Abstract

Hydrogel-based solar-driven interfacial evaporators have recently emerged as high-efficiency and sustainable technology for desalination. By leveraging the unique three-dimensional network, remarkable hydrophilicity, and tunable physicochemical properties of hydrogels, these systems achieve efficient solar absorption and thermal conversion, significantly enhancing water evaporation rates. This review summarizes design strategies based on physical and chemical cross-linking, and explores key approaches for performance enhancement, including reduction of evaporation enthalpy and structural optimization. Through regulation of water states and construction of multi-scale porous and biomimetic architectures, synergistic improvements in photothermal conversion, water transport, and thermal management have been realized. Furthermore, hydrogel-based evaporators demonstrate great potential in integrated applications such as wastewater treatment, salt collection, and hydroelectric generation. Finally, challenges related to water purification applications are discussed. This review offers valuable insights for the future design of hydrogel-based solar evaporators to mitigate global water scarcity.

1. Introduction

Fresh water plays an essential role in sustaining basic life activities. However, with global population growth and industrial development, freshwater scarcity has become an increasingly severe issue [1,2,3,4]. It is projected that by 2030, about one-third of the world’s population will face serious freshwater shortages [5], a figure expected to rise further by 2050. The scarcity of freshwater resources will severely constrain socio-economic development and constitutes a pressing societal challenge in the contemporary era. To resolve this challenge, researchers have developed various desalination technologies such as electrodialysis [6], multi-stage flash distillation [7], reverse osmosis [8], and distillation [9]. However, these methods generally require relatively complex equipment and high maintenance costs in practical applications, inevitably increasing their limitations and implementation complexity. Furthermore, these technologies also suffer from issues such as high energy consumption and significant pollution [10], which have not yet been effectively resolved. As a low-cost and sustainable clean energy source, solar energy is inexhaustible and has attracted widespread attention from researchers, enabling a new approach to seawater desalination [11,12,13].

Solar-driven desalination technology utilizes photothermal materials to convert solar energy into thermal energy, typically operating in three fundamental modes: bottom heating, volumetric heating, and interfacial heating [14]. Both bottom and volumetric heating modes suffer from significant heat loss and low energy conversion efficiency. In recent years, researchers have developed techniques to localize photothermal conversion at the evaporator surface. Unlike the former two modes, interfacial heating confines thermal energy precisely at the air–water interface, thereby minimizing heat dissipation and improving energy utilization efficiency. As a result, solar-driven interfacial evaporation has been widely recognized as a promising solution to address freshwater scarcity [15,16,17].

The core structure of a standard solar interfacial evaporation system comprises two essential components: a photothermal conversion layer and a substrate [18,19]. The exploration of photothermal materials and the structural design of the substrate are crucial for optimizing system performance. The photothermal layer absorbs solar radiation and transforms it into heat. This generated heat then warms the interfacial water film, enabling evaporation [20,21,22]. An ideal photothermal material should exhibit high light absorption, low evaporation enthalpy, and low thermal conductivity. Photothermal materials commonly used can be classified into polymers [23,24], semiconductors [25,26], carbon-based materials [27,28], and plasmonic materials [29,30]. The photothermal conversion mechanisms of these materials mainly include three types: localized plasmonic heating in metallic nanomaterials, generation and non-radiative relaxation of electron–hole pairs in semiconductors, and molecular thermal vibration in carbon-based materials [31,32,33]. The intrinsic structure and photothermal properties of these materials are fundamental to solar absorption and conversion. The substrate must provide strong water transport capability from the bulk solution to the evaporation interface [34,35]. Therefore, porous materials with good wettability and abundant pores are often selected as substrates. To minimize the dissipation of heat generated at the evaporation interface into the underlying water, the substrate should also possess low thermal conductivity. Furthermore, the long-term operational stability of solar interfacial evaporation systems depends critically on their salt resistance and mechanical strength.

Hydrogels, characterized by their unique three-dimensional network structures, have recently emerged as a research hotspot in the field of solar interfacial evaporation. Hydrogel-based materials demonstrate exceptional performance in water absorption and transport during evaporation, attributable to their inherent hydrophilicity, porous architecture, and large specific surface area [36]. These properties originate from the abundant hydrophilic functional groups (such as -OH, -COOH, and -NH2) within their polymer networks. Moreover, the highly tunable physicochemical properties of hydrogels enable rational structural design, allowing hydrogel-based solar evaporators to achieve high water evaporation rates, energy conversion efficiency, as well as excellent salt resistance and mechanical strength. These attributes collectively ensure continuous and stable water supply to the evaporation interface, facilitating rapid and efficient vapor generation [37].

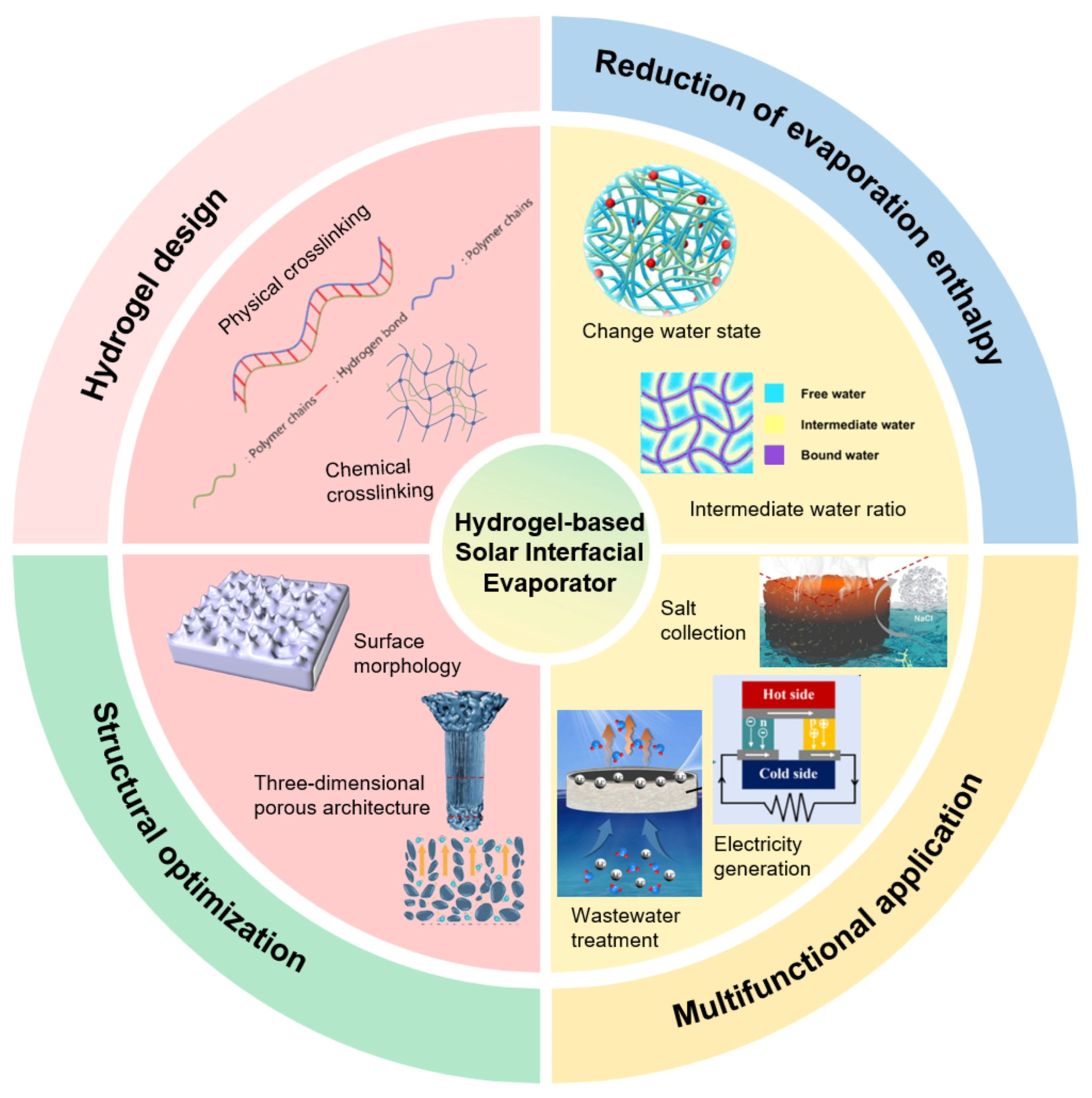

This review summarizes recent research advances in hydrogel-based solar interfacial evaporators (Figure 1), focusing on their design principles and fabrication methods. Key strategies for enhancing water evaporation rates are discussed, including reducing evaporation enthalpy, optimizing photothermal materials, minimizing heat loss, designing three-dimensional porous structures, and improving salt resistance. Regarding practical applications, emerging multifunctional uses of hydrogel-based evaporators are highlighted, such as wastewater treatment, atmospheric water harvesting, and concurrent water-electricity generation. Finally, future research directions and existing challenges are outlined. This review aims to provide both theoretical and practical guidance for the design, performance enhancement, and application expansion of hydrogel-based solar interfacial evaporators.

Figure 1.

Hydrogel-Based Solar Interfacial Evaporators.

2. Hydrogel Design

As an indispensable substrate material in solar interfacial evaporation [38], hydrogels are engineered to enhance fundamental properties such as mechanical strength, thermal insulation, and water absorption capacity. A hydrogel is a three-dimensional polymer network formed by crosslinking hydrophilic polymer chains in an aqueous medium, with crosslinking mechanisms generally categorized into physical and chemical crosslinking [39,40]. Physically crosslinked hydrogels are formed via non-covalent interactions—such as hydrogen bonds [41], ionic bonds [42], van der Waals forces, π–π stacking [43], and hydrophobic interactions—that connect polymer chains. Common examples include gelatin, agar, and calcium alginate. In contrast, chemically crosslinked hydrogels are formed through covalent bonds between polymer chains resulting from chemical reactions in solution, such as free radical polymerization [44], condensation reactions, and aldehyde-mediated crosslinking. Typical chemically crosslinked hydrogels include polyacrylamide (PAAM) and polyacrylic acid (PAA). The microstructure of hydrogels can be controlled through the rational adjustment of parameters in their physical or chemical crosslinking processes. This control offers a pathway to designing materials with enhanced comprehensive properties, including mechanical behavior and dissolution performance.

2.1. Physically Crosslinked Hydrogels

The structural integrity of physically crosslinked hydrogels stems from non-covalent interactions, for example, hydrogen bonding, ionic bonding, and hydrophobic association. A key limitation of chemically crosslinked hydrogels is the retention of crosslinking agents within the hydrogel matrix during the crosslinking process, which can adversely affect their structure and functionality. In contrast, physical crosslinking offers a simpler and milder alternative that avoids the need for chemical crosslinkers, thereby circumventing this issue. Furthermore, non-covalent interactions also enhance the mechanical integrity of the hydrogels to some degree.

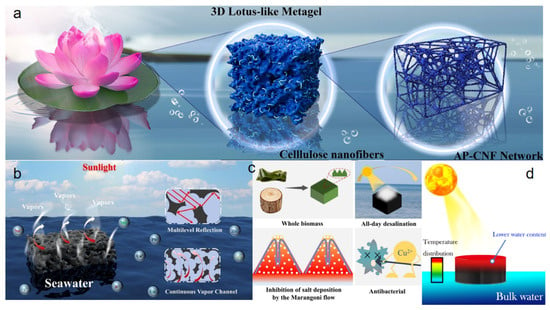

Hydrogen bonding serves as one of the key intermolecular interactions for constructing and stabilizing hydrogel structures. Hydrogen bonding is primarily due to the attraction between highly electronegative atoms and hydrogen atoms. In hydrogels, functional groups including hydroxyl, carboxyl and phenolic hydroxyl groups are prevalent and readily form hydrogen bonds [45], which contributes significantly to the structural stability of the hydrogels. For instance, Wang et al. [46] developed a three-dimensional lotus-shaped interfacial evaporator (3DL Metagel) based on cellulose nanofibers (CNF) (Figure 2a). By introducing Al(H2PO4)3 (AP) as a hydrophilic inorganic binder rich in hydroxyl groups, an inorganic–organic hydrogen-bonded crosslinking network was formed between AP and CNF via hydrogen bonding. This design integrated multiple biomimetic strategies such as the lotus shape, Janus wettability, and plant transpiration, enabling highly efficient solar-driven water evaporation. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations revealed a binding energy of −358.6 kcal mol−1 between AP and CNF—11 times stronger than that between two CNF molecules—thereby markedly enhancing the structural stability of the hydrogel. Benefiting from this synergistic hydrogen-bonded network, the 3DL Metagel achieved an ultrahigh evaporation rate of 3.61 kg m−2 h−1 and a maximum evaporation efficiency of 94.94% under one-sun illumination. This inorganic–organic hydrogen-bonded network facilitates efficient photothermal evaporation and offers new insights for the rational design of high-performance solar desalination evaporators. In another study, She et al. [47] constructed a MXene/gelatin foam hydrogel (MGFH) using a combined strategy of high-speed stirring and freeze–thaw crosslinking (Figure 2b). In this system, abundant amino, carboxyl, and hydroxyl groups on gelatin molecular chains formed an extensive hydrogen-bonding network with hydroxyl groups from PVA and surface functional groups (-OH, -F) of Mxe-ne nanosheets. These multi-component hydrogen bonds significantly improved the mechanical stability of the hydrogel, enabling a maximum compressive strain exceeding 60% and a compressive stress of 1770 kPa. This robust mechanical performance ensures the material’s durability under repeated compression and enhances its resistance to wave disturbances during long-term seawater desalination. The MGFH attained a high evaporation rate of 2.26 kg m−2 h−1 under one-sun irradiation, underscoring the crucial role of hydrogen bonding in optimizing the performance of hydrogel-based evaporators.

Ionic bonds refer to electrostatic interactions between oppositely charged species. In hydrogels, ionic interactions form reversible physical crosslinks, typically occurring when negatively charged polymers are coordinated with cations in solution to construct a three-dimensional network. Li et al. [48] developed a fully bio-based porous hydrogel evaporator with a core–shell structure using sodium alginate (SA) as the matrix and pulp fibers (PF) as the reinforcement (Figure 2c). The coordination between Cu2+ ions and carboxyl groups on SA chains not only endowed the evaporator with excellent mechanical properties and water transport capability but also imparted remarkable antibacterial activity, achieving a 99.99% antibacterial rate against both E. coli and S. aureus. The evaporator also exhibited good salt tolerance, maintaining an evaporation rate of 2.42 kg m−2 h−1 even in 15 wt% saline. This study demonstrates the potential of ionically crosslinked hydrogels for constructing efficient, salt-resistant, and antibacterial solar interfacial evaporators, offering a practical and environmentally responsible solution to global water scarcity. However, several limitations remain. Under high-temperature conditions, the ion shielding effect can weaken the coordination between Cu2+ and carboxyl groups of SA, leading to partial dissociation of the crosslinked structure and potential delamination of the photothermal layer, thereby compromising long-term stability. Furthermore, the durability of the hydrogel under extreme environments and the feasibility of large-scale fabrication have not been fully validated. Future efforts should focus on optimizing the crosslinking stability and structural design to enhance its applicability in complex real-world scenarios.

Hydrophobic crosslinking comprehensively enhances the viscosity, salt tolerance, and long-term stability of the crosslinked network by increasing the effective molecular weight of the polymer and strengthening hydrophobic interactions [49]. Zhang et al. [50] introduced the hydrophobic association mechanism into the construction of a solar interfacial evaporator (Figure 2d). Their prepared evaporator (CAH) consists of a polyacrylamide hydrophilic framework crosslinked via hydrophobic associative microdomains, with carboxylated multi-walled carbon nanotubes incorporated as the solar absorber. The self-healing capability endowed by hydrophobic association allows the hydrogel evaporator to exhibit not only good mechanical strength and autonomous repair performance but also intelligent regulation of water content at the evaporation interface. Under one-sun illumination, the evaporator achieved an evaporation rate of 4.3 kg m−2 h−1. By rationally designing a bilayer structure, the evaporation rate was further increased to 5.1 kg m−2 h−1. The introduction of hydrophobic association not only reduces heat loss caused by excessive water on the evaporation surface but also offers a straightforward strategy for fabricating bilayer hydrogel solar evaporators. However, certain limitations remain. Although the incorporation of hydrophobic monomers enables regulation of water content, it also leads to a reduction in both the saturated water absorption capacity and water transport rate as the carbon nanotube content increases, thereby limiting its applicability in extremely high-salinity or low-humidity environments. Future work should focus on optimizing the hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance to enhance the material’s adaptability and reusability in complex aqueous environments.

Figure 2.

(a) Lotus-shaped 3DL Metagel. Reproduced with permission [46], (b) MXene/gelatin foam hydrogel (MGFH). Reproduced with permission [47], (c) SA/Cu2+ crosslinked porous hydrogel. Reproduced with permission [48], (d) CAH-based solar evaporator. Reproduced with permission [50].

Figure 2.

(a) Lotus-shaped 3DL Metagel. Reproduced with permission [46], (b) MXene/gelatin foam hydrogel (MGFH). Reproduced with permission [47], (c) SA/Cu2+ crosslinked porous hydrogel. Reproduced with permission [48], (d) CAH-based solar evaporator. Reproduced with permission [50].

2.2. Chemically Crosslinked Hydrogels

Chemically crosslinked hydrogels form permanent three-dimensional polymer networks through covalent bonds, characterized by stable and irreversible crosslinking sites. These hydrogels typically exhibit outstanding structural stability, high mechanical strength, and excellent anti-swelling properties, enabling them to maintain structural integrity over extended periods in aqueous environments—an essential attribute for long-term and high-intensity solar interfacial evaporation applications. Among various chemical crosslinking strategies, free radical polymerization and condensation reactions are the most commonly employed and efficient approaches for constructing the backbone of hydrogel evaporators. Compared to physically crosslinked hydrogels, chemical crosslinking imparts longer service life and more controllable network structures, which are critical for evaporators operating under conditions involving prolonged use, water flow impact, or mechanical stress. However, these advantages come with inherent limitations. The irreversible nature of covalent networks generally results in a lack of self-healing capability, meaning that structural damage is typically irreparable. Moreover, the synthesis process often involves chemical crosslinkers or initiators, which may raise biocompatibility concerns, while the inherent rigidity of the network could also restrict the rapid transport dynamics of water molecules.

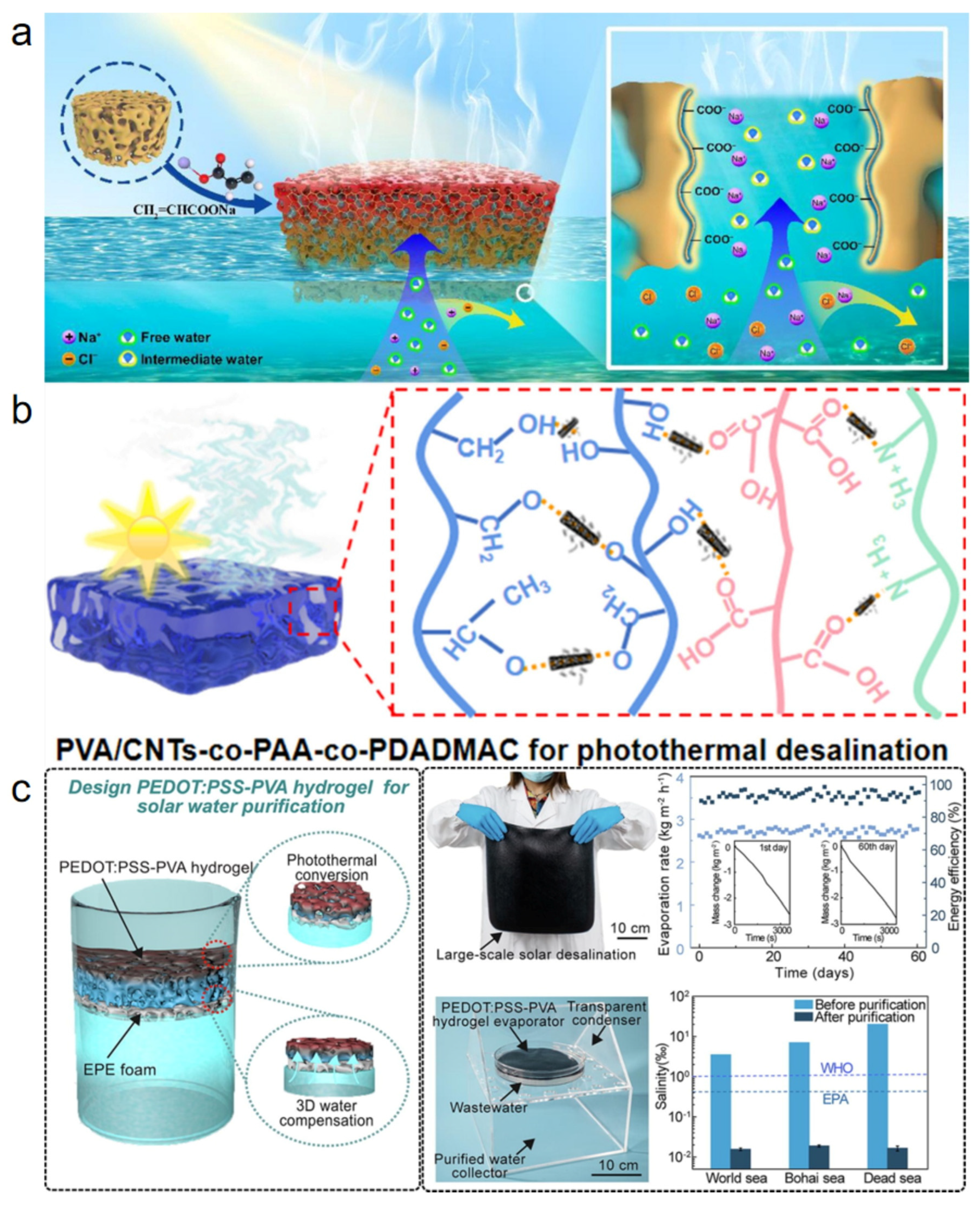

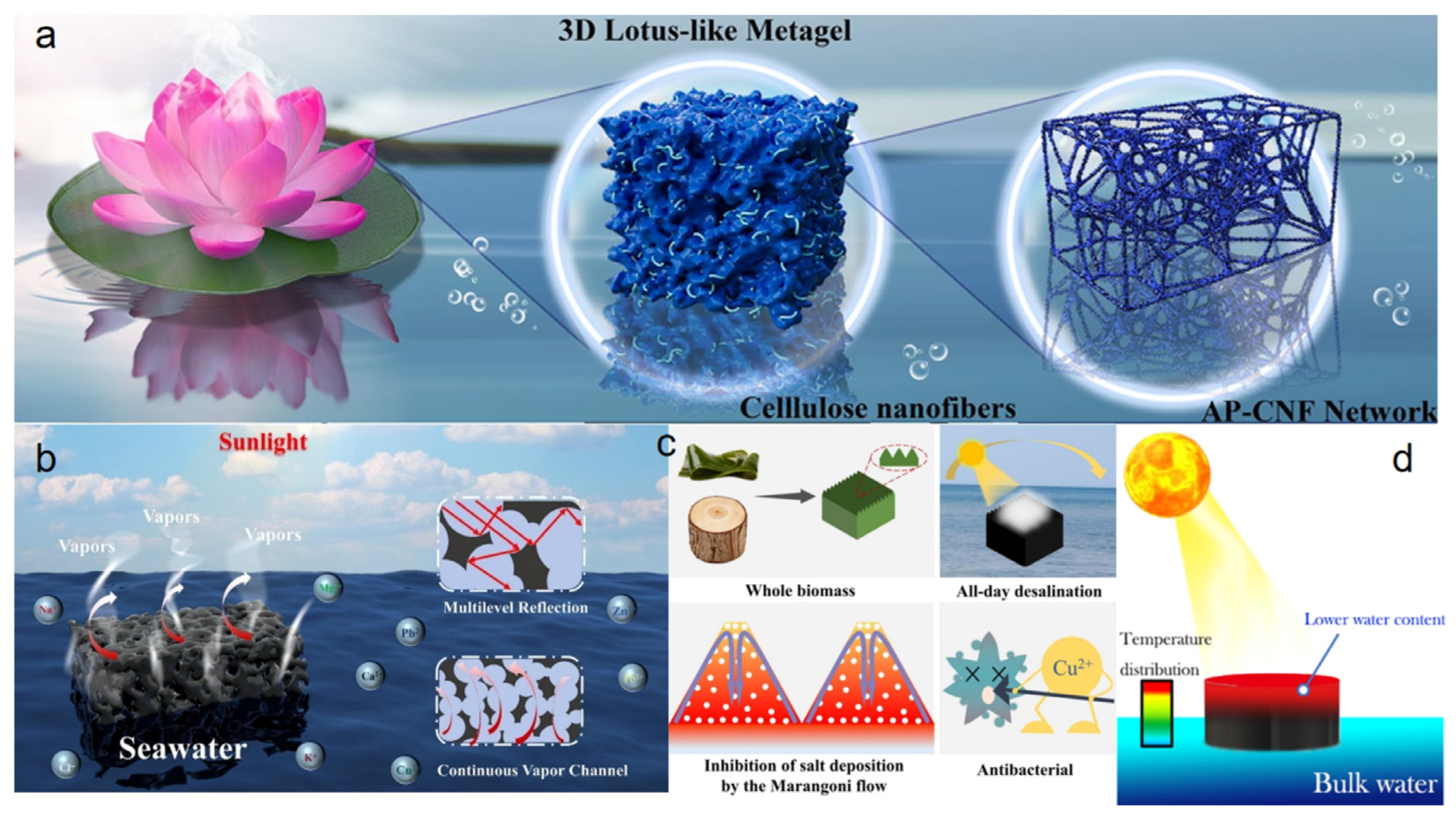

The efficacy of free radical polymerization in synthesizing chemically cross-linked hydrogels stems from the high reactivity of radical species, which facilitates the rapid gelation of unsaturated monomers or polymers in aqueous solution. This process efficiently incorporates synthetic, semi-synthetic, and natural precursors into a stable cross-linked network. Zhao et al. [51] successfully fabricated a spongy polyelectrolyte composite hydrogel with an interpenetrating network topology through an ingenious in situ free radical polymerization strategy (Figure 3a). In this approach, a porous sponge hydrogel (MP) with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) as the framework and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) as the photothermal material was first constructed via a foaming technique. The MP skeleton was then impregnated with a sodium acrylate (SA) monomer solution, in which free radical polymerization was triggered in situ to generate a poly (sodium acrylate) (P(SA)) network, ultimately forming a robust PVA/P(SA) interpenetrating network. This composite strategy based on free radical polymerization not only endowed the hydrogel with high mechanical strength and excellent compressive resilience—withstanding 100 compression cycles at 50% strain—but also imparted efficient water transport and photothermal conversion capabilities, achieving a light absorption rate of 92.88%. Under one-sun illumination, the MPS hydrogel attained a high evaporation rate of 3.22 kg m−2 h−1 and an energy conversion efficiency of 92.95%. Furthermore, the abundant fixed negative charges generated by the ionization of the P(SA) network effectively inhibited the enrichment of salt ions at the evaporation interface, enabling the hydrogel to maintain a stable evaporation rate of 2.8 kg m−2 h−1 even in 20 wt% high-salinity brine. This study provides a valuable design pathway for constructing high-performance, salt-tolerant, and robust solar interfacial evaporators via free radical polymerization. Guo et al. [52] developed a PVA/CNTs-co-PAA-co-PDADMAC (PADM) polyelectrolyte hydrogel (Figure 3b). Using acrylic acid (AA) as the monomer and ammonium persulfate (APS) as the initiator, free radical polymerization was carried out in the presence of the polycationic electrolyte PDADMAC and photothermal carbon nanotubes (CNTs), while glutaraldehyde (GA) was simultaneously used to crosslink the PVA chains. This process resulted in a hydrogel with controllable crosslinking density and an interconnected porous structure. The obtained hydrogel exhibited high porosity and favorable mechanical properties, significantly enhancing water transport rate, light absorption capacity, and salt reflux efficiency. In terms of solar evaporation performance, the PADM hydrogel achieved a high evaporation rate of 3.58 kg m−2 h−1, which remained at 3.18 kg m−2 h−1 even in 20 wt% brine. Additionally, the evaporation enthalpy was reduced to 932.209 J g−1, significantly lower than that of pure water, which is attributed to the activation of water molecules through hydrogen bonding within the polyelectrolyte network. Although this system demonstrated promising stability under laboratory conditions, its long-term durability in real outdoor environments has not been fully verified. Moreover, a comprehensive assessment of its environmental impact is lacking, which may hinder its practical application and scalability.

Figure 3.

(a) MPS evaporator with interpenetrating network. Reproduced with permission [51], (b) PADM polyelectrolyte hydrogel evaporator. Reproduced with permission [52], (c) Microphase-separated PEDOT:PSS-PVA composite hydrogel evaporator. Reproduced with permission [53].

Condensation reactions involve the formation of polymeric macromolecules through the elimination of small molecules between functional groups. The presence of exposed active functional groups on polymer chains enables the formation of three-dimensional hydrogel networks via esterification or amidation reactions. Zhao et al. [53] successfully prepared a PEDOT:PSS–PVA composite hydrogel with a microphase-separated structure through the acetal reaction between glutaraldehyde (GA) and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) (Figure 3c). In this work, PEDOT:PSS nanofibers were first physically blended with a PVA solution, followed by the introduction of the crosslinker GA. Under acidic catalysis, GA underwent a condensation reaction with the hydroxyl groups on PVA chains, forming a stable covalent network, while freeze–thaw cycling was applied to enhance physical crosslinking. This dual-crosslinking strategy—combining chemical and physical interactions—endowed the hydrogel with excellent mechanical robustness, enabling it to withstand 500 compression cycles at 50% strain with stable performance in both compressive and tensile tests. The as-fabricated hydrogel exhibited a broad-spectrum light absorption of 99.7%. Under one-sun irradiation, it achieved an evaporation rate of 2.84 kg m−2 h−1 and a remarkable energy efficiency of 98.0%. Moreover, the hydrogel maintained stable operation over 60 days in simulated seawater, with an average efficiency remaining as high as 93.3%. The study further demonstrated its potential for large-scale seawater desalination and dye wastewater treatment, with the produced water meeting the World Health Organization (WHO) drinking water standards. Nevertheless, the relatively high cost of PEDOT:PSS may limit its practical application in resource-limited regions.

The selection between physical and chemical crosslinking is fundamentally governed by their distinct thermodynamic properties, which directly dictate the hydrogel’s water retention behavior and operational durability. Physically crosslinked networks, stabilized by dynamic and reversible non-covalent bonds, possess lower bond energies. This inherent reversibility facilitates self-healing and promotes the formation of more intermediate water, which is beneficial for reducing evaporation enthalpy. However, these networks can be susceptible to gradual dissociation under sustained mechanical stress or extreme chemical environments, potentially compromising long-term stability. In contrast, chemically crosslinked networks, formed by robust and permanent covalent bonds with significantly higher bond energies, provide exceptional structural integrity and resistance to dissolution, ensuring remarkable durability. The trade-off for this enhanced stability is often a more rigid polymer network that constrains water molecules, potentially increasing the proportion of bound water and evaporation enthalpy. Thus, the choice represents a strategic balance between dynamic adaptability and permanent robustness, influencing both the water state management for evaporation performance and the structural resilience for long-term application.

3. Strategies for Enhancing Evaporation Rate

The solar water evaporation rate is a key metric for evaluating the amount of water evaporated per unit area and time under solar-driven conditions. It is influenced by factors such as solar irradiance, ambient conditions, and the material structure of the evaporator. Significant improvements can be achieved by reducing the evaporation enthalpy and optimizing structural design. The evaporation rate is defined as the change in water mass per unit illumination time and unit evaporation area, calculated as follows:

where represents the change in water mass, is the evaporation area, and is the actual illumination time. The unit of evaporation rate is kg m−2 h−1.

Calculation and analysis of the solar water evaporation rate provide critical theoretical insights for optimizing the design and performance of solar interfacial evaporation systems. Therefore, enhancing the solar water evaporation rate remains one of the central challenges in the development of solar interfacial evaporation technologies.

3.1. Reduction of Evaporation Enthalpy

The evaporation enthalpy, defined as the thermal energy required for the liquid-to-vapor phase transition under constant temperature and pressure [54,55], is a key parameter governing the performance of hydrogel-based solar evaporators. Given this definition, lowering the evaporation enthalpy presents an effective strategy to improve the evaporation rate, which can be quantified using the following equation [56]:

where typically represents the evaporation enthalpy of bulk water, denotes the equivalent evaporation enthalpy of water in the hydrogel, is the mass change of bulk water, and is the mass change of the hydrogel.

Hydrophilic functional groups on polymer chains interact with water molecules via non-covalent interactions such as hydrogen bonding, leading to three distinct states of water within the hydrogel: free water (FW), intermediate water (IW), and bound water (BW). Free water exhibits negligible interaction with the polymer backbone and retains properties similar to those of bulk water. In contrast, bound water is strongly associated with the polymer chains, making it difficult to evaporate and resulting in a high evaporation enthalpy. Intermediate water, formed through weak hydrogen bonding between bound and free water, interacts moderately with hydrophilic groups. Due to its lower interaction energy, intermediate water evaporates more readily, requiring less energy. Therefore, increasing the proportion of intermediate water in the hydrogel system can effectively reduce the evaporation enthalpy [57], thereby improving the evaporation rate.

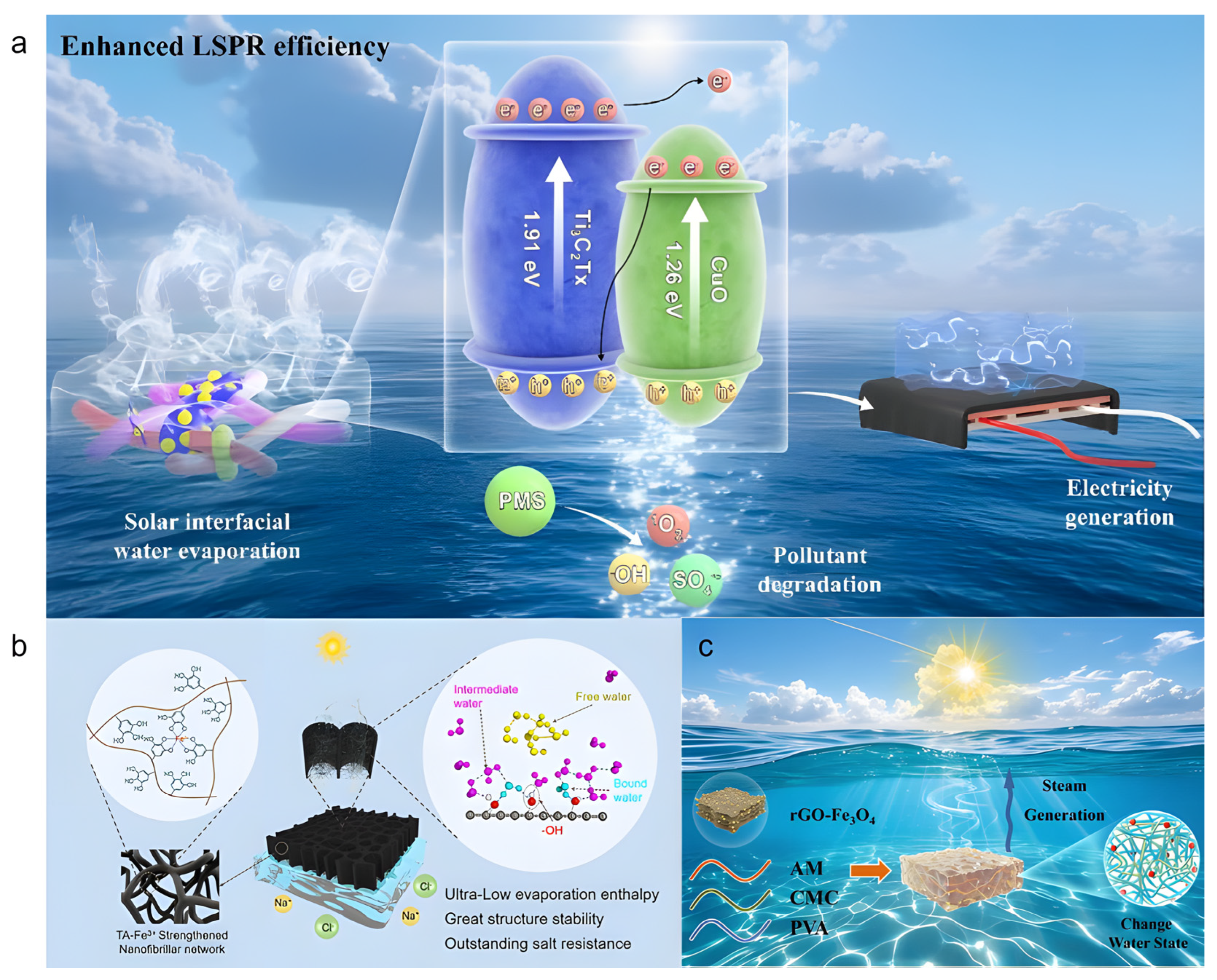

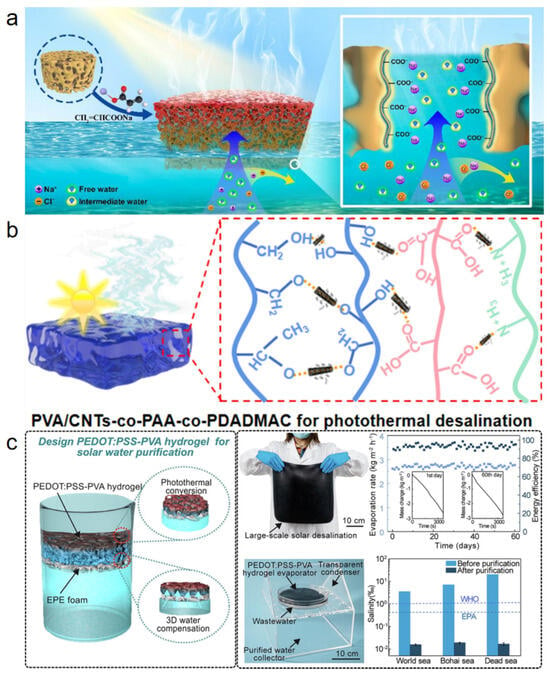

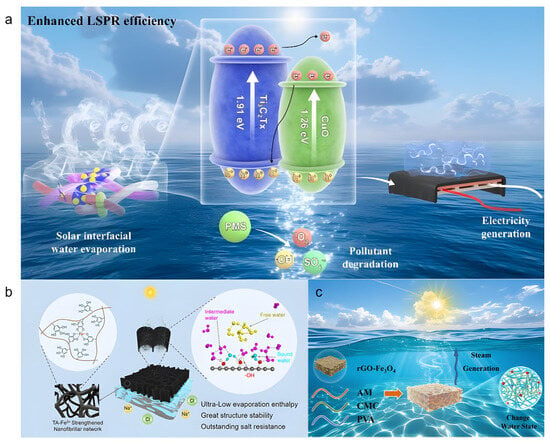

Li et al. [58] fabricated a Ti3C2Tx/CuO photothermal heterojunction via a simple electrostatic adsorption method and incorporated it into a chitosan (CS)/polyacrylic acid (PAA) composite hydrogel (Figure 4a). The introduction of CS significantly reduced the evaporation enthalpy. DSC measurements confirmed that the composite hydrogel exhibited an evaporation enthalpy as low as 940.8 J g−1, contributing to an evaporation rate of 3.14 kg m−2 h−1 in 1 wt% saline with an energy conversion efficiency of 86.6%. Even in 10 wt% brine, the evaporator maintained a rate of 2.56 kg m−2 h−1. The CS/PAA hydrogel matrix, rich in hydrophilic groups (-OH, -NH2, -COOH, and -NH3+), effectively modulated the water state by increasing the fraction of intermediate water and weakening the hydrogen-bonding network. Raman spectroscopy and density functional theory (DFT) calculations further confirmed that the lower hydrogen-bond energy between intermediate water and polymer chains reduced the energy barrier for water escape, thereby enhancing the evaporation rate. This study demonstrates a viable strategy for reducing evaporation enthalpy by regulating the water state in hydrogels, offering valuable insights for designing high-performance solar evaporators.

Figure 4.

(a) Ti3C2Tx/CuO composite hydrogel evaporator. Reproduced with permission [58], (b) HWn-TA-Fe3+ wood hydrogel evaporator. Reproduced with permission [59], (c) PCPR multi-network hydrogel for solar steam generation. Reproduced with permission [60].

Zhang et al. [59] developed a wood-based hydrogel (HWn-TA-Fe3+) using a top-down approach, in which natural rubberwood was partially dissolved and regenerated in a low-temperature NaOH/urea system (Figure 4b). This process constructed a hydrophilic nanofiber network within the wood lumens, significantly increasing the proportion of intermediate water. Raman spectroscopy and low-field NMR analyses confirmed an IW/FW ratio of up to 1.53. The equivalent evaporation enthalpy was measured to be 408 J g−1—only about 17% of that of pure water. Owing to this low evaporation enthalpy, the hydrogel evaporator achieved an evaporation rate of 2.20 kg m−2 h−1 under one-sun illumination. Additionally, the TA-Fe3+ coordination structure enhanced mechanical stability and provided broad-spectrum light absorption of approximately 87%, synergistically improving evaporation performance. A limitation lies in the photothermal absorption capability, which is inferior to high-performance materials such as MXene and graphene, potentially constraining performance under low-light conditions.

Xue et al. [60] designed a jellyfish-inspired multi-network hydrogel evaporator (PCPR) composed of PAM/CMC/PVA/rGO-Fe3O4via free radical polymerization and physical crosslinking (Figure 4c). By tuning the intermediate water content, the evaporation enthalpy was significantly reduced from 2442 J g−1 (pure water) to 1450 J g−1. The incorporation of PVA formed a hydroxyl-rich surface layer that stabilized intermediate water via moderate hydrogen bonding, optimizing the IW/FW ratio to 1.60. As a result, the evaporator achieved an evaporation rate of 1.90 kg m−2 h−1 under one-sun irradiation and maintained 1.82 kg m−2 h−1 in real seawater, demonstrating good salt tolerance and practical potential. However, when the rGO-Fe3O4content exceeded 50 mg, partial blockage of vapor transport channels was observed, impairing water supply. Moreover, the PVA content requires precise control, as deviations from the optimal range reduce the intermediate water ratio.

As summarized in Table 1, a clear inverse correlation exists between the intermediate water proportion and the evaporation enthalpy. Notably, the wood-based hydrogel (HWn-TA-Fe3+) achieves the lowest enthalpy, attributed to its unique nano-fibrous network that massively generates intermediate water. However, its practical evaporation rate is not the highest, limited by its relatively lower light absorption. This highlights a critical point: while reducing evaporation enthalpy is a powerful strategy, the overall evaporation performance is a synergy between enthalpy reduction and other factors, particularly photothermal conversion efficiency. Therefore, the ideal system should balance both aspects, rather than pursuing an ultra-low enthalpy alone.

Table 1.

Inverse correlation between intermediate water proportion and evaporation enthalpy in hydrogel evaporators.

3.2. Structural Optimization

Structural design strategies have been developed for hydrogel-based solar interfacial evaporators to enhance their evaporation rate, primarily focusing on photothermal performance, three-dimensional porous architectures, and thermal management. A synergy between high-performance photothermal materials and optimized surface morphologies serves to enhance light absorption and photothermal conversion efficiency. Tailoring the internal pore structure of the hydrogel and designing efficient water supply pathways facilitate enhanced water transport and salt resistance. The rational design of hydrogel architectures relies heavily on advanced characterization to establish clear structure-property relationships. Techniques such as Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) are crucial for visualizing the macro- and micro-porous structures that govern water transport. Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) provides nanoscale insights into network heterogeneity, which correlates with water state regulation, while Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis quantifies the specific surface area critical for vapor escape and light absorption. The following strategies for structural optimization are fundamentally guided by insights derived from these powerful characterization tools.

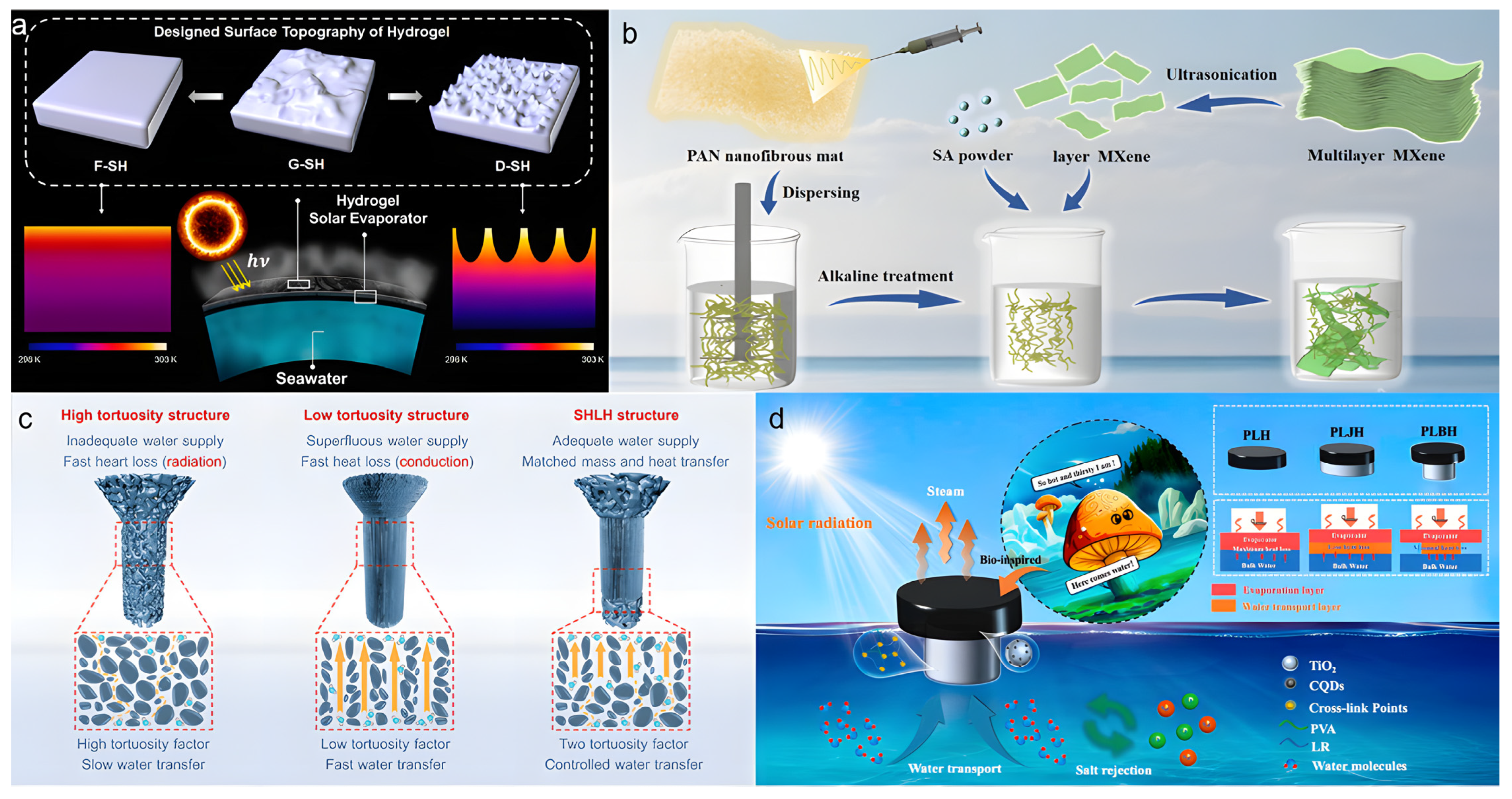

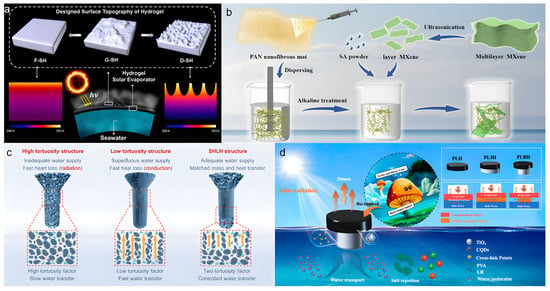

Guo et al. [61] significantly improved solar evaporation performance by tailoring the surface morphology of a PVA-based hydrogel evaporator to enhance light absorption and thermal localization (Figure 5a). Using a template-assisted gelation method, they fabricated PVA hydrogels with flat (F-SH), grooved (G-SH), and sharply dimpled (D-SH) surface structures. The evaluation of the optimal surface morphology was based on multiple criteria: (1) optical performance, i.e., broadband light absorption capacity; (2) thermal management capability, indicated by the surface temperature under illumination; and (3) the ultimate evaporation rate and energy efficiency. The D-SH sample, featuring a hierarchical porous structure and nanoscale roughness, achieved broadband light absorption and low reflectivity, thereby enhancing solar capture capability. The nanostructured surface promoted concentrated heat flux at the evaporation front, raising the interface temperature to approximately 38 °C. When combined with commercial carbon paper, the resulting evaporator attained a high evaporation rate of 2.6 kg m−2 h−1 and an energy efficiency of ~91%. This study demonstrates that customizing hydrogel surface morphology can effectively increase the water evaporation rate. However, the generalizability of this strategy to non-PVA hydrogel systems remains unverified. Furthermore, the long-term stability of such surface structures in complex aqueous environments may be challenging, especially in purely physically crosslinked hydrogels with low mechanical strength, where deformation or damage could compromise photothermal durability.

Figure 5.

(a) Schematic of the surface-modified hydrogel for solar steam generation. Reproduced with permission [61], (b) Preparation process of PMS and mechanism of the crosslinker. Reproduced with permission [62], (c) Evaporators with three tortuosity structures and their corresponding water transport pathways. Reproduced with permission [63], (d) Schematic diagram of the PLBH evaporator for seawater desalination. Reproduced with permission [64].

Wen et al. [62] ingeniously designed and fabricated a nanofiber hydrogel (PMS) with a radially/vertically aligned array structure using a bidirectional freeze-casting technique (Figure 5b). This evaporator features radially aligned outer channels that suppress vertical heat conduction to reduce thermal loss, while internally maintained vertical channels serve as high-speed water pathways to ensure sufficient water supply. This composite architecture synergistically combines the thermal insulation of radial structures with the hydraulic advantages of vertical alignment. Benefiting from this sophisticated design, the evaporator achieved an ultrahigh evaporation rate of 4.62 kg m−2 h−1 and an energy efficiency of 149.57% under one-sun illumination. It also maintained stable operation for 12 h in 20 wt% high-salinity brine, with an average evaporation rate of 3.98 kg m−2 h−1, demonstrating exceptional salt tolerance. Nevertheless, the fabrication process involves complex bidirectional temperature control and precise multi-component formulation, which increases manufacturing complexity and cost. Additionally, the relatively low proportion of vertical channels in the composite structure leaves room for further optimization of its performance contribution. Zhao et al. [63] designed a hydrogel evaporator (TFIPH) with a seamless high-low-high tortuosity (SHLH) structure through tortuosity engineering to optimize 3D water transport pathways, thereby addressing the issue of low energy utilization caused by water-thermal mismatch in conventional evaporators (Figure 5c). By controlling ice crystal growth types during hydrogel preparation, they precisely regulated the tortuosity coefficients in different regions of the hydrogel. This structure effectively balanced photothermal conversion and water supply, enabling the TFIPH evaporator to achieve an evaporation rate of 3.64 kg m−2 h−1 under one-sun irradiation and an exceptional rate of 4.15 kg m−2 h−1 in an outdoor environment. However, precise control of the local tortuosity gradient remains challenging, and the reliance on specific molds and freezing conditions may limit its practical applicability.

Inspired by the transpiration process of mushrooms in nature, Zhang et al. [64] developed a hydrogel evaporator (PLBH) with directional thermal regulation capability (Figure 5d). The evaporator was fabricated from lotus root starch (LR), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and ink-modified carbon quantum dots with TiO2 (I-CQDs-TiO2). It features a biomimetic bilayer structure resembling a mushroom cap and stipe. The bottom slender water transport layer acts as the stipe, promoting upward water transfer via capillary action to supply the cap. The top cap, incorporating I-CQDs-TiO2 as a photocatalyst, enhances solar absorption and photocatalytic efficiency, achieving a broad-spectrum light absorption of 95%. By reducing the contact area with bulk water, the structure effectively suppresses vertical heat conduction to the water body, minimizing heat loss. Under one-sun illumination, the PLBH evaporator reached a surface temperature of 46 °C while the bulk water temperature remained at 32 °C, demonstrating a ~15 °C temperature differential and excellent thermal localization. Additionally, the thermal conductivity of the stipe (0.32 W m−1 K−1) was significantly lower than that of the cap (0.52 W m−1 K−1), further inhibiting downward heat dissipation. These features enabled an evaporation rate of 3.78 kg m−2 h−1 in pure water. However, the mechanical strength of the stipe may be insufficient for long-term use, and the stability of thermal management under extremely high salinity or complex pollutant conditions requires further validation.

The structural optimizations discussed above demonstrate diverse pathways to enhance evaporation rates. Surface morphology engineering (e.g., D-SH) is a relatively straightforward strategy to improve light harvesting and thermal localization, but its durability may be limited. Multi-dimensional channel designs (e.g., PMS and TFIPH) represent a more advanced approach to decouple and optimize the conflicting requirements of water supply and thermal insulation simultaneously, leading to record-high evaporation rates. However, their fabrication processes (e.g., bidirectional freezing) are complex and costly, posing a significant barrier to scalability. In comparison, biomimetic bilayer structures (e.g., PLBH) offer an intelligent and often simpler alternative for effective thermal management by mimicking nature. When evaluating these strategies for real-world application, one must weigh the performance gain against the increased fabrication complexity and cost.

3.3. Long-Term Operational Stability

While the aforementioned strategies have successfully optimized the instantaneous performance of hydrogel evaporators, their long-term operational stability constitutes the ultimate determinant for translating this technology from the laboratory to real-world implementation. The stability data reported in most current studies are limited to short-term tests spanning tens of hours, which falls considerably short of the requirement for months of stable operation in practical scenarios. Achieving long-term stability hinges on the material’s ability to withstand a synergistic assault of multiple environmental stressors, including continuous solar irradiation, cyclic wetting and drying, salt accumulation, biofouling, and exposure to complex chemical contaminants. A systematic dissection and resolution of these stability bottlenecks represent a critical frontier for future research.

The challenges to long-term stability are multifaceted. First, photochemical and mechanical structural integrity are major concerns. Prolonged ultraviolet irradiation can induce photo-oxidative degradation of the polymer network, leading to scission of cross-linking points and loss of hydrophilic groups, resulting in permanent damage to the hydrogel [65]. Concurrently, the inevitable wet-dry cycling and physical disturbances in real-world applications generate repetitive stress within the material, initiating and propagating microcracks that ultimately cause macroscopic structural failure. This issue is particularly acute for physically crosslinked hydrogels. Second, resistance to fouling and tolerance to extreme chemical environments are equally critical. When treating real water sources (e.g., wastewater, high-salinity brine), biofouling and organic pollutants can clog the water transport channels within the hydrogel and form an insulating layer on its surface, drastically reducing evaporation efficiency. Furthermore, extreme salinity (≥20–25 wt%) not only exacerbates the risk of salt crystallization clogging but can also disrupt the hydrogen-bonding network of the hydrogel via a salting-out effect, causing polymer network dehydration and collapse, and consequent loss of water transport capability. Multivalent metal ions (e.g., Ca2+, Mg2+) and surfactants present in wastewater can also induce undesirable irreversible coordination or disrupt hydrophobic associative crosslinks, respectively, compromising material integrity [66].

Addressing these challenges necessitates a paradigm shift in research focus from purely pursuing high performance to co-designing for both performance and application robustness. This calls for the development of more resilient material systems, such as constructing dual-crosslinked or multiple-network hydrogels to enhance mechanical toughness, incorporating inorganic nanomaterials (e.g., TiO2) to synergistically improve photostability and self-cleaning capability, and engineering polyelectrolyte networks to mitigate the destructive effects of salt and ions. More importantly, it is imperative to establish standardized accelerated aging protocols (encompassing UV exposure, wet-dry cycles, high-salinity immersion, and contaminant exposure) and to conduct substantive outdoor evaluations lasting for months or longer. Only by passing such rigorous validation can hydrogel-based solar evaporation technology truly unlock its potential to mitigate the global water crisis.

4. Multifunctional Applications

Owing to their excellent processability and compatibility with other technologies, hydrogel-based solar interfacial evaporators exhibit a broad application potential beyond solar-driven desalination [67]. The solar evaporation process inherently involves variations in light, temperature, and chemical environment. Through systematic exploration of these processes, researchers have developed numerous dual-functional or multi-functional hydrogel-based solar evaporators. Current multifunctional applications primarily include wastewater treatment [68], salt collection [69], and concurrent water-electricity generation [70].

4.1. Wastewater Treatment

Typical pollutants in water bodies include heavy metal ions, organic dyes, radioactive elements, and pesticides. Implementing efficient wastewater treatment strategies is crucial for addressing water pollution and ensuring water security. In this process, extracting radioactive metals such as uranium not only alleviates environmental pressure but also promotes resource recycling and reuse. Hydrogels, rich in various functional groups, demonstrate remarkable adsorption capabilities for pollutants like heavy metal ions and organic dyes, making them promising materials for wastewater treatment. Consequently, integrating hydrogels with solar interfacial evaporation technology offers a promising approach to simultaneously achieve efficient water evaporation and advanced wastewater purification within a single process.

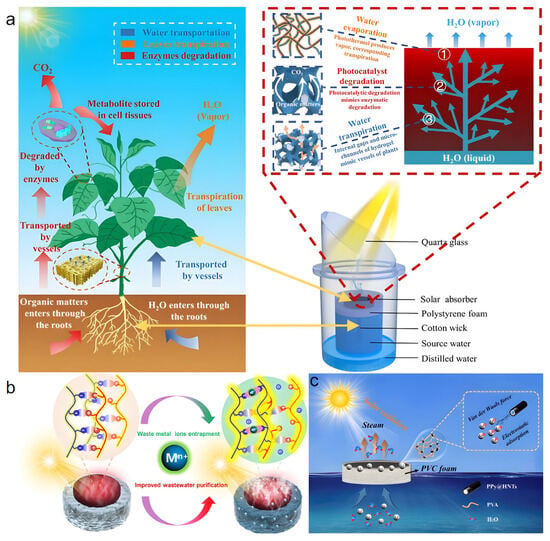

Wang et al. [71] developed a bionic solar-driven interfacial evaporation system using a novel TiO2/Ti3C2/C3N4/PVA (TTCP) composite hydrogel evaporator (Figure 6a), which combines photothermal evaporation with photocatalytic degradation for synergistic treatment of wastewater containing volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Under 1 kW m−2 simulated sunlight, the system achieved an evaporation rate of 1.54 kg m−2 h−1 and removal efficiencies for phenol ranging from 69.4% to 100%. It also demonstrated excellent desalination and organic removal capabilities in practical water samples (seawater, lake water, reclaimed water), reducing total dissolved solids (TDS) by over two orders of magnitude, achieving up to 80% total organic carbon (TOC) removal, and lowering the concentrations of seven ions (including Na+ and K+) by more than one order of magnitude. Under natural sunlight, the TTCP evaporator maintained an evaporation rate of 0.72 kg m−2 h−1 and a TOC removal rate of 74%. This study holds promise for accelerating the application of solar distillation technology in producing clean water. However, the evaporation rate under actual sunlight was significantly lower (by 71%) than under simulated conditions, attributed to partial shading of light by condensed vapor outdoors, indicating the need for further optimization of stability and adaptability in real-world environments.

Figure 6.

(a) Schematic illustrating the similarity between plants and the bionic system. Reproduced with permission [71], (b) Working mechanism schematic of the PCC hydrogel for wastewater purification. Reproduced with permission [72], (c) NPH evaporator for efficient solar evaporation and lithium ion adsorption. Reproduced with permission [73].

Zuo et al. [72] fabricated a solar interfacial evaporator (PCC) based on a polyionic complex (PIC) hydrogel combined with low-cost coal powder (CP) for efficient purification of industrial wastewater containing multivalent metal ions (Figure 6b). Under one-sun illumination, the evaporator achieved an evaporation rate of 3.6 kg m−2 h−1 for simulated 3.5 wt% CaCl2 wastewater and operated stably for three weeks in real coal washing wastewater. Its excellent performance stems from the PIC hydrogel’s ability to capture multivalent metal ions: captured ions increase the proportion of intermediate water by modulating water states, significantly reducing evaporation enthalpy, while strong coordination from ions like Ca2+ enhances polymer network stability, maintaining the porous structure and water transport capacity. However, although coal powder is inexpensive, its potential leaching risk and long-term chemical stability in complex water quality were not fully assessed, which may limit its application in certain sensitive water treatment scenarios.

Zhou et al. [73] developed a polypyrrole-modified halloysite nanotube (PPy@HNTs) and polyvinyl alcohol composite hydrogel (NPH) for simultaneous efficient solar evaporation and lithium ion adsorption (Figure 6c). The hydrogel achieved an evaporation rate and efficiency of 2.97 kg m−2 h−1 and 93.2%, respectively, under one-sun illumination, along with excellent salt tolerance and anti-fouling properties. When treating high-salinity wastewater, the total dissolved solids in the output water were significantly reduced, meeting drinking water standards. Notably, the NPH evaporator exhibited strong adsorption capacity for Li+ during evaporation, reaching equilibrium within 5 min with a maximum adsorption capacity of 168.3 mg g−1, and maintained 50.5% adsorption after 5 cycles, demonstrating good reusability potential. However, the study did not thoroughly investigate Li+ adsorption selectivity or competitive mechanisms in the presence of multiple ions in complex real water bodies. The noticeable decrease in adsorption capacity during cycling indicates that regeneration performance needs further improvement.

4.2. Salt Collection

To achieve resource utilization of saline components in seawater, a localized crystallization strategy has been proposed to effectively manage salt crystallization during evaporation. This strategy precisely controls internal water transport and distribution within the evaporator, guiding salt to selectively crystallize in specific peripheral areas such as the edges. The core advantage of this method is its ability to harvest solid salt while fundamentally preventing the reflux of concentrated brine, thereby protecting the aquatic environment.

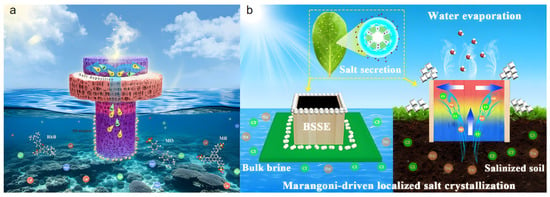

Yan et al. [74] proposed a Janus-structured 3D PVA/rGO hydrogel solar interfacial evaporator (Figure 7a). The mushroom-shaped Janus structure allows localized preferential salt crystallization and provides additional heating for sidewall evaporation, preventing salt scaling on the evaporation interface during desalination. The evaporator consists of an upper super-hydrophilic mushroom cap (SL-PVC layer) and a lower annular hydrophobic stipe (B-PVC layer). During evaporation, the top SL-PVC layer, due to its good water supply capacity, promptly removes interfacial salt via salt ion diffusion and reflux. The annular hydrophobic B-PVC layer, having a higher surface temperature, exerts an additional heating effect on the adjacent SL-PVC sidewalls, accelerating water evaporation in this region and guiding salt ions to reach supersaturation and crystallize preferentially at the contact area between SL-PVC and B-PVC. This directed salt crystallization mechanism ensured no salt accumulation on the main evaporation surface after 12 h of continuous operation in 20 wt% high-salinity brine. Salt was successfully collected in specific edge regions, allowing the evaporator to maintain a high evaporation rate of 3.71 kg m−2 h−1 while effectively preventing performance degradation due to salt scaling, offering a potential green and sustainable method for inorganic salt extraction from seawater.

Figure 7.

(a) Mushroom-shaped Janus-structured PVA/rGO hydrogel solar interfacial evaporator. Reproduced with permission [74], (b) Schematic of the BSSE biomimetic salt-secreting evaporator for salt collection. Reproduced with permission [75].

Inspired by the salt secretion mechanism of mangrove leaves, Chen et al. [75] designed a biomimetic salt-secreting evaporator (BSSE) composed of a wood shell filled with photothermal hydrogel (Figure 7b), inducing salt crystallization outside the vapor generation interface during water evaporation. Through regionally differentiated thermal management and evaporation regulation, the BSSE induced Marangoni convection—driven jointly by thermocapillary and solutocapillary effects—which transported salt ions from the high-evaporation-rate hydrogel region to the cooler wood edges for crystallization, effectively avoiding salt clogging at the evaporation interface. The evaporator achieved a high evaporation rate of 2.08 kg m−2 h−1 in 20 wt% high-salinity water and could operate continuously for 100 h without cleaning, demonstrating exceptional long-term salt resistance and salt collection capability. Furthermore, the BSSE could effectively extract salt from saline soil and permanently reduce its internal salinity, providing a rational solution for simultaneously addressing global water and food problems. However, the universal applicability of Marangoni convection for regulating different salt components requires further investigation.

4.3. Concurrent Water-Electricity Generation

Developing solar-based cogeneration systems for freshwater and power with a low carbon footprint has become an important research focus. Interfacial solar evaporation technology, as an effective pathway towards this goal, has attracted significant attention recently. This process can not only harvest solar energy to produce vapor but also utilize various mechanisms—such as salinity and temperature gradients between the system and the environment during solar-to-vapor and vapor-to-water conversions—to achieve synergistic multi-energy conversion and electricity output.

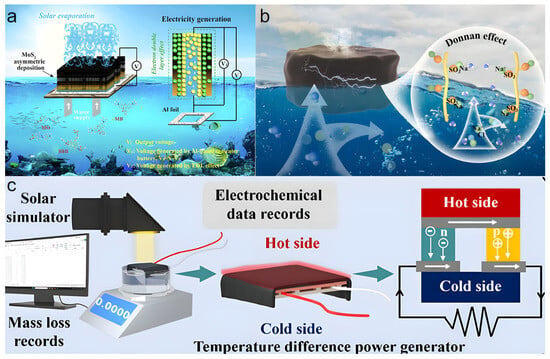

Wang et al. [76] proposed a PVA/cellulose hydrogel evaporator with an asymmetric distribution of MoS2 (Figure 8a). By introducing hydroxypropyl cellulose rich in hydrophilic groups into the PVA network, an interconnected porous structure was constructed. This not only reduced the evaporation enthalpy to as low as 1352.35 J g−1 and enhanced the evaporation rate (reaching 3.23 kg m−2 h−1 in 3.5 wt% saline) but also provided ideal nanochannels for ion transport and charge separation. MoS2 acted as both a photothermal material and a negatively charged carrier. Its asymmetric distribution created a carrier concentration gradient within the hydrogel, generating an output voltage of 0.182 V based on the electric double layer (EDL) effect. To further enhance power generation, the study innovatively combined the hydrogel evaporator with aluminum foil to construct an aluminum-based seawater battery system. In this hybrid mode, the oxidation reaction of the aluminum electrode synergized with the EDL effect, ultimately producing a stable output voltage as high as 0.714 V when treating 3.5 wt% saline under one-sun illumination, with no performance degradation after 10 cycles, while the evaporation rate remained unaffected. This work successfully expanded the solar interfacial evaporation system into a small-scale power generation platform through ingenious material and structural design, providing a valuable reference for developing multifunctional systems integrating freshwater production and energy self-supply.

Figure 8.

(a) PVA/cellulose hydrogel evaporator with asymmetric MoS2 for power generation. Reproduced with permission [76], (b) Schematic of the CAN2 hydrogel for clean water and power generation. Reproduced with permission [77], (c) Schematic of the thermoelectric cogeneration device and the principle of thermoelectric generation. Reproduced with permission [77].

Jing et al. [77] made significant progress in this area by successfully integrating a sulfonate-based polyanionic hydrogel (CAN2) evaporator with a thermoelectric module using the Donnan effect, constructing an efficient and stable water-electricity cogeneration device (Figure 8b,c). The hydrogel evaporator itself exhibited a high evaporation rate of 2.23 kg m−2 h−1 in 20 wt% high-salinity brine. During evaporation, waste heat generated at the hydrogel surface was captured by the underlying thermoelectric module and converted into electricity based on the Seebeck effect. Results showed that under one-sun illumination, the cogeneration device could generate an open-circuit voltage of 80.4 mV and a short-circuit current of 15.2 mA, with a maximum output power density of 0.37 W m−2, while maintaining an excellent evaporation rate of 1.85 kg m−2 h−1. The system demonstrated stable current output under different light intensities, and its power generation reliability and durability were verified through cyclic light-on/off experiments. This work provides a new design strategy and technical pathway for developing hydrogel-based water-electricity cogeneration systems suitable for high-salinity environments.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Owing to their efficient solar-driven water evaporation, hydrogel-based solar interfacial evaporators have shown great promise in recent years for applications in desalination and related fields. Through precise regulation of parameters such as surface morphology, and three-dimensional porous structures, researchers have successfully constructed evaporation systems with specific water molecule states and excellent water transport properties, significantly enhancing evaporation rates and salt resistance (Table 2). This comparative analysis underscores inherent trade-offs. Physically crosslinked hydrogels typically enable greater evaporation enthalpy reduction, whereas their chemically crosslinked counterparts provide superior mechanical and long-term stability. Similarly, intricate structural designs achieve higher evaporation rates but increase manufacturing complexity and cost. Consequently, the pursuit of ultimate performance under ideal laboratory conditions must be balanced with the imperative of robustness and scalability for practical deployment. This review systematically summarizes recent research progress in material design, performance optimization, and multifunctional applications of hydrogel-based solar interfacial evaporators. In material design, the article elaborates on two main synthesis approaches: physical crosslinking (e.g., hydrogen bonding, ionic bonding, hydrophobic association) and chemical crosslinking (e.g., free radical polymerization, condensation reactions), revealing how different crosslinking mechanisms impart specific mechanical strength, self-healing properties, or structural stability to hydrogels. Regarding performance enhancement, core strategies focus on reducing evaporation enthalpy and optimizing structural design. Regulating hydrophilic functional groups and nano-pore structures within hydrogels can effectively convert part of the bulk water into intermediate water with lower evaporation energy barriers, significantly increasing the evaporation rate. Constructing 3D porous channels, designing surface morphologies, and developing biomimetic structures have synergistically optimized light absorption, water transport, and thermal management, substantially increasing evaporation rates. Furthermore, the scalability of hydrogels has extended their applications beyond mere desalination, showing great potential in emerging multifunctional fields such as wastewater treatment, salt collection, and concurrent water-electricity generation, marking a trend towards integrated and intelligent system development.

Table 2.

Summary of the performance of representative hydrogel-based solar interfacial evaporators.

Despite significant progress in understanding the evaporation mechanisms and optimizing performance, this technology still faces numerous challenges in practical applications. Future research should focus on simplifying preparation processes to promote scaling and industrialization. Mainstream methods like physical crosslinking and radiation polymerization are often limited by high costs and complex processes, whereas chemical crosslinking shows greater potential in terms of process simplicity, cost control, and mechanical strength, making it a promising primary direction for future hydrogel evaporator development. In enhancing evaporation performance, further reducing evaporation enthalpy remains a key breakthrough point. Rationally introducing hydrophilic functional groups and constructing nanostructured pores can effectively regulate water molecule states, increase the proportion of intermediate water, and thereby lower the energy required for evaporation, achieving higher evaporation efficiency. Structural design optimization is also crucial; the water transport capacity of the evaporator must match the evaporation rate. Designing specific surface morphologies, optimizing internal water channels, enhancing sidewall heat exchange, and integrating thermal insulation layers can significantly improve the system’s thermal management efficiency and overall evaporation performance. Regarding the industrial scaling of complex structures (e.g., SHLH, PMS), the prospects are promising but hinge on overcoming key challenges. The primary barriers are the scalability of sophisticated fabrication techniques (e.g., bidirectional freezing) and associated costs. Future work must focus on developing simpler, more scalable manufacturing processes that can reproduce these optimal structures without compromising performance. Success in this area would enable the deployment of high-efficiency hydrogel evaporators in large-scale desalination and water treatment plants. Long-term operational stability is another critical factor determining practical feasibility. Salt deposition remains a major issue affecting performance under high salinity conditions. Additionally, expanding the multifunctional integrated applications of hydrogel-based solar interfacial evaporators is an important direction for enhancing their system value and energy utilization efficiency. Integrating them with technologies like salt collection, wastewater treatment, water-electricity cogeneration, and even hydrogen-water co-production to build multifunctional synergistic systems can not only achieve freshwater production but also simultaneously accomplish energy recovery, resource extraction, and pollution control, providing comprehensive solutions to global resource challenges.

Beyond the technical performance, the economic viability and environmental sustainability of hydrogel-based evaporators are critical determinants of their practical adoption. A thorough assessment of the manufacturing costs, including raw materials and fabrication processes, is essential to evaluate the feasibility of producing these evaporators on a large scale (e.g., per square meter). Furthermore, the environmental impact of advanced photothermal materials, such as the potential ecological toxicity of MXene residues or the biocompatibility concerns associated with PEDOT:PSS, must be rigorously investigated throughout their life cycle. Future research should prioritize the development of cost-effective, abundantly available, and environmentally benign materials to ensure the sustainable development of this promising technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and H.L.; Methodology, X.Z.; Software, X.Z., H.N. and D.L.; Validation, X.Z., H.N. and D.L.; Formal Analysis, X.Z.; Investigation, X.Z.; Resources, X.Z.; Data Curation, X.Z., H.N. and D.L.; Writing-Original Draft Preparation, X.Z.; Writing-Review & Editing, H.L.; Visualization, X.Z.; Supervision, H.L.; Project Administration, H.L.; Funding Acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Project No. 51804213, Anhui Engineering Research Center for Coal Clean Processing and Carbon Reduction (CCCE-2023002), Fundamental Re-search Program of Shanxi Province (202203021221041), High-Level Overseas Talent Re-turn Funding Project Translation of Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, which is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Recent Advances and Challenges of Metal-Based Materials for Solar Steam Generation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2307533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, S.C. Device design and optimization of sorption-based atmospheric water harvesters. Device 2023, 1, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M. Global water shortage and potable water safety; Today’s concern and tomorrow’s crisis. Environ. Int. 2022, 158, 106936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanlon, B.R.; Fakhreddine, S.; Rateb, A.; De Graaf, I.; Famiglietti, J.; Gleeson, T.; Grafton, R.Q.; Jobbagy, E.; Kebede, S.; Kolusu, S.R.; et al. Global water resources and the role of groundwater in a resilient water future. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Thomas, A.; Li, C. Emerging Materials for Interfacial Solar-Driven Water Purification. Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202214391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Rathod, N.H.; Sharma, J.; Kulshrestha, V. Long side-chain type partially cross-linked poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) anion exchange membranes for desalination via electrodialysis. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 622, 119034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cao, B.; Li, P. Fabrication of High Performance Pervaporation Desalination Composite Membranes by Optimizing the Support Layer Structures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 11178–11185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melliti, E.; Van der Bruggen, B.; Elfil, H. Combined iron oxides and gypsum fouling of reverse osmosis membranes during desalination process. J. Membr. Sci. 2022, 653, 120472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Li, M.; Hoek, E.M.V.; Heng, Y. Supercomputing and machine learning-aided optimal design of high permeability seawater reverse osmosis membrane systems. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaji, A.D.; Kutubkhanah, I.K.; Wie, J.-M. Advances in seawater desalination technologies. Desalination 2008, 221, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, G.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, G.; Lei, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Xue, L. Superwetting reduced graphene oxide/alginate hydrogel sponge with low evaporation enthalpy for highly efficient solar-driven water purification. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 455, 140704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.-J.; Wang, X.; Xue, C.-H.; Liu, B.-Y.; Wu, Y.-G.; Zhang, D.; Deng, F.-Q.; An, Q.-F.; Pu, Y.-P. Salt-blocking three-dimensional Janus evaporator with superwettability gradient for efficient and stable solar desalination. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 644, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zou, T.; Cui, X.; Ding, M.; Zhang, B.; Yang, X.; Han, Y.; Nie, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, E.; et al. In situ polymerization of polypyrrole in oil body for efficient solar-driven freshwater collection. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 468, 143619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Huang, K.; Meng, X. Review on solar-driven evaporator: Development and applications. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 119, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Bae, J.; Fang, Z.; Li, P.; Zhao, F.; Yu, G. Hydrogels and Hydrogel-Derived Materials for Energy and Water Sustainability. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7642–7707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y. Direction-limited water transport and inhibited heat convection loss of gradient-structured hydrogels for highly efficient interfacial evaporation. Sol. Energy 2020, 201, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Zhang, Y.; Tan, S.C. Functionalizing solar-driven steam generation towards water and energy sustainability. Nat. Water 2025, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Guo, Y.; Yu, G. Carbon Materials for Solar Water Evaporation and Desalination. Small 2021, 17, 2007176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yan, Z.; Li, Y.; Hong, W. Latest development in salt removal from solar-driven interfacial saline water evaporators: Advanced strategies and challenges. Water Res. 2020, 177, 115770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Huang, Y.; You, S.; Xiang, Y.; Cai, E.; Mao, R.; Pan, W.; Tong, X.; Dong, W.; Ye, F.; et al. Engineering Robust Ag-Decorated Polydopamine Nano-Photothermal Platforms to Combat Bacterial Infection and Prompt Wound Healing. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2106015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Gao, Y.; Sun, Y.; Qi, Y.; Yin, W.; Wang, S.; Yin, F.; Dai, Z.; Gao, B.; Yue, Q. Manipulating a vertical temperature-gradient of Fe@Enteromorpha/graphene aerogel to enhanced solar evaporation and sterilization. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 3750–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Men, C.; Zhao, L.; Cao, P.; Yang, Z.; Niu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, Q. Spontaneous Salt-Preventing Solar–Thermal Water Evaporator with a High Evaporation Efficiency through Dual-Mode Water Transfer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 15549–15557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, B.; Lyu, Q.; Li, M.; Du, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L. Phase-Separated Polyzwitterionic Hydrogels with Tunable Sponge-Like Structures for Stable Solar Steam Generation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2214045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, F.; Guo, Z.; Cheng, H.; Yin, J.; Yan, L.; Wang, X. Flexible and Efficient Solar Thermal Generators Based on Polypyrrole Coated Natural Latex Foam for Multimedia Purification. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 12053–12062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Chao, Y.; Tang, H.; Liang, Y.; Yuan, J.; et al. Enhanced solar-driven interfacial evaporation using composite hydrogel and nano filter films for sustainable water transport and salt resistance. Desalination 2025, 600, 118488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Yang, H.; Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Wang, C.; Ho, S.-H. Wood-inspired anisotropic PU/chitosan/MXene aerogel used as an enhanced solar evaporator with superior salt-resistance. Desalination 2023, 555, 116462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Ma, C.; Wang, P.; Che, H.; Xu, H.; Ao, Y. Rationally constructing a 3D bifunctional solar evaporator for high-performance water evaporation coupled with pollutants degradation. Appl. Catal. B 2023, 337, 122988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Gong, J.; Zhang, C.; Tang, W.; Wei, B.; Wang, J.; Fu, Z.; Li, L.; Li, W.; Xia, L. Hierarchically porous carbonized Pleurotus eryngii based solar steam generator for efficient wastewater purification. Renew. Energy 2023, 216, 118987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, M.; Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Fu, Q.; Deng, H. Recent progress in solar photothermal steam technology for water purification and energy utilization. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 448, 137603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Jin, Y. A Ternary Pt/Au/TiO2-Decorated Plasmonic Wood Carbon for High-Efficiency Interfacial Solar Steam Generation and Photodegradation of Tetracycline. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, W. Tailorable Lignocellulose-Based Aerogel to Achieve the Balance between Evaporation Enthalpy and Water Transport Rate for Efficient Solar Evaporation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 11827–11836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Mu, H.; Han, X.; Sun, T.; Fan, X.; Lv, B.; Pan, Z.; Song, Y.; Song, C. A simple, flexible, and porous polypyrrole-wax gourd evaporator with excellent light absorption for efficient solar steam generation. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 21476–21486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Wu, P.; Zhao, J.; Yang, X.; Owens, G.; Xu, H. Enhancing solar steam generation using a highly thermally conductive evaporator support. Sci. Bull. 2021, 66, 2479–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, X.; Shi, W.; Yu, G. Materials for solar-powered water evaporation. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, D.; Xu, X.; Bai, B.; Du, M. A polyelectrolyte hydrogel coated loofah sponge evaporator based on Donnan effect for highly efficient solar-driven desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 462, 142265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, F.; Yu, G. Hydrogels as an Emerging Material Platform for Solar Water Purification. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 3244–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, P.; Tian, J.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Fei, X.; Li, Y. A novel composite hydrogel for solar evaporation enhancement at air-water interface. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 668, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, K.; Guo, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y. Synergy of Light Trapping and Water Management in Interconnected Porous PEDOT:PSS Hydrogels for Efficient Solar-Driven Water Purification. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 10175–10183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, L.; Liu, F.; Astruc, D.; Gu, H. Supramolecular redox-responsive ferrocene hydrogels and microgels. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 419, 213406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Dong, Z.; Ren, X.; Jia, B.; Li, G.; Zhou, S.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W. High-strength hydrogels: Fabrication, reinforcement mechanisms, and applications. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 3475–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, F.; Shi, W.; Yu, G. Topology-Controlled Hydration of Polymer Network in Hydrogels for Solar-Driven Wastewater Treatment. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2007012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-García, I.; Lemma, M.R.D.C.; Barud, H.S.; Eceiza, A.; Tercjak, A. Hydrogels based on waterborne poly(urethane-urea)s by physically cross-linking with sodium alginate and calcium chloride. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 250, 116940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cheng, G.; Wang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, Q. Bifunctional lignocellulose nanofiber hydrogel possessing intriguing pH-responsiveness and self-healing capability towards wound healing applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 260, 129398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhu, B.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Meng, R.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z. Polyelectrolyte-based photothermal hydrogel with low evaporation enthalpy for solar-driven salt-tolerant desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 134224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, A.; Fu, D.; Lin, P.; Wang, X.; Xia, Y.; Han, X.; Zhang, T. Eco-friendly photothermal hydrogel evaporator for efficient solar-driven water purification. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 647, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, R.; Tang, X.; Tan, J.Y.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Z.; Xia, X.; Fu, S. Multi-bionic Strategies Integration in Cellulose Nanofiber-Based Metagels with Strong Hydrogen-Bonded Network for Solar-Driven Water Evaporation. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2025, 7, 748–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, J.; Lv, S.; He, T.; Chen, Y.; Mu, Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, L. Construction of MXene/gelatin foam hydrogel with multi-stage porous for efficient solar-driven interfacial evaporation and ion removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 524, 169806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, B.; Yao, D.; Gao, X.; Chen, J.; Lu, C.; Pang, X. Enhancing salt resistance and all-day efficient solar interfacial evaporation of antibacterial sodium alginate-based porous hydrogels via surface patterning. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 359, 123588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichifor, M. Role of Hydrophobic Associations in Self-Healing Hydrogels Based on Amphiphilic Polysaccharides. Polymers 2023, 15, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Peng, Y.; Shi, L.; Ran, R. Highly Efficient Solar Evaporator Based On a Hydrophobic Association Hydrogel. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 18114–18125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chu, A.; Chen, J.; Qiao, P.; Fang, J.; Yang, Z.; Duan, Z.; Li, H. Spongy polyelectolyte hydrogel for efficient Solar-Driven interfacial evaporation with high salt resistance and compression resistance. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 150118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Chen, J.; Fang, J.; Wu, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, H. Porous and Salt-Tolerant Polyelectrolyte Hydrogels for Excellent Solar Evaporation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 1849–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, J.; Wu, Z.; Xu, X.; Ma, H.; Hou, J.; Xu, Q.; Yang, R.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, M.; et al. Robust PEDOT:PSS-based hydrogel for highly efficient interfacial solar water purification. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 442, 136284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Zou, X.; Xing, L.; Liu, W.; Huang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Wang, J. Biomass-Based Ferric Tannate Hydrogel with a Photothermal Conversion Function for Solar Water Evaporation. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 9574–9584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, B.; Sha, Z.; Zhu, H.; Wu, Z.; Nawaz, F.; Wei, Y.; Luo, L.; Que, W. Low vaporization enthalpy hydrogels for highly efficient solar-driven interfacial evaporation. Desalination 2023, 568, 116999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, F.; Jiao, Z.; Zhou, X.; Yu, G. Tailoring surface wetting states for ultrafast solar-driven water evaporation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 2087–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; He, N.; Jiang, B.; Yu, K.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Tang, D.; Song, Y. Highly Salt-Resistant 3D Hydrogel Evaporator for Continuous Solar Desalination via Localized Crystallization. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2104380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, F.; Jing, X.; Zhou, W.; Pei, S.; Abdiryim, T.; Xu, F.; You, J.; Tan, Y.; Liu, X. Ti3C2Tx/CuO composite hydrogels with low evaporation enthalpy and efficient photothermal conversion for solar-driven water purification, electricity generation and pollutant degradation. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Peng, Y.; Xu, X.; Sun, J.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Che, W.; Yu, Y. Intermediate water engineering in wood hydrogels for ultra-low enthalpy solar desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Qi, C.; Li, W. Jellyfish-Head Core-Shell Structured Hydrogel Evaporator with Low Enthalpy and Excellent Salt-Resistance for Highly Efficient Solar Desalination. Small 2025, 21, e07650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhou, X.; Chen, Z.; Yu, G. Tailoring Nanoscale Surface Topography of Hydrogel for Efficient Solar Vapor Generation. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 2530–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Deng, S.; Xie, Q.; Guo, F.; Huang, H.; Sun, C.; Ren, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Cheng, S. Nanofibrous Hydrogel with Highly Salt-Resistant Radial/Vertical-Combined Structure for Efficient Solar Interfacial Evaporation. Small 2025, 21, 2411780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wang, C.; Wei, D.; Hu, Q.; Tan, P.; Wang, F.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J. Tortuosity Engineering of Water Channels to Customized Water Supply for Enhancing Hydrogel Solar Evaporation. Small 2024, 20, 2402482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Du, Y.; Xie, W.; Zheng, S.; Yang, L.; Shi, J.; Jing, D. Biomimetic hydrogel with directional heat regulation for efficient solar desalination. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 473, 145484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Liang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Lohwacharin, J.; Lichtfouse, E.; Wang, C. Advances in Hydrogel-Based Photothermal Interfacial Solar Steam Generation: Classifications, Mechanisms, and Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2509130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yang, J.; Tu, Y.; Su, Z.; Guan, Q.; Ma, Z. Hydrogel-Based Interfacial Solar-Driven Evaporation: Essentials and Trails. Gels 2024, 10, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Liu, K.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; Duan, J.; Xue, G.; Xu, Z.; Xie, W.; Zhou, J. Solar-driven simultaneous steam production and electricity generation from salinity. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 1923–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ma, H.; Wu, M.; Lin, T.; Yao, H.; Liu, F.; Cheng, H.; Qu, L. A reconfigurable and magnetically responsive assembly for dynamic solar steam generation. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]