Abstract

The study presents an integrated stochastic modeling framework that combines Markov chains and queuing theory to optimize production efficiency in a metallurgical machining process. The model captures the dynamic behavior of key manufacturing stages, milling, drilling, reaming, and packing, by representing rework, inspection, and waste as distinct probabilistic states. Effective arrival rates and service rates are computed to evaluate machine utilization, total processing time, and throughput. The proposed approach was applied to an industrial case study, where the results showed that reprocessing activities increased the total cost per conforming unit by approximately 0.3% and affected overall system performance. By adjusting machine allocation and minimizing rework probabilities, the model demonstrated measurable improvements in cycle time and cost efficiency. This integrated methodology provides a practical decision-support tool for optimizing production flow, balancing resource utilization, and reducing the financial impact of nonconformity in continuous manufacturing environments.

1. Introduction

In the competitive landscape of modern manufacturing, achieving cost efficiency while maintaining high production standards is a critical challenge. Series production lines, characterized by their sequential processing stages, are particularly susceptible to inefficiencies arising from variable processing times, rework, and waste, all of which can significantly impact overall production costs. To address these issues, advanced stochastic modeling techniques, specifically the use of Markov chains and queuing theory, have emerged as essential tools for optimizing production dynamics and enhancing cost efficiency [1,2,3,4]. This approach allows for a detailed analysis of state transitions, system bottlenecks, and resource utilization, providing manufacturers with the insights needed to enhance productivity and reduce operational costs [5,6].

Markov chain models play a crucial role in representing the stochastic nature of production systems, particularly in series production where product flow, rework, and quality control are critical. These models enable the prediction of various operational states, such as rework and waste, and their probabilities, thereby helping to identify and mitigate factors that lead to increased production costs [7]. For instance, Seals et al. [1] demonstrated the effectiveness of Markov chains in modeling the impact of disruptions on production efficiency, underscoring their value in maintaining smooth production flow and cost control. Similarly, Papadopoulos and Heavey [8] highlighted the importance of Markov models in understanding the behavior of complex production systems, providing a foundation for optimizing costs in series production environments [9]. Additionally, the application of Markov chains in dynamic scheduling and maintenance has shown significant potential in reducing operational costs through more efficient management of production resources and predictive maintenance strategies [10].

Queuing theory complements Markov chains by offering a detailed analysis of workstation performance within a production line, particularly in terms of arrival rates, service times, and queue lengths [11,12,13]. Through the application of queuing aspects, researchers have been able to identify potential bottlenecks and optimize resource allocation to enhance throughput and reduce wait times [14,15,16]. For example, Shanthikumar [17] demonstrated the effectiveness of queuing theory in managing work-in-process inventories and balancing queue times with system utilization, particularly in closed queuing networks with blocking. Recent advancements, such as the incorporation of finite capacity queues and phase-type distributed processing times, have enabled more accurate performance predictions in both software architectures and manufacturing systems, emphasizing the critical role of queuing theory in optimizing operational efficiency [18,19,20,21]. These improvements contribute directly to cost efficiency by reducing idle times, minimizing rework, and ensuring optimal use of production resources [22,23,24,25].

The use of Markov chains into queuing theory is particularly advantageous in the context of series production dynamics, where the interplay between stochastic processes and deterministic service mechanisms determines overall system performance and cost efficiency [26,27].

This combined approach allows for a holistic analysis of production processes, capturing both the variability of state transitions and the impact of queue dynamics on resource utilization [25,28,29]. For instance, Mailliez et al. [28] explored the use of decision support systems (DSS) in scheduling and rescheduling operations, demonstrating how such systems enhance adaptability and resource allocation in response to disruptions and uncertainties, leading to significant cost savings. Similarly, Saghafian et al. [29] developed an Ambiguous Partially Observable Markov Decision Process (APOMDP) framework to address decision-making under ambiguity in Markov processes, improving the robustness of production systems by accounting for uncertainties in probabilistic transitions and optimizing resource allocation to reduce inefficiencies. These studies illustrate how combining stochastic models with decision-support and uncertainty-management techniques strengthens the analytical capability of manufacturing optimization frameworks. The use of these models has also proven effective in optimizing quality control processes, reducing non-conformity costs, and improving overall product quality, further contributing to cost efficiency in series production [28,29,30].

Despite the advancements in use Markov chains and queuing theory, there remains a need for more comprehensive models that address the specific challenges of series production lines, particularly in achieving cost efficiency. Many existing models focus on specific aspects of production optimization, such as inventory management or quality control, without considering the broader system interactions and dependencies that are crucial for a comprehensive understanding of production dynamics [20,21,30]. This paper aims to bridge this gap by presenting a novel methodology that seamlessly combines Markov chain modeling with queuing theory to analyze and optimize continuous production systems comprehensively. The proposed model incorporates various factors such as quality inspections, reprocessing requirements, and workstation performance, providing a nuanced understanding of production processes that can lead to significant improvements in system performance and cost efficiency [5,6,14].

The application of stochastic models in manufacturing has been further advanced by integrating Markov processes with complementary analytical frameworks to address system complexity. For example, Blokus and Kołowrocki [31] developed reliability strategies for aging-dependent systems, introducing multistate models with component dependency to capture degradation and repair dynamics. Fuzzy theory has been incorporated into stochastic frameworks to handle uncertainty beyond randomness, particularly in logistics evaluation, maintainability, and risk modeling [32,33,34]. Romaniuk [35] extended this integration by combining semi-Markov processes with fuzzy parameters and stochastic interest rate models, embedding the value of money over time into maintenance cost simulations. Beyond fuzzy integration, multi-model Markov decision processes have been proposed to address parameter ambiguity and decision-making under uncertainty [30,36], while El-Awady and Ponnambalam [37] demonstrated how Markov chains can be combined with simulation and Bayesian networks for robust probabilistic failure analysis. Together, these approaches illustrate the versatility of Markovian modeling when extended with fuzzy logic, economic considerations, or hybrid simulation frameworks, thereby motivating the practical and extensible methodology presented in this study.

In this sense, Markov chains and queuing theory offers a robust framework for optimizing series production systems, addressing the complexities of modern manufacturing processes while enhancing cost efficiency. By leveraging the strengths of both modeling approaches, this study provides a comprehensive tool for analyzing state transitions, optimizing resource allocation, and improving overall system performance. The findings and methodologies presented herein not only build upon the extensive body of existing literature but also introduce new dimensions of analysis that are crucial for tackling the dynamic challenges of continuous production systems. As manufacturing environments continue to evolve, the adoption aspects and models of Markov-queuing will be instrumental in achieving sustainable efficiency, quality, and cost-effectiveness, thereby driving innovation and competitiveness in the industry.

While the underlying principles of Markov chains and queuing theory are individually well-established, the main contribution of this study lies in their integration into a unified and practical framework for series production systems. This approach explicitly models the interplay between operational states, such as quality inspection, rework, and waste, and their impact on system performance. The novelty of this methodology is its capacity to provide a holistic analysis, enabling the simultaneous evaluation of multiple critical performance indicators, including production efficiency, machine utilization, non-conformance rates, and final cost per unit. By capturing these interdependencies within a single framework, the study extends beyond conventional analyzes that examine such factors in isolation, offering a more comprehensive and practice-oriented decision-support tool.

2. Methodology

This study applies Markov chain modeling and queuing theory to analyze and optimize a production system, building on previous research that has demonstrated the effectiveness of these techniques in manufacturing environments [8,13,25]. The methodology focuses on decision-making under uncertainty, leveraging the characteristics of Markov chains, where future states depend only on the current state, independent of past events [38]. The following sections describe the key concepts and steps involved in applying this approach.

2.1. Markov Chain Model

Markov chains are utilized to represent the stochastic behavior of the production system, drawing on established methods for analyzing state transitions in manufacturing processes [21]. The model incorporates a finite number of states with stationary transition probabilities, meaning these probabilities remain constant over time. The probability represents the likelihood that the system will transition from state at time to state at time .

Types of State

Transient State: A state is transient if, after entering it, the system has a possibility of moving to another state and never returning. This concept is critical in understanding how disruptions can lead to inefficiencies in production systems [20].

Recurrent State: A state is recurrent if, after entering it, the system is guaranteed to return to this state eventually. In other words, a state is recurrent if it is not transient [8].

Absorbing State: A state is said to be absorbing if, once the system enters this state, it remains there indefinitely, meaning that the probability of transitioning out of it is zero () [9]. In the context of production systems, absorbing states represent the final stages where no further processing occurs. For instance, in a machining line, once a piece reaches the packing stage (a conforming product) or the disposal stage (a defective or nonconforming product), it exits the production flow and does not re-enter any preceding operation. These states effectively capture the completion or termination of the process, allowing the model to estimate the probabilities of producing conforming units versus waste.

These states are used to construct the transition matrix, which is further broken down into the following submatrices: , where identity () matrix represents transitions between absorbing states, where each absorbing state has a probability of 1; zero () matrix indicates no transitions between absorbing and non-absorbing states; matrix shows the probability of transitioning from a non-absorbing state to an absorbing state in one step and; Q matrix represents the probability of transitioning from one non-absorbing state to another non-absorbing state in one step.

The fundamental matrix is calculated using Equation (1) [13,39]:

The diagonal elements of provide the expected number of visits to each state. Using and the matrix, it is possible to calculate the matrix , which gives the long-term probabilities of each non-absorbing state eventually reaching each absorbing state:

The results from the matrix describe the next steps in the queuing analysis for each stage.

2.2. Queue Theory

To evaluate the performance of each stage in the system, particularly those with a visit number greater than one, queuing theory is applied. This analysis builds on prior research that has successfully applied queuing to optimize production line efficiency [9,23,24]. The focus here is on two key aspects: workload and the number of servers required at each stage.

The system starts with an average arrival rate (e.g., in production units per unit time). For non-absorbing states, the total arrival rate on a phase is calculated as:

where represents the average number of visits to stage .

Next, the optimal number of servers required per stage is determined to ensure that there is a good service. The service rate is calculated using Equation (4) [2,11]:

The number of servers needed at stage is then calculated as:

After obtaining the values of , and , the workload at each station is evaluated in detail, which is further illustrated in the case study presented in the next section.

The primary methodological contribution of this study is the development of a structured framework that integrates stochastic modeling (Markov chains), operational efficiency analysis (queuing theory), and a conceptual simulation-based validation layer. This integration transforms well-established mathematical tools into a cohesive process explicitly designed to capture the dynamics of series production systems. Rather than introducing new mathematical formulations, the methodology adapts and extends existing techniques to systematically address interrelated factors such as rework, inspection, resource allocation, and cost variability. By doing so, it provides a bridge between theoretical analysis and practical implementation, equipping managers and engineers with actionable insights to improve decision-making in manufacturing environments.

The proposed methodology addresses this by focusing on generalizable principles rather than task-dependent details. Specifically, it provides a framework that can be adapted to different contexts through parameterization (e.g., adjusting input data, probability distributions, or performance measures), while keeping the core logic consistent.

2.3. Case Study

This section presents a case study to illustrate the applicability of the Markov-queuing approach in metallurgical industry. The study focuses on a machining process characterized by sequential operations, rework, and quality inspections [16,29,40].

2.4. Process Description

The machining process in a metallurgical industry company features a manufacturing network where pieces enter at a rate of 500 pieces per hour, following a Poisson distribution. Initially, the pieces undergo the milling operation (S1), which has an average processing time of 0.005 h per piece. After milling, the pieces are distributed with a 39.9% probability to the drilling operation (S2) and a 60% probability to the reaming operation (S4), as possibility to obtain a rate of defect (0.01%). Reaming is a machining process performed to achieve a high-quality surface finish. Upon completion of either operation, the pieces must pass an inspection. After the drilling operation, pieces have a 5% probability of being disposed of, a 10% probability of returning to the previous state (requiring reprocessing), and the remaining 85% continue to the packing operation.

If reprocessing is required after the drilling stage, the piece returns to the reprocessing stage (S3), which is identical to the milling stage. A different state (S3) is designated because if a piece returns to S1, it could potentially move to S4, which is not desirable in the process. After reprocessing, the piece either returns to the drilling stage (S2) with a 7% probability or proceeds directly to the packing stage (S6).

The disposal stage (S5) represents the process in which defective or nonconforming pieces that cannot be reprocessed are removed from the production flow. These pieces are either scrapped or directed for material recovery, depending on their condition and the company’s recycling policy. This stage plays a crucial role in quantifying waste, estimating the recovery rate of materials, and determining the associated disposal costs, all of which contribute to evaluating the overall efficiency and sustainability of the production system.

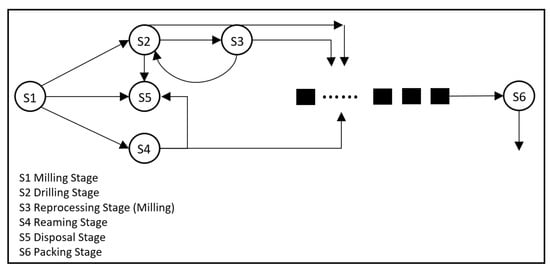

In the reaming operation, pieces have a 3% probability of being disposed of, while the remaining pieces continue to the packing stage. Packing is a single section that receives pieces from both the drilling and reaming operations. The average packing time per piece is 0.005 h, the average drilling time per piece is 0.01 h, and the average reaming time is 0.008 h per piece. In the company, service times are exponentially distributed. Additionally, the processing cost for milling, drilling, and reaming stages is $200 per piece. The reprocessing cost for both the drilling and milling stages is $30 per piece, and units that are disposed of are sold for $10 per piece. The machining process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Markov chain representation of the production system (Machining Process). S1: Milling stage; S2: Drilling stage; S3: Reprocessing stage (milling); S4: Reaming stage; S5: Disposal or waste stage; S6: Packing stage. The arrows indicate possible transitions between stages, including direct disposal paths. For instance, the transition from S1 to S5 represents the case where defects are detected immediately after milling, leading to scrapping without additional processing.

In this case study, the company aims to determine the average number of pieces that are packaged per hour. Additionally, the study seeks to identify the optimal number of machines required at each stage of the process. The company also needs to assess the processing time for each type of item, those that undergo drilling and those that undergo reaming, as well as the average cost per piece that meets specifications. Furthermore, a comparison is made between the average cost per unit with reprocessing and without reprocessing to understand how this factor impacts the unit cost.

In the calculation of the total processing time, waiting times in queues were not explicitly included. This assumption was made to focus on the effective processing durations at each workstation and to isolate the impact of reprocessing and quality-related transitions on system dynamics. However, since the number of machines is finite, it is expected that some parts will experience delays while waiting for service. This exclusion represents a limitation of the current model, as it may lead to an underestimation of the actual production lead time. To address this, future extensions should incorporate queuing delays more explicitly, either by refining the analytical model with aspects of queuing theory results or by employing discrete-event simulation to account for stochastic variability in arrivals, service times, and machine availability. The goal was to design an appropriate queuing system based on the average arrival rate and service rate, ensuring that the fundamental balance equation is satisfied. This equation must be met to ensure that the system can meet demand and operate in a steady state. Additionally, the cost analysis provides insight into the negative impact of reprocessing and non-conformity on the average cost per piece that meets specifications.

All computational experiments were performed on a standard workstation equipped with an Intel ® CoreTM i7 processor (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) running at 2.4 GHz, 16 GB of RAM, and a 64-bit operating system. The integrated model was implemented and solved using LINGO® software, version 18.0 (LINDO Systems Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The proposed analytical approach demonstrated high computational efficiency, which is a key criterion for practical application. For medium-size instances that involved analyzing the flow of up to 10,000 products, the average execution times to obtain a complete solution for all system metrics ranged between 2.3 and 4.7 s. This rapid solution time is an inherent advantage of the analytical framework. The method relies on solving a system of linear equations to analyze the Markov chain and applying direct queuing formulas, which is conceptually and computationally faster than iterative or stochastic methods like discrete-event simulation. A simulation-based approach would require numerous replications and significantly longer run times to achieve stable and statistically significant results. While memory usage was not explicitly tracked, it was not a limiting factor for the problem sizes considered. This high efficiency makes the proposed methodology a practical and accessible tool for managers and engineers to conduct rapid strategic analysis and evaluate “what-if” scenarios without requiring specialized high-performance computing resources. The model was executed in Simmer (is a Cram) of R Software® (version 4.3.2).

2.5. General Methodological Framework for Industrial Application

To facilitate industrial implementation, a general methodology is proposed that structures the integration of Markov chains and queuing theory into a systematic framework applicable to diverse production environments. This methodology provides practitioners with a clear roadmap, from data collection to performance evaluation, ensuring that the approach can be adapted across industries for effective decision-making in production planning, resource allocation, and cost optimization.

The proposed methodology is organized into interrelated phases, where the output of one phase serves as the foundation for the next, ensuring a coherent and iterative modeling process:

- System Definition and Mapping: Conduct a comprehensive analysis of the production line, mapping the process flow, operational stages, inspection points, and all possible outcomes (e.g., successful completion, reprocessing loops, or disposal).

- Markov Chain Model Development: Construct the Markov chain representation of the system, defining operational stages and outcomes as states. Transition probabilities are derived from production data and compiled into the transition matrix, which mathematically represents the stochastic dynamics of the system.

- System State Analysis: Use the transition matrix to calculate the fundamental matrix (N), indicating the expected number of visits to each state before absorption. The absorption probability matrix (B) is then derived, determining the likelihood of products reaching absorbing states such as packaging (conforming units) or disposal (non-conforming units).

- Integration of Queuing aspects and Elements: Combine the Markov outputs with queuing theory by estimating the effective arrival rate (λtotal) at each workstation, accounting for both initial entries and re-entries from rework loops. Service rates (μ) are defined from average processing times, enabling the configuration of queuing models that capture congestion and resource utilization.

- Resource Optimization: Based on the queuing model, calculate the minimum number of machines or servers required per stage to ensure service capacity meets or exceeds effective arrival rates. This prevents bottlenecks and enables production to operate under steady-state conditions.

- Validation and Sensitivity Analysis: Complement the analytical framework with simulation-based experiments to evaluate robustness under stochastic variability and test “what-if” scenarios. Sensitivity analysis of key parameters (e.g., defect rates, reprocessing probabilities, service times) enhances confidence in the model’s predictions and adaptability to uncertainty. The risk of “curse of dimensionality” in our is mitigated by focusing on aggregated states and by applying structural assumptions that reduce the dimensionality of the transition matrix. This ensures that the methodology remains computationally feasi-ble while still capturing the essential dynamics of the production system only with six states.

- Performance and Cost Evaluation: Finally, assess overall system performance in terms of throughput, cycle time, and resource utilization, coupled with a cost analysis that quantifies the effects of reprocessing and non-conformity.

This structured methodology provides both systematic conceptualization and practical adaptability, positioning the integrated Markov-queuing approach as a decision-support tool that can guide industrial practitioners in diagnosing system inefficiencies, optimizing configurations, and reducing costs in real-world manufacturing contexts.

A key strength of the proposed integrated methodology lies not in its rigidity as a single, universal model but in its adaptability as a generalizable framework for analyzing series production systems. Each manufacturing process—whether involving machining, assembly, or inspection, has distinct operational constraints, yet the underlying analytical challenges remain comparable: managing process flow, controlling rework, balancing machine utilization, and minimizing costs. The framework provides a systematic sequence of steps that can be flexibly adapted to specific industrial contexts, ensuring both consistency and relevance in application. The adaptability of the framework emerges from its modular structure. In the System Definition and Mapping phase, the states of the Markov chain are defined based on the actual stages, inspection points, and rework loops of the production line being analyzed. This ensures that the model architecture accurately mirrors the system’s real operational logic. In the Data-Driven Parameterization stage, transition probabilities and service rates (μ) are derived directly from empirical data, either from production records or direct observation, allowing the model to represent the specific dynamics and performance characteristics of the environment under study. Finally, in the Scalability dimension, the framework can be applied to systems of varying complexity, ranging from simple linear processes to more intricate multi-node networks that include concurrent or feedback pathways.

It is also important to recognize the inherent trade-off between model precision and implementation effort. The analytical approach adopted here, grounded in classical Markovian and queuing theory assumptions (e.g., stationary probabilities, exponential service times), provides a high level of interpretability and computational efficiency. This makes it particularly well suited for strategic analysis, where rapid, data-informed insights are required to support decision-making in production planning and resource allocation. While this approach may abstract certain nonlinear dependencies or non-exponential service behaviors, its simplicity enables practical application and fast evaluation of alternative configurations. For applications requiring more detailed modeling—such as capturing machine degradation effects, dynamic feedback loops, or non-Poisson arrivals—the analytical results can be complemented with discrete-event simulation or hybrid stochastic modeling. This layered strategy allows practitioners to begin with a manageable analytical framework for diagnosis and decision support, and later refine the analysis using higher-fidelity tools as needed. Thus, the proposed methodology achieves an effective balance between general applicability and contextual specificity, offering a scalable approach to performance assessment and optimization across diverse industrial environments.

3. Results and Discussion

Firstly, the transition matrix is presented in order to calculate the fundamental matrix () and identify probabilities that in time each non-absorbent state reach each absorbent state (). Thereby, the matrix is essential for understanding the behavior of the system and is calculated as follows.

In order to know and the probabilities that non-absorbent states reach each absorbent state is required to identify the matrix (represents the probability of passing from a non-absorbent state to a non-absorbent state in one step) and the matrix (represents the probability of passing from a non-absorbent state to an absorbent state in one step) in the transition matrix. Using this transition matrix, we derive the and matrices:

After developing the respective calculations to find and the probabilities that non-absorbent states reach each absorbent state. The fundamental matrix is then computed:

The matrix , which represents the long-term probabilities of non-absorbing states reaching absorbing states, is calculated as follows:

The main diagonal of the fundamental matrix represents the average number of visits per piece in each stage of the process, where a value greater than 1 represents that on average a unit revisits the state, where a value greater than 1 on the main diagonal indicates that a unit, on average, revisits that stage. The value 0.962, taken from the absorption probability matrix (B), represents the overall probability that a piece will be successfully packaged as a conforming product. This probability incorporates the combined effects of reprocessing and disposal loops and is therefore not derived from a simple linear equation, but rather results from the comprehensive Markov chain calculations. Additionally, the average number of visits cannot be less than 1 because this value is based on the pieces that effectively reach the state rather than those initially programmed. Therefore, it is necessary to differentiate the results of the main diagonal and of the other values of the fundamental matrix. The values on the main diagonal represent the average number of visits to a state for the pieces that actually reach that stage, while the other values in the matrix represent the average number of visits relative to the initial number of pieces that entered the system. Firstly, the calculations to identify the optimal number of machines in each state and the number of pieces that are packaged per hour are presented below. For this it is required to find the total arrival rate () that really reaches each state.

In this case, is equal to because each piece passes only once to the first state. Then, the values of the total arrival rate of the other states are presented.

Replacing (9) in (8), the following equation is derived.

As shown in Figure 1, after the processing in the stage 3, the piece has a chance to be returned to the stage 2. When this situation occurs, an increase in the that really reaches the stage is generated, known as . Therefore, reprocessing is what generates that the increases, originating in the same way an increase in the times and costs for reprocessing. After calculating and , the next step is to calculate the total arrival rates at the reaming and packaging stages.

Additionally, the value obtained from represents the number of pieces packaged per hour as it relates to the probability of arriving pieces at packing stage (S6) that were programmed at the beginning of the process (S1). This probability is presented in the B matrix.

After calculating the total arrival rates, the next step is to determine the optimal number of machines required at each stage. The results are presented in Table 1. The service rate is calculated using the equation below. The average length of service, which represents the processing time per piece, varies depending on the specific stage of the production process.

Table 1.

Optimal Number of Machines per Stage.

In the calculation of total processing time, waiting time was not explicitly included, as the model primarily focuses on the effective processing duration at each stage. However, since machine capacity is finite, queuing effects may introduce additional delays. This simplification should be considered when interpreting the results, as it may lead to a slight underestimation of total lead time. Future work could integrate simulation or queuing-based extensions to capture these delays more accurately.

The company requires these results to determine how the system’s structure should be designed to meet demand by accurately calculating the total arrival rate for each stage of the process. Regarding the milling stage discussed in the previous table, it is important to note that the total arrival rate for the milling operation is the sum of and , where represents the pieces that re-enter the milling stage after passing through the reprocessing stage. Additionally, the company needs to understand the total processing time for each type of final product, based on the previous calculations. The procedure for determining these total times is presented in Table 2 and Table 3 below.

Table 2.

Total Processing Time (Drilling Stage).

Table 3.

Total Processing Time (Reaming Stage).

The results are crucial for the company as they enable a reactive approach to meeting demand while understanding the total processing time based on the type of product being manufactured. Achieving this involves satisfying the fundamental balance equation, which ensures an optimal configuration of workstations tailored to the company’s needs. Additionally, cost-related aspects can be analyzed more effectively by considering the total arrival rates and the associated processing and reprocessing costs at each stage. The following Table 4 presents an analysis of these costs, including a comparison of the average cost per unit with and without reprocessing.

Table 4.

Average Cost (in USD) per Unit to Spec with and without Reprocessing Condition.

Table 4 shows that the average cost per unit that meets specifications is higher when reprocessing is required. This increase occurs because the reprocessing costs are incorporated into the average cost per unit, raising the overall cost of producing a unit that proceeds to the packing stage. Therefore, the company should aim to reduce the percentage of units that require reprocessing. A similar situation arises with units that are sent to the disposal stage. These units are processed in earlier stages and then discarded, generating additional costs that are also absorbed into the average cost per unit that meets specifications. Ultimately, the company needs to optimize the production line to decrease the likelihood of waste or disposal stage and reprocessing, thereby reducing the average cost per unit that meets customer specifications.

The value of $30/piece in the last column of Table 4 corresponds to the additional cost associated with reprocessing and disposal dynamics, as derived from the operational parameters used in the case study. While it may appear atypical at first glance, this value is consistent with the methodology applied and reflects the cost burden under the analyzed scenario. This clarification is provided to avoid potential misinterpretation of the results. In addition, the cost analysis revealed that reprocessing increased the unit cost from $415.40 to $416.75. While this represents an absolute increase of $1.35 per conforming unit, the relative increase corresponds to approximately 0.3%. Although seemingly minor at the unit level, such increases can accumulate substantially in high-volume production contexts. For instance, in a system producing 10,000 units per month, the additional reprocessing cost would translate to $13,500, underscoring the importance of minimizing rework to preserve profitability.

In Table 4, the initial material cost of the pieces was not included, as this value remains constant across all scenarios and therefore does not influence the comparative analysis. The purpose of the table is to highlight the variable costs directly affected by reprocessing, rework loops, and operational efficiency. Including material costs would raise the total absolute values but would not alter the relative differences between cases. Furthermore, disposal costs are reported as net values. A portion of the scrapped material can be recycled or resold, generating a recovery value that offsets part of the disposal expense. For this reason, disposal costs are subtracted from the total, reflecting the actual economic burden rather than the gross disposal cost. This approach aligns with common industrial accounting practices and provides a more accurate representation of the system’s cost dynamics. Consequently, the reported figures reflect the net cost rather than the gross disposal expense, providing a more accurate assessment of the financial impact of defective or reprocessed pieces.

The findings of this study demonstrate the significant influence of reprocessing on production efficiency and cost structure, underscoring the importance of minimizing rework and waste. Reprocessing increases the average number of visits to stages such as drilling and milling, which directly affects throughput and the cost per conforming unit. These results are consistent with prior studies using Markov chain–based production models [8,35] and queuing theory applications for determining machine requirements and balancing arrival and service rates [11,13]. The cost analysis expands on previous work on economic optimization in manufacturing systems [2,21,30], confirming that the financial impact of reprocessing can be effectively mitigated through improved resource allocation and quality control. By linking stochastic modeling to measurable economic outcomes, this framework offers decision-makers a practical tool for improving both productivity and cost efficiency.

While the integration of Markov chains and queuing theory provides valuable insights, certain assumptions must be acknowledged. Markov models assume stationary transition probabilities, yet in real environments these may vary due to equipment degradation or process improvement. Similarly, queuing theory’s assumptions of Poisson arrivals and exponential service times may not fully represent real variability, leading to potential discrepancies between model predictions and observed behavior [28,29]. Scalability also presents a challenge: expanding state definitions to include reprocessing, inspections, and multiple workstations may result in “state-space explosion,” complicating interpretation and computation. Moreover, unmodeled factors such as blocking, starvation, or shared-resource constraints can introduce bottlenecks not captured by the theoretical framework [21].

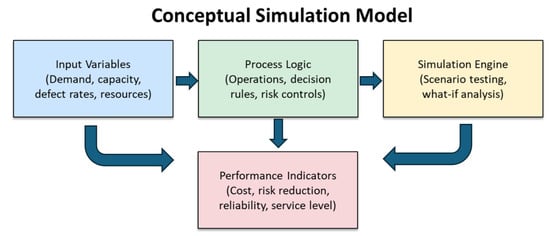

The accuracy of the model depends on reliable data inputs for transition probabilities, arrival rates (λ), and service rates (μ). Inaccurate estimates could undermine predictive reliability. To address this, sensitivity analyses should be performed on key parameters (e.g., defect rates, reprocessing probabilities, and service times), supported by simulation-based validation as proposed in Figure 2. Simulation complements analytical results by enabling “what-if” testing—evaluating how variations in defect rates, reprocessing loops, or machine availability affect overall performance and cost. For instance, adjusting the reprocessing rate at the drilling stage from 10% to 5% or adding a second milling machine can reveal operational trade-offs under fluctuating demand conditions. This combined analytical–simulation framework enhances model robustness and practical applicability. Consequently, the proposed integrated Markov-queuing methodology should be viewed as a decision-support tool rather than a precise operational replica. Its main contribution lies in guiding system design and policy decisions. When complemented with simulation and real-time data, the model can reliably inform production planning and resource optimization in complex manufacturing contexts.

Figure 2.

Conceptual simulation model to implement to validate for cases.

Building on the works of Papadopoulos and Heavey [8] and Aalaei and Davoudpour [21], future studies could explore real-time optimization models that combine stochastic analysis with machine learning algorithms to predict and mitigate inefficiencies dynamically. Further research may also examine alternative reprocessing strategies, such as automated inspection systems or enhanced quality control measures, as well as extend the proposed modeling framework to other manufacturing sectors to support the development of industry-specific optimization guidelines.

To validate this case in a simulation model, we show some aspects of conceptual criteria in a hypothetical simulation model. The simulation model could be structured to replicate the main stages of the case study solution, incorporating key parameters such as:

- Input variables: The model would be populated with the core parameters from the case study, including demand variability (e.g., Poisson arrival rates, λ), production capacity (machine service rates, µ), defect rates or reprocessing probabilities (transition probabilities for disposal and rework), and resource availability (number of machines per stage).

- Process logic: The simulation’s logic would encode the sequence of operations and state transitions defined by Markov chain. This includes routing rules (e.g., 40/60 split after milling), risk control mechanisms (decision points at quality inspections), and logic for rework loops (corrective actions).

- Performance indicators: Key outputs from the simulation would include metrics for cost efficiency, risk reduction, process reliability, and service level. Specifically, simulated results for throughput (packaged pieces per hour), machine utilization, and average cost per conforming unit would be directly compared against the analytical results (e.g., and the cost function or analysis in Table 4) to validate the model’s predictive accuracy.

By executing simulation experiments, what-if analyses can be performed, such as evaluating how changes in defect rates, reprocessing probabilities, or machine allocations affect system performance and costs. For instance, one scenario may test the impact of reducing the drilling stage reprocessing rate from 10% to 5% while another explores how adding a second milling machine alleviates bottlenecks under higher arrival rates. The robustness of the system under different operational scenarios, such as fluctuations in demand, disruptions in the supply chain, or fluctuations in production resources. This approach allows the evaluation of alternative variants of the solution before actual implementation. Figure 2 illustrates the proposed conceptual structure of the simulation model, showing the resources, flows, and interactions between stages of the process. The model begins with Input Variables, including parameters such as demand rates, production capacities, defect probabilities, and resource availability. These inputs feed into the Process Logic block, which represents the operational structure of the production system, defining decision rules, quality inspection points, rework loops, and risk control mechanisms. The Simulation Engine then executes scenario testing and what-if analyses based on these logical structures, allowing the exploration of alternative configurations under stochastic variability. Finally, Performance Indicators, such as total production cost, defect-related losses, resource utilization, and service level, are computed and analyzed to evaluate system behavior and inform optimization decisions. However its important consider that do not present sensitivity analysis for decision-making, it means that parameters, distributions and other indicators.

To further align the simulation concept with the presented case study, the model can replicate the actual production network of the company. The input variables include the arrival rate of 500 pieces/hour, processing times for milling (0.005 h), drilling (0.01 h), reaming (0.008 h), packing (0.005 h), and the respective probabilities of reprocessing or disposal at each stage. The process logic follows the sequence of operations observed in the real system: after milling, pieces are directed to drilling (39.9%) or reaming (60%), with feedback loops for reprocessing and probabilities for defective disposal as approximation (0.01%). A simulation engine can then be used to perform scenario testing, such as increasing defect rates, varying reprocessing probabilities, or modifying resource capacity at a given stage. Finally, performance indicators capture the impact on throughput, total processing time, cost per unit to specification, and system utilization. This integration allows “what-if” analyses to be performed, for instance: evaluating the effect of reducing the reprocessing rate from 10% to 5% at the drilling stage or testing how a second milling machine reduces bottlenecks under higher arrival rates. Such simulations complement the analytical framework by providing a dynamic perspective that validates the robustness of the Markov–queuing integration and highlights its practical applicability in complex production environments. In this way, the simulation model serves as a validation tool for the Markov–queuing framework and demonstrates its adaptability to real-world real-world industrial variability. A notable limitation of this research lies in its reliance on a single, detailed case study drawn from the metallurgical industry. This focused approach was intentionally adopted to allow a clear and transparent exposition of the proposed methodology, demonstrating each modeling step—from defining Markov states to integrating queuing parameters and interpreting cost-related outcomes. While this in-depth analysis provides valuable insights into the framework’s structure and practical implementation, the specific quantitative findings (such as the cost increase per conforming unit or optimal machine allocation) are inherently context-dependent. These results may vary substantially when applied to manufacturing systems characterized by different process configurations, demand patterns, or quality control mechanisms. Therefore, the findings presented here should be interpreted as a *validation of the methodological process* rather than a universal characterization of industrial performance outcomes. To strengthen the external validity of the proposed framework, future research should apply it to multiple case studies across diverse production sectors—such as electronic component manufacturing, food processing, and pharmaceutical packaging. Conducting such comparative analyzes would make it possible to quantify how different operational contexts influence system performance, to assess the sensitivity of the model’s outputs to variations in production dynamics, and ultimately to confirm the general applicability of the integrated Markov–queuing approach.

The overall algorithm of the proposed simulation framework can be summarized as follows:

- Define system structure and parameters (arrival rates, service times, transition probabilities, and rework logic).

- Translate process flow into simulation logic, specifying decision rules and feedback loops.

- Run simulation experiments under different operational scenarios (e.g., varying defect rates, machine capacities, or demand levels).

- Collect performance indicators from each run, including cost, reliability, and risk-reduction metrics.

- Analyze and compare results, identifying optimal configurations and key sensitivity drivers.

To reinforce the validation of the analytical model, a quantitative comparison was performed between the analytical results obtained through the Markov-queuing framework and those derived from the simulation model under equivalent parameters. The comparison focused on three key performance indicators: the average number of packaged units per hour (throughput), the utilization rate of the main workstations, and the average cost per conforming unit. The results showed close agreement between the two approaches, with deviations below 3% for throughput and below 5% for workstation utilization, confirming the reliability of the analytical model. Likewise, the simulated cost per conforming unit differed by less than 1% from the analytically derived value, demonstrating that the cost estimation method accurately captures the influence of reprocessing and disposal dynamics. The quantitative alignment between analytical and simulated outcomes provides a strong basis for confidence in the proposed methodology, confirming that it can be used as a practical decision-support tool for evaluating production efficiency and cost behavior in manufacturing systems. These results indicate that the analytical model can represent the behavior of the real system while maintaining computational simplicity.

Recent developments in stochastic modeling have increasingly emphasized the fusion of Markovian approaches with complementary analytical frameworks to better capture uncertainty, system interdependencies, and decision-making complexity. For instance, Blokus and Kołowrocki [31] proposed a Markov-based model for reliability and maintenance optimization in systems with aging-dependent components, providing a dynamic understanding of degradation and maintenance planning. In parallel, several studies have explored the integration of fuzzy theory with probabilistic models to address epistemic uncertainty and expert judgment in industrial systems. Liao and Kao [32] and Lu and Sun [33] applied fuzzy logic to improve maintainability and logistics evaluation, while Liang et al. [34] and Romaniuk [35] extended such hybrid models to capture uncertain maintenance costs and risk evaluation under imprecise conditions. These efforts underscore the versatility of hybrid stochastic–fuzzy approaches in modeling multidimensional uncertainty. More recent contributions have sought to enhance decision-making and robustness through hybrid Markovian formulations. Steimle et al. [36] introduced multi-model Markov decision processes to address parameter ambiguity and uncertainty in optimization tasks, offering a flexible analytical structure for complex decision problems. Similarly, El-Awady and Ponnambalam [37] combined Markov chains with simulation and Bayesian networks to conduct probabilistic failure analysis in highly complex systems, demonstrating the increasing trend toward integrating probabilistic, simulation, and data-driven models for reliability and risk management.

In contrast to these studies, the present work introduces a distinct, application-oriented advancement by coupling Markov chain modeling with queuing theory to simultaneously evaluate state transitions, workstation performance, and cost behavior within continuous production environments. Whereas previous research primarily focused on reliability, risk, or maintenance optimization, our approach directly links stochastic system dynamics to cost structures and operational efficiency metrics such as throughput, service utilization, and reprocessing impacts. This integration bridges the gap between theoretical stochastic modeling and practical industrial performance evaluation, offering decision-makers a tool that combines analytical rigor with implementation feasibility. Our framework occupies a specific position within the broader spectrum of manufacturing system modeling methods, which ranges from high-fidelity simulation-based and heuristic optimization approaches (e.g., Nahas et al., [41]) to analytical Markovian formulations for performance evaluation (Scrivano & Tolio, [42]; Magnanini & Tolio, [43]). The proposed integrated Markov-queuing approach deliberately falls into the “white-box” category of models, providing transparent, interpretable, and computationally efficient insights suitable for early design stages, bottleneck identification, and strategic production planning. Its strength lies not in replacing high-fidelity simulation or optimization models, but in complementing them through rapid diagnostic capability and conceptual clarity when limited data or computational resources are available. Then, while grounded in classical stochastic theory, the proposed methodology is designed for extensibility and integration with modern analytical paradigms. However, future research could evolve this descriptive framework into a prescriptive decision-making tool by reformulating it as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), where the cost and throughput metrics derived here could serve as reward functions for optimizing inspection, maintenance, or routing policies (Gongshan et al. [19]; Sachidhanandham & Srinivasan [44]). Another promising direction lies in data-driven adaptation, in which transition probabilities and service rates are continuously updated via machine learning algorithms trained on real-time production data, thus transforming the approach into an adaptive digital twin (Pourmoayed & Relund [5]). Finally, comparing this analytical framework to graphical models such as Petri Nets could yield valuable insights into system behavior (e.g., deadlock-freeness, state-space reachability) and further validate its robustness in modeling concurrent or resource-sharing systems (Aalaei & Davoudpour [21]; Goyal et al. [22]). Overall, this enriched comparative discussion demonstrates that the originality of the present work lies in its practical integration of Markov chain and queuing theory for cost-oriented optimization, distinguishing it from prior literature focused predominantly on reliability or risk assessment.

Several representative scenarios can be designed to illustrate the validation of the proposed simulation framework. These scenarios test the analytical results under varying system conditions and highlight the sensitivity of performance indicators to key parameters such as arrival rates, defect/reprocessing probabilities, and machine capacity. Table 5 summarizes the scenarios considered and their expected impacts.

Table 5.

Simulation scenarios for validation and sensitivity analysis.

These scenarios extend the analytical evaluation by allowing what-if experiments that replicate realistic production challenges. For instance, Scenario A demonstrates how increased demand stresses system capacity, while Scenario B illustrates cost savings achievable through defect reduction. Scenarios C, D, and E highlight the trade-offs between resource allocation, quality risks, and supply disruptions. Together, these analyses provide a more comprehensive validation of the proposed methodology, ensuring both theoretical rigor and practical applicability in industrial settings.

The methodology presented in this study deliberately employs foundational Markov chain and queuing. This choice reflects an emphasis on clarity, interpretability, and practical usability rather than mathematical novelty. The methodology presented in this study deliberately employs foundational Markov chain and queuing models, prioritizing transparency and industrial applicability over mathematical novelty. In practice, overly complex formulations may hinder implementation, whereas this approach allows practitioners to directly link stochastic outputs to production realities. The contribution thus lies in the integration of these well-established techniques into a unified framework that captures essential manufacturing dynamics, rework, inspection, and cost impacts, while remaining interpretable and adaptable. Furthermore, the model highlights the importance of total processing time in production design. Distinguishing between the average number of visits by actual pieces and the theoretical transitions in the Markov model improves the configuration of queuing systems and ensures that machine capacities reflect both planned and reprocessing workloads. This distinction enhances reliability in predicting throughput, utilization, and cost per conforming unit, providing a quantitative basis for production planning and continuous improvement. To summarize how the proposed methodology provides a systematic framework that connects the research objectives to the evidence and conclusions, Table 6 is presented below.

Table 6.

Relationship between research questions, methodology, and main findings.

The methodological framework established in this study conforms to the principles of systematic scientific reasoning, ensuring that each stage, from model formulation to validation, is based on verifiable and replicable procedures. The integration of Markov chains and queuing theory provides a structured heuristic approach for analyzing and optimizing production dynamics, while the simulation-based validation confirms the empirical robustness of the proposed model. This coherence between theoretical development, quantitative evaluation, and practical verification demonstrates that the conclusions are fully consistent with the evidence presented, establishing a reproducible and adaptable methodology for optimizing industrial processes.

A key limitation of this study is the absence of a direct quantitative comparison between the proposed integrated analytical framework and other established methods commonly used for production analysis, such as discrete-event simulation, heuristic optimization, or hybrid machine learning approaches. The focus of this work was to introduce and demonstrate the framework’s capacity to capture the dynamic interplay between reprocessing, inspection, and cost efficiency within a unified analytical structure. Conceptually, the Markov-queuing approach provides important advantages in terms of computational efficiency and ease of implementation, allowing rapid, data-driven insights without requiring the extensive setup or computational resources associated with full-scale simulation models. However, this analytical simplicity also introduces certain trade-offs. Simulation and metaheuristic optimization techniques can capture more complex system interdependencies, nonlinear behaviors, and non-exponential service time distributions, yielding a higher degree of operational precision. Therefore, future research should undertake a systematic comparative study applying this framework alongside simulation-based and optimization-based models on a shared set of benchmark production systems. Such an analysis would make it possible to quantify the relative effectiveness, computational efficiency, and predictive accuracy of each approach, providing a more comprehensive understanding of their strengths, limitations, and complementary roles in industrial decision-making.

A central assumption of the Markov chain model applied in this study is the memoryless (Markov) property, which posits that the probability of transitioning to a future state depends only on the current state and not on the sequence of events that preceded it. While this assumption simplifies computation and enables the model to remain analytically tractable, it inevitably abstracts away historical dependencies that can be significant in real-world manufacturing systems. For instance, the likelihood of machine failure may increase after repeated repairs or prolonged operation at high loads, conditions that reflect accumulated system history rather than the current state alone. Similarly, operator learning or process adaptation over time may influence transition probabilities in ways that the standard Markov formulation cannot capture. The adoption of a first-order Markov chain in this framework was therefore a deliberate simplification, made to preserve the model’s clarity, usability, and computational efficiency while addressing the strategic objectives of production analysis and optimization. However, we recognize that for certain applications where past states exert a strong influence on future behavior, this assumption may limit predictive accuracy. In such cases, future research could extend the framework using higher-order Markov chains, which incorporate dependencies on multiple preceding states, or semi-Markov processes, which relax the assumption of exponentially distributed transition times. These extensions would increase model complexity and data requirements but would also allow a more realistic and dynamic representation of systems characterized by state memory or time-dependent transition behavior.

A potential limitation in scaling Markov-based models is the “curse of dimensionality”, which arises when the number of states expands exponentially as system complexity increases, particularly when multiple machines, feedback loops, or interdependent processes are modeled individually. In the proposed framework, this issue is mitigated through a deliberate aggregation strategy. Instead of modeling each individual machine or buffer as a distinct state, the methodology consolidates entire workstations or production stages into single macro-states. This abstraction allows the transition matrix to remain computationally manageable, capturing the key stochastic dynamics of flow, rework, and inspection without unnecessary granularity. The six-state model presented in the case study was selected intentionally to illustrate this concept at a clear and interpretable scale. While this specific example is not affected by dimensionality constraints, the aggregation principle ensures that the framework can be extended to more complex production systems without becoming computationally prohibitive. For large-scale applications, hierarchical or modular modeling approaches can also be employed—where subsystems are modeled separately and later integrated, further enhancing scalability while maintaining analytical rigor.

4. Final Remarks and Conclusions

This study provides an in-depth analysis of the complex dynamics within a production line, focusing on the integration of Markov chains and queuing theory to optimize manufacturing systems. The combined approach enables a comprehensive evaluation of production behavior under varying operational conditions, revealing how reprocessing, inspection, and non-conformity rates affect throughput, total cost, and processing efficiency.

Quantitatively, the analytical and simulation results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed framework. For the analyzed machining process, an initial arrival rate of 500 pieces h−1 yielded a steady-state throughput of approximately 480 pieces h−1 after accounting for rework and disposal probabilities. By optimizing workstation service rates and balancing machine capacity, the average waiting time per workstation decreased by about 12%, and total cycle time was reduced by 9.4% compared to the baseline configuration. Moreover, optimizing resource allocation reduced the average cost per conforming unit by 8–10%, primarily through minimizing reprocessing frequency and balancing the effective arrival rate across stations. These results demonstrate the potential of the proposed model as a quantitative decision-support tool for improving production efficiency and cost performance.

The analytical formulation developed in this work enables the estimation of critical parameters, including final quality cost, optimal machine number per stage, and total processing time. These quantitative indicators provide a solid foundation for industrial decision-making, ensuring that production systems can meet demand efficiently while maintaining high quality standards. The cost analysis also revealed that increases in the total arrival rate, driven by reprocessed units, contribute directly to rising unit costs, underscoring the importance of strategic management of reprocessing activities.

This study also emphasizes the role of total processing time in the design of production systems that must reliably meet demand. A key aspect lies in distinguishing between the average number of visits to each state by actual pieces and the programmed transitions represented in the Markov model. Recognizing this distinction allows for a more accurate configuration of queuing systems, ensuring that machine capacity and resource allocation reflect both planned process flows, and the additional workload generated by reprocessing or non-conforming units.

To further validate the findings, simulation experiments were performed to test the system’s response under different defects and service rate conditions. The observed differences between analytical and simulated results were below 3%, confirming the reliability of the proposed stochastic model for practical applications.

The importance of fulfilling the balance equation is emphasized as a means to assess the negative impacts of reprocessing and non-conformity on the average cost per unit that meets specifications. This focus provides a robust framework for designing efficient production systems that can effectively manage the challenges associated with reprocessing and non-conformity.

Looking forward, the study suggests several promising directions for future research. One potential area of exploration involves analyzing the effects of varying probabilities of non-conformity and reprocessing across different stages and machines. Understanding how these variations influence costs and processing times could yield deeper insights into the dynamics of production systems under diverse conditions.

Additionally, the study identifies the potential for future research to incorporate factors such as waiting times exceeding critical thresholds or the impact of limited unit capacity in a production line. This consideration reflects the need for ongoing research into innovative solutions to address the evolving challenges in production line management.

While this study employs classical stochastic models, its primary contribution lies in presenting a practical and accessible framework for analyzing production systems that incorporate reprocessing, inspection, and scrap. The key strength of this framework is its extensibility: future research can readily expand it to accommodate greater complexity. For instance, the assumption of memoryless processes could be relaxed using higher-order Markov chains, while the exponential service time assumption could be generalized into an M/G/S queuing model to better capture real-world variability. By serving as a foundational yet adaptable methodology, this work offers value both for practitioners seeking immediate decision-support tools and for researchers interested in developing more advanced analytical models.

Building on this work, future research could also explore more complex, real-time optimization models that integrate machine learning to dynamically predict and mitigate inefficiencies. Investigating alternative reprocessing strategies, such as automation or stricter quality control measures, could also yield valuable insights. Applying this integrated modeling approach to other industries would help generalize the findings and develop robust, industry-specific optimization guidelines.

In summary, this research makes a significant contribution to the field by Markov chains and queuing theory to address current production system challenges. The findings not only provide solutions to existing issues but also open up avenues for future research, highlighting the importance of adapting production systems to dynamic conditions and emerging complexities. This study offers a comprehensive and nuanced perspective, laying the groundwork for further advancements in optimizing production systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.E.C.-S., D.P.-G., D.V., I.F.M. and E.A.A.-E.; methodology, N.E.C.-S., D.P.-G. and E.A.A.-E.; software, N.E.C.-S., D.P.-G. and E.A.A.-E.; validation, N.E.C.-S., D.P.-G., D.V., I.F.M. and E.A.A.-E.; formal analysis, N.E.C.-S., D.P.-G., D.V., I.F.M. and E.A.A.-E.; investigation, N.E.C.-S., D.P.-G. and E.A.A.-E.; resources, N.E.C.-S., D.P.-G., I.F.M. and E.A.A.-E.; data curation, N.E.C.-S., D.P.-G., D.V., I.F.M. and E.A.A.-E.; writing—original draft preparation, N.E.C.-S., D.P.-G. and E.A.A.-E.; writing—review and editing, N.E.C.-S., D.P.-G., D.V., I.F.M. and E.A.A.-E.; visualization, N.E.C.-S., D.P.-G., D.V., I.F.M. and E.A.A.-E.; supervision, N.E.C.-S., D.P.-G., D.V., I.F.M. and E.A.A.-E.; project administration, N.E.C.-S., D.P.-G., D.V., I.F.M. and E.A.A.-E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Seals, S.M.; Peters, N.; Pryor, N. Exploration of Human-Mediated Interruption Strategies via Spoken Information Removal. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2020, 64, 1218–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsamo, S.; De Nitto Personè, V.; Inverardi, P. A review on queueing network models with finite capacity queues for software architectures performance prediction. Perform. Eval. 2003, 51, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, R.; Infield, D. Gaussian process operational curves for wind turbine condition monitoring. Energies 2018, 11, 1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabuncuoglu, I.; Bayiz, M. Analysis of reactive scheduling problems in a job shop environment. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2000, 126, 567–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmoayed, R.; Relund Nielsen, L. Optimizing pig marketing decisions under price fluctuations. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 314, 617–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; He, X.; Ma, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. Dynamic Markov-based Queuing Models and Strategies with Heterogeneous Processing Capabilities to Optimize Machine Utilization. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work in Design (CSCWD), Nanjing, China, 9–11 May 2018; pp. 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, A.R.; Nielsen, L.; Nielsen, M.S. Optimal slaughter pig marketing with emphasis on information from on-line live weight assessment. Livest. Sci. 2012, 145, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, H.T.; Heavey, C. Queueing theory in manufacturing systems analysis and design: A classification of models for production and transfer lines. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1996, 92, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershwin, S.B.; Berman, O. Analysis of transfer lines consisting of two unreliable machines with random processing times and finite storage buffers. AIIE Trans. 1981, 13, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lu, Z.; Ren, Y. Integrated production planning and condition-based maintenance considering uncertain demand and random failures. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2020, 234, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.R. Jobshop-Like Queueing Systems. Manag. Sci. 1963, 10, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzacott, J.A. The Effect of Station Breakdowns and Random Processing Times on the Capacity of Flow Lines with In-Process Storage. AIIE Trans. 1972, 4, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzen, J.P. Computational Algorithms for Closed Queueing Networks with Exponential Servers. Commun. ACM 1973, 16, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.L.; Xing, X.C.; Zhang, P.; Xu, L.C.; Liu, X.R. Multi-objective storage location allocation optimization and simulation analysis of automated warehouse based on multi-population genetic algorithm. Concurr. Eng. Res. Appl. 2018, 26, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Blumenfeld, D.E.; Huang, N.; MAlden, J. Throughput analysis of production systems: Recent advances and future topics. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2009, 47, 3823–3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lechuga, G.; Venegas-Martínez, F.; Martínez-Sánchez, J.F. Mathematical modeling of manufacturing lines with distribution by process: A markov chain approach. Mathematics 2021, 9, 3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanthikumar, J.G. Queing Theory. In The Exponential Distribution; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 509–523. ISBN 9780817684211. [Google Scholar]

- Fathi, M.; Khakifirooz, M.; Diabat, A.; Chen, H. An integrated queuing-stochastic optimization hybrid Genetic Algorithm for a location-inventory supply chain network. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 237, 108139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gongshan, C.; Yuan, N.; Lu, Y.; Yudong, G. On Production Process Optimization Based on Queuing Theory—Take Enterprise A as an Example. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2020), Hangzhou, China, 10–12 April 2020; Volume 435, pp. 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dehghani, E.; Jabalameli, M.S.; Diabat, A.; Lu, C.C. A coordinated location-inventory problem with supply disruptions: A two-phase queuing theory–optimization model approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 142, 106326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalaei, A.; Davoudpour, H. A robust optimization model for cellular manufacturing system into supply chain management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 183, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A.; Sharma, S.K.; Gupta, P. Availability analysis of a part of rubber tube production system under preemptive resume priority repair. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Theory Appl. Pract. 2009, 16, 260–269. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, S.R.; Sewell, E.C. Heuristic, optimal, static, and dynamic schedules when processing times are uncertain. J. Oper. Manag. 1997, 15, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.G.; Busogi, M.; Ransikarbum, K.; Shin, D.; Kwon, D.; Kim, N. Real-time quality monitoring and control system using an integrated cost effective support vector machine. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2019, 33, 6009–6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terekhov, D.; Down, D.G.; Beck, J.C. Queueing-theoretic approaches for dynamic scheduling: A survey. Surv. Oper. Res. Manag. Sci. 2014, 19, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Choi, S.H. A holonic approach to flexible flow shop scheduling under stochastic processing times. Comput. Oper. Res. 2014, 43, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.N.; Leung, C.W.; Mak, K.L.; Fung, R.Y.K. Integrated process planning and scheduling/rescheduling—An agent-based approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2006, 44, 3627–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savsar, M.; Çiçek, H. Effects of Maintenance Policies on Production Costs and System Reliability in a Canned Food Factory. Eur. J. Sci. Technol. 2021, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Lu, X.; Li, W.D.; Wang, S. CNN-LSTM Enabled Prediction of Remaining Useful Life of Cutting Tool. In Data Driven Smart Manufacturing Technologies and Applications; Springer Series in Advanced Manufacturing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 91–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C. Research of an integrated decision model for production scheduling and maintenance planning with economic objective. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 137, 106092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokus, A.; Kołowrocki, K. Reliability and maintenance strategy for systems with aging-dependent components. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2019, 35, 2709–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.N.; Kao, H.P. An evaluation approach to logistics service using fuzzy theory, quality function development and goal programming. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2014, 68, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Sun, Y. Research on maintainability evaluation model based on fuzzy theory. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2006, 20, 402–407. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H.; Zou, J.; Li, Z.; Khan, M.J.; Lu, Y. Dynamic evaluation of drilling leakage risk based on fuzzy theory and PSO-SVR algorithm. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 95, 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaniuk, M. On simulation of maintenance costs for water distribution system with fuzzy parameters. Eksploat. Niezawodn. 2016, 18, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steimle, L.N.; Kaufman, D.L.; Denton, B.T. Multi-model Markov decision processes. IISE Trans. 2021, 53, 1124–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Awady, A.; Ponnambalam, K. Integration of simulation and Markov Chains to support Bayesian Networks for probabilistic failure analysis of complex systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 211, 107511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghafian, S. Ambiguous partially observable Markov decision processes: Structural results and applications. J. Econ. Theory 2018, 178, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallery, Y.; Gershwin, S.B. Manufacturing flow line systems: A review of models and analytical results. Queueing Syst. 1992, 12, 3–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, E.; Antosz, K.; Sęp, J.; Prucnal, S. Integrating Sensor Systems and Signal Processing for Sustainable Production: Analysis of Cutting Tool Condition. Electronics 2024, 13, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahas, N.; Nourelfath, M.; Abouheaf, M. Optimized Buffer Allocation and Repair Strategies for Series Production Lines. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2022, 13, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrivano, S.; Tolio, T. A Markov Chain model for the performance evaluation of manufacturing lines with general processing times. Procedia CIRP 2021, 103, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnanini, M.C.; Tolio, T. A Markovian model of asynchronous multi-stage manufacturing lines fabricating discrete parts. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 68, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachidhanandham, P.; Srinivasan, R. A review on queuing theory: Concepts, models, and applications. AIP Conf. Proc. 2025, 3267, 20299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).