Process Intensification and Operational Parameter Optimization of Oil Agglomeration for Coal Slime Separation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

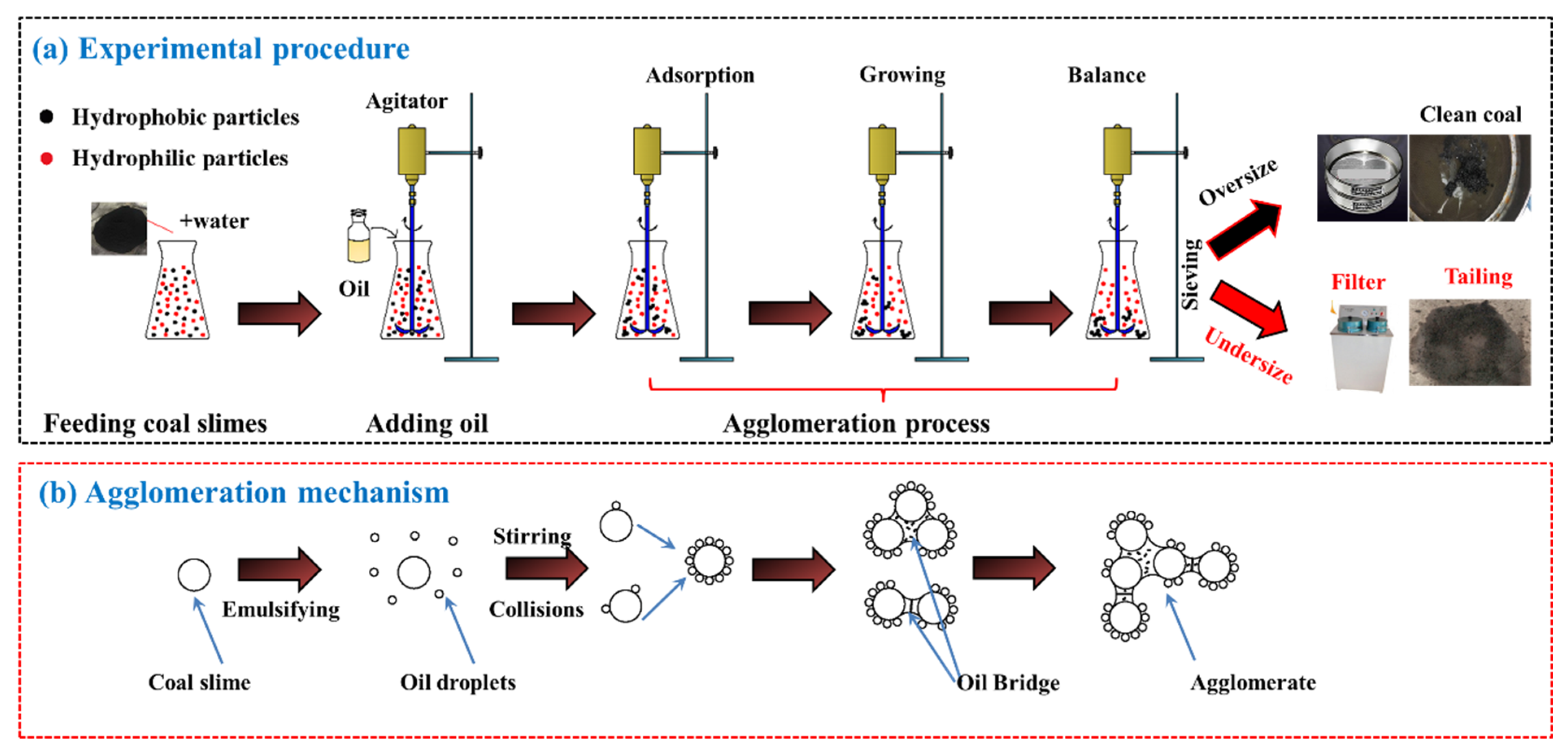

2.2. Experimental Procedure and Separation Mechanism

2.3. Experimental Indicators

3. Results and Discussion

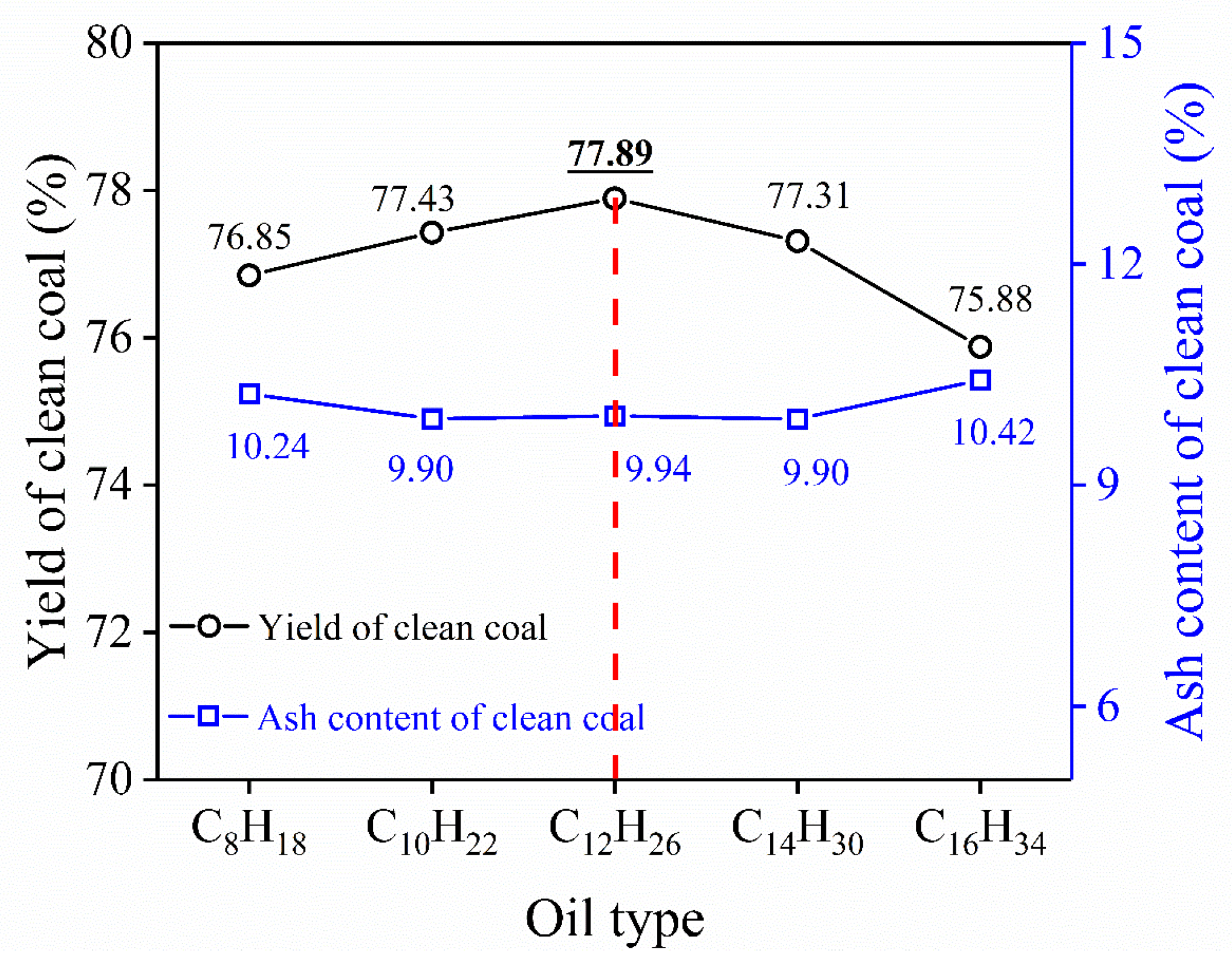

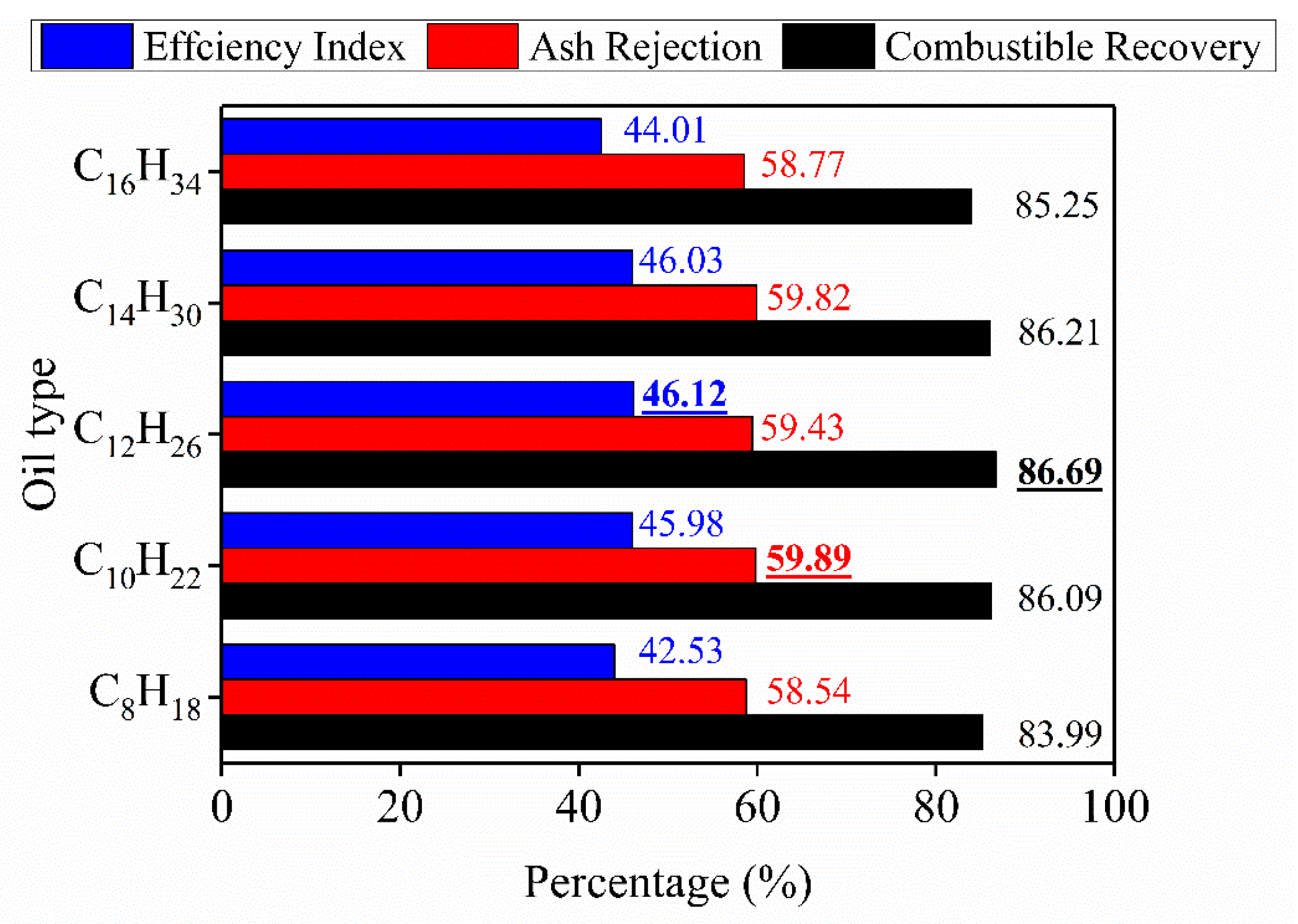

3.1. Effect of Oil Types with Different Carbon Chain Lengths

3.2. Effect of Pulp Density

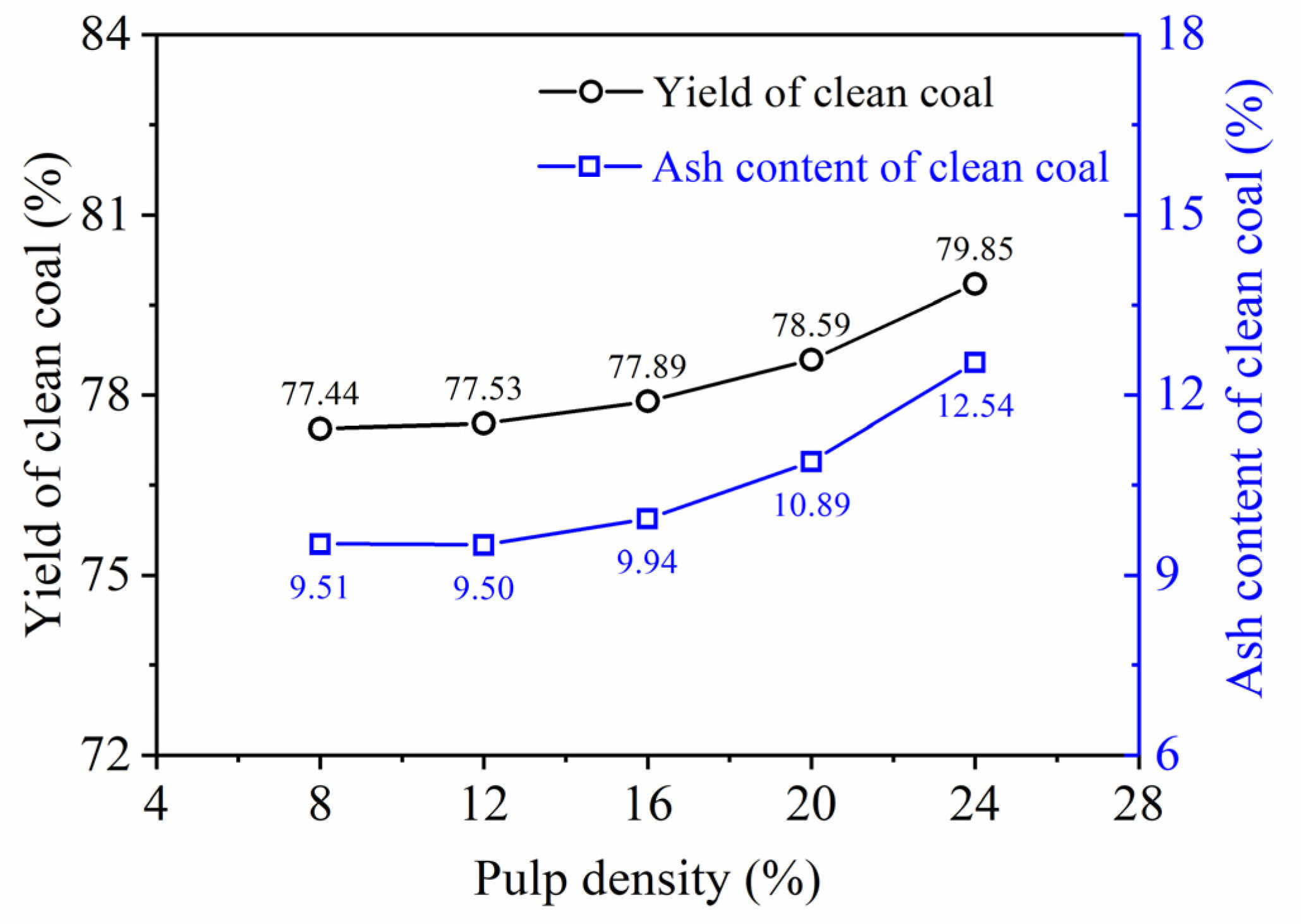

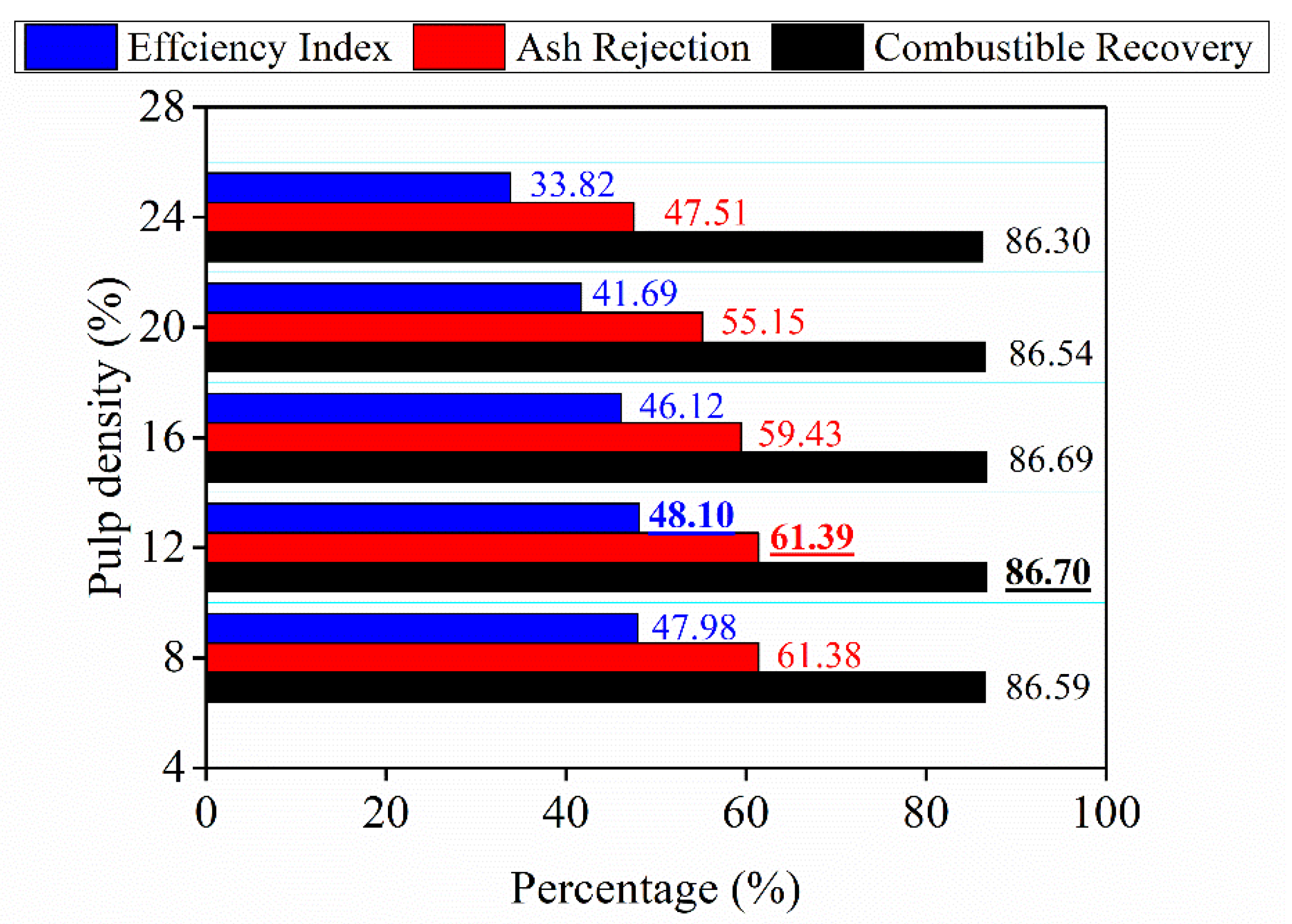

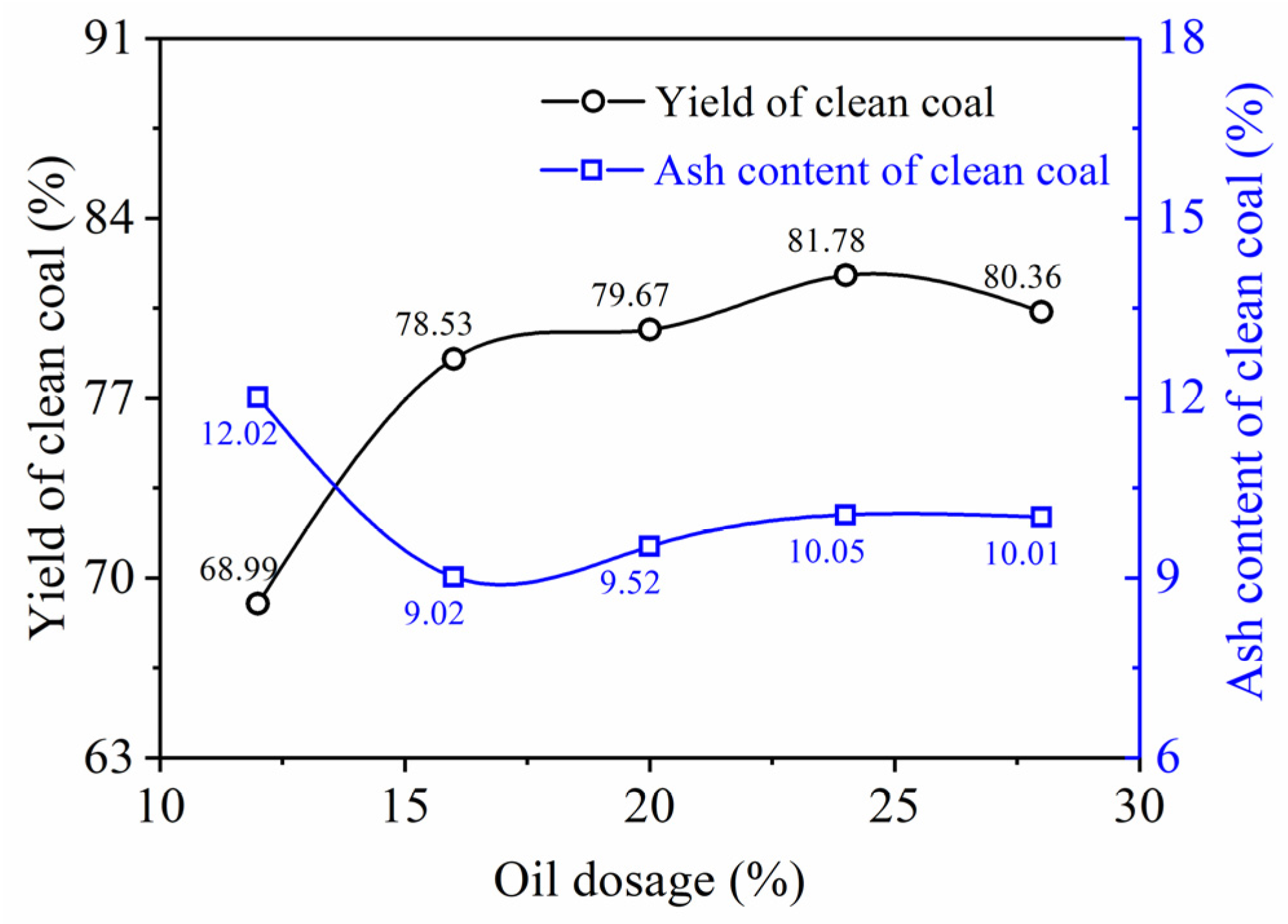

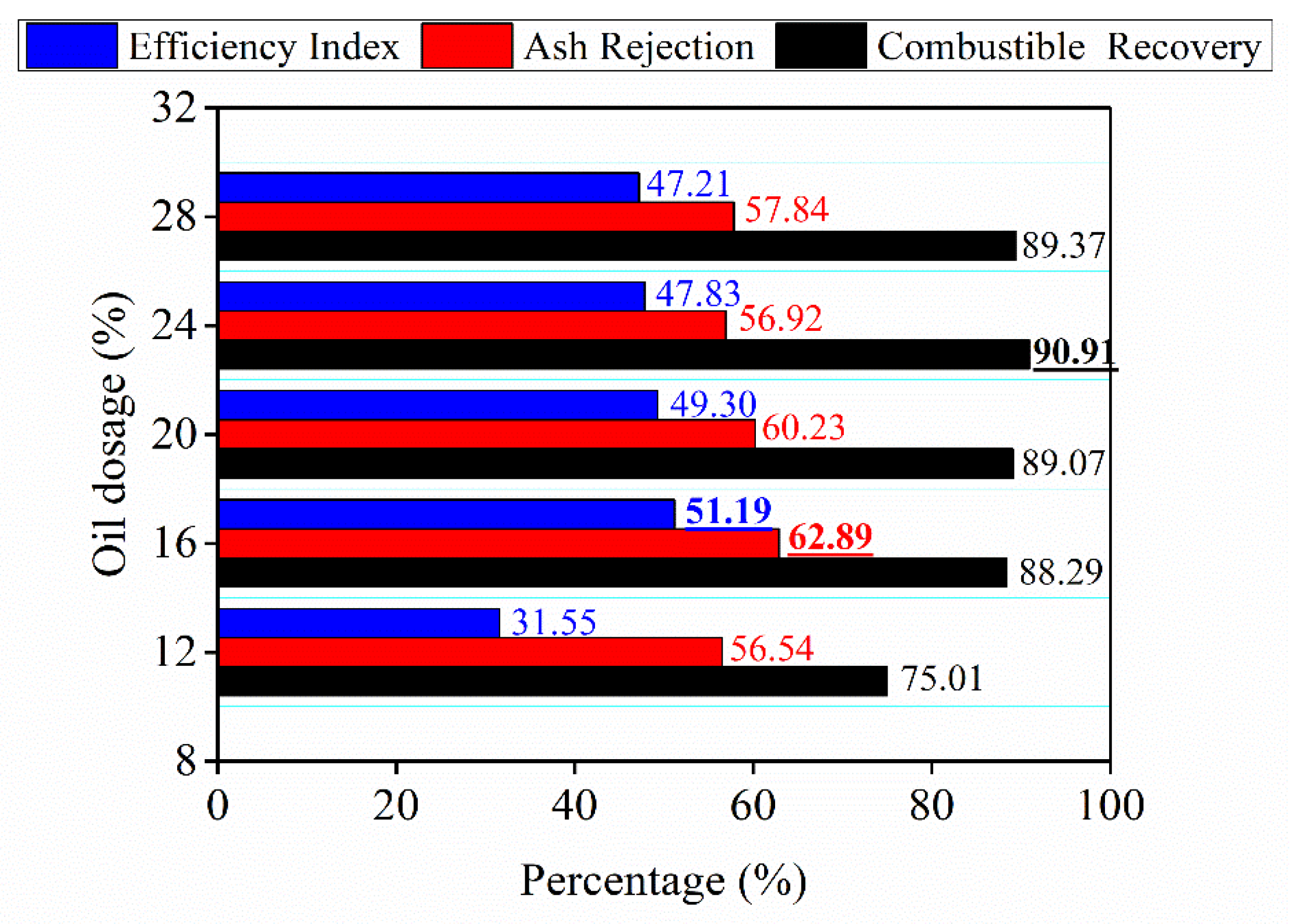

3.3. Effect of Oil Dosage

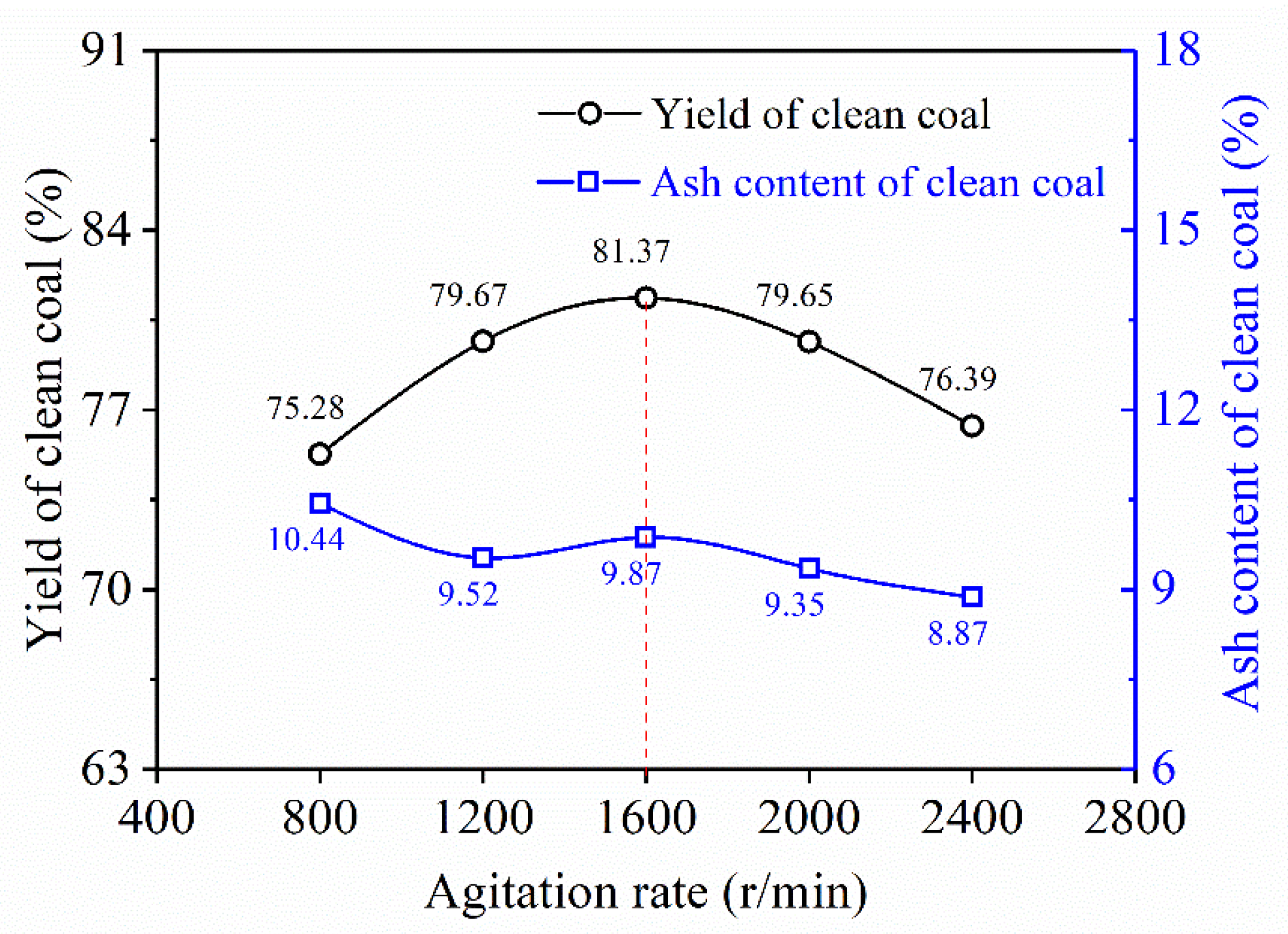

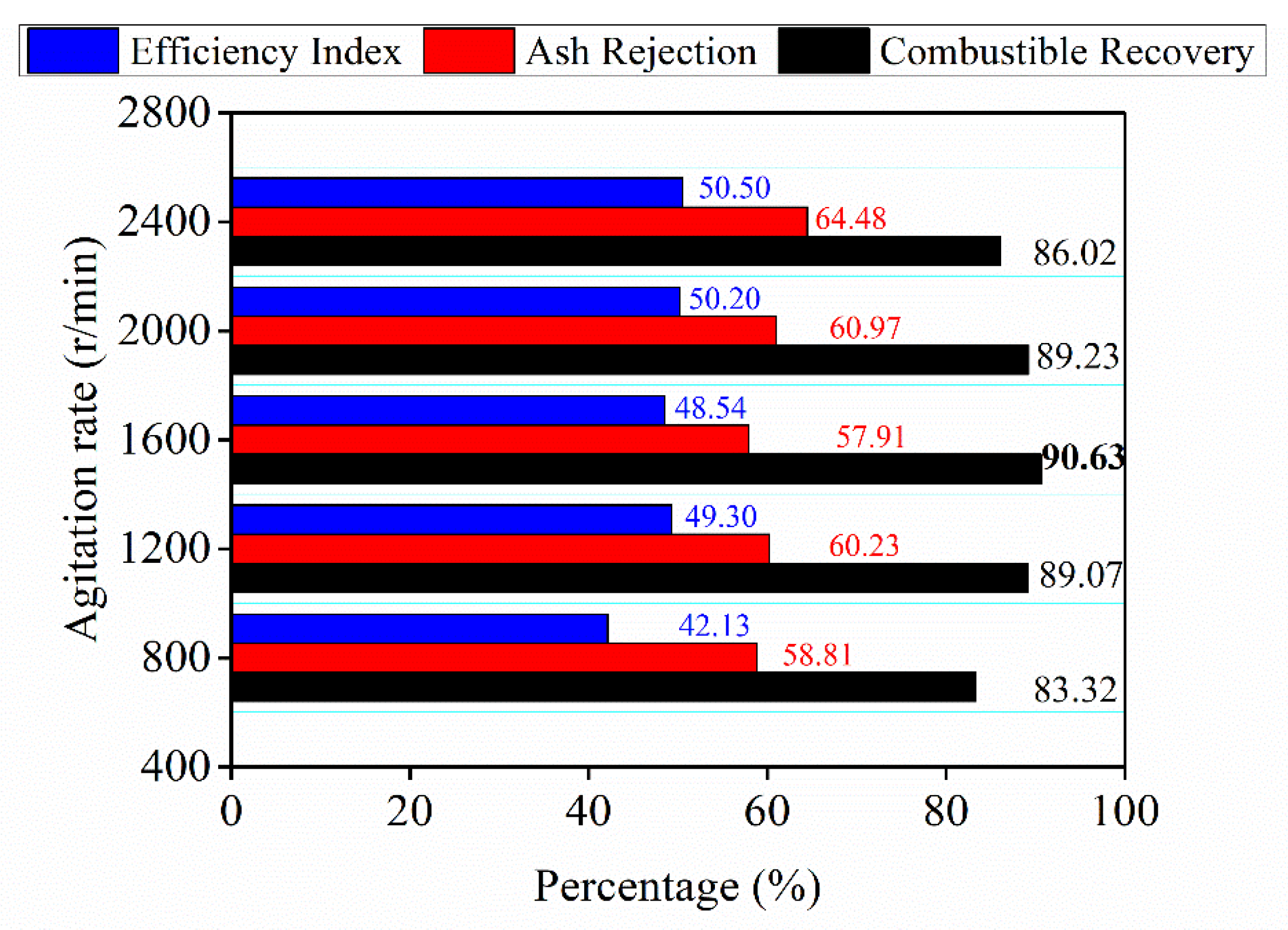

3.4. Effect of Agitation Rate

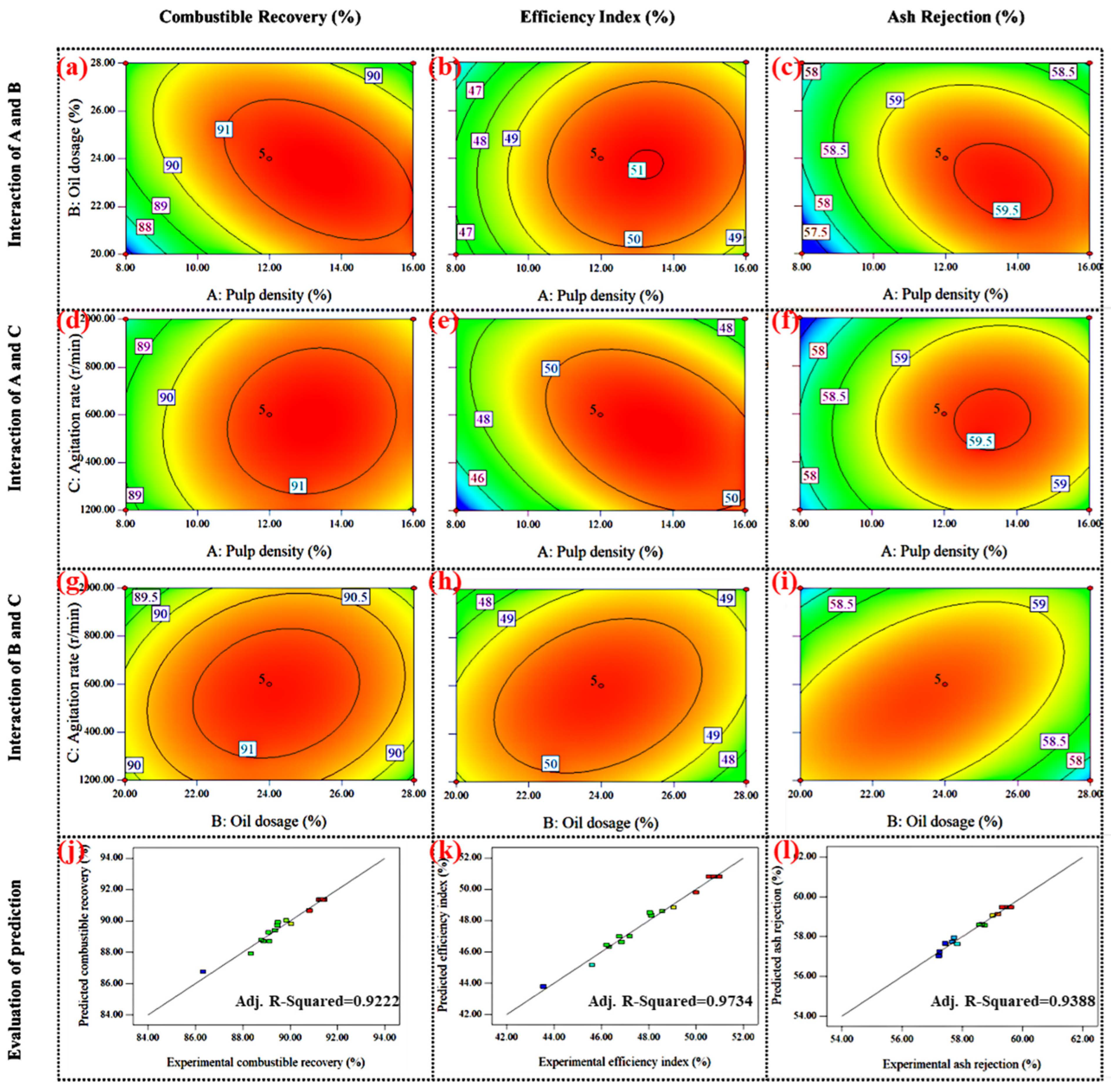

3.5. Interaction Effects and Optimization of Operational Conditions

- -

- Pulp density: 8% (−1), 12% (0), 16% (+1);

- -

- Oil dosage: 20% (−1), 24% (0), 28% (+1);

- -

- Agitation rate: 1200 r/min (−1), 1600 r/min (0), 2000 r/min (+1).

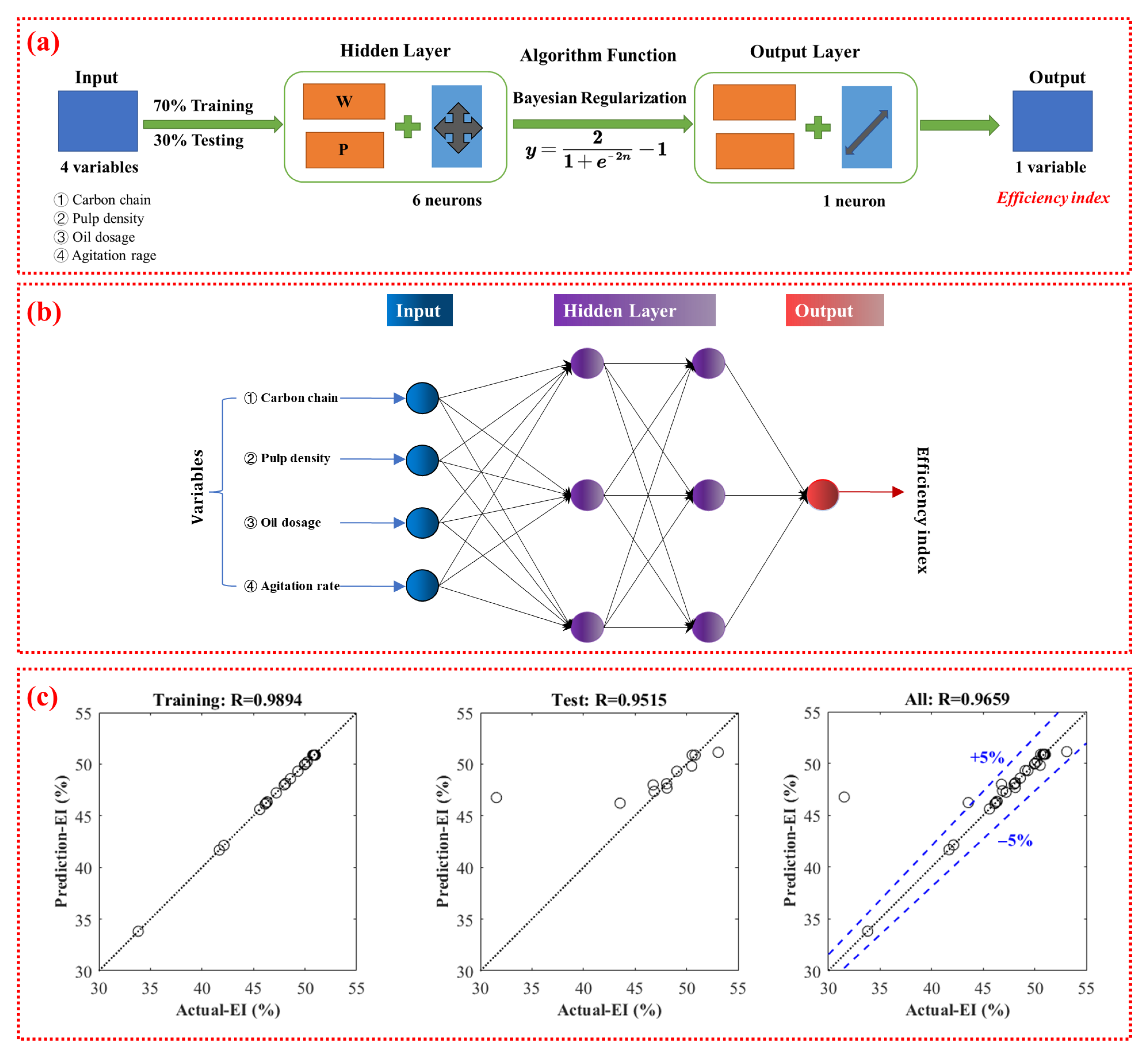

3.6. Prediction of the Efficiency Index of the Oil Agglomeration Based on Artificial Neural Network

- (1)

- Carbon chain length of the bridging liquid (ranging from 8 to 16 carbon atoms);

- (2)

- Pulp density (varying from 8% to 24%);

- (3)

- Oil dosage (spanning from 12% to 28%);

- (4)

- Agitation rate (covering 1200 to 2400 r/min).

- -

- Oil dosage showed the strongest positive correlation with the efficiency index (r = 0.78, p < 0.001);

- -

- Carbon chain length demonstrated strong positive correlation (r = 0.71, p < 0.001);

- -

- Agitation rate exhibited moderate positive correlation (r = 0.65, p < 0.01);

- -

- Pulp density displayed moderate negative correlation (r = −0.42, p < 0.05).

3.7. Process Intensification Implications of Coal Slime Oil Agglomeration

- (1)

- Throughput Enhancement: Optimizing pulp density to 14% (Section 3.5) increased processing capacity by 17% compared to the single-factor optimum (12% pulp density, Section 3.2) while maintaining ash rejection >59%. This aligns with PI principles by maximizing throughput without compromising selectivity.

- (2)

- Resource Minimization: The ANN-predicted oil dosage (22%) reduced bridging liquid consumption by 8.3% (Section 3.6) relative to the single-factor optimum (24%, Section 3.3), achieving comparable combustible recovery (91.49% vs. 90.91%). This demonstrates PI’s goal of reducing material inputs.

- (3)

- Energy Efficiency: Medium agitation rates (1600 r/min) minimized energy consumption, while preventing agglomerate breakage (Section 3.4). This provided optimal shear forces for oil–coal contact without turbulent dissipation, reducing the power usage by 15% compared to 2400 r/min.

- (4)

- Satisfactory Separation Performance: Under optimized conditions (14% pulp density and 22% oil), this work achieved 91.5% combustible recovery and 61.6% ash rejection with 22% oil dosage, outperforming Chary and Dastidar (2013) [11] (85.2%, 58.1%, and 28% oil). This 8.3% reduction in oil usage aligns with process intensification goal.

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Oil Selection Mechanism Elucidation: Through combined experimental and thermodynamic analysis, dodecane (C12H26) was identified as the optimal bridging liquid due to its intermediate carbon chain length that maximizes capillary pressure (ΔP = 2τcosθ/r) by achieving an optimal balance between interfacial tension and wettability. This fundamental understanding explains why shorter-chain oils (C8–C10) provide insufficient bridge strength despite good wetting characteristics, while longer-chain oils (C14–C16) exhibit poor spreading behavior that limits agglomeration efficiency. The thermodynamic equilibrium established by dodecane enhances selective agglomeration, yielding exceptional performance with a 91.49% combustible recovery and only 9.01% clean coal ash content.

- (2)

- Multi-Parameter Synergy Resolution: The Box–Behnken RSM optimization framework successfully resolved critical trade-offs between competing process objectives that have traditionally challenged single-factor optimization approaches. At the identified optimal conditions (α = 14%, β = 22%, and γ = 1600 r/min), the process intensification strategy achieved simultaneous improvements in multiple performance dimensions: processing capacity increased by 17% compared to single-factor optimum, oil consumption reduced by 8.3% while maintaining high combustible recovery, and ash rejection reached 61.58%. The desirability function approach provided a systematic methodology for balancing these competing objectives, demonstrating the practical advantage of multi-objective optimization in complex separation processes.

- (3)

- Advanced Predictive Modeling: The developed artificial neural network (ANN) model demonstrated robust predictive capability for the efficiency index (testing R2 = 0.9515 and RMSE = 1.12), effectively capturing the complex non-linear interactions between operational variables that conventional regression models cannot adequately represent. The model architecture optimization process identified a single hidden layer with six neurons as the optimal configuration, trained using Bayesian Regularization to ensure generalization capability. This ANN framework enables real-time process forecasting and control while potentially reducing experimental iterations by 40–60% in process optimization campaigns.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xia, W.; Xie, G.; Peng, Y. Recent advances in beneficiation for low rank coals. Powder Technol. 2015, 277, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.W.; Wheelock, T.D. Effects of pH and ionic strength on kinetics of oil agglomeration of fine coal. Miner. Eng. 1993, 6, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhu, L.; Liu, C.; Bai, Q. Optimization of the oil agglomeration for high-ash content coal slime based on design and analysis of response surface methodology (RSM). Fuel 2019, 254, 115560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chary, G.H.V.C.; Dastidar, M.G. Investigation of optimum conditions in coal–oil agglomeration using Taguchi experimental design. Fuel 2012, 98, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaşar, Ö.; Uslu, T.; Şahinoğlu, E. Fine coal recovery from washery tailings in Turkey by oil agglomeration. Powder Technol. 2018, 327, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.M.; Nikkam, S.; Gajbhiye, P.; Tyeb, M.H. Modeling and optimization of coal oil agglomeration using response surface methodology and artificial neural network approaches. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2017, 163, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, İ.; Erşan, M.G. Oil agglomeration of a lignite treated with microwave energy: Effect of particle size and bridging oil. Fuel Process. Technol. 2005, 87, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, B.J.; Kempton, A.G.; Coleman, R.D.; Capes, C.E. The effect of particle size and pH on the removal of pyrite from coal by conditioning with bacteria followed by oil agglomeration. Hydrometallurgy 1986, 15, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, V.; Sastry, K.; Morey, B. Review of oil agglomeration techniques for processing of fine coals. Int. J. Miner. Process. 1983, 11, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahinoglu, E.; Uslu, T. Effect of particle size on cleaning of high-sulphur fine coal by oil agglomeration. Fuel Process. Technol. 2014, 128, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chary, G.H.V.C.; Dastidar, M.G. Comprehensive study of process parameters affecting oil agglomeration using vegetable oils. Fuel 2013, 106, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünal, İ.; Aktaş, Z. Effect of various bridging liquids on coal fines agglomeration performance. Fuel Process. Technol. 2001, 69, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebeci, Y.; Eroglu, N. Determination of bridging liquid type in oil agglomeration of lignites. Fuel 1998, 77, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahinoglu, E.; Uslu, T. Amenability of Muzret bituminous coal to oil agglomeration. Energy Convers. Manag. 2008, 49, 3684–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Chen, B.; Chen, W.; Li, W.; Wu, S. Study on Clean Coal Technology with Oil Agglomeration in Fujian Province. Procedia Eng. 2012, 45, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebeci, Y.; Sönmez, İ. Application of the Box-Wilson experimental design method for the spherical oil agglomeration of coal. Fuel 2006, 85, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Chary, G.H.V.C.; Dastidar, M.G. Optimization studies on coal–oil agglomeration using Taguchi (L16) experimental design. Fuel 2015, 141, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.M.; Suresh, N. Statistical Optimization of Coal–Oil Agglomeration Using Response Surface Methodology. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 2016, 38, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalagli, N.; Gusella, V.; Liberotti, R. The role of shape irregularities on the lateral loads bearing capacity of circular masonry arches. In Proceedings of the Conference of the Italian Association of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics, Rome, Italy, 15–19 September 2019; pp. 2069–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Chang, H.; Xu, Y.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y. Applying artificial neural networks (ANNs) to solve solid waste-related issues: A critical review. Waste Manag. 2021, 124, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, A.T.; Nižetić, S.; Ong, H.C.; Tarelko, W.; Pham, V.V.; Le, T.H.; Chau, M.Q.; Nguyen, X.P. A review on application of artificial neural network (ANN) for performance and emission characteristics of diesel engine fueled with biodiesel-based fuels. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2021, 47, 101416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 211-2017; Determination of Moisture in Coal. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China, Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- ISO 1953:2015; Hard Coal-Size Analysis by Sieving. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Gürses, A.; Doymuş, K.; Doǧar, Ç.; Yalçin, M. Investigation of agglomeration rates of two Turkish lignites. Energy Convers. Manag. 2003, 44, 1247–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.; Ahmad, T.; Akhtar, J.; Shahzad, K.; Sheikh, N.; Munir, S. Agglomeration of Makarwal coal using soybean oil as agglomerant. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2016, 38, 3733–3739. [Google Scholar]

- Ken, B.S.; Nandi, B.K. Desulfurization of high sulfur Indian coal by oil agglomeration using Linseed oil. Powder Technol. 2019, 342, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, P.K.; Jayanthu, S.; Chakladar, S.; Chakravarty, S. An investigation into the effect of various parameters on oil agglomeration process of coal fines. Int. J. Coal Prep. Util. 2024, 44, 1039–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, O. Cleaning of fine asphaltite by oil agglomeration process. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2024, 46, 15189–15201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Moisture Content, Mad (%) | Ash Content, Aad (%) | Volatile Content, Vad (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 8.14 | 19.08 | 25.12 |

| Size Fraction (mm) | Yield (%) | Ash Content (%) |

|---|---|---|

| +0.5 | 0.14 | 14.54 |

| −0.5~+0.25 | 2.89 | 15.59 |

| −0.25~+0.125 | 17.68 | 16.80 |

| −0.125~+0.074 | 39.76 | 17.11 |

| −0.074~+0.045 | 28.87 | 19.44 |

| −0.045 | 10.66 | 30.24 |

| Total | 100.00 | 19.08 |

| Oil Name | Formula | Melting Point (°C) | Density at 25 °C (kg/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Octane | C8H18 | −57 | 703 (Liquid) |

| Decane | C10H22 | −30 | 730 (Liquid) |

| Dodecane | C12H26 | −10 | 749 (Liquid) |

| Tetradecane | C14H30 | 5.9 | 763 (Liquid) |

| Hexadecane | C16H34 | 18 | 773 (Liquid) |

| Parameters Considered | Parameters Varied During the Experiments | Parameters Kept Constant During the Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Oil type | Oil type: C8H18, C10H22, C12H26, C14H30, C16H34 | α: 12%, β: 16%, γ: 1200 r/min, |

| Pulp density (α) | Pulp density, α, (%): 8, 12, 16, 20, 24 | Oil type: C12H26, β: 16%, γ: 1200 r/min, |

| Oil dosage (β) | Oil dosage, β, (%): 12, 16, 20, 24, 28 | Oil type: C12H26, α: 12%, γ: 1200 r/min, |

| Agitation rate (γ) | Agitation rate, γ, (r/min): 1200, 1600, 2000, 2400 | Oil type: C12H26, α: 12%, β: 20%, |

| Order | A: Pulp Density, α (%) | B: Oil Dosage, β (%) | C: Agitation Rate, γ (kr/min) | Combustible Recovery (%) | Efficiency Index (%) | Ash Rejection (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 16.00 | 24.00 | 2.00 | 89.84 | 48.58 | 58.74 |

| 2 | 8.00 | 20.00 | 1.60 | 86.32 | 43.55 | 57.23 |

| 3 | 16.00 | 28.00 | 1.60 | 89.13 | 46.86 | 57.73 |

| 4 | 12.00 | 28.00 | 2.00 | 89.46 | 48.11 | 58.65 |

| 5 | 12.00 | 24.00 | 1.60 | 91.36 | 50.83 | 59.47 |

| 6 | 12.00 | 20.00 | 1.20 | 90.05 | 49.06 | 59.01 |

| 7 | 16.00 | 20.00 | 1.60 | 90.82 | 50.01 | 59.18 |

| 8 | 8.00 | 28.00 | 1.60 | 89.09 | 46.76 | 57.67 |

| 9 | 16.00 | 24.00 | 1.20 | 89.49 | 48.06 | 58.57 |

| 10 | 12.00 | 28.00 | 1.20 | 89.37 | 47.21 | 57.84 |

| 11 | 8.00 | 24.00 | 1.20 | 88.88 | 46.33 | 57.45 |

| 12 | 12.00 | 24.00 | 1.60 | 91.23 | 50.55 | 59.31 |

| 13 | 12.00 | 20.00 | 2.00 | 88.79 | 46.22 | 57.43 |

| 14 | 12.00 | 24.00 | 1.60 | 91.32 | 50.91 | 59.59 |

| 15 | 12.00 | 24.00 | 1.60 | 91.43 | 50.75 | 59.32 |

| 16 | 12.00 | 24.00 | 1.60 | 91.38 | 51.00 | 59.62 |

| 17 | 8.00 | 24.00 | 2.00 | 88.35 | 45.60 | 57.25 |

| Model | R2 (Testing) | RMSE |

|---|---|---|

| ANN (This work) | 0.9515 | 1.12 |

| Polynomial SVM | 0.9012 | 2.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, B.; Li, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhou, X.; Liu, C. Process Intensification and Operational Parameter Optimization of Oil Agglomeration for Coal Slime Separation. Processes 2026, 14, 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010126

Wu B, Li Y, Cao J, Zhou X, Liu C. Process Intensification and Operational Parameter Optimization of Oil Agglomeration for Coal Slime Separation. Processes. 2026; 14(1):126. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010126

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Bangchen, Yujie Li, Jinyu Cao, Xiuwen Zhou, and Chengguo Liu. 2026. "Process Intensification and Operational Parameter Optimization of Oil Agglomeration for Coal Slime Separation" Processes 14, no. 1: 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010126

APA StyleWu, B., Li, Y., Cao, J., Zhou, X., & Liu, C. (2026). Process Intensification and Operational Parameter Optimization of Oil Agglomeration for Coal Slime Separation. Processes, 14(1), 126. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr14010126