Abstract

The Zhu I Depression in the Pearl River Estuary Basin is a major oil and gas enrichment area, with complex lithology, mainly mudstone, fine sandstone and siltstone, strong heterogeneity, and extensive development of abnormal high pressure, making it difficult to predict formation pressure. The effective stress coefficient (ESC) is an important parameter in formation pressure prediction and formation stress estimation, which is usually obtained by experiments and by the empirical function formulas of ESC and porosity. However, the calculation accuracy of these empirical formulas is often affected by lithology and critical porosity, and their application in the whole area or multi-lithology formations is limited. In addition, shear wave velocity data are limited by cost and technical conditions in practical logging applications. Therefore, based on the Gassmann equation and the approximation of P-wave modulus and volume modulus, this study realizes a multi-lithology ESC estimation method using P-wave velocity, density, and porosity, and applies it to the logging of the study block. The dynamic ESC along the wellbore direction is obtained and the logging dynamic ESC estimation model is corrected to verify the reliability of the method. The results show that the logging-derived ESC is mainly distributed in the range of 0.3~0.8, while the average ESC measured in the laboratory is between 0.5 and 0.6. The ESC of the sandstone layers with high porosity is relatively large and that of the mudstone layers with low porosity is small. In the absence of shear wave velocity, this method can effectively estimate the ESC and further predict formation pressure, which plays an important role in oil exploration and development.

1. Introduction

Rocks, as complex porous medium, exhibit deformation and failure behaviors that depend not only on confining pressure but also on pore pressure—two critical stress components that collectively govern their mechanical response. Terzaghi (1923) concluded that the deformation and failure of soil mechanics are controlled by the difference between confining pressure and pore pressure and called the differential stress “effective stress” and established the “effective stress law” [1]. Biot (1941) established the theory of pore elasticity based on the three-dimensional consolidation problem of soil [2]. Later, Biot (1956) found that low-permeability porous media such as rocks were not suitable for applying Terzaghi’s effective stress principle and proposed a modified effective stress principle, thus introducing the definition of effective stress coefficient

(α) [3]:

In the equations, is the surrounding rock pressure, is the pore fluid pressure, and is the effective stress. is the volume modulus of porous dry rock, and is the volume modulus of rock matrix, α is the effective stress coefficient (ESC), also known as the pore elasticity coefficient. In Terzaghi’s law of effective stress, the effective stress coefficient is equal to one, while in non-uniform media, the effective stress changes depending on the characteristics of the rock, including the volume, porosity, water saturation, fluid properties, volume occupied by the skeleton, conductivity, and permeability [4,5]. Therefore, the ESC in non-uniform medium is often not one. To obtain the accurate ESC of rocks, scholars have carried out a large number of theoretical derivations and experimental studies [3,4,5,6]. Gurevich (2004) theoretically deduces that the ESC is one when the rock is composed of a single mineral and the fluid in the pores is not affected by pressure, and he also pointed out that this conclusion does not apply to heterogeneous rocks [7]. Many scholars [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] have also calculated the value of the ESC through petrophysical experiments and the results show two situations; namely, the ESC is approximately equal to 1 [16] and the ESC is less than 1 [8,9,10,11,12]. It is pointed out that there are two extreme cases of ESC: one is when Φ = 0, Kdry = Kma,

α = 0, which represents well-consolidated dense sedimentary rock; the other is when the porosity is greater than the critical porosity (Φ ≥ Φcrit), Kdry = 0,

α = 1, which represents unconsolidated sediment such as soil. The range of the pore elasticity coefficient is 0 ≤ α ≤ 1. It can be seen that when the porosity of the experimental sample is high, the value of the ESC is close to 1, while when the physical properties of the experimental sample deteriorate, the ESC will be much lower than 1 [17,18].

The Zhu I Depression in the Pearl River Estuary Basin of China is a main oil and gas enrichment area, and its Wenchang Formation is one of the main reservoirs. The formation is mainly composed of a large set of mudstone, interspersed with fine sandstone and siltstone of varying thicknesses, with strong heterogeneity and extensive development of abnormal high pressure. Formation pressure is difficult to predict, which affects drilling safety. The ESC is an important parameter in formation pressure prediction and formation stress estimation. It can reflect the porosity, compaction degree, and fluid occurrence status of underground rock strata, which is also crucial for finding effective reservoirs. At present, the ESC is often simplified to one when calculating formation pressure, which is not applicable to dense sedimentary rock formations. For a long time in the past, the estimation of ESC has been limited to laboratory measurements. The ESC is regarded as a function of porosity and a large number of empirical formulas have been proposed. Scholars have also summarized some ESC estimation methods [12,13,14,15,16,19]. The most common estimation method is to regard the ESC as a function of porosity and a large number of empirical formulas have been proposed. These formulas for calculating the ESC are usually only applicable to specific favorable formations in certain areas, such as sandstone formations [13,14]. Some ESC calculation formulas are based on laboratory measurements and critical porosity, but they have large errors in most lithological strata and are affected by lithology and regional factors [12,13,14,15,16,19]. Wang et al. (2016) [20] developed an ESC estimation method and proposed a new method for estimating the ESC. This method does not need to introduce critical porosity, can eliminate the influence of lithology on estimation accuracy, but requires shear wave velocity to participate in the calculation, and is suitable for ESC estimation in multiple regions and lithologies. The purpose and reason for selecting specific well depths in this study are closely related to the distribution characteristics of oil and gas reservoirs and the completeness of logging data in the study area. The selected wells H6 and L1 are located in the Zhu I Depression and Zhu II Depression of the Pearl River Estuary Basin, respectively, which are the key oil and gas exploration areas in the region. The depth range involved (about 4444–4887 m) covers the main reservoir sections of the Wenchang Formation, where abnormal high pressure is developed and ESC research is of great practical significance. In addition, the logging data and core samples in these depth ranges are complete, which can provide sufficient data support for the verification of the calculation method.

In practical oil and gas exploration, logging methods (including resistivity logging) can indeed predict formation information before drilling—though this relies on pre-drilling logging techniques such as logging while drilling (LWD) or nearby well logging data. For instance, pre-drilling resistivity logging can predict the target formation’s lithology (e.g., high resistivity indicating sandstone reservoirs), porosity (low resistivity correlating with high-porosity zones), and fluid properties (high resistivity suggesting oil/gas layers) by analyzing adjacent well data, laying a preliminary geological framework; acoustic logging from adjacent wells can forecast formation compaction degree, while density-neutron combined logging can estimate pore structure [21]. However, pre-drilling logging data typically come from adjacent wells, so their accuracy declines as the distance from the target well increases. Regarding logging methods for predicting the effective stress coefficient are as follows: currently, there is no direct logging technique specifically designed for ESC prediction. Most existing approaches rely on indirect calculations—either by establishing empirical relationships between ESC and porosity (using porosity logging data) or by computing via elastic parameters (combining acoustic, density logging data with shear wave velocity). However, the former is constrained by lithology and the latter requires shear wave velocity (often unavailable due to cost limits)—this is precisely the technical gap this study addresses, as it establishes an ESC estimation method using only P-wave velocity, density, and porosity.

Against this backdrop, the selection of well depths in this study (4444–4887 m in wells H6 and L1) is deliberately targeted to address these gaps. These wells are located in the Zhu I and Zhu II Depressions—key exploration zones of the Pearl River Estuary Basin—and their depth range covers the main Wenchang Formation reservoir section, where abnormal high pressure is prevalent and ESC accuracy is most impactful for drilling safety. Equally important, the logging data and core samples from these depths are complete, providing the necessary basis to validate any new ESC estimation method.

To resolve the limitations of existing approaches, this study proposes a novel ESC estimation method that exclusively uses three readily available logging parameters: P-wave velocity, bulk density, and porosity. By eliminating the dependency on shear wave velocity and enhancing compatibility with multi-lithology formations, this method fills a longstanding technical void in petrophysical analysis for formation pressure prediction. Its practical value is twofold: first, it provides a reliable solution for formation pressure evaluation in areas lacking shear wave velocity data—overcoming a historical barrier to accurate pressure prediction; second, by enabling more precise pre-drilling formation pressure characterization, it supports optimized drilling design, reducing risks of wellbore instability (e.g., collapse, lost circulation) and non-productive time from unforeseen pressure anomalies [22]. For complex geological settings like the Pearl River Estuary Basin, this translates to tangible improvements in the safety, efficiency, and economic viability of oil and gas drilling operations.

2. Estimation of Dynamic Effective Stress Coefficient

2.1. Formula for Estimating Dynamic Effective Stress Coefficient

In this study, the goal of estimating the effective stress coefficient using only P-wave velocity data is achieved by establishing the equivalent relationship between P-wave modulus and volume modulus, based on the Gassmann equation [23]. Pickett (1963) [24] found through a large number of experimental studies that the Poisson’s ratio of dry rocks is often approximately equal to that of minerals [19]. According to the results of Mavko et al. (1998) [25,26], it was found that the ratio of the volume modulus of dry rock to the volume modulus of rock matrix is consistent with the ratio of the shear modulus of dry rock and the shear modulus of rock matrix [24]:

where and represent the volume modulus of rock matrix and dry rock, respectively; and represent the shear modulus of dry rock and rock matrix, respectively. Based on the theory of propagation of elastic waves in solid media, the P-wave modulus of dry rock and the P-wave modulus of rock matrix can be expressed as follows:

where represents the bulk density of dry rock; represents the bulk density of rock matrix; represents the P-wave velocity of the rock matrix; represents the P-wave velocity of dry rock.

Formula (6) indicates that the ratio of the P-wave modulus of dry rock to that of matrix rock is equal to the ratio of their volume moduli.

Furthermore, the approximate expression of the P-wave modulus, proposed by Mavko et al. (1995) [26] and based on the Gassmann equation [23], is introduced:

where is the P-wave modulus of saturated rock; is the P-wave modulus of pore fluid; Φ is the porosity of the rock. To simplify the derivation process, two intermediate variables are defined:

Substitute the above expressions into Formula (2) of the ESC:

If the reservoir section is a gas-bearing section, Formula (9) can be further simplified to:

In practical application, can be obtained from logging wave velocity and density, and porosity can be obtained from logging results. The fluid density and velocity involved in the P-wave modulus of the pore fluid , can be estimated using the method provided by Batzle–Wang (1992) [27].

The rock matrix density involved in the matrix P-wave modulus can be obtained from the relationship between density and porosity, and the rock matrix velocity can be estimated using the Wyllie time-average equation [22]:

2.2. Fluid Saturation Estimation and Method Robustness Verification

2.2.1. Fluid Saturation Estimation Method

This study adds a section to elaborate on the fluid saturation estimation method for the logging interval. The fluid saturation in the study area is estimated using the Archie formula [13], with the following assumptions: the formation rock is homogeneous and isotropic; the pore space is fully occupied by oil, gas, and water, without other fluids; the influence of clay minerals on resistivity is ignored. The specific model is as follows:

where is the water saturation, is the tortuosity coefficient (taken as 1.0 in this study), is the saturation exponent (taken as 2.0), is the cementation exponent (taken as 2.0), is the formation water resistivity, is the porosity, and is the true formation resistivity.

For the formation intervals that may contain gas, this study calculates the ESC under both “fully brine-saturated” and “partially gas-saturated” states, respectively. Under the fully brine-saturated state, the fluid properties are consistent with the formation water parameters; under the partially gas-saturated state, the fluid is a mixture of brine and natural gas, and the P-wave modulus of the mixed fluid is calculated using the weighted average method based on saturation [28]. The analysis of the impact of the two states on pressure prediction shows that the ESC under the partially gas-saturated state is 0.05–0.1 higher than that under the fully brine-saturated state. This difference leads to a 5–10% reduction in the predicted formation pressure. The main reason is that the gas has lower elasticity than the brine, which enhances the contribution of fluid pressure to effective stress.

2.2.2. Method Robustness Verification

Aiming at the problem of complex mineral composition of the test samples, this study further demonstrates the rationality of using the “simple mixing law to estimate matrix velocity” [26]. The main minerals of the samples include quartz, feldspar, calcite, and siderite. The simple mixing law can comprehensively reflect the overall elastic characteristics of the matrix by weighting the velocities of various minerals according to their content. Compared with other complex models, it has the advantages of simple calculation and clear physical meaning, which is suitable for the mineral composition characteristics of the study area.

To verify the robustness of the method, Table 1 shows the changes in ESC when the matrix velocity changes by 10% and the matrix density changes by 2%. The results show that when the matrix velocity increases by 10%, the ESC decreases by 3–5% on average; when the matrix velocity decreases by 10%, the ESC increases by 4–6% on average. When the matrix density increases by 2%, the ESC decreases by 1–2% on average; when the matrix density decreases by 2%, the ESC increases by 1–3% on average. The above changes are within a reasonable range, indicating that the proposed method has good robustness to the changes in matrix parameters.

Table 1.

Changes in effective stress coefficient under matrix parameter fluctuations.

2.3. Matrix Parameters Estimation

The accurate determination of matrix properties, specifically the P-wave velocity () and density (), is critical for a reliable estimation of the effective stress coefficient. Given the complex and variable mineralogy of the studied formations, as evidenced by the XRD results in Table 1, the use of a single-valued matrix velocity (e.g., from the Wyllie time-average equation [22]) or a simple two-mineral model is inadequate. To address this, a more robust approach based on the Voigt–Reuss–Hill (VRH) averaging scheme was employed to compute the effective matrix moduli [24].

The VRH average provides an estimate of the effective elastic moduli of a multi-mineral composite by calculating the arithmetic mean of the Voigt (upper) and Reuss (lower) bounds. For the bulk modulus () and shear modulus (), it is given by:

where , , and are the volume fraction, bulk modulus, and shear modulus of the i-th mineral component, respectively. The matrix density () was computed as a simple volumetric average . The mineralogical composition for each depth interval was guided by XRD data from nearby core samples (Table 1), and standard elastic moduli and densities for constituent minerals were taken from established sources [24].

The matrix P-wave velocity was then derived from the resulting effective moduli and density . A comparison between the VRH-predicted and measured values from core samples showed a significantly improved agreement, with errors generally within 3%, compared to the ~8% error observed when using a constant quartz-based matrix velocity. This mineralogy-consistent approach enhances the physical basis of the input parameters and reduces the systematic bias in the subsequent calculation of the effective stress coefficient, thereby increasing the overall robustness of the method across the poly-lithological sequences encountered in the study area.

2.4. Dynamic Effective Stress Coefficient Estimation Results (Logging)

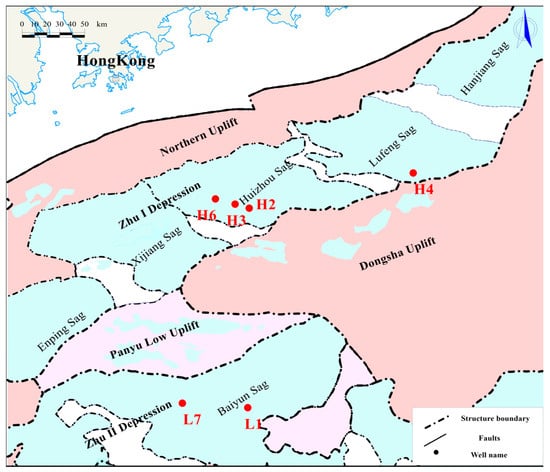

The Pearl River Estuary Basin is located on the northern continental edge of the South China Sea. It is a typical passive continental margin rift basin formed under the control of the South China Sea expansion since the Cenozoic, extending in a northeast direction. It can be divided into two tectonic units: the Zhu I Depression (shallow water area) and the Zhu II Depression (deep water area) (Figure 1). The red dots in the figure represent the well locations, among which wells H2, upper H3, H4, and H6 are located in the Zhu I Depression, and wells L1 and L7 are located in the Zhu II Depression. Oil and gas exploration has confirmed that the Wenchang Formation in the Zhu I Depression and the Zhuhai Formation and Wenchang Formation in the Zhu II Depression are the main oil and gas reservoirs [29]. These formations are mainly composed of large sets of mudstone, interspersed with fine sandstone and siltstone of varying thicknesses, with strong heterogeneity and extensive development of abnormal high pressure. The highest pressure coefficient of the drilled formations exceeds 1.60. The results show that hydrocarbon generation is the main cause of overpressure formation in this area [30]. The overpressure layer system is buried at a depth of more than 3500 m. The formations are generally dense, with a porosity of 10–30% and a permeability of 0.001–4 md.

Figure 1.

Structural location map of the study area.

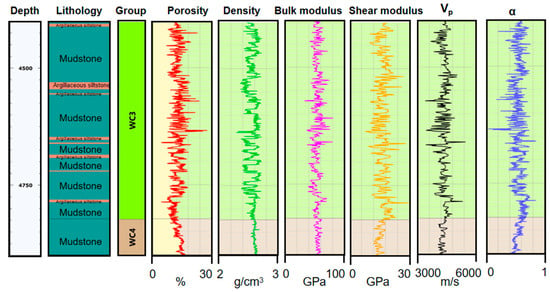

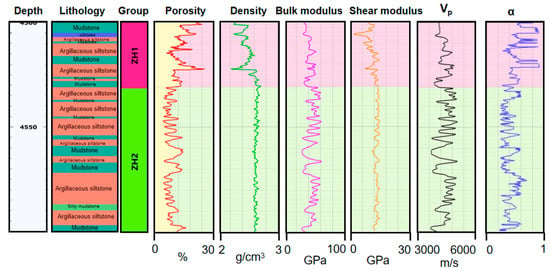

Based on the logging data and the dynamic ESC dynamic effective in Section 2.1, this study studies the dynamic ESC of well H6 in the Zhu I Depression and well L1 in the Zhu II Depression. Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the evolution curves of porosity, density, P-wave velocity, and dynamic ESC with depth in wells H6 and L1, respectively. The depth of the reservoir section is more than 4000 m. The lithology of the reservoir section of Well L1 is mainly argillaceous siltstone, containing a small amount of mudstone, etc. Its porosity is higher in the upper section and less than 10% in the lower section. The ESCs of the two wells are obtained using the dynamic ESC estimation method. The distribution range of the ESCs is between 0.3 and 0.8. It can be seen that simplifying the ESC to one is likely to cause errors in formation pressure prediction [31].

Figure 2.

Evolution curves of porosity, density, P-wave velocity, and dynamic effective stress coefficient with depth in well H6.

Figure 3.

Evolution curves of porosity, density, P-wave velocity, and dynamic effective stress coefficient with depth in well L1.

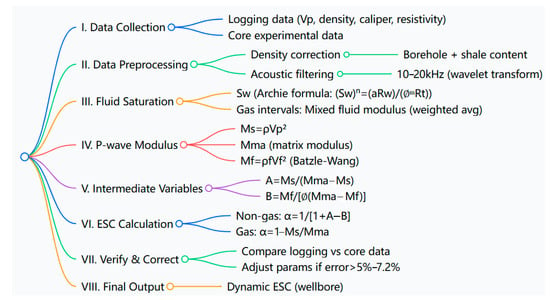

2.5. Logging Data Processing Process

To ensure the reproducibility of the proposed method and provide clear operational guidelines for practical application, this section details the logging data processing procedures, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Mind map of calculation of the ESC.

- Porosity logging method: The neutron porosity logging and density logging combination method is adopted [32]. Neutron porosity logging measures the porosity by the content of hydrogen nuclei in the formation, and density logging calculates the porosity based on the difference between the formation density and the matrix density. The final porosity value is obtained by weighted averaging the two logging results.

- Density logging data correction: First, the borehole enlargement correction is performed. According to the caliper logging data, the correction coefficient is determined; then, the shale content correction is carried out. The correction formula:

- where is the corrected density, is the logging density, is the shale content, and is the shale density.

- Acoustic data filtering method: The wavelet transform filtering method is used to filter the acoustic logging data [33]. The main frequency range of the effective signal is determined to be 10–20 kHz, and the noise signals outside this frequency range are filtered out to improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the data.

The calculation process of the dynamic ESC is presented in the form of a step-by-step list for the convenience of readers to reproduce the research results:

- 1.

- Collect logging data (P-wave velocity, density, caliper, resistivity, etc.) and core experimental data of the study area.

- 2.

- Correct the density logging data and filter the acoustic data according to the above logging data processing process.

- 3.

- Estimate the fluid saturation of the logging interval using the Archie formula.

- 4.

- Calculate the P-wave modulus of saturated rock (), rock matrix (), and pore fluid () based on Formulas (4) and (5), and the definition of P-wave modulus.

- 5.

- Calculate the intermediate variables A and B according to Formula (8).

- 6.

- Calculate the ESC using Formula (9) (for gas-bearing intervals, use Formula (10)).

- 7.

- Verify the calculation results with core experimental data and correct the model if necessary.

3. Experimental Study of Dynamic Effective Stress Coefficient

3.1. Experimental Principle

Todd and Simmons (1972) proposed a formula for calculating the dynamic ESC using the P-wave velocity results obtained from petrophysical experiments under different confining pressure and pore pressure conditions in the laboratory [9]:

where is the P-wave velocity the unit is km/s; is the pore pressure, the unit is MPa; is the differential stress, which is equal to the confining pressure minus the pore pressure, the unit is MPa; is the slope of the P-wave velocity with the change in pore pressure under constant differential stress; since and , the partial derivative of on both sides is obtained:

Therefore, is the slope of the P-wave velocity curve with the change in differential stress when the formation pore pressure is zero. Both and are obtained from petrophysical experimental data.

3.2. Experimental Samples and Experimental Methods

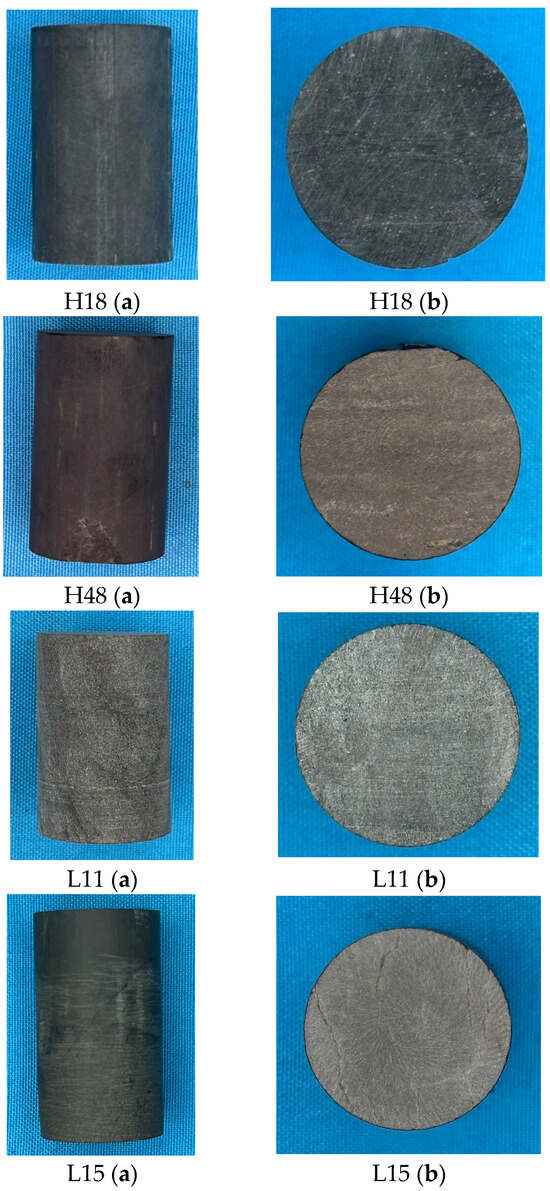

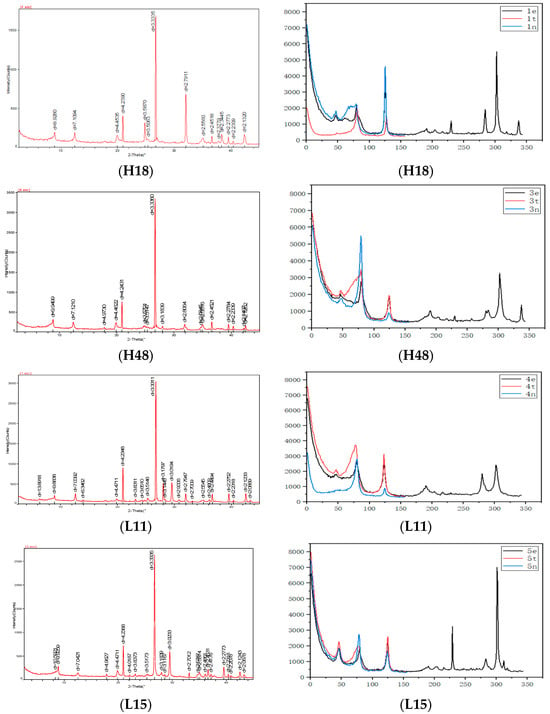

To verify the estimation results of the dynamic ESC in Section 2.3, a petrophysical experiment on the dynamic ESC was carried out in the laboratory. The samples in Figure 5 were taken from well H6 at depths of 4444.02 m (sample H18) and 4887.05 m (sample H48), and from well L1 at depths of 4524.1 m (sample L11) and 4561.7 m (sample L15). According to the rock mechanics experimental standards, the samples were made into cylindrical samples with a length of 50 mm and a diameter of 25 mm, and the parallelism error of the two ends was 0.02 mm. Before the dynamic ESC experiment, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was also carried out on the experimental samples. The XRD pattern is shown in Figure 6 and the mineral composition of the samples was obtained, which are mainly composed of quartz, feldspar, calcite, siderite, etc. The porosity of the samples was obtained by the helium porosity method [34], and their basic physical parameters are shown in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Experimental sample photos: (a) Cylindrical sample; (b) Sample end face.

Figure 6.

XRD pattern of whole-rock non-clay minerals and clay minerals.

Table 2.

Results of whole-rock mineral X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis.

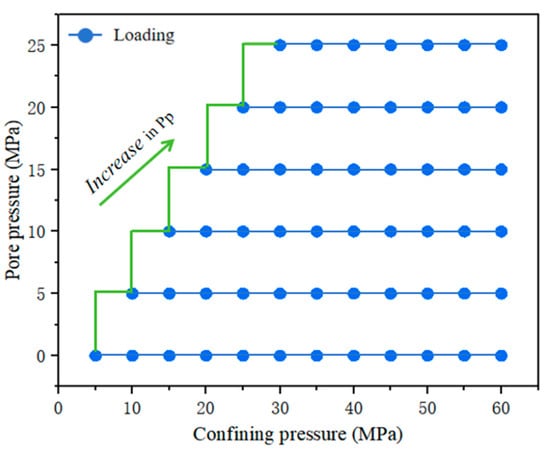

The petrophysical experiment of the dynamic ESC mainly measures the wave velocity of the samples under different confining pressure and pore pressure conditions. The experimental system mainly includes a cyclic loading variable confining pressure-hole pressure acoustic wave test system [35]. Figure 7 shows the loading diagram. For each sample, six sets of pore pressures (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 MPa) were set, and the confining pressure was loaded from 5 MPa to 60 MPa higher than the pore pressure. Taking the pore pressure of 0 MPa as an example, the confining pressure was loaded from 5 MPa to 60 MPa, and the P-wave velocity was measured every 5 MPa. Then, the confining pressure was directly unloaded to 10 MPa, the pore pressure was increased to the next value (i.e., 5MPa), and after the pore pressure was stabilized, the confining pressure was continuously increased to 60 MPa, and the P-wave velocity was measured every 5 MPa.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of confining pore pressure loading.

3.3. Experimental Results

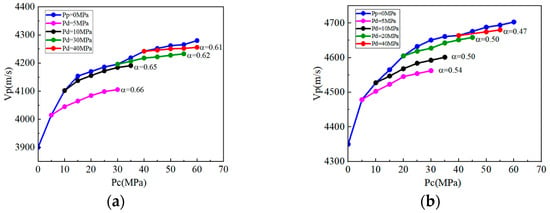

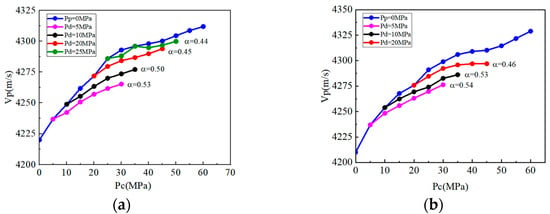

As illustrated in Figure 8 (for samples H18 at 4444.02 m and H48 at 4887.05 m from well H6) and Figure 9 (for samples L11 at 4524.1 m and L15 at 4561.7 m from well L1), when pore pressure is zero (blue curve), the initial stage of confining pressure loading is dominated by the micro-fracture closure process—a mechanism triggered when the normal stress on fracture surfaces exceeds a “closure threshold stress”. This threshold is jointly determined by the fracture’s initial aperture (0.1–0.5 μm for the study samples) and rock matrix mechanical strength: clay-rich samples like H18 (28.7% clay content) exhibit a lower threshold (≈5 MPa) due to weaker matrix strength, while quartz-dominated samples like H48 (63.6% quartz) require higher confining pressure (≈10 MPa) to initiate closure [36].

Figure 8.

P-wave velocity of well H6 sample with confining pressure and pore pressure: (a) H18 (4444.02 m); (b) H48 (4887.05 m).

Figure 9.

P-wave velocity of well L1 sample with confining pressure-pore pressure: (a) L11 (4524.1 m); (b) L15 (4561.7 m).

Once triggered, micro-fractures undergo a stepwise, irreversible closure: first, rough protrusions on fracture surfaces are crushed under stress; then, the fracture aperture gradually decreases until entering a “tight contact” state (aperture < 0.05 μm). This irreversibility is reflected in the P-wave velocity curve—even when confining pressure is unloaded to the initial value, the post-unloading velocity is 8–12% higher than the pre-loading velocity under the same confining pressure. During this closure phase, wave velocity increases significantly with confining pressure, with the amplitude of this increase governed by multiple factors: lithology (clay-rich samples close faster), initial porosity (higher-porosity samples like H18 with 17.6% porosity show a ≈250 m/s velocity increase, while low-porosity samples like L11 with 10.6% porosity only increase by ≈120 m/s), and pore pressure (increasing pore pressure delays closure by reducing effective stress on fracture surfaces, e.g., H18’s closure threshold rises to 15 MPa at 25 MPa pore pressure).

In the later stage of loading, as micro-fracture closure tends to complete, the remaining pores are mainly intergranular pores of rigid minerals, making them less sensitive to confining pressure changes and thus slowing the wave velocity growth rate. Even under constant differential stress (Pd = Pc − Pp), wave velocity still increases with confining pressure, indicating the effective stress coefficient (ESC) is not one. Notably, a larger wave velocity change amplitude corresponds to a greater ESC, while ESC decreases with increasing differential stress. Calculated via Equation (13), the ESCs under different differential stresses show no significant overall difference.

Table 3 summarizes the experimental data of the effective stress coefficient, with a total of four sample groups (H18, H48, L11, L15) counted, and the depth coverage ranges approximately from 4444.02 m to 4887.05 m. The results show that there are differences in the effective stress coefficient among different samples: the average value of H18 is 0.64, which is the highest among the four groups; the average value of L11 is 0.48, which is relatively low, reflecting the influence of reservoir parameter heterogeneity on the effective stress coefficient.

Table 3.

Summary of the test result of the effective stress coefficient.

4. Discussion

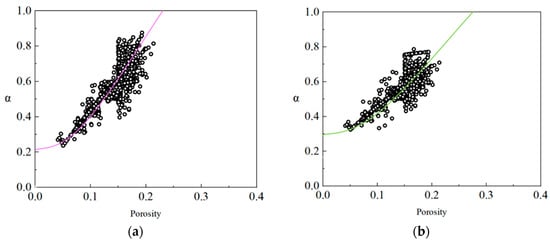

4.1. Analysis of -Porosity Cross Plots

In addition to the evolutionary characteristics of porosity, density, P-wave velocity, and dynamic ESC with depth discussed in Section 2.3, the -porosity cross plots of wells H6 and L1 further reveal the quantitative correlation between these two key parameters (Figure 10). The data in the cross plots fully cover the actual porosity distribution of the main reservoir lithologies in the study area (i.e., mudstone, argillaceous siltstone, and fine sandstone). Combined with the logging data of the study block, the porosity of mudstone is mostly concentrated in the range of less than 0.1; the porosity of argillaceous siltstone is mainly distributed between 0.1~0.2; the porosity of fine sandstone is mainly in the range of greater than 0.2. This lithology-specific porosity distribution ensures the representativeness of the cross-plot data for analyzing the -porosity relationship.

Figure 10.

Cross plot of porosity and the effective stress coefficient: (a) well H6; (b) well L1.

From the data distribution trends, exhibits a significant positive correlation with porosity:

- For dense mudstone (porosity less than 0.1), the value is less than 0.4, which is completely consistent with the logging results of the lower reservoir section of well H6, where the porosity is less than 10% and the value is relatively low;

- For argillaceous siltstone (porosity 0.1~0.2), the value is concentrated in the range of 0.4~0.7, matching the evolutionary characteristics of observed for intercalated argillaceous siltstone in the reservoir section of well L1;

- For fine sandstone (porosity greater than 0.2), the value is greater than 0.7, which further verifies the rule proposed in Section 2.2 that “sandstone layers with higher porosity have larger ESCs”.

Notably, the effective stress coefficient () is mainly distributed in the range of 0.3~0.8, which is highly consistent with the dynamic effective stress coefficient estimation results derived in Section 2.1 (based on the Gassmann equation and the approximation of compressional wave modulus). This consistency confirms that the proposed method can accurately capture the influence of lithology (reflected by porosity differences) on . It provides intuitive parameter correlation support for α estimation in multi-lithology formations and lays a solid foundation for subsequent formation pressure prediction when shear wave velocity data are missing. For similar multi-lithology formation environments, Zhou et al. (2023) [37] also found that the effective stress coefficient has a significant positive correlation with porosity, which further supports the reliability of the cross-plot analysis results in this study.

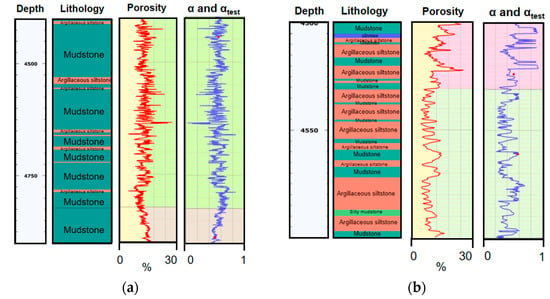

4.2. Comparison with Logging Results

The ESCs of the samples obtained in the laboratory at different depths in Section 3 calibrate the logging results. Figure 11 shows the change curve of the ESC of the two wells with depth, and the points are the experimental test results. The average ESC of sample H18 is 0.64, and the average ESC of sample H48 is 0.50, which is in good agreement with the logging results, with an error range within 5%. The average ESC of sample L11 is 0.48, and the average ESC of sample L15 is 0.51, which is also in good agreement with the ESCs estimated by logging, with an error range of about 7.2%.

Figure 11.

Calibration of logging curves by experimental results: (a) well H6; (b) well L1.

To clarify the calculation basis of this error range, the following method is adopted: taking the experimental results as the true value, the absolute error between the logging estimated value and the experimental true value is calculated first, then the average value of the absolute error is obtained, and finally the error range is derived by dividing the average absolute error by the average value of the experimental true value. Specifically, assuming the logging estimated values of a sample are , , …, , and the experimental true value is , the absolute error of each point is , the average absolute error is , and the error range is , where is the average value of the experimental true value. This calculation confirms that the dynamic ESC calculation method based on P-wave velocity is reliable, and the dynamic ESC change curve along the wellbore direction can be obtained.

4.3. Analysis of Influencing Factors of Effective Stress Coefficient

For underground dense rocks, under constant differential stress, the wave velocity increases with the increase in confining pressure, indicating that the wave velocity is not a function of differential stress, but a function of effective stress, and the ESC is less than one. The ESC of the study block is mainly distributed in the range of 0.3~0.8, which is consistent with the previous research results [8,9,10,11,17].

The ESC decreases with the increase in differential stress. As the difference between confining pressure and pore pressure, differential stress is the effective compressive force acting on the rock skeleton. On the one hand, under low differential stress conditions, the “soft pores” with low stiffness, such as micro-fractures, interlayer pores of clay minerals, and organic matter pores, are significantly closed (the slopes of the curves in Figure 8 and Figure 9 are steep at the initial stage). After the “soft pores” are closed, the pore space decreases irreversibly, which weakens the contribution of pore fluid to rock deformation. Under high differential stress conditions, the remaining pores are mainly intergranular pores of rigid minerals such as quartz, which have strong compressive resistance and are difficult to further compress (the curves in Figure 8 and Figure 9 are gentle in the later stage), resulting in the solidification of the response of the pore system to fluid pressure. On the other hand, the increase in differential stress leads to the shrinkage or even closure of micro-nano scale throats, and the pore connectivity decreases sharply. At this time, the pore fluid is isolated in closed units, making it difficult to form a global pressure balance. The fluid pressure can only form local high-pressure zones in isolated pores and cannot be uniformly transmitted to the entire skeleton. According to Biot’s theory, the actual contribution of pore pressure to effective stress is thus reduced.

In general, as a key parameter connecting pore fluid pressure and rock skeleton mechanical response, the ESC has a decisive impact on the elastic properties of rocks. The ESC directly regulates the effective stress, which in turn affects the wave velocity propagation characteristics. According to Biot’s effective stress principle (), the ESC determines the effeciency of pore pressure in offsetting the overlying confining pressure. In the experimental study of Chapter 3, the ESC () of argillaceous siltstone is in the range of 0.5~0.6, which is significantly lower than that of conventional sandstone () [8,9,10,11,17,27]. This characteristic makes the change in rock effective stress less than the change in pore pressure. Specifically, when the pore pressure increases, due to α < 1, the reduction in effective stress is weakened, so that the compaction state of the rock skeleton can be partially maintained, and the decrease in acoustic wave velocity (especially P-wave velocity) is reduced.

The ESC also acts as a core factor affecting wellbore overall quality, primarily by modulating the effective stress state of the surrounding formation rock. When the ESC is large (e.g., α ≈ 0.8 in high-porosity sandstone), pore pressure exerts a prominent “offset effect” on confining pressure—small fluctuations in pore pressure can trigger large variations in rock effective stress. In such cases, underestimating the ESC (and thus formation pressure) would lead to insufficient drilling fluid density, elevating the risk of wellbore collapse due to excessive effective stress; conversely, overestimating the ESC would result in overly high drilling fluid density, causing lost circulation or formation damage. When the ESC is small (e.g., α ≈ 0.5 in dense mudstone), the rock skeleton bears most of the confining pressure, rendering the wellbore less sensitive to pore pressure changes and enhancing its relative stability. This link between ESC and wellbore conditions means multiple critical drilling prediction results depend on accurate ESC quantification [30,36]: it directly participates in effective stress calculations (Equation (1)), so its precision dictates the reliability of formation pressure predictions—the core basis for defining the safe drilling fluid density window [22]; it shapes the effective stress state of surrounding rock, making it a key parameter for assessing drilling risks like collapse, lost circulation, and stuck pipe; it reflects pore connectivity and fluid mobility, so it aids in evaluating reservoir productivity potential (higher ESC typically correlates with better connectivity and seepage capacity); and it is integral to constructing wellbore mechanical models, guiding the optimization of parameters like drilling fluid density and speed to ensure long-term borehole stability.

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Based on the Gassmann equation and P-wave modulus approximation, this study realizes a multi-lithology ESC estimation method using P-wave velocity, density, and porosity, and applies it to the logging of the study block. Experimental verification confirms the method’s reliability, enabling ESC estimation and formation pressure prediction in the absence of shear wave velocity.

- (2)

- The study block’s dense mudstone/argillaceous siltstone (low porosity) exhibits ESC < 1: logging-derived ESC ranges 0.3–0.8, and laboratory-averaged ESC is 0.5–0.6 (lower than conventional sandstone’s α ≈ 1). Poor pore connectivity in dense rocks weakens fluid pressure’s contribution to effective stress, so setting ESC = 1 for formation pressure prediction is inappropriate.

- (3)

- The ESC decreases with increasing differential stress (confining pressure—pore pressure).

Author Contributions

Z.W.: Writing—original draft; K.H.: Writing—original draft and Methodology; D.L.: Funding acquisition; Q.R.: Data curation; M.J. and Z.C.: Methodology; K.R. and X.W.: Data processing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (42374132) and Scientific Research Project of CNOOC (SCKY-2024-SZ-YJYKT-02).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to privacy considerations.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Zhuochao Wang, Daoli Liu, Man Jiang and Zhaoming Chen were employed by the company Shenzhen Branch of CNOOC, Ltd. Authors Zhuochao Wang, Daoli Liu, Man Jiang and Zhaoming Chen were employed by the company CNOOC Deepwater Development Limited. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Terzaghi, K. Theoretical Soil Mechanics; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1923. [Google Scholar]

- Biot, M.A. General theory of three-dimensional consolidation. J. Appl. Phys. 1941, 12, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biot, M.A. Theory of propagation of elastic waves in a fluid saturated porous solid. I. Low frequency range and II. Higher—Frequency range. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1956, 28, 168–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berryman, J.G. Effective stress for transport properties of inhomogeneous porous rock. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1992, 97, 17409–17424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berryman, J.G. Effective-stress rules for pore-fluid transport in rocks containing two minerals. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1993, 30, 1165–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, A.; Byerlee, J.D. An exact effective stress law for elastic deformation of rock with fluids. J. Geophys. Res. 1971, 76, 6414–6419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, B. A simple derivation of the effective stress coefficient for seismic velocities in porous rocks. Geophysics 2004, 69, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banthia, B.S.; King, M.S.; Fatt, I. Ultrasonic shear-wave velocities in rocks subjected to simulated overburden pressure and internal pore pressure. Geophysics 1965, 30, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, T.; Simmons, G. Effect of pore pressure on the velocity of compressional waves in low-porosity rocks. J. Geophys. Res. 1972, 77, 3731–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornby, B.E. An experimental investigation of effective stress principals for sedimentary rocks. In Proceedings of the 66th Annual International Meeting of the Society of Exploration Geophysicists, Denver, CO, USA, 10–15 November 1996; pp. 1707–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, R.; Batzle, M. Effective stress coefficient in shales and its applicability to Eaton’s equation. Lead. Edge 2008, 27, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilterman, F. Seismic Amplitude Interpretation; Society of Exploration Geophysicists: Huston, TX, USA; European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers: Odijk, The Netherlands; Geophysical Development Corporation: Houston, TX, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Geertsma, J. Velocity-log interpretation. The effect of rockbulk compressibility. Soc. Petr. Eng. J. 1961, 1, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krief, M.; Garat, J.; Stellingwerff, J.; Ventre, J. A petrophysical interpretation using the velocities of P and S waves (full-waveform sonic). Log Anal. 1990, 31, 355–369. [Google Scholar]

- Nur, A.M.; Mavko, D.; Dvorkin, J.; Gal, D. Critical porosity: The key to relating physical properties to porosity in rocks. In Proceedings of the 1995 SEG Annual Meeting, Houston, TX, USA, 8–13 October 1995; pp. 878–881. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.G. Experimental investigation into Biot’s coefficient and rock elastic moduli. Oil Gas Geol. 2008, 29, 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H. Dynamic effective pressure coefficient calibration. Geophysics 2015, 80, D65–D73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.C.; Li, J.X.; Wang, Y. Research on dynamic effective stress coefficient of tight sandstone reservoirs. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 190, 107125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.C. Experimental study on dynamic and static effective stress coefficients of transversely isotropic shale. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2023, 42, 4130–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.S.; Hu, T.Y. Estimation of the effective stress coefficient for multi-lithology. In Proceedings of the 78th SEG Annual International Meeting, Dallas, TX, USA, 16–21 October 2016; pp. 3200–3204. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, M.X.; Liu, Z.D.; Yang, X.F.; Yang, J.R.; Chen, X.J.; Liu, H.Z.; Cao, J. Review and prospect of formation pore pressure prediction technology by geophysical well logging. Prog. Geophys. 2020, 35, 1845–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyllie, M.R.J.A.; Gregory, R.; Gardner, L.W. Elastic wave velocities in heterogeneous and porous media. Geophysics 1956, 21, 41–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassmann, F. Über die Elastizität poroser Medien. Veirteljahrsschrift Der Naturforschenden Ges. Zürich 1951, 96, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett, G.R. Acoustic Charater Logs and Their Applications in Formation Evaluation. J. Pet. Technol. 1963, 15, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavko, G.; Mukerji, T.; Dvorkin, J. The Rock Physics Handbook—Tools for Seismic Analysis in Porous Media; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mavko, G.; Chan, C.; Mukerji, T. Fluid substitution: Esti-mating changes in Vp without knowing Vs. Geophysics 1995, 60, 1750–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batzle, M.; Wang, Z. Seismic properties of pore fluids. Geophysics 1992, 57, 1396–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos da Silva, M.; Schroeder, C.; Verbrugge, J.C. Poroelastic behaviour of a water-saturated limestone. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2010, 47, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.Y.; Li, M.; Zhuang, M.W.; Sun, Y. Rock physics model for velocity–pressure relations and its application to shale pore pressure estimation. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, G.L. Pore pressure estimation from velocity data: Accounting for overpressure mechanisms besides under compaction. Geophysics 1995, 60, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Rui, Z.H.; Ling, K.G. A new method to determine Biot‘s coefficients of Bakken samples. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 35, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.C.; Gidlow, P.M. Weighted equation for fluid substitution in sandstones. Geophysics 1987, 52, 1396–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejtrakulwong, P.; Mavko, G. Fluid substitution for thinly interbedded sand-shale sequences using the mesh method. Geophysics 2016, 81, D599–D609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.W.; Ma, T.; Zu, K.; Wang, Q.; Yang, F.; Zhou, H. Research progress of testing method and characterization model of effective stress coefficient of rock. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2025, 44, 1959–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, T.Y. Prediction study of tight sandstone reservoirs: A case study of tight sandstone reservoirs in Lishu area. Basic Sci. Eng. Technol. Ser. I 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, B.A. The equation for geopressure prediction from well logs. J. Pet. Technol. 1975, 27, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.Q.; He, X.L.; Lin, K.; Qin, S.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Z. Formation pressure estimation method based on dynamic effective stress coefficient. Xinjiang Pet. Geol. 2023, 44, 245–251. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.