Abstract

In geothermal systems, polymer injection is vital for improving the sweep efficiency of fluid, but the critical challenge is managing the fluid flow in severely fractured systems. Developing stable plugging agents for these systems is a recurring challenge, allowing the loss of the fluid into the large fractures, hence making the recovery very difficult. The fluid is crucial for several applications like power generation, heating, and cooling without producing any toxic emissions. This study presents a gel system formulated with hydroxyethyl cellulose, and a HMTA–resorcinol crosslinker system for harsh conditions of temperature and salinity. The study employed a Central Composite Design (CCD) for optimizing gel formulation. The system achieved optimal conditions at a gelation time of 0.5 h, and the properties were investigated. The experimental outcomes reveal that the polymer gel can exhibit excellent stability under harsh conditions, withstanding temperatures up to 352 °C. This confirms the robustness of the plugging agent at elevated temperatures. This study offers a sustainable and efficient solution for fluid flow control in severely fractured geothermal systems.

1. Introduction

An artificial geothermal reservoir formed by hydraulic fracturing and other stimulation methods in ultra-low-permeability rocks is termed an enhanced geothermal system (EGS) [1]. It is an advanced technique that enables the efficient extraction of energy from deep underground formations. Geothermal energy is a renewable subsurface resource [2] that emits no greenhouse gases and is used for power generation, heating, cooling, and other applications. It is a clean, dependable, and abundant form of energy [3,4]. However, severely fractured rocks offer a significant disadvantage to the sweep of fluid in the reservoir. This can be controlled by blocking the reservoir’s high-permeability channels [5]. Several plugging agents, such as microbes, foams, polymer microspheres, and gels, have been considered [6]. Microorganisms are difficult to prepare and have a low plugging strength [6], foams are unstable and get damaged easily [7], polymer microspheres have poor rigidity [8], but gels are cost-effective and can easily be prepared [6,9]. Polymer solutions can be injected into reservoirs, forming gels, which block the fractured zones within the reservoir. These gels form 3D network structures and comprise soluble polymers, crosslinkers, and other additives [9,10]. Polymer flooding is a cost-effective approach to control fluid flow for several subsurface applications, such as the EGS, water management, carbon capture and sequestration, and other applications [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19].

Several commercial polymers like polyacrylamide (PAM) and partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide (HPAM) are commonly utilized to produce gels. However, commercial polymers degrade or precipitate at high temperatures [20], causing a major problem in high-salinity reservoirs [21,22,23]. Bulk gels are perhaps the most often used for conformance enhancement purposes [24,25]. They can be used as control and modification agents. Importantly, crosslinkers can improve the stability and strength of bulk gels in any type of unexpected condition to modify their chemical properties. In a situation where the temperature of the formation exceeds 60 °C and 80 °C, inorganic crosslinkers like chromium and zirconium become limited [26]. As a result, the inorganic crosslinkers quickly react with the polymer, and the gel system thermally becomes unstable, giving the gelant solution limited propagation capacity [26,27]. To address these recurring challenges, organic crosslinkers such as phenols, formaldehyde, polyethyleneimine (PEI), hydroquinone (HQ), hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA), and resorcinol [28] can be utilized. Polymer gels formulated with phenol–formaldehyde crosslinkers have been utilized in reservoirs for fluid channeling. However, phenols are carcinogenic [29], and formaldehydes are toxic, making them unfriendly to the environment. In this work, HMTA and resorcinol were used as the primary and secondary crosslinkers, respectively, as substitutes for formaldehyde and phenol crosslinker systems. They are inexpensive, less hazardous, and easy to handle.

Furthermore, several gels were formulated from different sources, and they exhibited excellent properties. Polyacrylamide and its derivatives can be utilized for improved mechanical properties and stability using graphene-based zirconium oxide nanocomposite as a crosslinker to shut off water. At a lower cost, their study greatly reduced the water produced in excess in high-temperature reservoirs [30]. The combination of polymer and surfactant flooding benefits from the use of polymeric surfactants formed by grafting surfactant onto the polymer [31]. However, the use of 0.6 wt% Poly (allyl diglycol carbonate), PADC polymer, resorcinol/hexamethylenetetramine, silicon dioxide (SiO2), and a surfactant in controlled conditions produced a high-strength composite polymer gel with good thermal stability [32]. In another study, gel was formulated with pure PAM/HQ-HMTA containing silica nanoparticles up to 0.3 wt.% at 110 °C, and the gel strength was improved [33].

However, cellulose is a renewable polymer and the most abundant on earth [34,35] and can be produced by algae, fungi, and bacteria [36,37,38]. However, it is primarily derived from plants. Because of its insolubility, it is modified or transformed physically, chemically, and biologically [39,40,41] to produce cellulose derivatives such as the hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC) produced by reacting cellulose with ethylene oxide [42,43]. To produce gels for harsh conditions, they must be prepared with adequate polymers and crosslinkers [44]. On the other hand, the introduction of monomers such as acrylamide and 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropanesulfonic (AMPS) acid can stabilize the overall gel system [20,45,46,47]. AMPS is a potent hydrophilic group that exhibits good hydrolytic stability and is resistant to acid, base, and salt [48,49]. However, HEC has high-salinity resistance [42], excellent water solubility [50], and can also withstand high temperatures. The thermal stability of this cellulose derivative increases when formulated with organic crosslinkers in the presence of an initiator. Because AMPS has a big pendant group, it improves the gel’s stability and strength. It is hydrophilic and contains nonionic and ionic groups, which improve the swelling performance of the gel [51].

In this work, we developed a polymer gel system with HEC and AM/AMPS with HMTA–resorcinol crosslinker systems for severely fractured systems and investigated its stability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC), hexamethylenetetramine (HMTA, >99%), 2-Acrylamido-2-methylpropanesulfonic acid (AMPS, 98%) were sourced from TCI America, Portland, OR, USA; ammonium persulfate (APS, 98%), sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3, 99+%), magnesium chloride hexahydrate (99%); calcium chloride dihydrate (99+%); potassium chloride (99+%); N, N, N, N-Tetramethyl ethylenediamine (TEMED, 99%) were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, NJ, USA. Acrylamide (AM, 99.5%); Resorcinol (99%); ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, 99.4%) were sourced from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA. The relative molecular weights of HEC, AM, AMPS, HMTA, and resorcinol are 154.25, 71.08, 207.24, 140.19, and 110.11, respectively.

2.2. Design of Experiment

A Central Composite Design (CCD) was employed for experimental design to investigate the effect of major factors on gel formulation. Specifically, CCD has a central and star point, and its capability is increased by these points to predict the response (gelation time). These points provided information on the response behavior with high accuracy. In this study, the major factors considered in the design are temperature, HMTA, and resorcinol crosslinker concentrations. The temperature ranged from 103.1 to 161.9 °C while the HMTA and resorcinol each ranged from 0.3 to 0.6 wt%. Minitab software (version 22) was used to design the experiment, and the output is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Central Composite Design (CCD).

2.3. Preparation of Gelant Solution

The polymer solution (gelant) was prepared by reacting HEC, AM, and AMPS with resorcinol and HMTA crosslinkers at room temperature. A total of 1 g of HEC, 2 g AM, and 2 g AMPS were added to 100 g of brine. Afterwards, pre-weighted crosslinkers, 0.05wt% antioxidant, and 0.05wt% heat stabilizer were added based on the overall weight of the polymer solution and agitated at 600 rpm for 3 h. A stock solution of 17% brine containing calcium chloride dihydrate, magnesium chloride hexahydrate, KCl, and NaCl was used in all experiments. Thereafter, 30 mL of the polymer solution was filled into a bottle, leaving about 75% empty as headspace. Nitrogen gas was sparged through the gelant for about 20 min, and then the bottles were transferred into an oven at the desired temperatures. Crosslinking reaction was initiated, and the gelation times were recorded. The process was optimized at a gelation time of 0.5 h and 150 °C. The brine is composed of 49.6% NaCl, 21.6% calcium chloride dihydrate, 10.7% magnesium chloride hexahydrate, and 18.1% KCl.

2.4. Gelation Time

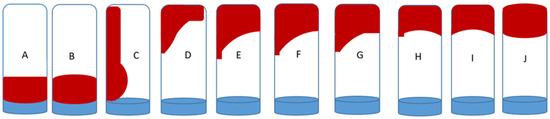

The time taken for the gelant to transform from its viscous, flowing liquid to a non-flowing gel when inverted is called the gelation time. It is described by the Sydansk gel code in Figure 1. This technique is considered convenient and less expensive. During gelation, the strength was expressed as an alphabetic code of A–J [52]. This parameter is very pivotal to determining the gel’s plugging efficiency to enhance the mobility of injected fluid in the geothermal system. The Sydansk gel code ranged from A to a very stable gel code J. The bottle containing the 30 mL gelant was sealed and placed in the oven. In this work, the time taken to reach gel code J was marked as the gelation time.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the Sydansk gel code.

2.5. Rheology of the Gelant Solution

The strengths and viscosities of the gelant at 0%, 1%, 9%, and 17% salinities were determined at room temperature with an OFITE Model 800 viscometer, Houston, TX, USA. This instrument has eight (8) precisely regulated speed ranges of 3 (Gel), 6, 30, 60, 100, 200, 300, and 600 rpm. The strength of each gel prepared at each salt concentration was determined after 10 s and 10 min rotation at 3 rpm (Gel). A regular knob was used to control the viscometer’s speed, and the light-enabled dial panel was used to determine the deflection values.

2.6. Fourier Transform Infrared FTIR Spectroscopy

The spectrum of freeze-dried gel was obtained using Thermo Scientific equipment ID5 ATR (Nicolet IS5), Metuchen, MA, USA. A small amount of the freeze-dried gel was placed directly onto the ATR crystal surface and gently pressed to ensure good contact. Spectra were collected in the mid-infrared region (typically 4000–500 cm−1) at a resolution of 4 cm−1, averaging 32 scans to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. Background spectra were recorded before each measurement under the same conditions to eliminate atmospheric interferences.

2.7. Thermogravimetric Analysis, TGA, and Differential Scanning Calorimetry, DSC

The freeze-dried gel was characterized by using thermogravimetric analyzer (SDT Q600, New Castle, DE, USA) to determine the thermal behavior of the gel from 23 to 650 °C at a heating rate of 20 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere. This instrument measures both the heat flow (DSC) and the change in mass (TGA) of the sample concurrently, allowing for comprehensive characterization of thermal events such as decomposition, phase transitions, and energy changes.

2.8. Scanning Electron Microscopy

The instrument FEI Quanta 650 FEG, Hillsboro, OR, USA, was used to observe the microstructure of the material. A small quantity of freeze-dried gel sample was carbon-coated to make it more conductive. Thereafter, the SEM micrographs were measured at the required magnification.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Reaction Mechanism

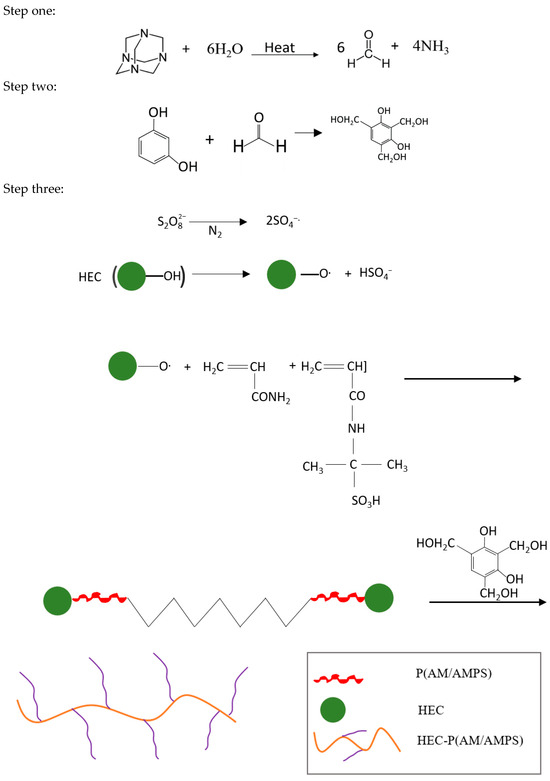

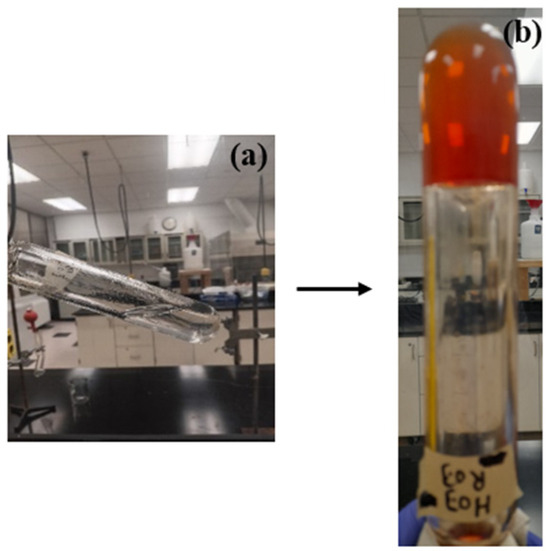

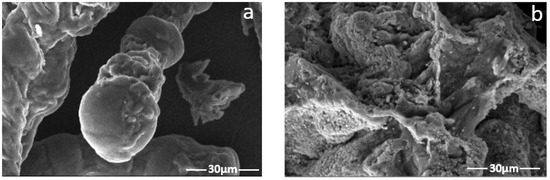

At temperatures above 80 °C, HMTA slowly breaks down into formaldehyde (HCHO) and ammonia (NH3) to produce a very complex ion. Free NH3 can be absorbed when NH3 and the heat stabilizer reacts. Additionally, the reaction between resorcinol and formaldehyde produces 4,6-bis(hydroxymethyl)benzene-1,3-diol [20]. The preceding step’s resorcinol is replaced by hydroxymethyl, which is next subjected to a polycondensation process, resulting in a crosslinked cluster to form the gel. Figure 2 presents the breakdown of reaction steps, while Figure 3 reveals the physical transformation of the gel. Figure 4 presents the 3D microstructure of the polymer gel because of the crosslinking reaction between the polymer and HMTA–resorcinol systems, and has some dispersed pores compared to the images of the HEC. The microstructure scan improves gel strength and can efficiently retain water while continuously improving the fluid sweep at high temperatures. The polymer gel properties are enhanced due to increased interfacial interaction between the polymerized molecule (HEC-P(AM/AMPS) and the crosslinker.

Figure 2.

Reaction mechanism for the HEC-P(AM/AMPS) gel system.

Figure 3.

(a) Gelant solution composed of 0.3 wt.% HMTA and 0.3 wt.% resorcinol; (b) gel composed of 0.3 wt.%HMTA and 0.3 wt.% resorcinol.

Figure 4.

(a) SEM image of HEC; (b) SEM image of the gel composed of 0.3 wt.% HMTA and 0.3 wt.%).

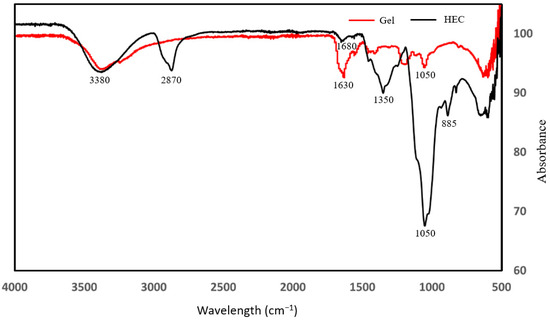

3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

Figure 5 shows the spectra of the HEC-P(AM/AMPS) gel system and HEC. A peak around 3380 cm−1 reveals the presence of O–H, while the smaller peak around 2870 cm−1 reveals C–H stretching, indicating alkyl groups (-CH2 or -CH3) and the peak around 1050 cm−1 reveals the presence of C–O. Peaks between 1630 and 1450 are likely showing C=C stretching in aromatic rings and CH2 bending modes, reflecting possible aromatic structures or hydrocarbon backbones. These peaks also represent the fingerprint region of the compound and the presence of oxygen-containing functionalities. Compared to HEC, the gel shows noticeable shifts and intensity changes in the O–H and C–O stretching regions, indicating successful polymerization or crosslinking between HEC and the crosslinker.

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of the HEC and HEC-AM/AMPS gel systems.

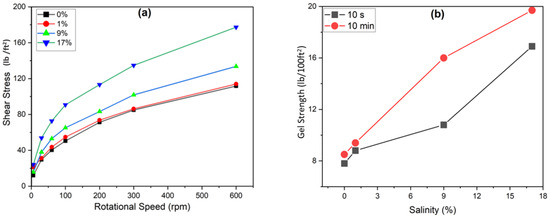

3.3. Rheology of the Gelant Solution

This measurement provides information on the effect of rotational speed on shear stress. The gel strength of the gelant solution was determined at different salinities at room temperature (Figure 6), indicating an increase in shear stress with rotation. The 10 s gel strength measurement at 0, 1, 9, and 17% salinity levels were 7.8, 8.8, 10.8, and 16.9 lb/100 ft2, respectively, while at 10 min counting time, the strengths of the gelant were 8.5 lb/100 ft2, 9.4 lb/100 ft2, 16 lb/100 ft2, and 19.7 lb/100 ft2, respectively. The 10 s resting time reveals the instantaneous viscosity to understand early-time kinetics of gelation while the 10 min resting time assesses how the viscosity evolves with time to understand the time-dependent behavior relevant to field applications. The results obtained demonstrate that viscosity increases with salinity.

Figure 6.

(a) Shear stress vs. rotational speed (0.3 wt.% HMTA and 0.3 wt.%) and (b) effect of salinity on gelant (0.3 wt.% HMTA and 0.3 wt.%).

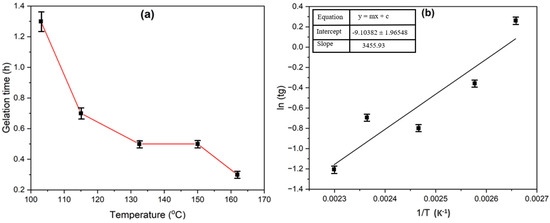

3.4. Effect of Temperature

To study the performance of gels, an important factor is the temperature [53], which determines the level of crosslinking. It can be observed in Figure 7 that gelation time decreases as temperature increases. This proves the increased polymer’s effective collision and the crosslinker during crosslinking. The gelation time-temperature relationship is described by an Arrhenius equation [54]:

where Tg (h), A, Ea (kJ/mol), and R (mol−1K−1) are gelation time, effective collision frequency factor between activated molecules, activation energy between activated molecules and the reactants, universal gas constant, and the absolute temperature, respectively.

Figure 7.

(a) Effect of temperature effect on gelation time of gel composed of 0.3 wt% HMTA and 0.3 wt% resorcinol; (b) Arrhenius plot.

By taking the natural log of the Arrhenius equation:

From the Arrhenius plot, the slope is 3455.93. Ea is given as 28.73 kJ/mol.

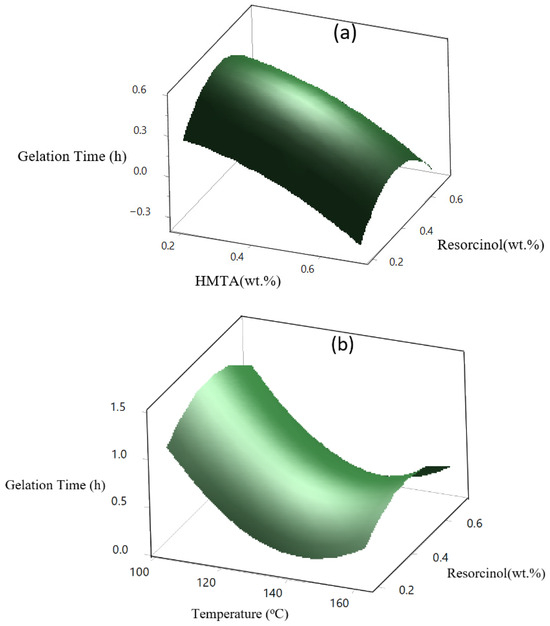

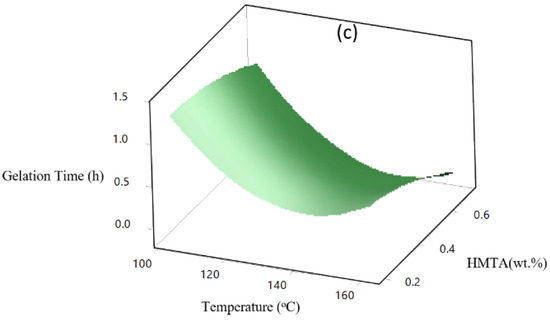

3.5. Effect of Temperature and Crosslinker Concentration

The major factor in this study is temperature, with higher temperatures consistently reducing gelation times. The combined effect of HMTA and resorcinol contributes to faster gelation, as shown in the 3D surface plot in Figure 8a. HMTA accelerates the gelation time, and this is likely due to its role as a curing agent that promotes crosslinking reactions. On the other hand, resorcinol, being a secondary crosslinker in the formulation, increases its concentration, providing more reactive sites for polymerization, leading to faster gelation. The combined effect of increasing both HMTA and resorcinol leads to a significant reduction in gelation time. Figure 8b presents the 3D surface plot, showing how increasing resorcinol concentration reduces the gelation time. Resorcinol is crucial in forming the polymer network, and an increase in its concentration contributes to faster crosslinking and shorter gelation time. The surface plot exhibits a steep decline, revealing that temperature reduces gelation time more effectively than resorcinol. In Figure 8c, as in HMTA, gelation time significantly reduces. This pattern suggests that a higher temperature shortens the gelation time. This is probably because the polymer crosslinks more quickly and the reaction kinetics are faster. Additionally, because HMTA functions as a curing agent and larger concentrations enhance more effective crosslinking, gelation occurs more quickly. In conclusion, the sharp decline shows that an increase in temperature affects gelation more than HMTA concentration.

Figure 8.

(a) Effect of temperature, HMTA and resorcinol) crosslinker on gelation time, (b) effect of temperature and HMTA concentration on gelation time, and (c) effect of temperature and resorcinol concentration on gelation time.

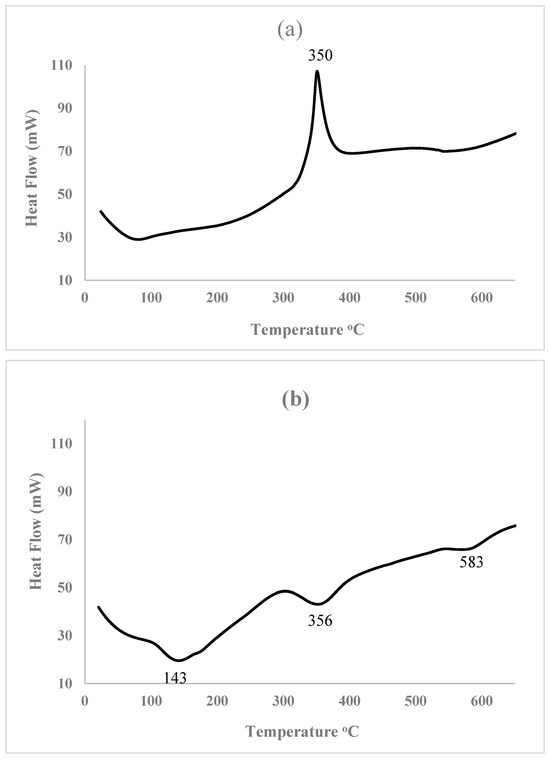

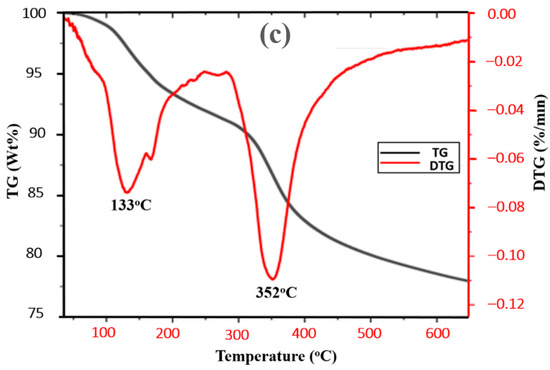

4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

The DSC and TGA plots revealed the thermal behavior of HEC and the gel formulated with 0.3 wt% HMTA and 0.3 wt% resorcinol over the temperature range of 23–650 °C. To evaluate the energy consumption characteristics of gels, DSC and TGA techniques have proven to be highly effective for analyzing their thermal properties, particularly, TGA prevents the shrinkage [55]. From the thermogram, the gel system exhibits stability up to 352 °C, as evidenced by the TG and DTG plots in Figure 9. Below 100 °C, there was loss of absorbed water, which is expected of gels due to their hydrophilic matrix, and 100 to 300 °C endothermic region corresponds to the release of entrapped solvents or dehydration of crosslinked structures of the polymeric chains. Crosslinking contributes to enhanced thermal stability [56,57] and the gel’s structural integrity, making it suitable for blocking fractures in reservoirs. The TGA result reveals that at 133 °C, the weight of material was 92%, indicating a loss of about 8% of the material. While at 650 °C, 22% of the material is lost due to thermal effects, leaving approximately about 78%. From the DSC plot, the gel exhibits a broadened and shifted degradation profile demonstrating improved thermal stability compared to HEC. This demonstrates the material’s resilience against high temperatures, crucial for application in geothermal systems. These results demonstrate the effect of crosslinking in the gel matrix, which enhanced the thermal stability of the gel [56].

Figure 9.

(a) DSC plot for HEC, (b) DSC plot for polymer gel, and (c) TG and DTG plots for polymer gel composed of 0.3 wt% HMTA and 0.3 wt% resorcinol.

5. Conclusions

In this work, a polymer gel system for improving the sweep efficiency of fluid in severely fractured geothermal systems was developed using hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC). The gelation was adjusted with crosslinker concentrations ranging from 0.3 wt% to 0.6 wt% and temperature ranging from 103 °C to 161.9 °C. From the TGA results, the gel demonstrates excellent stability up to 352 °C, demonstrating the stability of the gel at high temperature. Beyond this temperature, the gel began to degrade significantly due to weakening chemical bonds, losing approximately 22% of its weight by 650 °C, demonstrating low syneresis at high temperature. Additionally, the rheology of gelant solution indicates an increased strength and viscosity. The distinct phases of the gel were revealed by the DSC, demonstrating distributed thermal behavior compared to HEC. The network in the structure of the gel holds water firmly, hence improving the sweep efficiency of injected fluid in the formation. The findings from this study demonstrate the suitability of the gel for application in severely fractured geothermal systems.

Author Contributions

Methodology, O.O.; formal analysis, O.O., Y.J. and G.D.; investigation, D.W.; data curation, O.O., Y.J. and F.A.B.; writing—review and editing, Y.J.; supervision, Y.J.; project administration, Y.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the North Dakota Industrial Commission (NDIC) and the University of North Dakota College of Engineering and Mines, grant number: NDIC-R-050-065.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Yu, P.; Dempsey, D.; Archer, R. Techno-Economic feasibility of enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) with partially bridging Multi-Stage fractures for district heating applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 257, 115405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ji, Y.; Gosnold, W.; Alamooti, M.; Namie, S.; Oni, O. Enhanced Sweep Efficiency in EGS Using a Bio-polymer Supplement from Over Fractured Oil/Gas Operations. Transactions 2023, 47, 2550–2562. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Liu, G.; Liao, S. Probing fractured reservoir of enhanced geothermal systems with fuzzy inversion model. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 390, 135822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, C.K.; Liu, Y.; Wei, M.; Bai, B.; Schuman, T. Evaluating the Efficiency of High Temperature Preformed Particle Gels in Sealing Fractures Within Granite-Based Enhanced Geothermal Systems: A Preliminary Study. In Proceedings of the 49th Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering, Stanford, CA, USA, 12–14 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Zhong, L.; Wang, C.; Li, S.; Yuan, X.; Liu, Y.; Meng, X.; Zou, J.; Wang, Q. Investigation of a high temperature gel system for application in saline oil and gas reservoirs for profile modification. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 195, 107852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Lian, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Lin, C.; Yuan, H.; Han, M.; Lu, G.; et al. Synthesis and performance evaluation of multi-crosslinked preformed particle gels with ultra-high strength and high-temperature and high-salinity resistance for conformance control. Fuel 2024, 357, 130027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Kang, W.; Li, X.; Peng, L.; Yang, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Gao, Z.; Turtabayev, S. Stabilization and performance of a novel viscoelastic N2 foam for enhanced oil recovery. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 337, 116609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhao, T.; Lv, W.; Ma, B.; Hu, Q.; Ma, X.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, M.; Yu, Z.-Z.; Yang, D. Nanoscale Polyacrylamide Copolymer/Silica Hydrogel Microspheres with High Compressive Strength and Satisfactory Dispersion Stability for Efficient Profile Control and Plugging. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 10193–10202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.B.; Soleimanian, M.; Moghadam, A.M. Examination of disproportionate permeability reduction mechanism on rupture of hydrogels performance. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 560, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albonico, P.; Bartosek, M.; Lockhart, T.P.; Causin, E. New Polymer Gels for Reducing Water Production in High-Temperature Reservoirs. In Proceedings of the European Production Operations Conference and Exhibition, Aberdeen, UK, 15–17 March 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Bai, B.; Eriyagama, Y.; Schuman, T. Lysine Crosslinked Polyacrylamide—A Novel Green Polymer Gel for Preferential Flow Control. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 4419–4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E. Geothermal energy technology and current status: An overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2002, 6, 3–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olasolo, P.; Juárez, M.C.; Morales, M.P.; D’Amico, S.; Liarte, I.A. Enhanced geothermal systems (EGS): A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.L.; Kurokawa, T.; Kuroda, S.; Ihsan, A.B.; Akasaki, T.; Sato, K.; Haque, M.A.; Nakajima, T.; Gong, J.P. Physical hydrogels composed of polyampholytes demonstrate high toughness and viscoelasticity. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.W.J.; Celia, M.A. Infrastructure to enable deployment of carbon capture, utilization, and storage in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E8815–E8824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Abbaspourrad, A.; Parsa, S.; Tang, J.; Cassiola, F.; Zhang, M.; Tian, S.; Dai, C.; Xiao, L.; Weitz, D.A. Core–Shell Nanohydrogels with Programmable Swelling for Conformance Control in Porous Media. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 34217–34225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albonico, P.; Lockhart, T.P. Stabilization of polymer gels against divalent ion-induced syneresis. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 1997, 18, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Otake, K.; Zheng, J.-J.; Horike, S.; Kitagawa, S.; Gu, C. Separating water isotopologues using diffusion-regulatory porous materials. Nature 2022, 611, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Wang, Z.; Legrand, A.; Aoyama, T.; Ma, N.; Wang, W.; Otake, K.; Urayama, K.; Horike, S.; Kitagawa, S.; et al. Hypercrosslinked Polymer Gels as a Synthetic Hybridization Platform for Designing Versatile Molecular Separators. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 6861–6870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.; Hou, J.; Wei, Q.; Wu, X.; Bai, B. Terpolymer Gel System Formed by Resorcinol–Hexamethylenetetramine for Water Management in Extremely High-Temperature Reservoirs. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuermann, S.; Buback, M.; Hesse, P.; Lacık, I. Free-Radical Propagation Rate Coefficient of Nonionized Methacrylic Acid in Aqueous Solution from Low Monomer Concentrations to Bulk Polymerization. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhai, W.; Cai, B.; Lu, Y.; Qiu, X. 220 °C Ultra-Temperature Fracturing Fluid in High Pressure and High Temperature Reservoirs. In Proceedings of the Offshore Technology Conference Asia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 22–25 March 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funkhouser, G.P.; Norman, L.R. Synthetic Polymer Fracturing Fluid for High-Temperature Applications. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Oilfield Chemistry, Houston, TX, USA, 5–7 February 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantz, M.; Muniz, G. Conformance Improvement Using Polymer Gels: A Case Study Approach. In Proceedings of the SPE Improved Oil Recovery Symposium, Tulsa, OK, USA, 12–16 April 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydansk, R.D.; Southwell, G.P. More Than 12 Years’ Experience With a Successful Conformance-Control Polymer-Gel Technology. SPE Prod. Facil. 2000, 15, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Dai, C.; You, Q.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, J. Study on formation of gels formed by polymer and zirconium acetate. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2013, 65, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfaghari, R.; Katbab, A.A.; Nabavizadeh, J.; Tabasi, R.Y.; Nejad, M.H. Preparation and characterization of nanocomposite hydrogels based on polyacrylamide for enhanced oil recovery applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 100, 2096–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Adhya, P.; Kaushal, M.; Kulkarni, S.D. Engineering water-shut-off operations: Application of rheological time-temperature superposition approach for organically-crosslinked polymer gel systems. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2025, 244, 213431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Pu, W.-F.; Zhao, J.-Z.; Liao, R. Experimental Investigation of the Novel Phenol−Formaldehyde Cross-Linking HPAM Gel System: Based on the Secondary Cross-Linking Method of Organic Cross-Linkers and Its Gelation Performance Study after Flowing through Porous Media. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoshin, A.M.; Alsharaeh, E.; Fathima, A.; Bataweel, M. A Novel Polymer Nanocomposite Graphene Based Gel for High Temperature Water Shutoff Applications. In Proceedings of the SPE Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Annual Technical Symposium and Exhibition, Dammam, Saudi Arabia, 23–26 April 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, N.; Babu, K.; Mandal, A. Surface tension, dynamic light scattering and rheological studies of a new polymeric surfactant for application in enhanced oil recovery. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2016, 146, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashari, Z.A.; Yang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Tang, X.; Cao, C.; Iqbal, M.W.; Kang, W. Experimental research of high strength thermally stable organic composite polymer gel. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 263, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, C.; Wang, K.; Zou, C.; Gao, M.; Fang, Y.; Zhao, M.; Wu, Y.; You, Q. Study on a Novel Cross-Linked Polymer Gel Strengthened with Silica Nanoparticles. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 9152–9161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, M.; Si, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, B. Cellulose nanocrystals and cellulose nanofibrils based hydrogels for biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 209, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Du, H.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, G.; Zhang, X.; Si, C.; Li, B.; Peng, H. Comparative Evaluation of the Efficient Conversion of Corn Husk Filament and Corn Husk Powder to Valuable Materials via a Sustainable and Clean Biorefinery Process. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 1327–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Parit, M.; Wu, M.; Che, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, R.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Z.; Li, B. Sustainable valorization of paper mill sludge into cellulose nanofibrils and cellulose nanopaper. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 400, 123106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Du, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, K.; Liu, H.; Xie, H.; Zhang, X.; Si, C. Bacterial Cellulose-Based Composite Scaffolds for Biomedical Applications: A Review. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 7536–7562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Du, H.; Liu, H.; Xie, H.; Xu, T.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Si, C. Highly Efficient and Sustainable Preparation of Carboxylic and Thermostable Cellulose Nanocrystals via FeCl 3 -Catalyzed Innocuous Citric Acid Hydrolysis. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 16691–16700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Tan, H. Effects of cellulase on the modification of cellulose. Carbohydr. Res. 2002, 337, 1291–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Olyveira, G.M.; Dos Santos, M.L.; Costa, L.M.M.; Daltro, P.B.; Basmaji, P.; De Cerqueira Daltro, G.; Guastaldi, A.C. Bacterial Cellulose Biocomposites for Guided Tissue Regeneration. Sci. Adv. Mater. 2014, 6, 2673–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash Menon, M.; Selvakumar, R.; Suresh Kumar, P.; Ramakrishna, S. Extraction and modification of cellulose nanofibers derived from biomass for environmental application. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 42750–42773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Bai, B.; Hou, J. Polymer Gel Systems for Water Management in High-Temperature Petroleum Reservoirs: A Chemical Review. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 13063–13087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Kang, Y.; Wang, A. Synthesis, swelling and responsive properties of a new composite hydrogel based on hydroxyethyl cellulose and medicinal stone. Compos. Part B Eng. 2011, 42, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Ge, J.; Li, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, W. Development, evaluation and stability mechanism of high-strength gels in high-temperature and high-salinity reservoirs. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 399, 124452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narimani, A.; Kordnejad, F.; Kaur, P.; Bazgir, S.; Hemmati, M.; Duong, A. Rheological and thermal stability of interpenetrating polymer network hydrogel based on polyacrylamide/hydroxypropyl guar reinforced with graphene oxide for application in oil recovery. J. Polym. Eng. 2021, 41, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, N.; Giovannetti, B.; Leblanc, T.; Thomas, A.; Braun, O.; Favero, C. Selection of Customized Polymers to Enhance Oil Recovery from High Temperature Reservoirs. In Proceedings of the SPE Latin American and Caribbean Petroleum Engineering Conference, Quito, Ecuador, 18–20 November 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandengen, K.; Meldahl, M.M.; Gjersvold, B.; Molesworth, P.; Gaillard, N.; Braun, O.; Antignard, S. Long term stability of ATBS type polymers for enhanced oil recovery. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 169, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Qu, J.; Tan, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lin, T.; Yang, H.; Peng, J.; Zhai, M. Synthesis and property of superabsorbent polymer based on cellulose grafted 2-acrylamido-2-methyl-1-propanesulfonic acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 233, 123643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Fan, F.; Liu, X.; Guo, Y.; Ni, Z.; Wang, S. Old wine and new bottles: Insights into traditional attapulgite adsorbents with functionalized modification strategies applied in efficient phosphate immobilization. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 395, 136451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, F.; Zhang, J.; Kang, M.; Ma, C.; Li, H.; Qiu, Z. Hydroxyethyl cellulose hydrogel modified with tannic acid as methylene blue adsorbent. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138, 49880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atta, A.M.; Ismail, H.S.; Elsaaed, A.M. Application of anionic acrylamide-based hydrogels in the removal of heavy metals from waste water. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 123, 2500–2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydansk, R.D. A New Conformance-Improvement-Treatment Chromium(lll) Gel Technology. In Proceedings of the SPE Enhanced Oil Recovery Symposium, Tulsa, Oklahoma, 16–21 April 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, B.; Sharma, V.P.; Udayabhanu, G. Gelation studies of an organically cross-linked polyacrylamide water shut-off gel system at different temperatures and pH. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2012, 81, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, D.S.; Green, D.W.; Terry, R.E.; Willhite, G.P. The Effect of Temperature on Gelation Time for Polyacrylamide/Chromium (III) Systems. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 1982, 22, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Young, T.M.; Liu, P.; Contescu, C.I.; Huang, B.; Wang, S. Ultralight carbon aerogel from nanocellulose as a highly selective oil absorption material. Cellulose 2015, 22, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wu, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y. Viscoelasticity and thermal stability of polylactide composites with various functionalized carbon nanotubes. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2008, 93, 1577–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimpour-Shishevan, F.; Akbulut, H.; Mohtadi-Bonab, M.A. Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Carbon/Basalt Intra-ply Hybrid Composites. I. Effect of Intra-ply Hybridization. Fibers Polym. 2020, 21, 2579–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).