Recycling of Polypropylene with Vitamin E Additives: Rheological Properties and Mechanical Characteristics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

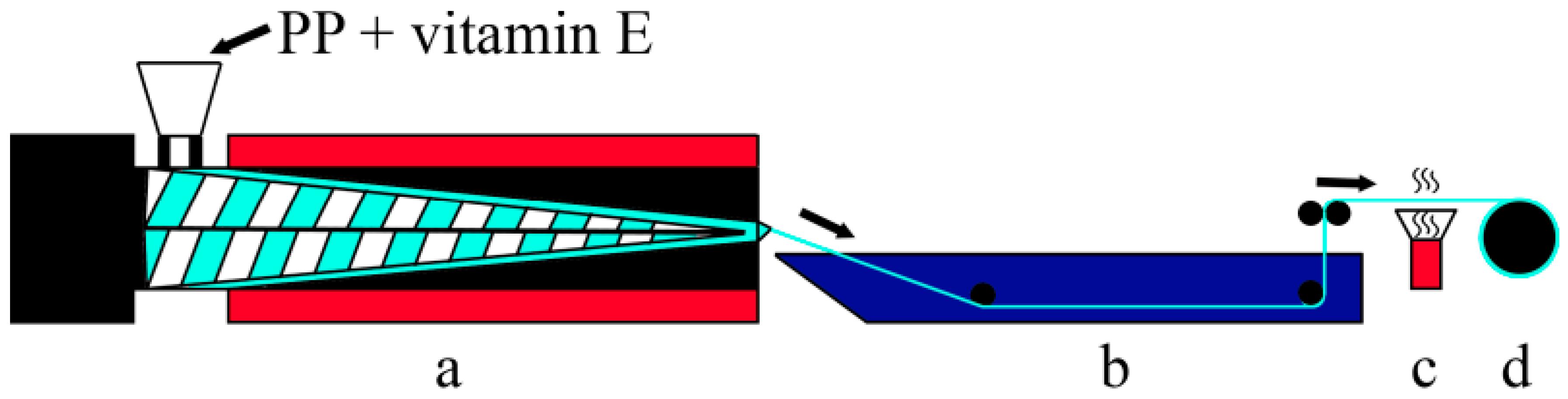

2.1. Macrofiber Spinning

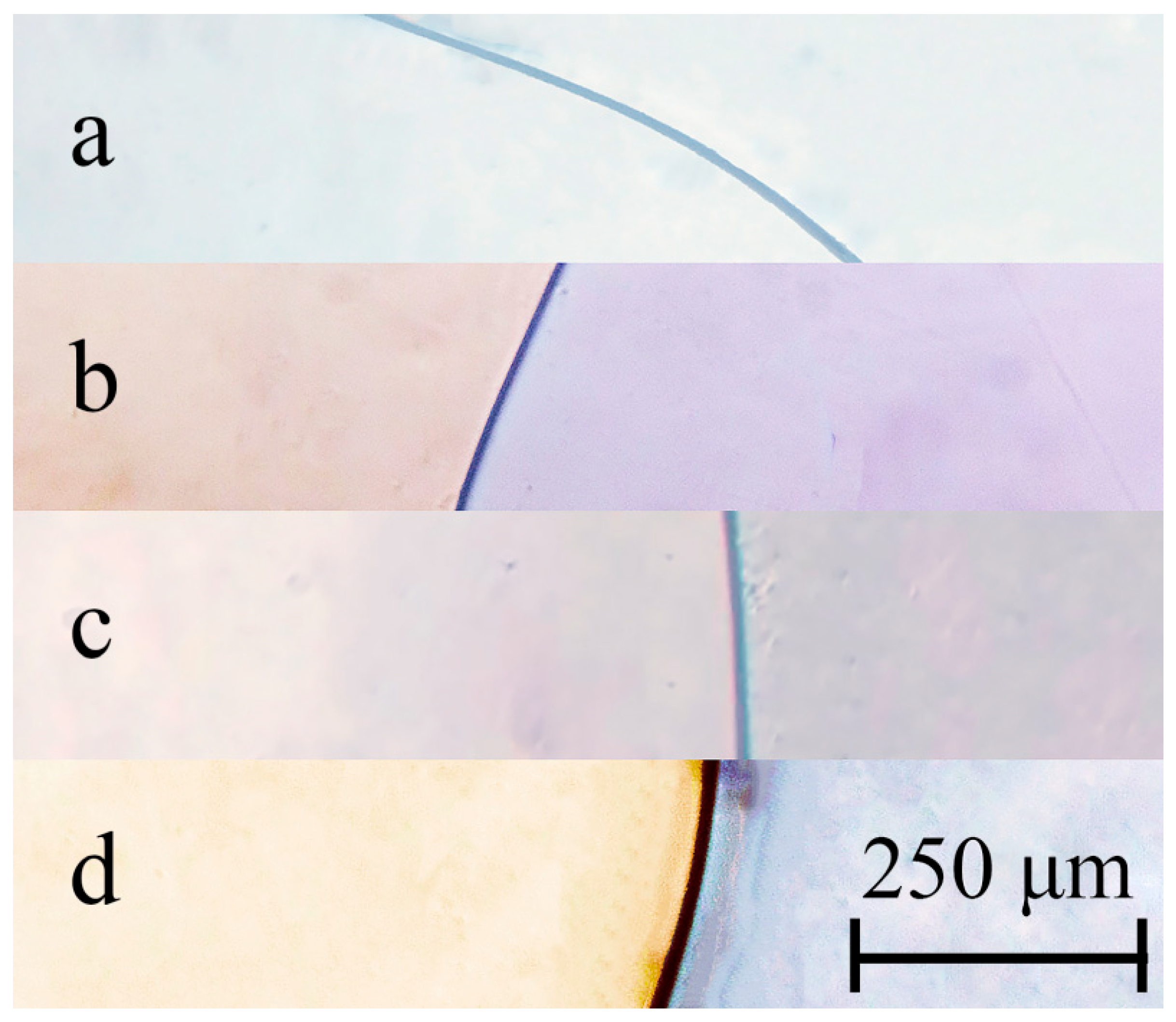

2.2. Characterization of Polypropylene Macrofibers

3. Results and Discussions

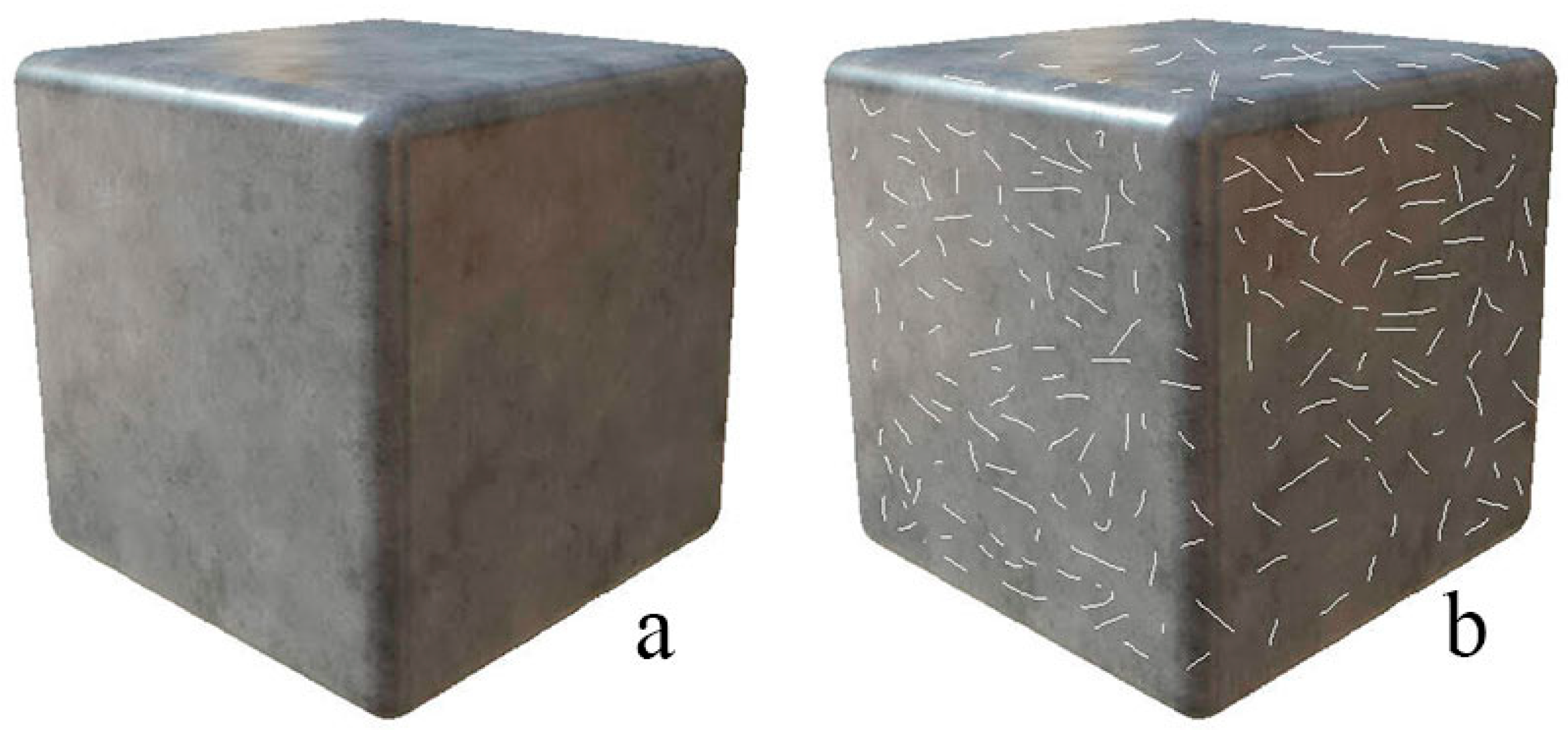

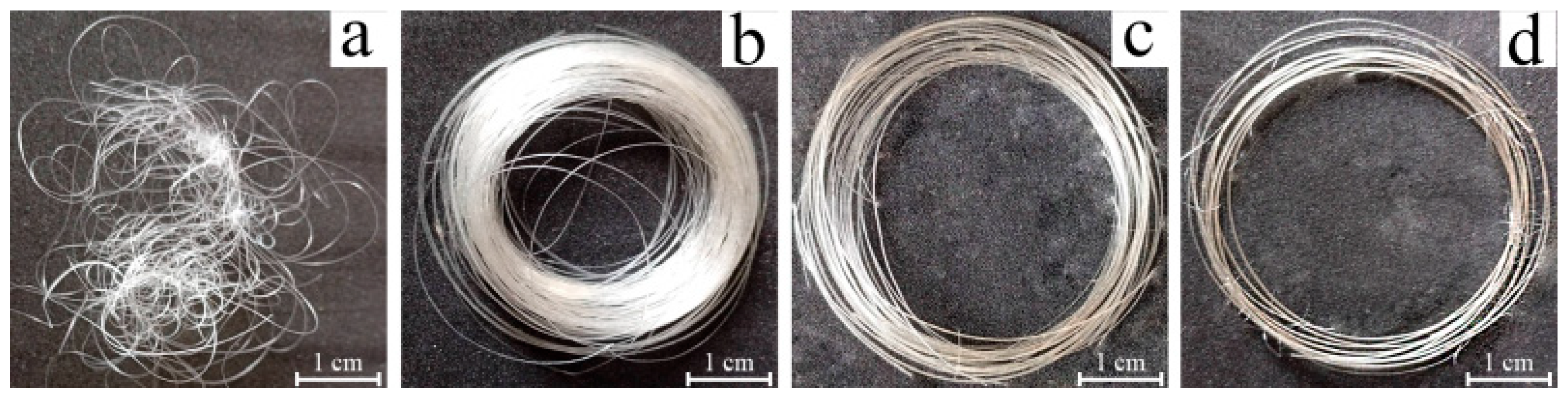

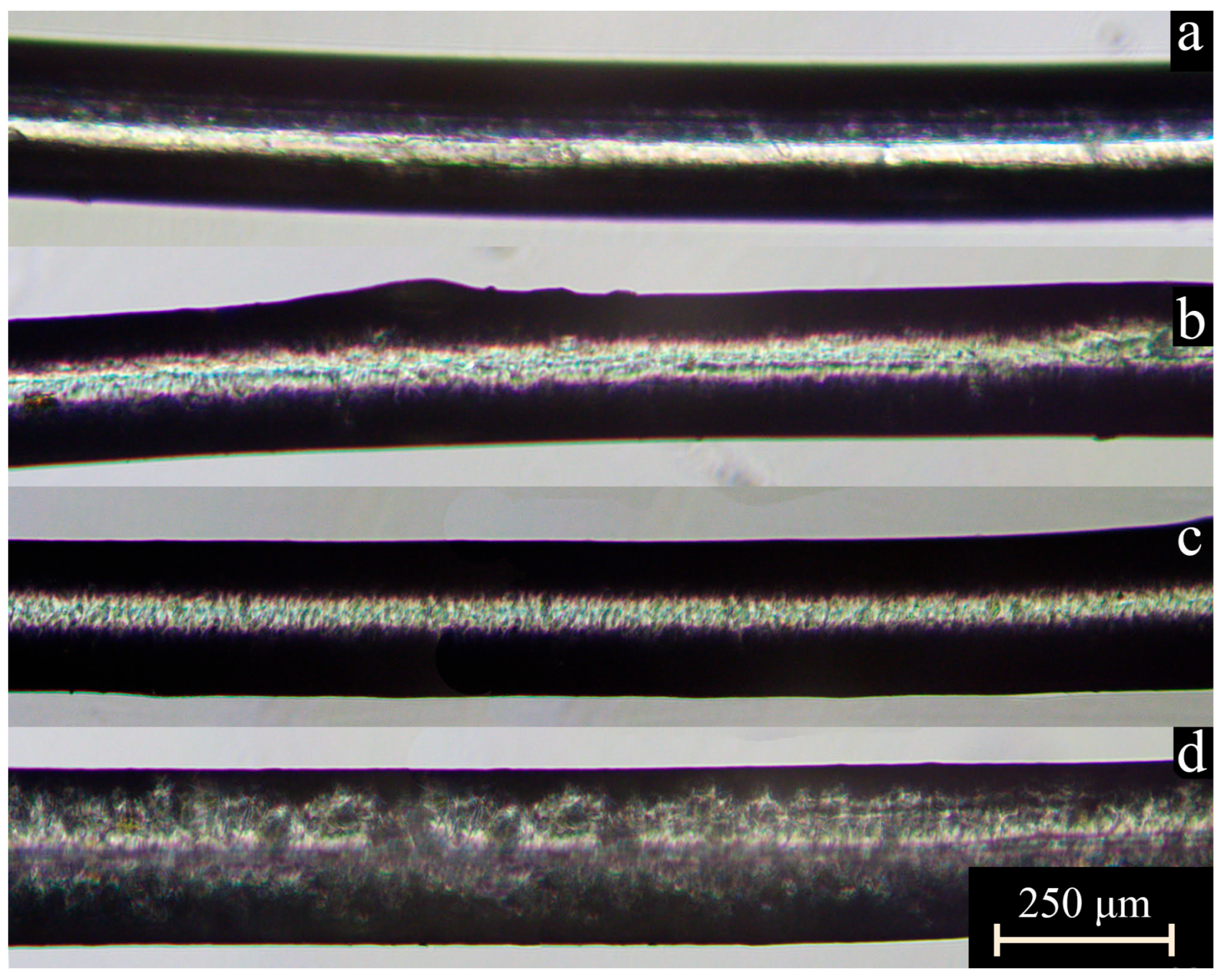

3.1. Morphology of the Melts

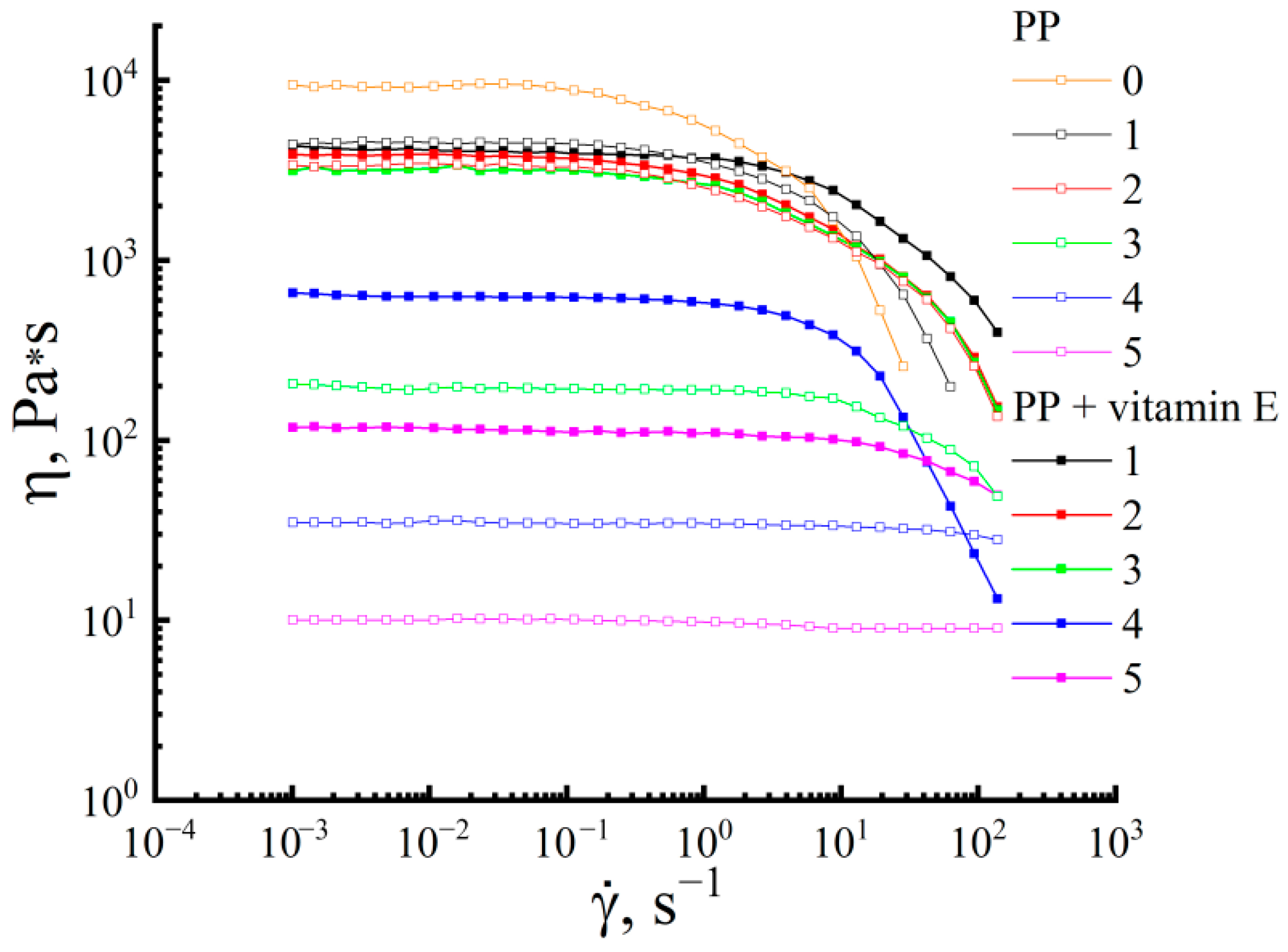

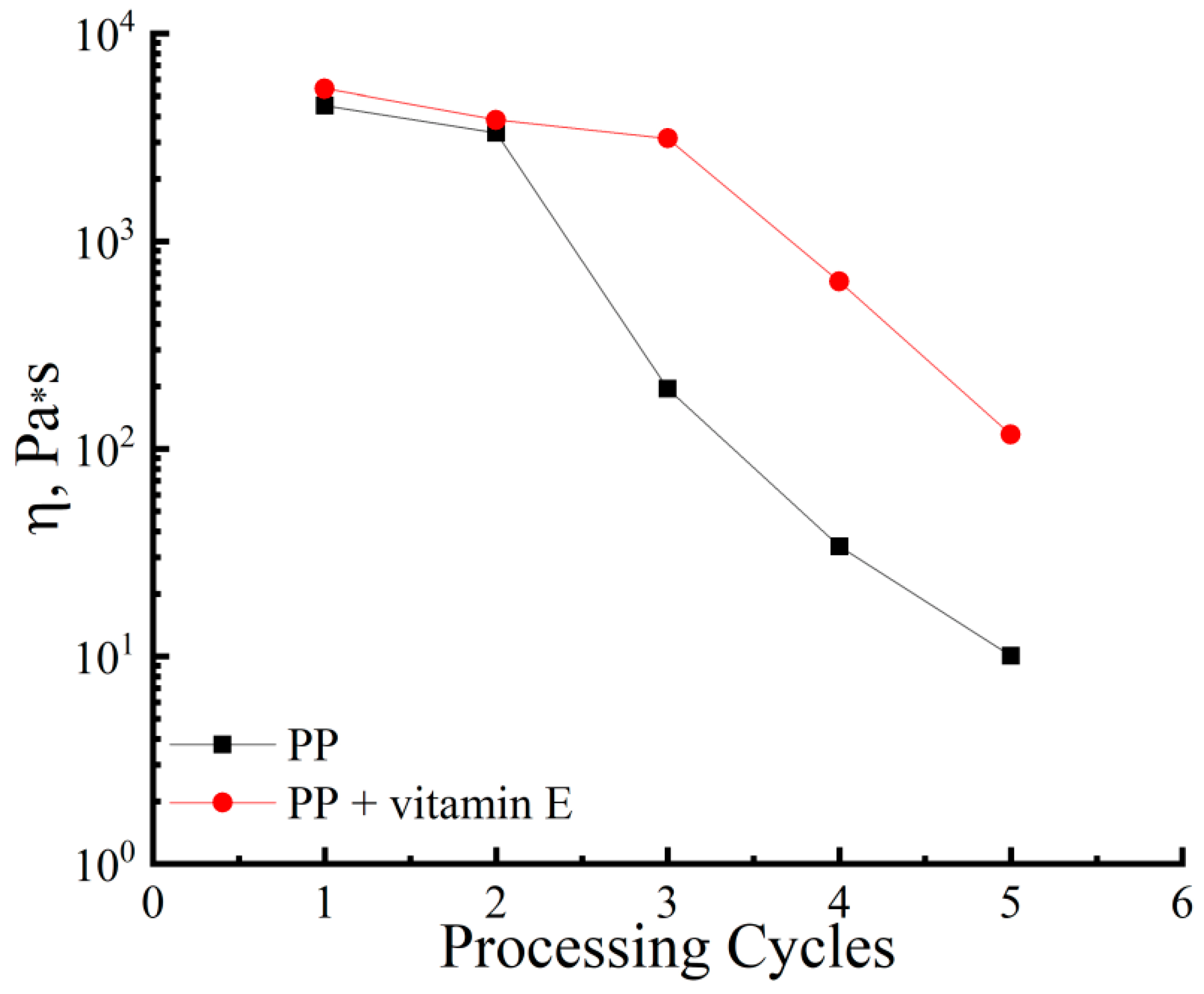

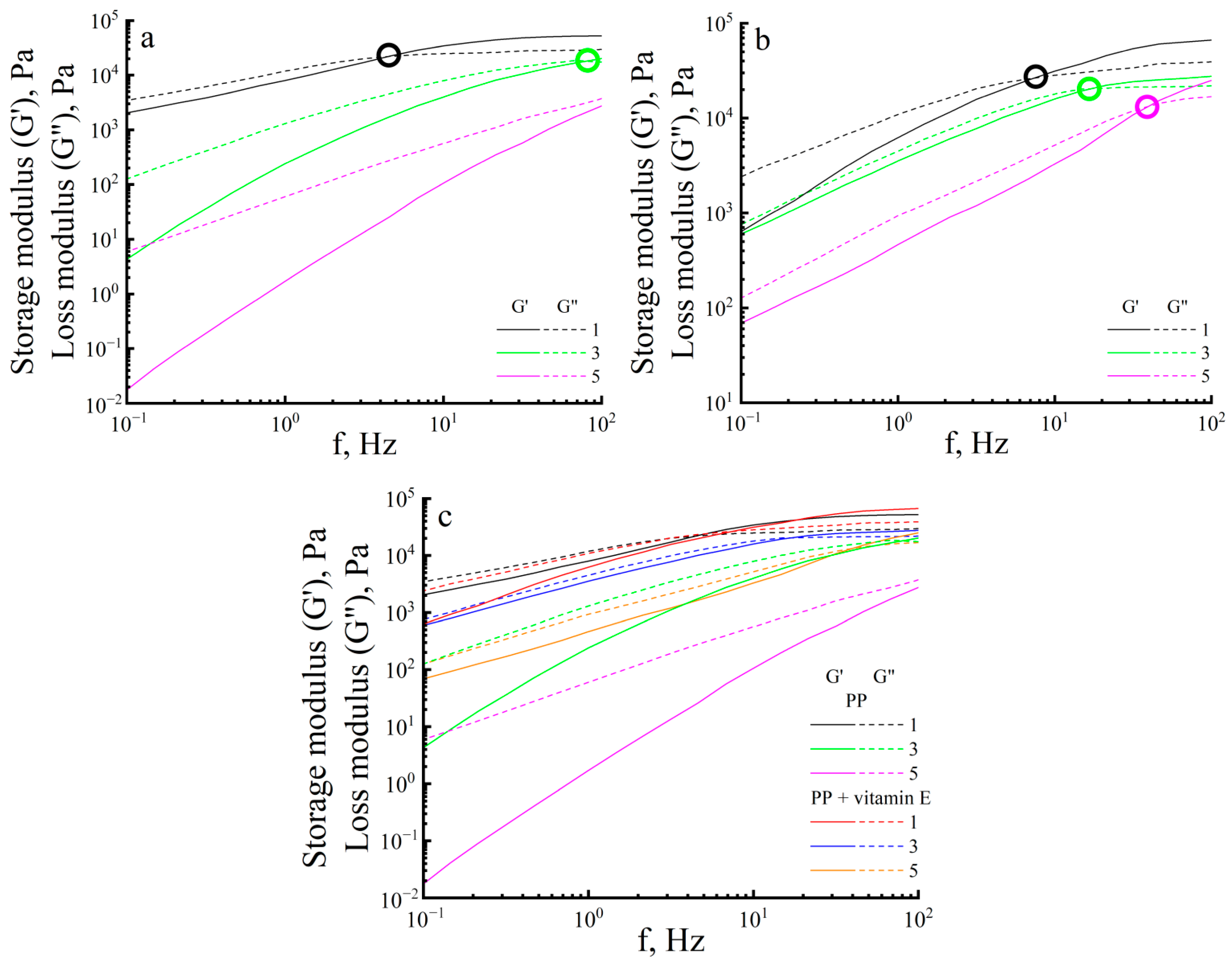

3.2. Rheological Properties

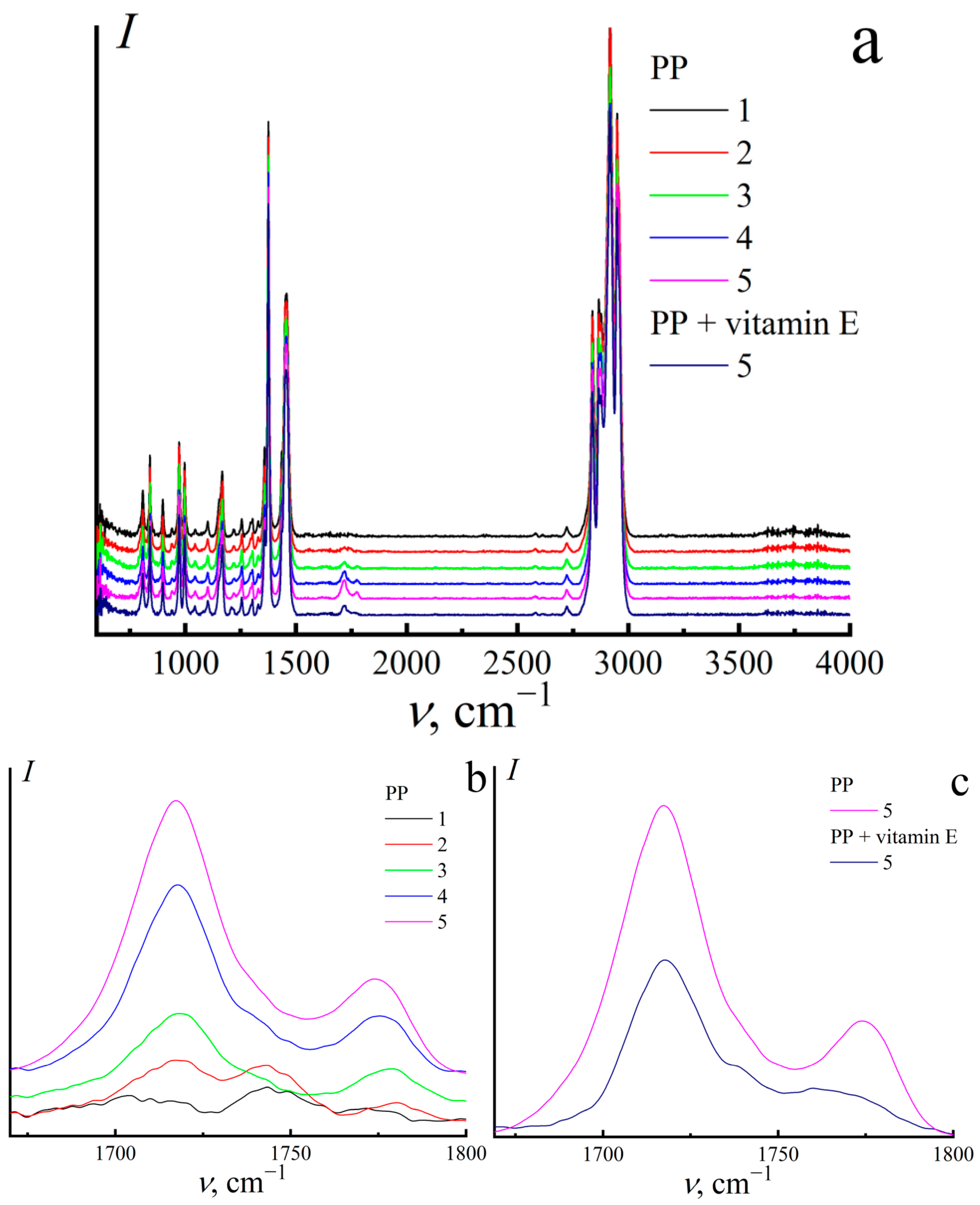

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

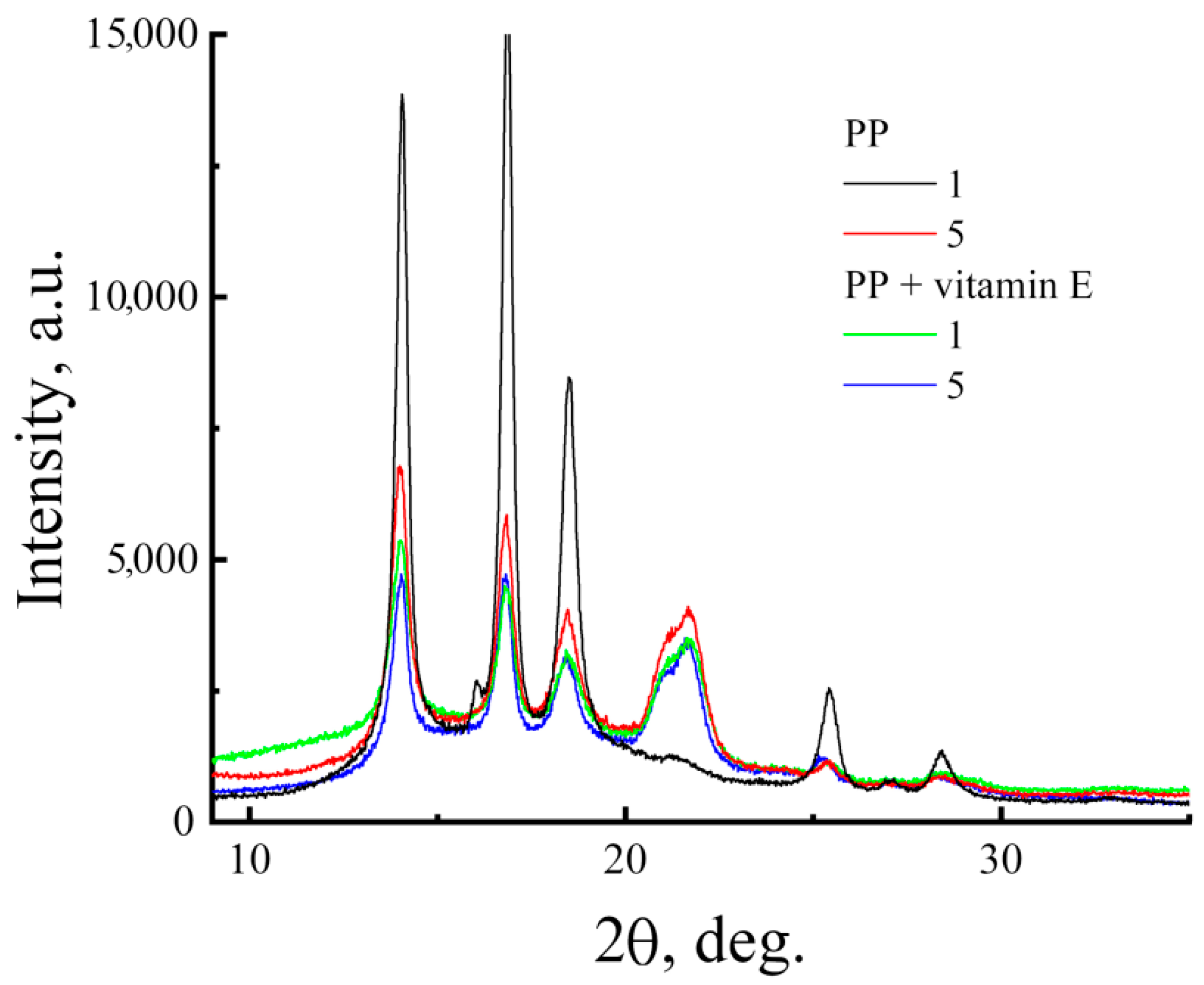

3.4. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

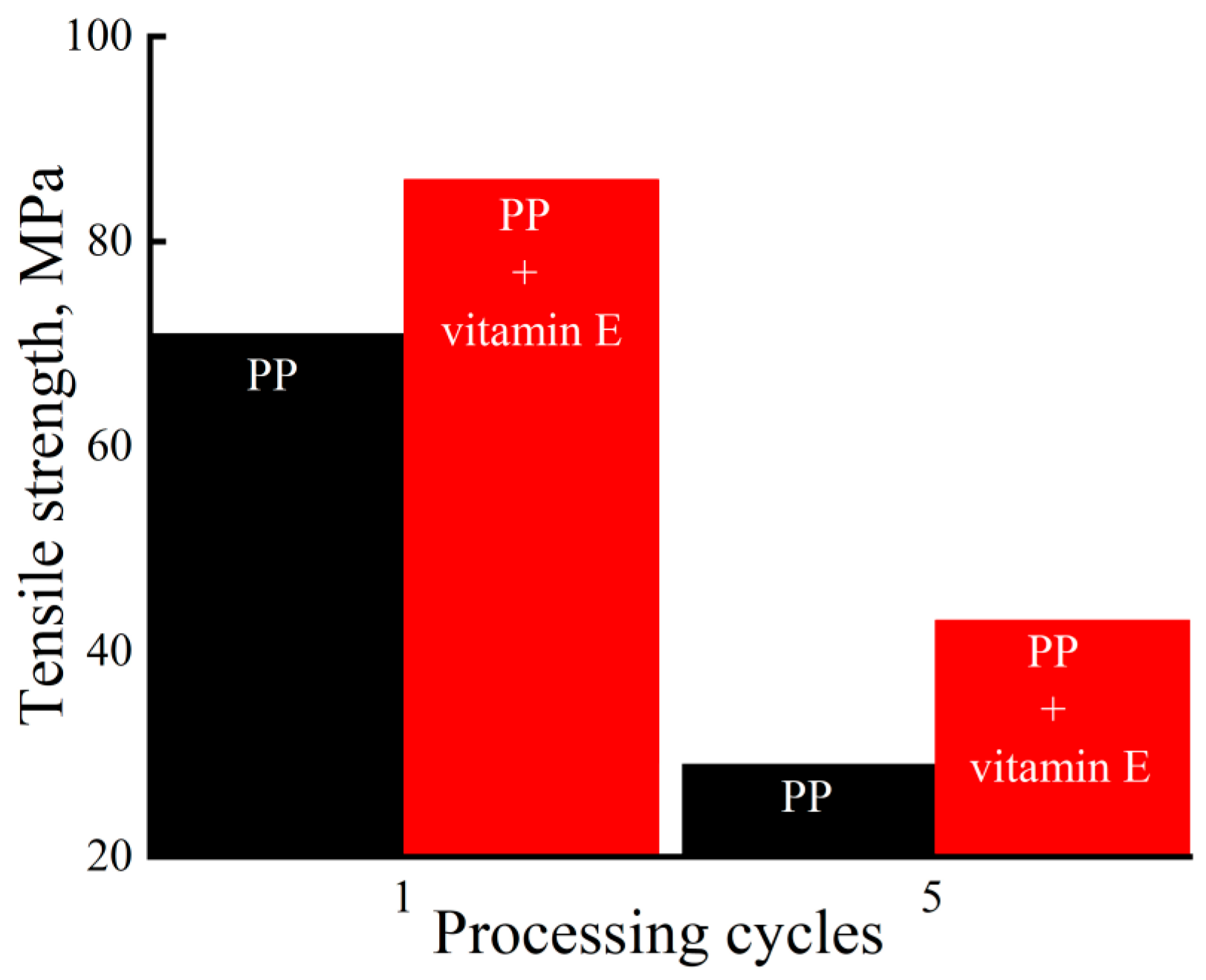

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barbhuiya, S.; Kanavaris, F.; Das, B.B.; Idrees, M. Decarbonising Cement and Concrete Production: Strategies, Challenges and Pathways for Sustainable Development. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GCCA (Global Cement and Concrete Association). Concrete Future. The GCCA 2050 Cement and Concrete Industry Roadmap for Net Zero Concrete. Available online: https://gccassociation.org/concretefuture/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Slate, F.O.; Hover, K.C. Microcracking in concrete. In Fracture Mechanics of Concrete: Material Characterization and Testing; Carpinteri, A., Ingraffea, A.R., Eds.; Engineering Application of Fracture Mechanics; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1984; Volume 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, H.R.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Synthetic fibers for cementitious composites: A critical and in-depth review of recent advances. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 207, 491–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiberti, G.; Minelli, F.; Plizzari, G.A.; Vecchio, F.J. Influence of concrete strength on crack development in SFRC members. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 45, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizenshtein, E.M.; Efremov, V.N. Production and use of polypropylene fibres and yarn. Fibre Chem. 2006, 38, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, E.; Myrhe, O.J.; Hinrichsen, E.L.; Grøstad, K. Effects of processing parameters and molecular weight distribution on the tensile properties of polypropylene fibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1994, 52, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajer, K.; Braun, U. Different aspects of the accelerated oxidation of polypropylene at increased pressure in an autoclave with regard to temperature, pretreatment and exposure media. Polym. Test. 2014, 37, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberian, M.; Tajaddini, A.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Sun, D.; Maqsood, T.; Roychand, R. Mechanical properties of polypropylene fibre reinforced recycled concrete aggregate for sustainable road base and subbase applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 405, 133352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazy, J.; Blazy, R. Polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete and its application in creating architectural forms of public spaces. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 14, e00549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedjazi, S.; Castillo, D. Utilizing Polypropylene Fiber in Sustainable Structural Concrete Mixtures. CivilEng 2022, 3, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.K.; Rahman, M.K.; Baluch, M.H. Influence of steel and polypropylene fibers on cracking due to heat of hydration in mass concrete structures. Struct. Concr. 2018, 20, 808–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, G.M.S.; Das, S. Evaluating plastic shrinkage and permeability of polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2016, 5, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangestuti, E.K.; Handayani, S.; Adila, H.; Primerio, P. The Effect of Polypropylene Fiber Addition to Mechanical Properties of Concrete. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 700, 012057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, M.R.; Biricik, Ö.; Aghabaglou, A.M. Effect of the addition of polypropylene fiber on concrete properties. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2022, 36, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lura, P.; Terrasi, G.P. Reduction of fire spalling in high-performance concrete by means of superabsorbent polymers and polypropylene fibers: Small scale fire tests of carbon fiber reinforced plastic-prestressed self-compacting concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 49, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soroushian, P.; Bayasi, Z. Concept of Fiber Reinforced Concrete. In Proceedings of the International Seminar on Fiber Reinforced Concrete, Madras, India, 16–19 December 1987; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Khairizal, Y.; Kurniawandy, A.; Kamaldi, A. Pengaruh Penambahan Serat Polypropylene Terhadap Sifat Mekanis Beton Normal. J. Online Mhs. Fak. Tek. Univ. Riau 2015, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sohaib, N.; Seemab, F.; Sana, G.; Mamoon, R. Using Polypropylene Fibers in Concrete to achieve Maximum Strength. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Advances in Civil and Structural Engineering–CSE, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 4 February 2018; pp. 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.P.; Rangan, B.V. Fiber reinforced concrete properties. ACI J. 1971, 68, 126–137. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, C.D. Fibre-Reinforced Cements and Concretes; Gordon and Breach Science Publishers: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2001; 372p. [Google Scholar]

- Turoboś, P.; Przybysz, P. Comparative Study of Cement Composites Reinforced with Cellulose and Lignocellulose Fibers. Fibers 2025, 13, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, J.A.; Thomas, B.S.; Hawileh, R.A. Use of Hemp, Kenaf and Bamboo Natural Fiber in Cement-Based Concrete. Int. Conf. Adv. Constr. Mater. Struct. 2022, 65, 2070–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Omran, A.; Tagnit-Hamou, A. Role of Homogenization and Surface Treatment of Flax Fiber on Performance of Cement-Based Composites. Clean. Mater. 2022, 3, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, T.; Chen, Y.; Yang, W.; Wang, J.; Jin, L. Preparation and Properties of Pretreated Jute Fiber Cement-Based Composites. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 210, 118090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, O.; Al-Dala’ien, R.N.; Arbili, M.M.; Alashker, Y. Optimizing Natural Fiber Content and Types for Enhanced Strength and Long-Term Durability in High-Performance Concrete. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2025, 26, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, I.S.; Golova, L.K.; Vinogradov, M.I.; Egorov, Y.E.; Kulichikhin, V.G.; Mikhailov, Y.M. New Hydrated Cellulose Fiber Based on Flax Cellulose. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2021, 91, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, I.S.; Golova, L.K.; Smyslov, A.G.; Vinogradov, M.I.; Palchikova, E.E.; Legkov, S.A. Flax Noils as a Source of Cellulose for the Production of Lyocell Fibers. Fibers 2022, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarov, I.S.; Shkurenko, S.A.; Shubin, R.B.; Palchikova, E.E.; Vinogradov, M.I.; Kulanchikov, Y.O.; Kulichikhin, V.G. Hemp-based lignocellulosic mass as a basis for producing textile fibers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 318, 145035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, T.P.; Le, T.H.M.; Ngan, N.V.C. An experimental evaluation of the performance of concrete 516 reinforced with recycled fibers made from waste plastic bottles. Results Eng. 2023, 18, 101205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, A.; Alam, B.; Iqbal, M.J.; Ahmed, W.; Shahzada, K.; Javed, M.H.; Khan, E.A. Impact of Length and Percent Dosage 507 of Recycled Steel Fibers on the Mechanical Properties of Concrete. Civil. Eng. J. 2021, 7, 1650–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleman, M.; Ahmad, N.; Khan, S.U.; Ahmad, T. Investigating Flexural Performance of Waste Tires Steel Fibers-Reinforced Cement-Treated Mixtures for Sustainable Composite Pavements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 15, 122099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, K.M.; Akbar, A. The Recent Progress of Recycled Steel Fiber Reinforced Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 232, 117232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu’ma, N.H.; Aziz, M.R. Flexural Performance of Composite Ultra-High-Performance Concrete-Encased Steel Hollow Beams. Civil. Eng. J. 2019, 5, 1289–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Addiego, F.; Bahlouli, N.; Ahzi, S.; Rémond, Y.; Toniazzo, V.; Muller, R. Analysis of thermomechanical reprocessing effects on polypropylene/ethylene octene copolymer blends. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 97, 1475–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Tuladhar, R.; Shi, F.; Shanks, R.A.; Combe, M.; Collister, T. Mechanical reprocessing of polyolefin waste: A review. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2015, 55, 2899–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmizadeh, E.; Tzoganakis, C.; Mekonnen, T.H. Degradation Behavior of Polypropylene during Reprocessing and Its Biocomposites: Thermal and Oxidative Degradation Kinetics. Polymers 2020, 12, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Malaika, S.; Issenhuth, S.; Burdick, D. The antioxidant role of vitamin E in polymers V. Separation of stereoisomers and characterization of other oxidation products of dl-α-tocopherol formed in polyolefins during melt processing. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2001, 73, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.S.; Edge, M.; Hussain, S. Perspectives on yellowing in the degradation of polymer materials: Inter-relationship of structure, mechanisms and modes of stabilisation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 201, 109977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Malaika, S.; Ashley, H.; Issenhuth, S. The antioxidant role of α-tocopherol in polymers. I. The nature of transformation products of α-tocopherol formed during melt processing of LDPE. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 1994, 32, 3099–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Malaika, S.; Issenhuth, S. The antioxidant role of α-tocopherol in polymers III. Nature of transformation products during polyolefins extrusion. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1999, 65, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Malaika, S.; Goodwin, C.; Issenhuth, S.; Burdick, D. The antioxidant role of α-tocopherol in polymers II. Melt stabilising effect in polypropylene. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1999, 64, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, K.; Nemeth, M.A.; Renkecz, T.; Tatraaljai, D.; Pukanszky, B. Stabilization of PE with the natural antioxidant t-resveratrol: Interaction of the primary and the secondary antioxidant. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2024, 230, 111046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, H.P.; Frenzel, R. Solubility of additives in polypropylene. Eur. Polym. J. 1980, 16, 647–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Fang, W.; Fan, J. Determination of Antioxidant Irganox 1010 in Polypropylene by Infrared Spectrometry. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 514, 052046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birol, T.; Avcıalp, A. Impact of Macro-Polypropylene Fiber on the Mechanical Properties of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete. Polymers 2025, 17, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutsos, M.N.; Le, T.T.; Lampropoulos, A.P. Flexural performance of fibre reinforced concrete made with steel and synthetic fibres. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 36, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guneyisi, E.; Gesoglu, M.; Mohamadameen, A.; Alzeebaree, R.; Algin, Z.; Mermerdas, K. Enhancement of shrinkage behavior of lightweight aggregate concretes by shrinkage reducing admixture and fiber reinforcement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 54, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelisser, F.; Neto, A.B.D.S.; La Rovere, H.L.; Pinto, R.C.D. Effect of the addition of synthetic fibers to concrete thin slabs on plastic shrinkage cracking. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 2171–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.; Begum, R.; Alam, M.M. Mechanical properties of synthetic fibers reinforced mortars. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2013, 4, 923–927. [Google Scholar]

- Karaoui, M.; Fiore, V.; Elhamri, Z.; Kharchouf, S.; Alami, M.; Assouag, M. Study of the Physico-Chemical Properties of Injection-Molded Polypropylene Reinforced with Spent Coffee Grounds. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zefirov, V.V.; Elmanovich, I.V.; Stakhanov, A.I.; Pavlov, A.A.; Stakhanova, S.V.; Kharitonova, E.P.; Gallyamov, M.O. A New Look at the Chemical Recycling of Polypropylene: Thermal Oxidative Destruction in Aqueous Oxygen-Enriched Medium. Polymers 2022, 14, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicker, C.; Rudolph, N.; Kühnert, I.; Aumnate, C. The use of rheological behavior to monitor the processing and service life properties of recycled polypropylene. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 19, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Cayla, A.; Salaün, F.; Devaux, E.; Liu, P.; Huang, T. A green method to fabricate porous polypropylene fibers: Development toward textile products and mechanical evaluation. Text. Res. J. 2019, 90, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besco, S.; Bosio, A.; Brisotto, M.; Depero, L.E.; Lorenzetti, A.; Bontempi, E.; Bonora, R.; Modesti, M. Structural and Mechanical Characterization of Sustainable Composites Based on Recycled and Stabilized Fly Ash. Materials 2014, 7, 5920–5933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richaud, E.; Fayolle, B.; Davies, P. Handbook of Properties of Textile and Technical Fibres, 2nd ed.; The Textile Institute Book Series; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 515–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobasher, B.; Dey, V.; Bauchmoyer, J.; Mehere, H.; Schaef, S. Reinforcing Efficiency of Micro and Macro Continuous Polypropylene Fibers in Cementitious Composites. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shambilova, G.; Korshunov, A.; Vinogradov, M.; Kadasheva, Z.; Iskakov, R.; Kalauova, A.; Makarov, G.; Kalimanova, D.; Legkov, S. Recycling of Polypropylene with Vitamin E Additives: Rheological Properties and Mechanical Characteristics. Processes 2025, 13, 3923. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123923

Shambilova G, Korshunov A, Vinogradov M, Kadasheva Z, Iskakov R, Kalauova A, Makarov G, Kalimanova D, Legkov S. Recycling of Polypropylene with Vitamin E Additives: Rheological Properties and Mechanical Characteristics. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3923. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123923

Chicago/Turabian StyleShambilova, Gulbarshin, Alexander Korshunov, Markel Vinogradov, Zhanar Kadasheva, Rinat Iskakov, Altynay Kalauova, Georgy Makarov, Danagul Kalimanova, and Sergey Legkov. 2025. "Recycling of Polypropylene with Vitamin E Additives: Rheological Properties and Mechanical Characteristics" Processes 13, no. 12: 3923. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123923

APA StyleShambilova, G., Korshunov, A., Vinogradov, M., Kadasheva, Z., Iskakov, R., Kalauova, A., Makarov, G., Kalimanova, D., & Legkov, S. (2025). Recycling of Polypropylene with Vitamin E Additives: Rheological Properties and Mechanical Characteristics. Processes, 13(12), 3923. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123923