Abstract

Concrete is the second most consumed material after water, with cement as its primary binder. However, cement production accounts for nearly 7% of global CO2 emissions, posing a major sustainability challenge. This review critically evaluates 35 agricultural biomass ashes (ABAs) as potential supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) for partial cement replacement, focusing on their effects on concrete strength and durability and highlighting performance gaps. Using a systematic methodology, rice husk ash (RHA), sugarcane bagasse ash (SCBA), and wheat straw ash (WSA) were identified as the most promising ABAs, enhancing strength and durability—including resistance to chloride ingress, sulfate attack, acid exposure, alkali–silica reaction, and drying shrinkage—while maintaining acceptable workability. Optimal replacement levels are recommended at 30% for RHA and 20% for SCBA and WSA, balancing performance and sustainability. These findings indicate that ABAs are viable, scalable SCMs for low-carbon concrete, promoting greener construction and contributing to global climate mitigation.

1. Introduction

Concrete is the second most consumed material after water [1], valued for its strength, durability, fire resistance, and cost-effectiveness [2]. At its core is cement, a hydraulic binder responsible for approximately 7% of global CO2 emissions, making it the second-largest industrial emitter of carbon dioxide [3]. Cement is produced from finely ground inorganic materials that react exothermically with water, undergoing a chemical process known as hydration, which forms a paste that binds aggregates such as sand and gravel to create concrete products [4].

The most commonly used cement in concrete production is ordinary Portland cement (OPC). The production of OPC involves several stages, beginning with the extraction and grinding of raw materials, primarily limestone (CaCO3) and clay, which contain silicon dioxide (SiO2), aluminum oxide (Al2O3), and iron oxide (Fe2O3). The materials are subsequently heated in a kiln to approximately 800–900 °C [5], where calcination takes place, producing calcium oxide (CaO) and releasing carbon dioxide (CO2) as a byproduct [6]. The calcined feed is then heated to around 1500 °C, where a series of chemical reactions and mineral phase transformations occur, leading to the formation of clinker phases [5], as summarized in Table 1. The resulting clinker, consisting of dark gray spherical nodules, is cooled and finely ground with gypsum to produce cement [6].

Table 1.

Key Raw Materials, Chemical Roles, and Reactions in Clinker and Cement Production, Adapted from [5,6].

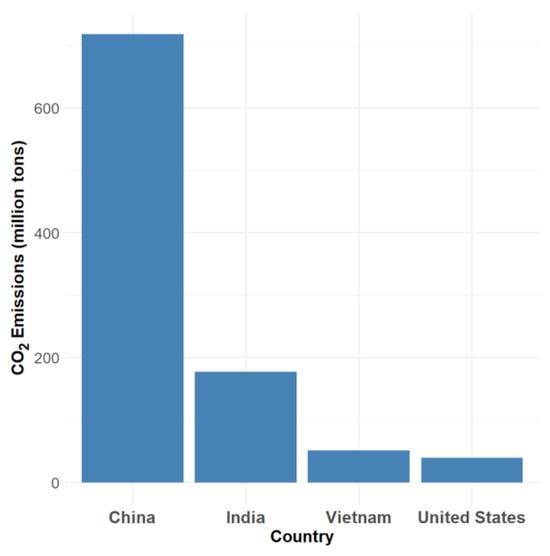

Based on estimated global averages, cement production is highly energy-intensive, requiring 60–130 kg of fuel oil and 110 kWh of electricity per ton of cement produced. The production of one ton of cement results in the emission of approximately one ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) [1]. Figure 1 illustrates the four countries with the highest CO2 emissions from cement production in 2023, along with their respective emission levels. The data are based on territorial emissions, which include only those generated within a country’s borders and exclude emissions associated with imported goods.

Figure 1.

CO2 Emissions from Cement Production in 2023, adapted from [7].

As global cement demand is expected to rise by up to 20% by 2050, there is increasing urgency to reduce emissions from cement production [3]. The cement industry must reduce emissions by 4% annually from 2020 to 2030 to meet the International Energy Agency’s Net Zero by 2050 Scenario [3]. This reduction is essential to align with the Paris Climate Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to well below 2 °C, with the aspiration of limiting it to 1.5 °C [1]. Approximately 50% of CO2 emissions in cement production stem from clinker calcination, 40% from fuel combustion, and 10% from electricity consumption and transportation [1]. To reduce these emissions, various strategies are being explored, including improving energy efficiency, using alternative fuels, reducing clinker production, and implementing carbon sequestration. Among these, reducing the clinker factor through the use of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs)—which include soluble siliceous, aluminosiliceous, or calcium-aluminosiliceous compounds—is a key approach. SCMs, which can be used as partial replacements for cement, not only lower clinker demand, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions but also enhance the mechanical performance and durability of the resulting concrete, making it a cost-effective and environmentally friendly alternative to concrete made with 100% OPC [8].

While fly ash and slag are commonly used SCMs, their application faces certain challenges. Slag, which accounts for less than 10% of global cement production, is limited by the availability of steel recycling processes. Fly ash, although more widely available, suffers from inconsistent quality, and its long-term supply is threatened by the decline of coal-based electricity generation [9]. In this context, a promising, viable, and sustainable alternative SCM is biomass ash—particularly agricultural biomass ash (ABA)—produced from agricultural waste through a controlled incineration process.

This review analyzes existing research on the incorporation of ABAs into concrete mixtures as a strategy to reduce clinker production and, consequently, lower carbon emissions. In addition to these benefits, the use of ABAs helps mitigate harmful gas emissions from open-field burning—an issue particularly prevalent in countries such as China and India, which together account for approximately 33.4% of global open-field burning. Furthermore, controlled incineration of agricultural biomass can generate steam energy for electricity production, adding another layer of environmental and economic value [9].

Previous studies have shown that the partial addition of certain types of ABAs—such as rice husk [10,11], millet husk [12,13], wheat straw [14], highland barley straw [15], oat husk [16], palm leaf [17], rice straw [18,19], sugarcane bagasse [20,21,22], sorghum husk [23,24], and cashew nutshell [25]—into OPC can enhance the strength of concrete. In contrast, others—such as corn cob [26,27], sawdust [28,29,30,31], crushed coconut shell [32,33,34], bamboo leaf [35,36,37], and banana leaf [38,39,40,41]—have produced inconsistent results.

Although interest in ABA is growing, most studies—such as those referenced above—focus on individual ash types. When multiple ashes are examined within a single study, the rationale behind their selection is often not clearly explained. Additionally, few studies have conducted direct performance comparisons of different ABAs in cement, particularly in terms of their potential as SCMs. This absence of clear justification and comparative analysis limits the broader applicability of existing findings and hinders a comprehensive understanding of which ash types are most effective for cement applications.

In response to these gaps, this study systematically reviews the research performed on 35 types of biomass ash to assess their potential as SCMs in structural concrete, with a focus on strength, durability, and overall performance in concrete mixtures. By identifying the most promising types of biomass ash for use as SCMs, this research provides valuable insights into how these alternative materials can be integrated into concrete production to meet sustainability goals and enhance structural performance. Ultimately, the study aims to support the development of more sustainable and cost-effective alternatives to traditional cement, advancing the use of biomass ash in the construction industry.

2. Methodology

This study utilized three primary databases—Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar—to identify various types of agricultural biomass ashes (ABAs) investigated in concrete production, including those not specifically reported as supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). The potential of these ABAs as partial cement replacements was evaluated using ASTM C618-22 [42] as the primary benchmark for pozzolanic suitability, followed by further assessment of their performance in structural concrete applications.

As detailed in Table 2, 35 distinct types of ABAs applied in concrete production were identified and classified into nine categories based on their type. This classification scheme is grounded in the biological origin of the biomass and the stage of agricultural processing at which the residues are generated, both of which significantly influence ash composition and physicochemical properties. The nine ash categories include husk, straw, stalk, shell, wood-based, leaf, grass-derived, agricultural processing residues, and fruit/root processing residues.

Table 2.

Types of Agricultural Biomass Ashes (ABAs) Used in the Cement Industry, Classified into Nine Categories.

The studies published over the last two decades were included, prioritizing research that investigated the experimental use of ABAs in concrete production. This time frame was chosen to capture the growing emphasis on sustainable alternatives to traditional cement, particularly as global demand for concrete rises. Observed limitations of this study include the unavailability and consistency of experimental data across all ABAs, which may be influenced by variations in factors such as the origins of the ABAs, their treatment methods, and the water-to-binder ratio used in the experiments. Despite these limitations, the suitability of these 35 ABAs as SCMs was evaluated using a two-step methodology based on the experimental findings of the selected studies:

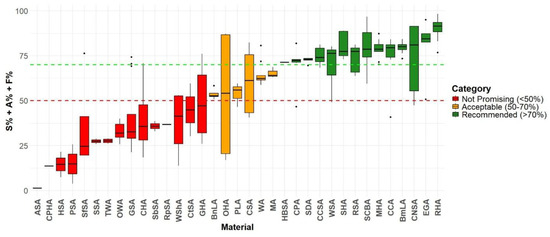

Step 1: Evaluation of ABA for Compliance with ASTM C618-22

The compliance of alternative ABAs with the ASTM C618-22 standard was evaluated to determine their suitability for use as pozzolans in cement for concrete production. This assessment focused on the chemical composition of the materials, as pozzolanic reactivity—a key factor in improving concrete performance—is strongly linked to the content of pozzolanic oxides. The percentages of pozzolanic oxides can be derived from the elemental composition data obtained using X-ray fluorescence (XRF), a widely used technique for determining the chemical composition of materials. According to ASTM C618-22, a material qualifies as a pozzolan if the combined content of silicon dioxide (SiO2), aluminum oxide (Al2O3), and iron oxide (Fe2O3)—collectively referred to as pozzolanic oxides—is equal to or greater than 50% by mass (i.e., SiO2% + Al2O3% + Fe2O3% ≥ 50% [42]. This criterion represents a revision from earlier editions of the standard, which required a higher threshold of 70%. As shown in Figure 2, 20 out of the 35 ABAs analyzed met the minimum standard, qualifying them for further evaluation.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the Combined Pozzolanic Oxide Contents of Agricultural Biomass Ashes (ABAs) with the ASTM C618-22 Minimum Requirement for Natural Pozzolans.

Step 2: Evaluation of ABAs for Structural Concrete Applications

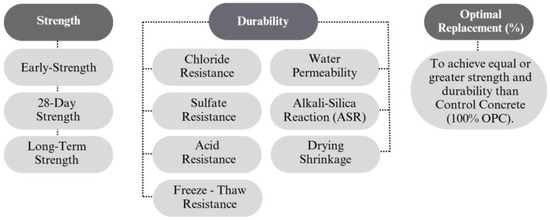

ABAs that passed the initial screening were further evaluated for their suitability in structural concrete using a decision matrix. The original framework included four criteria—strength, durability, carbon emission reduction, and economic value. However, due to limited data for the latter two, they were replaced with the criterion of optimal replacement percentage. This serves as a proxy, based on the premise that higher replacement levels typically indicate both lower carbon emissions and greater cost-effectiveness. As a result, the evaluation focused on three key criteria: strength, durability, and optimal replacement level. Detailed subcategories were developed for both strength and durability, as illustrated in Figure 3. These criteria were chosen to address sustainability goals while ensuring essential performance characteristics for structural applications.

Figure 3.

Evaluation Criteria for Agricultural Biomass Ash (ABA) as Partial Cement Replacement.

Table 3, which is a design matrix, presents the evaluation results for 20 ABAs evaluated using the finalized criteria.

Table 3.

Design Matrix for Evaluating ABA-Blended Cement Concrete.

A consistent and objective scoring system was applied across all criteria using the design matrix to facilitate a comprehensive evaluation, as shown in Table 4. For scoring purposes, a value of zero was assigned to criteria marked as N/A (data not available) to ensure consistency and comparability across all materials. These gaps reflect current limitations in the available literature and highlight opportunities for future research.

Table 4.

Scoring System for the Design Matrix.

3. Results and Discussion

The scoring system described in the methodology was applied to the data presented in Table 3 to identify the most promising agricultural biomass ashes (ABAs) for use as supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) in concrete production. Based on this evaluation, the top three candidates for partial cement replacement are rice husk ash (RHA), sugarcane bagasse ash (SCBA), and wheat straw ash (WSA). These materials are depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Top Three Agricultural Biomass Ash (ABA) Candidates for Partial Cement Replacement.

Concrete mixtures incorporating these ABAs demonstrated superior compressive strength and durability compared to those with other ABAs. Furthermore, these materials exhibited significant potential for reducing the carbon footprint of concrete production. The following sections provide a comprehensive analysis of the ABAs, encompassing their origins, performance characteristics, and sustainability advantages.

3.1. Global Agricultural (Rice, Wheat, Sugarcane) Production

Figure 5 illustrates the global production volumes of rice, sugarcane, and wheat. As previously discussed, the top four countries in CO2 emissions from cement production—China, India, Vietnam, and the United States—are also among the leading producers of these key agricultural products. Specifically, China and India consistently rank within the top three for all three crops. Vietnam and the United States are among the top five producers of rice and wheat, respectively. Additionally, the United States ranks 9th in sugarcane production and 13th in rice production.

Figure 5.

Global Agricultural (Rice, Wheat, and Sugarcane) Production by Country, adapted from [162,163,164].

3.2. Chemical and Physical Characteristics of the Selected ABAs

The effectiveness of ABAs as pozzolanic materials is primarily governed by their chemical and physical characteristics [104].

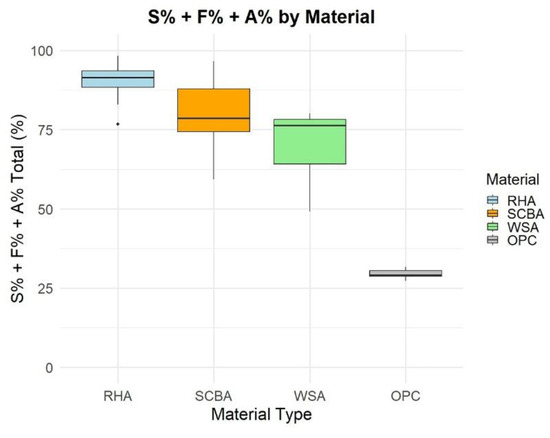

Figure 6 illustrates the combined content of the key pozzolanic oxides—SiO2, Al2O3, and Fe2O3, collectively expressed as S% + A% + F%—for the selected ABAs in comparison with ordinary Portland cement (OPC). The ABAs exhibit significantly higher combined oxide contents than OPC, and all values comply with the requirements of ASTM C618-22 for pozzolanic materials.

Figure 6.

Combined Content of SiO2% (S%) + Al2O3% (A%) + Fe2O3% (F%) in Selected Agricultural Biomass Ashes (ABAs) and Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC).

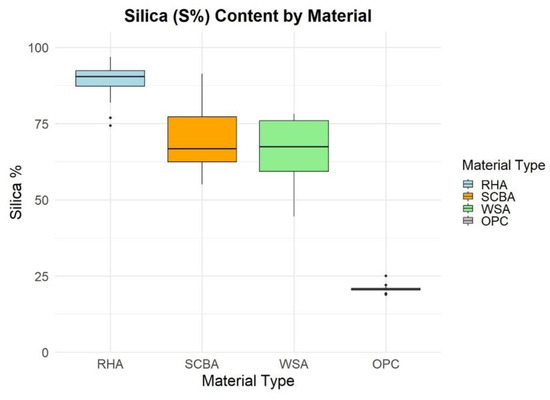

A higher combined content, particularly of silica (SiO2), is indicative of greater pozzolanic reactivity. During the hydration of OPC, tricalcium silicate (C3S) and dicalcium silicate (C2S) react with water to form calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) and calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H), the latter being the primary contributor to concrete strength. Figure 7 shows that the ABAs, especially RHA, contain significantly higher silica content than OPC, facilitating additional secondary C-S-H formation through pozzolanic reactions. This leads to enhanced compressive strength, reduced permeability, and improved chemical durability over time [165].

Figure 7.

SiO2% (S%) Content of Selected Agricultural Biomass Ashes (ABAs) and Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC).

Table 5 presents the full chemical composition of the selected ABAs compared to OPC.

Table 5.

Chemical Characteristics of the Selected Agricultural Biomass Ashes (ABAs).

While the pozzolanic oxides contribute positively to performance, other constituents—such as chloride (Cl−), sodium oxide (Na2O), potassium oxide (K2O), sulfur trioxide (SO3), and loss on ignition (LOI)—can adversely affect concrete properties. Chloride ions accelerate steel reinforcement corrosion, while Na2O and K2O increase the total alkali content and pore solution pH, thereby heightening the risk of alkali–silica reaction (ASR) [144]. ASTM C150 [172] recommends that total alkalis—calculated as (Na2O + 0.658 × K2O)—should not exceed 0.6%. As this threshold is surpassed in the selected ABAs, mitigation strategies may be necessary, which are discussed in the following sections of this study.

In addition, ASTM C618-22 limits SO3 content to a maximum of 5% to prevent the formation of deleterious ettringite. All selected ABAs fall within this permissible range. The standard also sets a preferred LOI value below 6%, although values up to 12% are acceptable if supported by adequate performance records or laboratory evidence [42]. When LOI exceeds these limits, pre-treatment or processing may be required, as elevated LOI can increase water demand and negatively impact concrete performance [9].

The physical characteristics that influence the performance of ABA-blended cement concrete include morphology, particle size, fineness, specific surface area, specific gravity, and color. Table 6 presents these properties for the selected ABAs in comparison with ordinary Portland cement (OPC). The influence of each parameter is discussed in the following sections.

Table 6.

Physical Characteristics of the Selected Agricultural Biomass Ashes (ABAs).

The morphology and microstructure of OPC and the selected ABAs exhibit notable differences that influence concrete performance. OPC consists of irregular, angular particles [176] with the main crystalline phases including C3S, C2S, C3A, and C4AF [177]. Upon hydration, it forms amorphous or poorly crystalline C–S–H gel—the main binding phase—alongside crystalline calcium hydroxide (CH) and ettringite [177,178], which exhibit sheet-like and needle-like morphologies, respectively [178]. These hydration products contribute to pore filling and microstructural densification [177].

In contrast, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis shows that RHA exhibits either spherical [126] or irregular particle shapes with a porous, cellular [9,10], or honeycomb structure of varying pore sizes [126]. WSA consists of irregular and occasionally elongated particles [9], with rough surfaces [179], porous inner tubules, and a dense outer layer characterized by compact channels and the absence of pores [112]. SCBA consists of diverse particle morphologies—including spherical, prismatic, and fibrous forms—with a rough texture and porous structure [9,142].

Despite these differences, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis shows that all three ABAs are primarily composed of amorphous silica, with minor crystalline phases such as quartz and cristobalite [52,173,180]. SCBA additionally contains traces of calcite, corundum, and hematite [140]. The reactive amorphous silica in these ashes undergoes pozzolanic reactions with CH to form additional C–S–H gel. Simultaneously, their fine and porous particles act as microfillers, refining the pore structure and enhancing packing density, which contributes to overall microstructural densification [106,167,173].

3.3. Performance of the Selected ABA-Blended Cement Concrete

3.3.1. Fresh Properties of the Selected ABA-Blended Cement Concrete

Workability

The incorporation of ABAs as partial replacements for OPC generally reduces workability due to their physical and chemical characteristics. As shown in Table 6, the specific gravity of all ABAs is lower than that of OPC, primarily due to their inherently porous structure. This increased porosity raises the total binder volume, affecting the water demand of the mix [9]. Additionally, the hygroscopic nature and high surface area of ABA particles—especially finer particles—enhance water absorption, further decreasing workability [11,104]. These fine particles possess a significantly larger specific surface area, requiring more water for proper wetting and dispersion. Moreover, the irregular shapes [111,142] and rough textures of ABA particles, such as those in SCBA, reduce the flowability of the concrete, resulting in a stiffer mix [142]. Another influencing factor is the LOI content of ABAs. Higher LOI values are associated with lower specific gravity and increased water absorption, both of which negatively impact workability [9,11].

Improving Workability

Despite the challenges associated with reduced workability in concrete incorporating ABAs, some studies have reported that, under optimized conditions, the workability of ABA-blended concrete can be significantly improved—and in some cases, may even exceed that of control concrete (CC) [20]. These enhancements can reduce the overall water demand of the mix and eliminate the need for chemical admixtures such as superplasticizers. Several optimization strategies have been identified in the literature, including:

Modification of ABA’s physical properties: The pre-treatment of ABAs to remove fibrous materials prior to mixing enhances the homogeneity of the blend and contributes to a further reduction in flow resistance [20]. In addition to pre-treatment, the specific physical characteristics of ABAs—such as particle morphology, density, size, and distribution—can significantly influence the workability of concrete [20,126,173].

Sobuz et al. [20] demonstrated that incorporating up to 20% SCBA led to an overall improvement in workability by approximately 40–50%. This enhancement is attributed to the favorable physical properties of SCBA, including its spherical, uniform, and regular particle shape, which minimizes internal friction and particle interlocking, thereby promoting better flow. Furthermore, the glassy and smooth surface texture of SCBA particles facilitates easier movement within the concrete matrix. Similarly, Tian et al. [126] reported that grinding RHA for about 30 min resulted in particles with high surface area and optimal workability. This was largely due to the spherical morphology of RHA particles, which produces a ball-bearing effect that reduces internal friction and enhances flowability.

The lower density of ABAs, such as SCBA, compared to that of cement, also plays a crucial role in improving workability. This reduced density leads to a decrease in the fresh concrete’s overall density, an increase in entrained air content, and a reduction in internal resistance—all of which contribute to enhanced flow properties. These characteristics also highlight SCBA’s potential use in lightweight concrete applications [20].

Additional insights from Givi et al. [173] reveal that coarser RHA particles, with an average size of approximately 95 µm, can enhance workability at a water-to-binder ratio of 0.4. This improvement is primarily due to the lower water demand associated with coarser RHA. The ash particles adsorb onto the surfaces of cement grains, reducing flocculation and encouraging a more uniform dispersion. Moreover, RHA contributes to optimizing the overall particle size distribution, which increases the packing density of solids and decreases void content, ultimately reducing the amount of water required to achieve the desired level of workability.

Modification of mix design parameters for the ABA-blended cement concrete: Optimizing the replacement level of ABA and the water-to-binder (w/b) ratio can significantly enhance the workability of concrete. For instance, incorporating RHA at replacement levels up to 5% [44], or within the range of 5–10%, in combination with a w/b ratio of 0.53, has been shown to increase slump values by approximately 8–17% compared to CC [11]. Similarly, a study by Sudeep et al. [179] utilized response surface methodology (RSM) to determine optimal mix parameters. Their findings indicated that a w/b ratio of 0.45 combined with 10.12% WSA resulted in enhanced workability while maintaining adequate mechanical strength. In another study, Priya [146] reported that replacing cement with SCBA at levels up to 25%, in conjunction with a w/b ratio of 0.5, significantly improved workability. Notably, at the 25% replacement level, the concrete achieved a slump of 160 mm, compared to 70 mm for the control mix, highlighting a substantial improvement in flowability.

Initial and Final Setting Times

The initial and final setting times of ABA-blended cement concrete were longer than those of the control concrete (CC) at all levels of ABA replacement [21,52,119,142]. This delay is attributed to the reduced content of tricalcium aluminate (C3A) in the mixture and the presence of unburned carbon, as well as sulfur trioxide (SO3), which is specifically associated with the SCBA [142].

Studies report that replacing cement with up to 20% SCBA or RHA increases both initial and final setting times; however, all values remain within ASTM C191 limits (initial setting time > 45 min; final setting time < 375 min). Kazmi et al. [144] observed that the initial setting time increased from 97 min (control) to 114 min for 10% SCBA and to 187 min for 20% SCBA. Similarly, the final setting time increased from 189 min (control) to 234 min at 10% SCBA and to 287 min at 20% SCBA. Abbas et al. [119] reported that replacing cement with 10% RHA extended the initial setting time from 89 min (OPC) to 105 min, whereas 20% RHA increased it to 127 min. The final setting time increased from 159 min (OPC) to 179 min at 10% RHA and to 198 min at 20% RHA. Ahmad et al. [106] found that incorporating 21% WSA increased the initial and final setting times by 46.3% and 47.6%, respectively, compared to the control; however, these values also remained within acceptable operational thresholds.

3.3.2. Compressive Strength (CS) of the Selected ABA-Blended Cement Concrete

RHA replacement at 5–20% by cement weight has been shown to enhance the compressive strength (CS) of concrete, with improvements ranging from 2.4% to 18.7% compared to control concrete (CC) at 28 days [44]. Notably, finely ground RHA at a 10% replacement level produced a significant increase in CS of 30.8% relative to CC at the same curing age [125]. Furthermore, a higher replacement level of 30% RHA yielded CS values comparable to those of the control mix at 28 days [11].

Similarly, incorporating SCBA within the 5–15% range resulted in CS improvements of 3.72% to 20.81% compared to the CC at 28 days [167]. Replacement with SCBA up to 20% could further increase CS; however, exceeding this threshold negatively impacted strength relative to the control mix at 28 days [21,146]. Likewise, using WSA as a cement replacement between 5% and 15% enhanced CS, with peak performance observed at 10% replacement. Beyond 15%, WSA incorporation caused a decline in CS compared to CC at 28 days [104]. Notably, with appropriate treatment methods, WSA replacement could be increased to 20%, resulting in a 10.98% higher CS than CC at 28 days (from 60.1 MPa for CC to 66.7 MPa with 20% WSA) [169].

Treatment Methods to Improve CS of ABA-Blended Cement Concrete

The following treatment methods can enhance the CS of ABA-blended concrete:

- Sieving: Sieving removes oversized particles and separates particles by size (ranging from 75 to 2000 μm). This process improves the quality of ABAs by eliminating impurities and reducing carbon content and LOI. Additionally, sieving increases the concentration of pozzolanic oxides, thereby enhancing reactivity and potentially improving the compressive strength of concrete [142].

- Burning: Controlled burning conditions not only reduce carbon content and LOI but also increase the concentration of pozzolanic oxides [142], particularly amorphous silica [11]. Achieving a higher proportion of amorphous silica depends critically on the optimal temperature range and duration, as outlined below:

- ○

- RHA: Burning in the range of 570–670 °C for 5 h [104], with 650 °C for 60–80 min results in the highest amount of silica in amorphous form [11,126].

- ○

- WSA: Burning in the range of 500–600 °C for 2 h, specifically at 600 °C for 2 h [112] or at 550 °C for 4–5 h, results in the highest amount of amorphous silica [14,108].

- ○

- SCBA: Burning in the range of 450–650 °C for 1–3 h, with 550 °C for 1 h, results in the highest amount of silica in amorphous form [166].

However, exceeding a certain temperature threshold causes the transformation of amorphous silica into crystalline silica, which negatively impacts its pozzolanic activity [116].

- Water or Chemical Treatment: If necessary, water or chemical treatment is recommended. Water washing is particularly effective for the removal of soluble salts, including chlorides, sulfates, and alkalis (e.g., Na and K). For heavy metal removal, more advanced methods—such as chemical washing (using hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, or phosphoric acid), electro-dialytic remediation (with citric acid, ammonium citrate, or ammonia), and ammonium acetate extraction—have also been shown to be effective [181].

- Grinding: The reduction in particle size of ABAs through grinding significantly enhances their pozzolanic reactivity by increasing the surface area of the finer particles, thereby providing more active sites for chemical reactions [9]. In the case of RHA, although grinding reduces its average particle size, the surface area is largely governed by its intrinsic multilayered, angular, and microporous structure rather than particle size alone. This complex morphology contributes to its high reactivity [125].

In addition, the particle size distribution of ABAs, which affects their pozzolanic activity [170], along with the water-to-binder (w/b) ratio, can significantly influence the CS of ABA-blended cement concrete. Typically, the w/b ratio ranges from 0.35 to 0.55, with higher w/b ratios generally reducing the mechanical performance of the concrete. However, this adverse effect can be alleviated by incorporating finely ground ABAs, which enhance the microstructural properties of the material, thereby helping to maintain the desired strength and durability [104]. While ultrafine ABA is more effective at improving CS than coarser particles, it tends to reduce workability compared to coarser ABA-blended cement concrete at the same w/b ratio. This reduction in workability is mainly due to the increased specific surface area of the ultrafine particles, which raises the water demand of the concrete mixture [173].

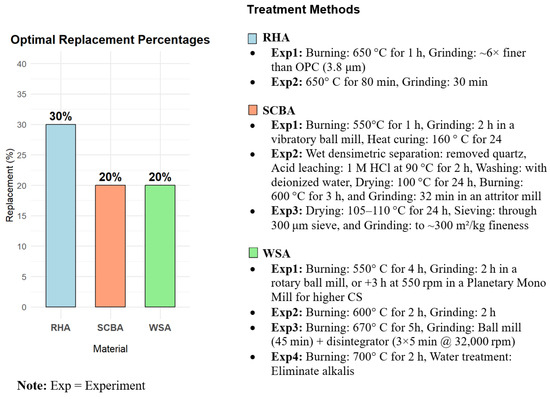

Optimizing ABA Replacement Percentage Based on Concrete CS

Table 3 presents the optimal replacement level ranges of the selected ABAs in concrete, which are required to achieve CS equal to or greater than that of the CC. Based on these results, the highest reported replacement percentages are 30% for RHA and 20% for both WSA and SCBA. The rationale for selecting the highest feasible replacement level for each material is to maximize the reduction in carbon emissions while still meeting the strength requirements for structural applications. Figure 8 illustrates the recommended maximum replacement levels along with the corresponding treatment methods that enhance their effectiveness. It is important to note that these recommendations are based on the 28-day CS of concrete incorporating the selected ABAs. However, due to the continued pozzolanic activity of these materials, there is potential for further strength development at later curing ages compared to the CC [142].

Figure 8.

Maximum Agricultural Biomass Ash (ABA) Replacement Percentages in Cement with Corresponding Treatment Methods for Compressive Strength (CS) Compliance [11,21,52,108,112,126,145,166,169].

3.3.3. Durability Properties of the Selected ABA-Blended Cement Concrete

The durability improvement observed from incorporating the selected ABAs into concrete is attributed not only to their pozzolanic activity—which enhances the formation of additional C-S-H gel—but also to their finer particle size compared to OPC. This finer particle size contributes to the filling effect by refining the pore structure and reducing porosity [142]. Table 7 presents the highest reported replacement percentages of the selected ABAs in cement that satisfy durability requirements.

Table 7.

Maximum Agricultural Biomass Ash (ABA) Replacement Percentages in Cement for Durability Compliance.

3.4. Environmental Impact of the Selected ABA-Blended Cement Concrete

Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) production is a major contributor to fossil-based carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and significantly depletes non-renewable raw materials, such as limestone and clay. In contrast, agricultural biomass ashes (ABAs) are derived from renewable agricultural residues. According to Khanna et al. [182], the production of ABAs involves the controlled combustion of these residues, generating ash and releasing CO2 that is classified as biogenic—originating from carbon absorbed by plants during their growth cycle. As a result, the net increase in atmospheric CO2 is negligible, since these emissions are part of the natural carbon cycle.

Importantly, the CO2 emissions associated with ABAs are substantially lower than those from OPC; for instance, sugarcane bagasse ash (SCBA) emits approximately 7.5 times less CO2 than OPC [142]. Moreover, the utilization of agricultural waste as an alternative energy source to replace conventional fossil fuels, such as coal or oil, offers additional environmental benefits by reducing reliance on non-renewable energy sources. The ash generated through this process can be used as a partial cement replacement in concrete mixtures, thereby supporting net-zero carbon emission targets and enhancing sustainability within the construction sector.

4. Conclusions

This review systematically evaluated 35 agricultural biomass ashes (ABAs) as supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) for partial cement replacement, aiming to reduce CO2 emissions while maintaining or enhancing concrete performance. Twenty ABAs were identified as chemically suitable through a pozzolanic oxide screening chart and further evaluated using a concrete performance matrix integrating strength, durability, and optimal replacement levels. Rice husk ash (RHA), sugarcane bagasse ash (SCBA), and wheat straw ash (WSA) emerged as the most promising SCMs.

Concrete incorporating these ABAs demonstrated improved compressive strength and enhanced durability (resistance to chloride ingress, sulfate attack, acid exposure, alkali–silica reaction, and drying shrinkage) compared with control concrete (100% OPC), while maintaining acceptable workability. Their pozzolanic activity, combined with chemical and physical properties and targeted retreatment methods, contributed to these performance improvements. Recommended replacement levels are 30% for RHA and 20% for SCBA and WSA, with higher levels feasible for most durability criteria. Global availability analyses confirmed their suitability, particularly in regions with high cement-related CO2 emissions.

Remaining gaps include limited durability data for some of the 20 ABAs, particularly regarding freeze–thaw resistance; however, these ABAs are expected to enhance freeze–thaw performance through pore refinement, reduced air voids, and decreased permeability. Future research should use machine learning to optimize the blend of multiple ABAs to develop a novel SCM, with predictions validated through laboratory testing and economic assessment. By integrating chemical, physical, and performance data into a structured framework, this review positions ABAs as credible, scalable SCMs for sustainable concrete production.

Author Contributions

L.M. conceived and designed the study, developed the methodology, implemented the software, conducted the investigation and formal analysis, curated the data, visualized the results, and wrote the original draft. T.G. and C.B.F. provided validation, supervision, and feedback on manuscript review and editing. Project administration was handled by L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bigger Climate Action Emerging in Cement Industry. Available online: https://unfccc.int/news/bigger-climate-action-emerging-in-cement-industry (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Endale, S.A.; Taffese, W.Z.; Vo, D.-H.; Yehualaw, M.D. Rice husk ash in concrete. Sustainability 2022, 15, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cement. Available online: https://sciencebasedtargets.org/sectors/cement (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Lavagna, L.; Nisticò, R. An insight into the chemistry of cement—A review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 13, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telschow, S.; Frandsen, F.; Theisen, K.; Dam-Johansen, K. Cement Formation A Success Story in a Black Box: High Temperature Phase Formation of Portland Cement Clinker. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 10983–11004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunuweera, S.; Rajapakse, R. Cement types, composition, uses and advantages of nanocement, environmental impact on cement production, and possible solutions. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 2018, 4158682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annual CO2 Emissions from Cement. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/annual-co2-cement (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Juenger, M.C.; Snellings, R.; Bernal, S.A. Supplementary cementitious materials: New sources, characterization, and performance insights. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 122, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charitha, V.; Athira, V.; Jittin, V.; Bahurudeen, A.; Nanthagopalan, P. Use of different agro-waste ashes in concrete for effective upcycling of locally available resources. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 285, 122851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao-Lung, H.; Le Anh-Tuan, B.; Chun-Tsun, C. Effect of rice husk ash on the strength and durability characteristics of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 3768–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Rajagopal, K.; Thangavel, K. Rice husk ash blended cement: Assessment of optimal level of replacement for strength and permeability properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 1675–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bheel, N.; Ali, M.O.A.; Kirgiz, M.S.; de Sousa Galdino, A.G.; Kumar, A. Fresh and mechanical properties of concrete made of binary substitution of millet husk ash and wheat straw ash for cement and fine aggregate. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 13, 872–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Aboshio, A.; Aliyu, M. Performance of millet husk ash in self compacting concrete. Niger. J. Technol. 2021, 40, 1010–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.N.; Murtaza, T.; Shahzada, K.; Khan, K.; Adil, M. Pozzolanic potential and mechanical performance of wheat straw ash incorporated sustainable concrete. Sustainability 2019, 11, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Qiao, H.; Li, Y.; Shu, X.; Cui, L. Effect of highland barley straw ash admixture on properties and microstructure of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 315, 125802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruviaro, A.S.; dos Santos Lima, G.T.; Silvestro, L.; Barraza, M.T.; Rocha, J.C.; de Brito, J.; Gleize, P.J.P.; Pelisser, F. Characterization and investigation of the use of oat husk ash as supplementary cementitious material as partial replacement of Portland cement: Analysis of fresh and hardened properties and environmental assessment. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 363, 129762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alogla, S.M.; Almusayrie, A.I. Compressive strength evaluation of concrete with palm tree ash. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2022, 10, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, S.; Sharma, R.P. Experimental investigation on strength and water permeability of mortar incorporate with rice straw ash. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2016, 9696505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Patel, M. Strength and durability performance of rice straw ash-based concrete: An approach for the valorization of agriculture waste. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 9995–10012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobuz, M.H.R.; Datta, S.D.; Jabin, J.A.; Aditto, F.S.; Hasan, N.M.S.; Hasan, M.; Zaman, A.A.U. Assessing the influence of sugarcane bagasse ash for the production of eco-friendly concrete: Experimental and machine learning approaches. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahurudeen, A.; Kanraj, D.; Dev, V.G.; Santhanam, M. Performance evaluation of sugarcane bagasse ash blended cement in concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 59, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.J.; Aslam, M.; Ahmad, S. Utilization of sugarcane bagasse ash as cement replacement for the production of sustainable concrete–A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 270, 121371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijani, M.A.; Ajagbe, W.O.; Agbede, O.A. Combined reusing of sorghum husk ash and recycled concrete aggregate for sustainable pervious concrete production. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 343, 131015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijani, M.; Ajagbe, W.; Ganiyu, A.; Agbede, O. Sustainable pervious concrete incorporating sorghum husk ash as cement replacement. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 640, 012051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebisi, S.; Igba, T.; Oniyide, D. Performance evaluation of cashew nutshell ash as a binder in concrete production. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2019, 11, e00293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.A.; Javed, U.; Khushnood, R.A. Eco-friendly utilization of corncob ash as partial replacement of sand in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 195, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akindahunsi, A.; Ogune, C.; Ayodele, A.; Fajobi, A.; Olajumoke, A. Evaluation of the performance of corncob ash in cement mortars. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 2022, 7, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marthong, C. Sawdust ash (SDA) as partial replacement of cement. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2012, 2, 1980–1985. [Google Scholar]

- Raheem, A.; Olasunkanmi, B.; Folorunso, C. Saw dust ash as partial replacement for cement in concrete. Organ. Technol. Manag. Constr. Int. J. 2012, 4, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darweesh, H.; El-Suoud, M.A. Saw dust ash substitution for cement pastes—Part I. Am. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2017, 13, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.I.; Jan, S.R.; Peer, J.A.; Nazir, S.A.; Mohammad, K.F. Partial replacement of cement by saw Dust Ash in concrete a sustainable Approach. Int. J. Eng. Res. Dev. 2015, 11, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Utsev, J.; Taku, J. Coconut shell ash as partial replacement of ordinary Portland cement in concrete production. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2012, 1, 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kanojia, A.; Jain, S.K. Performance of coconut shell as coarse aggregate in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 140, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranatunga, K.S.; del Rey Castillo, E.; Toma, C.L. Evaluation of the optimal concrete mix design with coconut shell ash as a partial cement replacement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 401, 132978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebaw, G.; Bewket, B.; Getahun, S. Experimental investigation on effect of partial replacement of cement with bamboo leaf ash on concrete property. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6468444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacuan, C.N.; Abellana, V.Y.; Canseco, H.A.R. Assessment and evaluation of blended cement using bamboo leaf ash BLASH against corrosion. Civ. Eng. J. 2021, 7, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, F.K., Jr.; Wally, G.B.; Magalhães, F.C.; de Pires, M.M.; Kulakowski, M.P.; do Nascimento, C.D.; Flores, W.H.; Avellaneda, C.A.O. Effects of bamboo leaf ashes on concrete compressive strength, water absorption, and chloride penetration. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, S.; Ali, M.; Buller, A.S.; Bheel, N.; Gamil, Y.; Najeh, T.; Deifalla, A.F.; Ragab, A.E.; Almujibah, H.R. Effect of banana tree leaves ash as cementitious material on the durability of concrete against sulphate and acid attacks. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, J.C.; Lucena, L.F.; Henriques, G.F.; Ferreira, R.L.; dos Anjos, M.A. Use of banana leaf ash as partial replacement of Portland cement in eco-friendly concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 346, 128467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanning, R.C.; Portella, K.F.; Bragança, M.O.; Bonato, M.M.; dos Santos, J.C. Banana leaves ashes as pozzolan for concrete and mortar of Portland cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 54, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.H.; Law, D.W.; Gunasekara, C.; Sobuz, M.H.R.; Rahman, M.N.; Habib, M.A.; Sabbir, A.K. Assessing the Influence of Banana Leaf Ash as Pozzolanic Material for the Production of Green Concrete: A Mechanical and Microstructural Evaluation. Materials 2024, 17, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C618–22; Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Sandhu, R.K.; Siddique, R. Influence of rice husk ash (RHA) on the properties of self-compacting concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 153, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaed, M.M.; Al Mufti, R.L. The Effects of Rice Husk Ash as Bio-Cementitious Material in Concrete. Constr. Mater. 2024, 4, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bheel, N.; Memon, F.A.; Meghwar, S.L. Study of fresh and hardened properties of concrete using cement with modified blend of millet husk ash as secondary cementitious material. Silicon 2021, 13, 4641–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoon, A.; Bassuoni, M.; Ghazy, A. Assessment of Oat Husk Ash from Cold Climates as a Supplementary Cementitious Material. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2025, 37, 04025371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Walia, R. Life cycle assessment of sustainable concrete by utilizing groundnut husk ash in concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 1910–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogork, E.N.N.; Uche, O.A.; Elinwa, A. Characterization of Groundnut husk ash (Gha) admixed with Rice husk ash (Rha) in cement paste and concrete. Adv. Mater. Res. 2015, 1119, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedefaw, A.; Worku Yifru, B.; Endale, S.A.; Habtegebreal, B.T.; Yehualaw, M.D. Experimental investigation on the effects of coffee husk ash as partial replacement of cement on concrete properties. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 4175460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hareru, W.K.; Asfaw, F.B.; Ghebrab, T. Physical and chemical characterization of coffee husk ash effect on partial replacement of cement in concrete production. Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. 2022, 13, 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audu Vincent, E.; Mamman Yakubu, W. Use of Cocoa Pod Husk Ash as Admixture in Concrete. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 2013, 2, 3781–3793. [Google Scholar]

- Jankovský, O.; Pavlikova, M.; Sedmidubský, D.; Bouša, D.; Lojka, M.; Pokorný, J.; Záleská, M.; Pavlík, Z. Study on pozzolana activity of wheat straw ash as potential admixture for blended cements. Ceram. Silik 2017, 61, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, M.; Douzane, O.; Le, A.T.; Promis, G.; Langlet, T. Characterization and comparison of hygric properties of rape straw concrete and hemp concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 102, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Qiao, H.; Li, Y.; Shu, X.; Li, W. Correlation evaluation between water resistance and pore structure of magnesium oxychloride cement mixed with highland barley straw ash. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2022, 34, 04022259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Qiao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Cui, L. Early-age performance and mechanism of magnesium oxychloride cement mortar mixed with highland barley straw ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 401, 132979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šupić, S.; Malešev, M.; Radonjanin, V.; Bulatović, V.; Milović, T. Reactivity and pozzolanic properties of biomass ashes generated by wheat and soybean straw combustion. Materials 2021, 14, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Yan, C.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, G.; Shi, W. Utilization of straw ash as a partial substitute for ordinary Portland cement in concrete. BioResources 2024, 19, 4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakeem, I.Y.; Amin, M.; Zeyad, A.M.; Tayeh, B.A.; Maglad, A.M.; Agwa, I.S. Effects of nano sized sesame stalk and rice straw ashes on high-strength concrete properties. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 370, 133542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoğan, O.; Binici, H.; Ortlek, E. Durability of concrete made by partial replacement of fine aggregate by colemanite and barite and cement by ashes of corn stalk, wheat straw and sunflower stalk ashes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 106, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerbănoiu, A.A.; Grădinaru, C.M.; Cimpoeșu, N.; Filipeanu, D.; Șerbănoiu, B.V.; Cherecheș, N.C. Study of an ecological cement-based composite with a sustainable raw material, sunflower stalk ash. Materials 2021, 14, 7177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memon, S.A.; Khan, S.; Wahid, I.; Shestakova, Y.; Ashraf, M. Evaluating the Effect of Calcination and Grinding of Corn Stalk Ash on Pozzolanic Potential for Sustainable Cement-Based Materials. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 2020, 1619480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, S.; Hamdy, Y.; Abdelraouf, E.-S.; Shazly, M. Towards sustainable concrete: Cement replacement using Egyptian cornstalk ash. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agwa, I.S.; Omar, O.M.; Tayeh, B.A.; Abdelsalam, B.A. Effects of using rice straw and cotton stalk ashes on the properties of lightweight self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 235, 117541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Zeyad, A.M.; Tayeh, B.A.; Agwa, I.S. Effects of nano cotton stalk and palm leaf ashes on ultrahigh-performance concrete properties incorporating recycled concrete aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 302, 124196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bheel, N.; Mahro, S.K.; Adesina, A. Influence of coconut shell ash on workability, mechanical properties, and embodied carbon of concrete. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 5682–5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adajar, M.A.; Galupino, J.; Frianeza, C.; Aguilon, J.F.; Sy, J.B.; Tan, P.A. Compressive strength and durability of concrete with coconut shell ash as cement replacement. Geomate J. 2020, 18, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurt, Ü.; Bekar, F. Comparative study of hazelnut-shell biomass ash and metakaolin to improve the performance of alkali-activated concrete: A sustainable greener alternative. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 320, 126230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, Y.; Gökçe, H.; Durmaz, M. Physical and mechanical properties of cement containing regional hazelnut shell ash wastes. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano Martínez, L.; Font, A.; Mitsuuchi Tashima, M.; Monzó Balbuena, J.M.; Borrachero Rosado, M.V.; Bonifacio, T.; Paya Bernabeu, J.J. Almond-shell biomass ash (ABA): A greener alternative to the use of commercial alkaline reagents in alkali-activated cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 290, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Yeo, B.-L.; Markandeya, A.; Martínez, A.; Harvey, J.; Miller, S.A.; Nassiri, S. Transforming almond shell waste into high-value activators for low-carbon concrete: Life cycle assessment and technoeconomic analysis. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 105, 112547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebisi, S.; Olutoge, F.; Oyaotuderekumor, I.; Bankole, F.; Owamah, H.; Mazino, U. Effects of cashew nutshell ash on the thermal and sustainability properties of cement concrete. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, I.; Dirikolu, İ.; Gökçe, H. A regional supplementary cementitious material for the cement industry: Pistachio shell ash. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 124810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz, M.; Doğruyol, M. Pistachio Shell Ash in Agro-Waste Cement Composites: A Pathway to Low-Carbon Binders. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, J. A new supplementary cementitious material: Walnut shell ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 408, 133852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beskopylny, A.N.; Stel’makh, S.A.; Shcherban’, E.M.; Mailyan, L.R.; Meskhi, B.; Shilov, A.A.; Chernil’nik, A.; El’shaeva, D. Effect of walnut-shell additive on the structure and characteristics of concrete. Materials 2023, 16, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerihun, B.; Yehualaw, M.D.; Vo, D.-H. Effect of agricultural crop wastes as partial replacement of cement in concrete production. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5648187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikary, S.K.; Ashish, D.K.; Rudžionis, Ž. A review on sustainable use of agricultural straw and husk biomass ashes: Transitioning towards low carbon economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udoeyo, F.F.; Dashibil, P.U. Sawdust ash as concrete material. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2002, 14, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teker Ercan, E.E.; Andreas, L.; Cwirzen, A.; Habermehl-Cwirzen, K. Wood ash as sustainable alternative raw material for the production of concrete—A review. Materials 2023, 16, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, R. Utilization of wood ash in concrete manufacturing. Resources, conservation and Recycling 2012, 67, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amah, V.E.; Ugwoha, E.; Chukwuemeka, E. Effect of palm tree Leaf ash on the compressive strength of concrete and its workability. Int. J. Eng. Sci. (IJES) 2020, 9, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Asha, P.; Salman, A.; Kumar, R.A. Experimental study on concrete with bamboo leaf ash. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2014, 3, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Dhinakaran, G.; Chandana, G.H. Compressive Strength and Durability of Bamboo Leaf Ash Concrete. Jordan J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 10, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.H.P.; Tamashiro, J.R.; de Paiva, F.F.G.; dos Santos, L.F.; Teixeira, S.R.; Kinoshita, A.; Antunes, P.A. Bamboo leaf ash for use as mineral addition with Portland cement. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 42, 102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.C.; Sales, C.P. Influence of calcining temperature on the pozzolanic characteristics of elephant grass ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 73, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.C.; Sales, C.P. Pozzolanic activity of elephant grass ash and its influence on the mechanical properties of concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 55, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, E.Y.; Frías, M.; Santos, S.F.; Rodrigues, M.S.; de la Villa, R.V.; Rodriguez, O.; Junior, H.S. Investigating the possible usage of elephant grass ash to manufacture the eco-friendly binary cements. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 116, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Ye, G.; De Schutter, G. Utilization of miscanthus combustion ash as internal curing agent in cement-based materials: Effect on autogenous shrinkage. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 207, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, Q.; Brouwers, H. Acoustic performance and microstructural analysis of bio-based lightweight concrete containing miscanthus. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 157, 839–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, A.A.E.; Shafiq, N.; Nuruddin, M.F.; Memon, F.A. Compressive strength and microstructure of sugar cane bagasse ash concrete. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2014, 7, 2569–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Arbili, M.M.; Alabduljabbar, H.; Deifalla, A.F. Concrete made with partially substitution corn cob ash: A review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesanya, D.; Raheem, A. A study of the workability and compressive strength characteristics of corn cob ash blended cement concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakeem, I.Y.; Agwa, I.S.; Tayeh, B.A.; Abd-Elrahman, M.H. Effect of using a combination of rice husk and olive waste ashes on high-strength concrete properties. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeh, B.A.; Hadzima-Nyarko, M.; Zeyad, A.M.; Al-Harazin, S.Z. Properties and durability of concrete with olive waste ash as a partial cement replacement. Adv. Concr. Constr. 2021, 11, 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Raheem, S.; Arubike, E.; Awogboro, O. Effects of cassava peel ash (CPA) as alternative binder in concrete. Int. J. Constr. Res. Civ. Eng. 2020, 1, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Salau, M.A.; Ikponmwosa, E.E.; Olonode, K.A. Structural strength characteristics of cement-cassava peel ash blended concrete. Civ. Environ. Res. 2012, 2, 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Olatokunbo, O.; Anthony, E.; Rotimi, O.; Solomon, O.; Tolulope, A.; John, O.; Adeoye, O. Assessment of strength properties of cassava peel ash-concrete. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 965–974. [Google Scholar]

- Nerusu, V.S.R.; Padavala, S.S.A.B.; Krishna, G.S.; Loya, G.B. Experimental investigation on tobacco waste ash for sustainable development. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1086, 012057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, P.; Fragozo, R.; Vesga, S.; Gonzalez, M.; Hernandez, L.; Gamboa, I.D.; Delgado, J. Tobacco waste ash: A promising supplementary cementitious material. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 2018, 9, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bheel, N.; Ali, M.O.A.; Shafiq, N.; Almujibah, H.R.; Awoyera, P.; Benjeddou, O.; Shittu, A.; Olalusi, O.B. Utilization of millet husk ash as a supplementary cementitious material in eco-friendly concrete: RSM modelling and optimization. Structures 2023, 49, 826–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onogwu, C.; Bukar, A.; Magaji, A. Influence of sulphate attack on compressive strength of millet husk ash as an alternative to silica fume in internally cured high performance concrete. Environ. Technol. Sci. J. 2024, 15, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Aboshio, A. Durability characteristics of millet hush ash: A study on self-compacting concrete. Tek. J. Sains Dan Teknol. 2021, 17, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bheel, N.; Ali, M.O.A.; Tafsirojjaman; Khahro, S.H.; Keerio, M.A. Experimental study on fresh, mechanical properties and embodied carbon of concrete blended with sugarcane bagasse ash, metakaolin, and millet husk ash as ternary cementitious material. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 5224–5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katman, H.Y.B.; Khai, W.J.; Bheel, N.; Kırgız, M.S.; Kumar, A.; Khatib, J.; Benjeddou, O. Workability, strength, modulus of elasticity, and permeability feature of wheat straw ash-incorporated hydraulic cement concrete. Buildings 2022, 12, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biricik, H.; Aköz, F.; Türker, F.; Berktay, I. Resistance to magnesium sulfate and sodium sulfate attack of mortars containing wheat straw ash. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Arbili, M.M.; Alqurashi, M.; Althoey, F.; Deifalla, A.F. Concrete made with partial substitutions of wheat straw ash: A review. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2023, 17, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akhras, N.M. Durability of wheat straw ash concrete to alkali-silica reaction. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Constr. Mater. 2013, 166, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.N.; Siffat, M.A.; Shahzada, K.; Khan, K. Influence of fineness of wheat straw ash on autogenous shrinkage and mechanical properties of green concrete. Crystals 2022, 12, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.A.; Javed, U.; Haris, M.; Khushnood, R.A.; Kim, J. Incorporation of wheat straw ash as partial sand replacement for production of eco-friendly concrete. Materials 2021, 14, 2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akhras, N.M. Durability of wheat straw ash concrete exposed to freeze–thaw damage. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Constr. Mater. 2011, 164, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bheel, N.; Ibrahim, M.H.W.; Adesina, A.; Kennedy, C.; Shar, I.A. Mechanical performance of concrete incorporating wheat straw ash as partial replacement of cement. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 2021, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.A.; Wahid, I.; Khan, M.K.; Tanoli, M.A.; Bimaganbetova, M. Environmentally friendly utilization of wheat straw ash in cement-based composites. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Bai, M.; Pang, J.; Liu, T. Performance degradation and damage model of rice husk ash concrete under dry–wet cycles of sulfate environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 59173–59189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Kamau, J. Performance of rice husk ash concrete in sulfate solutions. Res. Dev. Mater. Sci. 2017, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatveera, B.; Lertwattanaruk, P. Evaluation of nitric and acetic acid resistance of cement mortars containing high-volume black rice husk ash. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 133, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashem, F.; Amin, M.; El-Gamal, S. Improvement of acid resistance of Portland cement pastes using rice husk ash and cement kiln dust as additives. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2013, 111, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswathy, V.; Song, H.-W. Corrosion performance of rice husk ash blended concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2007, 21, 1779–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.J.; Kazmi, S.M.S.; Khitab, A.; Hassan, M. Utilization of rice husk ash to mitigate alkali silica reaction in concrete. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Multi-Disciplinary Conference, Gujrat, India, 19–20 December 2016; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, S.; Kazmi, S.M.; Munir, M.J. Potential of rice husk ash for mitigating the alkali-silica reaction in mortar bars incorporating reactive aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 132, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastaldini, A.; Da Silva, M.; Zamberlan, F.; Neto, C.M. Total shrinkage, chloride penetration, and compressive strength of concretes that contain clear-colored rice husk ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 54, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, D.; Li, X.; Lv, Y.; Wu, K. Autogenous shrinkage and hydration property of cement pastes containing rice husk ash. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Lv, B.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Yan, L.; Kasal, B. Freeze-thaw, chloride penetration and carbonation resistance of natural and recycled aggregate concrete containing rice husk ash as replacement of cement. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Duan, Z.; Liu, H.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C. Salt freezing-thawing damage evolution model based on the time-dependent hydration reaction incorporating rice husk ash and recycled coarse aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 440, 137179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Duan, Z.; Liu, C.; Yao, Y.; Liu, H.; Nasr, A.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Z. Performance optimisation and predictive modelling of rice husk ash recycled concrete under the coupled action of freeze-thaw cycles and chloride erosion: Experimental study and machine learning. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 481, 141467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeeb, G.A.; Mahmud, H.B. Study on properties of rice husk ash and its use as cement replacement material. Mater. Res. 2010, 13, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, E.; Frank Chen, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Zeng, W. Effects of rice husk ash on itself activity and concrete behavior at different preparation temperatures. Mater. Test. 2021, 63, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesanya, D.; Raheem, A. A study of the permeability and acid attack of corn cob ash blended cements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.; Mohammed, A.; Samson, D. Mechanical properties of concrete containing corn cob ash. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Stud. 2016, 3, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tumba, M.; Ofuyatan, O.; Uwadiale, O.; Oluwafemi, J.; Oyebisi, S. Effect of sulphate and acid on self-compacting concrete containing corn cob ash. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 413, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Șerbănoiu, A.A.; Grădinaru, C.M.; Muntean, R.; Cimpoeșu, N.; Șerbănoiu, B.V. Corn cob ash versus sunflower stalk ash, two sustainable raw materials in an analysis of their effects on the concrete properties. Materials 2022, 15, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuba, S.; Uche, O.; Haruna, S.; Mohammed, A. Durability properties of cement–saw dust ash (SDA) blended self compacting concrete (SCC). Niger. J. Technol. 2022, 41, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogork, E.; Ayuba, S. Influence of sawdust ash (SDA) as admixture in cement paste and concrete. IJISET–Int. J. Innov. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2014, 1, 736–743. [Google Scholar]

- Gwarah, L.; Akatah, B.; Onungwe, I.; Akpan, P. Partial replacement of ordinary portland cement with sawdust ash in concrete. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2019, 32, 43352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.V.; Swaroop, A.; Rao, P.K.R.; Bharath, C.N. Study on strength properties of coconut shell concrete. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. (IJCIET) 2015, 6, 42–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan, V.K.; Devi, S.A.; Manohari, S.; Santha, M.M. Experimental study on partial replacement of cement with coconut shell ash in concrete. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2014, 3, 651–661. [Google Scholar]

- Terungwa, K.; Emmanuel, M. Effect of coconut shell ash on the sulhate resisting capabilities of concrete. Int J Adv Eng Res Technol (IJAERT) 2018, 6, 393–399. [Google Scholar]

- Jerlin Regin, J.; Vincent, P.; Ganapathy, C. Effect of mineral admixtures on mechanical properties and chemical resistance of lightweight coconut shell concrete. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2017, 42, 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, K.; Annadurai, R.; Kumar, P. A study on some durability properties of coconut shell aggregate concrete. Mater. Struct. 2015, 48, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, W.; Aslam, M.; Ejaz, M.F.; Ali, M.J.; Ahmad, R.; Raza, M.W.-u.-H.; Khan, A. Mechanical properties, drying shrinkage and structural performance of coconut shell lightweight concrete. Structures 2022, 35, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.S.; Yang, J.; Bahurudeen, A.; Abdalla, J.; Hawileh, R.A.; Hamada, H.M.; Nazar, S.; Jittin, V.; Ashish, D.K. Sugarcane bagasse ash as supplementary cementitious material in concrete–a review. Mater. Today Sustain. 2021, 15, 100086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambabu, P.; Gupta, K.D.; Ramarao, G. Effect of sulphates (Na2So4) on concrete with sugarcane bagasse ash as a pozzolana. Int. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2016, 3, 257749. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chai, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, X.; Si, Z. Utilization of sugarcane bagasse ash (SCBA) in construction technology: A state-of-the-art review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 56, 104774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Siqueira, A.A.; Cordeiro, G.C. Sustainable cements containing sugarcane bagasse ash and limestone: Effects on compressive strength and acid attack of mortar. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmi, S.M.S.; Munir, M.J.; Patnaikuni, I.; Wu, Y.-F. Pozzolanic reaction of sugarcane bagasse ash and its role in controlling alkali silica reaction. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 148, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F.L.; Cordeiro, G.C. Partial cement replacement by different sugar cane bagasse ashes: Hydration-related properties, compressive strength and autogenous shrinkage. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 272, 121625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya, K.L.; Ragupathy, R. Effect of sugarcane bagasse ash on strength properties of concrete. Int. J. Res. Eng. Technol 2016, 5, 159–164. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, F.; Qiao, H.; Shu, X.; Cui, L.; Li, S.; Zhang, T. Potential application of highland barley straw ash as a new active admixture in magnesium oxychloride cement. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 59, 105108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Qiao, H.; Wang, P.; Li, W.; Li, Y. Frost resistance of magnesium oxychloride cement mortar added with highland barley straw ash. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mater. Sci. Ed. 2022, 37, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, M.; Abdullah, T.; Fenniche, F.; Kouider, H.H. The Effect of Adding Barley and Oats Husks Ashes on the Properties of Ordinary Portland cement. Bani Walid Univ. J. Humanit. Appl. Sci. 2023, 8, 271–282. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, V.; Singh, N.; Das, S.; Singh, N. A new pozzolanic material for cement industry: Bamboo leaf ash. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2006, 1, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Nduka, D.O.; Olawuyi, B.J.; Ajao, A.M.; Okoye, V.C.; Okigbo, O.M. Mechanical and durability property dimensions of sustainable bamboo leaf ash in high-performance concrete. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2022, 11, 100583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujedu, K.; Lamidi, I.; Olomo, R.; Alao, M. Evaluation of physical and mechanical properties of partially replaced bamboo ash cement mortar. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2018, 7, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ikumapayı, C.M.; Jegede, O. Effects of bamboo leaf ash on alkali-silica reaction in concrete. J. Sustain. Constr. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikumapayi, C.; Akingbonmire, S.; Oni, O. The Influence of Partial Replacement of Some Selected Pozzolans on the Drying Shrinkage of Concrete. Sci. Rev. 2019, 5, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darweesh, H. Effect of banana leaf ash as a sustainable material on the hydration of Portland cement pastes. Int. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulwahab, M.; Uche, O. Durability properties of self-compacting concrete (SCC) incorporating cassava peel ash (CPA). Niger. J. Technol. 2021, 40, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, J.A.; Gana, A.J.; Ayinnuola, G.; Adanikin, A.; Faleye, E.; Popoola, O. Suppression of Alkali-Silica Reactions in Concrete by Partially Replacing Cement with Cassava Peel Ash. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Science, Engineering and Business for Sustainable Development Goals (SEB-SDG), Omu-Aran, Nigeria, 5–7 April 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Mildawati, R.; Puri, A.; Handayani, M.Z. Effects of Corn Stalks Ash as A Substitution Material of Cement Due to the Concrete Strength of Rigid Pavement. J. Geosci. Eng. Environ. Technol. 2022, 7, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, H.; Hou, P.; Cheng, X. Effect of cornstalk ash on the microstructure of cement-based material under sulfate attack. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 358, 052010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakouri, M.; Exstrom, C.L.; Piccini, G.D. Chloride binding and desorption properties of the concrete containing corn stover ash. J. Sustain. Cem. Based Mater. 2022, 11, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Mishra, M.; Suganya, O. The incorporation of wood waste ash as a partial cement replacement material for making structural grade concrete: An overview. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2015, 6, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Production—Rice. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/production/commodity/0422110 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Production—Wheat. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/production/commodity/0410000 (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- World Sugarcane Production by Country. Available online: https://www.atlasbig.com/countries-sugarcane-production (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Tural, H.; Ozarisoy, B.; Derogar, S.; Ince, C. Investigating the governing factors influencing the pozzolanic activity through a database approach for the development of sustainable cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekar, A.; Arunachalam, K.; Kottaisamy, M.; Saraswathy, V. Durability characteristics of Ultra High Strength Concrete with treated sugarcane bagasse ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 171, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.S.A.; de França, M.J.S.; de Amorim Júnior, N.S.; Ribeiro, D.V. Effects of adding sugarcane bagasse ash on the properties and durability of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 266, 120959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Ishfaq, M.; Amin, M.N.; Shahzada, K.; Wahab, N.; Faraz, M.I. Evaluation of mechanical and microstructural properties and global warming potential of green concrete with wheat straw ash and silica fume. Materials 2022, 15, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qudoos, A.; Kakar, E.; Rehman, A.U.; Jeon, I.K.; Kim, H.G. Influence of milling techniques on the performance of wheat straw ash in cement composites. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.C.; Toledo Filho, R.D.; Tavares, L.M.; Fairbairn, E.d.M.R.; Hempel, S. Influence of particle size and specific surface area on the pozzolanic activity of residual rice husk ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2011, 33, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Quero, V.; León-Martínez, F.; Montes-García, P.; Gaona-Tiburcio, C.; Chacón-Nava, J. Influence of sugar-cane bagasse ash and fly ash on the rheological behavior of cement pastes and mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 40, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C150/C150M-22; Standard Specification for Portland Cement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Givi, A.N.; Rashid, S.A.; Aziz, F.N.A.; Salleh, M.A.M. Assessment of the effects of rice husk ash particle size on strength, water permeability and workability of binary blended concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 2145–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.C.; Toledo Filho, R.D.; de Moraes Rego Fairbairn, E. Use of ultrafine rice husk ash with high-carbon content as pozzolan in high performance concrete. Mater. Struct. 2009, 42, 983–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.; Toledo Filho, R.; Tavares, L.; Fairbairn, E. Pozzolanic activity and filler effect of sugar cane bagasse ash in Portland cement and lime mortars. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2008, 30, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Huang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, M. Modelling of irregular-shaped cement particles and microstructural development of Portland cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 168, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Das, B.B.; Adak, D. Insights into cementitious materials: Exploring atomic structures and interactions. Discov. Concr. Cem. 2025, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpan, S.; Ziga-Carbarín, J.; Rodríguez-Barboza, L.I.; Sanal, K.; Acevedo-Dávila, J.L.; Balonis, M.; Gómez-Zamorano, L.Y. Strength and microstructure assessment of partially replaced ordinary portland cement and calcium sulfoaluminate cement with Pozzolans and spent coffee grounds. Materials 2023, 16, 5006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudeep, Y.; Ujwal, M.; Mahesh, R.; Shiva Kumar, G.; Vinay, A.; Ramaraju, H. Optimization of wheat straw ash for cement replacement in concrete using response surface methodology for enhanced sustainability. Low-Carbon Mater. Green Constr. 2024, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojedokun, O.; Mangat, P. Characterization and pore structure of rice husk ash cementitious material. In ACI SP-326: Durability and Sustainability of Concrete Structures (DSCS-2018); Sheffield Hallam University: Sheffield, UK, 2018; Volume 326, pp. 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bülbül, F.; Courard, L. Turning Waste into Greener Cementitious Building Material: Treatment Methods for Biomass Ashes—A Review. Materials 2025, 18, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, M.; Senthil, K. Approach towards net-zero carbon emission: Rice husk ash cementitious material on the fibrous reinforced concrete beams under mechanical loading through the experiment and simulations. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).