Abstract

The persistence of organochlorine pesticides, such as Aldrin and Dieldrin, in water bodies worldwide necessitates the development of efficient Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) for water treatment or remediation. However, comparative studies evaluating the performance of distinct plasma discharge geometries against acoustic cavitation for the mineralization of these specific chlorinated cyclodienes remain scarce. This study investigates the comparative efficacy of four non-thermal technologies, ultrasound, dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma, glow discharge plasma, and corona discharge plasma, for the simultaneous degradation of Aldrin and Dieldrin in a model contaminated aqueous solution (5 μg/L). All experiments followed a 32-factorial design, and the residual concentrations of these pesticides were quantified by GC-MS after Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME). All four methods achieved high degradation efficiencies, ranging from 92.5% to 100% for Aldrin and 92.6% to 99.2% for Dieldrin. Corona discharge plasma achieved the highest performance, resulting in 100% removal of Aldrin. However, ultrasound proved to be the most advantageous, achieving a 98% removal efficiency for both pesticides under its mildest conditions (3125 W/L ultrasonic power density for 3 min). The study confirmed that while Aldrin is highly susceptible to these technologies, Dieldrin remains the limiting factor for regulatory compliance. Chemical analysis did not conclusively identify any organic degradation by-products, suggesting that these AOPs may promote complete mineralization of the pollutants.

Keywords:

pesticide; cold plasma; ultrasound; non-thermal technology; water treatment; Aldrin; Dieldrin 1. Introduction

The contamination of aquatic environments by a wide array of Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs) represents one of the most significant environmental challenges of the 21st century [1,2]. This diverse group of micropollutants includes substances from various sources, such as pharmaceuticals (e.g., antibiotics and hormones), personal care products (e.g., UV filters and synthetic fragrances), and numerous industrial and agricultural chemicals. Among the most problematic are Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), a subclass that includes synthetic pesticides and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), widely known as “forever chemicals” due to their extreme resistance to degradation [3,4].

The continuous introduction and persistence of these compounds in water bodies are a growing threat to ecological balance and human health. These compounds are introduced into water sources through various pathways, including industrial effluents, agricultural runoff, and the disposal of consumer products such as medicines, personal care products, non-stick cookware, firefighting foams, and stain-resistant textiles. Their chemical stability, which makes them effective in commercial applications, also leads to their presence and accumulation in ecosystems and human tissues [1,2].

A critical health concern associated with many of these pollutants is their ability to act as endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs). By mimicking or antagonizing natural hormones, EDCs can interfere with the body’s endocrine system, potentially leading to developmental defects, reproductive issues, immune system dysfunction, and an increased risk of certain cancers. The presence of such compounds in drinking water, even at trace concentrations, poses a substantial threat to public health, making their removal essential for ensuring water safety and security [5].

The global reliance on synthetic agrochemicals is a primary driver of water contamination. The intensification of agricultural practices is reflected in a steady, significant increase in pesticide use worldwide. According to recent data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the total quantity of pesticides used has doubled since 1990 [6]. This upward trajectory has been maintained, showing a 13% increase over the last decade. More recently, in 2022, pesticide use increased by 4% compared to the previous year [6]. The continuous and intensifying application of agrochemicals raises great concerns from both environmental and public health standpoints, as it increases the loading of these persistent compounds into soil and aquatic ecosystems, ultimately threatening the safety of drinking water resources.

The recalcitrant nature of many CECs, including pesticides, renders conventional water treatment processes, such as coagulation, sedimentation, and filtration, ineffective for their removal. This technological gap highlights the need for more robust and efficient purification strategies. In response to this environmental and health threat, research on the development of Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs), which utilize highly reactive species such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH) to degrade complex and stable organic molecules into less harmful substances, is increasing [7,8,9].

Among these AOPs, ultrasound (sonolysis) and cold plasma have emerged as promising and innovative solutions [7,10,11]. Both technologies offer several distinct advantages, such as operating efficiently at ambient temperature and pressure, and not requiring the addition of external chemical reagents, which minimizes the risk of forming secondary toxic byproducts. The energy needed to conduct these processes can be supplied by renewable sources, thereby enhancing the treatment’s sustainability. Furthermore, these methods are characterized by short processing times and satisfactory degradation efficiency when compared to other techniques, making them suitable alternatives for water purification [7,12].

Numerous studies have reported the effectiveness of ultrasound as a standalone or hybrid Advanced Oxidation Process (AOP) for degrading a wide range of pesticides in aqueous solutions. Ultrasound generates hydroxyl radicals (•OH) via acoustic cavitation, thereby degrading pesticides. Research has shown that the herbicide atrazine can be degraded entirely in under 20 min when ultrasound is combined with Fenton’s reagent (sono-Fenton process) [13]. In another study focusing on the organophosphate insecticide chlorpyrifos, sonolysis alone achieved over 90% degradation after 120 min of treatment [14]. Recalcitrant organochlorines, such as lindane, have been treated, attaining 88% removal after 100 min of sonication [15]. These examples highlight ultrasound’s ability to break down diverse, complex pesticide molecules, reinforcing its potential as a water-treatment and remediation technology.

Several studies have also shown that cold plasma is a potential technology for removing pesticides from water. Its effectiveness comes from generating a mix of reactive species, such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH), ozone, singlet oxygen, molecular hydrogen, UV radiation, and other ions and free radicals, that attack and break down pollutant molecules [16]. Research has shown that the organophosphate insecticide malathion degrades when exposed to cold plasma, achieving over 70% removal from water in 8 min [16]. The technology is also effective against more persistent compounds, such as the herbicide atrazine, which has demonstrated 99% degradation within a 40-min treatment period using a dielectric barrier discharge plasma system [17]. Furthermore, cold plasma has been used to treat the insecticide diazinon, reporting a degradation of 9.4 mg/L within 30 min [18]. These examples demonstrate the potential of cold plasma to treat diverse and structurally complex pesticides.

Despite the proven efficacy of Advanced Oxidation Processes for various agrochemicals, there is a scarcity of literature reporting the decomposition of Aldrin and Dieldrin using cold plasma technologies. Specifically, the application and comparative efficacy of glow discharge, dielectric barrier discharge (DBD), and corona discharge plasmas for the remediation of these specific organochlorine pesticides have not been extensively investigated. This lack of data highlights the need to evaluate these non-thermal technologies as viable alternatives to conventional treatments.

This study targets Aldrin and Dieldrin, synthetic organochlorine insecticides known for their historical agricultural use and severe environmental impacts. Although Aldrin was extensively applied for soil pest control against termites and corn rootworms, it rapidly oxidizes in biological and ecological systems to form its more stable and toxic epoxide, Dieldrin. Consequently, Dieldrin represents the primary toxicological concern, persisting in ecosystems long after the release of the parent compound [19].

The primary environmental issue with these pesticides is their extreme persistence. They are highly resistant to degradation, with literature data indicating that the half-life of Aldrin in the environment is approximately 3.1 months. Its epoxidation leads to the formation of Dieldrin, which is significantly more recalcitrant, exhibiting a half-life of about 29.7 months, underscoring the long-term threat these compounds pose to soil and water ecosystems [20]. Due to their lipophilic nature, they are prone to bioaccumulation in organisms’ fatty tissues and subsequent biomagnification as they move up the food chain [21]. This has had a serious impact on wildlife, particularly top predators such as fish and birds of prey.

Contamination of water bodies is a significant threat associated with Aldrin and Dieldrin. Their primary route into aquatic ecosystems is through agricultural runoff and soil erosion, which carry the pesticides into rivers, lakes, and groundwater [19]. Although they have low water solubility, their persistence allows them to remain in water and bind to sediments for long periods, thereby acting as a long-term source of contamination. This poses a direct risk to drinking water safety. Their chemical stability makes them resistant to conventional water treatment methods, necessitating the use of advanced technologies to protect public health. Due to these profound risks, the use of Aldrin and Dieldrin has been banned or severely restricted globally under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants. Nonetheless, the threat posed by these chemicals is not merely historical. Despite the international agreement, their use persists in some parts of the world. This lack of control in certain regions means that Aldrin and Dieldrin persist as active sources of pollution, representing an ongoing danger to water sources and public health.

The concentrations of Aldrin and Dieldrin in the environment range from several nanograms per liter (ng/L) to low micrograms per liter (μg/L), reflecting the varied history of their use and environmental conditions worldwide. These levels are highly dependent on factors like proximity to historical agricultural areas, soil characteristics, and rainfall events that trigger runoff. For instance, in regions with extensive historical use but long-standing bans, legacy contamination is still evident. Monitoring in the Great Lakes of North America has detected dieldrin in surface waters, with typical background concentrations in the low nanogram per liter range (0.1 to 2 ng/L) [22].

Studies in more intensively agricultural basins, particularly those with soils that retain high contaminant loads, reveal more concerning levels. Research conducted in the Paraná River basin in Brazil and Argentina has reported Dieldrin concentrations ranging from 15 to 50 ng/L, with peaks often occurring after rainfall [23]. These levels are at or above the drinking water guideline set by the World Health Organization (30 ng/L). At “hotspots” or regions with less stringent regulation, concentrations approach the microgram-per-liter scale. For example, studies in contaminated river systems in parts of Asia have reported Dieldrin levels exceeding 100 ng/L (0.1 µg/L) [24]. In Brazil, monitoring data from the SISAGUA system (2018–2022) indicated that these pesticides are frequently detected in public water supply systems, with concentrations reaching up to 5 mg/L in certain regions [25]. These examples demonstrate that the persistence of Aldrin and Dieldrin continues to cause significant and geographically widespread pollution of water resources.

In this context, the present study aims to investigate and compare the efficacy of four non-thermal advanced oxidation processes (ultrasound, dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma, glow discharge plasma, and corona discharge plasma) for the degradation of the persistent organochlorine pesticides Aldrin and Dieldrin in an aqueous solution. While both ultrasound and cold plasma are non-thermal AOPs, they operate through fundamentally different mechanisms. Ultrasound relies on acoustic cavitation to generate localized hotspots and hydroxyl radicals [15]. In contrast, cold plasma utilizes high-voltage electrical discharges to produce a broader cocktail of reactive species, including ozone, UV radiation, and high-energy electrons [16]. A comparative analysis of these distinct energy sources (mechanical versus electrical) is essential to determine which degradation pathway is most effective for overcoming the chemical stability of these pesticides.

This research evaluates the degradation efficiency of each technology under various operational parameters, including power, frequency, and treatment time, to determine the optimal conditions for their removal. One of the main objectives is to determine which of these technologies is more efficient in treating water contaminated with these pollutants, with a focus on achieving residual concentrations that comply with established drinking water quality standards [6].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Aldrin and Dieldrin, analytical standard grade, were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). Both compounds are classified as Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) under the Stockholm Convention and were selected for this research due to their high chemical stability and slow environmental degradation.

For the degradation experiments, an aqueous solution containing both Aldrin and Dieldrin at an initial concentration of 5 µg/L each was prepared. Distilled water was selected as the solvent to establish a baseline for fundamental degradation kinetics, thereby eliminating the interference of radical scavengers typically present in complex environmental matrices. This allows for the direct evaluation of the technologies’ intrinsic oxidative potential. This specific concentration was chosen to reflect environmental relevance, as it represents the average level observed in Brazil’s public water supply systems, based on monitoring data from the SISAGUA (Information System for the Surveillance of Water Quality for Human Consumption) between 2018 and 2022 [25].

2.2. Degradation Processes

2.2.1. Ultrasound Treatment

For the ultrasonic treatments, a Unique DES500 (Unique, Indaiatuba, Brazil) ultrasound system (19 kHz) equipped with a controller, transducer, and probe was used. The experiments were carried out in batch mode. For each test, 80 mL of the aqueous solution containing the pesticides was placed in a jacketed beaker. The temperature was maintained at 25 °C using a Tecnal TE-2005 (Tecnal, Piracicaba, Brazil) thermostatic bath, which recirculated water through the beaker’s jacket (Figure 1).

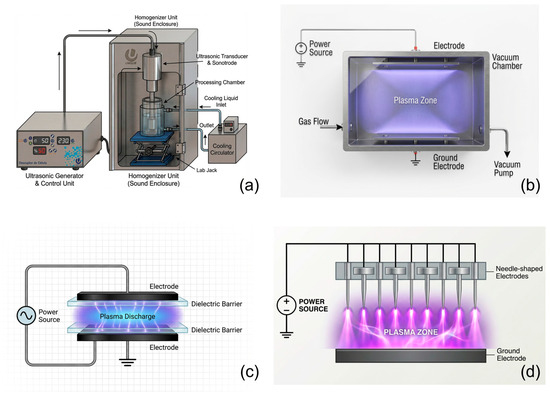

Figure 1.

Schemes of the ultrasound and plasma systems used in this study: (a) ultrasound system; (b) glow discharge plasma; (c) dielectric barrier plasma; and (d) corona discharge plasma.

To identify the best operating conditions, a 32 full factorial design was implemented, varying two parameters at three levels each, to evaluate the process parameters and determine their optimal operating conditions. The variables investigated were the ultrasound power density at 3125, 4690, and 6250 W/L (corresponding to 50%, 75%, and 100% of the equipment’s maximum power), and the processing time at 3, 6.5, and 10 min. All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

2.2.2. Glow Discharge Cold Plasma Treatment

For glow-discharge cold plasma treatments, a Plasma Etch PE-50 vacuum plasma system (Plasma Etch, Carson City, NV, USA) equipped with a plasma chamber and a vacuum pump was used (Figure 1). The degradation process was conducted in batch mode. For each experimental run, a 40 mL sample of the pesticide-doped aqueous solution was placed in a 50 mL Falcon tube. A headspace was left in the tube to allow plasma energy to ionize the air inside the container, contributing to the degradation process. The plasma itself was generated using synthetic air as the process gas.

To identify the most effective treatment conditions, a 32 full factorial design was used, varying gas flow rate and processing time at three levels each. The gas (synthetic air) flow rates were set at 10, 20, and 30 mL/min, and the processing times were set at 5, 10, and 15 min. All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

2.2.3. Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma Treatment

For the dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma treatments, an in-house-built system powered by an Inergiae PLS0130 high-voltage power supply (Inergiae, Florianópolis, Brazil) was used (Figure 1). The reactor consisted of two flat, circular aluminum plates (8 cm in diameter) serving as electrodes, separated by acrylic plates (3 mm thick) that served as dielectric barriers. The experiments were conducted in batch mode at ambient temperature (25 °C) and pressure. For each run, a 25 mL sample of the pesticide-doped aqueous solution was placed in a Petri dish, which was then positioned between the electrodes (1 cm gap), with the liquid surface 0.5 cm from the upper electrode. The plasma was generated using atmospheric air as the process gas.

The operational parameters investigated were frequency and treatment time, while the voltage was held constant at 15 kV. A 32 full factorial design was implemented, varying the frequency at three levels (50, 500, and 1000 Hz) and the processing time at three levels (5, 10, and 15 min). All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

2.2.4. Corona Discharge Plasma Treatment

For the corona discharge plasma treatments, the system was powered by an Inergiae ALT0350PD high-voltage power supply (Inergiae, Florianópolis, Brazil). The reactor setup consisted of sixteen needle-type electrodes positioned 2 cm from the flat grounding surface (Figure 1). The experiments were conducted in batch mode under ambient temperature and pressure. For each test, a 25 mL sample of the pesticide solution was placed in an uncovered Petri dish and positioned directly below the pin electrodes (1.5 cm). The plasma was generated using atmospheric air.

A 32 full factorial design was used, varying frequency and treatment time while keeping the voltage constant at 15 kV. The frequency varied at three levels (5000, 10,000, and 15,000 Hz), and the processing time at three levels (5, 10, and 15 min). All experiments were carried out in triplicate.

2.3. Chemical Analysis

2.3.1. Chromatograph Analysis of Pesticides

The degradation efficiencies of the pesticides and the potential formation of degradation byproducts were quantified and identified using Gas Chromatography coupled with Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS).

Before chromatographic analysis, the samples were extracted using Solid-Phase Micro Extraction (SPME). An 85 μm thick Polyacrylate fiber coupled to a holder for the extraction of the pesticides. A volume of 35 mL of the doped aqueous solution was transferred to a 40 mL vial sealed with a screw cap and silicone septum. The extraction was performed by immersing the fiber directly into the sample for 20 min at 65 °C with magnetic stirring to facilitate the adsorption of the compounds onto the fiber. Following the extraction period, the fiber was transferred to the gas chromatograph for 8 min of pesticide desorption. This technique was used because it can extract Aldrin and Dieldrin even at trace concentrations.

A GC-MS system from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA), model Focus GC with a DSQII mass spectrometer, was employed for the analysis. The separation of the pesticides utilized a DB-5 capillary column with dimensions of 30 m in length, 0.25 mm internal diameter, and 0.25 μm film thickness. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1.2 mL/min. The sample injection was performed in splitless mode, with the injector temperature set to 250 °C. The GC oven’s temperature program began at 90 °C, held for 1 min, and then ramped to 280 °C at 6 °C/min. Subsequently, the temperature was increased to 300 °C at 15 °C/min and held for 5 min, resulting in a total chromatographic run time of 27 min.

For detection and quantification, the mass spectrometer operated in electron-impact mode at 70 eV. The ion source temperature was maintained at 250 °C, and the transfer line temperature at 280 °C. Quantification of the compounds was performed using Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM) mode. To identify potential degradation byproducts, the instrument was operated in full-scan mode over the mass-to-charge ratio range of 40−500 m/z. Compound identification was based on the NIST library and pesticide standards.

The analytical method was validated for linearity, precision, and accuracy. Quantification was carried out using the external standard method. The calibration curves covered a concentration range of 0.05 to 20 μg/L for both compounds, with linear correlation coefficients (R2) greater than 0.99. The Limits of Detection (LOD) and Quantification (LOQ) were calculated based on the signal-to-noise ratio, ensuring the method’s capability to quantify residual pesticide concentrations below the regulatory limits. The Limit of Detection (LOD) was determined to be 0.01 μg/L for both Aldrin and Dieldrin. The Limit of Quantification (LOQ) was set at 0.05 μg/L, corresponding to the lowest standard concentration on the calibration curve.

2.3.2. Determination of Ultrasound and Plasma Free Radicals

The determination of plasma reactive species followed the methods described by Lankone et al. [26] (hydroxyl radicals) and Ovenston and Rees [27] (hydrogen peroxide). Superoxide anion, singlet oxygen, and ozone were assessed according to Magnani et al. [28], with all analyses conducted in triplicate.

2.4. Energy Efficiency Calculations

To evaluate the economic viability of the different technologies, the electrical energy consumption was monitored and calculated. The Total Energy Consumption (Etotal), expressed in kilowatt-hours (kWh), was calculated using Equation (1):

where P represents the average power (W) measured during the treatment and t denotes the treatment time (s).

To compare the efficiency of pollutant removal across different reactor geometries and initial concentrations, the Energy Efficiency (EE) was calculated as the energy required to remove 1 μg of pollutant (kWh/µg). This was determined using Equation (2):

where Etotal is the total energy consumption (kWh), C0 and Cf are the initial and final concentrations of the pesticide (μg/L), and V is the volume of the treated solution (L).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3). The results were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD). To evaluate the statistical significance of differences between treatments, the data were subjected to a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). When significant differences were detected (p < 0.05), Tukey’s post hoc test was applied to separate the means. Superscript letters in the results tables indicate statistically significant differences between the experimental conditions.

3. Results

The experimental results for the degradation of Aldrin and Dieldrin obtained under the various operational conditions are summarized in Table 1. Data quantified by GC-MS using the Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) technique allowed us to calculate the degradation of these pesticides as percentages.

Table 1.

Degradation of the pesticides Aldrin and Dieldrin in aqueous solution subjected to ultrasound and plasma treatments. Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s test.

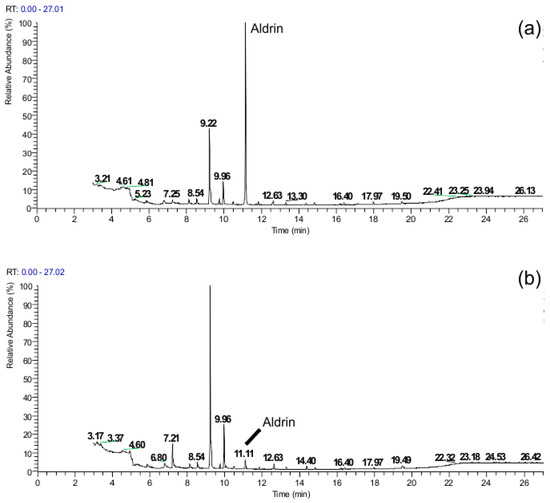

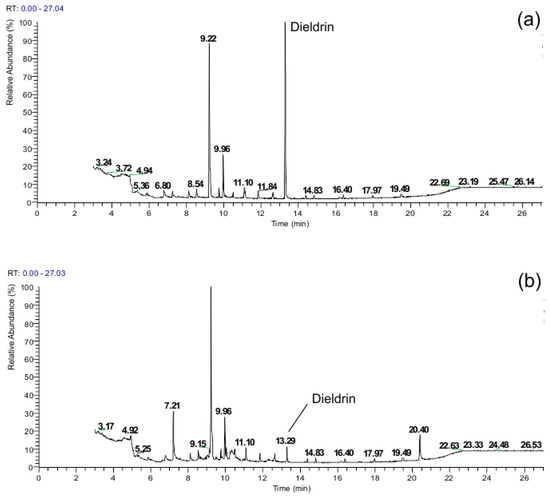

To visualize the efficiency of the degradation process, the gas chromatograms of the samples were analyzed before and after treatment. Figure 2 and Figure 3 present the chromatographic profiles of Aldrin and Dieldrin, respectively, obtained after DBD plasma-treatment at 50 Hz for 15 min. The chromatograms reveal significant degradation of the characteristic peaks of the parent compounds after the treatment time, confirming the high degradation efficiency quantified in Table 1. These profiles are representative of the results obtained across the other studied systems (ultrasound, glow discharge, and corona discharge), which exhibited similar patterns of peak elimination.

Figure 2.

Chromatogram of Aldrin (a) in the initial solution and (b) after DBD plasma processing at 15 kV and 50 Hz for minutes.

Figure 3.

Chromatogram of Dieldrin (a) in the initial solution and (b) after DBD plasma processing at 15 kV and 50 Hz for minutes.

The degradation of both Aldrin and Dieldrin by ultrasound was efficient. Dieldrin removal was consistently high, maintaining efficiencies above 98.6% across all tested power densities and time settings, while Aldrin achieved degradation ranging from 80.8 to 99.4%. The highest performance for both pesticides, 99.2% for Dieldrin and 98.9% for Aldrin, was observed under the mildest operational conditions tested (3 min at 3125 W/L ultrasonic power density). This operational characteristic is relevant for practical application, as it suggests that the acoustic cavitation mechanism effectively produces the necessary reactive species at low energy inputs, demonstrating that high degradation efficiency can be achieved without the economic burden of maximizing power or exposure time.

Table 2 presents the normalized concentrations of hydroxyl radicals, superoxide anions, * and hydrogen peroxide produced by ultrasound and various plasma systems. The results reveal distinct oxidative profiles for each technology.

Table 2.

Relative concentration of free radicals and reactive species produced by ultrasound and plasma, normalized to the maximum observed value (dimensionless) *.

The corona discharge system demonstrated the highest capacity to generate hydroxyl radicals and hydrogen peroxide, achieving the highest hydroxyl radical concentration across all tested frequencies. Hydrogen peroxide generation was also dominant in this system, reaching a maximum normalized value of 1.0 at 5000 Hz. However, it exhibited a decreasing trend as the frequency increased to 15,000 Hz. The production of superoxide anions was the lowest in this system. In contrast to the corona plasma, both glow discharge and ultrasound favored the production of superoxide anions. The glow discharge plasma produced the highest levels of superoxide anions among all systems, peaking at 10 mL/min. The generation of hydroxyl radicals and hydrogen peroxide remained low compared to the amount produced by the corona plasma. Similar to glow discharge, ultrasound showed significant superoxide anion generation. However, it produced slightly higher hydroxyl radical levels compared to glow discharge and DBD plasmas, particularly at higher power densities. The DBD plasma system produced the least overall of the measured reactive species in the liquid phase. This suggests that, under these specific experimental conditions, the DBD system may generate other species not quantified here (such as ozone or gaseous species), or that the transfer of these radicals to the liquid phase was less efficient than in the corona and glow discharge plasmas.

The observed difference in degradation rates can be attributed to both chemical and physical factors. Chemically, the epoxide group in Dieldrin is more resistant to oxidation than the double bond present in Aldrin. Physically, ultrasonic degradation efficiency is also influenced by the pollutant’s hydrophobicity, which dictates its proximity to the cavitation bubble interface. Aldrin, being more hydrophobic (log Kow ≈ 6.5), accumulates more readily at the bubble surface compared to the slightly more polar Dieldrin (log Kow ≈ 5.4), thereby maximizing its exposure to the localized high temperatures and hydroxyl radical attack.

The use of Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) plasma provided another effective method for degrading both Aldrin and Dieldrin, yielding higher Aldrin degradation efficiency. Degradation of Aldrin consistently exceeded 99.5% across the entire tested operational range (50 Hz to 1000 Hz), confirming the technique’s robustness regardless of frequency variation. For Dieldrin, removal rates were also very high, peaking at 95.7% at the lowest processing time and frequency (50 Hz, 5 min). Both Aldrin and Dieldrin showed high degradation (>95%), indicating that the generation of plasma reactive species, mainly hydroxyl radicals, within the plasma zone is sufficiently potent at low-to-moderate energy levels to degrade these stable cyclic compounds [16].

The treatment of Aldrin and Dieldrin using glow discharge plasma demonstrated consistently high and stable degradation efficiency, positioning it as a reliable technique for water treatment. For both Aldrin and Dieldrin, removal rates remained high, ranging from 95.8% to 99.7% for Aldrin and 96.7% to 97.8% for Dieldrin. This narrow distribution of degradation values, regardless of variations in gas flow (10 to 30 mL/min) or exposure time (5 to 15 min), highlights the plasma’s robust ability to generate the necessary degrading species, primarily through photolysis, UV-induced homolysis of water, and formation of plasma reactive species such as molecular oxygen and hydrogen as previously reported by our group for these systems [29]. Aldrin reached its maximum degradation (99.7%) in this system under moderate conditions (30 mL/min flow for 15 min), confirming that the plasma atmosphere can transfer energy effectively to the aqueous solution to break down these two persistent molecules.

The corona discharge plasma was also found to be an effective method for decomposing the persistent pollutants Aldrin and Dieldrin in water. This technique achieved the highest degradation efficiency in the study, resulting in the total removal (100%) of Aldrin. Dieldrin was also removed with consistently high rates, peaking at 98.2%. A clear operational trend was observed for both pesticides. Increasing the exposure time to plasma improved the degradation rate, with the best results found at the maximum tested duration of 15 min. This performance highlights the ability of the high-energy electric field generated by corona discharge to directly produce potent oxidizing species at the water surface, efficiently overcoming the chemical stability of these molecules.

It is also important to note that, while air plasma can theoretically lower solution pH by forming nitrogen species, preliminary analysis did not detect significant nitrite or nitrate formation in this study. Moreover, since Aldrin and Dieldrin are resistant to acid hydrolysis, the observed degradation is attributed to oxidative radical attack rather than pH-mediated effects.

The four non-thermal methods exhibited distinct operational profiles despite all achieving high degradation of the persistent organochlorine pesticides, Aldrin and Dieldrin. The main differences lie in their sensitivity to energy input and exposure time. Ultrasound stood out for its economic advantage, consistently delivering removal rates near 99% for both compounds at the lowest tested power and shortest times (3–5 min), with excess energy reducing overall efficiency. The electrical plasma techniques, especially corona discharge, achieved the highest efficiency (100% for Aldrin) but generally required long exposure times (15 min) to reach peak performance for both compounds. The dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma exhibited frequency-dependent performance, with optimal Dieldrin removal at the lowest frequency studied (50 Hz). Glow discharge plasma provided the most consistent stability, achieving high removal rates (>95%) across all flow rates and times tested, and demonstrating the least operational sensitivity to parameter variation among the four systems.

The comparison between the degradation profiles of Aldrin and Dieldrin across the four non-thermal techniques reveals some differences. Dieldrin contains an epoxide group in its structure, which renders it slightly more stable and less reactive than Aldrin. Aldrin demonstrated maximal degradation across the electrical plasma methods, achieving a 100% removal via corona discharge. In contrast, Dieldrin showed lower removal rates in the plasma systems (95.7% for the discharge barrier and 98.2% for corona discharge). However, its degradation subjected to ultrasound was slightly higher than that of Aldrin under equivalent operating conditions. Aldrin showed greater degradation in more aggressive plasma environments, such as those generated by DBD and corona plasmas, meeting the strict 0.03 μg/L regulatory limit more readily (Table 3). Dieldrin, while still highly degradable under ultrasound and plasma, was slightly more constrained by the operational conditions, suggesting that the epoxide ring may require prolonged exposure to the generated hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and other plasma reactive species for complete cleavage.

Table 3.

Final concentration of the pesticides Aldrin and Dieldrin in aqueous solution subjected to ultrasound and plasma treatments.

The required optimal treatment conditions vary significantly depending on the contamination level of Aldrin and Dieldrin relative to the regulatory limit (0.03 μg/L). For heavily contaminated waters, such as those with a concentration of 5 μg/L, which require a degradation of 99.4%, a more high-performing method is essential. For these heavily contaminated waters, corona discharge plasma at 15 kHz for 15 min, which delivered up to 99.98% removal of Aldrin, would be the most efficient method. For “normal” levels of Aldrin and Dieldrin contaminated waters (<0.1 μg/L), the required degradation to meet the 0.03 μg/L limit drops significantly to only 70%. In this scenario, the operational choice shifts to the more economically advantageous ultrasound technique, employing the mildest possible operating condition (3125 W/L ultrasonic power density for 3 min), as this condition already achieves 98% removal, surpassing the 70% target with minimal energy expenditure.

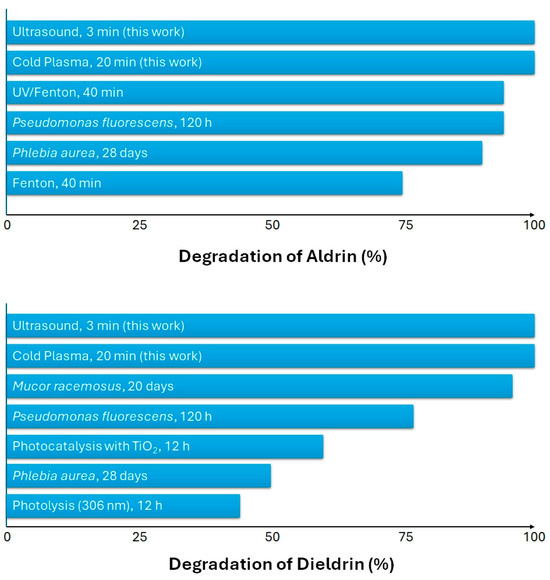

To contextualize the efficiencies achieved by non-thermal AOPs in this study, the degradation rates of Aldrin and Dieldrin were compared with those of various conventional, photocatalytic, and biological processes reported in the literature (Figure 4). This comparison highlights the advantages of highly reactive species generated by ultrasound and cold plasma.

Figure 4.

Comparison of efficiencies achieved by various conventional, photocatalytic, and biological processes for the degradation rates of Aldrin and Dieldrin [30,31,32,33,34].

The degradation of Aldrin demonstrated that the efficacy of the non-thermal methods studied herein is comparable to that of other processes in terms of total degradation rate. The optimal ultrasound condition tested in this work and the corona discharge plasma condition both achieved degradation efficiencies higher than 99%. In contrast, classical methods showed slightly inferior performance and required much longer treatment times. The Fenton and UV/Fenton processes, while oxidative, achieved satisfactory efficacy despite requiring a longer exposure time of 40 min. Biological treatments are effective against Aldrin, with Pseudomonas fluorescens reaching approximately 95% removal after 120 h (5 days) [30], and Phlebia aurea achieves about 90% removal after 28 days [33].

A similar, though less pronounced, trend was observed for the degradation of Dieldrin, reflecting its enhanced chemical stability due to the epoxide ring structure. The non-thermal techniques studied herein demonstrated high efficacy at optimal conditions, achieving degradations of 99% for ultrasound and 97% for corona discharge and glow discharge plasma. In comparison, the degradation of Dieldrin by photocatalysis with TiO2 reached about 60% removal after 12 h, while photolysis alone achieved approximately 44% removal over the same 12-h period [31,32]. Biological and microbial treatments showed to be efficient but slow, with Mucor racemosus and Pseudomonas fluorescens achieving satisfactory degradation rates (>77%), but requiring long treatment times (between 5 and 20 days) [34,35].

This comparison shows that the generation of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) by non-thermal methods leads to faster degradation kinetics than those observed in other chemical or biological systems. As such, non-thermal ultrasound and cold plasma processes represent a rapid and effective solution for treating water contaminated with persistent organochlorine pesticides like Aldrin and Dieldrin, outperforming some traditional chemical, photocatalytic, and biological remediation technologies.

3.1. Energy Efficiency Analysis

The economic viability of Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) is intrinsically linked to their energy consumption. Table 4 presents the electrical parameters (current, power, and total energy consumption) monitored for the ultrasound and plasma systems under varying operational conditions.

Table 4.

Electrical parameters monitored for the ultrasound and plasma systems under varying operational conditions.

The ultrasonic treatment exhibited a high energy demand, driven by the power density requirements to sustain acoustic cavitation. The power consumption ranged from 144.1 W to 266.0 W. Consequently, the total energy consumption for a 10-min treatment reached up to 0.047 kWh at the highest power density (6250 W/L). While effective, the high power input suggests that ultrasonic systems require optimization of the treatment volume-to-power ratio to become cost-competitive.

The DBD system demonstrated the highest energy efficiency among all tested configurations. Operating at very low power levels, ranging from 28.2 W (at 50 Hz) to 49.3 W (at 1000 Hz), the DBD reactor consumed between 0.002 kWh and 0.012 kWh. Increasing the excitation frequency from 50 to 500 Hz increased power from 28 W to 40 W, likely due to the higher voltage required to maintain discharge. Despite this, DBD was the most energy-efficient option, consuming approximately one-tenth the power required by the glow discharge system.

In contrast to the DBD, the glow discharge system was the most energy-intensive plasma technology evaluated. Power consumption peaked at 343.3 W at 10 mL/min, resulting in an energy consumption of 0.087 kWh after 15 min. An inverse relationship between frequency and power was observed: increasing the gas flow rate from 10 mL/min to 30 mL/min reduced power consumption from 343.3 W to 273.5 W. This behavior suggests a change in the discharge regime or in impedance-matching efficiency at higher flow rates. However, because its power demand is comparable to or exceeds that of the ultrasound system, glow discharge operation incurs the highest operational cost (OPEX).

The corona discharge system offered a balanced profile between energy input and oxidative performance. Power consumption ranged from 70.7 W (5000 Hz) to 84.7 W (15,000 Hz), with energy values falling between 0.006 and 0.021 kWh. Although it consumes roughly twice as much energy as the DBD system, it remains significantly more efficient than the glow-discharge and ultrasound setups.

Table 5 summarizes the energy efficiency (EE), expressed in kWh per microgram (mg) of pesticide removed, for the optimal conditions of each technology. A lower value indicates a more energy-efficient process.

Table 5.

Optimal energy efficiency (EE) to remove the pesticides Aldrin and Dieldrin in aqueous solution subjected to ultrasound and plasma treatments.

The DBD system proved to be the most energy-efficient technology among those evaluated. Operating at 50 Hz for 5 min, it required the lowest energy input to degrade the pollutants, with an EE of 0.016 kWh/mg for Aldrin and 0.017 kWh/mg for Dieldrin. This high efficiency is attributed to the system’s ability to maintain a stable discharge at very low power consumption (approx. 28 W) while maintaining high degradation rates.

Ultrasound (3125 W/L) ranked second in efficiency, with an EE of 0.028 kWh/µg for both pesticides. Although ultrasonic systems generally have high power requirements, the rapid degradation kinetics (3 min) compensated for the energy demand, making it a viable intermediate option.

The other two plasma configurations showed significantly higher energy costs per unit of pollutant removed. The corona discharge required approximately 3 times more energy than the DBD system, with values of 0.048–0.050 kWh/μg. While this system achieved complete degradation (100%), the higher power input (approx. 70–85 W) reduced its overall energy efficiency ratio compared to the DBD. The glow discharge (GD) was the least efficient of the methods evaluated. With an EE of 0.096 kWh/mg (Aldrin) and 0.099 kWh/mg (Dieldrin), it consumed nearly 6 times more energy than the DBD system to achieve comparable removal mass. This high cost suggests that, despite its effectiveness, glow discharge is less economically attractive for this specific application, mainly because it requires low operating pressures.

3.2. Degradation Mechanism

Following the degradation efficiency tests, a critical step in this kind of study is identifying potential by-products formed during the process. Samples collected after processing were subjected to GC-MS analysis in Full Scan mode, which operates by analyzing a broad range of mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) (specifically 40−500 m/z), a configuration designed to identify multiple and often unknown components in a sample.

The resulting chromatograms did not yield conclusive evidence of degradation intermediates or final products. While the disappearance of the characteristic pesticide peaks (peaks at TR 11.15 min for Aldrin and TR 13.28 min for Dieldrin) confirmed the high degree of conversion, no significant new peaks related to organic breakdown products were identified and matched against the NIST spectral library.

Prior studies on the degradation of Aldrin and Dieldrin have reported that Aldrin is transformed through oxidation, reduction, and hydroxylation pathways, with Dieldrin being the principal metabolite. At the same time, Dieldrin is further converted by oxidation, reduction, hydroxylation, and hydrolysis to give 9-hydroxydieldrin and dihydroxydieldrin. Ozone and photocatalytic systems degrade Aldrin via •OH and other strong oxidants. These studies have identified the intermediates in an ozonated visible-light photocatalytic system as 9-hydroxyaldrin, chlorinated cyclohexadiene intermediates, and small carboxylic acids (oxalic and fumaric), consistent with progressive dechlorination and ring-opening before mineralization [34,35].

The outcome observed in our study suggested two main possibilities. The first is that the plasma reactive species generated during the processes (such as the hydroxyl radical, superoxide anion, ozone, singlet oxygen, molecular hydrogen, and others) achieved complete mineralization of the pesticides, converting the initial organic molecules entirely into simple, stable inorganic species like water, carbon dioxide, and inorganic chlorides. The second possibility is the formation of degradation products that were either non-volatile and therefore captured by the SPME fiber and detected by GC-MS, or present in concentrations below the detection limits of the GC-MS system under the employed analytical conditions. Future investigations would require alternative analytical techniques, such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled with Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS), which is better suited to polar and less volatile compounds, to definitively rule out the formation of potentially toxic intermediates.

3.3. Scale-Up Considerations

It is important to note that while the probe-type ultrasound system demonstrated high efficiency in this bench-scale study, scaling up this technology presents engineering challenges related to cavitation uniformity. In larger batch volumes, the acoustic intensity attenuates rapidly from the probe tip. Consequently, industrial applications would likely require continuous-flow-through reactors or multi-transducer arrays to ensure a homogeneous cavitation field throughout the treated volume.

Similarly, the scale-up of plasma technologies must address the discharge’s surface-limited nature. Since the degradation mechanism relies on the diffusion of reactive species from the gas–liquid interface into the bulk, traditional deep-tank reactors are inefficient for large volumes. Future industrial applications would likely require reactor designs that maximize interfacial area, such as falling-film reactors or spray towers. These configurations generate thin liquid layers or droplets, significantly enhancing the contact area between the pollutant-laden water and the plasma discharge, thereby maintaining high degradation efficiency at larger scales.

The implementation of these technologies at pilot or full-scale industrial levels is envisioned primarily as a tertiary polishing step. Given the energy costs associated with AOPs, they are best suited for treating water and effluents that have already undergone primary and biological treatment, targeting only the residual recalcitrant loads (such as POPs). Feasibility at this scale relies on the adoption of continuous-mode reactors, previously commented on, such as multi-transducer ultrasonic flow cells or plasma falling-film units, which are already commercially available or in advanced development stages for other industrial applications.

While the precise optimal values identified are specific to the bench-scale geometry employed, the observed operational trends, specifically the high efficiency of moderate ultrasonic power and the trade-off between speed and absolute removal in plasma systems, provide generalizable design principles for the implementation of these technologies at larger scales.

Finally, it is crucial to contextualize the study’s achievements within its experimental scope. Analytically, GC-MS analysis successfully confirmed the rapid elimination of the toxic parent compounds and the absence of stable organic intermediates; however, the lack of complementary analysis means that a complete mass balance to prove complete mineralization remains to be verified. Environmentally, the use of distilled water provided a necessary baseline for determining intrinsic degradation kinetics without interference; however, future applications must account for the radical scavenging effects typical of complex wastewater matrices. Operationally, while the batch reactors demonstrated high removal efficiencies (>99%), industrial implementation will require transitioning to continuous-flow configurations to address mass-transfer limitations. In this work, a proof-of-concept was established, paving the way for scale-up studies. Energetically, the study found that while plasma technologies offer superior absolute removal, their higher energy costs position them best as tertiary polishing steps for the final elimination of recalcitrant micropollutants.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that ultrasound and three plasma technologies (glow discharge, corona discharge, and dielectric barrier discharge) achieved high removal rates of the persistent organochlorine pollutants Aldrin and Dieldrin. Aldrin, despite its classification as a Persistent Organic Pollutant (POP), was the most readily degraded compound, achieving residual concentrations below the maximum permissible drinking water limit (0.03 μg/L) across various plasma conditions.

Ultrasound emerged as the most effective option, achieving removal efficiencies exceeding 98% for both pesticides under the mildest operational conditions (a 3125 W/L ultrasonic power density for 3 min). This performance is ideal for efficiently treating contaminated water while minimizing energy consumption. In contrast, corona discharge plasma achieved the highest performance, completely degrading Aldrin, making it best suited for treating heavily contaminated water; however, it required prolonged exposure times (15 min) to achieve maximum efficiency. The dielectric barrier discharge plasma was shown to be the most cost-effective system, given the lowest energy consumption among all tested technologies.

Although the degradation rate was high, GC-MS analysis could not conclusively identify any breakdown byproducts. This result suggested that these advanced oxidation processes likely promoted extensive degradation of Aldrin and Dieldrin, effectively eliminating the parent compounds without accumulating detectable organic byproducts. However, definitive confirmation of complete mineralization, accounting for potentially volatile inorganic and organic breakdown products, requires further investigation involving ion analysis and toxicity assays. Future investigations using highly sensitive analytical techniques, such as HPLC-MS/MS, or toxicological tests with model organisms, such as zebrafish, are still recommended to confirm the complete toxicological safety of the treated water.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A.N.F.; methodology, M.S.d.A. and F.A.N.F.; formal analysis, M.S.d.A.; investigation, M.S.d.A.; resources, F.A.N.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.d.A.; writing—review and editing, F.A.N.F.; supervision, F.A.N.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), grant number Code 001.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Núcleo de Tecnologia e Qualidade Industrial do Ceará (NUTEC) for the use of the GC-MS.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Monticelli Barizon, R.R.; Kummrow, F.; Fernandes de Albuquerque, A.; Assalin, M.R.; Rosa, M.A.; Cassoli de Souza Dutra, D.R.; Almeida Pazianotto, R.A. Surface Water Contamination from Pesticide Mixtures and Risks to Aquatic Life in a High-Input Agricultural Region of Brazil. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panis, C.; Candiotto, L.Z.P.; Gaboardi, S.C.; Gurzenda, S.; Cruz, J.; Castro, M.; Lemos, B. Widespread Pesticide Contamination of Drinking Water and Impact on Cancer Risk in Brazil. Environ. Int. 2022, 165, 107321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najam, L.; Alam, T. Occurrence, Distribution, and Fate of Emerging Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in the Environment. In Emerging Contaminants and Plants. Emerging Contaminants and Associated Treatment Technologies; Aftab, T., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 135–161. [Google Scholar]

- Nehul, J.N. Environmental Impact of Pesticides: Toxicity, Bioaccumulation and Alternatives. Environ. Rep. 2025, 7, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, J.A.; Araújo, R.G.; López-Pacheco, I.Y.; Rodas-Zuluaga, L.I.; González-González, R.B.; Parra-Arroyo, L.; Sosa-Hernández, J.E.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Martínez-Ruiz, M.; Barceló, D.; et al. Environmental Persistence, Detection, and Mitigation of Endocrine Disrupting Contaminants in Wastewater Treatment Plants–A Review with a Focus on Tertiary Treatment Technologies. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2022, 1, 680–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Pesticides Use and Trade, 1990–2022; Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- de Andrade, F.V.; Augusti, R.; de Lima, G.M. Ultrasound for the Remediation of Contaminated Waters with Persistent Organic Pollutants: A Short Review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 78, 105719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, I.A.; Zouari, N.; Al-Ghouti, M.A. Removal of Pesticides from Water and Wastewater: Chemical, Physical and Biological Treatment Approaches. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 19, 101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, R.; Dhakal, O.B.; Mukherjee, S.; Acharya, T.R.; Lamichhane, P.; Kaushik, N.; Kaushik, N.K.; Choi, E.H. Sustainable Removal of Sulfathiazole from Aqueous Solutions Using ZnFe2O4-Catalyzed Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma: Efficiency, Reusability, and Environmental Impact. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 523, 168588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, D.; Qiu, R.; Tang, Y.; Du, C. Non-Thermal Plasma Technology for Organic Contaminated Soil Remediation: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 313, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsalu, K.; Rana, J.N.; Kifle, R.; Lim, J.S.; Acharya, T.R.; Kim, C.T.; Choi, E.H. Dibutyl Phthalate Degradation and Toxicity Assessment Based on Hydroxyl Radicals Generated by Plasma Jet. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 502, 157895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavahian, M.; Sarangapani, C.; Misra, N.N. Cold Plasma for Mitigating Agrochemical and Pesticide Residue in Food and Water: Similarities with Ozone and Ultraviolet Technologies. Food Res. Int. 2021, 141, 110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Boussetta, N.; Enderlin, G.; Grimi, N.; Merlier, F. Real-Time Monitoring of the Atrazine Degradation by Liquid Chromatography and High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry: Effect of Fenton Process and Ultrasound Treatment. Molecules 2022, 27, 9021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Tyagi, I.; Gupta, V.K.; Dehghani, M.H.; Bagheri, A.; Yetilmezsoy, K.; Amrane, A.; Heibati, B.; Rodriguez-Couto, S. Degradation of Azinphos-Methyl and Chlorpyrifos from Aqueous Solutions by Ultrasound Treatment. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 221, 1237–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, A.; Yu, H.; Tan, L.; Yang, L. Enhanced Degradation of Lindane in Water by Sulfite-Assisted Ultrasonic (SF/US) Process: The Critical Role of Generated Aqueous Electrons. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2025, 119, 107411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarangapani, C.; Misra, N.N.; Milosavljevic, V.; Bourke, P.; O’Regan, F.; Cullen, P.J. Pesticide Degradation in Water Using Atmospheric Air Cold Plasma. J. Water Process Eng. 2016, 9, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalexopoulou, K.; Panagopoulou, E.I.; Bastani, A.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Aggelopoulos, C.A. Comparative Study of DBD Plasma Bubbles and Corona Discharge Bubbles for Atrazine Degradation in Water: From Process Optimization to Degradation Pathways. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2026, 380, 135349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Júnior, F.E.; Fernandes, F.A.N. Degradation of Diazinon by Dielectric Barrier Discharge Plasma. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraj, R.; Megha, P.; Sreedev, P. Review Article. Organochlorine Pesticides, Their Toxic Effects on Living Organisms and Their Fate in the Environment. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2016, 9, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onsager, J.A.; Rusk, H.W.; Butler, L.I. Residues of Aldrin, Dieldrin, Chlordane, and DDT in Soil and Sugarbeets. J. Econ. Entomol. 1970, 63, 1143–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, M.W.; Petterson, D.S. Absorption by Sheep of Dieldrin from Contaminated Soil. Aust. Vet. J. 1997, 75, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, K.; Ridal, J.; Struger, J. Pesticides in the Great Lakes. In Persistent Organic Pollutants in the Great Lakes; Hites, R.A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005; pp. 151–199. [Google Scholar]

- Etchegoyen, M.; Ronco, A.; Almada, P.; Abelando, M.; Marino, D. Occurrence and Fate of Pesticides in the Argentine Stretch of the Paraguay-Paraná Basin. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J.; van Dijk, R.; Abalos, M.; Abad, E. Persistent Organic Pollutants in Air from Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Pacific. Chemosphere 2023, 324, 138271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministério da Saúde Sisagua. 2025. Available online: http://sisagua.saude.gov.br/sisagua/paginaExerna.jsf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Lankone, R.S.; Deline, A.R.; Barclay, M.; Fairbrother, D.H. UV–Vis Quantification of Hydroxyl Radical Concentration and Dose Using Principal Component Analysis. Talanta 2020, 218, 121148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovenston, T.C.J.; Rees, W.T. The Spectrophotometric Determination of Small Amounts of Hydrogen Peroxide in Aqueous Solutions. Analyst 1950, 75, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnani, L.; Gaydou, E.M.; Hubaud, J.C. Spectrophotometric Measurement of Antioxidant Properties of Flavones and Flavonols against Superoxide Anion. Anal. Chim. Acta 2000, 411, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, F.A.N.; Maia, D.L.H.; Canuto, K.M.; de Brito, E.S. Aroma Modulation of Limonene-Rich Essential Oil Using Cold Plasma Technology. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 2025, 45, 1925–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandala, E.; Andres-Octaviano, J.; Pastrana, P.; Torres, L. Removal of Aldrin, Dieldrin, Heptachlor, and Heptachlor Epoxide Using Activated Carbon and/or Pseudomonas Fluorescens Free Cell Cultures. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2006, 41, 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Saeid, M.H.; Alotaibi, M.O.; Alshabanat, M.; Alharbi, K.; Altowyan, A.S.; Al-Anazy, M. Photo-Catalytic Remediation of Pesticides in Wastewater Using UV/TiO2. Water 2021, 13, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusvuran, E. Degradation of Aldrin in Adsorbed System Using Advanced Oxidation Processes: Comparison of the Treatment Methods. J. Hazard. Mater. 2004, 106, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Chen, F.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Hu, X. The Degradation of Chlorpyrifos and Diazinon in Aqueous Solution by Ultrasonic Irradiation: Effect of Parameters and Degradation Pathway. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 1109–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, A.S. Microbe-Assisted Degradation of Aldrin and Dieldrin. In Microbe-Induced Degradation of Pesticides. Environmental Science and Engineering; Singh, S., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, S.; Lin, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Mishra, S.; Bhatt, P.; Chen, S. Microbial Degradation of Aldrin and Dieldrin: Mechanisms and Biochemical Pathways. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 713375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).