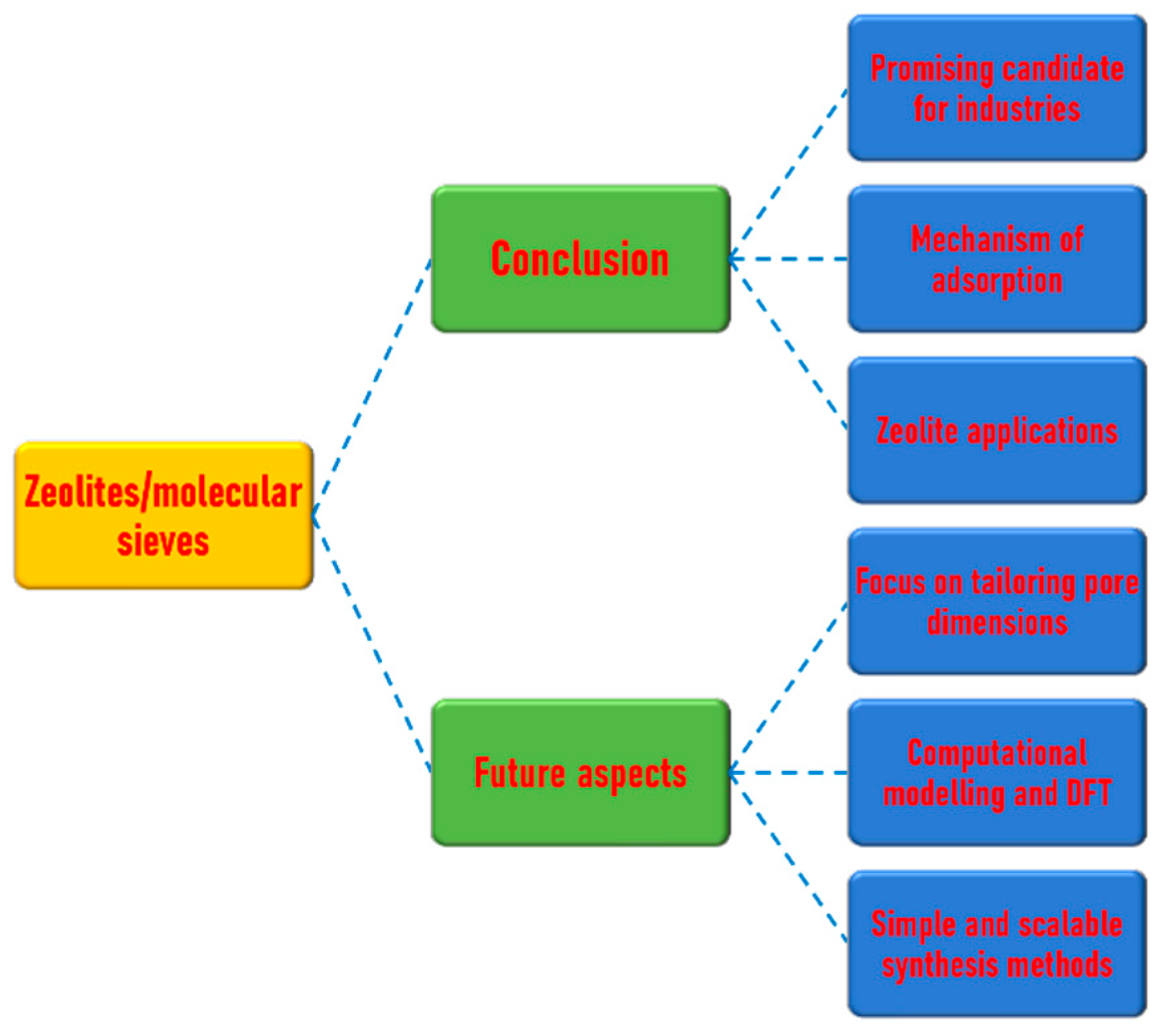

2.9. Conclusions and Future Aspects in Separation Process Using Zeolite

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VOCs | Volatile Organic Compounds |

| CCS | Carbon Capture and Sequestration |

| CCUS | Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage |

| WGS | Water Gas Shift Reaction |

| IGCC | Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle |

| MOF | Metal Organic Framework |

| GCMC | Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage |

| IAST | Ideal Adsorption Solution Theory |

| ISF | Ideal Separation Factor |

| ASF | Actual Adsorption Factor |

| MSRs | Molten Salt Reactors |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| CGE | Computable General Equilibrium |

| SNCR | Selective Noncatalytic Reduction |

| DMCHA+ | N,N-dimethylcyclohexylammonium |

| SCR | Selective Catalytic Reduction |

| PNA | Passive NOx Adsorbents |

| ADS | Adsorptive Desulfurization |

| DFT | Density Functional Theory |

References

- Dąbrowski, A. Adsorption—From Theory to Practice. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2001, 93, 135–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Tavakkoli Yaraki, M.; Karri, R.R. A Comprehensive Review of the Adsorption Mechanisms and Factors Influencing the Adsorption Process from the Perspective of Bioethanol Dehydration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 107, 535–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholl, D.S.; Lively, R.P. Seven Chemical Separations to Change the World. Nature 2016, 532, 435–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordala, N.; Wyszkowski, M. Zeolite Properties, Methods of Synthesis, and Selected Applications. Molecules 2024, 29, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, C.J. Properties and Applications of Zeolites. Sci. Prog. 2010, 93, 223–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, W.J.; Gil, B.; Tarach, K.A.; Góra-Marek, K. Top-down Engineering of Zeolite Porosity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2025, 54, 7484–7560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derbe, T.; Temesgen, S.; Bitew, M. A Short Review on Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications of Zeolites. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6637898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmanzadegan, F.; Ghaemi, A. A Comprehensive Review on Novel Zeolite-Based Adsorbents for Environmental Pollutant. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 17, 100617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millini, R.; Garbarino, G. Zeolites: Historical Evolution and Current Relevance. In Zeolites: From Fundamentals to Emerging Applications; Serrano, D.P., Čejka, J., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2025; pp. 1–33. ISBN 978-1-83767-545-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, A.M. An Overview of Zeolites: From Historical Background to Diverse Applications. Molecules 2025, 30, 4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, Q.; Lu, P.; Yang, X.; Valtchev, V. Zeolites for the Environment. Green Carbon 2024, 2, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Lv, Y.; Jing, T.; Gao, X.; Gu, Z.; Li, S.; Ao, H.; Fang, D. Recent Progress on the Synthesis and Applications of Zeolites from Industrial Solid Wastes. Catalysts 2024, 14, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wen, H.-M.; Zhou, W.; Chen, B. Porous Metal–Organic Frameworks for Gas Storage and Separation: What, How, and Why? J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 3468–3479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Fuku, K.; Ikenaga, N.; Sharaf, M.; Nakagawa, K. Recent Progress and Challenges in the Field of Metal–Organic Framework-Based Membranes for Gas Separation. Compounds 2024, 4, 141–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Botella, E.; Valencia, S.; Rey, F. Zeolites in Adsorption Processes: State of the Art and Future Prospects. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 17647–17695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Zones, S.I. Post-Synthetic Treatment and Modification of Zeolites. In Zeolites and Catalysis; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 155–170. ISBN 9783527630295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Kim, N.S.; Numan, M.; Kim, J.-C.; Cho, H.S.; Cho, K.; Jo, C. Postsynthetic Modification of Zeolite Internal Surface for Sustainable Capture of Volatile Organic Compounds under Humid Conditions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 53925–53934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, D.G.; Langerak, J.; Pescarmona, P.P. Zeolites as Selective Adsorbents for CO2 Separation. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 2634–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, T.; Patel, S.; Kulkarni, M.; Singh, Y.R.; Khodakiya, A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Prajapati, B.G. Zeolite-Based Nanoparticles Drug Delivery Systems in Modern Pharmaceutical Research and Environmental Remediation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servatan, M.; Zarrintaj, P.; Mahmodi, G.; Kim, S.-J.; Ganjali, M.R.; Saeb, M.R.; Mozafari, M. Zeolites in Drug Delivery: Progress, Challenges and Opportunities. Drug Discov. Today 2020, 25, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Reyes, M.; Almazán-Sánchez, P.T.; Solache-Ríos, M. Radioactive Waste Treatments by Using Zeolites. A Short Review. J. Environ. Radioact. 2021, 233, 106610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosino, F.; Gargiulo, N.; Della Peruta, G.; Gravino, C.; Gagliardo, G.; Pisciotta, F.; Esposito, S.; La Verde, G.; Caputo, D.; Pugliese, M. Study and Characterization of Zeolites for the Removal of Artificial Radionuclides in Wastewater Samples from Nuclear Power Plants. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 16, 100458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, A.A.; Len, T.; de Oliveira, A.D.; Costa, A.A.; Souza, A.R.; Costa, C.E.; Luque, R.; Rocha Filho, G.N.; Noronha, R.C.; Nascimento, L.A. Zeolites: A Theoretical and Practical Approach with Uses in (Bio)Chemical Processes. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warjurkar, T.; Gore, P.M.; Kandasubramanian, B. Zeolite-Coated Membranes for Efficient Separation of Oil-Water Mixture. Clean. Water 2025, 4, 100132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Rao, F.; Guo, Y.; Lu, Z.; Deng, W.; Li, G.; Zhang, H.; Qi, T.; Hu, G. CO2 Capture Using Low Silica X Zeolite Synthesized from Low-Grade Coal Gangue via a Two-Step Activation Method. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Liu, B.; Wang, B.; Duan, J.; Zhou, R. Directly Synthesized High-Silica CHA Zeolite for Efficient CO2/N2 Separation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 113036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldeeb, A.M.; Serag, E.; Elmowafy, M.; El-Khouly, M.E. PH-Responsive Zeolite-A/Chitosan Nanocarrier for Enhanced Ibuprofen Drug Delivery in Gastrointestinal Systems. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 289, 138879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, M.; Khosravi, S.; Ranjbar, A.; Mohammadi, M. Quercetin Loaded-Magnetic Zeolite Nano-Composite Material and Evaluate Its Anti-Cancer Effect. Naunyn. Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 13745–13754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathen, D.; Schmidt-Traub, H.; Simon, M. Gas Adsorption Isotherm for Dealuminated Zeolites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1997, 36, 3993–3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedli, H.; Bouzgarrou, S.M.; Hassani, R.; Sabi, E.; Slimi, K. Adsorption of CO2, CH4 and H2 onto Zeolite 13 X: Kinetic and Equilibrium Studies. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Jiang, N.; Zheng, H.; Wu, Y.; Heijman, S.G.J. Predicting Adsorption Isotherms of Organic Micropollutants by High-Silica Zeolite Mixtures. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 282, 120009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; E, J.; Han, W.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, X.; Han, D. Key Technology and Application Analysis of Zeolite Adsorption for Energy Storage and Heat-Mass Transfer Process: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 110954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Davis, M.E. Carbon Dioxide Capture with Zeotype Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51, 9340–9370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.Y. A Techno-Economic Review on Carbon Capture, Utilisation and Storage Systems for Achieving a Net-Zero CO2 Emissions Future. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2022, 3, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Peu, S.D.; Hossain, M.S.; Nahid, M.M.A.; Bin Karim, F.R.; Chowdhury, H.; Porag, M.H.; Argha, D.B.P.; Saha, S.; Islam, A.R.M.T.; et al. Advancements in Adsorption Based Carbon Dioxide Capture Technologies- A Comprehensive Review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Tian, Y.; Wu, W.; Liu, Z.; Fu, W.; Kung, C.-W.; Shang, J. Development of Zeolite Adsorbents for CO2 Separation in Achieving Carbon Neutrality. npj Mater. Sustain. 2024, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

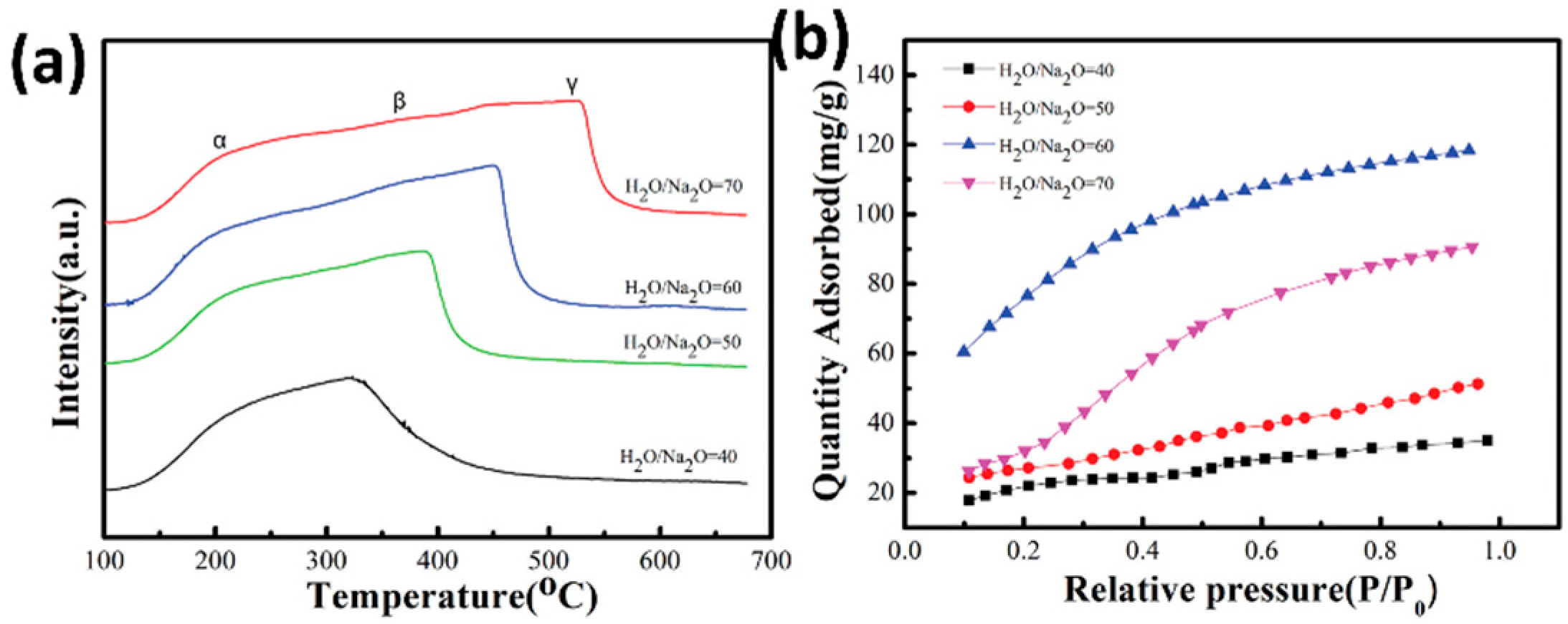

- Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Li, N.; Tan, T.; Zhang, F.; Sun, M.; Liu, Q. Effect of Synthesis Conditions on the Properties of 13X Zeolites for CO2 Adsorption. Environ. Pollut. Bioavailab. 2024, 36, 2387683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.T. Sorbents for Applications. In Adsorbents: Fundamentals and Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 280–381. ISBN 9780471444091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-R.; Kuppler, R.J.; Zhou, H.-C. Selective Gas Adsorption and Separation in Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1477–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonenfant, D.; Kharoune, M.; Niquette, P.; Mimeault, M.; Hausler, R. Advances in Principal Factors Influencing Carbon Dioxide Adsorption on Zeolites. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2008, 9, 13007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thang, H.V.; Grajciar, L.; Nachtigall, P.; Bludský, O.; Areán, C.O.; Frýdová, E.; Bulánek, R. Adsorption of CO2 in FAU Zeolites: Effect of Zeolite Composition. Catal. Today 2014, 227, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaieb, A.H.; Jasim, F.T.; Abdulrahman, A.A.; Khuder, I.M.; Gheni, S.A.; Fattah, I.M.R.; Karakullukcu, N.T. Tailoring Zeolites for Enhanced Post-Combustion CO2 Capture: A Critical Review. Curr. Res. Green Sustain. Chem. 2025, 10, 100451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhao, X.; Sun, L.; Liu, X. Adsorption Separation of Carbon Dioxide, Methane and Nitrogen on Monoethanol Amine Modified β-Zeolite. J. Nat. Gas Chem. 2009, 18, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remy, T.; Peter, S.A.; Van Tendeloo, L.; Van der Perre, S.; Lorgouilloux, Y.; Kirschhock, C.E.A.; Baron, G.V.; Denayer, J.F.M. Adsorption and Separation of CO2 on KFI Zeolites: Effect of Cation Type and Si/Al Ratio on Equilibrium and Kinetic Properties. Langmuir 2013, 29, 4998–5012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lou, C.; Yuan, J.; Tang, X.; Fan, Y.; Qi, J.; Zhang, R.; Peng, P.; Liu, G.; Xu, S.; et al. Molecular Self-Gating Inside a Zeolite Catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 6126–6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraj, E.; Ciahotný, K.; Hlinčík, T. The Water Gas Shift Reaction: Catalysts and Reaction Mechanism. Fuel 2021, 288, 119817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraj, E.; Ciahotný, K.; Hlinčík, T. Advanced Catalysts for the Water Gas Shift Reaction. Crystals 2022, 12, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, A.; Criscuoli, A.; Santella, F.; Drioli, E. Membrane Reactor for Water Gas Shift Reaction. Gas Sep. Purif. 1996, 10, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, A.; Caravella, A.; Barbieri, G.; Drioli, E. Simulation Study of Water Gas Shift Reaction in a Membrane Reactor. J. Memb. Sci. 2007, 306, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Yang, S.; Reddy, G.K.; Smirniotis, P.; Dong, J. Zeolite Membrane Reactor for High-Temperature Water-Gas Shift Reaction: Effects of Membrane Properties and Operating Conditions. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 4471–4480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Dong, X.; Lin, Y.S. Highly Stable Bilayer MFI Zeolite Membranes for High Temperature Hydrogen Separation. J. Memb. Sci. 2014, 450, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Zhao, L.; Xu, D.; Ciora, R.; Liu, P.K.T.; Manousiouthakis, V.I.; Tsotsis, T.T. A Carbon Molecular Sieve Membrane-Based Reactive Separation Process for Pre-Combustion CO2 Capture. J. Memb. Sci. 2020, 605, 118028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, G.M.; Ku, C.-E.; Zhang, C. Hyperselective Carbon Membranes for Precise High-Temperature H2 and CO2 Separation. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadt7512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Shang, J.; Choi, J.; Yip, A.C.K. Generation and Extraction of Hydrogen from Low-Temperature Water-Gas-Shift Reaction by a ZIF-8-Based Membrane Reactor. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 280, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Hong, Z.; Gu, X.; Xu, N. Hydrogen-Selective Zeolite Membrane Reactor for Low Temperature Water Gas Shift Reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 197, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

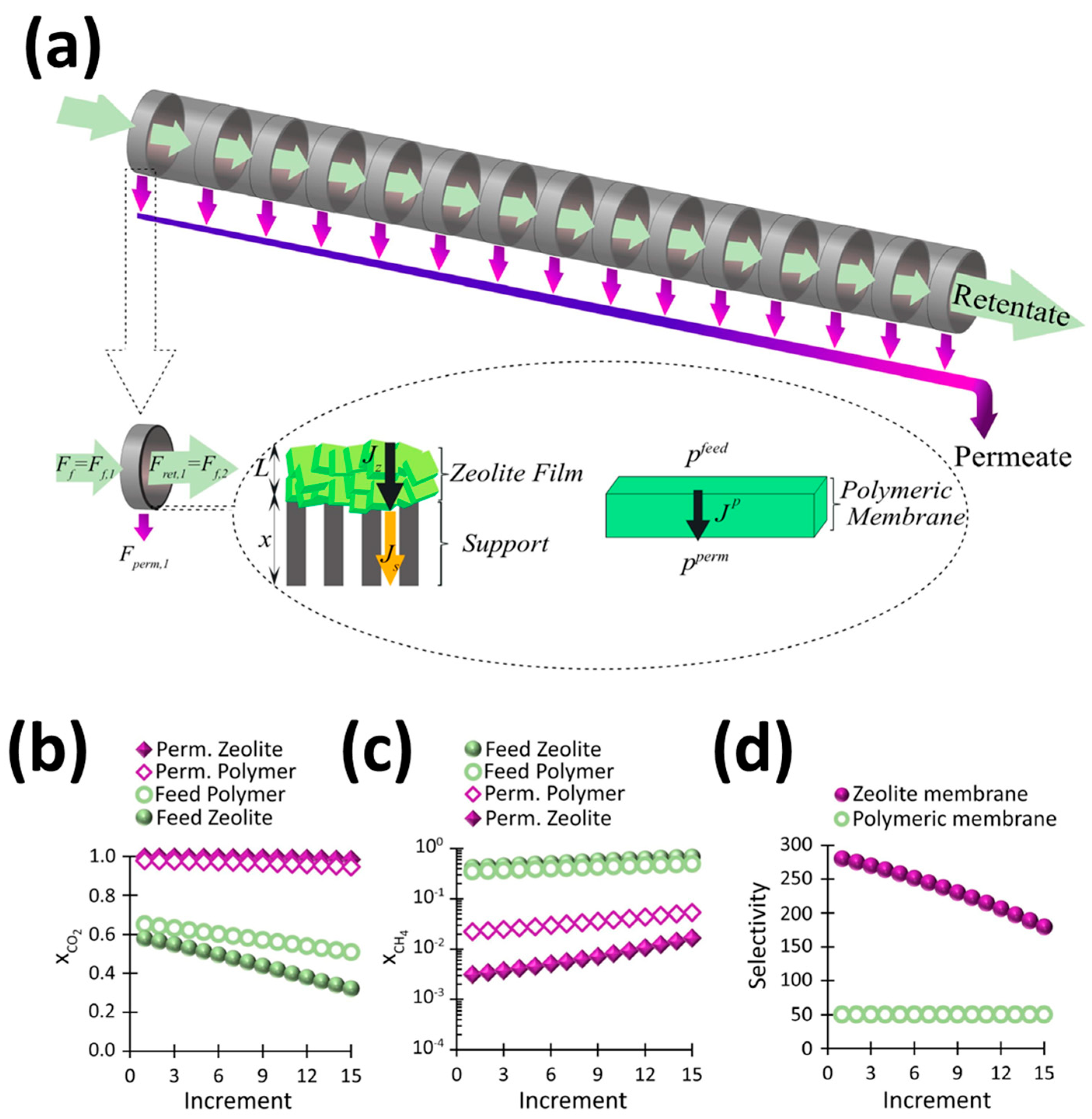

- Sinaei Nobandegani, M.; Yu, L.; Hedlund, J. Zeolite Membrane Process for Industrial CO2/CH4 Separation. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 137223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Qian, W.; Ma, H.; Ying, W.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, P. A Theoretical Study on the Separation of CO2/CH4 through MFI Zeolite. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2023, 1228, 114272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Naddaf, Q.; Rownaghi, A.A.; Rezaei, F. Multicomponent Adsorptive Separation of CO2, CO, CH4, N2, and H2 over Core-Shell Zeolite-5A@MOF-74 Composite Adsorbents. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 384, 123251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, B.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z. Development of Enhanced CO2 Adsorbents on Functionalized MCM-41 with Hybrid Amines. New J. Chem. 2025, 49, 7384–7392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Koros, W.J. Ultraselective Carbon Molecular Sieve Membranes with Tailored Synergistic Sorption Selective Properties. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1701631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tin, P.S.; Chung, T.-S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R. Separation of CO2/CH4 through Carbon Molecular Sieve Membranes Derived from P84 Polyimide. Carbon N. Y. 2004, 42, 3123–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Xing, Y.; Tian, J.; Su, W.; Sun, F.-Z.; Liu, Y. Insights into the Adsorption Performance and Separation Mechanisms for CO2 and CO on NaX and CaA Zeolites by Experiments and Simulation. Fuel 2023, 337, 127179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Su, W.; Xing, Y.; Hao, L.; Sun, Y.; Cai, Y. Experimental and Simulation Evaluation of CO2/CO Separation under Different Component Ratios in Blast Furnace Gas on Zeolites. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472, 144579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

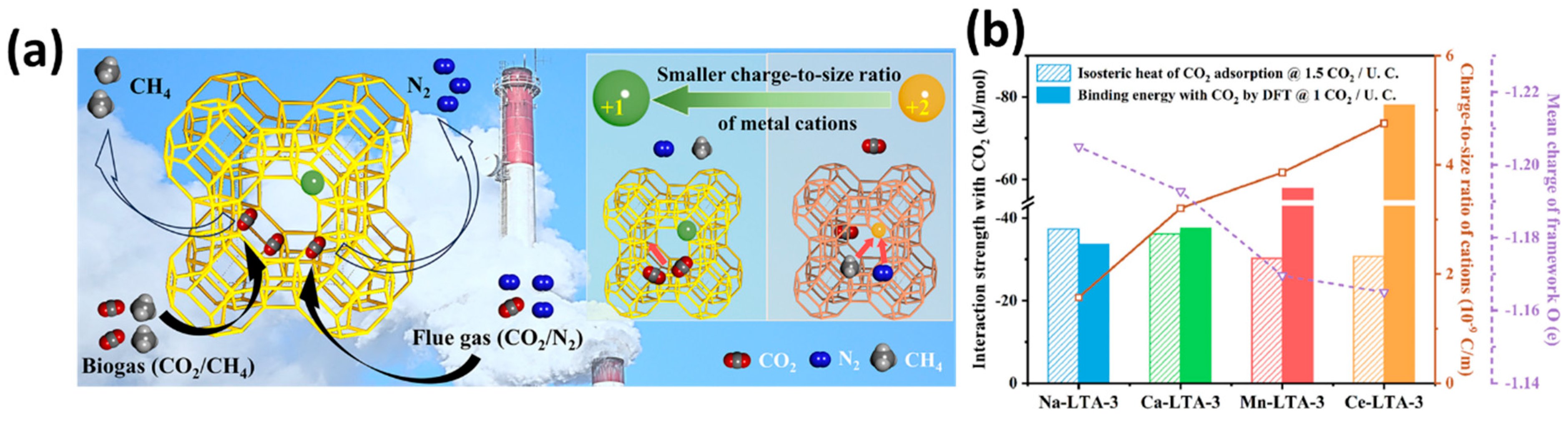

- Tao, Z.; Tian, Y.; Hanif, A.; Chan, V.; Gu, Q.; Shang, J. Metal Cation-Exchanged LTA Zeolites for CO2/N2 and CO2/CH4 Separation: The Roles of Gas-Framework and Gas-Cation Interactions. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2023, 8, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Pham, T.; Porosoff, M.D.; Lobo, R.F. ZK-5: A CO2-Selective Zeolite with High Working Capacity at Ambient Temperature and Pressure. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 2237–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Li, G.; Singh, R.; Gu, Q.; Nairn, K.M.; Bastow, T.J.; Medhekar, N.; Doherty, C.M.; Hill, A.J.; Liu, J.Z.; et al. Discriminative Separation of Gases by a “Molecular Trapdoor” Mechanism in Chabazite Zeolites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 19246–19253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomino, M.; Corma, A.; Rey, F.; Valencia, S. New Insights on CO2−Methane Separation Using LTA Zeolites with Different Si/Al Ratios and a First Comparison with MOFs. Langmuir 2010, 26, 1910–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozinska, M.M.; Mangano, E.; Greenaway, A.G.; Fletcher, R.; Thompson, S.P.; Murray, C.A.; Brandani, S.; Wright, P.A. Cation Control of Molecular Sieving by Flexible Li-Containing Zeolite Rho. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 19652–19662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, V.M.; Bruce, E.L.; Verbraeken, M.C.; Scott, A.R.; Casteel, W.J.J.; Brandani, S.; Wright, P.A. Triggered Gate Opening and Breathing Effects during Selective CO2 Adsorption by Merlinoite Zeolite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 12744–12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydani, A.; Brunetti, A.; Maghsoudi, H.; Barbieri, G. CO2 Separation from Binary Mixtures of CH4, N2, and H2 by Using SSZ-13 Zeolite Membrane. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 256, 117796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, W.; Du, Y.; Wu, T.; Gao, F.; Wang, B.; Duan, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, R. High-Flux CHA Zeolite Membranes for H2 Separations. J. Memb. Sci. 2018, 565, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafie, A.H.; An, W.; Hosseinzadeh Hejazi, S.A.; Sawada, J.A.; Kuznicki, S.M. Natural Zeolite-Based Cement Composite Membranes for H2/CO2 Separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 88, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIU, Z.; TENG, Y.; ZHANG, K.; CAO, Y.; PAN, W. CO2 Adsorption Properties and Thermal Stability of Different Amine-Impregnated MCM-41 Materials. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2013, 41, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

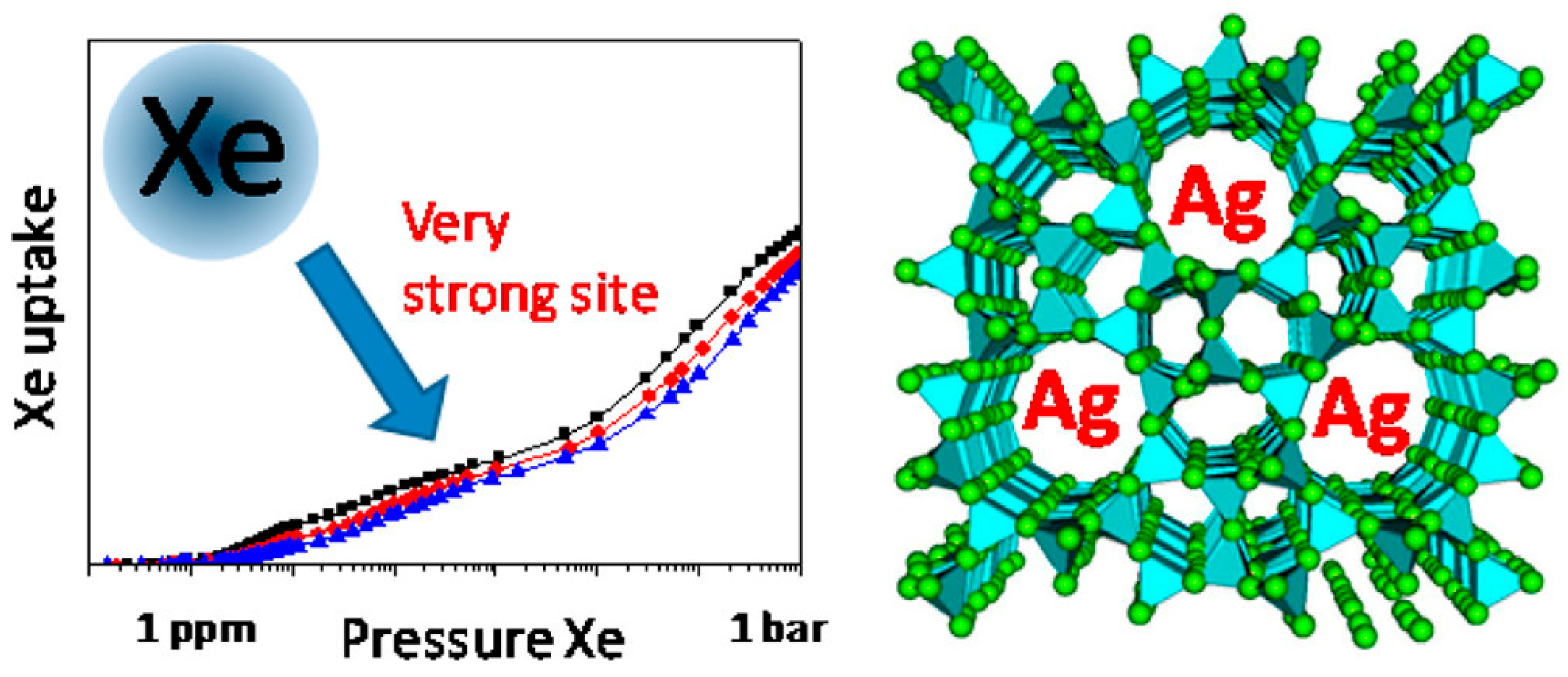

- Deliere, L.; Topin, S.; Coasne, B.; Fontaine, J.-P.; De Vito, S.; Den Auwer, C.; Solari, P.L.; Daniel, C.; Schuurman, Y.; Farrusseng, D. Role of Silver Nanoparticles in Enhanced Xenon Adsorption Using Silver-Loaded Zeolites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 25032–25040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, C.; Elbaraoui, A.; Aguado, S.; Springuel-Huet, M.-A.; Nossov, A.; Fontaine, J.-P.; Topin, S.; Taffary, T.; Deliere, L.; Schuurman, Y.; et al. Xenon Capture on Silver-Loaded Zeolites: Characterization of Very Strong Adsorption Sites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 15122–15129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Zong, Z.; Elsaidi, S.K.; Jasinski, J.B.; Krishna, R.; Thallapally, P.K.; Carreon, M.A. Kr/Xe Separation over a Chabazite Zeolite Membrane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 9791–9794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Liu, X.; Dai, G.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Yang, P.; Li, Y.; Yu, X.; Chen, Y.; Shi, X.; et al. Smooth Pore Surface in Zeolites for Krypton Capture under Humid Conditions. Green Chem. Eng. 2025, 6, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lian, X.; Yue, B.; Xu, S.; Wu, G.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L. Control of Zeolite Local Polarity toward Efficient Xenon/Krypton Separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 8335–8342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Wu, X.; Liu, Q.; Gong, Y.; Qi, S.; Dong, S.; Mao, Z.; Xiong, S.; Hu, S. Suitable Pore Confinement with Multiple Interactions in a Low-Cost Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework for Efficient Xe Capture and Separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 128868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirngruber, G.D.; Laroche, C.; Maricar-Pichon, M.; Rouleau, L.; Bouizi, Y.; Valtchev, V. Core–Shell Zeolite Composite with Enhanced Selectivity for the Separation of Branched Paraffin Isomers. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 169, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, M.; Alaerts, L.; Vermoortele, F.; Ameloot, R.; Couck, S.; Finsy, V.; Denayer, J.F.M.; De Vos, D.E. Separation of C5-Hydrocarbons on Microporous Materials: Complementary Performance of MOFs and Zeolites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 2284–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Wang, H.; Dong, Q.; Li, Y.; Xiang, H. A Review on the Research Progress of Zeolite Catalysts for Heavy Oil Cracking. Catalysts 2025, 15, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primo, A.; Garcia, H. Zeolites as Catalysts in Oil Refining. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 7548–7561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva, C.; Rana, M.S.; Trejo, F.; Ancheyta, J. On the Use of Acid-Base-Supported Catalysts for Hydroprocessing of Heavy Petroleum. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 7448–7466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, Y.I.I.; Galiakhmetova, L.K.; Sharifullin, A.V.; Tajik, A.; Mukhamatdinova, R.E.; Davletshin, R.R.; Vakhin, A. V Comparative Study of the Catalytic Effects of Al(CH3COO)3 and Al2(SO4)3 on Heavy Oil Aquathermolysis in CO2 and N2 Atmospheres. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2025, 699, 120247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

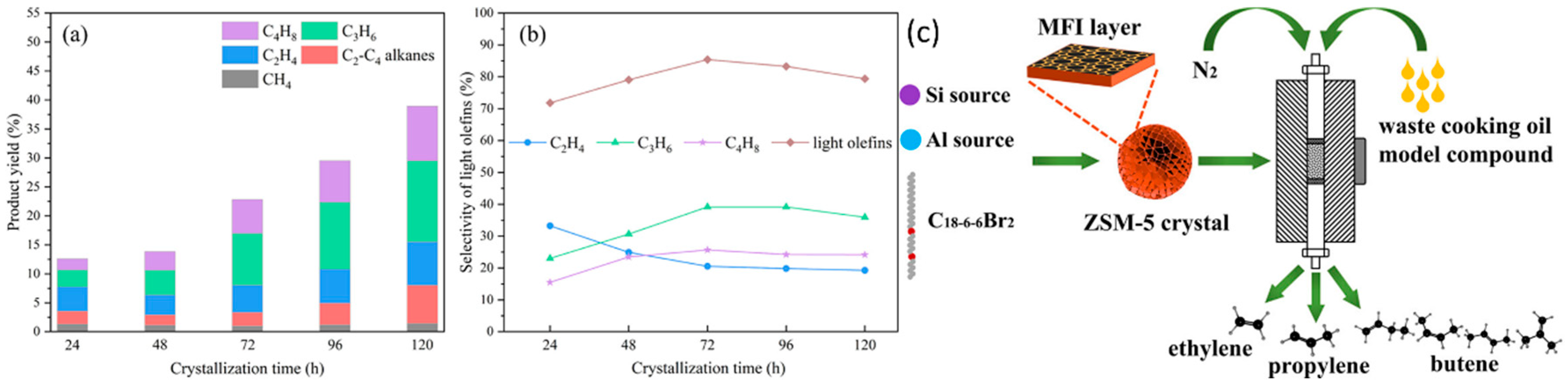

- Luo, W.; Liu, H.; Yuan, H.; Liu, H. Synthesis of Two-Dimensional Zeolite Nanosheets Applied to the Catalytic Cracking of a Waste Cooking Oil Model Compound to Produce Light Olefins. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 17054–17065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Sun, H. Progress in the Separation and Purification of Carbon Hydrocarbon Compounds Using MOFs and Molecular Sieves. Separations 2023, 10, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Qian, S.; Wang, X.; Cui, X.; Chen, B.; Xing, H. Energy-Efficient Separation Alternatives: Metal–Organic Frameworks and Membranes for Hydrocarbon Separation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 5359–5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Weckhuysen, B.M. Separation and Purification of Hydrocarbons with Porous Materials. Angew. Chemie 2021, 133, 19078–19097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuah, C.Y.; Bae, T.-H. Recent Advances in Mixed-Matrix Membranes for Light Hydrocarbon (C1–C3) Separation. Membranes 2022, 12, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Miao, G.; Yang, C.; Huang, J.; Li, X.; Du, S.; Xiao, J. Fast Size-Sieving Separation of C2H4/C2H6 by Pore Engineering of Scalable Carbon Molecular Sieve Granules. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2026, 320, 122640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboor, F.H.; Hajizadeh, O. Separation of Light Hydrocarbons: A Minireview. Adv. J. Chem. Sect. A 2020, 3, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Han, X.; Li, W.; Liu, S.; Yao, S.; Wang, C.; Shi, W.; da-Silva, I.; Manuel, P.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Control of Zeolite Pore Interior for Chemoselective Alkyne/Olefin Separations. Science 2020, 368, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

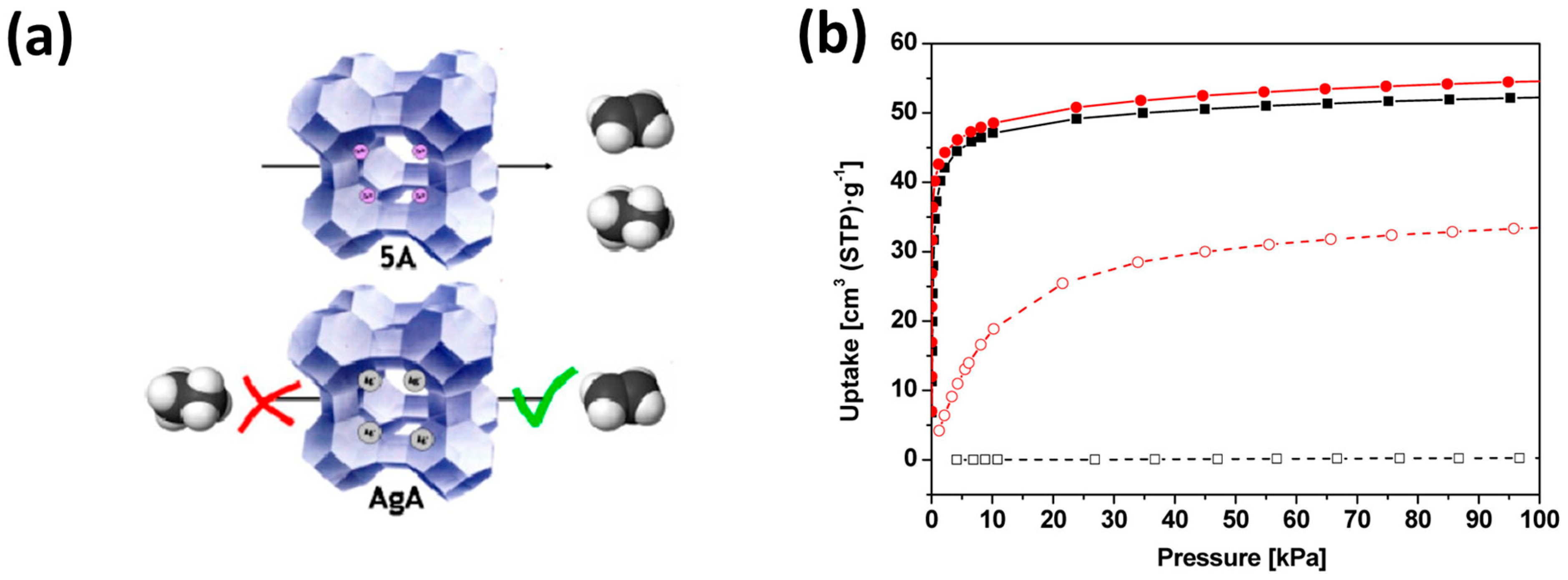

- Aguado, S.; Bergeret, G.; Daniel, C.; Farrusseng, D. Absolute Molecular Sieve Separation of Ethylene/Ethane Mixtures with Silver Zeolite A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 14635–14637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Yue, B.; Nie, Y.; Chai, Y.; Wu, G.; Li, J.; Han, X.; Day, S.J.; Thompson, S.P.; et al. Cascade Adsorptive Separation of Light Hydrocarbons by Commercial Zeolites. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 72, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, E.; Niculescu, V.-C. Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) as Environmental Pollutants: Occurrence and Mitigation Using Nanomaterials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Outdoor Air Pollution Will Cause up to 9 Million Premature Deaths a Year by 2060, Says the OECD|World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2016/08/air-pollution-deaths-oecd/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Taha, S.S.; Idoudi, S.; Alhamdan, N.; Ibrahim, R.H.; Surkatti, R.; Amhamed, A.; Alrebei, O.F. Comprehensive Review of Health Impacts of the Exposure to Nitrogen Oxides (NOx), Carbon Dioxide (CO2), and Particulate Matter (PM). J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 19, 100771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, H.; Riquelme, A.L.; Solar, V.A.; Azzolina-Jury, F.; Thibault-Starzyk, F. Removal of Chlorinated Volatile Organic Compounds onto Natural and Cu-Modified Zeolite: The Role of Chemical Surface Characteristics in the Adsorption Mechanism. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 258, 118080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

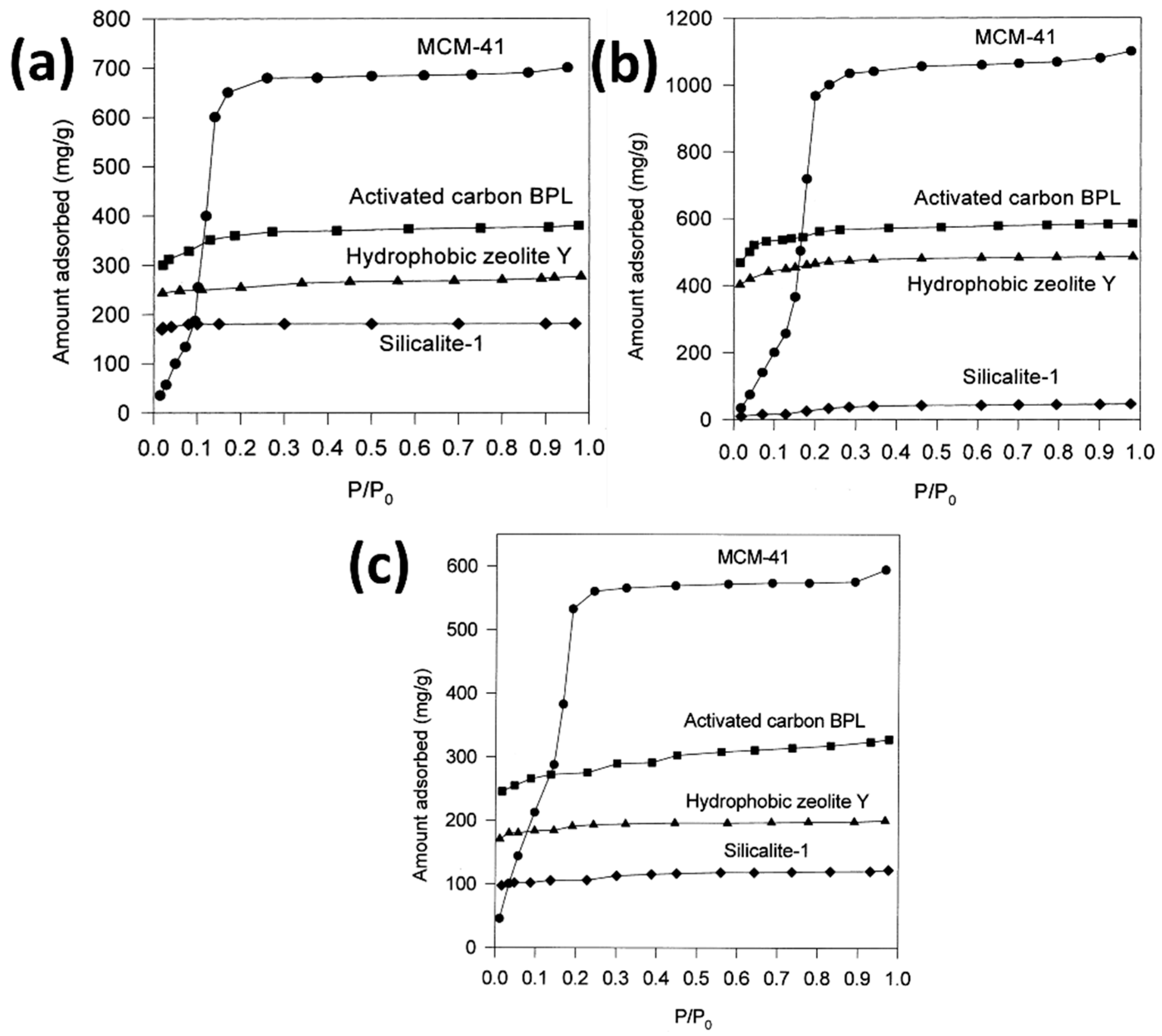

- Zhao, X.S.; Ma, Q.; Lu, G.Q. VOC Removal: Comparison of MCM-41 with Hydrophobic Zeolites and Activated Carbon. Energy Fuels 1998, 12, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.; Alphin, M.S. Low Temperature Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx by NH3 over Cu Modified V2O5/TiO2–Carbon Nanotube Catalyst. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2020, 129, 787–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.; Alphin, M.S.; Sivachandiran, L. Promotional Effects of Modified TiO2- and Carbon-Supported V2O5- and MnOx-Based Catalysts for the Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx: A Review. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 7795–7813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.S.; Srinivasan, S.A.; Alphin, M.S.; Mustafa, B.; Selvaraj, S.K. Progresses in the NOX Elimination Using Zeolite Under Low-Temperature Ammonia-Based Selective Catalytic Reduction—A Review. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 2024, 1827332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tao, H.; Yang, X.; Wu, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Yang, R.T.; Li, Z. Adsorptive Purification of NOx by HZSM-5 Zeolites: Effects of Si/Al Ratio, Temperature, Humidity, and Gas Composition. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2023, 348, 112331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Du, J.; He, H.; Han, S.; Lei, C.; Wang, S.; Fan, W.; Feng, Z.; et al. Importance of Controllable Al Sites in CHA Framework by Crystallization Pathways for NH3-SCR Reaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 277, 119193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

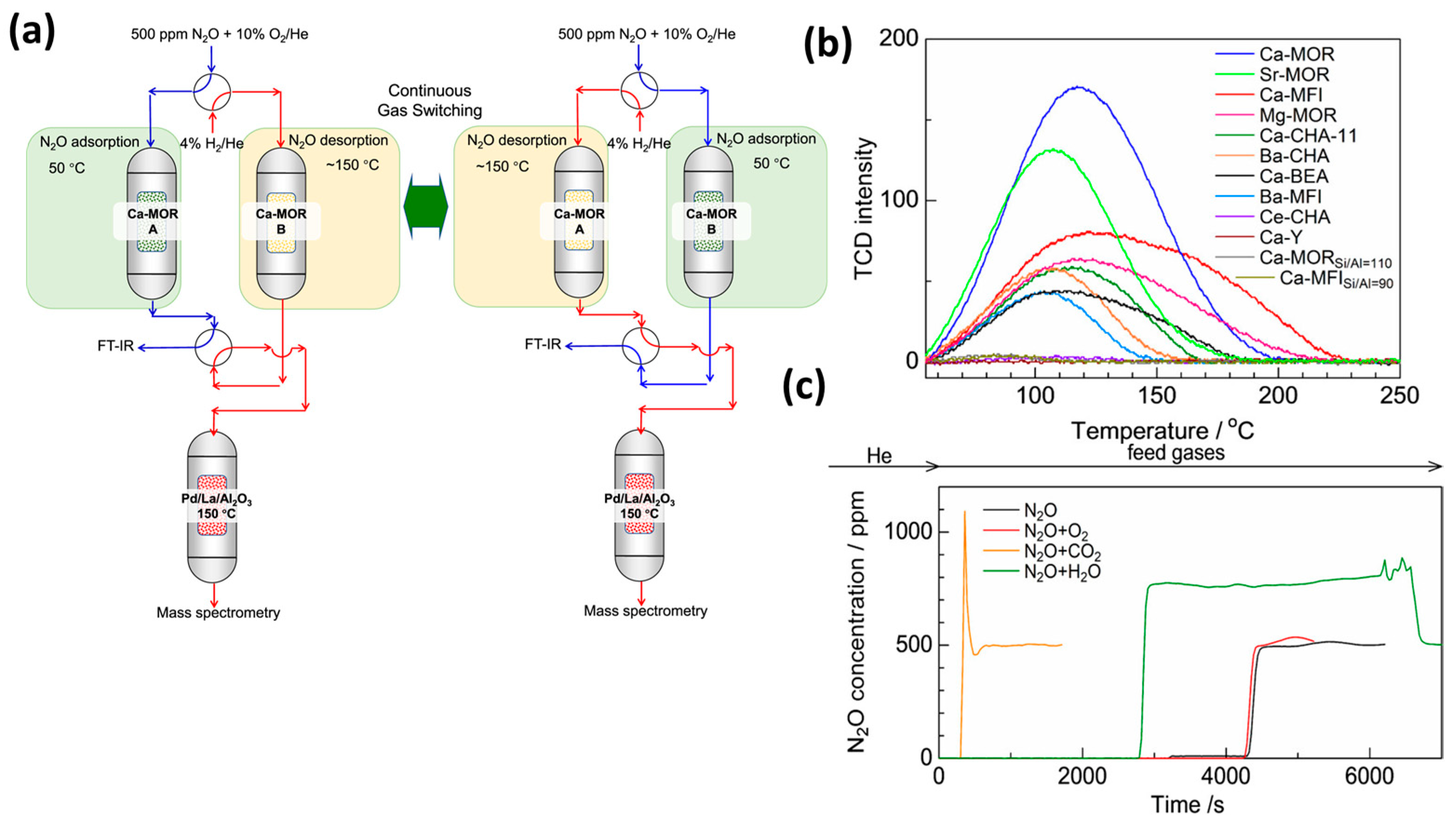

- Jing, Y.; He, C.; Wan, L.; Tong, J.; Zhang, J.; Mine, S.; Zhang, N.; Kageyama, Y.; Inomata, H.; Shimizu, K.; et al. Continuous N2O Capture and Reduction to N2 Using Ca-Zeolite Adsorbent and Pd/La/Al2O3 Reduction Catalyst. ACS EST Eng. 2025, 5, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khivantsev, K.; Jaegers, N.R.; Kovarik, L.; Hanson, J.C.; Tao, F.F.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Koleva, I.Z.; Aleksandrov, H.A.; Vayssilov, G.N.; et al. Achieving Atomic Dispersion of Highly Loaded Transition Metals in Small-Pore Zeolite SSZ-13: High-Capacity and High-Efficiency Low-Temperature CO and Passive NOx Adsorbers. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 16672–16677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.; Hwang, S.; Lee, H.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, D.H. Improving NOx Storage and CO Oxidation Abilities of Pd/SSZ-13 by Increasing Its Hydrophobicity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 277, 119190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahnaz, F.; Dharmalingam, B.C.; Mangalindan, J.R.; Vito, J.; Varghese, J.J.; Shetty, M. Metal Cation Exchange with Zeolitic Acid Sites Modulates Hydrocarbon Pool Propagation during CO2 Hydrogenation. Chem Catal. 2025, 5, 101183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Yang, X.; Tao, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Yang, R.T.; Li, Z. Enhancement of NOx Adsorption Performance on Zeolite via a Facile Modification Strategy. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 443, 130225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisi, L.; Pirone, R.; Russo, G.; Santamaria, N.; Stanzione, V. Nitrates and Nitrous Oxide Formation during the Interaction of Nitrogen Oxides with Cu-ZSM-5 at Low Temperature. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2012, 413–414, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdana, I.; Creaser, D.; Öhrman, O.; Hedlund, J. NOx Adsorption over a Wide Temperature Range on Na-ZSM-5 Films. J. Catal. 2005, 234, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, G.; Lisi, L.; Pirone, R.; Russo, G.; Tortorelli, M. Effect of Water on NO Adsorption over Cu-ZSM-5 Based Catalysts. Catal. Today 2012, 191, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sklyarov, A.V.; Keulks, G.W. TPD Study of the Interaction of Oxygen and NO with Reduced Cu/ZSM-5. Catal. Today 1997, 33, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Liu, Y. Dynamic Adsorption/Desorption of NOx on MFI Zeolites: Effects of Relative Humidity and Si/Al Ratio. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, M.; Shayanmehr, M.; Ghaemi, A. Exploring the Adsorption Desulfurization Efficiency Using RSM and ANN Methodologies. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garba, Z.N.; Zango, Z.U.; Adamu, H.; Haruna, A.; Menkiti, N.D.; Danmallam, U.N.; Ali, A.F.; Zango, M.U.; Ratanatamskul, C. A Review on Zeolites for Adsorptive Desulfurization of Crude Oil and Natural Gas: Kinetics, Isotherms, and Thermodynamics Studies. Prog. Eng. Sci. 2025, 2, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.X.; Valla, J.A. Adsorptive Desulfurization of Liquid Hydrocarbons Using Zeolite-Based Sorbents: A Comprehensive Review. React. Chem. Eng. 2019, 4, 1357–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.-L.; Lu, Y.-N.; Huang, H.; Yi, D.-Z.; Shi, L.; Meng, X. Adsorption Desulphurisation of Dimethyl Sulphide Using Nickel-Based Y Zeolites Pretreated by Hydrogen Reduction. Chem. Pap. 2016, 70, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaşyerli, S.; Ar, İ.; Doğu, G.; Doğu, T. Removal of Hydrogen Sulfide by Clinoptilolite in a Fixed Bed Adsorber. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2002, 41, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoguet, J.-C.; Karagiannakis, G.P.; Valla, J.A.; Agrafiotis, C.C.; Konstandopoulos, A.G. Gas and Liquid Phase Fuels Desulphurization for Hydrogen Production via Reforming Processes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 4953–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomadakis, M.M.; Heck, H.H.; Jubran, M.E.; Al-Harthi, K. Pressure-Swing Adsorption Separation of H2S from CO2 with Molecular Sieves 4A, 5A, and 13X. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasamy, C.; Wagner, J.P.; Spivey, S.; Weston, E. Removal of Sulfur Compounds from Natural Gas for Fuel Cell Applications Using a Sequential Bed System. Catal. Today 2012, 198, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micoli, L.; Bagnasco, G.; Turco, M. H2S Removal from Biogas for Fuelling MCFCs: New Adsorbing Materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2014, 39, 1783–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokogawa, Y.; Sakanishi, M.; Morikawa, N.; Nakamura, A.; Kishida, I.; Varma, H.K. VSC Adsorptive Properties in Ion Exchanged Zeolite Materials in Gaseous and Aqueous Medium. Procedia Eng. 2012, 36, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasper-Galvin, L.D.; Atimtay, A.T.; Gupta, R.P. Zeolite-Supported Metal Oxide Sorbents for Hot-Gas Desulfurization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1998, 37, 4157–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.; Tavana, A.; Sawada, J.A.; Wu, L.; Junaid, A.S.M.; Kuznicki, S.M. Novel Copper-Exchanged Titanosilicate Adsorbent for Low Temperature H2S Removal. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 12430–12434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chi, C.W. Zeolite Catalyst for Dilute Acid Gas Treatment via Claus Reaction. U.S. Patent 3,953,587, 27 April 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Xiao, J.; Chen, X.; Liang, X.; Fan, L.; Ye, D. Allowance and Allocation of Industrial Volatile Organic Compounds Emission in China for Year 2020 and 2030. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 69, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, E.; Odabasi, M.; Seyfioglu, R. Ambient Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Concentrations around a Petrochemical Complex and a Petroleum Refinery. Sci. Total Environ. 2003, 312, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrėnas, P.; Baltrėnaitė, E.; Šerevičienė, V.; Pereira, P. Atmospheric BTEX Concentrations in the Vicinity of the Crude Oil Refinery of the Baltic Region. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 182, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöschl, U.; Shiraiwa, M. Multiphase Chemistry at the Atmosphere–Biosphere Interface Influencing Climate and Public Health in the Anthropocene. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 4440–4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Zhao, T.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y. Ultramicroporous Carbon Molecular Sieve for Air Purification by Selective Adsorption Low-Concentration CO2 and VOC Molecules. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 7635–7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.-Y.; Cheng, W.-R.; Wu, T.-H.; Sheen, H.-J.; Wang, C.-C.; Lu, C.-J. A MEMS Μ-Preconcentrator Employing a Carbon Molecular Sieve Membrane for Highly Volatile Organic Compound Sampling. Chemosensors 2021, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain Bhuiyan, M.M.; Siddique, Z. Hydrogen as an Alternative Fuel: A Comprehensive Review of Challenges and Opportunities in Production, Storage, and Transportation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 102, 1026–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.T.; Sharma, P.; Bora, B.J.; Tran, V.D.; Truong, T.H.; Le, H.C.; Nguyen, P.Q.P. Fueling the Future: A Comprehensive Review of Hydrogen Energy Systems and Their Challenges. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 54, 791–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.R. Hydrogen Storage Methods: Review and Current Status. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnin, A.S.; Wacławiak, K.; Humayun, M.; Zhang, S.; Ullah, H. Hydrogen Storage Technology, and Its Challenges: A Review. Catalysts 2025, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Calvo, A.; Gutiérrez-Sevillano, J.J.; Matito-Martos, I.; Vlugt, T.J.H.; Calero, S. Identifying Zeolite Topologies for Storage and Release of Hydrogen. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 12485–12493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşğın, B.; Ryšavý, J.; Sangeetha, T.; Yan, W.M. Hydrogen Storage in Zeolites: A Mini Review of Structural and Chemical Influences on Adsorption Performance. Green Energy Fuel Res. 2025, 2, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnes Palomino, G.; Llop Carayol, M.R.; Otero Areán, C. Hydrogen Adsorption on Magnesium-Exchanged Zeolites. J. Mater. Chem. 2006, 16, 2884–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmi, H.W.; Book, D.; Walton, A.; Johnson, S.R.; Al-Mamouri, M.M.; Speight, J.D.; Edwards, P.P.; Harris, I.R.; Anderson, P.A. Hydrogen Storage in Ion-Exchanged Zeolites. J. Alloys Compd. 2005, 404–406, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, R.T. Hydrogen Storage in Low Silica Type X Zeolites. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 17175–17181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; He, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, B.; Tian, K.; Yang, K.; Wei, H.; Xu, X. Efficient Removal of Ammonia–Nitrogen in Wastewater by Zeolite Molecular Sieves Prepared from Coal Fly Ash. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sl No. | Zeolite | Pressure (kPa) | Mixture | Capacity (mmol/g) | Selectivity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Na-LTA-3 | 101.3 | CO2/N2 (15/85) | 3.71 | 730/ASF * | [64] |

| 2 | Li-ZK-5 | 100 | CO2/N2 (10/90) | 3.34 | 128/ISF * | [65] |

| 3 | K-ZK-5 | 100 | CO2/N2 (10/90) | 2.66 | 104/ISF | [65] |

| 4 | r1KCHA | 100 | CO2/N2 (15/85) | 1.74 | 496/ISF | [66] |

| 5 | r1KCHA | 100 | CO2/CH4 (50/50) | 1.95 | >100/ISF | [66] |

| 6 | Na-LTA-1 | 100 | CO2/CH4 (50/50) | 3.9 | 4.9/ISF | [67] |

| 7 | Li-RHO | 100 | CO2/CH4 (40/60) | 4.5 | >200/ISF | [68] |

| 8 | K-MER-3.8 | 100 | CO2/CH4 (50/50) | 3.4 | 68/ISF | [69] |

| 9 | SSZ-13 | 100 | CO2/H2 (50/50) | 3.9 | 25/ISF | [70] |

| 10 | SSZ-13 | 200 | CO2/H2 (50/50) | 3.2 | 11/ISF | [71] |

| 11 | C–S–H | 100 | CO2/H2 (50/50) | 1.2 | 25/ISF | [72] |

| 13 | Zeolite-5A@MOF-74 | 700 | CO2/CO/CH4/H2 (25:25:25:25) | 13.8 | 300/IAST * | [58] |

| 14 | NaX Zeolite | 100 | CO2/CO/He (20:20:60) | 1.13 | 14.5/ISF | [63] |

| 15 | MCM-41-40-TEPA | - | CO2/N2 (10/90) | 2.7 | - | [73] |

| 16 | M-1AP-60TETA | - | CO2/N2 (10/90) | 6.52 | - | [59] |

| Catalyst | Ag loading (mol g−1) | N2 (mol g−1) | K2 (kPa−1) | N1 (mol g−1) | K1 (kPa−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaAg-PZ2-25 | 6.21 × 10−4 | 2.8 × 10−4 | 643 | 1.8 × 10−3 | 0.3 |

| Ag-PZ2-25 | 9.45 × 10−4 | 5.7 × 10−4 | 925 | 1.6 × 10−3 | 0.8 |

| NaAg-PZ2-40 | 2.20× 10−4 | 1.6 × 10−4 | 103 | 1.9 × 10−3 | 0.06 |

| Ag-PZ2-40 | 3.74 × 10−4 | 2.6 × 10−4 | 181 | 1.8 × 10−3 | 0.06 |

| NaAg-PB | 1.78 × 10−4 | 1.2 × 10−4 | 19 | 1.7 × 10−3 | 0.02 |

| Ag-PB | 5.65 × 10−4 | 3.3 × 10−4 | 113 | 1.4 × 10−3 | 0.04 |

| AgX | 31.5 × 10−4 | 4.8 × 10−4 | 26 | 2.2 ×10−3 | 0.05 |

| Sl No. | Zeolite | Gas Mixture * | Adsorption Capacity (mmol/g) * | Pressure (bar) * | Selectivity * | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ZMS-11 | Kr/N2 (50:50) | 0.51 (Kr) | 1.0 | 4.5/IAST | [77] |

| 2 | SSZ-13 | Kr/N2 (50:50) | 0.50 (Kr) | 1.0 | 3.9/IAST | [77] |

| 3 | 5A | Kr/N2 (50:50) | 0.60 (Kr) | 1.0 | 0.7/IAST | [77] |

| 4 | 4A | Kr/N2 (50:50) | 0.18 (Kr) | 1.0 | 0.7/IAST | [77] |

| 5 | 13X | Kr/N2 (50:50) | 0.42 (Kr) | 1.0 | 0.9/IAST | [77] |

| 6 | Na-CHA-11.5 | Ke/Xe (20:80) | 1.98 (Xe) | 1.0 | 6/IAST | [78] |

| 7 | Na-MFI-13.1 | Ke/Xe (20:80) | 2.0 (Xe) | 0.2 | 4.7/IAST | [78] |

| 8 | Na-FAU-1.2 | Ke/Xe (20:80) | 2.4 (Xe) | 0.2 | 4.9/IAST | [78] |

| 9 | Na-BEA-13.4 | Ke/Xe (20:80) | 2.1 (Xe) | 0.2 | 7.2/IAST | [78] |

| 10 | ZIF-4 | Ke/Xe (20:80) | 1.64 (Xe) | 0.2 | 16.2/IAST | [79] |

| Sl No. | Light Hydrocarbons | Kinetic Diameter (Å) | Polarizability ×1025 cm−3 | Boiling Point (K) | Dipole Moment (×1018/ESU cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | C2H4 | 4.16 | 42.5 | 169.4 | 0 |

| 2 | C2H6 | 4.44 | 44.3 | 184.6 | 0 |

| 3 | CH4 | - | 25.9 | 111.6 | 0 |

| 4 | C3H8 | 4.3–5.11 | 62.9 | 231.0 | 0.084 |

| 5 | C3H6 | 4.68 | 62.9 | 225.5 | 0.366 |

| Uses of Gases | Harmful Impact of Gases |

|---|---|

| CO2 is the main component in fire extinguishers | CO2 is the main source for global warming resulting in acid rain, temperature rise |

| Nitrogen is used for the synthesis of ammonia and food packaging. | Nitrogen can cause severe frostbite and asphyxiation due to oxygen displacement. Oxidized form of nitrogen -N2O and NO2 pose significant health risks, causing respiratory issues |

| Argon is used in light bulbs | Argon acts as a simple asphyxiant by causing dizziness, unconsciousness, and death in low-oxygen situations |

| Xenon is used in nuclear reactors | Xenon inhalation in excessive concentrations results in dizziness, nausea, loss of consciousness. Oxygen–xenon compounds are toxic. They are also explosive, breaking down to elemental xenon and diatomic oxygen with much stronger chemical bonds than the xenon compounds. |

| Methane is the main component of natural gas used for heating, cooking, and electricity generation, powering homes, CNG, and industries. | CH4 is a powerful greenhouse gas and is a key ingredient in forming harmful air pollutant, tropospheric ozone. |

| CO is used industrially as a fuel and a reducing agent for metal extraction. | CO binds to red blood cells in hemoglobin, resulting in reduced oxygen levels in human body. |

| Sl No. | Zeolite | Surface Area (m2/g) * | Catalyst Weight in the Pack Fixed-bed (g) * | Reaction Condition | NOx Adsorption Capacity (mmol/g) * | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | H-ZSM-53 | 336 | 2.5 | 200 ppm NO + 4.5% CO2/N2 + 14% O2 298 K | 0.232 | [110] |

| 2. | Cu-ZSM-5 | 350 | 1 | 800 ppm NO/He at 298 K | 0.25 | [111] |

| 3. | Na-ZSM-5 | 415 | - | 600 ppm NO2/Ar at 303 K | 0.42 | [112] |

| 4. | Cu-ZSM-5 | 250 | - | 800 ppm NO + 1% O2 + 2% H2O/He at 323 K | 0.09 | [113] |

| 5. | Cu-ZSM-5 | 360 | 3 | Wet gas stream (RH = 0.32%): 500 ppm NO + 500 ppm NO2 + 10% O2 /N2 at 473 K | 0.084 | [104] |

| 6. | Na-ZSM-5 | - | 0.5 | 1000 ppm NO at 273 K | 0.01 | [114] |

| 7. | HZSM-5 (35) | 336.5 | 2.25 | 200 ppm NOx, 14% O2, 4.5% CO2, Bal N2 | 0.28 | [115] |

| 8. | HZSM-5 (110) | 372.4 | 2.25 | 200 ppm NOx, 14% O2, 4.5% CO2, Bal N2 | 0.19 | [115] |

| 9. | HZSM-5 (360) | 385.1 | 2.25 | 200 ppm NOx, 14% O2, 4.5% CO2, Bal N2 | 0.08 | [115] |

| 10. | Silicate-1 | 413.8 | 2.25 | 200 ppm NOx, 14% O2, 4.5% CO2, Bal N2 | 0.005 | [115] |

| Sl No. | Zeolites | Selectivity * | Modification Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Clinoptilolite | 0.03g S/g | - | [120] |

| 2. | H-Y | 59% S reduction | - | [121] |

| 3. | Ce-Na-Y-2 | 39% S reduction | Ion exchange | [121] |

| 4. | 13X | 85% | - | [122] |

| 5. | Ca-X and Na-X | 10 wt.%S | Ion exchange | [123] |

| 6. | 5A | 66.6% | - | [124] |

| 7. | LTA (Zeolite A) | 20% | Ion exchange | [125] |

| 8. | Mn-SP-115 | 0.47% wt | Wet impregnation | [126] |

| 9. | Cu-ETS-2 | 47 mg H2S/g of adsorbent | Ion exchange | [127] |

| 10. | Na-Mordenite | 97% | Ion exchange | [128] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Meenu, P.C.; Meena, B.; Smirniotis, P.G. A Review on the Applications of Various Zeolites and Molecular Sieve Catalysts for Different Gas Phase Reactions: Present Trends in Research and Future Directions. Processes 2026, 14, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010132

Meenu PC, Meena B, Smirniotis PG. A Review on the Applications of Various Zeolites and Molecular Sieve Catalysts for Different Gas Phase Reactions: Present Trends in Research and Future Directions. Processes. 2026; 14(1):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010132

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeenu, Preetha Chandrasekharan, Bhagatram Meena, and Panagiotis G. Smirniotis. 2026. "A Review on the Applications of Various Zeolites and Molecular Sieve Catalysts for Different Gas Phase Reactions: Present Trends in Research and Future Directions" Processes 14, no. 1: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010132

APA StyleMeenu, P. C., Meena, B., & Smirniotis, P. G. (2026). A Review on the Applications of Various Zeolites and Molecular Sieve Catalysts for Different Gas Phase Reactions: Present Trends in Research and Future Directions. Processes, 14(1), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010132