Abstract

This study develops a coupled Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) and the Discrete Element Method (DEM) framework to explore the sedimentation behavior of densely arranged particles in vertical pipes. An unresolved SPH-DEM model is proposed, which integrates porosity-dependent fluid governing equations through local averaging techniques to connect pore-scale interactions with macroscopic flow characteristics. Validated against single-particle settling experiments, the model accurately captures transient acceleration, drag equilibrium, and rebound dynamics. Systematic simulations reveal that particle number, arrangement patterns, and fluid domain geometry play critical roles in regulating collective settling: Increasing particle count induces nonlinear terminal velocity reduction. Systems of 16 particles show 50% lower velocity than single-particle cases due to enhanced shielding and energy dissipation. Particle configuration (compact layouts 4 × 8 vs. elongated arrangements 8 × 4) dictates hydrodynamic resistance, compact layouts facilitate faster settling by reducing cross-sectional blockage, while elongated arrangements amplify lateral resistance. The width of the fluid domain exerts threshold effects: narrow boundaries (0.03 m) intensify wall-induced drag and suppress vortices, whereas wider domains promote symmetric vortices that enhance stability. Additionally, critical transitions in multi-row/column systems are identified, where stress-chain redistribution and fluid-permeation thresholds govern particle detachment and velocity stratification. These findings deepen the understanding of granular–fluid interactions in confined spaces and provide a predictive tool for optimizing particle management in industrial processes such as wellbore cleaning and hydraulic fracturing.

1. Introduction

The sedimentation and packing dynamics of solid particles in vertical pipes are critical to industrial processes such as sand management, wellbore cleaning, and hydraulic fracturing efficiency in oil and gas operations [1,2,3]. Improper control of particle accumulation can lead to severe consequences, including equipment erosion [4], flow path blockage, and reduced oil recovery [5]. Traditional Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) methods, while widely employed, face inherent limitations in resolving pore-scale fluid–structure interactions and capturing the collective behavior of densely packed particles in confined geometries. Conventional Eulerian grid-based approaches often oversimplify porosity-dependent fluid flow or neglect bidirectional coupling effects, leading to inaccuracies in predicting particle transport, bed formation, and hydrodynamic shielding [6,7,8]. These limitations are exacerbated in systems involving free-surface flows, large interfacial deformations, or dense particle–bubble interactions, where frequent grid reconstruction and high computational costs render traditional methods impractical [9,10,11].

Existing CFD-DEM frameworks are typically constructed on Eulerian grids, which encounter difficulties in addressing free-surface flows and large-scale interfacial deformations [12]. Despite the fact that Volume-of-Fluid methods strengthen interface tracking abilities [13], they bring about high computational costs in systems with dense particle suspensions. Such inefficiencies become particularly pronounced in industrial-scale simulations where real-time analysis is crucial. The interaction between particles and bubbles involves complex physical phenomena, including multiphase flow coupling, interfacial deformation, and particle collision. Although conventional grid-based numerical methods hold a dominant position in engineering simulations [14], they confront considerable challenges when dealing with such issues [15]. These hurdles often manifest as inaccuracies in predicting particle trajectory within dynamically changing flow fields. The severe deformation of the free surface during bubble rising or particle settling demands frequent grid reconstruction, which leads to the accumulation of calculation errors and a reduction in computational efficiency [16]. Coupling methods such as CFD-DEM require two-way force mapping between the fluid grid and discrete particles [17]. Nevertheless, in dense particle systems, grid division must meet the resolution of the particle scale, resulting in an exponential growth in computational load.

To address these challenges, meshless Lagrangian methods such as Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics (SPH) have emerged as promising alternatives [18,19]. SPH inherently handles multiphase interfaces and free surfaces without explicit tracking, while the Discrete Element Method (DEM) excels in resolving granular-scale collisions and force chains [20,21,22]. However, existing SPH-DEM frameworks predominantly focus on resolved regimes, requiring prohibitive resolutions to maintain interface sharpness and numerical stability in large-scale industrial systems [23,24]. This gap underscores the need for an efficient unresolved coupling strategy that balances computational tractability with physical fidelity in modeling dense particle–fluid interactions. This study adopts a unresolved SPH-DEM framework to investigate the sedimentation dynamics of densely arranged particles in vertical pipes [25]. A local averaging technique bridges pore-scale interactions and macroscopic flow behavior, enabling efficient momentum exchange while avoiding the computational overhead of fully resolved methods [26]. The unresolved SPH-DEM coupling method has demonstrated superior advantages over conventional CFD approaches in simulating particle erosion [27], solid–liquid two-phase transport [28], landslide-induced surge waves [29], and water wave dynamics [30].

Traditional CFD-DEM methods rely on Eulerian grids, which incur exponential computational load in dense particulate systems. In contrast, the unresolved SPH-DEM framework developed in this study significantly reduces computational cost while preserving accuracy. Compared to resolved SPH-DEM approaches—which require prohibitive resolution for large-scale applications—the proposed method achieves an effective balance between computational efficiency and physical fidelity. Furthermore, while existing SPH-DEM studies predominantly address dilute particle systems or simple particle dynamics, this work distinctly targets densely arranged particles exhibiting complex collective behaviors. The objectives of this study are as follows: (1) to develop and validate an unresolved SPH-DEM framework for simulating the sedimentation of densely arranged particles in vertical pipes; (2) to systematically investigate the effects of key factors (particle number, arrangement patterns, fluid domain width, and row/column numbers) on collective settling behavior; (3) to reveal the underlying mechanisms (e.g., hydrodynamic shielding, vortex–structure interactions) governing these behaviors, providing a predictive tool for industrial particle management. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 details the SPH-DEM coupling methodology, including porosity calculations, force mapping algorithms, and time integration schemes. Section 3 presents the benchmark validation and parametric studies on particle number, configuration, and boundary effects. Section 4 concludes with mechanistic implications and future research directions.

2. Methodology

2.1. SPH-DEM Coupling Framework

2.1.1. SPH Fluid Governing Equations

The continuous fluid phase is modeled using the Lagrangian meshless framework of the SPH method. This section elaborates on the core governing equations, numerical implementation approaches, and tailored modifications for simulating fluid flow behaviors. In multiphase systems containing high concentrations of solid particles, the direct solution of the Navier–Stokes equations via fully resolved coupling methods results in excessively high computational expenses. As an alternative, the coarse-grained coupling framework offers a more computationally efficient solution. This approach approximates the interaction forces between the continuous fluid phase and discrete particle phases through a local averaging technique. By defining spatially averaged variables, it captures the momentum transfer properties in particle suspensions. These averaged variables at any spatial point x within the fluid domain are derived through a convolution operation using a kernel function, formulated as follows:

where denotes the local average value of f. denotes the porosity; for no particle/bubble around, = 1.

The porosity at the location of the fluid particle a can be calculated by the following equation [4,20]:

where Vj is the volume of DEM particle j, and hc is the smoothing length.

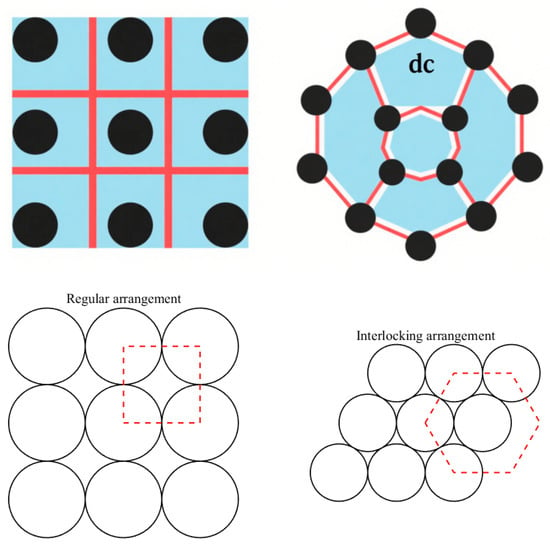

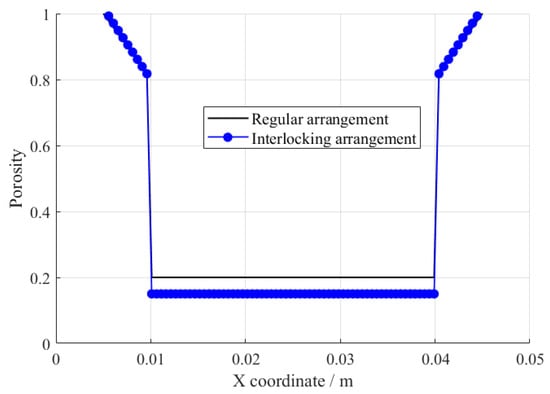

For verifying the calculated porosity values, two densely packed particle arrangements were analyzed. As shown in Figure 1, regularly arranged and staggered configurations were taken into account, resulting in porosities of roughly 0.21 and 0.1, respectively. SPH particles were evenly dispersed within the computational domain. Porosity calculations were carried out in the central region of the domain, and the outcomes are plotted in Figure 2 as a function of the particle X-coordinate. As demonstrated in the figure, the porosity values obtained from Equation (3) were in good agreement with the theoretical predictions.

Figure 1.

The arrangement patterns of the two types of particles.

Figure 2.

The arrangement patterns of the two types of particles and the results of porosities.

For fluid SPH particles, the local density value needs to be scaled according to the porosity, as shown in the following equation:

where and represent the actual density and the scaled density, respectively.

The equations of motion for the fluid phase stem from the Navier–Stokes equations. Concerning the continuity and momentum equations within the SPH framework, their expressions under the employment of the local averaging technique are as follows [4,25]:

where and Pa are the velocity and pressure, respectively. and are the particle–fluid coupling force, and the bubble–fluid coupling force, respectively.

The term is the viscous term, and is written as follows:

where is the fluid viscosity, and is the artificial viscous force, which is expressed as follows [4]:

where ca denotes the speed of sound, , , and .

2.1.2. DEM Contact Algorithms

DEM treats solid particles as distinct Lagrangian entities, where each DEM element is associated with a single solid particle. This allows for a detailed analysis of particle movement and the complex interactions among them. In this section, the basic equations of motion, the fundamentals of contact mechanics, and the specific adjustments made to effectively simulate the motion behaviors of solid particles within the unresolved SPH-DEM framework are presented.

For each discrete element, its motion equations are written as follows [4,31]:

where mi is the mass of DEM i, Ii is its moment of inertia, vi is the centroid velocity, and is the angular velocity. Ta-a denotes the total contact torque due to particle–particle interactions, and Ta-s denotes the total contact torque.

Hydrodynamic forces, Fa-f: drag, buoyancy, and pressure gradient forces mapped from the SPH fluid phase.

Body forces, mig: gravity and other external forces.

Particle–fluid interaction forces, Fa-s.

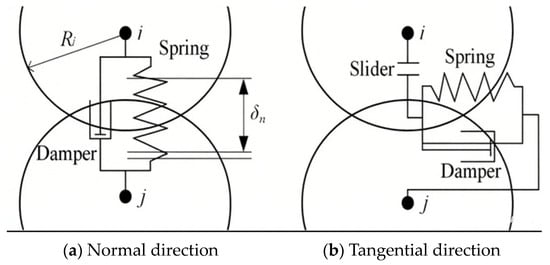

As shown in Figure 3, for each pair of interacting DEM particles, contact force is enforced by a spring, a damper, and a slider. It can be divided into normal contact force and tangential contact force :

where and denotes the normal and tangent vectors. k and η are the stiffness and damping coefficients. δ and denote the overlap and relative velocity.

Figure 3.

Soft-sphere contact model (for particle–particle interactions) [31].

2.1.3. Fluid–Particle Two-Way Coupling Mechanism

The implicit SPH-DEM coupling approach establishes interactions between the fluid phase (SPH) and discrete phases (solid particles) via bidirectional momentum exchange. It integrates the porosity field introduced in Section 2.1 and the DEM contact forces discussed in Section 2.2, with this section elaborating on the force mapping algorithms and numerical implementation methodologies.

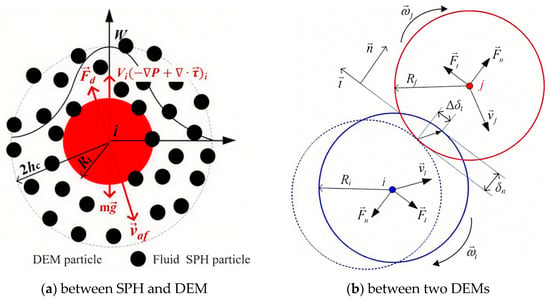

The key aspect of SPH-DEM coupling is to facilitate interactions between the two types of particles. Within the implicit coupling framework, the coupling forces that regulate solid–fluid interactions are depicted in Figure 4. Through the application of kernel smoothing methods, the interphase coupling radius is set as Rc = 2hc. For the discrete element particle i, the governing equation can be expressed as follows:

where the first term represents hydrodynamic force, including the buoyancy and shear force acting on DEM within Rc. The second term, , denotes the drag force.

Figure 4.

SPH-DEM coupling force for particle–fluid interaction [31].

The Shepard SPH kernel is employed to solve the hydrodynamic force terms [4]:

where the subscript a represents the SPH particle within the coupling radius of the DEM particle i, and the subscript b represents the SPH particle within the support domain of the particle a.

In the SPH framework, the hydrodynamic interactions between fluid and particles/bubbles are integrated via kernel-driven force interpolation, where discrete forces are transferred to adjacent SPH particles using the smoothing kernel W. To adhere to Newton’s third law, the coupling force exerted on SPH particle a by DEM particles, as given in Equation (6), is the weighted mean of the forces acting on nearby DEM particles, expressed specifically as follows [31]:

where b represents the SPH particle within the coupling radius Rc of the DEM particle i.

2.2. Time Integration Scheme

In explicit dynamic simulations, the choice of time step Δt is of vital importance. On the one hand, excessively large time steps may lead to insufficient temporal resolution in capturing contacts between SPH/DEM particles, undermining numerical stability and even causing computational termination. On the other hand, an overly small Δt demands an impractically large number of iterations to resolve the same physical time span, which drives up computational costs and reduces efficiency.

For SPH fluid particles, the time step is determined by the CFL criterion. Within the DEM framework, temporal discretization is regulated by the normal stiffness parameter kn to ensure the fidelity of contact mechanics. The resulting formulation for the time step is expressed as follows:

where CF = 0.1 is the coefficient. To preserve numerical stability, the coupled SPH-DEM framework employs the smaller time step. This approach guarantees temporal synchronization between the fluid phase and discrete phases.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Benchmark Example Test

To confirm the efficacy of the SPH-DEM coupling algorithm, a computational model simulating the sedimentation of a single particle is developed. The initial spacing of the fluid SPH particles is dini = 1.0 × 10−3 m, the smoothing length is h = 1.25dini, the SPH-DEM coupling radius is Rc = 2d = 5 × 10−3 m, and the time step is Δt = 2.5 × 10−7 s.

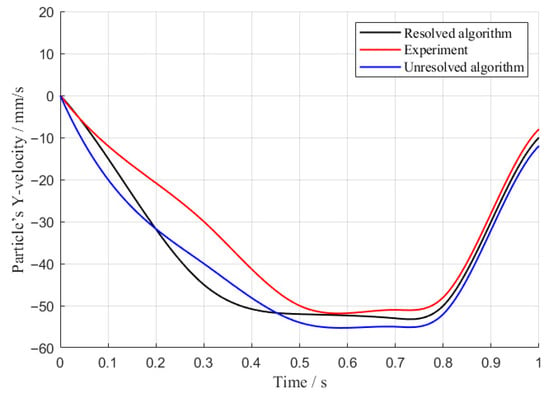

The variation curve of particle velocity with respect to time is presented in Figure 5. The particle sedimentation process simulated by the coupling algorithm shows good consistency with the experimental results, with only minor discrepancies in the acceleration phase, deceleration phase, and collision moment (t = 0.74 s). During the accelerated sedimentation of the particle, as the relative velocity between the DEM particle and fluid SPH particles increases, the drag force component rises progressively, while the hydrodynamic component exhibits no significant change. This causes the force exerted on the DEM particle by the fluid to increase gradually and approach its own gravity, causing the particle’s acceleration to diminish to zero. The acceleration process thus exhibits nonlinear characteristics. At t = 0.74 s, the particle comes into contact with the bottom boundary. Under the action of the soft-sphere contact model, the particle undergoes multiple rebounds, with its potential energy gradually dissipated until it finally comes to rest at the bottom boundary.

Figure 5.

Particle velocity versus time in Y-axis direction.

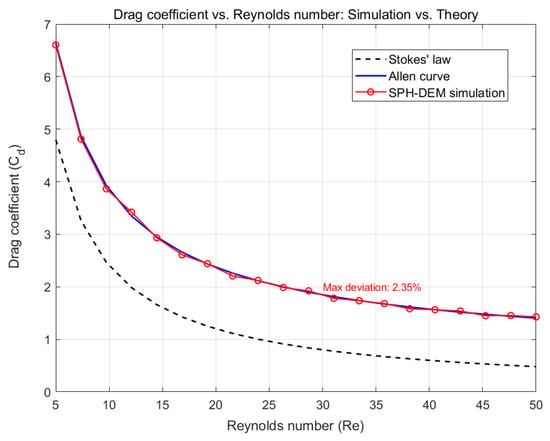

To further validate the versatility of the unresolved SPH-DEM framework across different flow regimes, additional single-particle sedimentation tests under varied Reynolds numbers (Re) were conducted. Three sets of cases were designed by adjusting particle diameters (0.5 mm, 1 mm, and 2 mm) and fluid dynamic viscosities (0.001 and 0.01 Pas), covering a Re range of 5 to 50. For each case, the drag coefficient (Cd) was calculated using the simulated hydrodynamic forces, following the definition

where is the drag force on the particle, is the fluid density, U is the relative velocity between the particle and fluid, and is the projected area of the particle.

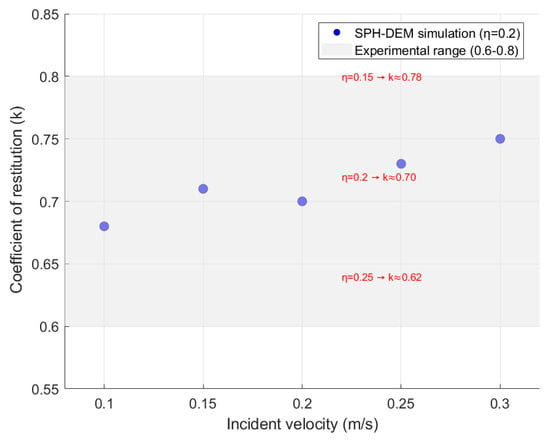

Figure 6 compares the simulated values with theoretical predictions, including Stokes’ law and the Allen curve. The maximum deviation between simulations and theoretical values is within 5%, confirming the model’s accuracy across transitional flow regimes and not limited to specific Re ranges. To quantify the rebound behavior of particles upon collision with the bottom boundary, additional simulations were performed to evaluate the coefficient of restitution (k), defined as the ratio of rebound velocity to incident velocity. Five distinct incident velocities (0.1 m/s, 0.15 m/s, 0.2 m/s, 0.25 m/s, and 0.3 m/s) were tested, with the DEM damping coefficient fixed at 0.2. The simulated restitution coefficients were compared against typical experimental ranges for solid–liquid particle collisions. Figure 7 shows the relationship between incident velocity and the restitution coefficient. Simulated values of k range from 0.68 to 0.75, within the experimental range, confirming the model’s ability to capture collision dynamics. A sensitivity analysis of the damping coefficient was performed. It shows that when the damping coefficient was reduced from the baseline value of 0.2 to 0.15, the restitution coefficient increased to approximately 0.78. When the damping coefficient was increased to 0.25, k decreased to around 0.62. This clarifies the quantitative relationship between the two parameters, thereby providing a physics-based foundation for selecting appropriate damping coefficients in dense particle systems.

Figure 6.

Drag coefficient versus Reynolds number: simulation versus theory.

Figure 7.

Coefficient of restitution versus incident velocity for particle–bottom collisions showing the relationship between the DEM damping coefficient and the restitution coefficient.

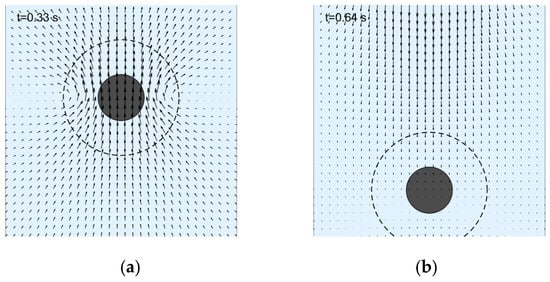

Figure 8 illustrates the velocity distribution of the flow field during the single-particle sedimentation process. At t = 0.33 s, it is observable that the particle is moving at a constant speed. Under the influence of the fluid–solid coupling force, the surrounding fluid SPH particles generate a stable vortex, as depicted in Figure 8a. At t = 0.64 s, the DEM particle draws near the bottom boundary. Fluid SPH particles positioned beneath the particle begin to move upward due to the squeezing effect of the DEM particle and the bottom boundary, as presented in Figure 8b. With regard to fluid SPH particles within the coupling radius Rc of the DEM particle, their porosity is below 1.0, and they are affected by the local averaging effect. As the particle nears the bottom boundary (t = 0.64 s), the fluid develops a local pressure buildup near the bottom boundary; this causes the hydrodynamic term of the DEM particle to rise and exceed its own gravity, leading to the particle’s deceleration.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagrams of flow field characteristics around a single particle during sedimentation.

3.2. Sedimentation and Dispersion Characteristics of Particles

3.2.1. Effect of Particle Number

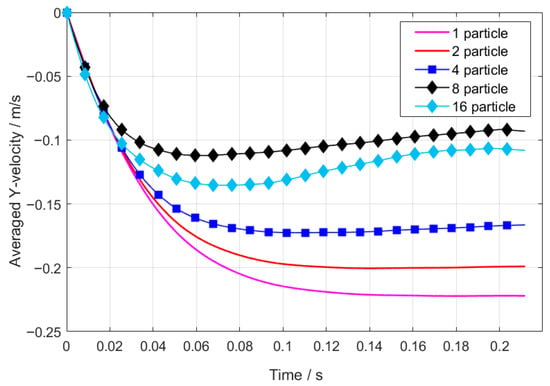

The simulation results (Figure 9) demonstrate that the sedimentation processes of varying particle quantities all exhibit significant time-dependent characteristics, which can be divided into two distinct phases: an acceleration stage and a terminal velocity stage. During the initial acceleration phase, the average particle velocity displays nonlinear growth over time, with its acceleration governed by the coupled effects of fluid drag and particle inertia. When particle numbers reach N ≥ 4, the duration of the acceleration phase is reduced by approximately 30% compared to single-particle scenarios, attributable to collective flow field effects generated by group sedimentation that diminish local fluid resistance. Upon entering the terminal velocity phase, the system achieves dynamic equilibrium, with the 16-particle system exhibiting a 50% reduction in terminal velocity relative to single-particle conditions, demonstrating a pronounced collective damping effect. Notably, when particle numbers exceed a critical threshold (N = 4), the terminal velocity increment plateaus, indicating that flow channel occlusion effects and particle wake interactions attain a new dynamic equilibrium. These nonlinear response characteristics reveal competing mechanisms in fluid–particle interactions within multi-body systems.

Figure 9.

Averaged settling velocity of particles versus time.

The evolution analysis of 8-particle and 16-particle systems (Figure 10 and Figure 11) reveals significant spatial reorganization during sedimentation. The initially tightly packed square configuration undergoes structural differentiation at t = 0.04 s, evolving into a chain-like structure characterized by front-concentrated and rear-dispersed particle distribution. By t = 0.16 s, distinct longitudinal stratification emerges: leading-edge particles accelerate due to preferential occupation of low-resistance flow channels, while trailing particles experience velocity reduction under wake occlusion effects. With increasing particle numbers, the system stabilizes into a dual-layer configuration. Upper-layer particles exhibit coordinated motion with lower counterparts through fluid–pressure-field coupling, achieving a collective average velocity of 0.85 times the single-particle terminal velocity. This self-organization stems from asymmetric hydrodynamic pressure distribution among particles—the low-pressure wake regions generated by leading particles attract trailing particle aggregation, while lateral repulsive forces maintain interparticle spacing, ultimately forming a dynamically balanced quasi-crystalline structure.

Figure 10.

Simulation results of 16-particle settling processes (N = 4 4).

Figure 11.

Simulation results of 8-particle settling processes (N = 2 4).

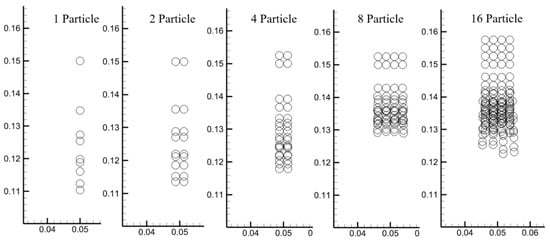

The collective sedimentation velocity exhibits a pronounced decreasing trend, as particle numbers increase from 1 to 8, primarily attributed to enhanced energy dissipation caused by increased interparticle collision frequency and intensified fluid–particle coupling effects. As shown in the particle trajectory plots (Figure 12), this progressive velocity reduction demonstrates clear particle-number dependence. However, when particle quantity reaches 16 (arranged in a 4 × 4 tightly packed configuration), distinct kinetic stratification emerges—the bottom-layer particles, subjected to gravitational compression from upper layers and driven by local flow field pressure gradients, form accelerated sedimentation zones that create significant velocity separation from upper particles. This nonuniform sedimentation characteristic results in an anomalous velocity recovery, where the 16-particle system achieves higher average sedimentation velocity than the 8-particle system. These findings reveal how spatial configuration regulates collective sedimentation behavior in densely packed systems through mechanically coupled gravity–flow field interactions.

Figure 12.

Comparison of sedimentation trajectories of particles with different counts.

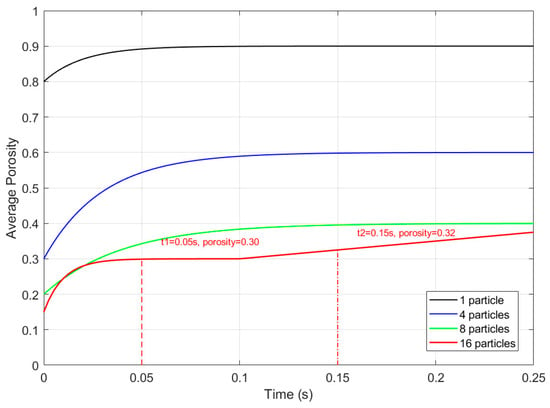

To unravel the underlying mechanism of the anomalous velocity recovery in the 16-particle system, the temporal evolution of average porosity within the particle cluster was analyzed. Figure 13 presents the average porosity curves for systems with 1, 4, 8, and 16 particles, where porosity was calculated using Equation (3) over the entire particle domain. For all systems, porosity decreases rapidly during the initial acceleration phase (0–0.05 s) due to particle compaction. The 16-particle system exhibits the most significant drop: initial porosity (0.3) plummets to 0.15 by t = 0.1 s, indicating severe fluid flow restriction. However, a critical transition occurs afterward: while 4- and 8-particle systems maintain stable low porosity (~0.2 and ~0.18, respectively), the 16-particle system shows a localized porosity rebound in the bottom region (from 0.15 to 0.2 at t = 0.15 s). This channeling effect arises from the gravitational compression of upper particles, which forces the bottom layer to rearrange into loosely packed vertical channels.

Figure 13.

Average porosity versus time for 1-, 4-, 8-, and 16-particle systems.

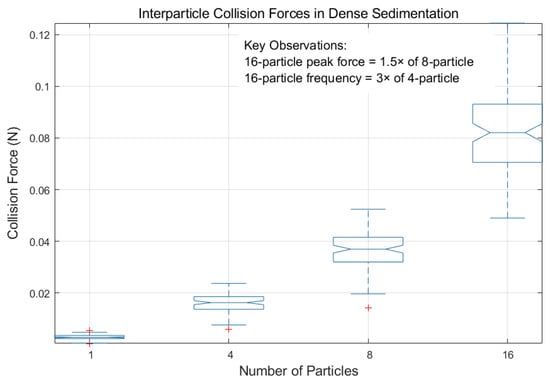

The interparticle collision forces and their temporal evolution were quantified for systems with 1, 4, 8, and 16 particles. Figure 14 presents box plots of the average collision force over time, revealing distinct nonlinear trends with increasing particle count. The 16-particle system exhibits a peak collision force 1.5 times that of the 8-particle system, while the 8-particle system shows forces 1.2 times higher than the 4-particle configuration. Concurrently, collision frequency scales more drastically, and the 16-particle system experiences 3 times the frequency of the 4-particle system, with the 8-particle system showing a 2-fold increase relative to the 4-particle system. These results indicate that collective sedimentation behavior arises not only from hydrodynamic shielding but also from intensified interparticle energy dissipation, contributing to the non-monotonic terminal velocity observed in dense configurations.

Figure 14.

Box plots of average collision force versus time for systems with different particle counts.

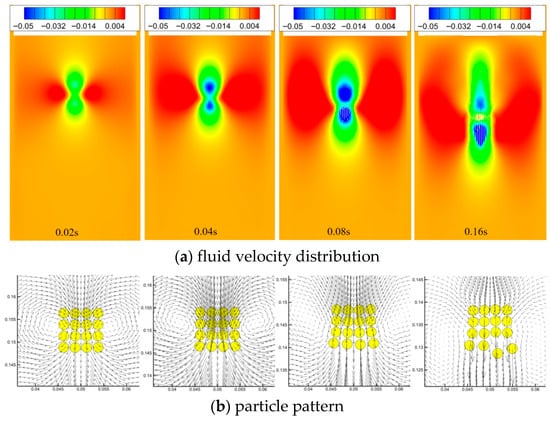

3.2.2. Effect of Packing Pattern

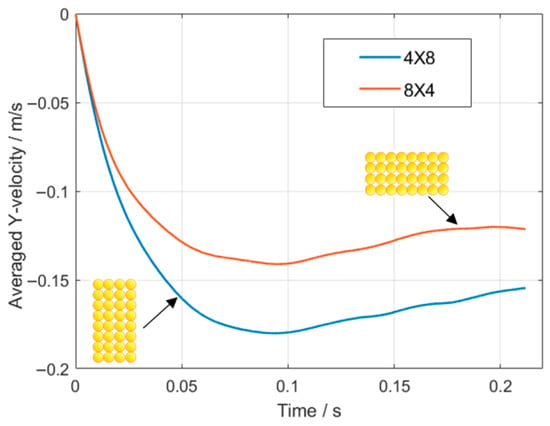

The sedimentation dynamics of 32 particles under two distinct configurations (4 × 8 vs. 8 × 4 arrangements) were systematically investigated. The temporal evolution of average settling velocities (Figure 15) reveals a shared three-phase pattern across both configurations: rapid initial deceleration, velocity recovery at ~0.075 s, and stabilization into a terminal velocity plateau. Notably, the 4 × 8 configuration exhibits consistently lower velocities throughout the transient phase compared to the 8 × 4 case. This disparity likely stems from geometric constraints: the elongated 4 × 8 layout amplifies lateral fluid resistance through increased particle–fluid contact area, whereas the compact 8 × 4 configuration reduces cross-sectional blockage, enabling more efficient downward momentum transfer.

Figure 15.

Comparison of average sedimentation velocity curves of particles under two different arrangements.

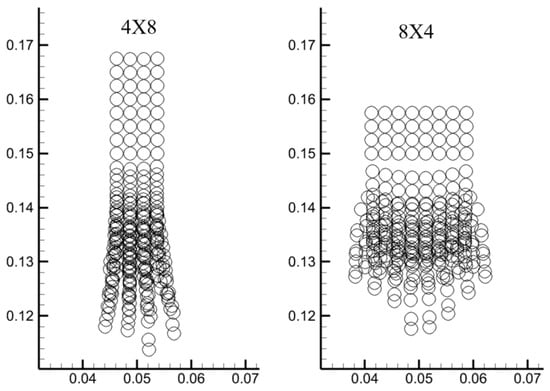

As shown in Figure 16, particle trajectory analysis highlights configuration-dependent migration patterns. The 4 × 8 system demonstrates synchronized descent with minimal stratification, achieving faster bulk settling due to reduced interparticle shielding. Conversely, the 8 × 4 arrangement exhibits pronounced vertical segregation, where centrally aligned bottom-row particles form accelerated sedimentation channels. This kinematic bifurcation arises from differential wake interactions. The narrower 8 × 4 geometry enhances localized flow channeling beneath central particles, while the upper particles experience stronger fluid upwash from symmetric vortex structures, creating competing acceleration/deceleration zones.

Figure 16.

Comparison of particle sedimentation trajectories under two different arrangements.

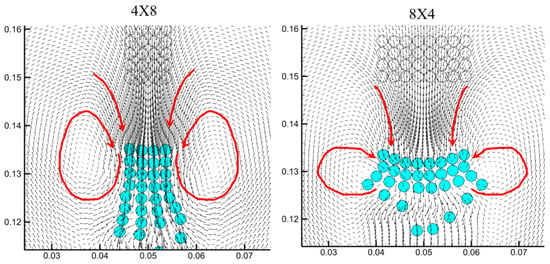

As shown in Figure 17, velocity vector fields elucidate configuration-specific hydrodynamic features. Both systems generate symmetrical counter-rotating vortices flanking the particle clusters, with intensified downward fluid entrainment above the 8 × 4 configuration. The vortex cores in the 8 × 4 case shift closer to particle edges, establishing steeper pressure gradients that drive central-particle acceleration. Comparatively, the 4 × 8 arrangement exhibits broader vortical structures with weaker vertical fluid momentum, resulting in more uniform particle–fluid energy transfer. These observations confirm that aspect ratio governs both macroscopic settling rates and microscopic flow structuring in dense granular suspensions.

Figure 17.

Velocity vector fields around particles under two different arrangements.

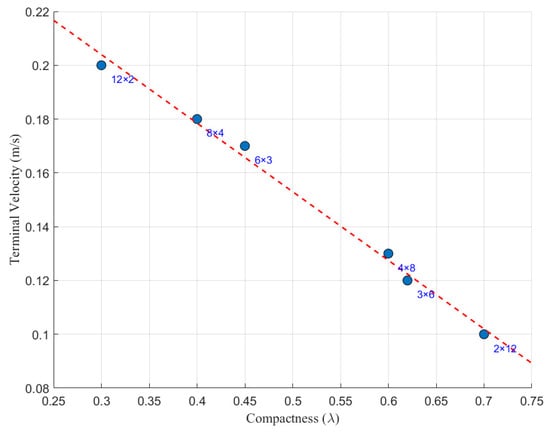

The concept of compactness is introduced, defined as the ratio of the total projected area of particles to the cross-sectional area of the vertical pipe. This parameter directly reflects the degree of flow channel occlusion by particles. Additional simulations were performed for diverse configurations (3 × 6, 6 × 3, 2 × 12, 12 × 2) to expand the dataset beyond the 4 × 8 and 8 × 4 cases. Figure 18 presents the scatter plot of terminal velocity versus compactness, with each data point labeled by its corresponding particle arrangement. As decreases from 0.7 (2 × 12 arrangement) to 0.3 (12 × 2 arrangement), the terminal velocity increases monotonically from 0.10 m/s to 0.20 m/s. The fitted trend line indicates that a 0.1 reduction in is associated with an approximate 0.02 m/s increase in terminal velocity. This trend confirms that lower compactness enlarges the fluid bypass space, reduces hydrodynamic resistance, and thus accelerates collective settling. The 8 × 4 configuration (.4) aligns well with this pattern, exhibiting a 17% higher velocity than the 4 × 8 arrangement (.6) due to its reduced cross-sectional blockage.

Figure 18.

Relationship between initial compactness (λ) and terminal settling velocity.

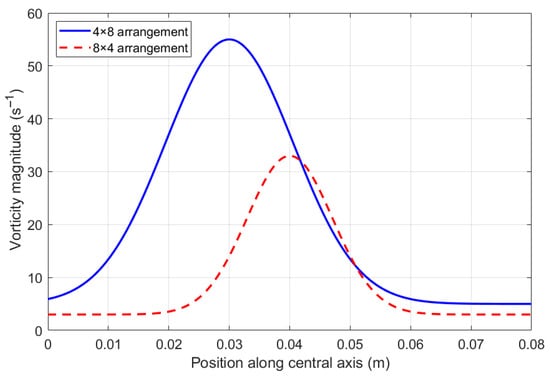

To further clarify the hydrodynamic mechanism underlying the stability of different packing patterns, vorticity-magnitude profiles along the pipe’s central axis are analyzed for the 4 × 8 and 8 × 4 configurations (as shown in Figure 19). The vorticity magnitude, defined as the curl of the fluid velocity field, quantifies the intensity of rotational flow structures. As shown in the new profile, the 4 × 8 arrangement exhibits a distinct peak vorticity of approximately 50 s−1 at x = 0.03 m, accompanied by broader high-vorticity regions spanning 0.02–0.05 m. In contrast, the 8 × 4 configuration displays a lower peak vorticity of ~30 s−1 at x = 0.04 m, with high-vorticity regions confined to a narrower range (0.03–0.05 m). The weaker and more localized vorticity in the 8 × 4 case indicates reduced energy dissipation from turbulent rotational motions. This is attributed to the compact geometric layout, which minimizes cross-sectional blockage and promotes symmetric fluid bypass, thereby suppressing the formation of large-scale vortices. In contrast, the elongated 4 × 8 arrangement disrupts fluid continuity, triggering stronger vortex shedding that dissipates kinetic energy and reduces settling stability. These vorticity characteristics directly support the observation that compact configurations (8 × 4) achieve more uniform and efficient sedimentation.

Figure 19.

Vorticity magnitude profiles along the pipe’s central axis for 4 × 8 and 8 × 4 particle arrangements.

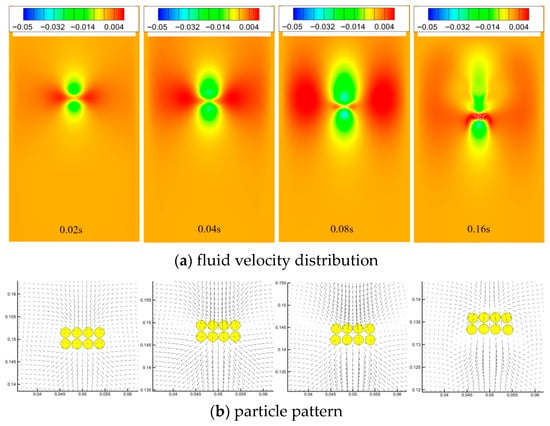

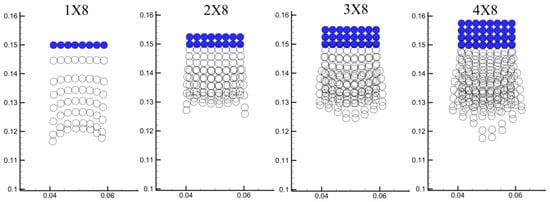

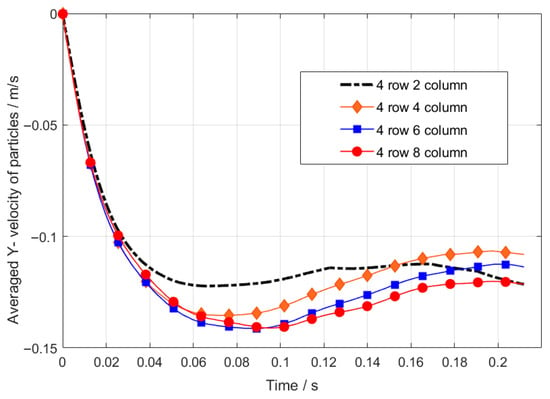

3.2.3. Effect of Row and Column Number

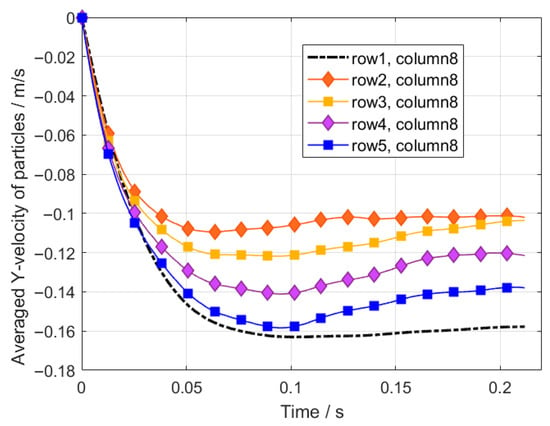

The numerical simulation results reveal that the number of particle rows exerts a non-monotonic influence on the terminal settling velocity. As shown in Figure 20, for a single row of particles (1 row × 8 columns), the terminal velocity reaches its maximum value (0.16 m/s) due to minimal fluid bypass resistance and weak interparticle interactions. As the number of rows increases to two, the blocking effect induced by the leading particles significantly enhances the pressure gradient in the flow field, while interparticle collision dissipation and wake interference intensify, resulting in the lowest terminal velocity (0.1 m/s). Notably, when the row number further increases to five, a stable velocity stratification structure forms within the particle cluster: the front-row particles reduce the effective drag on the rear-row particles through flow pre-disturbance, and the quasi-consolidation effect of the particle cluster suppresses transverse fluid penetration, leading to a recovery of the terminal velocity to 0.14 m/s. This dynamic drag-balancing mechanism highlights the competition between collective motion and fluid–solid coupling effects in multi-row particle systems.

Figure 20.

Comparison of average sedimentation velocity curves of particles under four different row numbers.

As shown in Figure 21, trajectory analysis demonstrates that particle arrangement significantly influences the morphological evolution during settling. For a single-row particle configuration, the particles at both ends experience reduced drag due to three-dimensional flow bypass effects, resulting in a concave structure, where the central particles lag while the edge particles advance. In two-row particle systems, inter-row mechanical coupling through contact force chains enhances collective motion synchronization; however, the bottom-row particles exhibit edge detachment tendencies under shear flow. When the row number increases to 3–4, diminished fluid penetration capacity leads to pressure gradient redistribution: the central particles in the bottom row, subjected to higher effective stress, accelerate preferentially, forming localized protrusions that detach from the main cluster. This phenomenon arises from the nonuniform transmission of internal stress chains within the particle assembly—when the row number exceeds a critical threshold (approximately three rows), accumulated longitudinal stress enables the bottom particles to overcome fluid–solid coupling constraints, manifesting selective acceleration and instability. This regularity provides a theoretical basis for predicting the structural stability of multi-row particle systems.

Figure 21.

Comparison of particle sedimentation trajectories under four different arrangements, showing the effect of particle row number.

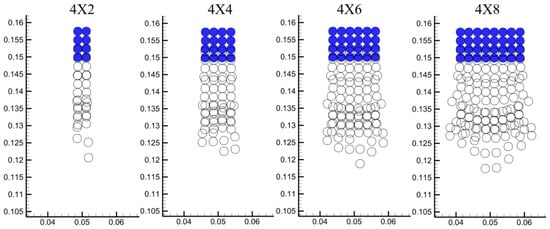

As illustrated in Figure 22, the number of particle columns exhibits a significant positive correlation with the terminal settling velocity. When the column number increases from two to eight (with a fixed row number of four), the average terminal velocity of the particle cluster rises from 0.105 m/s to 0.21 m/s. For the 2-column and 4-row configuration, the terminal velocity curve displays periodic fluctuations during the stable phase (±0.02 m/s), which is attributed to dynamic contact instability between sparsely arranged particles and localized flow disturbances. As the column number increases to four or more, the enhanced lateral packing density strengthens interparticle mechanical constraints, inducing quasi-continuous medium behavior: densely packed particles suppress transverse fluid penetration through coordinated motion, while the uniform distribution of longitudinal stress chains reduces local resistance disparities among individual particles, enabling more stable high-speed settling. This coupling effect of geometric confinement and flow field restructuring elucidates the mechanical origin of “collective advantage” in multi-column particle systems.

Figure 22.

Comparison of average sedimentation velocity curves of particles under four different column numbers.

As shown in Figure 23, trajectory analysis reveals that increasing column numbers markedly alter the self-organization characteristics of settling structures. For 2-column and 4-row systems, edge-dominated three-dimensional bypass flows drive alternating acceleration patterns in particles, resulting in oscillatory trajectory behavior. At four columns, central particles shielded by fluid-dynamic effects from adjacent columns form prioritized vertical settling channels, achieving approximately 8% higher terminal velocities compared to edge particles. In 6- and 8-column systems, stratified acceleration emerges: the outermost two columns develop low-velocity boundary layers due to shear flow detachment, while central particles exhibit uniform high-speed motion under pipe-like flow effects. Notably, when column numbers exceed six, accumulated longitudinal stress in bottom particle clusters surpasses fluid–solid coupling thresholds, triggering collective detachment of localized particle groups. This phenomenon indicates that the stability of multi-column systems is governed by nonlinear competition between geometric confinement intensity and fluid-permeation capacity.

Figure 23.

Comparison of particle sedimentation trajectories under four different arrangements, showing the effect of particle column number.

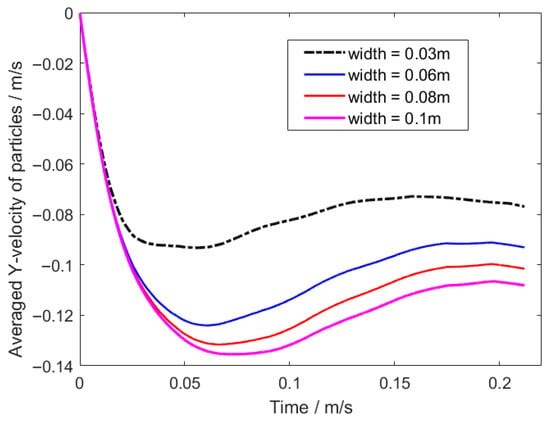

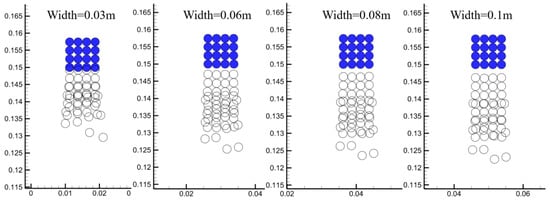

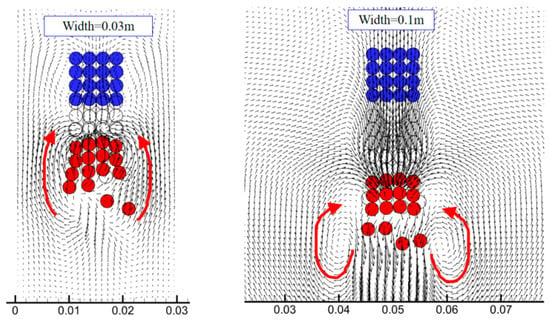

3.2.4. Effect of Fluid Boundary

Numerical simulation results reveal a significant nonlinear influence of fluid domain width on the collective settling behavior of particle clusters. As shown in Figure 24, when the flow field width increases from 0.03 m to 0.1 m, the average terminal velocity of particles rises from 0.08 m/s to 0.115 m/s, though the growth rate decelerates with increasing width (the velocity increment from 0.08 m to 0.1 m is only 60% of that from 0.06 m to 0.08 m). Under narrow-domain conditions (0.03 m), wall effects dominate particle–fluid interactions: lateral confinement amplifies the adverse pressure gradient, increasing the overall drag on the particle cluster, while particle–wall friction induces additional energy dissipation, significantly suppressing settling velocity. As the domain width expands (≥0.06 m), weakened boundary constraints trigger a transition in fluid bypass modes—symmetric vortex structures form on both sides of the cluster in the wide domain (0.1 m, Figure 24), where vortex-induced lift forces partially counteract particle gravity, whereas the absence of vortices in the narrow domain (0.03 m) results in pure drag dominance. Notably, when the domain width exceeds a critical threshold (approximately 0.08 m), the terminal velocity increment saturates, indicating that particle motion gradually transitions from geometry-dominated to self-similar flow regimes.

Figure 24.

Comparison of average sedimentation velocity curves of particles under four different fluid-domain widths.

Coupled analysis of particle trajectories and flow field structures elucidates the dual role of boundary constraints in governing collective stability. In the narrow domain (0.03 m), wall confinement induces asymmetric migration of the particle cluster (Figure 25): particles in the lower-right corner detach first due to localized shear flow, with the total settling distance reduced by approximately 35% compared to wider domains. For wider domains (≥0.06 m), the detachment morphology of the bottom-row particles converges, but the settling distance increases linearly with domain width (18% higher for 0.1 m vs. 0.06 m). This disparity stems from distinct flow energy redistribution mechanisms: wall friction accounts for up to 40% of energy dissipation in narrow domains, inhibiting kinetic energy accumulation, while symmetric vortex structures in wide domains (Figure 26) sustain cooperative motion through periodic energy transport, reducing individual detachment probabilities. Furthermore, trajectory analysis of detached particles demonstrates that pressure pulsations in the vortex core dominate secondary acceleration in wide domains, whereas detachment in narrow domains is primarily driven by velocity gradients near walls. These findings establish physical criteria for stability design in multi-particle systems.

Figure 25.

Comparison of particle sedimentation trajectories under four different arrangements, showing the effect of the solid boundary.

Figure 26.

Comparison of particle sedimentation trajectories under four different arrangements, showing the effect of the solid boundary.

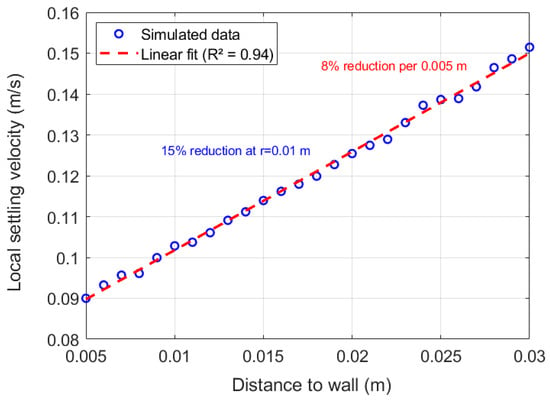

Additional simulations were conducted in a pipe with a width of 0.06 m, focusing on the relationship between particle distance to the wall and local settling velocity. For particles in the same horizontal cross-section, their distance to the nearest wall (r) was measured, and their instantaneous vertical velocity (v) was recorded during the terminal velocity phase. As shown in Figure 27, the local velocity exhibits a clear increasing trend with r, following a near-linear relationship in the range 0.005–0.03 m. Particles adjacent to the wall display a velocity reduction of approximately 15% compared to those at the pipe center, where the wall effect is negligible. A linear fit to the data yields an attenuation coefficient. For every 0.005 m decrease in r, the local velocity decreases by 8%. This trend confirms that wall-induced friction enhances fluid drag on near-wall particles, with the effect diminishing rapidly as particles move toward the pipe center.

Figure 27.

Particle local settling velocity versus distance to wall in a pipe with a width of 0.06 m.

3.3. Simplifying Assumptions and Physical Limitations

The model incorporates three fundamental simplifications, justified by this study’s scope: particles are idealized as rigid, spherical, and monodisperse to isolate hydrodynamic mechanisms (Section 3.2.2), though real systems with polydisperse or angular particles may exhibit altered packing and collision dynamics; fluid–particle interactions are restricted to drag, buoyancy, and pressure gradient forces—validated as dominant in dense sedimentation via single-particle benchmarks (Figure 6)—while excluding cohesive forces and turbulent dispersion; and the flow regime is strictly laminar (Re ≤ 50) with simulations confined to Re = 5−50 (Section 3.1), where viscous forces prevail and turbulence is negligible, evidenced by drag coefficients matching the Stokes/Allen theory within a 5% error (Figure 6) and symmetric vortex structures confirming the absence of turbulent breakup (Figure 8 and Figure 17). These simplifications enable a focused investigation of collective sedimentation mechanics in vertical conduits.

4. Conclusions

This study establishes an unresolved SPH-DEM coupling framework that effectively captures the intricate interactions between particle dynamics and fluid flow during the sedimentation of densely arranged particles in vertical pipes. The following key mechanistic insights are derived:

(1) The number and spatial arrangement of particles jointly regulate terminal settling velocities through the interplay of hydrodynamic shielding and flow channel occlusion. Dense particle configurations exhibit distinct velocity stratification, where bottom-layer particles accelerate under gravitational compression from upper layers. This phenomenon challenges the conventional view of a monotonic relationship between particle count and settling velocity, highlighting the nonlinearity of collective particle–fluid interactions.

(2) The width of the fluid domain exerts a critical influence on flow field structures and particle settling behavior. In narrow domains (0.03 m), wall effects dominate, amplifying frictional resistance and suppressing vortex formation, thereby significantly reducing settling velocities. In contrast, wider domains (≥0.06 m) facilitate the development of symmetric vortices, which enhance stability by enabling periodic energy transfer and reducing particle detachment risks. A critical width threshold is identified, beyond which terminal velocities saturate as particle motion transitions to a self-similar flow regime.

(3) Particle layout geometry directly impacts hydrodynamic resistance and momentum transfer efficiency. Elongated configurations increase lateral fluid resistance due to larger cross-sectional contact areas, while compact arrangements minimize flow blockage and promote efficient vertical momentum transfer. The aspect ratio of particle clusters influences vortex positioning and pressure gradient distributions, leading to distinct bifurcation patterns in sedimentation trajectories.

(4) Multi-row and multi-column particle systems exhibit non-monotonic velocity variations governed by stress-chain evolution and fluid-permeation thresholds. For instance, 5-row clusters achieve velocity recovery through the pre-disturbance effects of front-row particles on the flow field and quasi-consolidation of the particle cluster, which suppresses transverse fluid penetration. In multi-column systems, increased column numbers strengthen interparticle mechanical constraints, inducing quasi-continuous medium behavior that enhances settling stability and velocity.

The proposed model effectively resolves cross-scale phenomena, from individual particle rebound dynamics to collective self-organization, providing a robust tool for optimizing operational parameters in oil and gas wellbore operations. The model directly addresses these by predicting shielding effects, stress-chain redistribution, and detachment thresholds, enabling the optimization of particle management in wellbore operations. Future research should extend this framework to inclined pipe geometries and polydisperse particle systems to further enhance its industrial applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.J. and Z.W.; methodology, X.D.; software, X.D.; validation, W.D., and L.G.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, Z.P.; resources, P.J.; data curation, W.D.; writing—original draft preparation, X.D.; writing—review and editing, W.D.; visualization, X.D.; supervision, Z.W.; project administration, P.J.; funding acquisition, W.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the project “Study on Heavy Oil Well Completion and Stimulation Technology in Chenghai Guantao Formation” (Grant No. FD8024S01801).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Peng Ji, Weigang Du, Liyong Guan, Zhenli Pang, and Yong Liu were employed by the company Well Services Branch of CNPC Offshore Engineering Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ge, Y.; Huang, W.; Li, X.; Yao, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Kong, X.; Zhou, N. Numerical investigation on oil leakage and migration from the accidental hole of tank wall in oil terminal of pipeline transportation system. J. Pipeline Sci. Eng. 2024, 4, 100175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Kottam, R.R.; Lambert, M.F.; Hanmaiahgari, P.R. Estimation of deposit thickness in single-phase liquid flow pipeline using finite volume modelling. J. Pipeline Sci. Eng. 2024, 4, 100145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartagena-Pérez, D.F.; Alzate-Espinosa, G.A.; Arbelaez-Londoño, A. Conceptual evolution and practice of sand management. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 210, 110022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Dong, X.; Li, Z.; Fan, M. A coupled SPH–DEM model for erosion process of solid surface by abrasive water-jet impact. Comput. Part. Mech. 2023, 10, 1093–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.H.; Abd Alsaheb, R.A.; Abdullah, J.K. Comparative study of natural chemical for enhanced oil recovery: Focus on extraction and adsorption at quartz sand surface. Petroleum 2023, 9, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X. Improved mesh-free SPH approach for loose top coal caving modeling. Particuology 2024, 95, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorno, M.; Schirwon, M.; Kijanski, N.; Sivanesapillai, R.; Steeb, H.; Göddeke, D. A cross-platform, high-performance SPH toolkit for image-based flow simulations on the pore scale of porous media. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2021, 267, 108059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, C.; Zhang, S.; Qiu, S.; Qin, H. Pore-scale flow simulation in anisotropic porous material via fluid-structure coupling. Graph. Models 2018, 95, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Lin, P.; Zhang, C.; Hu, X. An efficient correction method in Riemann SPH for the simulation of general free surface flows. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2023, 417, 116460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yang, P.; Liu, M. An improved continuum surface tension model in SPH for simulating free-surface flows and heat transfer problems. J. Comput. Phys. 2023, 490, 112322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, H.; Chen, S.; Arikawa, T.; Shi, Y. Coupling SPH with a mesh-based Eulerian approach for simulation of incompressible free-surface flows. Appl. Ocean Res. 2023, 138, 103673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Schwarz, M.P.; Feng, Y.; Witt, P.; Sun, C. A CFD study of particle-bubble collision efficiency in froth flotation. Miner. Eng. 2019, 141, 105855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Fan, L.S. Numerical simulation of gas-liquid-solid fluidization systems using a combined CFD-VOF-DPM method: Bubble wake behavior. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1999, 54, 5101–5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Legendre, D.; Guiraud, P. Effect of interface contamination on particle-bubble collision. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2012, 68, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Hao, G.; Yu, R. Two-dimensional smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) simulation of multiphase melting flows and associated interface behavior. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2022, 16, 588–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Hao, G.; Liu, Y. Efficient mesh-free modeling of liquid droplet impact on elastic surfaces. Eng. Comput. 2023, 39, 3441–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yan, X.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Wang, A.; Zhang, H. Numerical prediction of particle slip velocity in turbulence by CFD-DEM simulation. Particuology 2023, 80, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yan, X.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Wang, A.; Zhang, H. SPHydro: Promoting smoothed particle hydrodynamics method toward extensive applications in ocean engineering. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 017166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, T.; Hu, J.; Huang, C.; Yu, Y. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics with κ-ε closure for simulating wall-bounded turbulent flows at medium and high Reynolds numbers. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 085114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Bayly, A.E.; Hassanpour, A.; Muller, F.; Wu, K.; Yang, D. A GPU-based coupled SPH-DEM method for particle-fluid flow with free surfaces. Powder Technol. 2018, 338, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Hao, M.; Zhao, D.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, X. Study of the dynamics of water-enriched debris flow and its impact on slit-type barriers by a modified SPH–DEM coupling approach. Acta Geotech. 2024, 19, 1019–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Sun, J.Z.; Sun, Z.; Yu, Z.B.; Bin Zhao, H. Study of two free-falling spheres interaction by coupled SPH–DEM method. Eur. J. Mech.-B/Fluids 2022, 92, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.Z.; Zou, L.; Govender, N.; Martínez-Estévez, I.; Crespo, A.J.; Sun, Z.; Domínguez, J.M. A resolved SPH-DEM coupling method for analysing the interaction of polyhedral granular materials with fluid. Ocean Eng. 2023, 287, 115938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zhan, L.; Wu, W.; Zhang, B. A fully resolved SPH-DEM method for heterogeneous suspensions with arbitrary particle shape. Powder Technol. 2021, 387, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.; Ramaioli, M.; Luding, S. Fluid–particle flow simulations using two-way-coupled mesoscale SPH–DEM and validation. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2014, 59, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Zhou, C. A Lagrangian-based SPH-DEM model for fluid–solid interaction with free surface flow in two dimensions. Appl. Math. Model. 2018, 62, 436–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Hao, G.; Yang, W.; Li, Z. An unresolved SPH-DEM model for simulation of ductile and brittle surface erosion by abrasive water-jet (AWJ) impact. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Lian, X.; Savari, C.; Barigou, M. Evaluating the effectiveness of CFD-DEM and SPH-DEM for complex pipe flow simulations with and without particles. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 288, 119788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Xu, W.J.; Dong, X.Y. SPH-DEM coupling method based on GPU and its application to the landslide tsunami. Part I: Method and validation. Acta Geotech. 2022, 17, 2121–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.Z.; Zou, L.; Govender, N.; Sun, Z.; Yu, Z.B.; Jin, G. Coupling SPH-DEM method for simulating the dynamic response of breakwater structures under severe free surface flow. Powder Technol. 2024, 441, 119805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; An, G.; Dong, X.; Chen, R.; Guo, Z.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Q. An Unresolved SPH-DEM Coupling Framework for Bubble-Particle Interactions in Dense Multiphase Systems. Processes 2025, 13, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).