Abstract

To address the limitations of existing power system low-carbon dispatching studies—such as over-reliance on generation-side carbon mitigation, price-oriented demand response (DR) failing to guide carbon reduction, and the low solution efficiency of traditional carbon emission flow (CEF)-based two-stage models—this paper proposes a data-driven CEF framework integrated with a bi-level economic and low-carbon dispatching model. First, a data-driven CEF calculation method is developed: It eliminates the need for complex power flow post-processing while maintaining calculation accuracy through multiple linear regression. On this basis, a bi-level optimization model is constructed: The upper level focuses on optimizing the economic and low-carbon objectives of power grid operation, while the lower level regulates industrial, commercial, and residential load aggregators (LAs) via carbon-intensity-oriented DR strategies and economic compensation mechanisms. Finally, a sample-based optimization algorithm combined with convex relaxation is proposed to solve the model, avoid the static setting of power flow and carbon intensity, and improve solution efficiency. Case studies demonstrate the following: the proposed method reduces the calculation time of node carbon intensity from 5 min to less than 100 ms, with the coefficient of determination (R2) ranging from 0.969 to 0.998; compared with the two-stage method, it achieves a 4.26% reduction in total scheduling cost, a 3.80% decrease in total carbon emissions, a 53.27% drop in carbon trading cost, and a 21.6% shortening in iteration time. These results verify that the proposed method can effectively enhance the source−load interaction and improve the accuracy and efficiency of low-carbon scheduling. This study provides a feasible technical path for the low-carbon transition of new-type power systems.

1. Introduction

With the escalating fossil energy crisis and global climate change, carbon emission reduction has emerged as a core issue on a worldwide scale [1]. Specifically, carbon emissions from China’s power sector account for approximately 40% of the country’s total carbon emissions [2]; thus, achieving carbon emission reduction in the power sector is a critical and urgent task for fulfilling China’s “carbon peaking and carbon neutrality” goals [3]. Meanwhile, with the implementation of multiple carbon emission reduction policies (e.g., carbon capture, carbon tax, and carbon emission trading) and the widespread application of carbon emission reduction technologies [4,5,6], carbon-related costs have become an important component of power system operation costs. Therefore, the introduction of carbon market mechanisms and related carbon pricing strategies into power systems is crucial for promoting the low-carbon operation of the system.

On the premise of ensuring the economic efficiency of the optimal dispatching model, most studies have focused on generation-side optimization to reduce carbon emissions. Literature [7] constructs a multi-scope carbon emission accounting framework related to electricity, demonstrating that optimizing the fuel mix of power plants can yield significant carbon reduction effects. Literature [8,9] reviews the integration pathways of clean energy and renewable energy in multi-energy systems, pointing out that multi-energy complementary systems (e.g., photovoltaic, wind power, and hydropower) can enhance power supply reliability while reducing carbon emissions. Literature [10] analyzes China’s power-related CO2 emissions from 1997 to 2017, identifying that the improvement of thermal power generation efficiency was the main factor driving carbon emission reduction in the power industry during this period. Literature [11] conducts a case study on the Tehran waste-to-energy power plant using the life cycle assessment method for analysis, finding that the waste-to-energy mode exhibits lower carbon emissions than the waste recycling and landfilling modes. Literature [12] takes Chile as a case study, showing that hydrogen production via electrolyzers on the generation side has a lower carbon intensity than traditional fossil fuel-based hydrogen production. Literature [13] performs a life cycle analysis of three electrochemical energy storage technologies, finding that combining electrochemical energy storage with photovoltaic, wind power, or future new-type power grids can reduce the system’s carbon emissions by 70–90%. Literature [14] develops a hybrid data-driven LSTM–classical optimization framework for sizing and operating a grid-connected PV–battery system in a mining application, showing that it can simultaneously reduce electricity costs and carbon emissions. Literature [15] develops a multi-objective economic-emission dispatching model for power systems with carbon capture power plants, confirming that carbon capture equipment can reduce the system’s carbon emissions by approximately 90% and providing a feasible solution for the low-carbon dispatching. Despite these advances, most studies focus solely on generation-side carbon mitigation, ignoring the low-carbon potential of the demand side and lacking effective interaction between the two sides in low-carbon optimization, making them insufficient to meet the needs of new-type power systems.

Recent alternative studies have explored emerging technologies centered on the electrification of end-use energy sectors (e.g., buildings, transportation, and industry) to reduce energy demand and enhance the controllability of energy use [16]. Among these technologies, leveraging demand-side flexibility has emerged as a promising and effective approach to improving the efficiency and reliability of future power grids [17]. Particularly with the expansion of flexible load scales—such as heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems [18], electric vehicles (EVs) [19], and other flexible loads [20]—the concept of demand response (DR) has been gradually promoted and refined, and its role in providing additional flexibility for power system operation has been verified. A growing body of literature [21,22,23] has confirmed that exploring demand-side flexibility holds significant value for power system decarbonization, as it enables more efficient integration of renewable energy sources and reduces reliance on carbon-intensive generation. However, most existing DR studies are price-oriented: while electricity prices can effectively guide loads to participate in peak shaving, they fail to direct users to implement carbon-reducing behaviors that align with the temporal fluctuation of demand-side carbon emissions, limiting the full exploitation of demand-side carbon abatement potential.

Furthermore, numerous cross-industry studies argue that the responsibility for CO2 emissions during production should be attributed to “consumers” rather than solely to “producers” [24,25,26]. In power systems, electricity users’ energy demand directly drives the combustion of fossil fuels and subsequent carbon emissions; thus, it is necessary to trace the sources and attribution of generation-side carbon emissions from the demand-side perspective. Against this backdrop, several studies have explored methodological advancements for demand-side carbon emission accounting. For instance, Miller et al. [27] propose a time-varying carbon emission calculation framework tailored to the demand side, highlighting that hourly accounting is critical to enhancing the accuracy of time-resolved carbon emission assessments for electricity consumption. Yang and Qin [28] developed a demand response (DR) model integrated with locational marginal electricity–carbon prices, which embeds marginal carbon emission factors (MCEFs) into price signals. Liu et al. [29] present a real-time enterprise carbon footprint estimation method based on equipment identification, enabling minute-level accurate monitoring of demand-side carbon emissions.

However, the aforementioned demand-side carbon emission accounting methods either require access to large amounts of users’ private information or the additional purchase of dedicated equipment, resulting in high implementation costs and hindering their practical promotion. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a more convenient demand-side carbon emission calculation method to address these limitations. Against this backdrop, the carbon emission flow (CEF) theory [30] provides important technical support for clarifying demand-side carbon emission responsibility, prompting more scholars to analyze load demand from a carbon perspective. Literature [31] employs a CEF model to track carbon flow, introduces a DR mechanism with cross elasticity, couples the electricity market and the carbon trading market, and proposes a two-stage dispatching model; it has been verified that this model can effectively reduce emissions and bring significant environmental benefits to users. Literature [32] proposes a data-driven CEF model based on Bayesian inference regression, integrates the DR mechanism with an economic compensation strategy and then constructs a dispatching optimization model to improve the dynamic accuracy of carbon tracking. Literature [33] develops a two-stage coordinated model for integrated energy-carbon pricing in multi-energy systems, traces users’ carbon contributions and sets pricing based on the CEF model, and optimizes the energy consumption strategy of the distribution network energy hub through the time-of-use (TOU) electricity price-based DR. Literature [34] combines the CEF theory with the Shapley value, proposes a DR method based on stepwise carbon trading costs and further constructs a two-stage low-carbon optimal dispatching model for power systems.

Nevertheless, when the aforementioned studies analyze load demand from the carbon perspective using CEF, they typically adopt a two-stage approach: in the first stage, the power flow distribution is obtained by solving power flow equations, and node carbon intensity is derived accordingly; in the second stage, DR is implemented based on the node carbon intensity. In such two-stage models, the CEF calculation can only be completed after solving the power flow in the first stage, and the resulting CEF values then serve as input for the second stage to guide DR implementation. However, this sequential two-stage framework suffers from two critical limitations: First, the CEF calculation relies on solving nonlinear power flow equations, which significantly increases the computational complexity of the entire model. Second, the sequential separation of the two stages (i.e., power flow−CEF calculation followed by DR implementation) prevents optimal coordination among the power flow optimization, CEF calculation, and DR execution. This lack of coordination not only leads to excessive iterations during the solution process but also severely compromises the optimality of the final solution. To address these issues, this paper proposes an improved CEF theory. Meanwhile, by comprehensively integrating the carbon trading mechanism and DR mechanism, this paper constructs a bi-level economic and low-carbon dispatching model: the upper level corresponds to the power grid operator, and the lower level consists of load aggregators (LAs) (including industrial, commercial, and residential LAs). Finally, a sample-based optimization algorithm is employed to solve this bi-level model. Unlike the two-stage method, this algorithm avoids setting power flow and carbon intensity as static parameters, thereby enabling efficient and accurate solution of the proposed bi-level model. The comparisons between this paper and related research are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The comparisons between this paper and related research.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

- (1)

- Data-Driven CEF Calculation: Unlike traditional CEF calculation, which requires complex power flow computation, our proposed data-driven CEF calculation method directly incorporates pre-fitted functional relationships of load-side CEF into the lower-level DR model. This eliminates the need for cumbersome nonlinear power flow-solving processes, thereby creating favorable conditions for constructing an efficient bi-level coordinated optimization model.

- (2)

- Bi-Level Low-Carbon Economic Dispatching Model: We construct a bi-level model with clear hierarchical responsibilities—upper level (power grid operator) for system-wide economic and low-carbon optimization and lower level (industrial/commercial/residential LAs) for demand-side regulation via carbon-oriented DR and economic compensation. This approach addresses the deficiencies in existing models, such as insufficient interaction between the generation and demand sides and the inability of price-only DR to guide carbon reduction, enabling effective coordinated optimization of generation and demand sides.

- (3)

- Sample-Based Optimization Algorithm for the Bi-Level Model: We adopt a sample-based optimization algorithm to solve the bi-level model, which avoids the inefficiency and suboptimality inherent in the iterative process of traditional two-stage methods. This ensures a more efficient solution convergence while enhancing the optimality of the dispatching results.

2. Data-Driven Carbon Emission Flow

2.1. CEF Model

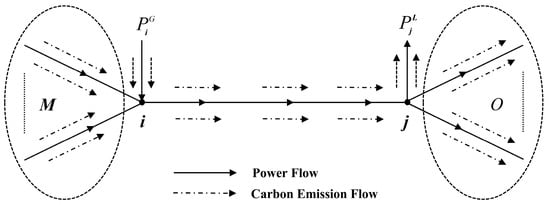

In the classic carbon-emission-flow model, the relationship between power flow and carbon flow in the system is illustrated in Figure 1: power flow from node i to node j is defined as the positive direction; M denotes the set of branches entering node i, and O denotes the set of branches leaving node j; solid lines represent power flows, whereas dashed lines represent carbon-emission flows.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the relationship between carbon emission flows and currents.

According to [30], for a given node i, its nodal carbon emission intensity only depends on the total inflow branch carbon emission flow and the ejected carbon emission flow from any generators at this node; all the outflow branches from this node share the same branch carbon emission flow intensity, and its value equals to the nodal carbon intensity of the node which they travel out. Accordingly, the nodal carbon intensity at node i is expressed as follows:

where denotes the set of branches with inflow power; and denote the carbon-emission intensity and the active power for the branch with inflow power, respectively; and denote the carbon-emission intensity factor and the active power output of the generator connected to node i, respectively.

One then obtains the nodal active power flux matrix as

where is a row vector of ones; and denote the numbers of buses and units, respectively; “diag” represents the diagonal matrix operator; is the -by- diagonal branch-flow distribution matrix, with denoting the active power flow between node and node ; and is the -by- generator-injection matrix; is the active power output of the th generator connected at node .

Based on the definition in Formula (2), Formula (1) can be reformulated in the following matrix form:

where is a N-dimensional row vector, and only the th element equals 1; is the N-dimensional column vector; and is the K-dimensional column vector.

Therefore, the nodal carbon intensity at each node in the system can be calculated as follows:

From Formula (4), CEF calculation relies heavily on the branch outflow power distribution matrix , derived by solving nonlinear power flow equations. Therefore, the conventional CEF calculation method exhibits significant limitations in supporting the required coordinated interaction between the upper-level system operator and the lower-level Las for constructing the bi-level low-carbon economic dispatching model, specifically as follows:

- (1)

- Dependence on precomputed power-flow results

Traditional CEF models calculate nodal carbon intensity through large-scale matrix operations, inherently relying on pre-obtained power-flow data. However, key variables (e.g., generator outputs and load demands) in the bi-level framework are dynamic, updated continuously through inter-level iterations. This dynamic nature requires real-time, on-the-fly computation of nodal carbon intensity during the optimization process, rather than treating it as a post-processing step after power flow convergence. Since conventional CEF methods are tightly coupled with time-consuming power flow solving and can only generate nodal carbon intensity after full power flow calculation, they fail to meet this real-time requirement and thus become a bottleneck in iterative optimization. More critically, this dependence impedes the direct embedding of nodal carbon intensity into the lower-level demand response model, impairing the accuracy of LAs’ flexible load scheduling and hindering upper−lower-level coordination.

- (2)

- Nonlinearity introduced by matrix inversion

Conventional CEF computing involves inverting large, sparse matrices, which inherently introduces nonlinearity into the optimization process. However, mainstream bi-level optimization solvers (e.g., for linear programming (LP) or mixed-integer linear programming (MILP)) are poorly suited for such nonlinearity. The nonlinearity stemming from matrix inversion not only dramatically increases computational complexity but also may prevent converging—or even initiating—the optimization. This issue, combined with the rigid sequence of “power flow calculation first, CEF computation later” in traditional methods, ultimately leads to inefficient repeated iterations and suboptimal final solutions.

2.2. Proposed Regression Model for CEF Calculation

From a data-driven perspective, the core challenges of traditional CEF methods—reliance on complex pre-computed power flow results and nonlinearity from matrix inversion—can be effectively addressed based on the linearizable nature of the intermediate variable and the time-segmented linear approximation of the overall nonlinear relationship. More specifically, for low-carbon economic dispatching purposes, can be accurately approximated using the Power Transfer Distribution Factor (PTDF) method—a widely accepted linearization technique in power system dispatch. The PTDF-based DC power flow simplifies nonlinear AC power flow equations into linear relationships among generator outputs , load demands , and branch power flows, laying the foundation for establishing the mapping between nodal power injections and associated nodal carbon intensities via data-driven techniques.

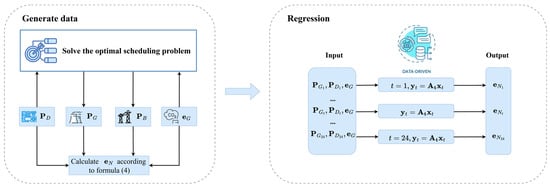

Accordingly, this paper proposes a data-driven regression model that directly constructs a functional mapping from measurable input variables (e.g., generator outputs and load demands) to nodal carbon intensity. Critically, this model eliminates the need for post-processing of power-flow results or nonlinear matrix operations—two major bottlenecks of conventional methods. Its rationality is supported by two key premises: first, voltage angle differences across branches are small during normal power system operation, and the impact of reactive power on active power flow is negligible for dispatch-level optimization, validating the PTDF-based linearization of ; second, under fixed grid topology and stable operating conditions (ensured by a 1 h dispatch step in this study), the relationship between and nodal carbon intensity can be well approximated by a linear sensitivity expression. Therefore, can be represented as a first-order mapping function of . This enables seamless integration into the bi-level optimization framework (particularly fitting the lower-level DR model, where real-time carbon intensity guidance is required). The workflow of the proposed regression model is illustrated in Figure 2. In this figure, represents the known variable for nodal load with a dimension of and provides information regarding locations and magnitudes, analogous to . By eliminating redundant intermediate computational steps (e.g., iterative power flow solving), the model not only reduces computational latency but also enhances the accuracy and stability of carbon-related variables in dynamic optimization scenarios. Furthermore, although the overall relationship between and is nonlinear due to the coupling of factors such as time-varying renewable energy output and load distribution, this nonlinearity can be approximated as a series of local linear relationships when the time interval is sufficiently fine (i.e., “local” linearity rather than “global” linearity). Adopting a 1 h dispatch step (24 time segments per day) ensures that operating conditions (e.g., , , and grid topology) within each segment are relatively stable, where nonlinear coupling effects are weak enough to be ignored. With a large-scale, representative sample set covering different time segments employed as the input for offline training, the learned regression parameters can be applied directly to short-term nodal carbon intensity monitoring and calculation—without heavy dependence on time-consuming power-flow solving. It is also worth noting that reducing the interval length (with higher-resolution data available) can further tighten the local linear approximation, albeit at the cost of additional coefficient estimation effort.

Figure 2.

Process of the proposed regression model.

The predictor variables—generator output (), load demand (), and unit carbon emission intensity ()—are selected based on both physical mechanisms and engineering practicality. From a physical perspective, these three variables are the core drivers of nodal carbon intensity: PG determines the carbon supply potential of the system, as the output of thermal power units (the primary carbon sources) directly dictates the total carbon emissions injected into the grid; PD regulates the spatial-temporal distribution of carbon flow, as load demands at different nodes drive the propagation of carbon emissions from generation nodes to consumption nodes; defines the inherent carbon attribute of each generator, reflecting the carbon emission factor of the fuel used (e.g., coal-fired units have higher than renewable energy units), which is a fundamental parameter for calculating initial carbon emissions. From an engineering perspective, this variable combination can be directly acquired from the existing power grid monitoring system without the need for additional collection of user private data or installation of dedicated sensing equipment. This ensures the model’s feasibility for practical deployment while avoiding privacy concerns and high implementation costs.

Mathematically, the generalized linear regression model for nodal carbon intensity can be expressed as:

The input side comprises known variables transformed from , , and . Specifically, is constructed by extracting the diagonal elements of the matrix obtained from pre-multiplying by an auxiliary matrix , where if the th customer is located at bus , and otherwise. Similarly, can be obtained by the same procedure. Furthermore, results from pre-multiplying with an auxiliary matrix . These transformations unify the notation with conventional CEF calculations, and the required matrices can be easily derived from the system topology. As discussed in Section 2.1, constitutes a constant term, while and vary dynamically with time at each steady state. Our objective is to establish a regression model that maps known variables to unknown parameters by estimating vector . Note that the output of the regression model, which captures the relationship between power injection and carbon intensity, would still be available without changing the physical topology.

Formula (6) adopts the classical linear regression form: , where represents the dependent variable matrix and collects the independent variables , , and . By incorporating multiple scenarios across different time instances, and are extended from single column vectors to full matrices. They can thus be expressed as follows:

Here, the subscripts correspond to time indices through . The aforementioned matrices can be succinctly represented by their row vectors as , , and . Furthermore, each column of corresponding to a column of can be estimated by regression. Specifically, for a given , the regression formula can be expressed as:

where denotes the row vector corresponding to the -th row of matrix .

Under the classical Gauss–Markov assumptions—that the regression errors are homoscedastic, uncorrelated, and have zero mean—the ordinary least squares (OLS) estimator achieves the minimum variance among all linear unbiased estimators. The core task of parameter estimation is to determine the optimal regression coefficients that minimize the deviation between the model’s predicted and observed nodal carbon-intensity values. In this study, the residual sum of squares (RSS) is adopted as the loss function, defined as:

The RSS is expressed in matrix form:

If has full row rank, so that is invertible, differentiating Formula (9) and setting the gradient to zero yields the canonical OLS normal equation, from which can be solved as:

2.3. Flexible Load Carbon Emissions Calculation

Using the proposed data-driven CEF regression approach, this study computes nodal carbon intensity over successive time intervals, with these intensity signals subsequently transmitted to the LAs. Within the incentive-contract framework, each LA leverages the nodal carbon intensity data to implement DR for flexible loads (e.g., electric vehicle (EV), curtailable load (CL), and transferable load (TL)) and quantifies the carbon emissions generated by these flexible loads at their respective node. By comparing load-related carbon emissions before and after DR implementation, the model quantifies the carbon-reduction benefit. Through this process, a flexible-load carbon-emission model based on the nodal carbon intensity regression model is ultimately established.

- (1)

- EV Model

Once the LA and an EV owner sign a contract, the LA acquires the authority to dispatch the authorized EV throughout the contract period. Leveraging this authority, the LA can autonomously schedule the EV’s charging/discharging time windows and allocate charging/discharging power according to grid operating conditions, nodal carbon-intensity signals, and user demand. Mathematically, this relationship is expressed as:

where denotes the total sum of charging and discharging power of all connected EVs at time ; and denote the charging and discharging power of the -th EV at time , respectively; represents the total number of EVs.

- (2)

- CL and TL Models

Under the incentive contract framework, we clarify the operational mechanisms for CL and TL. The contract defines core terms including load reduction volume and corresponding compensation payments. Specifically, for CL, a pre-signed agreement is concluded between the user and the LA. During peak periods, the user reduces their load by a pre-agreed proportion. In return, the LA provides financial remuneration to the user based on the actual curtailed consumption. For TL, the load can be shifted across time windows permitted by the power system (e.g., from peak to off-peak periods). A critical constraint here is that the total amount of transferable load in each time interval must not exceed the system’s pre-defined maximum allowable limit, to avoid imposing additional pressure on the grid. Importantly, over the entire dispatchable period , the total cumulative system load remains constant before and after any TL shifts—this ensures that TL adjustment only optimizes the temporal distribution of load (to align with low-carbon periods) rather than altering the overall energy demand.

where denotes the net adjustment power of CL and TL at time ; and denote the amounts of transferable load shifted into and out of the system during interval , respectively; is the load curtailed in interval ; is a binary variable equal to 1 if curtailment occurs in interval ; is the maximum curtailment for CL; and are binary status variables indicating TL import and export in interval ; and represent the maximum allowable shifted-in load limit and maximum allowable shifted-out load limit for TL, respectively.

Based on the above, the actual carbon emissions at node are calculated as the sum of three components: the node’s initial load-related carbon emissions, the carbon emission resulting from the net adjustment power of CL and TL at time , and the carbon emissions from the EV charging/discharging process. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

where denotes the actual carbon emissions of LA; denotes the initial load at node at time , which encompasses both rigid loads (non-adjustable) and baseline flexible loads (i.e., CL/TL without demand response).

- (3)

- Ladder Carbon-Trading Model Based on Nodal Carbon Intensity

To further enhance the governance of carbon emissions and stimulate LAs’ initiative in energy conservation and emission reduction, this study develops a ladder carbon trading model based on nodal carbon intensity. Each LA is assigned an initial carbon emission quota. By incorporating nodal carbon intensity information, the model computes each LA’s actual carbon emissions. If actual emissions exceed the allocated quota, the LA must purchase additional carbon emission permits from the carbon market; conversely, any surplus allowances may be sold to generate revenue. The actual volume of carbon emission permits traded by an LA in the carbon market is given by the following formula:

where is the initial carbon-emission allowance allocated to the node and is the carbon-emission allowance coefficient per unit of purchased electricity.

To optimize carbon abatement potential, this study employs a ladder carbon trading mechanism to calculate trading costs. For any emissions exceeding the initial allowance, the surplus is segmented into predefined brackets, and the cost for each bracket is computed separately. Critically, within each bracket, the unit carbon trading price escalates incrementally as the volume of purchased permits increases—creating a steepening cost gradient that incentivizes LAs to prioritize emission reductions over excessive permit purchases.

where denotes the ladder carbon trading cost; denotes the baseline carbon-trading price; represents the length of each carbon-emission interval, and is the price-escalation coefficient.

3. Bi-Level Optimization Scheduling Model

3.1. Model Structure

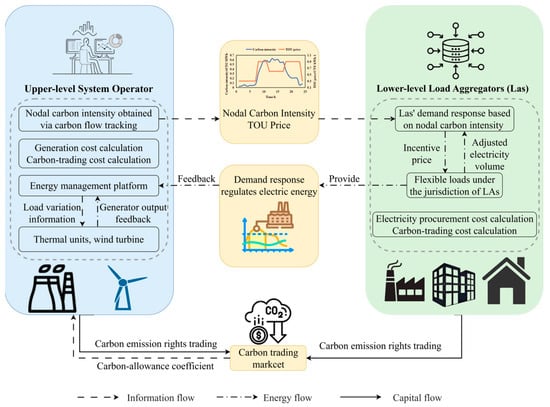

As illustrated in Figure 3, this paper proposes a bi-level low-carbon economic dispatch framework based on nodal carbon intensity. At the upper level, the system operator receives carbon-allowance coefficients from the trading platform and simultaneously optimizes generator outputs by balancing generation costs against carbon-trading costs. Nodal carbon intensity is then computed via carbon-flow regression and conveyed—together with TOU price signals—to the corresponding lower-level LAs. Each LA (residential, commercial, or industrial) aggregates the flexible loads under its jurisdiction and, upon receiving nodal carbon-intensity signals, assumes the corresponding carbon-emission responsibility and adjusts its consumption strategy. Under incentive contracts, the LA dispatches flexible loads and revises its power-purchase plan, which is subsequently fed back to the system operator. The operator then updates generator schedules and recalculates nodal carbon intensity. This iterative loop continues until the global dispatch objective is achieved.

Figure 3.

Diagram of the bi-level optimization operational framework.

3.2. Upper Model Formulations

The system operator aims to minimize the total operation cost, which consists of four key components: the thermal-power unit generation cost , the wind-power unit generation cost , the wind-curtailment cost , and the operator’s carbon-trading cost . Mathematically, this multi-component objective function is formulated as:

where is the total number of generating units; , , and are the fuel-consumption cost coefficients of the th thermal unit; is the output of the ; is the total number of wind turbines; is the wind-generation cost coefficient; is the actual output of the th wind turbine at time ; denotes the number of wind-power scenarios; is the probability of the th wind-power scenario; is the penalty coefficient for wind curtailment; is the forecast output of the th wind turbine at time under the th scenario; and are the carbon-emission intensity factor per unit of generation and the initial carbon-allowance coefficient, respectively.

The upper-level optimization model is subject to multiple operational constraints to ensure technical feasibility and economic rationality, each formalized with mathematical expressions:

where and denote the maximum and minimum outputs of thermal unit , respectively; is the output of unit at time ; and are its maximum ramp-up and ramp-down rates, respectively; is the active power flow on line at time ; and are the upper and lower transmission limits of line , respectively; is the set of thermal units at node ; is the set of wind turbine generators at node ; is the set of lines connected to node ; is the electric load at node j at time ; is the reactance of line ; and are the voltage phase angles at nodes and at time , respectively.

3.3. Lower Model Formulations

The load aggregator seeks to minimize its total operational cost, which integrates the following core components: the cost of electricity procured from the upper-level system operator, the implementation cost of DR actions (e.g., user compensation for CL curtailment, TL shifting, or EV discharge incentives), and the LA’s own carbon-trading cost (derived from the ladder carbon trading mechanism). Mathematically, this objective function is formulated as:

where , , , , and denote electricity procurement cost from the upper-level grid operator, the cost of curtailable-load demand response, the cost of transferable-load demand response, the subsidy cost for EV discharging, and the LA’s carbon-trading cost, respectively. Each cost component is calculated using the following formulations:

In Formula (21), , , , and denote the TOU electricity price, the cost coefficient for CL demand response, the cost coefficient for TL import, and the cost coefficient for TL export, respectively; is the subsidy coefficient for EV discharging.

Power-balance constraint:

EV charging and discharging constraint:

where and are binary variables indicating the charging and discharging status of the th EV at time ( when charging; when discharging); and note the maximum charging and discharging power of the EV, respectively.

EV battery power constraint:

where and denote the initial and target stored energy of EV , respectively; and are its connection and departure times, respectively; and are the charging and discharging efficiencies, respectively; and represent the states of charge of EV at times and , respectively; is the battery’s rated capacity; and represent the upper and lower bounds on its state of charge, respectively.

4. Algorithm

4.1. Bi-Level Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Optimization Problem

Based on the upper-level grid operator’s optimal scheduling problem (17) and the lower-level LA’s demand response optimization problem (20), the integrated framework is formulated as a bi-level mixed-integer nonlinear programming (BI-MINLP) problem. Its compact mathematical expression is structured as follows:

where denotes the decision variable controlled by the leader (the upper-level grid operator), and represents the decision variable controlled by the follower (the -th LA at the lower level); stands for the optimal decision variable of the follower; the inequalities and correspond to the constraints of the upper-level model and the lower-level model, respectively.

It is noteworthy that solving the bi-level optimization problem (25) poses challenges, with technical difficulties manifested primarily in the following aspects. First, the lower-level model involves non-convex integer variables due to the use of 0–1 binary variables to characterize the operational states of flexible loads and EVs at each time step. This non-convexity prevents substituting the lower-level problem with its KKT optimality conditions, thus hindering the transformation of the bi-level problem into a single-level mathematical program with equilibrium constraints (MPEC). Second, in the bi-level model, the node carbon intensity values derived by the upper level are transmitted to the lower level. The calculation of node carbon emissions at the current time requires implementing the product of the node carbon intensity and the purchased power after the lower-level DR, introducing nonlinear terms due to the product of two decision variables. To address these challenges, the following methods are employed: (1) a sample-based approach is adopted to reformulate the bi-level problem into an equivalent single-level optimization problem, followed by the development of an exact sample-based optimization algorithm for its solution; (2) the McCormick linearization technique is used to handle the nonlinear product terms. The relevant solution methods are elaborated in subsequent sections.

4.2. Solution Methodology

In this section, we elaborate on the detailed procedural steps of the sample-based algorithm and demonstrate its application in reformulating (26) into an equivalent single-level optimization problem. Prior to this reformulation, the following notations are formally defined to establish a consistent mathematical framework:

Define as the constrained feasible region of the leader’s decision given the followers’ decision variables . Define as the feasible region of problem (25) after relaxing the optimal constraints of the followers. Define as the projection of onto the leader’s decision space. Define as the set of optimal solutions for the follower given the leader’s decision variable .

Definition: A solution is bi-level feasible for problem (25) if and .

Based on the aforementioned definitions, optimization problem (25) can be equivalently reformulated as the following single-level optimization problem:

In the equivalent single-level optimization problem (26), constraint (27) ensures that both the upper-level and lower-level constraints are satisfied, while constraint (28) guarantees the optimality of solutions for the lower-level subproblem. Solving problem (26) requires knowledge of the decision spaces of all followers. However, enumerating all decision spaces consumes substantial computational resources and is extremely time-consuming. To address this challenge, we propose a sample-based optimization algorithm for solving optimization problem (26), which circumvents exhaustive enumeration through probabilistic sampling and convex relaxation techniques.

4.3. Sample-Based Optimization Algorithm Step

In this section, we propose an exact sample-based optimization algorithm for solving problem (26). First, instead of solving optimization problem (26) directly, we iteratively solve the following sequence of subproblems:

where denotes the iteration index; the sample represents a subset of the follower’s decision space , with one new element added to the sample per iteration.

The iterative process of the proposed algorithm is detailed as follows:

Step 1: Initialize parameters

Set , and initialize the sample as an empty set.

Step 2: Solve problem (29) based on samples

If optimization problem (29) is infeasible under the current sample , the original optimization problem (29) is infeasible and the algorithm terminates. Otherwise, an optimal solution can be obtained, and the new upper bound is set as .

Step 3: Update the sample

For the given upper-level solution , solve the follower’s optimal problem to obtain the follower’s optimal response solution . Then, update the sample for the next iteration as .

Step 4: Check if the solution is bi-level feasible to problem (26)

Since we cannot guarantee , the solution may not be bi-level feasible. Bi-level feasibility can be determined by verifying whether holds. If it holds, then both and belong to , and thus, is globally optimal. Specifically, within the model presented in this study, for the given leader decision , we re-solve the complete follower MILP encompassing all lower-level constraints: these include power balance constraint (22), EV constraints (23) and (24), DR constraints for CL and TL, as well as the McCormick-relaxed carbon terms (30) and (31). Only when this MILP is feasible and yields an optimal follower response do we recognize as bi-level feasible. In this case, we update the lower bound of the algorithm as , and the algorithm terminates with the optimal solution .

Step 5: If is not bi-level feasible, check whether is bi-level feasible to problem (26)

If , then the solution is bi-level feasible. Next, compute . If the solution is bi-level feasible and (indicating this solution improves the lower bound), update the algorithm’s lower bound as ; otherwise, set .

Step 6: Check algorithm termination

In each iteration, compare with . When , the algorithm terminates, obtaining the optimal solution; otherwise, the algorithm returns to Step 2 to repeat the iteration.

The iterative procedure of the proposed algorithm is summarized in Algorithm 1:

| Algorithm 1 Sample-based Optimization Algorithm for Optimization Problem (26) | |

| 1: | Initialize , set ; |

| 2: | while do |

| 3: | If optimization problem (29) about is infeasible, then |

| 4: | Terminate; original optimization problem (26) is |

| infeasible; | |

| 5: | else |

| 6: | Obtain an optimal solution to (30) about |

| and set ; | |

| 7: | Solve , and |

| obtain an optimal follower response ; | |

| 8: | Update sample ; |

| 9: | if then |

| 10: | Update and ; |

| 11: | else if and then |

| 12: | Update ; |

| 13: | else |

| 14: | ; |

| 15: | end if |

| 16: | end if |

| 17: | Set ; |

| 18: | end while |

| 19: | Return |

4.4. McCormick Linearization of Nonlinear Terms

Although the proposed iterative sample-based optimization algorithm is used to solve BMINLP (26), sub-problem (29) solved iteratively still possesses nonlinear characteristics. As can be seen from Formula (14), both contain nonlinear terms and , and it is these terms that render the constraints nonlinear. In what follows, the McCormick linearization method is employed to linearize sub-problem (29):

Based on the above analysis, the nonlinear terms in optimization problem (29) can be replaced by (30) and (31). Specifically, is set to 0, which corresponds to the theoretical lower limit under the zero-carbon emission scenario of wind turbine generators, while is determined based on the maximum generator emission factor.

On this basis, optimization problem (29) can be transformed into a convex optimization problem under McCormick relaxation, and this problem can be solved accurately and efficiently by commercial solvers such as CPLEX and Gurobi.

5. Case Study

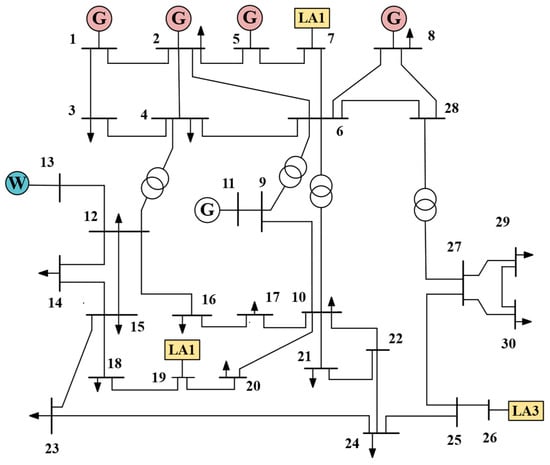

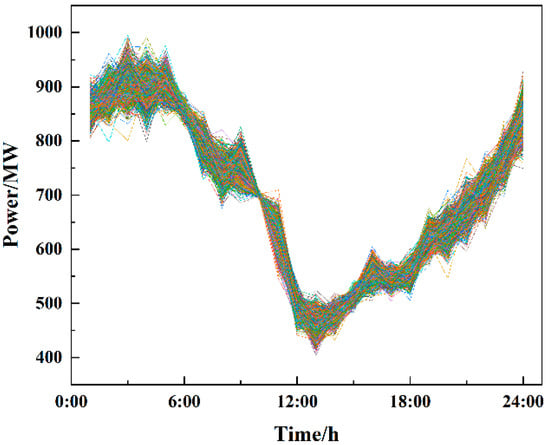

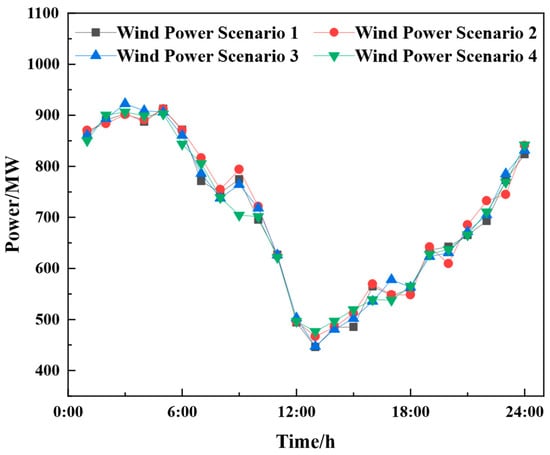

In this study, a modified IEEE 30-bus power grid is adopted as the test system, where generators 1 to 5 are set as coal-fired units with parameters listed in Table 2. A 1000 MW wind farm is integrated at Bus 13, replacing the original thermal generator. Three typical LAs (industrial LA (LA1), commercial LA (LA2), and residential LA (LA3)) are introduced at Buses 7, 19, and 26, respectively. The system topology is illustrated in Figure 4. For the wind output scenarios, 1000 samples are generated via Latin hypercube sampling—which is visualized in Figure 5—and four representative scenarios are extracted using the scenario reduction method [35]. The output curves from the scenarios are shown in Figure 6, with probabilities of 0.344, 0.230, 0.294, and 0.132, respectively. The cost coefficient for wind power generation, penalty coefficient for wind curtailment, and carbon emission coefficient are set to 60 CNY/MW, 250 CNY/MW, and 0.043 tCO2/MW [36], respectively. The electricity demand data are sourced from literature [37], and the TOU electricity prices are provided in Table 3. The carbon emission quota coefficient for electricity procurement of each LA is 0.728 tCO2/MW. The ladder carbon trading parameters include the following: baseline carbon trading price of 552 CNY/ton, incremental points for stepwise carbon prices of 10, 50, 100, and 500 t, and a price growth coefficient of 0.25. All electric vehicles (EVs) are assumed to be homogeneous with parameters in Table 4. LA1, LA2, and LA3 manage 500, 300, and 800 EVs, respectively. The contract parameters for TL and CL are summarized in Table 5. The SOC of the EV battery is constrained within the range of 10% ≤ SOC ≤ 90% to avoid over-charging/over-discharging. The initial SOC is set to 50%. The terminal SOC is also set to 50% to ensure consistency between the initial and terminal states. The charging efficiency of the EV battery is defined as 0.9, and the discharging efficiency is 0.85. This study adopts a 24 h dispatching cycle with a 1 h step (∆t = 1 h). All codes were executed on the MATLAB R2022b(MathWorks, Natick, Massachusetts, USA) simulation platform on a personal computer (PC) equipped with an Intel Core (TM) i5-11400H CPU @ 2.60 GHz, 32.00 GB RAM, and a GTX GeForce 3050Ti graphics card, and the mixed-integer programming (MIP) model was solved using Gurobi 9.5.

Table 2.

Parameters of thermal power generation units.

Figure 4.

Modified IEEE 30-bus system topology diagram.

Figure 5.

Wind power output scenario diagram simulated by the Latin hypercube method.

Figure 6.

Wind power output diagram after scenario reduction.

Table 3.

Parameters of TOU electricity prices.

Table 4.

Parameters of EVs.

Table 5.

Incentive contract parameters of flexible load.

5.1. Data-Driven Carbon Emission Flow Results

Since the true CEF values of the power system are unmeasurable in practice, the CEF results obtained via the traditional Newton−Raphson method (solving power flow equations iteratively) are defined as the benchmark values in this study, which are widely accepted as being closest to the unmeasurable true values, despite their inefficiency in real-time scenarios. The data-driven CEF model was trained using a dataset of 2592 labeled samples (70% for training and 30% for testing), where the “labels” refer to the benchmark CEF values from the traditional method (ensuring training targets are consistent with the high-accuracy reference).

For the IEEE 30-bus system, the traditional CEF method requires approximately 5 min for loop calculations, primarily due to its polynomial time complexity (O(N3), N = 30) from iterative power flow solutions and large-scale matrix inversions—this polynomial complexity becomes a bottleneck in dynamic scenarios, as calculations must repeat with updated generation/load variables. In contrast, the proposed data-driven model (based on multiple linear regression) is split into offline training and online inference: its offline parameter matrix solving (using 2592 labeled samples with a 70%/30% training/test split) completes within 10 s (time complexity O(M·K2), essentially linear with training sample size M since input variables K is a small constant). After training, it can achieve near-real-time CEF calculation (≤100 ms per iteration) via simple matrix−vector multiplication (linear time complexity O(N)), while maintaining alignment with the benchmark accuracy. This near-real-time performance meets the dynamic interaction requirements of the bi-level optimization framework, where carbon intensity signals need continuous updates during generation-demand side iterations.

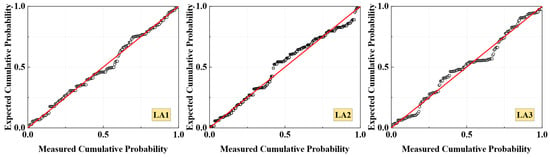

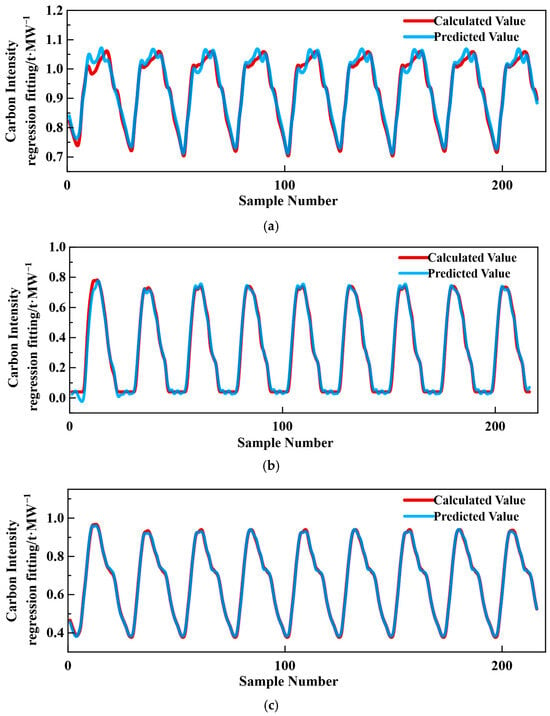

To evaluate the prediction accuracy of the proposed data-driven CEF model, error characteristic analysis was conducted on nodes 7, 19, and 26 (consistent with the LA-connected nodes in Figure 4), with the statistical results presented in Table 6. As shown in Table 6, all errors were calculated by comparing the data-driven predicted values against the traditional method’s benchmark values: the coefficient of determination (R2) for all nodes is as high as 0.969–0.998, indicating strong linear correlation between predicted and benchmark CEF values; the root mean square error (RMSE) is below 2.7 × 10−2 for all nodes, reflecting low overall prediction deviation; the mean square error (MSE) ranges from 7.03 × 10−5 to 6.92 × 10−4, quantifying minimal squared error; and the mean absolute error (MAE) does not exceed 2.10 × 10−2, confirming low average prediction bias.

Table 6.

Numerical analysis of regression for different LAs.

Complementary validation was performed using graphical analysis. As shown in the P-P plot (Figure 7), the cumulative probability distribution of the predicted data-driven values aligned closely with the 45° reference line (derived from the benchmark values). This verifies that the prediction error follows a normal distribution and the model has no systematic bias relative to the high-accuracy reference. In Figure 8, the data-driven predicted CEF values for nodes 7, 19, and 26 exhibit a high degree of overlap with the traditional method’s benchmark values across all test samples, further confirming the proposed model’s prediction performance.

Figure 7.

P-P plot of the regression model (the red line denotes the correspondence between expected and measured values in an ideal scenario, and the closer the data points are to the red line, the higher the prediction accuracy).

Figure 8.

Comparison of nodal carbon emission intensity: data-driven CEF method (predicted value) vs. traditional CEF method (calculated value). (a) Carbon emission intensity of node 7; (b) Carbon emission intensity of node 19; (c) Carbon emission intensity of node 26.

Collectively, the data-driven CEF model not only achieves high accuracy comparable to the traditional benchmark but also demonstrates remarkable computational efficiency with near-real-time calculation capabilities, meeting the precision requirements for a low-carbon dispatch model.

5.2. Results Analysis of Bi-Level Model vs. Traditional Two-Stage Model

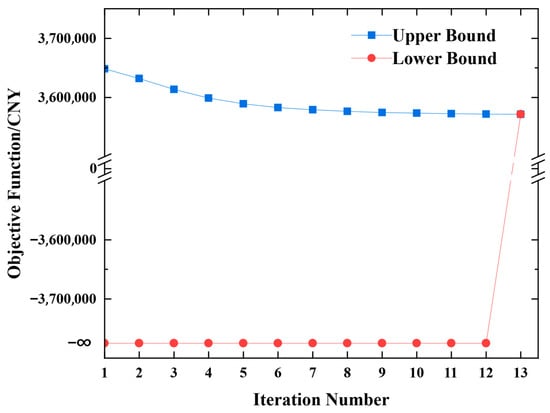

Figure 9 depicts the convergence trajectory of the bi-level mixed-integer programming model obtained by the sample-based algorithm. Specifically, the upper-bound objective value decreases monotonically from an initial value of 3.64 × 106 CNY, stabilizing at the 6th iteration. Convergence is achieved at the 13th iteration when the relative gap drops below 0.01% (meeting the preset tolerance), as shown by the alignment of upper- and lower-bound objective functions. Notably, the lower bound remains at negative infinity before the 13th iteration due to the infeasibility of lower-level subproblems, highlighting the critical role of sample enrichment in generating bi-level feasible solutions.

Figure 9.

Iteration performance of the sample-based optimization algorithm.

Table 7 lists the comparison analysis for convergence results obtained by the sample-based bi-level optimal algorithm and the bisection-based two-stage iterative method [38]. As shown in Table 7, the bisection method, affected by twofold coupling of TOU prices and dynamic nodal carbon intensity (updates with iteration), exhibits oscillatory convergence, requiring 15 iterations to achieve a 0.01 MW accuracy. In contrast, the proposed sample-based algorithm achieves a 21.6% reduction in iteration time and a 4.26% decrease in total cost.

Table 7.

Comparison of iteration results for sample-based bi-level method and bisection-based two-stage method.

Table 8 presents a comparison of the dispatching results between the sample-based bi-level optimization algorithm and the bisection-based two-stage iterative method. As shown, the sample-based bi-level optimization algorithm outperforms the traditional two-stage method significantly in both total dispatching cost and carbon emission cost. For the three LAs collectively, the total cost decreases from 370.36 to 357.05, marking a 3.59% reduction; total carbon emissions drop from 3953.41 to 3803.37, a 3.80% decrease; and notably, the total carbon trading cost plummets from 27.07 to 12.65, achieving a substantial 53.27% reduction—highlighting the remarkable cost-efficiency in the carbon trading phase. At the individual LA level, LA2 sees the most dramatic total cost cut, with an 8.99% reduction (from 50.53 to 45.98), while LA1 and LA3 also register cost reductions of 3.03% and 0.04%, respectively. Carbon emissions for LA1, LA2, and LA3 are reduced by 3.24%, 8.67%, and 1.11%, respectively. In carbon trading, LA1, LA2, and LA3 achieve cost reductions of 14.39%, 11.01%, and 55.61%, respectively, further underscoring the algorithm’s effectiveness across different LAs in carbon trading optimization.

Table 8.

Comparison of dispatching results between the bi-level optimization algorithm and the two-stage method.

This superior performance stems from the dynamic cutting plane’s continuous refinement of the upper-level feasible region, which tightly couples the lower-level carbon emission and trading strategies with the upper-level dispatching scheme. Consequently, a smoother convergence process is attained, and more optimal resource allocation is achieved at both the overall and node-specific levels, ultimately yielding a more refined and economically global optimal solution.

5.3. Analysis of Dispatching Results Under Various Scenarios

To comprehensively evaluate the superiority of the proposed model and algorithm, four scenarios are established for comparison in this study:

Scenario 0 (S0): Fixed electricity prices are considered, and loads do not participate in optimal dispatching;

Scenario 1 (S1): A two-layer optimal dispatching strategy is considered, where flexible loads are adjusted under the guidance of TOU electricity prices;

Scenario 2 (S2): A two-layer optimal dispatching strategy is considered, where flexible loads are adjusted under the guidance of fixed electricity prices and node carbon intensity;

Scenario 3 (S3): A two-layer optimal dispatching strategy is considered, where flexible loads are adjusted under the guidance of TOU electricity prices and node carbon intensity.

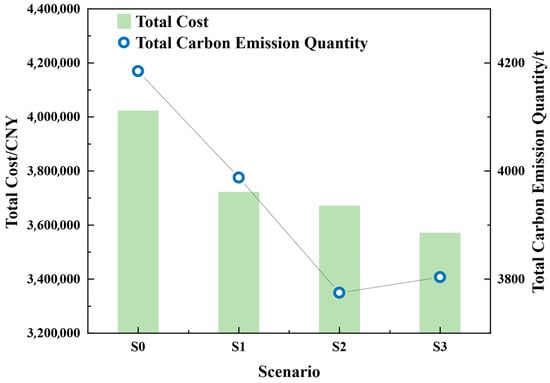

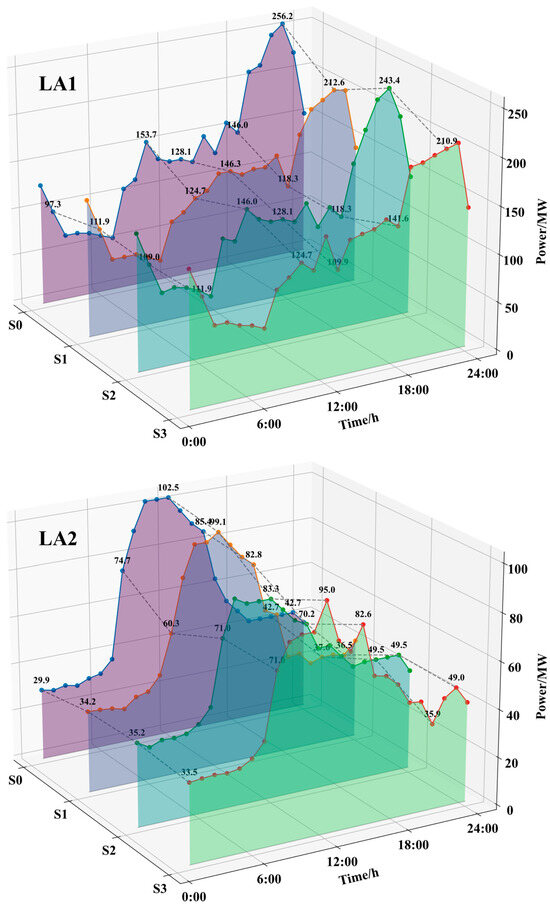

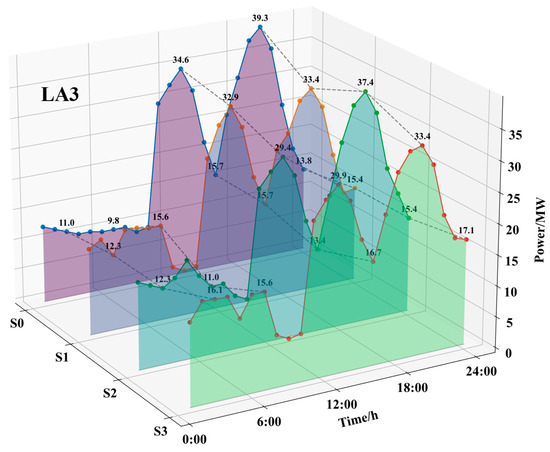

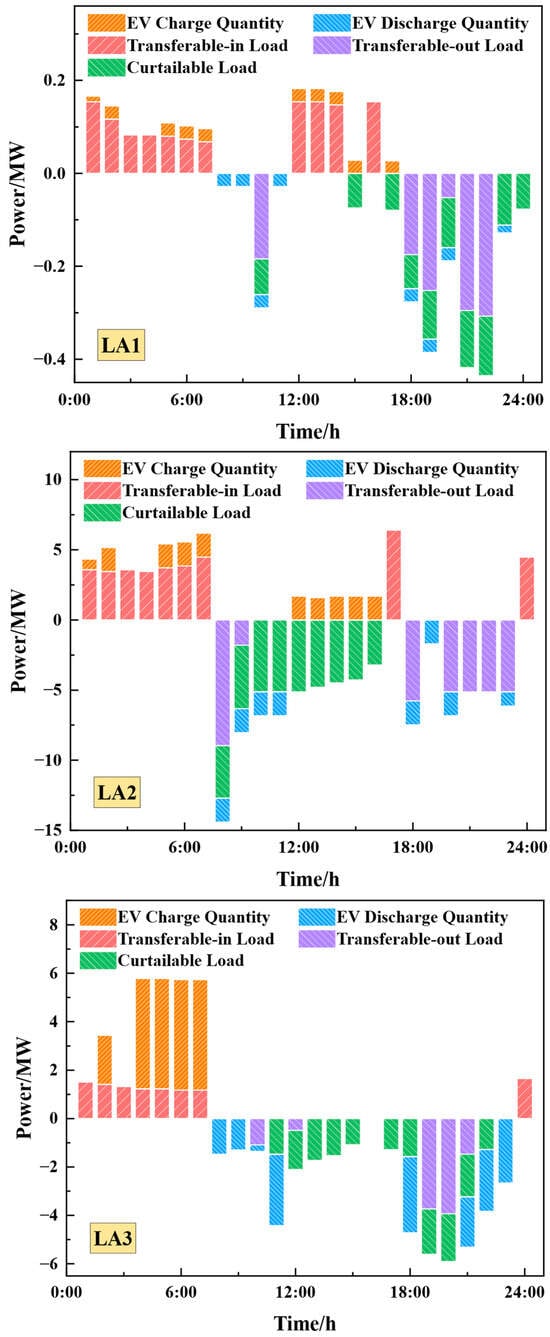

Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11 summarize the response results of each LA under different scenarios. Figure 10 compares carbon emissions and costs of each LA across the four scenarios, while Figure 11 illustrates the electricity procurement curves of each LA before and after load shifting.

Table 9.

Comparison of LA1 carbon emissions and costs in different scenarios.

Table 10.

Comparison of LA2 carbon emissions and costs in different scenarios.

Table 11.

Comparison of LA3 carbon emissions and costs in different scenarios.

Figure 10.

Total costs and total carbon emissions of LAs under various scenarios.

Figure 11.

24-h electricity purchase quantities of different LAs under various scenarios.

In S0, without the TOU electricity price demand response mechanism, LAs cannot shift flexible loads to low-electricity-price periods, causing electricity procurement costs to rise. For instance, LA1’s electricity purchase cost reaches 232.57 (×104 CNY), the highest among all scenarios. Meanwhile, the optimal dispatching ignores carbon trading costs, leading LAs to still purchase large amounts of electricity during high-carbon-intensity periods. For instance, LA1’s carbon emissions hit 3179.20 t, and its carbon trading cost is 71.26 (×104 CNY), both the highest in S0, resulting in the highest total operating cost (303.82 × 104 CNY for LA1).

After introducing the TOU electricity price demand response in S1, flexible loads can shift to low-electricity-price periods. Compared with S0, the peak-valley differences of LA1, LA2, and LA3 decreased by 53.16 MW, 6.87 MW, and 4.60 MW, respectively. The comprehensive cost at the three nodes decreased by 7.5%, and the total carbon emissions reduced by 4.7%. This confirms that electricity price signals can simultaneously improve the system’s economic efficiency and environmental friendliness, yet the potential of carbon trading remains to be fully unlocked—LA1’s carbon trading cost is still 67.33 (×104 CNY), far higher than in subsequent scenarios.

In S2, with stepwise carbon trading costs introduced under fixed electricity prices, the demand response mechanism guided flexible loads to shift to low-carbon-intensity periods to reduce carbon trading costs. Compared with S1, the total costs of LA1, LA2, and LA3 decreased by 1.03%, 7.48%, and 5.94%, respectively, while their carbon emissions reduced by 3.63%, 16.92%, and 14.34%, respectively. Notably, LA3 achieved net carbon trading profit, and LA1 and LA2 also obtained the highest net carbon trading profit among all scenarios, showing full release of carbon trading potential. Although the electricity procurement cost of S2 increased slightly compared with that of S1, the significant reduction in carbon trading costs completely offset this difference, ultimately achieving synergistic optimization of total operating cost and carbon emissions.

In S3, after replacing fixed electricity prices with the TOU electricity price strategy, under the combined influence of electricity prices and node carbon intensity, each LA could dispatch more flexible loads during periods of both low electricity prices and low carbon intensity, further reducing electricity procurement costs and corresponding total costs. Compared with those of S2, the total carbon emissions of S3 increased slightly, but the reduction in total cost was more significant, reaching 1.88%, 5.50%, and 5.92% for the respective LAs. Specifically, LA2 achieved an additional 5.5% cost reduction with a slight 2.9% increase in carbon emissions, reflecting its greater focus on economic optimization; LA3 became the only LA with continuous decreasing carbon emissions (to 336.59 t), indicating that the synergistic effect of TOU electricity prices and carbon intensity is most prominent in residential areas.

Compared with a single TOU electricity price or a single carbon intensity signal, the coupled strategy of “TOU electricity price and node carbon intensity” in S3 achieves synergistic optimization: It reduces electricity procurement costs through TOU electricity prices and suppresses high carbon emissions via carbon intensity signals. This provides a promotable hybrid strategy framework for the coordinated optimization of “economic efficiency-low carbon performance” in power systems.

5.4. Analysis of Dispatching Results in Scenario 3

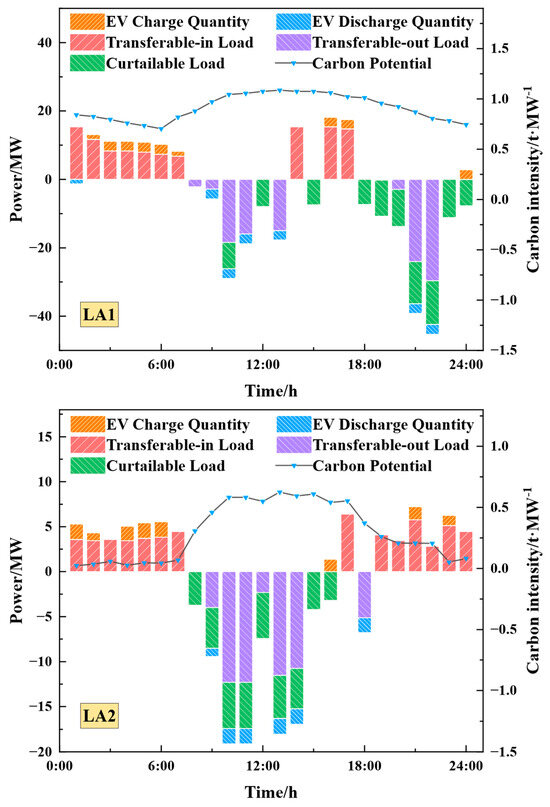

S3 comprehensively considers the combined influence of TOU electricity prices and node carbon intensity. The optimal demand response results of LA1, LA2, and LA3 are depicted in Figure 12 for comparative analysis, combined with the topology of the modified IEEE 30-bus system, revealing the following findings.

Figure 12.

Variation curve of flexible loads of each LA with respect to nodal carbon potential and TOU electricity price in S3.

LA2 is adjacent to the wind turbine connection at Bus 13. Given wind turbines’ near-zero carbon emissions and sufficient early-morning output to fully cover LA2’s load demand, the nodal carbon intensity at this node stays at the lowest level. However, during the daytime, declining wind power output forces coal-fired units to dominate power supply, raising nodal carbon intensity—resulting in the most significant volatility of LA2’s node carbon intensity. In contrast, LA1 is near a coal-fired power unit cluster with minor differences in emission coefficients, leading to relatively stable nodal carbon intensity variation.

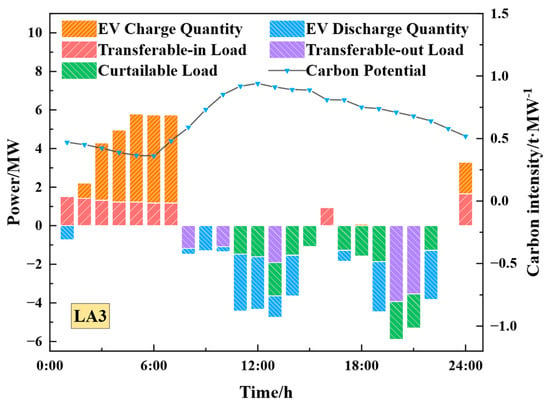

Figure 13 presents the demand response results of each LA in S1. By comparing the response characteristics of Figure 12 and Figure 13, the specific impact mechanism of nodal carbon intensity on demand response can be clarified, with the analysis as follows:

Figure 13.

Variation curve of flexible loads of each LA with respect to TOU electricity price in S1.

Low electricity price period (23:00–07:00): TOU electricity prices drive a large amount of load to shift to this period, and electric vehicle (EV) charging activities are also mainly concentrated here. In S1, the EV charging of each LA lacks orderly dispatching. In S3, demand response is simultaneously regulated by nodal carbon intensity: during 00:00–02:00, high nodal carbon intensity causes a sharp drop in EV charging (even switching to discharging mode in some intervals); during 03:00–07:00, as the carbon intensity gradually decreases, the EV charging synchronously increases.

Flat electricity price period (12:00–17:00): In S1, LA1 shifts part of its load to this period; moreover, after discharging in the previous period, the EVs of LA1 and LA2 charge to store energy for arbitrage in the subsequent high electricity price period. In S3, despite medium electricity prices, generally high nodal carbon intensity makes load curtailment and shifting the main responses in most periods. Only LA1 exhibits small-scale load shifting-in and slight EV charging at 14:00, 16:00, and 17:00 (when the carbon intensity is relatively low).

High electricity price periods (08:00–11:00 and 18:00–23:00): Electricity price signals become the dominant driving force for demand response. In S1, high electricity prices prompt each LA to shift out load and reduce procurement via EV discharging. In S3, although the nodal carbon intensity is low in some periods, high electricity costs outweigh carbon trading costs, so the response behavior remains price-driven. Notably, LA2 exhibits significant load shifting-in during 19:00–23:00; nighttime wind power output surges, dropping nodal carbon intensity from 0.61 to nearly zero, and the sharp decrease in carbon cost incentivizes load shifting-in. Moreover, in the same high electricity price period, the higher the nodal carbon intensity, the greater the load shifting-out, curtailment, and EV discharging volumes of each LA. These results confirm that demand response is regulated not only by electricity prices but also significantly driven by nodal carbon intensity.

It is worth noting that the proposed carbon-intensity-oriented DR framework also has ethical and social implications. By reshaping electricity consumption patterns through economic and carbon-based incentives, the framework may redistribute costs and comfort among different customer groups. Therefore, fairness considerations—especially for vulnerable or low-income consumers—should be taken into account when setting contract parameters and carbon-trading rules. In addition, the data-driven CEF model relies on metered load information at the aggregator level, which must be collected, stored and processed in compliance with data-privacy and cybersecurity regulations. These aspects are beyond the scope of the present study but are essential for any large-scale deployment of the proposed scheme.

This study also has several limitations that open up directions for future research. First, the proposed CEF regression model adopts a linear specification; while the numerical results show high accuracy for the IEEE 30-bus system under typical operating conditions, its extrapolation ability under extreme or highly nonlinear conditions may be limited. Extending the CEF surrogate to more expressive nonlinear or deep-learning models is a promising avenue. Second, the current framework assumes rational and centrally coordinated behavior of LAs and end-users, without explicitly modelling behavioral uncertainty or heterogeneity in comfort and risk preferences. Incorporating behavioral models and data-driven preference estimation would enable a more realistic representation of demand-side response. Third, the case studies are conducted on a modified IEEE 30-bus transmission-level system with a single carbon-trading mechanism. Future work will consider larger-scale distribution networks, integrated electricity−heat−gas energy systems, and multi-regional carbon markets to further validate the scalability and generality of the proposed approach, as well as its robustness to forecast errors and incomplete information.

6. Conclusions

This paper focuses on solving the low-carbon economic dispatch problem of power systems with DR, addressing the limitations of traditional generation-side-centric studies and the inefficiency of conventional CEF calculations. Key conclusions are drawn as follows:

- (1)

- The proposed data-driven CEF regression method effectively overcomes the defects of traditional CEF methods that rely on precomputed power flow and nonlinear matrix inversion. It establishes a direct mapping between measurable variables (generator output, load demand) and nodal carbon intensity, significantly reducing computational time while maintaining high prediction accuracy. Specifically, the method compresses the CEF calculation time from 5 min required by traditional approaches to less than 10 s, with the RMSE of nodal carbon intensity prediction kept below 2.7 × 10−2 tCO2/MW and the R2 reaching over 0.969. This enables real-time carbon intensity monitoring and seamless integration into the bi-level optimization framework, laying a foundation for dynamic interaction between source and load sides.

- (2)

- The bi-level dispatch model achieves effective coordination between grid operators and multi-type LAs (industrial, commercial, and residential). The upper layer optimizes generation and carbon trading costs, while the lower layer adjusts flexible loads (EVs, curtailable/transferable loads) based on twofold signals of TOU pricing and nodal carbon intensity. This fully activates the load-side decarbonization potential, breaking the one-sidedness of single-side optimization and realizing the balance of economic efficiency and low-carbon performance. Consequently, the bi-level scheduling model delivers synergistic benefits across three load aggregators, with a 3.59% reduction in total cost, a 3.80% cut in total carbon emissions, and a substantial 53.27% decrease in carbon trading costs.

- (3)

- The sample-based optimization algorithm outperforms the traditional two-stage method in convergence speed and solution accuracy. It avoids setting static power flow and carbon intensity, realizes simultaneous optimization of upper and lower objectives, and effectively handles nonlinear terms through linearization, ensuring the model’s solvability and optimality. In comparison with the conventional two-stage method, the proposed algorithm reduces the number of iterations by 2, shortens the iteration time by 21.6% and cuts the total scheduling cost by 4.26%, demonstrating its superior computational efficiency and economic viability.

- (4)

- Scenario comparisons confirm that the combined influence of TOU pricing and nodal carbon intensity is superior to single signals, achieving significant cost reduction while suppressing high emissions.

Overall, the proposed framework provides a practical and efficient approach for power system low-carbon operation, offering an important reference value for coordinating economic development and carbon emission reduction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L. (Wentian Lu); methodology, W.L. (Wenjie Liu); validation, W.L. (Wenjie Liu); resources, W.L. (Wentian Lu); data curation, Y.C.; writing—original draft, Y.C.; writing—review and editing, L.C.; supervision, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (grant number: 2022A1515240038).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Guangzhou University for providing laboratory facilities to support this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dogan, E.; Luni, T.; Majeed, M.T.; Tzeremes, P. The nexus between global carbon and renewable energy sources: A step towards sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 416, 137927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Du, E.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, C.; Zhang, N.; Liu, C. A review on carbon emission accounting approaches for the electricity power industry. Appl. Energy 2024, 359, 122681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Q.; Zhang, Y.F.; Jiang, H.D.; Liang, Q.M. Economy-wide assessment of achieving carbon neutrality in China’s power sector: A computable general equilibrium analysis. Renew. Energy 2023, 219, 119508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyong, C.K.; Reiner, D.M.; Ly, R.; Fajardy, M. Economic modelling of flexible carbon capture and storage in a decarbonised electricity system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 188, 113864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Yu, Y. Can renewable energy portfolio standards and carbon tax policies promote carbon emission reduction in China’s power industry? Energy Policy 2023, 174, 113461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.L.; Feng, T.T.; Kong, J.J. Can carbon trading policy and local public expenditures synergize to promote carbon emission reduction in the power industry? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 188, 106659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhang, P.; Yao, M.; Xue, M.; Miao, J.; Liu, B.; Wang, F. Multi-scope electricity-related carbon emissions accounting: A case study of Shanghai. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmjoo, A.; Kaigutha, L.G.; Rad, M.V.; Marzband, M.; Davarpanah, A.; Denai, M.J.R.E. A Technical analysis investigating energy sustainability utilizing reliable renewable energy sources to reduce CO2 emissions in a high potential area. Renew. Energy 2021, 164, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghali, M.; Osman, A.I.; Chen, Z.; Abdelhaleem, A.; Ihara, I.; Mohamed, I.M.; Yap, P.S.; Rooney, D.W. Social, environmental, and economic consequences of integrating renewable energies in the electricity sector: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1381–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Song, C.; Yuan, R. CO2 emissions from electricity generation in China during 1997–2040: The roles of energy transition and thermal power generation efficiency. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 773, 145026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhi, K.; Motlagh, M.S.; Dalir, F.; Perez, J.; Golzary, A. Towards sustainable electricity generation: Evaluating carbon footprint in waste-to-energy plants for environmental mitigation in Iran. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 2623–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtubia, B.; Sauma, E. Economic and environmental analysis of hydrogen production when complementing renewable energy generation with grid electricity. Appl. Energy 2021, 304, 117739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, Y.; Nie, L.; Huang, X.; Deng, Y.; Yan, J.; Kourkoumpas, D.S.; Karellas, S. Comparative life cycle greenhouse gas emissions assessment of battery energy storage technologies for grid applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 392, 136251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qays, M.O.; Kumar, R.; Ahmed, M.; Lachowicz, S.; Amin, U. Empowering Optimal Operations with Renewable Energy Solutions for Grid Connected Merredin WA Mining Sector. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari-Dibavar, A.; Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B.; Zare, K.; Khalili, T.; Bidram, A. Economic-emission dispatch problem in power systems with carbon capture power plants. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2021, 57, 3341–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Accelerating Decarbonization of the US Energy System; The National Academies Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.; Dong, J.; Liu, B.; Kuruganti, T. Decarbonizing the grid: Utilizing demand-side flexibility for carbon emission reduction through locational marginal emissions in distribution networks. Appl. Energy 2023, 330, 120303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşcıkaraoğlu, A.; Paterakis, N.G.; Erdinç, O.; Catalao, J.P. Combining the flexibility from shared energy storage systems and DLC-based demand response of HVAC units for distribution system operation enhancement. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2018, 10, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Xue, M.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Deng, X.; Xu, T.; Liu, P.; Cui, R. Multi-objective economic dispatch of a microgrid considering electric vehicle and transferable load. Appl. Energy 2020, 262, 114489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Liu, Y. Research on multi-energy collaborative operation optimization of integrated energy system considering carbon trading and demand response. Energy 2023, 283, 129117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Dong, J.; Liu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, T. From peak shedding to low-carbon transitions: Customer psychological factors in demand response. Energy 2022, 238, 121667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Song, F.; Ma, Y.; Qi, C.; Huang, F.; Xing, J.; Zhang, F. Economic and efficient multi-objective operation optimization of integrated energy system considering electro-thermal demand response. Energy 2020, 205, 118022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleschutz, M.; Bohlayer, M.; Braun, M.; Henze, G.; Murphy, M.D. The effect of price-based demand response on carbon emissions in European electricity markets: The importance of adequate carbon prices. Appl. Energy 2021, 295, 117040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, S.; Yan, D.; Jiang, Y. Proposing a carbon emission responsibility allocation method with benchmark approach. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 213, 107971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, M.; Ward, H.; Steckel, J.C. Sharing responsibility for trade-related emissions based on economic benefits. Glob. Environ. Change 2021, 66, 102207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Qu, S.; Zheng, H.; Meng, J.; Mi, Z.; Chen, W.; Wei, Y.M. Allocating China’s CO2 emissions based on economic Welfare gains from environmental externalities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 7709–7720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, G.J.; Novan, K.; Jenn, A. Hourly accounting of carbon emissions from electricity consumption. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 044073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Qin, Z. Demand response model by locational marginal electricity–carbon price considering wind power uncertainty and energy storage systems. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Liu, J.; Zhao, J.; Qiu, J.; Mao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wen, F. Real-time corporate carbon footprint estimation methodology based on appliance identification. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 19, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Zhou, T.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Xia, Q.; Yan, H. Carbon emission flow from generation to demand: A network-based model. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2015, 6, 2386–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Tao, Y.; Zhao, J. Carbon-oriented operational planning in coupled electricity and emission trading markets. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 35, 3145–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Tao, Y. Optimal power scheduling using data-driven carbon emission flow modelling for carbon intensity control. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 37, 2894–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Xu, S.; Hu, B.; Tai, N.; Vafai, K. Modeling on Carbon Emission Flow in Micro Energy Grid Optimal Dispatching Considering Source-Load Coordination. Energy 2025, 333, 137305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Yuan, M.; Zou, Z.; Sun, Y. Low-carbon economic optimization scheduling in distributed energy systems considering carbon emission responsibility and demand response. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 169, 110768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; Chen, J.; Yu, P. Clustering analysis of typical scenarios of island power supply system by using cohesive hierarchical clustering based K-Means clustering method. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B.; Hu, H.; Tang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Lin, X.; Chen, Z. Low-Carbon Optimization Scheduling for Systems Considering Carbon Responsibility Allocation and Electric Vehicle Demand Response. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, E.; Opazo, H.; Garcia, L.; Bastard, P. Online reconfiguration considering variability demand: Applications to real networks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2004, 19, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, B.; Kang, C.; Xi, W.; Feng, M. Low-carbon operation of multiple energy systems based on energy-carbon integrated prices. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 11, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.