Abstract

Steam flow-induced vibration (FIV) of cooling tubes poses critical failure risks in nuclear power plant condensers. However, accurate FIV prediction remains challenging due to the complex three-dimensional flow structures in full-scale condensers, which are often oversimplified in existing models. To address this gap, this study develops a novel full-scale Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) model that uniquely integrates the low-pressure exhaust cylinder, condenser throat, and tube bundles. This approach enables a comprehensive evaluation of shell-side flow characteristics and FIV phenomena under both Valve Wide Open (VWO) and partial-load conditions (with either Modules A/C or B/D active). The results quantitatively identify peak FIV risk coefficients in specific zones—particularly at branch-shaped channel inlets and certain tube bundle corners where steam impingement is most intense—with values reaching 0.7 under VWO, 0.67 with Modules A/C active, and 0.74 with Modules B/D active. Notably, the peak FIV risk under B/D active condition is approximately 10.4% higher than under A/C active condition, indicating that partial-load operation with Modules B/D active presents the highest FIV risk among investigated scenarios. These findings provide novel insights into FIV mechanisms and establish a critical theoretical foundation for optimizing condenser design and enhancing operational safety protocols.

1. Introduction

As critical large-scale heat exchangers in nuclear power plants, condensers exhibit complex internal flow fields characterized by multicomponent, multiphase heat and mass transfer phenomena [1]. During operation, thousands of cooling tubes are subjected to continuous steam crossflow. In particular, high-speed steam can induce fluidelastic instability in titanium tubes, especially in peripheral regions where steam velocity is relatively high. These flow-induced vibrations (FIV) may lead to fretting wear, structural fatigue, and even tube rupture, posing serious threats to unit safety. Documented case studies confirm that FIV under high-velocity steam impact has resulted in cooling tube fractures and seawater intrusion in operating plants [2,3]. Therefore, a comprehensive analysis of internal steam dynamics and the identification of high-velocity-induced vibration zones are essential for condenser structural optimization and nuclear safety assurance.

Early foundational work by Patankar and Spalding [4] introduced the equivalent porous media model, which abstracted tube bundles into a phase-changing porous medium, making system-level thermal analysis computationally feasible. While useful for predicting overall condenser efficiency and backpressure, this approach inherently sacrifices the resolution needed to analyze localized flow dynamics around individual tubes. As a result, many contemporary studies on condenser flow fields still rely on two-dimensional (2D) simulations [5,6] or focus primarily on the effect of tube bundle arrangement on macroscopic thermal performance [7]. A more recent study by Zu et al. [8] directly investigated FIV in a nuclear condenser using a 2D numerical model limited to the throat and tube bundle area. However, this model omitted the upstream exhaust cylinder, despite the fact that the highly uneven steam flow field at the cylinder’s outlet significantly influences flow uniformity within the condenser. Although computationally efficient, such 2D approaches are fundamentally unable to capture three-dimensional vortical structures and asymmetric flow effects, which are critical for accurate FIV assessment. This limitation arises because 2D models cannot resolve velocity components and spatial gradients in the out-of-plane direction, which are essential for representing the full dynamics of vortex formation and flow asymmetries.

These limitations become particularly evident when compared with the state-of-the-art in FIV research for other engineering systems. In broader FIV studies, high-fidelity three-dimensional Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has become the cornerstone for unraveling complex vibration mechanisms. For instance, Pan [9] et al. employed Large Eddy Simulation (LES) to capture transient vortex interactions in the flow around multiple flexible cylinders, demonstrating the importance of resolving 3D vortical structures for accurate vibration prediction. Similarly, Ding [10] et al. used full 3D CFD to investigate the vibration response of helical tube arrays—a geometry with intrinsic three-dimensionality—underscoring the necessity of 3D modeling for non-uniform flow paths. Furthermore, advanced CFD analyses are being extended to more complex flow conditions, as shown by Emmerson [11] et al., who analyzed multiphase flow-induced forces, highlighting modern numerical tools’ capability to handle coupled physics relevant to industrial safety. The trend even extends to integrating CFD with data-driven models, as seen in the work of Chen [12] et al., who combined CFD with an artificial neural network to predict vortex-induced vibration mechanisms, pushing the frontier of predictive capability.

While numerous studies have established numerical models for condenser analysis, most focus on overall thermal performance and efficiency [13,14]. Although these models successfully predict macroscopic parameters, they often lack the resolution to capture localized flow phenomena around tube bundles, which are the root cause of FIV. Moreover, existing FIV assessments in such systems frequently rely on post-design analysis or empirical guidelines, offering limited proactive risk mitigation [15,16].

In recent years (2020–2024), several studies have employed full 3D simulations for condenser analysis. For example, Lu et al. [17] (2024) conducted a 3D transient pressure analysis for the HPR1000 nuclear unit, focusing on system-level dynamics. Other contemporary works have advanced the modeling of complex multiphase flows in related components, such as the sophisticated Large Eddy Simulation and VOF models used by Chen [18] et al. to investigate transient flow and bubble distribution in submerged entry nozzles, demonstrating the capability of high-fidelity 3D models to resolve complex fluid phenomena. However, these studies often focus either on global system parameters or on specific localized phenomena, confined to the tube bundle region without coupling the low-pressure cylinder, and without fully integrating the upstream turbine exhaust effects for a comprehensive FIV assessment. This gap distinguishes our work, which specifically employs a fully coupled exhaust-condenser 3D model to establish a direct link between the simulated flow field and FIV risk identification—an approach not yet widely reported in the recent literature on nuclear condensers.

Overall, the literature review reveals a clear research gap: although existing studies have provided valuable insights into the thermal performance of condensers, there is a lack of high-fidelity, fully three-dimensional, and coupled simulations capable of resolving the local flow structures that lead to FIV in nuclear power condensers. In particular, no previous study has integrated the low-pressure exhaust cylinder with the full condenser shell-side flow field in a 3D model to accurately predict high-risk vibration zones.

To bridge this gap, this study establishes a high-fidelity, full-three-dimensional CFD model of a nuclear power condenser that is directly coupled with the low-pressure exhaust cylinder. This coupled approach enables accurate simulation of the non-uniform inlet steam flow and its impact on internal flow dynamics. The primary novelty and contribution of this work are twofold: First, it moves beyond thermal-efficiency-focused models and simplified 2D/quasi-3D FIV analyses by providing a high-resolution, physically complete simulation framework. Second, it leverages this high-fidelity model not merely for simulation, but as a proactive risk assessment tool. The model is designed to identify high-FIV-risk zones for targeted sensor placement and structural optimization, thereby directly enhancing nuclear condenser safety protocols and offering data-backed guidance for design and operation.

2. Physical and Numerical Models

2.1. Physical Model and Computational Domain

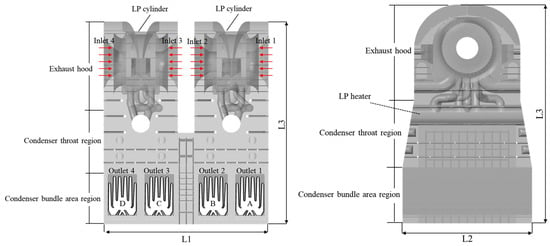

The condenser for this nuclear power unit features a dual-shell, single-pass, constant-backpressure surface configuration. Key components include the throat section, tube bundle modules (A–D), hotwell, flash tank, water chambers, dual low-pressure heaters, condensate polisher, and vacuum system. Four tube bundle modules (labeled A through D from right to left when viewed from the circulating water inlet) condense exhaust steam from the low-pressure turbine. Figure 1 illustrates the condenser configuration, the structure of the model mainly includes Exhaust hood, Condenser throat region, Condenser bundle region, coupled low-pressure(LP) cylinders and Lp heater, with essential parameters provided in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Condenser model diagram.

Table 1.

Parameters of the condenser.

The prevailing approach in prior numerical simulations was to concentrate on the tube bundle domain, while the low-pressure cylinder was seldom included. Since the upper structure of the condenser substantially affects the flow field uniformity at the throat outlet, we established a model coupled with the low-pressure cylinder. This methodology yields a superior reflection of the true flow field behavior.

2.2. Grid Independence Verification

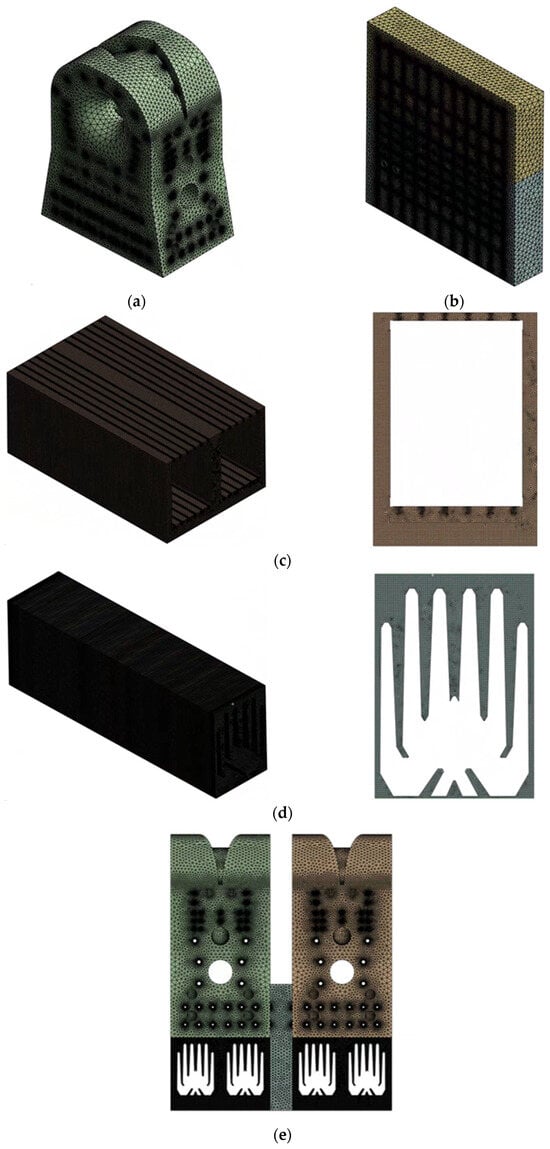

Unstructured meshes were selected for their superior adaptability to complex condenser geometries (e.g., tube bundles, tube sheets, curved ducts), effectively minimizing discretization errors from grid distortion. These meshes enable targeted refinement in boundary layers and high-gradient regions, significantly enhancing resolution of fluid flow phenomena. Additionally, they offer substantial advantages in grid generation efficiency and adaptation flexibility, accelerating simulation workflow while maintaining accuracy.

During mesh partitioning, the physical domain is partitioned into four distinct regions: throat, periphery, intermediate connection, and chamber. The throat and intermediate connection regions employ default tetrahedral/polyhedral meshing with a base size of 3500 mm. This approach combines computational efficiency with robust geometric adaptation, automatically generating conformal meshes that resolve complex topological features while minimizing user intervention.

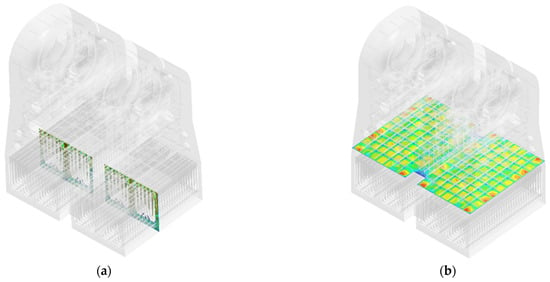

Sweep meshing was implemented for the peripheral and chamber regions, and the geometric refinement is performed simultaneously. The refinement size of the peripheral region is 50 mm, and the refinement size of the chamber region is 35 mm. This method has the advantages of high efficiency and high quality in grid partitioning, especially suitable for stretching, rotating, or geometries with regular cross-sections. It can efficiently create high-quality hexahedral or prismatic meshes and improve computational accuracy by extending an initial face along a specific direction or path to generate meshes. Its structured topology provides exceptional size uniformity, enhancing computational accuracy while reducing cell counts. For fluid domains connected across tube sheets, non-conformal interfaces were established. The complete meshing strategy is visualized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The meshing scheme for distinct computational domains: (a) Throat region mesh; (b) Connection mesh; (c) Peripheral region mesh; (d) Chamber region mesh; (e) The condenser mesh.

The present study employs a steady-state solver to obtain the time-averaged flow field and related parameters. The governing equations were discretized using the second-order scheme for spatial accuracy. For the iterative solving process, a pseudo-time-stepping approach was adopted to enhance convergence robustness. The term time step in this context refers to a relaxation parameter under the steady-state formulation, which does not represent a physical time advance and thus has no bearing on the temporal accuracy of the final solution. The value of 0.05 for this pseudo-time step was selected based on the solver’s default settings for similar applications and was confirmed to provide stable and efficient convergence for all cases in this work, with the root-mean-square residuals of all governing equations dropping below 10−6.

However, it must be pointed out that the current numerical methods have limitations. This study used a steady-state framework, which provides solutions for time-averaged flow fields. Although this method is computationally efficient and highly suitable for predicting global performance parameters, it cannot analyze the inherent transient vortices and pulsation characteristics in shell-side steam flow. Therefore, all results presented in this paper must be interpreted as time-averaged values. In the future, transient simulation methods such as LES or transient RANS will be needed to further investigate these important dynamic details.

In contrast to the iterative time step, the spatial discretization (grid resolution) significantly influences the computational accuracy of the steady-state solution. While mesh refinement enhances solution precision, it proportionally increases computational demands. Therefore, grid independence was verified through five systematically refined cases under VWO conditions: 50.90, 53.22, 55.53, 57.85, and 60.16 million cells. The maximum FIV risk coefficient and the maximum velocity served as the convergence metrics (Table 2). Results demonstrate asymptotic convergence of both the maximum excitation value and the maximum velocity beyond 55.53 million cells, with the former stabilizing at 0.700 (Δ < 0.5% between 57.85 M and 60.16 M cases) and the latter showing variations of less than 0.3% in the same range. Full FIV risk distributions are analyzed in Section 3. The 57.85-million-cell mesh was selected for subsequent simulations, achieving an optimal accuracy/computational cost balance while ensuring convergence of both key parameters.

Table 2.

Grid independent verification under VWO condition.

2.3. Calculation Method and Boundary Condition

The three-dimensional simulation employs the Shear Stress Transport (SST) turbulence model. This model is widely used in engineering simulations [19] and combines the k–ω model for near-wall flow with the k–ε model away from the wall, achieving enhanced predictive capability for flow separation phenomena [20]. The governing equations are expressed as:

where ρ is the density; k is turbulent kinetic energy; ω is the specific dissipation rate; t is time; uj is the component of velocity in the j direction; xj is the component of x in the j direction; P is the turbulent kinetic energy generation term; β is the model constant; β* is the model constant; Dk is the diffusion term in the k equation; Dω is the diffusion term in the ω equation; Cω is a cross diffusion term.

In the equations, the first three terms on the right-hand side represent the turbulence production term, dissipation term, and diffusion term, respectively. The C term in the ω equation denotes the cross-diffusion term. The values of the closure coefficients in these equations can be found in Reference [21]. The equilibrium wet steam model (steam1vl) is adopted, with thermodynamic properties referenced from the IAPWS-IF97 standard for working fluids [22].

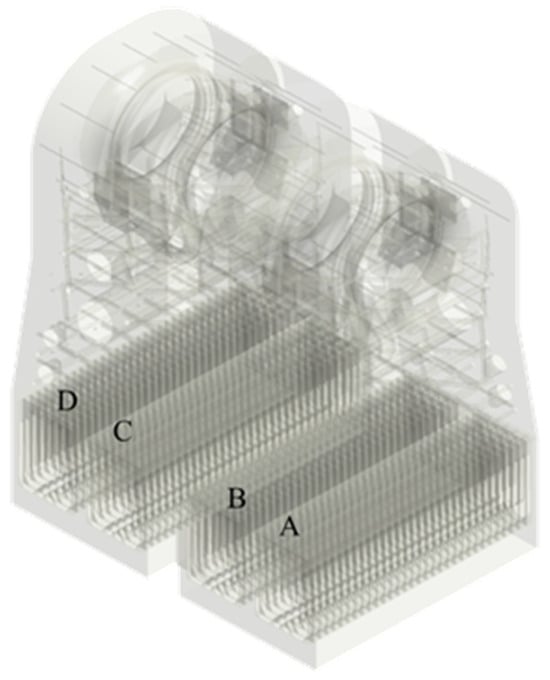

A fluid domain model of the condenser was developed, as shown in Figure 3. The tube bundles were partitioned into four distinct modules (A, B, C, and D). Numerical simulations were performed under two operational configurations:

Figure 3.

Fluid domain model diagram of condenser.

- (1)

- Full-load (VWO condition): All modules (A–D) active.

- (2)

- Partial-load configurations:

- -

- Modules A and C activated

- -

- Modules B and D activated

Given the substantial number of heat exchange tubes, a coupled analysis would necessitate an excessively large mesh, consuming significant computational resources. Practical engineering observations, however, indicate that flow-induced collisions and wear predominantly occur at the outermost section of the bundle—the upstream face. Thus, to conserve computational resources, the outermost boundary is modeled as an outlet, and the excitation risk region of the outermost tube bundle is assessed based on the derived velocity distribution. This approach provides valuable guidance for evaluating the flow-induced excitation characteristics and identifying high-risk zones on the outermost side of the bundle area.

Table 3 summarizes the three operational cases and corresponding computational domain boundary conditions. The total temperature and the mass flow inlet boundary conditions and the humidity are used to define the properties of the flow at inlet boundaries.

Table 3.

Boundary conditions.

- Valve Wide Open (VWO) case: four inlet mass flow rates, inlet temperature and the humidity of steam are set to be 232.7068 kg/s, 308.377 K, 10.261%, respectively. For the outlet of the chamber, the pressure is set to be 5.7 kPa.

- Partial-load cases (modules A/C and B/D active): the four inlet mass flow rates, the inlet temperature and the humidity of steam are set to be 232.5757 kg/s, 319.764 K, and 8.21%, respectively. The outlet boundary condition is set to “pressure outlet” with the outlet pressure of 10.5 kPa.

All cases employed pressure outlet boundary conditions. Back pressures were specified as 5.7 kPa (VWO) and 10.5 kPa (partial-load), respectively.

2.4. The Evaluation Method of the Steam-Flow-Induced Vibration Risk Coefficient

The assessment of flow-induced vibration (FIV) due to crossflow in tube bundles requires a criterion to predict the onset of fluid-elastic instability—a primary excitation mechanism that can lead to rapid tube failure. For this purpose, this study adopts the critical velocity criterion outlined in the Chinese National Standard GB/T 151-2014 “Heat Exchangers,” which is based on the well-established Connors formula.

The Connors formula defines the critical crossflow velocity (Vc), which represents the threshold flow velocity above which the damping capacity of the tube is exceeded, and self-exciting, destructive fluid-elastic vibrations will initiate. The calculation formula of Vc is [23]:

where m is the mass per unit length of the tube, including the mass of the fluid, kg/m; ρ is the density of the fluid outside the pipe, kg/m3; f1 is the natural frequency of the tube, 1/s; δ is the logarithmic decay rate of the tube; Kc is an empirical stability constant dependent on tube array geometry.

When the heat exchange tube decays, the natural logarithm of the ratio of the amplitudes of any two adjacent periods is the natural decay rate, expressed in δ, and the calculation formula is [23]:

where n is the number of spans of the cooling pipe; tb is the thickness of the tube sheet; lm is the span of the cooling pipe.

To quantitatively evaluate the FIV risk, we calculate an excitation risk coefficient (α) for each tube. This coefficient is defined as the ratio of the local, actual steam flow velocity (V) to the Vc of that tube [23]:

The arrangement of condenser heat exchanger tubes is regular triangle arrangement. According to the literature, heat exchanger: GB/T 151-2014 [23], b = 0.5, and the calculation formula of proportional coefficient Kc is:

where S is the center distance of the heat exchange tube and d0 is the outer diameter of the cooling tube.

According to the literature heat exchanger: GB/T 151-2014 [23], the calculation formula of mass m per unit length of cooling pipe is:

where mi is the mass of fluid in the heat exchange tube; m0 is the virtual mass of fluid outside the tube, which is displaced by the vibrating tube; m1 is the mass of empty tube.

In general, the support condition of the heat exchange tube is that it is fixed at the end of the tube sheet and simply supported at the baffle. The cooling pipe in the condenser is treated with equal span, and the number of spans is n = 30. According to the literature heat exchanger: GB/T 151-2014 [23], the frequency constant λn of equal span straight pipe is found to be 9.9, and the calculation formula of natural frequency of equal span straight pipe is:

where E is the elastic modulus of titanium tube; l is the span.

Based on the condenser model, the main parameters have been determined: Kc =2.41, b = 0.5, f1 = 108.99 Hz, δ = 0.0467, m = 0.507 kg/m.

Finally, the FIV risk coefficient α is expressed as:

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Condenser Flow Field Characterization

VWO represents the maximum design operating condition, used to assess extreme risks. The two partial load conditions represent the most common operating range of the power plant and the state that is most prone to flow instability. Therefore, we have chosen these three key and representative operating modes as the simulated operating conditions.

3.1.1. Model Assumptions and Limitations

The model’s boundary conditions (uniform velocity inlets, constant pressure outlets) represent idealized operational states. In reality, transient fluctuations and non-uniformities at the condenser inlet could modify the internal flow dynamics.

Regarding the underlying assumptions of the turbulence model, the employed SST k-ω model operates on the RANS framework, which assumes turbulence can be represented by an isotropic eddy viscosity (Boussinesq hypothesis). While this provides a good balance of accuracy and robustness for the steady-state, wall-bounded flows in this study, its potential limitation lies in imperfectly capturing complex, anisotropic turbulent structures. This could impact the quantitative accuracy of local flow field details, such as shear layer development or mixing rates.

The validity of the current steady-state model has been established for the three representative operational conditions simulated (VWO and two partial loads). Its predictive accuracy under strong transient scenarios (e.g., rapid startup or trip) or extreme off-design conditions remains unverified, as these might involve flow physics outside the calibrated range of the employed turbulence model.

3.1.2. Flow Field Characterization in Condenser Under VWO Condition

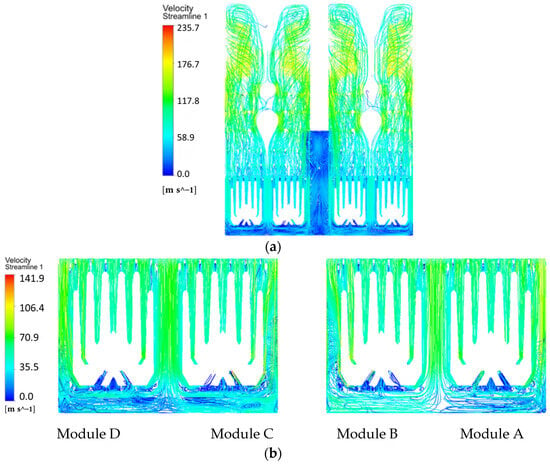

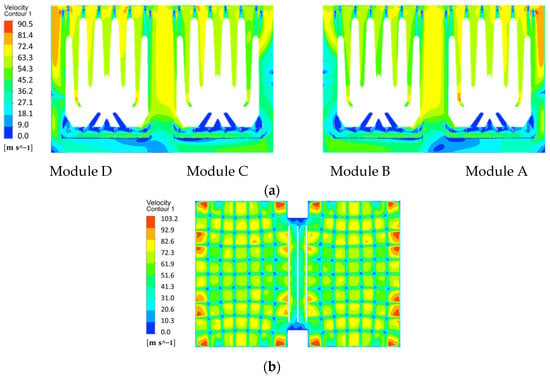

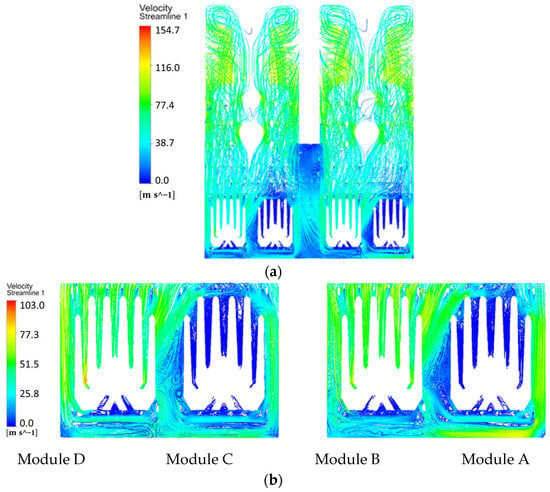

Figure 4a illustrates the three-dimensional streamline distribution under VWO conditions. Steam velocity decreases progressively from top to bottom, with minimum values observed in the condenser’s central connecting regions and bottom zone. Figure 4b details the tube bundle flow patterns, revealing a peak steam velocity of 141 m/s in this region.

Figure 4.

Steam flow streamlines within the condenser under VWO condition: (a) Global view of the exhaust section and tube bundle; (b) Detailed view of the tube bundle region.

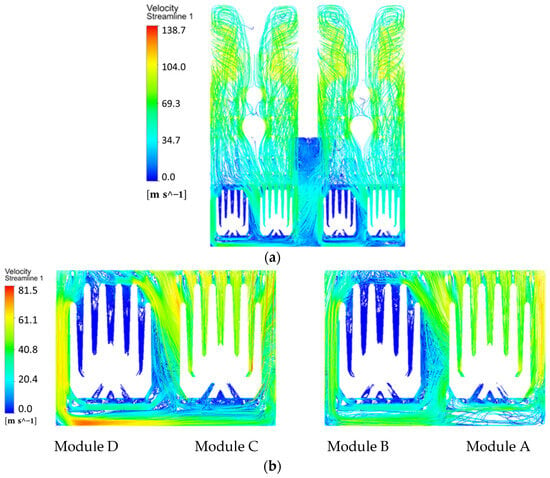

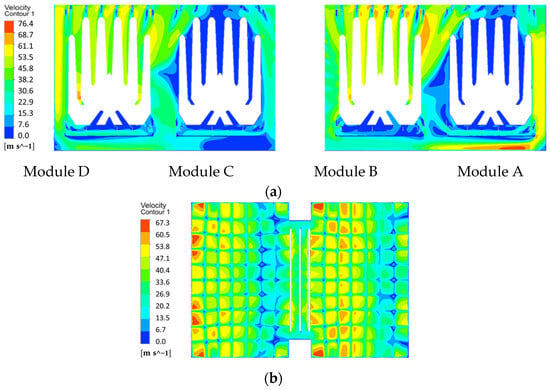

Qualitative velocity distribution analysis employed two cross-sections: at x = 1 m and z = 10 m (Figure 5). The color on the cross-sections indicates the VWO-condition velocity distribution on these cross-sections, as specifically shown in Figure 6, revealing that the maximum velocities occur near the shell wall in the region above the tube bundle. This velocity concentration results from flow field non-uniformity at the condenser throat exit (Figure 6b). Collectively, steam velocities in upper tube bundle regions exceed those in lower zones. This velocity gradient likely arises from operational dynamics: when all four tube bundle modules are active, steam discharges efficiently from upper regions, while steam flow velocity decreases in the bottom tube bundle region as it must circumvent the tubes.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of cross sections: (a) cross section at x = 1 m; (b) cross section at z = 10 m.

Figure 6.

The velocity distribution at different cross-sections under the VWO condition: (a) The velocity distribution at the cross-section (x = 1 m); (b) The velocity distribution at the throat exit (z = 10 m).

3.1.3. Partial-Load Flow Field Characterization in Condenser with Modules A/C Active

Numerical calculations were also conducted for the partial-load operating condition where modules A and C were active, while modules B and D were shut down. As shown in Figure 7a, steam velocity exhibits an overall gradual decrease from top to bottom under this configuration, similar to the trend observed under the VWO condition. Figure 7b presents the streamlines within the tube bundle region, where the maximum steam velocity reaches 81.5 m/s.

Figure 7.

The steam flow streamlines under partial-load operation (modules A and C active): (a) Global view of the exhaust section and tube bundle; (b) Detailed view of the tube bundle region.

Figure 8a shows the velocity distribution at the cross-section under the partial-load condition with modules A and C active. Steam velocities are higher in the regions beneath module D and above modules A and C compared to other areas. This asymmetry arises because the shutdown of modules B and D causes steam channeling and swirling near the active modules (A/C), while flow acceleration occurs in geometrically constrained regions due to reduced flow area. Conversely, steam above the inactive modules (B and D) cannot be discharged efficiently, resulting in lower flow rates in these regions.

Figure 8.

The velocity distribution at different cross-sections under partial-load operation (modules A and C active): (a) The velocity distribution at the cross-section (x = 1 m); (b) The velocity distribution at the throat outlet (z = 10 m).

3.1.4. Partial-Load Flow Field Characterization in Condenser with Modules B/D Active

Numerical calculations were performed for the partial-load operating condition with modules B and D active (modules A and C shut down), using the boundary conditions specified in Table 3. Figure 9a shows the velocity streamlines in the model. Similar to previous cases, steam velocity generally decreases gradually from top to bottom. Lower velocities occur in regions adjacent to the inactive modules (A and C), consistent with steam stagnation above shutdown units. Figure 9b depicts streamlines within the tube bundle region, where the maximum steam velocity reaches 103 m/s. A notable velocity difference was observed between the two partial-load configurations: the maximum velocity with modules B/D active (103 m/s) was approximately 26% higher than that with modules A/C active (81.5 m/s).

Figure 9.

The velocity streamline diagram under partial-load operation (modules B and D active): (a) Global view of the exhaust section and tube bundle; (b) Detailed view of the tube bundle region.

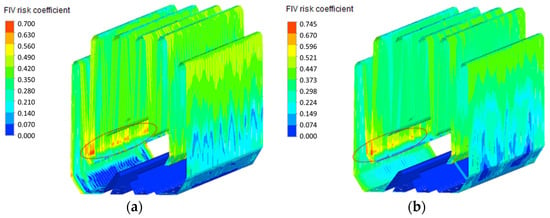

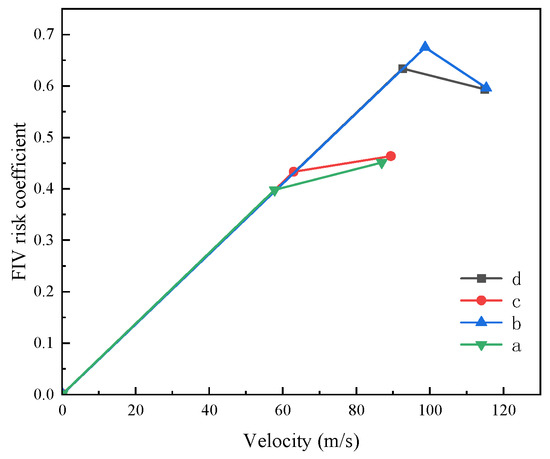

To further investigate this disparity, Figure 8b and Figure 10b present the comparative velocity contours at the condenser throat outlet. The velocity contour at the outlet demonstrates clear asymmetry with localized velocity acceleration in the B/D configuration, whereas the velocity distribution in the A/C configuration is more uniform. This distinct pattern at the outlet provides clear indirect evidence of the inherent geometric asymmetry within the throat, which causes a more pronounced flow diversion and acceleration in the B/D case. This flow difference is further quantified by the maximum FIV risk coefficient α, which is 0.74 for B/D operation compared to 0.67 for A/C operation—a 10.4% increase that underscores a significantly higher vibration risk.

Figure 10.

The velocity distribution at different cross-sections under partial-load operation (modules B and D active): (a) The velocity distribution at the cross-section (x = 1 m); (b) The velocity distribution at the throat outlet (z = 10 m).

From an engineering standpoint, this finding is of considerable significance. It clearly identifies the B/D active configuration as the more severe service condition, which should accordingly inform inspection planning and fatigue life assessments for the heat exchanger tubes. The demonstrated link between geometric asymmetry, localized velocity acceleration, and increased FIV risk provides valuable insight for condenser design and operational strategy under partial-load conditions.

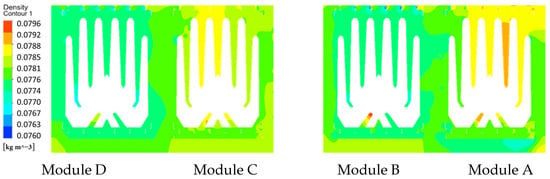

Figure 10a shows the cross-sectional (x = 1 m) velocity distribution under the partial-load condition with modules B and D active. Results indicate elevated steam velocities in regions beneath module A and above modules B and D. The activation state of bundle modules significantly influences flow field distribution characteristics. Notably, steam above inactive modules cannot discharge efficiently, creating localized low-velocity zones. This flow obstruction further induces steam channeling and swirling phenomena.

3.2. Fluid Elastic Instability Characterization

Fluidelastic excitation (synonymous with fluidelastic instability) arises from coupled hydrodynamic-structural interactions. When fluid velocity attains a critical threshold, the net energy transfer from the fluid to the tube surpasses the energy dissipated through the system’s inherent damping. This energy imbalance induces large-amplitude vibrations, culminating in catastrophic structural failure within few vibration cycles.

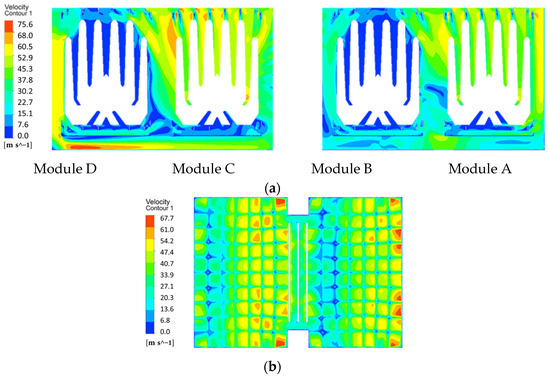

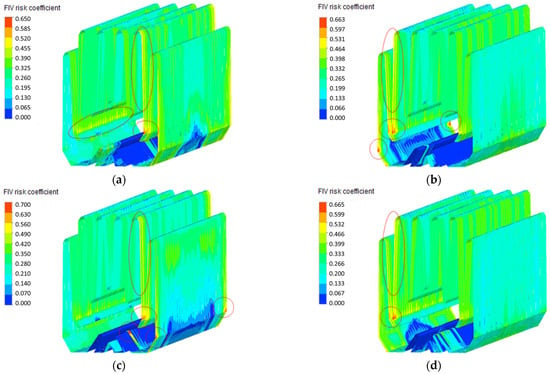

3.2.1. Steam-Flow-Induced Vibration Risk Coefficient Characterization Under VWO Condition

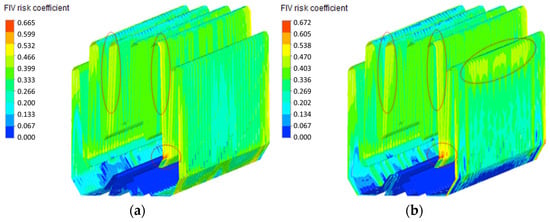

Figure 11 presents the distribution of FIV risk coefficients across the outermost side of the bundle area under the VWO condition. Results indicate relatively uniform FIV risk coefficients α (generally <0.5) throughout most bundle regions. However, maximum risk coefficients (up to 0.7) occur at the condenser’s peripheral cooling pipes, particularly at branch-like channel inlets and bundle corners, indicating heightened susceptibility to flow-excited vibration in these zones. This elevated risk correlates with locally elevated steam velocities in these specific regions.

Figure 11.

Flow-induced vibration risk coefficient α distribution across the outermost side of the bundle area under VWO condition: (a) Module A; (b) Module B; (c) Module C; (d) Module D. (The red circle represents the high FIV risk area).

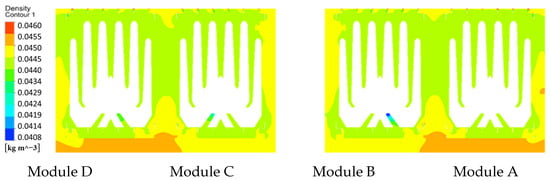

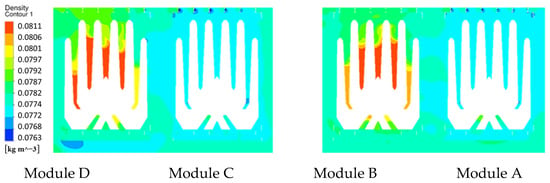

Figure 12 displays the steam density distribution at the cross-section at x = 1 m under the VWO condition. The highest density regions occur beneath modules A and D, likely resulting from steam accumulation below the tube bundle that impedes flow. Above the bundle, steam density is comparatively lower, though the spatial variations remain moderate throughout the domain.

Figure 12.

Cross-sectional (x = 1 m) distribution of density t under VWO condition.

3.2.2. Partial-Load Steam-Flow Vibration Risk Assessment with Modules A/C Active

Figure 13 displays the FIV risk coefficient α distribution across the outermost side of the bundle area under partial-load operation (Modules A/C active). Maximum risk coefficient reaches 0.67, with elevated-risk zones concentrated at branch-like channel inlets and some corners within Modules A and C bundles.

Figure 13.

Distribution of FIV risk coefficient α of the condenser across the outermost side of the bundle area under partial-load operation (Modules A/C active): (a) Module A; (b) Module C. (The red circle represents the high FIV risk area).

Figure 14 displays the steam density distribution at x = 1 m under partial-load operation (Modules A/C active). Elevated densities above inactive modules B and D result from flow obstruction due to shutdown conditions, impeding steam discharge. These findings demonstrate that module operational status governs density distribution patterns within condenser tube bundles.

Figure 14.

Cross-sectional (x = 1 m) distributions of steam density with modules A/C active.

3.2.3. Partial-Load Steam-Flow Vibration Risk Assessment with Modules B/D Active

Figure 15 presents the FIV risk coefficient α distribution across the outermost side of the bundle area under partial-load operation (Modules B/D active). Maximum risk coefficient α reaches 0.74, with high-risk zones concentrated at branch-shaped channel inlets and some corners within inactive Modules A and C bundles.

Figure 15.

Distribution of FIV risk coefficient α of the condenser across the outermost side of the bundle area under partial-load operation (Modules B/D active): (a) Module B; (b) Module D. (The red circle represents the high FIV risk area).

Figure 16 displays the steam density distribution at x = 1 m under partial-load operation (Modules B/D active). Elevated densities in upper zones of inactive Modules A/C result from shutdown-induced flow obstruction, causing steam accumulation.

Figure 16.

Cross-sectional (x = 1 m) distribution of density with Modules B/D Active.

To quantitatively summarize and compare the key findings across the three operational scenarios, Table 4 presents the velocity, and the FIV risk coefficient (α).

Table 4.

Summary of Key Parameters.

Analysis of Table 4 reveals that the highest FIV risk (α = 0.74) occurs not at the maximum flow rate (VWO), but during the BD Activated partial-load condition. This indicates that the inherent flow instability (e.g., strong swirling or channeling) under this specific off-design operation is a more critical driver of vibration than the average flow velocity itself. The VWO condition, while having the highest velocity, results in a more stable flow field with a lower relative risk. The non-monotonic relationship between flow velocity and the FIV risk coefficient is a pivotal finding. This demonstrates conclusively that inherent flow instability during specific off-design operations is a more critical driver of FIV than the average flow velocity.

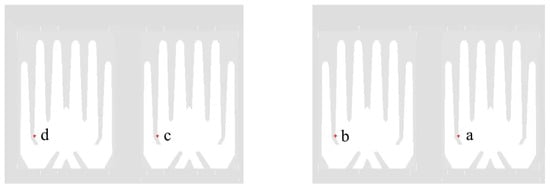

For an intuitive comparison, fixed points were selected to analyze the trends of FIV values under different operating conditions. These points (a, b, c, d) are located in the high-risk excitation region of the tube bundle, as shown in Figure 17. The resultant curves are presented in Figure 18. Analysis reveals that when the module is closed, the absence of forward steam flushing results in a very low flow rate, leading to minimal FIV. In contrast, under steam flushing conditions, the increase in flow velocity corresponds to higher FIV values. However, the FIV does not exhibit a linear increasing trend with flow velocity, which is primarily attributed to the influence of factors such as density.

Figure 17.

The points (a, b, c, d) selected in the high-risk excitation region of the tube bundle.

Figure 18.

Velocity and FIV risk coefficient Relationship Curve at the points (a, b, c, d) selected.

The main limitations of this work stem from its theoretical nature, including modeling simplifications in turbulence and one-way fluid–structure coupling, while also ignoring the influence of FSI. This simplification means that we may underestimate the vibration amplitude at specific frequencies, especially when the structural natural frequency is close to the fluid vortex shedding frequency. However, the main objective of this study is to identify high-risk areas and the spatial distribution of excitation forces. The most critical next step is the experimental validation of these simulation results. Future work must therefore focus on correlating the model predictions with measured data (e.g., outlet pressures or vibration signatures) from an operational plant or a scaled experimental setup. Subsequent studies should also extend the analysis to transient conditions, validating the predicted quantitative relationship between operational parameters and FIV risk and incorporate two-way fluid–structure interaction (FSI) for improved accuracy.

4. Conclusions

This study performed a comprehensive flow-induced vibration (FIV) risk assessment of nuclear condenser cooling tubes using a full-scale CFD model that integrated the exhaust cylinder, throat section, and tube bundle. Through numerical simulations under three operational scenarios—VWO and two partial-load configurations—the following key findings were obtained:

- (1)

- A full-scale CFD model revealed distinct steam flow patterns, with velocity decreasing from top to bottom and exhibiting non-uniformity at the throat exit. Under VWO conditions, velocity maxima localized near the shell wall.

- (2)

- Partial-load operations led to steam channeling and swirling due to module shutdowns, with all configurations showing FIV risk coefficient peaks at geometrically complex regions such as branch-shaped channel inlets subjected to direct steam impingement and corners of tube bundles. These findings offer a practical foundation for enhancing nuclear condenser safety by enabling targeted monitoring through strategic sensor placement in high-risk zones, guiding inherently safer design optimizations based on revealed flow mechanisms, and supporting the development of operational strategies that avoid risk-aggravating conditions by understanding off-design flow patterns.

- (3)

- The purpose of our article is to identify the most dangerous areas in order to install sensors in these areas and improve the intelligence level of the system. On this basis, we can carry out further structural optimization in the future. Although this study remains a theoretical investigation without experimental validation, but this work will be carried out in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.P.; methodology, X.L. (Xibin Li), J.C. and W.W.; software, Z.C.; validation, X.L. (Xing Liu), J.C. and M.L.; formal analysis, M.L.; investigation, Z.C., C.W. and M.L.; data curation, X.L. (Xing Liu) and J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.C., C.W. and Y.H.; writing—review and editing, M.L.; supervision, J.C., Z.Z. and M.L.; project administration, X.L. (Xibin Li), J.C. and W.W.; funding acquisition, Y.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Yan Ping, Xing Liu, Xibin Li, Wenhua Wu, Jian Chen and Zhuhai Zhong were employed by the Dongfang Electric Corporation Dongfang Turbine Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FIV | Flow Induced Vibration |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| VWO | Valve Wide Open |

| LP | Low Pressure |

| LES | Large Eddy Simulation |

| RANS | Reynolds Averaged Navier–Stokes |

| SHM | Structural Health Monitoring |

| FSI | Fluid Structure Interaction |

Nomenclature

| n | Number of spans | ||

| P | the turbulent kinetic energy generation term | ||

| b | exponent | S | center distance of the heat exchange tube, mm |

| Cω | a cross diffusion term | tb | thickness of the tube sheet |

| d0 | Outer diameter of cooling pipe, mm | t | Time, s |

| di | Inner diameter of cooling pipe, mm | uj | the component of velocity in the j direction, m/s |

| d2 | Outer diameter of cooling pipe, mm | V | actual flow rate of steam, m/s |

| Dk | the diffusion term in the k equation | Vc | critical cross flow velocity, m/s |

| Dω | the diffusion term in the ω equation | xj | the component of x in the j direction |

| E | Elastic modulus, MPa | ||

| fn | natural frequency, Hz | ||

| f1 | First order natural frequency, Hz | ||

| Kc | Empirical coefficient | Greek letters | |

| k | turbulent kinetic energy | λn | Frequency constant |

| l | Span, m | ω | the specific dissipation rate |

| lm | Span, m | δ | Logarithmic decay rate |

| m | Mass per unit length of cooling pipe, kg/m | β | the model constant |

| mi | mass of fluid in the heat exchange tube, kg/m | β* | the model constant |

| m0 | virtual mass of fluid outside the tube, kg/m | ρ | Density of cooling pipe, kg·m−3 |

| m1 | the mass of empty tube, kg/m | α | FIV risk coefficient |

References

- Giovannini, M.; Lorenzini, M. Numerical verification of the condenser finite volume model. In Proceedings of the 78th Associazione Termotecnica Italiana Annual Congress on Energy Transition: Research and Innovation for Industry, Communities and the Territory, ATI 2023, Carpi, Italy, 14–15 September 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, D.G.; Zhang, Z.W.; Lai, Y.T.; Zhang, G.D. Research on failure mechanism of condenser titanium tube in nuclear power plant. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Advanced Materials and Intelligent Manufacturing, ICAMIM 2021, Nanning, China, 20–22 August 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. Cause Analysis of tube burst of the condenser in a power plant. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Advanced Materials and Intelligent Manufacturing (ICAMIM 2022), Guangzhou, China, 5–7 August 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patankar, S.V.; Spalding, D.B. Computer analysis of the three-dimensional flow and heat transfer in a steam generator. Forsch. Im Ingenieurwesen 1978, 44, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavdinova, M. Mathematical model of a steam turbine condenser. Therm. Eng. 2022, 69, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shempelev, A.G.; Suvorov, D.M. Evaluation of the effectiveness of using various methods for calculating steam turbine condensers equipped with built-in bundles. Power Technol. Eng. 2024, 58, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.J.; Yin, T.Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, W.; Zhu, P.W.; Luo, K.; Kuang, Y.; Liu, J.; Huang, J.J.; Huo, B.; et al. A novel approach for the optimal arrangement of tube bundles in a 1000-MW condenser. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. A 2023, 24, 1140–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, S.; Chen, J.; Che, Y.H.; Wang, G.S. Research on steam flow excited vibration of nuclear power condenser based on full three-dimensional numerical simulation technology. AIP Adv. 2022, 12, 035015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, P.; Yan, B. Research on the Flow-induced Vibration of Multiple Flexible Tandem Cylinders Based on Large Eddy Simulation. J. Gansu Sci. 2023, 35, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Bai, X.; Zhai, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, D.; Yang, Y.; Tang, D. Numerical Simulation Research on the Vibration of Helical Tube Arrays Under Transverse Flow. Energies 2022, 15, 9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerson, P.; Lewis, M.; Barton, N.; Orre, S.; Lunde, K.; Klinkenberg, A.; Macchion, O.; Challabotla, N.R.; Belfroid, S. Multiphase Flow Induced Vibrations at High Pressure: CFD Analysis of Multiphase Forces. In Proceedings of the ASME 2021 40th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Virtual, Online, 21–30 June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jin, X.; Cheng, P.; Han, H.; Li, Y. Combining CFD and artificial neural network techniques to predict Vortex-induced vibration mechanism for wind turbine tower Hoisting. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2022, 114, 106688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, U.; Muhammad, A.; Muhammad, A.K.; Fuad, A. Thermal analysis and performance investigations of shell and tube heat exchanger using numerical simulations. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2024, 38, 2341015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Hou, Y.; Qian, F. Dynamic operational characteristics for condenser and correlative equipment. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 526, 012170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlas, P.; Ibrahimi, D.; Varelis, G.E.; Peng, D. FIV Assessment of Piping Systems Using Vibration Screening and Advanced Analysis Methodologies. In Proceedings of the ASME 2024 43rd International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Singapore, 9–14 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Fan, T.; Chen, J.; Bai, Y. Experimental investigations on Flow-induced vibration characteristics of fuel rod with an independent channel for small lead-based Reactor. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2024, 61, 1360–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Q. Pressure transient analysis on the condenser of the hpr1000 nuclear power unit. Energies 2024, 17, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Chang, S.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, L. Mathematical Simulation on the Transient Flow and Bubble Distribution Within a Bifurcated Submerged Entry Nozzle. Steel Res. 2025. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Han, A.; Jiang, W.; Yue, Y.N.; Xie, D.M. A biomimetic design of steam turbine blade to improve aerodynamic performance. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2022, 181, 107782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardina, J.E.; Huang, P.G.; Coakley, T.J. Turbulence Modeling Validation, Testing, and Development. In NASA Technical Memorandum; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19970017828/downloads/19970017828.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Menter, F.R. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J. 1994, 32, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabani, S.; Majkut, M.; Lakzian, S.E. An investigation comparing various numerical approaches for simulating the behaviour of condensing flows in steam nozzles and turbine cascades. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 2024, 158, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 151-2014; Heat Exchangers. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China, General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine, China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2014. Available online: https://openstd.samr.gov.cn/bzgk/gb/newGbInfo?hcno=892BA38ED351756BEBFC9F59868E4631 (accessed on 5 December 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).