Abstract

Biomass is commonly used for cooking in developing countries, but traditional cookstoves emit pollutants (CO, NOx, PM), which harm indoor air quality. Improvements and solutions are essential for achieving Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG 7). This study assesses the impact of the combustion chamber design, the combustion-air/gasification-air ratio (CA/GA = 2.8, 3.0, and 3.2), and the start type of water boiling test (WBT) protocol (cold and hot starts) on the chemical and morphological characteristics of the total suspended particulate matter (TSPM) emitted from a biomass gasification-based cookstove using densified biomass as feedstock. TSPM was characterized using Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Raman Spectroscopy, and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) to evaluate their chemical composition and morphological features under the above operational conditions. Under the modified WBT protocol, the cookstove achieved CO levels ranging from 1.52 to 2.13 g/MJd, and efficiency between 26.56% and 27.81%. TSPM emissions ranged between ~74 and 122.70 mg/MJd. The chemical characteristics of TSPM surface functional groups weren’t affected by the start condition, except for decreased intensities as CA/GA increased, promoting oxidation and removal as CO/CO2. While cold start produced TSPM with higher structural order at higher CA/GA levels, no significant differences were observed among samples from both start conditions at CA/GA ≥ 3.0, indicating chemical and structural similarity. Morphology and particle size were mainly unaffected, with only slight increases in particle size during hot start due to higher biomass-to-air ratios.

1. Introduction

Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7) from the United Nations, also known as “Affordable and Clean Energy”, aims to ensure affordable, clean, modern, reliable, and sustainable energy for all. Therefore, clean energy for cooking aligns with this objective because it positively impacts people’s well-being and health and the environment [1]. Nevertheless, according to the Tracking SDG7 report published in 2025, it is concluded that by 2030, the goal of achieving universal access to clean fuels and technologies for the total world population will not be reached. The report highlights that by 2023, the population that used firewood, charcoal, and crop and animal waste to cook and heat their homes was ~2.1 billion people, while by 2030, this population will be reduced to only 1.8 billion [2]. Consequently, the development and implementation of clean and affordable cooking technologies, such as gasification-based biomass cookstoves, must be reinforced to ensure access to improved biomass cookstoves [3,4,5]. The improved cookstoves mitigate the environmental, social, and health impacts caused by indoor air pollution in homes that use biomass in traditional open fires for cooking [3,4].

Currently, approximately 1.57 million households in Colombia, mostly in rural and non-urban areas, use firewood for cooking [6]. As a result, the Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) and the Mining-Energy Planning Unit (UPME) launched a national program to replace firewood in household cooking [7]. This program aims to ensure that by 2026, 11.6% of households that cook with firewood will switch to clean fuels, by 2030, 39.3% will have made the transition, and by 2050, the entire Colombian population will use clean fuels. Conversely, firewood consumption in Colombia increased by 5.1% from 2020 to 2021 due to higher costs of propane gas and electricity [6]. Despite new policies promoting renewable energy, firewood continues to dominate cooking in Colombia’s rural and remote areas.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), people in low- and middle-income countries are more exposed to air pollution levels that exceed recommended limits [8]. The primary pollutant emissions produced during solid fuel combustion are carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and particulate matter (PM), which are favored under conditions of incomplete combustion [9]. Exposure to indoor air pollutant emissions can cause adverse health effects, such as eye conditions, respiratory diseases, and cancer, leading to burns, poisoning, musculoskeletal injuries, and death [8]. Globally, ~3.2 million premature deaths were reported in 2020, mainly in low and middle-income countries [10]. In Latin America, the number of deaths caused by using solid fuels for cooking rose to 82,000 [11], while in Colombia, by 2019, the number of reported deaths due to indoor air pollution was nearly 5000 [11].

Inefficient cookstoves can harm health and the environment due to PM production when cooking with wood biomass [12,13,14]. Smaller PM (<2.5 µm) can reach people’s lungs and drastically impact their health. Furthermore, PM’s composition absorbs solar radiation in the atmosphere, altering the radiative properties of clouds, influencing atmospheric chemistry, and contributing to the greenhouse effect [15,16]. Consequently, it is essential to propose and adopt policies and practices that promote cleaner cooking, including environmentally friendly and energy-sustainable cooking technologies and facilities [5,13]. Compared to traditional three-stone cookstoves, the improved cookstoves have higher thermal efficiency, lower polluting emissions, and lower fuel consumption, reducing harmful impacts on people’s health, ecosystems, and the climate [3,4].

Specific PM emissions and their composition are affected by the biomass type used as fuel, the combustion conditions, and the cookstove design [5,16]. Therefore, it is crucial to assess emissions and efficiency under various operating and design conditions [15,17,18,19] and conduct chemical and morphological analyses of the generated PM. It is worth noting that the gasification-based biomass cookstoves used here are forced-draft and comprise two stages: the biomass gasifier stage and the combustion chamber located on top of the stove where the producer gas coming from gasification is burned [20]. Forced-draft in gasification-based biomass cookstoves has resulted in PM emission reductions ranging between 21 and 57% [21] due to improved mixing between secondary air and producer gas (tars) [20,22]. Nevertheless, the chemical and morphological characterization of the PM derived from these cookstoves is scarce.

García et al. [23] reported that most studies on PM emitted from biomass cookstoves mainly focused on mass concentration. Therefore, it is crucial to assess the physicochemical properties of PM (beyond particle number concentration, particle size distribution, and carbon fraction and organic and elemental carbon composition), and determine their relationship with cookstove design and fuel type. Similarly, Kuye and Kumar [24], in a review of the physicochemical characteristics of ultrafine particles emitted by domestic combustion of solid fuels, emphasized the limited information available on the physicochemical properties of particulate matter from improved cookstoves. Lindgren et al. [25] evaluated emissions from four types of cookstoves (three-stone stove, rocket stove, natural and forced draft gasification stoves), where the design and combustion zone of the stove, along with the fuel properties, influence the total emissions and the physicochemical characteristics of PM, such as polycyclic aromatic compounds (PAHs), organic and elemental carbon, and inorganic components. Valencia et al. [26] assessed the emissions of pollutants and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from a gasification-based biomass cookstove compared to a three-stone stove. The gasification cookstove reduced CO and total suspended particulate matter (TSPM) by 85% and 89%, respectively. PAHs decreased by over 41% in the gaseous phase and by 98% in particulate matter. Additionally, SEM micrographs of TSPM revealed chain-like agglomerates and separate spheres with a higher fixed carbon content (66%) from the gasification cookstove, in contrast to the amorphous tar-like material found in the 3SF stove, which had a higher volatile matter content (64%). This difference is likely due to the lower oxidation efficiency in the traditional stove.

On the other hand, Champion et al. [27] assessed the mutagenicity of extractable organic material and PM by applying them on Salmonella plates for three gasification-based stoves (Mimi Moto, Xunda, and Philips HD4012). The Xunda stove had the highest mutagenicity; the authors also observed that improved cookstoves significantly decrease pollutant emissions compared to traditional stoves. However, proper ventilation is essential for maintaining acceptable indoor air quality. Shen et al. [28], by examining the morphology of PM from ten different cookstoves, using High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HR-TEM), discovered that the aggregates consist of hemispherical primary particles with an internal lamellar structure. The primary particles ranged in size from 5 nm to 50 nm. Compared to SEM analyses, TEM provides a more detailed view of individual particle morphology [23].

This manuscript advances the field of biomass pretreatment, with a specific focus on densified wood biomass (pellets). Our previous work demonstrated that using pellets resulted in improved performance, with approximately 5% higher thermal efficiency and 21% lower specific energy consumption compared to wood chips [20]. These optimized pellets were later used by Muñoz et al. [17] to further analyze the airflow optimization on efficiency and NOx reduction. This background supports the selection of pelletized biomass as the best fuel for the physicochemical and morphological analysis of the emitted TSPM, exploring how the CA/GA ratio and the start type of the water boiling test influence the chemical structure and particle size. Therefore, the identified research gap is the lack of detailed physicochemical characterization of particulate matter, particularly from forced-draft gasification biomass cookstoves [29,30]. The primary contribution and novelty of this work is the chemical and morphological analysis of TSPM using advanced techniques, including Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), Raman Spectroscopy, and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [11,31]. Here, we connect macroscopic operating conditions (CA/GA ratio and start type) to the microscopic properties and formation of particulate matter [11].

2. Materials and Methods

This research assessed the effect of three controllable parameters on the energy and environmental performance of a gasification-based biomass cookstove, as well as on the chemical and morphological characteristics of the TSPM collected. The three analyzed parameters were: (a) two designs of the producer gas combustion chamber (CCG1 and CCG2); (b) the volumetric combustion-air/gasification-air (CA/GA) ratio evaluated at 2.8, 3.0, and 3.2. Finally, (c) the start type (cold -CS- and hot -HS-) of a modified water boiling test protocol (WBT 4.2.3). The experiments used patula pine pellets (WP) as biomass feedstock. The properties of biomass pellets used as fuel are summarized in Table 1. The CA/GA ratios of 2.8, 3.0, and 3.2 were investigated to extend the research presented by Gutiérrez et al. [20], focusing on the physicochemical and morphological characterization of TSPM.

Table 1.

Properties of Patula pine pellets used as fuel.

Combining the levels of each experimental factor and performing each experiment in duplicate, an experimental campaign consisting of 24 tests was conducted using the improved biomass cookstove. The experiments were conducted in duplicate to ensure statistical reliability, reproducibility, and accuracy of the results. The experimental statistical design was analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), aiming to determine which experimental factors statistically influence the outcome variables studied here. The answer variables assessed were the cookstove thermal efficiency (η, %), the specific emissions of CO (CO, g/MJd), and TSPM (mg/MJd). The detailed chemical and morphological characterization of the TSPM is described in Section 2.2.

2.1. Experimental Setup

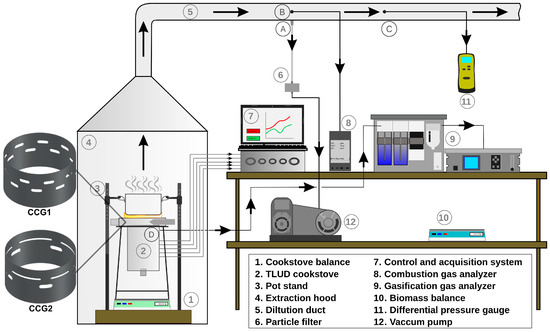

Figure 1 illustrates the experimental setup of a forced-draft gasification-based biomass cookstove, which is used to evaluate the thermodynamic performance of the gasification process and the cookstove and chemically and morphologically characterize the TSPM collected on filters. The gasification-based cookstove operating under the WBT protocol features a control and data acquisition system that allows for varying the CA/GA ratios and recording the temperature field along the gasification bed wall, as well as the mass of biomass consumed in each test [20].

Figure 1.

Experimental setup of the forced draft gasification-based biomass cookstove. Sampling points: (A) TSPM, (B) Fume temperature and CO emissions, (C) Flow fume velocity, and (D) Producer gas composition.

A KIGAZ 310 equipment (KIMO® Instruments, Montpellier, France) was used to measure the concentration of pollutant species from the combustion gases stream. The CO concentration was measured by ECD (±10 ppm), CO2 concentration was calculated, and the temperature of the combustion gases stream was measured by a K-type thermocouple (±1.1 °C). The amount of TSPM was measured gravimetrically, collecting the TSPM onto 47 mm diameter fiberglass filters (Advantec GC-50, Tokyo, Japan). The gaseous stream with TSPM was sucked by a vacuum pump with a volumetric flow capacity of 24 L/min ± 0.5 L/min. The fiberglass filter conditioning was carried out for 24 h at a relative humidity of 40% ± 5% and a temperature of 20 °C ± 3 °C.

The measured and calculated parameters to characterize the gasification process were the maximum process temperature (Tmax, °C) measured near the reactor wall, the fuel/air equivalence ratio (Frg, dimensionless), the biomass consumption rate (bms, kg/h/m2), the composition (vol%) and low heating value (LHVpg, kJ/Nm3) of the producer gas. Tmax (°C) was measured by thermocouples installed throughout the reactor, bms was calculated following the approach proposed by Gutiérrez et al. [20]. In contrast, Frg and LHVpg were calculated according to the methodology proposed by Díez et al. [35]. The producer gas composition was measured by a Gasboard-3100 Serial gas analyzer (Cubic-Ruiyi Instrument, Wuhan, PR China), the device measures CO (±2% vol del FS), CO2 (±2% vol of full scale), CH4 (±2% vol of full scale), H2 (±3% vol of full scale), O2 (±3% vol of full scale), C3H8 (±2% vol of full scale), and N2 (calculated by difference).

The improved cookstove’s energy and environmental performance were obtained by calculating the thermal efficiency (η) and specific CO and TSPM emissions, respectively. Equation (1) relates the energy delivered to water and the energy supplied by the biomass [20].

where Ew,t = total energy supplied to water (J); and Es,bms = energy supplied by the biomass to boil and evaporate the water (J). On the other hand, the CO specific emission (g/MJd) relates the amount of CO released to the energy delivered to water: this emission factor was calculated through Equation (2).

where the mass of CO (mCO), was determined using both the mass balance and the measured gas concentration; and Ew,t Sj = total energy supplied to water in each of the start types (J) during the stages 1 and 2, respectively. The TSPM emission was determined through Equation (3) by measuring the TSPM mass (mTSPM) collected on the filter and the total energy delivered to water.

where duct is the total volumetric flow that flows through the main duct during the test (m3/s) and vacuum pump is the vacuum pump volumetric flow (m3/s).

A multifactorial statistical experimental design was adopted, considering three experimental factors, Equation (4) [36]. The factors and their levels consider the combustion chamber design (2 levels, CCG1 and CCG2), the CA/GA ratio (3 levels, 2.8, 3.0, and 3.2), and the start type of the modified WBT (2 levels, CS and HS). The answer variables of the gasification-based cookstove analyzed were η (%), CO (g/MJd), and TSPM (mg/MJd).

where µ is the overall mean; τi is the effect of factor A; βj is the effect of factor B; γk is the effect of factor C; (τβ)ij, (τγ)ik and (βγ)jk are the interactions between each pair of factors; (τβγ)ijk correspond to the interactions among three factors, and εijkl is the error [36].

2.2. Physicochemical Characterization of Tspm from a Gasification-Based Biomass Cookstove

TSPM from the gasification-based biomass cookstove was collected in the dilution duct using brand fiberglass filters with a diameter of 47 mm and a vacuum pump with a volumetric capacity of 24.0 ± 0.5 L/min. TSPM was characterized by different analytical techniques to obtain information on possible differences in the physicochemical characteristics associated with the tested variables. FTIR was used to detect differences in the surface chemical composition of TSPM by analyzing changes in the signals of the various functional groups. For each sample, a 1% KBr pellet of TSPM was prepared, and the IR spectrum was recorded using a Nicolet 6700 infrared spectrometer from Thermo Scientific Electron Corporation, Madison, WI, USA. Equipped with a transmission cell and an MCT detector cooled to −77 K with liquid nitrogen [37]. The wavenumber range used to record all the spectra was 800–4000 cm−1, the appropriate number of scans to improve the signal-to-noise ratio was 32, and the resolution was set to 4 cm−1. To complement the information on the chemical nature of the TSPM surface obtained by FTIR, the samples were also characterized by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) using a Thermo Fisher Scientific spectrometer (Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with an Al Kα X-ray source, operated at 20 kV and a current of 20 mA, for high-resolution spectral analysis [38,39]. All the binding energies were calibrated with the C1s binding energy fixed at 284.6 eV as an internal reference [40,41].

Raman spectroscopy was used to obtain information on the chemical composition associated with the carbonaceous network of TSPM and determine the degree of structural order/disorder in the materials. No additional sample preparation was required for this analysis. In this case, the filter with the collected sample was placed directly on the sample holder of the LabRam HR Horiba microscope system from HORIBA Scientific, Irvine, CA, USA, equipped with a 632.8 nm He/Ne laser excitation source of 17 mW. Four different spots were analyzed in a spectral range of 800–2000 cm−1 for each sample using a 50× magnification objective. The power source and exposure time were reduced to 0.17 mW and 20 s, respectively, to avoid sample burn-off. The spectra obtained were decomposed and fitted to four leading bands associated with the ordered graphitic band (G) and three structural disorder bands (D1, D3, and D4) [37]. The standard deviation of the Raman parameters evaluated in this study, associated with graphitic and amorphous content (AD1/AG and AD3/AG), was approximately 9.6% of the mean.

TEM and HRTEM analyses were performed on a JEOL JEM-2100 electron microscope (Tokyo, Japan) operating at 200 kV to obtain images for assessing particle morphology, the mean primary particle diameter (dpp), and the inner structure. Before TEM analysis, a portion of TSPM was removed from the filter through sonication with 2 mL of ethanol. Then, a drop of the suspended particles was deposited onto copper-coated TEM grids using a micropipette, which was further dried in a glass Petri dish [37,42,43,44]. To determine the mean particle diameter (dpp), particles with distinguishable boundaries were randomly selected and analyzed using the image processing software ImageJ® , version 1.54p, 2025 [37].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Gasification Process Inside the Improved Cookstove

The volume between the grate and the bottom section of the combustion chamber constitutes the bed of the gasification-based cookstove. This configuration represents an atmospheric reverse-downdraft gasifier; the gasification air (GA) flow supplied to the reactor for testing the improved cookstove under WBT was 0.12 kg/m2/s ± 2.98%. Table 2 shows the results of the thermodynamic parameters that characterize the gasification process in the reverse-downdraft reactor. The reported values correspond to the average data calculated for each test of the experimental design, i.e., 12 tests (six experiments and six replicates) under cold start and 12 tests under hot start.

Table 2.

Gasification process parameters as a function of the WBT start type (CS and HS).

Tmax reached under cold start (404 °C) was 7% higher than that of hot start (378 °C). The lowest gasification temperature, observed for the hot start, was attributed to the high biomass consumption achieved in this regime, which resulted in an increase in the biomass-to-air equivalence ratio by 18% due to the preheating condition of the cookstove for this start mode (Table 2). The preheated cookstove facilitates the drying of fresh biomass; therefore, the energy required for processing the biomass is reduced [20].

LHVpg under hot start was 16.7% higher than that of cold start, with values of 3.3 kJ/Nm3 and 2.8 kJ/Nm3, respectively. The higher energy content of the producer gas under hot start is ascribed to the higher concentration of fuel species in the producer gas (CO, CH4, and C3H8), whose production was favored by the higher biomass-to-air equivalence ratio (Frg) (Table 2).

3.2. Efficiency and Emissions (Co and TSPM) from the Gasification-Based Cookstove

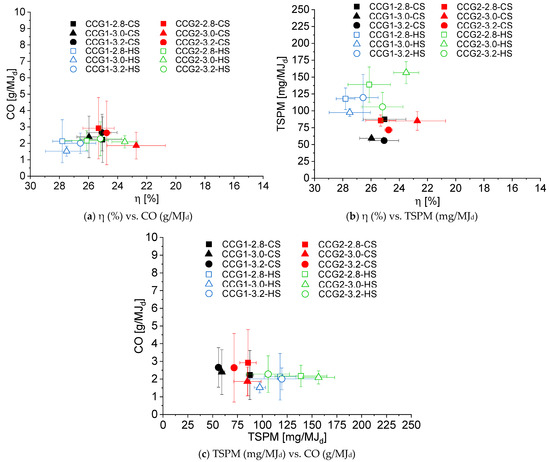

Figure 2 shows the relation between thermal efficiency and specific emissions of CO and TSPM from the improved biomass cookstove under the modified WBT protocol. The answer variables have been studied as a function of the experimental factors, such as combustion chamber design, CA/GA ratio, and start type of WBT. Figure 3 illustrates the statistical significance using a Pareto chart with a 95% confidence level for each analyzed answer variable (η, CO, and TSPM). The experimental factor CA/GA did not statistically affect any answer variables assessed here (Figure 3). This result was attributed to the slight variations in the CA/GA ratio (2.8, 3.0, and 3.2) tested, as well as to the constant flow rate of the gasification air during the experimental campaign (GA = 146 L/min). Therefore, the flow rate and flow conditions of CA are similar for the experimental plan; consequently, the variation of η, CO, and TSPM as a function of CA/GA was not significant due to the mild variation observed in these parameters.

Figure 2.

Relationship between the energy and environmental parameters of the gasification-based biomass cookstove as a function of experimental factors and levels: CCG (CCG1 and CCG2), CA/GA ratio (2.8, 3.0, and 3.2), and start type under the WBT protocol (CS and HS).

Figure 3.

Pareto chart: effect of CCG, CA/GA ratio, and start type on η and specific emissions of CO and TSPM from the gasification-based biomass cookstove.

Figure 2a shows that the improved cookstove with the CCG1 design achieved a better correlation between efficiency and CO emissions (g/MJd) at hot start, with efficiency values ranging from 26.6% to 27.8%, and CO emissions ranging from 1.5 to 2.1 g/MJd. The highest η reached under hot start resulted from the higher LHVpg, which increased by 16.7% compared to the cold start. As LHVpg increases, the available energy in the producer gas to be transferred to the pot also increases. Comparing the start type, it is worth noting that the gasification-based cookstove is not preheated during the cold start, resulting in wasted energy in the gasifier wall rather than being transferred to the pot with water. This heat transfer to the surroundings leads to a decrease in cookstove efficiency under cold start conditions compared to hot start conditions because the initial temperature of the improved cookstove is higher than the ambient temperature (preheated) [16].

The experimental factors, CCG and start type of the WBT protocol, have a statistically significant effect on the thermal efficiency of the improved cookstove. The combustion chamber (CCG) design has the greatest statistical significance on η (Figure 3). The average efficiency of the gasification-based cookstove with CCG1 was 25.36% under cold start, while at hot start, it was 27.29% (Figure 2a). Regarding the use of CCG2, the efficiency of the cookstove was 24.26% and 24.94% for cold start and hot start, respectively. Therefore, the cookstove thermal efficiency using CCG1 was 5% and 9.4% higher than that reached with CCG2, under cold and hot starts, respectively. This performance is attributed to higher velocities of the combustion air, which promote a more effective mixing process between the producer gas and the secondary air (CA) [20]. Therefore, the combustion efficiency improves [45], and the cookstove’s thermal efficiency increases [16].

According to the Pareto chart shown in Figure 3, the pollutant emissions of CO were not significantly affected by the experimental factors assessed here; nevertheless, Figure 2a shows some trends of this parameter as a function of the CCG and the start type. Concerning CCG, the average CO emissions were 2.16 g/MJd with CCG1 and 2.33 g/MJd using CCG2 (CO emissions were ~8% higher for CCG2). The improved mixing between the producer gas and combustion air in CCG1 contributed to reducing CO emissions. A homogeneous mixture of the gaseous fuel and secondary air avoids zones with low temperatures [15] and promotes more complete combustion of volatiles [14].

According to the modified WBT protocol’s start type, CO emissions were 20.7% lower in the hot start compared to the cold start. This behavior was attributed to the high LHVpg achieved under hot start, which increases the producer gas’s combustion temperature, thereby activating the oxidation of gaseous fuels such as CO [16].

Regarding the plot between η and TSPM shown in Figure 2b, it is worth noting that lower particle emissions were achieved under cold start conditions for both combustion chambers. The average TSPM emission at cold start was 74.11 mg/MJd; at hot start, it was 122.70 mg/MJd, representing an increment of ~66%. The high TSPM emissions under hot start are attributed to a high formation of tars, which promotes TSPM formation. Tars are produced due to the high biomass-to-air equivalence ratio reached at hot start, as well as other factors, such as the tar cracked by chemically activated carbon, which alters the composition of the producer gas and leads to the formation of soot during pyrolysis [16].

The start type is the only factor with a statistically significant effect on the TSPM emissions (Figure 3). Nonetheless, Figure 2b shows some variations in TSPM as a function of the combustion chamber design. By using CCG1, the TSPM emissions reached values between 55.86 mg/MJd and 119.58 mg/MJd; while for CCG2, the TSPM ranged from 71.60 mg/MJd to 156.57 mg/MJd. On average, TSPM emissions from CCG2 increased by ~30% compared to CCG1. This increment was ascribed to the worst mixing between the producer gas and CA in CCG2.

Figure 2c shows that the better CO/TSPM ratio (lower emissions) was reached when using CCG1 at cold start, as was previously discussed in Figure 2a,b. Parsons et al. [15] reported that emissions of CO and TSPM were not strongly correlated (R2 = 0.38); moreover, CO emissions were more variable than those of TSPM. Herein, the average value of CO emissions was 2.24 ± 0.80 g/MJd (Figure 2c); thus, the gasification-based cookstove could be classified as Tier 5 according to ISO/TR 19867-3:2018 (Tier 5: CO ≤ 3.0 g/MJd) [46]. Furthermore, the CO emissions are in the order of magnitude of emissions from other gasification-based biomass cookstoves, which are commercialized by Philips HD4, Elegance 2015, and Oorja, whose reported average CO emissions are 3.23 g/MJd, 2.3 g/MJd, and 1.9 g/MJd, respectively [47]. Comparing the reported emissions from the Clean Cooking Catalog for the three-stone fire (CO = 15.5 g/MJd and PM = 943.3 mg/MJd) with the ones from our improved cookstove (CO = 2.24 g/MJd and PM = 98.41 mg/MJd), the reductions in CO and TSPM emissions were about 85.5% and 90%, respectively. In terms of TSPM emission, our improved cookstove is in Tier 3. The low pollutant emissions were attributed to the airflow control capabilities, which affected both primary and secondary air flows; consequently, the combustion efficiency increased due to the two-stage combustion process [5]. It is worth noting that for the CA/GA ratios studied here, the gasification-based cookstove operates under optimal conditions, as the flame is not extinguished and pollutant emissions are low due to the sufficient oxygen to burn the gaseous fuels of the producer gas, as well as the PM [48]. Nevertheless, despite the lower emissions achieved by the gasification-based cookstove, the TSPM will be chemically and morphologically characterized to evaluate the effect of the controllable parameters and combustion chamber design of the improved cookstove on the particles’ properties.

The long-term emission reductions in CO2-equivalent, compared with those of traditional cookstoves (three-stone open fire), depend on the type of improved biomass cookstove and its pot capacity (one, two, or more pots), as well as the experimental protocol followed for assessing the biomass fuel economy. The work by Beyene et al. [49] reports that, on average, each improved biomass cookstove reduces 0.94 tCO2,e/year, where the combustion-based biomass cookstove designed for baking was evaluated under the controlled cooking test protocol. Manaye et al. [50] reported that the CO2,e emissions avoided are about 0.7 tCO2,e/year per improved cookstove (rocket stove) for a single pot based on the kitchen performance test. Meanwhile, Chica and Pérez [51] found that a two-pot improved biomass cookstove can save about 8 tCO2,e/year/stove according to results from the water boiling test protocol. Regarding gasification-based biomass cookstoves, they reduce CO2 emissions by 30–70% compared to three-stone cookstoves, primarily due to fuel savings (33–75% reduction in fuel use) [52]. Therefore, further research is necessary to evaluate the avoided CO2 emissions from gasification-based biomass cookstoves under different experimental conditions.

3.3. Chemical and Morphological Properties of TSPM

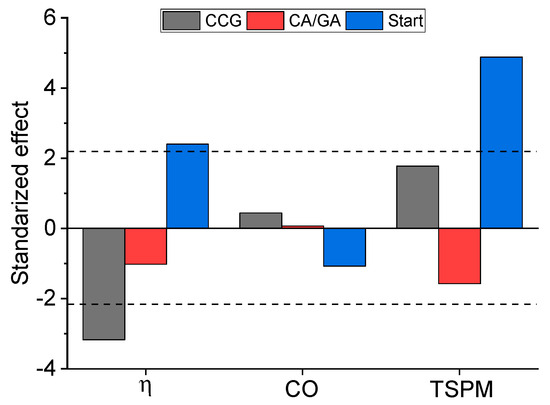

From Figure 3, it can be deduced that the operational parameter with the most significant influence on the specific emission of TSPM was the start type (CS or HS). Nevertheless, when evaluating the physicochemical characteristics of the TSPM emitted, the CA/GA ratio can also play a key role. Therefore, the chemical characterization results below are expressed in terms of these two parameters, as the combustion chamber design assessed here did not produce significant changes in the TSPM chemistry and morphology. Consequently, physicochemical and morphological analyses were performed on the TSPM obtained with CCG1.

Figure 4 shows the FTIR spectra of soot samples taken at two start types (CS and HS) evaluated at three CA/GA levels. Regardless of cold and hot start conditions, the same functional groups were observed on the surface of TSPM, with some differences in intensity associated with variations in the CA/GA ratio. Among the most relevant functional groups that can be seen on the surface of TSPM evaluated in this study are: (1) The O-H stretching mode of hydroxyl functional groups (3400 cm−1) present in alcohols, carboxylic acids, and water. (2) The symmetrical and asymmetrical C-H stretching mode of methyl (-CH3) and methylene (-CH2) groups coming from aliphatic functionalities (2850–2950 cm−1). The low intensity recorded for the aliphatic functional groups has been attributed to their low content and short chain length [53]. (3) The signal at 1650 cm−1 has been mainly associated with the C=C stretching mode of conjugated aromatic ring systems such as those that appear in soot. This signal is also associated with carbonyl groups (C=O) of acids or ketones. (4) The signal at 1450 cm−1 accompanied by an intense peak at 1380 cm−1 confirms the presence of -CH2 and -CH3 species of aliphatic groups previously observed between 2850 and 2950 cm−1. Still, in this case, these signals are due to C-H in-plane bending vibrations (scissoring and twisting). It is also important to note that the sharp intensity at 1380 cm−1 can be attributed to the methyl group of methoxy-like compounds (CH3-O) bound to the TSPM surface. Finally, the intense signal between 900–1200 cm−1 is associated with the C-O stretching mode of alcohol and ether-like compounds (C-OH or C-O-C) [53,54]. These signals are very intense, given the high molar absorptivity of polar groups associated with oxygen [37], suggesting that the relatively high oxygen content in biomass TSPM was most likely attributed to their fuel sources primarily comprising cellulose and lignin, which led to more fractions of radical species (-O and -OH) during the soot formation. Furthermore, biomass TSPM exhibits greater oxygen-fixing abilities compared to hydrocarbon soot [55], with a significant amount of oxygenated species adsorbed on its surface.

Figure 4.

FTIR spectra of TSPM from CS (upper) and HS (lower) conditions operated at different CA/GA ratios. The spectra were separated into two regions to highlight the changes. No PM-related signals were seen between 2000–2800 cm−1.

On the other hand, the impact of the CA/GA ratio on the surface chemistry of TSPM was reflected in the gradual decrease in the intensity of the functional groups when it went from 2.8 to 3.2. This decrease is likely due to the increase in surface oxidation processes caused by the increased combustion air, which promotes the oxidation of various oxygenated groups and some aliphatic compounds, resulting in their passage into the gas phase as CO or CO2 [55]. Then the surface is re-oxidized with O2 to form a new oxygenated species, and the cycle repeats more rapidly as oxygen availability increases. The types of functional groups on the surface of PM examined herein (-OCH3, -OH, C-O-C, -C=O, -COOH) have been proposed in the literature to explain surface gasification of soot with oxygen to produce CO2/CO. A detailed mechanistic explanation for the oxidation of different oxygenated functional groups on the PM surface can be found in Raj et al. [56].

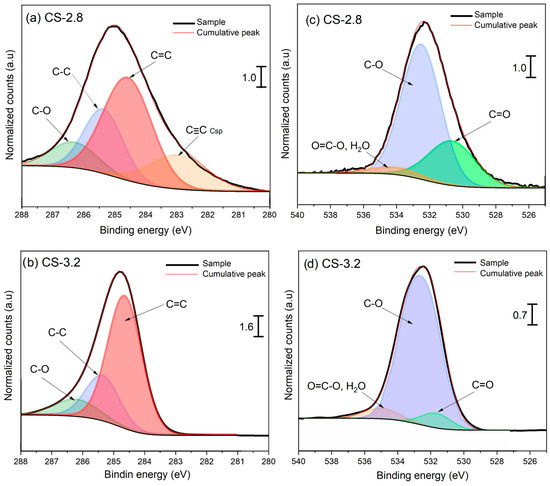

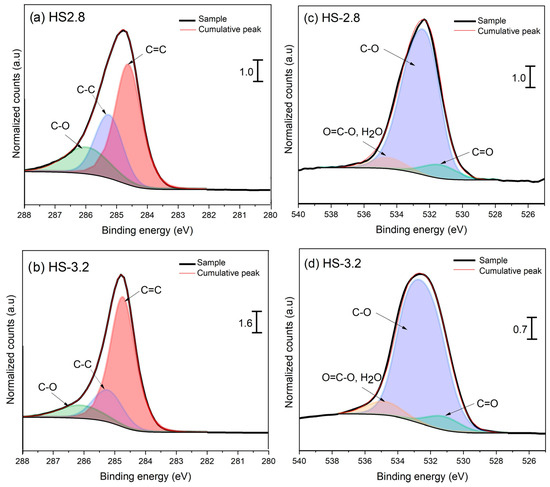

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy also corroborated the variation in the proportion of oxygenated and aliphatic groups. Figure 5 and Figure 6 display the high-resolution spectra for the C1s and O1s of TSPM samples obtained in cold and hot start types, respectively. After Shirley’s background subtraction, the C1s spectra of TSPM samples were decomposed to identify the carbon composition distribution and sp3/sp2 C bonding ratio. Regardless of the start condition, the TSPM samples were mainly composed of graphitic domains (C=C sp2 at 284.6 eV), followed by aliphatic carbon (C-C sp3 at 285.4 eV), and carbon linked to oxygen functionalities in alcohols, ethers, and carboxylic acids (C-O, 287.0–290.0 eV). Although the contribution of the different oxygenated groups through the C1s peak fitting procedure was challenging to achieve, the deconvolution of the O1s peak was much more reliable for disentangling the different carbon–oxygen functionalities. The O1 s spectra were fitted with three peaks: the short peak at 534.6 eV was attributed to O=C-O of carboxylic acids and esters; the major and intense peak at 532.6 eV was assigned to O-C bonding in alcohols, methoxy and ether groups, and the signal at 530.6 eV was associated with O=C groups of quinones and carboxylic acids linked to aromatic rings [38].

Figure 5.

C1s and O1s HR-XPS spectra of TSPM for cold start at: (a,c) CA/GA = 2.8, and (b,d) CA/GA = 3.2. The XPS signals were normalized with respect to the CA/GA ratio = 2.8.

Figure 6.

C1s and O1s HR-XPS spectra of TSPM for hot star at: (a,c) CA/GA = 2.8, and (b,d) CA/GA = 3.2. The XPS signals were normalized with respect to the CA/GA ratio = 2.8.

Like FTIR analysis, no notable difference was found in the types of surface functional groups with the start type, except for the cold start condition evaluated at a CA/GA level of 2.8. This condition exhibited an additional feature in the C1s spectrum at 283 eV, linked to Csp bonding of acetylenic compounds (-C≡C-), which are more easily oxidized as the CA/GA ratio increases [39]. Additionally, the presence of five-membered rings and/or vacancies in graphene sheets could shift the C=C binding energy toward 283 eV [40,41]. Conversely, the effect of CA/GA level was observed in the decrease of oxygenated and aliphatic compounds, with a subsequent rise in C=C species as the CA/GA level increased from 2.8 to 3.2. Examining the Csp2/Csp3 area ratio, it can be inferred that the degree of graphitization of TSPM rises relative to the CA/GA level. This is likely due to the combined influence of temperature and a reactive atmosphere, which enhances oxidation processes, resulting in the removal of labile carbon found in both aliphatic groups and oxygenated carbon (see the C-O/Csp2 ratio in Table 3). This trend is consistent, as both the IR spectra and the O1s XPS data indicate a decrease in these functional groups as the CA/GA level increases. Although the absolute ratios among different oxygenated groups (O=C/O-C and O=C-O/C-O) are not highly distinct, the oxygen content measured by elemental analysis significantly declines with increasing CA/GA ratio, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

TSPM parameters obtained from HR-XPS spectra decomposition analysis.

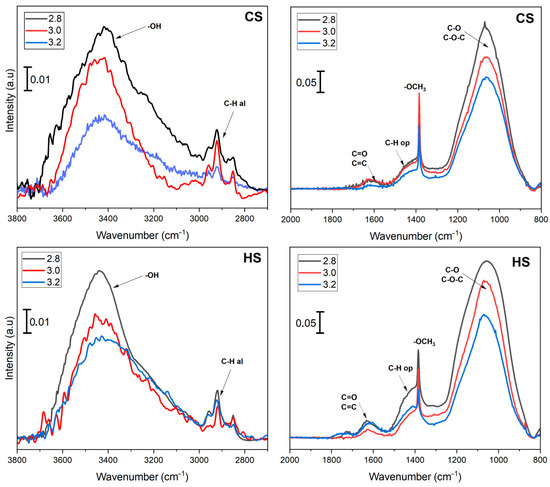

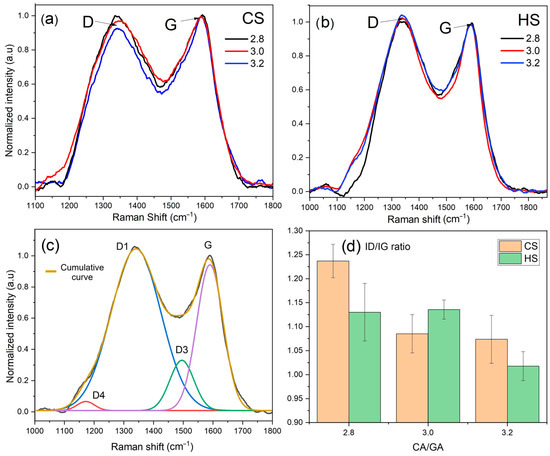

Due to the strong connection between the TSPM structure and its chemistry, Raman spectra analysis was performed to understand how TSPM changes during oxidation under the two start conditions and three CA/GA levels (Figure 7). This analysis provides information about different types of carbon bonds and the level of structural organization in the carbonaceous network (or bulk) of TSPM, supplementing the observations made on the particle surface using FTIR and XPS.

Figure 7.

(a,b) Raman spectra of TSPM obtained at two different start conditions (CS and HS) and three CA/GA levels, (c) Raman decomposition analysis, and (d) ID/IG ratio for CS and HS conditions.

The curve-fitting process of the Raman spectrum for one of the TSPM samples studied is shown in Figure 7c. The Raman spectra were fitted using three Gaussian and one Lorentzian functions to describe the defect and graphitic bands, respectively [37,57]. The band at 1590 cm−1 is attributed to graphite-like compounds and is assigned as the G band. The second strongest band, or D1, located at 1350 cm−1, has been associated with carbon atoms in a graphene layer near a lattice disturbance. The Raman band between the two more intense bands at 1500 cm−1 (or D3) has been assigned to the non-graphitic or molecular carbon content of TSPM. In contrast, the so-called D4 band at 1200 cm−1 has been linked to a disordered graphitic lattice activated by the relaxation of the selection rule due to finite-crystal-size effects and defects, as occurs in graphite whiskers [58].

From Figure 7a, under cold start conditions, a TSPM with a higher degree of structural organization was obtained compared to TSPM samples from hot start in Figure 7b, since the absolute intensities of the D band were slightly lower than the G band in most cases. It can also be observed that under cold start conditions (Figure 7a), the degree of structural order of TSPM increases proportionally as the CA/GA level rises from 2.8 to 3.2. However, for TSPM produced under hot start conditions, no apparent differences in the D band intensities were seen with varying CA/GA ratios, except for the development of the D4 band, which appears as a shoulder of the main disorder band around 1200 cm−1 at a CA/GA ratio of 2.8 and nearly disappears at 3.2. The formation of this band is promoted by the presence of functional groups (mostly oxygenated) attached to the edges of the crystallites, causing structural distortions in the carbon network. This could also happen under cold start conditions; nevertheless, no changes in D4 were observed in this case because the higher temperature favored the oxidation of edge-functional groups. A similar trend was observed for the D3 disorder band, as its presence is also triggered by non-graphitic functional groups within the amorphous carbon, particularly Csp3 from aliphatic compounds, which decreased as the CA/GA level increased under the analyzed reaction conditions.

Similarly, the assessment of the TSPM structural organization level, as determined by the CA/GA ratio and start-type condition, can be confirmed through the ID1/IG relationship derived from the band decomposition process. This relationship indicates that the material is more ordered as the ID1/IG value decreases (see Figure 7d). The above observation suggests that although the combustion-gasification dynamics in cold start produced a TSPM with a higher degree of structural order, no significant differences were found among TSPM samples from both start conditions at CA/GA > 3.0. This means that these TSPMs are chemically and structurally similar.

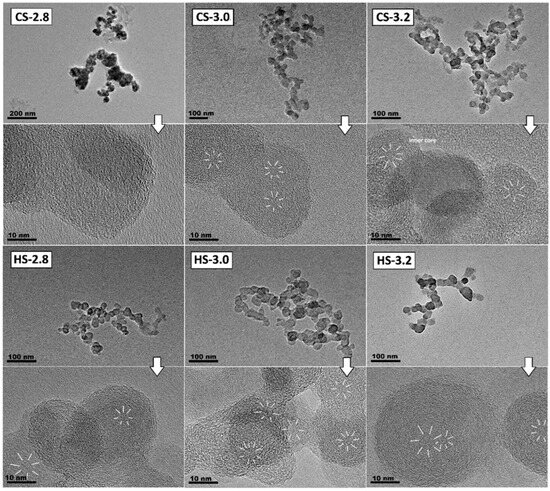

Figure 8 displays representative TEM and HR-TEM images of TSPM from the gasification-based cookstove operated under different conditions. It shows that, regardless of the operating conditions, the TSPM morphology consists of chain-like aggregates composed of hundreds of quasi-spherical primary particles. These particles have an internal structure with onion-like features, with small crystalline domains aligned parallel to the outer edges of the particle volume. Inside are internal nuclei (highlighted by arrows) with stripes arranged in a more chaotic or turbostratic pattern, which is the main component of amorphous carbon. This carbon comprises short, disconnected, and randomly oriented crystalline domains. These traits are typical of soot samples or mature carbonaceous TSPM, regardless of the combustion system and fuel type [37,42,43,44].

Figure 8.

TEM and HR-TEM images of TSPM from a gasification-based cookstove operated at cold and hot starts and three different CA/GA ratios. The inner cores are surrounded by white arrows.

The average particle diameter (dpp), regardless of the operating conditions evaluated here, ranges between 16.3 nm and 26.0 nm, and is slightly smaller than particles found in open combustion systems [37]. However, a closer look at the results shows that the dpp and the particle size range are slightly smaller during cold start (dpp = 17 nm and size range, [16.3–31.0 nm]) than during hot start (dpp = 22.3 nm and size range, [19.2–45 nm]). This difference can be attributed to increased biomass-to-air equivalence ratio in hot conditions, which results in more tar formation. This promotes bulk TSPM formation, resulting in larger primary particles.

These results align with those reported in the literature using improved gasification stoves. Arora et al. [42] evaluated the morphological characteristics of PM emitted by traditional and modified stoves using various biomass mixtures, including wood. In that study, the particle size distribution for the gasification stove was narrower than that observed in the traditional stove, with a dpp ranging from 19 to 26 nm. The slight differences in dpp were linked to the type of fuel used, being slightly higher when only wood was burned. Furthermore, it is worth noting that, unlike the results obtained in the present study, the authors observed tar balls with dpp ranging from 67–104 nm, indicating that the stoves used were not sufficiently efficient. In another study, Just et al. [43] compared the size and morphology of ultrafine particles from a traditional three-stone stove and two modified stoves (one rocket and the other a gasifier). In the improved stoves, the average particle size was smaller—35 nm for the rocket stove and 24 nm for the gasifier—compared to 61 nm for the traditional stove. However, tar-like material, which contributes to the particles’ organic carbon (OC) content, was observed in the TSPM of all stoves, being more prominent in the TSPM from the traditional stove. This tarry material, or tar balls, can increase the reactivity of TSPM and pose greater health risks due to exposure. Therefore, the low or absent evidence of tar in the TSPM obtained in the present study may be a positive aspect, despite the smaller primary particle size observed in this system.

Nevertheless, the detailed physicochemical characterization of the TSPM obtained here is limited to a low-ash, single-fuel source (pine wood pellets). In this context, future studies could examine the effects of ash properties and content in the biomass, as well as the impact of co-combustion involving multiple fuels [59], to expand the analysis of the physicochemical properties of particulate matter emitted from the gasification cookstove.

4. Conclusions

This experimental study investigated the impact of combustion chamber design, air ratios, and start type on the energy, environmental, and particulate emissions of a gasification-based biomass cookstove using a modified WBT protocol. Densified biomass (pellets) significantly improved thermal efficiency (25.4–27.3%) and lowered emissions, reaching Tier 2 for efficiency, Tier 5 for CO (2.24 ± 0.80 g/MJd), and Tier 3 for TSPM (74.1–122.7 mg/MJd). Enhanced airflow in the optimized CCG1 chamber facilitated better gas mixing and combustion. Higher biomass-to-air ratios during hot starts resulted in increased tar production and particulate matter levels.

The surface chemical composition of the TSPM, analyzed using Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), showed that the types of functional groups generally remained unaffected by the start condition (cold or hot start). However, the intensity of these oxygenated and aliphatic functional groups decreased as the combustion-air/gasification-air (CA/GA) ratio increased. This reduction is linked to increased surface oxidation driven by the higher combustion air, which helps remove labile carbon components as CO or CO2. Additionally, Raman spectroscopy confirmed that the degree of graphitization (Csp2/Csp3 ratio) of the TSPM increases with the CA/GA level because of this heightened oxidation and removal of labile carbon. This suggests that raising the CA/GA ratio effectively promotes the organization and maturity of the particle’s carbonaceous network.

The morphology of the TSPM, observed using Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), consistently showed chain-like aggregates composed of quasi-spherical primary particles, typical of mature carbonaceous soot. While operating conditions did not significantly influence the overall particle size, the hot start (HS) condition resulted in a slight increase in the average primary particle diameter (~22.3 nm) compared to the cold start (CS) condition (~17 nm). This difference is linked to the higher biomass-to-air equivalence ratio (Frg) achieved during the hot start, which promotes increased tar formation in the producer gas, thereby enhancing TSPM production and primary particle growth. The analysis revealed little to no evidence of tarry material or “tar balls” in the TSPM. This is considered a positive aspect because tar balls can substantially increase the reactivity of TSPM, raising health risks through exposure.

Author Contributions

J.G.: investigation, data curation, and writing—original draft; A.S.: investigation, data curation, and writing—reviewing and editing; J.F.P.: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, and writing—reviewing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Fundación Universidad de Antioquia (FUA) supported this work through the Grant number FUA–2024–2885.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors (J. Gutiérrez and J.F. Pérez) acknowledge the financial support of Fundación Universidad de Antioquia (FUA) through the research project “Development of an Improved Gasification-Based Biomass Cookstove with Criteria of Autonomy, Energy Efficiency, and Sustainability (in Spanish)”. The support from Dr. Magin Lapuerta of the University of Castilla-La Mancha (UCLM, Spain) regarding TEM images is also acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency; International Renewable Energy Agency; United Nations Statistics Division; World Bank; World Health Organization. Tracking SDG 7: The Energy Progress Report 2025; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren, S. Cookstove Implementation and Education for Sustainable Development: A Review of the Field and Proposed Research Agenda. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 146, 111184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanja, A.; Gasparatos, A. Adoption and Impacts of Clean Bioenergy Cookstoves in Kenya. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 102, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.; Shan, M.; Deng, M.; Carter, E.; Yang, X.; Baumgartner, J.; Schauer, J. Differences in Chemical Composition of PM2.5 Emissions from Traditional versus Advanced Combustion (Semi-Gasifier) Solid Fuel Stoves. Chemosphere 2019, 233, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DANE. Sexto Reporte de Economía Circular; DANE: Bogotá, Colombia, 2022; pp. 1–120.

- Ministerio de Minas y Energía y Unidad de Planeación Minero-Energética. Plan Nacional de Sustitución de Leña Para La Cocción Doméstica de Alimentos; Ministerio de Minas y Energía y Unidad de Planeación Minero-Energética: Bogotá, Colombia, 2022; pp. 1–80.

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2022: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–126. [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu, E.; Warren, S.H.; Ebersviller, S.M.; Kooter, I.M.; Schmid, J.E.; Dye, J.A.; Linak, W.P.; Gilmour, M.I.; Jetter, J.J.; Higuchi, M.; et al. Mutagenicity and Pollutant Emission Factors of Solid-Fuel Cookstoves: Comparison with Other Combustion Sources. Environ. Health Perspect. 2016, 124, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Household Air Pollution; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Household Air Pollution Attributable Deaths; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- MacCarty, N.; Bentson, S.; Cushman, K.; Au, J.; Li, C.; Murugan, G.; Still, D. Stratification of Particulate Matter in a Kitchen: A Comparison of Empirical to Predicted Concentrations and Implications for Cookstove Emissions Targets. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2020, 54, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Energy Access Outlook 2017: From Poverty to Prosperity; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Himanshu; Kurmi, O.P.; Jain, S.; Tyagi, S.K. Performance Assessment of an Improved Gasifier Stove Using Biomass Pellets: An Experimental and Numerical Investigation. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 53, 102432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, S.; Tanner, K.; Champion, W.; Grieshop, A. The Effects of Modified Operation on Emissions from a Pellet-Fed, Forced-Draft Gasifier Stove. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 70, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentson, S.; Evitt, D.; Still, D.; Lieberman, D.; MacCarty, N. Retrofitting Stoves with Forced Jets of Primary Air Improves Speed, Emissions, and Efficiency: Evidence from Six Types of Biomass Cookstoves. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2022, 71, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, D.F.; Gutiérrez, J.; Pérez, J.F. Effect of the Air Flows Ratio on Energy Behavior and NOx Emissions from a Top-Lit Updraft Biomass Cookstove. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2023, 45, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, G.; Islas-Samperio, J.M.; Grande-Acosta, G.K.; Manzini, F. Socioeconomic and Environmental Aspects of Traditional Firewood for Cooking on the Example of Rural and Peri-Urban Mexican Households. Energies 2022, 15, 4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunusa, S.U.; Mensah, E.; Preko, K.; Narra, S.; Saleh, A.; Sanfo, S.; Isiaka, M.; Dalha, I.B.; Abdulsalam, M. Biomass Cookstoves: A Review of Technical Aspects and Recent Advances. Energy Nexus 2023, 11, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.; Chica, E.L.; Pérez, J.F. Parametric Analysis of a Gasification-Based Cookstove as a Function of Biomass Density, Gasification Behavior, Airflow Ratio, and Design. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 7481–7498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, R.; Singh, V.K.; Malik, J.K.; Datta, A.; Pal, R.C. Evaluation of the Performance of Improved Biomass Cooking Stoves with Different Solid Biomass Fuel Types. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 95, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirch, T.; Birzer, C.H.; van Eyk, P.J.; Medwell, P.R. Influence of Primary and Secondary Air Supply on Gaseous Emissions from a Small-Scale Staged Solid Biomass Fuel Combustor. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 4212–4220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-López, N.; Ingabire, A.S.; Bailis, R.; Eriksson, A.C.; Isaxon, C.; Boman, C. Biomass Cookstove Emissions—A Systematic Review on Aerosol and Particle Properties of Relevance for Health, Climate, and the Environment. Environ. Res. Lett. 2025, 20, 053002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuye, A.; Kumar, P. A Review of the Physicochemical Characteristics of Ultrafine Particle Emissions from Domestic Solid Fuel Combustion during Cooking and Heating. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 886, 163747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindgren, R.; García-López, N.; Lovén, K.; Lundin, L.; Pagels, J.; Boman, C. Influence of Fuel and Technology on Particle Emissions from Biomass Cookstoves─Detailed Characterization of Physical and Chemical Properties. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 4458–4472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-López, A.M.; Romero-Menco, F.; Bustamante, F.; Pérez, J.F. Assessment of Reductions in CO, PAHs and PM Emissions in a Forced-Draft Biomass Gasification Cookstove. Renew. Energy 2025, 245, 122815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, W.M.; Warren, S.H.; Kooter, I.M.; Preston, W.; Krantz, Q.T.; DeMarini, D.M.; Jetter, J.J. Mutagenicity- and Pollutant-Emission Factors of Pellet-Fueled Gasifier Cookstoves: Comparison with Other Combustion Sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 139488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Gaddam, C.K.; Ebersviller, S.M.; Vander, R.L.; Williams, C.; Faircloth, J.W.; Jetter, J.J.; Hays, M.D. A Laboratory Comparison of Emission Factors, Number Size Distributions and Morphology of Ultrafine Particles from Eleven Different Household Cookstove-Fuel Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6522–6532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, Y.; Nøjgaard, J.K.; Olesen, H.R.; Brandt, J.; Sigsgaard, T.; Pryor, S.C.; Ancelet, T.; Viana, M.D.M.; Querol, X.; Hertel, O. Emissions and Source Allocation of Carbonaceous Air Pollutants from Wood Stoves in Developed Countries: A Review. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2020, 11, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Gil, D.; Gómez-Peláez, L.M.; Álvarez-Jaramillo, T.; Correa-Ochoa, M.A.; Saldarriaga-Molina, J.C. Evaluating the Impact of PM2.5 Atmospheric Pollution on Population Mortality in an Urbanized Valley in the American Tropics. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 224, 117343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetter, J.; Zhao, Y.; Smith, K.R.; Khan, B.; Yelverton, T.; DeCarlo, P.; Hays, M.D. Pollutant Emissions and Energy Efficiency under Controlled Conditions for Household Biomass Cookstoves and Implications for Metrics Useful in Setting International Test Standards. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 10827–10834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM D5378-08; Standard Test Methods for Instrumental Determination of Carbon, Hydrogen, and Nitrogen in Laboratory Samples of Coal. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008.

- ASTM D5142-04; Standard Test Methods for Proximate Analysis of the Analysis Sample of Coal and Coke by Instrumental Procedures. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004.

- ASTM E144-14; Standard Practice for Safe Use of Oxygen Combustion Vessels. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- Díez, H.E.; Gómez, I.N.; Pérez, J.F. Mass, Energy, and Exergy Analysis of the Microgasification Process in a Top-Lit Updraft Reactor: Effects of Firewood Type and Forced Primary Airflow. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2018, 29, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, M.; Huang, Q. Nanostructure and Reactivity of Soot Particles from Open Burning of Household Solid Waste. Chemosphere 2021, 269, 129395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabali, G.; Castro, T.; De La Cruz, W.; Peralta, O.; Varela, A.; Amelines, O.; Rivera, M.; Ruiz-Suarez, G.; Torres-Jardón, R.; Martines-Quiroz, E.; et al. Morphological and Chemical Characterization of Soot Emitted during Flaming Combustion Stage of Native-Wood Species Used for Cooking Process in Western Mexico. J. Aerosol Sci. 2016, 95, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzvetkov, G.; Tsyntsarski, B.; Balashev, K.; Spassov, T. Microstructural Investigations of Carbon Foams Derived from Modified Coal-Tar Pitch. Micron 2016, 89, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, A.; Yamada, Y.; Koinuma, M.; Sato, S. Origins of Sp3 C Peaks in C1s X-Ray Photoelectron Spectra of Carbon Materials. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 6110–6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. Introduction and Structural Characterizations of Defects on Nano Carbon Materials. Master’s Thesis, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, P.; Jain, S. Morphological Characteristics of Particles Emitted from Combustion of Different Fuels in Improved and Traditional Cookstoves. J. Aerosol Sci. 2015, 82, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, B.; Rogak, S.; Kandlikar, M. Characterization of Ultrafine Particulate Matter from Traditional and Improved Biomass Cookstoves. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 3506–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, A.; Yang, N.; Eddings, E.; Mondragon, F. Chemical and Morphological Characterization of Soot and Soot Precursors Generated in an Inverse Diffusion Flame with Aromatic and Aliphatic Fuels. Combust. Flame 2010, 157, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caubel, J.J.; Rapp, V.H.; Chen, S.S.; Gadgil, A.J. Practical Design Considerations for Secondary Air Injection in Wood-Burning Cookstoves: An Experimental Study. Dev. Eng. 2020, 5, 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Setting National Voluntary Performance Targets for Cookstoves; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Clean Cooking Alliance. Clean Cooking Alliance 2023; Clean Cooking Alliance: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Caubel, J.J.; Rapp, V.H.; Chen, S.S.; Gadgil, A.J. Optimization of Secondary Air Injection in a Wood-Burning Cookstove: An Experimental Study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 4449–4456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyene, A.; Bluffstone, R.; Gebreegzhiaber, Z.; Martinsson, P.; Mekonnen, A.; Vieider, F. Do Improved Biomass Cookstoves Reduce Fuelwood Consumption and Carbon Emissions? Evidence from Rural Ethiopia Using a Randomized Treatment Trial with Electronic Monitoring; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Manaye, A.; Amaha, S.; Gufi, Y.; Tesfamariam, B.; Worku, A.; Abrha, H. Fuelwood Use and Carbon Emission Reduction of Improved Biomass Cookstoves: Evidence from Kitchen Performance Tests in Tigray, Ethiopia. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2022, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chica, E.; Pérez, J.F. Development and Performance Evaluation of an Improved Biomass Cookstove for Isolated Communities from Developing Countries. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2019, 14, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailis, R.; Cowan, A.; Berrueta, V.; Masera, O. Arresting the Killer in the Kitchen: The Promises and Pitfalls of Commercializing Improved Cookstoves. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1694–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, A.; Mondragon, F.; Molina, A.; Marsh, N.; Eddings, E.; Sarofim, A. FT-IR and 1H NMR Characterization of the Products of an Ethylene Inverse Diffusion Flame. Combust. Flame 2006, 146, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, C.; Stanzione, F.; Tregrossi, A.; Ciajolo, A. Infrared Spectroscopy of Some Carbon-Based Materials Relevant in Combustion: Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Hydrogen. Carbon 2014, 74, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, E.M.; Ross, A.B.; Bates, J.; Andrews, G.; Jones, J.M.; Phylaktou, H.; Pourkashanian, M.; Williams, A. Emission of Oxygenated Species from the Combustion of Pine Wood and Its Relation to Soot Formation. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2007, 85, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Da Silva, G.R.; Chung, S.H. Reaction Mechanism for the Free-Edge Oxidation of Soot by O2. Combust. Flame 2012, 159, 3423–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadezky, A.; Muckenhuber, H.; Grothe, H.; Niessner, R.; Pöschl, U. Raman Microspectroscopy of Soot and Related Carbonaceous Materials: Spectral Analysis and Structural Information. Carbon 2005, 43, 1731–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minutolo, P.; Commodo, M.; Santamaria, A.; De Falco, G.; D’Anna, A. Characterization of Flame-Generated 2-D Carbon Nano-Disks. Carbon 2014, 68, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.; Zeng, Y.; Wu, Y.; Kim, R.-G.; Li, Z.; Han, Y.; Li, J.; Jeon, C.; Zhu, X.; Wang, H.; et al. Ash Thermomechanical Properties and Combustion Characteristics during Co-Combustion of Anthracite and Biomass for CFB Combustors. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 198, 107868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).