Abstract

Maping Phosphate Mine operates as a large-scale mining complex characterized by a multi-mining area strip mining layout. This configuration exhibits expansive operational zones, numerous dispersed mining sites, and inherent systemic complexity, collectively complicating ventilation system management. The optimization of ventilation processes across multiple mining areas constitutes a critical measure for enhancing operational safety and efficiency within resource-constrained scenarios. This investigation specifically targets four adjacent mining zones—340B, 380B, 380C, and 420D—where three distinct ventilation schemes were formulated and evaluated. A process-oriented simulation-optimization model combining Ventsim and TOPSIS was developed to evaluate the ventilation systems. The ventilation network architecture and airflow distribution characteristics of the target mining areas were comprehensively simulated, establishing a decision optimization framework for the ventilation system that successfully identified the optimal solution. The results demonstrate minimal error between the simulated and measured data of the mine ventilation network model, validating the accuracy of its system parameter estimations. Simulations of diverse ventilation schemes generated airflow distribution parameters and dust concentration data for each mining area. Subsequently, a TOPSIS-integrated process optimization model was developed to comprehensively evaluate the ventilation schemes against eight quantitative indicators. Evaluation results identified Scheme Two as the optimal solution, as it demonstrates a balanced optimization of safety, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness. This scheme achieves a significant enhancement of the underground ventilation environment and a marked suppression of dust diffusion, with only a marginal increase in overall ventilation costs. By elevating the air volume from an initial less than 1.0 m3/s to a precisely regulated range of 5.0–13.0 m3/s, the scheme fundamentally eliminated ventilation dead zones. This intervention resulted in a significant reduction in dust concentrations across multiple working faces, consistently maintaining levels below the 4 mg/m3 national exposure limit (GBZ 2.1-2019), and ultimately ensured a safer and healthier working environment. The attainment of these practical outcomes, which directly correspond to the optimization objectives of the TOPSIS method, confirms its efficacy and practical value in guiding ventilation strategy selection.

1. Introduction

The growing complexity of mining layouts, characterized by multi-area simultaneous operation and deeper extraction, has intensified ventilation demands, making issues like uneven airflow distribution more severe. System simulation technology has therefore become a pivotal approach for optimizing the mine ventilation network to enhance efficiency and secure underground working conditions [1,2,3,4]. In the field of mine ventilation research, Ren [5], Hussein [6], and Maleki et al. [7] applied simulation software to optimize the ventilation circuit, significantly reducing the harm of polluted air to the working face. Wang [8], Zhang et al. [9] and Sun et al. [10] optimized the air network structure through Ventsim software (Ventsim 5.0), achieving a reduction in ineffective air volume and control of ventilation resistance. Guo [11] and Liang et al. [12] verified the effectiveness of active long-wall wallboard isolation in suppressing spontaneous combustion in goaf. Roy et al. [13] and Yang et al. [14] achieved dynamic prediction of thermal stress conditions in mines using the developed 3D model. Paluchamy et al. [15] created a 3D model to study the transport of air particulate matter. Hu et al. [16] constructed a ventilation network model based on FLUNET. The influence mechanisms of inlet wind speed, roof roughness, etc. on wind speed distribution were systematically studied. Wang et al. [17], Yao et al. [18], and Du et al. [19] based on the FLUENT platform, revealed through simulation the influence mechanism of the ventilation mode of the working face in the mine ventilation system on the air flow movement law and dust distribution, jointly promoting the improvement of the multi-parameter collaborative regulation theory of the mine ventilation system. Shao et al. [20] reduced the total energy consumption of ventilation by introducing the particle swarm optimization algorithm and proposed a new intelligent algorithm to calculate the optimal air volume of the roadway. However, existing simulation studies predominantly focus on analyzing the mechanisms of local ventilation characteristics or optimizing individual, established ventilation networks. There is still a gap in research regarding global dynamic simulations that examine the dynamic coupling and interference effects of airflow across various subsystems, particularly under conditions of parallel mining in multiple mining areas.

TOPSIS is utilized as a multi-objective decision-analysis tool for the comprehensive evaluation of mine ventilation system schemes. The optimal solution is determined through a comparative assessment of alternatives, and valuable decision support for optimization is generated, highlighting the method’s wide applicability. Specifically, Bao [21] constructed a multi-level TOPSIS evaluation model based on the entropy weight method, conducted a comprehensive evaluation of the ventilation systems in multiple mining areas, and thereby improved the ventilation systems in mines. Zhang et al. [22] used the TOPSIS method to evaluate the reliability of ventilation systems and summarized six key factors affecting the reliability of mine ventilation systems. Wang [23], Deng et al. [24], and Xu et al. [25] applied the AHP-TOPSIS evaluation model, effectively solving problems such as the imperfect index system and the difficulty in quantitatively assessing safety in the mine ventilation system.

The multi-mining area operations at Maping Phosphate Mine face challenges such as low ventilation efficiency and insufficient airflow in certain areas, particularly with safety risks like the circulation of polluted air and dust accumulation. A three-dimensional simulation model of the ventilation system for the target area was constructed using Ventsim software. Multiple ventilation schemes were subsequently designed, and their performance parameters were systematically assessed through simulation. A TOPSIS-based optimization model was developed to systematically evaluate and refine the multi-objective ventilation schemes. The most effective solution for coordinated ventilation across multiple mining areas was thereby identified, providing systematic theoretical support and practical technical guidance for the optimization of complex mine ventilation systems.

2. Overview of the Ventilation System of Maping Phosphate Mine

Located in Yuan’an County, Hubei Province, Maping Phosphate Mine boasts proven phosphate rock reserves of about 315 million tons, averaging a grade of 27.38%. The ore body is geologically defined as a gently inclined, thin deposit, extending over an area of 14.79 km2. The ventilation system at Maping Phosphate Mine employs a two-wing diagonal mechanical exhaust configuration. The primary ventilation is supplied by the main fan for the entire mine network, with auxiliary ventilation in specific working areas being provided by local fans. Based on the required airflow and negative pressure calculations for both the easy and difficult ventilation periods, one FBCDZ-10-No. 34 (Zibo Fan Factory Co., Ltd., Zibo, China) type mine counter-rotating axial flow fan, certified with the mine product safety mark, was specified for each of the No. 1 and No. 2 ventilation fan rooms. Each ventilation fan is configured with two YX3-630-10 (IP55) motors (Xi’an Taifu Sima Electric, Xi’an, China), with an identical spare motor maintained for backup. The technical parameters of the main ventilation equipment are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Selection and calculation of main ventilation equipment.

3. Modeling and Simulation of Mine Ventilation System

3.1. Modeling of Ventilation Simulation System

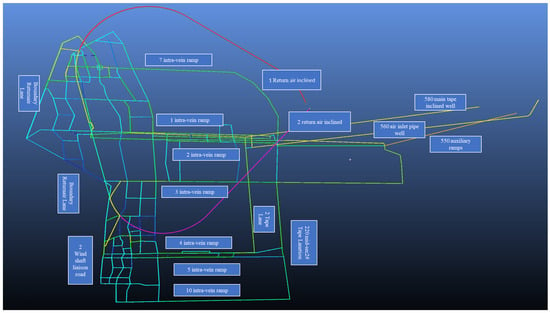

The centerlines of the main roadways were extracted from the mine ventilation network diagram utilizing three-dimensional polyline features in CAD software 2024. These were subsequently employed to construct the physical model of the overall ventilation system for Maping Phosphate Mine. The model was subsequently imported into Ventsim software for the purpose of generating the three-dimensional physical model of the mine ventilation system, the results of which are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Simulation model of ventilation throughout the Maping Phosphate Mine.

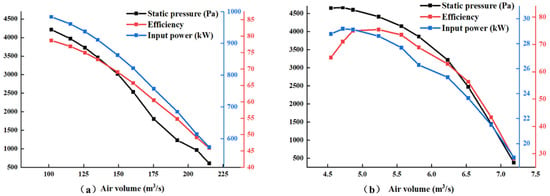

Based on the ventilation system layout of the Maping Phosphate Mine, FBCDZ-10-No. 34 main fans were installed at the ends of the No. 1 and No. 2 Return air inclined in the constructed model. The corresponding technical specifications are summarized in Table 1, and the fan characteristic curves are presented in Figure 2a. Local ventilators (Model FBD-NO5.6/2×15) were installed in Panel Area 2 and Panel Area 8, with three and four units deployed, respectively. The characteristic curves of the fans, based on data provided by Ping An Electrical Appliance Company (Xiangtan, China), are shown in Figure 2b. Subsequently, all necessary parameters for the simulation were defined within the Ventsim software environment.

Figure 2.

(a) Characteristic curves of the main ventilator; (b) Characteristic curves of the local ventilator.

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Simulation and Actual Measurement

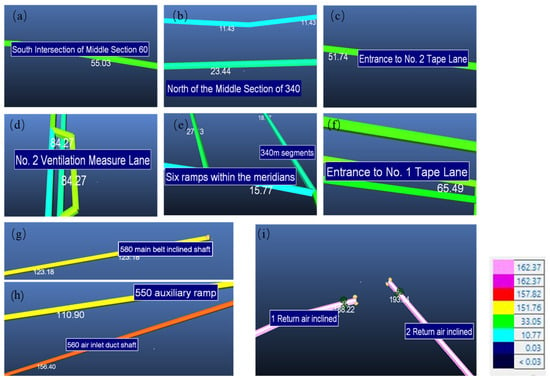

The ventilation network calculation yielded the airflow distribution for each branch. The resulting air volumes in the intake and return air inclined shafts and several roadways are shown in Figure 3, with the corresponding comparison to measured data detailed in Table 2.

Figure 3.

(a) Air volume of South intersection of Mid- Section 60; (b) Air volume of North of the Middle Section of 340; (c) Air volume of Entrance to No.2 Tape Lane; (d) Air volume of No.2 Ventilation Measure Lane; (e) Air volume of Six ramps within the meridians; (f) Air volume of Entrance to No.1 Lane; (g) Air volume of 580 main belt inclined shaft; (h) Air volume of 550 auxiliary ramp and 560 air inlet dust shaft; (i) Air volume of 1 Return air inclined and 2 Return air inclined.

Table 2.

Summary table of measured and simulated air volumes in the main intake and return shafts and tunnels.

The ventilation network model shows high consistency between simulated and measured air volumes, with relative errors for total intake and return air volumes both below 4%, confirming the model’s reliability and providing a basis for further ventilation optimization. The presence of localized errors, such as those approaching or exceeding 10% at the intersection of the South 220 and North 340 mid-range, along with notable deviations at the entrance of Belt Lane No. 1, does not invalidate the model. Rather, these discrepancies provide critical insights for identifying areas requiring further investigation or system adjustment. These discrepancies are concentrated in the most complex zones of the ventilation network, specifically where resistance characteristics are poorly quantified or facility conditions are highly dynamic. The pronounced errors are primarily attributed to the underestimation or oversimplification of local resistance in the model.

Therefore, these error data provide a valuable basis for calibrating the model and enhancing its accuracy. The aforementioned areas should be designated as priority targets for subsequent investigation. The model parameters can be calibrated by on-site re-measurement of roadway resistance coefficients, precise mapping of cross-sectional dimensions, and verification of air door opening degrees and integrity. This process enables the model to iteratively approximate the operational characteristics of the actual ventilation system. Through iterative calibration against field data and parameter optimization, the model evolves to achieve greater predictive accuracy and practical utility in engineering applications.

4. Ventilation System for Multi-Mining Areas

4.1. Overview of the Stope Ventilation System

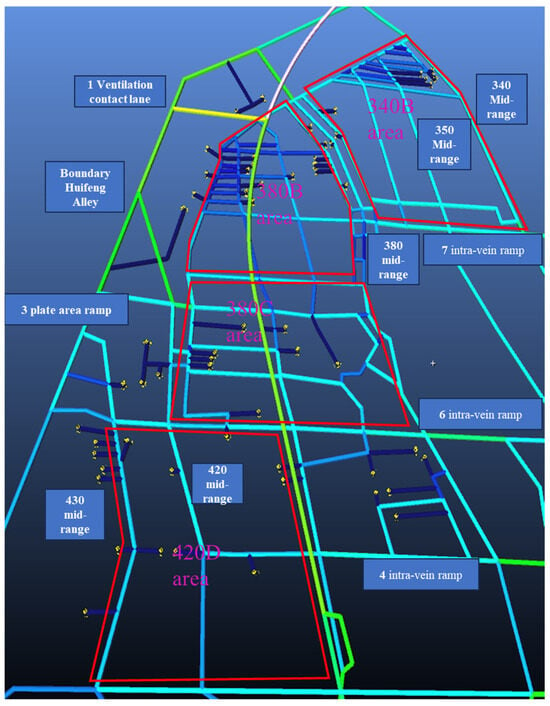

The study area encompasses four mining zones: the 340B, 380B, 380C, and 420D test mining zones, as detailed in Figure 4. Within this area, mechanical forced ventilation is employed for all mining and excavation activities. Fresh air is introduced into the mining site via the 580 Main Belt Inclined Shaft, 550 Auxiliary Ramp, 560 Intake Pipe Cable Shaft, and the 220 mid-range. It then flows sequentially through the 6 and 7 intra-vein ramps into the northern range of the 340 and 380 mid-range. After ventilating the working faces, the contaminated air is exhausted to the surface by the main fan through the Boundary return air roadway, the No. 1 Ventilation Connection Duct, and finally the No. 1 return air inclined Shaft.

Figure 4.

Study the regional model and the distribution of mining areas.

Current multi-stage development at the Maping Phosphate Mine has resulted in systemic issues, including low ventilation efficiency and disorganized airflow distribution in specific areas. These challenges are particularly evident in three mining zones: the 340B test mining zone (located north of the ramp in the No. 2 coil area), the 380B test mining zone (situated north of the No. 7 intra-vein ramp, between the 400 and 420 range), and the 380C test mining zone (found north of the ramp in the No. 3 coil area).

These ventilation issues result in excessively high dust concentrations in localized areas, which pose serious health and safety risks to workers. Consequently, there is an urgent need to optimize the ventilation systems in these areas to effectively suppress dust and prevent hazardous accumulation. Rational airflow distribution guarantees sufficient ventilation in working areas, thereby creating a safer environment, reducing health risks, and ensuring overall mine safety and operational efficiency [26,27].

4.2. Feasible Solution

Based on a diagnosis of the existing ventilation systems in the four mining areas, which identified problems including uneven air distribution and high resistance, three feasible mitigation schemes are proposed.

4.2.1. Ventilation System Scheme One

- (1)

- In Area 340B, the scheme includes: a K-8-No. 19 auxiliary fan installed north of the Block 2 ramp; temporary seals on the boundary transport roadway (north of B5) and the 340 mid- section (above Block 2 ramp); and an FBD-No. 5.6/2×15 local ventilator for the B2 strip, fitted with a Ø500 mm positive-pressure rubber antistatic flame-retardant air duct, as shown in Figure 5.

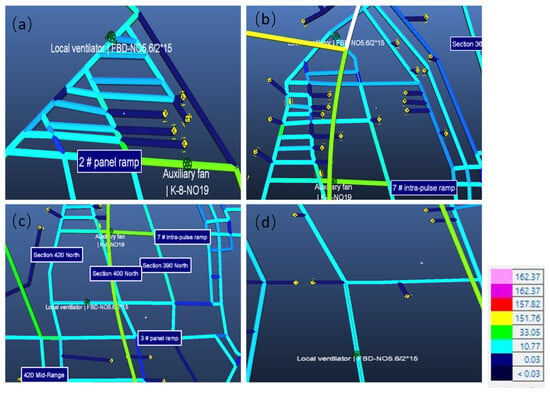

Figure 5. (a) Area 340B Optimization Plan for mining Area One; (b) Area 380B Optimization Plan for mining Area One;(c) Area 380C Optimization Plan for mining Area One; (d) Area 420D Optimization Plan for mining Area One.

Figure 5. (a) Area 340B Optimization Plan for mining Area One; (b) Area 380B Optimization Plan for mining Area One;(c) Area 380C Optimization Plan for mining Area One; (d) Area 420D Optimization Plan for mining Area One. - (2)

- In Area 380B, the scheme implements: a K-8-No. 19 auxiliary fan on the inner slope of No. 7 intra-vein ramp (above 390 mid-range); automatic air doors on range north of Section 400 (above B5 and B9 strips); and adjustable air windows on the boundary transport roadway (above B6 strip) and north of Section 400 (north of the No. 7 intra-vein ramp), with areas set to 10 m2 and 6 m2, respectively.

- (3)

- In Area 380C, an FBD-No. 5.6/2×15 local ventilator is installed on the C5 strip, connected to a Ø500 mm positive-pressure rubber anti-static flame-retardant air duct.

- (4)

- In Area 420D, an FBD-No. 5.6/2×15 local ventilator is installed north of the 420 mid- section (north of the inner ramp of No. 1 vein), also employing a Ø500 mm positive-pressure rubber anti-static flame-retardant air duct.

4.2.2. Ventilation System Scheme Two

- (1)

- In Area 340B, the scheme implements: a K-8-No. 19 auxiliary fan north of the 340 mid- section (boundary transportation lane) to temporarily seal the lane north of the B5 strip; and regulating air windows in the boundary transportation lane (above B2 strip) and the 340-bottom lane (above B1 strip), with areas set at 4 m2 and 8 m2, respectively.

- (2)

- In Area 380B, the scheme includes a K-8-No. 19 auxiliary fan installed north of Section 420 (above the B9 strip), and an FBD-No.5.6/2×15 local ventilator on the B5 strip, connected to a Ø500 mm positive-pressure rubber anti-static flame-retardant air duct.

- (3)

- In Area 380C, a 4 m2 adjustable air window is installed on the C5 strip (above Section 390).

- (4)

- In Area 420D and the 430 mid- range (north of the inner slope of Vein No. 1), adjustable air windows, each with an area of 4 m2, are installed.

4.2.3. Ventilation System Scheme Three

- (1)

- In Area 340B, a K-8-No. 19 auxiliary fan is installed north of the 340 mid- range (north of the boundary transportation roadway); additionally, a 10 m2 regulating air window is placed above the B1 strip of this roadway.

- (2)

- In Area 380C, a K-8-No. 19 auxiliary fan is installed on the north side of Range 420 (south of the inner ramp of the 7th vein) to temporarily seal the area above Range 420 (covering the B5 and B9 strips).

- (3)

- In Area 420D, an FBD-No. 5.6/2×15 local ventilator is installed in the 420 mid- range (north of the No. 1 internal ramp), connected to a Ø500 mm positive-pressure rubber anti-static flame-retardant air duct.

4.3. Analysis of Ventilation Effect in the Mining Area

Simulations of the three ventilation schemes produced results for the air volume distribution in each roadway of the optimized network, as detailed in Table 3. This resultant data establish a precise basis for the comparative analysis and subsequent decision-making regarding ventilation scheme optimization.

Table 3.

Data comparison table of Three ventilation Schemes in the mining area.

Simulations show marked improvements in airflow uniformity across most roadways under all three schemes. Total intake air volumes rise significantly to 121.33 m3/s, 115.98 m3/s, and 119.01 m3/s for Schemes One, Two, and Three, respectively, along with proportional increases in total return air volume.

Each scheme employs a unique airflow regulation strategy. Scheme One features significant, region-specific increases combined with cautious supplemental adjustments in others. Scheme Two is characterized by further environmental optimization in priority areas, offset by deliberate airflow reductions in non-critical zones. Conversely, Scheme Three pursues a balanced approach, achieving a moderate overall increase through relatively uniform adjustments across all regions.

4.4. Dust Analysis in the Mining Area

A comprehensive analysis of the mining area layout and working face distribution was performed to study dust diffusion patterns and control strategies within the ventilation system. Subsequently, dust generation sources were pinpointed in three critical areas undergoing mining and excavation activities: namely, the B4 strip in Area 340B, the B8 strip in Area 380B, and the ramp of the No. 4 coil in Area 420D. Based on the analysis of on-site monitoring data and dust diffusion characteristics, the dust emission concentration parameter was determined as 58.4 mg/m3. Hence, the emission rate S (mg/s) is calculated using the formula S = 58.4 × Q, where Q represents the airflow rate (m3/s). A perfectly mixed model is applied at the network nodes, which assumes that all incoming dust-laden air streams undergo instantaneous and complete mixing. This process yields a single, homogeneous dust concentration in every outflowing air stream, thereby neglecting the effects of localized turbulence or internal concentration gradients within the node. The standard pollutant dispersion module in Ventsim does not account for dust deposition losses caused by gravitational settling or wall collisions. It simplifies dust transport by treating all emitted dust as a conservative passive scalar that moves entirely with the airflow until it exits the mine system. This approach offers acceptable accuracy when simulating fine particulate matter with strong suspension capabilities or when modeling over relatively short distances. The Ventsim software was used to simulate dust diffusion paths and concentration distributions within the ventilation network based on this parameter, with the resulting dust concentrations for all roadways under the three ventilation schemes provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Dust concentration unit in the main roadways of the mining area (mg/m3).

The original ventilation system failed to maintain dust concentrations below the 4 mg/m3 threshold defined in GBZ 2.1-2019 [28], with levels in all main roadways posing a clear compliance challenge. Exceptionally high dust concentrations were identified in several critical zones, including the slope of No. 2 Basin, the 340 mid- range (situated north of the slope of the 7th vein), and the boundary transportation roadway. These elevated levels posed a significant occupational health hazard. In contrast, all three ventilation optimization schemes achieved a marked reduction in dust concentrations across the mining area, demonstrating their overall efficacy and practical viability.

5. TOPSIS Method for Optimal Selection

In the ventilation system optimization study for the multi-panel mining areas of the Maping Phosphate Mine, the three alternative schemes showed varied performance across different evaluation indicators, with none demonstrating clear overall superiority. This necessitates a systematic evaluation to compare their relative merits. The Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution was employed to establish a comparable basis for objectively ranking the schemes amid multiple competing evaluation criteria. TOPSIS was chosen chiefly because it calculates the relative distance of each alternative to the ideal best and worst solutions. This simultaneous measurement of dual benchmarks provides a balanced perspective, therefore mitigating the partiality that arises from relying on a single evaluation dimension. The method’s transparent principles and reproducible results make it well-suited for reliable decision-making. It ranks alternatives based on their relative closeness coefficients, thereby enabling the identification of the ventilation scheme with the superior overall performance profile.

5.1. The Principle of TOPSIS Method

The core selection criterion of the TOPSIS method dictates that the optimal solution should simultaneously be geometrically closest to the Positive Ideal Solution and farthest from the Negative Ideal Solution. Here, the Positive Ideal Solution is hypothetically constructed by selecting the best attainable value for every evaluation attribute across all candidate schemes. Conversely, the Negative Ideal Solution is formed by taking the worst value for each attribute from the same set of candidates [29,30]. The calculation steps are as follows:

Homogenization of indicator attributes, converting all extremely small indicators into extremely large ones:

In the formula: M represents the maximum value in xi.

For the standardization of the co-directional matrix, there are m schemes, each with an attribute value, forming a decision matrix X = (xij)m×n, as shown in the following formula:

Here, xij represents the value of the j-th attribute of the i-th scheme.

Standardize the decision matrix to eliminate the influence of different attribute dimensions. The standardized matrix is R = (rij)m×n, and the calculation formula is:

The Positive Ideal Solution (R+) and the Negative Ideal Solution (R−) are defined as vectors composed of the optimal and poorest values, respectively, achieved by each evaluation indicator across all candidate schemes.

The vectors R+ and R− are formed by aggregating the best and worst attribute values, respectively, from all candidate schemes. The “best” value is defined as the maximum for a benefit attribute and the minimum for a cost attribute; the “worst” value is the opposite [31].

Calculate the distance from each scheme to the ideal solution and the negative ideal solution, and the distance from each scheme Ri to the ideal solution:

The distance from each scheme Ri to the negative ideal solution:

Among them, aj+ and aj− are the values of the j-th attribute of the ideal solution and the negative ideal solution, respectively, and Wki is the weight of this index.

Calculate the relative proximity:

The greater the relative proximity, the better the scheme is.

5.2. The Result of the Optimal Plan Selection

The analysis is grounded in numerical simulation results of the ventilation system generated by Ventsim software. Furthermore, it draws on the evaluation principles of safety reliability and economic rationality introduced by Jiang et al. [32], forming the basis for a multi-indicator assessment, eight key indicators covering ventilation effect, system resistance, fan performance, dust control, operation management and economic cost were selected. An evaluation system structured around four dimensions—safety, technical feasibility, economy, and operability—was established based on these principles. The safety dimension employs average wind speed and dust concentration to monitor environmental conditions and mitigate risks related to dust accumulation or resuspension. Technical feasibility is assessed through system resistance and fan efficiency to ensure balanced airflow distribution and equipment compatibility. The economic dimension evaluates investment and operational benefits using annual equivalent cost, while operability is reflected in a management difficulty index that considers the practicality of routine adjustments. This integrated indicator system provides a comprehensive basis for the TOPSIS model, with detailed values for each scheme presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Index values of each scheme.

Substitute the three ventilation scheme evaluation criteria values in this table into the calculation process of the TOPSIS method for operation, as follows:

Construct index matrix A based on the three scheme index values in Table 5:

From Equation (1), converting the index attributes of matrix A in the same direction gives the decision matrix X:

The decision matrix X is standardized by Equation (3) to obtain the same-direction standard matrix R:

Determine the optimal plan and the worst plan

The entropy weight method is an objective weighting approach that determines indicator importance based on their information entropy, which measures data variability. A core tenet is that an indicator with lower entropy exhibits higher variability and information content, indicating that it should carry greater weight in a comprehensive evaluation. Indicators possessing greater information entropy display limited variation and informational value, thus receiving reduced weight in the evaluation. The method relies solely on the statistical properties of the dataset to produce objective weights, effectively circumventing the subjectivity inherent in expert judgment. The steps of the entropy weight method are as follows:

Construct the evaluation matrix:

Let the evaluation matrix composed of m evaluation schemes and n indicators be:

Standardization of indicators:

Due to the inconsistent dimensions of various evaluation indicators, it is necessary to first carry out data standardization processing and then construct a sample matrix.

Calculation formula for benefit-oriented indicators:

Calculation formula for cost-based indicators:

Find the information entropy of each index:

Among them ; ; When Yij = 0, define Yij × ln (Yij) = 0

Calculate the information entropy redundancy, that is, the utility value.

Calculate the weight of the indicator:

The weights of each indicator calculated by the entropy weight method are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Normalize the weights of each indicator.

The distances of each scheme to the ideal and negative ideal solutions were calculated applying Equations (4) and (5), using the weights assigned to each indicator. Taking Scheme one as an example:

Calculate the relative proximity by Equation (6):

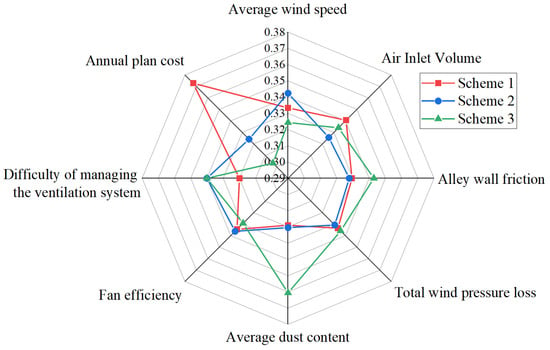

Based on the TOPSIS evaluation, Scheme Two is identified as the optimal ventilation scheme with the highest relative closeness degree of 0.8838, compared to 0.5612 for Scheme One and 0.3107 for Scheme Three. As illustrated in Figure 6, the superior performance of Scheme Two is evident in its balanced achievement across critical metrics such as average wind speed, system pressure loss, roadway friction coefficient, and total air intake volume. By implementing more reasonable regional airflow adjustments, Scheme Two enables the ventilation system to attain a near-optimal operational state. Its true strength lies in superior systemic integration: despite not being optimal in cost or fan efficiency individually, it achieves a critical improvement in overall system balance, thereby addressing the core practical needs of safety and ventilation performance.

Figure 6.

Comparison of three optimization schemes.

The evaluation ranked the three ventilation schemes according to their proximity to the ideal solution, identifying Scheme Two as the top performer. Its superiority is demonstrated in two main aspects: regarding ventilation performance, it excels in air intake volume, dust control, and air velocity distribution; regarding economic operation, it records the minimal pressure loss of 621.97 Pa—implying lower drag and energy demand—alongside the highest fan efficiency, which denotes effective energy conversion and system synergy.

With an average dust concentration of 2.15 mg/m3, Scheme Two performs comparably to Scheme One (2.14 mg/m3) and markedly better than Scheme Three (2.42 mg/m3), demonstrating successful dust management. While its design choices slightly compromised fan efficiency and dust control metrics, they yielded significant benefits in cost reduction and overall system performance, leading to its top position in the TOPSIS ranking.

Implemented in active mine production, Scheme Two has proven effective in significantly enhancing underground ventilation and controlling dust concentration without substantially raising costs, thereby strengthening safety assurances. This successful translation of design into practice serves as a validation of the TOPSIS method’s effectiveness and utility in determining optimal engineering solutions. To verify model robustness, sensitivity testing of the weight system revealed that ±10% perturbations in dust concentration and inlet air volume—identified as highly sensitive indicators—induced fluctuations in the relative closeness degree of Option 2 within the 0.63–0.68 range without altering ranking stability. Conversely, a 1-point reduction in the ventilation management difficulty score on the 10-point scale precipitated a 9.1% decline in closeness degree, underscoring this indicator’s substantial influence on decision outcomes. In contrast, the roadway wall friction coefficient exhibited lower sensitivity, requiring extreme ±30% variations to trigger a greater than 3% change in closeness degree. The achievement of dust concentrations below the GBZ 2.1-2019 regulatory threshold demonstrates effective mitigation of localized dust accumulation, a persistent challenge in multi-panel mining systems as documented by Paluchamy et al. Scheme Two addresses the critical issue of insufficient airflow penetration, previously identified by Yao et al. as a primary contributor to stagnant dust accumulation, by systematically increasing airflow from sub-1.0 m3/s to an optimized range of 5.0–13.0 m3/s in key zones.

6. Conclusions

Using the Maping Phosphate Mine as a case study, this research focuses on ventilation challenges including uneven airflow distribution and poor effectiveness in specific mining areas during concurrent multi-face operations. A numerical simulation of ventilation performance across four mining areas was conducted with Ventsim software, integrated with the TOPSIS method for scheme optimization. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- A full-ventilation-system simulation model constructed for Maping Phosphate Mine generated airflow data for primary tunnels and key faces, demonstrating reasonable parameters and a strong match with actual measurements.

- (2)

- Three stope ventilation optimization schemes were designed via the Ventsim platform to correct disordered airflow and excessive dust concentrations. Key roadway data for airflow and dust levels under each scheme were compiled, providing a quantitative foundation for optimization decisions.

- (3)

- A TOPSIS model quantitatively assessed multi-area ventilation schemes against eight indicators. Following detailed analysis, Scheme Two emerged as the preferred option, providing more balanced regional airflow distribution while lowering annual ventilation costs and dust concentrations considerably, which demonstrates both technical and practical merits.

- (4)

- This study has yielded positive results, though limitations exist regarding the steady-state assumption of the Ventsim model. Building on this foundation, future work will pursue dynamic ventilation models that simulate real-time responses to operational and natural changes. The integration of IoT sensor data will further enable the development of a digital twin for predictive ventilation control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z. and L.Z.; methodology, Z.Z.; software, Z.Z.; validation, Z.Z. and L.Z.; formal analysis, L.Z.; investigation, Z.X.; resources, Z.X.; data curation, Z.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z.; writing—review and editing, L.Z. and Z.X.; visualization, Z.Z.; supervision, Z.X.; funding acquisition, Z.X. and L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Wuhan Institute of Technology Research Start-up Fund, grant number 23QD82.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Wuhan Institute of Technology for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Ventsim | Ventilation Simulation Software |

| Fluent | A computational fluid dynamics (CFD) software package |

| TOPSIS | Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| GBZ | National Occupational Health Standard of China |

References

- Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z. Research and Optimization of Intelligent Ventilation System in Jianzhuang Coal Mine. Shanxi Coal 2023, 43, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mmbaga, J.P.; Hayes, R.E.; Profic-Paczkowska, J.; Jędrzejczyk, R.; Chlebda, D.K.; Dańczak, J.; Hildebrandt, R. Recuperation in a Spiral Reactor for Lean Methane Combustion: Heat Transfer Efficiency and Design Guidelines. Processes 2025, 13, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bazi, N.; Laayati, O.; Darkaoui, N.; El Maghraoui, A.; Guennouni, N.; Chebak, A.; Mabrouki, M. Scalable Compositional Digital Twin-based Monitoring System for Production Management: Design and Development in An Experimental Open-pit Mine. Designs 2024, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovchinnikova, E.; Kozhubaev, Y.; Wu, Z.; Sabbaghan, A.; Ershov, R. Modeling of Multifunctional Gas-Analytical Mine Control Systems and Automatic Fire Extinguishing Systems. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B. Practice and Application of Local Ventilation System Optimization Technology in Hou ’an Coal Mine. West. Prospect. Eng. 2021, 33, 169–173+176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, H.A. Energy Consumption Reduction in Underground Mine Ventilation System: An Integrated Approach Using Mathematical and Machine Learning Models Toward Sustainable Mining. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, S.; Sotoudeh, F.; Sereshki, F. Application of VENTSIM 3D and mathematical programming to optimize underground mine ventilation network: A case study. J. Min. Environ. 2018, 9, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. Research on Simulation Modeling and Optimization Scheme Evaluation of Ventilation System in Daning Coal Mine. Energy Technol. Manag. 2025, 50, 120–123+170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Suo, C. Study of Coal Mine Ventilation System Optimization based on Ventsim. MATEC Web Conf. 2016, 44, 02016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, J. Optimization of ventilation system in deep well gold mine based on Ventsim. E3S Web Conf. 2025, 625, 03010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L. Analysis of Coal Mine Ventilation System and Exploration of Air Volume Optimization. West. Prospect. Eng. 2021, 33, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ren, T.; Wang, Z.; Song, S. Application of ventilation simulation to spontaneous combustion control in underground coal mine: A case study from Bulianta colliery. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Mishra, D.P.; Agrawal, H.; Bhattacharjee, R.M. WBGT Prediction and Improvement in Hot Underground Coal Mines Using Field Investigations and VentSim Models. Min. Metall. Explor. 2023, 40, 985–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, L.; Quan, F. Current Situation of Coal Mine Ventilation System and Design of Intelligent Ventilation System. Autom. Ind. Min. 2015, 41, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluchamy, B.; Mishra, D.P. Measurement and analysis of airborne dust generation and dispersion from low-profile dump truck haulage in underground metalliferous mines. Measurement 2024, 227, 114252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, T.; Ma, S.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. The multi-factor influence of wind speed distribution in roadway sections with uneven roof. J. Cent. South Univ. 2021, 28, 2067–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, P.; Jiang, J.; Sun, Z. Research on the Y-shaped Ventilation and Air Leakage Law of the Mining Face along the empty Residual Roadway after top cutting and pressure Relief. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2021, 38, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Lu, G.; Xu, K.; Wang, Y. Ventilation and dust suppression system for fully-mechanized Caving face with large Inclination Based on FLUENT. J. Northeast. Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2014, 35, 1497–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Dong, F.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y. Research on Numerical Simulation and Calculation Model of Natural Wind Pressure in Deep Wells. Nonferrous Met. Eng. 2024, 14, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, C. Mine ventilation Optimization Algorithm Based on Simulated Annealing and Improved Particle swarm. J. Syst. Simul. 2021, 33, 2085–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, M. Evaluation of Ventilation System Based on Entropy Weight TOPSIS Method. Shandong Coal Sci. Technol. 2016, 8, 98–100+105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cui, X.; Zuo, C.; Wang, W. Reliability Evaluation of Mine Ventilation System Based on Game Theory Combined Weighting -TOPSIS Method. J. Shanxi Datong Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2024, 40, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. Evaluation of Mine Ventilation Quality Based on AHP-TOPSIS Model. Jinkong Sci. Technol. 2023, 5, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Zhou, H. Optimization of Ventilation System Schemes in Plateau Mines Based on AHP-TOPSIS Method. Chem. Miner. Process. 2021, 50, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Hou, Y.; Jin, H.; Ma, L.; Wang, Z. Safety Evaluation Method of Mine Ventilation System Based on the Improved AHP-TOPSIS Model. Min. Res. Dev. 2023, 43, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Ma, Y.; Wang, L. Simulation study and Model Improvement of goaf Firing Process under U-shaped Ventilation. J. Syst. Simul. 2015, 27, 3096–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lu, B.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y. Simulation Implementation of Asynchronous Reverse air in Multi-air Shafts of mines in Disaster Ventilation. J. Syst. Simul. 2016, 28, 2979–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBZ 2.1-2019; Occupational Exposure Limits for Hazardous Agents in the Workplace—Part 1: Chemical Hazardous Agents. National Health Commission: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Li, Q. Research on the Renovation and Scheme Optimization of Ventilation System in Multi-Section Mines Based on Large-Scale Mining Layout. Master’s Thesis, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, China, 2023. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/doi/10.27200/d.cnki.gkmlu.2023.001549 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Chen, X.; Yang, S.; Hu, D.; Li, X. Sustainable mining method selection by a multi-stakeholder collaborative multi-attribute group decision-making method. Resour. Policy 2024, 92, 105043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail Lawal, A.; Onifade, M.; Kwon, S.; Khandelwal, M. Enhancing gas drainage and ventilation efficiency in underground coal mines: A hybrid expert decision approach for booster fan prioritization. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 155, 106153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Cui, S.; Tan, P.; Wei, Y.; Wei, L.; Song, X. Comprehensive Evaluation Index System and Method of Mine Ventilation System. Min. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 51, 25–32+39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).