Abstract

This study investigates the torrefaction of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and cellulose, two major constituents of agricultural waste, with the aim of improving chlorine removal and enhancing the energy quality of the resulting solid products. Thermodynamic simulations using HSC Chemistry 9.0 were first conducted to predict equilibrium compositions, particularly chlorine-containing species. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and coupled TGA-FTIR were employed to monitor mass loss and identify gaseous chlorine compounds. Based on these preliminary results, torrefaction experiments were carried out at temperatures of 250–300 °C and durations of 30–90 min. The results demonstrate a significant synergistic effect between cellulose and PVC during co-torrefaction, achieving 97% chlorine removal under optimal conditions (9:1 cellulose-to-PVC ratio, 250 °C, 30 min). This effective dechlorination helps mitigate Cl-induced corrosion and reduces the risk of dioxin formation in industrial applications, enabling the sustainable upcycling of PVC-contaminated biomass into clean solid fuels. Torrefaction temperature exerted a stronger influence than time on mass loss, yielding approximately 40% solid residue at 300 °C. While both solid and energy yields decreased with increasing temperature and time, the O/C and H/C atomic ratios decreased by 56% and 48%, respectively, indicating a substantial improvement in fuel properties. The observed synergy is attributed to cellulose-derived hydroxyl radicals promoting PVC dehydrochlorination. This process offers a scalable and economically viable pretreatment route for PVC-containing biomass, potentially reducing boiler corrosion and hazardous emissions.

1. Introduction

Fossil fuels, which still account for over 80% of the global primary energy mix, face mounting depletion concerns while simultaneously driving energy-related CO2 emissions to a record high of approximately 40.8 Gt CO2 equivalent in 2024 [1]. In response, China is implementing the world’s most extensive decarbonization agenda, targeting a carbon intensity reduction of 18% per GDP unit during the 15th Five-Year Plan period (2026–2030) [2]. Biomass is widely considered a promising alternative to traditional energy sources owing to its renewable nature and potential for carbon neutrality, which can help alleviate the energy crisis and reduce reliance on fossil fuels [3]. Annually, China generates approximately 100 million tons of crop straw, and the push towards dual-carbon goals has positioned agricultural biomass power generation as a key strategy for waste management and rural revitalization, with installed capacity reaching about 17.09 GW by the end of 2024 [4].

However, the standalone development of biomass power generation faces multiple challenges, including the low energy density and calorific value of biomass, high costs associated with collection and transportation, and the need for complex flue gas purification systems. These hurdles underscore the necessity for more efficient conversion technologies and scalable applications.

In parallel, hydrogen has emerged as a pivotal carbon-free energy carrier for the future, prized for its high energy density and zero pollutant emissions at the point of use [5]. Syngas production from biomass via thermochemical processes like pyrolysis and gasification is a major research focus for hydrogen production [6]. A significant technological advancement involves the co-pyrolysis of biomass with hydrogen-rich materials to improve syngas quality. Biomass is inherently hydrogen-deficient (H/Ceff ratio: 0–0.3), resulting in low theoretical hydrocarbon yields [7]. Plastics, primarily composed of polyolefins with a high H/Ceff of ~2, serve as an ideal co-feedstock. The catalytic co-pyrolysis of biomass and plastics has been shown to produce a positive synergistic effect, enhancing hydrocarbon content and reducing oxygenated compounds in the syngas.

This approach is particularly relevant in China, the world’s largest producer and consumer of agricultural films, with an output exceeding 2.4 million t in 2022 [8]. In practice, plastic agricultural film and straw are often mixed together in agricultural waste streams, making their co-processing a logical and necessary waste management strategy. While the co-pyrolysis or gasification of biomass and plastics for H2 and syngas production has been widely studied [9,10], a critical issue that has received inadequate attention is the role of chlorine. The presence of chlorine in plastic waste, particularly from PVC components in agricultural films, introduces severe technical and environmental challenges.

Chlorine is a pivotal element in the formation of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) during thermal treatment, most notably polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans (PCDDs/PCDFs) [11]. These compounds form mainly through chlorine-dependent routes, such as the recombination of chlorinated precursors and de novo synthesis on fly ash. Furthermore, most chlorine converts to hydrogen chloride (HCl), which corrodes equipment [12], necessitates costly flue gas cleaning systems, and promotes the volatilization of toxic heavy metals [13]. Therefore, addressing the chlorine issue is paramount for the safe, efficient, and economically viable application of biomass-plastic co-pyrolysis.

To mitigate these challenges and improve the feedstock quality for thermochemical conversion, pretreatment techniques are essential. Torrefaction, a mild pyrolysis process conducted at 200–300 °C in an inert atmosphere, has gained attention as an effective pretreatment method. The link between hydrogen energy systems and torrefaction lies in the latter’s ability to upgrade raw biomass and potentially mixed wastes. Torrefaction improves grindability, increases energy density, and reduces the oxygen and moisture content of the feedstock. More importantly for the chlorine issue, some studies suggest that torrefaction can partially remove chlorine and other undesirable elements from biomass. By applying torrefaction as a pretreatment step before co-pyrolysis/gasification, the resulting feedstock is not only more favorable for high-quality syngas and hydrogen production but may also lead to a reduction in chlorine-related pollutants and operational problems downstream. This positions torrefaction as a critical preparatory step in the value chain linking mixed agricultural waste to clean hydrogen production.

Dechlorination technologies are primarily categorized into mechanical [14], hydrothermal [15,16], thermal decomposition, and several emerging methods. Mechanical dechlorination liberates chlorine via milling and washing, effectively removing water-soluble chlorides from biomass. However, its efficacy is limited for organochlorine compounds (e.g., in PVC), and it generates wastewater requiring further treatment. While co-hydrothermal carbonization (Co-HTC) is considered an excellent resource recovery strategy for converting PVC waste into low-chlorine solid fuel—thanks to its superior dechlorination capability—it suffers from a practical drawback. Although the subcritical water medium (200–300 °C, saturated pressure) efficiently removes chlorine from the PVC matrix and converts it into aqueous inorganic chloride, the process typically necessitates a high liquid-to-solid ratio. This requirement creates a substantial burden for post-processing wastewater treatment. Previous studies on chlorine migration in the thermal decomposition process of biomass or their mixture with plastics have primarily focused on pyrolysis, combustion, and gasification processes at reaction temperatures of 300–1000 °C, while its behavior during torrefaction has received considerably less attention.

Torrefaction as a pretreatment technology of biomass in a low-temperature, inert atmosphere has been widely studied; most studies focus on improving the properties of biomass fuels, such as energy density, calorific value, hydrophobicity, and homogeneity [17]. More importantly, torrefaction can significantly reduce the Cl content in baked biomass; thus, baked biomass as a fuel or raw material for gasification/pyrolysis requires much less corrosion-resistant processing equipment and reduces the corrosion of boilers. It is more technically practical and economically efficient to remove Cl during the torrefaction pretreatment process than to treat chlorine-containing gas afterwards.

The combination of biomass and PVC has been shown to be synergistic in terms of dechlorination efficiency [15]. In addition, torrefaction pretreatment for PVC releases most of the Cl contained in the materials as HCl or CH3Cl during the low-temperature stage of pyrolysis. Another study first reveals that hemicellulose significantly reduced HCl emissions by immobilizing most of the Cl molecules in the sample into a pyrolysis residue [18].

However, a systematic analysis of torrefaction parameters (temperature, time, blend ratios) on dechlorination efficiency remains limited. The diverse nature of biomass and the complex composition of waste plastics make it essential to investigate the dechlorination characteristics during their co-thermal treatment.

In this study, torrefaction technology is introduced for the dechlorination of biomass and plastics. Typical biomass, cellulose, and PVC plastics are selected for torrefaction experiments. Thermodynamic equilibrium simulations were employed to analyze chlorine release behavior. Guided by these simulation results, the effects of torrefaction temperature and time on baked products are investigated, elemental measurements are conducted on original and baked coke samples, mass loss and solid and energy yields are calculated, and finally, Cl removal rate is explored.

The primary objectives of the study are as follows: (1) to examine the kinetics of Cl removal, (2) to gain mechanistic insights into synergistic dechlorination, and (3) to optimize energy yield. The study aims to provide data support for the low-temperature co-pyrolysis technology of biomass and plastics, as well as for its industrial application.

This study systematically investigated the co-torrefaction of cellulose and PVC for dechlorination. Its core innovation lies in elucidating a synergistic mechanism that enables highly efficient dechlorination (>97%) and concurrent fuel quality enhancement under significantly milder conditions (e.g., 250 °C and a 30 min residence time), thereby overcoming the reliance on harsh conditions in conventional processes and providing a novel strategy for the synergistic resource utilization of biomass and chlorinated plastics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The type of biomass used can vary widely. Straw, a predominant and widely available biomass, chiefly comprises cellulose (35–50%), hemicellulose (20–35%), and lignin (10–25%). Given its predominance, cellulose was chosen as the sample material in this work to minimize potential interference.

The major constituents of plastics in wastes include polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polyethylene (HDPE and LDPE), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) [19]. To preserve the characteristic properties of plastics while avoiding complications from additives, PVC was employed as the material in this investigation. This approach ensures that the core material behavior is examined without significant confounding factors.

Cellulose and PVC were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The ultimate analysis (elemental analyzer, vario EL cube, Elementar, Germany) is summarized in Table 1. The sample is analyzed in duplicate, and the results are reported as the mean. The analysis errors are in the range of ±0.3 mass%.

Table 1.

Industrial and elemental analyses of cellulose and PVC.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Thermodynamic Calculations

The thermodynamic calculations were performed using HSC Chemistry 9.0, which is a thermochemical software designed for various kinds of chemical reactions and equilibrium calculations. The properties of the effluent products, especially chlorine-related compounds from pyrolysis, are obtained. The calculation uses an equilibrium model based on the Gibbs energy minimization method. The thermodynamic equilibrium analysis is based on a computational model with the following assumptions:

- (1)

- The co-pyrolysis process of cellulose and PVC is simplified as a thermodynamic equilibrium problem of chemical reactions in an isothermal, isobaric closed system at a pressure of 1 atm. The system is assumed to reach a state of equilibrium.

- (2)

- The initial inputs for the co-pyrolysis process include the elemental composition of cellulose and PVC, nitrogen, sulfur, chlorine, fixed carbon, and H2O (detailed data provided in Table 1).

- (3)

- The co-pyrolysis process was conducted in an inert atmosphere with nitrogen as the carrier gas.

- (4)

- The calculation considers gaseous and condensed species formed by the elements C, H, O, N, Cl, and S, sourced from the HSC Chemistry 9.0 database. Detailed species are listed in Tables S1 and S2.

2.2.2. TG-FTIR Analysis

Thermogravimetric analysis was performed using a Simultaneous Thermal Analyzer (STA 449 F3 Jupiter, NETZSCH, Selb, Germany). The measurement was conducted by heating 8–10 mg of the powdered sample from room temperature to 800 °C at a constant heating rate of 10 °C/min under a high-purity nitrogen atmosphere (99.999%).

The pyrolysis products of the simulated cellulose/PVC mixture were analyzed using a coupled simultaneous thermal analyzer-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (TGA-FTIR) system (Thermo Scientific IS30, Waltham, MA, USA). For the TGA-FTIR analysis, approximately 8–10 mg of the powdered cellulose/PVC sample was heated from 30 to 700 °C under an argon atmosphere at a constant heating rate of 10 °C/min. The evolved gases were directly transferred to the FTIR spectrometer via a heated transfer line. The infrared spectra were acquired in transmission mode over the range of 500–4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and a scanning frequency of 5.48 s per spectrum.

2.2.3. Torrefaction Treatment

To enhance the practical relevance of the torrefaction treatment, the cellulose and plastic blends were formulated based on three key considerations: (1) the typical composition of agricultural waste [20]; (2) thermodynamic calculations of cellulose-PVC co-pyrolysis; and (3) the need to limit the total chlorine content in the samples. As previously noted, chlorine is a key determinant of multiple challenges in waste incineration, primarily through its central role in the formation of PCDD/Fs, the volatilization of toxic heavy metals, and the induction of high-temperature corrosion, all of which complicate pollution control and increase operational costs.

Prior to pyrolysis, all cellulose/PVC blends (compositions given in Table 2) were dried, ground, and passed through a 200-mesh sieve, ensuring consistent particle size and minimizing their hindrance to heat transfer.

Table 2.

Sample number, composition, and ratio.

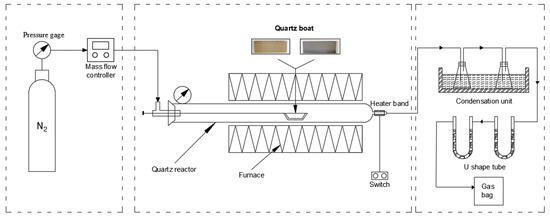

The torrefaction of cellulose-PVC was carried out at atmospheric pressure in a dual-zone tube furnace (TL1200-1200, Nanjing Boynton Instruments, Nanjing, China), schematically shown in Figure 1. The setup included a gas supply system (gas cylinder and mass flow controller) to maintain an inert atmosphere and a torrefaction reactor built around a quartz tube (50 mm i.d., 60 mm o.d.) sealed with 316 L flanges. The reactor, heated by a high-resistance alloy wire (max. 1200 °C) and controlled via an N-type thermocouple, featured a double-shell design with cooling to keep the exterior below 40 °C.

Figure 1.

Schematic of pyrolysis system.

The dried sample (2.0 g) was placed in a pre-weighed crucible and evenly distributed by gentle shaking. The crucible was then positioned within the reactor, which was subsequently sealed and purged with nitrogen. The system pressure was maintained at 0.1 MPa with a gas flow of 50 mL/min for 30 min. The reaction was conducted at prescribed temperatures (250 °C, 275 °C, 300 °C) and times (30 min, 60 min, 90 min). Upon completion and cooling, the solid residue was collected, weighed, and packaged for elemental analysis.

Chlorine was determined by the Eschka mixture fusion and potassium thiocyanate titration method, as stipulated in Standard GB/T 3558-2014 [21].

3. Discussion and Results

3.1. Thermodynamic Calculations

Thermodynamic modeling serves as an indispensable tool in the research and development of thermochemical conversion processes, providing critical insights into equilibrium compositions, product yields, and system energy requirements under specified conditions. For biomass pyrolysis or gasification, these simulations are particularly vital. They enable the prediction of key outputs, such as syngas quality (e.g., H2/CO ratio) and HCl formation tendencies by solving for chemical equilibrium at various temperatures and feedstock compositions. This predictive capability is crucial for optimizing operating parameters and for assessing the feasibility and environmental impact of different process pathways. Furthermore, thermodynamic models act as a foundational framework for scaling up laboratory findings to industrial applications, thereby significantly reducing the time and cost associated with experimental trial-and-error.

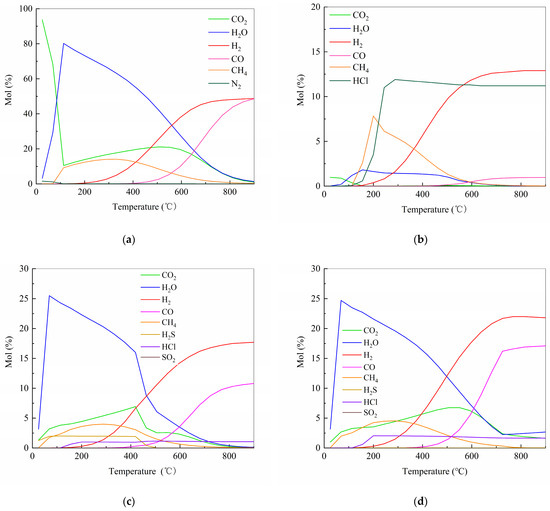

The thermodynamic simulation results are presented in Figure 2. As depicted in Figure 2a, the pyrolysis of pure cellulose primarily yields H2 and CO, with negligible HCl generation due to the absence of chlorine in the feedstock. In contrast, the pyrolysis of pure PVC (Figure 2b) exhibits substantial HCl release, commencing at approximately 115 °C. The evolution rate increases sharply, maintaining a rapid pace until 245 °C, before decelerating and reaching completion around 288 °C. Figure 2c and Figure 2d illustrate the co-pyrolysis behavior of cellulose and PVC at mass ratios of 9:1 and 8:2, respectively. For both mixtures, the majority of HCl is released rapidly within the 115–200 °C range. In the 9:1 mixture (Figure 2c), the evolution rate decreases significantly after 200 °C, followed by a minor secondary release peak between 420 and 465 °C. A higher PVC content (8:2 ratio, Figure 2d) results in a more complete HCl release within the initial low-temperature stage (115–200 °C).

Figure 2.

Thermodynamic calculations result. (a) cellulose; (b) PVC; (c) mass ratio of cellulose to PVC = 9:1; (d) mass ratio of cellulose to PVC = 8:2.

Despite its utility, thermodynamic modeling is inherently limited by its equilibrium assumption, which often neglects the critical roles of reaction kinetics, heating rates, and transport phenomena, leading to potential deviations from experimentally observed product distributions, especially in complex processes like biomass conversion.

3.2. TG-FTIR Analysis

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) provides critical experimental validation of decomposition stages and kinetics but is inherently limited to mass loss profiles without elucidating specific gas-phase compositions. The coupling of Thermogravimetric Analysis with Fourier-Transform Infrared spectroscopy (TGA-FTIR) correlates mass loss events observed in TGA with the real-time chemical identification of evolving gaseous species by FTIR. By doing so, it directly bridges the quantitative thermal decomposition profile with qualitative molecular information, enabling definitive determination of reaction mechanisms, such as identifying the specific composition of volatile products during pyrolysis.

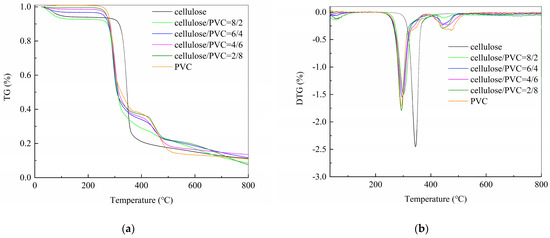

Figure 3 presents the thermogravimetric analysis results of cellulose and PVC mixed at different ratios. It is clearly observed that the main weight loss interval begins at approximately 250 °C, which is notably later than the theoretical prediction by HSC.

Figure 3.

TG-DTG analysis of cellulose-PVC in inert atmosphere; (a)TG; (b) DTG.

Cellulose primarily undergoes one rapid decomposition stage within the temperature range of 286.81–405.52 °C, with a mass loss of 74.33%. This stage is mainly attributed to the cleavage of cellulose, releasing volatile compounds including dehydrated sugars, C1-C3 fragments, and furans, formed through pyrolysis reactions such as depolymerization, dehydration, and fragmentation [22].

The pyrolysis of PVC occurs in two distinct rapid stages. The first stage, ranging from 231.76 to 371.66 °C, results in a mass loss of 60.51%, primarily due to the formation of volatiles and the development of conjugated double bonds in the polyene chain. Within this stage, two overlapping peaks are observed in the DTG curve, with a minor shoulder peak appearing between 310 and 349 °C—a phenomenon also reported in other studies [23]. This results from the release of two types of volatiles in this temperature range, indicating two concurrent reactions [24]. It has been confirmed that the weight loss in this stage is partly due to the release of HCl and partly due to the decomposition of other volatile components.

The TG-DTG curves of cellulose and PVC co-pyrolysis indicate that mixtures with ratios of 8:2, 6:4, 4:6, and 2:8 exhibit pyrolysis behavior more closely resembling that of PVC. The addition of PVC shifts the decomposition of cellulose to a lower temperature range, a finding consistent with reports by other researchers [25]. This may be attributed to the catalytic effect of HCl released from PVC dechlorination on cellulose pyrolysis [26]. The overlapping temperature regimes of PVC dechlorination and cellulose decomposition (250–370 °C) facilitate this synergistic interaction. Furthermore, biomass/biochar can sequester the released Cl, which subsequently influences the further decomposition of the material [27].

Compared with individual pyrolysis, the co-pyrolysis of cellulose and PVC shows a noticeably earlier onset and termination temperature. This may be due to the overlapping pyrolysis temperature ranges of cellulose and PVC, increasing the likelihood of synergistic interactions [25,28]. Inorganic elements in biochar may also promote the decomposition of waste plastics. Additionally, HCl released from PVC may act as an acid catalyst, facilitating the dehydration and decomposition of glucose monomers in cellulose [29].

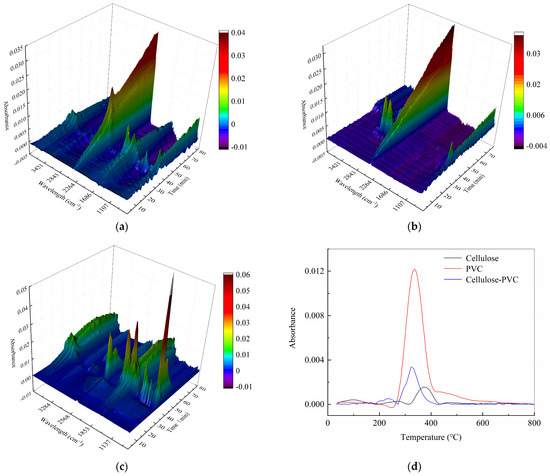

The thermal decomposition processes of cellulose, PVC, and a cellulose/PVC mixture were investigated using TG-FTIR, allowing for clearer identification of the chemical reactions occurring during mass loss and the characteristics of chlorine release [30]. Figure 4 presents a three-dimensional infrared spectroscopic overview of the cellulose/PVC pyrolysis process.

Figure 4.

TG-FTIR absorbance spectrum of (a) cellulose; (b) PVC; (c) mixture of cellulose and PVC pyrolyzed at 10 °C/min. (d) HCl infrared waveband vs. temperature curve at 10 °C/min.

To identify chlorine-containing species in the pyrolysis products of cellulose and PVC, FTIR analysis was performed on their mixtures. Figure 4 displays the infrared spectra of cellulose, PVC, and their mixture. The absorption peak observed between 3100 and 2600 cm−1 is attributed to the asymmetric stretching vibration of HCl, indicating its formation [31]. Additionally, the C–Cl stretching vibration is detected within the 800–600 cm−1 range [31,32].

As shown in Figure 4b, HCl—the primary gaseous product of PVC pyrolysis—is predominantly released between 250 and 400 °C, with its intensity diminishing as temperature increases. Only trace amounts of HCl remain detectable by 440 °C, marking the practical conclusion of the first decomposition stage. Notably, HCl evolution is also observed during cellulose pyrolysis between 350 and 450 °C. The absorption spectrum of the cellulose/PVC mixture (Figure 4c) reveals that co-pyrolysis not only advances the release of HCl to lower temperatures but also reduces its total evolved amount.

Figure 4d illustrates the temperature-dependent intensity variation in HCl in the infrared region during the pyrolysis of the cellulose/PVC mixture at 10 °C/min. It is evident that HCl, as the main pyrolysis product of PVC, is primarily released between 250 and 400 °C, with its signal declining as temperature rises. Only minimal HCl is detectable by 440 °C, indicating the end of the primary decomposition stage. The release of HCl is also observed during cellulose pyrolysis in the 350–450 °C range. The absorption spectrum of the cellulose/PVC blend demonstrates that co-pyrolysis shifts HCl release to earlier temperatures while also reducing the total amount of HCl evolved.

3.3. Low Temperature Dechlorination Experiment

Based on the results of thermodynamic calculations, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and TG-FTIR analysis, low-temperature dechlorination experiments were conducted at prescribed temperatures (250 °C, 275 °C, 300 °C) and durations (30 min, 60 min, 90 min). After completion and cooling, the solid residues were collected, weighed, and packaged for chlorine content analysis.

To evaluate the extent of dechlorination under torrefaction, the dechlorination rate was defined as

where m0 is the mass of the original sample (g), mr is the mass of the sample after torrefaction (g), c0 is the mass fraction of elemental chlorine in the original sample (%), and cr is the mass fraction of elemental chlorine in the original sample after torrefaction (%).

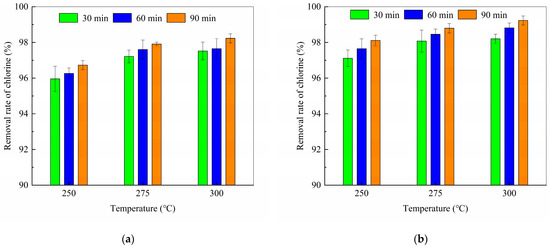

Figure 5 illustrates the influence of torrefaction temperature and time on chlorine removal from cellulose and PVC blends. As both temperature and duration increased, chlorine removal efficiency improved, and the chlorine content in the torrefied products decreased. The highest dechlorination efficiency of 99.18% was achieved with a cellulose-to-PVC ratio of 9:1, a torrefaction temperature of 300 °C, and a duration of 90 min, resulting in a residual chlorine content of 0.04% in the solid product. This performance surpassed that of single-component PVC torrefaction (82.51%) [33], indicating a pronounced synergistic effect during co-pyrolysis. The presence of hydroxyl radicals derived from cellulose was found to accelerate PVC dehydrochlorination (Figure 5a), identifying this synergy as a key mechanistic factor.

Figure 5.

Dechlorination rates of a mixture of cellulose and PVC at different temperatures and duration time (a) at a mass ratio of 8:2; (b) at a mass ratio of 9:1.

The interaction between cellulose and PVC lowered the onset temperature of dechlorination. Cellulose-derived radicals abstract hydrogen from PVC, facilitating HCl release [34]. For instance, the 9:1 blend achieved 99.18% chlorine removal at 300 °C (Figure 5b), whereas pure PVC required temperatures above 350 °C for comparable efficiency [35]. This synergy is consistent with the findings of Zhou et al. [36], who reported that HCl released from PVC catalyzes the acid-induced dehydration of cellulose, further promoting dechlorination.

HCl is the primary volatile product of PVC pyrolysis. Zhou et al. [36] analyzed chlorine retention in char to understand the temperature-dependent initiation and completion of dechlorination. By normalizing the chlorine content in pyrolysis char to the total chlorine in the original PVC, they determined that dechlorination starts at 300 °C in pure PVC. However, in cellulose–PVC blends, the synergistic interaction reduces the activation energy of cellulose pyrolysis. The HCl released from PVC acts as an acid catalyst, promoting dehydration and decomposition of cellulose glucose units [36], thereby lowering the overall energy barrier for co-pyrolysis and initiating dechlorination below 300 °C.

Notably, higher PVC content (e.g., 8:2 blend) enhanced HCl release but also increased residual chlorine in the char (0.2% vs. 0.1% for the 9:1 blend at 300 °C). This suggests the presence of competing pathways: (i) PVC-derived HCl promotes cellulose decomposition, and (ii) excess chlorine-containing intermediates may recombine with the char matrix.

To facilitate a comparative assessment of dechlorination efficiency, the results from other relevant studies are summarized in Table 3. Dechlorination efficiency can reach a high of about 98–99% for PVC by low-temperature pyrolysis [37,38,39], yet the temperature used is within the range of 340–360 °C, which is higher than that used in this study (250 °C, 275 °C, 300 °C). For pure biomass torrefaction, the dechlorination efficiency is relatively low [40,41]. Dechlorination efficiency can be as high about 90–92% for biomass under the hydrothermal process [15].

Table 3.

Product distribution and dechlorination effect of different waste materials.

The energy content of the resulting solid is a critical parameter for assessing torrefaction process performance. The energy of the product was calculated based on the change in cellulose and PVC elemental content after torrefaction, using high calorific value as a parameter.

The development of empirical equations to estimate the heating value of fuels from their elemental composition has a long history, with numerous models established for various fuel types. While early and extensive efforts have focused primarily on coal, and more recent ones on municipal solid waste, dedicated models for biomass remain relatively scarce. Friedl et al. [42] predicted the heating values of biomass fuel from elemental composition. They chose a diverse set of 122 biomass samples, including wood, grass, rye, and poultry litter, from the BIOBIB database. A regression model for predicting the higher heating value (HHV) was developed using partial least squares (PLS) regression, with C, H, N, C2, and C × H as predictors. The model achieved a high performance (R2 = 0.943) and a low standard error of calibration (337 kJ/kg) across the HHV range of 15,000–25,000 kJ/kg. Notably, the prediction errors of their new models were substantially lower than those of existing models in the literature.

The PLS regression equation was applied to calculate the higher heating value (HHV) of the cellulose-PVC mixture and its pyrolysis products from their elemental composition [42].

where the higher heating value, HHV, is in kJ/kg; C, H, and N are the masses of carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen in the dry biomass, respectively. The standard uncertainties (σ) for the elemental composition data were estimated as ±0.5% for both carbon and hydrogen, and ±0.1% for nitrogen. These values were assigned based on the manufacturer’s specifications for the elemental analyzer and common practice, with the lower uncertainty for nitrogen accounting for its trace-level concentration.

Solid yield and energy yield are calculated according to Equations (3) and (4) below.

where Ymass and Yenergy represent the solid and energy yields, respectively; M and HHV represent the mass and high calorific value, respectively; and the subscripts product and feed represent the baked solid products and original samples, respectively.

Table 4 shows the elemental content parameters and HHV of the solid products after torrefaction.

Table 4.

Elemental content parameters and HHV of cellulose and PVC after torrefaction.

As shown in Table 4, increasing torrefaction temperature promoted carbon enrichment in the samples, evidenced by the rising fixed carbon content and carbon weight percentage, due to the release of volatiles and decomposition of oxygenated structures. Consequently, the oxygen content decreased while the higher heating value (HHV) increased. The HHV of raw cellulose and PVC before torrefaction is (16.45 ± 0.18) MJ/kg and (15.75 ± 0.16) MJ/kg, respectively. Relative to the raw cellulose, torrefaction at 250 °C for 30 min raised the HHV of the 9:1 and 8:2 blends by 2.57 and 2.11 MJ/kg, respectively. Although HHV generally increased with more severe torrefaction, the effect diminished at higher temperatures. For the 8:2 blend at 300 °C, extending time from 30 to 90 min only increased HHV from (27.09 ± 0.53) MJ/kg to (28.01 ± 0.57) MJ/kg, suggesting limited benefit from prolonged treatment at high temperature.

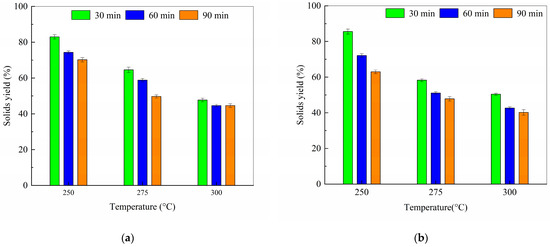

The influence of torrefaction temperature and residence time on solid yield was investigated for cellulose-PVC blends at mass ratios of 8:2 and 9:1 (Figure 6). For the 8:2 blend, a temperature increase from 250 °C to 300 °C at a fixed 30 min residence time caused a pronounced decrease in solid yield from 85.56% to 50.44%. Similarly, extending the residence time from 30 to 90 min at 250 °C reduced the solid yield from 85.56% to 63.02%. However, at 300 °C, the same time extension led to a smaller decrease, from 50.44% to 40.18%.

Figure 6.

Effect of temperature on solids yields of torrefaction sample with cellulose to PVC ratio of (a) 9:1; (b) 8:2.

In contrast, the 9:1 blend exhibited different behavior. While temperature remained a significant factor, the effect of residence time was markedly attenuated. At 250 °C, extending the time from 30 to 90 min reduced the solid yield by 12.82 percentage points (from 83.04% to 70.22%), compared to a 22.54-point drop for the 8:2 blend. Conversely, at 300 °C, the time extension resulted in a mere 3.15-point decrease (from 47.74% to 44.59%), substantially less than the 10.26-point decrease observed for the 8:2 blend.

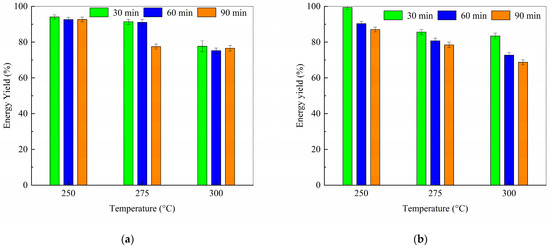

Figure 7 shows the influence of torrefaction temperature and residence time on energy yield. The decline in energy yield with rising temperature reflects greater energy loss under more severe torrefaction. Nevertheless, the energy yields of the torrefied solids remain higher than their corresponding mass yields, indicating that the solid products became energetically enriched compared to the original samples.

Figure 7.

Effect of temperature on energy yields of torrefaction sample with cellulose to PVC ratio of (a) 9:1; (b) 8:2.

Figure 6 and Figure 7 suggest that minimizing both temperature and time is crucial for maximizing product yield from the 8:2 blend.

Notably, higher HHV was accompanied by substantial mass loss. Analysis of solid and energy yields revealed a trade-off: while the 8:2 blend achieved the same high HHV (28.01 ± 0.57 MJ/kg) as the 9:1 blend (28.14 ± 0.57 MJ/kg) at 300 °C/90 min, its greater mass loss (59.8% vs. 55.4%) reduced the energy yield advantage. Overall, the marginal HHV gains at high temperature failed to compensate for the cumulative mass loss, consistent with typical torrefaction trade-offs [43].

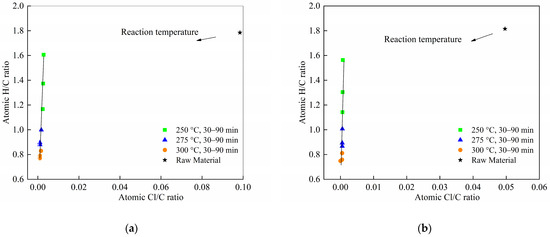

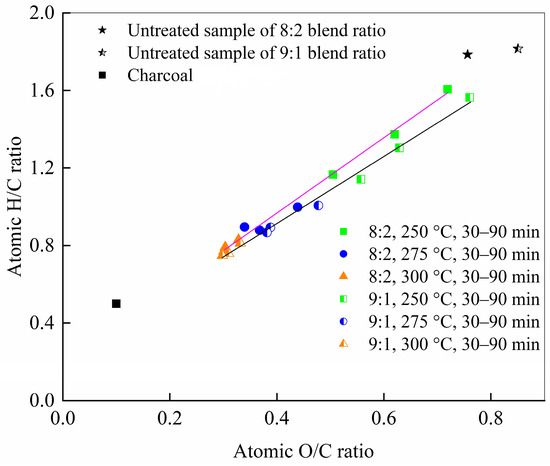

Figure 8 shows the Van Krevelen diagram for the original feedstock and the torrefied solids.

Figure 8.

Van Krevelen diagram for the original feedstock and the torrefied solids. (a) Cl/C and H/C ratios of sample 9:1 at different torrefaction temperatures and duration time; (b) Cl/C and H/C ratios of samples 8:2 at different torrefaction temperatures and duration time.

Comparing the biochars with the raw materials, it is possible to assess a more accentuated reduction in the Cl/C ratio and the H/C ratio with higher production temperatures. In general for PVC pyrolysis, a line with a slope of 1 can be regarded as a dechlorination line [44]. In this study, however, the slope substantially exceeded 1, suggesting that processes beyond mere dechlorination took place, likely due to synergistic interactions between cellulose and PVC. Furthermore, variations in torrefaction temperature exerted a more pronounced influence on both Cl/C and H/C ratios than changes in torrefaction time. Therefore, between these two parameters, torrefaction temperature is the more critical factor for controlling dechlorination in the samples.

To evaluate the influence of torrefaction on the fuel properties of the samples, the O/C and H/C atomic ratios of the torrefied products were analyzed under different temperature and time conditions. As shown in Figure 9, both the O/C and H/C ratios decreased with increasing temperature, a trend consistent with previous studies [45,46]. The reduction in hydrogen and oxygen content reflects the loss of hydroxyl (–OH) groups during torrefaction [47]. The 8:2 blend exhibited a more pronounced variation than the 9:1 blend, suggesting that temperature exerts a stronger influence than cellulose content in the 250–300 °C range.

Figure 9.

Van Krevelen diagram for the original feedstock and the torrefied solids. O/C and H/C ratios of samples at different torrefaction temperatures and duration times.

The slopes of the fitted lines for the atomic ratio changes were 1.73 and 1.94 for the 9:1 and 8:2 blends, respectively—both close to 2—indicating that dehydration is the dominant reaction pathway. After torrefaction at 300 °C, the fuel properties and chemical composition of the resulting chars resembled those of lignite or sub-bituminous coal [48]. Together with the notable increase in calorific value at higher temperatures [49], these results suggest that the torrefaction of cellulose and PVC blends mimics a coalification process. The observed improvements in fuel properties—marked decreases in H/C and O/C ratios and a rise in heating value—are attributed to the higher energy density of C–C bonds compared to C–O or C–H bonds, and the relative enrichment of carbon enhances the combustion characteristics of the torrefied solids.

The Van Krevelen diagram provides a clear visualization of the fuel characteristics of biomass and PVC mixture and torrefied products, enabling a direct comparison with other fuels. As shown in the diagram in Figure 9, the raw cellulose sample exhibits high O/C and H/C atomic ratios of 0.95 and 1.85, respectively, indicating poor fuel quality. When cellulose was blended with PVC at mass ratios of 9:1 and 8:2, the O/C ratios decreased to 0.85 and 0.75, and the H/C ratios to 1.81 and 1.78, respectively, suggesting a moderate improvement in fuel properties.

Figure 9 reveals a linear decrease in O/C and H/C ratios with rising temperature and duration time for two samples. The ratios decreased with prolonged duration, indicating that time also contributes positively to enhancing fuel properties, though its effect is less pronounced than that of temperature. While temperature was the dominant factor in reducing O/C and H/C, extended torrefaction at lower temperatures (e.g., 90 min at 250 °C) achieved atomic ratios comparable to those from shorter treatments at 300 °C (e.g., O/C of 0.50 vs. 0.30 for the 8:2 blend).

For instance, when the temperature was raised from 250 °C to 300 °C at 30 min, the O/C ratio decreased from 0.76 to 0.30 and from 0.72 to 0.30 for the 9:1 and 8:2 blends, respectively, while the H/C ratio dropped from 1.56 to 0.75 and from 1.60 to 0.77. In contrast, at a fixed temperature of 250 °C, increasing the time from 30 to 90 min reduced the O/C ratio from 0.76 to 0.56 and the H/C ratio from 1.56 to 1.14 for the 9:1 blend, and from 0.72 to 0.50 and 1.60 to 1.17 for the 8:2 blend.

Notably, the ratios of the two were initially scattered but converged within the range in the lower left of the diagram in Figure 8 under more severe torrefaction. This convergence demonstrates that torrefaction effectively enhances the homogeneity of samples, making it a more uniform and predictable feedstock for thermochemical conversion processes.

Carbon serves as the primary source of heat release during fuel combustion. Hydrogen also contributes significantly, though its higher content in fuels often coincides with reduced carbon levels. Oxygen in biomass facilitates combustion but lowers the calorific value; overall, higher oxygen and ash contents result in diminished heating value. Compared to coal, biomass generally contains less carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur, but more hydrogen and oxygen. Additionally, its typically higher moisture content leads to a lower calorific value than coal [50].

Torrefaction, however, drives off moisture and volatiles rich in hydrogen and oxygen from cellulose and PVC, while retaining a relatively high proportion of carbon. This induces mild carbonization, rendering the torrefied material more coal-like in composition. For practical applications, the optimal torrefaction conditions—time and temperature—should be determined by balancing process efficiency, fuel quality, and market specifications.

4. Conclusions and Outlook

This study investigated the pretreatment of a biomass–PVC mixture for chlorine removal prior to co-pyrolysis, with a focus on the effects of torrefaction temperature and duration.

- (1)

- This study initiated with a thermodynamic modeling analysis to elucidate the chlorine release behavior during the co-pyrolysis of cellulose and PVC. The simulations identified PVC as the primary source of HCl, with its release predominantly occurring within the temperature range of 115 °C to 288 °C. For cellulose/PVC mixtures, the majority of HCl was released rapidly at the low-temperature stage of 115–200 °C. An increased PVC content (8:2 ratio) promoted more complete dechlorination within this initial stage, while a higher cellulose proportion (9:1 ratio) resulted in a minor secondary release peak at 420–465 °C. These findings provided critical theoretical guidance for the selection of key parameters in subsequent torrefaction experiments. They directly informed the setting of the target temperature above 200 °C to ensure the primary dechlorination reaction occurred and helped optimize the residence time. However, the equilibrium assumption inherent in thermodynamic modeling may lead to deviations from actual processes governed by complex reaction kinetics.

- (2)

- To address the inherent limitations of thermodynamic modeling in capturing kinetic effects, TGA-DTG was employed to experimentally investigate the co-pyrolysis of cellulose and PVC. The results clearly demonstrated that the actual pyrolysis process commenced at approximately 250 °C, notably later than the theoretical prediction, and delineated the distinct, multi-stage decomposition profiles of the individual components. A key finding was the significant synergistic interaction between PVC and cellulose within the overlapping temperature regime of 250–370 °C. The HCl released from PVC decomposition catalyzed the pyrolysis of cellulose, shifting its decomposition to a lower temperature range and resulting in earlier onset and termination temperatures for the co-pyrolysis mixtures compared to the individual components.The TG-FTIR analysis provided clear identification of the chlorine-containing gas release characteristics during the co-pyrolysis of cellulose and PVC. It confirmed that HCl is the primary chlorinated product of PVC pyrolysis, with its main evolution occurring within the 250–400 °C range. A key finding is the distinct behavior observed under co-pyrolysis conditions compared to the individual components: the process initiates HCl release at lower temperatures.

- (3)

- Guided by prior theoretical and thermal analyses, systematic low-temperature torrefaction experiments were conducted on cellulose/PVC mixtures. The results demonstrated that a 9:1 mixture achieved a dechlorination efficiency of 97% at 250 °C for 30 min, significantly outperforming the dechlorination of pure PVC (82.51%). In addition, it achieved a superior dechlorination efficiency of 99% at 300 °C for 90 min. This confirms a pronounced synergistic effect during co-torrefaction. The underlying mechanism involves cellulose-derived radicals facilitating PVC dehydrochlorination, thereby lowering the initiation temperature of dechlorination. Concurrently, the HCl released from PVC acts as an acid catalyst, promoting the dehydration and decomposition of cellulose, which collectively reduces the overall energy barrier of the process. Notably, a higher PVC content (e.g., 8:2 blend) increased chlorine retention in the solid char, suggesting the presence of a competing pathway where chlorine-containing intermediates recombine with the char matrix. Compared to existing methods, this work achieved superior dechlorination at lower temperatures (≤250 °C), highlighting the technical advantage of the synergistic co-torrefaction process.

- (4)

- The fuel properties of the torrefied solids, evaluated via a PLS regression model based on elemental composition, demonstrated significant enhancement. Torrefaction promoted carbon enrichment by releasing volatiles and decomposing oxygenated structures, leading to a marked increase in the Higher Heating Value (HHV). However, this improvement in HHV was achieved at the expense of substantial mass loss, revealing a characteristic trade-off. The gains in HHV diminished under more severe conditions (e.g., at 300 °C), while the solid yield and energy yield continued to decrease. Although the 8:2 blend could achieve a comparable maximum HHV to the 9:1 blend, its greater mass loss resulted in a lower final energy yield. Consequently, to optimize the balance between fuel quality and mass retention for blends, employing milder torrefaction parameters (temperature ≤ 250 °C and duration ≤ 30 min) is identified as the preferred strategy.

- (5)

- Analysis via the Van Krevelen diagram elucidated the substantial improvement in fuel properties induced by torrefaction. A marked decrease in both H/C and O/C atomic ratios was observed with increasing severity of torrefaction temperature and time. This transformation shifted the fuel properties of the torrefied solids from raw biomass towards the region characteristic of lignite or sub-bituminous coal, effectively mimicking a mild coalification process. Temperature exerted a more pronounced influence on these atomic ratios than residence time. Notably, under severe conditions, the data points for different blend ratios (9:1 and 8:2) converged in the diagram, demonstrating that torrefaction effectively enhances the homogeneity of the products, yielding a more uniform and predictable feedstock. In summary, torrefaction promotes carbon enrichment and energy density by selectively removing hydrogen and oxygen, thereby upgrading the fuel quality of the solid products.

- (6)

- While this study provides insights into dechlorination during torrefaction under pyrolysis conditions, the characteristics under gasification environments, specifically with steam or CO2 as the medium, represent a critical area for future research.It should be noted that this study focused specifically on cellulose–PVC blends; other biomass or plastic types (e.g., lignin or polyethylene) may exhibit different synergistic behaviors. Furthermore, thermodynamic simulations using software such as HSC, CHEMKIN, or FactSage are valuable for predicting dechlorination performance, even with complex feedstock compositions.A detailed techno-economic and energy consumption analysis is an essential and planned direction for our future work, paving the way for potential industrial applications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pr13113543/s1, Table S1: Chlorine-containing Phases Included in the Thermodynamic Equilibrium Model; Table S2: Other Phases Included in the Thermodynamic Equilibrium Calculation for a 9:1 Cellulose-to-PVC Ratio.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z.; methodology, L.W.; validation, M.C.; formal analysis, Z.Z.; investigation, Z.Z.; resources, L.W.; data curation, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; writing—review and editing, M.C.; supervision, Z.Z.; project administration, L.W.; funding acquisition, L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Six Top Talent Peaks Project in Jiangsu Province (JNHB-039) and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Fund of Jiangsu Province (CX (20)3075).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Nanjing Tech University for providing me with a research platform and technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Energy Institute. Statistical Review of World Energy; Energy Institute: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.H.; Zhang, H.T.; Wang, B.; Ding, Y.T. Towards a Synergistic Future: The Impact of Power Sector Decarbonization on Sustainable Development Goals in China. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2025, 56, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konyannik, B.Y.; Lavie, J.D. Valorization Techniques for Biomass Waste in Energy Generation: A Systematic Review. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 435, 132973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biomass Energy Industry Branch of China Association of Industrial Development (CAID). In 2025 China Biomass Energy Industry Annual Report; CAID: Beijing, China, 2025.

- Kakimova, A.B.; Sadvakasova, A.K.; Kossalbayev, B.D.; Zadneprovskaya, E.V.; Xu, T.; Zaletova, D.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. In Silico Design of Biomass-to-Hydrogen Pathways: A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 173, 151327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, R.; Kwong, P.; Ahmad, E.; Nigam, K.D.P. Clean Syngas from Small Commercial Biomass Gasifiers; A Review of Gasifier Development, Recent Advances and Performance Evaluation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 21087–21111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Carlson, T.R.; Xiao, R.; Huber, G.W. Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis of Wood and Alcohol Mixtures in a Fluidized Bed Reactor. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.T.; Mu, G.T.; Zhang, Z.M.; Luo, W.M. Research on the spatio-temporal variation of agricultural film usage in China and the effect of threshold crop yield. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 36857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jędrzejczyk, M.; Górecka, S.; Pacultová, K.; Grams, J. Efficient Dual-Bed Co-Pyrolysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass and Plastic to Hydrogen-Rich Gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 165, 150770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.R.; Alves, J.L.F.; Franco, F.I.A.; Melo, D.M.A.; Braga, R.M. Recent Advances in Co-Pyrolysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass with Plastic Waste as a Sustainable Waste-to-Energy Solution Toward a Low-Carbon Economy: A Bibliometric Review of the Last 5 Years of Research. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2025, 192, 107279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strezov, V.; Zhou, X.T.; Evans, T.; Kan, T.; Taylor, M.P. Investigation of the Effect of Chlorine in Different Additives on Dioxin Formation During High Temperature Processing of Iron Ore. Ecotox. Environ. Saf. 2024, 288, 117406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Liu, Z.D.; Cheng, K.H.; Kong, Y. Chlorine-Induced High-Temperature Corrosion Characteristics of Ni-Cr Alloy Cladding Layer and Ni-Cr-Mo Alloy Cladding Layer. Corros. Sci. 2023, 216, 111102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisher, M.; Shah, D.; Shah, D.; Izquierdo, M.; Ybray, S.; Sarbassov, Y. Synergistic Effects of Cl-Donors on Heavy Metal Removal During Sewage Sludge Incineration. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10, 100876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Q.; Borjigin, S.; Kumagai, S.; Kameda, T.; Saito, Y.; Yoshioka, T. Machine learning-based discrete element reaction model for predicting the dechlorination of poly(vinyl chloride) in NaOH/ethylene glycol solvent with ball milling. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 2020, 3, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.S.; Ge, Y.; He, Q.; Chen, P.W.; Xiao, H.M. The Redistribution and Migration Mechanism of Chlorine during Hydrothermal Carbonization of Waste Biomass and Fuel Properties of Hydrochars. Energy 2022, 244, 122578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.L.; Ma, X.Q.; Chen, X.F.; Yao, Z.L.; Zhang, C.Y. Co-Hydrothermal Carbonization of Polyvinyl Chloride and Corncob for Clean Solid Fuel Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 301, 122763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Z.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, L.F.; Xu, L.F.; Yang, J.C.; Shen, B.X. Study on the Regulation Mechanism of Torrefaction Pretreatment on Fuel Quality and Pyrolysis Characteristics of Rice Husk. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2023, 51, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramochi, H.; Nakajima, D.; Goto, S.; Sugita, K.; Wu, W.; Kawamoto, K. HCl Emission During Co-Pyrolysis of Demolition Wood with a Small Amount of PVC Film and the Effect of Wood Constituents on HCl Emission Reduction. Fuel 2008, 87, 3155–3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, I.; Tomic, T.; Katancic, Z.; Erceg, M.; Papuga, S.; Vukovic, J.P.; Schneider, D.R. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Mechanically Non-Recyclable Waste Plastics Mixture: Kinetics and Pyrolysis in Laboratory-Scale Reactor. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 296, 113145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraveas, C. Production of Sustainable and Biodegradable Polymers from Agricultural Waste. Polymers 2020, 12, 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese National Standard GB/T 3558-2014; Determination of Chlorine in Coal. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2014.

- Hassan, N.S.; Jalil, A.A.; Hitam, C.; Vo, D.V.N.; Nabgan, W. Biofuels and Renewable Chemicals Production by Catalytic Pyrolysis of Cellulose: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 1625–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.J. Effects of Co-Pyrolysis of Typical Municipal Solid Waste Components on Tar Formation and Catalytic Cracking. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Han, B. Study on Pyrolysis Characteristics and Kinetics of Polyvinyl Chloride and Other Plastic Wastes. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aboulkas, A.; Harfi, K.E. Co-Pyrolysis of Olive Residue with Poly(Vinyl Chloride) Using Thermogravimetric Analysis. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2009, 95, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Sun, L.S.; Ma, C.; Qiao, Y.; Yao, H. Thermal Degradation of PVC: A Review. Waste Manag. 2016, 48, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Huang, Q.X.; Bourtsalas, A.T.; Chi, Y.; Yan, J.H. Synergistic Effects on Char and Oil Produced by the Co-Pyrolysis of Pine Wood, Polyethylene and Polyvinyl Chloride. Fuel 2018, 230, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.T.; Hu, J.H.; Zhao, Y.J.; Yan, S.H.; Yang, H.P.; Chen, H.P. Synergistic Characteristics of Biomass and Waste Plastic During Co-Pyrolysis. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2020, 48, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzawa, Y.; Ayabe, M.; Nishino, J. Acceleration of Cellulose Co-Pyrolysis with Polymer. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2001, 71, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.Y.; Wang, B.; Ji, Y.Y.; Xu, F.F.; Zong, P.J.; Zhang, J.H.; Tian, Y.Y. Thermal Decomposition of Castor Oil, Corn Starch, Soy Protein, Lignin, Xylan, and Cellulose During Fast Pyrolysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 278, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.L.; Chen, T.J.; Luo, X.T.; Han, D.Z.; Wang, Z.Q.; Wu, J.H. TG/FTIR Analysis on Co-Pyrolysis Behavior of PE, PVC and PS. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.F.; Wang, B.; Yang, D.; Hao, J.H.; Qiao, Y.Y.; Tian, Y.Y. Thermal Degradation of Typical Plastics Under High Heating Rate Conditions by TG-FTIR: Pyrolysis Behaviors and Kinetic Analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 171, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.L.; Zhao, P.T.; Cui, X.; Geng, F.; Guo, Q.J. Kinetics Study on Hydrothermal Dechlorination of Poly (Vinyl Chloride) by In-Situ Sampling. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 23, 101703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Ho, S.H.; Chen, W.H.; Xie, Y.P.; Liu, Z.Q.; Chang, J.S. Torrefaction Performance and Energy Usage of Biomass Wastes and Their Correlations with Torrefaction Severity Index. Appl. Energy 2018, 220, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.P.; Hoang, A.T.; Ölçer, A.I.; Engel, D.; Pham, V.V.; Nayak, S.K. Biomass-Derived 2,5-Dimethylfuran as a Promising Alternative Fuel: An Application Review on the Compression and Spark Ignition Engine. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 214, 106687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.B.; Gui, B.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W.X.; Yao, H.; Yu, Y.; Xu, M.H. Understanding the Pyrolysis Mechanism of Polyvinylchloride (PVC) by Characterizing the Chars Produced in a Wire-Mesh Reactor. Fuel 2016, 166, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Y.; Wu, Y.F.; Wang, D.C.; Jin, L.J.; Hu, H.Q. Synergistic Effect during Co-Pyrolysis of Pre-Dechlorinated PVC Residue and Pingshuo Coal. J. Fuel Chem. Technol. 2021, 49, 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Hui, H.L.; Li, S.G.; Du, L. Study on Preparation of Aromatic-Rich Oil by Thermal Dechlorination and Fast Pyrolysis of PVC. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 173, 105817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.K.; Yu, D.X.; Luo, L.; Du, S.J.; Wang, S.Z.; Yu, X.; Liu, F.Q.; Wang, Y.C. Enhanced Thermal Dechlorination of Low-Rank Fuels with Wet Flue Gas. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2023, 171, 105947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.H.; Niu, S.L.; Zhu, J.; Geng, J.; Liu, J.S.; Han, K.H.; Wang, Y.Z.; Xia, S.W. Stepwise Dechlorination and Co-Pyrolysis of Poplar Wood with Dechlorinated Polyvinyl Chloride: Synergistic Effect and Products Distribution. J. Energy Inst. 2024, 117, 101819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Yi, L.L.; Li, K.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Li, A.J.; Wang, T.R.; Zou, Y.Y.; Li, X.; Yao, H. Enhanced Dechlorination for Multi-Source Solid Wastes Using Gas-Pressurized Torrefaction and Its Removal Mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 159906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, A.; Padouvas, E.; Rotter, H.; Varmuza, K. Prediction of heating values of biomass fuel from elemental composition. Anal. Chim. Acta 2005, 544, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, W.H.; Ho, S.H.; Zhang, Y.; Lim, S. Comparative Advantages Analysis of Oxidative Torrefaction for Solid Biofuel Production and Property Upgrading. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 386, 129531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becidan, M.; Várhegyi, G.; Hustad, J.E.; Skreiberg, Ø. Thermal Decomposition of Biomass Wastes. A Kinetic Study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 2428–2437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H. An Evaluation on Improvement of Pulverized Biomass Property for Solid Fuel. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 3636–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousset, P.; Aguiar, C.; Labbé, N.; Commandré, J. Enhancing the Combustible Properties of Bamboo by Torrefaction. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 8225–8231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phanphanich, M.; Mani, S. Impact of Torrefaction on the Grindability and Fuel Characteristics of Forest Biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 102, 1246–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L. Study on Torrefaction and Products Adsorption of Rice Straw Under Different Oxygen Concentrations. Ph.D. Thesis, Southeast University, Nanjing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Qiao, Y.; Gui, B.; Wang, C.; Xu, J.Y.; Yao, H.; Xu, M.H. Effects of Chemical Forms of Alkali and Alkaline Earth Metallic Species on the Char Ignition Temperature of a Loy Yang Coal under O2/N2 Atmosphere. Energy Fuel 2012, 26, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.M.; Lee, W.J.; Chen, W.H.; Liu, S.H.; Lin, T.C. Torrefaction and Low Temperature Carbonization of Oil Palm Fiber and Eucalyptus in Nitrogen and Air Atmospheres. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 123, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).