Abstract

Biogenic synthesis of gold nanoparticles using plant extracts has been widely explored for biomedical applications due to its eco-friendly and cost-effective nature. In this study, gold nanoparticles were phytoformulated using an ethanolic extract of dwarf copper leaf. Their physicochemical properties, antineoplastic activity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells, and bactericidal efficacy against selected pathogenic microorganisms were systematically evaluated. The phyto-synthesized AuNPs show potential as an antineoplastic agent, significantly dropping the viability of MCF-7 breast cancer cells when administered at higher concentrations. Comprehensive characterization revealed that the phyto-formulated AuNPs were predominantly spherical with sizes ranging from 15–38 nm as observed by TEM, while XRD analysis confirmed their crystalline nature. Furthermore, FT-IR analysis determined the plant extract’s functional groups, which served as both reducing and stabilizing agents during synthesis. Additionally, the phyto-formulated AuNPs showed bactericidal efficacy against several microorganisms, including Bacillus cereus, Salmonella typhimurium, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Serratia species. Particularly, the phyto-formulated AuNPs were effective against B. cereus and Serratia species. The present results showed that the phyto-formulated AuNPs could be used in biomedical contexts for bactericidal action and medication delivery. By using this cost-effective and eco-friendly nanobiotechnology method, AuNPs can enhance drug delivery and efficacy with lower toxicity effects associated with conventional chemotherapies.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent malignancies that affect women globally, especially in places where access to screening and treatment is limited. The World Health Organization (WHO) continues to address global breast cancer disparities through its Global Breast Cancer Initiative (GBCI), with intentions to decrease mortality by 2.5% per year over the next two decades, possibly saving 2.5 million lives by 2040 [1]. By 2022, breast cancer had killed 670,000 people worldwide. According to the most recent data available, 272,454 new cases of breast cancer in women were reported in the US in 2021, and 42,211 women lost their lives to the disease in 2022 [2]. In 2020, 10% of cancer-related fatalities and 13.5% of new cancer cases in India were attributed to mortality [3]. These results emphasize the necessity of developing novel, efficient, and secure treatment approaches for this illness. There is hope for better treatment options thanks to research on the causes of oncogenesis and developments in medical technology. Novel immunotherapies and tailored treatments are examples of emerging therapeutics that show promise for lowering the occurrence of breast cancer and improving patient outcomes [4].

Prioritizing prevention and treatment programs at the national and international levels is necessary to address inequities in cancer care and outcomes [5]. In oncology, standard treatment options like chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery are essential. Still, these therapies often have significant side effects and limitations, like the emergence of drug resistance, which lowers their overall effectiveness. Despite their widespread use, common chemotherapeutic drugs like cisplatin, paclitaxel, and gemcitabine often have toxicity and resistance mechanisms that reduce their effectiveness [6].

Nanotechnology provides revolutionary possibilities for cancer therapy, especially for medication delivery, in response to these difficulties. This area has the possibility to reduce the adverse effects of traditional chemotherapeutics while increasing their therapeutic index. Higher medication concentrations can be delivered directly to tumor locations using nanoscale carriers such liposomes, dendrimers, and polymeric nanoparticles, protecting healthy tissues and enhancing treatment results [7]. Drug resistance obstacles are also addressed via nanotechnology. By improving cellular absorption and avoiding efflux processes, surface modification of nanoparticles can increase therapy efficacy [8,9].

Several nano-pharmaceuticals, such as liposomal doxorubicin, paclitaxel formulations, and antibody–drug conjugates, have already demonstrated their improved solubility, prolonged circulation, and reduced adverse effects when compared with their conventional counterparts [10]. Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), in particular, are valued for their biocompatibility, stability, and multifunctional biomedical potential, including antimicrobial and antineoplastic activities [11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Green synthesis has gained increasing attention as an eco-friendly and cost-effective method for nanoparticle production, eliminating the need for toxic chemical reducing agents. Plant extracts contain diverse phytochemicals such as flavonoids, phenolics, alkaloids, saponins, and glycosides that can act as natural reducing and stabilizing molecules, making biogenic nanoparticle synthesis both sustainable and biologically advantageous [18].

The dwarf copperleaf plant (Alternanthera paronychioides) is known to contain a broad spectrum of bioactive compounds with reported antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, and anticancer properties [19,20]. However, its potential for phyto-mediated synthesis of AuNPs and the biological activities of such nanoparticles remain largely unexplored. While AuNPs synthesized from other Alternanthera species have been reported, the antineoplastic efficacy of AuNPs derived specifically from A. paronychioides against breast cancer cells is still not well established.

The present study aims to synthesize gold nanoparticles using A. paronychioides extract through a green bio reduction approach and to evaluate the bactericidal and antineoplastic properties of the resulting AuNPs. Comprehensive physicochemical characterization was conducted, and the biological activity of the synthesized nanoparticles was assessed using conventional antimicrobial and anticancer assays.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis Process

2.1.1. Preparation of Plant Extract

An ethanolic extract from a dwarf copper leaf plant (Alternanthera paronychioides A. St.-Hil.) was prepared as follows. One hundred grams of fresh plant leaves were gathered, completely cleaned to remove impurities by washing with distilled water, and air-dried at room temperature (22–25 °C) for 48 h. The dried leaves were ground into a fine powder using a mortar. The powder (10.0 g) was mixed with 500 mL absolute ethanol (10% w/v extraction ratio) and agitated on an orbital shaker at 150 rpm at at room temperature for 24 h. The extract was filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper. A clear greenish-brown extract rich in phenolic chemicals, flavonoids, and other biomolecules that acted as reducing and stabilizing agents was obtained when the solution was filtered to eliminate the solid residues [21]. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure in a rotary evaporator at 40 °C to yield a dry residue. The residue was redissolved in distilled water to prepare an aqueous stock extract of known concentration (10 mg/mL, w/v).

2.1.2. Synthesis of AuNPs

A 1.0 mM aqueous solution of gold (III) chloride trihydrate (HAuCl4·3H2O) was prepared fresh in deionized water. For the standard synthesis, 10 mL of HAuCl4 (1.0 mM) were mixed with 1.0 mL of aqueous plant extract stock 10 mg/mL, w/v), giving an extract-to-metal volume ratio of 1:10. The pH of the reaction mixture was adjusted to pH 7.0 using 0.1 M NaOH or 0.1 M HCl and verified with a calibrated pH meter. The mixture was stirred at 300 rpm at room temperature (22–25 °C) for up to 24 h. Color change from pale yellow to reddish–purple was typically observed within 60 min, indicating Au (III) reduction and nanoparticle formation [22]. After completion, the AuNP suspension was centrifuged at 12,000× g for 15 min and washed twice with deionized water to remove unbound phytochemicals. The suspension was freeze-dried using a laboratory lyophilizer (e.g., Labconco FreeZone® 4.5 L Benchtop Freeze Dryer, Labconco Corporation, Kansas, MO, USA) after freezing at −80 °C, until a dry powder was obtained. The gravimetric yield was determined by weighing the dried material, and the typical yield of AuNPs synthesized from Alternanthera paronychioides was 27 mg/100 mL. All essential experimental parameters (pH, reaction temperature, extract concentration, mixing conditions, and reaction times purification steps) were optimized by using standardized conditions for reproducibility (Table S4).

2.2. AuNP Characterization

The produced AuNPs were characterized by the following techniques:

2.2.1. UV-Vis Spectroscopy

UV-vis spectroscopy, a regularly used method for verifying nanoparticle production, was first used to analyze biogenically generated AuNPs. A U2900 spectrophotometer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) was used for the analysis, with a resolution of 1 nm and a wavelength range of 150–600 nm. The distinctive surface plasmon resonance (SPR) band, which is usually seen between 500 and 600 nm and indicates AuNP production, was used to validate the presence of AuNPs. The position of this SPR peak, which arises from the cooperative swinging of conduction electrons in response to light, can reveal information about the size, shape, and condition of particle aggregation [23,24,25,26].

2.2.2. TEM Analysis of Synthesized AuNPs

An essential method for assessing the size, shape, and distribution of nanoparticles is transmission electron microscopy (TEM–Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), which offers insights into their morphological properties and possible application efficacy. The AuNPs produced in this investigation utilizing the test plant’s ethanol extract were regularly seen using TEM. The production of evenly shaped AuNPs with distinct size distributions was verified by TEM images. The particle size distribution was determined by measuring the diameters of more than 100 individual nanoparticles from representative TEM micrographs using ImageJ software (verrsion 1.x, Wayne Rasband, NIH, WI, USA). The size range was calculated based on these measurements. These particles are crucial markers of the phytochemicals in the plant extract successfully reducing and stabilizing gold ions. Spherical forms are typical for green-synthesized AuNPs, while they can vary based on the synthesis circumstances and plant extract content [27,28]. Because of the stabilizing effect of the extract’s biomolecules, AuNPs generated from plants are usually spherical and range in size from 10 to 50 nm. These biomolecules are capping and reducing agents [29,30]. This capping layer, which is apparent in the TEM micrographs, is essential because it keeps the nanoparticles from aggregating and improves their stability, both of which are major benefits of green synthesis techniques. The observed size and shape coordinated the results of prior investigations, where TEM examination showed that green-synthesized AuNPs frequently exhibit extremely monodisperse properties, increasing their potential for catalytic and biological applications [31].

2.2.3. Zeta Potential Analysis

The active surface charges on the AuNPs were measured by using Zeta potential (Malvern Instruments Zetasizer, Worcestershire, UK). Zeta potential measurements of the green-synthesized AuNPs were performed at 25 ± 1 °C. Prior to measurement, lyophilized AuNPs were re-dispersed in deionized water to give a stock dispersion of 0.10 mg·mL−1 and probe-sonicated for 5 min (20% amplitude, pulse mode) to minimize aggregation. For electrophoretic mobility measurements, samples were diluted into a background electrolyte of 0.1 mM KCl (ionic strength ≈ 1 × 10−4 M) to ensure sufficient conductivity for reliable measurements while minimizing screening of surface charge. All measurements were performed in folded capillary cells at 25 °C. Each reported zeta potential value is the mean ± standard deviation of three independent measurements, each comprising 10 runs. Data were analyzed using the Smoluchowski approximation to convert electrophoretic mobility to zeta potential [32]. The solvent, background electrolyte, dispersion concentration, sonication/dispersion protocol, temperature, instrument model, number of runs, and analysis model are given in Table S5.

2.2.4. X-Ray Diffraction Study

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was conducted to confirm the crystalline structure and phase characteristics of AuNPs produced using the ethanol extract of a dwarf copper leaf plant. This method is crucial for confirming the crystallinity of nanoparticles since it gives details regarding the size, phase purity, and crystal structure. A fixed monochromator was used to obtain diffraction patterns, which improved the data’s clarity and resolution. The purity and grain size of the biogenic AuNPs were evaluated using the Shimadzu XRD machine (XRD-6000 Diffractometer-Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Kyoto, Japan) with Cu Ka radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) at 40 kV and 30 mA.

The face-centered cubic (FCC) structure of gold can be referenced to the XRD patterns, which usually show discrete peaks corresponding to crystal planes and are in good agreement with standard JCPDS data (JCPDS No. 04-0784). High crystallinity and the effective reduction of gold ions to generate AuNPs are indicated by the presence of sharp points. The usual crystallite size can also be assessed using the Scherrer equation resulting from the widths of the diffraction peaks. XRD analysis is a dependable technique for confirming the effective synthesis of nanoparticles, additionally supporting the effectiveness of green synthesis approaches by employing plant extracts [25,30]. Furthermore, XRD outcomes are vital for considering the properties of AuNPs, as their dimensions and crystallinity can affect their electrical, optical, and catalytic properties, customizing them for diverse applications in biomedicine, electronics and environmental bioremediation [33,34].

2.2.5. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) Analysis

The presence of functional groups in the synthesized AuNPs made from plant extracts was examined using FT-IR. Finding the organic molecules that are crucial to the reduction and stability of nanoparticles during green synthesis requires the use of this analytical method. A Perkin Elmer FT-IR Spectroscopy C100599 instrument (Waltham, MA, USA) operating at a resolution of 0.4 cm−1 throughout a range of 4000–400 cm−1 was used to perform FT-IR analysis on dried pellets of the produced AuNPs. An abundance of information on the chemical vibrations connected to particular functional groups can be obtained from FT-IR spectra. Several functional groups, including hydroxyl (–OH), carbonyl (C=O), and amine (–NH) groups, which are frequently found in phytochemicals present in plant extracts used for synthesis, are indicated by the typical peaks seen in the FT-IR spectrum. Peaks about 1620 cm−1 frequently indicate C=O stretching, whereas those around 3400 cm−1 may correspond to O–H extending vibrations [35,36]. Finding these functional groups is important because they not only help reduce gold ions to AuNPs but also stabilize the nanoparticles by keeping them from aggregating. These groups highlight the produced AuNPs’ biocompatibility and prospective biological uses, especially in drug transport and bactericidal activities [37,38].

2.3. Cytotoxicity of the Synthesized AuNPs

AuNP suspensions were sterilized by filtration using a 0.22 µm syringe filter (HiMedia, Mumbai, India). All treatments were prepared under aseptic conditions inside a laminar flow hood. No autoclaving or heat treatment was used to avoid altering nanoparticle properties. A stock solution of the synthesized AuNPs was prepared in sterile distilled water. Serial dilutions were made from this stock to achieve the desired concentrations (ranging from 20 to 100 µg/mL) for treatment. These dilutions were freshly prepared and added directly to the culture medium in each well for MTT assay. The concentrations were calculated based on the dry weight of the nanoparticles obtained after lyophilization and were quantified gravimetrically (27 mg of AuNPs from 100 mL of the reaction mixture). This ensured the accuracy and reproducibility of the dosage in the biological evaluations.

The cytotoxicity of AuNPs synthesized from a dwarf copper leaf plant ethanolic extract was assessed using the MTT assay on both normal VERO cells (kidney epithelial cells from African green monkeys) and the breast cancer cell line MCF-7. The cell lines used in this study was obtained from the National Centre for Cell Sciences (NCCS), Pune, India. Cells were plated in 96-well microplates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h, allowing them to reach approximately 80% confluence.

Following the incubation period, the culture medium was exchanged, and the cells were exposed to varying concentrations of the synthesized AuNPs (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/mL) for another 24 h (48 h in total). After treatment, the cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline PBS (pH 7.4) to eliminate the released nanoparticles. Next, 20 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL in PBS) were introduced to each well, and the plates were incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 2 h [39]. Viable cells converted MTT into formazan crystals, which were subsequently dissolved in 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide. Absorbance of the resulting solution was measured spectrophotometrically at 570 nm [40].

The capability of AuNPs to persuade cytotoxicity in cancer cells while sparing normal cells highlights their possibility as antineoplastic agents for cancer treatment [41,42]. The use of Vero cells alongside MCF-7 cells allowed assessment of nanoparticle cytotoxic selectivity, thereby distinguishing anticancer effects from nonspecific toxicity.

2.4. Inverted Light Microscopy

Sub-cultured flasks containing uncontaminated MCF-7 cells were examined under an inverted light microscope to assess their morphological features, which served as controls. The medium was detached, and the cells were treated with the IC50 concentration of AuNPs, followed by incubation for 48 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After the incubation, the flasks were observed under an inverted light microscope. Cells were classified as apoptotic if they exhibited characteristics such as cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, decreased cell density, or nuclear destruction [43].

2.5. Bactericidal Activity of AuNPs Synthesized from Plant Extract

The bactericidal activity of green produced AuNPs was determined using the agar well diffusion method, which provides qualitative inhibition patterns. All antimicrobial assays were performed in triplicate (n = 3). This was carried out by taking the synthesized AuNPs in different concentrations (0.01 mg/mL, 0.02 mg/mL, 0.03 mg/mL, 0.04 mg/mL, 0.05 mg/mL, 0.1 mg/mL, 0.15 mg/mL, 0.2 mg/mL) and reconstituting them with sterile water. Additional positive (tetracycline: 5 µg/mL) and negative (sterile water) controls were tested along with the test samples. Four pathogenic bacterial strains were used in the present study. Bacillus cereus (MTCC 7350) (Gram-positive), Staphylococcus epidermidis (MTCC 3615) (Gram-positive), Serratia species (MTCC 8708) (Gram-negative), and Salmonella typhimurium (MTCC 3224) (Gram-negative) were attained from the Microbial Type culture collection (MTCC), Institute of Microbial Technology (IMTECH), Chandigarh, India. The diameters of the inhibitory zones were measured in centimeters using a measuring scale [44].

2.6. Statistical Tests

The results were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test (p < 0.05 considered statistically significant).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of AuNPs

An ethanolic extract of a dwarf copper leaf plant was made by mixing 500 mL of ethanol with 100 mg of leaves (Figure S1). The leaf extract was added to the HAuCl4 in a 1:9 ratio to carry out the amalgamation of AuNPs. After 24 h of incubation, the plant extract mixture’s color altered. Visual proof of the color shift from the original green to the brunette hue was recorded (Figure S2). The dry weight of AuNPs nanoparticles obtained after centrifugation and lyophilization was measured. On average, ~27 mg of AuNPs were recovered from 100 mL of the reaction mixture after centrifugation and lyophilization, indicating efficient conversion of the gold precursor into nanoparticle form.

Plant extracts, rich in a variety of metabolites and organic compounds such as alkaloids, flavonoids, proteins, polysaccharides, cellulose, and phenolic compounds, serve as versatile media for NP synthesis [45]. These metabolites facilitate the bio-reduction of metallic ions into nanoparticles while also acting as stabilizing agents [46]. Proteins within plant extracts, particularly those containing amino functionality (–NH2), actively participate in the reduction of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), playing a dual role in reduction and stabilization [47]. Furthermore, phytonutrients such as flavones, alkaloids, phenols, and anthracenes provide functional groups (e.g., –C–O–C–, –C–O–, –C=C–, and –C=O–) that contribute to the formation of AuNPs without requiring additional capping agents, as these natural compounds inherently replace toxic reducing agents like NaBH4 [48].

The bio-reduction mechanism underlying this process involves the conversion of metal ions from their mono- or divalent states to a zero-valent metallic state, then the nucleation of the reduced metal atoms takes place [49]. This environmentally friendly synthesis method, typically performed as a one-pot, single-step reaction, reduces Au3+ ions to Au0, achieving nanoparticle formation within minutes to hours [50].

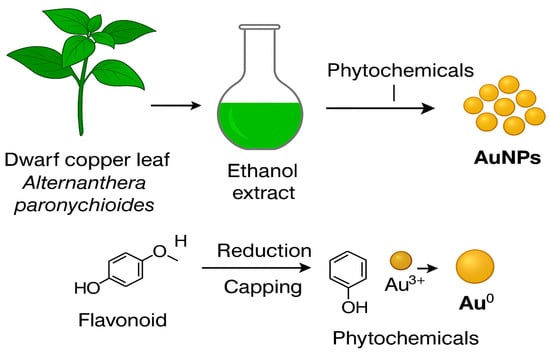

By blending the HAuCl4 solution with the leaf extract, phytonutrients present in the plant extract both act as reducing agents, converting Au3+ to Au0 (Figure 1), and stabilize the nanoparticles by providing steric and electrostatic repulsion and stopping aggregation [51,52]. The reduction and steadiness processes are enabled by heating the reaction mixture to around 60 °C, which advances the reduction rate and improves the creation of consistently sized nanoparticles [53]. In a previous study, it was reported that AuNPs synthesized through the reduction of tetrachloroauric acid (HAuCl4) using trisodium citrate dihydrate in water underwent a multi-step chemical reaction. During this multistep chemical reaction, trisodium citrate dihydrate is oxidized to produce dicarboxyacetone as an intermediate. This reaction facilitates the reduction of aurous species to gold nuclei, with dicarboxyacetone acting as both the reducing and nucleating agent. As dicarboxyacetone decomposes into acetone, Au nuclei are formed and subsequently grow by interacting with other Au NPs, leading to an upsurge in particle size [54].

Figure 1.

Proposed schematic illustration of the green synthesis mechanism of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) using ethanol extract of Alternanthera paronychioides. Phytochemicals such as flavonoids, phenolics, and terpenoids participate in (i) reduction of Au3+ to Au0 and (ii) capping/stabilization of the resulting nanoparticles. This conceptual diagram summarizes the general mechanism reported in the literature and supports the interpretation of the synthesis process.

3.2. Characterization of AuNPs

3.2.1. UV-Vis Spectroscopy

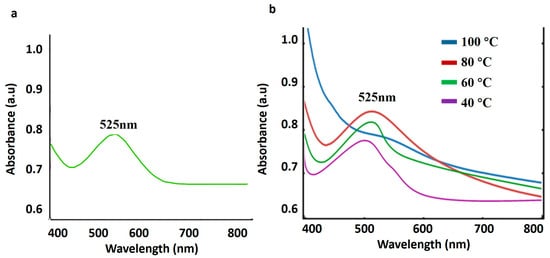

The cooperative swinging of electrons on the nanoparticle surface in response to light causes AuNPs to exhibit a surface plasmon resonance (SPR) band in the visible spectrum that is usually around 520–550 nm (Figure 2a) (Table S1a) [55]. The appearance of an SPR peak in the range of 520–530 nm indicates successful reduction of Au3+ to Au0 nanoparticles, consistent with earlier reports on plant-mediated AuNP synthesis [25,26]. Particle size and shape can be estimated using optical characteristics, which are important markers of nanoparticle production [56].

Figure 2.

UV-visible spectrum of gold nanoparticles developed from an ethanol extraction of test plant. (a) Extreme plasmon surface peak at 525 nm confirming the formation of gold nanoparticles. (b) Stability of biosynthesized gold nanoparticles at different temperatures (40 °C, 60 °C, 80 °C, and 100 °C) shows stability until 80 °C and decreases as the temperature rises to 100 °C.

While bigger or anisotropic particles have a red-shifted SPR, smaller spherical AuNPs often create a sharper SPR peak of about 525 nm [57]. To improve the biocompatibility and functionalization of AuNPs for biomedical applications such as drug administration, biosensing, and antibacterial therapy, plant extracts can add functional groups to the nanoparticle surface [58]. Due to its simplicity, affordability, and lower environmental impact as compared to conventional techniques, plant-mediated AuNP synthesis has showed promise in several studies [59]. These AuNPs are appropriate for application in drug delivery systems and photothermal treatments for the treatment of cancer due to the biocompatibility provided by plant-derived capping agents. Because of their enormous surface area and active sites supplied by plant-based capping agents, the special surface chemistry of biosynthesized AuNPs has also been investigated for catalytic applications, where they can speed up chemical reactions [60].

AuNPs’ redox characteristics rely on their surface and size. Smaller AuNPs interact more effectively with cellular redox systems and may have an impact on the intracellular redox balance because of their larger surface-area-to-volume ratio. The nature of the adsorbed stabilizer also influences redox activity by modifying the surface reactivity [61].

The thermal stability of the biosynthesized AuNPs at various temperatures (40 °C, 60 °C, 80 °C, and 100 °C) was examined using UV–visible spectroscopy in the range of 400 nm–800 nm. The UV–visible spectrum (Figure 2b) (Table S1b) evidently showed a strong peak at 525 nm. The AuNPs exhibited stable SPR characteristics up to 80 °C, whereas a reduction in peak intensity and broadening at 100 °C indicated decreased stability. The increase in SPR extinction intensity from 40 to 80 °C can be attributed to improved nanoparticle dispersion and enhanced reduction/crystallinity at moderate temperatures, leading to better plasmon coupling without aggregation; however, at 100 °C, partial aggregation and surface destabilization occur, resulting in decreased intensity [59].

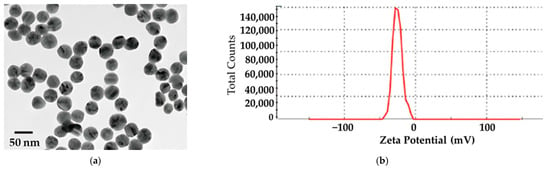

3.2.2. TEM Analysis

TEM provided a detailed examination of the size distribution and morphology of the produced AuNPs, which were primarily spherical and had a small size range of 15 to 38 nm (Figure 3). Because they have a direct impact on how the nanoparticles interact with biological systems, uniform shape and regulated size distribution are essential for biomedical applications. Previous studies have shown that the size of nanoparticles has a significant impact on bioavailability, circulation time, and cellular absorption. Because of their effective cellular internalization and capacity to avoid quick bodily clearance, particles in the 10–50 nm range are thought to be especially advantageous for drug delivery applications [62]. Software imaging in this work had sizes ranging from 15 to 38 nm.

Figure 3.

(a) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the size and morphology of green-synthesized gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) derived from the ethanol extract of the dwarf copper leaf plant. Ethanol extraction effectively reduces and stabilizes gold ions during the synthesis process, with dimensions ranging from 15 nm to 38 nm. (b) Zeta potential of green-synthesized AuNPs.

The AuNPs were mostly spherical and had a limited size distribution, according to the TEM images, which matched the normal characteristics expected for nanomaterials of this kind [63]. The plant extract’s reducing and capping agents, which enable the creation of AuNPs, provide for a great degree of control over nanoparticle morphology and size, facilitating further investigation of these particles for biomedical applications [64]. Furthermore, the zeta potential value of the green-synthesised AuNPs demonstrated the effective stability of nanoparticles [65], as confirmed by the uniform size distribution of nanoparticles in this study. TEM analysis confirmed predominantly spherical AuNPs. Although the nanoparticle size range (15–38 nm) was obtained from manual measurements of representative TEM images, a full statistical analysis including histogram-based size distribution (Figure S4) was provided. PDI determination was not performed and is acknowledged as a limitation of the present study.

3.2.3. Zeta Potential Analysis

The zeta potential, described as a physicochemical property that studies the stability of a colloidal system, is the electrostatic potential that occurs at a particle’s shear plane and is associated with both the surface charge and the particle’s direct environment. The synthesized AUNPs had a zeta potential of −31 mV (Figure 3b). The zeta potentials revealed that the green-synthesized AuNPs exhibited good stability [66]. Such stabilization is attributed to surface-adsorbed phytochemicals containing ionizable functional groups, particularly phenolic acids and flavonoids with deprotonated phenolate (–O−) and carboxylate (–COO−) moieties, which impart negative surface charge to the AuNPs.

The zeta potential and plasmonic wavelength of 525 nm represented a transverse resonance mode typical of the spherical shape of the synthesized AuNPs with virtuous stability.

The concentration and type of phenolic compounds significantly influence nanoparticle morphology and size. Higher concentrations of phenolic or flavonoid compounds generally yield smaller, more uniform nanoparticles due to rapid nucleation and effective capping [67]. Furthermore, zeta potential measurements indicate that these biogenic AuNPs possess strong negative surface charges (−30 mV to −80 mV), ensuring long-term colloidal stability [50].

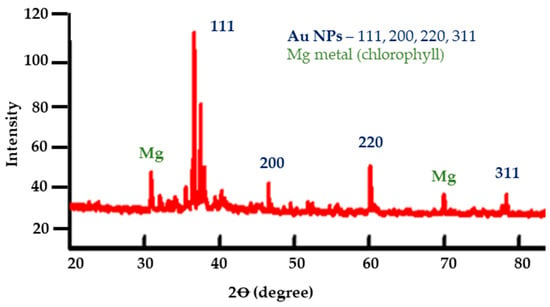

3.2.4. XRD Analysis

The crystalline nature and phase composition of the produced AuNPs were verified by XRD using a fixed monochromator. Several different diffraction lines at angles ranging from 4° to 100° in increments of 0.02° may be seen in the XRD pattern displayed in Figure 4. By comparing these diffraction lines with the typical gold powder diffraction data, it is verified that the produced nanoparticles are indeed gold.

Figure 4.

XRD pattern of biosynthesized AuNPs. Major peaks at 38.1°, 44.3°, 64.6°, and 77.5° correspond to the fcc gold lattice (JCPDS 04-0784). Additional low-intensity peaks arise from residual plant constituents and trace biogenic minerals and are not attributable to Au.

The XRD pattern of the biosynthesized AuNPs (Figure 4) shows the characteristic reflections of the face-centered cubic (fcc) structure of gold at 2θ ≈ 38.1° (111), 44.3° (200), 64.6° (220), and 77.5° (311), in agreement with JCPDS 04-0784 (Table S2). In addition to the characteristic Au reflections, two minor diffraction peaks observed at 2θ ≈ 32.2° and 46.6°, with relative intensities of 14% and 12%, respectively, could not be indexed to standard Au lattice planes. These peaks are therefore attributed to Mg-containing biogenic residues, likely associated with chlorophyll-related magnesium complexes or other Mg-related plant-derived crystalline phases remaining from the phytochemical matrix. These peaks were not indexed as Au. These peaks may be due to presence of impurities.

The presence of the major fcc Au reflections confirms the formation of crystalline gold nanoparticles. However, the additional peaks suggest that the extract matrix or residual organometallic species contributed to the diffraction background, a known characteristic of green synthesis approaches. The identification of fcc Au reflections confirms that the biosynthesized nanoparticles exhibit a crystalline gold phase. The additional low-intensity peaks reflect plant-derived residues inherent to phytochemical-based synthesis routes. Their presence does not interfere with the major Au reflections but indicates that the material contains minor non-Au components, which can be reduced further through improved purification [68].

The observed peaks closely matched the reference values from the Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction Standards (JCPDS), validating the development of AuNPs [69]. The interplanar spacing (crystallite size) between the atoms (d-spacing) was determined using Bragg’s law [70] (Data calculation S1). The d-spacing calculation particulars are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Grain size of the nanoparticles by XRD analysis was calculated by using Bragg’s law.

3.2.5. FT-IR

For identifying the functional groups connected to the nanoparticles, FT-IR was employed to investigate the surface chemistry of the AuNPs. This method is essential for verifying that nanoparticles have been successfully modified, particularly when organic compounds or polymers are employed for stability or functionalization.

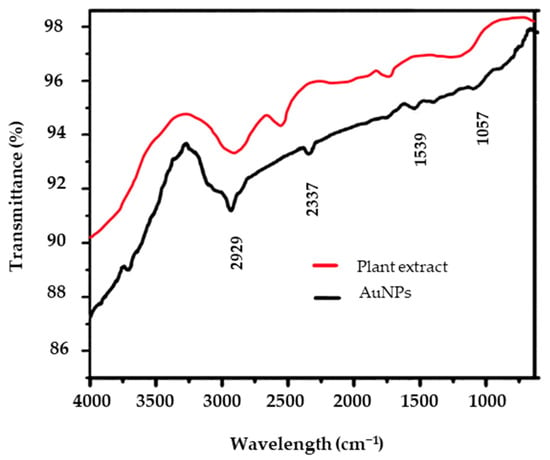

FT-IR spectroscopy analysis of phyto-formulated AuNPs using a dwarf copper leaf plant ethanolic extract showed distinct absorption peaks, suggesting the occurrence of functional groups potentially responsible for the nanoparticles’ reduction and stabilization (Figure 5) (Table S3a). The plant extract (control test) also showed similar distinct peaks in comparison with the AuNPs. The distinctive peaks at 2929 cm−1, 2337 cm−1, 1539 cm−1, and 1057 cm−1 represent different functional groups in the plant extract (Table S3b) that interact with gold ions to promote the creation and stability of nanoparticles. The peak at 2929 cm−1 is usually linked to C–H stretching vibrations, which are probably caused by the plant extract’s aliphatic chains of fatty acids or other organic compounds. This implies that these hydrocarbons are involved in capping the nanoparticles, which improves stability and prevents aggregation [71]. The acute point at 2337 cm−1 may be associated with C≡C or C≡N stretch vibrations, which could suggest the existence of nitriles or alkynes, respectively, that may be produced from secondary metabolites in the plant extract [72]. The band at 1539 cm−1 is frequently attributed to C=C stretching or N–H bending vibrations in aromatic chemicals, including flavonoids and polyphenols, which are well-known antioxidants. These substances serve as stabilizing agents by creating a protective coating on the surface of the nanoparticles and by reducing Au3+ ions to elemental gold (Au1) [73]. Finally, the point at 1057 cm−1 corresponds to C–O or C–O–C stretching vibrations, which may be caused by alcohols or carbohydrates in the plant extract and aid in the stability and capping of AuNPs [74].

Figure 5.

Fourier transform infrared spectra of gold nanoparticles biosynthesized from the ethanolic extract of the test plant indicates possible functional groups within the produced nanoparticles. The IR spectra of the plant extracts show the fingerprints of the bioactive compounds.

Phenolic compounds participate in the reduction of Au3+ ions primarily through oxidation of their aromatic carbon framework, forming quinone- or carbonyl-type intermediates, while hydroxyl groups facilitate hydrogen atom transfer and stabilize transient radical species, collectively enabling the reduction of Au3+ to Au0 [75]. This redox process often involves the transformation of phenolic hydroxyl groups to quinones, generating free electrons that facilitate nanoparticle nucleation [76]. Flavonoids, being polyphenolic in nature, experience tautomeric alteration from the enol to the keto form, discharging reactive hydrogen atoms that participate in the reduction of gold ions [77].

After reduction, the same biomolecules act as stabilizing or capping agents by binding to the nanoparticle surface through functional groups such as –OH, –COOH, and –C=O [69]. This interaction forms a protective organic layer around the nanoparticles, preventing aggregation and enhancing colloidal stability [78]. The electrostatic repulsion and steric hindrance provided by these biomolecular coatings maintain the uniform dispersion of AuNPs in solution. FTIR spectra of biosynthesized AuNPs often show characteristic changes in the –OH and –C=O stretching vibrations, confirming the binding of phenolic and flavonoid groups to the nanoparticle surface [79,80,81,82].

These results propose that the ethanolic extract of Alternanthera paronychioide contains a diverse array of bioactive compounds that may contribute to its protective effects against endothelial hyperpermeability and oxidative stress [20].

FTIR analysis indicates that hydroxyl, carbonyl, and C–O/C–O–C functional groups present in the plant extract interact with the gold surface during nanoparticle formation. The observed shifts between the plant extract and AuNP spectra confirm the involvement of these groups in both reduction and capping. However, FTIR does not permit identification of individual phytochemicals, and the interpretation is therefore restricted to functional-group level evidence.

3.3. Anticancer Activity on Breast Cancer Cells

3.3.1. MTT-Based Cytotoxicity Assay

The synthesized AuNPs from the ethanolic extract of the test plants have demonstrated encouraging anticancer effects against breast cancer cells. In the present study, the cytotoxic effects of AuNPs on a breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) were assessed using an MTT-based cytotoxicity assay, which demonstrated the antineoplastic properties of AuNPs. Cells were treated with varying concentrations of AuNPs (20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg/mL) for 48 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator until they reached approximately 80% confluency.

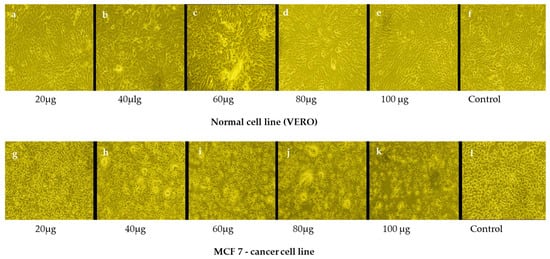

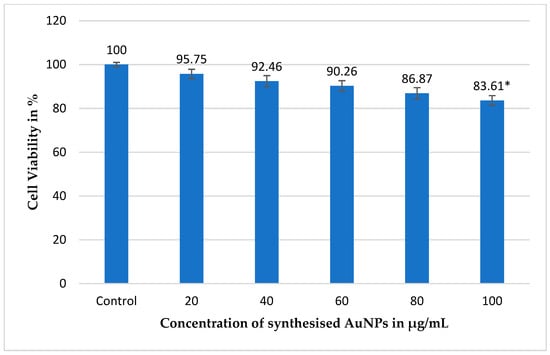

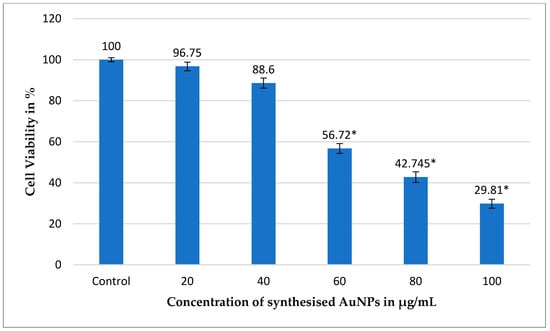

Morphological changes in the untreated (control) and breast cancer cells were recorded under an inverted microscope after 48 h and photographed. The results showed that an increase in the concentration of AuNPs led to a significant reduction in the viability of breast cancer cells compared to that of normal Vero cells (Figure 6). Specifically, concentrations of 80–100 µg/mL resulted in marked cell death, demonstrating the potential of AuNPs as an effective antineoplastic agent against breast cancer. The nanoparticles induce cytotoxic effects through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, apoptosis, or interference with cellular signaling pathways specific to cancer cells. The green-synthesized AuNPs from dwarf copper leaf plant extract seemed to show better cellular toxicity toward neoplastic cells, probably due to the improved vulnerability of cancerous cells to oxidative stress compared to normal cells [83]. This was established by spectrophotometrically measuring the absorbance at 570 nm (Figure 7 and Figure 8) (Tables S6 and S7). These studies, together with previous reports, suggest that green-synthesized AuNPs exert their anticancer effects by enhancing intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation while sparing normal cells that possess lower basal ROS levels.

Figure 6.

Anticancer efficacy of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) synthesized using the ethanolic extract of a plant against breast cancer cells (MCF-7) compared to their effects on normal cell lines over 48 h under controlled conditions at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator, simulating physiological conditions to assess nanoparticle activity. (a–f) Impact of AuNPs on normal cell lines at different concentrations. Minimal toxicity or adverse effects suggest the biocompatibility and safety of the synthesized Au NPs for normal cells. (g–l) Response of MCF-7 breast cancer cells to the AuNPs. Images show significant morphological changes and increased cell death, indicating effective anticancer activity.

Figure 7.

Evaluation of the cell viability of normal cells exposed to gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) synthesized using the ethanolic extract of the test plant. Experiment was conducted over a 48 h incubation period at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 environment, simulating physiological conditions. Percentage of viable cells after treatment with varying concentrations of AuNPs, with untreated cells serving as the control group. Error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments performed in triplicate (n = 3). A p-value of <0.05 (*) indicates that the observed results are statistically significant. These findings confirm the high biocompatibility of the biosynthesized AuNPs, as they maintained normal cell viability, supporting their potential use in biomedical applications with minimal cytotoxicity to healthy tissues.

Figure 8.

Assessment of cell viability in MCF-7 breast cancer cells treated with gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) synthesized using the ethanolic extract of dwarf copper leaf plant after 48 h of incubation at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 environment. Percentage of viable MCF-7 cells following exposure to various concentrations of AuNPs, with untreated MCF-7 cells as the control. Statistical significance is represented by error bars (from three independent experiments performed in triplicate, n = 3), which indicate the mean ± standard deviation (SD), with a p-value of <0.05 (*). This analysis highlights the potential anticancer activity of the synthesized AuNPs, as the nanoparticles exhibit a dose-dependent reduction in cell viability, suggesting their effectiveness in targeting cancer cells. The significant p-value further supports the reliability of the findings, indicating that the observed effects are statistically meaningful.

Damage to the mitochondrial membrane potential was confirmed by observations utilizing mitochondrial dyes, such as formazan crystals, which showed a notable depolarization of mitochondrial membranes in AuNP-treated cells [84]. AuNPs synthesized using Alternanthera paronychioides are capped with phytochemicals such as flavonoids and phenolics, which not only stabilize the nanoparticles but also enhance their cytotoxicity against cancer cells. These adsorbed compounds induce cell death through oxidative stress and apoptotic pathways, while remaining largely nontoxic to normal cells owing to their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. This revealed that the surface-bound bioactives from A paronychioides significantly contribute to the cytotoxic effects of nanogold [85]. AuNPs can induce apoptosis in cancer cells, correlating with increased concentrations and exposure times [86]. Similarly, AuNPs revealed selective cellular toxicity towards numerous cancer cell lines, including breast cancer, enhancing their viability as drug delivery systems or therapeutic agents [86,87,88,89].

The shape and size of the AuNPs show an important role in the cytotoxicity of the cell line. In the present study, the synthesized AuNPs were revealed to be spherical in shape, with sizes ranging from 15 to 38 nm, and exhibited cellular toxicity against MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Smaller spherical AuNPs enter cells via receptor-mediated endocytosis [90]. The spherical AuNPs exhibited higher toxicity than the rod-shaped AuNPs [91]. Researchers have confirmed that the cells experience reversible aging upon exposure to low quantities of Au ions. At short period of time (0–8 h), abrupt pH changes in the adjacent media lead to the denaturation of serum proteins and cell membrane proteins, which activates a rapid reduction of Au3+ to spherical NPs such as Au0. Within 0–8 h, abrupt pH shifts in the cell medium, possibly due to cell metabolism or experimental handling, can cause serum and membrane proteins to denature. These denatured proteins expose thiol (-SH), amine (-NH2), and carboxyl (-COOH) groups that can bind Au3+ ions, reduce them to metallic Au0, and stabilize the forming spherical AuNPs. This initiates rapid nucleation of AuNPs in biological systems. At longer time intervals (up to a week), the composite protein-gold spherical particles act as nucleation sites, where the reduction of more AuCl4 ions on the Au nuclei takes place and ordered agglomeration into composite nanoparticles occurs [92]. In the present study, AuNPs with a narrow size distribution (15–38 nm) and spherical morphology were synthesized. This narrow size range suggests that a uniform nucleation and growth mechanism is likely mediated by protein interactions, consistent with the referenced work [93], and minimal uncontrolled aggregation, indicating good colloidal stability, probably due to protein corona stabilization. These factors directly contribute to the cytotoxic behavior observed in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Smaller spherical nanoparticles (especially ~20–30 nm) have better size via endocytosis. Surface chemistry influenced by protein coronas may enhance targeting or interaction with cell membranes. Shape and size critically dictate the intracellular fate and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby affecting cell viability.

Through the present study, it was clear that phyto-formulated AuNPs are known to enter cancer cells predominantly through endocytic pathways. This was followed by intracellular accumulation that can trigger oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Elevated ROS levels may induce DNA damage and activate apoptosis-related signaling pathways, ultimately reducing cell viability in MCF-7 cells. The presence of bioactive phytochemicals on the nanoparticle surface may further enhance cytotoxic selectivity toward cancer cells while minimizing toxicity to normal cells.

The present study did not include a chemotherapeutic positive control, which limits direct comparison of AuNP cytotoxicity against established anticancer drugs. The results therefore reflect relative cytotoxicity compared with untreated cells. Future work will include agents such as doxorubicin or paclitaxel to enable standardized potency benchmarking and mechanistic validation.

3.3.2. Morphological Observations in Breast Cancer Cells Post-AuNP Treatment

MCF-7 cells treated with AuNPs made from dwarf copper leaf plant extract were observed for morphological alterations using inverted microscopy. Following 48 h of treatment, the cells displayed typical apoptotic characteristics, such as chromatin condensation, cell membrane blebbing, cell decrease, and the formation of apoptotic bodies. The cytotoxic selectivity of AuNPs against cancer cells is highlighted by the fact that untreated control cells retained their normal shape. The morphology of cells exposed to different AuNP concentrations also showed several alterations, such as cell shrinkage, detachment from the surface substrate, a decrease in the number of cells visible in the field, and, in certain cases, darkened cellular compartments [94,95,96]. In this investigation, the spherical structure of the biosynthesized AuNPs contributed to their cellular absorption and cytotoxic effects against MCF7 cells, in addition to their size [97].

3.4. Antimicrobial Activity of Green-Synthesized AUNPs

The antimicrobial activity of the greenish-brown ethanolic extract of a dwarf copper leaf plant, chemically synthesized gold nanoparticles (AuNPs without extract), and green-synthesized gold nanoparticles (E–AuNPs) were assessed against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Serratia species, and Salmonella typhimurium. The results are presented as the mean zone of inhibition (ZOI, mm) ± standard deviation at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 2 mg/mL (Table 2).

Table 2.

Zone of inhibition (ZOI) values of green synthesized AuNPs by well diffusion method (mean ± standard deviation).

A concentration-dependent increase in ZOI was observed for both the plant extract and the E–AuNPs, indicating that bactericidal activity intensified with increasing concentration. Among the tested organisms, B. cereus and Serratia sp. exhibited the highest sensitivity, followed by S. epidermidis and S. typhimurium. At higher concentrations (0.1–0.2 mg/mL), the maximum inhibition zones were recorded (Figure S3).

The zone of inhibition (ZOI) results (in mm) demonstrated that E–AuNPs exhibited the most modest bactericidal activity across all tested strains (16, 6, 13, and 7 mm, respectively). In contrast, the plant extract alone showed mild inhibition (10, 4, 9, and 5 mm), whereas AuNPs without plant extract exhibited minimal or negligible activity (2.5, 1.5, 2.5, and 2 mm). This pattern clearly demonstrates that E–AuNPs exhibited superior bactericidal activity compared to the plant extract and AuNPs synthesized without plant components.

The plant extract alone established moderate antimicrobial activity (2–9 mm), with the highest inhibition observed against Bacillus cereus (10 ± 0.25 mm), followed by Serratia species (9 ± 0.02 mm), Salmonella typhimurium (5 ± 0.20 mm), and Staphylococcus epidermidis (4.5 ± 0.14 mm) compared with the positive control (pc), which showed negligible activity, and the negative control, which remained inactive. The observed activity can be credited to the existence of bioactive phyto constituents, for instance, flavonoids, terpenoids, tannins, phenolics, and alkaloids that exert bactericidal effects through disruption of cell walls, protein denaturation, and enzyme inhibition.

AuNPs synthesized without the plant extract displayed weak bactericidal activity (1–2.5 mm), signifying limited intrinsic antimicrobial potential. Their effect is primarily due to physical interactions with bacterial cell membranes rather than chemical toxicity, and the absence of capping phytochemicals limits their biological reactivity.

The positive control (pc) exhibited moderate inhibition (2–2.5 mm), confirming the reliability of the assay, whereas the negative control (nc) produced no inhibition, indicating the absence of solvent or contamination effects.

Although E–AuNPs produced larger inhibition zones than the plant extract and AuNPs alone, these values cannot be directly compared with tetracycline due to fundamental differences in diffusion rates between nanoparticles and small-molecule antibiotics.

The bactericidal effect of the crude extract can be ascribed to its bioactive phytochemicals, mainly phenolic compounds and flavonoids, which act by damaging bacterial membrane integrity, chelating essential ions, and interfering with cellular enzymes [98,99].

When the plant extract was used to synthesize AuNPs, the resulting nanomaterial displayed a significant enhancement in antimicrobial efficacy. The extract + AuNPs formulation exhibited larger inhibition zones across all bacterial strains, confirming the synergistic interaction between the phytochemicals and the gold nanoparticles. Notably, the ZOI for Bacillus cereus increased to 16 ± 0.18 mm and for Serratia species increased to 13 ± 0.10 mm, representing an enhancement of 25–45% compared to the extract alone (Figure 2). These findings are reliable with previous reports where biogenic AuNPs capped with plant-derived metabolites displayed higher bactericidal potency due to the combined effects of metallic and phytochemical components [75,100].

This finding is consistent with earlier research in which green-synthesised AuNPs demonstrated a moderate level of effectiveness against Gram-positive bacteria, which was explained by the nanoparticles’ ease of penetration of the bacterial cell walls [101]. The comparatively lower ZOI against Staphylococcus epidermidis and Salmonella typhimurium in comparison to other strains examined points to a species-specific interaction that may be impacted by the makeup of the bacterial cell wall [102].

The AuNPs exhibited bactericidal activity against both Gram-negative (Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium) and Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis) bacteria, with a clear strain-dependent variation. While stronger inhibition was observed against E. coli and S. aureus, comparatively smaller zones of inhibition were noted for S. typhimurium and S. epidermidis [103,104]. Gram-negative bacteria’s structural traits, such as their thinner peptidoglycan coatings, may increase the penetration of nanoparticles and cause cellular integrity to be disrupted, ultimately resulting in cell death [105]. The broad-spectrum potential of AuNPs produced using the green technique is confirmed by the significant ZOI shown in B. cereus and other strains. This is because AuNPs’ reduced size and steady dispersion characteristics improve interactions with bacterial cell membranes [106]. A previous study [107] demonstrated that bactericidal efficacy was influenced by the quantity of AuNPs. A slight increase in the AuNP concentration significantly boosted the anti-biofilm activity of the nanocomposite, effectively preventing 99.99% of Klebsiella spp. as well as Staphylococcus epidermidis [108].

In the current study, AuNPs exhibited the highest zone of inhibition (ZOI) against Bacillus cereus, which is consistent with the findings of earlier studies. The higher activity against Serratia species may be associated with the presence of secondary metabolites in the dwarf copper leaf plant extract, which may engage harmoniously with AuNPs in employing bactericidal effects [109]. These results show that green-synthesised AuNPs can function as potent bactericidal agents and provide a sustainable substitute for traditional techniques [110]. Previous reports have described the molecular pathways that control how nanoparticles interact with bacterial cell walls and how well they work when combined with other bactericidal drugs to improve their therapeutic applications [111]. AuNPs are thought to electrostatically adsorb onto bacterial membranes and interact strongly with lysine residues on the membranes of Gram-positive bacteria that contain the –CH2CH2CH2NH2 group. This could potentially damage Gram-positive cells [112] and cause irreversible pores that kill the bacteria [113]. Once internalized, the AuNPs reduce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels, thereby impairing bacterial metabolism [114]. Furthermore, AuNPs increase the photocatalytic activity of oxides like zinc oxide and titanium dioxide, which makes it easier to produce reactive species including hydroxyl groups, peroxides, and high oxygen concentrations [115,116,117]. Excess ROS are produced by this mechanism [118]. The bacterium’s extracellular electron transport route can be disrupted by ROS, which ultimately prevents the bacterium from growing [119].

AuNPs’ redox characteristics depend on their size and surface. Smaller AuNPs interact more effectively with cellular redox systems due to their larger surface-area-to-volume ratio, potentially affecting the intracellular redox balance. The nature of the adsorbed stabilizer also influences redox activity by modifying the surface reactivity [120].

Nanoparticles possess a larger surface area than larger particles, which enhances their bactericidal properties. AuNPs bind to protein functional groups, leading to protein deactivation and modification. The bactericidal activity of the nanocomposites is influenced by their size [121]. Owing to their nanoscale dimensions [122], AuNPs can readily penetrate bacterial cell walls, causing DNA condensation, impairing replication, and eventually resulting in cell death. In addition, the entry of AuNPs into bacterial cells disrupts enzymatic activity, promotes hydrogen peroxide production, and leads to bacterial cell death [123].

By interacting with the sulfur and phosphorus groups of the DNA or protein, the AuNPs may also infiltrate the microorganism and inflict harm. Because of the electrostatic attraction between the positively charged AuNPs and the negatively charged bacterial cell membrane, the AuNPs may attach to the cytoplasmic membrane and kill the bacterial cell [124,125].

The ZOI values for both the plant extract and E–AuNPs followed a dose-dependent (sigmoidal) pattern, indicating that bactericidal activity increases with concentration. Based on graphical extrapolation (ZOI vs. concentration), the IC50 (concentration at which 50% of maximum inhibition occurs) values for E–AuNPs were estimated (Table 3).

Table 3.

IC50 values for E–AuNPs (green synthesized) against tested bacterial strains.

The bactericidal effect of E–AuNPs are significantly higher for all bacterial strains, indicating synergistic interaction between phytochemicals and gold nanoparticles. The bioactive compounds act as both reducing and capping mediators, stabilizing AuNPs and enhancing bacterial membrane penetration, while gold nanoparticles increase the surface reactivity of phytochemicals, resulting in enhanced antimicrobial potency.

Plant extract alone containing antimicrobial phytochemicals often showed moderate activity (ZOI) in agar assays [126,127]. AuNPs without active phytochemical capping frequently show low or inconsistent bactericidal activity at comparable concentrations; their antimicrobial effect depends strongly on surface chemistry, size, and shape [128]. Phytochemical-capped (green-synthesized) AuNPs often show significantly higher bactericidal activity than either the extract or AuNP alone—explained by combined mechanisms (enhanced membrane interaction, ROS, and local delivery of phytochemicals) [129].

The dose-dependent increase in ZOI values for E–AuNPs supports concentration-dependent antibacterial efficacy, allowing estimation of IC50 values (Table 3). Lower IC50 values compared to plant extract alone further indicate improved antibacterial performance following nanoparticle conjugation, consistent with previous reports on green-synthesized AuNPs [126,127,128,129].

FT-IR analysis confirmed the presence of surface-bound functional groups (–CH, –C=O, –NO2, and –C–O), suggesting successful phytochemical capping of AuNPs (Figure 4). These surface functionalities are commonly associated with plant-mediated nanoparticle stabilization and enhanced biological interaction [130,131,132]. The contribution of these surface groups is therefore discussed in the context of enhanced nanoparticle–bacteria interaction, rather than direct mechanistic causation.

The presence of these surface-bound phytochemicals on the AuNPs contributes to the synergistic antimicrobial mechanism. The phytochemical constituents not only stabilize the nanoparticles but also enhance their affinity for bacterial cell walls. Positively charged AuNPs interact electrostatically with negatively charged bacterial membranes, leading to cell wall disruption and increased permeability. In parallel, phytochemical moieties deliver oxidative stress and metabolic inhibition, collectively resulting in higher bactericidal activity [133,134].

By improving interaction with bacterial cell walls, gold nanoparticles can greatly boost the bactericidal effect of medications and provide a stable surface for binding a variety of antibiotic medicines. Research has demonstrated that gold nanoparticles and other bactericidal medications work better together than gold nanoparticles and antimicrobial medications by themselves. In the present study also, the anti-bacterial effect of plant extract + AuNPs formulation was found to be more effective than only plant extract and AuNPs alone. This was comparable to the previously published study in which AuNPs and another bactericidal drug, like ciprofloxacin, had synergistic effects, and the combination’s bactericidal activity was greater than AuNPs’ alone [135].

The enhanced antimicrobial activity of the plant extract + AuNPs formulation can thus be attributed to this dual mechanism, which leads to the physicochemical interaction of AuNPs and the biochemical actions of the plant-derived compounds (Table S8). This synergy intensifies bacterial damage via reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, DNA condensation, and protein denaturation [136].

The antimicrobial activity of phytoformulated AuNPs can be attributed to their interaction with bacterial cell membranes, leading to increased permeability and structural damage. Additionally, AuNPs may induce oxidative stress and interfere with essential metabolic enzymes and protein synthesis. The enhanced activity observed against certain bacterial strains may result from differences in cell wall architecture and the synergistic action of surface-bound phytochemicals.

Overall, the findings clearly establish that plant-mediated AuNPs possess superior bactericidal activity compared to plant extracts or pure AuNPs, confirming the synergistic nature of bio-reduction and nanoparticle formation. This highlights their potential as eco-friendly and potent antimicrobial agents (Table S9).

4. Conclusions

This study effectively demonstrates the phyto-formulation of AuNPs using an ethanolic extract from a dwarf copper leaf plant, showcasing a sustainable and eco-friendly approach to nanoparticle fabrication. The synthesized AuNPs exhibited notable antineoplastic properties against MCF-7 breast cancer cells, with amplified AuNP concentrations leading to a significant reduction in cell viability. Characterization methods such as TEM, XRD, and FT-IR confirmed the formation, morphology, and functionalization of AuNPs, underscoring the role of phytochemicals in the plant extract in reducing and stabilizing the nanoparticles.

Furthermore, AuNPs displayed promising bactericidal activity against a range of bacterial strains, indicating their ability as effective bactericidal agents. These results highlight the advantageous properties of plant-derived AuNPs, including their biocompatibility and the ability to induce selective cytotoxicity in cancer cells. This study suggests that biosynthesized AuNPs could serve as a valuable platform, which is required for developing novel antibacterial and anticancer products, with research in this area actively underway. Overall, these conclusions contribute to a rising body of evidence promoting the utility of green synthesis methods in nanoparticle production, paving the way for more sustainable practices in nanotechnology.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr14010105/s1: Figure S1: Preparation of the ethanol extract of dwarf copper leaf plant; Figure S2: Preparation of gold nanoparticles using ethanol extract of dwarf copper leaf plant; Figure S3: Antibacterial activity of green-synthesized gold nanoparticles (AuNPs); Figure S4: Particle size distribution histogram of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) synthesized using Alternanthera paronychioides extract; Table S1a: UV–Vis absorbance values corresponding to Figure 2a, showing the surface plasmon resonance peak of biosynthesized AuNPs at ~525 nm; Table S1b: UV–Vis absorbance values of AuNPs at different temperatures (40–100 °C); Table S2: Digitized XRD peak positions and relative intensities corresponding to Figure 4, including Au fcc reflections (JCPDS 04-0784) and minor Mg-associated biogenic peaks from plant extract residues; Table S3a: FTIR raw peak data (A) plant extract (red curve); Table S3b: FTIR raw peak data (B) AuNp (black curve); Table S4: Standardized conditions used for plant-extract–mediated AuNP synthesis; Table S5: Zeta-potential measurement conditions; Table S6: MTT assay for Vero cell; Table S7: MTT assay for breast cancer cell; Table S8: Comparative summary of anticancer and antimicrobial activities of green-synthesized gold nanoparticles reported in literature and the present study. The table highlights plant source, nanoparticle characteristics, biological models, assay methods, and major biological outcomes to contextualize the performance of the phyto-formulated AuNPs; Table S9: Comparative summary highlighting the key advantages and limitations of gold nanoparticles; Data calculation S1: Calculation method to validate the XRD peaks values of AuNPs and calculations for d-spacing using Bragg’s Law.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.V. and S.K.R.; methodology, K.N.; software, A.K.; validation, K.N. and A.K.; formal analysis, G.V.; investigation, K.N. and A.K.; resources, S.K.R.; data curation, K.N.; writing original draft preparation, G.V.; writing—review and editing, S.K.R.; supervision, S.K.R.; project administration, S.K.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/global-breast-cancer-initiative (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Kulothungan, V.; Ramamoorthy, T.; Sathishkumar, K.; Mohan, R.; Tomy, N.; Miller, G.J.; Mathur, P. Burden of Female Breast Cancer in India: Estimates of YLDs, YLLs, and DALYs at National and Subnational Levels Based on the National Cancer Registry Programme. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2024, 205, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, M.C.; Kavanaugh-Lynch, M.H.E.; Davis-Patterson, S.; Buermeyer, N. An Expanded Agenda for the Primary Prevention of Breast Cancer: Charting a Course for the Future. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkler, M.-C.; Hetjens, S. Risk Factors and Preventive Measures for Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, M.L.; Vera, D.M.A.; Laiolo, J.; Joray, M.B.; Maccioni, M.; Palacios, S.M.; Molina, G.; Lanza, P.A.; Gancedo, S.; Rumjanek, V.; et al. Mechanism Underlying the Reversal of Drug Resistance in P-Glycoprotein-Expressing Leukemia Cells by Pinoresinol and the Study of a Derivative. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldossary, S.A. Review on Pharmacology of Cisplatin: Clinical Use, Toxicity and Mechanism of Resistance of Cisplatin. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2019, 12, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liu, R.; Yang, J.; Dai, J.; Fan, S.; Pi, J.; Wei, Y.; Guo, X. Gold Nanoparticles: Construction for Drug Delivery and Application in Cancer Immunotherapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, A.; Sharma, S.; Gakkhar, N. Nanotechnology in Cancer Therapy: An Overview and Perspectives (Review). Int. J. Pharm. Chem. Anal. 2020, 6, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanage, P.Y.; Hettiarachchi, S.D.; Zhou, Y.; Ouhtit, A.; Seven, E.S.; Oztan, C.Y.; Celik, E.; Leblanc, R.M. Nanoparticle-Mediated Targeted Drug Delivery for Breast Cancer Treatment. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) Rev. Cancer 2019, 1871, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, D.S.; Dhasmana, A.; Laskar, P.; Prasad, R.; Jain, N.K.; Srivastava, R.; Jaggi, M.; Chauhan, S.C.; Yallapu, M.M. Nanotechnology Synergized Immunoengineering for Cancer. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2021, 163, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skłodowski, K.; Chmielewska-Deptuła, S.J.; Piktel, E.; Wolak, P.; Wollny, T.; Bucki, R. Metallic Nanosystems in the Development of Antimicrobial Strategies with High Antimicrobial Activity and High Biocompatibility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Garay, R.; Lara-Ortiz, L.F.; Campos-López, M.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, D.E.; Gamboa-Lugo, M.M.; Mendoza-Pérez, J.A.; Anzueto-Ríos, Á.; Nicolás-Álvarez, D.E. A Comprehensive Review of Silver and Gold Nanoparticles as Effective Antibacterial Agents. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnwal, A.; Sachan, R.S.K.; Devgon, I.; Devgon, J.; Pant, G.; Panchpuri, M.; Ahmad, A.; Alshammari, M.B.; Hossain, K.; Kumar, G. Gold Nanoparticles in Nanobiotechnology: From Synthesis to Biosensing Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 29966–29982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rosa, S.Y.G.; Diaz, R.M.; Gutiérrez, P.T.V.; Patakfalvi, R.; Coronado, Ó.G. Functionalized Platinum Nanoparticles with Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, I.; Kennedy, D.C. Size-Specific Copper Nanoparticle Cytotoxicity Varies between Human Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez, F.; Caruana, P.; De la Fuente, N.; Español, P.; Gámez, M.; Balart, J.; Llurba, E.; Rovira, R.; Ruiz, R.; Martín-lorente, C.; et al. Nano-Based Approved Pharmaceuticals for Cancer Treatment: Present and Future Challenges. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, A.K.; Allu, R.; Chandran, R.; Gopi, D.K.; Narayana, S.K.K.; Prakasam, R.; Ramachandran, S. Chemical Characterization of Two Botanicals from Genus Alternanthera—A. brasiliana (L.) Kuntze and A. paronychioides A. St. Hil. Pharmacogn. Res. 2024, 16, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannerselvam, B.; Thiyagarajan, D.; Pazhani, A.; Thangavelu, K.P.; Kim, H.J.; Rangarajulu, S.K. Copperpod Plant Synthesized AgNPs Enhance Cytotoxic and Apoptotic Effect in Cancer Cell Lines. Processes 2021, 9, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreaden, E.C.; Alkilany, A.M.; Huang, X.; Murphy, C.J.; El-Sayed, M.A. The golden age: Gold Nanoparticles for Biomedicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 2740–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płaza-Altamer, A.; Kołodziej, A. Advances in the Synthesis and Application of Gold Nanoparticles for Laser Mass Spectrometry: A Mini Review. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2024, 59, 1435–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathishkumar, M.; Geethalakshmi, S.; Saroja, M.; Venkatachalam, M.; Gowthaman, P. Chapter Three—Antimicrobial Activities of Biosynthesized Nanomaterials. Compr. Anal. Chem. 2021, 94, 81–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.; Shyanti, R.K.; Pathak, B. Plant-mediated Synthesis of Silver and Gold Nanoparticles for Antibacterial and Anticancer Applications. In Green Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Biomedical Applications; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabali, A.A.A.; Akkam, Y.; Al Zoubi, M.S.; Al-Batayneh, K.M.; Al-Trad, B.; Alrob, O.A.; Alkilany, A.M.; Benamara, M.; Evans, D.J. Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Leaf Extract of Ziziphus Zizyphus and Their Antimicrobial Activity. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iravani, S. Green Synthesis of Metal Nanoparticles Using Plants. Green. Chem. 2011, 13, 2638–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.R., S.K.; Bongale, M.M.; Sachidanandam, M.; Maurya, C.; Yuvraj; Sarwade, P.P. A Review on Green Synthesized Metal Nanoparticles Applications. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 3, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Annu; Ikram, S.; Yudha, S. Biosynthesis of Gold Nanoparticles: A Green Approach. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2016, 161, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandalakshmi, K.; Venugobal, J.; Ramasamy, V. Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles by Green Synthesis Method Using Pedalium Murex Leaf Extract and Their Antibacterial Activity. Appl. Nanosci. 2015, 6, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadoun, S.; Arif, R.; Jangid, N.K.; Meena, R.K. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 19, 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebre, S.H. Bio-inspired Synthesis of Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: The Key Role of Phytochemicals. J. Clust. Sci. 2022, 34, 665–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Saifullah; Ahmad, M.; Swami, B.L.; Ikram, S. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Azadirachta Indica Aqueous Leaf Extract. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2016, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.K.; Gogoi, N.; Bora, U. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Nyctanthes Arbortristis Flower Extract. Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 2011, 34, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Kim, Y.-J.; Zhang, D.; Yang, D.-C. Biological Synthesis of Nanoparticles from Plants and Microorganisms. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, A.Y. Synthesized Polymeric Nanocomposites with Enhanced Optical and Electrical Properties Based on Gold Nanoparticles for Optoelectronic Applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2023, 34, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, K.K.; Rabha, B.; Pati, S.; Sarkar, T.; Choudhury, B.K.; Barman, A.; Bhattacharjya, D.; Srivastava, A.; Baishya, D.; Edinur, H.A.; et al. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts as Beneficial Prospect for Cancer Theranostics. Molecules 2021, 26, 6389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.K.; Yngard, R.A.; Lin, Y. Silver Nanoparticles: Green Synthesis and Their Antimicrobial Activities. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2009, 145, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.-H. Biofabrication of AuNPs Using Coriandrum Sativum Leaf Extract and Their Antioxidant, Analgesic Activity. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 767, 144914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouda, A.; Eid, A.M.; Guibal, E.; Hamza, M.F.; Hassan, S.E.-D.; Alkhalifah, D.H.M.; El-Hossary, D. Green Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles by Aqueous Extract of Zingiber officinale: Characterization and Insight into Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and In Vitro Cytotoxic Activities. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.A.; Hossain, N.; Kchaou, M.; Nandee, R.; Shuvho, B.A.; Sultana, S. Scope of Eco-friendly Nanoparticles for Anti-microbial Activity. Curr. Res. Green. Sustain. Chem. 2021, 4, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlier, D.; Thomasset, N. Use of MTT Colorimetric Assay to Measure Cell Activation. J. Immunol. Methods 1986, 94, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.E.; White, M.K.; Alsudani, Z.A.N.; Watanabe, F.; Biris, A.S.; Ali, N. Cellular Uptake of Gold Nanorods in Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beik, J.; Khateri, M.; Khosravi, Z.; Kamrava, S.K.; Kooranifar, S.; Ghaznavi, H.; Shakeri-Zadeh, A. Gold Nanoparticles in Combinatorial Cancer Therapy Strategies. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 387, 299–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezhilarasu, H.; Vishalli, D.; Dheen, S.T.; Bay, B.-H.; Srinivasan, D.K. Nanoparticle-Based Therapeutic Approach for Diabetic Wound Healing. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouritzen, M.V.; Andrea, A.; Qvist, K.; Poulsen, S.S.; Jenssen, H. Immunomodulatory Potential of Nisin A with Application in Wound Healing. Wound Repair. Regen. 2019, 27, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marslin, G.; Siram, K.; Maqbool, Q.; Selvakesavan, R.K.; Kruszka, D.; Kachlicki, P.; Franklin, G. Secondary Metabolites in the Green Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles. Materials 2018, 11, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Dutta, T.; Kim, K.-H.; Rawat, M.; Samddar, P.; Kumar, P. ‘Green’ Synthesis of Metals and Their Oxide Nanoparticles: Applications for Environmental Remediation. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 16, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Shen, Y.; Xie, A.; Yu, X.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Capsicum annuum L. Extract. Green. Chem. 2007, 9, 852–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauthal, P.; Mukhopadhyay, M. Noble Metal Nanoparticles: Plant-Mediated Synthesis, Mechanistic Aspects of Synthesis, and Applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 9557–9577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Fawcett, D.; Sharma, S.; Tripathy, S.K.; Poinern, G.E.J. Green Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles via Biological Entities. Materials 2015, 8, 7278–7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.K.; Chisti, Y.; Banerjee, U.C. Synthesis of Metallic Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013, 31, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J. Ligand-controlled Preparation and Fundamental Understanding of Anisotropic Gold Nanostructures. Ph.D. Thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, P.; Das, B.; Mohanty, A.; Mohapatra, S. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Azadirachta indica leaf extract and its antimicrobial study. Appl. Nanosci. 2017, 7, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Patil, S.; Ahire, M.; Kitture, R.; Gurav, D.D.; Jabgunde, A.M.; Kale, S.; Pardesi, K.; Shinde, V.; Bellare, J.; et al. Gnidia Glauca Flower Extract Mediated Synthesis of Gold Nanoparticles and Evaluation of Its Chemocatalytic Potential. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2012, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, S.; Daneshkhah, A.; Diwate, A.; Patel, H.; Smith, J.; Reul, O.; Cheng, R.; Izadian, A.; Hajrasouliha, A.R. Model for Gold Nanoparticle Synthesis: Effect of pH and Reaction Time. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 16847–16853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabikhan, A.; Kandasamy, K.; Raj, A.; Alikunhi, N.M. Synthesis of Antimicrobial Silver Nanoparticles by Callus and Leaf Extracts From Saltmarsh Plant, Sesuvium portulacastrum L. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 79, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, S.; Rai, A.; Ahmad, A.; Sastry, M. Rapid synthesis of Au, Ag, and Bimetallic Au core–Ag Shell Nanoparticles Using Neem (Azadirachta indica) Leaf Broth. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2004, 275, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liz-Marzán, L.M. Tailoring Surface Plasmons through the Morphology and Assembly of Metal Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2005, 22, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prathna, T.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Raichur, A.M.; Mukherjee, A. Biomimetic Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles by Citrus Limon (lemon) Aqueous Extract and Theoretical Prediction of Particle Size. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2011, 82, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iravani, S.; Korbekandi, H.; Mirmohammadi, S.V.; Zolfaghari, B. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles: Chemical, Physical and Biological Methods. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 9, 385–406. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, G.; Nam, J.-S.; Sharma, A.R.; Lee, S.-S. Antimicrobial Potential of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Medicinal Herb Coptidis rhizome. Molecules 2018, 23, 2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Cheong, J.Y.; Sitaru, G.; Rosenfeldt, S.; Schenk, A.S.; Gekle, S.; Kim, I.-D.; Greiner, A. Size-Dependent Catalytic Behavior of Gold Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]